1. Introduction

Using the most updated models we can quantify and locate a coming event and its characteristics more and more precisely, forecasting for example maximum wind speed, maximum rainfall, and areas most likely affected in the next hours or days [

1,

2,

3,

4]. On the other hand, the more sophisticated the models are, the more they depend on the availability of data, assumptions of continuity and skills of those who use them to make decisions [

5]. In practice, even the best models available may be misleading (e.g., because of insufficient data) or may not be used correctly. At the same time, even the best communication strategy, the best risk maps, the best monitoring, and alert technologies could have little effect on behaviours, if residents and local administrators are not aware of the risk, do not have easy access to the risk information, or do not pay attention. In this respect, it becomes fundamental to understand the conditions for an effective preparation and engagement of local communities in risk management. Risk awareness is a matter that goes beyond the mere management (or prediction) of physical processes and involves cognitive, social, administrative and regulatory processes; these latter aspects can have different geographies, that is, they can differentiate spatially based on local social processes.

In line with the European Flood Directive (EC, 26/11/2007), the United Nations Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 invites to move from a “resistance model”, based on “structural measures” (such as artificial riverbanks or bridles), to risk management plans that include the resilience of local communities and integrate the structural measures with “non-structural measures”, such as communication and participation [

6].

The “relational theory of risk” aims at improving risk communication [

7] and it encourages “risk managers” not only to communicate and inform local groups about the risks calculated by the experts but also to investigate the different values of potentially conflicting groups. The essence of this theory is that risk emerges from the presence of (1) “risk objects” (anything that “poses danger”, be it a law, a thing, an entity, a human being), (2) “objects at risk” and (3) causal relationships between (1) and (2). Flood risk is therefore considered a “social construct” that includes water flow management, land use, forest management and socio-political relationships [

6,

8]. Similarly, “community resilience” with respect to natural hazards emerges from the actions, social learning, resources, and capabilities of local communities [

9]. While the experts’ mental models emerge from the formal study of contents (formalised models), lay people’s mental models derive from shared knowledge and personal experiences [

10,

11]. For them, the risk is not a mere probability but a process that is continuously updated and influenced by interactions between subjects, events, and practices: direct knowledge is thus mediated by social relationships (ibidem). One of the goals of risk communication is precisely to understand mental models to support the adoption of effective behaviours for managing risks and their consequences.

The conceptual framework for hazard risk management proposed by Di Baldassarre and colleagues [

12,

13] highlights how the impacts and perceptions of natural hazards influence resilience governance, while at the same time risk management can alter the magnitude of impacts and spatial distribution of the hazards. Furthermore, these mutual effects on a local scale are influenced by global factors, for example climate changes can alter the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, while global socioeconomic trends (including population growth, ageing and urbanisation) can increase risk exposure locally. Despite their relevance, accurate information on resident`s risk perception, risk-taking attitude and trust in authorities is only occasionally available for local risk managers [

13,

14], the scientific literature seems to focus each time on a specific set of few variables rather than considering the variety of systems and dynamics involved in risk management as a “social construct”.

The first objective of this article is to present the results of a survey on the awareness of flood risk, conducted before and after an exceptional weather event, during a European project called FRANCA (Flood Risk Anticipation aNd Communication in the Alps). Although the survey was administered between 2015 and 2019, the information it provides will remain relevant to readers in 2024 for several compelling reasons, which will be presented in the discussion section. The second objective is to present a systems thinking approach to grasp the dynamic complexity of the relationships between key variables in risk management over time.

The next paragraph contextualizes the research and the LIFE FRANCA project. After presenting the survey findings and their interpretation with a qualitative dynamic model, the discussion section addresses the key implications of the adoption of a systems thinking approach for risk communication and management.

2. The Case Study and the Project LIFE FRANCA

The case study presented here is one of the results of the EU-funded project LIFE FRANCA, which had the following objectives:

Introducing an anticipatory governance approach in the management of natural risks.

Developing an effective and continuous communication strategy (differentiated by target) that leads to increasing knowledge and awareness of the natural risks and to change mental models and the consequent habits and behaviours.

Supporting the preparation of the population to face flood events, through a participatory process involving citizens, technicians, and decision makers.

Developing tools and methodologies applicable in other regions and for other natural risks related to climate change.

The project consisted in a variety of activities, such as: survey about the perception of flood risks; participatory activities such as building of strategic scenarios and Three Horizon workshops, concerning risk management in the next twenty years; educational activities and scientific dissemination; construction of a geo-portal on hydrogeological risk; training activities for professionals and public servants.

The survey and participatory activities focused on the Trento Province, Northern Italy, with a population of about 540,000 inhabitants, an extension of 6.200 km2, divided into 16 valley communities (“Comunità di Valle”), and with a predominantly alpine landscape.

The survey objectives were to: i) gather information about perceptions and knowledge of flood risks and their management by different target groups, ii) explore individual resources and trust in institutions in case of emergency, iii) evaluate the impacts of the LIFE FRANCA project.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. The Survey

The survey was based on a questionnaire that included a total of 11 items, beyond the usual socio-demographic data, such as gender, age, level of education, place of residence, and place of work or main daily activity.

Table 1 shows the key items used for data analysis in this paper, while Table A1 in the Annexes includes the full version of the questionnaire. Two specific questions (Q10 and Q11) were defined in order to explore individual resources and trust in institutions in case of emergency, in terms of mental simulation of an individual response in a fictitious but plausible situation.

The questionnaire was administered in different ways using a mix of convenience sampling [

15] and purposive sampling [

16], looking for both homogeneity within the groups and maximum variation between groups. These two nonprobabilistic sampling techniques aimed at achieving a greater understanding of processes rather than generalisations to the entire national or regional population; in other words, a case study logic underpins the research, instead of the sample logic [

17].

The questionnaire was printed and distributed i) in the teaching activities of the project (in schools), ii) to participants in the project communication events, iii) by project partners to their networks, and iv) digitally on the project website. The collection period was approximately 30 months, between May 2017 and December 2019. A total of 1980 respondents filled in the survey.

The sampling period included an exceptional weather event. Between 27 and 29 October 2018, several high-impact weather phenomena affected different areas of the Italian peninsula, in particular over the north-eastern regions. Over the eastern Italian Alps, the fierce wind, associated with gust values exceeding 50 m s

−1 (180 mk/h) at some locations, caused 41,000 ha of forest damaged and a loss of about 8.5 million m

3 of growing stock. During three days, rainfall maxima ranged between 600 mm in the central Alps and almost 900 mm in the eastern Alps. For several Alpine areas, this was the strongest event of the last 150 years in terms of rainfall and wind intensity [

18].

As national and international media coverage lasted several days, and commemorative events one and two years later followed, it can be assumed that the entire population of the region had heard of Vaia and seen images of the crashed woods.

