1. Introduction

Nipah virus (NiV) is an emergent and highly pathogenic zoonotic paramyxovirus in the genus: Henipavirus. NiV first emerged in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999. NiV was associated with an outbreak of severe febrile encephalitis associated with human deaths reported in Peninsular Malaysia beginning in late September 1998 [

1]. Later, NiV outbreaks led to several outbreaks since 2001 in Bangladesh, India, Singapore, Malaysia, and other countries [

2]. NiV targets vascular endothelial and neuronal cells causing severe encephalitic or respiratory syndrome with case fatality rates ranging from 40 to 100% in humans [

2,

3,

4]. Due to its high mortality, ease of transmission between species and lack of effective therapy or prophylaxis, NiV is categorized as a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) pathogen. NiV requires the coordinated action of envelope glycoproteins G and F to recognize, bind, trigger and entry into susceptible cells. NiV binds to ephrin-B2 or -B3 receptors that are expressed on microvascular endothelial cells to gain entry [

5,

6,

7,

8]. NiV glycoprotein G is responsible for the receptor binding resulting in conformational changes in G and triggering F glycoprotein. After triggering, the pre-fusion F will be activated to a post-fusion F that harpoons itself into the adjacent cells causing the development of syncytium. Syncytia represent a cellular structure formed due to multiple cell fusions of individual mononuclear cells [

5,

9,

10]. Endothelial syncytium formation is a peculiar hallmark of NiV infection leading to cell destruction, inflammation, and hemorrhage. The syncytium leads to further spread, inflammation, and damage to endothelial cells and neurons [

11]. As a result, NiV is listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) R&D Blueprint list of priority pathogens [

12]. Since 2001, India witnessed six Nipah virus outbreaks and the first outbreak was reported in the state of West Bengal with a case fatality (CFR) of 68%. Subsequently, outbreaks have been reported from West Bengal and Kerala with high CFR [

13]. To date, only limited data are available on NiV treatment strategies due to the pathogenic nature of the virus and experiments requiring BSL-4 facilities. No approved vaccines or treatments that specifically target NiV are available, and quarantine has been the predominant measure to limit the spread of the virus [

14].

Substantial work has been carried out on the role of flavonoids as potential antivirals against several animal and human viruses, including COVID-19. Flavonoids were shown to exhibit their antiviral activity by (i) hindering the viral entry; (ii) interfering with the host receptor binding; (iii) inhibiting the function of the host-receptor itself; (iv) hampering the viral replication process and/or viral assembly; (v) block the release and cell-to-cell movement; (vi) enhanced immune responses [

15,

16,

17]. Myricetin (MYR) is a flavonoid compound found in vegetables, fruits, and tea possess antioxidant properties [

18,

19,

20], antimicrobial, anti-thrombotic, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory properties [

21,

22,

23]. MYR has been shown to exhibit antiviral properties on several pathogenic viruses which include HIV, HSV, SARS, SARS-CoV-2 [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In this study, the therapeutic potential of MYR as an antiviral agent and its role in mitigating the syncytial development triggered by NiV-F and -G envelope glycoproteins in-vitro was investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

The cell lines used in this study was purchased from the National Center for Cell Sciences (NCCS, Pune, India). Two NiV permissive mammalian cell lines (expressing ephrin-B2 receptor on cell surface) and a non-permissive cell line (very few ephrin-B2) were used in this study. The NiV permissive cells lines are (i) human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) and (ii) African green monkey kidney epithelial cells (Vero). The non-permissive cell line used in this study was the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line. HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) while CHOs and Vero cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco, USA), both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermofisher Scientific, USA), 50 IU of penicillin ml-1 (Sigma, USA), streptomycin ml-1 (Sigma, USA), and 2 mM glutamine (Sigma, USA). Myricetin (3,3',4',5,5',7-Hexahydroxyflavone) MW-318.23 g/mol (

Figure 1a) purchased from the Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (TCI, India) was used in all the in-vitro assays carried out in this study. MYR stock solution was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Seven testing concentrations of MYR (10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μM) were evaluated in the study to assess the antiviral potential of MYR.

