1. Introduction

Novel organic materials obtained from molecular self-assembling through low energy interactions, such as Van der Waals bonds, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds and stacking interactions originate well-ordered supramolecular structures. A versatile method for creating architectures of nanostructured materials, by using amino acids as natural building blocks, is offered by self-assembled peptide-based systems, which are attracting increasing attention due to their biocompatibility and diverse structural and functional properties for applications in a variety of fields from regenerative medicine to fluorescent probes, light energy harvesting and optical waveguiding [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Due to their spontaneous process of self-organization peptide nanostructures have a great advantage of other organic materials.

Aromatic and aliphatic dipeptide nanotubes (NT) are a unique class of bio-inspired nanostructures forming simple and modifiable organic materials, which crystallize into tubular structures hundreds of nanometers long and internal diameters of tens of angstroms. These structures result from stacking of molecules through the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between functional groups in the peptide backbone [

5,

6].

The most studied self-assembled system is L-phenylalanyl-L-phenylalanine or diphenylalanine (hereafter PhePhe) [

7] which is formed by the self-assembling of the aromatic dipeptide into NT, with ere large hydrophilic channels formation as revealed by Gorbitz [

8], such as nanowires [

9] and nanorods [

10] depending on the experimental conditions such as pH and temperature. PhePhe NT have been integrated in devices for electronic and biosensing applications [

11,

12,

13]. These nanostructures display unique and extraordinary mechanical properties: they are very stiff with a high averaged point stiffness and Young’s modulus of 160 N/m and 19-27 GPa respectively, placing them among the stiffest biological materials known [

14]. Due to the chirality of L-phenylalanine amino-acid, PhePhe NT are noncentrosymmetric structures which crystalize in P6

1,5 space group [

8]. An effective nonlinear optical coefficient similar

) has been reported for PhePhe NT [

15]. However, for an all-organic crystalline material, the PhePhe nonlinearity is one order of magnitude smaller than those displayed by some state-of-the-art organic crystals like 2-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA) [

16].

An analogue of PhePhe dipeptide structural family is the amine-modified Boc-L-phenylalanyl-L-phenylalanine (hereafter Boc-PhePhe, Boc= tert-butoxycarbonyl) that forms various nanoscale structures such as nanospheres (NS) [

17] and NT [

18]. Directional intermolecular π-π interactions and hydrogen-bonding networks originate quantum confined (QC) structures (that is, nanocrystalline regions possessing strong QC properties) within PhePhe, Boc-PhePhe and Boc-

p-nitro-L-phenylalanyl-

p-nitro-L-phenylalanine (hereafter Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe) self-assemblies with pronounced exciton effects [

19,

20,

21]. This last one, Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe is the first dipeptide reported as displaying dual self-assembling from 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFP) and water solutions: it self-assembles into microtapes which are themselves formed from self-assembly of nanotubes [

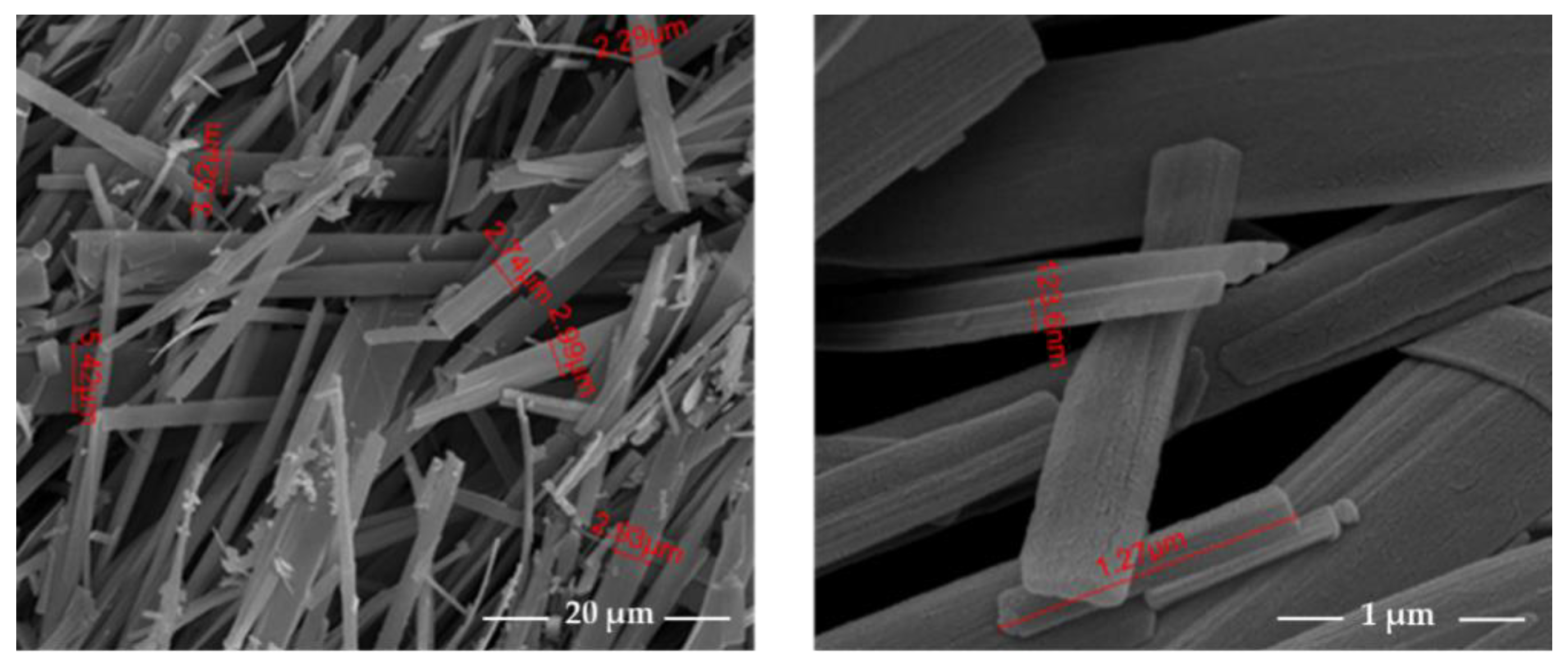

22].

