Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This research explores the integration of biomimicry and architectural/urban genotype concepts to model psychologically acceptable environments. Drawing on foundational psychological theories - Gestalt, Attention Restoration, Prospect-Refuge, and Environmental Psychology - this study examines the private-public interface at the various urban resolutions, encompassing land plots, buildings and urban structures. Biomimicry serves as a unifying framework, linking these theories with principles derived from natural systems to create sustainable and psychologically beneficial designs. The methodology incorporates simulative modeling, employing space syntax and isovist analysis to quantify key spatial features such as proximity, complexity, and refuge. The study evaluates traditional historical architectures from diverse cultural contexts, such as Islamic medina, Medieval European town, and modernist urbanism, to identify patterns of spatial organization that balance human psychological needs and ecological sustainability. Findings highlight the fractal and hierarchical nature of spatial structures and the importance of integrating human-scale, culturally relevant designs into modern urban planning. By establishing a replicable framework, this research aims to bridge theoretical and practical gaps in environmental psychology, biomimicry, and urban design, paving the way for resilient and adaptive environments that harmonize ecological and human well-being.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Importance of Relations Between Humans and Their Environment from a Psychological Perspective

2.2. The Urban Genotype Concept by Hillier and Research Methodology

2.3. Biomimicry Based Features of Acceptable Space and Corresponding Visual Graph Centralities

- Proximity as the feeling that the observer is in a coherent environment where all parts are close to each other should be related not directly to the properties of individual isovists which cover just part of integral spatial, but the spatial network which is conceptually perceived as a whole, e.g., by creating mental maps of a whole structure besides directly perceived viewsheds. In essence, we can say parts of a spatial network could be perceived as closer or more distant. Space Syntax Visual Graph Analysis offers more than one indicator that allows one to compare the closeness of a spatial network to the most reachable point: it could be the Total depth or closeness centrality in the Graph theory terms as a sum of distances from each node to the rest of the nodes where the smallest sum demonstrates the most reachable point and the mean value (Mean Depth) of the sum give an overview of the proximity of every node to the rest of a network. The problem is that neither Total Dept nor Mean Depth is not normalized thus not allowing us to directly compare visual graphs of different sizes, e.g.: buildings of different sizes or even building and urban spaces. In this case, Space Syntax offers Integration which is normalized while comparing a precise spatial configuration with statistically probable configuration of the same size. Integration is calculated in 5 steps based on five formulas which are described by Koutsolampros [33]. To not expand the explanation it just should be pointed out that in essence integration is based on the calculation of Total Depth as a sum of the distance from every node to the rest of the nodes in the Visual Graph while using the formula [34]:

- Fascination (Attention restoration theory), Figure-ground (Gestalt theory), Prospect (Prospect-Refuge Theory) as aspects of space are related to the attraction of attention based on diversity and contrast, the offer of unexpected experience, and activation of imagination because of some hidden parts. It could be expected in the isovists with more complicated and complex forms (e.g., more star shape viewshed). A combination of two VGA indicators could be directly connected to those spatial properties: perimeters of the isovist as it means more visual information, and occlusivity of the length of invisible boundaries that appear when some physical elements block part of the viewshed (e.g., the forest could be seen as a spatial structure where occlusivity of the isovists reaches very high values). To combine both indicators we propose to multiply the isovist perimeter value by its occlusivity. In order to make isovist of different size comparable and reflect fascination just based on spatial configuration but not size of space, the result was divided by isovist area. “Given that an isovist is a polygon, the metrics Isovist Area and Isovist Perimeter measure those properties for that polygon. Note that isovists are simple polygons, thus for every isovist with n vertices on its boundary and xi, yi the coordinates of each vertex calculate the above using” [33]:

- Being away (Attention restoration theory) and Refuge (Prospect-Refuge Theory) features are created by quiet, safe, meditative, and introvert spaces or kind of small rooms that are hidden from the rest of the network but viewed all immediately when entered. In VGA analysis it could be represented by the clustering coefficient which “was expressed as the ratio of the number of cells in an isovist that can see each other to the total possible connections that could exist between those cells (i.e. all-to-all connections). This metric seems to have been developed to measure convexity and compactness as it points out the spaces where all are visible to all (coefficient is 1), but it also seems to be able to point out junctions (low coefficient: standing on a corner where one can see two spaces but the spaces can’t see each other).” [33]. It is calculated by the formula:

- Simplicity (Gestalt theory) is described as the possibility of perceiving spatial configuration as a simple form. There are two essential types of simple spaces in architecture: prolonged spaces with straight corridors as their simplest form and compact rooms with circles as their simplest form. VGA allows identification of both types of isovists. Elongation is counted as skewness or Point First Moment, which is calculated by the formula [33]:

- The circular convex form of an isovist is reflected by its compactness calculations in VGA. The following formula is used [33]:

- Common fate (Gestalt theory) and Continuity (Gestalt theory) are explained as an expression of the perceivable similar dynamic character of spaces. It would be logical to assume that spaces that are more commonly visible from different positions create some kind of common identity and could be related to the common fate aspect. VGA analysis offers Throughvision as an indicator of the most exhibited and commonly viewed spaces. Throughvision of a node-visual cell is calculated simply by counting how many times it appears on a line of mutual intervisibility between all the other cells. A higher value means a higher degree of exhibition.

