1. Introduction

The gut microbiota refers to the complex microbial ecosystem in our digestive tract [

1] which has a major role in host physiology [

2]: from metabolism, immunity to the brain and nervous system [

3]. Due to extreme interindividual variability, with only 10% of the gut microbiota being shared between individuals, there is no standard gut microbiota composition [

4]. But it is widely agreed that a diverse, balanced, and highly functional gut microbiota, which is abundant in health-promoting bacteria and lacks potentially pathogenic and pro-inflammatory bacteria is ideal for optimal health [

5].

The intentional optimization of gut microbiota composition and functionality with gut microbiota targeted therapeutics such as probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics is traditionally investigated in the context of the prevention and treatment of various infectious, metabolic, and autoimmune diseases. Probiotics are live microorganisms which exert beneficial health effects upon consumption [

6], prebiotics are substrates that are utilised selectively by the gut microbiome for growth [

7], and postbiotics are inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host [

8].

Recently, an increasing interest in gut microbiota optimization in the field of sports nutrition has been seen [

9]. No wonder since the gut microbiota is essential for athlete health and performance, and especially recovery [

10,

11]. Its metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (e.g. butyrate), lactic acid and neuroactive metabolites (GABA, serotonin) directly and indirectly via immune, hormonal or nervous signaling improve the functioning of the gut-muscle, gut-joint, gut-liver, but also gut-brain axes, which are all crucial for athletic performance, as well as recovery [

12,

13]. A well-known example in this context is

Veillonela atypica, discovered in active marathon runners [

14], which converts exercise-derived lactate into propionate which can serve as a substrate for gluconeogenesis in the liver, a phenomenon found also in other genera [

15]. One the other hand is regular physical activity beneficial for the gut microbiota, hence rendering the gut microbiota of athletes more diverse and functional than the one of sedentary individuals [

16,

17,

18].

To the best of our knowledge, research on the field of gut microbiota optimization in athletes was focused mainly on probiotics, with prebiotics being mostly neglected, and synbiotics such as whole fermented foods even more. Current evidence suggests that probiotics are effective solely in athletes regarding recovery and prevention of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

Sauerkraut is rich in pro- and prebiotics. It is probably the most popular fermented whole food preparation in Europe. Sauerkraut is a fermented vegetable product which is derived from the malolactic fermentation of raw fresh white cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) in a salt brine with 2–3% (w/w) sodium chloride. Since the fermentation process involves several live beneficial lactic acid bacteria (LAB) naturally present on the fresh cabbage or in the food processing environment, sauerkraut is regarded as a probiotic-rich food. Some of them are Weissella spp., Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Levilactobacillus brevis, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, and Pediococcus pentosaceus. Literature reports that these probiotic bacteria are resistant to bile salts and low gastric pH (one even to β-hemolysis) and demonstrate antimicrobial activity. During food fermentation, controlled bacterial metabolism (activity and growth) on the medium converts fermentable substrates, mainly carbohydrates and proteins, into biologically active metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and biogenic amines. Besides that, sauerkraut is rich in fiber by nature, which can act as a prebiotic. Therefore, sauerkraut can be regarded as a synbiotic whole food, whose beneficial effect is due to all of its compounds: pro-, pre- and postbiotics.

The health benefits of sauerkraut consumption have been studied in a limited body of research, mostly on in vitro models [

19]. Human clinical trials are still scarce. Nevertheless, consumption of fermented foods bearing similar properties to sauerkraut has been correlated in sports nutrition with improvements regarding immunity and metabolism, specifically an increase in anti-inflammatory pathways and decrease in fasting blood glucose levels in diabetes. The underlying cause of the observed effects can be probably attributed to the ingestion of certain probiotic bacteria and bioactive compounds such as the fiber found in the starting food material and the fermentation related metabolites. Especially short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), such as butyrate and biogenic amines and natural polyamines (putrescine, spermine, spermidine) have been shown to induce a plethora of beneficiary effects in the gastrointestinal tract (intestinal motility, barrier function, energy source) and immune system (anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory effects).

Since no data on the potential of specifically sauerkraut in sports nutrition was found, especially in the context of gut microbiota optimization, a gap of knowledge was detected. A proof-of-concept study was conceived to explore the potential of sauerkraut for gut microbiota optimization in active athletes. The hypotheses being that sauerkraut is on one hand a synbiotic, rich in beneficial bacteria and prebiotics, and on the other hand effective in inducing significant favorable changes in the gut microbiota composition and functionality, independent of baseline gut microbiota status and even when supplemented for a short period of time. Besides the gut microbiota, the aim was to assess the effects of short-term supplementation on bowel function and routine laboratory parameters, to gain insight into the risks and feasibility of sauerkraut supplementation in sports nutrition. The purpose of this preliminary study was to obtain data which would guide high-quality future research on this topic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study was conceived as a preliminary proof-of-concept study. A cohort of professional athletes was followed over a short course of sauerkraut supplementation where its effects were monitored by gut microbiota and laboratory analyses. For the intervention duration of 10 days was picked. The reasoning for such a short intervention time was twofold. On one hand to prove that sauerkraut is indeed an effective synbiotic which does not require extensive time for action, similar to other studies [

20,

22]. On the other hand, is the long-term monitoring (e.g. a month) of potential confounding factors such as diet and training impossible due to the highly variable schedule of professional athletes.