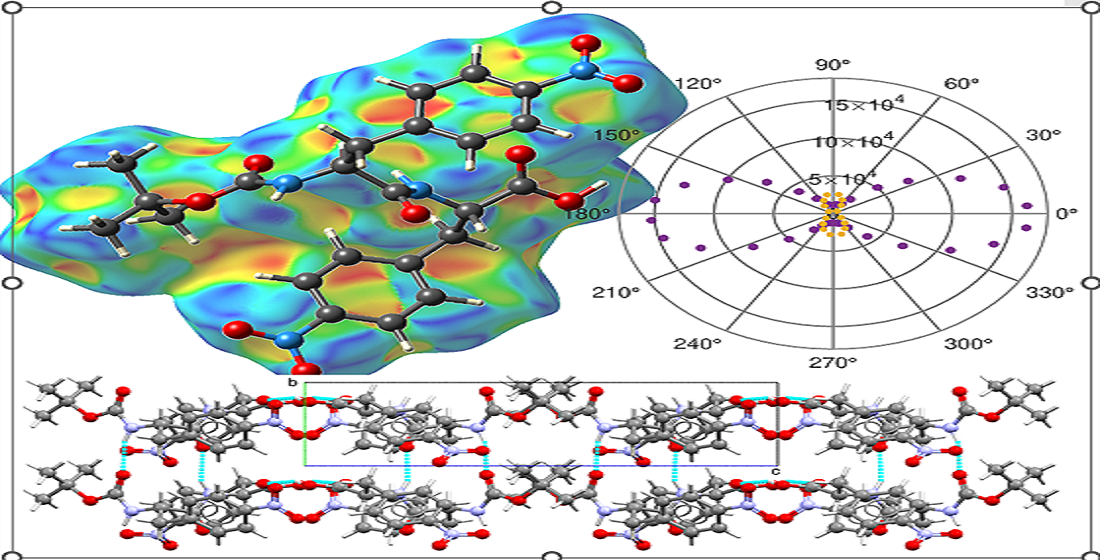

All amino acids, with exception of glycine, naturally display a chiral molecular structure and crystallize therefore with no center of symmetry. The lack of a center of a symmetry allows properties such as piezoelectricity and optical second harmonic generation to be displayed by the crystalline compounds. Consequently, dipeptides formed from chiral L-phenylalanine amino acid or derivatives, are non-centrosymmetric bio-active systems for exploring those properties. The piezoelectric properties of self-assembled Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe,

Figure 1, when embedded into electrospun polymer fibers have been reported recently and it was found that both dipeptide hybrid systems show a strong piezoelectric response to an applied periodical deformation [

22].

Although the molecular self-assembling of these diphenylalanine derivatives has been study in great extension, the solid-state crystalline structure is known only for Boc-PhePhe dieptide. In this work we report the crystal structure of Boc-pNPhepNPhe determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction at 100 K. Also, because the crystal space group is acentric, the optical second harmonic generation (SHG) property of Boc-pNPhepNPhe microtapes is also reported.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Synthesis

p-Nitro-L-phenylalanine (pNPhe), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), N,N-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), thionyl chloride, and di-tert-butylpyrocarbonate (Boc₂O) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Alfa Aesar and used without further purification. All solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

The synthesis began by protecting the acid terminal of pNPhe through reaction with thionyl chloride in methanol, yielding the corresponding methyl ester of the amino acid. Then, the amino terminal was protected by reaction with di-tert-butylpyrocarbonate, resulting in the N-Boc-protected amino acid. The dipeptide was obtained by liquid-phase synthesis, coupling the amino acid methyl ester with the N-Boc-protected amino acid, using DCC/HOBt as coupling agents.

Further details of the synthesis can be found in the previously published article [

22].

2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) SI

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (SI1) analysis was performed in a Netzsch 200 Maya (Netzsch, Selb, Germany) under nitrogen flow (50 mL/min). The sample was placed in an aluminium pan. Two heating and one cooling ramp were run at: 2 °K/min, from: -30 °C to 200 °C . Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (SI2) was performed using a TA Q500 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). The sample was placed in a platinum crucible and heated from 30 °C to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen flow (60 mL/min).

2.3. Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data (ϕ scans and ω scans with κ and θ offsets) were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer configured in κ-geometry, equipped with a Photon II CPAD detector and an IμS 3.0 Incoatec microfocus source Cu Kα (λ = 1.54178 Å). A suitable crystal of the compound was selected and mounted on a Kapton fiber using a MiTeGen MicroMount with immersion oil. Data collection was performed at 100 K with an Oxford Cryostream cryostat (800 series Cryostream Plus) attached to the diffractometer. The APEX 4 software [

23] was used for unit cell determination and data collection. Data reduction and global cell refinement were carried out with the Bruker SAINT+ software package [

24], and an absorption correction was applied using a multi-scan method via SADABS [

25]. The structure was solved through intrinsic phasing using ShelXT (Sheldrick, 2015b) within the Olex2 interface [

26] to the SHELX suite, allowing the location of most non-hydrogen atoms. Remaining non-hydrogen atoms were identified from Fourier difference maps calculated through successive full-matrix least-squares refinement cycles on F² using ShelXL[

27] and refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms were placed geometrically and refined using the riding model. Artwork representations were prepared using MERCURY [

28] and PLATON [

29]. The crystallographic data reported here are available under accession number CCDC: 2391827 and can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre at

https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures. Tables and the CIF file were generated using FinalCif [

30].

2.4. Second Harmonic Generation

The second harmonic signal were obtained using a mode-locked Ti:Sapphire oscillator (Coherent Mira) with a nominal pulse duration of 100 fs running at a repetition rate of 76 MHz. Details of the experimental set-up have been described previously [

31]. Briefly, a combination half-wave plate and polarizer was employed to control the incident power onto the samples. The incident beam was focused using a x10 microscope objective with a numerical aperture of 0.25 and an effective focal length of 16.5 mm, producing a spot of approximately 40 µm (1/e

2) diameter in the focal plane. The resulting second harmonic signal in transmission was collected using a second objective (x20 with a numerical aperture of 0.4), filtered by a dichroic mirror, then passed through a combination zero-order half-wave plate and fixed calcite polarizer, before being filtered using a low-pass cut-off filter with a transition wavelength of 650 nm and focused into a multimode fibre bundle. At the output of the fibre bundle, a 0.3 m imaging spectrometer (Shamrock 303i form Andor) isolated the second harmonic signal around 400 nm. A cooled CCD camera (Newton 920 from Andor) was employed to capture the signal which was integrated over the roughly Gaussian profile of the second harmonic spectrum.

