1. Introduction

Suicidal behavior is a serious public health issue since it constitutes a global cause of death and disability. Suicide is known to be a complex, multifactorial, and unforeseeable phenomenon. It is reported that more than 700,000 people worldwide die every year because of suicide, and for each suicide recorded there are more than 20 suicide attempts [

1]. In fact, most subjects with suicidal thoughts do not commit suicide, but suicide ideation may often precede suicide attempts. However, the distinction between suicidal ideation and the progression from ideation to suicide attempts has been discussed in the light of the ideation-to-action framework, which explains them as separate events with different explanations and predictors [

2]. Several factors of psychological, sociodemographic, and environmental nature come into play when discussing suicidal behavior. Mental disorders and substance abuse are associated with up to 90% of suicides around the world [

3], conversely it must be remembered that more than 98% of people with mental disorders do not die by suicide [

4].

Natural or human-made disasters, such as epidemics or wars, may impact on individuals’ psycho-affective balance, and play a role as trigger of suicidal behaviors [

5,

6]. Collective emergencies may bring about potential traumatic effects on individuals’ mental health by reason of their ability to adjust to new, hard, and unpredictable scenarios, or facing the socio-economic consequences arisen from the disaster, such as death or injury of loved ones, loss of financial or domestic stability, and the disruption of sense of community [

7,

8,

9]. Numerous studies investigated suicide-related outcomes during infectious disease epidemics with mixed results. There are reviews which highlight higher rates of suicide among older adults affected by SARS or increased suicide attempts during SARS and Ebola [

10,

11], or greater suicidal thoughts during an epidemic [

5]. One recent study reported that even though the overall rate of death by suicide remained comparatively stationary during the COVID pandemic, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were more prevalent compared to the pre-pandemic period [

12].

At the time of writing, almost 700 million cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, causing 6,901,825 deaths [

13]. The magnitude of ramifications in terms of global involvements, social distancing policies, lockdowns, fear of ostracization, limited access to care, and economic upheaval was staggering. All these changes may be linked to an increase in the incidence of some mental disorders such as acutes stress disorder, PTSD, insomnia and anxious or depressive symptoms, which may have ultimately be related to an increase in risk of suicide [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Moreover, Sars-CoV2 infection

per se could work as trigger for suicidal behavior [

19].

Subjects suffering from mental diseases present heightened sensitivity to stress. While under pressure, they represent a population more vulnerable to develop new conditions or to experience worsening and exacerbation of previous symptoms [

20,

21]. Furthermore, especially during the first phase of the outbreak, patients generally witnessed limited access to psychiatric departments, together with a reduced ability to refer to the outpatient clinics, with potential implication on feelings of loneliness and treatment compliance [

22]. In fact, there is evidence that social isolation and loneliness, along with lack of social support, that were all sharpened by the coronavirus pandemic, are associated with mental health problems [

23,

24]. In the US about 4% of yearly accesses to Emergency Departments (EDs) are prompted by suicidality [

25]. Moreover, EDs usually provide care for people with other risk factors suicide, so that even when suicidality may not represent the overt reason for access, the ED consultation may unveil a current suicide risk as part of a broader constellation of symptoms [

26,

27]. Therefore, EDs are a privileged observatory for the whole spectrum of suicidal behaviors [

28]. In this scenario, we recently conducted a study aimed at describing the characteristics of subjects who accessed three EDs for suicidality in Lombardy (the first Italian hotbed of COVID-19 and one of the regions hardest hit) during the period 8 March – 3 June 2020 (corresponding to the

first wave of COVID-19 in Italy), and to compare them with subjects accessing the same three sites in the corresponding time frame in 2019 . Results showed that the proportion of subjects accessing the ED for suicidality in 2020 was significantly higher compared to 2019, and that a greater percentage of subjects did not show any mental disorder and were psychotropic drug-free. To further evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on suicidality, the present study aims to extend our previous investigation to the

second wave of the pandemic (namely, the time lapse between Jun 4th and Dec 31st 2020), and to compare data with the same period in 2019.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted at five EDs (Lodi-Codogno, San Matteo-Pavia, Fatebenefratelli-Milan, Voghera, Vigevano) in Lombardy. The epidemiological and territorial features of Lodi-Codogno, San Matteo-Pavia and Fatebenefratelli-Milan, are described in the previous study from our research group, focusing on the first wave of the pandemic [

27]. Two further ED sites were added in the present study, Voghera and Vigevano. Both sites are included in the Pavia district and provide 24/7 psychiatric emergency service, complementing data gathered in the San Matteo-Pavia site.