Participants were recruited in collaboration with the Croatian Olympic Committee. The goal was to recruit professional athletes of different athletic disciplines to yield a more general overview. The inclusion criteria were: (1) adult age, (2) male gender, (3) either status of a professional athlete by standards of the Olympic Committee or professional engagement in Non-Olympic sports, (4) good general physical health (as assessed by the annual health check-up by the Olympic Committee Medical Commission or primary medical care). Exclusion criteria were: (1) administration of antibiotics at least six months prior or during the intervention, (2) supplementation with probiotics at least six months prior or during the intervention, (3) chronic medical therapy, (4) known intolerance to sauerkraut or cabbage intake. Volunteers fulfilling the inclusion criteria visited the Gut Microbiome Center for an initial screening where they received a detailed verbal explanation and written instructions by the team of researchers. A written informed consent form was obtained after all methods, risks, and benefits were thoroughly explained. The participants were handed the kits for the stool sampling and the sauerkraut. Body composition was assessed prior intervention using a TANITA Body Composition Analyzer MC-780.

The participants were asked to record all the food, beverages and dietary supplements they consumed using a 7-day food record before the start of the intervention and a 10-day food record during the intervention, as well as the Athlete Diet Index Questionnaire (ADI) [22] to evaluate their nutritional and lifestyle behavior (fiber intake, frequency and intensity of physical activity) and energy intake. The day prior to the start of the intervention the participants provided a stool sample following the instructions at their home. The participants were instructed not to alter their lifestyle and dietary behavior throughout the intervention and to report it in the online form.

The intervention consisted of the daily supplementation of 250 grams of sauerkraut, independent of body mass, over the course of ten days. The participants were allowed to have variations in the daily amount and the time of intake during the day depending on the situation in the given days due to self-rationing and reported the quantity of ingested sauerkraut and time of intake in the online form. The participants consumed the sauerkraut throughout the day, either alone or in combination with other food in a meal (salad, side dish). The participants were inquired to report whether they had experienced any adverse effects consequently. The day after the end of the intervention the participants provided the second stool sample which was sent off to the laboratory, and once again completed the ADI. The present study took place during the off-season for all athletes.

2.2. Participants

A minimum of ten active athletes was defined as the minimal study population to yield significant results. All participants completed detailed food records regarding dietary intake, including lifestyle (sleep, physical activity) prior and during the intervention. The participants noted daily the amount and time of sauerkraut supplementation and the incidence of any adverse effects which could potentially be associated with the sauerkraut intake.

All procedures relative to this study were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics committee of the School of Medicine, University in Zagreb for the protection of human subjects (ref. number 380-59-10106-23-111/36) on the date 27.03.2023. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov under the number NCT06087146.

2.3. Supplementation Protocol

The sauerkraut used in this study was produced by Eko Imanje Zrno Ltd., Vrbovec, Croatia. The sauerkraut was locally sourced, grown under organic conditions and prepared by fermentation using a salt brine without the use of preservatives and pasteurized. The sauerkraut was packaged in glass jars in portions of 500 grams. Every participant received five jars of sauerkraut. Before commencement of study, sauerkraut was tested for its nutritional and microbiological properties in accredited laboratories of the School of Biotechnology and Food Technology of the University of Zagreb. The nutritional information is enclosed in

Table 1. In cultures the count of lactic acid forming bacteria was 4.82·10

3 (±2,31) CFU/ml. In cultures, no harmful microorganisms were detected including

Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, sulfite-reducing Clostridia and fungi (<10 CFU/g). The sauerkraut was tested for its microbiome composition by 16s rRNA amplicon sequencing using Illumina NGS (Biomes NGS Ltd, Wildau, Germany). Five samples were taken for analysis according to the following sampling protocol: two samples of sauerkraut brine of equal quantity (10 ml), one 5 ml sample of sauerkraut brine and two samples containing 6 g and 3 g respectively of sauerkraut itself in addition to 5 ml of brine.

2.4. Standardisation of Physical Activity, Sleep and Diet

Physical activity and diet were evaluated using a specially designated online form in Excel (Microsoft, Palo Alto, USA). Participants entered the start and end as well as type of each training session the seven days before and ten days of the intervention. Dietary intake was monitored during the same period in the two phases and participants noted the time, quantity and ingredients of every ingested food item following the instructions by the researchers. If the participants were not able to weigh the quantity of a specific food item, they utilised the Capnutra food atlas to indicate food quantity. The data was then analysed by the researchers (dietitians) and food intake was classified regarding macronutrient and energy intake as average values before and during intervention using USDA food composition databases. The Athlete Diet Index (ADI) served as a measure of convergent validity to assess potential changes in the diet before and during intervention. The ADI is a valid and reliable diet quality assessment tool in the form of an online questionnaire. It was developed purposely for active athletes and evaluates regular dietary intake, especially regarding nutrients relevant to athletes, compared to sports nutrition recommendations by generating an overall score of the athlete's diet [22].