- The Combination of Prospect and Refuge (Prospect-Refuge Theory) as demonstrated by the close connection yet clear separation between in essence two different types of spaces: one which, according to the above proposed methodology are presented by e.g., high occlusivity and clustering coefficient. Analysis of combinations of those features could be useful and will be used for a more general view and interpretation of the results in a more complex way. Such a decision is grounded on the potential analogy between non-dispersed and dispersed codes which together make a city and refugee and prospect spaces which both are needed for human comfort. If the above mentioned analogy is applied directly, it could be assumed that buildings make refugee spaces while the city provides prospects. If, as discussed earlier, the distinction between non-dispersal and dispersal codes obtains a kind of fractal relation and cannot be separated so clearly, then the Combination of Prospect and Refuge, as a kind of basic complex feature of acceptable environment can be even more helpful in understanding regularities of the investigated architectural-urban systems.

- Compatibility (Attention restoration theory) which shows the correspondence of spatial layout to its function or, in terms of Salingaros – the correspondence between function and composition as one of the three laws of architecture identified by him [35]. It could be addressed while looking for the correspondence between the functional logic of the investigated structure and spatial patterns presented by the isovist indicators described above. Because of the relation to all employed in the research VGA indicators analysis of compatibility between functionalities of real investigated structures and Space Syntax results will be used for at least initial validation of the model while overlapping of “syntactic” and “functional” layers and checking if modeling results are explaining and helping to understand the functional logic of real structure better. Such analysis could be seen as Quantitative-Qualitative Synthesis of two types of data; as an alignment with Real-World Functionality; and as Predictive Capability Assessment meaning that if space syntax indicators consistently correspond with certain functional zones across different cases, it can confirm the model's potential to predict how spatial configurations may perform or adapt in similar functional contexts

2.4. Investigated Objects, Data Used, and Software

- At least three cases should be used to see if the model is sensitive to different spatial-social systems better;

- The investigated urban structures should represent different cultural contexts with different architectural genotypes.

- Because both urban structures and living houses as the basic fundamental architectural cell will be investigated in limited numbers, then the selected cases should demonstrate a kind of homogeneity on both dispersed and not-dispersed genotypes. Besides this, the transspatial nature of the genotype should be observable. In other words, selected cases should be seen as good candidates for the typical representation of the architectural-urban features of represented cultures and urban planning ideologies with relatively similar patterns of living houses.

- Because of the earlier discussion of complex interrelation and mix between distributed and non-distributed codes, it would be good that the selected cities would have clear boundaries that would allow us to see them as a result of both types of genotypes.

- Last but not least: availability of data for space syntax modeling and validation of the results in terms of functional structure, etc.

- Sfax in Tunis is a representative of the medieval Islamic city with its specific labyrinth-like street network which aims not to generate accidental transit in housing clusters, introvert houses demonstrating very similar or even identical patterns focused around the living courtyards, clear functional zoning of urban structure and hierarchy which combines public, semi-public and semi-private spaces, etc.

- Medieval Cracow in Poland is a good representative of European historical urbanism: its street network demonstrates features of both organic and regular gothic city plans; medieval living houses, despite the diversity of architectural forms, demonstrate the same typology and functional patterns; in contradiction to the Islamic city, spatial structure offers a much bigger number of transit options; the city has double-centric structure focused on market square and the castle.

- Elektrėnai in Lithuania was built as a settlement of power plant workers in the 1960-1968. It represents characteristic features of the modernistic city: monofunctional zoning, buildings placed “in a park”; separation of pedestrian and transport flows; limited typology of living flats based on typical, repeated projects of houses; etc. Besides such features, the city has a clear boundary formed by surrounding natural territories.

- OSM data on the UNESCO heritage site in Sfax together with historical city plans which include layouts of individual buildings [36].

- The precise Cracow plan which shows the 18th century situation with defensive wall still standing and morphological structure in essence not changes much from the Middle ages with additional information about functional aspect was used; plans of buildings in Cracow were taken from the web page focused on 3D reconstruction of the city [37];

- OSM data was used to obtain the Elektrėnai plan. Plan of the typical flats were taken from the publication about Soviet modernistic housing by Drėmaitė [38].

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Syntactic Models Based on Compatibility to Form Fits Function Principle

- -

- Elektrėnai: Strong visual connectivity in key nodes thus possible representing car-oriented city plan with representative spaces at the entrance points and buildings, emphasizing spatial homogeneity and uniformity.

- -

- Sfax: Centralized religious and market areas contrasted with corridor-dominated street structures.

- -

- Krakow: syntactic modelling clearly correlated or overlapped with the mani functional zones and streets quite well representing dual functional patterns constructed based on segregation of Town hall square and the castle.

- -

- Hierarchy and Structure - connections between networks and scales.

- -

- Fractal Design - repeating patterns across scales.

- -

- Information Richness - the importance of detail and complexity.

| Architecture Principle | City and Compatibility (1-10) |

|---|---|

| Hierarchical Structure and Scale Relations | Krakow, Poland (8); Sfax, Tunisia (9), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (7) |

| Information Richness | Krakow, Poland (9); Sfax, Tunisia (8), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (6) |

| Fractal Design | Krakow, Poland (8); Sfax, Tunisia (7), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (5) |

| Human Scale Compatibility | Krakow, Poland (9); Sfax, Tunisia (6), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (8) |

| Adaptation to Context | Krakow, Poland (10); Sfax, Tunisia (9), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (7) |

| Biological Analogy | Krakow, Poland (8); Sfax, Tunisia (7), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (5) |

| Connections and Networks | Krakow, Poland (9); Sfax, Tunisia (9), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (8) |

| Importance of Natural Light and Forms | Krakow, Poland (9); Sfax, Tunisia (8), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (6) |

| Resilience and Longevity | Krakow, Poland (9); Sfax, Tunisia (8), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (6) |

