1. Introduction

Country of origin (COO) has developed into a substantive area of investigation within consumer behavior and marketing research over the past few decades. Several studies have proved that the country associated with a product greatly influences consumers’ perceptions, evaluations, and purchase behavior (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Peterson & Jolibert, 1995; Pharr, 2005). An extensive body of literature has examined country of origin as a prominent extrinsic product cue and source of competitive advantage in shaping consumer decision-making as well as marketing strategy in a globalized marketplace (Josiassen et al., 2008). Conceptualizations of the country of origin tend to emphasize the predictive capacity of the “made in” label regarding inferred product attributes and quality judgments (Hong & Kang, 2006; Roth & Romeo, 1992). According to Bilkey and Nes (1982), country of origin represents an intangible asset based on the place of manufacture and parent company domicile that generates certain perceptions about the attributes of a product. These perceptions subsequently impact product evaluations and purchase likelihood (Wang & Lamb, 1983). Similarly, Nagashima (1970) defined country of origin as the picture, reputation, and stereotype consumers associate with products from a specific country. Hence, country of origin serves as a cue upon which consumers rely in the absence of other information and experiences (Hong & Toner, 1989).

A significant body of empirical research has demonstrated country of origin effects on consumer product evaluations (Chattalas et al., 2008; Tse & Lee, 1993), perceptions of quality (Ahmed et al., 1994; Srinivasan et al., 2004), value (Chao, 2001; Sohail, 2005), prestige (Bhardwaj et al., 2010; Yasin et al., 2007), technical advancement (Chasin & Jaffe, 1979; Schweiger et al., 1997), and purchase likelihood (Akaah & Yaprak, 1993; Wang & Chen, 2004). Country of origin has been described as a halo construct that impacts overall consumer attitudes and behaviors (Han, 1989). Findings also indicate that the country of origin may override or assimilate into brand equity in influencing product judgments (Piron, 2000; Thakor & Kohli, 1996). However, research into country-of-origin effects has produced mixed results. Several studies found insignificant, unreliable, or weak country of origin impacts (Chowdhury & Ahmed, 2009; Liefeld, 1993; Ozsomer & Cavusgil, 1991). This suggests country of origin may not represent an infallible heuristic in consumer decision-making (Liefeld, 2004). Researchers have worked to uncover factors that moderate the effects of country of origin on consumer responses (Insch & McBride, 2004; Peterson & Jolibert, 1995; Usunier, 2006). Key variables include consumer affinity, animosity, ethnocentrism, and demographics (Klein et al., 1998; Shankarmahesh, 2006; Sharma, 2011; Shimp & Sharma, 1987), level of economic development associated with a country (Ahmed & d’Astous, 2008; Wang & Chen, 2004), product salience and involvement (Ahmed et al., 2004; Paswan & Sharma, 2004), prior knowledge and experience (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran, 2000; Maheswaran, 1994), and the competitiveness and market positioning of brands and product categories (Pechmann & Ratneshwar, 1992; Piron, 2000).

This indicates country of origin represents a complex, multifaceted cue in consumer decision-making that warrants ongoing investigation (Phau & Prendergast, 2000; Usunier, 2011). As globalization intensifies and international value chains become further dispersed across locations (Czinkota & Ronkainen, 1993; Josiassen et al., 2008), evolving conceptualizations and measurements of the country of origin incorporating brand origin, design location, component sourcing, and assembly origin have been called for (Hamzaoui & Merunka, 2006; Phau & Prendergast, 2000). Future research also needs to test the country of origin effects about emerging country perceptions (Josiassen & Harzing, 2008; Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009) as well as for intangible products and services (Javalgi et al., 2001). This will support more nuanced understandings of if and how country associations influence consumer responses across diverse contexts.