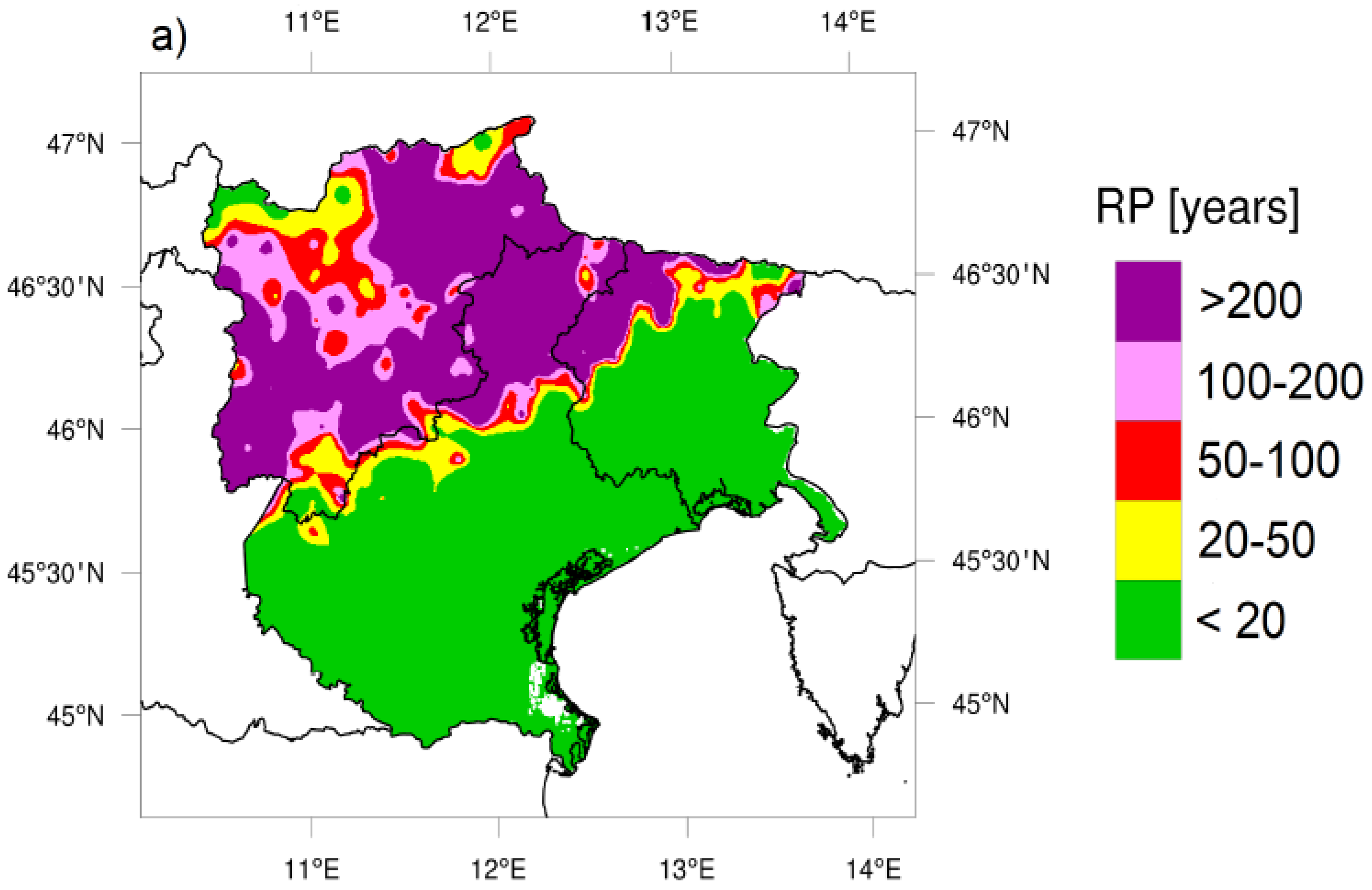

Figure 1.

Return period for 72-h accumulated precipitation, based on station data (image from Giovannini et al. [

18], Trento Province covers about one half of the Trentino-Alto Adige region which corresponds to the polygon with the highest percentage of purple areas in the map).

Figure 1.

Return period for 72-h accumulated precipitation, based on station data (image from Giovannini et al. [

18], Trento Province covers about one half of the Trentino-Alto Adige region which corresponds to the polygon with the highest percentage of purple areas in the map).

Table 2.

Sample’s summary statistics.

Table 2.

Sample’s summary statistics.

| Socio-demographic groups |

Percentage |

| Gender |

Woman |

47,1% |

| |

Man |

52,9% |

| Age |

16-30 years |

62,3% |

| |

>30 years |

37,7% |

| Level of education |

University degree or higher |

39,2% |

| |

Lower education level |

60,8% |

| Response period with respect to Vaia |

After |

69,8% |

| |

Before |

30,2% |

| Category of respondent |

Public administrator |

3,0% |

| |

Citizen |

28,5% |

| |

Journalist |

1,9% |

| |

Technicians |

9,5% |

| |

Student or teacher |

57,2% |

The answers to the questionnaire were summarised in descriptive statistics and analysed with a comparison between socio-demographic characteristics and key variables. For the binary variables (Before/after Vaia, Experience, Gender, grouped levels of Education, grouped ranges of Age), the differences were evaluated with the Mann-Whitney U Test for independent samples; for the multinomial variables (categories, territories) with the Kruskal-Wallis Test (non-parametric ANOVA), using the Jamovi statistical software (version 1.6;

www.jamovi.org). Only the highly significant differences (P <0.001) are discussed below.

3.2. A Conceptual Framework Based on Systems Thinking

In the Province of Trento the flood risk is managed by the provincial office for watershed management (Servizio Bacini Montani, Mountain Basin Service), which finances structural and non-structural measures on the basis of three-year plans that are updated annually through consultations with local administrators. In some ways, the size of the funding is sensitive to the local demand for protection. After the disastrous Vaia event, with impacts on the entire provincial territory, a general increase in demand and therefore for investments in structural measures was plausible. In effect, the dynamics of financed amounts increased for three years after the event.

