Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. To Lay Down One’s Life

2.0. Robots, Electric Sheep, and Dignity: The R2-D2 and Wall-E Syndrome

3.0. Sacrifice and its Discontents

4.0. Descender and Ascender

5.0. Sacrifice in Descender and Ascender

- Amaya Travers, Andy’s mother, sacrifices herself so her son escapes after the mining incident in Dirushu. She then chooses to go back into the mine to try to save the colony, too, but ultimately perishes along with everyone else.45

- UGC officer Tullis sacrifices himself46 on the planet Sampsun (D18) when an enormous WORM creature attacks him along with Effie, Andy, Bandit, and Driller. He fights the WORM so they can retreat to a ship and escape. Before doing so, he tells Andy; “Promise me you’ll get Telsa47 out of trouble. No matter what else you do, promise me that” (D18). A startled Andy stammers: “I-I promise,” and in a side profile in the next panel, Tullis says: “And tell her—tell her I always loved her…just like she was my own daughter.” (D18).

- Helda Donnis, Private Second Class, UGC is the devoted companion to Telsa in Ascender who will go wherever she goes: “Once my Captain always my Captain,” as he often tells her. When Telsa agrees to risk her life and bring Andy and Effie’s daughter Mila to a safe haven in space (when ships had become forbidden by death per Mother’s orders), they venture to some island to reach Telsa’s hidden ship only to see it had become occupied by a spirit/magical demon.48 Helda lures the spirit out of the ship, willing to sacrifice himself so Telsa can get Mila away and fly the ship. Fortunately, Helda is saved by the wizard, Pelliot P. Mizerd (see next example below).

- Pelliot P. Mizerd, like Obi Wan Kenobi on Tatooine in Star Wars, was an elderly wizard who chose the life of a loner, in his case on the planet Woch, where there was much magic (D20). Despite his struggles, he not only helps a depressed, almost suicidal Driller but teaches and hones Mila’s magical powers (A15) and later sacrifices himself when trying to protect Mila, Bandit, Telsa, and Helda from the Gnishians.

