Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

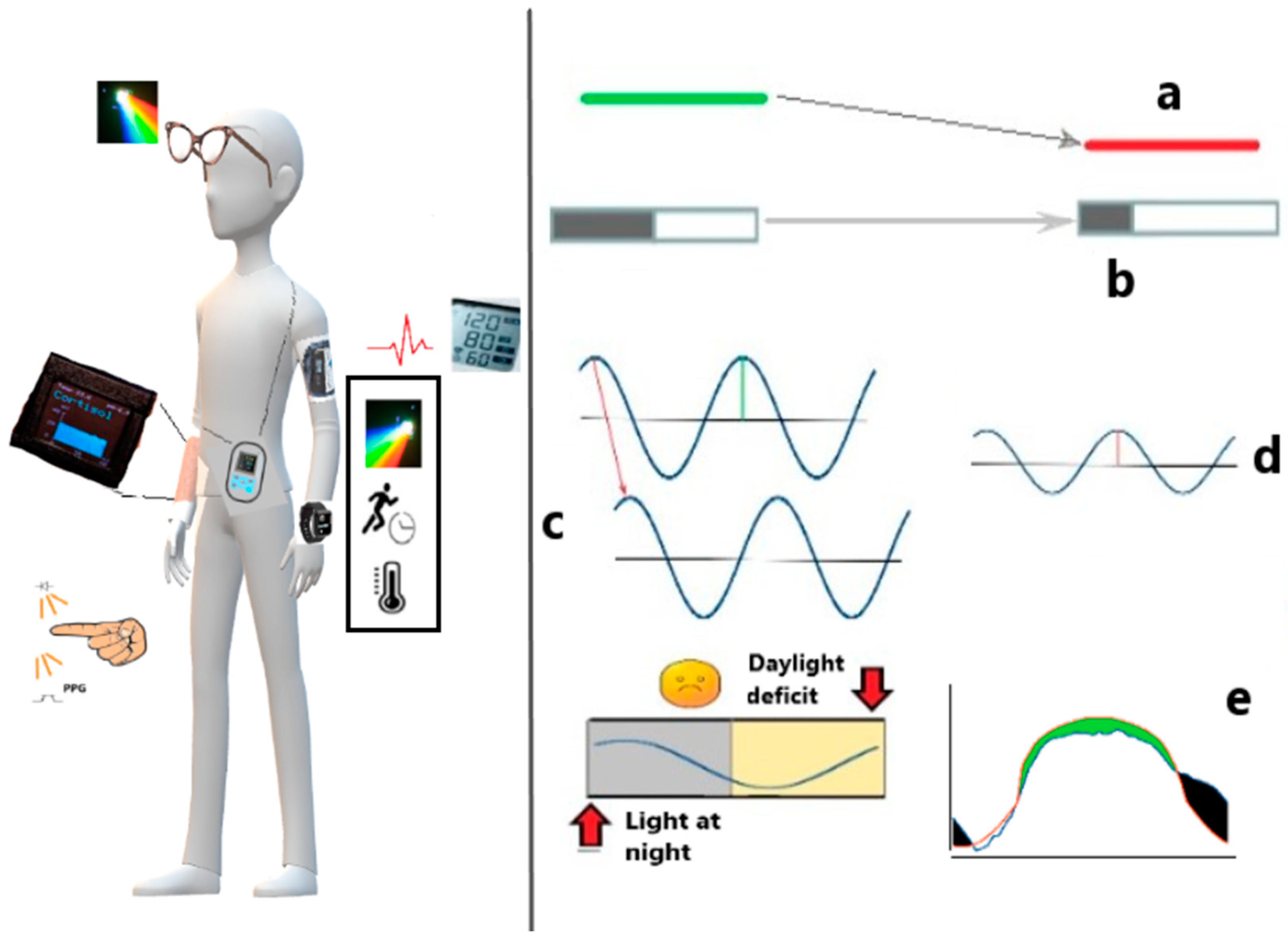

2. Actigraphy Features: Beyond Sleep

3. Overview of Actigraphic Health Markers

- IV (Intra-daily Variability) is calculated by the following formula:

3. Interpretation of Deviant Parameters

- Reduced Relative Amplitude of activity: lower daytime physical activity or light exposure (M10) that can be accompanied by higher nocturnal activity or light exposure (L5) is indicative of poorer sleep or light hygiene.

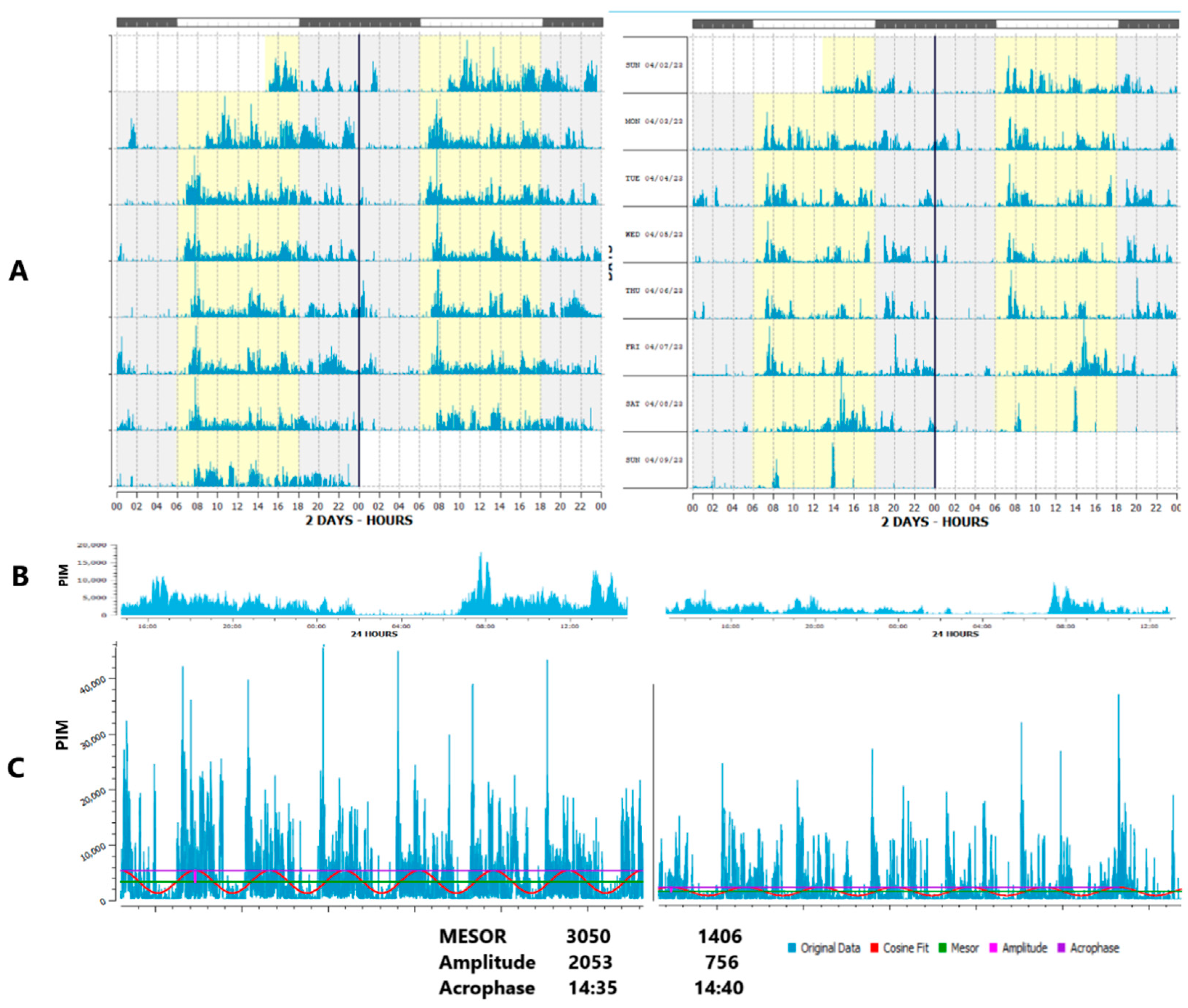

- Reduced circadian amplitude of activity: similarly relates to lower daytime but higher evening physical activity, Figure 2. In addition, the regularity of physical activity or light exposure patterns can be assessed by comparing the ratio of the amplitude assessed by separate 24-h cycles (A24) to the amplitude approximated over the entire monitoring period, e.g., week (Aw). When activity or light exposure occurs irregularly, Aw/A24 is reduced.

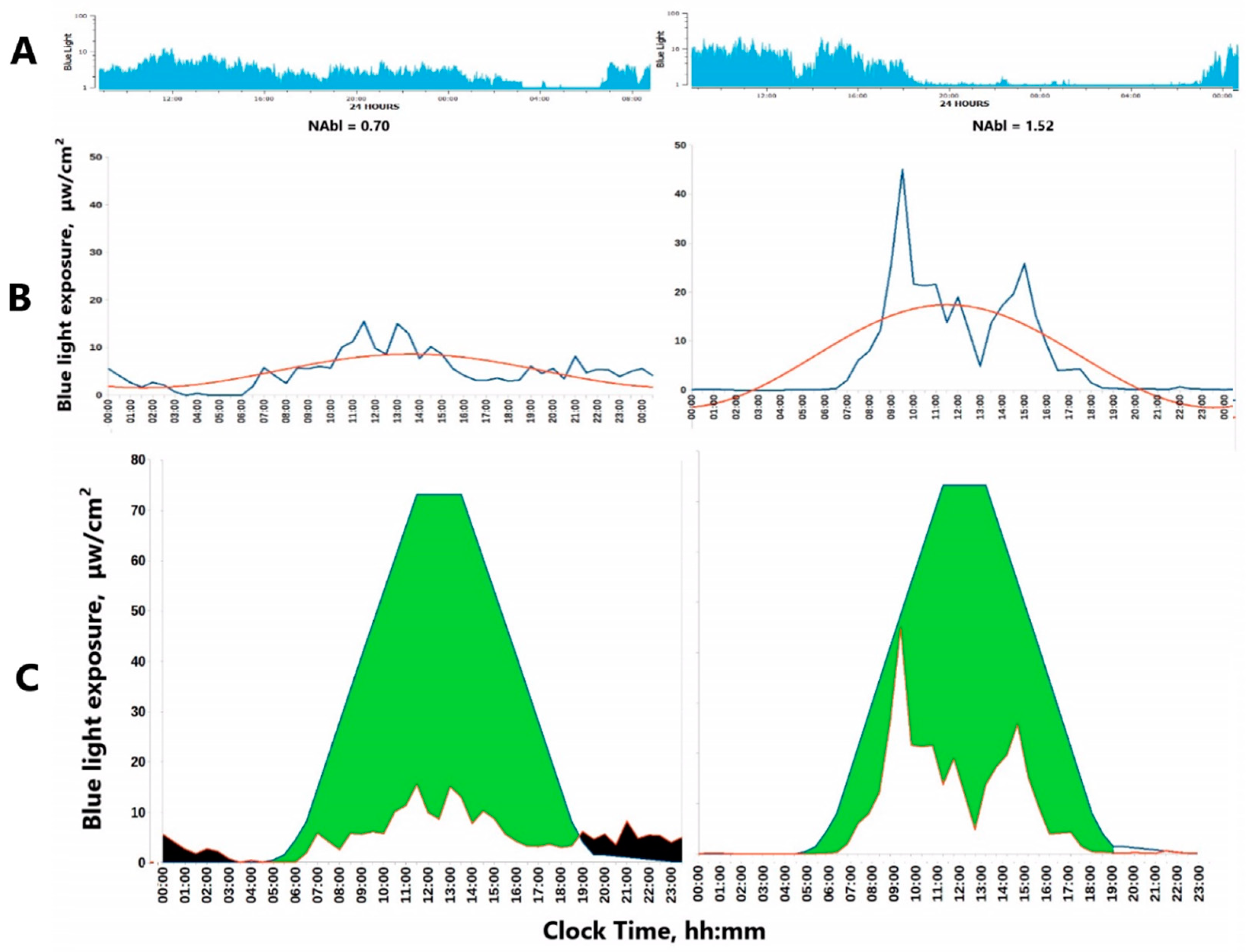

- The Normalized Amplitude (NA) can serve as a valuable metric to quantify both Physical Activity (PA) and light exposure (LE), Figure 3. It is particularly advantageous for LE, which often assumes extremely low or null values during the nighttime. Applying a log-transformation can effectively normalize these values, albeit at the cost of reducing daytime variations when LE is generally high.

