Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

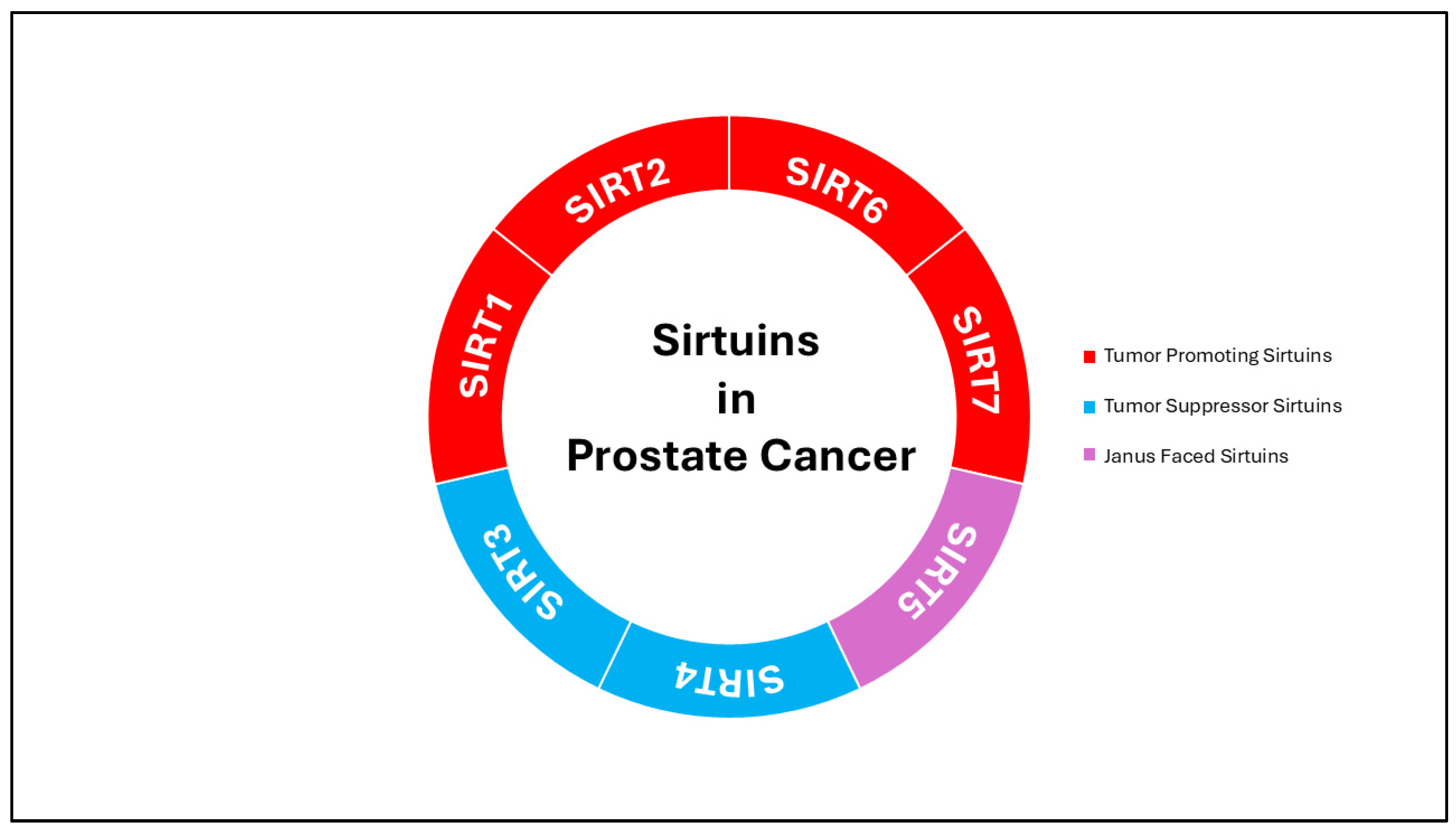

Prostate cancer (PCa) remains a critical global health challenge, with high mortality rates and significant heterogeneity, particularly in advanced stages. While early-stage PCa is often manageable with conventional treatments, metastatic PCa is notoriously resistant, highlighting an urgent need for precise biomarkers and innovative therapeutic strategies. This review focuses on the dualistic roles of sirtuins, a family of NAD+ dependent histone deacetylases, in PCa pathogenesis, dissecting how each sirtuin contributes uniquely to either tumor suppression or progression depending on the cellular context. By exploring each sirtuin’s influence on pathways such as metabolic regulation, chromosomal stability, inflammation and cellular survival, we reveal their multifaceted impact on cancer processes like oxidative stress responses, gene expression and apoptosis. For instance, SIRT1 and SIRT7 often demonstrate oncogenic behavior in PCa, promoting tumor growth and survival, while SIRT3 and SIRT4 are more frequently associated with tumor-suppressive functions, countering cellular proliferation and maintaining metabolic stability. By examining the specific mechanisms through which sirtuins impact PCa, this review emphasizes the potential of sirtuin modulation to bridge existing gaps in managing advanced disease. Ultimately, insights into sirtuins’ regulatory effects could redefine therapeutic paradigms in PCa, fostering precision-based strategies that enhance treatment efficacy and improve clinical outcomes for patients with aggressive PCa.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Structural Variations Among Sirtuins and Their Functional Implications