2.5. 16. s rRNA NGS of the Gut Microbiota

Stool samples were taken the day before and one day after the end of supplementation (Day 0 and Day 11). The day before and the day after the intervention the participants took stool samples using a cotton swab of the toilet paper at their home following the instructions and the swabs were conserved in up to 1000 µL of DNA-stabilising buffer. The samples were transported by logistical services the next workday over a course of a couple of days to the laboratory (Biomes NGS, Wildau, Germany). Upon arrival the stool samples were stored at −20 °C until sequencing. For the lysis process the samples were defrosted and centrifuged at 4.000 g for 15 minutes. Afterwards, 650 µL of warmed up lysis buffer was added to each sample, and then vortexed for 20 minutes. Afterwards the nucleic acids were extracted on a liquid handling system (Hamilton StarLine & Tecan EVO) by using a vacuum chamber as well as a high-pressure chamber. The extracted gDNA was stored at -20° C until use. The library preparation followed the manual “16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation- Preparing 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Amplicons for the Illumina MiSeq System”. For normalisation of all samples, a fluorescent dye, and the Biotek Synergy HTX plate reader were used to measure DNA concentrations, and to calculate the necessary dilution volume per sample. All the steps described are nearly fully automated by using a liquid handling system (Hamilton StarLine), allowing for parallel sample processing. The Library Denaturing and MiSeq Sample Loading was carried out manually following the Illumina protocol for MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle). Demultiplexing was performed directly on the platform, using MiSeq Reporter Analysis software, right after sequencing and the resulting FastQ files were generated for subsequent data analysis.

For the processing and analysis of sequence data the Paired-End-Reads from MiSeq (2x300 cycles) were merged to reconstruct overlapping sequences with 430-460 base-length. Chimera and borderline reads were filtered out with the usearch uchime2_ref tool. SILVA 138.1 is used as a Database for usearch uchime2_ref. For taxonomic alignment, Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were determined using BLASTn (Nucleotide-Nucleotide BLAST 2.10.1+) against SILVA 138.1 [

23]. Alignment identity must meet a threshold of at least: Phylum: 75.0 %, Class: 78.5 %, Order: 82.4 %, Family: 86.5 %, Genus: 94.5 % and Species: 97.0 %. RefSeqs/Counts tables were created for all samples using Python package Pandas 1.3.4. The taxonomic composition of microbial communities is inferred from ASV (Amplicon sequence variants) counts at the phylum, genus, and species level. Further bioinformatic analyses were done using Picrust2 [

24]. The study sequences of the alignment step were placed into a reference tree to determine/predict the copy numbers and the NSTI-index (Nearest-sequenced taxon index). All study sequences with NSTI-index higher than 2 were excluded.

This same method was utilised to analyse the sauerkraut and its constituents (cabbage, brine) for its microbiome composition present in the product delivered to the participants.

2.6. Laboratory Analysis

The day before and after the end of the intervention a laboratory analysis was performed to assess potential changes in the participant’s physiology associated with the sauerkraut supplementation. The laboratory measures taken were:

Blood count: erythrocytes, leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes

Metabolism: serum low-dense lipoprotein cholesterol levels (LDL), uric acid levels

Hormone levels: thyroid (TSH, FT3), testosterone, blood glucose (insulin, HOMA-IR), cortisol

Vitamins: vitamin D, B12, folic acid

The laboratory analysis was performed at a tertiary health care facility using EDTA or citrate blood depending on the respective measure on a standard laboratory set-up.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For the analysis, all online forms were coded, and the data was imported into SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted.

Data on dietary intake and lifestyle were quantitative variables. After they were tested for the distribution type using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the results of the descriptive analyses were presented as median and interquartile range. Differences in the distributions of the quantitative variables were analysed with Mann-Whitney U tests.

Statistical analysis of the results of the gut microbiota analyses were performed. For alpha-diversity calculations ASV counts were rarefied to 10.000 counts per sample. Shannon-index was chosen as alpha-diversity metric and calculated using the diversity function provided by Qiime2 [

25]. In addition, relative abundance of the

Lactobacillus Group and of the Phylum

Proteobacteria were evaluated in relation to sauerkraut intervention. A Repeated Measures Correlation was performed for hypothesis testing, using the R function rmcorr [

26]. Calculated p-values were adjusted for multiple testing, using Benjamini & Hochberg correction and significance was assumed at a p-value< 0.05 (non-FDR) [

27].

To account for the compositional properties of relative ASV-abundances a centered-log-ratio (clr) transformation was performed in preparation for further analyses. As the logarithm of zero is undefined, all values were summed with a small pseudocount which amounts to the smallest non-zero value divided by 10. To visualize compositional differences between treatment groups a principal component analysis was conducted using the PCA function of the R package FactoMineR [

28].