- Phase deviations – both too late and too early maximal values may serve as health risk predictors. However, stronger evidence has accumulated to explain a phase delay since it is closely linked to and can be driven by a poor circadian light hygiene.

- Phase relationship – phase lag between light and activity (or sleep and melatonin) that can be predicted by wrist temperature (wT) provides more specific information, which, however, can strongly depend on the power of light signaling that varies profoundly depending on the local light environment and seasonal photoperiodism.

3.1. Faded Circadian Oscillation (Amplitude Decrease)

3.2. Phase Deviations

3.3. Fragmentation and Ultradian / Infradian Modifications

3.4. Misalignment (Intrinsic Desynchrony)

3.5. Social Jet Lag: Objective Characterization by Wearables

3.6. Composite Markers

4. Circadian Health Markers from Actigraphy

4.1. Circadian Markers of Morbidity and Mortality

4.1. Circadian Markers of Metabolic Health

5. Effects of Physical Activity on Health: Daily Amount, Regularity, Timing and Amplitude

6. Molecular Insights on Interaction Between Timed Physical Activity and Brain Health

6.1. Weekly Schedules

7. Wearables to Track Circadian Markers in Neurodegenerative Diseases

7.1. Intrinsically Disrupted Circadian Light Hygiene in Neurodegenerative Diseases

7.2. Boosting Brain and Metabolic Health by Clock Enhancing Strategies

8. Perspectives of Actigraphy-Compatible Wearable Technologies / Next-Generation Comprehensive Monitoring Systems

8.1. Perspective Options

8.2. Novel Sensors

8.3. Biochemical Analyses

8.4. Improving Light Exposure Monitoring and Analytics

8.5. Future of Light Dosimeters as Wearable-Friendly Add-Ons

| Circadian disruption marker | Typical deviation | Alternatives / Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Circadian rhythm measures | ||

| Amplitude | ↓ [11,12,36,38,56,61,62,66,67,68,74,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,132,138,139,147,148,149,150] |

↑ Transient elevation of amplitude due to jet lag, or shift-work, over-swinging functions such as blood pressure [111,113,302,303] |

| Phase | Delay → [61,74,120,125,129,133,139,147,148,149] |

Both delay → or advance ← (optimal phase position is determined by circadian clock precision [76,133,143,148] |

| Waveform (circadian robustness) | Reduced fitness of the curve to predictable best-fitted model [36,61,62,120] |

Flexibility rather than rigidity can be useful for adaptive needs, i.e., heart rate variability |

| Variability measures | ||

| Fragmentation and regularity (activity and sleep) |

IV (Intra-daily Variability)↑ IS (Inter-daily Stability) ↓ [38,51,61,62,69,120,122,123,132,147] |

Can be beneficial in certain cases such as short-term adaptation requiring high vigilance [38,51,61,62,69,120,122,123,132,147] Large inter- and intra-individual differences in the duration of sleep cycles throughout the night [46,47] |

| Spectral composition | Extra-circadian dissemination (ECD): ratio between circadian and non-circadian (ultradian / infradian) amplitudes ↓ [2,10,11,12,236] |

Some ultradian and infradian components are built-in and beneficial for health [47,306,307,308,309,310] |

| Alignment | Misalignment: disturbed phase relationship between circadian marker rhythms [55,56,75] |

Optimal phase angles may vary depending on genotype, age, light environment: season and latitude; and meal timing if peripheral rhythms’ phases are considered. |

| Composite markers (Area Under Curev), AUCs; Function-On-Scalar regression (FOSR), etc. | ↑ or ↓ [53,54,63,109,124,311,312] |

Optimal reference curves may depend on genotype, age, light environment: season and latitude; and meal timing if peripheral rhythms’ phases are considered. |

| Social Jet Lag | ↑ [99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106] |

Largely varies with age [103] and social obligations [313], may depend on the number of actual working days per week. All these factors can modify hazards of SJL for health. |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Otín C, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of health. Cell. 2021 Apr 1;184(7):1929-1939. [CrossRef]

- Agadzhanian NA, Gubin DG. Desinkhronoz: mekhanizmy razvitiia ot molekuliarno-geneticheskogo do organizmennogo urovnia [Desynchronization: mechanisms of development from molecular to systemic levels]. Usp Fiziol Nauk. 2004 Apr-Jun;35(2):57-72. Russian.

- Cornelissen G, Otsuka K. Chronobiology of aging: a mini-review. Gerontology 2017; 63 (2): 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Cederroth CR, Albrecht U, Bass J, Brown SA, Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen J, Gachon F, Green CB, Hastings MH, Helfrich-Förster C, Hogenesch JB, Lévi F, Loudon A, Lundkvist GB, Meijer JH, Rosbash M, Takahashi JS, Young M, Canlon B. Medicine in the Fourth Dimension. Cell Metab. 2019 Aug 6;30(2):238-250. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein AB, Knutson KL, Zee PC. Circadian disruption and human health. J Clin Invest. 2021 Oct 1;131(19):e148286. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Foster RG, Klerman EB. The circadian system, sleep, and the health/disease balance: a conceptual review. J Sleep Res. 2022 Aug;31(4):e13621. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D. Chronotherapeutic Approaches, in Chronobiology and Chronomedicine: From Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms to Whole Body Interdigitating Networks, ed. G. Cornelissen and T. Hirota, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024, vol. 23, ch. 21, pp. 536–577. [CrossRef]

- Allada R, Bass J. Circadian Mechanisms in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 11;384(6):550-561. [CrossRef]

- Kramer A, Lange T, Spies C, Finger AM, Berg D, Oster H. Foundations of circadian medicine. PLoS Biol. 2022 Mar 24;20(3):e3001567. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, DG. [Molecular basis of circadian rhythms and principles of circadian disruption]. Usp Fiziol Nauk. 2013 Oct-Dec;44(4):65-87. Russian.

- Gubin D, Cornelissen G, Weinert D, et al. Circadian disruption and Vascular Variability Disorders (VVD) — mechanisms linking aging, disease state and Arctic shift-work: applications for chronotherapy. World Heart J. 2013;5(4):285-306.

- Gubin DG, Weinert D, Bolotnova TV. Age-Dependent Changes of the Temporal Order--Causes and Treatment. Curr Aging Sci. 2016;9(1):14-25. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G. Cosinor-based rhythmometry. Theor Biol Med Model. 2014 Apr 11;11:16. [CrossRef]

- Weinert, D. and Gubin D. Chronobiological Study Designs. in Chronobiology and Chronomedicine From Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms to Whole Body Interdigitating Networks, ed. G. Cornelissen and T. Hirota, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024, vol. 23, ch. 22, pp. 579–609. [CrossRef]

- Usmani IM, Dijk DJ, Skeldon AC. Mathematical Analysis of Light-sensitivity Related Challenges in Assessment of the Intrinsic Period of the Human Circadian Pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 2024 Apr;39(2):166-182. [CrossRef]

- Kräuchi K, Cajochen C, Werth E, Wirz-Justice A. Functional link between distal vasodilation and sleep-onset latency? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000278(3):R741-8. [CrossRef]

- Kräuchi, K. The thermophysiological cascade leading to sleep initiation in relation to phase of entrainment. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(6):439-51. [CrossRef]

- Depner CM, Cheng PC, Devine JK, Khosla S, de Zambotti M, Robillard R, Vakulin A, Drummond SPA. Wearable technologies for developing sleep and circadian biomarkers: a summary of workshop discussions. Sleep. 2020 Feb 13;43(2):zsz254. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Kane M, Zhang Y, Sun W, Song Y, Dong S, Lin Q, Zhu Q, Jiang F, Zhao H. Circadian Rhythm Analysis Using Wearable Device Data: Novel Penalized Machine Learning Approach. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Oct 14;23(10):e18403. [CrossRef]

- Lujan MR, Perez-Pozuelo I, Grandner MA. Past, Present, and Future of Multisensory Wearable Technology to Monitor Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. Front Digit Health. 2021 Aug 16;3:721919. [CrossRef]

- Shandhi MMH, Wang WK, Dunn J. Taking the time for our bodies: How wearables can be used to assess circadian physiology. Cell Rep Methods. 2021 Aug 23;1(4):100067. [CrossRef]

- Tobin SY, Williams PG, Baron KG, Halliday TM, Depner CM. Challenges and Opportunities for Applying Wearable Technology to Sleep. Sleep Med Clin. 2021 Dec;16(4):607-618. [CrossRef]

- Lin C, Chen IM, Chuang HH, Wang ZW, Lin HH, Lin YH. Examining Human-Smartphone Interaction as a Proxy for Circadian Rhythm in Patients With Insomnia: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res. 2023 Dec 15;25:e48044. [CrossRef]

- de Zambotti M, Goldstein C, Cook J, Menghini L, Altini M, Cheng P, Robillard R. State of the science and recommendations for using wearable technology in sleep and circadian research. Sleep. 2024 Apr 12;47(4):zsad325. [CrossRef]

- Moorthy P, Weinert L, Schüttler C, Svensson L, Sedlmayr B, Müller J, Nagel T. Attributes, Methods, and Frameworks Used to Evaluate Wearables and Their Companion mHealth Apps: Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024 Apr 5;12:e52179. [CrossRef]

- Della Monica C, Ravindran KKG, Atzori G, Lambert DJ, Rodriguez T, Mahvash-Mohammadi S, Bartsch U, Skeldon AC, Wells K, Hampshire A, Nilforooshan R, Hassanin H, The Uk Dementia Research Institute Care Research Amp Technology Research Group, Revell VL, Dijk DJ. A Protocol for Evaluating Digital Technology for Monitoring Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Older People and People Living with Dementia in the Community. Clocks Sleep. 2024 Feb 29;6(1):129-155. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Ganglberger W, Panneerselvam E, Leone MJ, Quadri SA, Goparaju B, Tesh RA, Akeju O, Thomas RJ, Westover MB. Sleep staging from electrocardiography and respiration with deep learning. Sleep. 2020; 43(7):zsz306. [CrossRef]

- Kranzinger, S., Baron, S., Kranzinger, C., Heib, D., & Borgelt, C. Generalisability of sleep stage classification based on interbeat intervals: validating three machine learning approaches on self-recorded test data. Behaviormetrika, 2024. 51(1), 341-358. [CrossRef]

- Kripke DF, Mullaney DJ, Messin S, Wyborney VG. Wrist actigraphic measures of sleep and rhythms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978 May;44(5):674-6. [CrossRef]

- Wilde-Frenz J, Schulz H. Rate and distribution of body movements during sleep in humans. Percept Mot Skills. 1983 Feb;56(1):275-83. [CrossRef]

- Borbély, AA. New techniques for the analysis of the human sleep-wake cycle. Brain Dev. 1986;8(4):482-8. [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003 May 1;26(3):342-92. [CrossRef]

