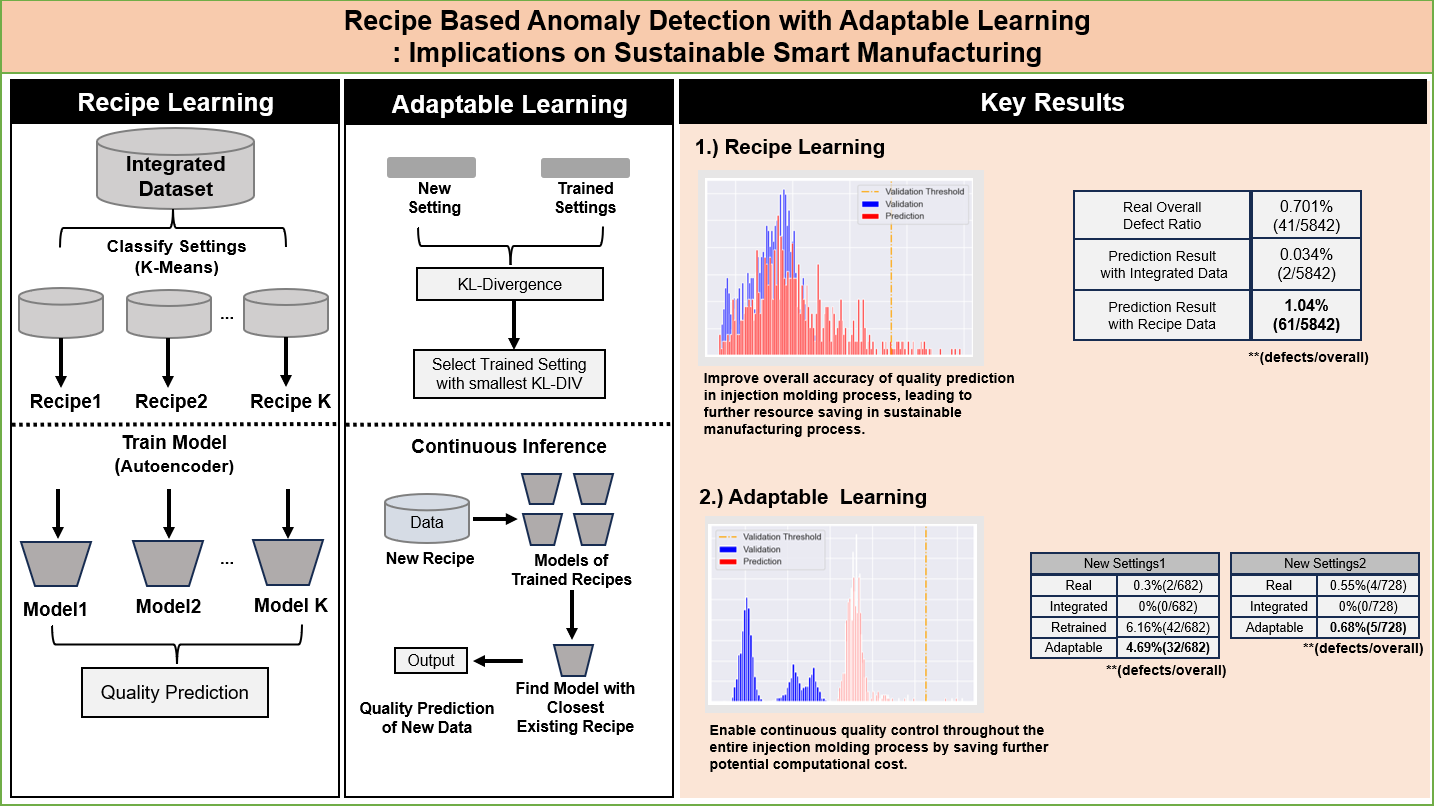

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Industrialization plays a critical role in solving key challenges for maintaining viability by introducing cutting-edge technologies in manufacturing. Recently, many industries are accelerating the application of Industry 4.0 to improve quality control and customization efficiency, and expect benefits such as increased production speed, reduced manufacturing costs, and reduced environmental impact. However, many industries are facing difficulties in efficiently adopting cutting-edge technologies due to financial, regulatory, and organizational management issues. Nevertheless, the future impact of Industry 4.0 on the manufacturing ecosystem is inevitable, and this has led to active research and experiments on the possibility of manufacturing innovation [

1,

2].

In particular, the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) is attracting attention as a key element of manufacturing process innovation in Industry 4.0. AI optimizes data-based decision-making through techniques such as machine learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning, and enables efficient predictive engineering and condition monitoring, thereby enhancing the sustainability and flexibility of manufacturing processes. However, since each manufacturing process has different characteristics of product development, it is important to carefully explore the data characteristics and apply the optimal algorithm.

In addition, research results are also showing that the development of AI in the manufacturing sector can solve environmental problems [

3,

4]. In other words, if manufacturing AI is continuously developed, it is expected to efficiently contribute to society in various ways.

Many studies have shown that the application of manufacturing AI can lead to the advancement of the industry and this is a task that must continue for development in the future [

5,

6,

7]. However, despite the technological advancement of hardware and software, the use of AI solutions in the manufacturing sector faces many limitations, such as scalability, and it is said that much research is still needed [

8].

1.2. Issue

In the field of injection molding, the datasets used in research often do not sufficiently reflect the characteristics of the entire product development process. The datasets generally have a balanced ratio of results for normal and defect qualities. But in actual industrial sites, there is a significant lack of defective data, making it difficult to build an AI model that takes this imbalance into account [

9]. In addition, labeling the status of products on a 1:1 product basis is very important in building AI [

10]. However, the injection molding process has difficulty of performing real time quality inspection throughout the process of every product. So products are generally collected in batches and quality evaluation is done by the count of defective products per each batch. This method makes it difficult to determine whether the characteristics of a each data indicates a normal or defect quality. And if there is a lack of defective data, application of AI is also limited.

In addition, there are results in the field of injection molding that the setting values in product development process are frequently changed, which makes training the data more complicated [

11].If the data settings change, the data itself loses its normality, and the more frequently the settings change, the more complex the data becomes. This makes it difficult to actually build and apply AI.

1.3. Our Idea

This paper propose a new framework for sustainable manufacturing specialized in the injection molding process. By utilizing the process characteristics with few defects, we aim to build an Anomaly Detection model that learns only good data in a batch process and detect actual defects throughout the remaining data. Also, in order to reflect the frequent changes of setting values during product development process, we introduce the ’Recipe-based learning’ approach. A ’recipe’ is defined as a unique set of setting values that is manipulated throughout process. If even one value is changed from a set of multiple settings, it is considered as a new recipe. With this concept, Recipe-based learning means a method of classifying the dataset by each recipe and training its model. Here, we aim to present an approach that can optimize the setting parameters and anomaly detection models of the injection molding process. With further extension, we introduce the ’Adaptable-learning’ approach. Here, we aim to directly predict new data with unseen settings by using trained models of the closest recipe. For the experiment, we used an injection molding data set collected from a private company in South Korea.

1.4. Contributions

Optimization in Defect Detection: This paper advances the field of injection molding by focusing on AI-driven modeling to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of defect detection, aiming to optimize manufacturing quality and process reliability.

Reduced training time: Since additional learning for new data becomes unnecessary, the required learning time is reduced and the maintenance period of the product life cycle can be extended.

Securing corporate competitiveness: By reducing the cost of quality inspection due to advanced defect detection, the company can secure its own quality competitiveness.

Reduction of resource waste: When modeling is performed for each individual setting, optimizing model parameters during training process becomes more simple due to distinguishable data characteristics. This reduces the cost of inference. This is also held with additionally collected data which reduces cost of retraining models.. Both aspects can be implied as the reduction of resource waste and lead to eco-friendly product yield.

The paper is structured to provide a clear progression from foundational concepts through to experimental validation and future implications.

