1. Introduction

1.1. Background Study

Semantic segmentation plays an important role in enabling autonomous vehicles, such as self-driving cars, to comprehend and navigate their surroundings smoothly and effectively. It is a widely used perception method for self-driving cars that associates each pixel of an image with a predefined class [

1]. This technique involves a very precise labelling of each pixel in an image with its corresponding class, providing crucial information for real-time decision making. Compared to image recognition and target location and detection, semantic segmentation not only provides object classification information, but also extracts location information, which lays the foundation for other computer vision tasks [

2,

3]. The achievement of high accuracy and computational efficiency in semantic segmentation is essential for the safe and efficient operation of autonomous vehicles. Furthermore, the success of autonomous vehicles depends on the achievement of a delicate balance between accuracy and computational efficiency in semantic segmentation algorithms. Good accuracy ensures reliable scene understanding and decision-making, and computational efficiency is crucial for real-time operations. Ongoing research and development efforts in semantic segmentation focus on optimizing algorithms to achieve superior performance metrics while minimizing computational complexity and resource requirements, which is very important especially in a resource-constrained model.

A self-driving car is capable of understanding its environment and operating with less human intervention [

4]. For autonomous driving to be successful, cars must be able to collect and process data from their surroundings in real time using cameras and sensors to create a complete picture of driving conditions [

5]. These cars mainly depend on the information collected by their sensors [

6]. These cars use a variety of advanced sensors, cameras, and computer vision algorithms to perceive their environment and make decisions.

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) and other deep learning techniques have recently been used to achieve sophisticated results in picture segmentation and classification [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These networks are made up of layers that can learn the information’s understructure from multilevel data. Since the characteristics that make up these layers are learned from the data and do not require human design, deep learning techniques can efficiently extract features on their own, saving time and effort [

10]. CNNs have shown good results in medical analysis, such as segmentation of brain tumors [

11], liver tumors [

12], and pancreatic tumors [

4], as well as in computer-aided diagnostic applications [

13] to improve body health.

In medical annotated data sets, the U-Net architecture is known for its good performance. It has a symmetric encoder-decoder structure with skip connections that combine the corresponding decoder layers with high-resolution encoder features. This design helps the model retain spatial information, making U-Net particularly effective for tasks requiring precise segmentation. Initially developed for biomedical image segmentation, U-Net has shown good performance in many domains, including self-driving cars. This paper uses a U-Net structure neural network on a Cityscapes dataset with the use of ResNet101 as its encoder for feature extraction.