Codon-optimized wild-type (WT) Nipah virus attachment G (NiV-G) and fusion glycoprotein F (NiV-F) were synthesized in pcDNA3.1 vector construct (GenScript, USA). The NiV-G is tagged at the C-terminus with hemagglutinin (HA) tag and the NiV-F was tagged at the C-terminus with AU1 tag (Figure1b). The plasmid construct design and organization were reported earlier [

5]. The NiV-G encodes a 602 amino acid attachment glycoprotein (~1.8 kb nucleotides) and the NiV-F encodes a 546 amino acid (~1.6 kb nucleotides) fusion glycoprotein respectively. The inclusion of tags in the WT F and G plasmids facilitates the detection of expressed viral proteins using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with tag-specific primary and secondary antibodies.

The lyophilized pcDNA3.1 vector constructs encoding the wild type (WT) F and G were suspended in TE buffer and used for transformation of E. coli DH5-α competent cells following standard molecular biology protocols [

32]. Following blue-white screening, F and G plasmid DNA was isolated from the bacterial cultures using Plasmid mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The confirmation of F and G sequence in the pcDNA3.1 vector was carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with forward (CMV-Fwd) and reverse (BGH-Rev) primers flanking the multiple cloning site (MCS). The resulting PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels.

Cell viability (cytotoxicity) of MYR on the three cell lines used in this study was carried out using the MTT assay (EZcount™ MTT Cell Assay Kit, Himedia, India) in 96-well immunoplates (Nunc, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Different concentrations of MYR (10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM) were tested on the three cell lines to determine cytotoxicity. Briefly, cells at 70% confluency were treated with MYR diluted in DMEM (100 μL per well). Plates were incubated at 37°C in biological CO2 incubator (5%) for 24h. The multi-well plates were treated with 15 μL of dye for the MTT assay and incubated for 4h. Later, the cell viability (cytotoxicity) was determined by spectrophotometric analysis at 570 nm using a microplate reader (uQuant BioTek Spectrophotometer, USA). Viability of MYR-treated cells was calculated as a percentage relative to values obtained with DMSO treated cells.

NiV-F and -G plasmids (2:1 ratio) were transfected into 293T or Vero cells at ~70% confluence at 2 µg/well in 6-well plates. The concentration of the F and G plasmids used for transfection in 12- or 24-well plates were adjusted accordingly. Different combinations of NiV F and G plasmids were included in the study to determine the progress and inhibition of syncytia in permissive and non-permissive cell lines. The different transfection combinations were (i) NiV-F only (F+pC3.1); (ii) NiV-G only (G+pC3.1); (iii) NiV F+G (co-transfection). Positive controls were NiV F+G (co-transfected) without MYR treatment and negative controls consisting of only pCDNA3.1 transfected cells. CHO cells were included as additional negative control in all the experiments (

Supplementary Table S1). In cells that were transfected only with F or G alone, the final plasmid DNA concentration in each well was adjusted with pcDNA3.1. Briefly, on day zero, the 6-well plates were seeded separately with HEK293T, VERO, or CHO cells (~2x106) respectively. The growth medium used was either DMEM or MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After the cells reached 70% confluence on Day-1, cells were transfected with NiV-F and(or) -G plasmids using Lipofectamine-3000 transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Before the cells were fixed or treated with different concentrations of MYR, the growth medium was aspirated with an automatic aspirator and the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1% FBS.

Time-of-addition experiments were designed to investigate the antiviral potential of MYR on syncytial (cell-to-cell fusion) progression in HEK293T, Vero and CHO cells at two different stages after the completion of transfection. MYR was diluted to the required concentrations in MEM or DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and added to the cells with different combinations of F and G plasmids (

Supplementary Table S1). MYR was added to the cells at 1h and 6h post-transfection. The cells were washed once with PBS containing 1% FBS before the addition of MYR diluted in the growth medium. All the experiments were carried out in 6-well plates (Nunc, USA) unless specified. Each of the MYR concentration was tested in triplicate to assess the effective inhibitory concentration.

Syncytial development, progression and quantification in the multi-well plates treated with different concentrations of MYR were observed using a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus-CKX53, Japan) 18h post-transfection. Ten fields per well of 6-well plates were observed under 100X magnification for the quantification of syncytia. A total of 30 fields were observed for each MYR treatment. Wells transfected with NiV F+G only (without MYR) were considered as positive control while cells transfected with (i) pCDNA3.1 only; (ii) F only; (iii) G only were considered as negative controls. CHO cells (non-permissive) were included as additional negative control. 18-24h after the addition of MYR, the cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to halt further syncytial development in the wells and to facilitate quantification of syncytia. The percentage of syncytial inhibition was measured as the reduction in the number of syncytia in each well in comparison to the positive and negative controls.