To identify differentially abundant genera and pathways in regard to sauerkraut intervention, a Repeated Measure Correlation was performed, using the R package rmcorr [

26]. Analysis was carried out on Genus and Pathway level using a filtered table with a cutoff at 0.1% average relative abundance across all samples. To account for compositionality, centered-log ratio transformation was applied using a pseudocount of the smallest non-zero value divided by 10. Calculated p-values were adjusted for multiple testing, using Benjamini & Hochberg correction and significance is assumed at a p-value< 0.05 (non-FDR).

The R package ggplot2 was used for visualization [

29].

For the statistical analysis of the five sauerkraut samples PERMANOVA analysis (permutational multivariate variance analysis) and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were utilised in Python using Pandas and SciKit libraries to test whether the samples containing brine were similar to each other and whether they significantly differed from the samples containing the sauerkraut itself regarding the distribution of relative abundances of bacteria.

In order to calculate 95% confidence interval for the probability of Bristol stool type to be 3 or 4 during the period of ten days, a binomial test was performed in R programming language. In the same programming language, the probability of Bristol stool type to be 3 or 4 for each day was calculated using the chi- squared test. As statistically significant values were taken, ones that p- value was lower than 0.5. Hazard ratio was obtained by putting into ratio the number of participants that had Bristol stool type 3 or 4 compared to the number of all the participants for each day.

3. Results

3.1. Sauerkraut Microbiota

The 16s rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of the five sauerkraut samples revealed 1416 taxa and a total of 515.608 aligned reads, at average 103.121.6±53.380.8. The ten most abundant bacterial genera were in order of abundance:

Bacteroides, Blautia, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, Agathobacter, Fusicatenibacter, Lachnospiracae (unspecific), Subdoligranum. The added relative abundances of these ten genera accounted for around 50% in four of the five samples (all brine samples and the sample with 50% sauerkraut). All the aforementioned predominant genera of the sauerkraut’s microbiota are obligate aerobes and are highly metabolically active. Utilising carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), such as glycoside hydrolases, and fermentative enzymes, such as butyrate and acetate kinase, these genera are known to produce SCFA such as butyrate [

30]. The results of PERMANOVA analysis (F-statistic = 2.735, p-value = 0.095) indicated that there were certain differences in the microbiota composition between the samples containing sauerkraut and exclusively brine, but those differences were not significant. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with two samples found that the microbiota composition of the brine samples did not differ among each other (statistic = 0.042, p-value = 0.171), but did differ when compared with the sauerkraut samples (statistic = 0.147, p-value < 0.001). This test also confirmed that the microbiota composition between the two sauerkraut samples differed as well (statistic = 0.188, p-value < 0.001), indicating that the difference in sauerkraut to brine ratio impacted the microbiota composition of the samples.

3.2. The Intervention

The CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility studies as well as the SPIRIT Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Studies guidelines were utilised in designing the study protocol and results reporting.

The study was conducted over a course of six months in a collaboration between several organisations: The Gut Microbiome Center in Zagreb, Croatia, the Faculty of Food and Biotechnology, University of Zagreb and the laboratory of Biomes NGS Ltd., Wildau, Germany.

The characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 2a, including gender, age, type of sport, and years of sport participation. Regarding the classification of participants based on their level of physical activity and sport performance, participants were classified using the 6-tiered Participant Classification Framework. Although the plan was to conduct the study on only male athletes, one female participant was included since the principal aim of the study was to perform the analysis on the professional athletes and no additional interested male athletes were found.

The physical characteristics (height and body mass) and body composition variables (fat-free mass, skeletal muscle mass, percentage of body fat and fat mass) are shown in

Table 2b. The data from participant 3 could not be retrieved due to technical issues.

Physical activity and sleep were monitored before and during the intervention. Data on frequency and average duration of physical activity and sleep quantity is disclosed in

Table 2c. No statistically significant differences before and during the intervention were registered.

All aspects of dietary intake were monitored before and during the intervention. Data on average daily dietary intake is disclosed in

Table 2d. Besides the significant increase in daily fiber per 1000 kcal intake during the intervention, no other statistically significant differences regarding food intake before and during the intervention were registered. These observed changes could be attributed to the sauerkraut intake, since it is inself rich in fiber, but low in calories. Due to certain specific dietary habits recorded by the participants (eg. fast food and prepackaged foods for which nutritional information is difficult to obtain) and disparities in nutritional information present in food composition tables and food declarations, the aforementioned dietary intake results are only estimates and should be taken with caution.

Not all participants completed all subscales of the ADI due to bad compliance. The data for those who completed it shows that there were no significant differences before and during the intervention (

Table 2e). The detected low fiber intake and a relatively low carbohydrate intake by the participants is in accordance with their qualitative ADI results which hint to an insufficient grain intake among all participants.

The food records and the ADI questionnaire showed independently that the participants did not significantly alter their dietary intake during the intervention.