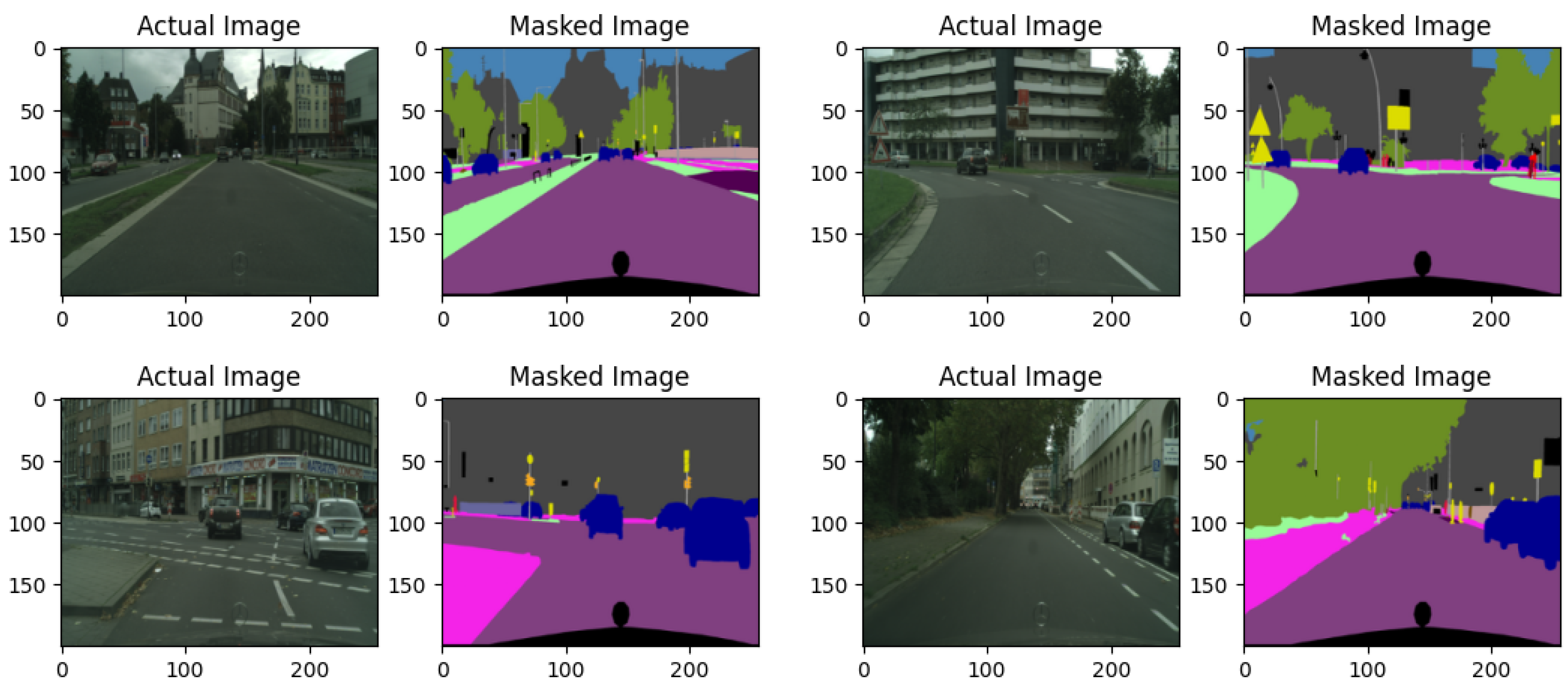

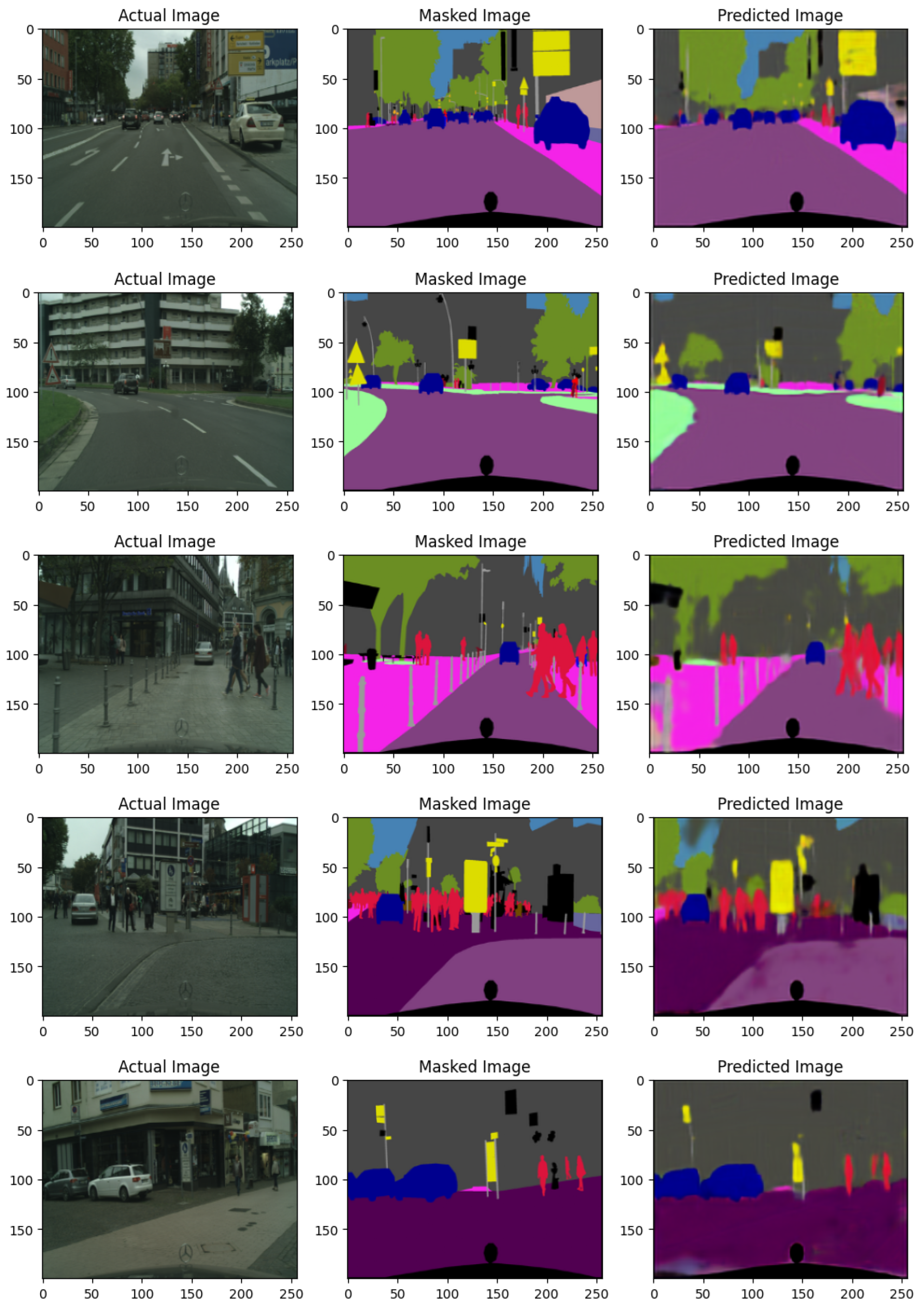

This paper describes the implementation of a widely used medical imaging architecture known as U-Net on a cityscape dataset for semantic segmentation in the context of autonomous driving. A typical driving scene is shown in

Figure 1. By adapting this architecture to the cityscape dataset, we demonstrated that the model has great accuracy in semantic segmentation tasks, which are critical for autonomous vehicles to understand their surroundings. This technique not only highlights the versatility of U-Net, but also investigates its potential uses beyond its initial medical imaging domain, offering vital insights into the realm of autonomous driving technology.

1.2. Motivation

Moreover, this study is motivated by a rise in road accidents, which continue to claim the lives of many people both in the Gambia and globally as a result of reckless driving. The World Health Organization (WHO) statistics reveal a statistics — around 1.3 million people are killed due to road accidents each year [

14]. Even more tragically, children and young adults aged 5-29 years make up a disproportionate number of these fatalities; they are in fact the leading cause of death for that demographic [

14]. To avoid such tragedies, this study is set to make substantial contributions towards ongoing efforts in improving road safety and reducing the incidence of road accidents by using ResNet101 which has 101 layers for the feature extraction of the U-Net model, making it a good choice for the cityscape dataset.

This paper contributed to the effort by leveraging U-Net model previously designed for medical imaging such as X-rays on a cityscape dataset which contains more annotated images than a medical dataset. Using ResNet101, which features 101 layers for efficient feature extraction within the U-Net model, the study delivered good segmentation results, making it particularly well-suited for complex scene environments.

1.3. Problem Statement

Accurate semantic segmentation is a critical task in computer vision, for the application of autonomous driving, where understanding and interpreting urban scenes is crucial for the safety of life and property as for self-driving cars are concerned. Datasets like Cityscape pose significant challenges due to the complexity and diversity of urban environments, including varying day-lighting conditions, occlusions, and class imbalances. Accurate segmentation should involve good identification of common objects such as roads, vehicles, and pedestrians while maintaining high accuracy across all the classes. Traditional FCN approaches and other U-Net modifications have struggled to generalize well, especially for underrepresented classes and objects with irregular shapes in a complex scene environment. Thus, highlights the need for a U-Net model with RestNet 101 for the feature extraction capable of effectively capturing both local and global contexts to achieve a very good performance, as measured by the metrics; Pixel Accuracy and Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). Solving this problem is crucial for ensuring safety and reliability in the applications of self-driving cars, thus minimising road accidents and making autonomous vehicles smarter.

The key contributions of the paper include the following:

The use of a U-Net model in a cityscape dataset. The model is trained and evaluated using the cityscape dataset, focusing on semantic segmentation for self-driving scenarios.

The use of ResNet101 as the encoder backbone for better feature extraction and performance.

The use of a proprietary scaling layer to enable seamless upsampling and concatenation, which improves the model’s ability to capture various elements such as trees, vehicles, and road signs.

It incorporates scaling layers and a customized upsampling approach, which optimizes the model’s reconstruction of intricate, crowded cityscapes while maintaining the spatial features that are essential for segmentation.

2. Related Topics

2.1. Deep Learning for Image Segmentation

The main goal of the U-Net architecture was to address the issues of limited data in the medical field. It was designed to effectively analyze a smaller amount of data while maintaining a very computational effectiveness. Due to its versatility, it can also be used in CamVid and cityscape datasets to perform well. Other models such as PSPNet proposed by Hengshuang Zhao et al. in the paper titled "

Pyramid Scene Parsing Network" presented at CVPR 2017 had a remarkable performance. The model uses a pre-trained ResNet50 for feature extraction. This pre-trained are trained on ImageNet dataset for classification tasks. These features are then upsampled and passed through a pyramid pooling module. Global pooling, the 1x1 kenel side also calls the red channel followed by 2x2, 3x3, and 6x6 with a stride of 2. This model classified a segmented object in relation to the contextual information available within the surrounding. Other deep learning models use encoder-decoder, these types include fully convolutional networks (FCN) [

5], encoder-decoder-based techniques such as Segnet [

15], ERFNet [

16], and U-Net [

17], as well as ESPnetv2 [

18].