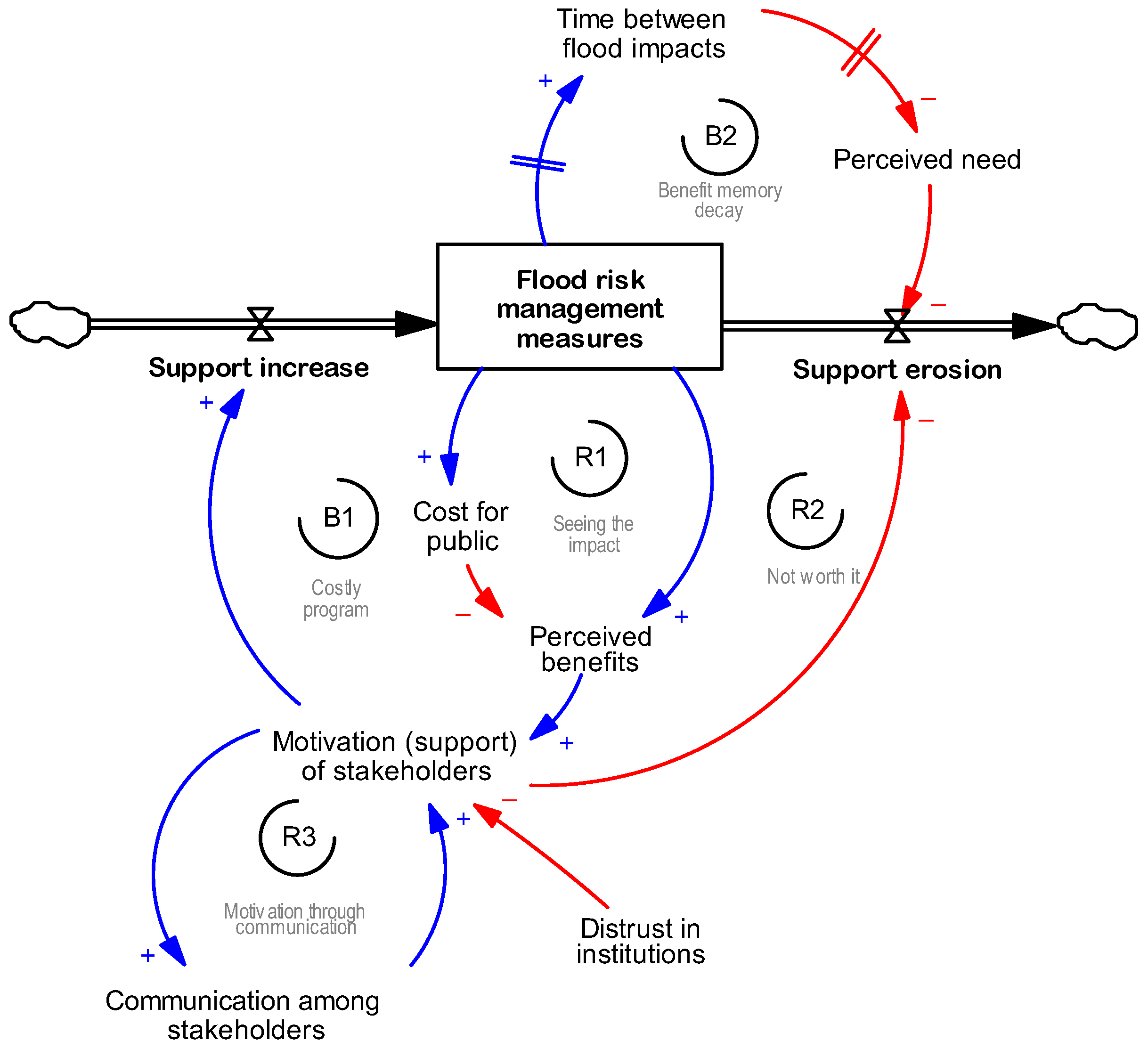

To explore possible feedback loops between risk perception, communication, and management we propose a conceptual framework (

Figure 2) based on a Systems Thinking tool such as stock and flows model and causal loop diagram. A stock and flow model represents how resources (stocks) accumulate or deplete over time based on the rates of inputs (inflows) and outputs (outflows). Stocks are the “state” variables (e.g., water in a tank), while flows are the rates of change (e.g., filling or draining). A causal loop diagram (CLD) visualizes the feedback structure of a system using variables connected by arrows to indicate cause-and-effect relationships. It helps identify feedback loops and system behavior. Arrows are distinguished between two causal polarities: positive (+) where a change in one variable causes a change in the same direction in another (e.g., more effort → better results); negative (-), where A change in one variable causes an opposite change in another (e.g., more resistance → slower progress).

In our model, the stock variable is the amount of active “flood risk management measures” that can rise by “support increase” and can decline due to “support erosion”. Flood risk management measures are intended as a variety of possible measures in action or functioning on a territory, such as structural measures to alter the frequency of events [

14], exposure reduction measures such as relocation of functions, services and buildings [

19], or measures to reduce vulnerability such as non-structural measures on a community and individual scale [

20]. Associated to “support increase” a variety of social processes could be entailed: from political support, or approval of specific plans, or requests for resource allocation (e.g., for the maintenance of hydraulic protection works), to initiatives of citizens. It is assumed that the more support there will be, the more measures will be put into practice or implemented.

This is not intended to constitute a new theory of risk perception or replace other previous ones, such as the psychometric paradigm [

21,

22] and the Protection Motivation Theory [

23], rather it is used here as a tool to visualise plausible feedback loops in the reality of risk management and to highlight its dynamic complexity [

24]. The rationale of the conceptual framework presented here lies in the recognition that risk management is not only a technical issue, but also a political one, in the sense that it depends on the support and consensus of the local community for its implementation over a medium-long period.

The framework represents the minimum system structure capable of explaining some complexity (non-linearity) in risk management. The non-linear nature of socio-hydrological processes is called into question not only by recent conceptual frameworks but also by formal modelling [

25]. Many risk perception studies have focused on the relationship between awareness, willingness to act and preparedness or exploring the links between these variables [

26].

We recognized and schematized 5 loops related to different processes, involving different actors at different times. Flood risk management measures has a perceived benefits that can be amplified through the communication loop (R3), this enact a reinforcing loop R1. The same measures may be perceived as costly respect to the benefits, this can reduce the support over time within a balancing loop (B1). The same communication among stakeholders affected by distrust in institutions may increase the support erosion rate within a reinforcing loop (R2). The flood management measures if effective, may reduce risk exposure and increase the time between perceived impact; this period without impacts may convince someone, , after a delay, about the uselessness of such measures; this may lead to a decrease in “perceived need” and therefore support (B2). In fact, the magnitude or frequency of events influences the level of vividness of public memory and the likelihood of direct or indirect (narrated) experiences, which influence public perceptions [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. At the same time, a “distrust in institutions” may compete for support for risk management measures, which may be considered not important nor a priority (respect other local issues). “Distrust in institutions”, which translates into attitudes such as “we protect ourselves autonomously”, emerged in the participatory activities of the FRANCA project as a possible scenario in which the activation of social capital, which generally improves the community response to adverse events [

19,

20,

31,

33], replaces public interventions considered dysfunctional or insufficient. In all this, the community sense of self-sufficient security may have an ambiguous relationship, between support and obstacle, with respect to the support of public risk management measures.

Based on the results of the survey we further developed the model of

Figure 2 using the simulation web platform (Silico

®,

https://silico.app/) and adopting the Agile-System Dynamics approach proposed by Warren [

34], in which the simulation models are considered a learning tool by successive approximation, rather than a forecast support. Thus, we added a second stock variable to qualitatively simulate the related dynamics in terms of three plausible dynamics, or what-if scenarios: baseline, decrease of trust in institutions, increase of sense of security. Each stock variable can increase or decrease through the balance loop between them. On the right side of the model, we linked the decrease rate of “risk management measures” to “distrust” in institutions and “sense of security” in order to simulate the qualitative dynamics that emerged in the study. The complete description of the model and related equations is reported in the additional materials.

4. A Selection of Results

Respondents generally agree with the fact that floods are a real threat (80% agree and fairly agree with Q1.1), that flood events will become more frequent in future (96% agree with Q1.2), that hydraulic protection works are able to minimise the risks (90% agree with Q1.3), at the same time they agree about that the population has little awareness and tools to manage the resulting risks (91% agree with Q1.4).