- Patterson MR, Nunes AAS, Gerstel D, Pilkar R, Guthrie T, Neishabouri A, Guo CC. 40 years of actigraphy in sleep medicine and current state of the art algorithms. NPJ Digit Med. 2023 Mar 24;6(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Lévi F, Zidani R, Misset JL. Randomised multicentre trial of chronotherapy with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinic acid in metastatic colorectal cancer. International Organization for Cancer Chronotherapy. Lancet. 1997; 350(9079):681-6. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G.; Dominguez-Vega, Z.T.; Laarhoven, H.S.; Brandsma, R.; Smit, M.; van der Stouwe, A.M.; Elting, J.W.J.; Maurits, N.M.; Rosmalen, J.G.; Tijssen, M.A. Similar association between objective and subjective symptoms in functional and organic tremor. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 64, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, Y., Blackwell T., Cawthon P.M., Ancoli-Israel S., Stone K.L., Yaffe K. Association of circadian abnormalities in older adults with an increased risk of developing Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1270–1278. [CrossRef]

- Feigl B, Lewis SJG, Burr LD, Schweitzer D, Gnyawali S, Vagenas D, Carter DD, Zele AJ. Efficacy of biologically-directed daylight therapy on sleep and circadian rhythm in Parkinson's disease: a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, active-controlled, phase 2 clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Feb 10;69:102474. [CrossRef]

- Winer JR, Lok R, Weed L, He Z, Poston KL, Mormino EC, Zeitzer JM. Impaired 24-h activity patterns are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Feb 14;16(1):35. [CrossRef]

- Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Ekelund U, Delisle Nyström C, Mora-Gonzalez J, Löf M, Labayen I, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB. Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations. Sports Med. 2017 Sep;47(9):1821-1845. [CrossRef]

- Danilenko KV, Stefani O, Voronin KA, Mezhakova MS, Petrov IM, Borisenkov MF, Markov AA, Gubin DG. Wearable Light-and-Motion Dataloggers for Sleep/Wake Research: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(22):11794. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell T, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Schneider JL, Surovec S, Johnson NL, Cauley JA, Stone KL; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Comparison of sleep parameters from actigraphy and polysomnography in older women: the SOF study. Sleep. 2008 Feb;31(2):283-91. [CrossRef]

- Quante M, Kaplan ER, Cailler M, Rueschman M, Wang R, Weng J, Taveras EM, Redline S. Actigraphy-based sleep estimation in adolescents and adults: a comparison with polysomnography using two scoring algorithms. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018 Jan 18;10:13-20. [CrossRef]

- Smith MT, McCrae CS, Cheung J, Martin JL, Harrod CG, Heald JL, Carden KA. Use of Actigraphy for the Evaluation of Sleep Disorders and Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and GRADE Assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Jul 15;14(7):1209-1230. [CrossRef]

- Fekedulegn D, Andrew ME, Shi M, Violanti JM, Knox S, Innes KE. Actigraphy-Based Assessment of Sleep Parameters. Ann Work Expo Health. 2020 Apr 30;64(4):350-367. [CrossRef]

- Lehrer HM, Yao Z, Krafty RT, Evans MA, Buysse DJ, Kravitz HM, Matthews KA, Gold EB, Harlow SD, Samuelsson LB, Hall MH. Comparing polysomnography, actigraphy, and sleep diary in the home environment: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Sleep Study. Sleep Adv. 2022 Feb 19;3(1):zpac001. [CrossRef]

- Winnebeck EC, Fischer D, Leise T, Roenneberg T. Dynamics and Ultradian Structure of Human Sleep in Real Life. Curr Biol. 2018 Jan 8;28(1):49-59.e5. [CrossRef]

- Cajochen C, Reichert CF, Münch M, Gabel V, Stefani O, Chellappa SL, Schmidt C. Ultradian sleep cycles: Frequency, duration, and associations with individual and environmental factors-A retrospective study. Sleep Health. 2024 Feb;10(1S):S52-S62. [CrossRef]

- Witting W, Kwa IH, Eikelenboom P, Mirmiran M, Swaab DF. Alterations in the circadian rest-activity rhythm in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1990 Mar 15;27(6):563-72. [CrossRef]

- Van Someren EJ, Swaab DF, Colenda CC, Cohen W, McCall WV, Rosenquist PB. Bright light therapy: improved sensitivity to its effects on rest-activity rhythms in Alzheimer patients by application of nonparametric methods. Chronobiol Int. 1999 Jul;16(4):505-18. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Tudela E, Martinez-Nicolas A, Campos M, Rol MÁ, Madrid JA. A new integrated variable based on thermometry, actimetry and body position (TAP) to evaluate circadian system status in humans. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010 Nov 11;6(11):e1000996. [CrossRef]

- Borisenkov M, Tserne T, Bakutova L, Gubin D. Actimetry-Derived 24 h Rest–Activity Rhythm Indices Applied to Predict MCTQ and PSQI. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(14):6888. [CrossRef]

- Danilevicz, I., van Hees, V., van der Heide, F. et al. Measures of fragmentation of rest activity patterns: mathematical properties and interpretability based on accelerometer real life data. BMC Med Res Methodol 24, 132. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gubin D, Danilenko K, Stefani O, Kolomeichuk S, Markov A, Petrov I, Voronin K, Mezhakova M, Borisenkov M, Shigabaeva A, et al. Blue Light and Temperature Actigraphy Measures Predicting Metabolic Health Are Linked to Melatonin Receptor Polymorphism. Biology. 2024; 13(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Spira AP, Liu F, Zipunnikov V, et al. Evaluating a Novel 24-Hour Rest/Activity rhythm marker of preclinical β-Amyloid deposition. Sleep. 2024;47(5):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell TL, Figueiro MG, Tranah GJ, Zeitzer JM, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Kado DM, Ensrud KE, Lane NE, Leng Y, Stone KL; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Group. Associations of 24-Hour Light Exposure and Activity Patterns and Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Decline in Older Men: The MrOS Sleep Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Oct 9;78(10):1834-1843. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Q, Durbin J, Bauer C, Yeung CHC, Figueiro MG. Alignment Between 24-h Light-Dark and Activity-Rest Rhythms Is Associated With Diabetes and Glucose Metabolism in a Nationally Representative Sample of American Adults. Diabetes Care. 2023 Dec 1;46(12):2171-2179. [CrossRef]

- Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Stern N, Bilu C, El-Osta A, Einat H, Kronfeld-Schor N. The Circadian Syndrome: is the Metabolic Syndrome and much more! J Intern Med. 2019 Aug;286(2):181-191. [CrossRef]

- Shi Z, Tuomilehto J, Kronfeld-Schor N, Alberti G, Stern N, El-Osta A, Chai Z, Bilu C, Einat H, Zimmet P. The Circadian Syndrome Is a Significant and Stronger Predictor for Cardiovascular Disease than the Metabolic Syndrome-The NHANES Survey during 2005-2016. Nutrients. 2022 Dec 14;14(24):5317. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker KM, Lutsey PL, Ogilvie RP, Pankow JS, Bertoni A, Michos ED, Punjabi N, Redline S. Associations between polysomnography and actigraphy-based sleep indices and glycemic control among those with and without type 2 diabetes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2018 Nov 1;41(11):zsy172. [CrossRef]

- Huang T, Redline S. Cross-sectional and Prospective Associations of Actigraphy-Assessed Sleep Regularity With Metabolic Abnormalities: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care. 2019 Aug;42(8):1422-1429. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Q, Qian J, Evans DS, Redline S, Lane NE, Ancoli-Israel S, Scheer FAJL, Stone K; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Group. Cross-sectional and Prospective Associations of Rest-Activity Rhythms With Metabolic Markers and Type 2 Diabetes in Older Men. Diabetes Care. 2020 Nov;43(11):2702-2712. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Q, Matthews CE, Playdon M, Bauer C. The association between rest-activity rhythms and glycemic markers: the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2014. Sleep. 2022 Feb 14;45(2):zsab291. [CrossRef]

- Kim M, Vu TH, Maas MB, Braun RI, Wolf MS, Roenneberg T, Daviglus ML, Reid KJ, Zee PC. Light at night in older age is associated with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Sleep. 2023 Mar 9;46(3):zsac130. [CrossRef]

- Wallace DA, Qiu X, Schwartz J, Huang T, Scheer FAJL, Redline S, Sofer T. Light exposure during sleep is bidirectionally associated with irregular sleep timing: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Pollut. 2024 Mar 1;344:123258. [CrossRef]

- Gubin GD, Weinert D. Bioritmy i vozrast [Biorhythms and age]. Usp Fiziol Nauk. 1991 Jan-Feb;22(1):77-96. Russian.

- Gubin D, Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Gubin G, Uezono K, Kawasaki T. The human blood pressure chronome: a biological gauge of aging. In Vivo. 1997 Nov-Dec;11(6):485-94.

- Abbott SM, Malkani RG, Zee PC. Circadian disruption and human health: A bidirectional relationship. Eur J Neurosci. 2020 Jan;51(1):567-583. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Wang X, Belsky DW, McCall WV, Liu Y, Su S. Blunted Rest-Activity Circadian Rhythm Is Associated With Increased Rate of Biological Aging: An Analysis of NHANES 2011-2014. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Mar 1;78(3):407-413. [CrossRef]

- Cribb L, Sha R, Yiallourou S, Grima NA, Cavuoto M, Baril AA, Pase MP. Sleep regularity and mortality: a prospective analysis in the UK Biobank. Elife. 2023 Nov 23;12:RP88359. [CrossRef]

- Najjar RP, Wolf L, Taillard J, Schlangen LJ, Salam A, Cajochen C, Gronfier C. Chronic artificial blue-enriched white light is an effective countermeasure to delayed circadian phase and neurobehavioral decrements. PLoS One. 2014 Jul 29;9(7):e102827. [CrossRef]

- Baron KG, Reid KJ. Circadian misalignment and health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;26(2):139-54. [CrossRef]

- Potter GD, Skene DJ, Arendt J, Cade JE, Grant PJ, Hardie LJ. Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Disruption: Causes, Metabolic Consequences, and Countermeasures. Endocr Rev. 2016 Dec;37(6):584-608. [CrossRef]

- Blume C, Garbazza C, Spitschan M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie (Berl). 2019 Sep;23(3):147-156. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Malishevskaya ТN, Astakhov YS, Astakhov SY, Cornelissen G, Kuznetsov VA, Weinert D. Progressive retinal ganglion cell loss in primary open-angle glaucoma is associated with temperature circadian rhythm phase delay and compromised sleep. Chronobiol Int. 2019 Apr;36(4):564-577. [CrossRef]

- Neroev V, Malishevskaya T, Weinert D, Astakhov S, Kolomeichuk S, Cornelissen G, Kabitskaya Y, Boiko E, Nemtsova I, Gubin D. Disruption of 24-Hour Rhythm in Intraocular Pressure Correlates with Retinal Ganglion Cell Loss in Glaucoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Dec 31;22(1):359. [CrossRef]

- Gubin D, Neroev V, Malishevskaya T, Cornelissen G, Astakhov SY, Kolomeichuk S, Yuzhakova N, Kabitskaya Y, Weinert D. Melatonin mitigates disrupted circadian rhythms, lowers intraocular pressure, and improves retinal ganglion cells function in glaucoma. J Pineal Res. 2021 May;70(4):e12730. [CrossRef]

- Gubin D, Weinert D. Melatonin, circadian rhythms and glaucoma: current perspective. Neural Regen Res. 2022 Aug;17(8):1759-1760. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D., Malishevskaya T., Weinert D., Zaharova E., Astakhov S., Cornelissen G. Circadian Disruption in Glaucoma: Causes, Consequences, and Countermeasures. Frontiers in Biosciences-Landmark. 2024. 11. accepted. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, U. 2012. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron 74, 246–260. [CrossRef]

- Foster, RG. Sleep, circadian rhythms and health. Interface Focus. 2020 Jun 6;10(3):20190098. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Kolomeichuk S N Weinert D. Circadian clock precision, health, and longevity. J. Chronomed. 2021;23 (1):3-15. [CrossRef]

- Dement W, Kleitman N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1957 Nov;9(4):673-90. [CrossRef]

- Levi F, Halberg F. Circaseptan (about-7-day) bioperiodicity--spontaneous and reactive--and the search for pacemakers. Ric Clin Lab. 1982 Apr-Jun;12(2):323-70. [CrossRef]

- Coskun A, Zarepour A, Zarrabi A. Physiological Rhythms and Biological Variation of Biomolecules: The Road to Personalized Laboratory Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 27;24(7):6275. [CrossRef]

- Madden KM, Feldman B. Weekly, Seasonal, and Geographic Patterns in Health Contemplations About Sundown Syndrome: An Ecological Correlational Study. JMIR Aging. 2019 May 28;2(1):e13302. [CrossRef]

- Seizer L, Cornélissen-Guillaume G, Schiepek GK, Chamson E, Bliem HR, Schubert C. About-Weekly Pattern in the Dynamic Complexity of a Healthy Subject's Cellular Immune Activity: A Biopsychosocial Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Jun 20;13:799214. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G., Hirota T. Quo Vadis. in Chronobiology and ChronomedicineFrom Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms to Whole Body Interdigitating Networks, ed. G. Cornelissen and T. Hirota, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024, vol. 23, ch. 24, pp. 648–664.