Segnet on the other hand has the advantages of feature extraction via a pre-trained encoder also, usually based on VGG16, and a novel decoding technique that uses pooling indices to preserve spatial hierarchies, this deep learning model uses an encoder-decoder framework to accomplish high-resolution pixel-wise classification. Recent publications have shown Segnet’s effectiveness and good performance in a lot of settings where accurate object segmentation is crucial, such as self-driving vehicles and medical imaging. Furthermore, a good performance is made possible by its lightweight architecture, which qualifies it for deployment in contexts with limited resources. Segnet is versatile in a range of applications highlighting its importance in the continuous advancement of semantic segmentation techniques as research advances.

2.2. Attention and Gating Mechanism

CNNs have recently improved in various vision tasks, including classification [

1], detection [

2], segmentation [

3], image captioning [

19], and visual question answering [

20] using attention mechanisms. Attention processes guide the model helping it focus on most important features and ignoring those not relevant to a particular task. To capture long-range dependencies, Wang et al. [

1] presented a residual attention network that uses non-local self-attention processes. Hu et al. [

21] introduced squeeze-and-excitation method for ILSVRC 2017 image classification with channel-wise attention computed to emphasize the valuable channels via global average pooling and surpassed the existing methods. An interesting work on self-attention was presented by Woo et al. [

22], wherein they proposed a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) that leverages both spatial and channel information allowing for effective feature refinement.

2.3. Other Variants and Modification

The Dilated-UNet model improves medical image segmentation by utilizing the advantages of the U-Net architecture and the Dilated Transformer blocks [

23]. The Dilated Transformer blocks help to portray a bigger background without compromising detail. The transformer manages the self-attention process across dilated patches in this configuration. This neural network, which has a U-shaped form and consists of an encoder and a decoder, is well-known for medical image segmentation. The decoder reconstructs the spatial resolution and provides comprehensive segmentations after the encoder progressively decreases the spatial dimensions while enhancing feature richness.

Numerous modifications have been made by developers over the recent years to U-Net’s performance. Attention U-Net[

23] is a version that integrates an attention gate to improve feature selection during segmentation, increasing sensitivity and prediction accuracy, especially in complex picture contexts.

2.4. Challenges and Existing Problems

Semantic and scene parsing segmentation have made progress, yet several challenges remain. A significant problem is achieving precise real-time performance. In autonomous driving, swift decision-making is vital, the use of autrous convolution, which incorporates dilation rates to gather more contextual information, could result in latency issues due to computing requirements of deep learning models like PSPNet. Some models cannot give a general output of a particular segmented image. This is due to the fact that these models are models are only train a single dataset and could not function a road conditions, or unpredicted weather. The dependability and safety of autonomous cars can be jeopardized by this lack of robustness [

24]. Numerous tests and implementation of these model need to be carried out various model, not only on specific datasets. By doing so, we will come to the conclusion of the model best suited for autonomous vehicles.

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset

The Cityscape dataset is a very good choice when it comes to semantic segmentation in the context of autonomous driving due to its multiclass and various complex scenes in an urban area. The dataset is an urban scene image that contains all scene scenarios in a typical city. It includes 5,000 high-quality finely annotated pixel-level images gathered from 50 cities over various seasons. For training, validation and testing, the images are separated into sets with the numbers 2,975, 500, and 1,525. Identifies 19 categories or class that include both things and junk [

10]. In addition, two comparison settings are given, training with only fine data or training with both fine and coarse data, 20,000 coarsely annotated images [

25].

The dataset supported the experiment’s goals by tackling important issues in semantic segmentation such as accuracy in a complex scene environment and scene comprehension, both of which are crucial for the field of computer vision, especially self-driving cars and typical urban scene analysis. The data has various driving scenarios making it the best choice for our paper.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Download and Resize: First, the dataset is downloaded and uploaded in Kaggle cloud environment for storage. The images are then resized to 200x256 pixel as shown in

Figure 2 below and stored in their respective directories. For consistency in the models’ training and assessment, the images are then scaled procedure entails methodically modifying the sizes of the images in the Cityscapes dataset. This procedure is essential for maximizing models’ performance within the free limited resources available on the kaggle environment. I also make use of the Pillow Library (PIL), which enables effective image file manipulation. The compatibility with different neural network architectures is made easier by this standardization. To make sure that all pertinent images are handled, the script looks for suitable image formats, particularly .png,.jpg, and.jpeg.

Normalization and Dataset creation: The images are then normalized between the range of [0,1] by dividing by 255.0 into three channels known as the RGB color standardization. Normalization helps the models to train more effectively by standardizing each pixel values, thus reducing computational cost and speeding up the convergence of the model.

The normalization of pixel values is performed using the following formula:

Where:

image represents the original value of the pixel.

is the normalized pixel value.

confines the value x within the range .

3.3. Data Augmentation

This technique is employed to expand the dataset to have better training quality images such as random flip, scaling, and increasing the brightness of the preprocessed images; this therefore prevented model from overfitting and improved the model performance etc.

Random Horizontal and Vertical Flip The images are then flip horizontally and vertically with a probability of 50%. Equation (

2) represents the horizontal flip and Equation (

3) represents the vertical flip, where W is the width of the image and H is the height of the image.

Random Rotation The images are rotated by a random angle, within a specified range rotation by -10 and 10 degrees for each pixel location (x,y)(x,y) is transformed. The equation below shows the transformation.

Gaussian Blur Blurs the image using a Gaussian kernel, it is in smoothing out noise and small details. The Gaussian kernel of size k×k and standard deviation

. This kernel is convolved with the image, applying by applying the Gaussian blur.