About 65% of respondents remember at least a flood event (or debris flow) in their municipality or nearby. The events mentioned occurred over a period of about 50 years (from 1966 to 2019). The most cited damages from flood events concern properties, agricultural activities and common areas.

Among actions or factors that can increase the flood risks, “building close to water courses”, “poor management of water courses” and “increase the impermeability of the territory” were those mentioned the most. Among the actions deemed most effective to improve the response to flood events, “improving knowledge of the risk”, “training citizens and families on what to do during the event” and “monitoring the minor rivers and streams” were those mentioned the most.

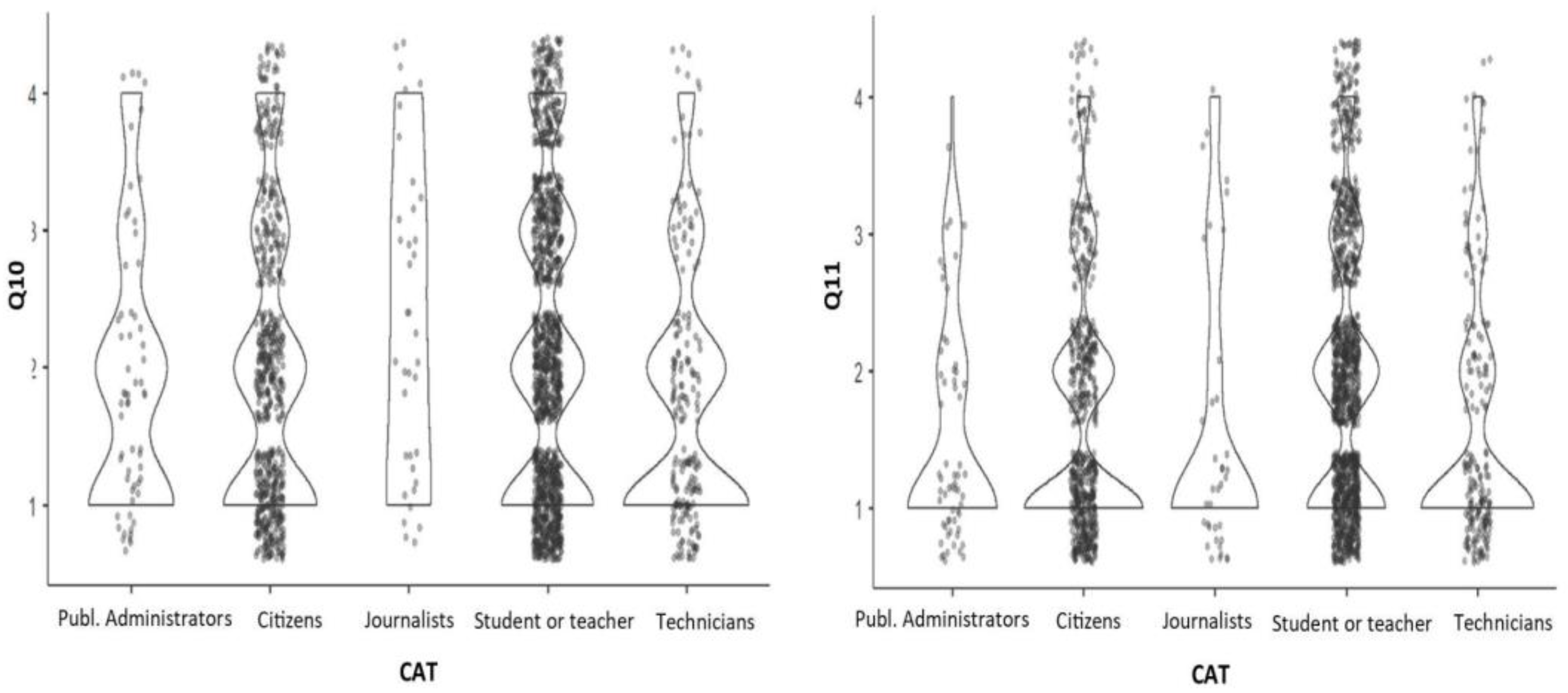

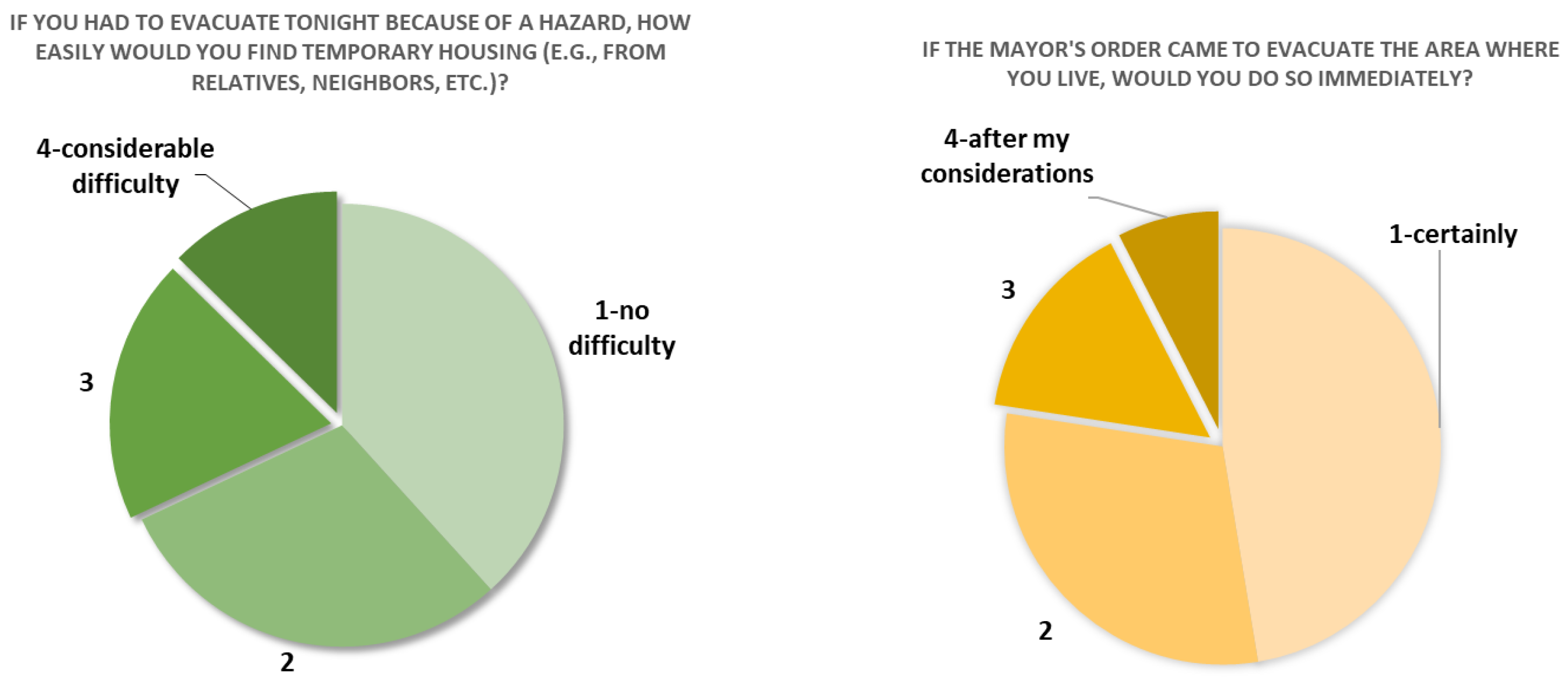

Concerning hypothetical individual resources and trust in institutions in case of emergency, the following graphs (

Figure 3) show the different responses regarding the assumed ability to find temporary accommodation and the supposed willingness to immediately follow an evacuation order. In practice, less than 40% would have no difficulty finding temporary accommodation on their own, and less than 50% would follow an evacuation order without hesitation.