A retrospective chart review of medical records was carried out at the five EDs using hospitals’ computer databases of emergency rooms reports. All subjects (i) older than 18 years, and (ii) accessing the five EDs for suicidality between June 4th and December 31st were selected for inclusion in the analyses. In addition, subjects meeting the inclusion criteria throughout the same period of 2019 were included as a comparison group. The total number of subjects referring to the EDs and going through a psychiatric evaluation during the two periods was also annotated.

Data were extracted anonymously and included main sociodemographic features such as sex, age, nationality (Italian vs. other), housing, marital and occupational status, usual psychiatric care provider, history of alcohol and substance use, phase of access (Jun 4th – Sept 30th vs. Oct 1st – Dec 31st), and clinical data, namely mode of access to the ED, type of suicidality (suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, self-injuring, drug ingestion, agitation), reason for suicidality (exacerbation, reactive, intoxication), triage priority level (high vs. low), consciousness, comorbidity, psychopharmacological treatment prescribed before/during/after ED consultation, discharge diagnosis (anxiety/mood/psychotic/personality disorder/no mental disorder, harmful substance use), and instructions at discharge (admission to the inpatient psychiatric service, referral to the outpatient Mental Health/Addiction service or both). For subjects admitted to the ED during 2020, the presence of COVID-related stressors was also annotated (self-infection, infection of close ones, economic difficulties, isolation from usual social environment, other). The period between June 4th and Sept 30th, when COVID-19 cases were very few, and virtually no lock-down measures were implemented, was designated as low-epidemic stage; the period between Oct 1st and Dec 31st, when the number of COVID-19 cases rose and new lock-down measures were imposed, was designated as second peak epidemic stage. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding medical research in humans and it satisfied local research ethical requirements. In particular, the privacy of research subjects and the confidentiality of their personal information were protected by anonymization of all collected data. As a retrospective, non-interventional, low-risk study, the institutional review boards at each participating site approved the study protocol and the local ethic committee was notified before study initiation. This research received no external funding. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Analyses were performed with SPSS, version 27 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y., USA [

29]). Frequency of categorical variables is reported as number and percentage of cases. Continuous variables are presented with means and standard deviations (SD). Socio-demographic and clinical variables were compared between subjects accessing the ED in 2019 vs. 2020. Additional analyses were conducted among the 2020-year group to compare subjects based on sex, phase of outbreak and district of enrolment (Milan vs. Lodi-Codogno vs. Pavia-Voghera-Vigevano). Chi-square test, with post-hoc Bonferroni, has been used to compare categorical variables. Student

t-test has been used to compare means of continuous variables. Chi-square with Odd Ratios (OR) values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) was performed to find significant predictors of admission to the psychiatric inpatient unit in 2020. A

p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Subjects Accessing the ED for Suicidality During the Second Wave of COVID-19 in 2020

Overall, 354 subjects accessed the ED for suicidality (29.4% in Milan, 33.1% in Lodi-Codogno, 37.6% in Pavia-Voghera-Vigevano), with 66.9% between June 4th and Sept 30th, and 33.1% between Oct 1st and Dec 31st. Most of them were Italian (81.9%), unemployed (36.4%), and unmarried (46.3%). Most subjects were not in touch with any mental health or addiction service/practitioner (57.9%), and did not report a history of substance abuse (73.2%). Half of the subjects were admitted to the ED for intentional prescription drug ingestion (49.4%), followed by subjects accessing the ED for suicidal ideation (27.1%), self-injury (15.5%), suicide attempt (5.6%), and agitation (2%). In more than half of cases, suicidality arose from a triggering factor (54%), followed by the exacerbation of a previous mental disorder (40.1%), and acute intoxication (5.9%). Of 354 evaluated subjects, 74 (21,4%) reported a COVID-related stressor, identified as a SARS-COV-2 infection of self/relatives, death of relatives due to SARS-COV-2 infection, or economic distress due to the pandemic. Upon discharge, the largest part was diagnosed with a personality disorder (42.4%), followed by affective disorders (23.7%), no mental disorders/harmful substance use (20.1%), anxiety (9.5%) and psychotic (4.3%) disorders. All frequencies, percentages and statistics regarding following results (i.e., comparison by district of admission, pandemic phase and gender), are shown in supplementary tables.