Before the focusing objective and after the collimating objective zero-order half-wave-plates at 800 nm and 400 nm respectively were used to control the incident and detected linear polarization states. Two different polarization curves are presented “q-p” and “q-s”. The “q-p” curve corresponds to the case when the transmitted polarization is that which gives rise to the maximum second harmonic signal. The half-wave-plate before focusing objective is then rotated to varying the fundamental polarization of the incident light. For the “q-s” the transmitted linear polarization state was set orthogonal to the “q-p” orientation and again the incident linear polarization was varied using the half-wave plate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structure of Boc-pNPhepNPhe

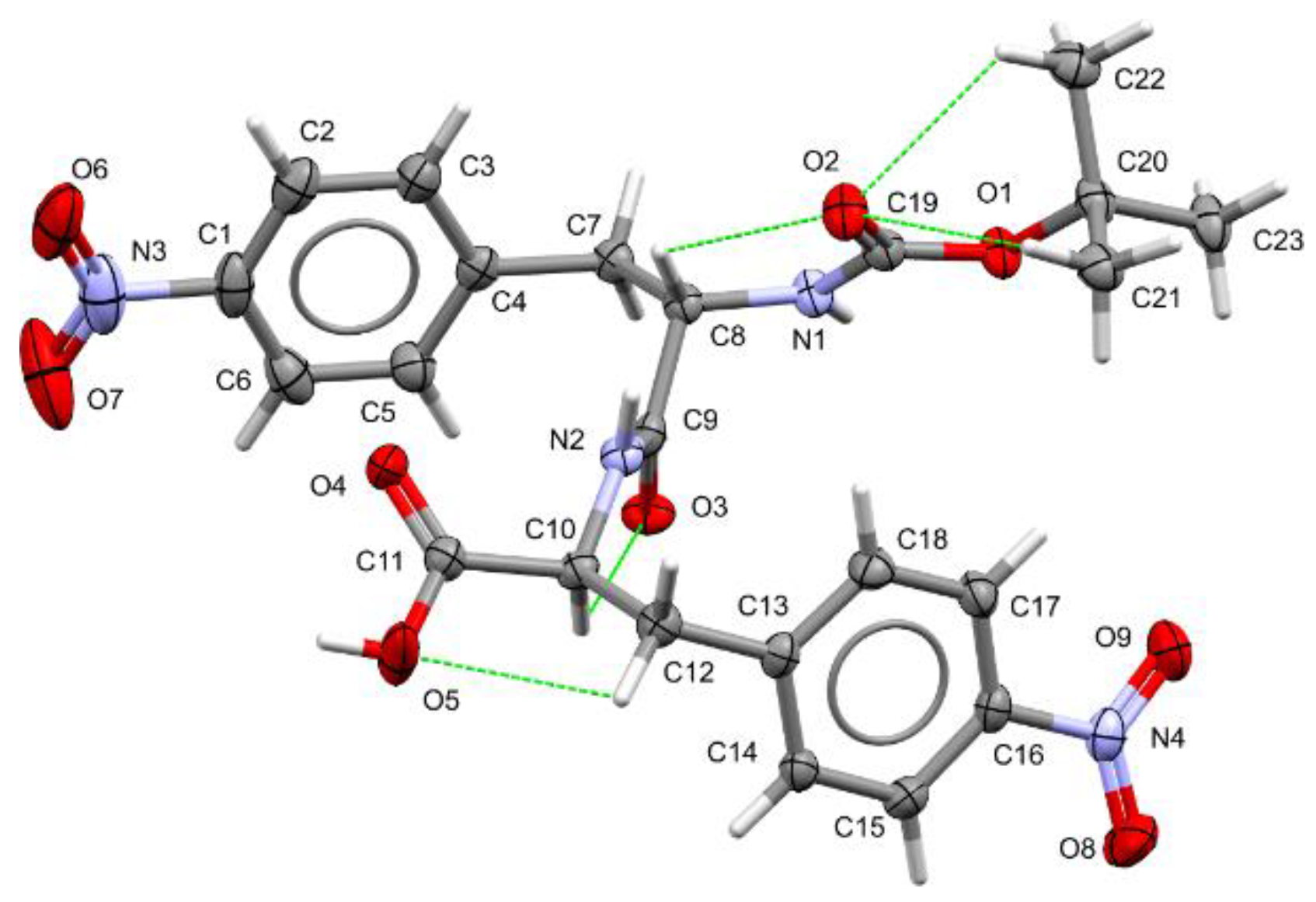

Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, specifically in the non-centrosymmetric space group P2 (

Table 1). The unit cell parameters are a = 12.4892(3) Å, b = 5.11310(10) Å, c = 18.7509(4) Å, and β = 90.4730(10)º. The asymmetric unit contains a single molecule, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Despite possessing bonds that allow significant conformational flexibility, the molecular conformation of Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe in the crystalline state is stabilized by a network of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, depicted as green dashed lines in

Figure 2. Furthermore, the near-zero value of the Flack parameter confirms that the absolute configuration was properly determined.

Notably, the intramolecular hydrogen bonds C8–H8⋯O2 with a distance of 2.773(3) Å and C10–H10⋯O3 at 2.806(3) Å are among the strongest in Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe, playing a critical role in defining its molecular conformation. Despite these constraints, a geometry check performed using the Mogul routine [

32] from the Cambridge Structural Database did not reveal any geometrical parameters significantly deviating from average values.