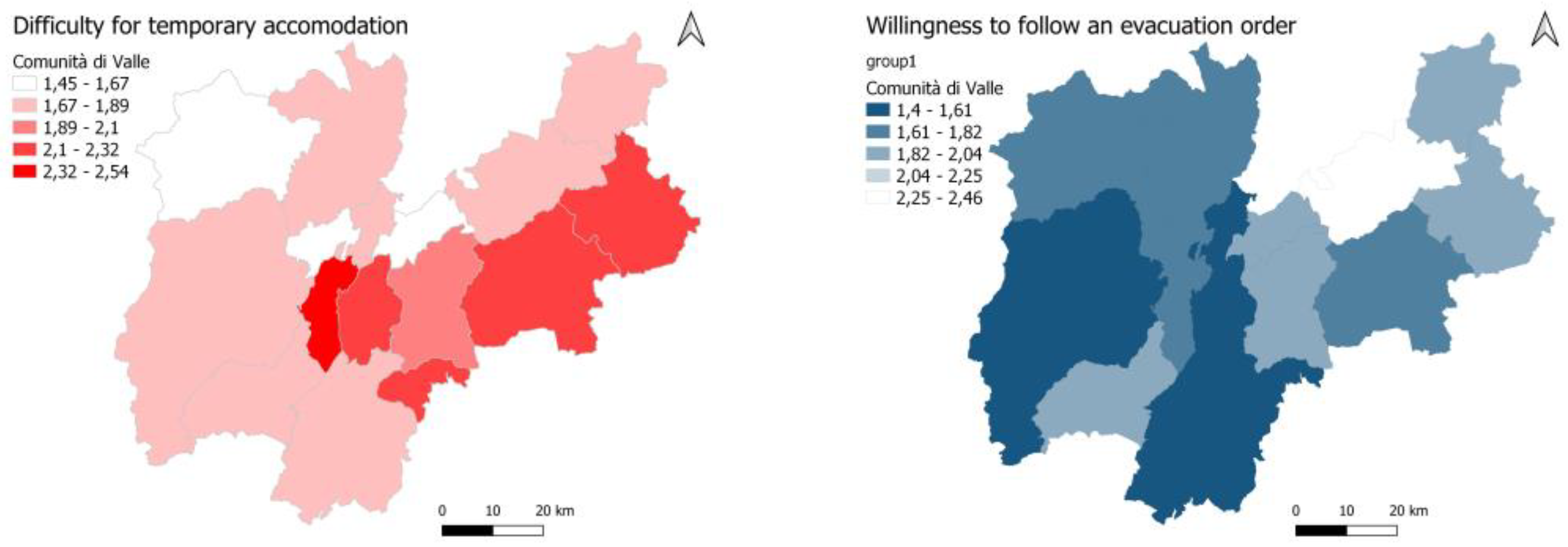

It is interesting to note that the responses to Q10 and Q11 appear spatially differentiated between the valley communities (with P< 0.001 and P< 0.012 respectively), and that they are positively correlated (P<0.001). This suggests that where individuals have more difficulty in facing an evacuation, they also show a slightly lower willingness to follow possible evacuation directives (

Figure 4).

The same questions show significant differences among the respondent categories (

Figure 6): “technicians” and “administrators” declare less difficulty facing an emergency than “journalists” and “students or teachers”; while only these latter declare themselves more willing to immediately follow a possible evacuation order than all the other groups. The education level and age significantly differentiate this propensity too, with an apparent greater “autonomy” of decision by graduates and young people.

Figure 5.

Responses Q10 and Q11 are differentiated between groups (note the shape of columns).

Figure 5.

Responses Q10 and Q11 are differentiated between groups (note the shape of columns).