Section 2 provides context for our approach by reviewing the evolution of injection molding technology and recent AI advancements in this area, emphasizing how our method builds upon and improves existing techniques.

Section 3 details the algorithms and methodology we use to enhance defect detection accuracy, demonstrating how our approach impacts production efficiency. In

Section 4, experimental data showcases our method’s real-world effectiveness, significantly outperforming traditional models in defect detection accuracy. The Discussion section interprets these results, highlighting the potential for AI-driven defect detection to improve sustainability and resource efficiency in manufacturing. Finally, the Conclusion advocates for the targeted use of AI in manufacturing automation and proposes future research paths that align with sustainable and resource-efficient practices.

2. Literature Review

The injection molding industry has made great strides over time in leveraging AI.

2.1. Initial Experimentation and Predictive Modeling (Early 2000s)

Early AI implementations in injection molding aimed at predictive maintenance and process optimization, often using basic machine learning algorithms to forecast equipment failures and adjust parameters based on historical data. However, these systems struggled with data limitations, as molding processes are highly complex and sensitive to subtle fluctuations in conditions. This made prediction accuracy inconsistent and dependent on operator expertise to validate predictions, limiting scalability in complex production environments [

12].

2.2. Integration with Industry 4.0 and Real-Time Monitoring (Mid-2010s)

With the onset of Industry 4.0, AI’s role in injection molding expanded to include real-time data monitoring and adaptive process controls. By using IoT sensors and more advanced machine learning models, manufacturers began adjusting molding parameters on the fly, significantly enhancing efficiency and reducing defect rates. Yet, challenges remained, particularly with data compatibility across different machine systems and the difficulty in achieving “zero-defect” manufacturing due to high variability in material and environmental factors [

13].

2.3. Advanced Quality Prediction and Zero-Defect Ambitions (2020s)

More recent advancements focus on achieving high quality and zero-defect production through complex AI models like neural networks and human-in-the-loop systems. These allow AI to refine parameters in real-time, reducing waste and maintaining consistency. However, these systems demand substantial computational resources and skilled data scientists to manage and interpret results, creating a high entry barrier for smaller manufacturers. Additionally, the effectiveness of these systems is often limited by variability in data quality and completeness, hindering universal application [

9].

Over time, the importance of AI in the injection molding field is increasing day by day, and its accuracy is also improving. However, due to frequent changes in the set values, it is very difficult to utilize AI [

11]. In addition, deploying AI for defect detection and quality prediction in the injection molding industry has difficulty in learning effective models due to the very small number of defect data. This lack of defect samples limits the ability of AI models to generalize and accurately predict rare defects [

14].

2.4. Similar Studies

In fact, in the injection process with the characteristics of a batch unit, Autoencoder has been utilized for monitoring, quality prediction, etc [

11,

15]. However, it is said that there are many difficulties in practical application, citing limitations such as a decrease in accuracy due to changes in new recipes (setting values) [

11].

2.5. This Work

As explained above, due to the nature of the injection process, there is no actual individual labeling and only the defect ratio in simple cavity unit production can be known, so we used the existing Autoencoder method that learns the distribution of good products and detects defects by utilizing only the data of all good products in the cavity or batch production unit [

11,

15].