3.1.1. Distribution by District of Admission

A greater proportion of students (12.5% vs. 5.1% and 4.5%), and unmarried subjects (62.5% vs. 50.4% and 30.1%), and fewer retired subjects (4.8% vs. 16.2 and 11.3%) were evaluated in Milan. In the Pavia district, a smaller proportion of unemployed subjects was evaluated (26.3% compared to 42.3% and 42.2% ). A higher proportion of subjects presented with suicidal ideation in the district of Milan (37.5% vs. 29.1% and 17.4%), and a higher number of suicide attempts was registered in the district of Pavia (10.6% vs. 2.9% and 2.6%). In Lodi-Codogno, fewer subjects presented with an exacerbation of a previously known condition (48.7% vs. 62.5% and 67.7%), while a higher proportion of accesses for suicidality was during an episode of acute intoxication (10.3% vs. 2.9% and 4.5%). Most subjects who reported a COVID-related stressor were admitted to the EDs of Lodi-Codogno (35.3% vs. 13.5% and 15%). Full statistics and comparisons by district of admission are shown in supplementary tables.

3.1.2. Distribution Between Low-Epidemic and Peak-Epidemic Stage

Most accesses for suicidality (66.9%) occurred between June 4th and Sept 30th, identified as low-epidemic stage. A greater percentage of subjects (59.3% vs. 21.6%) was evaluated for a suicidal behavior (i.e., any reason of access other than suicidal ideation) in this period compared to the following time lapse (Oct 1st - Dec 31st, 2020), identified as second peak-epidemic stage. A significantly greater percentage of subjects in the latter period was admitted for exacerbation of a previously diagnosed mental disorder (47.9% vs 36.3%) and for suicidal ideation (38.5% vs. 21.6%) compared to the low-epidemic stage. A significantly higher proportion in this period was diagnosed with a personality disorder diagnosis upon discharge from the ED (56% compared to 35.6% during the low-epidemic stage), while fewer patients were diagnosed with depression (12.1% vs. 29.6%). (See supplementary material for full statistics and comparisons).

3.1.3. Distribution by Sex

A significantly greater percentage of women than men were already taking any psychotropic medications prior to access (73.4% vs 60.4%). Comparisons by each medication type, showed that women were more likely to being taking antidepressants (54.5% vs 32.6%) and anxiolytic (67% vs 45.8%). Women were significantly more likely than men to access the ED voluntarily (36.2% vs 22.2%), to be discharged with a diagnosis of personality disorder (47.1% vs 35.5%), and to be instructed to reach a psychiatric outpatient center for follow-up after discharge (41% vs 29.9%).

Compared to women, a greater proportion of men had a history of substance abuse (35.2% vs 21.1%), were admitted to the ED for acute intoxication (9% vs. 3.8%), and through the intervention of the police force (11.8% vs 2.4%). A significantly greater percentage of men reported a COVID-related stressor (26.6% vs 17.6%). (See supplementary material for full statistics and comparisons).

3.1.4. Risk for Admission to the Psychiatric Inpatient Care Unit

No difference was found in the admission rates among the five EDs, nor between the two pandemic phases. Among a range of possible risk factors (sex, taking antidepressants/anxiolytics/mood stabilizers/antipsychotics, suicide attempt vs. others, having/not having a psychiatric diagnosis and each specific discharge diagnosis, COVID-related stressor), being taking medications before the admission (78.3% vs. 63.1%, OR 2.1, CI=1.3 – 3.5), being admitted for a suicide attempt (11.6% vs 2.2%, OR 5.8, CI=2.0–16.2) and having a depression diagnosis at discharge (36.5% vs 16.6%, OR 2.9, CI=1.7 – 4.8) were shown to significantly increase the risk of being admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit.