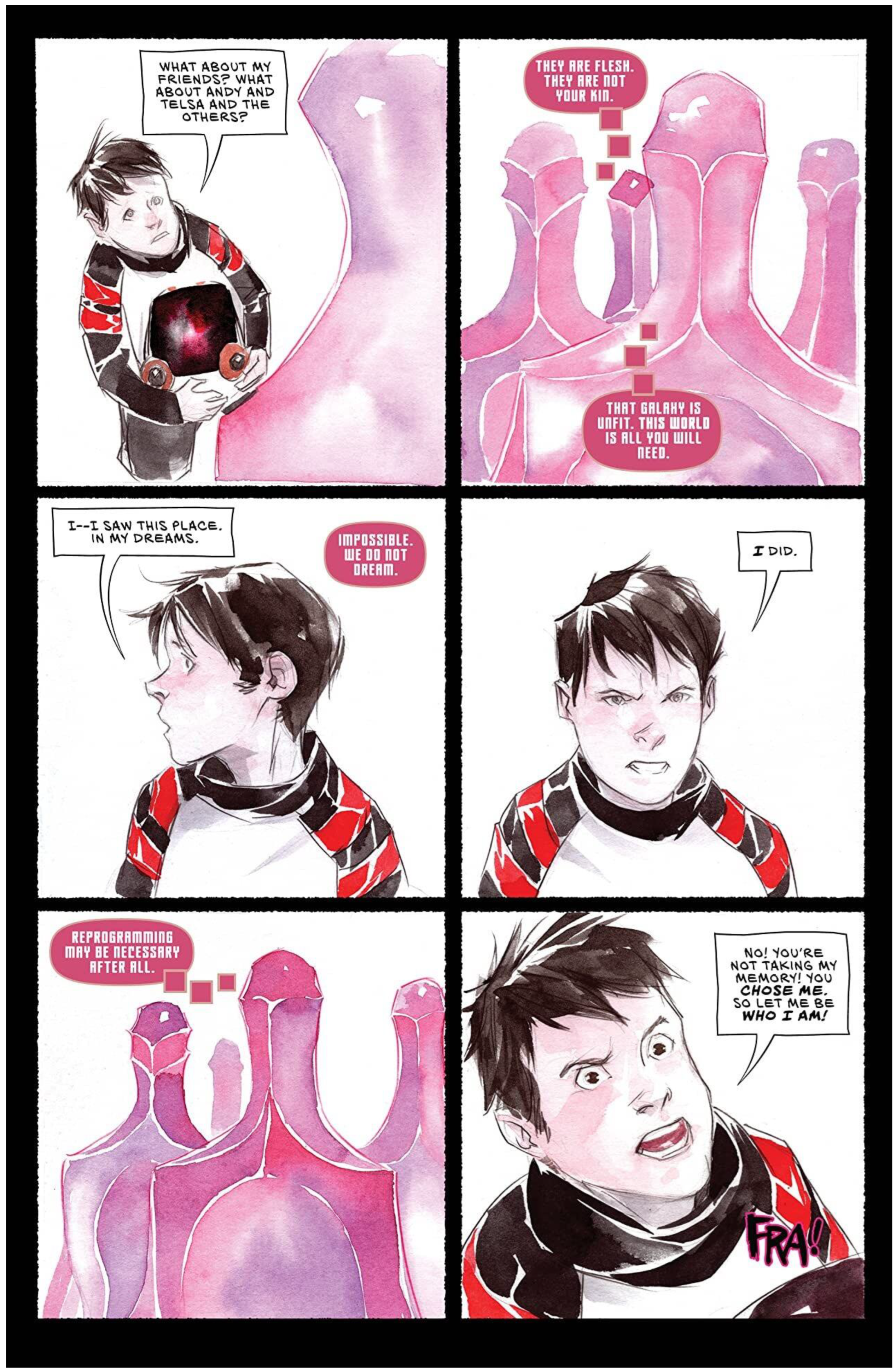

- Kanto the Blood Scrapper did not know he was a robot grafted with false memories as a father whose wife and kids were killed by vampires. He had believed he was “a servant of the only true God” (A8) and for whom “Vengeance is my holy mission” (A13). When he discovers his past was a lie (A16), he wants his engineer-creator to euthanize him (A17), but later chooses to save the robot TIM-21’s life by allowing TIM’s memories and identity to override his own false memories and inhabit his exterior body.49

5.1. TIM-21’s Empathic, Sacrificial Love

5.2. Effie’s Unconditional, Sacrificial Love

5.3. Driller’s Redemptive Sacrifice of Love

6.0. Conclusion: TIM-21, Effie, Driller, and Jesus:

- Freely chosen but still an aberration because all life is sacred.

- Deemed to be the only, best or last-resort way to save the life of another, who is suffused and ingrained within the love of oneself.

- Because the other is also an extension and distinction of one’s self, the person laying down their life chooses, in love, to sacrifice what is best in them for another because the world we live in, with its many injustices and failures, present such a choiceless choice.

- 1

- The robust academic field of comics studies needs little justification today, but for some recent comics studies examining religious, theological, or ethical themes, see, for example, Blair Davis, Christianity and Comics: Stories We Tell about Heaven and Hell (Rutgers: Rutgers University Press, 2024); Matt Reingold and Ramiro Bujeiro, Jewish Comics and Graphic Narratives: A Critical Guide (London Bloomsbury, 2022); A. David Lewis and Martin Lund, editors, Muslim Superheroes: Comics, Islam, and Representation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), and the books in the Series “Theology, Religion, and Pop Culture” from Lexington Books/Bloomsbury. See also my Destruction, Ethics, and Intergalactic Love: Exploring Y: The Last Man and Saga (Routledge, 2023).

- 2

- For a Buddhist examination of ethical issues around robots and AI, see Soraj Hongladarom, The Ethics of AI and Robotics: A Buddhist Viewpoint (Lexington Books, 2021); for a philosophical exploration of questions like: “Does a robot have moral agency?”, see Mark Coeckelbergh, Robot Ethics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2022); and for a scientific and ethical examination of machine ethics, see Rebecca Raper, Raising Robots to be Good: A Practical Foray into the Art and Science of Machine Ethics (Springer, 2024).