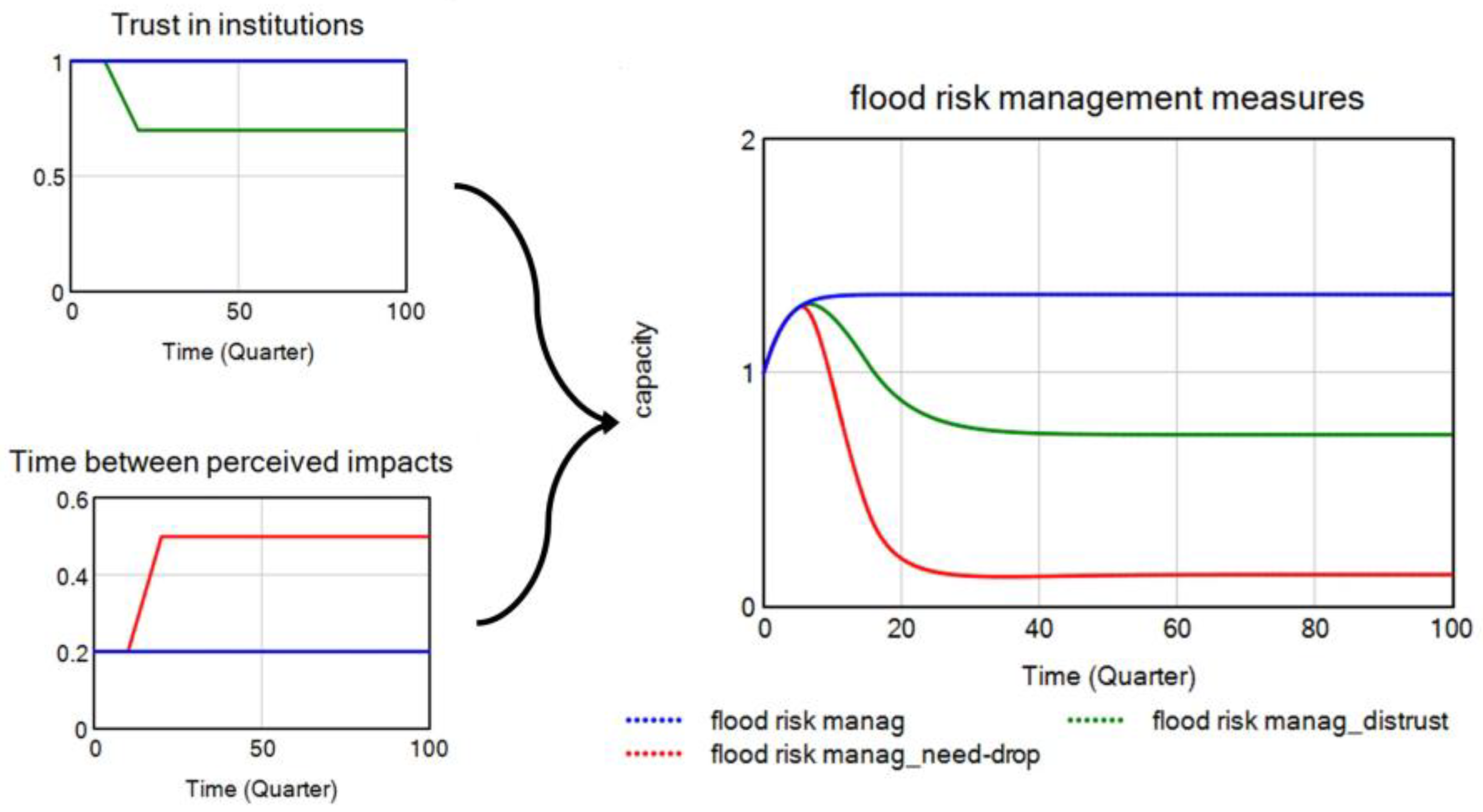

Figure 6.

Possible dynamics based on declining trust in institutions and declining perception of the need for flood management measures (the simulation model is accessible in the Supplementary material).

Figure 6.

Possible dynamics based on declining trust in institutions and declining perception of the need for flood management measures (the simulation model is accessible in the Supplementary material).

The Vaia storm seems to have affected the risk perception. The statement about the preparation of the Trentino population (Q1.4) changed: before Vaia most of people essentially agreed that the population “has few tools and lack of awareness”, after the event this agreement significantly diminished (with P < .001). After Vaia, the relevance for the respondents of “impermeability of the territory” significantly decreased while it increased the importance of the option “building new or more robust protection works (such as embankments or bridles)”. Surprisingly, Vaia seems to have affected the trust in institutions, resulting in a shift in the median of Q11 responses (from 1 to 2), meaning that after the event fewer respondents would be willing to follow hypothetical evacuation directives without hesitation.

In

Table 3 we report an extract of statistical analyses, with the significant differences between categories, for a complete picture see Table A2 in the Annexes.

Insights from the Qualitative Model

Considering the above supposed feedbacks and the survey results, we played with a simplified model to simulate two processes affecting over time the public support then the decision making about flood risk management: an increase in the community’s distrust in the public management of flood risks (green line); an increase in the time between perceived impacts of flood events that equates to a decrease in demand for measures (red line). Both processes lead to a decrease over time in support for flood management measures and consequently in the actual number of active measures. These emergent dynamics are typical of balancing feedbacks, which tend or oscillate around an equilibrium, after a certain delay, with a different equilibrium value that may change depending on the structure of the system (i.e., other related feedbacks), rarely considered in medium-term plans or policies

Again, the model is not intended as a numerical simulation tool, but rather a tool to reflect on the complexities of risk management and raise new useful questions. The numbers here are not associated with real measured variables, what matters is the qualitative behaviour over time, numerical models could be developed on this in future research. The oversimplified dynamics of trust and measure demand used in the model are actually much more complex; namely, trust can probably be intermittent, influenced by events and their narrative (both unpredictable in the medium term) by the media, institutions and citizen peers.

5. Discussion

On the whole, the respondents to the questionnaire show a good knowledge of the risks and their management: all factors considered most relevant for risk are included in several studies [

9,

12]. Most cited damages from flood events concern properties, agricultural activities and common areas correspond to those recorded by the responsible public offices (unpublished data from the Mountain Basin Service of Trento Province). The perception is also in line with current knowledge, for example that the frequency of flood events is expected to increase due to climate change [

35]. The responses are generally in line with similar studies, some carried out in adjacent or analogous study areas [

29,

36]. Besides, the majority of respondents remember flood events or their consequences from first-hand experience. All of these factors are assumed to help keep public interest and support for risk management measures high.

The collected responses do not allow us to say anything about those who did not respond and live with the same risks; nonetheless, the difference between groups is interesting. The categories of respondents, education, and age group were the factors that most differentiated the responses to the questionnaire. The distinction between “categories” of respondents differs from similar studies, in which the sample is clustered according to the usual sociological categories such as gender, age, educational qualification or income [e.g., 9,37,39]. Although there is no objective validation of self-attribution in the five categories, the responses offer operational insights regarding risk governance and attention to the activities carried out by people; for example, commuting workers and students, public employees, technicians and other citizens may perceive risk and alerts differently and may react differently to public emergency indications.

This suggest that non-structural measures of risk management (communication, participation, training) should not consider the target population as a homogeneous community but must be differentiated by groups, differentiated by dedicated analyses. In this regard, a person-centered approach could be functional, typical of design thinking in which the users of the proposed services are carefully characterized on the basis of “personas” models, which include values and preferences as well as levels of knowledge and habits [

40].

An interesting aspect related to this is the difference between categories regarding the willingness to follow a hypothetical invitation to evacuate by the mayor: “administrators” and “technicians” seem to follow the evacuation instructions with more hesitation than the group of “students or teachers”. Having only 47% of people who would follow an evacuation order without hesitation is equivalent to having 100 fire extinguishers to put out a fire of which only 47 work immediately, this could be a serious Civil Protection problem, easily overlooked in Municipal Emergency Plans (personal communication by local mayors). Furthermore, the spatial heterogeneity of the responses to Q10 and Q11 raises further questions on communication strategies, suggesting that in addition to being targeted by category, the dialogue between institutions and the population must be differentiated and cultivated locally, albeit with a possible central (provincial) coordination; risk communication should be understood as a dialogic process aimed at building trust between citizens and institutions [

41]. For example, it may be useful to define specific training for particular groups (such as local administrators, communicators or journalists and technicians) and widespread information on flood risk management differentiated for citizens of different ages and different areas. Today, citizens’ trust in institutions is severely tested in times of fake news and an easy overestimation of own knowledge or generalisation errors (“this has never happened here, so it cannot happen”, said an “expert” interviewee).

The fact that only 40% would have no difficulty finding temporary accommodation on their own also raises several issues rarely considered by flood risk managers. The fact that 60% have some difficulty in finding temporary accommodation raises several issues related to the concept of community resilience that are rarely considered by flood risk managers. A community is resilient when it demonstrates the ability to manage and adapt to a shock (e.g., earthquake, landslide, debris flow), to the extent that its members are interconnected and work together to be able to sustain critical systems (health, communications, accessibility, economic activities) even under stress; increase self-sufficiency in case of limited or temporarily interrupted external resources (water, food, energy); learn from experience to improve resilience as a community, adapting to environmental, social and economic changes, without losing the community identity [

42].

The inclusion of data around the Vaia storm (2018) captures a rare and significant opportunity to observe shifts in public perception following an extreme event. Such insights are critical for understanding how crises can alter societal attitudes toward risk and management strategies, which remains relevant as extreme weather events continue to rise due to climate change. The presented study can be considered pre-post event study, similar to longitudinal studies that allow to evaluate the variability over time of subjective and social factors of awareness [

43,

44].