While the country of origin has been extensively studied over recent decades, the complex dynamics of globalization call for updated conceptualizations and continued investigation. As production processes disperse across borders and brands operate transnationally, traditional singular country affiliations give way to more complex origin blending. Furthermore, as emerging markets grow both as producer hubs and consumer markets, traditional country perceptions require re-examination. These shifts necessitate more nuanced approaches to capture country effects amid blended international value chains and changing reputational dimensions. Additional research is needed probing boundary conditions and moderators to country-of-origin outcomes across contexts. This literature review synthesizes established findings but also identifies pressing areas for additional research attention to guide international marketing strategy amid an environment of global flux and multiplicity regarding how “made in” designations shape consumer behavior.

As a response to this gap, this study aims to investigate the relevant literature to address the following research questions:

(1) How do evolving conceptualizations of country of origin that account for dispersed global production networks influence consumer perceptions compared to traditional singular country affiliations?

(2) How do country-of-origin effects vary across divergent product categories and consumption contexts based on differences in consumer involvement, knowledge, and decision motivations?

(3) How are country-of-origin effects moderated by emerging shifts in national reputations and changing consumer sentiments toward both developing and developed economies?

The remainder of the document is structured as follows:

Section 2 details the theoretical backgrounds of concepts about the topic.

Section 3 examines the research methodology and reviews the literature examined. In section 4, the results are explained.

Section 5 concludes the study by discussing theoretical and practical contributions.

2. Theoretical Background

Country of origin represents a salient extrinsic product cue that has been extensively studied regarding its influence on consumer perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Research on country-of-origin effects originated based on import-export dynamics but has expanded into a robust stream investigating how national affiliations shape consumer decision-making processes and international marketing strategy. This section reviews the extant literature on the country of origin and its resultant effects on consumer behavior and purchase decisions. In addition, past studies on the nuances of consumer perception and decision-making are in-depth examined.

2.1. Country of Origin Influence

2.1.1. Country of Origin Image and Reputation

A country's image and reputation related to its economic and industrial development represent a salient factor shaping the effects of the country of origin on consumer responses (Roth & Romeo, 1992; Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999). Specifically, the perceived level of economic and technological advancement associated with a country serves as a summary cue that colors perceptions about the types of products made in that country along dimensions like quality, prestige, innovativeness, and value (Ahmed & d’Astous, 2008; Dinnie, 2004). For instance, Germany enjoys strong country equity regarding perceptions of manufacturing prowess, precision engineering, and technical quality due to its longstanding industrial leadership, while Japan elicits imagery of technological sophistication and miniaturization skills (Askegaard & Ger, 1998; Pisharodi & Parameswaran, 1992).

On the other hand, developing countries tend to suffer from negative quality heuristics, as consumers doubt their ability to achieve advanced production capabilities and quality control systems (Wang & Chen, 2004). However, a country's image is multifaceted, as some developing economies like China or Mexico prompt mixed perceptions regarding cost-competitiveness versus subpar workmanship or process rigor (Ahmed & d’Astous, 1993; Li et al., 1997). Moreover, country images exhibit dynamism over time as national capabilities and reputations evolves (Anholt, 2005; Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009). For instance, South Korea transitioned from a country plagued by perceptions of counterfeit imitations to a powerhouse of innovation and high-tech manufacturing over a few decades (Chung et al., 2013).

2.1.2. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Animosity

Consumer ethnocentrism and animosity also critically impact country of origin effects, reflecting socio-psychological tendencies rather than cognitive evaluations of a country’s industrial capabilities (Klein, 2002; Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Ethnocentric consumers exhibit preferences for domestic goods rooted in beliefs about morality, appropriateness, and economic responsibility regarding local industries and jobs (Luque-Martinez et al., 2000; Saffu & Walker, 2005). Highly ethnocentric consumers judge foreign products more negatively and demonstrate an unwillingness to purchase them across categories (Watson & Wright, 2000).

Country animosity refers to sentiments of anger, resentment, or antipathy toward a specific country based on historical tensions, political/military conflicts or situations involving perceived economic harm (Klein et al., 1998; Riefler & Diamantopoulos, 2007). For instance, Chinese animosity toward Japan due to wartime atrocities persists decades later, coloring consumer attitudes and purchase behavior (Liu et al., 2020). Such animosity produces anger-based product discrimination even overriding rational quality or value assessments (Funk et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2010). While ethnocentrism represents more general in-group favoritism, country-based animosity prompts context-specific out-group negativity that profoundly shapes product reception and willingness to buy (Nes et al., 2012; Siamagka & Balabanis, 2015). These socio-psychological country-of-origin mechanisms operate distinctly from cognitive appraisals of a country's production capabilities or technological advancement (Maher & Mady, 2010).