3.3. Gut Microbiota

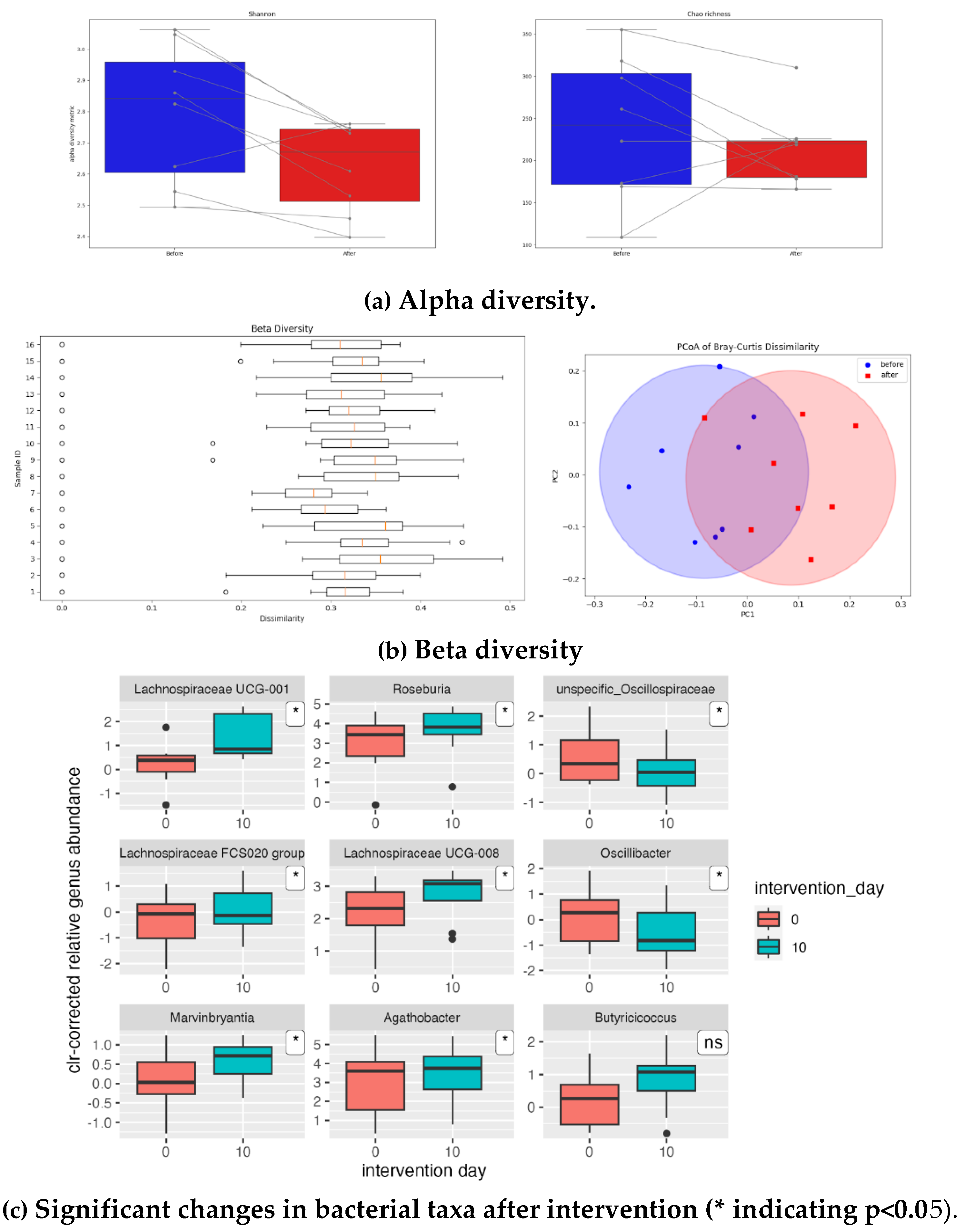

The results of the faecal microbiota analyses were analysed regarding alterations in relative abundances of bacterial counts grouped either in taxonomic or functional groups, therefore indicating changes in gut microbiota composition and functionality. A presentation of general results is disclosed in

Figure 1.

No significant differences were found in the α-diversity of the gut microbiota of the study population due to sauerkraut intervention (Fig.1a). In order to see if the saurkraut had impact on gut microbiota composition, beta diversity was calculated for the taxonomy levels genus and phyla using Bray-Curtis metrics. The level of significance was obtained using ANOSIM (33). The results show that there was a significant difference in gut microbiota composition (p < . 001) post sauerkraut supplementation. However, a R value of 0.314 indicates that the difference is moderate (

Figure 1b). On the taxonomy level, after the intervention significant changes in bacterial counts on taxonomic levels were seen in eight genera (Fig. 1c). Increases in genera belonging to family Lachnospiraceae: Lachnospiraceae UCG-008, Lachnospiraceae UUCG-001, Roseburia, Lachnospiraceae FCS020 Group, Marvinbryantia as well as Agathobacter (formerly known as Eubacterium rectale) and decreases in genera belonging to family Oscillospiracaeae: unspecific Oscillospiraceae and Oscillibacter.

3.4. Gut Microbiota Functionality

A total of 190 metabolic pathways were analyzed among the identified bacterial groups. Significant changes in bacterial counts in 35 metabolic pathways were found (18.4%). Those changes affected exclusively pathways which concern cell wall synthesis and the metabolism of nucleotide bases (purine, pyrimidine, etc.) and were negatively correlated to the sauerkraut intake. Bacteria actively involved in these pathways were significantly affected by the intervention, with low rates of false positives observed changes. The pathways significantly affected by the sauerkraut intervention are disclosed in

Table 3a.