| Focus on User Experience | Krakow, Poland ((9); Sfax, Tunisia (8), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (7) |

| Total | Krakow, Poland (88); Sfax, Tunisia (79), Elektrėnai, Lithuania (65) |

3.2. Genotypes

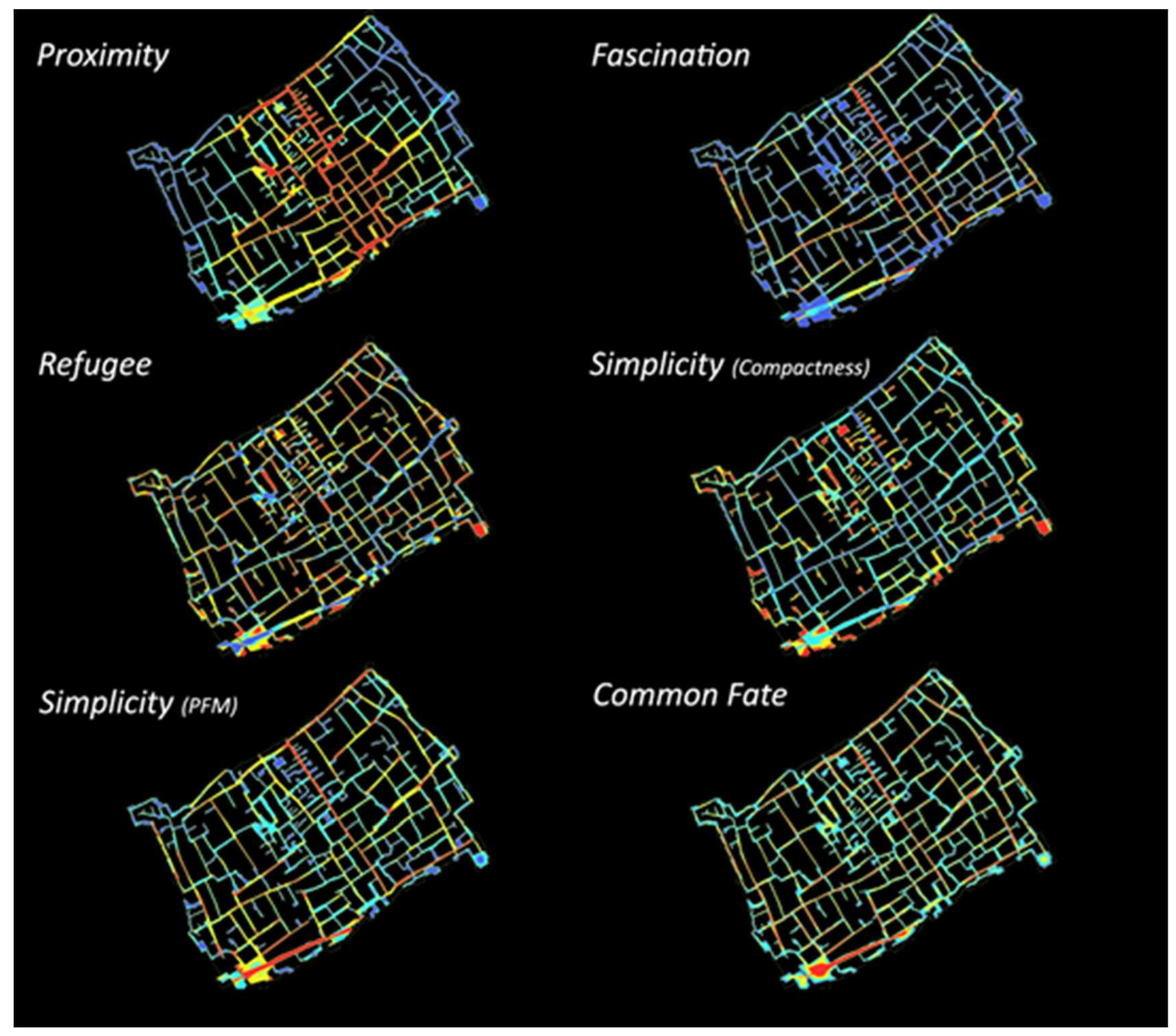

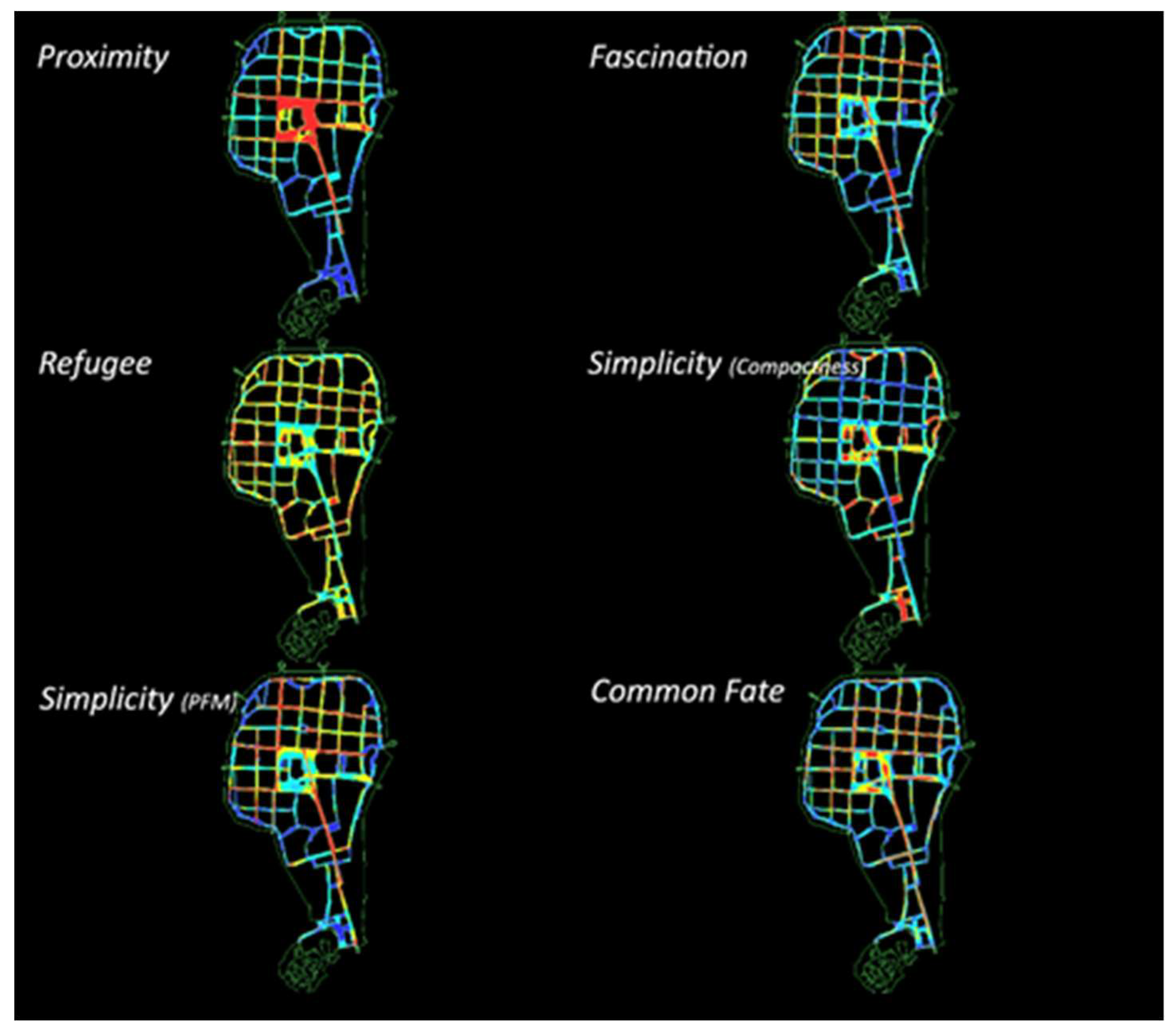

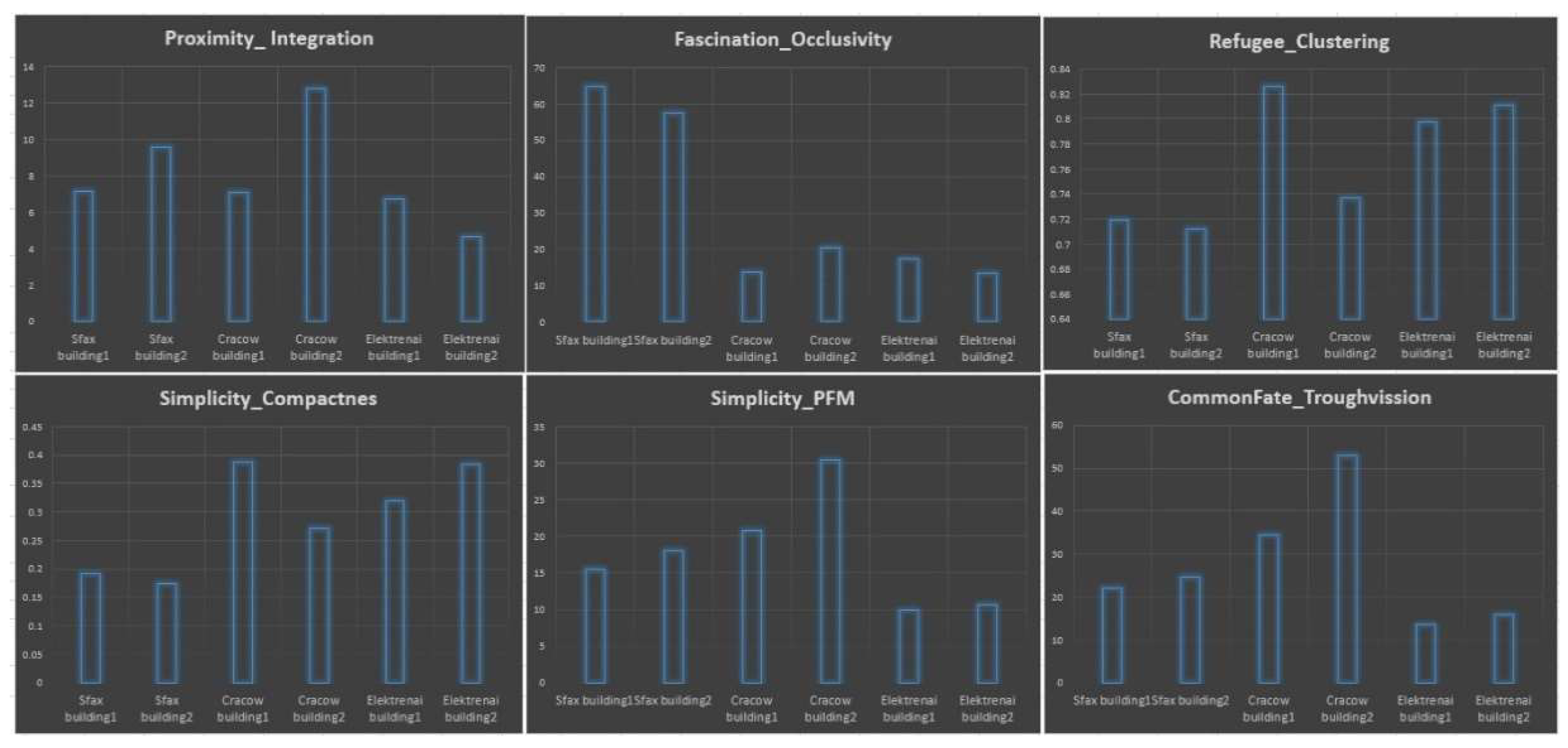

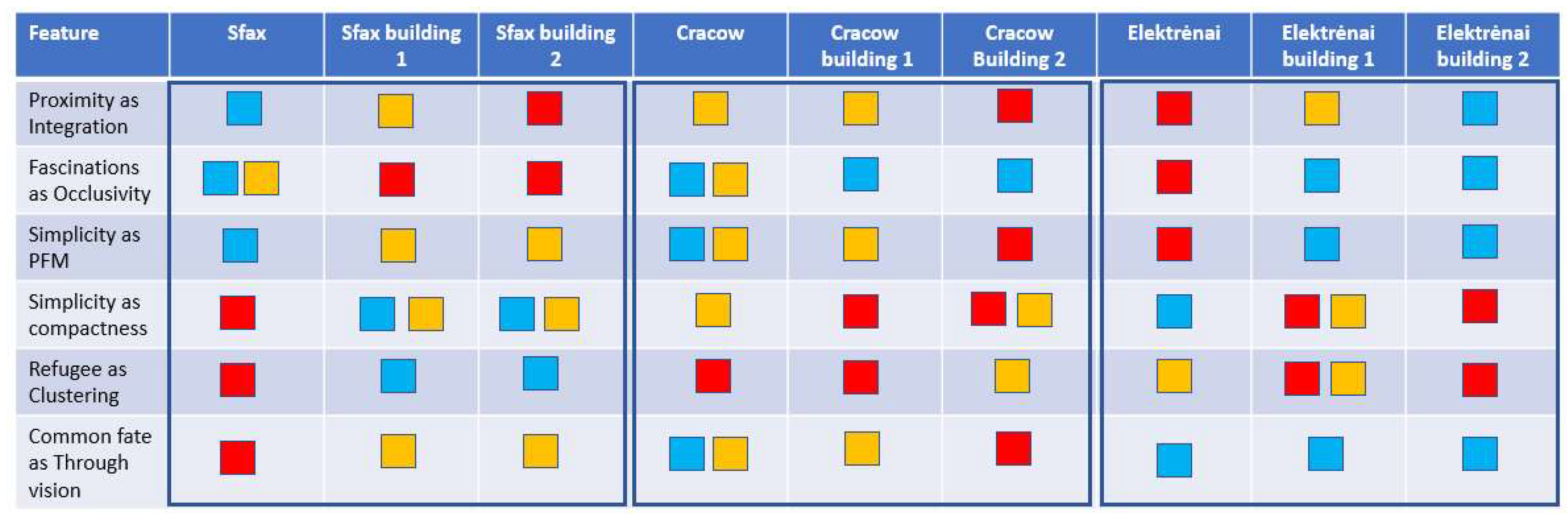

- Proximity as Integration: The low values in Sfax reflect its labyrinth-like structure and functional specialization (public, semipublic, semiprivate, private open spaces, functional zoning, etc.); medium results in Cracow correspond to a more integrative nature of gothic city plan with more functional and spatially homogeneous structure; high values in Elektrėnai well reflect the idea of modernist urbanism when houses are seen as placed in continuous open space – either park or a field.