2.1.3. Differences Across Product Categories

The effects of country of origin also differ fundamentally based on product category, as certain categories bear greater relevance for origin information while others remain less sensitive to such cues (Ahmed & d’Astous, 1993; Peterson & Jolibert, 1995). When product origin proves salient, the country-of-origin shapes consumer perceptions more consistently (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran, 2000; Hui & Zhou, 2003). Categories tied closely to national identities or reputations exhibit higher origin effects, like French perfumes and cosmetics, Swiss watches, German automobiles, or Japanese consumer electronics (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1999; Johansson, 1989). Additionally, categories perceived as more complex or technical show greater reliance on country stereotypes regarding requisite production skills (Ahmed et al., 2004; Maheswaran, 1994).

In contrast, low involvement categories like household staples elicit weaker effects as origin makes for a less diagnostic cue (Ahmed & d’Astous, 1996; Lim et al., 1994). Even so, some studies found country of origin shaped attitudes consistently across divergent products like televisions, cars, beer and jeans, arguing origin forms a salient cue regardless of category when other knowledge lacks (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 1989; Wang & Chen, 2004). This underscores country equity as summarizing information applied broadly when more specific attribute data proves unavailable (Han, 1989; Hong & Wyer, 1989). Still, countries accrue category-specific reputations, so determining which origin-category linkages provide highly diagnostic versus irrelevant combinations remains crucial (Josiassen et al., 2008; Roth & Romeo, 1992).

2.1.4. Country Interactions Across Value Chain

As production processes globalize, examining the country of origin requires differentiating multiple origin facets throughout the value chain encompassing design, components, assembly, and branding locations (Chao, 2001; Hamzaoui & Merunka, 2006; Insch & McBride, 2004). The country of design signals where the specifications, functionality priorities, and quality standards emerge. Component country of origin indicates material and subsystem sourcing areas tied to critical inputs. Country of assembly denotes the final manufacturing site most proximal to finished offerings. Finally, country of brand reflects corporate headquarters and marketing identity (Ahmed & d’Astous, 2008; Liu & Johnson, 2005).

These origin facets interact in complex combinations influence consumer evaluations. For instance, German design and Japanese electronics may combine favorably by integrating reputations for precision engineering and miniaturization. But South Korean branding paired with Chinese assembly could prompt discounting if conflicts with expectations for quality oversight. Research points to design origin weighing heavily in conferring overall product perceptions, with assembly origin and brand origin also meaningful (Chao, 2001; Hamzaoui, 2006). Component origin proves more meaningful for technical categories (Chao, 1998). Accounting for blending across countries throughout the value chain represents an evolving priority to encapsulate hybrid sourcing realities (Usunier, 2011).

2.2. Consumer Perceptions

2.2.1. Country of Origin Effects on Perceived Quality

Extensive research shows that the country of origin significantly impacts perceived product quality (Ahmed & d’Astous 2008; Peterson & Jolibert 1995; Pharr 2005). Specifically, country images and reputations regarding industrial capabilities, technological advancement, and quality control systems inform inferred judgments about the expected workmanship and performance of products emanating from a given nation (Bilkey & Nes 1982; Han 1989). Countries with reputations for precision manufacturing and engineering expertise like Germany and Japan therefore enjoy quality perception advantages for categories like automobiles and electronics (Chao & Rajendran 1993; Johansson et al. 1985). Conversely, developing countries suffer from negative quality stereotypes stemming from doubts about production infrastructure, skilled labor, and quality control mechanisms (Wang & Chen 2004). Still, the relationship between development status and quality perceptions is not entirely straightforward, as some studies found inferior impressions driven more by economic dominance perceptions than intrinsic manufacturing doubts regarding emerging economies (Cordell 1992). Across product types, country of origin consistently serves as a heuristic cue for inferring expected quality levels in the absence of specific attribute information (Hong & Wyer 1989).