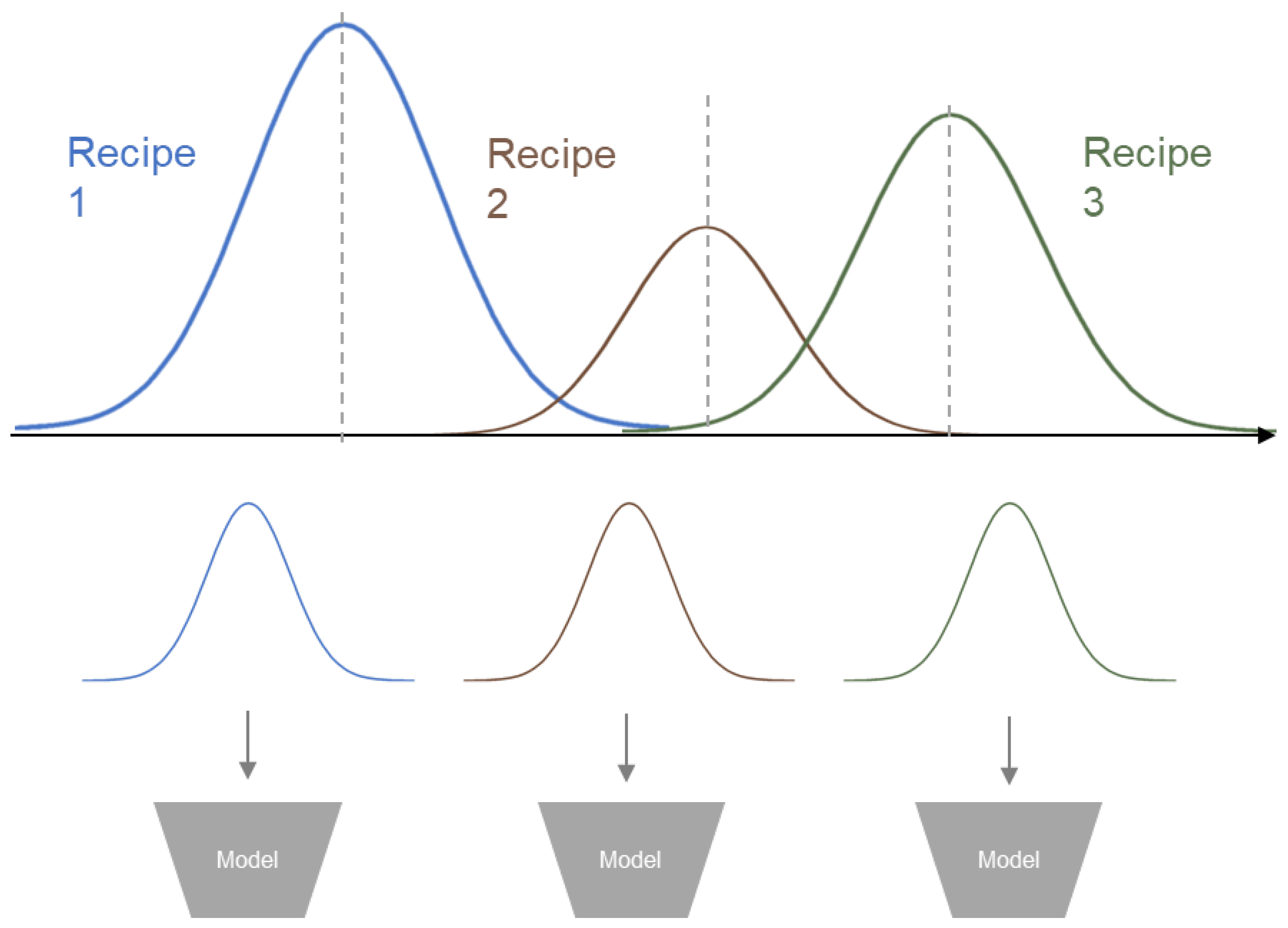

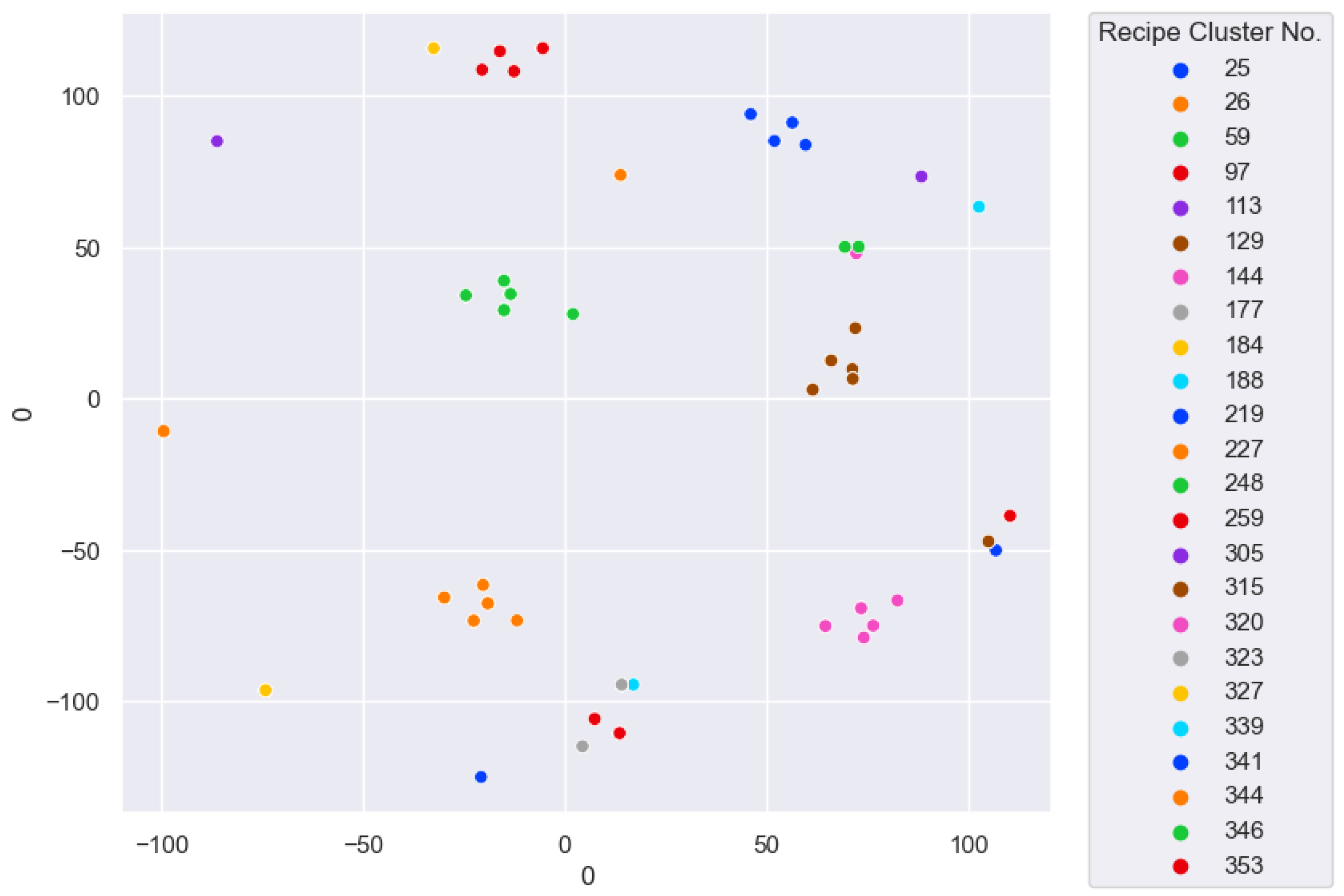

In this paper, we propose a method to secure data normality for more sophisticated modeling and a methodology to meaningfully predict new types of data. First, we propose a method to learn by separating the settings. If the setting values are classified, the regularity of the training data set can be secured as an example in

Figure 1. If modeling is performed based on this regularity, higher performance of quality inspection can be maintained.

In addition, in order to efficiently verify when a new type of data is input, we propose a method of making predictions for new data by utilizing a training model most similar to the new data from the existing Recipe training unit model by using an algorithm that identifies the distribution of the new data.