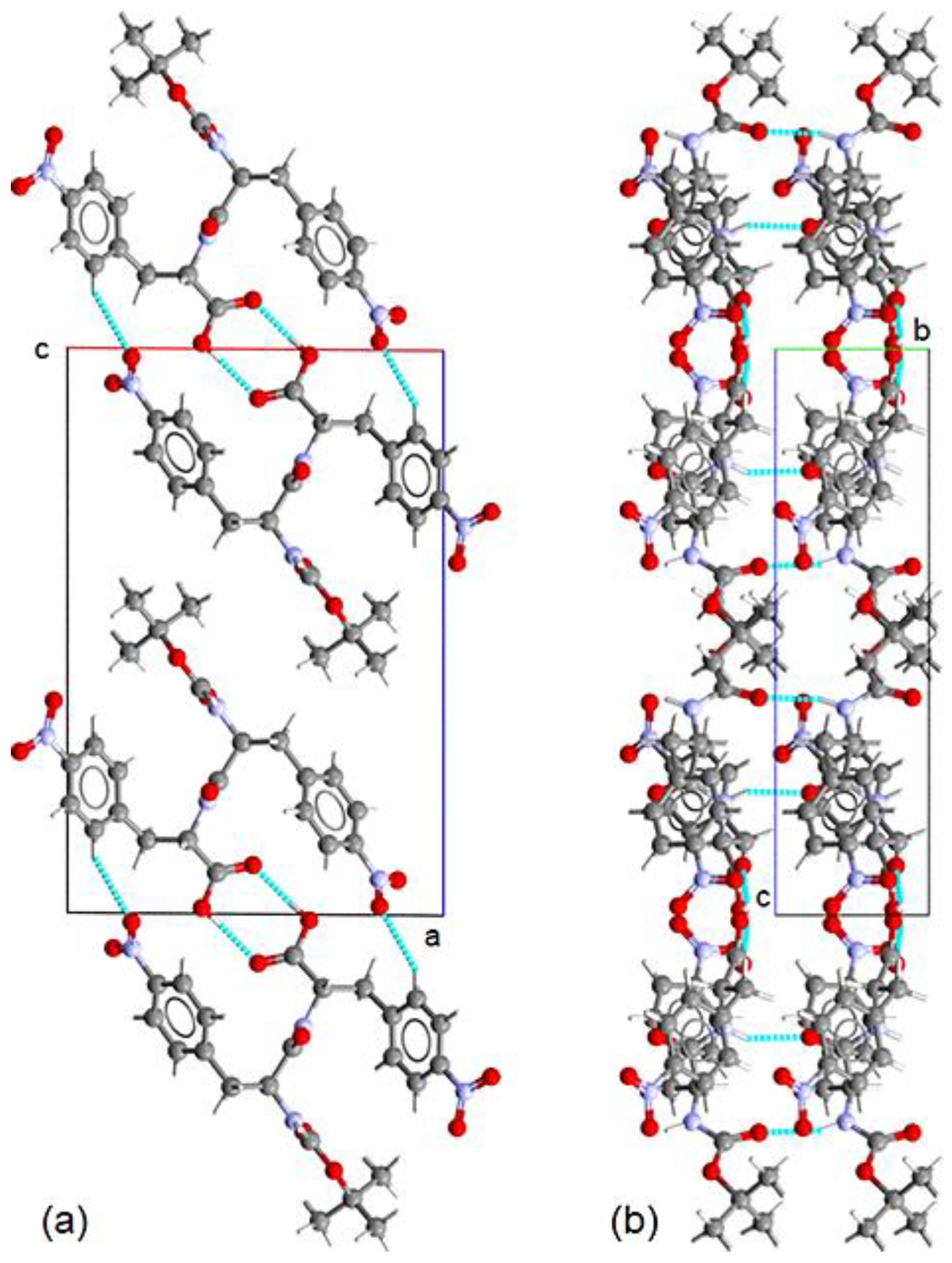

The predominant feature in the crystal packing of Boc-pNPhepNPhe is the formation of a dimer through a homosynthon interaction between the carboxylic groups, creating an

motif centered around the 2-fold axis, as observed in the ac-projection of the crystal structure shown in

Figure 3 a). This dimer is stabilized by a strong O5–H5⋯O4 hydrogen bond, with its parameters listed in

Table 2. The relative orientation of the molecules within the dimer is further defined by a weak hydrogen bond, C14–H14A⋯O7, which together with the strong hydrogen bond determines the final geometry of the dimer.

The stacking of the strongly bonded dimers along the b-axis is facilitated by the trans configuration of the two amide moieties. This arrangement allows the formation of infinite chains through strong N1–H1⋯O2 and N2–H2⋯O3 hydrogen bonds, as illustrated in the bc-projection of the structure depicted in

Figure 3 b). These chains are further stabilized by two π–π interactions between rings of the same type (4.7127(15) Å), as well as by the weak hydrogen bond C5–H5A⋯O4.