3. Sirtuins and Prostate Carcinogenesis

3.1. Tumor Promoter Sirtuins

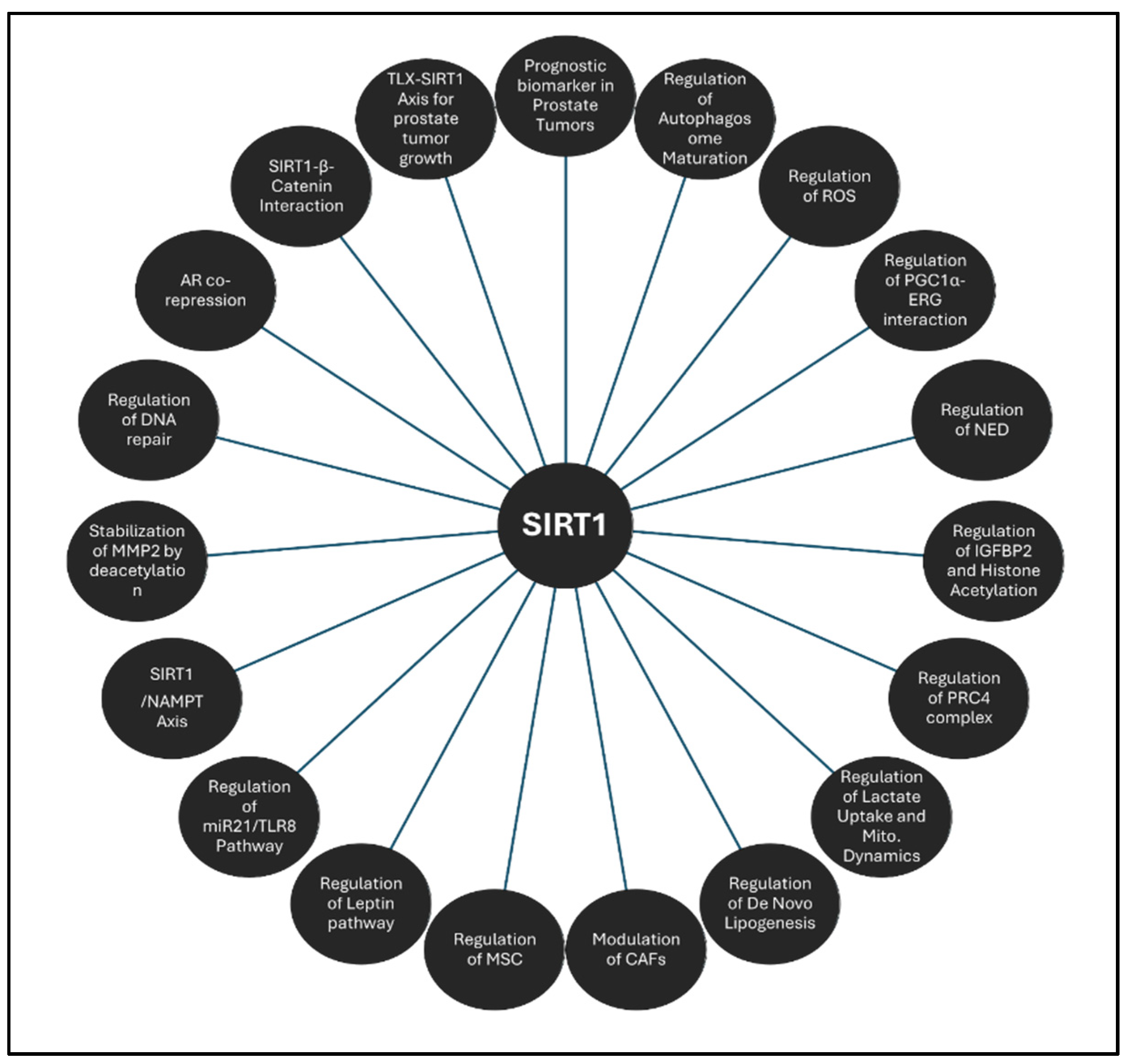

3.1.1. SIRT1

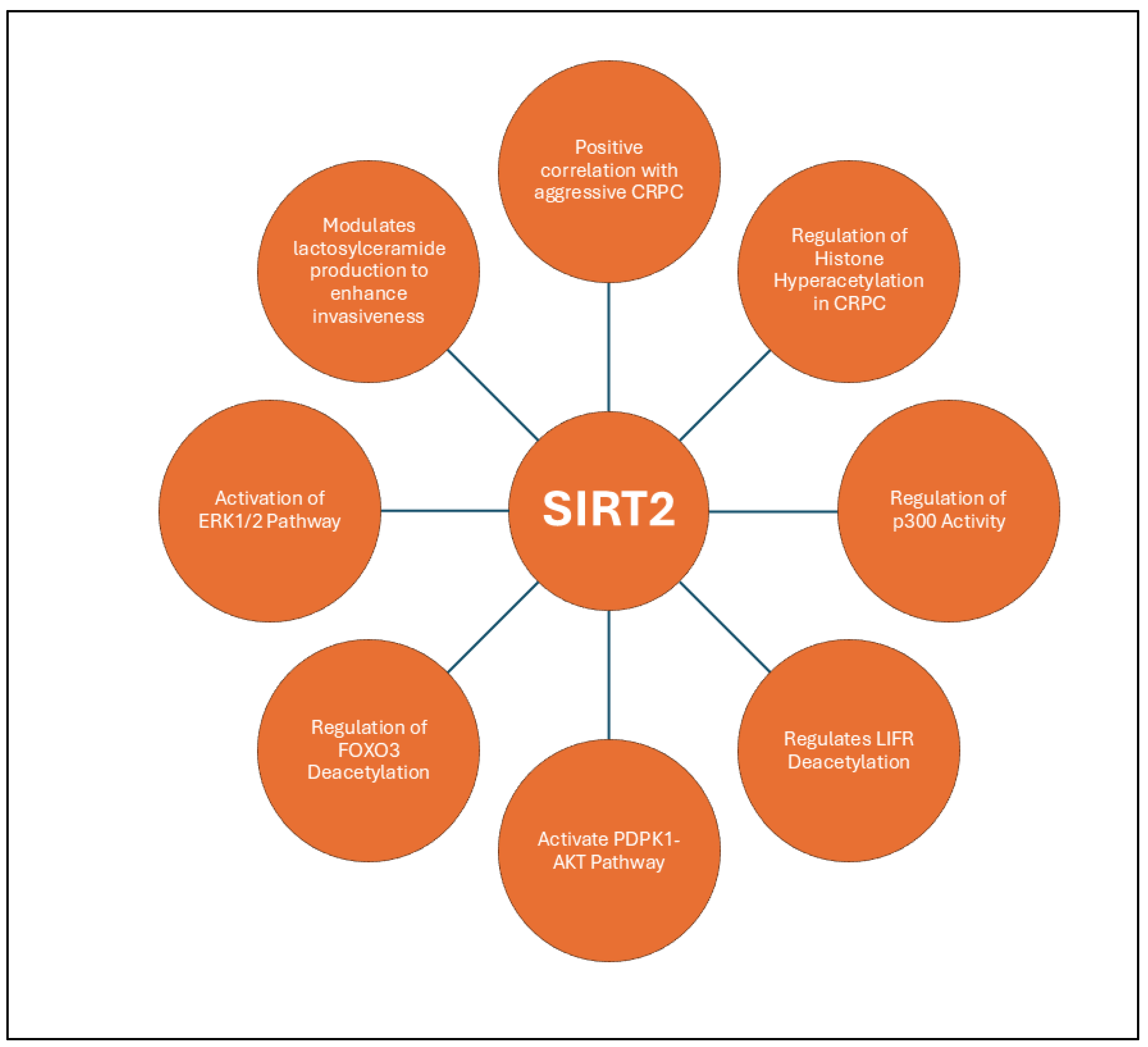

3.1.2. SIRT2

3.1.3. SIRT6

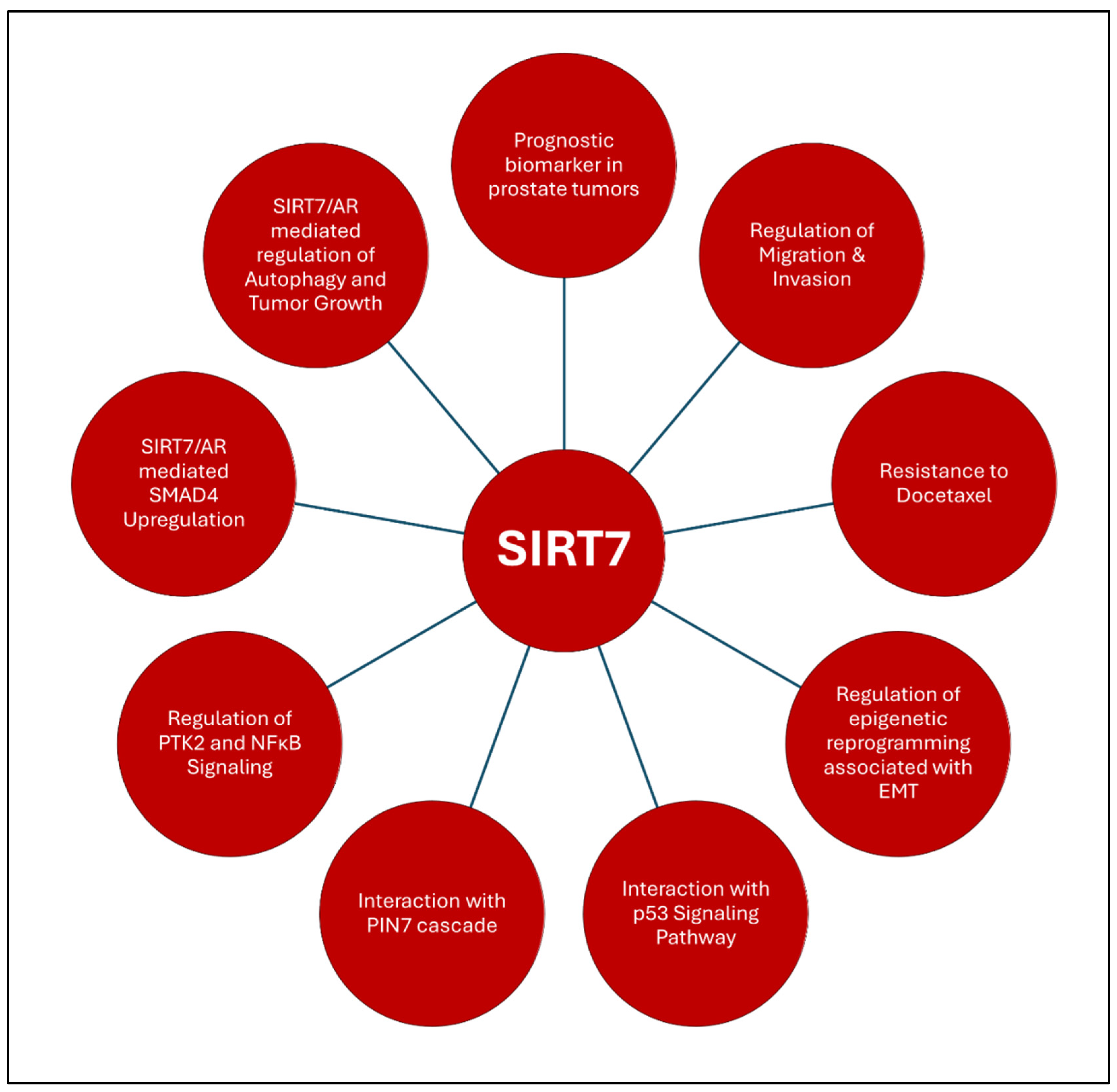

3.1.4. SIRT7

3.2. Tumor Suppressor Sirtuins

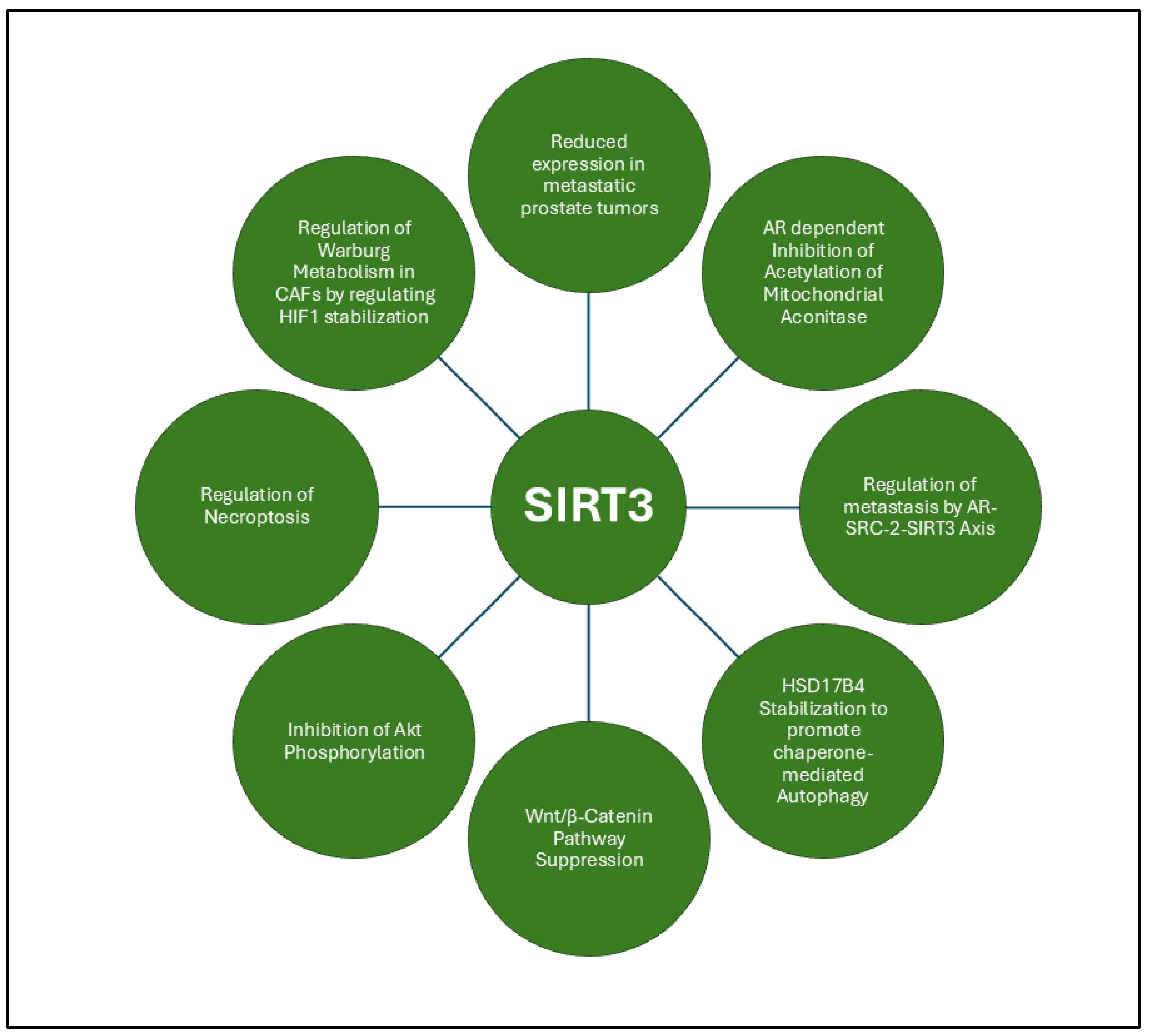

3.2.1. SIRT3

3.2.2. SIRT4

3.3. Janus-Faced/Dual Acting Sirtuin

3.3.1. SIRT5

4. Sirtuin-Based Interventions in Prostate Cancer Management

5. Conclusion and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rawla, P., Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol 2019, 10, (2), 63-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A., Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, (3), 229-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, P. A., Histopathology of Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7, (10).