To better understand the functional dynamics of microbial communities, we grouped the functional metabolic pathways predicted with PiCRUST2 into functional modules using MetaCYC, based on their class, ontology or interpretation. Several significant changes were observed. After grouping, we found that the metabolic pathways involved in polysaccharide and sugar degradation as well as protein fermentation were enhanced after intervention. At the same time, metabolic pathways involved in butyrate metabolism and inflammation were decreased. However, after adjustment for multiple testing, the false discovery rate (FDR) showed no significant differences in predicted functionality between pre- and post-intervention (

Table 3b).

3.5. Laboratory Analyses

A spectrum of laboratory parameters from blood samples were assessed over the course and after the intervention. Data on the average values before and the day after are disclosed in

Table 4. Besides an increase in serum lymphocyte counts and decrease in serum B12 levels no significant short-term changes in laboratory parameters were seen after the intervention.

3.6. Bowel Movement and Adverse Effects

Participants reported bowel movement and potential adverse effects if any through their study diary. Results are disclosed below in

Table 5. Although at the beginning of the intervention different types of Bristol stool types (BST) were reported, from Day 8 to Day 10 all participants but one reported having BST 3 or 4, which are considered physiological forms and consistencies of stool. Statistical analysis showed that the probability for BST 3 and 4 significantly increased after a week of sauerkraut consumption. A minority of participants reported bloating, diarrhea and pain during the intervention, no episodes of constipation were reported. The largest number of adverse effects was reported around Days 5 to 6.

4. Discussion

The current study confirmed the two initial hypotheses. Organic, pasteurized sauerkraut potentially is an effective synbiotic rich in health-promoting anaerobes. When around 250 g of it is supplemented over a course of only ten days it induces several significant changes in the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota in active athletes, as well as significant changes in the proportion of lymphocytes and levels of vitamin B12. But its supplementation is associated with a risk of indigestion, which resolves after a week of administration. Therefore, sauerkraut could indeed be utilised in sports nutrition for gut microbiota optimization in all athletes, confirming the concept of sauerkraut as an effective synbiotic food product for athlete health and performance.

Our study showed that sauerkraut has a diverse microbiota itself, especially rich in beneficial anaerobes, albeit not harbouring any harmful microorganisms. Interestingly, LAB were not the most abundant members like it is the case in other studies [

32,

33], and even in culture their number was smaller than expected. The sauerkraut’s health-promoting bacteria can be found in the kraut as well as the brine, indicating that potentially even the brine alone could be used in sports nutrition for gut microbiota optimization. But due to differences in nutrient and bacteria distribution the required quantities could differ from the daily 250 g used in the present study.

Regarding taxonomic changes sauerkraut supplementation seems to invoke a specific shift in the gut microbiota composition: an increase in families producing short-chain fatty acids from fiber fermentation such as Lachnospiraceae, Butyricicoccaceae and Clostridiaceae, and decrease in families Akkermansiaceae (belonging to the significantly reduced phylum Verrucomicrobia) and Oscillospiraceae. This is supported by statistically significant results regarding beta diversity (Fig 1b). It is important to note that these changes were independent of baseline gut microbiota composition, since these changes were seen in all participants and in the same direction.

Complementary studies showed that Blautia and Roseburia species, often associated with a healthy state of the microbiota, are some of the main SCFA producers. Blautia and Roseburia are health-promoting bacteria since they are the genera most involved in the control of gut inflammatory processes, atherosclerosis, and maturation of the immune system, demonstrating that the end products of bacterial metabolism (butyrate) mediate these effects.

Besides the specific changes in composition, even more significant changes were seen in the abundance of specific pathways within the gut microbiome. When considered on their own, the abundance of individual pathways associated in the metabolism of nucleotide bases were significantly reduced, as well as those involved in cell wall synthesis. When the pathways were grouped into modules based on functionality significant, but potentially falsely positive, changes were also observed: regarding not only the metabolism of nutrients (carbohydrate, sugars and protein), but also related to butyrate metabolism and inflammation.

The data suggests that the changes induced by sauerkraut in the gut microbiota are highly favourable for the individual athlete. Although sauerkraut supplementation did not render all participants’ gut microbiota more diverse (α-diversity) and balanced (Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio), it increased the abundance of health-promoting SCFA producing bacteria and made the gut microbiota more functional by changing a large number of metabolic pathways.

A possible consequence of these positive changes in the gut microbiota could be the significant increase in the proportion of lymphocytes. Although increased lymphocyte percentages are usually associated with certain pathologies such as viral infections, hematologic and chronic inflammatory states, the values did not reach levels typical for such conditions [

34]. But it is known that certain gut bacteria and its metabolites promote the proliferation of B and T lymphocytes in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [

35]. Pro-, pre- and synbiotics have been found to enhance the immune response and stimulate lymphocyte proliferation and activity [

36] The observed increase could potentially be a result of the changes in the gut microbiota caused by the sauerkraut supplementation.