To determine if MYR could block or interfere with the expression of NiV G and F in HEK293T cells, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) [

33] was carried out followed by Western blotting. The non-transfected, transfected (without treatment with MYR), and antiviral-treated cells were harvested 18h after treatment with MYR in 6-well plates. Following transfection with NiV F and G plasmids, the cells were harvested from each well using cell lysis buffer (Genei, India) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal volumes of the protein lysate were loaded on 12% PAGE gels containing SDS, followed by membrane transfer onto a nitrocellulose membrane (NCM) for probing with antibodies against F and G glycoproteins. Primary and secondary antibodies were used for the detection of expressed F and G glycoproteins in transfected cells by Western blotting. NiV-G glycoprotein was detected with anti-HA tag antibody (the primary antibody was rabbit anti-HA antibody (1:500-1000 dilution) while the secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:1000-2000 dilution) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). The F protein was detected using anti-AU1 antibody (primary antibody was goat anti-AU1 polyclonal antibody) (1:1000-2000 dilution) and the secondary antibody used was rabbit anti-goat antibody (1:1000-5000 dilution) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) respectively. The band intensities from the same volume of each lysate were determined.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of NiV-F and G Plasmids

Each of the transformed recombinant F and G DH5α colonies were picked and plasmid DNA isolation was carried out. PCR was performed using F and G plasmid DNA and PCR products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels. PCR products yielded the expected size of F and G sequences. The NiV-F insert yielded ~1.6 kilo basepairs and NiV-G insert generated ~1.8 kilo basepairs respectively (

Supplementary Figure S1a).

3.2. MTT Assay

Of the seven different MYR concentrations tested, exhibited a mild cytotoxicity of ~10-15% in 250 μM; 70-80% in 500 μM and 100% cytotoxicity was observed in 1000 μM in all the three cell lines tested. The remaining lower MYR concentrations did not alter morphology or the normal cellular functions (

Supplementary Figure S1b). Based on the results obtained from the MTT assay, in-vitro testing of MYR was limited to 10, 25, 50, 100, 250 and 500 μM respectively.

3.3. Transfection & Syncytia Development

Quantifiable syncytia were observed in the multi-well plates at 12-18h post-transfection whereas, 24h post-transfection, the individual syncytia extensively fused to form giant syncytia. Quantification was carried out 18h post-transfection. Cells that were co-transfected with NiV F and G developed syncytia and were used as positive control. Cells transfected with NiV-F alone, G alone, or pcDNA3 did not develop any syncytia and were included as negative controls (

Figure 2). No syncytia were observed in non-permissive CHO cells which therefore served as an additional negative control.

