1. Introduction and Hypothesis

With the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the vectors of development of Russia and the former Union republics were formed in different ways. In Russia, the movement towards expanding civil liberties and contacts with the outside world, undertaken in the 1990s, has been gradually curtailed since the early 2000s, and after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and especially with the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, it sharply intensified (Erpyleva and Luhtakallio, 2024; Skulsky, 2024; Torikai, 2023).

The Republic of Uzbekistan joined the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe shortly after the collapse of the USSR in 1992, but for a long time remained largely a closed country in terms of cooperation with the outside world, as well as in terms of the development of rights and freedoms in domestic politics, including relations between the state and the mass media.

However, with the coming to power of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in 2016, much has changed in Uzbekistan in the relationship between the state and society within the country and towards the expansion of international cooperation. Thus, in 2020, Uzbekistan was elected to the UN Human Rights Council for the first time for a three-year term (2021-2023). Within the country, the executive and legislative authorities also took several measures aimed at expanding the rights and freedoms of citizens, including journalists. In 2019 President of Uzbekistan Shavkat Mirziyoyev signed a decree ‘On additional measures to ensure the supremacy of the Constitution and the law, strengthen public control in this area, as well as improve legal culture in society’ (On additional, 2019), which, among other things, instructed to ‘strengthen the system of protecting journalists from illegal actions or decisions of state bodies and officials’ (On additional, 2019);

In 2023, the president signed a decree ‘On approval of the national program of education in the field of human rights in the Republic of Uzbekistan’ (On approval, 2023), and many other acts of the executive and legislative branches.

In public speeches, the head of state also spoke out in defense of journalists and the media. During a conversation with the press on a working trip to the Ferghana region in 2021, Shavkat Mirziyoyev said, addressing journalists: ‘You are my comrades, I count on your help. I see you as a power that fairly talks about our achievements and shortcomings to our people… I want to ask you one thing: don't be lazy to be on the lookout. Don't be afraid to deliver [information] fairly. The president stands behind you’ (Shavkat, 2021). In 2023 During his trip to Kashkadarya region, the president also unequivocally spoke in favor of media freedom: ‘We did not hear the fair voice of people because we were a closed country and did not support the media. We didn't hear. Do you like the breath of freedom? I like it. Yes, it's harder for me to work like this. But they tell me, "Close it." However, I won’t do it’ (Many, 2023).

The result of the liberal discourse of the authorities was the positive dynamics of indicators in the field of observance of civil rights, freedom of journalists and media in Uzbekistan and in some other countries of the region, recorded by international non-governmental organizations.

However, 2023 overshadowed these dynamics - when the international non-governmental organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) moved Uzbekistan in its ranking from 133rd place in 2022 to 137th place in 2023. In some other Central Asian countries, the dynamics of freedom of speech deteriorated even more degrees: in Kazakhstan, this indicator moved from 122 in 2022 to 134 in 2023, and in Kyrgyzstan - from 72 in 2022 to 122 in 2023 (Press, 2023).

In the following year, 2024, the position of the countries considered here in the RSF classifier has changed again: towards a slight improvement, by 2 positions, in Kyrgyzstan and a significant deterioration, by 8 and 11 positions, in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, respectively.

In December 2022, the delegation of the European Union to Uzbekistan, together with the Embassy of the United States of America and the Public Foundation for the Support and Development of National Mass Media, held a round table in Tashkent ‘On the state of freedom of speech in the Central Asian region’ with the participation of media lawyers from Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan (Human, 2022). Here, the contradictions between the publicly expressed wishes of high-level politicians, such as President of Uzbekistan Shavkat Mirziyoyev, and the real state of affairs in the field of freedom of the mass media have manifested themselves. Karim Bahriev, a popular journalist in Uzbekistan since the time of Islam Karimov, said during a round table meeting: ‘The new leadership of Uzbekistan says that there is freedom of speech, and there will be no rollback in this area. In every speech, the President of Uzbekistan says that he is on the side of journalists and bloggers. Always he tells hakim <the heads of the country's regions to learn how to work with journalists. The president has such a will. But does the government have it? If we evaluate the attitude of officials and hakims, we will not see such political will in many of them’ (Karim, 2022).

What is going on with freedom of the media and freedom of speech in a broad sense in Uzbekistan and Central Asia? We hypothesize that there is an informal, implicit opposition on the part of middle-level officials to the official discourse of the supreme executive power.

In turn, such obstacles, taking the form of political censorship, are provoked by the dominant role of the state in the ownership of the leading mass media in each of the countries considered here.

Despite official declarations about the lack of political motivation in relations with the former metropolis represented by the Russian Federation, some Central Asian states continue to habitually copy the practice of censorship restrictions imposed by the current political regime in Russia on national mass media and representatives of the blogosphere, which is expressed, in particular, in duplication at national levels of the Russian law about ‘foreign agents’.

The above leads to the emergence of relapses of authoritarianism in the domestic politics of the countries of the Central Asian region as a whole and in the relations of the state with the mass media and representatives of the blogosphere in particular and, ultimately, to the formation of a persistently low level of media literacy of the population.

We will confirm these statements in the course of this study.

2. Methods

Firstly, the authors used a method of observation — both for specific events related to the activities of journalists and bloggers and the reaction of government agencies to these activities and for the reaction of the public to what is happening between the institutions of government, journalism and such an important institution of democracy as freedom of speech. In this aspect, the authors relied on an extensive block of information collected from the reports of professional media from the countries of the Central Asian region: these reports served, among other things, as sources for research. So, from the reports of Uzbek media, such as Gazeta information portals.uz and Newshub.uz, information was used on the reaction of the journalistic community to restrictions on freedom of speech, the activity of independent bloggers, and media activities in the Republic; from the messages of the Kazakh portal Informburo.kz became aware of dozens of cases of violations of journalists' rights, hundreds of events concerning violations of the right to receive and disseminate information, dozens of judicial and pre-trial claims against journalists and bloggers; from the messages of the Kyrgyz portal Yenisafak.com. This paper uses information on the reasons for the decline in Kyrgyzstan's rating in the Reporters Without Borders classifier for 2023 by 50 positions at once.