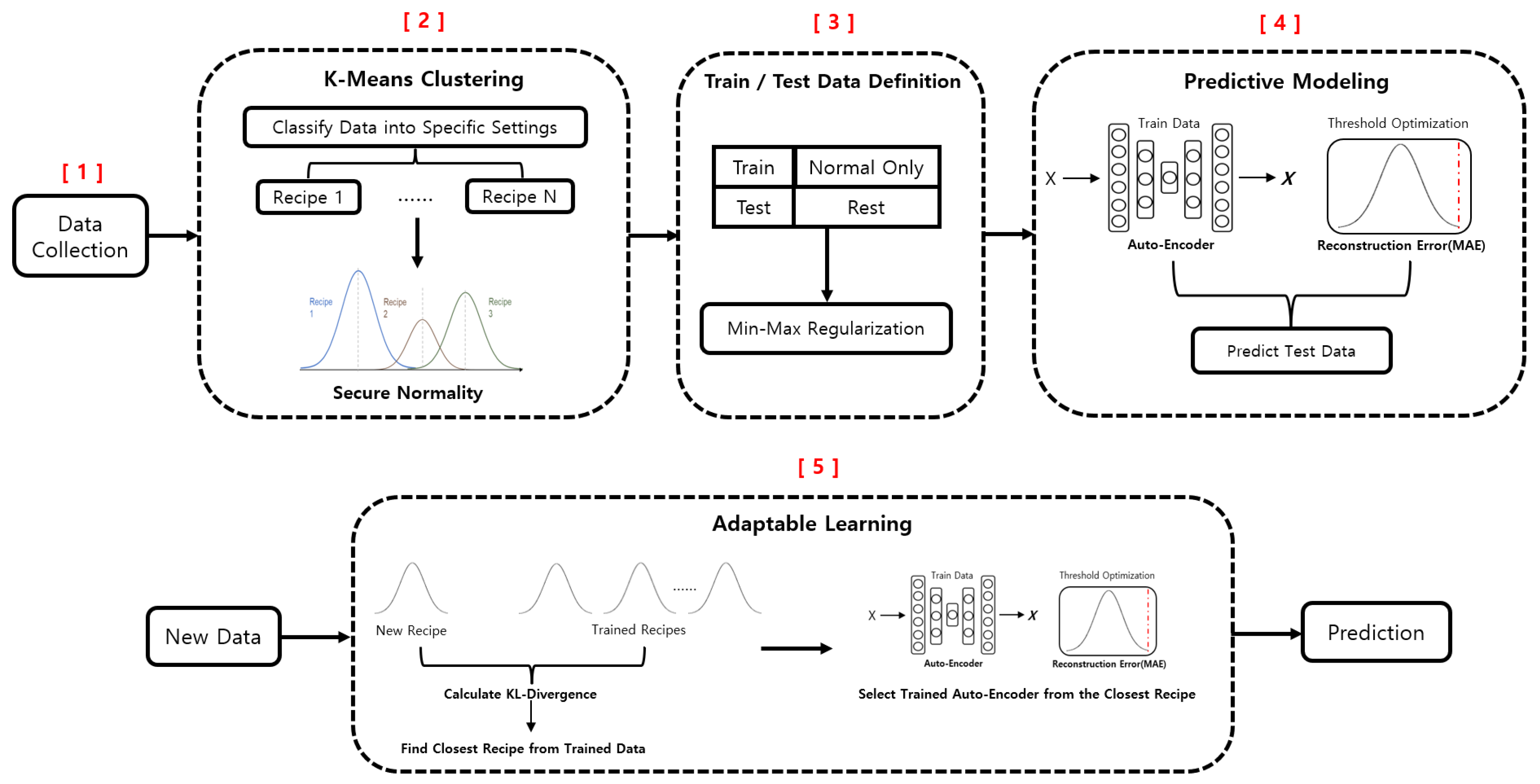

3. Methodology

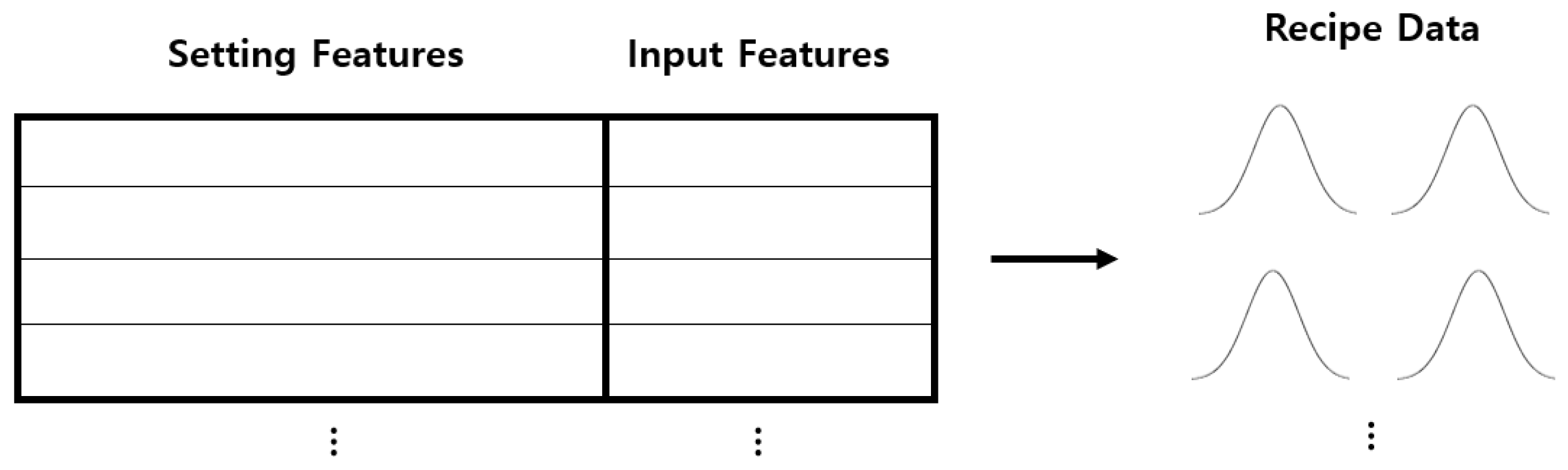

In this section, we introduce our proposed architecture for implementing anomaly detection focusing on data with a lack of individual labeling results consisting of setting values. The general architecture is described in

Figure 2. For a brief introduction, the overall description of the collected dataset for experimental analysis is first explained. Second, the K-Means clustering algorithm [

16] is described focused on securing data normality with setting-based separation. Third, the train and test data are defined for anomaly detection. Only normal data are trained, and the rest are used for prediction. Data regularization with min-max scaling is further done before the modeling process. Fourth, predictive modeling is based on the Autoencoder [

17] model. Anomalies beyond the optimized threshold of reconstruction errors are to be treated as anomalies. Finally for adaptable learning, the KL-Divergence [

18] is used to find the closest data among trained recipes, compared to new data which contain untrained settings. Then, with the trained AutoEncoder based on the closest trained recipe, new data are becomes directly predictable.

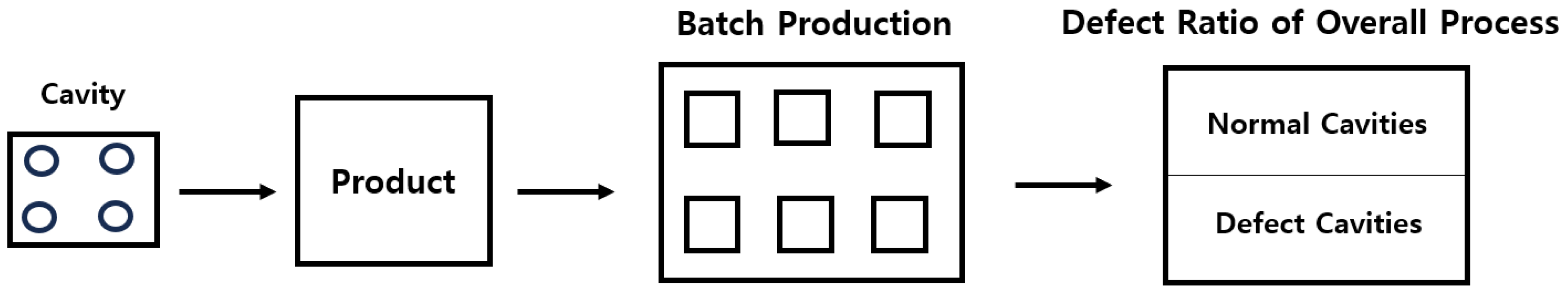

3.1. Data Collection

The injection molding dataset for the experiment is based on a procedure measured in a batch described in

Figure 3. First, a product consists of a single or multi- cavity mold. For each process, a single-cavity mold yields one product, and a multi-cavity mold yields sub-products. For example, if a 4 cavity mold product consists of cavities which 3 are normal and 1 is defect, the defect ratio of this product is 25 percent. Now, these cavity-based products are assigned to a specific batch. In such process, quality inspection is usually not performed for each product. Instead, the overall defect ratio is known based on the count of good and bad cavities. Since individual labeling is absent, it is difficult to directly apply AI methods of classification or anomaly detection. Furthermore, if settings are changed multiple times throughout the process, even a dataset with a single item-code consists of multiple distributions. In this case, data preprocessing based on a domain-specific approach is to be required.

The description of the experiment dataset is as follows.

Collected data size is D with N features.

The dataset consists of F facilities and P products.

Each product consists of C cavities.

S setting features are used for classifying data into recipes.

I input features are used for building Autoencoder models.

The rest of the features include information such as facility and product code, process date, etc. And the target feature for prediction is the overall defect ratio of good and bad cavities in the batch process.

3.2. Recipe Separation

The prior objective of our work is comparing the prediction results of trained models based on setting-based classified data which secures normality and the original data. Considering the change of distributions throughout different setting values, our work aims to improve the prediction accuracy of defect cavities.

In order to classify data into recipes based on specific settings, the K-Means clustering algorithm [

16] is applied to the original product data.

The K-Means Clustering is an unsupervised algorithm for grouping data of similar characteristics based on distance measure. The process is as follows.

First, the number of clusters K is decided for how many clusters the data should be divided into.

Initial centroids for each cluster are given. Data close to each centroid are assigned to each cluster with distance-based metrics such as Euclidean-Distance.

Initial centroids move to the center of the data points of each assigned cluster. This process is repeated until every data are assigned to clusters and centroids are finally adjusted.

An example of the K-Means result is shown in

Figure 4.

Next, The process of applying K-Means is as follows.

Among dataset size of D, select data with only N setting features.

From the selected data, find C unique combinations of setting features.

Set the parameter n clusters as K which is the same number of C.

Apply standard-scaling method to unify different measures of setting features.

Train K-Means Clustering with final data size of d rows and N features

Return to the original data size D and predict each data based on the setting features.

Throughout prediction, designate the cluster number from 1 to K for each data.

Define the final cluster numbers as setting parameter-based recipes.

When new data is collected, the cluster(recipe) number of setting features are predicted with the trained K-Means.

The outline of K-Means application is shown in

Figure 5.

3.3. Train/Test Data Organization

As mentioned in

Section 3.1, data of such process lack individual labeling results. Rather, only the overall defect ratios comprising the count of good and bad cavities are known. For anomaly detection, batch process which have no defects(normal quality) can first be defined as the train dataset. To prevent overfitting issues of prediction models, 90% are actually used for training and 10% for validation. Finally, the normal data itself(integrated data) and the classified recipes are then used for training models.

Then, batch process with existing defects (defect ratio > 0.0%) are defined as the test dataset. For appropriate prediction, additional preprocessing is done in two situations.

Suppose a batch process consists of multiple setting-based recipes which also exist in the train data. Although it seems appropriate for prediction, there is a setback. Since only the overall defect ratio per batch process is known, it is inappropriate to compare predicted defect ratios of multiple recipes and the existing ratio. In other words, in a batch process, defect ratio per each recipe is untrackable. Accordingly, batch process which have one unique setting recipe are left in the test data.