2.2.2. Effects on Perceived Value

Beyond quality, country associations also feed into perceived value evaluations according to connections between development status, production costs, and appropriate pricing (Ahmed & d’Astous 1993; Sohail 2005). Specifically, countries with reputations for advanced engineering capabilities but high wage structures like Germany prompt value perceptions involving precision and performance outweighing price premiums. Meanwhile, developing economies like China elicit associations with labor cost savings passed through to affordable pricing, albeit with potential quality tradeoffs (Li et al. 2000). Indeed, brands charging high prices while producing in low-cost countries face consumer backlash, as this misaligns with expectations about appropriate cost structures (Chang 2008). Country of origin also impacts price sensitivity, as consumers prove less willing to pay premium prices for products made in developing versus developed economies, prompting discounts necessary to drive purchase interest (Ahmed et al. 2004).

2.2.3. Influences on Perceived Prestige

The reputational cachet associated with a country additionally confers prestige perceptions based on the status and exclusivity ascribed to owning products crafted in eminent manufacturing nations (Bhardwaj et al. 2010; Yasin et al. 2007). Luxury categories show particular prestige sensitivities to country of origin given the pivotal role of exclusivity claims in premium branding alongside overall performance and quality cues (Kapferer 1997). For instance, France and Italy enjoy inherent advantages for categories like fashion, wines, perfumes, and luxury automobiles, as strong cultural identities link to prestige notions of craftsmanship, heritage, and refinement (Couret 2013; Davvetas et al. 2015). Meanwhile, emerging markets face challenges in cultivating prestige associations despite brisk sales growth, indicating country of origin spillovers requiring sustained reputation building (Jenss 2016). As country images exhibit dynamism, the growth of luxury demand from markets like China and India coupled with investments in local manufacturing could progressively transform prestige perceptions for these national brands (Jiang & Wei 2014).

2.2.4. Shaping Perceptions of Technical Prowess

Country of origin also holds particular relevance regarding consumer judgments about the technical advancement and innovative capabilities associated with high-technology products (Chasin & Jaffe 1979; Schweiger et al. 1997). Specifically, countries accruing reputations as hubs of electronics innovations and sophisticated IT infrastructure like Japan, South Korea, and the United States inspire beliefs that cutting-edge research and advanced production skills infuse greater technological potency or user-friendly features into category offerings (Lee & Ganesh 1999). Meanwhile, developing countries attempting to expand technology manufacturing elicit skepticism regarding underlying process mastery or design originality necessary to achieve true innovation (Kinra 2006). However, in reality brands headquartered in developed markets often manage the R&D and core intellectual property guiding technology development regardless of manufacturing origin (Kumar & Steenkamp 2013). Still, country associations exert a heuristic role in shaping inferences about the competency in and command over complex technological capabilities (Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006).

2.2.5. Country of Origin as a Halo Construct

The wide-ranging impacts of country of origin on consumer perceptions across dimensions like quality, value, and technical advancement underline its nature as a halo construct those colors overall product impressions and attitudes (Han 1989; Nebenzahl & Jaffe 1996). When lacking familiarity or specific details about a given offering, country imagery fills this void to broadly summarize expected performance as a way to simplify evaluations and decisions (Hong & Wyer 1989). In effect, “made in” serves as an intrinsic cue that generates a heuristic impression subsequently guiding and potentially biasing product information processing (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran 2000; Hong & Kang 2006). While halo effects manifest uniformly, country of origin can also elicit hybrid responses involving haloed strengths in some areas but weaknesses in others based on multi-dimensional stereotypes (Han 1989). For instance, China may activate contradictions between affordability halo with quality doubts. As country images grow more complex amid global production systems, disentangling dimensions represent an increasing priority (Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006).