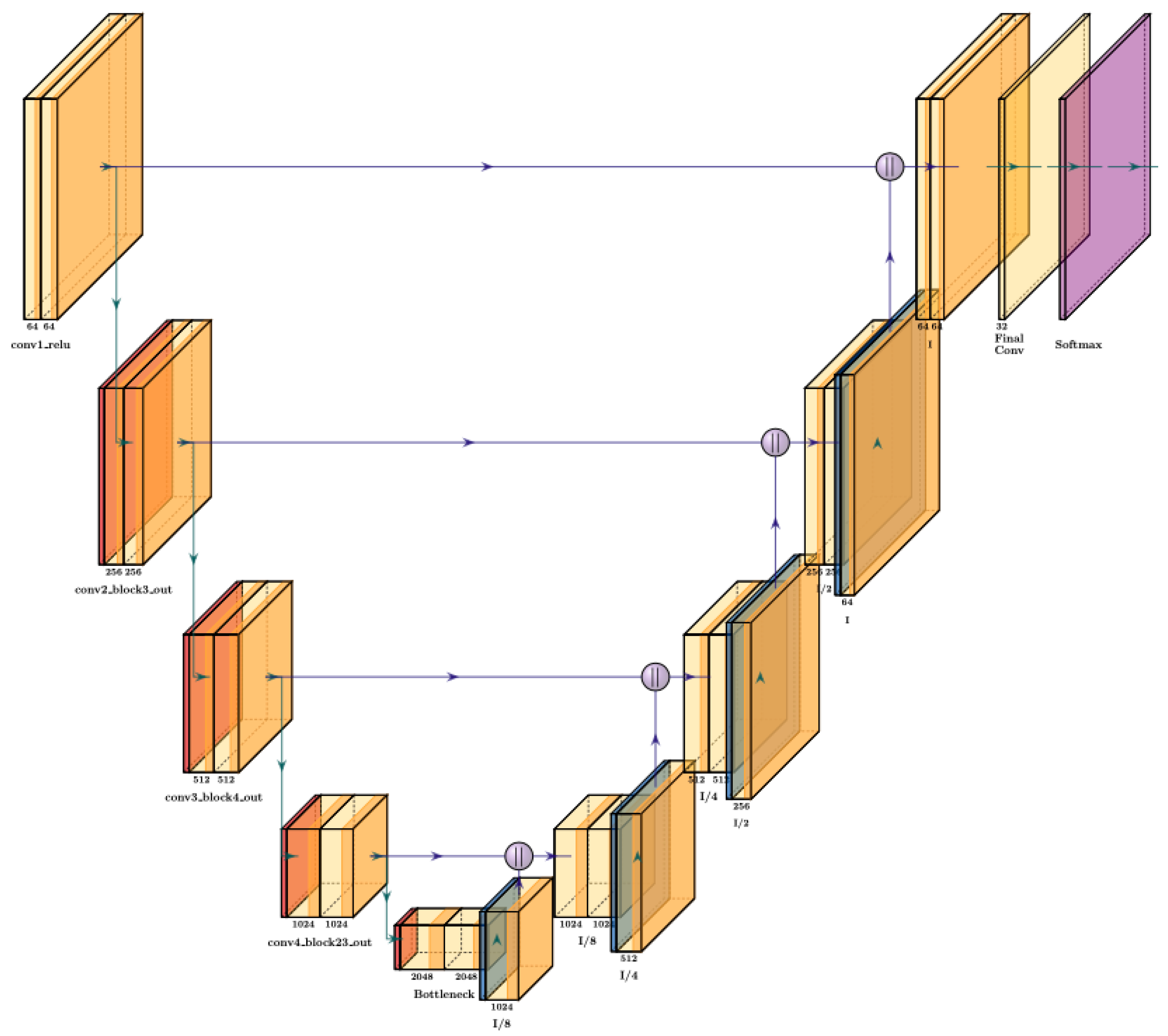

3.4. Model Architecture

U-Net is popular image segmentation model developed primary for biomedical imaging. It has been popular for its power encoder and decoder with skip connection which helps to retain useful spatial information during downsampling. The term U-Net described its U-shaped architecture of the network architecture [

26].

In our model architecture, the

encoder uses ResNet101 of five convolutional layers. ResNet101 is used for the feature extraction as the encoder, it contains 101 layers trained imageNet dataset for classification tasks. The encoder in our U-Net model as shown it

Figure 3 extracts increasingly abstract characteristics at various spatial scales by gradually downsampling the input image; each of these convolutional layers is followed by rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function. In order to restore spatial resolution, the decoder subsequently upsamples these features with the help of skip connections. Skip connections mix high-level features with fine-grained spatial details by connecting encoder and decoder layers at every scale. The input shape of the model (200, 256,3). The shape is then passed to ResNet101 , the model is trained to process images of that specified size. Resize layer used as a custom layer to resize feature maps to match dimensions during decoder upsampling. This therefore avoids the need for complex alignment techniques and allows you to resize feature maps to custom sizes.

The decoder then used UpSampling2D layers to upsample the feature maps back to the original of the input size. The feature maps from the encoder which is the ResNet101 are resized and concatenated with the upsampled maps, in a manner similar to U-Net.

4. Experimental Analysis

4.1. Experimental Condition

For the implementation of our model, we used the deep learning framework Tensorflow and keras libraries to perform the learning process and the testing phase on the kaggle storage of Maaximum of 57.6GiB and free available GPU’s of maximum 16GiB with a RAM 29GiB. The dataset was divided into three main partitions for train, test and validation. Our model runs for 75 epochs for 2 hours, producing steady learning. The learning rate used in this experiment is adam, which is a common choice for stable callbacks. The callbacks are tensor board which helps a good visualization of the model over the training period.

4.2. Loss Function

Categorical loss function is a common choice for multiclass semantic segmentation. Classifies each pixel with a distinct color of multiple objects in a single image. As a result, this loss function is used to calculate the difference between the data’s true distribution and the model’s expected distribution output. During training, the goal was to reduce the loss, which meant getting the predicted probabilities as close to the true distribution of class labels.

The categorical cross-entropy loss

L is defined as:

where:

C is the number of classes.

is the binary indicator (0 or 1) if class label i is the correct classification for a sample.

is the predicted probability that the sample belongs to class i.

4.3. Results and Discussion

The model has shown some notable results of 88% model accuracy, 75.32% of pixel accuracy, 80% of recall accuracy, precision of 72% and F1 score of 75.79%. This has shown that ResNet101 can be used for feature extraction as an encoder.

Figure 4 shows the original, masked and output of the predicted image on the cityscape dataset. With these results, the model has shown good efficacy in semantic segmentation tasks in the given dataset. Cityscape is particularly challenging due to its diverse range of object classes with varying lighting conditions, and different scales of objects found in typical urban environments scenario. The model characterized by its symmetric encoder-decoder with ResNet 101 for its encoder,and helps in feature extraction to capture of both local and global contextual information. This capability is crucial for accurately segmenting objects in images where the boundaries can be intricate and where context plays a vital role in determining object identity.