- Reinberg AE, Dejardin L, Smolensky MH, Touitou Y. Seven-day human biological rhythms: An expedition in search of their origin, synchronization, functional advantage, adaptive value and clinical relevance. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(2):162-191. [CrossRef]

- Cajochen C, Altanay-Ekici S, Münch M, Frey S, Knoblauch V, Wirz-Justice A. Evidence that the lunar cycle influences human sleep. Curr Biol. 2013 Aug 5;23(15):1485-8. [CrossRef]

- Reinberg A, Smolensky MH, Touitou Y. The full moon as a synchronizer of circa-monthly biological rhythms: Chronobiologic perspectives based on multidisciplinary naturalistic research. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(5):465-79. [CrossRef]

- Hartstein LE, Wright KP Jr, Akacem LD, Diniz Behn C, LeBourgeois MK. Evidence of circalunar rhythmicity in young children's evening melatonin levels. J Sleep Res. 2023 Apr;32(2):e13635. [CrossRef]

- Van Someren, EJ. More than a marker: interaction between the circadian regulation of temperature and sleep, age-related changes, and treatment possibilities. Chronobiol Int. 2000 May;17(3):313-54. [CrossRef]

- Gompper B, Bromundt V, Orgül S, Flammer J, Kräuchi K. Phase relationship between skin temperature and sleep-wake rhythms in women with vascular dysregulation and controls under real-life conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2010 Oct;27(9-10):1778-96. [CrossRef]

- Bonmati-Carrion MA, Middleton B, Revell V, Skene DJ, Rol MA, Madrid JA. Circadian phase assessment by ambulatory monitoring in humans: correlation with dim light melatonin onset. Chronobiol Int. 2014 Feb;31(1):37-51. [CrossRef]

- Reid, KJ. Assessment of Circadian Rhythms. Neurol Clin. 2019 Aug;37(3):505-526. [CrossRef]

- Stone JE, Phillips AJK, Ftouni S, Magee M, Howard M, Lockley SW, Sletten TL, Anderson C, Rajaratnam SMW, Postnova S. Generalizability of A Neural Network Model for Circadian Phase Prediction in Real-World Conditions. Sci Rep. 2019 Jul 29;9(1):11001. [CrossRef]

- Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1-2):497-509. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Pilz LK, Zerbini G, Winnebeck EC. Chronotype and Social Jetlag: A (Self-) Critical Review. Biology (Basel). 2019 Jul 12;8(3):54. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol. 2012 May 22;22(10):939-43. [CrossRef]

- Parsons MJ, Moffitt TE, Gregory AM, Goldman-Mellor S, Nolan PM, Poulton R, Caspi A. Social jetlag, obesity and metabolic disorder: investigation in a cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015 May;39(5):842-8. [CrossRef]

- Wong PM, Hasler BP, Kamarck TW, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Social Jetlag, Chronotype, and Cardiometabolic Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Dec;100(12):4612-20. [CrossRef]

- Caliandro R, Streng AA, van Kerkhof LWM, van der Horst GTJ, Chaves I. Social Jetlag and Related Risks for Human Health: A Timely Review. Nutrients. 2021 Dec 18;13(12):4543. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T. How can social jetlag affect health? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023 Jul;19(7):383-384. [CrossRef]

- Henderson SEM, Brady EM, Robertson N. Associations between social jetlag and mental health in young people: A systematic review. Chronobiol Int. 2019 Oct;36(10):1316-1333. [CrossRef]

- Islam Z, Hu H, Akter S, Kuwahara K, Kochi T, Eguchi M, Kurotani K, Nanri A, Kabe I, Mizoue T. Social jetlag is associated with an increased likelihood of having depressive symptoms among the Japanese working population: the Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study. Sleep. 2020 Jan 13;43(1):zsz204. [CrossRef]

- Qu Y, Li T, Xie Y, Tao S, Yang Y, Zou L, Zhang D, Zhai S, Tao F, Wu X. Association of chronotype, social jetlag, sleep duration and depressive symptoms in Chinese college students. J Affect Disord. 2023 Jan 1;320:735-741. [CrossRef]

- Zerbini G, Winnebeck EC, Merrow M. Weekly, seasonal, and chronotype-dependent variation of dim-light melatonin onset. J Pineal Res. 2021 Apr;70(3):e12723. [CrossRef]

- Brown TM, Brainard GC, Cajochen C, Czeisler CA, Hanifin JP, Lockley SW, Lucas RJ, Münch M, O'Hagan JB, Peirson SN, Price LLA, Roenneberg T, Schlangen LJM, Skene DJ, Spitschan M, Vetter C, Zee PC, Wright KP Jr. Recommendations for daytime, evening, and nighttime indoor light exposure to best support physiology, sleep, and wakefulness in healthy adults. PLoS Biol. 2022 Mar 17;20(3):e3001571. [CrossRef]

- Reid KJ, Santostasi G, Baron KG, Wilson J, Kang J, Zee PC. Timing and intensity of light correlate with body weight in adults. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 2;9(4):e92251. [CrossRef]

- Shim J, Fleisch E, Barata F. Circadian rhythm analysis using wearable-based accelerometry as a digital biomarker of aging and healthspan. NPJ Digit Med. 2024 Jun 4;7(1):146. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka K, Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Oehlerts G. Excessive circadian amplitude of blood pressure increases risk of ischaemic stroke and nephropathy. J Med Eng Technol. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):23-30. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen G, Halberg F, Bakken EE, Singh RB, Otsuka K, Tomlinson B, Delcourt A, Toussaint G, Bathina S, Schwartzkopff O, Wang ZR, Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Pantaleoni GC, Jozsa R, Delmore PA, Nolley E. 100 or 30 years after Janeway or Bartter, Healthwatch helps avoid "flying blind". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2004; 58 (Suppl 1): S69-S86.

- Cornélissen G, Delcourt A, Toussaint G, Otsuka K, Watanabe Y, Siegelova J, Fiser B, Dusek J, Homolka P, Singh RB, Kumar A, Singh RK, Sanchez S, Gonzalez C, Holley D, Sundaram B, Zhao Z, Tomlinson B, Fok B, Zeman M, Dulkova K, Halberg F. Opportunity of detecting pre-hypertension: worldwide data on blood pressure overswinging. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005 Oct;59 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S152-7. [CrossRef]

- Halberg F, Powell D, Otsuka K, Watanabe Y, Beaty LA, Rosch P, Czaplicki J, Hillman D, Schwartzkopff O, Cornelissen G. Diagnosing vascular variability anomalies, not only MESOR-hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013; 305: H279-H294.

- Jagannath A, Taylor L, Wakaf Z, Vasudevan SR, Foster RG. The genetics of circadian rhythms, sleep and health. Hum Mol Genet. 2017 Oct 1;26(R2):R128-R138. [CrossRef]

- Bacalini MG, Palombo F, Garagnani P, Giuliani C, Fiorini C, Caporali L, Stanzani Maserati M, Capellari S, Romagnoli M, De Fanti S, Benussi L, Binetti G, Ghidoni R, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, Arcaro M, Bonanni E, Siciliano G, Maestri M, Guarnieri B; Italian Multicentric Group on clock genes, actigraphy in AD; Martucci M, Monti D, Carelli V, Franceschi C, La Morgia C, Santoro A. Association of rs3027178 polymorphism in the circadian clock gene PER1 with susceptibility to Alzheimer's disease and longevity in an Italian population. Geroscience. 2022 Apr;44(2):881-896. [CrossRef]

- Gubin D, Neroev V, Malishevskaya T, Kolomeichuk S, Cornelissen G, Yuzhakova N, Vlasova A, Weinert D. Depression scores are associated with retinal ganglion cells loss. J Affect Disord. 2023 Jul 15;333:290-296. [CrossRef]

- Lyall LM, Wyse CA, Graham N, Ferguson A, Lyall DM, Cullen B, Celis Morales CA, Biello SM, Mackay D, Ward J, Strawbridge RJ, Gill JMR, Bailey MES, Pell JP, Smith DJ. Association of disrupted circadian rhythmicity with mood disorders, subjective wellbeing, and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study of 91 105 participants from the UK Biobank. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Jun;5(6):507-514. [CrossRef]

- Feng H, Yang L, Ai S, Liu Y, Zhang W, Lei B, Chen J, Liu Y, Chan JWY, Chan NY, Tan X, Wang N, Benedict C, Jia F, Wing YK, Zhang J. Association between accelerometer-measured amplitude of rest-activity rhythm and future health risk: a prospective cohort study of the UK Biobank. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023 May;4(5):e200-e210. [CrossRef]

- Cai R, Gao L, Gao C, Yu L, Zheng X, Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Hu K, Li P. Circadian disturbances and frailty risk in older adults. Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 16;14(1):7219. [CrossRef]

- Brooks TG, Lahens NF, Grant GR, Sheline YI, FitzGerald GA, Skarke C. Diurnal rhythms of wrist temperature are associated with future disease risk in the UK Biobank. Nat Commun. 2023 Aug 24;14(1):5172. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Su S, McCall WV, Isales C, Snieder H, Wang X. Rest-activity circadian rhythm and impaired glucose tolerance in adults: an analysis of NHANES 2011-2014. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022 Mar;10(2):e002632. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Su S, McCall WV, Wang X. Blunted rest-activity rhythm is associated with increased white blood-cell-based inflammatory markers in adults: an analysis from NHANES 2011-2014. Chronobiol Int. 2022 Jun;39(6):895-902. [CrossRef]

- Shim J, Fleisch E, Barata F. Wearable-based accelerometer activity profile as digital biomarker of inflammation, biological age, and mortality using hierarchical clustering analysis in NHANES 2011-2014. Sci Rep. 2023 Jun 8;13(1):9326. [CrossRef]

- Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Stone KL; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Circadian activity rhythms and mortality: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Feb;58(2):282-91. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. Circadian rhythms and exercise - re-setting the clock in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019 Apr;15(4):197-206. [CrossRef]

- Martin RA, Esser KA. Time for Exercise? Exercise and Its Influence on the Skeletal Muscle Clock. J Biol Rhythms. 2022 Dec;37(6):579-592. [CrossRef]

- Martin RA, Viggars MR, Esser KA. Metabolism and exercise: the skeletal muscle clock takes centre stage. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023 May;19(5):272-284. [CrossRef]

- Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Yaffe K; SOF Research Group. Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann Neurol. 2011 Nov;70(5):722-32. [CrossRef]