- Fascinations as occlusivity: low to medium values in Sfax and Cracow demonstrate some kind of controlled, potentially not overloading with visual stimuli, organized in recognizable patterns of high occlusivity features; high values in Elektrėnai speak about potentially overloaded and possible visually overstimulating spatial structure;

- Simplicity as PFM: High values in Elektrėnai, low-medium in Cracow, and low in Sfax. In essence, it reflects openness and degree of visual axe-oriented spatial composition. It could be seen as a kind of clearness of the call or information for a movement of spatial configuration or let us call it dynamic simplicity. If plans of cities are compared then it should be noted that such simple axial lines are clearly defined by contrast with buildings, a limited number of from one-point visible axes, and consistent sequence of presentation of spaces “axe after axe” in Sfax and Cracow. In Elektrėnai a lot of potential axes are visible from the same spots.

- Simplicity as compactness: high values in Sfax, medium in Cracow, and low in Elektrėnai. If combined with PFM-based form simplicity it shows the degree of introversion of spaces which, because of simplicity, allows one to focus on internal processes with less disturbance from neighboring spaces. We can call it static simplicity.

- Refuge as clustering: big values in Sfax and Cracow as a reflection of clearly perceivable in situ combinations “visible and clearly definable here” spaces in terms of Cullen [46] and quite “pockets” or outside rooms in terms of Alexander [47]. Medium values in Elektrėnai demonstrate that modernist urbanism still made an attempt to create quieter or refugee spaces but either closeness is lower or perspectives of visible “there” are much longer if compared to the other two samples. Possibly both are true.