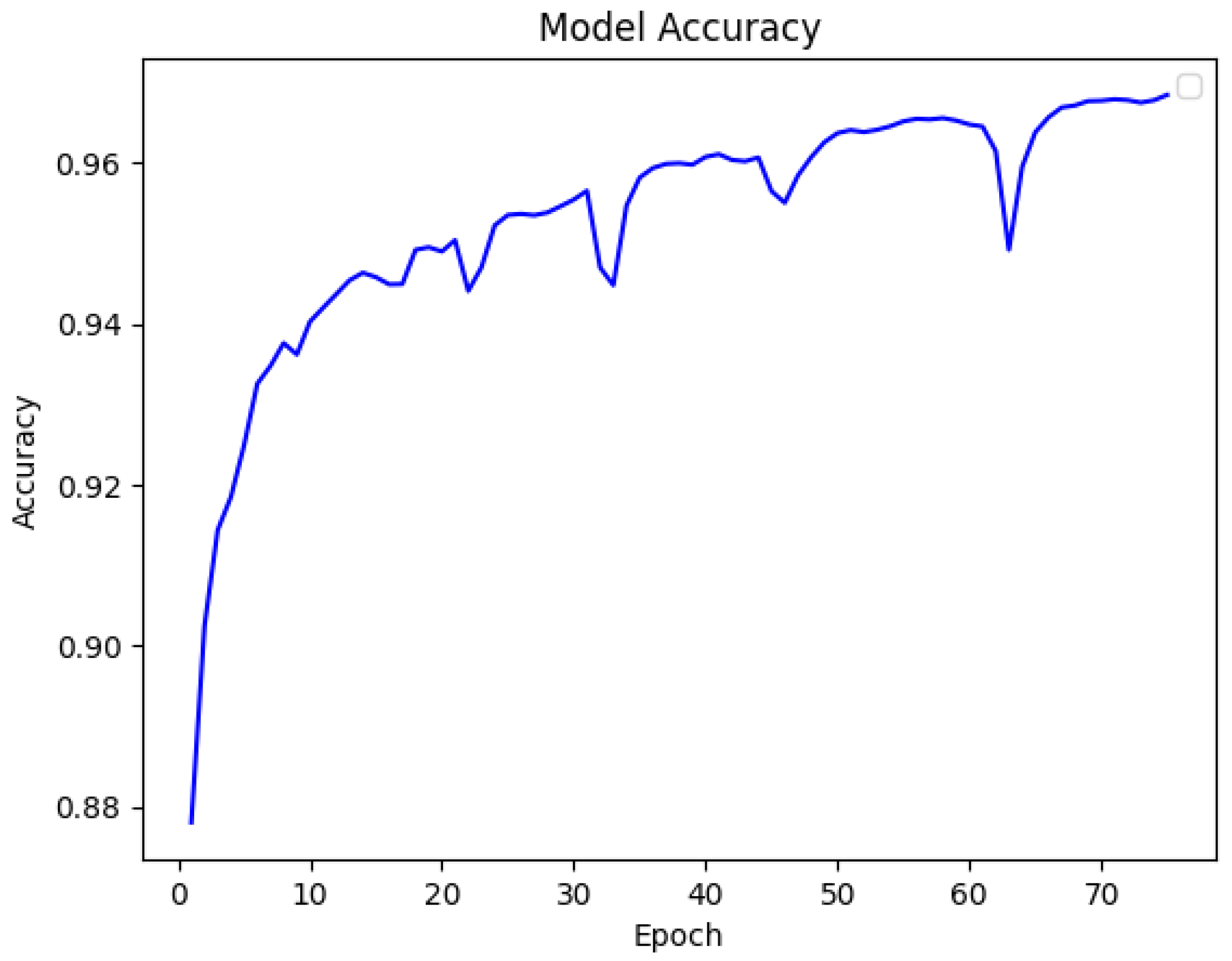

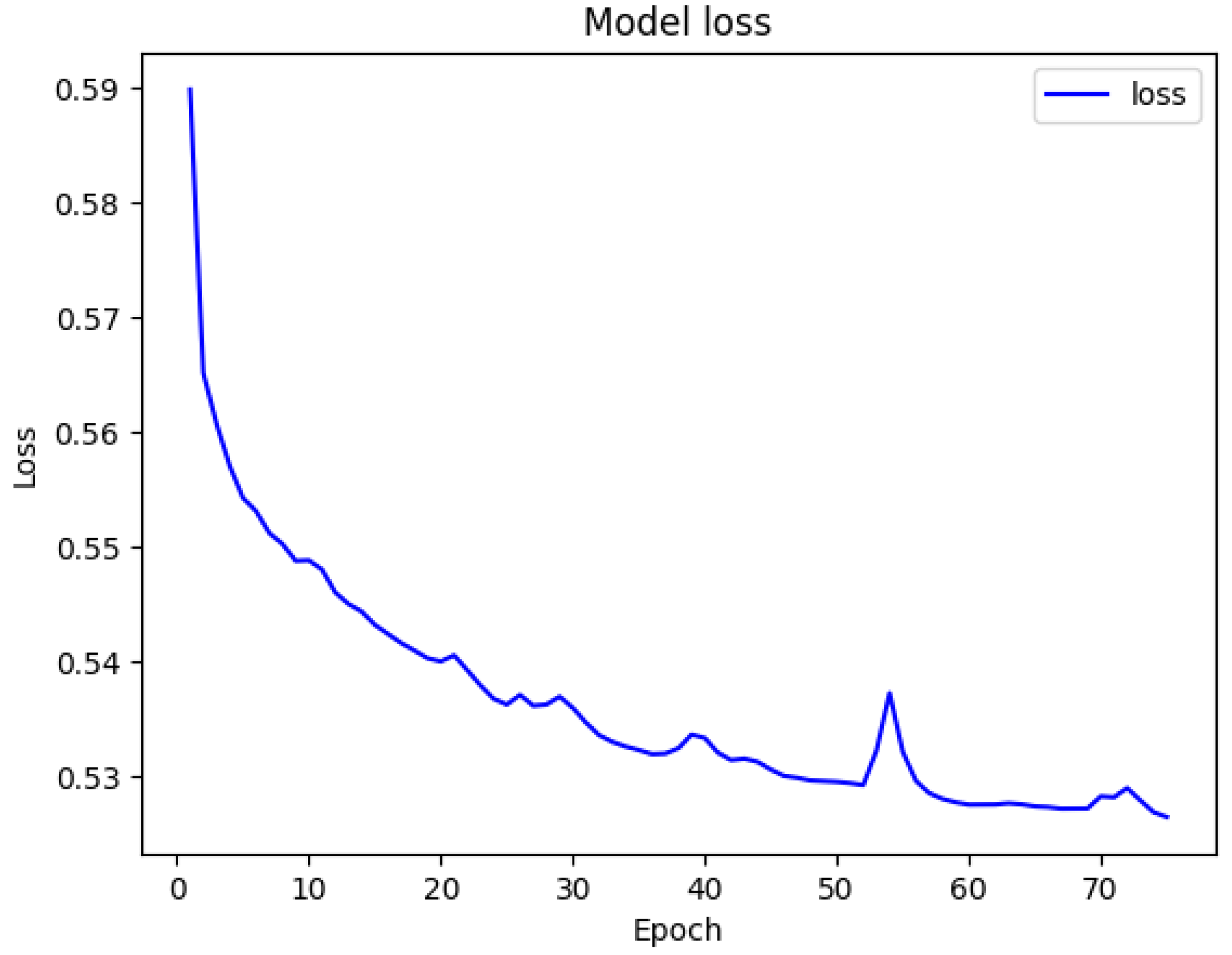

As presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, our model shows a significant accuracy, the values of the loss function have been gradually reduced over the 75 epochs used during the training. The training loss decreases gradually, indicating a very optimization. The model has proven that ResNet101 is also a good choice for encoding feature extraction. The model was able to capture all important details in a complex scene-parsing environment as illustrated in

Figure 4.

Therefore, the more complex a model is, the longer it takes to compute the output. This makes its usage in real-time applications difficult and time-consuming for a resource-constrained model.