- 3

- As pointed out in the Jewish Annotated New Testament, this phrase (John 15:13) echoes (along with much of the passage on love and friendship), Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 9.1169a. The former is a foundational source for my reflections here, but any systematic evaluation of the context and history of the biblical passage is beyond the scope of this work, especially as ultimately, and as I have argued elsewhere, I prefer the Jesus of Mark’s gospel who is more unsure and struggling with what his calling and purpose mean than the confident Jesus in John’s Gospel who knows his purpose and seems to have everything foretold and planned. Especially for the many who have suffered traumatic and horrible suffering, a Christ as a fellow sufferer of anxiety, despair and suffering can resonate more, especially if that same Jesus believes in, and is the source according to Christians, for redemption and healing. See my -------. Note also that in John’s gospel, Jesus says these words about dying for a friend during his extended farewell discourse on Passover, what Christians have since called the Last Supper, a section in John’s Gospel which is replete with a series of wide-ranging metaphors and theological themes, from images of the vine and the branches to foretelling of the Holy Spirit. On love in John’s Gospel, see Francis J. Maloney, Love in the Gospel of John: An Exegetical, Theological, and Literary Study (Baker Academic, 2021); and Fernando F. Segovia, “The Theology and Provenance of John 15:1-17.” Journal of Biblical Literature 101.1 (March 1982): 115-128, http://www.jstor.com/stable/3260444. See also: Jan van der Watt, “Laying Down Your Life for Your Friends: Some Reflections on the Historicity of John 15:13.” Journal of Early Christian History, 4.2 (2014): 167–180, https://doi.org/10.1080/2222582X.2014.11877310; and The Jewish Annotated New Testament, ed. Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 187.

- 4

- For an interesting feminist and comics studies analysis of God’s creation in Genesis, see Liana Finck, Let There Be Light: The Real Story of Her Creation (New York: Random House, 2022).

- 5

- Such traumatic events include the murder of Victor’s brother William and the trial and execution of Justine Moritz (mistakenly blamed for William’s murder (committed by the Creature).

- 6

- Mary Shelly, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes and Nobles, 1993), 102. The Creature’s main request will be a companion like him which Victor will not bring to fruition.

- 7

- Shelly, Frankenstein, 125.

- 8

- For commentary, see The Norton Critical Edition of Frankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and edited by J. Paul Hunter (Norton: 2022).

- 9

- This is also a claim in traditional anti-theodicies that allege God’s moral failings in light of the problem of evil. See, for example, my--. 1 and 3.

- 10

- Confer: “I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend” (Shelly, Frankenstein, 101).

- 11

- Confer especially Richard’s wooing and bedding of Queene Anne after she scolds and imprecates him for his murdering her husband (and others). Shakespeare, Richard III, Act 1, scene 2.

- 12

- In the novella, Replicants were originally called “Androids” and Blade Runners were “bounty hunters.” These later terms were adopted for the 1982 movie.

- 13

- In the novella, androids with a “Nexus-Six brain unit” are the most advanced (Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (New York: Ballantine, 1996), 54.

- 14

- While I rebuked Frankenstein for a lack of empathy above, note that in Dick’s novella, the android/replicant Rachael is created with excessive empathy to use that against her would-be killers, the bounty-hunters/blade runners. Empathy is also a key characteristic of TIM-21 in Descender/Ascender as noted below. While compassion is the virtue par excellence for the Dalai Lama, empathy has come under some attack, most notably by Paul Bloom in Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (London: The Bodley Head, 2017).

- 15

- Roy then proceeds to reflect on the unique and potent memories which soon “will be lost like tears in rain.” He then saves Deckard and soon dies. For an article that employs religious and spiritual terms to analyze the film, see David Macarthur, “A Vision of Blindness: Blade Runner and Moral Redemption.” Film-Philosophy Volume 21.3, (Sept 2017): 371-391, https://doi.org/10.3366/film.2017.0056.

- 16

- In Blade Runner 2049, we learn that Rachael and Deckart were able to have a daughter but Rachael died in childbirth. In the novella, Deckard is married but is seduced by Rachael who tells Deckard: “Androids can’t bear children,” and refers to herself as “Chitinous reflex-machines who aren’t alive” (194), though her reflecting on the implications hint at something greater to her identity. Such is never resolved as the question remains of how and whether she shows humanity, whether through empathy, in her role seducing bounty hunters like Deckart or her cynicism and cruelty, especially in killing Deckart’s goat (226-227). Deckart admits to falling for Rachael and even sleeps with her, but the novella’s ending is very different than the film’s.