- Common fate as through vision: high values in Sfax, medium to low in Cracow, and low in Elektrėnai. A tree-like street network with a small number of alternative movement routes between origins and destinations of movement and clear separation of various functional zones could be seen as corresponding and explaining the logic behind such results in Sfax. Medieval Gothic plan city focuses on creating more equal alternatives for functions, movement, etc. Modernistic urbanism creates the biggest number of spatial alternatives to look and move thus making features of the common fate hardly perceivable and creating competition between spaces.

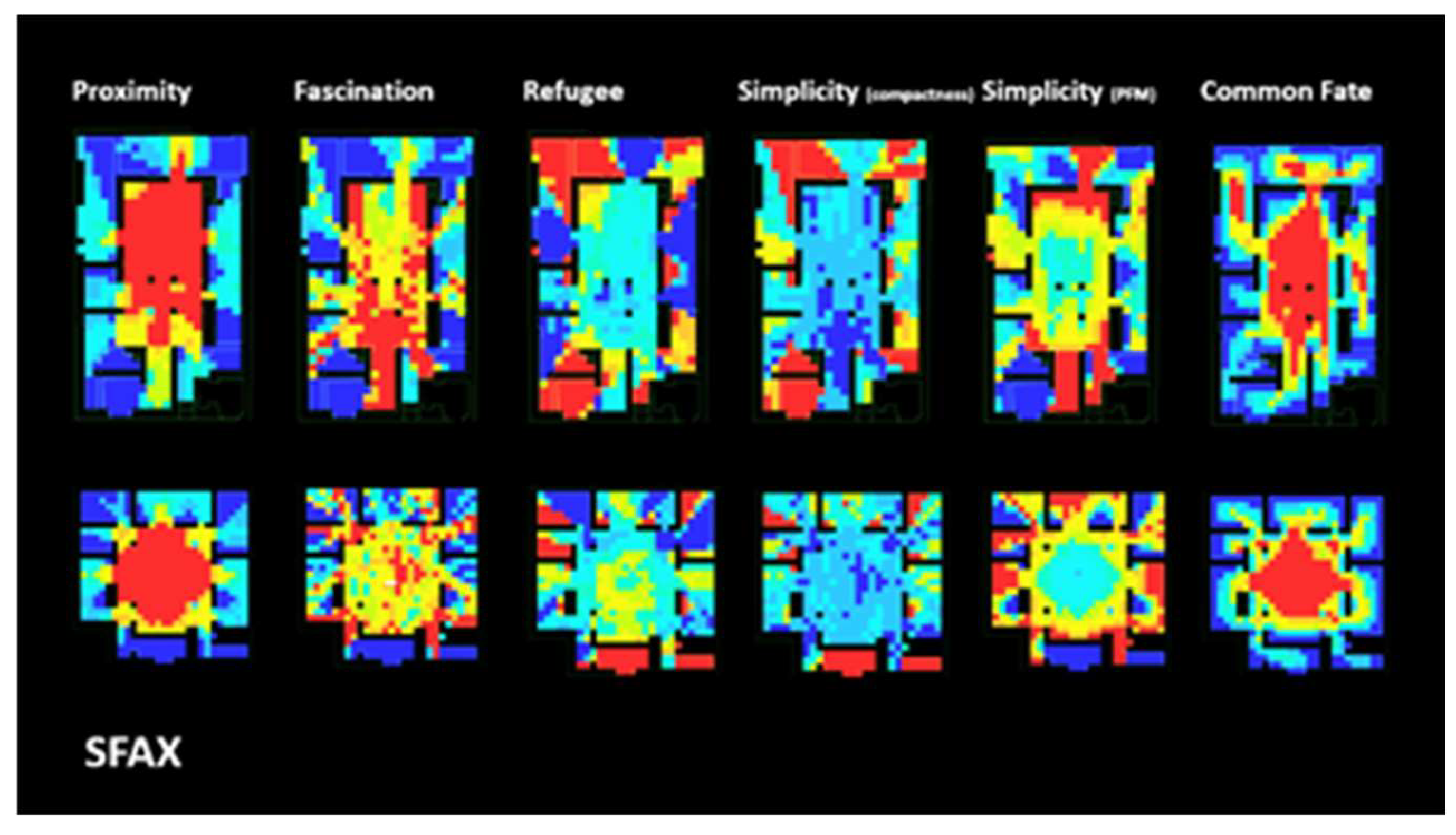

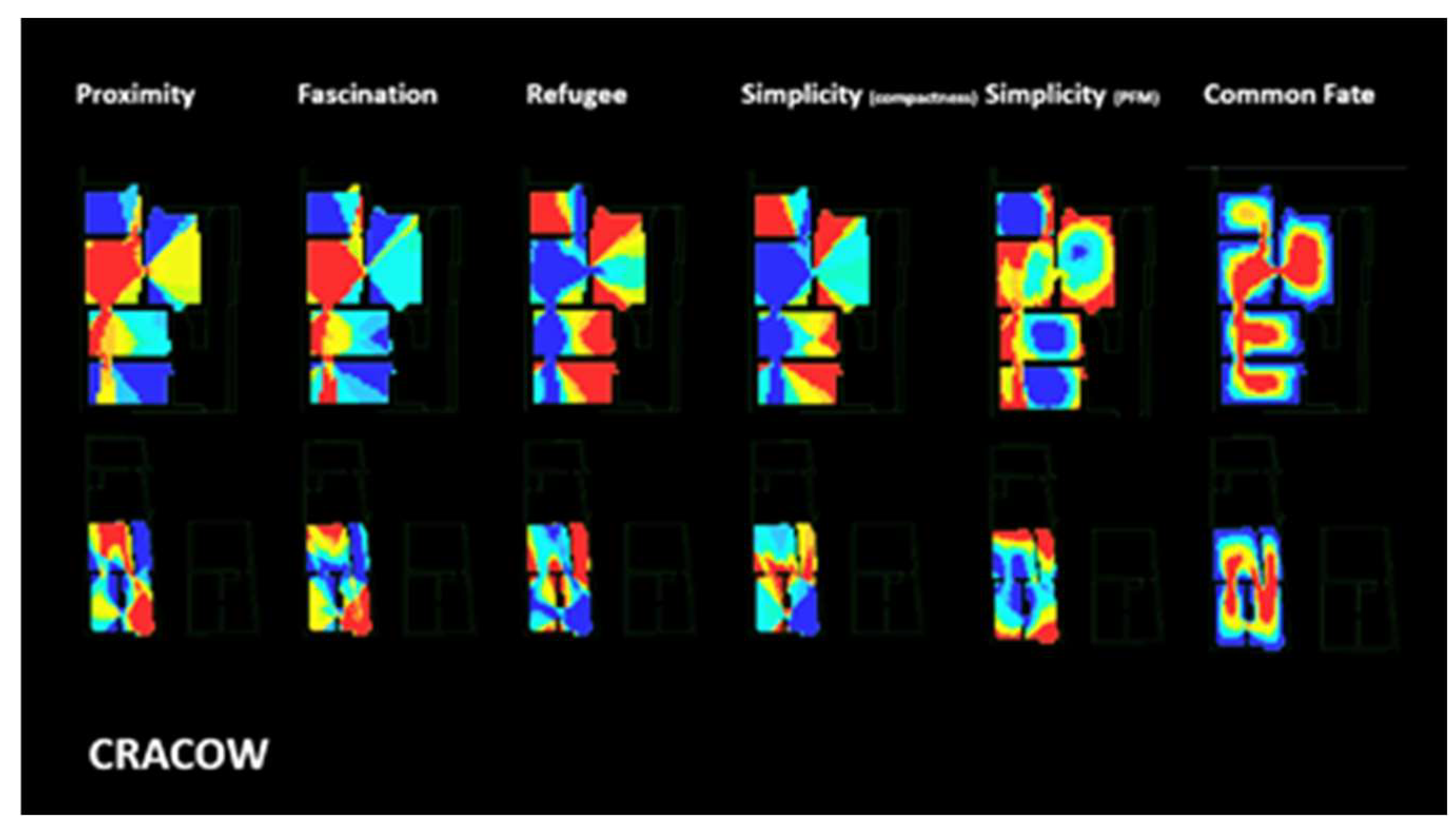

- Proximity as Integration: Sfax and Cracow living spaces demonstrate in general a tendency of bigger proximity (mean-max) in comparison to the modernistic flats (mean-low). It is interesting as the first two groups are represented by in essence bigger spatial structures if compared to Elektrėnai and demonstrate the significance of spatial organization despite size for proximity perception and possibly for the other features.

- Fascinations as occlusivity: high values in Sfax buildings reflect the most sophisticated spatial organization around the living courtyard in the investigated groups of the medieval Islamic living house. Low values in the other cases reflect the very simple yet functional structure of medieval living houses and modernistic Soviet flats

- Simplicity as PFM: Medium dynamic simplicity of the Islamic house and medium-high values of the European medieval houses. Low simplicity in the modernistic flats. The modernistic flat low values are a little unexpected as they are based on the so-called corridor system where the ax of a corridor puts the rest of the rooms together, but, probably, the treatment of rooms as autonomous units and employment of the corridors just as spaces for logistics without the other functions might explain that.

- Simplicity as compactness: medium to low values in the Islamic house with its sophisticated diverse spatial configuration; Medium to high values are observed in the other cases as living spaces there are organized out of autonomous cell rooms.