Suppose the test data consists of an unseen recipe information. In this case, only partial prediction can be done leading to incomplete quality measurement of the batch process.

Finally, the preprocessed test data itself(integrated data) and the classified recipes are then used for prediction.

3.4. Min-Max Regularization

Before building prediction models, a min-max scaling method which transforms the range of inputs from 0 to 1 is applied to the input features [

19]. In deep-learning methods, regularization with scaling is vital for properly training data. Especially, it can mitigate input bias [

20], gradient vanishing or exploding [

21], covariance shift [

22], and exponential convergence of training loss [

23]. Scaling is first done based on the train dataset. Then, features of validation and test data are regularized based on the train dataset.

3.5. Predictive Modeling

3.5.1. Autoencoder Application

To perform anomaly detection with train and test data defined in

Section 3.3, the Autoencoder method is applied as the main prediction model in our work.

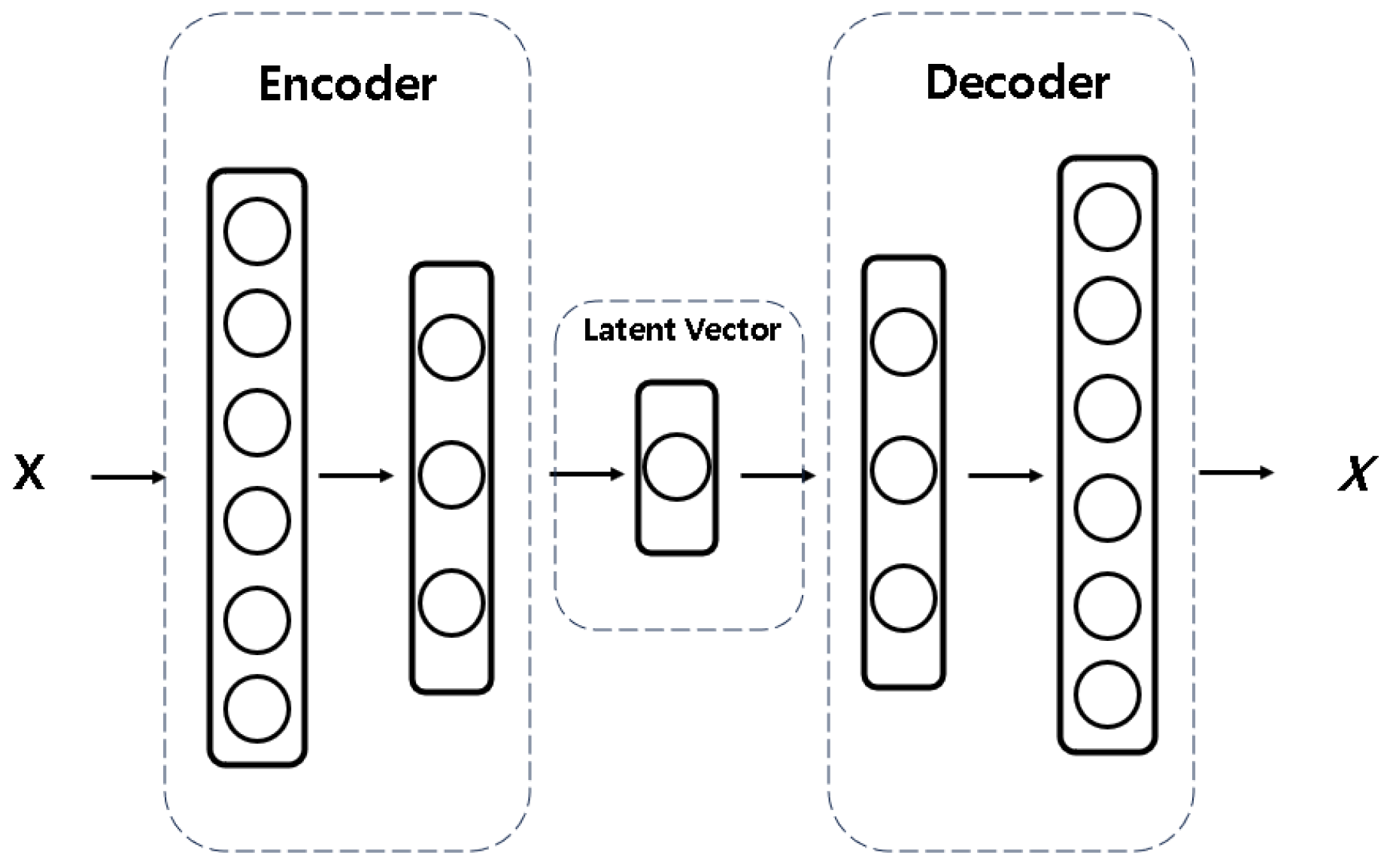

The main function of Autoencoder is reconstructing the inputs into similar outputs throughout a symmetric architecture [

17,28].

Inputs are compressed through the encoder layer into the latent vector.

In the latent vector, non-linear correlations between features are captured which can effectively learn important components of inputs.

Throughout the latent vector, reconstructed outputs are predicted with the decoder layer.

Inputs for training Autoencoders of the recipes and the entire normal data(integrated data) are the I input features.

Since the main objective of our work is applying AI in such manufacturing process which have barely been used for analysis in other related works, it is closer to a data-driven approach [

24]. This is why Autoencoder of a fundamental structure like

Figure 6 is used rather than applying Autoencoder variants [

25] which focus on improving model performance which is more of a model-driven approach [

26,

27].

3.5.2. Threshold Optimization with Evaluation Metrics

After training the Autoencoder models, the loss value of reconstruction errors between the inputs and predicted outputs is calculated using mean absolute error. Among several metrics, The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is selected to see a more intuitive difference between the inputs and outputs. The MAE function calculates the mean value of absolute errors between the given inputs and predicted output values [29]. From the equation , where n is the train data size, is the input , and is the reconstructed output [30].

Furthermore, thresholds for anomaly detection are based on the maximum MAE value of the reconstruction error of the validation normal data. If the MAE values of test data exceed the threshold, it is predicted as anomaly. The application is to be performed in

Section 4.5.2.