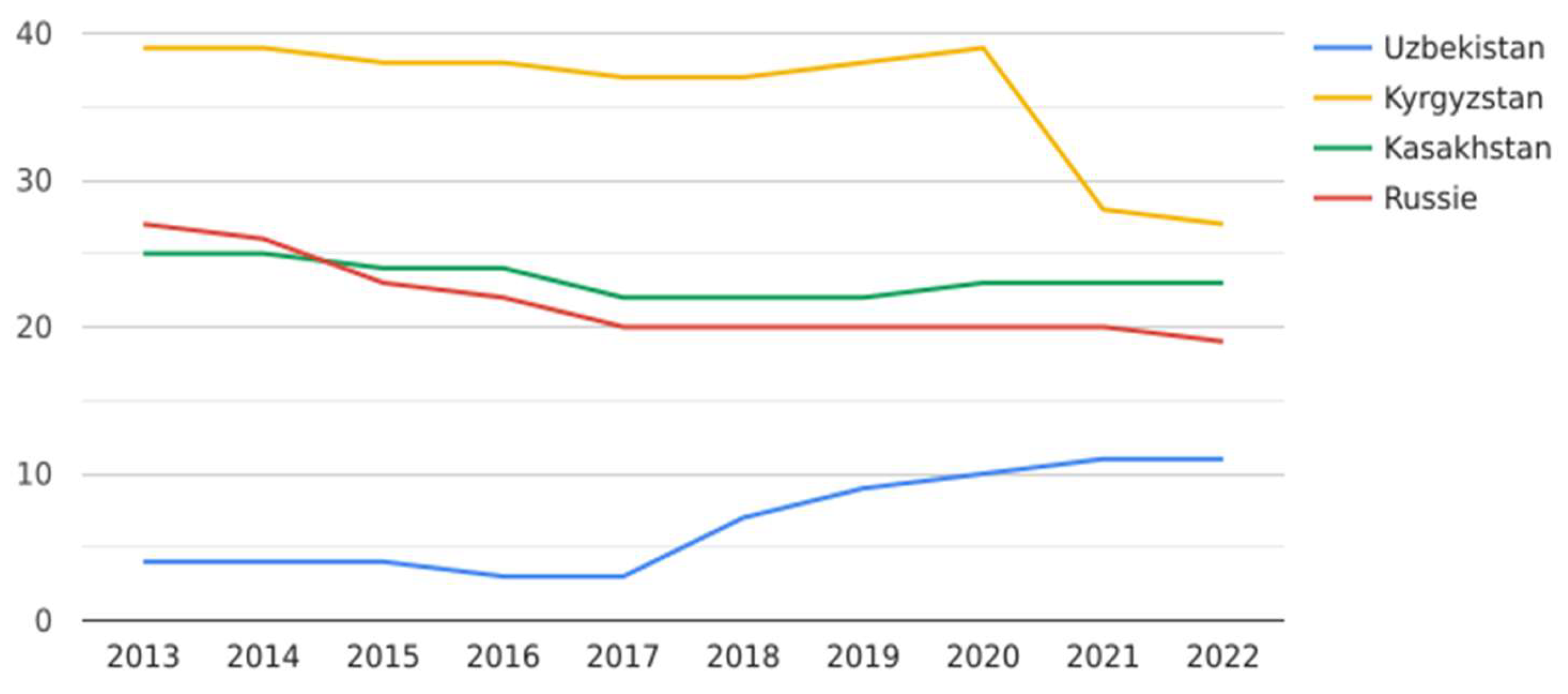

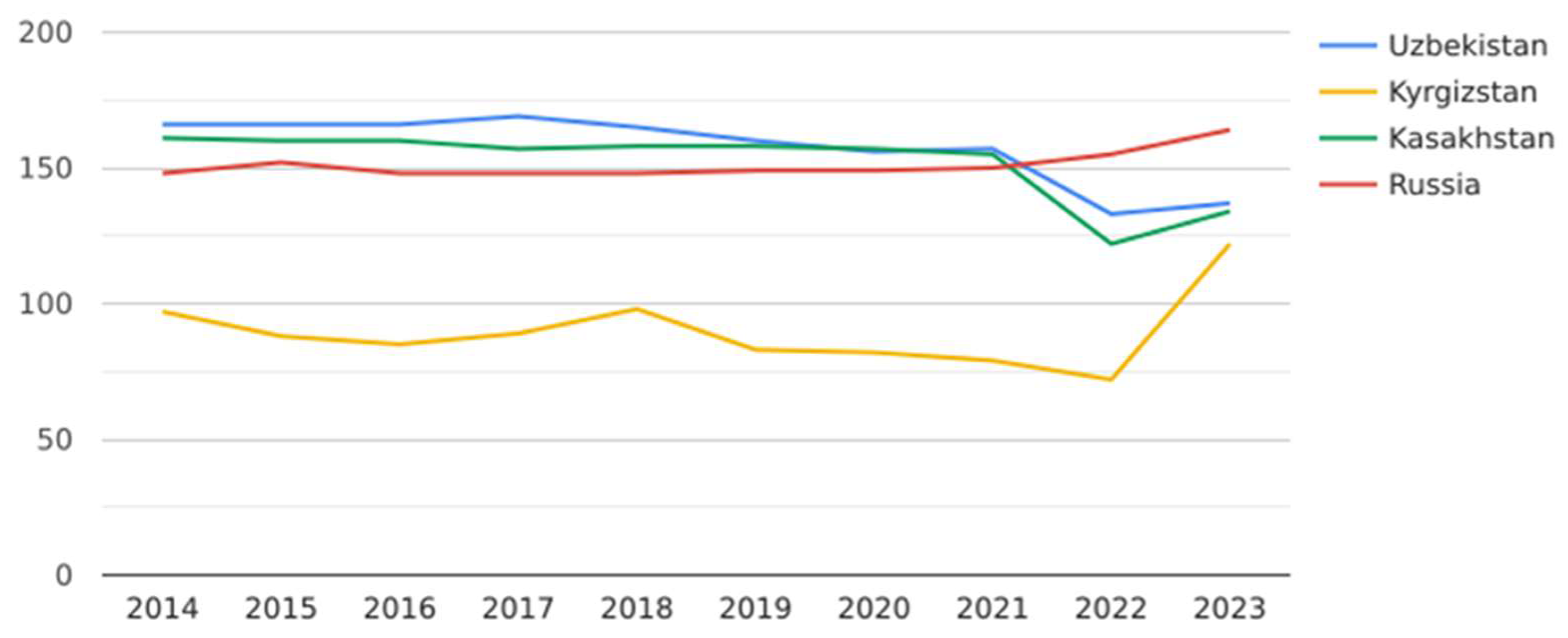

The method of comparative analysis of the dynamics of the development of global freedoms and freedom of activity of journalists and mass media in several countries of the Central Asian region revealed significant differences in the approaches of the authorities and the public of these countries to the problems under consideration. To implement this research method, the authors reflected on the dynamics of the development of global freedoms, according to the non-governmental organization Freedom House, for the ten years 2013-2022 and the dynamics of the development of freedom of speech, according to Reporters Without Borders, for 2014-2023. In tabular and graphical form for three Central Asian countries, such as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, as well as, Russia as a former metropolis, which in the recent past was oriented by the former republics of the USSR (this orientation has largely been preserved, as we will demonstrate later).

The questionnaire method, which the authors used to identify citizens' preferences in using certain sources of information, contributed to substantiating the thesis about the advantages of online media related to the private sector. 275 respondents of various ages and social categories took part in the survey. During the survey, we were interested in the respondents' thematic interests in the field of information consumption and their preferences in using sources.

3. Literature Review

The fact that the authoritarian government is primarily concerned with the production of censorship pressure on journalism and free media has been reported for a long period in many studies. In recent years, scientists have studied, the specifics of censorship pressure in the former Soviet republics. Thus using the example of Ukraine during the presidency of Yanukovych (2010-2014), the article examines what factors support the activities of journalists in the fight against censorship pressure in a competitive authoritarian regime (Somfalvy & Pleines, 2021); Another study highlights the importance of studying stability and changes in public opinion and state-society relations in authoritarian conditions using the example of Belarus before and after August 2020 (Onuch & Sasse, 2022).

Professional journalism also suffers under the influence of such factors, if only because, for example, the authors of the study ‘What is professional journalism? Conceptual integration and empirical refinement’, ‘professionalism is not a self-evident concept in the field of journalistic research’ (Gonzalez & Echeverría, 2022). Under the conditions of restrictions, journalism loses the role of a controller of power and society, which many researchers talk about the need to fulfill (Nielsen, 2016; Skovsgaard; Geiselberg & Andersen, 2024); at the same time, some justifiably use the harsher term ‘role of watchdog’ in the list of characteristics and tasks of professional journalism (Hendricks; Beckers & Van Droogenbrouck, 2024).

A separate block of publications served as sources for studying the processes of interaction between the state and society in a broad sense: M. Beaufort (2018) talks about political polarization and challenges to democracy; K.K. Chan talks about the mutual influence of the state and society, organizational culture and critical events; F.L.F. Lee & G. Tan (2024). To analyze the experience gained in different parts of the world in the field of relations between the state and the community of journalists and representatives of the blogosphere, the study also uses a separate block of sources: the work of R.A. Gonzalez & M. Echeverría (2022) is devoted to the analysis of the characteristics of professional journalism; in the works of F.M. Henriksen; J. Christensen & E. Mayerhöffer (2024), R.S. Klem; E.S. Herron & A. Tepnadze (2023), the results of the spread of pro-Russian political propaganda in the European news environment, including in the digital alternative environment; the dynamics of influence on A comparative study by T.A. Maniu (2022) is devoted to freedom of the press in various media systems; many researchers focus in their publications on the importance of fact-checking skills for the population (Lelo, 2022; Kumar, 2022; Tandoc & Seet, 2022).

However, these problems have been studied to the least extent in relation to the former republics of the USSR — the countries of the Central Asian region, in particular Uzbekistan. Therefore, a separate block of sources of this work consists of publications by national authors, exploring the processes between government and society, government and the media. Thus, the author of the study ‘The concepts of "fake" and "disinformation" in the media environment of Uzbekistan’ (Abdikarimov, 2023) points out the direct dependence of the success of the process of detecting fakes and disinformation on the level of media literacy of the population; the increase in the dissemination of both unreliable information and purposefully produced fake news related to the escalation of international conflicts, such as the one that began in 2022, the armed confrontation between Russia and Ukraine and the war between the Hamas group and Israel in 2023, the authors of the study ‘Media Research Management Methodologies as a Tool for Solving Problems of Information and Media Literacy of the Population: a Look at Uzbekistan’ (Allayarov & ot., 2023) draw attention to: low level of media literacy of the population, noted in the above-mentioned works, with simultaneous restriction of freedom of speech coming from the apparatus of state bodies, and provoke a decrease in the ratings of global freedoms and the classifier of freedom of speech and mass media, as we demonstrate in this paper.