- 17

- See, for example, Joseph J. Darowski, X-Men and the Mutant Metaphor Race and Gender in the Comic Books (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014).

- 18

- The history is actually more complicated, especially as teased in the series’ final episodes and notion of its cyclical history. On its links to American culture and the war on terrorism, see Tiffany Potter and C. W. Marshall, eds., Cylons in America: Critical Studies in Battlestar Galactica (New York: Continuum, 2008).

- 19

- This is most evident in the relationship of Cylon Sharon Valeri and BSG Viper Pilot Karl C. Agathon (callsign “Helo”) and a bit more complicated in Caprica 6 and Gaius Baltar. For a series of essays examining the various meanings of interspecies sexual relationships in sci-fi, see The Sex Is Out of This World: Essays on the Carnal Side of Science Fiction, ed. Sherry Ginn and Michael G. Cornelius (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012).

- 20

- See, for example, Obama's Guantánamo: Stories from an Enduring Prison, ed. Jonathan Hafetz, Jonathan (New York: New York University Press, 2016); Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Guantánamo Diaries, ed. Larry Siems (Edinburgh: Cannongate, 2015); and Steve Coll, Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2001–2016 (London: Penguin, 2019).

- 21

- For theological and ethical analysis of Battlestar Galactica, see Erica Mongé-Greer, So Say We All: Religion, Spirituality, and the Divine in Battlestar Galactica (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2022). Other powerful examples (not discussed above) of robots seeking rights or legal recognition include the video game Detroit: Become Human, where you play as androids who make moral decisions and who seek true freedom, and the Mass Effect games, especially the story arc of EDI in the third game. See also many of the Becky Chambers novels including her A Monk and Robot series; for commentary on her Wayfarers series, see my------. A modern classic on stories of robots seeking redemption and meaning in life is C. Robert Cargill, Sea of Rust (New York: HarperVoyager, 2017). Questions of robots and souls are frequent ones. As Deckard asks fellow bounty hunter Phil Resch in the novella: “Do you think androids have souls?” (Dick, Do Androids Dream, 135).

- 22

- Proponents of universal salvation, for example, would contend that none of us would rationally choose acts that might condemn us to eternal damnation and so cannot be deemed free and responsible for such choices. For my analysis in the context of theodicy, see Amidst Mass Atrocity, chapter 11. Determinists like neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky contend we have no free will because of various factors like environment, hormones, and genes, and so are not responsible for what we do. We are the ones who are robots. See Robert Sapolsky, Determined: The Science of Life Without Free Will (London: Penguin, 2023). I would contend that we are all constrained to various degrees in terms of how fully free we are and how rationally clear we are in terms of intentions, justifications, and the intended and likely consequences of our actions. Nevertheless, most of us are responsible for the actions (and inactions) we do.

- 23

- Thich Nhat Hanh, Interbeing: Fourteen Guidelines for Engaged Buddhism (Berkeley, CA: Parallax, 1987).

- 24

- See for example, our bloodlust to wipe out wolves but recent efforts to protect them in Nate Blakeslee, The Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West (London: OneWorld, 2018). In Rockstar Game’s Red Dead Redemption, occurring in the declining Wild West of America circa 1911, you can see NPCs callously killing buffalo for sport and can even choose to take part in such culling, even to kill the last buffalo and get a virtual trophy called “Manifest Destiny.” Note the game’s creators provide moral condemnation of such acts through various indigenous voices, including the Native American Nastas who tells the lead character John Marston (when they both are out riding and white men callously shoot buffalo for sport: “We hunt to eat, not for sport. Soon there will be no buffalo left.”

- 25

- See Eyal Press, Dirty Work: Essential Jobs and the Hidden Toll of Inequality in America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

- 26

- For a recent take on the trolley dilemma (though not involving Star Wars), see David Edmonds, Would You Kill the Fat Man?: the Trolley Problem and What Your Answer Tells Us about Right and Wrong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

- 27

- Wall-E could presumably fly out of the water!

- 28

- See my---.

- 29

- Aeschylus, Agamemnon in The Greek Tragedies. Volume 1, eds. David Grene and Richard Lattimore, and trans. Richard Lattimore (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1960, (208, p. 11).

- 30

- Ibid., 218, p. 11.