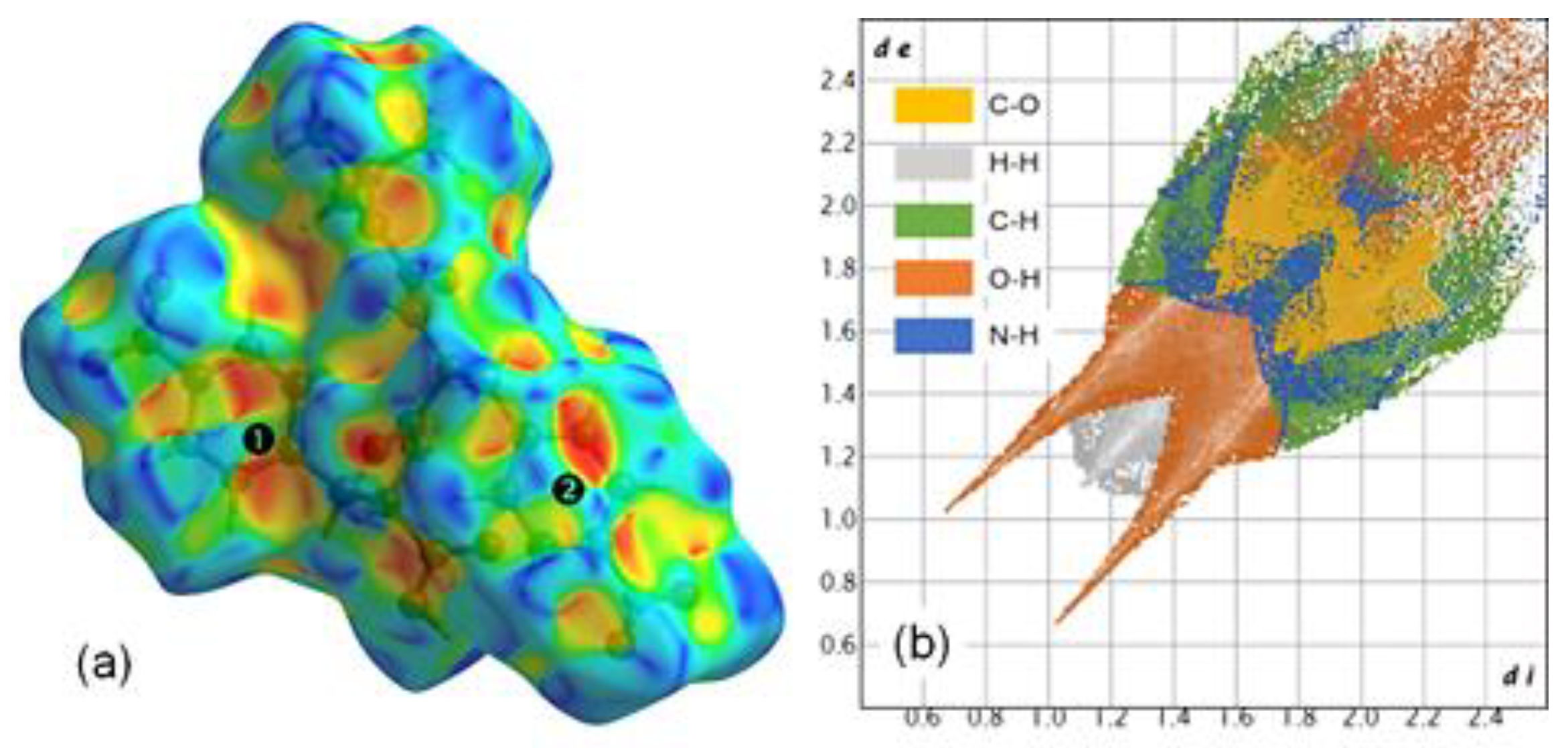

Hydrogen bonds do not play a key role in the packing of the amide chains, as only a hydrogen bond (C2–H2A⋯O8) links laterally dimers from consecutive layers. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the crystal packing, we performed Hirshfeld surface (HS) analysis mapped with the shape index and generated two-dimensional fingerprint (2DF) plots using the CrystalExplorer software [

33]. Mapping the HS with the shape index allows for the identification and visualization of specific intermolecular interactions, such as π–π and X–Y⋯π interactions, by highlighting complementary regions on the molecular surface. The 2DF plots condense this information into graphical representations that map the frequency and nature of contact points between molecules. These analytical tools are invaluable for comparing and clustering structures, identifying structural similarities, and extracting relevant information about intermolecular interactions [

34,

35,

36].

The HS and 2DF plots are presented in

Figure 4, where the regions above the aromatic rings are labeled

and

. Notably, the characteristic red and blue triangles forming a 'bow-tie' pattern over ring

highlight the π–π interactions associated with the dimer stacking of the amide chains (

Figure 4 a). Above ring

, the HS mapping is less defined, displaying two diffuse 'bow-tie' patterns related to two π–π bonds: one associated with the stacking and a stronger interaction (4.7127(15) Å) between rings of different types, which contributes to the packing of the chains. In this region, a red depression indicates the N4–O8⋯π interaction (3.449(3) Å), is also contributing to the alignment of the parallel chains. This latter interaction is observable in the 2DF plot through the frequency of the C–O distances, which exhibit the wing-like pattern commonly associated with C–H⋯π interactions (

Figure 4 b). Finally, it is noteworthy that the 2DF plot is dominated by two strong spikes corresponding to O–H distances, highlighting the key role of the carboxylic–carboxylic and amide–amide interactions in forming and stacking the Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe dimers.

3.4. Optical Second Harmonic Generation

Second harmonic generation (SHG) is a nonlinear optical process, where a fundamental wave of frequency ω, incident on an acentric crystalline medium, generates another optical wave of frequency 2ω, due to the nonlinear polarization of the medium. Biological materials such as proteins, collagen and viruses, are known to exhibit SHG phenomena due to their non-centrosymmetric structures [

37]. This property is described by a 3rd rank tensor, where the tensor elements are determined by the crystal point group symmetry [

38]. Although SHG has been studied in great extension in several organic crystals, very few studies have been reported on dipeptide crystals.

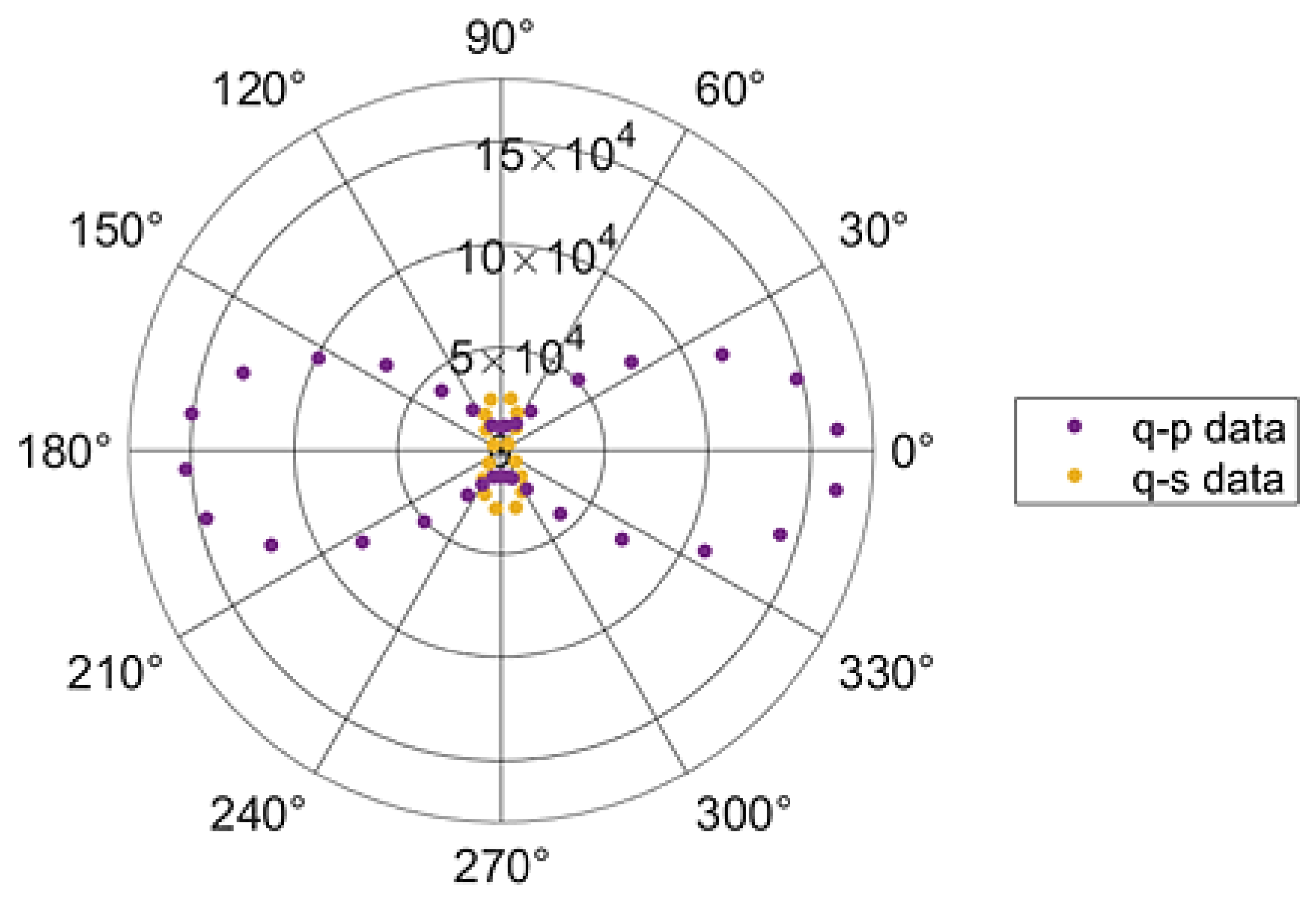

In this work we measured SHG on Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe crystal microtapes, which belong to crystallographic point group 2, the crystals are therefore biaxial. Assuming Kleinman symmetry, the second harmonic light polarization for this point group takes the general form:

Here

are the electric fields associated, with the fundamental optical wave;

are the nonlinear polarizations generated inside the medium and

i,j=1,2,3 are the non-linear optical crystal coefficients. In

Figure 5. It is plotted the second harmonic polarimetry curves for a Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe crystal. For the q-p cure the analyser was oriented along the direction of the strongest second harmonic response, while for the q-s curve the analyser was aligned perpendicular to that direction. In both curves the angle q represents the orientation of the incident linear polarization relative to the analyser direction along which the strongest second harmonic signal was observed. The incident fundamental optical wave vector was perpendicular to the crystallographic

b axis, which is assingned to the dielectric y axis. Due to the difficulty in growing sizeable crystal for the determination of the

x and

z dielectric axis, it was not possible to determine their location and orientation relatively to the crystallographic

a and

b axis. As such, in this work we will only measure an effective coefficient

, from the crystal response.

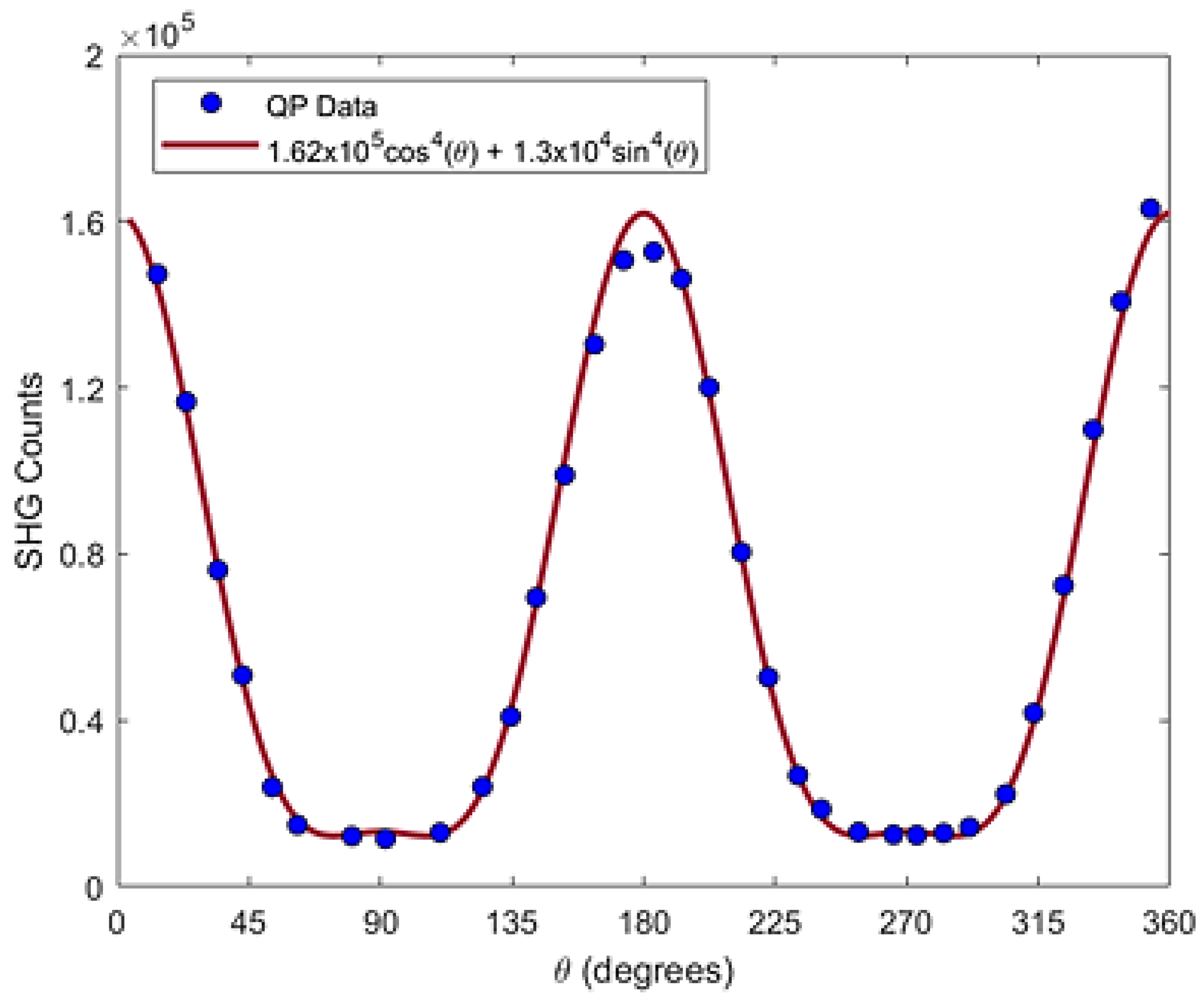

The Boc

pNPhe

pNPhe micro tapes q-p curve displays very nearly a pure

dependence, which occurs when the second harmonic response of a crystalline material is dominated by a single tensor element of the second order nonlinear coefficient, as shown in

Figure 5. However, the q-p curve does not go to zero at 90 and 270 degrees, which results from the fact that for a monoclinic unit cell, the dielectric axis does not coincide with the crystallographic axis. We obtain a good fit to the experimental data, by assuming that there is a small contribution with an orthogonal orientation added in quadrature to the dominate term.

Figure 6. shows the fit to the q-p curve by a function of the form

with A = (1.62±0.01) x10

5 counts and B = (1.3±0.1) x10

4 counts.