4.4. Evaluation Metric

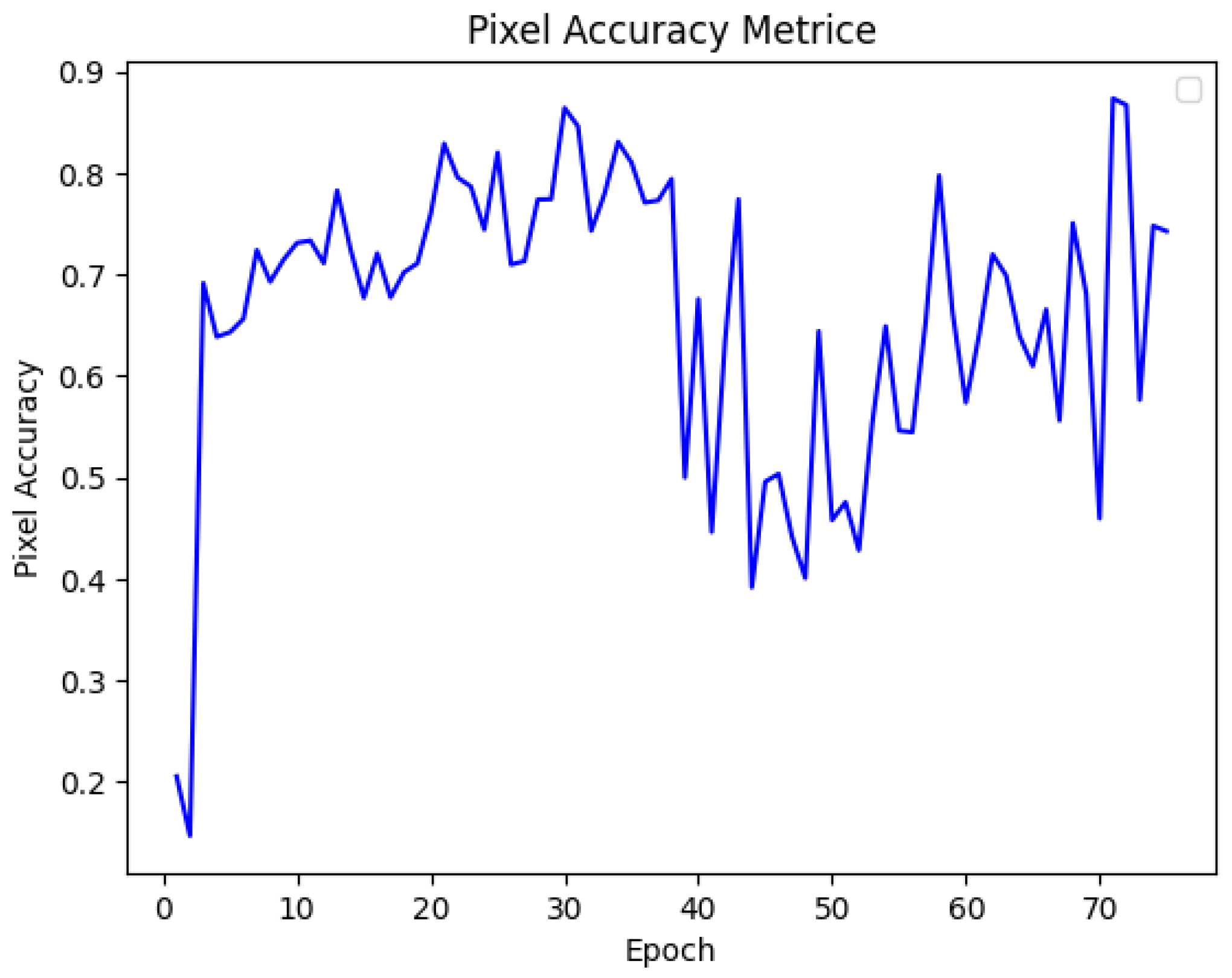

4.4.1. Pixel Accuracy

A common Pixel evaluation metric is used to further assess the model. Its calculate the percentage of the correctly identified pixels across all given classes, providing a simple but effective method for evaluating overall performance of the model. Pixel accuracy metric represents the proportion of correctly classified pixels relative to the total number of pixels available in the dataset. As shown in

Figure 7 in the pixel graph, the model shows a steady increase in accuracy over the 75 training epochs. The accuracy curve shows a little bit of fluctuations but generally trends upward. The model is able to learned from the dataset. By striking a balance between fitting the training data and generalising to new data, the model has achieved an optimal learning state, as indicated by the pixel accuracy towards the end of training process.

The equation for Pixel Accuracy is given by:

where:

N is defined as the total number of pixels in the image or across all images in the cityscape dataset.

is the predicted label for the pixel i.

stands for the true label for the pixel i.

is the indicator function that equals 1 if the predicted label matches the true label , and 0 otherwise.