3.4. Quantification of Syncytia and Western Blotting

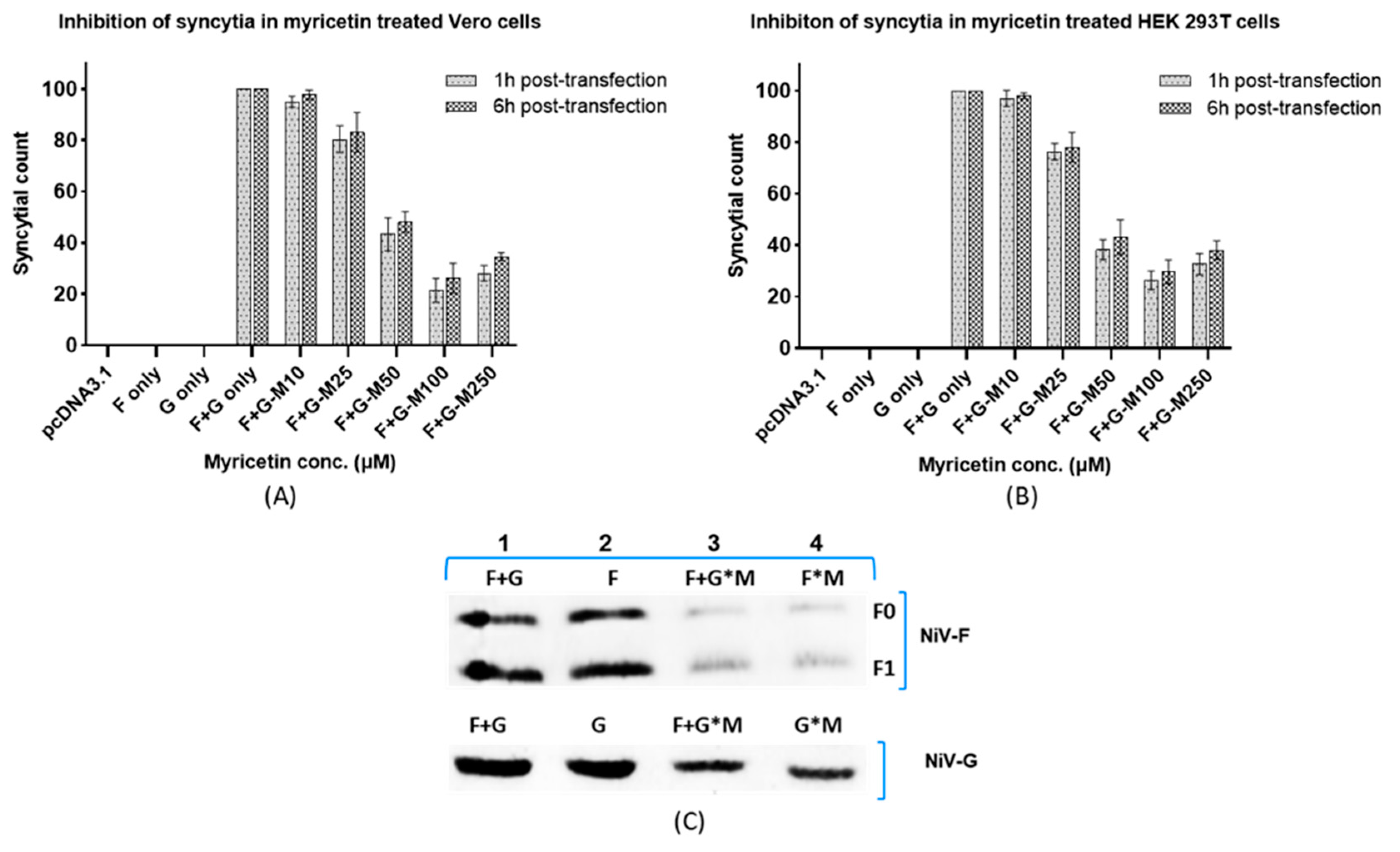

MYR effectively inhibited syncytial development in HEK 293T and Vero cells when added 1h and 6h following transfection. The percentage of syncytia inhibition was determined by normalizing the syncytial count in positive control wells (F+G without MYR) to 100% and compared to the inhibition percentage in MYR treated HEK and Vero cells. Syncytia were more prominent and measurable in Vero cells compared to HEK 293T cells. Though syncytia started to develop 6h after the transfection, the size and number of syncytia increased during a 12h period post-transfection. Effective inhibition of syncytia was observed at 50 μM and 100 μM concentration in Vero (

Figure 3) and HEK 293T (

Figure 4). Though the syncytial inhibition was also observed at 250 μM, about 10% cells displayed cytotoxicity. The highest percentage of syncytial inhibition (64-80%) was observed in HEK 293T and Vero cells when 100 μM MYR was added 1h following transfection. Syncytial inhibition was prominent when MYR was added 6h following transfection. However, the overall syncytial count was reduced by 5-10% compared to MYR addition 1h post-transfection. These results indicated the effectiveness of MYR when added 6h post-transfection which allowed sufficient time for the NiV F and G glycoproteins to be expressed in the cells after the transfection (

Figure 5 A and B). Due to the cytotoxicity of MYR at 500 μM, these results were excluded from the analysis. The protein lysate with and without MYR treated HEK293T cells were separated by SDS-PAGE gel followed by Western blotting. Compared to the cells without MYR, a marked reduction in the amount of F and G expression was detected in the samples treated with MYR at 100 μM (

Figure 5C). These results indicated that MYR possibly interfered with the expression levels of both NiV F and G glycoproteins in-vitro.