The system thinking perspective applied in the study helped to remember that risk awareness is the result of dynamic processes: subjective perceptions, interpretations, understanding, individual and collective ability to react in a functional way to an anticipated or ongoing adverse event, and the collective (community) ability to recover from the exceptional event are all interdependent [

29]. The conceptual model shown (stock-flow) illustrates the minimum systemic structure able to explain the non-linearity of causal connections between perception and support for risk management measures. The real dynamics are much more complex than those over-simplified and shown. For example, trust or distrust in public institutions could be more fragmented, opposed between different social groups, and much more mobile, with fast peaks due to amplifications of the media and social media.

The results suggest research questions regarding how flood risk management measures may interact with support over time and regarding value and social components in risk management in terms of anticipatory governance [

45,

46]. These elements will be increasingly relevant in terms of enabling conditions for community resilience; to cultivate these conditions, it will be important to respond to and monitor people’s knowledge about the state and trends of the systems that sustain their lives, livelihoods, and society, their trust in leaders, their ability to frame problems for effective action in complex social-ecological contexts, and their preparedness to collaborate effectively in situations of uncertainty [

47].

6. Conclusions

A key lesson from this study concerns the relevance of a systems thinking and a future-oriented perspective; these elements should be explicitly considered in studies and evaluations of risk management policies in order to support their sustained improvement over time and not fall back in tough times. This implies understanding the “dynamic complexity”, which arises from the interactions among the agents in a system over time [

48], in addition to the comprehension of “detail complexity” [

49], more associated with forecasting models.

We have verified that an extreme weather event is able to influence not only the concern about flood risks but even the trust in the institutions. We found confirmation that lay people’s mental models derive from shared knowledge and personal experiences [

10], and that the risk is not a mere probability but a process that is continuously updated and influenced by interactions between subjects and events. This could constitute serious problems of public security, strongly connected with transparency and sharing the responsibilities in risk management, all these are emerging as issues of increasing complexity in an increasingly connected society. For this reason, building and maintaining trust in institutions should be included in the objectives of non-structural measures of flood risk management, as well as others such as information and training.

This highlights how an event is able to change perceptions, beliefs, and even trust in institutions, and it can suggest something useful after calamitous events: not only restore the functionality of activities and services, but also collect information on how the beliefs of the affected population have changed and involve the population together with institutional actors in a reflection on the consequences of the event and on the response capacity that emerged. This could foster social learning, as well as technological and scientific learning, which can improve community resilience in dealing with future events.

We have outlined qualitative dynamics that can offer interesting insights specifically for risk management. From these it is visible a balancing dynamic, which means that the support for risk management measures, then their number, might decline as they work (or seem to work), with the risk of not improving the conditions of a territory beyond a certain threshold and that this threshold is sensitive to external events (weather) and to internal process (within communities).

All this suggests some issues to explore in further research such as: how risk mitigation measures can be sustained with public support over time; how risk perception can change and influence the public support for risk management over time; in which conditions local community resources and social capital can increase the trust in institutions (creating synergies) and in which other conditions the opposite may happen (causing the system archetype named “accidental adversaries”).

From these considerations, the complexity of socio-hydrological processes is called into question and is perhaps greater than that considered in current practice of public bodies. Systems thinking tools, as causal model, showing key feedback loops, helps to see the big pictures and to understand how the interventions and measures for managing flood risks could interact with each other over a medium or long period. Based on these results, we can conclude that a more future-oriented and anticipatory approach should be further developed and possibly translated into evaluation criteria to monitor and improve the impacts of flood risk management measures in the medium and long term.

Acknowledgements

R.S. gratefully acknowledge ‘ARS_01_00964 Mitigo Project’, funded by Italian National Operational Programme on Research and Innovation (‘PON’, MIUR, 2014-2020); the LIFE FRANCA project was funded by the European Commission LIFE15 GIC/IT/000030.

References

- Bui, D. T., Ngo, P.-T. T., Pham, T. D., Jaafari, A., Minh, N. Q., Hoa, P. V., & Samui, P. (2019). A novel hybrid approach based on a swarm intelligence optimized extreme learning machine for flash flood susceptibility mapping. CATENA, 179, 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Luan, Q., & Chen, X. (2020). Flash floods, land-use change, and risk dynamics in mountainous tourist areas: A case study of the Yesanpo Scenic Area, Beijing, China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101873. [CrossRef]

- Nisi, L., Martius, O., Hering, A., Kunz, M., & Germann, U. (2016). Spatial and temporal distribution of hailstorms in the Alpine region: A long-term, high resolution, radar-based analysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 142(697), 1590–1604. [CrossRef]

- Pham, B. T., Jaafari, A., Phong, T. V., Yen, H. P. H., Tuyen, T. T., Luong, V. V., Nguyen, H. D., Le, H. V., & Foong, L. K. (2021). Improved flood susceptibility mapping using a best first decision tree integrated with ensemble learning techniques. Geoscience Frontiers, 12(3), 101105. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A., González-Marco, D., Doorn, N., & Kortenhaus, A. (2008). Extreme values for coastal, estuarine, and riverine environments. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 46(sup2), 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Aitsi-Selmi, A., Egawa, S., Sasaki, H., Wannous, C., & Murray, V. (2015). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction: Renewing the Global Commitment to People’s Resilience, Health, and Well-being. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6(2), 164–176. [CrossRef]

- Boholm, Å., & Corvellec, H. (2011). A relational theory of risk. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 175–190. [CrossRef]

- Renn, O., Klinke, A., & van Asselt, M. (2011). Coping with Complexity, Uncertainty and Ambiguity in Risk Governance: A Synthesis. AMBIO, 40(2), 231–246. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, S., Abeling, T., Deeming, H., Fordham, M., Forrester, J., Jülich, S., Karanci, A. N., Kuhlicke, C., Pelling, M., Pedoth, L., & Schneiderbauer, S. (2017). Conceptualizing community resilience to natural hazards – the emBRACE framework. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 17(12), 2321–2333. [CrossRef]

- Carnelli, F., Mugnano, S., & Short, C. (2020). Local knowledge as key factor for implementing nature-based solutions for flood risk mitigation. Rassegna Italiana Di Sociologia, 2/2020. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of Risk. Science, 236(4799), 280–285. [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G., Viglione, A., Carr, G., Kuil, L., Salinas, J. L., & Blöschl, G. (2013). Socio-hydrology: Conceptualising human-flood interactions. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17(8), 3295–3303. [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, G. D., Nohrstedt, D., Mård, J., Burchardt, S., Albin, C., Bondesson, S., Breinl, K., Deegan, F. M., Fuentes, D., Lopez, M. G., Granberg, M., Nyberg, L., Nyman, M. R., Rhodes, E., Troll, V., Young, S., Walch, C., & Parker, C. F. (2018). An Integrative Research Framework to Unravel the Interplay of Natural Hazards and Vulnerabilities. Earth’s Future, 6(3), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, C., Thiene, M., Di Baldassarre, G., Mondino, E., Scolobig, A., & Borga, M. (2021). Heterogeneity in flood risk awareness: A longitudinal, latent class model approach. Journal of Hydrology, 599, 126255. [CrossRef]