- 31

- Ibid., 228, p.11. On scapegoating, see René Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (Maryknoll, Orbis, 2008). “The defense of victims is both a moral imperative and the source of our increasing power to demystify scapegoating” (3).

- 32

- Keats’ 1819 ode has the line; “Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,” a beauty seemingly more potent than in real life because it can never fade and she will always be true, similar as well to the twisted logic of the narrator in Robert Browning’s “Porphyria’s Lover” (1836).

- 33

- Jephthah’s unnamed daughter was later referred to as Seila or Iphis from medieval sources. Note also that some Jewish scholars have argued that she wasn’t killed but was offered to the Lord in a way that had to preserve her virginity. See Rachel Adelman, “Crossing the Threshold of Home: Jephthah’s Daughter from the Hebrew Bible to Modern Midrash.” In Feminist Interpretations of Biblical Literature, ed. Lilly Nortjé-Meyer (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022), 1-26. For a famous example critiquing Jephthah, see Peter Abelard’s second letter to Heloise, in which he writes: “Such men (the lords of the earth) could properly be compared with Jephthah, who made a foolish vow and in carrying it out even more foolishly, killed his only daughter” (“Letter 2, Abelard to Heloise,” in The Letters of Abelard and Heloise, trans. Betty Radice (Penguin: London, 1974), 121.

- 34

- In Fear and Trembling, Søren Kierkegaard examines the Akedah narrative from different angles and perspectives, but still sees Abraham’s blind obedience and faith as ultimately praiseworthy (especially as he never had to go through the killing of his son), but I maintain any teleological suspension of the ethical is theologically self-destructive and opens the door to deicide if not a Deism that leads to God’s meaninglessness in this world.

- 35

- Sophocles, “Antigone” in Sophocles I, trans. David Grene, 2nd ed. (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991), 570 (p. 181).

- 36

- Ibid., 504 (p. 178).

- 37

- Ibid., 576 (p. 181).

- 38

- See Peter Hayes and John K. Roth, editors, The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); and Dan Stone, The Holocaust: An Unfinished History (London: Pelican, 2024).

- 39

- Didier Pollefeyt, “Christology After Auschwitz: A Catholic Perspective.” In Jesus Then & Now: Images of Jesus in History and Christology, ed. Marvin Meyer and Charles Hughes, 229–248. Harrisburg: Trinity, 2001); and my “The Future of Post-Shoah Christology: Three Challenges and Three Hopes.” Religions 12.6: 407 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060407.

- 40

- See, for example, Richard Rohr, “The Franciscan Option,” in Stricken by God? Nonviolent Identification and the Victory of Christ, ed. Brad Jersak and Michael Hardin, 206–212 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

- 41

- See, for example, Jon Sobrino, No Salvation Outside the Poor: Prophetic-Utopian Essays (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2008).

- 42

- While optioned for television in 2020, the comics have been reissued in various prestigious hardback books, and most recently saw the successful crowdfunded The Art of Descender book in 2024.

- 43

- The comics will be cited in the text by issue as they are non-paginated and with the “D” for Descender and “A” for Ascender.

- 44

- A name like Mother and Mother’s use of love is ironic and totalitarian throughout the series, in contrast to selfless, heroic motherhood represented by Effie (who also happens to become a cyborg!) or Andy’s mom.