In this paper, we also use to a limited extent the results of our own previously published research, such as ‘The Political Socialization of the People in Uzbekistan: Media Presence and the Absence of Media Literature’, which states that it is ‘mass media that play a crucial role in the process of communication between government and society in general and the process of political socialization of the population (Kudratkhoja, 2024).

Fundamental international documents in the field of human rights and in the aspect of obtaining and disseminating information, such as the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and, in particular, the provisions of Article 10 of the Convention on Freedom of Expression (The European, 2024), which, in turn, proceeds from the basic provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, the Rome Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of 1950 and other documents.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Freedom of the Press as Part of Global Civil Liberties

In this paper, we have turned simultaneously to data from two non-governmental organizations – Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, concerning the development of global freedoms and press freedom in the Central Asian states considered here over the past decade.

Thus, in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, the authorities, according to the annual rating of the non-governmental organization Freedom House (Freedom, 2023), have made tangible efforts over the past decade to expand the rights and freedoms of citizens (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

The table shows that Uzbekistan remained far from the ‘partially free’ regime for ten years 2013-2022, unlike Kyrgyzstan, which maintained a level of partial freedom from 2013 to 2021, inclusive; Kazakhstan balances at a level slightly above 20 points; Russia steadily reduces its rating of global freedoms.

The graph in

Figure 1 further demonstrates the separation of Uzbekistan's rating from other countries considered here in the dynamics of the level of global freedoms. However, the same schedule allows us to note that it is the coming to power of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in December 2016 that ensures the progressive movement of Uzbekistan towards the expansion of democratic institutions in the Republic, including the public institute of journalism as one of the components of democracy.

In 2023, there were no changes in Kazakhstan's position in the FH rating: the country scored 23 points out of 100 possible, as in 2022; Kyrgyzstan, as in 2022, retained its 27 points; Uzbekistan improved by one position — scored 12 points against 11 in 2022; Russia worsened its position in the FH global freedoms ranking by 6 points — from 19 in 2022 to 13 in 2023 (Freedom, 2024). At the same time, it is obvious that it was the beginning of Russia's military operations on the territory of Ukraine in February 2022, although perceived differently in Europe (Fagerholm, 2024), that simultaneously contributed to the deterioration of its rating of global freedoms and the process of divergence in domestic policy, which is broadcast to its citizens by the authorities in Russia, on the one hand, and in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand. This is also because the heads of state and government of the region see in the attitude of the official political leadership of the Russian Federation towards their countries a desire to revive the model of interaction between the command center in Moscow and subordinate regions that existed during the decades of the Soviet era. For example, at the CIS summit in October 2022, the President of Tajikistan publicly appealed to the President of the Russian Federation with a request that ‘there should be no policy towards the countries of Central Asia, as happened in the Soviet Union’ (Rakhmon, 2022). Within the framework of such an assessment of relations between Moscow and the republics of Central Asia, there was also a statement by Deputy Prime Minister - Minister of Energy of Uzbekistan Jurabek Mirzamakhmudov, made in December 2022 in response to a proposal from the Russian Federation to create a triple ‘gas union’ with the participation of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. ‘We will never agree to political terms in exchange for gas,’ — stated the official (Reuters, 2022; Uzbekistan, 2022). Such examples, according to the researchers, indicate, among other things, ‘disintegration processes resulting from the collapse of the Russian hegemonic order in the post-Soviet space’ (Zaporozhchenko, 2024; Pizzolo, 2023).

Nevertheless, despite official statements about the lack of political motivation in relations with Russia, some Central Asian states are adopting the experience of the former metropolis in terms of domestic politics and relations with the media and representatives of the blogosphere. At the same time, as in the case of global freedom, according to FH, mass media institutions in the countries under consideration are developing in different ways: mainly towards the development of freedom of professional activity of journalists in some Central Asian countries, and, conversely, towards restrictions in Russia and some other countries of the region. This position is confirmed by the following dynamics, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), over the ten years from 2014 to 2022. However, it is 2023. It worsened the position in the RSF rating of both Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, as we reported above, and as it becomes obvious from the RSF data is presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 2.

It should be considered that when comparing the dynamics of the general level of civil liberties, according to Freedom House (FH), with changes in the position of countries in the ranking of freedom of speech, according to RSF, a lower digital indicator corresponds to a lower level of development of democracy in a particular country, and a higher digital indicator In the case of RSF, on the contrary, it means a decrease in the level of freedom of speech and mass media.

In comparison with its closest neighbors, Kazakhstan, where the indicator of freedom of speech and mass media shifted from 122 places in 2022 to 134 in 2023, and Kyrgyzstan, where the indicator shifted from 72 in 2022 to 122 in 2023, the scale of deterioration in dynamics for Uzbekistan in 2023 may seem insignificant. However, there were serious prerequisites for the downgrade of the RSF rating in all three cases. Here again, it should be recalled that in liberal democracies, ‘freedom of the press is considered as part of a broader group of rights that fall under the umbrella of the right to freedom of speech and freedom of information’ (Maniu, 2022).

4.2. Driving Forces of Changes in RSF Ratings

For Kazakhstan, the reason for the negative dynamics of the RSF classifier was a noticeable increase in censorship restrictions at the level of both legislative and executive authorities. So, in September 2023, Parliament passed a law on fake news, and the Ministry of Finance, following the example of its Russian neighbor, launched the process of using the term ‘foreign agent’ against the media and journalists whose work is paid, in whole or in part, at the expense of foreign organizations. In addition, the immediate result of amendments to the media bill introduced by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in September 2022 was the denial of accreditation to 36 reporters of the Kazakh service of the American broadcasting company Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — Azattyk radio stations: the essence of the amendments introduced by the President is to allow officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to make decisions about the ‘threat to national security’ hypothetically emanating from foreign media (Kazakhstan, 2024).

A significant shift in the rating of freedom of speech according to the RSF classifier in Kyrgyzstan by 50 positions at once — from 72nd place in 2022 to 122nd place in 2023 due to some specific reasons. Despite a slight, only 2-point improvement in the rating in 2024, the reason for such noticeable losses in 2023, according to RSF, was the law on ‘foreign agents’ signed earlier and based entirely on Russian practice by President Sadyr Japarov, as well as actions by local authorities such as the closure of the Kyrgyz service of Radio Liberty (Radio, 2023). In 2024, the practice of restrictions imposed on the activities of journalists and mass media continued: at the beginning of the year, 11 media employees engaged in investigative journalism were arrested at once, the authorities attempted to eliminate the private investigation portal Kloop, expelled ‘undesirable’ journalists from the country (Kyrgyzstan, 2024).

Finally, Uzbekistan’s rating in the RSF classifier shifted in a negative direction from 133 place in 2022 to 137 place in 2023; after that in 2024, Uzbekistan worsened its indicator by another 11 positions and moved from 137th place in 2023 to 148th place in 2024. In this case, the driving force for the changes in the RSF rating was the aspirations of representatives of the state apparatus to exercise control over publications (broadcasts) of national mass media and in the information space of the blogosphere.

In March 2023, many professional journalists and members of the public addressed the President of Uzbekistan with a statement about ‘hidden but harsh censorship’ and asked the head of state to ‘provide historical assistance in ensuring genuine independence of the press’ (Journalists, 2023). ‘We want to see Uzbekistan as a strong, competitive, reputable state in the international arena. To achieve this, freedom of the press and speech must be steadily strengthened. However, we believe that the Uzbek press remains under invisible but serious control, in a sad and dangerous situation for the future,’ the appeal says (Journalists, 2023).

It should be assumed that the authors of the appeal were prompted to such an interpretation of what is happening, in particular, by the detention in Tashkent on February 8, 2023, by employees of the internal affairs bodies of the opposition blogger Abdukodir Muminov on suspicion of fraud and extortion, and earlier he was beaten by five men, and his car was smashed with a baseball bat (A journalist, 2023).