To estimate the effective second order nonlinear susceptibility, we have used a 2 mm thick BBO (Barium Beta Borate, from EKSMA, crystal) cut for phase matching at an incident fundamental wavelength of 800 nm, to calibrate the detection efficiency of our experimental set-up. For the strong focusing condition created by the x10 microscope objective, the effective length of the BBO crystal that generates second harmonic light is limited to approximately 30 µm by the spatial walk-off angle of BBO which is 68 mradians for the second harmonic light. Details of the procedure used have been previously published [

39]. The relevant parameters and final results are summarized in

Table 3.

It should be that the second harmonic signals acquired from Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe micro tapes was under normal incidence, no attempt was made to optimized the angle of the fundamental beams wave-vector and therefore the phase-match condition was not achieved. As such the value in

Table 3 for Boc-

pNPhe

pNPhe, represents a lower bound on the estimate of the respective effective coefficient value. Also, as we are determining a non-linear effective coefficient value it means that some coefficients may have magnitudes one or two order of magnitude bigger.

4. Conclusions

Boc-pNPhepNPhe is a dipeptide which self-assembles into microtapes and crystallizes in the non-centrosymmetric space group P2 with a single molecule in the asymmetric unit. The molecular conformation of Boc-pNPhepNPhe in the crystalline structure is stabilized by a network of intramolecular hydrogen bonds althought possessing bonds that allow significant conformational flexibility. In particular, C8–H8⋯O2 with a distance of 2.773(3) Å and C10–H10⋯O3 at 2.806(3) Å intramolecular hydrogen bonds play a fundamental role in Boc-pNPhepNPhe molecular conformation. The key feacture in the crysral unit cell packing is the formation of a dimer through a homosynthon interaction between the carboxylic groups, centered on the 2-fold axis. Moreover, through strong N1–H1⋯O2 and N2–H2⋯O3 hydrogen bonds infinite chains along the b-axis are formed as a result of a stack of the strong bonded dimers along that 2.fold axis.

Hirshfeld surface and two-dimensional fingerprint plots of Boc-pNPhepNPhe show in regions above the aromatic rings a 'bow-tie' pattern highlighting the π–π interactions associated with the dimer stacking of the amide chains. The key role of carboxylic–carboxylic and amide–amide interactions in the formation and stacking of the Boc-pNPhepNPhe dimers are evidenced by the two strong spikes.

Thermal measurements show that the crystalline compound is stable until near 190ºC.

The crystal point group allows nonlinear optical effects to exist. Second harmonic measurements and calculations performed, revealed an effective second order nonlinear susceptibility coefficient higher than 0.52 pm/V, measured against a state-of-the-art phase matched BBO (Barium Beta Borate) crystal. This result indicates that Boc-pNPhepNPhe dipeptide is a promising nonlinear optical dipeptide, envisioning that some nonlinear optical coefficients may have magnitudes one or two orders of magnitude higher than the effective coefficient measured.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, S1: TGA and DSC Analysis; S2: Crystal data; Figure S1: DSC and TGA spectra; Table S2.1: Atomic coordinates; Table S2.2: Anisotropic displacement parameters; Table S2.3: Bond lengths and angles; Table S2.4: Torsion angles.

Author Contributions

Rosa M. F. Baptista and Etelvina de Matos Gomes conceived and coordinated all the work, analysed the results, wrote and edited the manuscript. Michael S. Belsley supervised the experimental non-linear optical work and wrote and edit the manuscript document. M. Cidália R. Castro and Ana. V. Machado carried out the DSC and TGA analyses. Alejandro P. Ayala performed the single crystal X-ray structure determination, Hirshfeld analysis and wrote and edit the manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia through FEDER (European Fund for Regional Development)-COMPETE-QREN-EU (ref. UID/FIS/04650/2013 and UID/FIS/04650/2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve humans or animals.

Acknowledgements

Rosa M. F. Baptista acknowledges for her contract DL57/2016, with reference DL 57/2016/CP1377/CT0064 (DOI:10.54499/DL57/2016/CP1377/CT0064). The authors acknowledge Cesar Bernardo for collecting the nonlinear optical data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Aggregate Nanostructures of Organic Molecular Materials. Accounts Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, O.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Levy-Sakin, M.; Grunwald, A.; Liebes-Peer, Y.; Bachar, M.; Buzhansky, L.; Mossou, E.; Forsyth, V.T.; Schwartz, T.; et al. Light-emitting self-assembled peptide nucleic acids exhibit both stacking interactions and Watson–Crick base pairing. Nature Nanotech. 2015, 10, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apter, B.; Lapshina, N.; Handelman, A.; Fainberg, B.D.; Rosenman, G. Peptide Nanophotonics: From Optical Waveguiding to Precise Medicine and Multifunctional Biochips. Small 2018, 14, 1801147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariga, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Mori, T.; Takeya, J.; Shrestha, L.K.; Hill, J.P. Self-assembly as a key player for materials nanoarchitectonics. Sci. technol. adv. material 2019, 20, 51–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadiri, M.R. Self-Assembled Nanoscale Tubular Ensembles. Adv. Mater. 1995, 7, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilead, S.; Gazit, E. Self-organization of short peptide fragments: From amyloid fibrils to nanoscale supramolecular assemblies. Supramol. Chem. 2005, 17, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbitz, C. Hydrophobic dipeptides: the final piece in the puzzle. Acta Crystallogr. B 2018, 74, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbitz, C.H. Nanotube formation by hydrophobic dipeptides. Chem.-Eur. J. 2001, 7, 5153–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, T.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Park, J.S.; Choi, J.; Churchill, D.C.; Kim, S.O.; Ihee, H. Role of Water in Directing Diphenylalanine Assembly into Nanotubes and Nanowires. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jia, Y.; Dai, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Controlled Rod Nanostructured Assembly of Diphenylalanine and Their Optical Waveguide Properties. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2689–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Gazit, E. The physical properties of supramolecular peptide assemblies: from building block association to technological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6881–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allafchian, A.R.; Moini, E.; Mirahmadi-Zare, S.Z. Flower-Like Self-Assembly of Diphenylalanine for Electrochemical Human Growth Hormone Biosensor. IEEE Sensors J. 2018, 18, 8979–8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, T.; Knotts, G.; Laudari, A.; Bianchi, R.C.; Alves, W.A.; Guha, S. Bioinspired Peptide Nanostructures for Organic Field-Effect Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014, 6, 21408–21415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kol, N.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Barlam, D.; Shneck, R.Z.; Gazit, E.; Rousso, I. Self-assembled peptide nanotubes are uniquely rigid bioinspired supramolecular structures. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelman, A.; Lavrov, S.; Kudryavtsev, A.; Khatchatouriants, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Mishina, E.; Rosenman, G. Nonlinear Optical Bioinspired Peptide Nanostructures. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2013, 1, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakov, D.; de Matos Gomes, E.; Belsley, M.S.; Almeida, B.; Cerca, N. Strong enhancement of second harmonic generation in 2-methyl-4-nitroaniline nanofibers. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 4978–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Gazit, E. Controlled patterning of peptide nanotubes and nanospheres using inkjet printing technology. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Kol, N.; Yanai, I.; Barlam, D.; Shneck, R.Z.; Gazit, E.; Rousso, I. Self-Assembled Organic Nanostructures with Metallic-Like Stiffness. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9939–9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Fan, Z.; Sun, L.; Makam, P.; Tian, Z.; Ruegsegger, M.; Shaham-Niv, S.; Hansford, D.; Aizen, R.; Pan, Z.; et al. Quantum confined peptide assemblies with tunable visible to near-infrared spectral range. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdursky, N.; Molotskii, M.; Aronov, D.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Gazit, E.; Rosenman, G. Blue Luminescence Based on Quantum Confinement at Peptide Nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3111–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.M.F.; de Matos Gomes, E.; Raposo, M.M.M.; Costa, S.P.G.; Lopes, P.E.; Almeida, B.; Belsley, M.S. Self-assembly of dipeptide Boc-diphenylalanine nanotubes inside electrospun polymeric fibers with strong piezoelectric response. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, R.M.F.; Lopes, P.E.; Rodrigues, A.R.O.; Cerca, N.; Belsley, M.S.; de Matos Gomes, E. Self-assembly of Boc-p-nitro-l-phenylalanyl-p-nitro-l-phenylalanine and Boc-l-phenylalanyl-l-tyrosine in solution and into piezoelectric electrospun fibers. Materials Adv. 2022, 3, 2934–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker, A.X.S.I. APEX4 suite, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2021.