3.2. Comparison Between 2020 and 2019

A total number of 2,847 subjects were referred to the ED and went through psychiatric evaluation in the five centers between June 4th and Dec 31st in 2020. Among them, 354 (12.4 %) did so for suicidality. In the same period of 2019, 3,335 patients accessed the EDs and underwent psychiatric consultation, 379 (11.4 %) for suicidality (Chi-square=1.682, p=.194).

Socio-demographic comparisons between subjects accessing for suicidality in 2020 and in 2019 are shown in

Table 1. Accesses for suicidality in 2020 decreased significantly in the center of Milan (29.4% vs 37.7%) and increased in Lodi-Codogno (33.1% vs. 23.2%). No differences were found regarding gender, age nor nationality of subjects. A higher frequency of employed subjects was found during 2020 (22.9% vs 15.6%), along with a higher frequency of subjects living alone (22.3% vs. 16.4%). Unknown status for profession (22.6% vs 33%), marital status (18.9% vs 27.7%) or housing (15% vs 23.7%) was less frequent in 2020 compared to 2019.

Clinical comparisons between subjects from 2019 and 2020 are provided in

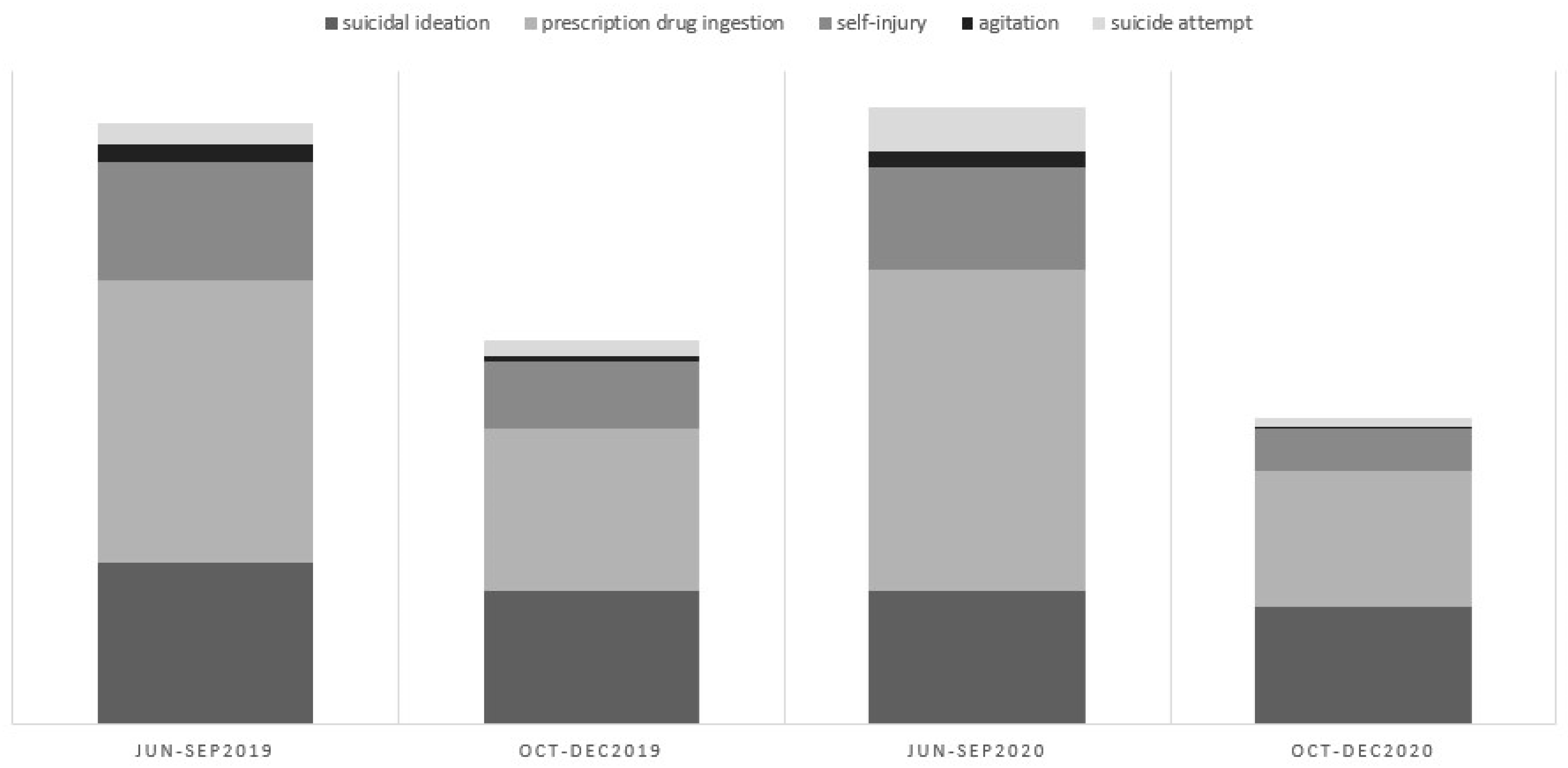

Table 2. No differences were found for the means of access to the ED, nor for triage priority level. Distinct types of suicidality prompting the ED evaluation (e.g., ideation, drug ingestion, suicide attempt) were similarly distributed in 2020 and 2019 (

Figure 1). In 2020, a higher proportion of subjects with no previous contacts with either mental health or addiction service/practitioner was found (57.9% vs 34.8%), as well as with mental health service/practitioner alone (40.1% vs 60.7%). Rates of admission to the psychiatric inpatient unit did not differ between the two years. However, a higher number of subjects received the indication of both psychiatric and addiction outpatient follow-up in 2020 (8.8% vs. 2.9%). As shown in

Table 3, a greater percentage of subjects taking anxiolytic medications at home were evaluated in 2020 (58.4% vs 50.8%), along with fewer subjects treated with mood stabilizers (12.7% vs 19.3%).

4. Discussion

The aim of our study was to analyze the sociodemographic and clinical features of subjects accessing the psychiatric emergency service for suicidality during the second wave of COVID-19 (June-December 2020) in three districts in Lombardy, and to compare the characteristics of the patients evaluated during the second wave of the pandemic to those assessed in the same period in 2019. Firstly, the proportion of subjects entering the ED for suicidality did not change significantly between the two years, nor did the proportion of the different reasons prompting the access to the ED (