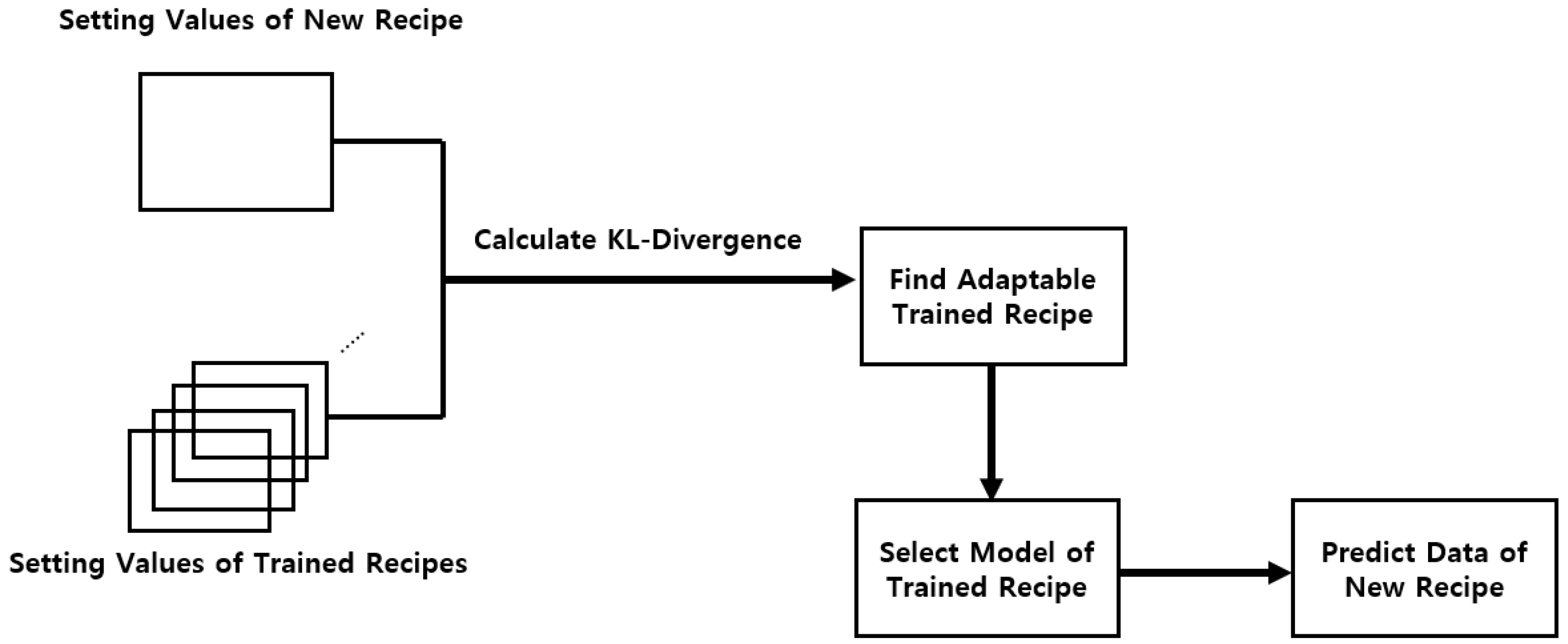

3.6. Adaptable Learning

When new data of untrained recipe settings are collected, additional training is usually required. However, if it is available to define the model of trained recipe with the closest distribution compared to the new settings, direct prediction becomes available. In our work, this is defined as adaptable learning.

First, KL-Divergence is applied for calculating the difference of distributions among setting values. The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence is a statistical measure which quantifies the distance between two probability distributions. From the equation below, [

18], the definition of distribution P and Q in our work is explained as follows.

P is defined as each setting feature of the trained recipe.

Q is defined as each setting feature of new recipe.

The range of KL-Divergence is from zero to infinity. If the divergence is lower, the distributions are interpreted to be more similar.

As a result, the goal is to make sure to find Q which can properly infer P.

Next, The process of applying KL-Divergence is as follows.

Select recipes R,...., R+K of the trained dataset.

Define recipes

r,...., r+k of the new dataset. (Recipe numbers are predicted by the trained K-Means model in

Section 3.2.)

Select N setting features per each trained recipe and new recipe.

Calculate the KL-Divergence value of each setting feature between the new and trained recipes.

Calculate the sum of the calculated KL-Divergence values.

Select the trained recipe with the lowest KL-Divergence value compared to the new recipe.

Select model of trained recipe and predict data of new recipe.

Define I input features used for prediction.

The outline of KL-Divergence is shown in

Figure 7.

4. Experiment Setup

4.1. Data Collection

The injection molding dataset used in our work is collected from a private manufacturing company in South Korea. Referred to

Section 3.1, inputs are defined as

D = 432089 ,

N = 132,

F = 4,

P = 14,

C = 1,

S = 76,

I = 6. For further information, data with the size of 432098 with 132 features consist of 14 products manufactured in 4 facilities. Every product is based on a single-cavity. 76 setting features are used for numbering recipes and 6 input features are finally used for anomaly detection.

4.2. Recipe Separation

The dataset is first classified via unique setting parameters. Then, inputs following the procedure of

Section 3.2 are defined as

D=432089 ,

N=76,

C=366,

K =366,

d=366.

An example of understanding the dataset is described in

Table 1. First, the batch number 20231214 is the date when process was held. The batch process with specific settings defined as recipe number 10 results in approximately 1.37% defect ratio of cavity-based products.

4.3. Select Experiment Data

From the complete dataset, we chose the most appropriate subset to perform our proposed method based on the following order.

Remove facility data which does not have any defect.

Select data from a specific facility where most defect ratios exist.

Select data of a specific product with the largest size.

The specified dataset now have data size of 26577 and 132 features. 36 setting based recipes with secured normality exist throughout 57 batch process from 2023-12-14 to 2024-07-17. And the descriptive statistics of 6 input features is shown in

Table 2.

4.4. Train/Test Data Organization

Referred to

Section 3.3, there remain 6 recipes from the experiment dataset. Descriptions of the train and test data are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In case of recipe 4,5,6, only training is available since no test data with the identical recipes exist. In this case, prediction can only be done if new data of same recipes are actually collected. Validation data are then defined. Then, min-max regularization is done referred to

Section 3.4. With final organization of the train and test data, prediction of integrated and recipe-based models follow the next step.

4.5. Results

4.5.1. Autoencoder Configuration

The information of the trained Autoencoders are described in

Table 5. Stacked Autoencoders [31] with the best weights [32] throughout the epochs of training process are defined as the basic structure. To maximize performance, we selected optimal the parameters per each model.

4.5.2. Threshold Optimization

To define optimal thresholds for anomaly detection, the validation data mentioned in

Section 3.3 and

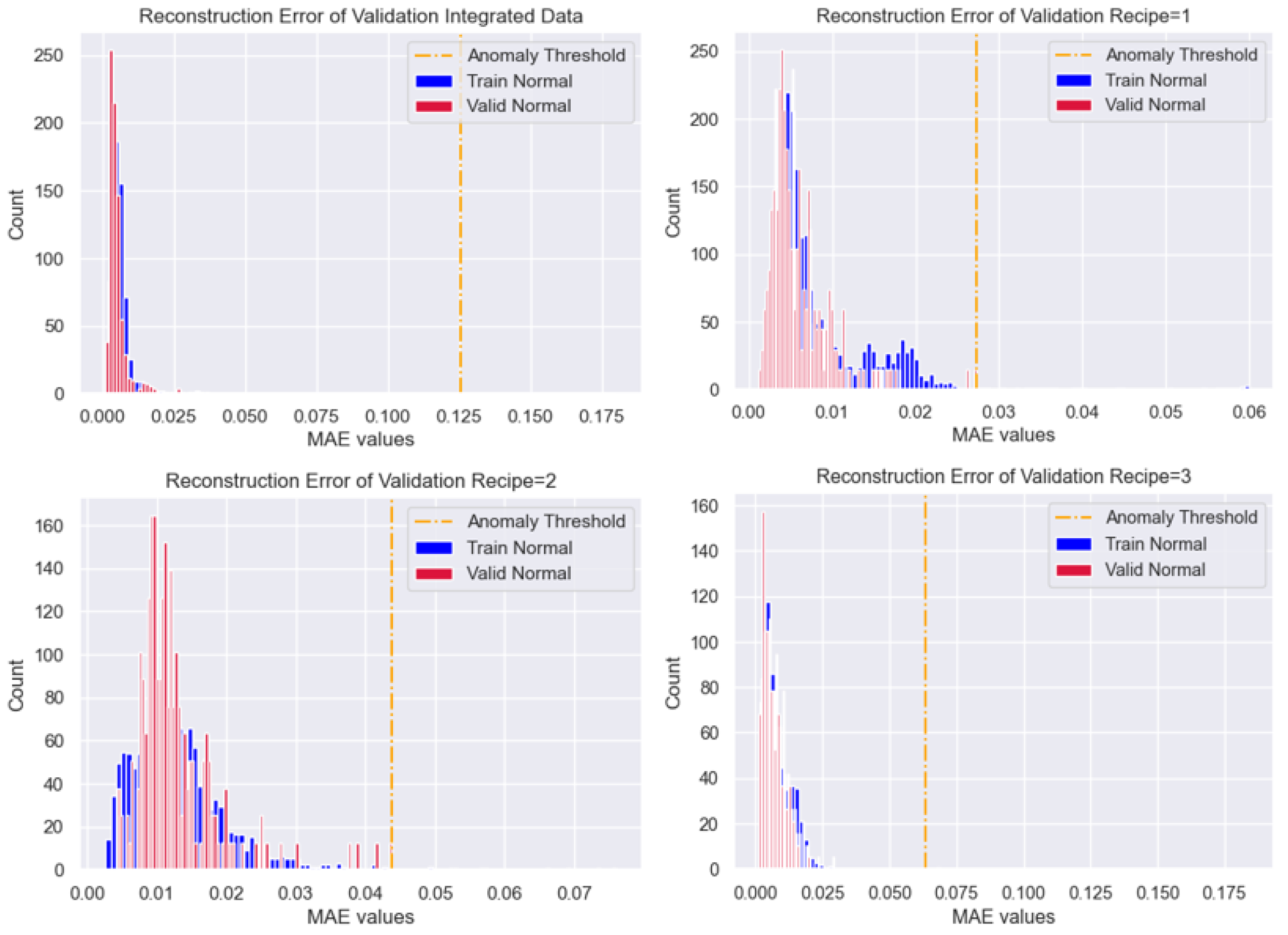

Section 4.4 are first predicted with each Autoencoder. The distribution of reconstruction errors are shown in