- Pascale, M.; Azinwi, C. N.; Marongiu, B.; Pesce, G.; Stoffel, F.; Roggero, E., The outcome of prostate cancer patients treated with curative intent strongly depends on survival after metastatic progression. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, (1), 651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, S.; Sridaran, D.; Weimholt, C.; Luo, J.; Li, T.; Hodgson, M. C.; Santos, L. N.; Le Sommer, S.; Fang, B.; Koomen, J. M.; Seeliger, M.; Qu, C. K.; Yart, A.; Kontaridis, M. I.; Mahajan, K.; Mahajan, N. P., SHP2 as a primordial epigenetic enzyme expunges histone H3 pTyr-54 to amend androgen receptor homeostasis. Nat Commun 2024, 15, (1), 5629. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Sawant, M.; Weimholt, C.; Luo, J.; Sprung, R. W.; Terrado, M.; Mueller, D. M.; Earp, H. S.; Mahajan, N. P., TNK2/ACK1-mediated phosphorylation of ATP5F1A (ATP synthase F1 subunit alpha) selectively augments survival of prostate cancer while engendering mitochondrial vulnerability. Autophagy 2023, 19, (3), 1000-1025. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Sridaran, D.; Chouhan, S.; Weimholt, C.; Wilson, A.; Luo, J.; Li, T.; Koomen, J.; Fang, B.; Putluri, N.; Sreekumar, A.; Feng, F. Y.; Mahajan, K.; Mahajan, N. P., Histone H2A Lys130 acetylation epigenetically regulates androgen production in prostate cancer. Nat Commun 2023, 14, (1), 3357. [CrossRef]

- Sridaran, D.; Chouhan, S.; Mahajan, K.; Renganathan, A.; Weimholt, C.; Bhagwat, S.; Reimers, M.; Kim, E. H.; Thakur, M. K.; Saeed, M. A.; Pachynski, R. K.; Seeliger, M. A.; Miller, W. T.; Feng, F. Y.; Mahajan, N. P., Inhibiting ACK1-mediated phosphorylation of C-terminal Src kinase counteracts prostate cancer immune checkpoint blockade resistance. Nat Commun 2022, 13, (1), 6929. [CrossRef]

- Armenia, J.; Wankowicz, S. A. M.; Liu, D.; Gao, J.; Kundra, R.; Reznik, E.; Chatila, W. K.; Chakravarty, D.; Han, G. C.; Coleman, I.; Montgomery, B.; Pritchard, C.; Morrissey, C.; Barbieri, C. E.; Beltran, H.; Sboner, A.; Zafeiriou, Z.; Miranda, S.; Bielski, C. M.; Penson, A. V.; Tolonen, C.; Huang, F. W.; Robinson, D.; Wu, Y. M.; Lonigro, R.; Garraway, L. A.; Demichelis, F.; Kantoff, P. W.; Taplin, M. E.; Abida, W.; Taylor, B. S.; Scher, H. I.; Nelson, P. S.; de Bono, J. S.; Rubin, M. A.; Sawyers, C. L.; Chinnaiyan, A. M.; Team, P. S. C. I. P. C. D.; Schultz, N.; Van Allen, E. M., The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet 2018, 50, (5), 645-651. [CrossRef]

- Athavale, D.; Chouhan, S.; Pandey, V.; Mayengbam, S. S.; Singh, S.; Bhat, M. K., Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated hypercholesterolemia: involvement of proprotein-convertase-subtilisin-kexin type-9 (PCSK9). Cancer Metab 2018, 6, 16. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D., Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, (1), 31-46. [CrossRef]

- Rasool, R. U.; Natesan, R.; Asangani, I. A., Toppling the HAT to Treat Lethal Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, (5), 1011-1013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Gupta, S., The role of histone deacetylases in prostate cancer. Epigenetics 2008, 3, (6), 300-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyiba, C. I.; Scarlett, C. J.; Weidenhofer, J., The Mechanistic Roles of Sirtuins in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, (20).

- Herskovits, A. Z.; Guarente, L., Sirtuin deacetylases in neurodegenerative diseases of aging. Cell Res 2013, 23, (6), 746-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaidi, I.; Kim, S., Sirtuins are crucial regulators of T cell metabolism and functions. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54, (3), 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Carafa, V.; Altucci, L.; Nebbioso, A., Dual Tumor Suppressor and Tumor Promoter Action of Sirtuins in Determining Malignant Phenotype. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 38. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. H.; Sengupta, K.; Li, C.; Kim, H. S.; Cao, L.; Xiao, C.; Kim, S.; Xu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chilton, B.; Jia, R.; Zheng, Z. M.; Appella, E.; Wang, X. W.; Ried, T.; Deng, C. X., Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, (4), 312-23. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Fernandes, D. K.; Jasiulionis, M. G., The Role of SIRT1 on DNA Damage Response and Epigenetic Alterations in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, (13).

- Meng, F.; Qian, M.; Peng, B.; Peng, L.; Wang, X.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S.; Cao, X.; Pang, Q.; Zhao, B.; Ma, W.; Songyang, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhu, W. G.; Xu, X.; Liu, B., Synergy between SIRT1 and SIRT6 helps recognize DNA breaks and potentiates the DNA damage response and repair in humans and mice. Elife 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, D.; Eremenko, E.; Stein, D.; Kaluski, S.; Jasinska, W.; Cosentino, C.; Martinez-Pastor, B.; Brotman, Y.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Khrameeva, E.; Toiber, D., SIRT6 is a key regulator of mitochondrial function in the brain. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, (1), 35. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, D. B.; Schwer, B.; Alt, F. W.; Mostoslavsky, R., SIRT6 in DNA repair, metabolism and ageing. J Intern Med 2008, 263, (2), 128-41. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Chen, L.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; He, J., The Role of Sirt6 in Obesity and Diabetes. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 135. [CrossRef]

- Roichman, A.; Elhanati, S.; Aon, M. A.; Abramovich, I.; Di Francesco, A.; Shahar, Y.; Avivi, M. Y.; Shurgi, M.; Rubinstein, A.; Wiesner, Y.; Shuchami, A.; Petrover, Z.; Lebenthal-Loinger, I.; Yaron, O.; Lyashkov, A.; Ubaida-Mohien, C.; Kanfi, Y.; Lerrer, B.; Fernandez-Marcos, P. J.; Serrano, M.; Gottlieb, E.; de Cabo, R.; Cohen, H. Y., Restoration of energy homeostasis by SIRT6 extends healthy lifespan. Nat Commun 2021, 12, (1), 3208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden, S. C.; Nahhas, F. A.; Nowak, J. E.; Goustin, A. S.; Tainsky, M. A., Role for human SIRT2 NAD-dependent deacetylase activity in control of mitotic exit in the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, (9), 3173-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, L.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Marazuela-Duque, A.; Vazquez, B. N.; Dooley, S. J.; Voigt, P.; Beck, D. B.; Kane-Goldsmith, N.; Tong, Q.; Rabanal, R. M.; Fondevila, D.; Munoz, P.; Kruger, M.; Tischfield, J. A.; Vaquero, A., The tumor suppressor SirT2 regulates cell cycle progression and genome stability by modulating the mitotic deposition of H4K20 methylation. Genes Dev 2013, 27, (6), 639-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. H.; Zhu, Y.; Ozden, O.; Kim, H. S.; Jiang, H.; Deng, C. X.; Gius, D.; Vassilopoulos, A., SIRT2 is a tumor suppressor that connects aging, acetylome, cell cycle signaling, and carcinogenesis. Transl Cancer Res 2012, 1, (1), 15-21. [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Hong, T.; Chen, X.; Cui, L., SIRT2: Controversy and multiple roles in disease and physiology. Ageing Res Rev 2019, 55, 100961. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Qiu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, J.; Chai, Z.; Liu, C., Multiple Roles of SIRT2 in Regulating Physiological and Pathological Signal Transduction. Genet Res (Camb) 2022, 2022, 9282484. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kim, S.; Ren, X., The Clinical Significance of SIRT2 in Malignancies: A Tumor Suppressor or an Oncogene? Front Oncol 2020, 10, 1721. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, H., Mitochondrial sirtuins: Energy dynamics and cancer metabolism. Mol Cells 2024, 47, (2), 100029. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ma, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Fu, L.; Qin, Z., Mitochondrial Sirtuins in Cancer: A Revisited Review from Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Theranostics 2024, 14, (7), 2993-3013. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lombard, D. B., Mitochondrial sirtuins and their relationships with metabolic disease and cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015, 22, (12), 1060-77. [CrossRef]