- 45

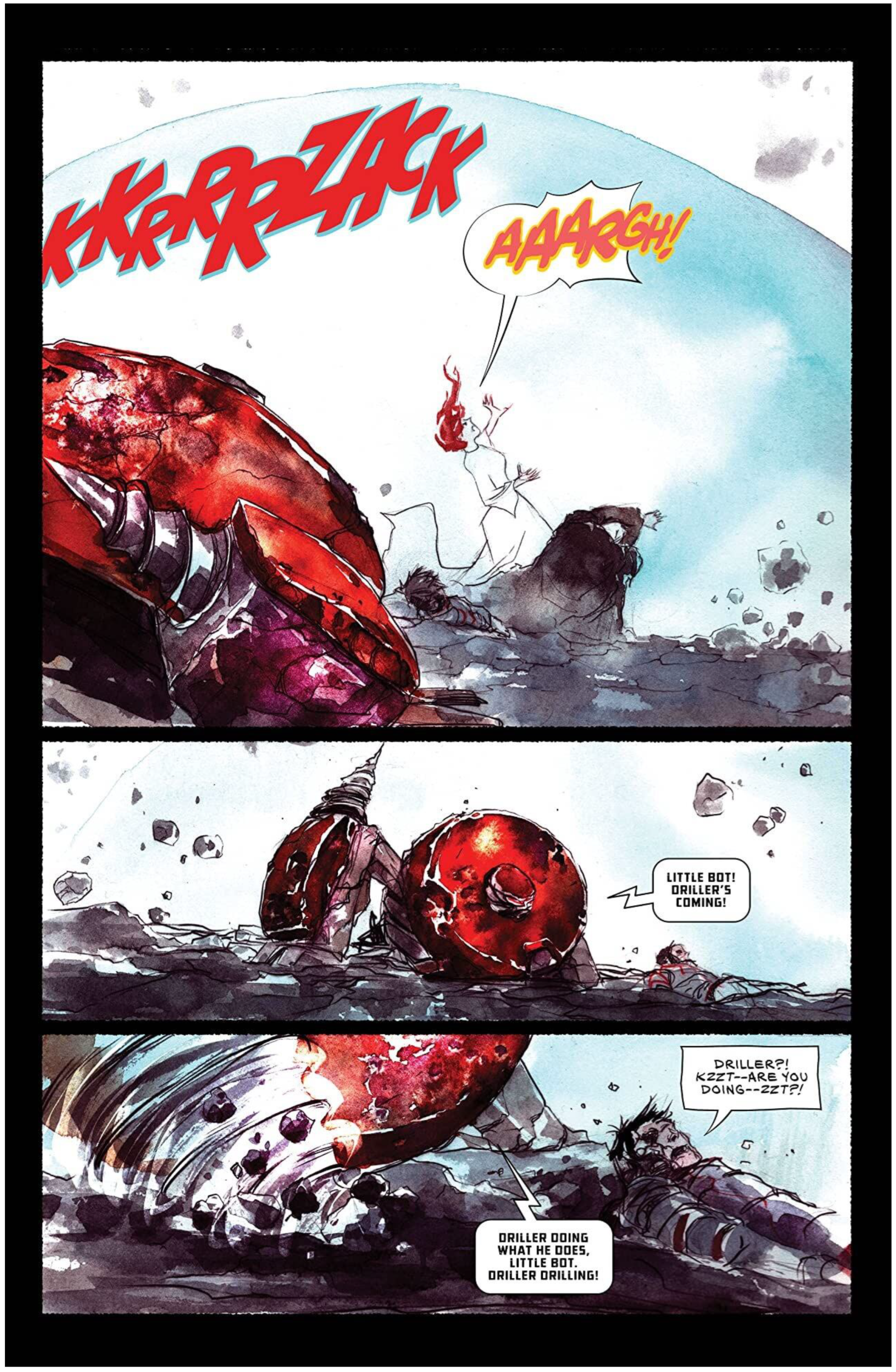

- See the sections on Driller further below.

- 46

- In comics (like the movies), if you don’t see a dead body confirmed, possibilities of life remain. And while some comics, like Saga, Y: The Last Man, and Monstress have permanent deaths, others veer around a character’s death by a reboot of the series—a retcon—or some alternative universe plot. In Descender/Ascender, if a character dies, they are dead unless, like Effie they are a Cyborg who happened to be bitten by a vampire and so is deemed dead by her husband and buried only to have her cyborg parts defeat the vampire virus and restore her heart! (A12).

- 47

- Telsa is another main character in the book who is the daughter of the General of the UGC and always feels she has to live up to his cold and stern love. She was also traumatized and embittered by the murder of her mother by the Harvesters (sent by the Descenders) as they both tried to flee. Her survivor guilt manifests itself in a gruffness and fear of getting close to anyone, though TIM-21’s trust of her and loyal soldiers under her command challenge much of her desire to close people off. Telsa is a symbol of the soldier always willing to sacrifice herself for a cause but her intentions, because of her scarred past, would need deeper analysis than is possible here. She would also not seem best to embody the kind of sacrificial love I am advocating. Is hers a reluctant sacrificial love, not a full-bodied choice but one that only emerges after a lot of inner-refusal and rebellion? Does that make it less noble? I am reminded here of Jesus’ parable about the son who is asked by his father to work in the vineyard and says he won’t do it but then does as opposed to the one who says he will and doesn’t (Matt 21:28-32). In the end, the first son is obviously better but perhaps the ideal would be the one who says and does the good. Jesus was making a point about sinners who repent and ultimately do what is good.