- Refugee as clustering: low values in the Islamic city thus reflecting its interviewed functional structure, common usage of space (at least by some groups of inhabitants), etc. High-low values in Cracow reflect the focus on autonomous rooms from one side and compositionally important axial connections between them from the other side. High values in Elektrėnai where typical flats could be seen as a collection of autonomous rooms that could be connected by the corridor in one or another way. The shift of this feature could be related to more family as unit-oriented or individual-oriented preferences while creating living spaces as well.

- Common fate as through vision: lowest value in Elektrėnai – it reflects well the structure of autonomous rooms which are connected just by narrow functionally oriented space-corridor. Medium values in the Islamic house are a little unexpected because of its focus on functionally and compositionally dominant living courtyards. Maybe it could be related to the need to segregate certain functions in a living structure. Medium to high values are found in the medieval house.

- We can argue that the situation is right in two cases: for the first decade or more years after the construction of Elektrenai when trees were just planted and made no boundaries for visual perceptions; for a cold season when trees shed their leaves.

- In summer, three are visually active but still, we should recognize that in a city they form rather perforated but not solid wall, especially when courtyards of the houses were intentionally made intervisible so activities of children or other inhabitants could be observed through the windows, etc. In this situation we can expect a decrease of the maximum values of the isovist properties, but there is a high probability that essential spatial patterns would be not changed.

- We can treat the presented results just as an analysis of pura architectural form created by anthropogenic elements.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Gertik, A.; Karaman, A. The fractal approach in the biomimetic urban design: Le Corbusier and Patrick Schumacher. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleckis, K.; Gražulevičiūtė-Vileniškė, I.; Viliūnas, G. Mathematical Graph Based Urban Simulations as a Tool for Biomimicry Urbanism? In press.