- Rogers-Soeder TS, Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Paudel M, Barrett-Connor E, LeBlanc E, Stone K, Lane NE, Tranah G; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Research Group. Rest-Activity Rhythms and Cognitive Decline in Older Men: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2136-2143. [CrossRef]

- Harada K, Masumoto K, Okada S. Physical Activity Components that Determine Daily Life Satisfaction Among Older Adults: An Intensive Longitudinal Diary Study. Int J Behav Med. 2024 Mar 19. [CrossRef]

- Tai Y, Obayashi K, Yamagami Y, Saeki K. Association between circadian skin temperature rhythms and actigraphic sleep measures in real-life settings. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023 Jul 1;19(7):1281-1292. [CrossRef]

- Saint-Maurice PF, Freeman JR, Russ D, Almeida JS, Shams-White MM, Patel S, Wolff-Hughes DL, Watts EL, Loftfield E, Hong HG, Moore SC, Matthews CE. Associations between actigraphy-measured sleep duration, continuity, and timing with mortality in the UK Biobank. Sleep. 2024 Mar 11;47(3):zsad312. [CrossRef]

- Nikbakhtian S, Reed AB, Obika BD, Morelli D, Cunningham AC, Aral M, Plans D. Accelerometer-derived sleep onset timing and cardiovascular disease incidence: a UK Biobank cohort study. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2021 Nov 9;2(4):658-666. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Juda M, Kantermann T, Allebrandt K, Gordijn M, Merrow M. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med Rev. 2007 Dec;11(6):429-38. [CrossRef]

- Fischer D, Lombardi DA, Marucci-Wellman H, Roenneberg T. Chronotypes in the US - Influence of age and sex. PLoS One. 2017 Jun 21;12(6):e0178782. [CrossRef]

- Borisenkov, M., Gubin, D., Kolomieichuk S. On the issue of adaptive fitness of chronotypes in high latitudes. Biological Rhythm Research, 2024. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Nelaeva AA, Uzhakova AE, Hasanova YV, Cornelissen G, Weinert D. Disrupted circadian rhythms of body temperature, heart rate and fasting blood glucose in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(8):1136-1148. [CrossRef]

- Windred DP, Burns AC, Rutter MK, Ching Yeung CH, Lane JM, Xiao Q, Saxena R, Cain SW, Phillips AJK. Personal light exposure patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes: analysis of 13 million hours of light sensor data and 670,000 person-years of prospective observation. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;42:100943. [CrossRef]

- Rao F, Xue T. Circadian-independent light regulation of mammalian metabolism. Nat Metab. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Weinert D, Gubin D. The Impact of Physical Activity on the Circadian System: Benefits for Health, Performance and Wellbeing. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(18):9220. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano C, Garitaonaindia MT, Salmerón D, Pérez-Sanz F, Tchio C, Picinato MC, de Medina FS, Luján J, Scheer FAJL, Saxena R, Martínez-Augustin O, Garaulet M. Melatonin decreases human adipose tissue insulin sensitivity. J Pineal Res. 2024; 76(5):e12965. [CrossRef]

- Weinert D, Waterhouse J. The circadian rhythm of core temperature: effects of physical activity and aging. Physiol Behav. 2007 Feb 28;90(2-3):246-56. [CrossRef]

- Tranel HR, Schroder EA, England J, Black WS, Bush H, Hughes ME, Esser KA, Clasey JL. Physical activity, and not fat mass is a primary predictor of circadian parameters in young men. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32(6):832-41. [CrossRef]

- Dupont Rocher S, Bessot N, Sesboüé B, Bulla J, Davenne D. Circadian Characteristics of Older Adults and Aerobic Capacity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Jun;71(6):817-22. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Weinert D, Rybina SV, Danilova LA, Solovieva SV, Durov AM, Prokopiev NY, Ushakov PA. Activity, sleep and ambient light have a different impact on circadian blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(5):632-649. [CrossRef]

- Hori H, Koga N, Hidese S, Nagashima A, Kim Y, Higuchi T, Kunugi H. 24-h activity rhythm and sleep in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Jun;77:27-34. [CrossRef]

- Merikanto I, Partonen T, Paunio T, Castaneda AE, Marttunen M, Urrila AS. Advanced phases and reduced amplitudes are suggested to characterize the daily rest-activity cycles in depressed adolescent boys. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(7):967-976. [CrossRef]

- Minaeva O, Booij SH, Lamers F, Antypa N, Schoevers RA, Wichers M, Riese H. Level and timing of physical activity during normal daily life in depressed and non-depressed individuals. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 30;10(1):259. [CrossRef]

- Roveda E, Montaruli A, Galasso L, Pesenti C, Bruno E, Pasanisi P, Cortellini M, Rampichini S, Erzegovesi S, Caumo A, Esposito F. Rest-activity circadian rhythm and sleep quality in patients with binge eating disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2018 Feb;35(2):198-207. [CrossRef]

- Borisenkov MF, Tserne TA, Bakutova LA, Gubin DG. Food addiction and emotional eating are associated with intradaily rest-activity rhythm variability. Eat Weight Disord. 2022 Dec;27(8):3309-3316. [CrossRef]

- Healy KL, Morris AR, Liu AC. Circadian Synchrony: Sleep, Nutrition, and Physical Activity. Front Netw Physiol. 2021 Oct;1:732243. [CrossRef]

- Shen B, Ma C, Wu G, Liu H, Chen L, Yang G. Effects of exercise on circadian rhythms in humans. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Oct 11;14:1282357. [CrossRef]

- Weinert D, Schöttner K, Müller L, Wienke A. (2016). Intensive voluntary wheel running may restore circadian activity rhythms and improves the impaired cognitive performance of arrhythmic Djungarian hamsters. Chronobiol Int 33:1161-1170. [CrossRef]

- Weinert D, Weinandy R, Gattermann R. (2007). Photic and non-photic effects on the daily activity pattern of Mongolian gerbils. Physiol Behav 90:325-333. [CrossRef]

- Müller L, Fritzsche P, Weinert D. (2015). Novel object recognition of Djungarian hamsters depends on circadian time and rhythmic phenotype. Chronobiol Int 32:458-467. [CrossRef]

- Müller L, Weinert D. (2016). Individual recognition of social rank and social memory performance depends on a functional circadian system. Behav Processes 132:85-93. [CrossRef]

- Seo DY, Lee S, Kim N, Ko KS, Rhee BD, Park BJ, Han J. Morning and evening exercise. Integr Med Res. 2013 Dec;2(4):139-144. [CrossRef]

- Smith PJ, Merwin RM. The Role of Exercise in Management of Mental Health Disorders: An Integrative Review. Annu Rev Med. 2021 Jan 27;72:45-62. [CrossRef]

- Youngstedt SD, Elliott JA, Kripke DF. Human circadian phase-response curves for exercise. J Physiol. 2019 Apr;597(8):2253-2268. [CrossRef]

- Liang YY, Feng H, Chen Y, Jin X, Xue H, Zhou M, Ma H, Ai S, Wing YK, Geng Q, Zhang J. Joint association of physical activity and sleep duration with risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study using accelerometry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023 Jul 12;30(9):832-843. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Chen Y, Feng H, Zhou M, Chan JWY, Liu Y, Kong APS, Tan X, Wing YK, Liang YY, Zhang J. Association of accelerometer-measured sleep duration and different intensities of physical activity with incident type 2 diabetes in a population-based cohort study. J Sport Health Sci. 2024 Mar;13(2):222-232. [CrossRef]

- Ahn HJ, Choi EK, Rhee TM, Choi J, Lee KY, Kwon S, Lee SR, Oh S, Lip GYH. Accelerometer-derived physical activity and the risk of death, heart failure, and stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a prospective study from UK Biobank. Br J Sports Med. 2024 Apr 2;58(8):427-434. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis E, Ahmadi MN, Friedenreich CM, Blodgett JM, Koster A, Holtermann A, Atkin A, Rangul V, Sherar LB, Teixeira-Pinto A, Ekelund U, Lee IM, Hamer M. Vigorous Intermittent Lifestyle Physical Activity and Cancer Incidence Among Nonexercising Adults: The UK Biobank Accelerometry Study. JAMA Oncol. 2023 Sep 1;9(9):1255-1259. [CrossRef]

- Khurshid S, Al-Alusi MA, Churchill TW, Guseh JS, Ellinor PT. Accelerometer-Derived "Weekend Warrior" Physical Activity and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA. 2023 Jul 18;330(3):247-252. [CrossRef]

- Lin F, Lin Y, Chen L, Huang T, Lin T, He J, Lu X, Chen X, Wang Y, Ye Q, Cai G. Association of physical activity pattern and risk of Parkinson's disease. NPJ Digit Med. 2024 May 23;7(1):137. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan R, Doherty A, Smith-Byrne K, Rahimi K, Bennett D, Woodward M, Walmsley R, Dwyer T. Accelerometer measured physical activity and the incidence of cardiovascular disease: Evidence from the UK Biobank cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021 Jan 12;18(1):e1003487. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003487. Erratum in: PLoS Med. 2021 Sep 29;18(9):e1003809. [CrossRef]

- Shreves AH, Small SR, Travis RC, Matthews CE, Doherty A. Dose-response of accelerometer-measured physical activity, step count, and cancer risk in the UK Biobank: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2023 Nov;402 Suppl 1:S83. [CrossRef]

- Watts EL, Saint-Maurice PF, Doherty A, Fensom GK, Freeman JR, Gorzelitz JS, Jin D, McClain KM, Papier K, Patel S, Shiroma EJ, Moore SC, Matthews CE. Association of Accelerometer-Measured Physical Activity Level With Risks of Hospitalization for 25 Common Health Conditions in UK Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Feb 1;6(2):e2256186. [CrossRef]

- Hooker SP, Diaz KM, Blair SN, Colabianchi N, Hutto B, McDonnell MN, Vena JE, Howard VJ. Association of Accelerometer-Measured Sedentary Time and Physical Activity With Risk of Stroke Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jun 1;5(6):e2215385. [CrossRef]

- Mandolesi L, Polverino A, Montuori S, Foti F, Ferraioli G, Sorrentino P, Sorrentino G. Effects of Physical Exercise on Cognitive Functioning and Wellbeing: Biological and Psychological Benefits. Front Psychol. 2018 Apr 27;9:509. [CrossRef]

- Thapa N, Kim B, Yang JG, Park HJ, Jang M, Son HE, Kim GM, Park H. The Relationship between Chronotype, Physical Activity and the Estimated Risk of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 24;17(10):3701. [CrossRef]

- Soldan A, Alfini A, Pettigrew C, Faria A, Hou X, Lim C, Lu H, Spira AP, Zipunnikov V, Albert M; BIOCARD Research Team. Actigraphy-estimated physical activity is associated with functional and structural brain connectivity among older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2022 Aug;116:32-40. [CrossRef]

- Mahindru A, Patil P, Agrawal V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus. 2023 Jan 7;15(1):e33475. [CrossRef]

- Feng H, Yang L, Liang YY, Ai S, Liu Y, Liu Y, Jin X, Lei B, Wang J, Zheng N, Chen X, Chan JWY, Sum RKW, Chan NY, Tan X, Benedict C, Wing YK, Zhang J. Associations of timing of physical activity with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort study. Nat Commun. 2023 Feb 18;14(1):930. [CrossRef]

- Brito LC, Marin TC, Azevêdo L, Rosa-Silva JM, Shea SA, Thosar SS. Chronobiology of Exercise: Evaluating the Best Time to Exercise for Greater Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits. Compr Physiol. 2022 Jun 29;12(3):3621-3639. [CrossRef]

- Tian C, Bürki C, Westerman KE, Patel CJ. Association between timing and consistency of physical activity and type 2 diabetes: a cohort study on participants of the UK Biobank. Diabetologia. 2023 Dec;66(12):2275-2282. [CrossRef]

- Homolka P, Cornelissen G, Homolka A, Siegelova J, Halberg F. Exercise-associated transient circadian hypertension (CHAT)? Abstract, III International Conference, Civilization diseases in the spirit of V.I. Vernadsky, People's Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Oct. 10-12, 2005, pp. 419–421.