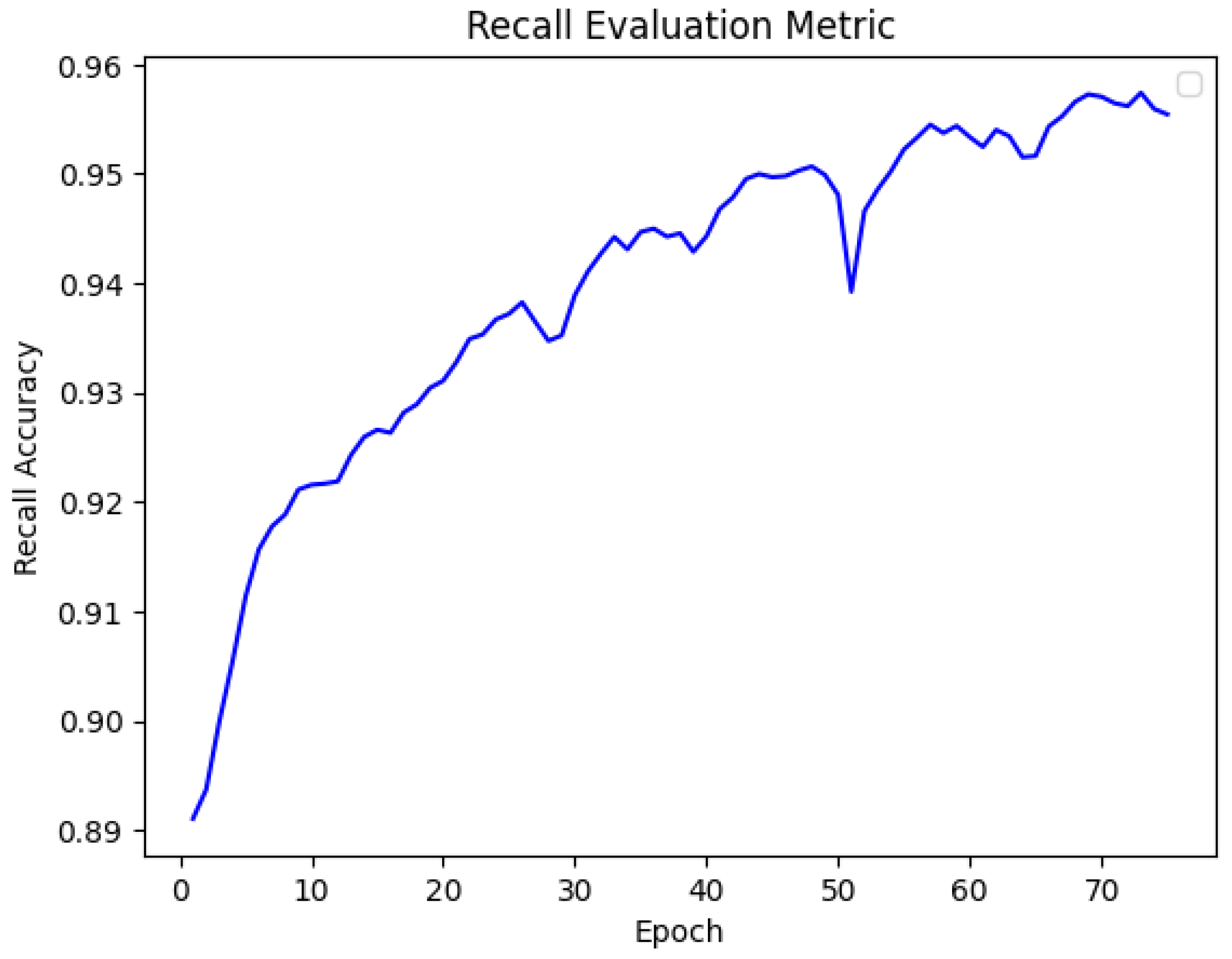

4.4.2. Recall

We further used Recall evaluation metric to further assessed our model by measuring the percentage of real positive sample that the model accurately detected. False Negatives (FN) are situations in which real positive examples are incorrectly classified as negative, whereas True Positives (TP) are samples in which the model correctly predicted a positive class. Thus, our model achieved 96% recall accuracy. Recall is particularly significant in safety-critical applications in autonomous driving, where missing critical objects can lead to severe consequences. It is a crucial parameter for guaranteeing thorough detection because, for example, failing to detect pedestrians, cars, or traffic signs (false negatives) might cause fatal accidents.

In our task that involves pixel-wise classification of an image, present unique challenges. The cityscape dataset includes small, overlapping, or occluded objects, which are prone to being misclassified as background, leading to false negative values. The Recall metric has shown that the model managed these difficulties well, especially for classes of objects that are difficult to detect, and improves its capacity to precisely segment all pertinent objects. Moreover, recall prioritizes the model sensitivity, which is critical for applications where the cost of missing an object is far higher than incorrectly identifying one. This aligned with the goals of autonomous vehicles. This emphasis on reducing missed detections highlights how crucial recall is as a criterion for improving autonomous systems’ usability and dependability in the real world.

Figure 6 shows the graphical analysis of the metric over the 75 epochs.

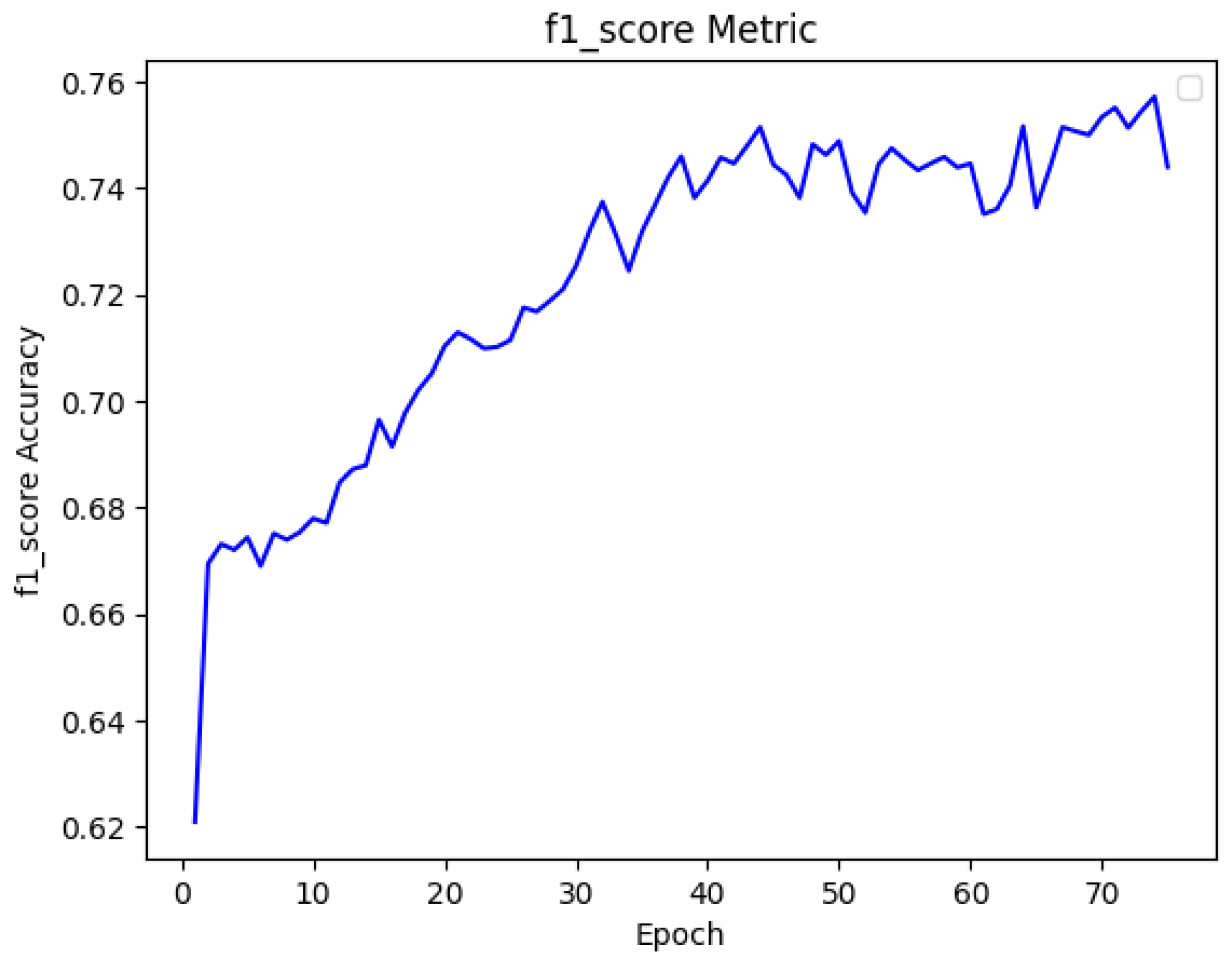

4.4.3. F1 Score

We further analysed with F_1 score which is a harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced evaluation metric for our proposed model, where there are imbalance class distributions. Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positives among all predicted positives. As we mentioned earlier, Recall measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified. The F1 score is particularly relevant in our tasks, as it balances the trade-off between precision and recall. While high recall guarantees that all pertinent segments are found, high precision guarantees that the predicted segments are accurate. It provides a single, comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance when false positives and false negatives have different weights of relevance. This is crucial for autonomous driving since it guarantees that the model minimises false negatives, such as missing pedestrians or road signs, and prevents false positives, such as misclassifying safe regions as obstacles. Therefore, the F1 score is a crucial parameter for assessing models used in high-stakes, safety-critical applications where optimal performance requires striking a balance between precision and recall. The table shows the model accuracy with the evaluation metrics.

Where the precision is defined as;

Figure 9.

F_1 score graph.

Figure 9.

F_1 score graph.

Table 1.

Model Summary Results.