2.2.6. Emotional and Identity Appeals

Beyond informing cognitive performance evaluations, country of origin also taps emotively into consumer pride, affinity, animosity, and ethnocentric tendencies (Klein 2002; Verlegh 2007). Products from positively distinctive domestic or culturally affiliated countries allow consumers to signal identity and status through emotionally resonant purchases (Batra et al. 2000). Global brands leverage country equity via appeals targeting national pride across markets, although rhetoric linking brand and country success risks backlash (Kipnis et al. 2012). Negative country attitudes also motivate animosity-based avoidance of purchasing imports (Klein et al. 1998). Overall, countries function not just as cognitive informational cues but also as symbolic cultural assets carried by brands and consumed conspicuously or discreetly as identity markers (Askegaard 2006).

2.3. Purchase Decision

2.3.1. Effects on Product Evaluation and Consideration

A predominant finding within the country-of-origin literature points to significant effects on early stages of the consumer decision process encompassing product evaluations and consideration set formation prior to ultimate purchase choices (Ahmed & d’Astous 2008; Pharr 2005). Specifically, country of origin consistently informs the quality, value and acceptability inferences which shape assessments regarding which alternatives prove viable options meriting further inspection or eligibility for potential selection (Hong & Toner 1989; Johansson et al. 1985). These evaluative effects subsequently influence consideration sets as the pool of products deemed satisfactory and thus retention for purchase deliberations (Howard & Sheth 1969; Nielsen et al. 2010). In effect, country cues facilitate screening out or discounting unacceptable or unsatisfactory options from the choice set compared to more positively viewed offerings (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran 2000; Papadopoulos & Heslop 2014). Both direct cross-country product comparisons as well as within-country brand assessments showcase country-of-origin impacts whereby lower development status or competitive disadvantage prompts product dismissal or lesser receptivity (Hester & Yuen 1987; Wang & Lamb 1983). Hence, the country of origin broadly restricts the initial funnel of products that consumers contemplate and retain for potential purchasing (Lee & Ganesh 1999).

2.3.2. Mixed Effects on Purchase

However, findings diverge regarding whether the country ultimately sways actual purchase selections from consideration sets after intervening factors enter decisions (Insch & McBride 1998; Peterson & Jolibert 1995). Specifically, aspects like brand familiarity, reputation, and loyalty along with pricing, promotions, or store displays can disrupt downstream selection such that initial country of origin biases weaken or holdings nullify amid these competing influences (Hong & Toner 1989; Johansson 1989). Particularly for high-involvement decisions, motivated reasoning may justify preferred brand choices despite conflicting origin associations (Maheswaran 1994; Obermiller & Spangenberg 1989). Still, some studies reveal country directly impacts selective behavior including willingness to pay or actual choices made (Akaah & Yaprak 1993; Balabanis & Diamantopoulos 2008). Purchasing also shows ethnocentric avoidance patterns as highly ethnocentric consumers consistently shun foreign products (Siamagka & Balabanis 2015; Shimp & Sharma 1987). For still-developing brands, the country sticks to choices more tightly given limited familiarity or attachment to counteract cues (Herz & Diamantopoulos 2013). So country can sway selection although further aspects may loosen initial evaluative biases when additional knowledge enters decisions.

2.3.3. Moderating Role of Consumer Knowledge

A key moderator shaping the extent of country-of-origin effects involves pre-existing consumer knowledge, as those lacking familiarity or experience with products show greater reliance on accessible country heuristics when making appraisals (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran 2000; Heslop et al. 2004; Maheswaran 1994). Knowledge also strengthens the motivational capacity to counter-argue or downplay statistically processed origin information, thus reducing potential biases (Sanbonmatsu et al. 1997). Additionally, familiar brands exhibit diluted country effects given overriding awareness, sentiments, and credibility accrued through past exposure and usage (Leclerc et al. 1994; Thakor & Kohli 1996). Experts also differentiate multiple countries within competitive sets more accurately versus novices guided dominantly by broad origin distinctions (Schaefer 1997). High-knowledge consumers even utilize multiple differentiating origin facets like design, manufacturing, and brand hubs when available versus aggregate impressions (Insch & McBride 2004; Liu & Johnson 2005). Hence, diminishing knowledge exacerbates while accumulating first-hand or societal expertise attenuates country effects on product considerations.