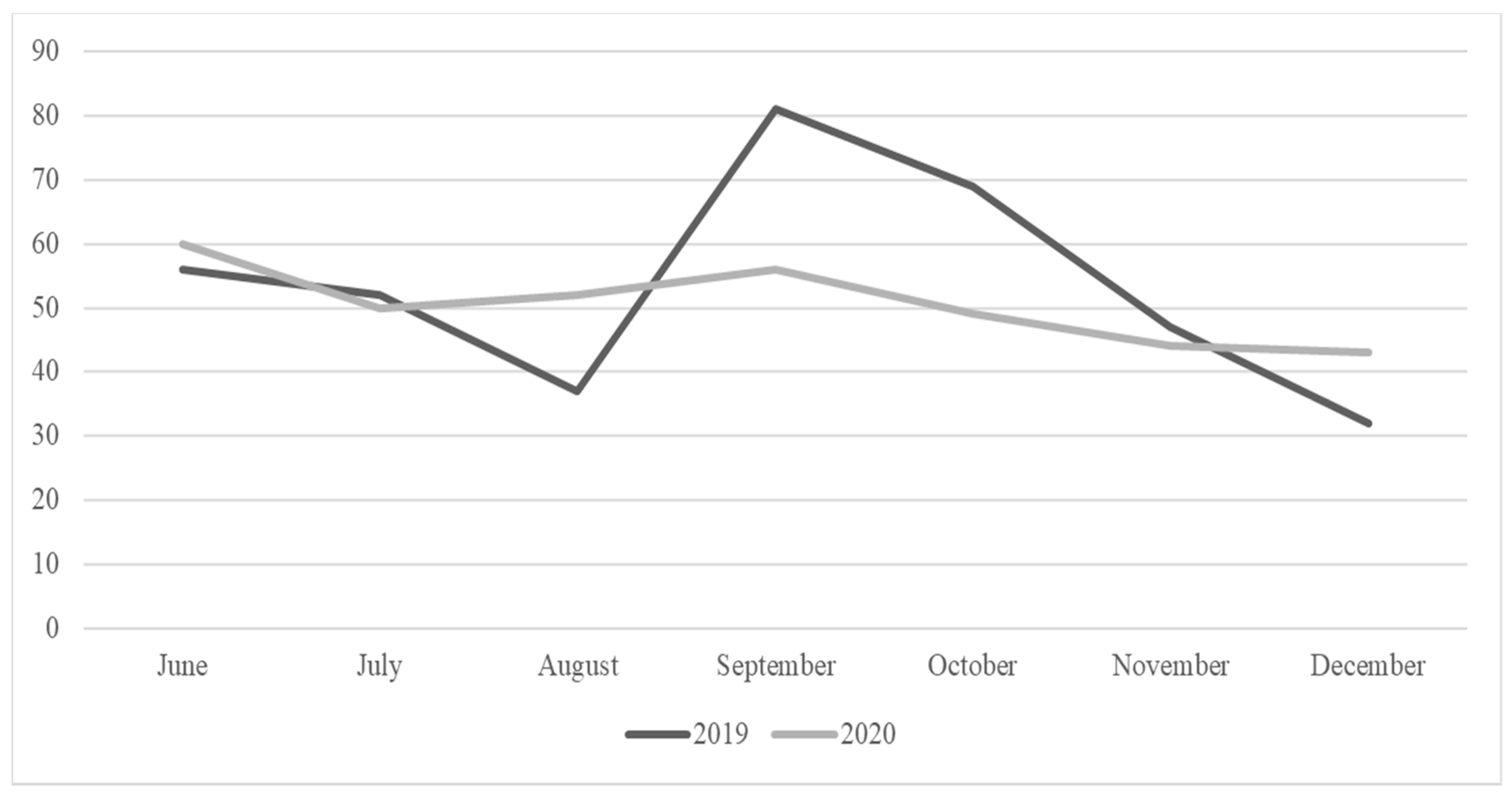

Figure 1). Still, a contraction in the total number of admissions for any cause (3,335 in 2019 vs. 2,847 in 2020) could be observed, causing a slight, non-significant increase in the percentage due to suicidal reasons. It is arguable that some general pandemic-related factors, such the fear of contagion and the restriction of movement enforced by law, led to a reduction in psychiatric evaluations for minor causes in the ED, reducing the overall number of admissions, with the number of accesses for suicidality bound to remain almost stable. Compared to our previous findings from the first wave of COVID-19, showing a significant increase in admissions for suicidality from 2019 to 2020, the present findings seem to set an overall trend of return to a pre-pandemic level of suicidality. However, breaking down data by month, we found that while the overall number of accesses for suicidality was similar in 2020 and 2019, the distribution of accesses in 2020 was much more stable across time compared to 2019 (

Figure 2). This might suggest an effect of the pandemic on suicidality, prevailing the effect of other factors.

More in depth evaluation of suicidality still revealed some significant differences between the two years. Compared to 2019, subjects referred to the EDs in 2020 were more likely to be employed and to be living alone. Moreover, in 2020 a greater percentage of subjects seen for suicidality had never been seen by any mental health professionals but were more often advised to pursue both psychiatric and addiction follow-up upon discharge from the ED. This may indicate that COVID-19 posed a significant burden of stress and uncertainty on people living alone and actively working, possibly leading to new-onset mental conditions [

30]. Somehow consistently, people seen in 2020 were more likely to be prescribed with psychotropic agents largely used in general practice (i.e., anxiolytics) at the time of admission to the ED, and less likely to be prescribed with highly specialistic agents (i.e., mood stabilizers), suggesting a higher proportion of new onset psychiatric conditions, as also found in other EDs [

31]. Our data align with previous meta-analyses suggesting that covid-19 pandemic-related variables are a risk factors for developing suicidal ideation [

12,

32,

33]. In our overall sample, 21.4% of the subject with suicidality reported a COVID-related stressor, the majority of which were admitted to the EDs of Lodi-Codogno, namely the first Italian hotbed of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy [

34,

35].