Table 1.

Model Summary Results.

| Model |

Accuracy % |

Precision % |

Pixel Accuracy % |

Recall % |

F_1 Score % |

| Proposed Model |

88 |

72 |

75.32 |

80 |

75.79 |

5. Future Directions

Even though our results are encouraging, there is still room to improve the model’s performance and resilience using other available evaluating metrics. Many techniques and steps can be employed to achieve this. The introduction of dropout layers can be used to reduce over-fitting. By pushing the model to learn more robust features that are less dependent on any one neurone, enhances the model’s capacity for generalisation and helps prevent over-fitting.

Transfer learning can be used with other pre-trained models like VGG16 on similar tasks to speed up the training process and improve performance. By fine-tuning pre-trained on other large-scale datasets, the model may learn from previously learned annotated data images. This is particularly helpful for small or sophisticated target datasets.

Segmentation accuracy may be increased by investigating changes to the U-Net architecture, such as using residual connections or adding attention methods. Additionally, attention techniques can be used to assist the model in disregarding less significant data and concentrating on relevant aspects. This will enhance the quality of segmentation in a complex scene scenario.

Combining predictions from multiple models, or employing ensemble learning techniques, can lead to improved performance by leveraging the strengths of different architectures. This approach could help to reduce the variance in predictions and enhance the overall accuracy of the segmentation task of the model.

6. Limitations

Limited Training Epochs: The model was only trained for 75 epochs due to computational and memory limitations within the Kaggle environment used in the experimental analysis. Due to this factor, the model was not able to fully converged. This has however, impacted the model’s overall performance. Higher resources would have given us the ability to train the with at least 150 epochs.

Reduced Batch Size: The model’s The model’s capacity to identify patterns in the dataset was limited by the smaller batch size of 16 that was used, particularly when dealing with images that have a high resolution, this small number leads to a lower accuracy. A larger batch size would have increased the accuracy of the model.

Smaller Image size: The size of the image has an impact on the model’s ability to generalize. Smaller image size leads to lower accuracy compared to large image sizes as the resolution of images is a bit compressed and important details might be left out. This has to be done in order to minimized the usage of the GPU.

Restricted Computational Resources: The restricted resources of the Kaggle environment made it a bit difficult to test deeper or increase the epoch number, therefore, the more complicated model is, greater fine-tuning, or comprehensive hyperparameter optimization of all of which could increase the accuracy and resilience of the model.

7. Summary and Conclusions

The proposed model successfully extracts detailed and contextually important information from images in a complex scene of the Cityscape dataset by utilizing the pre-trained ResNet101 architecture as an encoder. We obtained 88% accuracy, 72% precision, 75.32% pixel accuracy, 80% recall and 75.79% F1 score for 75 epochs.

In applications outside of the usual medical imaging datasets, this method has demonstrated that U-Net and ResNet101 can produce very effective semantic segmentation. The model effectively handles the inherent limitations of urban settings, identifying and classifying a wide range of classes relevant to autonomous driving.

This work emphasizes the versatility and scalability of U-Net-based architectures, especially in high-stakes applications that require exact scene parsing. Future studies could investigate changes to the decoder path, new optimization techniques with increasing training time to increase segmentation accuracy and efficiency in the context of autonomous vehicle.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to professor Jing Huang who accepted and supervised this research, thus successfully completing it. Thanks to Kaggle for allowing us to use their available free limited GPU’s and memory for computation and storage. Thanks to quill bot for helping us with the paraphrasing of a few citations. The codes are available upon request on the following emails: ebua.sowe@whut.edu.cn and huangjing@whut.edu.cn

References

- Wang, F.; Jiang, M.; Qian, C.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Residual attention network for image classification. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 6450–6458.

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X. Zoom out-and-in network with map attention decision for region proposal and object detection. International Journal of Computer Vision 2019, 127, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiong, P.; An, J.; Wang, L. Pyramid attention network for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference.

- Roth, H.R.; Lu, L.; Farag, A.; Shin, H.C.; Liu, J.; Turkbey, E.B.; Summers, R.M. DeepOrgan: Multi-level deep convolutional networks for automated pancreas segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 556–564.

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 3431–3440.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 770–778.

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Tanzi, L.; Vezzetti, E.; Moreno, R.; Moos, S. X-ray bone fracture classification using deep learning: A baseline for designing a reliable approach. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribaudo, M.; Moos, S.; Piazzolla, P.; Porpiglia, F.; Vezzetti, E.; Violante, M.G. Enhancing spatial navigation in robot-assisted surgery: An application. In International Conference on Design, Simulation, Manufacturing: The Innovation Exchange; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Le Ba Khanh, T.; Dao, D.P.; Ho, N.H.; Yang, H.J. Enhancing U-Net with spatial-channel attention gate for abnormal tissue segmentation in medical imaging. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Havaei, M.; Davy, A.; Warde-Farley, D.; Biard, A.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y.; Pal, C.; Jodoin, P.M.; Larochelle, H. Brain tumor segmentation with deep neural networks. Medical Image Analysis 2017, 35, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Jia, F.; Hu, Q. Automatic segmentation of liver tumor in CT images with deep convolutional neural networks. Journal of Computer Communication 2015, 3, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Roth, H.R.; Gao, M.; Lu, L.; Xu, Z.; Nogues, I.; Yao, J.; Mollura, D.; Summers, R.M. Deep convolutional neural networks for computer-aided detection: CNN architectures, dataset characteristics and transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2016, 35, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, D.; Syed, M.F.; Hasija, K.; others. A review on autonomous vehicles: Progress, methods and challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, E.; Alvarez, J.M.; Bergasa, L.M.; Arroyo, R. ErfNet: Efficient residual factorized ConvNet for real-time semantic segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2017, 19, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, N.; Paheding, S.; Elkin, C.P.; others. U-Net and its variants for medical image segmentation: A review of theory and applications. IEEE Access 2024, 9, 82031–82057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M.; Caspi, A.; Shapiro, L.; Hajishirzi, H. ESPNet: Efficient spatial pyramid of dilated convolutions for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 552–568.

- Pedersoli, M.; Lucas, T.; Schmid, C.; Verbeek, J. Areas of attention for image captioning. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1251–1259.

- Yang, Z.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L.; Smola, A. Stacked attention networks for image question answering. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 21–29.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 7132–7141.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 3–19.

- Saadati, D.; Nejati Manzari, O.; Mirzakuchaki, S. Dilated-UNet: A fast and accurate medical image segmentation approach using a dilated transformer and U-Net architecture. School of Electrical Engineering, Iran University of Science and Technology 2023.

- Fantauzzo, L.; others. FedDrive: Generalizing federated learning to semantic segmentation in autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2022, pp. 11504–11511. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 2881–2890.

- Arulananth, T.S.; Kuppusamy, P.G.; Ayyasamy, R.K.; Alhashmi, S.M.; Mahalakshmi, M.; Vasanth, K.; Chinnasamy, P. Semantic segmentation of urban environments: Leveraging U-Net deep learning model for cityscape image analysis. PLOS ONE 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).