- Galloway, A. (2005). Non-Probability Sampling. In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Measurement (pp. 859–864). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2015). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Small, M. L. (2009). `How many cases do I need?’: On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography, 10(1), 5–38. [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, L., Davolio, S., Zaramella, M., Zardi, D., Borga., M. (2021). «Multi-Model Convection-Resolving Simulations of the October 2018 Vaia Storm over Northeastern Italy». Atmospheric Research 253: 105455. [CrossRef]

- Babcicky, P., & Seebauer, S. (2016). The two faces of social capital in private flood mitigation: Opposing effects on risk perception, self-efficacy and coping capacity. Journal of Risk Research, 0(0), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, L., Mackee, J., & Gajendran, T. (2018). The influence of cognitive and affective risk perceptions on flood preparedness intentions: A dual-process approach. Procedia Engineering, 212, 1203–1210. [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. (2000). Factors in Risk Perception. Risk Analysis, 20(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Willis, H. H., & DeKay, M. L. (2007). The Roles of Group Membership, Beliefs, and Norms in Ecological Risk Perception. Risk Analysis, 27(5), 1365–1380. [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T., & Reusswig, F. (2006). People at Risk of Flooding: Why Some Residents Take Precautionary Action While Others Do Not. Natural Hazards, 38(1), 101–120. [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J. D. (2002). All models are wrong: Reflections on becoming a systems scientist. System Dynamics Review, 18(4), 501–531. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M., Portney, K., & Islam, S. (2016). A question driven socio-hydrological modeling process. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 20(1), 73–92. [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C., & Kuhlicke, C. (2013). The Risk Perception Paradox—Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Analysis, 33(6), 1049–1065. [CrossRef]

- Creach, A., Bastidas-Arteaga, E., Pardo, S., & Mercier, D. (2020). Vulnerability and costs of adaptation strategies for housing subjected to flood risks: Application to La Guérinière France. Marine Policy, 117, 103438. [CrossRef]

- Miceli, R., Sotgiu, I., & Settanni, M. (2008). Disaster preparedness and perception of flood risk: A study in an alpine valley in Italy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Mondino, E., Scolobig, A., Borga, M., & Di Baldassarre, G. (2020). The Role of Experience and Different Sources of Knowledge in Shaping Flood Risk Awareness. Water, 12(8), 2130. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E., Brereton, F., Shahumyan, H., & Clinch, J. P. (2016). The Impact of Perceived Flood Exposure on Flood-Risk Perception: The Role of Distance. Risk Analysis, 36(11), 2158–2186. [CrossRef]

- Viglione, A., Di Baldassarre, G., Brandimarte, L., Kuil, L., Carr, G., Salinas, J. L., Scolobig, A., & Blöschl, G. (2014). Insights from socio-hydrology modelling on dealing with flood risk – Roles of collective memory, risk-taking attitude and trust. Journal of Hydrology, 518, 71–82. [CrossRef]

- Babcicky, P., & Seebauer, S. (2019). Unpacking Protection Motivation Theory: Evidence for a separate protective and non-protective route in private flood mitigation behavior. Journal of Risk Research, 22(12), 1503–1521. [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, T. (2011). Emotions, Trust, and Perceived Risk: Affective and Cognitive Routes to Flood Preparedness Behavior. Risk Analysis, 31(10), 1658–1675. [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. (2004). Why has feedback systems thinking struggled to influence strategy and policy formulation? Suggestive evidence, explanations and solutions. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 21(4), 331–347. [CrossRef]

- Gobiet, A., Kotlarski, S., Beniston, M., Heinrich, G., Rajczak, J., & Stoffel, M. (2014). 21st century climate change in the European Alps—A review. Science of The Total Environment, 493, 1138–1151. [CrossRef]

- Rufat, S., Tate, E., Burton, C. G., & Maroof, A. S. (2015). Social vulnerability to floods: Review of case studies and implications for measurement. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, 470–486. [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, P., Botzen, W. J. W., Laudan, J., Aerts, J. C. J. H., & Thieken, A. H. (2018). Insights into Flood-Coping Appraisals of Protection Motivation Theory: Empirical Evidence from Germany and France. Risk Analysis, 38(6), 1239–1257. [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S., Fontanella Pisa, P., Delves, J. L., Pedoth, L., Rufat, S., Erschbamer, M., Thaler, T., Carnelli, F., & Granados-Chahin, S. (2021). Risk perception of climate change and natural hazards in global mountain regions: A critical review. Science of The Total Environment, 784, 146957. [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, G. D., Nohrstedt, D., Mård, J., Burchardt, S., Albin, C., Bondesson, S., Breinl, K., Deegan, F. M., Fuentes, D., Lopez, M. G., Granberg, M., Nyberg, L., Nyman, M. R., Rhodes, E., Troll, V., Young, S., Walch, C., & Parker, C. F. (2018). An Integrative Research Framework to Unravel the Interplay of Natural Hazards and Vulnerabilities. Earth’s Future, 6(3), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Syed, F., Shah, S. H., Waseem, Z., & Tariq, A. (2021, September 3). Design Thinking for Social Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review & Future Research Directions. International Conference on Business, Management & Social Sciences, Rochester, NY. [CrossRef]

- Scolozzi, R. (2023). “If It Happens Again I’m Leaving”: Suggestions for Risk Communication from a Field Study of Communities in Basilicata, Italy. Fuori Luogo Journal of Sociology of Territory, Tourism, Technology, 17(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Koliou, M, van de Lindt, J.W., McAllister, T.P., Ellingwood, B.R., Dillard, M, & Cutler H. (2018): State of the research in community resilience: progress and challenges, Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure. 5)3), 131-151. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P., Thieken, A. H., & Bubeck, P. (2020). The challenges of longitudinal surveys in the flood risk domain. Journal of Risk Research, 23(5), 642–663. [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, P., Mondino, E., Borga, M., Di Baldassarre, G., Patt, A., & Scolobig, A. (2020). A flood-risk-oriented, dynamic protection motivation framework to explain risk reduction behaviours. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 20(1), 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E., Nykvist, B., Borgström, S., & Stacewicz, I. A. (2015). Anticipatory governance for social-ecological resilience. Ambio, 44(1), 149–161. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Guston, David H. 2014. «Understanding ‘anticipatory governance’». Social Studies of Science 44 (2): 218–42. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. R., Arrow, K. J., Barrett, S., Biggs, R., Brock, W. A., Crépin, A.-S., Engström, G., Folke, C., Hughes, T. P., Kautsky, N., Li, C.-Z., McCarney, G., Meng, K., Mäler, K.-G., Polasky, S., Scheffer, M., Shogren, J., Sterner, T., Vincent, J. R., … Zeeuw, A. D. (2012). General Resilience to Cope with Extreme Events. Sustainability, 4(12). [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J. D. (2002). All models are wrong: Reflections on becoming a systems scientist. System Dynamics Review, 18(4), 501–531. [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. M., & Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 137–150. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).