- Bonekamp NE, May AM, Halle M, Dorresteijn JAN, van der Meer MG, Ruigrok YM, de Borst GJ, Geleijnse JM, Visseren FLJ, Koopal C. Physical exercise volume, type, and intensity and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease: a mediation analysis. Eur Heart J Open. 2023 Jun 13;3(3):oead057. [CrossRef]

- Franczyk B, Gluba-Brzózka A, Ciałkowska-Rysz A, Ławiński J, Rysz J. The Impact of Aerobic Exercise on HDL Quantity and Quality: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 28;24(5):4653. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Liu S, Wang K, Zhang T, Yin L, Liang J, Yang Y, Luo J. Time-Dependent Effects of Physical Activity on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adults: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Oct 30;19(21):14194. [CrossRef]

- Schock S, Hakim A. The Physiological and Molecular Links Between Physical Activity and Brain Health: A Review. Neurosci Insights. 2023 Aug 17;18:26331055231191523. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Liu J, Cui M, Chai H, Chen L, Zhang T, Mi J, Guan H, Zhao L. Moderate-intensity continuous training has time-specific effects on the lipid metabolism of adolescents. J Transl Int Med. 2023 Mar 9;11(1):57-69. [CrossRef]

- Kent BA, Rahman SA, St Hilaire MA, Grant LK, Rüger M, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW. Circadian lipid and hepatic protein rhythms shift with a phase response curve different than melatonin. Nat Commun. 2022 Feb 3;13(1):681. 10.1038/s41467-022-28308-6. Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2022 Apr 20;13(1):2241. [CrossRef]

- Gubin D, Neroev V, Malishevskaya T, Kolomeichuk S, Weinert D, Yuzhakova N, Nelaeva A, Filippova Y, Cornelissen G. Daytime Lipid Metabolism Modulated by CLOCK Gene Is Linked to Retinal Ganglion Cells Damage in Glaucoma. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(13):6374. [CrossRef]

- Wei W, Raun SH, Long JZ. Molecular Insights From Multiomics Studies of Physical Activity. Diabetes. 2024 Feb 1;73(2):162-168. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Nakagawa S. Physical activity for cognitive health promotion: An overview of the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2023 Apr;86:101868. [CrossRef]

- Phillips CM, Dillon CB, Perry IJ. Does replacing sedentary behaviour with light or moderate to vigorous physical activity modulate inflammatory status in adults? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Oct 11;14(1):138. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CL, Ukropec J, Ukropcová B, Pai MC. An acute bout of aerobic or strength exercise specifically modifies circulating exerkine levels and neurocognitive functions in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage Clin. 2017 Oct 31;17:272-284. [CrossRef]

- Li VL, He Y, Contrepois K, Liu H, Kim JT, Wiggenhorn AL, Tanzo JT, Tung AS, Lyu X, Zushin PH, Jansen RS, Michael B, Loh KY, Yang AC, Carl CS, Voldstedlund CT, Wei W, Terrell SM, Moeller BC, Arthur RM, Wallis GA, van de Wetering K, Stahl A, Kiens B, Richter EA, Banik SM, Snyder MP, Xu Y, Long JZ. An exercise-inducible metabolite that suppresses feeding and obesity. Nature. 2022 Jun;606(7915):785-790. [CrossRef]

- Okauchi H, Hashimoto C, Nakao R, Oishi K. Timing of food intake is more potent than habitual voluntary exercise to prevent diet-induced obesity in mice. Chronobiol Int. 2019 Jan;36(1):57-74. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Q, Lu C, Qian R. The circadian clock regulates metabolic responses to physical exercise. Chronobiol Int. 2022 Jul;39(7):907-917. [CrossRef]

- Stanford KI, Lynes MD, Takahashi H, Baer LA, Arts PJ, May FJ, Lehnig AC, Middelbeek RJW, Richard JJ, So K, Chen EY, Gao F, Narain NR, Distefano G, Shettigar VK, Hirshman MF, Ziolo MT, Kiebish MA, Tseng YH, Coen PM, Goodyear LJ. 12,13-diHOME: An Exercise-Induced Lipokine that Increases Skeletal Muscle Fatty Acid Uptake. Cell Metab. 2018 May 1;27(5):1111-1120.e3. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Vamvini M, Nigro P, Ho LL, Galani K, Alvarez M, Tanigawa Y, Renfro A, Carbone NP, Laakso M, Agudelo LZ, Pajukanta P, Hirshman MF, Middelbeek RJW, Grove K, Goodyear LJ, Kellis M. Single-cell dissection of the obesity-exercise axis in adipose-muscle tissues implies a critical role for mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Metab. 2022 Oct 4;34(10):1578-1593.e6. [CrossRef]

- Rey G, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Wulund L, Milev NB, Stangherlin A, Ansel-Bollepalli L, Velagapudi V, O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Regulates the Circadian Clock. Cell Metab. 2016 Sep 13;24(3):462-473. [CrossRef]

- Fagiani F, Di Marino D, Romagnoli A, Travelli C, Voltan D, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Racchi M, Govoni S, Lanni C. Molecular regulations of circadian rhythm and implications for physiology and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Feb 8;7(1):41. [CrossRef]

- Esteras N, Blacker TS, Zherebtsov EA, Stelmashuk OA, Zhang Y, Wigley WC, Duchen MR, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. Nrf2 regulates glucose uptake and metabolism in neurons and astrocytes. Redox Biol. 2023 Jun;62:102672. [CrossRef]

- Wible RS, Ramanathan C, Sutter CH, Olesen KM, Kensler TW, Liu AC, Sutter TR. NRF2 regulates core and stabilizing circadian clock loops, coupling redox and timekeeping in Mus musculus. Elife. 2018 Feb 26;7:e31656. [CrossRef]

- Fasipe B, Laher I. Nrf2 modulates the benefits of evening exercise in type 2 diabetes. Sports Med Health Sci. 2023 Sep 9;5(4):251-258. [CrossRef]

- Thomas AW, Davies NA, Moir H, Watkeys L, Ruffino JS, Isa SA, Butcher LR, Hughes MG, Morris K, Webb R. Exercise-associated generation of PPARγ ligands activates PPARγ signaling events and upregulates genes related to lipid metabolism. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2012 Mar;112(5):806-15. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Yang G. PPARs Integrate the Mammalian Clock and Energy Metabolism. PPAR Res. 2014;2014:653017. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, Bookout AL, He W, Straume M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):801-10. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Ma S, Cai Y, Wang S, Ren J, Yang Y, Ping J, Wang X, Zhang Y, Yan H, Li W, Esteban CR, Yu Y, Liu F, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Zhang W, Qu J, Liu GH. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas of exercise-induced anti-inflammatory and geroprotective effects across the body. Innovation (Camb). 2023 Jan 5;4(1):100380. [CrossRef]

- Matei D, Trofin D, Iordan DA, Onu I, Condurache I, Ionite C, Buculei I. The Endocannabinoid System and Physical Exercise. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 19;24(3):1989. [CrossRef]

- Xue H, Zou Y, Yang Q, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Wei X, Zhou J, Tao XL, Zhang C, Xia Y, Luo F. The association between different physical activity (PA) patterns and cardiometabolic index (CMI) in US adult population from NHANES (2007-2016). Heliyon. 2024 Mar 26;10(7):e28792. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Zhang D, Wei Z, Liu P, Yang Q, Zhang L, Zhang J, Zhang C, Xue H, Xie Z, Luo F. Whether weekend warriors (WWs) achieve equivalent benefits in lipid accumulation products (LAP) reduction as other leisure-time physical activity patterns? -Results from a population-based analysis of NHANES 2007-2018. BMC Public Health. 2024 Jun 9;24(1):1550. [CrossRef]

- Nebe S, Reutter M, Baker DH, Bölte J, Domes G, Gamer M, Gärtner A, Gießing C, Gurr C, Hilger K, Jawinski P, Kulke L, Lischke A, Markett S, Meier M, Merz CJ, Popov T, Puhlmann LMC, Quintana DS, Schäfer T, Schubert AL, Sperl MFJ, Vehlen A, Lonsdorf TB, Feld GB. Enhancing precision in human neuroscience. Elife. 2023 Aug 9;12:e85980. [CrossRef]

- Muddapu VR, Dharshini SAP, Chakravarthy VS, Gromiha MM. Neurodegenerative Diseases - Is Metabolic Deficiency the Root Cause? Front Neurosci. 2020 Mar 31;14:213. [CrossRef]

- Procaccini C, Santopaolo M, Faicchia D, Colamatteo A, Formisano L, de Candia P, Galgani M, De Rosa V, Matarese G. Role of metabolism in neurodegenerative disorders. Metabolism. 2016 Sep;65(9):1376-90. [CrossRef]

- Breasail MÓ, Biswas B, Smith MD, Mazhar MKA, Tenison E, Cullen A, Lithander FE, Roudaut A, Henderson EJ. Wearable GPS and Accelerometer Technologies for Monitoring Mobility and Physical Activity in Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel). 2021 Dec 10;21(24):8261. [CrossRef]

- Cote AC, Phelps RJ, Kabiri NS, Bhangu JS, Thomas KK. Evaluation of Wearable Technology in Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Jan 11;7:501104. [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer-Streit B, Forneris CA, Morgan LC, Van Noord MG, Gaynes BN, Greenblatt A, Wipplinger J, Lux LJ, Winkler D, Gartlehner G. Light therapy for preventing seasonal affective disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 18;3(3):CD011269. [CrossRef]

- Liu YL, Gong SY, Xia ST, Wang YL, Peng H, Shen Y, Liu CF. Light therapy: a new option for neurodegenerative diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020 Dec 21;134(6):634-645. [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, DP. Melatonin: Clinical Perspectives in Neurodegeneration. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019 Jul 16;10:480. [CrossRef]

- Won E, Na KS, Kim YK. Associations between Melatonin, Neuroinflammation, and Brain Alterations in Depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Dec 28;23(1):305. [CrossRef]

- Shin, JW. Neuroprotective effects of melatonin in neurodegenerative and autoimmune central nervous system diseases. Encephalitis. 2023 Apr;3(2):44-53. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Tan J, Liu Y, Dong GH, Yang BY, Li N, Wang L, Chen G, Li S, Guo Y. Long-term exposure to outdoor light at night and mild cognitive impairment: A nationwide study in Chinese veterans. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Nov 15;847:157441. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni E, Vinceti M, Costanzini S, Garuti C, Adani G, Vinceti G, Zamboni G, Tondelli M, Galli C, Salemme S, Teggi S, Chiari A, Filippini T. Outdoor artificial light at night and risk of early-onset dementia: A case-control study in the Modena population, Northern Italy. Heliyon. 2023 Jun 29;9(7):e17837. [CrossRef]

- Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):704-11. [CrossRef]

- Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, Sarli G, D'Antonio F, Tariciotti L, de Lena C, Bruno G. Sundowning in Dementia: Clinical Relevance, Pathophysiological Determinants, and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Med (Lausanne). 2016;3:73. [CrossRef]

- Toccaceli Blasi M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, D'Antonio F, Talarico G, Campanelli A, Sepe Monti M, Salati E, Gasparini M, Buscarnera S, Salzillo M, Canevelli M, Bruno G. Sundowning in Patients with Dementia: Identification, Prevalence, and Clinical Correlates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;94(2):601-610. [CrossRef]