Figure 8. The optimal thresholds are selected based on the the maximum MAE values referred to

Section 3.5.2. Instead of calculating thresholds via statistical approach, the maximum MAE value is selected to secure the utmost objectivity. The calculated thresholds are described in

Table 6.

4.5.3. Prediction Comparisons

With the defined thresholds, prediction results based on the integrated and recipe-based models are described in

Table 7. From the table, each information includes the processed date of the batch with the existing and predicted defects. For recipe-based prediction, the specific number of the recipe is also shown. For example, in the first information, there are 5 existing defects among 971 cavities, 1 predicted defect from the integrated-based model and 6 predicted defects from the recipe-based model. The recipe number based on the specific settings of the trained model and test data is 3.

Compared to the total amount of 41 existing defects out of 5842 cavities(0.701%), the integrated model predicted only 2(0.034%) defects, while the recipe-based models predicted 61 defects(1.04%). In the perspective of accuracy, recipe-based prediction shows approximately more than twice of the integrated-based prediction. Especially in the second and eighth information, the recipe-based models predicted the same number of defects compared to the existing ones. However, none were predicted with the integrated model. This implies the importance of building appropriate prediction models considering the difference of data distributions due to change of settings.

4.6. Adaptable Learning

Referred to

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.6, we used new inputs predicted as recipe number 6 and 7. The characteristics of the new data are as follows.

For recipe 6, there exist process of two unique batches each with no defects(defect ratio=0.0%) and existing defects(defect ratio>0.0%). In other words, the first batch consists of only good cavities and the second consists of both good and bad cavities.

For Recipe 7, there exist process of one unique batch with existing defects.

For both recipes, data which contain defects are predicted with the following approaches.

Find each nearest trained recipe data and its prediction model(AutoEncoder) of recipe number 6 and 7 via KL-Divergence calculation.

Optimize thresholds with validation data.

Predict new data with each selected Autoencoder and the integrated AutoEncoder referred to

Table 5.

Compare prediction results of integrated and recipe-based models.

For the batch process data with no existing defects in recipe 6, it is also used for training a new model. Then, the batch process data with existing defects are predicted. This is held to compare the anomaly detection results of additional training and adaptable learning.

4.6.1. KL-Divergence Calculation

With defined parameters

R=1,

K=2, r=

6, k=

1, N=

76,

I=6 according to

Section 3.6, the calculation results are described in

Table 8. As a result, the closest trained recipe dataset of the new inputs can be both defined as recipe 1.

4.6.2. Data Organization

As

Section 3.5.2 and

Section 4.5.2, threshold optimization is held based on the validation dataset of normal cavities. The validation data for the new inputs are defined in

Table 9. Data are defined by whether batch process from a new data consists only of normal cavities can be known or not.

First, for recipe 6, the first batch(defect ratio=0.0%) is used for validation and the second batch(defect ratio>0.0%) is used for prediction. Second, for recipe 7, normal the validation data is defined as follows.

Based on recipe 1, select the closest data among the remaining recipe 2 and 3.

Parameters according to

Section 3.6 are defined as

R=2,

K=1,

r=1,

k=0,

N=76 ,

I=6.

With KL-Divergence, the closest data of recipe 1 result in recipe 3.

The existing train data of recipe 3 is decided as the validation dataset.

4.6.3. Prediction Comparisons

In

Table 9, thresholds for anomaly detection are optimized via the maximum MAE values of the reconstruction error distributions. Then the adaptable learning procedure is held with the prediction data. The results compared to the integrated model are described in

Table 10. Especially for recipe number 6, the prediction result of additional training is also compared.

While the integrated model without considering unique settings still fails to predict defects as

Section 4.5.3, results based on the adaptable learning process predicted relatively acceptable amount of defects. In recipe number 6, prediction except the integrated model resulted in much more defects compared to the existing ones. Even though, adaptable learning led to a better result than additional training with 10 less predicted anomalies. And in recipe number 7, predicted anomalies with adaptable learning are almost equal to the existing ones. This implies that applying adaptable learning for new data is more effective in the perspective of prediction accuracy and continuity of quality inspection.

5. Discussion

For comparison, both the integrated and recipe models used simple-structured autoencoders in these experiments, and recognizing the importance of hyper-parameter tuning [34–36], this was performed for each model.

When the training results of the integrated model and the model classified by recipe are utilized, the threshold of the recipe model can be set more precisely than that of the integrated model. When this is utilized to classify good and defective products, it can be seen that the defective classification rate for each recipe data is significantly higher than that of the integrated model. This underscores the importance of categorizing data that vary with settings, ensuring the normality of each dataset during training. In other words, it shows that it is very important to train while ensuring the normality of each data by classifying the data that changes according to the setting, like an integrated model, in order to actually connect it to the performance aspect.

Also, in predicting data that has not been previously trained, a KL-Divergence approach to identify the closest recipe distribution further demonstrated higher accuracy in distinguishing defective from non-defective products compared to the integrated model. This method reduces the need for frequent retraining while maintaining high classification performance. The targeted nature of recipe-specific models streamlines data processing, minimizes noise, and improves accuracy by addressing setting-specific variations that integrated models might overlook. Therefore, as these models avoid the broader generalizations required by unified models, both the improvement of defect detection rates and optimization of computational efficiency are enhanced. This adaptability ensures scalability and robustness, particularly for large-scale industrial applications.

An additional approach leveraging fine-tuning thresholds without extensive retraining further emphasizes the potential of setting-specific modeling. By isolating and prioritizing influential features, this method achieves high prediction accuracy while optimizing computational resources. Such advancements highlight the transformative potential of adaptive modeling in dynamically changing industrial environments, enabling leaner, more efficient AI applications.

In sum, the findings demonstrate the efficacy of specialized modeling approaches over traditional unified methods in manufacturing AI. These methods address the variability inherent in operational settings, ensuring enhanced prediction quality and reduced resource demands. The move toward context-driven methodologies represents a significant step forward in developing robust, efficient AI systems for sustainable manufacturing.

6. Conclusions

As AI becomes integral to manufacturing, its role in fostering efficiency and sustainability gains prominence. AI-driven systems can optimize data process, enabling precise defect identification and waste reduction. This focus on quality control not only enhances competitiveness but also supports environmental goals by minimizing resource waste.

When utilizing AI in actual manufacturing sites, environmental benefits must also be considered. AI’s benefits for environmental sustainability have been clearly demonstrated in small-scale project initiatives and hypothetical or qualitative tests [37–39]. However, to achieve a meaningful impact from the perspective of AI and sustainability, it is essential not only to identify and improve environmental factors but also to prioritize factors that are competitive and beneficial to business [40,41].