Further events confirmed the correctness of the authors of the appeal, when on May 29, 2023, employees of the internal affairs bodies of the Kashkadarya region of Uzbekistan detained the editor-in-chief of the NasafNews online publication and the author of the Telegram channel ‘Captain Karimov’ Umid Karimov, who covered the problems of the Kashkadarya region of Uzbekistan, including the problem of corruption; two bloggers, Otabek Artikov, were detained with him and the author of the AvtoblogUz Telegram channel Maksud Muzaffarov. This was followed by a speedy trial on charges of ‘petty hooliganism’ and ‘failure to comply with the legal requirements of law enforcement officers’ with a ruling on the punishment in the form of the arrest of all three for five days (Three, 2023; A journalist, 2023).

The gradual decline in Russia's rating in the RSF classifier is demonstrated in table 2 and

Figure 2. Other countries of the Central Asian region, such as the former republics of the USSR Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, took 175 and 155 places in the RSF classifier by 2024, respectively, while we will undertake to assert that in these cases the low level of freedoms of journalists and bloggers is also directly related to the aspirations of state bodies to excessive control over the media and the blogosphere.

However, so far we have talked about which specific events provoked a decrease in the location of countries in the RSF classifier. But for every event occasion there are reasons, so what are they?

4.3. Relapses of Authoritarianism: Causes and Consequences

As the root cause of manifestations of authoritarianism in the relationship between government and mass media in Central Asian countries, an excessive share of state bodies in the possession of leading information resources should be considered: a situation is emerging in which the state actually replaces the role of the industry regulator with the role of its owner, which provokes officials of various levels to a team style of relations with representatives of the mass media and blogosphere.

For example, the State National Television and Radio Company (NTC) of Uzbekistan owns and directly controls 12 TV channels of republican significance (nationwide coverage): Uzbekistan, Yoshlar (Youth), Toshkent, Sport, Mahalla (Neighborhood community), Madaniyat va Marifat (Culture and Education), Bolajon (Child), Dunyo Boylab (Worldwide), Cinema, Navo (Melody), Uzbekistan 24 (News), Uzbekistan Tarihi (Historical), the main regional TV channels, as well as 4 radio stations on FM frequencies - Uzbekistan, Yoshlar, Mahalla and Uzbekistan 24. The leading print media in the Republic, such as Xalk Suzi(The Word of the People), Uzbekiston Ovozi (The Voice of Uzbekistan), Uzbekistan Today (in Russian and English), Adolat (Justice), Vatanparvar (Patriot), are also in the possession of the state (Position, 2024).

At the same time, along with traditional types of media owned by the state, the private online media sector has been developing in Uzbekistan in recent years. Thus, according to the National Search System of Uzbekistan, private information portals are among the most popular in terms of attendance, along with reference portals — Daryo.uz (news of the world and Uzbekistan), Qalampir.uz , Gazeta.uz and Podrobno.uz (news from Uzbekistan), Hordik.uz (interesting news) and others (Site, 2024).

A similar situation with ownership rights to mass media has developed, according to RSF, in Kazakhstan, where ‘there are only a few independent media outlets left, including Vlast.kz, Uralskaya nedelya, Respublika.kz.media and KazTAG news agency’. But professional journalists have launched alternative projects on YouTube, Telegram and Instagram, such as Protenge, Za Nami Use Vyekhali and Guiperborei (Hyperborea), which contradict the narrative of the pro-government media" (Kazakhstan, 2024).

According to RSF, Kyrgyzstan also has a similar situation with media ownership rights, since here the ‘government still controls all traditional media and is trying to extend its influence to private media’ (Kyrgyzstan, 2024).

At the same time, since for the bulk of the population, especially for citizens of older generations, the main source of information consumption remains national television, whose broadcasts are under total state control, citizens create a largely incomplete, distorted picture of reality, which, in turn, coupled with a lack of fact-checking skills, forms a low level of media literacy. As a result, the population as a whole has little understanding of politics, observers on the ground note, which is provoked ‘firstly, by a low level of media literacy, lack of critical thinking skills; secondly, apathy, lack of interest in policy issues, caused not least by distrust of the national mass media’ (Kudratkhoja, 2024). Other observers note that the low level of media literacy of the population, in turn, provokes the susceptibility of citizens to disinformation (Abdikarimov, 2023), the immediate negative consequences of this are behavioral changes, confusion, and distrust of users of news sources (Murphy et al., 2023).

The abovementioned, in turn, required us to pay special attention to the aspect of citizens' trust in information sources, which was implemented in the form of a questionnaire survey.

4.4. Citizens' Trust in Information Sources

To clarify what citizens themselves in the Central Asian states, primarily Uzbekistan, think about the development of freedom of speech and national mass media, in the course of this study, a questionnaire survey was conducted among students, faculty of the University of Journalism and Mass Communications of Uzbekistan, as well as their relatives and friends on the topic ‘Do you believe the official media, the private media, or the neighbors?’ (Do You, 2024).

Moreover, Uzbekistan was chosen as the territory of the survey, since this country is located in the conditional center between states that tend to an authoritarian type of relationship between government and society — in accordance with the above dynamics of the level of development of global freedoms, according to Freedom House, such as Russia, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, and countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Confirmation that it is Uzbekistan that is located in this conditional center, we find, among other things, in the publication of media critic Umida Maniyazova, dedicated to the differences in content in various language versions of the mass media of Uzbekistan, which, in particular, notes that "the gap <content of different versions> became noticeable against the background of the war in Ukraine. Uzbek-language media boldly use the terms "war", "occupation", "attack" and "aggression", while Russian-language publications often resort to the rhetoric of the Russian media and use "special military operation" or "conflict" instead of the word "war" (Maniyazova, 2023). At the same time, Maniyazov's media criticism "pleases that Uzbek journalists call the events in Ukraine a war, not a special operation. And also that media representatives who were “intimidated” by the former regime and persecution can, although not much, but still express their position and experts more boldly. Let it be at least within the framework of one topic for now" (Maniyazova, 2023).

However, the Russian-speaking media in Uzbekistan use the Russian terminology of what is happening for a reason: these media thus (consciously or unwittingly) project onto their consumers the point of view of the current political regime in Russia. It turns out that the exact same mechanism applies to the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine and Georgia: a group of researchers studied Russia's efforts in the field of public diplomacy through "analysis of news content exported to its neighbors, Ukraine and Georgia, from February to July 2021, about a year before Russia invaded Ukraine"; The researchers "examined pro-Russian media aimed at Russian-speaking Georgians and Ukrainians, showing that the messages of Russian public diplomacy were not so much about Russia as about anti-Western frames. Local pro-Russian media in Ukraine and Georgia repeated these anti-Western frames in their news reports" (Taylor & ot., 2024); anti-Western propaganda emanating from Russian media in Georgia is also mentioned in a study by R.S. Klem, E.S. Herron & A. Tepnadze (2023).

At the same time, the original Russian media perform similar propaganda tasks quite consciously and purposefully with regard to potential consumers of their information in the West: another group of researchers studied the distribution of "news content from two Russian state-owned media, RT and Sputnik, in digital alternative news media in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Sweden"; the researchers analyzed these The media "as part of the Russian strategy of "acute force" aimed at establishing informational influence in Western news media" (Henriksen; Christensen & Mayerhöffer, 2024).

In fact, the same thing is happening in the relationship of both local Russian-language media and original Russian media with their consumers in the countries of the Central Asian region, in particular in Uzbekistan.

275 respondents participated in the survey, mainly female (68.7%), age categories 18-25 years (52.7%), 25-35 years (18.2%), 35-45 years (17.8%), 45 and higher (11.3%). Students (60.7%) were the most active in participating in the survey, followed by employees (24%), managers/entrepreneurs (12%), and pensioners (3.3%) were the least active.

First of all, during the survey, we took care of the informational interests of the respondents. The answers to the question ‘Which topic (one) in the mass media or/and in social networks interests you the most?’ were distributed as follows: culture/art (35%), unexpectedly many (for the student community) turned out to be those who are interested in politics/economics (32.5%), recreation/ entertainment (20.8%), sports/fashion (11.7%).