- Feng R, Li L, Yu H, Liu M, Zhao W. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cell loss and circadian dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2016 Apr;13(4):3397-400. [CrossRef]

- La Morgia C, Ross-Cisneros FN, Koronyo Y, Hannibal J, Gallassi R, Cantalupo G, Sambati L, Pan BX, Tozer KR, Barboni P, Provini F, Avanzini P, Carbonelli M, Pelosi A, Chui H, Liguori R, Baruzzi A, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Sadun AA, Carelli V. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cell loss in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016 Jan;79(1):90-109. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Lv QK, Xie WY, Gong SY, Zhuang S, Liu JY, Mao CJ, Liu CF. Circadian disruption and sleep disorders in neurodegeneration. Transl Neurodegener. 2023 Feb 13;12(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Gracitelli CP, Duque-Chica GL, Roizenblatt M, Moura AL, Nagy BV, Ragot de Melo G, Borba PD, Teixeira SH, Tufik S, Ventura DF, Paranhos A., Jr Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell activity is associated with decreased sleep quality in patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1139–48. [CrossRef]

- Mahanna-Gabrielli E, Kuwayama S, Tarraf W, Kaur S, DeBuc DC, Cai J, Daviglus ML, Joslin CE, Lee DJ, Mendoza-Santiesteban C, Stickel AM, Zheng D, González HM, Ramos AR. The Effect of Self-Reported Visual Impairment and Sleep on Cognitive Decline: Results of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;92(4):1257-1267. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki A, Udry M, El Wardani M, Münch M. Can Extra Daytime Light Exposure Improve Well-Being and Sleep? A Pilot Study of Patients With Glaucoma. Front Neurol. 2021 Jan 15;11:584479. [CrossRef]

- Chellappa SL, Bromundt V, Frey S, Schlote T, Goldblum D, Cajochen C. Cross-sectional study of intraocular cataract lens replacement, circadian rest-activity rhythms, and sleep quality in older adults. Sleep. 2022 Apr 11;45(4):zsac027. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D. , Boldyreva, J., Stefani, O., Kolomeichuk, S., Danilova, L., Markov, A., … Weinert, D. Light exposure predicts COVID-19 negative status in young adults. Biological Rhythm Research. 2024. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bano-Otalora B, Martial F, Harding C, Bechtold DA, Allen AE, Brown TM, Belle MDC, Lucas RJ. Bright daytime light enhances circadian amplitude in a diurnal mammal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Jun 1;118(22):e2100094118. [CrossRef]

- Münch M, Nowozin C, Regente J, Bes F, De Zeeuw J, Hädel S, Wahnschaffe A, Kunz D. Blue-Enriched Morning Light as a Countermeasure to Light at the Wrong Time: Effects on Cognition, Sleepiness, Sleep, and Circadian Phase. Neuropsychobiology. 2016;74(4):207-218. [CrossRef]

- Figueiro MG, Sahin L, Kalsher M, Plitnick B, Rea MS. Long-Term, All-Day Exposure to Circadian-Effective Light Improves Sleep, Mood, and Behavior in Persons with Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2020 Aug 4;4(1):297-312. [CrossRef]

- Juda M, Liu-Ambrose T, Feldman F, Suvagau C, Mistlberger RE. Light in the Senior Home: Effects of Dynamic and Individual Light Exposure on Sleep, Cognition, and Well-Being. Clocks Sleep. 2020 Dec 14;2(4):557-576. [CrossRef]

- Zang L, Liu X, Li Y, Liu J, Lu Q, Zhang Y, Meng Q. The effect of light therapy on sleep disorders and psychobehavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023 Dec 6;18(12):e0293977. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Gubin GD, Waterhouse J, Weinert D. The circadian body temperature rhythm in the elderly: effect of single daily melatonin dosing. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(3):639-58. [CrossRef]

- Gubin DG, Gubin GD, Gapon LI, Weinert D. Daily Melatonin Administration Attenuates Age-Dependent Disturbances of Cardiovascular Rhythms. Curr Aging Sci. 2016;9(1):5-13. [CrossRef]

- Böhmer MN, Oppewal A, Valstar MJ, Bindels PJE, van Someren EJW, Maes-Festen DAM. Light up: an intervention study of the effect of environmental dynamic lighting on sleep-wake rhythm, mood and behaviour in older adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2022 Oct;66(10):756-781. [CrossRef]

- Khalsa SB, Jewett ME, Cajochen C, Czeisler CA. A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects. J Physiol. 2003 Jun 15;549(Pt 3):945-52. [CrossRef]

- Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM, Sack RL. Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve. Chronobiol Int. 1992 Oct;9(5):380-92. [CrossRef]

- Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Molina TA, Eastman CI. Human phase response curves to three days of daily melatonin: 0.5 mg versus 3.0 mg. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jul;95(7):3325-31. [CrossRef]

- Partonen, T. Chronotype and Health Outcomes. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep 1, 205–211 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Knutson KL, von Schantz M. Associations between chronotype, morbidity and mortality in the UK Biobank cohort. Chronobiol Int. 2018 Aug;35(8):1045-1053. [CrossRef]

- Makarem N, Paul J, Giardina EV, Liao M, Aggarwal B. Evening chronotype is associated with poor cardiovascular health and adverse health behaviors in a diverse population of women. Chronobiol Int. 2020 May;37(5):673-685. [CrossRef]

- Baldanzi G, Hammar U, Fall T, Lindberg E, Lind L, Elmståhl S, Theorell-Haglöw J. Evening chronotype is associated with elevated biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in the EpiHealth cohort: a cross-sectional study. Sleep. 2022 Feb 14;45(2):zsab226. [CrossRef]

- Dowling GA, Burr RL, Van Someren EJ, Hubbard EM, Luxenberg JS, Mastick J, et al. Melatonin and bright-light treatment for rest-activity disruption in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):239–246. [CrossRef]

- Riemersma-van Der Lek RF, Swaab DF, Twisk J, Hol EM, Hoogendijk WJ, Van Someren EJ. Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(22):2642–2655. [CrossRef]

- McCurry SM, Pike KC, Vitiello MV, Logsdon RG, Larson EB, Teri L. Increasing walking and bright light exposure to improve sleep in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer's disease: results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Aug;59(8):1393-402. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson NA, McPhillips MV, Petrovsky DV, Perez A, Talwar S, Gooneratne N, Riegel B, Aryal S, Gitlin LN. Timed Activity to Minimize Sleep Disturbance in People With Cognitive Impairment. Innov Aging. 2023 Dec 8;8(1):igad132. [CrossRef]

- Hand AJ, Stone JE, Shen L, Vetter C, Cain SW, Bei B, Phillips AJK. Measuring light regularity: sleep regularity is associated with regularity of light exposure in adolescents. Sleep. 2023 Aug 14;46(8):zsad001. [CrossRef]

- Piarulli A, Bergamasco M, Thibaut A, Cologan V, Gosseries O, Laureys S. EEG ultradian rhythmicity differences in disorders of consciousness during wakefulness. J Neurol. 2016 Sep;263(9):1746-60. [CrossRef]

- Goh GH, Maloney SK, Mark PJ, Blache D. Episodic Ultradian Events-Ultradian Rhythms. Biology (Basel). 2019 Mar 14;8(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda D, Esparza A, Ghamari M, Soltanpur C, Nazeran H. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int J Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;4(4):195-202. [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann F, Wolf U. The Pulse-Respiration Quotient: A Powerful but Untapped Parameter for Modern Studies About Human Physiology and Pathophysiology. Front Physiol. 2019 Apr 9;10:371. [CrossRef]

- Rafl J, Bachman TE, Rafl-Huttova V, Walzel S, Rozanek M. Commercial smartwatch with pulse oximeter detects short-time hypoxemia as well as standard medical-grade device: Validation study. Digit Health. 2022 Oct 11;8:20552076221132127. [CrossRef]

- Santos M, Vollam S, Pimentel MA, Areia C, Young L, Roman C, Ede J, Piper P, King E, Harford M, Shah A, Gustafson O, Tarassenko L, Watkinson P. The Use of Wearable Pulse Oximeters in the Prompt Detection of Hypoxemia and During Movement: Diagnostic Accuracy Study. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Feb 15;24(2):e28890. [CrossRef]

- Charlton PH, Kyriaco PA, Mant J, Marozas V, Chowienczyk P, Alastruey J. Wearable Photoplethysmography for Cardiovascular Monitoring. Proc IEEE Inst Electr Electron Eng. 2022 Mar 11;110(3):355-381. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Charlton PH, Allen J, Bailón R, Baker S, Behar JA, Chen F, Clifford GD, Clifton DA, Davies HJ, Ding C, Ding X, Dunn J, Elgendi M, Ferdoushi M, Franklin D, Gil E, Hassan MF, Hernesniemi J, Hu X, Ji N, Khan Y, Kontaxis S, Korhonen I, Kyriacou PA, Laguna P, Lázaro J, Lee C, Levy J, Li Y, Liu C, Liu J, Lu L, Mandic DP, Marozas V, Mejía-Mejía E, Mukkamala R, Nitzan M, Pereira T, Poon CCY, Ramella-Roman JC, Saarinen H, Shandhi MMH, Shin H, Stansby G, Tamura T, Vehkaoja A, Wang WK, Zhang YT, Zhao N, Zheng D, Zhu T. The 2023 wearable photoplethysmography roadmap. Physiol Meas. 2023 Nov 29;44(11):111001. [CrossRef]

- Yeung MK, Lin J. Probing depression, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders using fNIRS and the verbal fluency test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2021 Aug;140:416-435. [CrossRef]

- Nishi R, Fukumoto T, Asakawa A. Possible effect of natural light on emotion recognition and the prefrontal cortex: A scoping review of near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2023 Dec;32(12):1441-1451. [CrossRef]

- Pereira J, Direito B, Lührs M, Castelo-Branco M, Sousa T. Multimodal assessment of the spatial correspondence between fNIRS and fMRI hemodynamic responses in motor tasks. Sci Rep. 2023 Feb 8;13(1):2244. [CrossRef]

- Scarapicchia V, Brown C, Mayo C, Gawryluk JR. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: Insights from Combined Recording Studies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 Aug 18;11:419. [CrossRef]

- Orban C, Kong R, Li J, Chee MWL, Yeo BTT. Time of day is associated with paradoxical reductions in global signal fluctuation and functional connectivity. PLoS Biol. 2020 Feb 18;18(2):e3000602. [CrossRef]

- Murata EM, Pritschet L, Grotzinger H, Taylor CM, Jacobs EG. Circadian rhythms tied to changes in brain morphology in a densely-sampled male. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Apr 14:2024.04.10.588906. [CrossRef]

- Baria AT, Baliki MN, Parrish T, Apkarian AV. Anatomical and functional assemblies of brain BOLD oscillations. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(21):7910-9. [CrossRef]

- Chang C, Metzger CD, Glover GH, Duyn JH, Heinze HJ, Walter M. Association between heart rate variability and fluctuations in resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2013; 68:93-104. [CrossRef]

- Chen JE, Glover GH. BOLD fractional contribution to resting-state functional connectivity above 0.1 Hz. Neuroimage. 2015;107:207-218. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka K, Cornelissen G, Furukawa S, Shibata K, Kubo Y, Mizuno K, Aiba T, Ohshima H, Mukai C. Unconscious mind activates central cardiovascular network and promotes adaptation to microgravity possibly anti-aging during 1-year-long spaceflight. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11862. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka K, Cornelissen G, Kubo Y, Shibata K, Mizuno K, Aiba T, Furukawa S, Ohshima H, Mukai C. Methods for assessing change in brain plasticity at night and psychological resilience during daytime between repeated long-duration space missions. Sci Rep. 2023; 13(1):10909. [CrossRef]