Compared to existing systems, this will present a new recipe-unit paradigm focused on reduce of waste, model compression, and improved accuracy. This thereby leads to reducing the cost of real-time inference. Also, it will also promote research in new directions and engage in continuous development. By utilizing these AI advantages, this study can emphasize that in the area of environmental cost reduction which is a factor that has recently emerged, waste can also be reduced .

The development of optimized, setting-specific datasets allows for the deployment of simpler, less resource-intensive models without compromising accuracy. This streamlined approach lowers computational costs and fosters broader adoption of sustainable AI practices across industries. Incorporating domain-specific knowledge further refines these models, enhancing their interpretability and predictive capabilities while promoting proactive quality control.

However, in reality of the manufacturing process environment, only a few batches of product data can be accurately identified for good products, so semi-supervised learning must be utilized, and due to the characteristics of the learning, the classification accuracy is not maintained at a very high level.

Future research should focus on further integrating domain expertise, advanced feature selection techniques, and optimized data practices based on the recipe-level analysis outlined in this paper. Specifically, utilizing domain knowledge to identify key variables that influence the distinction between high- and low-quality products, combined with targeted feature engineering, can enhance predictive accuracy. These advancements will ensure that AI systems remain efficient, precise, and sustainable, driving innovation across various industries while effectively addressing critical environmental challenges.

References

- Cioffi, Raffaele, et al. "Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in smart production: Progress, trends, and directions." Sustainability 12.2 (2020): 492.

- Tseng, Ming-Lang, et al. "Sustainable industrial and operation engineering trends and challenges Toward Industry 4.0: A data driven analysis." Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 38.8 (2021): 581-598.

- Waltersmann, Lara, et al. "Artificial intelligence applications for increasing resource efficiency in manufacturing companies—a comprehensive review." Sustainability 13.12 (2021): 6689. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yixuan, and Shanyue Jin. "Artificial intelligence and carbon emissions in manufacturing firms: The moderating role of green innovation." Processes 11.9 (2023): 2705. [CrossRef]

- Rakholia, Rajnish, et al. "Advancing Manufacturing Through Artificial Intelligence: Current Landscape, Perspectives, Best Practices, Challenges and Future Direction." IEEE Access (2024).

- Peres, Ricardo Silva, et al. "Industrial artificial intelligence in industry 4.0-systematic review, challenges and outlook." IEEE access 8 (2020): 220121-220139.

- Arinez, Jorge F., et al. "Artificial intelligence in advanced manufacturing: Current status and future outlook." Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 142.11 (2020): 110804. [CrossRef]

- Espina-Romero, Lorena, et al. "Challenges and Opportunities in the Implementation of AI in Manufacturing: A Bibliometric Analysis." Sci 6.4 (2024): 60. [CrossRef]

- Rousopoulou, Vaia, et al. "Predictive maintenance for injection molding machines enabled by cognitive analytics for industry 4.0." Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 3 (2020): 578152. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jiawen, et al. "A review on AI for smart manufacturing: Deep learning challenges and solutions." Applied Sciences 12.16 (2022): 8239. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Hail, et al. "Application of machine learning techniques in injection molding quality prediction: Implications on sustainable manufacturing industry." Sustainability 13.8 (2021): 4120. [CrossRef]

- Charest, Meaghan, Ryan Finn, and Rickey Dubay. "Integration of artificial intelligence in an injection molding process for on-line process parameter adjustment." 2018 Annual IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon). IEEE, 2018.

- Silva, Bruno, et al. "Enhance the injection molding quality prediction with artificial intelligence to reach zero-defect manufacturing." Processes 11.1 (2022): 62. [CrossRef]

- Thabtah, Fadi, et al. "Data imbalance in classification: Experimental evaluation." Information Sciences 513 (2020): 429-441. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Ting, et al. "Data driven injection molding process monitoring using sparse auto encoder technique." 2015 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM). IEEE, 2015.

- K. P. Sinaga and M. -S. Yang. "Unsupervised K-Means Clustering Algorithm." IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 80716-80727, 2020.

- Chen, Zhaomin, et al. "Autoencoder-based network anomaly detection." 2018 Wireless telecommunications symposium (WTS). IEEE, 2018.

- F.Perez-Cruz, "Kullback-Leibler divergence estimation of continuous distributions." 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008, pp. 1666-1670.

- Deepa, Bharathi and K. Ramesh. “Epileptic seizure detection using deep learning through min max scaler normalization.” International journal of health sciences (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. C., Bijan B. Misra, and Himansu Sekhar Behera. "Impact of data normalization on stock index forecasting." International Journal of Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management Applications 6 (2014): 13-13.

- S. Al-Abri, T. X. Lin, M. Tao and F. Zhang. "A Derivative-Free Optimization Method With Application to Functions With Exploding and Vanishing Gradients." IEEE Control Systems Letters, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 587-592, April 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Joe H., and William H. Woodall. "Change-point detection of mean vector or covariance matrix shifts using multivariate individual observations." IIE transactions 32.6 (2000): 537-549.

- Song, Yang, Alexander Schwing, and Raquel Urtasun. "Training deep neural networks via direct loss minimization." International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2016.

- Hosen, Mohammed Shahadat, et al. "Data-Driven Decision Making: Advanced Database Systems for Business Intelligence." Nanotechnology Perceptions (2024): 687-704. [CrossRef]

- Berahmand, Kamal, et al. "Autoencoders and their applications in machine learning: a survey." Artificial Intelligence Review 57.2 (2024): 28. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Tianyi, et al. "Deep learning model-driven financial risk prediction and analysis." (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bariah, Lina, and Merouane Debbah. "The interplay of ai and digital twin: Bridging the gap between data-driven and model-driven approaches." IEEE Wireless Communications (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sewak, Mohit, Sanjay K. Sahay, and Hemant Rathore. "An overview of deep learning architecture of deep neural networks and autoencoders." Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 17.1 (2020): 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Hodson, Timothy O. "Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not." Geoscientific Model Development Discussions 2022 (2022): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Givnan, Sean, et al. "Anomaly detection using autoencoder reconstruction upon industrial motors." Sensors 22.9 (2022): 3166. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Miao, et al. "A model-based collaborate filtering algorithm based on stacked AutoEncoder." Neural Computing and Applications (2022): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tong, et al. "High-ratio lossy compression: Exploring the autoencoder to compress scientific data." IEEE Transactions on Big Data 9.1 (2021): 22-36. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jianlong, et al. "Parameter selection of Touzi decomposition and a distribution improved autoencoder for PolSAR image classification." ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 186 (2022): 246-266. [CrossRef]

- Awwad, Ameen, Ghaleb A. Husseini, and Lutfi Albasha. "AI-Aided Robotic Wide-Range Water Quality Monitoring System." Sustainability 16.21 (2024): 9499. [CrossRef]

- Tynchenko, Vadim, et al. "Predicting Tilapia Productivity in Geothermal Ponds: A Genetic Algorithm Approach for Sustainable Aquaculture Practices." Sustainability 16.21 (2024): 9276. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yang, et al. "Ada-XG-CatBoost: A Combined Forecasting Model for Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) Prediction." Sustainability 16.16 (2024): 7203.

- Nañez Alonso, Sergio Luis, et al. "Digitalization, circular economy and environmental sustainability: The application of Artificial Intelligence in the efficient self-management of waste." Sustainability 13.4 (2021): 2092.

- Khakurel, Jayden, et al. "The rise of artificial intelligence under the lens of sustainability." Technologies 6.4 (2018): 100. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Carole-Jean, et al. "Sustainable ai: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities." Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 4 (2022): 795-813.

- Tanveer, Muhammad, Shafiqul Hassan, and Amiya Bhaumik. "Academic policy regarding sustainability and artificial intelligence (AI)." Sustainability 12.22 (2020): 9435. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, Tan, and Federico Cugurullo. "The sustainability of artificial intelligence: An urbanistic viewpoint from the lens of smart and sustainable cities." Sustainability 12.20 (2020): 8548. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).