Breaking down data by the two epidemic phases (low epidemic and peak epidemic) allowed us to draw a more detailed picture of suicidality across the wax and wane of COVID-19 pandemic. The low epidemic phase corresponded to higher frequency of suicidal behaviors (i.e., other reasons than suicidal ideation) and affective diagnoses upon discharge from the ED, while the peak epidemic phase showed a greater prevalence of suicidal ideation and personality disorders. Some studies showed that suicidality may remain stable during active phases of the pandemic, driven by a sense of community and closeness, and it may rise during phases of hardship relief [

36,

37,

38]. This may be mirrored in the higher percentage of suicidal behaviors we found during the low epidemic phase, which followed the peak epidemic phase of the first wave. On the other hand, it is also possible that home confinement, again enforced during the peak epidemic phase of wave two, could have played a plastic role on suicidality, preventing the enactment of suicidal behaviors and increasing suicidal thoughts. With regard to differences in the way men and women manifested suicidality during the second wave of COVID-19, our data closely align with our study conducted on the first wave of COVDI-19 [

27], showing a greater likelihood of men to be seen for suicidality in the context of substance intoxication and externalizing behaviors, as suggested by the greater frequency of access through the public force in the present study. Again, according with our previous study, women were more likely to be already treated by a mental health service/professional while accessing the ED and more likely to be advised to pursue treatment after discharge. While these findings may actually reflect more general differences in symptom manifestation, propension to treatment and clinical management between sexes, it is noteworthy that a greater proportion of men evaluated for suicidality disclosed a pandemic-related stressor. The overall picture may as well suggest that suicidality is likely to develop in the context of pre-existing mental conditions among women, and from pandemic-related strain among men, which is again in keeping with data relating to the first wave of the pandemic in Italy [

27].

Our study does not come without limitations. The lack of multiple-year comparison periods, the relatively small sample size, and the lack of information about completed suicides occurring in the time lapses investigated are among the major limitations. In the context of the above limitations, our study contributes to unravel the mid-term effects of COVID-19 pandemic on suicidality in Italy. The second wave of COVID-19 seemed to set a trend of return to pre-pandemic levels of suicidality among people referring to the EDs. Confirming previous findings from our research group on the the first wave of COVID-19, our data showed that suicidality arising during the pandemic may not relate to a pre-existing mental disorder. Nonetheless, the pathway through suicidality may differentiate women and men, and change across the epidemic phases. Further data on the long-term effects of COVID-19 will help to provide a comprehensive picture of how suicidality may develop and progress during and after large-scale health emergencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G. and F.G. and F.D. and G.M.; methodology, C.G. and G.M. and R.C.; formal analysis, R.C. and M.C.; investigation, F.D. and G.M. and F.B. and S.C.C.; data curation, F.B. and S.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, C.G. and M.C. and R.C.; supervision, B.D. and G.C. and P.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, and study procedures were approved by the Department of Psychiatry of the ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco of Milan as a relevant institution review board for low-risk studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in regard to this publication.

References

- WHO, IASP.

- Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, Suicide Attempts, and Suicidal Ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016 Mar 28;12(1):307–30.

- Bertolote, J.M.; Fleischmann, A. Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 181–5.

- Nordentoft, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Pedersen, C.B. Absolute Risk of Suicide After First Hospital Contact in Mental Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1058–1064. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Begum, N.; Saini, A.; Wang, S.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis – CORRIGENDUM. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30. [CrossRef]

- Kõlves K, Kõlves KE, De Leo D. Natural disasters and suicidal behaviours: A systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2013 Mar;146(1):1–14.

- Stratta, P.; Capanna, C.; Riccardi, I.; Carmassi, C.; Piccinni, A.; Dell'Osso, L.; Rossi, A. Suicidal intention and negative spiritual coping one year after the earthquake of L'Aquila (Italy). J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 1227–1231. [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Stratta, P.; Calderani, E.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Menichini, M.; Massimetti, E.; Rossi, A.; Dell’osso, L. Impact of Mood Spectrum Spirituality and Mysticism Symptoms on Suicidality in Earthquake Survivors with PTSD. J. Relig. Heal. 2015, 55, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Wasserman D, Iosue M, Wuestefeld A, Carli V. Adaptation of evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID -19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020 Oct 15;19(3):294–306.

- Leaune, E.; Samuel, M.; Oh, H.; Poulet, E.; Brunelin, J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic rapid review. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106264–106264. [CrossRef]

- Zortea, T.C.; Brenna, C.T.A.; Joyce, M.; McClelland, H.; Tippett, M.; Tran, M.M.; Arensman, E.; Corcoran, P.; Hatcher, S.; Heise, M.J.; et al. The Impact of Infectious Disease-Related Public Health Emergencies on Suicide, Suicidal Behavior, and Suicidal Thoughts. 2021, 42, 474–487. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, N.X. Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 3346. [CrossRef]

- Worldometers.