- Basu, A.; Duvall, J.; Kaplan, R. Attention restoration theory: Exploring the role of soft fascination and mental bandwidth. Environment and Behavior 2019, 51, 1055–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape theory. Scenic Solutions. 2017. Available online: https://scenicsolutions.world/theory-of-landscape-aesthetics/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E. Restorative effects of nature: Towards a neurobiological approach. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress of Physiological Anthropology; 2008; pp. 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kubovy, M.; Palmer, S.E.; Peterson, M.A.; Singh, M.; von der Heydt, R. A Century of Gestalt Psychology in Visual Perception. Psychological Bulletin 2012, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, R. Gestalt principles. In Information Design; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic, D. Gestalt principles. Scholarpedia 2008, 3, 5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, Å.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landscape Research 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleskienė, E.; Gražulevičiūtė-Vileniškė, I. Landscape aesthetics theories in modeling the image of the rurban landscape. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering 2014, 7, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. Back to nature for good: Using biophilic design and attention restoration theory to improve well-being and focus in the workplace; 2012.

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Brown, T. Environment preference: A comparison of four domains of predictors. Environment and Behavior 1989, 21, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Blanco, E.; Kohsaka, R. Application of biomimetics to architectural and urban design: A review across scales. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haupt, P. Integrated urban landscape: Nature as an element of transition space composition. In Back to the Sense of the City: International Monograph Book; Centre de Política de Sòl i Valoracions: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A. The biophilic healing index predicts effects of the built environment on our well-being. Journal of Biourbanism 2019, 8, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.; Toner, J.; Desha, C.; Gibbs, M. Enabling biomimetic place-based design at scale. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicks, H.; Bertrand-Krajewski, J.L.; Ménézo, C.; Rahbé, Y.; Pierron, J.P.; Harpet, C. Applying biomimicry to cities: The forest as a model for urban planning and design. In Technology and the City: Towards a Philosophy of Urban Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Space Syntax: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 1961; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Leaman, A.; Stansall, P.; Bedford, M. Space Syntax. Environment and Planning B 1976, 3, 147–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; Doxa, M.; O’Sullivan, D.; Penn, A. From Isovists to Visibility Graphs: A Methodology for the Analysis of Architectural Space. Environment and Planning B 2001, 28, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 221–222. [Google Scholar]

- Benedikt, M. To Take Hold of Space: Isovists and Isovist Fields. Environment and Planning B 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.M.; Franz, G. Isovists as a Means to Predict Spatial Experience and Behavior. In Spatial Cognition IV: Reasoning, Action, Interaction; Freksa, C., Knauff, M., Krieg-Brückner, B., Nebel, B., Barkowsky, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3343. [Google Scholar]

- Psathiti, C.; Sailer, K. A Prospect-Refuge Approach to Seat Preference: Environmental Psychology and Spatial Layout. Proceedings of the UCL Symposium, 2017, p. 16. Available online: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1568213/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Koutsolampros, P.; Sailer, K.; Varoudis, T.; Haslem, R. Dissecting Visibility Graph Analysis: The metrics and their role in understanding workplace human behavior. Proceedings of the Space Syntax Symposium, 2019.

- Li, D.; Yan, X.; Yu, Y. The Analysis of Pingyao Ancient Town Street Spaces and View Spots Reachability by Space Syntax. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing 2016, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A. The Laws of Architecture from a Physicist's Perspective. Physics Essays 1995, 8, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meerschen, M. La Medina de Sfax. UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Center 1972, 8, 1–28. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/public/monumentum/vol8/vol8_1.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Plan Krakowskich Bram i Baszt wg Klemensa Bąkowskiego. Available online: http://www.starykrakow.com.pl/dawne-mapy,plany/mapy.htm (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Drėmaitė, M.; Janušauskaitė, V.; Kiznis, N.; Šiupšinskas, M. Jūs gaunate butą: Gyvenamoji architektūra Lietuvoje 1940–1990 metais; Lapabs: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2024; p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A. Depthmap: A Program to Perform Visibility Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Space Syntax, University College London, UK, 2004; pp. 31.1–31.9.

- Hillier, B.; Burdett, R.; Peponis, J.; Penn, A. Creating Life: Or, Does Architecture Determine Anything? Architecture and Behaviour 1987, 3, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. Before Integration: A Critical Review of Integration Measure in Space Syntax. In Proceedings of the 5th Space Syntax Symposium, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands; 2005; pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A.; Mehaffy, M.W. A Theory of Architecture; Umbau-Verlag: Solingen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A.; van Bilsen, A. Principles of Urban Structure; Technepress: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A. Algorithmic Sustainable Design: The Future of Architectural Theory; Umbau-Verlag: Solingen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A.; Alexander, C. Anti-architecture and Deconstruction; Umbau-Verlag: Solingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Concise Townscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- What is Positive Stress? Advekit blog. Available online: https://www.advekit.com/blogs/what-is-positive-stress (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Batty, M. Exploring Isovist Fields: Space and Shape in Architectural and Urban Morphology. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2001, 28, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, M.; Dawes, M. Using Isovists to Analyse Prospect-Refuge Theory: An Examination of the Usefulness of Potential Spatio-Visual Measures. The International Journal of the Constructed Environment 2013, 3, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Peponis, J. Building Layouts as Cognitive Data: Purview and Purview Interface. Cognitive Critique 2012, 6, 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ode Sang, Å.; Tveit, M.; Fry, G. Capturing Landscape Visual Character Using Indicators: Touching Base with Landscape Aesthetic Theory. Landscape Research 2008, 33, 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M.; Longley, M. Fractal Cities: A Geometry of Form and Function; Academic Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Globalization: The Human Consequences; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).