- Bruker, A.X.S.I. SAINT+ Data Reduction Software, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2019.

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr.. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: from visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, D. FinalCif, 2023.

- Baptista, R.M.F.; Gomes, C.S.B.; Silva, B.; Oliveira, J.; Almeida, B.; Castro, C.; Rodrigues, P.V.; Machado, A.; Freitas, R.B.; Rodrigues, M.J.L.F.; et al. A Polymorph of Dipeptide Halide Glycyl-L-Alanine Hydroiodide Monohydrate: Crystal Structure, Optical Second Harmonic Generation, Piezoelectricity and Pyroelectricity. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, I.J.; Cole, J.C.; Kessler, M.; Luo, J.; Motherwell, W.D.; Purkis, L.H.; Smith, B.R.; Taylor, R.; Cooper, R.I.; Harris, S.E.; et al. Retrieval of crystallographically-derived molecular geometry information. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, P.R.; Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer: a program for Hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.d.C.; Tenorio Clavijo, J.C.; Alvarez, N.; Ellena, J.; Ayala, A.P. Novel Solid Solution of the Antiretroviral Drugs Lamivudine and Emtricitabine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 3441–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago de Oliveira, Y.; Saraiva Costa, W.; Ferreira Borges, P.; Silmara Alves de Santana, M.; Ayala, A.P. The design of novel metronidazole benzoate structures: exploring stoichiometric diversity. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2019, 75, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spackman, M.A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2009, 11, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, M. A comprehensive optical second harmonic generation study of the non-centrosymmetric character of biological structures. J. Biol. Phys. 1978, 6, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Physical properties of crystals : their representation by tensors and matrices, Repr. paperback ed. ed.; Oxford : Clarendon press: 2004.

- Bernardo, C.R.; Baptista, R.M.F.; de Matos Gomes, E.; Lopes, P.E.; Raposo, M.M.M.; Costa, S.P.G.; Belsley, M.S. Anisotropic PCL nanofibers embedded with nonlinear nanocrystals as strong generators of polarized second harmonic light and piezoelectric currents. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

and

and  . Notably, the characteristic red and blue triangles forming a 'bow-tie' pattern over ring

. Notably, the characteristic red and blue triangles forming a 'bow-tie' pattern over ring  highlight the π–π interactions associated with the dimer stacking of the amide chains (Figure 4 a). Above ring

highlight the π–π interactions associated with the dimer stacking of the amide chains (Figure 4 a). Above ring  , the HS mapping is less defined, displaying two diffuse 'bow-tie' patterns related to two π–π bonds: one associated with the stacking and a stronger interaction (4.7127(15) Å) between rings of different types, which contributes to the packing of the chains. In this region, a red depression indicates the N4–O8⋯π interaction (3.449(3) Å), is also contributing to the alignment of the parallel chains. This latter interaction is observable in the 2DF plot through the frequency of the C–O distances, which exhibit the wing-like pattern commonly associated with C–H⋯π interactions (Figure 4 b). Finally, it is noteworthy that the 2DF plot is dominated by two strong spikes corresponding to O–H distances, highlighting the key role of the carboxylic–carboxylic and amide–amide interactions in forming and stacking the Boc-pNPhepNPhe dimers.

, the HS mapping is less defined, displaying two diffuse 'bow-tie' patterns related to two π–π bonds: one associated with the stacking and a stronger interaction (4.7127(15) Å) between rings of different types, which contributes to the packing of the chains. In this region, a red depression indicates the N4–O8⋯π interaction (3.449(3) Å), is also contributing to the alignment of the parallel chains. This latter interaction is observable in the 2DF plot through the frequency of the C–O distances, which exhibit the wing-like pattern commonly associated with C–H⋯π interactions (Figure 4 b). Finally, it is noteworthy that the 2DF plot is dominated by two strong spikes corresponding to O–H distances, highlighting the key role of the carboxylic–carboxylic and amide–amide interactions in forming and stacking the Boc-pNPhepNPhe dimers.

and

and  highlighting regions over the aromatic rings. (b) Corresponding 2D fingerprint plot; the colour coding of distance pair frequencies includes reciprocal contacts.

highlighting regions over the aromatic rings. (b) Corresponding 2D fingerprint plot; the colour coding of distance pair frequencies includes reciprocal contacts.

and

and  highlighting regions over the aromatic rings. (b) Corresponding 2D fingerprint plot; the colour coding of distance pair frequencies includes reciprocal contacts.

highlighting regions over the aromatic rings. (b) Corresponding 2D fingerprint plot; the colour coding of distance pair frequencies includes reciprocal contacts.