Changes in the gut microbiota post sauerkraut could also be responsible for the decrease in vitamin B12 levels. Serum vitamin B12 levels depend on dietary intake [

37] and production in the gut microbiota [

38], especially by bacteria such as Pseudomonas denitrificans, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Lactobacillus reuteri and plantarum, Clostridium difficile and butyricum, Fusobacterium spp. as well as Akkermansia muciniphila. The decrease in vitamin B12 levels could be attributed to the significant decrease in the relative abundance of family Akkermansiaceae, which was the most significant decrease of all bacterial families, and its member Akkermansia muciniphila. Another explanation could be that the increase in health-promoting obligate anaerobes, such as Roseburia and Blautia was at the expense of a decrease in potentially pathogenic facultative anaerobes, such as Pseudomonas, Klebsiella and Lactobacillus, which produce vitamin B12. Higher levels of vitamin B12 have been associated with the development of colorectal cancer [

39], and the root of this association could lie in the gut microbiota, or in a imbalance of the gut microbiota respectively. Therefore, the decrease in vitamin B12 probably should not be regarded as a negative consequence, but on the contrary as another positive result of sauerkraut supplementation.

It is important to note that sauekraut intake was associated with indigestion in several participants. This is known from literature and clinical practice since pro- and prebiotic administration has been associated with gastrointestinal side-effects such as bloating, gaseousness, pain and changes in bowel movement [

40]. Another possible reason could be histamin intolerance since fermented food are rich in biogene amines such as histamin. But since these side-effects of the sauerkraut supplementation waned after a week of supplementation, one could state that sauerkraut supplementation does come with a certain risk of indigestion during the first days of administration. But with regular use, digestion and the gut microbiota apparently adapts to its compounds and then sauerkraut becomes safe to use.

There are several limitations of this study, hindering further conclusions. The main limitation of this study was the small subject number, due to the many technical and organizational challenges facing studies on active athletes. This is represented by high false positive rates in the significant results of the study, especially regarding the main findings of the study – the changes in bacterial taxa. Studies on greater samples are required to yield a clearer picture on the described effects. Secondly, since a fermented food was investigated, and not its isolated compounds, this study design may not deliver insight which specific compound in sauerkraut was most contributing to the described effects. We cannot attribute the results to specific probiotics, nor prebiotic or postibiotic compounds in sauerkraut specifically. One can even hypothesize that in the ittinerated analysis of the participant's gut microbiota the microbiota of the sauerkraut was detected, and not an alterated domicile gut microbiota. A further limitation due to study design is the fact that it is difficult to state whether the changes seen after the intervention were positive or negative regarding athletic performance. Another question is whether the observed changes are temporarily or permanent, and how long they persist after cessation of sauerkraut intake. Since there is a lack of information regarding a healthy human gut microbiota or effective athlete gut microbiota for reference we cannot conclude whether the changes seen actually are part of a so-called gut microbiota optimization.

5. Conclusions

The present study confirms the concept that sauerkraut supplementation could potentially be used in sports nutrition for gut microbiota optimization. The microbiota of organic, pasteurized sauerkraut is rich in anaerobic bacteria. The benefits of sauerkraut intake for active athletes are favorable changes in the gut microbiota composition and functionality, in the form of increased numbers of health-promoting bacteria and improved functionality. These could result in an enhanced immune response with increased lymphocytes, and decreased metabolism of potentially pathogenic facultative anaerobes, resulting in decreased vitamin B12. But since sauerkraut supplementation poses a risk of indigestion a seven-day long adaptation period is required. In a follow-up study, these results have to be reproduced in a greater number of subjects and tested for sustainability by adding a wash-out period. In the future sauerkraut brine could be investigated and supplementation provided for a longer time

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., A-M.L.P. and Z.Š.; methodology, A.K.; software, A.S.; validation, A.K., M.I. and A.S.; formal analysis, I.R. and A.S.; investigation, K.R., E.S., A-M.L.P. and J.Z.; resources, A.K.; data curation, K.R., E.S. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A-M.L.P.; visualization, I.R.; supervision, Z.Š., Ž.K. and A.S.; project administration, K.R. and E.S.; funding acquisition, Ž.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Gagliardi A, Totino V, Cacciotti F, Iebba V, Neroni B, Bonfiglio G et al. Rebuilding the Gut Microbiota Ecosystem. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018, 15, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Salvadori M, Rosso G. Update on the gut microbiome in health and diseases. World J Methodol. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri MH, Brummer RJM, Rastall RA, Weersma RK, Harmsen HJM, Faas M et al. The role of the microbiome for human health: From basic science to clinical applications. Eur J Nutr. 2018, 57 (Suppl 1), 1–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012, 486, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- King CH, Desai H, Sylvetsky AC, LoTempio J, Ayanyan S, Carrie J et al. Baseline human gut microbiota profile in healthy people and standard reporting template. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay A, Lee CY, Lee YC, Liu CL, Chen HK, Li YH et al. Twnbiome: A public database of the healthy Taiwanese gut microbiome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2023, 24, 474. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G., Hutkins, R., Sanders, M. et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Salminen S, Collado MC, Endo A, Hill C, Lebeer S, Quigley EMM et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [CrossRef]