- 48

- It is later called a “hungry ghost” by Mizerd (A10).

- 49

- This is another problematic example of sacrifice as Kanto still had value in what he became and chose to do even if the initial memories and backstory were fabricated. Plotwise, it’s a clever way to allow TIM-21 to then inhabit an adult human body that (for a time) matches Andy’s so they can appear closer on the outside just as they had when Andy was little in the mines of Dirushu. Of course, Andy will continue to age visibly while TIM won’t in the same way.

- 50

- Dr Jin Quon’s character story is very complex involving a lot of betrayal and self-centredness (much like Gaius Baltar in Battlestar Galactica) with a deep intelligence and canniness and moments of heroism, but space does not permit his story here.

- 51

- While TIM-21 becomes special and unique, initially he was just one in a series of these model robots like the Replicants or Cylons who had various identical models. TIM-22 looks just like TIM-21 but becomes a bitter, vengeful robot (partly because he was abused and hunted by humans).

- 52

- Note it’s not clear how the Descenders keep their promise because Effie and Andy would have died if Effie hadn’t had some “personal force field” (convenient) as they were left floating in space when the Descenders disappeared, and then saved by Driller when her “personal force field” had no more power to sustain them.

- 53

- Effie is a Christ-figure in many ways with her unconditional, sacrificial, kenotic, motherly love, her death and resurrection, two natures, etc., though like most Christ-figures, the match is one of resemblance but never a perfect fit.

- 54

- This is a very flawed moment especially as Andy has been a devoted father to Mila who would also sacrifice his life for her (but obviously fails in this crucial moment!).

- 55

- This is how Driller calls humans which sounds like harmans – those who harm.

- 56

- That the phrase hovers over Andy is also fitting as Effie left him precisely because she felt he was a murderer in killing robots and even called him that. Thus, at this point in the comic, both Andy and Driller are in need of repentance and change.

- 57

- Note that she also let anger at Driller’s boss (Trask) blind her to the care needed of the robots who she deemed disposable (D16).

- 58

- The Coven is led by one demonic/witch-like figure deemed Mother even if the one in power might be a daughter or sister to others in the group and through which they perpetually fight and backstab one another in their quest for controlling all the magical power in the galaxy. While TIM-21 and Driller are fighting Mother, readers of the comic would know that two sisters had fought one another for power and to take on that title of Mother. Initially the one called “weak thing” was able to overcome her tyrannical sister—and is the Mother who is responsible for the vampiric horde and other monstrosities that were unleashed on the world after the Descenders removed all robots from the galaxy (and culled billions of lives). But this Mother (weak thing) unexpectedly loses her power to her sister and TIM-21 is fighting that incantation while hoping the Harvester Robot will destroy them all. Instead, “weak thing” is able to regain her power and kill her sister as the Harvester attacks. She survives the beam, only to finally be defeated by Effie, a true mother. Driller is at least able to protect TIM from the Harvester’s beam and give him a chance to live, though sacrificing himself in the process.

- 59

- When Driller first meets young Mila, as they are attacked by vampire birds, Driller says he’s not scared and that “Driller’s a real vamp killer,” and there is a delightful wide-eyed and smiling image of Mila, admiring him: “I like you” she says, touching his robot ‘clamped hand’. While his reply is “hmmm” which is what he always says –how can even he not fall for Mila with that look of admiration and perhaps the sweetest words said to him: “I like you, Driller” (A11). Soon Driller is playing hide and seek in a ship with Mila and Bandit (A13), though he doesn’t like the game because he’s too easily found being so big.

- 60

- Moshe Halbertal, On Sacrifice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 1-2.

- 61

- Daniel A. Madigan, S.J. “Who Needs it? Atonement in Muslim-Christian Theological Engagement” in Atonement and Comparative Theology: The Cross in Dialogue with Other Religions, ed. Catherine Cornille (New York: Fordham University Press, 2021), 27-28 (11-39).

- 62

- This passage also is used to support the Ransom Theory of Atonement.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).