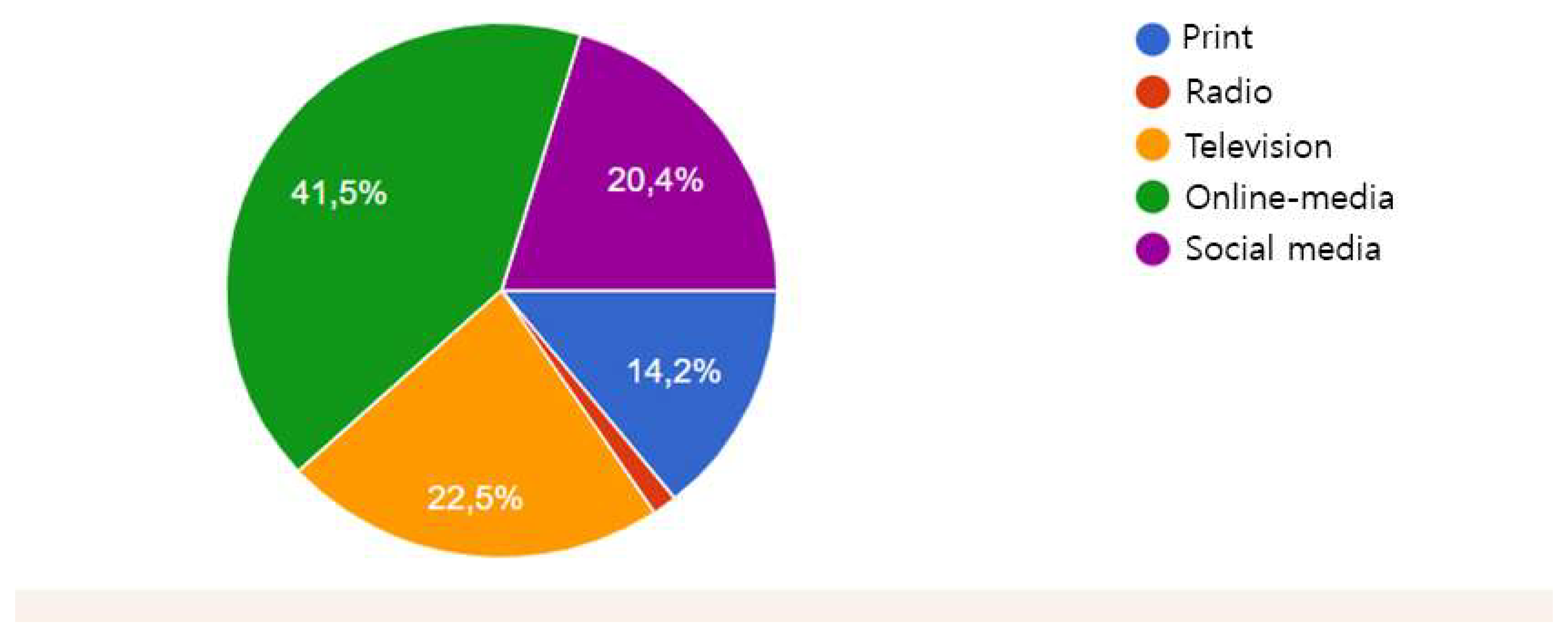

Finally, we have come closer to achieving the purpose of the survey — to find out the respondents' preferences in using information sources. To the question ‘Which (one) source do you trust the most?’ the answers were distributed as shown in

Figure 3.

It follows from the diagram in

Figure 3 that citizens trust online media information most of all, to a lesser extent television, social networks, and to an even lesser extent print media, and there is practically no trust (1.5%) in radio information (due to the weak development of the actual radio market in the Republic of Uzbekistan).

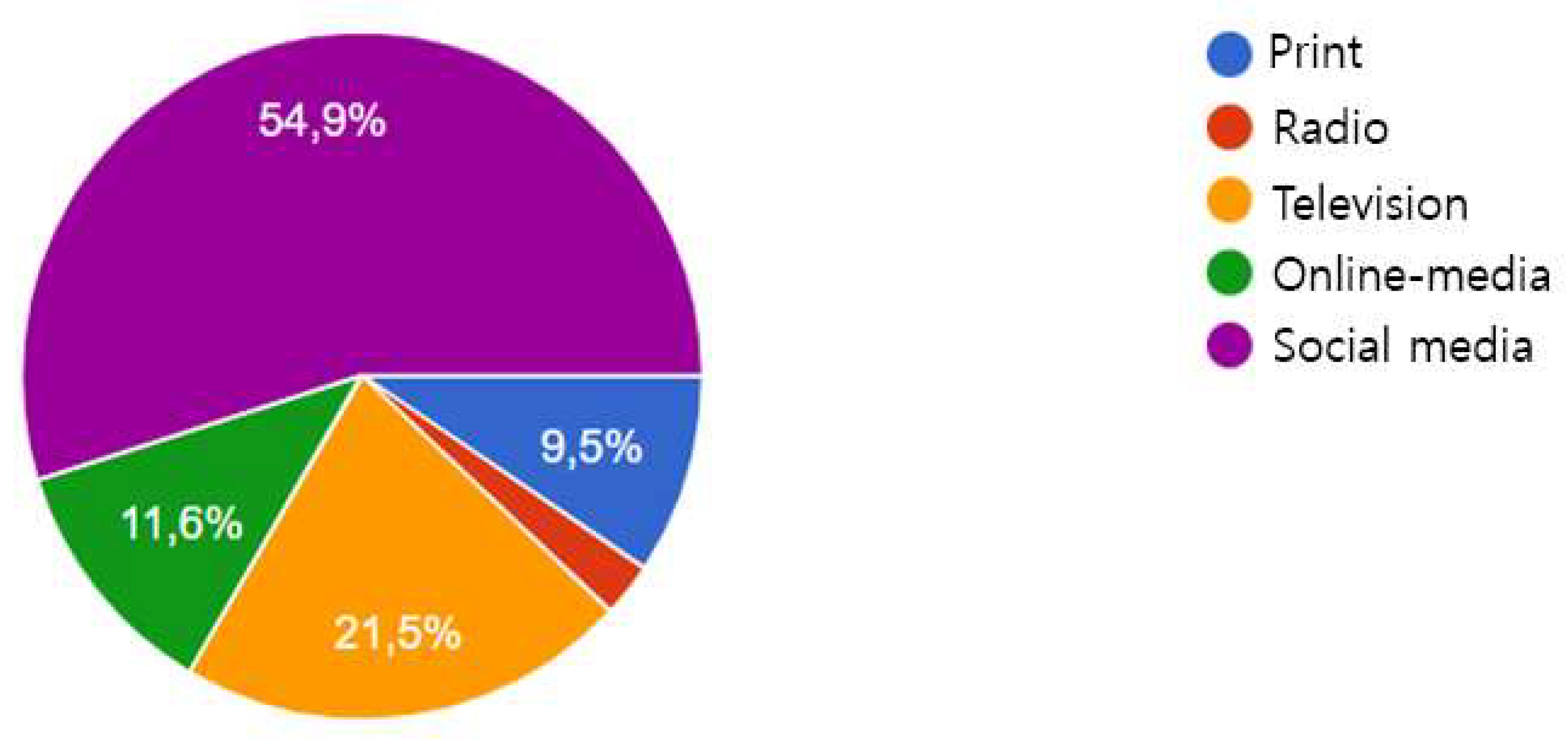

It follows from the diagram in

Figure 4 that out of the total number of respondents (275 respondents), the vast majority of citizen least believe the information published on social networks — 54.9%, 21.5% of respondents do not trust television, followed by online media, print and radio. And this result clearly demonstrates that the population in Uzbekistan, especially the younger generations, have already appreciated the flow of useless or sometimes unreliable (fake) information coming from social networks.

We note that from the data in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, it follows that it is online media that use the greatest preferences in the process of information consumption among citizens. Indeed, according to official statistics, the most popular (traffic) among consumers in Uzbekistan are information portals such as the Kun.uz, Qalampir.uz, Gazeta.uz, Daryo.uz, Podrobno.uz and others (top 15, 2022).