- Haigis, M. C.; Deng, C. X.; Finley, L. W.; Kim, H. S.; Gius, D., SIRT3 is a mitochondrial tumor suppressor: a scientific tale that connects aberrant cellular ROS, the Warburg effect, and carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2012, 72, (10), 2468-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H. S.; Patel, K.; Muldoon-Jacobs, K.; Bisht, K. S.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Pennington, J. D.; van der Meer, R.; Nguyen, P.; Savage, J.; Owens, K. M.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Ozden, O.; Park, S. H.; Singh, K. K.; Abdulkadir, S. A.; Spitz, D. R.; Deng, C. X.; Gius, D., SIRT3 is a mitochondria-localized tumor suppressor required for maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and metabolism during stress. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, (1), 41-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, L. L.; Wen, X.; Wang, X. Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, J., Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3), a therapeutic target with oncogenic and tumor-suppressive function in cancer. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, (2), e1047. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Huang, D.; Liu, G.; Jian, F.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L., SIRT4 acts as a tumor suppressor in gastric cancer by inhibiting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 3959-3968. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaselli, D.; Steegborn, C.; Mai, A.; Rotili, D., Sirt4: A Multifaceted Enzyme at the Crossroads of Mitochondrial Metabolism and Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 474. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. M.; Xiao, C.; Finley, L. W.; Lahusen, T.; Souza, A. L.; Pierce, K.; Li, Y. H.; Wang, X.; Laurent, G.; German, N. J.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Wang, R. H.; Lee, J.; Csibi, A.; Cerione, R.; Blenis, J.; Clish, C. B.; Kimmelman, A.; Deng, C. X.; Haigis, M. C., SIRT4 has tumor-suppressive activity and regulates the cellular metabolic response to DNA damage by inhibiting mitochondrial glutamine metabolism. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, (4), 450-63. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Ge, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cai, L.; Sun, P.; Huang, G., SIRT4 functions as a tumor suppressor during prostate cancer by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting glutamine metabolism. Sci Rep 2022, 12, (1), 12208. [CrossRef]

- Blank, M. F.; Chen, S.; Poetz, F.; Schnolzer, M.; Voit, R.; Grummt, I., SIRT7-dependent deacetylation of CDK9 activates RNA polymerase II transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, (5), 2675-2686. [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Villanova, L.; Tanaka, S.; Aonuma, M.; Roy, N.; Berber, E.; Pollack, J. R.; Michishita-Kioi, E.; Chua, K. F., SIRT7 inactivation reverses metastatic phenotypes in epithelial and mesenchymal tumors. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 9841. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. J.; Zhang, T. N.; Chen, H. H.; Yu, X. F.; Lv, J. L.; Liu, Y. Y.; Liu, Y. S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J. Q.; Wei, Y. F.; Guo, J. Y.; Liu, F. H.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y. X.; Liu, C. G.; Zhao, Y. H., The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, (1), 402.

- Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, F.; Ye, J., The role of sirtuins in the regulatin of oxidative stress during the progress and therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Life Sci 2023, 333, 122187. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merksamer, P. I.; Liu, Y.; He, W.; Hirschey, M. D.; Chen, D.; Verdin, E., The sirtuins, oxidative stress and aging: an emerging link. Aging (Albany NY) 2013, 5, (3), 144-50.

- Fortuny, L.; Sebastian, C., Sirtuins as Metabolic Regulators of Immune Cells Phenotype and Function. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, (11).

- Tao, Z.; Jin, Z.; Wu, J.; Cai, G.; Yu, X., Sirtuin family in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1186231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C. Q.; Li, J.; Liang, Z. Q.; Zhong, Y. L.; Zhang, Z. H.; Hu, X. Q.; Cao, Y. B.; Chen, J., Sirtuins in macrophage immune metabolism: A novel target for cardiovascular disorders. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 256, (Pt 1), 128270. [CrossRef]

- Vachharajani, V. T.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Hoth, J. J.; Yoza, B. K.; McCall, C. E., Sirtuins Link Inflammation and Metabolism. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 8167273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, K. L.; Lelis, D. F.; Santos, S. H. S., Nuclear sirtuins and inflammatory signaling pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2017, 38, 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Landry, J.; Sternglanz, R.; Xu, R. M., Crystal structure of a SIR2 homolog-NAD complex. Cell 2001, 105, (2), 269-79. [CrossRef]

- Finnin, M. S.; Donigian, J. R.; Pavletich, N. P., Structure of the histone deacetylase SIRT2. Nat Struct Biol 2001, 8, (7), 621-5. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. H.; Kim, H. C.; Hwang, K. Y.; Lee, J. W.; Jackson, S. P.; Bell, S. D.; Cho, Y., Structural basis for the NAD-dependent deacetylase mechanism of Sir2. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, (37), 34489-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Chai, X.; Marmorstein, R., Structure of the yeast Hst2 protein deacetylase in ternary complex with 2'-O-acetyl ADP ribose and histone peptide. Structure 2003, 11, (11), 1403-11. [CrossRef]

- Klein, M. A.; Denu, J. M., Biological and catalytic functions of sirtuin 6 as targets for small-molecule modulators. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, (32), 11021-11041. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B. D.; Jackson, B.; Marmorstein, R., Structural basis for sirtuin function: what we know and what we don't. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1804, (8), 1604-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalos, J. L.; Boeke, J. D.; Wolberger, C., Structural basis for the mechanism and regulation of Sir2 enzymes. Mol Cell 2004, 13, (5), 639-48. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Yuan, H.; Brent, M.; Ding, E. C.; Marmorstein, R., SIRT1 contains N- and C-terminal regions that potentiate deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, (4), 2468-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Wang, M.; Qiu, X.; Liu, D.; Jiang, H.; Yang, N.; Xu, R. M., Structural basis for allosteric, substrate-dependent stimulation of SIRT1 activity by resveratrol. Genes Dev 2015, 29, (12), 1316-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carafa, V.; Rotili, D.; Forgione, M.; Cuomo, F.; Serretiello, E.; Hailu, G. S.; Jarho, E.; Lahtela-Kakkonen, M.; Mai, A.; Altucci, L., Sirtuin functions and modulation: from chemistry to the clinic. Clin Epigenetics 2016, 8, 61. [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, M. J. G.; Pereira, J. M.; Impens, F.; Hamon, M. A., Active nuclear import of the deacetylase Sirtuin-2 is controlled by its C-terminus and importins. Sci Rep 2020, 10, (1), 2034. [CrossRef]

- Abeywardana, M. Y.; Whedon, S. D.; Lee, K.; Nam, E.; Dovarganes, R.; DuBois-Coyne, S.; Haque, I. A.; Wang, Z. A.; Cole, P. A., Multifaceted regulation of sirtuin 2 (Sirt2) deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem 2024, 300, (9), 107722. [CrossRef]

- Zietara, P.; Dziewiecka, M.; Augustyniak, M., Why Is Longevity Still a Scientific Mystery? Sirtuins-Past, Present and Future. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24, (1).

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; He, R. R.; Liu, B., Mitochondrial Sirtuin 3: New emerging biological function and therapeutic target. Theranostics 2020, 10, (18), 8315-8342. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Y.; Hirschey, M. D.; Shimazu, T.; Ho, L.; Verdin, E., Mitochondrial sirtuins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1804, (8), 1645-51. [CrossRef]

- Sack, M. N.; Finkel, T., Mitochondrial metabolism, sirtuins, and aging. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, (12).

- Greiss, S.; Gartner, A., Sirtuin/Sir2 phylogeny, evolutionary considerations and structural conservation. Mol Cells 2009, 28, (5), 407-15. [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, A.; Fritz, K. S.; Petersen, D. R.; Gius, D., The human sirtuin family: evolutionary divergences and functions. Hum Genomics 2011, 5, (5), 485-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, S.; Sharma, A.; Raucci, R.; Costantini, M.; Autiero, I.; Colonna, G., Genealogy of an ancient protein family: the Sirtuins, a family of disordered members. BMC Evol Biol 2013, 13, 60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, S.; Cai, K.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Tan, W.; Lin, W.; Zhao, G. P.; Zhao, W., Zymograph profiling reveals a divergent evolution of sirtuin that may originate from class III enzymes. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, (11), 105339. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Redondo, P.; Vaquero, A., The diversity of histone versus nonhistone sirtuin substrates. Genes Cancer 2013, 4, (3-4), 148-63.

- Majeed, Y.; Halabi, N.; Madani, A. Y.; Engelke, R.; Bhagwat, A. M.; Abdesselem, H.; Agha, M. V.; Vakayil, M.; Courjaret, R.; Goswami, N.; Hamidane, H. B.; Elrayess, M. A.; Rafii, A.; Graumann, J.; Schmidt, F.; Mazloum, N. A., SIRT1 promotes lipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipocytes and coordinates adipogenesis by targeting key enzymatic pathways. Sci Rep 2021, 11, (1), 8177. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ameer, F. S.; Azhar, G.; Wei, J. Y., Alternative Splicing Increases Sirtuin Gene Family Diversity and Modulates Their Subcellular Localization and Function. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (2).

- Bai, W.; Zhang, X., Nucleus or cytoplasm? The mysterious case of SIRT1's subcellular localization. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, (24), 3337-3338. [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; Sakamoto, J.; Miura, T.; Shimamoto, K.; Horio, Y., Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, (9), 6823-32. [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, P. M.; Liang, F., Sub-cellular localization, expression and functions of Sirt6 during the cell cycle in HeLa cells. Nucleus 2012, 3, (5), 442-51. [CrossRef]

- Di Emidio, G.; Falone, S.; Artini, P. G.; Amicarelli, F.; D'Alessandro, A. M.; Tatone, C., Mitochondrial Sirtuins in Reproduction. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, (7).

- Ramadani-Muja, J.; Gottschalk, B.; Pfeil, K.; Burgstaller, S.; Rauter, T.; Bischof, H.; Waldeck-Weiermair, M.; Bugger, H.; Graier, W. F.; Malli, R., Visualization of Sirtuin 4 Distribution between Mitochondria and the Nucleus, Based on Bimolecular Fluorescence Self-Complementation. Cells 2019, 8, (12).

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, P.; Luo, J.; Ding, H.; Cao, H.; He, W.; Zen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, L., Sirtuin 3 regulates mitochondrial protein acetylation and metabolism in tubular epithelial cells during renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, (9), 847. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C. S. S.; Cerqueira, N.; Gomes, P.; Sousa, S. F., A Molecular Perspective on Sirtuin Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (22).