- Nolte S, Krüger K, Lenz C, Zentgraf K. Optimizing the Gut Microbiota for Individualized Performance Development in Elite Athletes. Biology (Basel). 2023, 12, 1491. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien MT, O'Sullivan O, Claesson MJ, Cotter PD. The Athlete Gut Microbiome and its Relevance to Health and Performance: A Review. Sports Med. 2022, 52 (Suppl 1), 119-128. [CrossRef]

- Cronin O, O'Sullivan O, Barton W, Cotter PD, Molloy MG, Shanahan F. Gut microbiota: Implications for sports and exercise medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2017, 51, 700–701. [CrossRef]

- Turpin-Nolan SM, Joyner MJ, Febbraio MA. Can microbes increase exercise performance in athletes? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 629–630. [CrossRef]

- Clark A, Mach N. Exercise-induced stress behavior, gut-microbiota-brain axis and diet: A systematic review for athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2016, 13, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Scheiman J, Luber JM, Chavkin TA, MacDonald T, Tung A, Pham LD et al. Meta-omics analysis of elite athletes identifies a performance-enhancing microbe that functions via lactate metabolism. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 1104–1109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. Lactate-utilizing bacteria, isolated from human feces, that produce butyrate as a major fermentation product. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5810–5817. [CrossRef]

- Petersen LM, Bautista EJ, Nguyen H, Hanson BM, Chen L, Lek SH et al. Community characteristics of the gut microbiomes of competitive cyclists. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Barton W, Penney NC, Cronin O, Garcia-Perez I, Molloy MG, Holmes E et al. The microbiome of professional athletes differs from that of more sedentary subjects in composition and particularly at the functional metabolic level. Gut. 2018, 67, 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Fontana F, Longhi G, Tarracchini C, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Alessandri G et al. The human gut microbiome of athletes: Metagenomic and metabolic insights. Microbiome. 2023, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Raak C, Ostermann T, Boehm K, Molsberger F. Regular consumption of sauerkraut and its effect on human health: A bibliometric analysis. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014, 3, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Lessard-Lord J, Roussel C, Lupien-Meilleur J, Généreux P, Richard V, Guay V et al. Short term supplementation with cranberry extract modulates gut microbiota in human and displays a bifidogenic effect. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Cancello R, Turroni S, Rampelli S, Cattaldo S, Candela M, Cattani L et al. Effect of Short-Term Dietary Intervention and Probiotic Mix Supplementation on the Gut Microbiota of Elderly Obese Women. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Capling L, Gifford JA, Beck KL, Flood VM, Slater GJ, Denyer GS et al. Development of an Athlete Diet Index for Rapid Dietary Assessment of Athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019, 29, 643–650. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza, P, Peplies J et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596.

- Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zeneveld JR, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688.

- Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich, N. A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857.

- Bakdash JZ, Marusich LR. Repeated Measures Correlation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017, 8, 1–13.

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995, 57, 289–300.

- Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18.

- Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (2nd ed.). Meas. Interdiscip. Res. Perspect. 2019, 17, 160–167.

- Hiseni P, Rudi K, Wilson RC, Hegge FT, Snipen L.. HumGut: A comprehensive human gut prokaryotic genomes collection filtered by metagenome data. Microbiome. 2021, 9, 165. [CrossRef]

- Somerfield PJ, Clarke KR, Gorley RN. A generalised analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) statistic for designs with ordered factors. Austral Ecology. 2021, 46, 901–910.

- Zhang S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Zhang L, Wang S. Characterization of microbiota of naturally fermented sauerkraut by high-throughput sequencing. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 855–862. [CrossRef]

- Palmnäs-Bédard M, de Santa Izabel A, Dicksved J, Landberg R. Characterization of the Bacterial Composition of 47 Fermented Foods in Sweden. Foods. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chakroun A, BAccouche A, MAhjoub S, Romdhane NB. Assessment of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytosis in Adults: Determination of Thresholds for Differential Diagnosis between Clonal and Reactive Lymphocytosis. Medical Laboratory Journal. 2021, 15, 23–30.

- Chen VL, Kasper DL.. Interactions between the intestinal microbiota and innate lymphoid cells. Gut Microbes. 2014, 5, 129–140. [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux A, Brosseau C, Bodinier M. Immunomodulation of B Lymphocytes by Prebiotics, Probiotics and Synbiotics: Application in Pathologies. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 269. [CrossRef]

- Farquharson J, Adams JF. The forms of vitamin B12 in foods. Br J Nutr. 1976, 36, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Magnúsdóttir S, Ravcheev D, de Crécy-Lagard V, Thiele I. Systematic genome assessment of B-vitamin biosynthesis suggests co-operation among gut microbes. Front Genet. 2015, 6, 148. [CrossRef]

- Arendt JF, Pedersen L, Nexo E, Sørensen HT. Elevated plasma vitamin B12 levels as a marker for cancer: A population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1799–1805. [CrossRef]

- Marteau P, Seksik P. Tolerance of probiotics and prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004, 38 (6 Suppl), S67-S69. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).