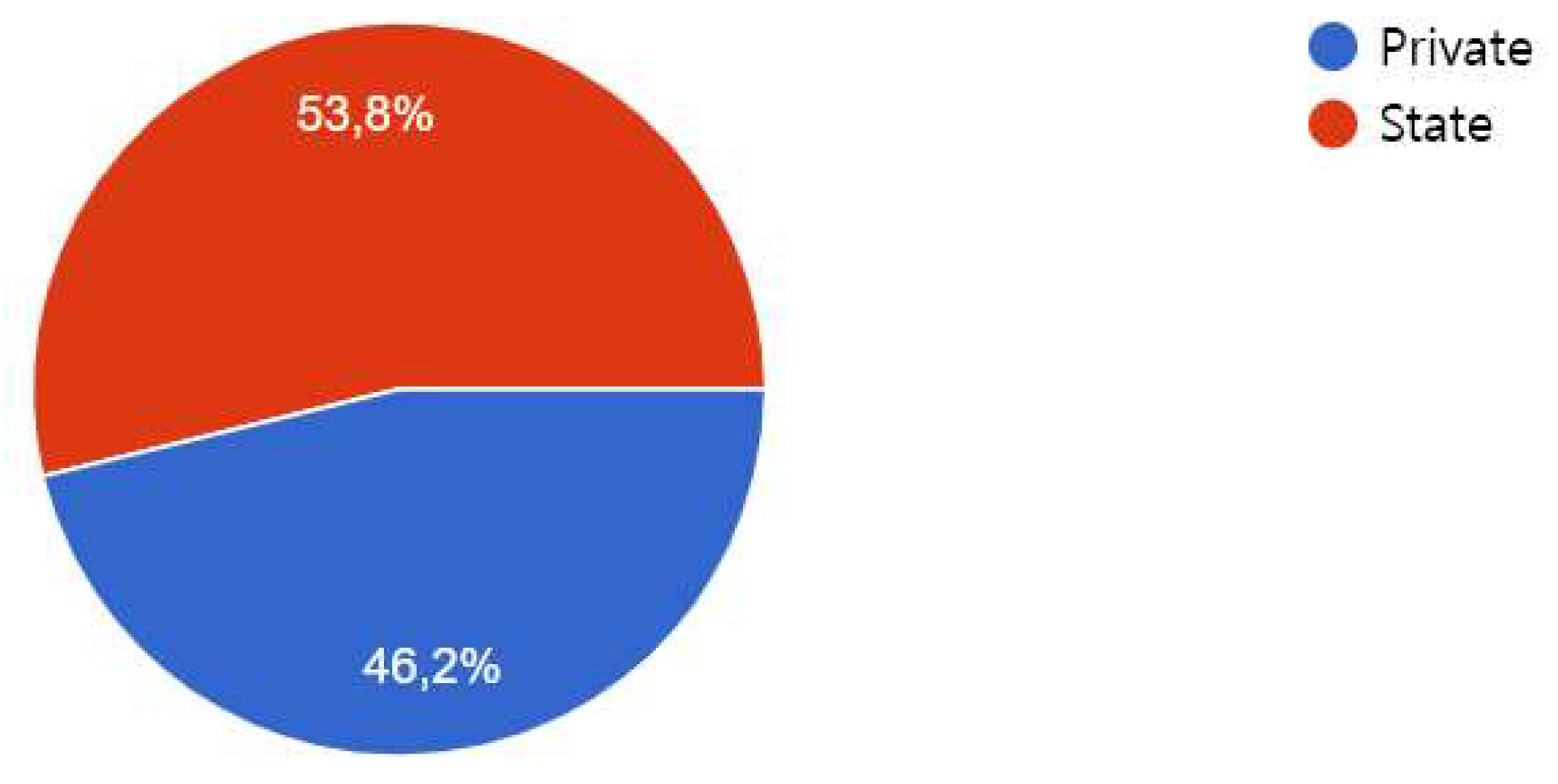

In turn, most of the popular information portals are privately owned and belong to the National Media Association, which in 2022 included 18 non-state TV channels, 19 radio channels and 100 electronic media, including 52 foreign TV channels (NAESMI, 2022). From which it logically follows that it is private online media that enjoy the greatest trust of citizens. This conclusion, however, is contradicted by the results of the survey, which we demonstrate here in

Figure 5, and according to which only 46.2% trust private media to a greater extent, and 53.8% trust public media. This difference, however, seems insignificant to us: in our opinion, it rather demonstrates the desire of citizens, especially young and educated (most of the respondents, we recall, are students) to consume objective, analytical and critical information — since as recently as 2017. Uzbekistan had virtually no access to the market for professional, non-State-controlled information.

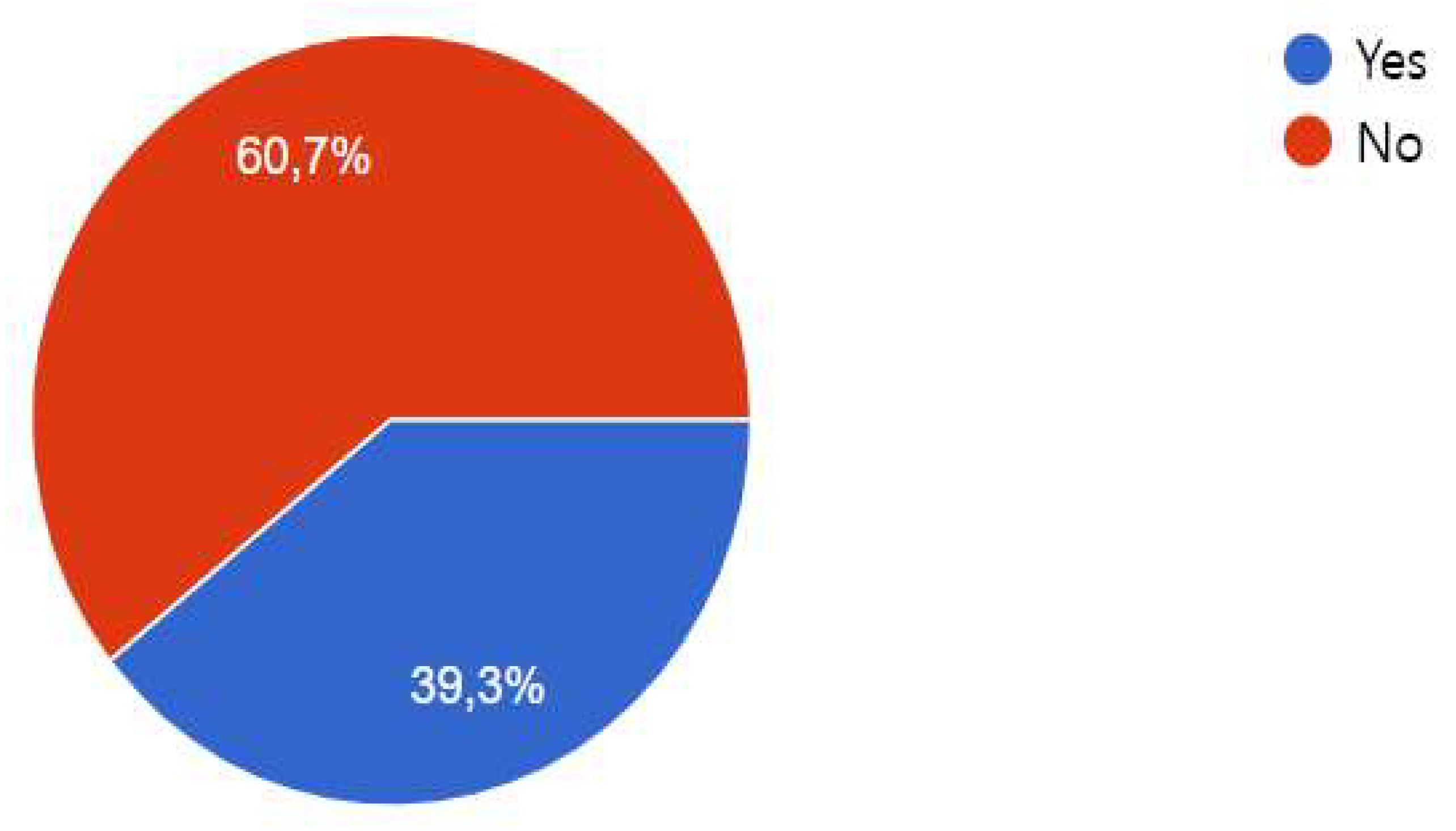

In turn, the results of the answers to the last question of the questionnaire about whether respondents consider the mass media of their country to be free, reflected in the diagram in

Figure 6, contradict the results of the answers to the previous question: the majority of citizens trust the state media (

Figure 5), at the same time, the vast majority consider the mass media to be free 8), which can be explained by the inertia of the country's past during the presidency of Islam Karimov, the fear of contradictions to the discourse of power.