- Moniot, S.; Weyand, M.; Steegborn, C., Structures, substrates, and regulators of Mammalian sirtuins - opportunities and challenges for drug development. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 16. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. C.; Hallows, W. C.; Denu, J. M., Mechanisms and molecular probes of sirtuins. Chem Biol 2008, 15, (10), 1002-13. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A. M.; Huber, F. M.; Hoelz, A., Structural and functional analysis of human SIRT1. J Mol Biol 2014, 426, (3), 526-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P. W.; Feldman, J. L.; Devries, M. K.; Dong, A.; Edwards, A. M.; Denu, J. M., Structure and biochemical functions of SIRT6. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, (16), 14575-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carafa, V.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L., Sirtuins and disease: the road ahead. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, J.; Hu, K.; He, X.; Yun, D.; Tong, T.; Han, L., Sirtuins and their Biological Relevance in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Aging Dis 2020, 11, (4), 927-945. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, W.; Sikora, E.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A., Sirtuins, a promising target in slowing down the ageing process. Biogerontology 2017, 18, (4), 447-476. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, A.; Imai, S. I.; Guarente, L., The brain, sirtuins, and ageing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, (6), 362-374. [CrossRef]

- Fajardo-Orduna, G. R.; Ledesma-Martinez, E.; Aguiniga-Sanchez, I.; Weiss-Steider, B.; Santiago-Osorio, E., Role of SIRT1 in Chemoresistant Leukemia. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (19).

- Hain, B. A.; Kimball, S. R.; Waning, D. L., Preventing loss of sirt1 lowers mitochondrial oxidative stress and preserves C2C12 myotube diameter in an in vitro model of cancer cachexia. Physiol Rep 2024, 12, (13), e16103. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Yang, Y.; Wu, E.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q., SIRT2 promotes cell proliferation and migration through mediating ERK1/2 activation and lactosylceramide accumulation in prostate cancer. Prostate 2023, 83, (1), 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Damaschke, N.; Gawdzik, J.; Yang, B.; Shi, C.; Allen, G. O.; Huang, W.; Denu, J.; Jarrard, D., Dysregulation of Sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) and histone H3K18 acetylation pathways associates with adverse prostate cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, (1), 874. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Quan, Y.; Xia, W., SIRT3 inhibits prostate cancer metastasis through regulation of FOXO3A by suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Exp Cell Res 2018, 364, (2), 143-151. [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Wang, N.; Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Cheng, W.; Di, M.; Xia, W.; Gao, W. Q., SIRT3 inhibits prostate cancer by destabilizing oncoprotein c-MYC through regulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncotarget 2015, 6, (28), 26494-507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O. K.; Bang, I. H.; Choi, S. Y.; Jeon, J. M.; Na, A. Y.; Gao, Y.; Cho, S. S.; Ki, S. H.; Choe, Y.; Lee, J. N.; Ha, Y. S.; Bae, E. J.; Kwon, T. G.; Park, B. H.; Lee, S., LDHA Desuccinylase Sirtuin 5 as A Novel Cancer Metastatic Stimulator in Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2023, 21, (1), 177-189. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Jiang, X.; Gai, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, M.; Du, T.; Fu, L.; Li, Q., Sirtuin 5 regulates the proliferation, invasion and migration of prostate cancer cells through acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, (23), 14039-14049. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S. Y.; Jeon, J. M.; Na, A. Y.; Kwon, O. K.; Bang, I. H.; Ha, Y. S.; Bae, E. J.; Park, B. H.; Lee, E. H.; Kwon, T. G.; Lee, J. N.; Lee, S., SIRT5 Directly Inhibits the PI3K/AKT Pathway in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2022, 19, (1), 50-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, R.; Song, L. D.; Zhu, L. F.; Zhan, J. F., SIRT6 Promotes the Progression of Prostate Cancer via Regulating the Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. J Oncol 2022, 2022, 2174758.

- Haider, R.; Massa, F.; Kaminski, L.; Clavel, S.; Djabari, Z.; Robert, G.; Laurent, K.; Michiels, J. F.; Durand, M.; Ricci, J. E.; Tanti, J. F.; Bost, F.; Ambrosetti, D., Sirtuin 7: a new marker of aggressiveness in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, (44), 77309-77316. [CrossRef]

- Huffman, D. M.; Grizzle, W. E.; Bamman, M. M.; Kim, J. S.; Eltoum, I. A.; Elgavish, A.; Nagy, T. R., SIRT1 is significantly elevated in mouse and human prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2007, 67, (14), 6612-8. [CrossRef]

- Powell, M. J.; Casimiro, M. C.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; He, X.; Yeow, W. S.; Wang, C.; McCue, P. A.; McBurney, M. W.; Pestell, R. G., Disruption of a Sirt1-dependent autophagy checkpoint in the prostate results in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesion formation. Cancer Res 2011, 71, (3), 964-75. [CrossRef]

- Di Sante, G.; Pestell, T. G.; Casimiro, M. C.; Bisetto, S.; Powell, M. J.; Lisanti, M. P.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Castillo-Martin, M.; Bonal, D. M.; Debattisti, V.; Chen, K.; Wang, L.; He, X.; McBurney, M. W.; Pestell, R. G., Loss of Sirt1 promotes prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, reduces mitophagy, and delays PARK2 translocation to mitochondria. Am J Pathol 2015, 185, (1), 266-79. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Ohhashi, R.; Fujita, Y.; Hamada, N.; Akao, Y.; Nozawa, Y.; Deguchi, T.; Ito, M., A role for SIRT1 in cell growth and chemoresistance in prostate cancer PC3 and DU145 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 373, (3), 423-8. [CrossRef]

- Dhara, A.; Aier, I.; Paladhi, A.; Varadwaj, P. K.; Hira, S. K.; Sen, N., PGC1 alpha coactivates ERG fusion to drive antioxidant target genes under metabolic stress. Commun Biol 2022, 5, (1), 416. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; He, M.; Yao, X., SIRT1 contributes to neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, (2), 2002-2016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.; Xu, J.; Osunkoya, A. O.; Sannigrahi, S.; Johnson, B. A.; Zhou, W.; Gillespie, T.; Park, J. Y.; Nam, R. K.; Sugar, L.; Stanimirovic, A.; Seth, A. K.; Petros, J. A.; Moreno, C. S., Global transcriptome analysis of formalin-fixed prostate cancer specimens identifies biomarkers of disease recurrence. Cancer Res 2014, 74, (12), 3228-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawryka, J.; Barg, E., [Impact of SIRT1 gene expression on the development and treatment of the metabolic syndrome in oncological patients]. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2016, 22, (2), 60-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernacka, K. M.; Uzoh, C. C.; Zeng, L.; Persad, R. A.; Bahl, A.; Gillatt, D.; Perks, C. M.; Holly, J. M., Hyperglycaemia-induced chemoresistance of prostate cancer cells due to IGFBP2. Endocr Relat Cancer 2013, 20, (5), 741-51. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mayengbam, S. S.; Chouhan, S.; Deshmukh, B.; Ramteke, P.; Athavale, D.; Bhat, M. K., Role of TNFalpha and leptin signaling in colon cancer incidence and tumor growth under obese phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, (5), 165660.

- Malvi, P.; Chaube, B.; Singh, S. V.; Mohammad, N.; Vijayakumar, M. V.; Singh, S.; Chouhan, S.; Bhat, M. K., Elevated circulatory levels of leptin and resistin impair therapeutic efficacy of dacarbazine in melanoma under obese state. Cancer Metab 2018, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. C.; Hsiao, M., Leptin and Cancer: Updated Functional Roles in Carcinogenesis, Therapeutic Niches, and Developments. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (6).

- Singh, S.; Chouhan, S.; Mohammad, N.; Bhat, M. K., Resistin causes G1 arrest in colon cancer cells through upregulation of SOCS3. FEBS Lett 2017, 591, (10), 1371-1382. [CrossRef]

- Calgani, A.; Delle Monache, S.; Cesare, P.; Vicentini, C.; Bologna, M.; Angelucci, A., Leptin contributes to long-term stabilization of HIF-1alpha in cancer cells subjected to oxygen limiting conditions. Cancer Lett 2016, 376, (1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, L.; Morandi, A.; Taddei, M. L.; Parri, M.; Comito, G.; Iscaro, A.; Raspollini, M. R.; Magherini, F.; Rapizzi, E.; Masquelier, J.; Muccioli, G. G.; Sonveaux, P.; Chiarugi, P.; Giannoni, E., Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote prostate cancer malignancy via metabolic rewiring and mitochondrial transfer. Oncogene 2019, 38, (27), 5339-5355. [CrossRef]

- Natani, S.; Dhople, V. M.; Parveen, A.; Sruthi, K. K.; Khilar, P.; Bhukya, S.; Ummanni, R., AMPK/SIRT1 signaling through p38MAPK mediates Interleukin-6 induced neuroendocrine differentiation of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868, (10), 119085. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comito, G.; Iscaro, A.; Bacci, M.; Morandi, A.; Ippolito, L.; Parri, M.; Montagnani, I.; Raspollini, M. R.; Serni, S.; Simeoni, L.; Giannoni, E.; Chiarugi, P., Lactate modulates CD4(+) T-cell polarization and induces an immunosuppressive environment, which sustains prostate carcinoma progression via TLR8/miR21 axis. Oncogene 2019, 38, (19), 3681-3695. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debelec-Butuner, B.; Ertunc, N.; Korkmaz, K. S., Inflammation contributes to NKX3.1 loss and augments DNA damage but does not alter the DNA damage response via increased SIRT1 expression. J Inflamm (Lond) 2015, 12, 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmichev, A.; Margueron, R.; Vaquero, A.; Preissner, T. S.; Scher, M.; Kirmizis, A.; Ouyang, X.; Brockdorff, N.; Abate-Shen, C.; Farnham, P.; Reinberg, D., Composition and histone substrates of polycomb repressive group complexes change during cellular differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, (6), 1859-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, T.; Graca, I.; Sousa, E. J.; Oliveira, A. I.; Costa, N. R.; Costa-Pinheiro, P.; Amado, F.; Henrique, R.; Jeronimo, C., Regulation of histone H2A.Z expression is mediated by sirtuin 1 in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2013, 4, (10), 1673-85. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, H. J.; Sim, D. Y.; Park, J. E.; Ahn, C. H.; Park, S. Y.; Lee, Y. C.; Shim, B. S.; Kim, B.; Kim, S. H., Inhibition of glycolysis and SIRT1/GLUT1 signaling ameliorates the apoptotic effect of Leptosidin in prostate cancer cells. Phytother Res 2024, 38, (3), 1235-1244. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chan, C. H.; Chen, K.; Guan, X.; Lin, H. K.; Tong, Q., Deacetylation of FOXO3 by SIRT1 or SIRT2 leads to Skp2-mediated FOXO3 ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene 2012, 31, (12), 1546-57. [CrossRef]