4. Discussion

Studies on the understanding of Nipah virus (NIV) F and G envelope glycoprotein interactions and the syncytial development are of great interest in understanding the pathogenesis of NiV infection towards the development of potential antiviral strategies. In this study, the antiviral potential of MYR was established in two different NiV permissive mammalian cell lines, HEK 293T and Vero. The role of MYR in inhibiting the progression of syncytial development was evaluated by different experimental approaches in-vitro. These observations are significant given the severity of virus infection in causing severe and acute life threatening NiV symptoms. Syncytium formation in virus susceptible cells is the pathological hallmark of NIV infections. NiV infections are known to be characterized by the formation of endothelial syncytia, leading to inflammation and hemorrhage [

1,

11,

34,

35,

36]. The coordinated action of NiV F and G glycoproteins results in cell-to-cell fusion of adjoining cells, eventually progressing to severe pathological symptoms such as meningitis and even death if untreated. The inhibition of syncytial development demonstrated by MYR in this study showed a dose-dependence (

Supplementary Figure S1b). MYR at 500 μM was cytotoxic in all the cells lines tested in this study. At 250 μM, MYR exhibited a ~10% cytotoxicity in HEK 293T and Vero cells were also reflected in the quantification of syncytia at higher MYR concentrations. In both the time-of-addition experiments (1h and 6h post-transfection), MYR exhibited antiviral potential in inhibiting the syncytial development. A ~5-10% overall reduction in the syncytial count was noticed when MYR was added 6h post-transfection. These results indicate that MYR was still effective in inhibiting syncytia when added at a later stage after transfecting the cells with NiV F and G. Reduction in the expression levels of NiV F and G glycoproteins in Western blot would likely be attributed to one or several possible roles of MYR (i) masking key amino acid moieties on the surface of NiV F and G that lead to a reduced detection levels; (ii) interfere with the binding affinity of G to ephrinB2/B3 receptors (iii) limiting F and G interactions that led to a reduction in syncytial count. In earlier studies, MYR was reported to block Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection by directly interacting with the viral gD protein. This interaction disrupts HSV gD attachment to host cells and viral fusion with the host cell membrane [

37]. MYR played an antiviral role in the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 via interfering with the virus spike protein from binding to its receptor ACE2 [

30]. The antiviral activity of MYR against HIV-1 was determined due to a significant reduction in the binding of HIV-1 virions to SEVI fibrils [

38]. Additionally, MYR demonstrated antiviral properties in inhibiting Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) replication cycle through the upregulation of the transcription levels in the NF-kB and IRF7 pathways suggesting a modulating effect of host immune responses inside the cell [

17]. Currently, there are no approved therapeutics available for treating NiV infection in humans. A recent study reported that 4′-chloromethyl-2′-deoxy-2′-fluorocytidine (ALS-8112), was found to reduce NiV titer and syncytia formation in vitro [

39]. In this study, MYR was effective in inhibiting the syncytial development in HEK 293T and Vero cells indicating an antiviral potential against NiV infection in-vitro. The findings of this study provide valuable preliminary insights into the antiviral potential of MYR against NiV in vitro. Whether MYR had a specific or stochastic role on the NiV F and G glycoproteins needs further investigation in future studies. The outcomes of this study need to be replicated in other susceptible cell lines and experimental hosts to further the antiviral scope of MYR and derivatives as preventive line of defense against NiV infections.

5. Conclusions

Based on this study, it can be concluded that MYR exhibits effective antiviral potential in inhibiting the syncytial development triggered by NiV F and G glycoproteins in-vitro. Further studies are recommended to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the antiviral activity of MYR and its potential applications in in-vivo models. Additionally, the evaluation of the cytotoxicity and safety profile of MYR in animal and human studies is crucial for its progression towards clinical trials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, BV and MR; methodology, BV and MR; software, MR.; validation, BV and MR; formal analysis, MR; investigation, MR; resources, BV, CC, MR; data curation, MR; writing—original draft preparation, BV and MR; writing—BV, MR, CC, SP.; visualization, BV and MR; supervision, BV; project administration, BV and MR; funding acquisition, BV.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Engineering Research Board-Extramural Research Funding (SERB-EMRF), Department of Science and Technology, India (DST-SERB-EMRF) under grant number: EMR/2016/003301 to BV.