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 531–537. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: a Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [CrossRef]

- Nordt, C.; Warnke, I.; Seifritz, E.; Kawohl, W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: a longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000–11. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Almaghrebi, A.H. Risk factors for attempting suicide during the COVID-19 lockdown: Identification of the high-risk groups. J. Taibah Univ. Med Sci. 2021, 16, 605–611. [CrossRef]

- Gesi, C.; Cafaro, R.; Achilli, F.; Boscacci, M.; Cerioli, M.; Cirnigliaro, G.; Loupakis, F.; Di Maio, M.; Dell’osso, B. The relationship among posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, and suicidal ideation among Italian healthcare workers during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. CNS Spectrums 2023, 29, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Telles-Garcia, N.; Zahrli, T.; Aggarwal, G.; Bansal, S.; Richards, L.; Aggarwal, S. Suicide Attempt as the Presenting Symptom in a Patient with COVID-19: A Case Report from the United States. Case Rep. Psychiatry 2020, 2020, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, van Ommeren M, Barbui C, Tol WA. Psychological therapies for the treatment of mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries affected by humanitarian crises. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 Jul 5;2018(7).

- McAndrew, J.; O’leary, J.; Cotter, D.; Cannon, M.; MacHale, S.; Murphy, K.C.; Barry, H. Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions on psychiatry presentations to the emergency department of a large academic teaching hospital. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 38, 108–115. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Malathesh Barikar, C.; Mukherjee, A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102071. [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Heal. 2017, 152, 157–171. [CrossRef]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600.

- Miller, I.W.; Camargo, C.A.; Arias, S.A.; Sullivan, A.F.; Allen, M.H.; Goldstein, A.B.; Manton, A.P.; Espinola, J.A.; Jones, R.; Hasegawa, K.; et al. Suicide Prevention in an Emergency Department Population. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 563–570. [CrossRef]

- Claassen, C.A.; Larkin, G.L. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 352–353. [CrossRef]

- Gesi, C.; Grasso, F.; Dragogna, F.; Vercesi, M.; Paletta, S.; Politi, P.; Mencacci, C.; Cerveri, G. How Did COVID-19 Affect Suicidality? Data from a Multicentric Study in Lombardy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2410. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, J.M.; Marco, C.A.; Kluesner, N.H.; Schears, R.M.; Martin, D.R. Assessing psychiatric safety in suicidal emergency department patients. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2020, 1, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- International Business Machines Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Data Analyses; Version 27.0; IBM Corp: Armonk. NY. USA. 2021.

- Er, S.T.; Demir, E.; Sari, E. Suicide and economic uncertainty: New findings in a global setting. SSM - Popul. Heal. 2023, 22, 101387. [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, H.; Matsushima, M.; Midorikawa, H.; Aiba, M.; Okubo, R.; Tabuchi, T. Impact of loneliness on suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a cross-sectional online survey in Japan. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e063363. [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Moran, J.K.; Kippe, Y.D.; Schouler-Ocak, M.; Bermpohl, F.; Gutwinski, S.; Goldschmidt, T. Increase in presentations with new-onset psychiatric disorders in a psychiatric emergency department in Berlin, Germany during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic – a retrospective cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1240703. [CrossRef]

- Dubé, J.P.; Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Hewitt, P.L.; Stewart, S.H. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113998–113998. [CrossRef]

- A Mamun, M. Suicide and Suicidal Behaviors in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, ume 14, 695–704. [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Harrison, P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 8, 130–140. [CrossRef]

- Schou, T.M.; Joca, S.; Wegener, G.; Bay-Richter, C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 – A systematic review. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2021, 97, 328–348. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Gimeno, V.; Diestre, A.; Agustin-Alcain, M.; Portella, M.J.; de Diego-Adeliño, J.; Tiana, T.; Cheddi, N.; Distefano, A.; Dominguez, G.; Arias, M.; et al. Non-fatal suicide behaviours across phases in the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study in a Catalan cohort. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 348–358. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 229–238. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).