- Brothers MC, DeBrosse M, Grigsby CC, Naik RR, Hussain SM, Heikenfeld J, Kim SS. Achievements and Challenges for Real-Time Sensing of Analytes in Sweat within Wearable Platforms. Acc Chem Res. 2019 Feb 19;52(2):297-306. [CrossRef]

- Jagannath B, Lin KC, Pali M, Sankhala D, Muthukumar S, Prasad S. A Sweat-based Wearable Enabling Technology for Real-time Monitoring of IL-1β and CRP as Potential Markers for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020 Sep 18;26(10):1533-1542. [CrossRef]

- Hirten RP, Lin KC, Whang J, Shahub S, Churcher NKM, Helmus D, Muthukumar S, Sands B, Prasad S. Longitudinal monitoring of IL-6 and CRP in inflammatory bowel disease using IBD-AWARE. Biosens Bioelectron X. 2024 Feb;16:100435. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Liu Z, Feng S, Gao Z, Chen R, Cai G, Bian S. Wearable Microfluidic Sweat Chip for Detection of Sweat Glucose and pH in Long-Distance Running Exercise. Biosensors. 2023; 13(2):157. [CrossRef]

- Ok J, Park S, Jung YH, Kim TI. Wearable and Implantable Cortisol-Sensing Electronics for Stress Monitoring. Adv Mater. 2024 Jan;36(1):e2211595. [CrossRef]

- Watkins Z, McHenry A, Heikenfeld J. Wearing the Lab: Advances and Challenges in Skin-Interfaced Systems for Continuous Biochemical Sensing. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2024;187:223-282. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, He Z, Zhao W, Liu C, Zhou S, Ibrahim OO, Wang C, Wang Q. Innovative Material-Based Wearable Non-Invasive Electrochemical Sweat Sensors towards Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2024 May 14;14(10):857. [CrossRef]

- Singh NK, Chung S, Chang AY, Wang J, Hall DA. A non-invasive wearable stress patch for real-time cortisol monitoring using a pseudoknot-assisted aptamer. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023 May 1;227:115097. [CrossRef]

- Ding H, Yang H, Tsujimura S. Nature-Inspired Superhydrophilic Biosponge as Structural Beneficial Platform for Sweating Analysis Patch. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Jun 13:e2401947. [CrossRef]

- Brown, TM. Melanopic illuminance defines the magnitude of human circadian light responses under a wide range of conditions. J Pineal Res. 2020 Aug;69(1):e12655. [CrossRef]

- van Duijnhoven, J. , Hartmeyer S., Didikoğlu A., et al. Overview of wearable light loggers: State-of-the-art and outlook. TechRxiv. June 03, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Giménez MC, Stefani O, Cajochen C, Lang D, Deuring G, Schlangen LJM. Predicting melatonin suppression by light in humans: Unifying photoreceptor-based equivalent daylight illuminances, spectral composition, timing and duration of light exposure. J Pineal Res. 2022 Mar;72(2):e12786. [CrossRef]

- Trinh VQ, Bodrogi P, Khanh TQ. Determination and Measurement of Melanopic Equivalent Daylight (D65) Illuminance (mEDI) in the Context of Smart and Integrative Lighting. Sensors (Basel). 2023 May 23;23(11):5000. [CrossRef]

- Stampfli JR, Schrader B, di Battista C, Häfliger R, Schälli O, Wichmann G, Zumbühl C, Blattner P, Cajochen C, Lazar R, Spitschan M. The Light-Dosimeter: A new device to help advance research on the non-visual responses to light. Light Res Technol. 2023 Feb 13;55(4-5):474-486. [CrossRef]

- Juzeniene A, Moan J. Beneficial effects of UV radiation other than via vitamin D production. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012 Apr 1;4(2):109-17. [CrossRef]

- Giménez MC, Luxwolda M, Van Stipriaan EG, Bollen PP, Hoekman RL, Koopmans MA, Arany PR, Krames MR, Berends AC, Hut RA, Gordijn MCM. Effects of Near-Infrared Light on Well-Being and Health in Human Subjects with Mild Sleep-Related Complaints: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Biology (Basel). 2022 Dec 29;12(1):60. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Cui F, Wang T, Wang W, Zhang D. The impact of sunlight exposure on brain structural markers in the UK Biobank. Sci Rep. 2024 May 5;14(1):10313. [CrossRef]

- Slominski RM, Chen JY, Raman C, Slominski AT. Photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology: How the ultraviolet radiation regulates the body, brain, and immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Apr 2;121(14):e2308374121. [CrossRef]

- Kallioğlu MA, Sharma A, Kallioğlu A, Kumar S, Khargotra R, Singh T. UV index-based model for predicting synthesis of (pre-)vitamin D3 in the mediterranean basin. Sci Rep. 2024 Feb 12;14(1):3541. [CrossRef]

- Hacker E, Horsham C, Allen M, Nathan A, Lowe J, Janda M. Capturing Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure and Physical Activity: Feasibility Study and Comparison Between Self-Reports, Mobile Apps, Dosimeters, and Accelerometers. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018 Apr 17;7(4):e102. [CrossRef]

- Kervezee L, Dashti HS, Pilz LK, Skarke C, Ruben MD. Using routinely collected clinical data for circadian medicine: A review of opportunities and challenges. PLOS Digit Health. 2024 May 23;3(5):e0000511. [CrossRef]

- Spitschan M, Zauner J, Tengelin MN, Bouroussis CF, Caspar P, Eloi F. Illuminating the future of wearable light metrology: Overview of the MeLiDos Project. Measurement. 2024. 114909. [CrossRef]

- Spitschan, M. Selecting, implementing and evaluating control and placebo conditions in light therapy and light-based interventions. Ann Med. 2024 Dec;56(1):2298875. [CrossRef]

- Bowman C, Huang Y, Walch OJ, Fang Y, Frank E, Tyler J, Mayer C, Stockbridge C, Goldstein C, Sen S, Forger DB. A method for characterizing daily physiology from widely used wearables. Cell Rep Methods. 2021 Aug 23;1(4):100058. [CrossRef]

- Buekers J, Theunis J, De Boever P, Vaes AW, Koopman M, Janssen EV, Wouters EF, Spruit MA, Aerts JM. Wearable Finger Pulse Oximetry for Continuous Oxygen Saturation Measurements During Daily Home Routines of Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Over One Week: Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Jun 6;7(6):e12866. [CrossRef]

- Hua J, Li J, Jiang Y, Xie S, Shi Y, Pan L. Skin-Attachable Sensors for Biomedical Applications. Biomed Mater Devices. 2022 Oct 3:1-13. [CrossRef]

- You Y, Liu J, Li X, Wang P, Liu R, Ma X. Relationship between accelerometer-measured sleep duration and Stroop performance: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study among young adults. PeerJ. 2024 Feb 28;12:e17057. [CrossRef]

- Emish M, Young SD. Remote Wearable Neuroimaging Devices for Health Monitoring and Neurophenotyping: A Scoping Review. Biomimetics (Basel). 2024 Apr 16;9(4):237. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Mayer C, Walch OJ, Bowman C, Sen S, Goldstein C, Tyler J, Forger DB. Distinct Circadian Assessments From Wearable Data Reveal Social Distancing Promoted Internal Desynchrony Between Circadian Markers. Front Digit Health. 2021 Nov 16;3:727504. [CrossRef]

- Braund TA, Zin MT, Boonstra TW, Wong QJJ, Larsen ME, Christensen H, Tillman G, O'Dea B. Smartphone Sensor Data for Identifying and Monitoring Symptoms of Mood Disorders: A Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2022 May 4;9(5):e35549. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, McMahon M, Fritz H, Schnyer DM. circadian rhythms are not captured equal: Exploring Circadian metrics extracted by different computational methods from smartphone accelerometer and GPS sensors in daily life tracking. Digit Health. 2022 Jul 18;8:20552076221114201. [CrossRef]

- Lin C, Chen IM, Chuang HH, Wang ZW, Lin HH, Lin YH. Examining Human-Smartphone Interaction as a Proxy for Circadian Rhythm in Patients With Insomnia: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res. 2023 Dec 15;25:e48044. [CrossRef]

- Innominato PF, Macdonald JH, Saxton W, Longshaw L, Granger R, Naja I, Allocca C, Edwards R, Rasheed S, Folkvord F, de Batlle J, Ail R, Motta E, Bale C, Fuller C, Mullard AP, Subbe CP, Griffiths D, Wreglesworth NI, Pecchia L, Fico G, Antonini A. Digital Remote Monitoring Using an mHealth Solution for Survivors of Cancer: Protocol for a Pilot Observational Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024 Apr 30;13:e52957. [CrossRef]

- Borer KT, Cornelissen G, Halberg F, Brook R, Rajagopalan S, Fay W. Circadian blood pressure overswinging in a physically fit, normotensive African American woman. Am J Hypertens. 2002 Sep;15(9):827-30. [CrossRef]

- Velasquez MT, Beddhu S, Nobakht E, Rahman M, Raj DS. Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease: Ready for Prime Time? Kidney Int Rep. 2016 Jul;1(2):94-104. [CrossRef]

- Schlagintweit J, Laharnar N, Glos M, Zemann M, Demin AV, Lederer K, Penzel T, Fietze I. Effects of sleep fragmentation and partial sleep restriction on heart rate variability during night. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 17;13(1):6202. [CrossRef]

- Laharnar N, Fatek J, Zemann M, Glos M, Lederer K, Suvorov AV, Demin AV, Penzel T, Fietze I. A sleep intervention study comparing effects of sleep restriction and fragmentation on sleep and vigilance and the need for recovery. Physiol Behav. 2020 Mar 1;215:112794. [CrossRef]

- Qian X, Droste SK, Lightman SL, Reul JM, Linthorst AC. Circadian and ultradian rhythms of free glucocorticoid hormone are highly synchronized between the blood, the subcutaneous tissue, and the brain. Endocrinology. 2012 Sep;153(9):4346-53. [CrossRef]

- Zhu B, Zhang Q, Pan Y, Mace EM, York B, Antoulas AC, et al. A Cell-Autonomous Mammalian 12 hr Clock Coordinates Metabolic and Stress Rhythms. Cell Metab. 2017;25(6):1305–19 e9. [CrossRef]

- Goh GH, Maloney SK, Mark PJ, Blache D. Episodic Ultradian Events-Ultradian Rhythms. Biology (Basel). 2019 Mar 14;8(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Grant AD, Newman M, Kriegsfeld LJ. Ultradian rhythms in heart rate variability and distal body temperature anticipate onset of the luteinizing hormone surge. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 23;10(1):20378. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka K, Murakami S, Okajima K, Shibata K, Kubo Y, Gubin DG, Beaty LA, Cornelissen G. Appropriate Circadian-Circasemidian Coupling Protects Blood Pressure from Morning Surge and Promotes Human Resilience and Wellbeing. Clin Interv Aging. 2023 May 10;18:755-769. [CrossRef]

- Iimuro S, Imai E, Watanabe T, Nitta K, Akizawa T, Matsuo S, Makino H, Ohashi Y, Hishida A. Hyperbaric area index calculated from ABPM elucidates the condition of CKD patients: the CKD-JAC study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015 Feb;19(1):114-24. [CrossRef]

- Edgley K, Chun HY, Whiteley WN, Tsanas A. New Insights into Stroke from Continuous Passively Collected Temperature and Sleep Data Using Wrist-Worn Wearables. Sensors (Basel). 2023 Jan 17;23(3):1069. [CrossRef]

- Korman M, Tkachev V, Reis C, Komada Y, Kitamura S, Gubin D, Kumar V, Roenneberg T. COVID-19-mandated social restrictions unveil the impact of social time pressure on sleep and body clock. Sci Rep. 2020 Dec 17;10(1):22225. [CrossRef]

| Accelerometry-based: | Others: |

|---|---|