Acknowledgments

Department of Biotechnology, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation (K. L. deemed to be University), Vaddeswaram, Guntur, A.P. for providing necessary facilities for carrying out this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Chua, K.B.; Bellini, W.J.; Rota, P.A.; Harcourt, B.H.; Tamin, A.; Lam, S.K.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Zaki, S.R.; Shieh, W.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Gubler, D.J.; Roehrig, J.T.; Eaton, B.; Gould, A.R.; Olson, J.; Field, H.; Daniels, P.; Ling, A.E.; Peters, C.J.; Anderson, L.J.; Mahy, B.W. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus, Science 2000, 288, 1432-5. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, V.P.; Hossain, M.J.; Parashar, U.D.; Ali, M.M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Kuzmin, I.; Niezgoda, M.; Rupprecht, C.; Bresee, J.; Breiman, R.F. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh, Emerg Infect Dis 2004, 10, 2082-2087, doi.org/10.3201/eid1012.040701.

- Eaton, B.T.; Broder, C.C.; Middleton, D.; Wang, L.F. Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4, 23-35, doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1323.

- Stone, R. Breaking the Chain in Bangladesh. Science 2011, 331,1128-1131. [CrossRef]

- Negrete, O.A.; Levroney, E.L.; Aguilar, H.C.; Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A.; Nazarian, R.; Tajyar, S.; Lee, B. EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature 2005, 436, 401-405, doi.org/10.1038/nature03838.

- Negrete, O.A.; Wolf, M.C.; Aguilar, H.C.; Enterlein, S.; Wang, W.; Mühlberger, E.; Su, S.V.; Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A.; Flick, R.; Lee, B. Two Key Residues in EphrinB3 Are Critical for Its Use as an Alternative Receptor for Nipah Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2-e7, doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0020007.

- Bonaparte, M.I.; Dimitrov, A.S.; Bossart, K.N.; Crameri, G.; Mungall, B.A.; Bishop, K.A.; Choudhry, V.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Wang, L.F.; Eaton, B.T.; Broder, C.C. Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2005, 26, 102, 10652-7, doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504887102.

- Bowden, T.A.; Aricescu, A.R.; Gilbert, R.J.; Grimes, J.M.; Jones, E.Y.; Stuart, D.I. Structural basis of Nipah and Hendra virus attachment to their cell-surface receptor ephrin-B2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 567-572, doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1435.

- Aguilar, H.C.; Ataman, Z.A.; Aspericueta, V.; Fang, A.Q.; Stroud, M.; Negrete, O.A.; Kammerer, R.A.; Lee, B. A novel receptor-induced activation site in the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein (G) involved in triggering the fusion glycoprotein (F). J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 1628-1635, doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M807469200.

- Aguilar, H.C.; Iorio, R.M. Henipavirus membrane fusion and viral entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012, 359, 79-94, doi.org/10.1007/82_2012_200.

- Wong, K.T.; Shieh, W-J.; Kumar, S.; Norain, K.; Abdullah, W.; Guarner, J.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Chua, K.B.; Lam, S.K.; Tan, C.T. Nipah virus infection: pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am. J. Pathol 2002, 161, 2153–2167, doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64493-8.

- WHO, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on healthresearch-and-development/analyses-and-syntheses/who-r-d-blueprint/who-r-d-roadmaps (accessed on 12/10/2024).

- WHO, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON490 (accessed on 12/10/2024).

- Nahar, N.; Mondal, U.K.; Hossain, M.J.; Uddin Khan, M.S.; Sultana, R.; Gurley, E.S.; Luby, S.P. Piloting the promotion of bamboo skirt barriers to prevent Nipah virus transmission through date palm sap in Bangladesh. Glob. Health Promot Int 2013, 28, 378-386, doi.org/10.1093/heapro /das020.

- Wang, L.; Song, J.; Liu, A.; Xiao, B.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Lu, Y.; Du, G. Research Progress of the Antiviral Bioactivities of Natural Flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect 2020, 10, 271–283, 10.1007/s13659-020-00257-x.

- Kato, Y.; Higashiyama, A.; Takaoka, E.; Nishikawa, M.; Ikushiro, S. Food phytochemicals, epigallocatechin gallate and myricetin, covalently bind to the active site of the coronavirus main protease in vitro. Adv. Redox. Res. 2021, 3, 100021, doi.org/10.1016/j.arres.2021.100021.

- Peng, S.; Fang, C.; He, H.; Song, X.; Zhao, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Jia, R.; Yin, Z. Myricetin exerts its antiviral activity against infectious bronchitis virus by inhibiting the deubiquitinating activity of papain-like protease. Poult Sci. 2022, 101, 101626, doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101626.