5. Conclusion

So, if, in the course of comparative analysis, we start from the situation with freedom of speech in Uzbekistan, then the mass media of this particular republic, as we demonstrated in the course of the study, are in a better position than in such states of the region as Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, they are more constrained than in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. It is also obvious that the state of Uzbekistan, as well as the authorities of its closest neighbors, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, demonstrates a desire to ‘untie the hands’ of the mass media and blogosphere figures. However, there is a deep divide between the aspirations of the authorities aimed at expanding the scope of freedom of activity of journalists and the media and the real situation: this is especially well seen in the example of Uzbekistan, where the excessive share of state control over the activities of mass media and the blogosphere demonstrated in the course of the study provokes the formation of an exponentially low level of media literacy of the population, weak orientation of the mass of citizens in the internal sphere and foreign policy — while many researchers speak, on the contrary, about the importance of fact-checking skills for the population (Lelo, 2022; Kumar, 2022; Tandoc & Seet, 2022).

Thus, the hypothesis put forward at the beginning of the study — that there are obstacles to the progressive development of freedom of expression in the Central Asian states and, in particular, in Uzbekistan, created (willingly or unwittingly) by representatives of the state power apparatus, should be considered confirmed.

The reason for the obstacles that arise in the way of the development of freedom of speech and professional activity of journalists lies in the dominant role of the state in the ownership of the leading mass media in each of the countries considered here: officials, in this case, carry out the officially assigned role of content managers.

At the same time, obstacles arising from the environment of government officials take the form of political censorship are implemented in the process of copying the practice of the current political regime in Russia applying the provisions of the law on ‘foreign agents’ against national journalists and bloggers whose publications contradict the official discourse of the authorities.

A direct consequence of the above is a relapse of authoritarianism in the domestic politics of the countries of the Central Asian region as a whole and the relations of the state with the mass media and representatives of the blogosphere.

Reasons lead to the formation of a low level of media literacy in the population, poorly versed in what is happening inside and outside the country. Observers note that the immediate negative results of this are behavioral changes, confusion, and distrust of users of news sources (Murphy et al., 2023).

The above allows the authors of this study to formulate recommendations aimed at ensuring the sustainable development of freedom of activity of the mass media and the blogosphere in the states of the Central Asian region. These recommendations consist, firstly, in taking measures to denationalize the ownership rights of most mass media (leaving the state with regulatory functions at the legislative and executive levels), and, secondly, in strengthening the responsibility of representatives of the state apparatus at the legislative and executive levels for obstructing the work of journalists and the media.

In developing the topic for the future, it seems necessary for us to constantly monitor the development of the situation with the development of freedom of professional activity of journalists and representatives of the blogosphere in the countries of the Central Asian region to carry out a comparative analysis of country indicators and publish the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Q., A.A. and N.M.; methodology, U.E. and A.A.; validation, N.M.; formal analysis, A.A.; resources, D.Z. and U.E.; data curation, D.Z. and U.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Q., N.M. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, S.Q.; supervision, U.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdikarimov, Kanat. 2023. The Concepts of “Fake” and “Disinformation” in the Conditions of the Media Environment of Uzbekistan. International Scientifiс Journal of Media and Communications in Central Asia. Tashkent. Journalism and Mass Communications University of Uzbekistan. 3. 26-35. [CrossRef]

- About Guarantees and Freedom of Access to Information. 1997. Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan. URL: https://lex.uz/docs/2118 Date of application: 09.07.2024 (rus).

- A journalist from Uzbekistan closed his media outlet after five days in a special detention center. 2023. Электрoнный ресурс: https://mediazona.ca/news/2023/06/05/NasafNews Date of application: 08.11.2023 (rus).

- Allayarov, Sanjarbek; Ibrohimzoda, Malika; Abdurakhimova, Sayyora; Otamurodova, Mukarram & Antonov-Ovseenko, Anton. 2023. Media Research Management Methodologies as a Tool for Solving Problems of Information and Media Literacy of the Population: a View of Uzbekistan. International Scientifiс Journal of Media and Communications in Central Asia. Tashkent. Journalism and Mass Communications University of Uzbekistan. 3. 4-25. eLibrary ID: 57713065.

- Bahriev, Karim. 2023. Draft Information Code and Media of Uzbekistan. URL: https://newreporter.org/2023/01/17/proekt-informacionnogo-kodeksa-i-media-uzbekistana/ Date of application: 05.07.2024.

- Begalinova, K.K. et al. 2021. Communication modes in Central Asian countries: scientific discussion. Russia and the world: scientific dialogue. Moscow. National Research Institute for the Development of Communications (NIIRK). 1. 2. (rus). [CrossRef]

- Beaufort, M. 2018. Digital media, political polarization and challenges to democracy. Information, Communication and Society. 21:7. 915–920. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.; Lee, F.L.F. & Tan, G. 2024. News innovation under conditions of rapid political change: The influence of state-society relations, organizational culture, and critical events. The Practice of Journalism. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- De Smaele, H. 2006. In the Name of Democracy. In “Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies”. Edited by K. Volmer, 35–48. London. Routledge. URL:https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9780203328668/mass-media-political-communication-new-democracies-katrin-voltmer-thomas-poguntke Date of application: 10.07.2024.

- Do You Trust the Official Media, Private Media or Neighbors? 2024. URL: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1m9DveSEOb9HxbbdLyyOaxeRe2YJOgbg_XAoVm_IZku0/edit Date of application: 14.07.2024.

- Erpyleva, S. and Luhtakallio, E. 2024. The climate is changing, but the president is not: “non-political” climate activism in Russia. European and Asian Studies. 76:6. 891–908. [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, A. 2024. Sympathy or criticism? Reactions of the European far left and far right to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022. European and Asian Studies, 76:6. 829–850. [CrossRef]

- Freedom House. 2004. Freedom in the World 2003: Survey Methodology. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

- Freedom House. 2014. Media Freedom Hits a Decade Low. Washington, DC: Freedom House. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2014/media-freedom-hits-decade-low. Date of application: 10.07.2024.

- Freedom House. 2017. Freedom of the Press. Washington, DC: Freedom House. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/freedom-press-2017. Date of application: 10.07.2024.

- Freedom House. 2019. Freedom in the World. Washington, DC: Freedom House. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2019. Date of application: 10.07.2024.

- Freedom House. 2023. Freedom in the World. Raw Data 2013-2022. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world. Date of application: 22.05.2024.

- Freedom House. 2024. Freedom in the World. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/explore-the-map?type=fiw&year=2024 Date of application: 11.07.2024.

- Gonzalez, R.A. & Echeverría, M. 2022. What is professional journalism? Сonceptual integration and empirical refinement. Journalism Practice. 18:6. 1481–1502. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, J.; Beckers, C. & Van Droogenbrouck, K. 2024. Does news diversity work among audiences? Civil experiment. The Practice of Journalism. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, F. M.; Christensen, J. B. & Mayerhöffer, E. 2024. The spread of RT and Sputnik content in European digital alternative news environments: Mapping the influence of state-backed Russian media across platforms, topics and ideology. International Journal of Press/Politics. 29:3. 795-818. [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Day: freedom of Speech in the Central Asian Region 2022. URL: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/uzbekistan_ru?s=233 Date of application: 17.06.2024 (RUS).

- Journalists and activists contacted the president about “hidden but harsh censorship”. 2023. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2023/03/03/freedom-of-press/ Date of application: 08.05.2024 (rus).

- Karim Bakhriev: everything that happens in Uzbekistan is a struggle between the old and the new. 2022. URL: https://newshub.uz/archives/10648 Date of application: 17.06.2024 (rus).

- Kazakhstan has dropped 12 points in the media freedom ranking over the past year. 2023. URL: https://informburo.kz/stati/kazaxstan-opustilsya-v-reitinge-svobody-smi-za-poslednii-god-na-12-punktov Date of application: 03.07.2024.

- Kazakhstan lost 12 positions in the world press freedom rankings. 2023. URL: https://www.zakon.kz/sobytiia/6392505-kazakhstan-poteryal-12-pozitsiy-v-mirovom-reytinge-svobody-pressy.html Date of application: 03.07.2024.

- Kazakhstan. Media landscape. 2024. URL: https://rsf.org/en/country/kazakhstan Date of application: 03.07.2024.

- Klem, R. S.; Herron, E. S. & Tepnadze, A. 2023. Russian anti-Western disinformation, media consumption and public opinion in Georgia. European and Asian Studies. 75:9. 1535–1559. [CrossRef]

- Kudratkhoja, Sherzodkhon. 2024. The Political Socialization of the People in Uzbekistan: Media Presence and the Absence of Media Literacy. International Scientifiс Journal of Media and Communications in Central Asia. Tashkent. Journalism and Mass Communications University of Uzbekistan. 4: 4-19. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. 2022. Fact-checking methodology and transparency: What do Indian fact-checking sites say? Journalism Practice, 18:6. 1461–1480. [CrossRef]

- Kyrgyzstan. 2024. Reporters Without Borders. URL: https://rsf.org/en/index date of application: 04.07.2024.