- Jung-Hynes, B.; Nihal, M.; Zhong, W.; Ahmad, N., Role of sirtuin histone deacetylase SIRT1 in prostate cancer. A target for prostate cancer management via its inhibition? J Biol Chem 2009, 284, (6), 3823-32. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, H.; Haller, E. M.; Nicosia, S. V.; Bai, W., Suppression of FOXO1 activity by FHL2 through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation. EMBO J 2005, 24, (5), 1021-32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hasan, M. K.; Alvarado, E.; Yuan, H.; Wu, H.; Chen, W. Y., NAMPT overexpression in prostate cancer and its contribution to tumor cell survival and stress response. Oncogene 2011, 30, (8), 907-21. [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X., Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase enhances the progression of prostate cancer by stabilizing sirtuin 1. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, (6), 9195-9201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, S. C.; Thomas, M. J.; D'Agostino, R. B., Jr.; Kridel, S. J., Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (Nampt) is required for de novo lipogenesis in tumor cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, (6), e40195. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P. K.; Patra, S.; Naik, P. P.; Praharaj, P. P.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Meher, B. R.; Gupta, P. K.; Verma, R. S.; Maiti, T. K.; Bhutia, S. K., Deacetylation of LAMP1 drives lipophagy-dependent generation of free fatty acids by Abrus agglutinin to promote senescence in prostate cancer. J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, (3), 2776-2791. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Nonomura, N., Role of Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer: A Review. World J Mens Health 2019, 37, (3), 288-295. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Ngo, D.; Forman, L. W.; Qin, D. C.; Jacob, J.; Faller, D. V., Sirtuin 1 is required for antagonist-induced transcriptional repression of androgen-responsive genes by the androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol 2007, 21, (8), 1807-21. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, E.; Rinaldo, F.; Datta, K., Upregulation of VEGF-C by androgen depletion: the involvement of IGF-IR-FOXO pathway. Oncogene 2005, 24, (35), 5510-20. [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, A.; Chaurasia, P.; Xiao, G. Q.; Philizaire, M.; Lv, X.; Yao, S.; Burnstein, K. L.; Liu, D. P.; Levine, A. C.; Mujtaba, S., Coactivator MYST1 regulates nuclear factor-kappaB and androgen receptor functions during proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 2014, 28, (6), 872-85. [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Liu, M.; Sauve, A. A.; Jiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Powell, M. J.; Yang, T.; Gu, W.; Avantaggiati, M. L.; Pattabiraman, N.; Pestell, T. G.; Wang, F.; Quong, A. A.; Wang, C.; Pestell, R. G., Hormonal control of androgen receptor function through SIRT1. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, (21), 8122-35. [CrossRef]

- Jung-Hynes, B.; Ahmad, N., Role of p53 in the anti-proliferative effects of Sirt1 inhibition in prostate cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, (10), 1478-83. [CrossRef]

- Van Rechem, C.; Rood, B. R.; Touka, M.; Pinte, S.; Jenal, M.; Guerardel, C.; Ramsey, K.; Monte, D.; Begue, A.; Tschan, M. P.; Stephan, D. A.; Leprince, D., Scavenger chemokine (CXC motif) receptor 7 (CXCR7) is a direct target gene of HIC1 (hypermethylated in cancer 1). J Biol Chem 2009, 284, (31), 20927-35. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. B.; Thapa, D.; Munoz, A. R.; Hussain, S. S.; Yang, X.; Bedolla, R. G.; Osmulski, P.; Gaczynska, M. E.; Lai, Z.; Chiu, Y. C.; Wang, L. J.; Chen, Y.; Rivas, P.; Shudde, C.; Reddick, R. L.; Miyamoto, H.; Ghosh, R.; Kumar, A. P., Androgen deprivation-induced elevated nuclear SIRT1 promotes prostate tumor cell survival by reactivation of AR signaling. Cancer Lett 2021, 505, 24-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Q.; Zong, C.; Liang, L.; Yang, X.; Lin, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hou, X.; Han, Z.; Cheng, J., Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Sirt1 inhibit prostate cancer growth by recruiting natural killer cells and macrophages. Oncotarget 2016, 7, (44), 71112-71122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Ruan, J.; Mi, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Ding, Q., Knockdown of TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) modulates in vitro growth of TRAIL-treated prostate cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 93, 462-469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. Y., SIRT1 and LSD1 competitively regulate KU70 functions in DNA repair and mutation acquisition in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, (31), 50195-50214. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, F.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Mu, S.; Zhang, H., Effect of SIRT1 Gene on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Human Prostate Cancer PC-3 Cells. Med Sci Monit 2016, 22, 380-6. [CrossRef]

- Lovaas, J. D.; Zhu, L.; Chiao, C. Y.; Byles, V.; Faller, D. V.; Dai, Y., SIRT1 enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression and tumor cell invasion in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2013, 73, (5), 522-30. [CrossRef]

- Byles, V.; Zhu, L.; Lovaas, J. D.; Chmilewski, L. K.; Wang, J.; Faller, D. V.; Dai, Y., SIRT1 induces EMT by cooperating with EMT transcription factors and enhances prostate cancer cell migration and metastasis. Oncogene 2012, 31, (43), 4619-29. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Kokura, K.; Izumi, V.; Koomen, J. M.; Seto, E.; Chen, J.; Fang, J., MPP8 and SIRT1 crosstalk in E-cadherin gene silencing and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. EMBO Rep 2015, 16, (6), 689-99. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Ramalinga, M.; Kim, O. J.; Chijioke, J.; Lynch, S.; Byers, S.; Kumar, D., Multiple roles of RARRES1 in prostate cancer: Autophagy induction and angiogenesis inhibition. PLoS One 2017, 12, (7), e0180344. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Kumar, A.; Piprode, V.; Dasgupta, A.; Singh, S.; Khalique, A., Regulatory-Associated Protein of mTOR-Mediated Signaling: A Nexus Between Tumorigenesis and Disease. Targets 2024, 2, (4), 341-371. [CrossRef]

- Shorning, B. Y.; Dass, M. S.; Smalley, M. J.; Pearson, H. B., The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway and Prostate Cancer: At the Crossroads of AR, MAPK, and WNT Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (12).

- Li, G.; Rivas, P.; Bedolla, R.; Thapa, D.; Reddick, R. L.; Ghosh, R.; Kumar, A. P., Dietary resveratrol prevents development of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplastic lesions: involvement of SIRT1/S6K axis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013, 6, (1), 27-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S. B.; Rivas, P.; Yang, X.; Lai, Z.; Chen, Y.; Schadler, K. L.; Hu, M.; Reddick, R. L.; Ghosh, R.; Kumar, A. P., SIRT1 inhibition-induced senescence as a strategy to prevent prostate cancer progression. Mol Carcinog 2022, 61, (7), 702-716. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomini, F.; Favero, G.; Petroni, A.; Paroni, R.; Rezzani, R., Melatonin Modulates the SIRT1-Related Pathways via Transdermal Cryopass-Laser Administration in Prostate Tumor Xenograft. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, (20).

- Jung-Hynes, B.; Schmit, T. L.; Reagan-Shaw, S. R.; Siddiqui, I. A.; Mukhtar, H.; Ahmad, N., Melatonin, a novel Sirt1 inhibitor, imparts antiproliferative effects against prostate cancer in vitro in culture and in vivo in TRAMP model. J Pineal Res 2011, 50, (2), 140-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Hu, J.; Hou, Y.; Tao, H.; Sugimura, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, K., Melatonin inhibits lipid accumulation to repress prostate cancer progression by mediating the epigenetic modification of CES1. Clin Transl Med 2021, 11, (6), e449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Yu, S.; Jia, L.; Zou, C.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Wong, K. B.; Ng, C. F.; Chan, F. L., Orphan nuclear receptor TLX functions as a potent suppressor of oncogene-induced senescence in prostate cancer via its transcriptional co-regulation of the CDKN1A (p21(WAF1) (/) (CIP1) ) and SIRT1 genes. J Pathol 2015, 236, (1), 103-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H. H.; Ahn, C. H.; Lee, H. J.; Sim, D. Y.; Park, J. E.; Park, S. Y.; Kim, B.; Shim, B. S.; Kim, S. H., The Apoptotic and Anti-Warburg Effects of Brassinin in PC-3 Cells via Reactive Oxygen Species Production and the Inhibition of the c-Myc, SIRT1, and beta-Catenin Signaling Axis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (18).