- Ong, K. C.; Khoo, H. E. Biological effects of myricetin. Gen Pharmacol. 1997, 29, 121-126, doi.org/10.1016/S0306-3623(96)00421-1.

- Ross, J.A.; Kasum, C.M. Dietary flavonoids: bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22,19-34, doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957.

- Semwal, D. K.; Semwal, R. B.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A. Myricetin: A dietary molecule with diverse biological activities. Nutrients, 2016, 8, 90, doi.org/10.3390/nu8020090.

- Cushnie, T.T.; Lamb, A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 2005, 26, 343-356, doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002.

- Kim, J.E.; Kwon, J.Y.; Lee, D.E.; Kang, N.J.; Heo, Y.S.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, H.J. MKK4 is a novel target for the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression by myricetin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 412-421, doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.027.

- Santhakumar, A.B., Bulmer, A.C. and Singh, I., 2014. A review of the mechanisms and effectiveness of dietary polyphenols in reducing oxidative stress and thrombotic risk. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 1-21, doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12177.

- Lyu, S.Y.; Rhim, J.Y.; Park, W.B. Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) in vitro. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 1293-1301, doi.org/10.1007/BF02978215.

- Yu, M.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Chin, Y.W.; Jee, J.G.; Keum, Y.S.; Jeong, Y.J. 2012. Identification of myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4049-4054. [CrossRef]

- Pasetto, S.; Pardi, V.; Murata, R. M. Anti-HIV-1 activity of flavonoid myricetin on HIV-1 infection in a dual-chamber in vitro model. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115323, doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115323.

- Li, W.; Xu, C.; Hao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, W. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus by myricetin through targeting viral gD protein and cellular EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway. Antiviral Res 2020, 177, 104714, doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104714.

- Hu, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, H.; Yin, Z.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; Zhao, X.; Yin, L.; Ye, G.; Zou, Y-F.; Tang, H.; Jia, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Song, X. Myricetin inhibits pseudorabies virus infection through direct inactivation and activating host antiviral defense. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 985108. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; He, J.; Yang, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, R.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Myricetin possesses the potency against SARS-CoV-2 infection through blocking viral-entry facilitators and suppressing inflammation in rats and mice. Phytomedicine, 2023, 116, 154858, doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154858.

- Agrawal, P. K.; Agrawal, C.; Blunden, G. Antiviral and Possible Prophylactic Significance of Myricetin for COVID-19. Nat. Prod. Comm. 2023, 18, 1-15, doi.org/10.1177/1934578X231166283.

- Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, X.; Su, T.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Yin, Z.; Jia, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, X. The antiviral activity of myricetin against pseudorabies virus through regulation of the type I interferon signaling pathway. J. Virol, 2025, 99, e01567-24, doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01567-24.

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed.; Vol. 1, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 2001.

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 1970, 227, 680-685, doi.org/10.1038/227680a0.

- Erbar, S.; Maisner, A. Nipah virus infection and glycoprotein targeting in endothelial cells. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 1-10, doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-305.

- Lam, S.K.; Chua, K.B. 2002. Nipah virus encephalitis outbreak in Malaysia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, S48-S51, doi.org/10.1086/338818.

- Lo, M.K.; Miller, D.; Aljofan, M.; Mungall, B.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Bellini, W.J.; Rota, P.A. 2010. Characterization of the antiviral and inflammatory responses against Nipah virus in endothelial cells and neurons. Virology, 2010, 404, 78-88.

- Li, W.; Xu, C.; Hao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, W. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus by myricetin through targeting viral gD protein and cellular EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway. Antiviral Res. 2020, 177, 104714, doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104714.

- Ren, R.; Yin, S.; Lai, B.; Ma, L.; Wen, J.; Zhang, X.; Lai, F.; Liu, S.; Li, L. Myricetin antagonizes semen-derived enhancer of viral infection (SEVI) formation and influences its infection-enhancing activity. Retrovirology, 2018, 15, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.K.; Amblard, F.; Flint, M.; Chatterjee, P.; Kasthuri, M.; Li, C.; Russell, O.; Verma, K.; Bassit, L.; Schinazi, R.F.; Nichol, S.T. Potent in vitro activity of β-D-4ʹ-chloromethyl-2ʹ-deoxy-2ʹ-fluorocytidine against Nipah virus. Antiviral Res. 2020, 175, 104712. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).