- Lelo, T. 2022. When the truth-seeking journalistic tradition thrives: Exploring the rise of the Brazilian fact-checking movement. Journalism Practice. 18:6. 1442–1460. [CrossRef]

- «Many people offer me to “close” the media, but I won’t do it» — Shavkat Mirziyoyev. 2023. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2023/02/24/press/ Date of application: 09.11.2023 (rus).

- Maniu, T. A. 2022. Dynamics of influence on press freedom in various media systems: a comparative study. The Practice of Journalism. 17:9. 1937–1961. [CrossRef]

- Maniyazova, Umida. “Citizen Lukashenko”, “Russophobic hysteria” and other terms: how and how the content differs in different language versions of the media in Uzbekistan. URL: https://newreporter.org/2023/04/12/grazhdanin-lukashenko-rusofobskaya-isteriya-i-drugie-terminy-kak-i-chem-otlichaetsya-kontent-v-raznyx-yazykovyx-versiyax-smi-uzbekistana/ Date of application: 06.07.2024.

- Murphy, G.; de Saint Laurent, C.; Reynolds, M.; Aftab, O.; Hegarty, K. Sun, Y. & Greene, C. M. 2023. What do we study when we study misinformation? A scoping review of experimental research (2016-2022). Harvard Kennedy School. Misinformation Review. [CrossRef]

- NAESMI changed its name, its new general director was appointed. 2022. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2022/05/04/association/ Date of application: 07.07.2024.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2016. The Business of News. In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, N. Domingo and A. Hermida. 51–67. New York. SAGE Publications.

- On approval of the national program of education in the field of human rights in the Republic of Uzbekistan. 2023. Resolution of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan. URL: https://lex.uz/ru/docs/6378543 Date of application: 07.06.2024 (rus).

- Additional measures to ensure the supremacy of the Constitution and the law, strengthening public control in this direction, as well as improving the legal culture in society. 2019. Resolution of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan. URL: https://lex.uz/docs/4647340 Date of application: 07.05.2024 (rus).

- On guarantees and freedom of access to information. Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan. 1997. URL: https://lex.uz/acts/2118 Date of application: 21.03.2024 (rus).

- On introducing amendments and additions to the Criminal, Criminal Procedure Codes of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Administrative Liability. 2020. Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan. URL: https://lex.uz/ru/docs/5186089 Date of application: 07.11.2023 (rus).

- Onuch, O. & Sasse, G. 2022. The Belarus crisis: people, protest, and political dispositions. Post-Soviet Affairs, 38:1–2.1–8. [CrossRef]

- Pizzolo, P. 2023. The geopolitical role of the Three Seas Initiative: Mackinder's «middle range» strategy Redux. European and Asian Studies. 76:6. 873–890. [CrossRef]

- Position about the National Television and Radio Company of Uzbekistan. 2024. URL: https://www.mtrk.uz/uz/corp/nizom/ Date of application: 04.07.2024.

- Press Freedom Index. 2023. Reporters Without Borders. URL: https://rsf.org/en/index Date of the application: 01.04.2024.

- Radio Liberty banned in Kyrgyzstan. 2023. URL: https://www.yenisafak.com/ru/news/3744 Date of application: 03.12.2023.

- Rakhmon asked Putin not to treat Central Asia the way it was in the USSR. 2022. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2022/10/14/tajikistan-russia/ Date of application: 09.07.2024 (rus).

- Reuters: The Minister of Energy of Uzbekistan criticized the idea of a “triple gas alliance” with Russia and Kazakhstan. 2022. St. Petersburg. Fontanka.ru. URL: https://www.fontanka.ru/2022/12/08/71879870/ Date of application: 04.07.2024 (rus).

- Said-Hung, E.; Montero-Díaz, H. & Sánchez-Esparza, M. 2023. Promoting hate speech: from the point of view of the media and journalism. The Practice of Journalism. 18:2. 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Shavkat Mirziyoyev to journalists: “Don’t be afraid, the president is behind you”. 2021. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2021/02/04/president-media/ Date of application: 09.07.2024 (rus).

- Schramm, W. 1964. Mass Media and National Development: The Role of Information in the Developing Countries. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Schwartz, S.A.; Nelimarkka, M. and Larsson, A.O. 2022. Populist platform strategies: A comparative study of social media campaigns of Northern European right-wing populist parties. Information. Communication and Society. 26:16. 3218–3236. [CrossRef]

- Site rating. 2024. National Search Engine. Tashkent. https://www.uz/ru/stat/visitors/ratings?cat_id=0 Date of application: 04.07.2024 (rus).

- Skovsgaard, M., Geiselberg, L., & Andersen, K. 2024. Context-sensitive demand for observer journalism: Dynamics of audience expectations regarding journalists' performance. The Practice of Journalism. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Skulsky, D. 2024. The politics of (historical) love: about patriotism, national history and the annexation of Crimea. Euro-Asian Studies. 76:4. 574–589. [CrossRef]

- Somfalvy, E., & Pleines, H. 2021. The Agency of Journalists in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes: The Case of Ukraine During Yanukovich’s Presidency. Media and Communication, 9:4. 82-92. [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E. C. & Seet, S. K. 2022. War of words: How people react to “fake news”, “misinformation”, “disinformation”, and “online lies”. Journalism Practice. 18:6. 1503–1519. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Maureen; Rice, Natalie M.; Manaev, Oleg; Luther, Catherine A.; Allard, Suzie L.; Bentley R. Alexander; Borycz, Joshua; Horne, Benjamin D. and Prins, Brandon C. 2024. Russian Public-Diplomacy Efforts to Influence Neighbors: Media.

- Messaging Supports Hard-Power Projection in Ukraine and Georgia. International Journal of Communication. 18. 2661-2684. URL: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/20828/4628 Date of application: 11.07.2024.

- The 24.kg editorial office in Bishkek was searched in connection with the case of “war propaganda”. The CEO and editors were taken away for interrogation. 2024. URL: https://meduza.io/news/2024/01/15/v-redaktsii-24-kg-v-bishkeke-proveli-obysk-po-delu-o-propagande-voyny-gendirektora-i-redaktorov-uvezli-na-dopros date of application: 01.07.2024 (rus).

- The European Convention on Human Rights and its protocols. 2024. URL: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/the-european-convention-on-human-rights-and-its-protocols date of application: 01.07.2024.

- The President instructed to strengthen the system for protecting journalists. 2019. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2019/12/16/journalists/ Date of application: 07.11.2023 (rus).

- The Renaissance is impossible without freedom of speech. What was discussed at the round table on media freedom? 2020. Gazeta.uz. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/12/04/freedom-of-speech/ Date of application: 17.06.2024 (rus).

- Three bloggers and several Telegram channels in Kashkadarya announced the suspension of work. 2023. URL: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2023/06/05/blogers/ Date of application: 08.11.2023 (rus).

- Tokayev’s five years in Kazakhstan were marked by unkept promises, and more media censorship. 2024. RSF. URL: https://rsf.org/en/tokayev-s-five-years-kazakhstan-marked-unkept-promises-more-media-censorship date of application: 01.07.2024.

- Top 15 popular media in Uzbekistan: people read less, and watch videos more. 2022. URL: Date of application: 07.07.2024 (rus).

- Torikai, M. 2023. Integration of gubernatorial positions into the federal bureaucratic structure: resignation and career of governors after the end of their term in office in Russia. European and Asian Studies. 75:10. 1651–1676. [CrossRef]

- Uzbekistan rejects the idea of a gas union with Russia. 2022. Moscow. Lenta.ru. URL: https://lenta.ru/news/2022/12/08/say_no_to_gazoviy_union/ Date of application: 12.11.2023 (rus).

- Zaporozhchenko, R. 2024. The end of Russian hegemony in the post-Soviet space? The war in Ukraine and disintegration processes in Eurasia. Euro-Asian Studies. 76:6. 851–872. [CrossRef]

- Yazykova, Tamila. 2024. Zhumangarin on sanctions against Russia: “We do not support, but we will comply”. Astana. Zakon.kz. URL: https://www.zakon.kz/obshestvo/6437032-zhumangarin-o-sanktsiyakh-protiv-rossii-ne-podderzhivaem-no-budem-soblyudat.html Date of application: 07.06.2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).