- Karbasforooshan, H.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Karimi, G., SIRT1 and microRNAs: The role in breast, lung and prostate cancers. Exp Cell Res 2018, 367, (1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Fujita, Y.; Nozawa, Y.; Deguchi, T.; Ito, M., MiR-34a attenuates paclitaxel-resistance of hormone-refractory prostate cancer PC3 cells through direct and indirect mechanisms. Prostate 2010, 70, (14), 1501-12. [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Ge, Y. C.; Zhang, X. P.; Wu, S. Y.; Feng, J. S.; Chen, S. L.; Zhang, L. I.; Yuan, Z. H.; Fu, C. H., miR-34a inhibits cell proliferation in prostate cancer by downregulation of SIRT1 expression. Oncol Lett 2015, 10, (5), 3223-3227. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Tai, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, C.; Gu, F.; Gao, J.; Gao, S., Reducible self-assembling cationic polypeptide-based micelles mediate co-delivery of doxorubicin and microRNA-34a for androgen-independent prostate cancer therapy. J Control Release 2016, 232, 203-14. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Gan, R.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Meng, Q. H., Down-regulation of mir-221 and mir-222 restrain prostate cancer cell proliferation and migration that is partly mediated by activation of SIRT1. PLoS One 2014, 9, (6), e98833. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Huang, H.; Huang, B.; Liao, X., HSA-miR-34a-5p regulates the SIRT1/TP53 axis in prostate cancer. Am J Transl Res 2022, 14, (7), 4493-4504.

- Wen, D.; Peng, Y.; Lin, F.; Singh, R. K.; Mahato, R. I., Micellar Delivery of miR-34a Modulator Rubone and Paclitaxel in Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res 2017, 77, (12), 3244-3254. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Ren, L.; Xie, B.; Liang, Z.; Chen, J., MiR-204 enhances mitochondrial apoptosis in doxorubicin-treated prostate cancer cells by targeting SIRT1/p53 pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, (57), 97313-97322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Ma, B., The UCA1/miR-204/Sirt1 axis modulates docetaxel sensitivity of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2016, 78, (5), 1025-1031. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalinga, M.; Roy, A.; Srivastava, A.; Bhattarai, A.; Harish, V.; Suy, S.; Collins, S.; Kumar, D., MicroRNA-212 negatively regulates starvation induced autophagy in prostate cancer cells by inhibiting SIRT1 and is a modulator of angiogenesis and cellular senescence. Oncotarget 2015, 6, (33), 34446-57. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharad, S.; Petrovics, G.; Mohamed, A.; Dobi, A.; Sreenath, T. L.; Srivastava, S.; Biswas, R., Loss of miR-449a in ERG-associated prostate cancer promotes the invasive phenotype by inducing SIRT1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, (16), 22791-806. [CrossRef]

- Gaballah, M. S. A.; Ali, H. E. A.; Hassan, Z. A.; Mahgoub, S.; Ali, H. I.; Rhim, J. S.; Zerfaoui, M.; El Sayed, K. A.; Stephen, D.; Sylvester, P. W.; Abd Elmageed, Z. Y., Small extracellular vesicle-associated miR-6068 promotes aggressive phenotypes of prostate cancer through miR-6068/HIC2/SIRT1 axis. Am J Cancer Res 2022, 12, (8), 4015-4027.

- Li, G.; Zhong, S., MicroRNA-217 inhibits the proliferation and invasion, and promotes apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting sirtuin 1. Oncol Lett 2021, 21, (5), 386. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Yang, B.; Lindahl, A. J.; Damaschke, N.; Boersma, M. D.; Huang, W.; Corey, E.; Jarrard, D. F.; Denu, J. M., Identifying Dysregulated Epigenetic Enzyme Activity in Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer Development. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, (11), 2804-2814. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. H.; Choi, S. M.; Lee, S. W.; Jeh, S. U.; Hyun, J. S.; Lee, M. H.; Lee, C.; Kam, S. C.; Kim, D. C.; Lee, J. S.; Hwa, J. S., Expression Patterns of ERalpha, ERbeta, AR, SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT3 in Prostate Cancer Tissue and Normal Prostate Tissue. Anticancer Res 2021, 41, (3), 1377-1386. [CrossRef]

- Filon, M.; Yang, B.; Purohit, T. A.; Schehr, J.; Singh, A.; Bigarella, M.; Lewis, P.; Denu, J.; Lang, J.; Jarrard, D. F., Development of a multiplex assay to assess activated p300/CBP in circulating prostate tumor cells. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 738-746. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Chi, H.; Shao, J.; Shi, T.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X., Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor homodimerization mediated by acetylation of extracellular lysine promotes prostate cancer progression through the PDPK1/AKT/GCN5 axis. Clin Transl Med 2022, 12, (2), e676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Chouhan, S.; Singh, S.; Chhipa, R. R.; Ajay, A. K.; Bhat, M. K., Constitutively activated ERK sensitizes cancer cells to doxorubicin: Involvement of p53-EGFR-ERK pathway. J Biosci 2017, 42, (1), 31-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyjacova, L.; Hubackova, S.; Krejcikova, K.; Strauss, R.; Hanzlikova, H.; Dzijak, R.; Imrichova, T.; Simova, J.; Reinis, M.; Bartek, J.; Hodny, Z., Radiotherapy-induced plasticity of prostate cancer mobilizes stem-like non-adherent, Erk signaling-dependent cells. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, (6), 898-911. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, Q. R.; Wang, B.; Shao, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, T.; Huang, G.; Xia, W., Inhibition of SIRT6 in prostate cancer reduces cell viability and increases sensitivity to chemotherapeutics. Protein Cell 2013, 4, (9), 702-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, S.; Singh, S.; Athavale, D.; Ramteke, P.; Pandey, V.; Joseph, J.; Mohan, R.; Shetty, P. K.; Bhat, M. K., Glucose induced activation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma is regulated by DKK4. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 27558. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Singh, S.; Athavale, D.; Ramteke, P.; Vanuopadath, M.; Nair, B. G.; Nair, S. S.; Bhat, M. K., Sensitization of hepatocellular carcinoma cells towards doxorubicin and sorafenib is facilitated by glucosedependent alterations in reactive oxygen species, P-glycoprotein and DKK4. J Biosci 2020, 45. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Garzon, V.; Kypta, R., WNT signalling in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2017, 14, (11), 683-696. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Li, H.; Fu, H.; Zhao, S.; Shi, W.; Sun, M.; Li, Y., The SIRT3 and SIRT6 Promote Prostate Cancer Progression by Inhibiting Necroptosis-Mediated Innate Immune Response. J Immunol Res 2020, 2020, 8820355. [CrossRef]

- Jing, N.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, P.; Xu, P.; Cheng, C.; Wang, D.; Zhao, H.; He, Y.; Ji, Z.; Xin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, W.; Gong, Y.; Fan, L.; Ji, Y.; Zhuang, G.; Wang, Q.; Dong, B.; Zhang, P.; Xue, W.; Gao, W. Q.; Zhu, H. H., ADORA2A-driven proline synthesis triggers epigenetic reprogramming in neuroendocrine prostate and lung cancers. J Clin Invest 2023, 133, (24).

- Wu, M.; Seto, E.; Zhang, J., E2F1 enhances glycolysis through suppressing Sirt6 transcription in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, (13), 11252-63. [CrossRef]

- Nahalkova, J., The molecular mechanisms associated with PIN7, a protein-protein interaction network of seven pleiotropic proteins. J Theor Biol 2020, 487, 110124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F. A., The dark side of SIRT7. Mol Cell Biochem 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzel, O.; Kosem, A.; Aslan, Y.; Asfuroglu, A.; Balci, M.; Senel, C.; Tuncel, A., The Role of Pentraxin-3, Fetuin-A and Sirtuin-7 in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer. Urol J 2021, 19, (3), 196-201.

- Ding, M.; Jiang, C. Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Han, B. M.; Xia, S. J., SIRT7 depletion inhibits cell proliferation and androgen-induced autophagy by suppressing the AR signaling in prostate cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, (1), 28. [CrossRef]

- Sawant Dessai, A.; Dominguez, M. P.; Chen, U. I.; Hasper, J.; Prechtl, C.; Yu, C.; Katsuta, E.; Dai, T.; Zhu, B.; Jung, S. Y.; Putluri, N.; Takabe, K.; Zhang, X. H.; O'Malley, B. W.; Dasgupta, S., Transcriptional Repression of SIRT3 Potentiates Mitochondrial Aconitase Activation to Drive Aggressive Prostate Cancer to the Bone. Cancer Res 2021, 81, (1), 50-63. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, R.; Huang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y., Acetylation-mediated degradation of HSD17B4 regulates the progression of prostate cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, (14), 14699-14717.

- Fiaschi, T.; Marini, A.; Giannoni, E.; Taddei, M. L.; Gandellini, P.; De Donatis, A.; Lanciotti, M.; Serni, S.; Cirri, P.; Chiarugi, P., Reciprocal metabolic reprogramming through lactate shuttle coordinately influences tumor-stroma interplay. Cancer Res 2012, 72, (19), 5130-40. [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Hong, X.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jia, R., Sirtuin 4 Inhibits Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis by Modulating p21 Nuclear Translocation and Glutamate Dehydrogenase 1 ADP-Ribosylation. J Oncol 2022, 2022, 5498743. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Hu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.; Li, F., Mitochondrial PAK6 inhibits prostate cancer cell apoptosis via the PAK6-SIRT4-ANT2 complex. Theranostics 2020, 10, (6), 2571-2586. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Suh, J. Y.; Jung, Y. S.; Jung, J. W.; Kim, M. K.; Chung, J. H., Peptide switch is essential for Sirt1 deacetylase activity. Mol Cell 2011, 44, (2), 203-13. [CrossRef]

- Panathur, N.; Dalimba, U.; Koushik, P. V.; Alvala, M.; Yogeeswari, P.; Sriram, D.; Kumar, V., Identification and characterization of novel indole based small molecules as anticancer agents through SIRT1 inhibition. Eur J Med Chem 2013, 69, 125-38. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Chu, P. C.; Chuang, H. C.; Hung, W. C.; Kulp, S. K.; Chen, C. S., Targeting the oncogenic E3 ligase Skp2 in prostate and breast cancer cells with a novel energy restriction-mimetic agent. PLoS One 2012, 7, (10), e47298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salata, G. C.; Pinho, C. F.; de Freitas, A.; Aquino, A. M.; Justulin, L. A.; Mendes, L. O.; Goncalves, B. F.; Delella, F. K.; Scarano, W. R., Raloxifene decreases cell viability and migratory potential in prostate cancer cells (LNCaP) with GPR30/GPER1 involvement. J Pharm Pharmacol 2019, 71, (7), 1065-1071. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ahmad, N.; Liu, X., Combining p53 stabilizers with metformin induces synergistic apoptosis through regulation of energy metabolism in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, (6), 840-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, V.; Hessenkemper, W.; Rodiger, J.; Kyrylenko, S.; Kraft, F.; Baniahmad, A., Sodium butyrate induces cellular senescence in neuroblastoma and prostate cancer cells. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2011, 7, (1), 265-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, T.; Iizumi, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Masuda, M.; Morita, M.; Aono, Y.; Toriyama, S.; Oishi, M.; Goi, W.; Sakai, T., Resveratrol directly targets DDX5 resulting in suppression of the mTORC1 pathway in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis 2016, 7, (5), e2211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulla, V. K.; Sriram, D. S.; Viswanadha, S.; Sriram, D.; Yogeeswari, P., Energy-Based Pharmacophore and Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure--Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) Modeling Combined with Virtual Screening To Identify Novel Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Silent Mating-Type Information Regulation 2 Homologue 1 (SIRT1). J Chem Inf Model 2016, 56, (1), 173-87.

- Sener, T. E.; Tavukcu, H. H.; Atasoy, B. M.; Cevik, O.; Kaya, O. T.; Cetinel, S.; Dagli Degerli, A.; Tinay, I.; Simsek, F.; Akbal, C.; Buttice, S.; Sener, G., Resveratrol treatment may preserve the erectile function after radiotherapy by restoring antioxidant defence mechanisms, SIRT1 and NOS protein expressions. Int J Impot Res 2018, 30, (4), 179-188. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. X.; Yan, C.; Yang, X.; Zhu, P. Y.; Cui, W. W.; Ye, C.; Hu, K.; Lan, T.; Huang, L. Y.; Wang, W.; Ma, P.; Qi, S. H.; Gu, B.; Luo, L., Enhanced autophagy promotes radiosensitivity by mediating Sirt1 downregulation in RM-1 prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 609, 84-92. [CrossRef]

- Madhav, A.; Andres, A.; Duong, F.; Mishra, R.; Haldar, S.; Liu, Z.; Angara, B.; Gottlieb, R.; Zumsteg, Z. S.; Bhowmick, N. A., Antagonizing CD105 enhances radiation sensitivity in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, (32), 4385-4397. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Rodriguez, J. M.; Sanchez, B. G.; Sebastian-Martin, A.; Diaz-Yuste, A.; Sanchez-Chapado, M.; Palacin, A. M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, C.; Bort, A.; Diaz-Laviada, I., Resistance to 2-Hydroxy-Flutamide in Prostate Cancer Cells Is Associated with the Downregulation of Phosphatidylcholine Biosynthesis and Epigenetic Modifications. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (21).

- Cevatemre, B.; Bulut, I.; Dedeoglu, B.; Isiklar, A.; Syed, H.; Bayram, O. Y.; Bagci-Onder, T.; Acilan, C., Exploiting epigenetic targets to overcome taxane resistance in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, (2), 132. [CrossRef]

- Burton, K.; Shaw, L.; Morey, L. M., Differential effect of estradiol and bisphenol A on Set8 and Sirt1 expression in prostate cancer. Toxicol Rep 2015, 2, 817-823. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Hu, S. S.; Yang, L.; Wang, M.; Long, J. D.; Wang, B.; Han, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J. G.; Liu, D.; Liu, H., Discovery of 5-Benzylidene-2-phenyl-1,3-dioxane-4,6-diones as Highly Potent and Selective SIRT1 Inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett 2021, 12, (3), 397-403. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanella, L.; Di Giacomo, C.; Acquaviva, R.; Barbagallo, I.; Cardile, V.; Kim, D. H.; Abraham, N. G.; Sorrenti, V., Apoptotic markers in a prostate cancer cell line: effect of ellagic acid. Oncol Rep 2013, 30, (6), 2804-10. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C. J.; Chang, C. L.; Hu, M. H.; Liao, C. H.; Lai, G. M.; Chiou, T. J.; Ho, H. L.; Kuo, H. C.; Yang, Y. Y.; Whang-Peng, J.; Chuang, S. E., Drastic Synergy of Lovastatin and Antrodia camphorata Extract Combination against PC3 Androgen-Refractory Prostate Cancer Cells, Accompanied by AXL and Stemness Molecules Inhibition. Nutrients 2023, 15, (21).

- Guo, S.; Ma, B.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Jia, Y., Astragalus Polysaccharides Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Lipid Metabolism Through miR-138-5p/SIRT1/SREBP1 Pathway in Prostate Cancer. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 598. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Hearn, K.; Parry, C.; Rashid, M.; Brim, H.; Ashktorab, H.; Kwabi-Addo, B., Mechanism of Antitumor Effects of Saffron in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2023, 16, (1).

- Tavares, M. E. A.; Pinto, A. P.; da Rocha, A. L.; Sampaio, L. V.; Correia, R. R.; Batista, V. R. G.; Veras, A. S. C.; Chaves-Neto, A. H.; da Silva, A. S. R.; Teixeira, G. R., Combined physical exercise re-synchronizes expression of Bmal1 and REV-ERBalpha and up-regulates apoptosis and metabolism in the prostate during aging. Life Sci 2024, 351, 122800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Dai, R.; Deng, N.; Su, W.; Liu, P., Exosomal miR-1275 Secreted by Prostate Cancer Cells Modulates Osteoblast Proliferation and Activity by Targeting the SIRT2/RUNX2 Cascade. Cell Transplant 2021, 30, 9636897211052977. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jin, F.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; He, B., Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted SIRT2 inhibitors. Bioorg Chem 2024, 153, 107784. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelmann, A.; Schiedel, M.; Wossner, N.; Merz, A.; Herp, D.; Hammelmann, S.; Colcerasa, A.; Komaniecki, G.; Hong, J. Y.; Sum, M.; Metzger, E.; Neuwirt, E.; Zhang, L.; Einsle, O.; Gross, O.; Schule, R.; Lin, H.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M., Development of a NanoBRET assay to validate inhibitors of Sirt2-mediated lysine deacetylation and defatty-acylation that block prostate cancer cell migration. RSC Chem Biol 2022, 3, (4), 468-485. [CrossRef]

- Colcerasa, A.; Friedrich, F.; Melesina, J.; Moser, P.; Vogelmann, A.; Tzortzoglou, P.; Neuwirt, E.; Sum, M.; Robaa, D.; Zhang, L.; Ramos-Morales, E.; Romier, C.; Einsle, O.; Metzger, E.; Schule, R.; Gross, O.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M., Structure-Activity Studies of 1,2,4-Oxadiazoles for the Inhibition of the NAD(+)-Dependent Lysine Deacylase Sirtuin 2. J Med Chem 2024, 67, (12), 10076-10095. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Xie, Q. R.; Li, F.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Wong, A. S. T.; Sha, J.; Xia, W., Targeted inhibition of SIRT6 via engineered exosomes impairs tumorigenesis and metastasis in prostate cancer. Theranostics 2021, 11, (13), 6526-6541. [CrossRef]

- Sociali, G.; Galeno, L.; Parenti, M. D.; Grozio, A.; Bauer, I.; Passalacqua, M.; Boero, S.; Donadini, A.; Millo, E.; Bellotti, M.; Sturla, L.; Damonte, P.; Puddu, A.; Ferroni, C.; Varchi, G.; Franceschi, C.; Ballestrero, A.; Poggi, A.; Bruzzone, S.; Nencioni, A.; Del Rio, A., Quinazolinedione SIRT6 inhibitors sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutics. Eur J Med Chem 2015, 102, 530-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M. H.; Hui, S. C.; Chen, Y. S.; Chiou, H. L.; Lin, C. Y.; Lee, C. H.; Hsieh, Y. H., Norcantharidin combined with paclitaxel induces endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated apoptotic effect in prostate cancer cells by targeting SIRT7 expression. Environ Toxicol 2021, 36, (11), 2206-2216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Cai, R.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; An, J.; An, W.; Tao, Y.; Yu, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M., Acetylated KHSRP impairs DNA-damage-response-related mRNA decay and facilitates prostate cancer tumorigenesis. Mol Oncol 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sirtuin | Inhibitor of Sirtuin | Mode of Inhibitor Action | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | DBC1 | Enhances chemosensitivity by inhibiting the ESA region of SIRT1 | [188] |

| IT-14 | Inhibits SIRT1's deacetylation activity, reducing prostatic hyperplasia | [189] | |

| Tenovin-1 | Combined with Plk1 inhibitor BI2536 to augment anti-neoplastic efficacy of metformin | [192] | |

| Sodium butyrate | Induces senescence and alters proto-oncogene expression in PCa cells | [193] | |

| Resveratrol | Triggers apoptosis by degrading DDX5 and inhibiting mTORC1 signaling | [194] | |

| Selective inhibitor 12n | Competitive inhibition of acetyl peptide substrates and noncompetitive towards NAD+ | [202] | |

| Ellagic acid | Downregulates SIRT1 and induces oxidative stress to promote apoptosis | [203] | |

| Astragalus polysaccharides (APS) | Reduces SIRT1 expression and disrupts lipid metabolism | [205] | |

| Saffron extract | Downregulates SIRT1, contributing to apoptosis through DNA repair interference | [206] | |

| SIRT2 | Cancer-derived exosomal microRNA-1275 | Downregulates SIRT2 to enhance osteoblast activity, facilitating bone metastasis | [208] |

| Sirtuin-Rearranging Ligands (SirReals) | Suppresses deacetylation and defatty-acylation, reducing c-Myc levels | [209] | |

| Oxadiazole-based analogues | Substrate-competitive and cofactor-noncompetitive interactions reduce viability | [211] | |

| SIRT6 | Quinazolinedione compounds | Inhibits SIRT6, increasing histone acetylation and enhancing glucose uptake | [213] |

| SIRT7 | NCTD-PTX combination | Downregulates SIRT7, inducing apoptosis and reducing cell viability | [214] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).