2.3.4. Moderating Effects of Consumer Involvement

Consumer involvement represents another key moderator given its informational processing implications (Ahmed et al. 2004; Lin & Chen 2006). Highly involved categories with significant personal relevance or financial/performance risk show greater selective consideration of all accessible decision criteria including origin (Maheswaran 1994; Wang et al. 2012). This manifests in more extensive attribute weighting, critical evaluations, and bias correction appraisals (Maheswaran & Stemthal 1990). In contrast, lower involvement purchases exhibit reliance on basic heuristics like country of origin without deeper processing to generate considerations or guide choices (Lee & Lou 1995). However, increased elaboration can also rationalize preferred options that overcome origin inconsistencies, or emphasize dual strengths across brand and country (Johansson et al. 1985). But durable expensive goods with self-expressive elements exhibit greater sheer avoidance of disfavored foreign origins than low-cost disposable goods allowing flexible considerations when involvement elevates (Kinra 2006). So directional effects remain context-specific.

2.3.5. Moderating Role of Consumer Demographics

Variations also emerge across consumer segments like cultural clusters, identities, and demographics in sensitivity to the country in purchase consideration (Balabanis & Diamantopoulos 2008; Watson & Wright 2000). Younger or aspirational consumers in emerging markets show acceptance of imported Western brands for status gains, while older individuals exhibit preferences or ethnocentric loyalty toward local products (Batra et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2012). Developed market majorities demonstrate less extreme reactions as cosmopolitanism dilutes origin effects, but aging consumers retain distinct ethnocentric tendencies and preferences (Brodowsky 1998; Smyczek & Glowik 2011). In terms of gender, men appear less ethnocentric and more welcoming of imports than women (Good & Huddleston 1995; Wang & Chen 2004). Additionally, collectivistic versus individualistic as well as uncertainty-avoidant cultures reflect differences in reliance upon country cues when evaluating risks of foreign products (Alden et al. 2013; Podoshen et al. 2011). Overall, societal context and consumer identities moderate just how a diagnostic country functions across consideration of and selections between choice options.

3. Study Methodology

A systematic literature review allows for the integration of multiple works on the same topic, summarizing common elements and contrasting differences (Durach et al., 2021; Sauer & Seuring, 2023; Snyder, 2019). It also facilitates the synthesis of existing knowledge to offer valuable insights by identifying trends, themes, and topics in the literature (Gough et al., 2012). Given these strengths and their alignment with the study's objectives, a systematic review was conducted to summarize existing research on the influence of COO on consumer perception and purchase decisions. The review process followed some key steps which included defining research questions, selecting databases, choosing search terms, applying quality screening, conducting the review, and synthesizing and presenting the results. In the first step, research questions were formulated as described above (Katrak et al., 2004; Kraus & Dasí-rodríguez, 2020). The second step involved compiling databases containing relevant scientific studies, with a focus on selecting journals from the marketing academic domain to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the research (Sauer & Seuring, 2023). Additionally, the selected journal database was required to consist of marketing and business journals, and articles were chosen specifically from journals focusing on marketing or customer relationships to align with the scope of the review study.

3.1. Search Protocol and Data Collection

The third stage of the review involved selecting search terms to refine the articles. Two sets of keywords were chosen to ensure relevance to the study. The first set focused on investigating the influence of COO and included terms such as "country of origin" and "country of manufacture." The second set aimed to keep the search focused on consumer perception and purchase decisions, with keywords such as "consumer perception," "consumer behavior," and "purchase decisions." This ensured that the review stayed within the scope of consumer purchase decision-making. A search in SCOPUS was conducted to gather various literature for the studies. The search resulted in 250 articles, which underwent practical screening to determine relevance. While the study did not impose limits on dates, industries, countries, or methodologies, 107 articles were excluded based on paper type. The fifth stage, which involves screening for scientific quality, was unnecessary as the database selection process already ensured quality. After careful reading of text, 67 articles were finally included in the study for analysis.

3.2. Summary Statistics of Studies

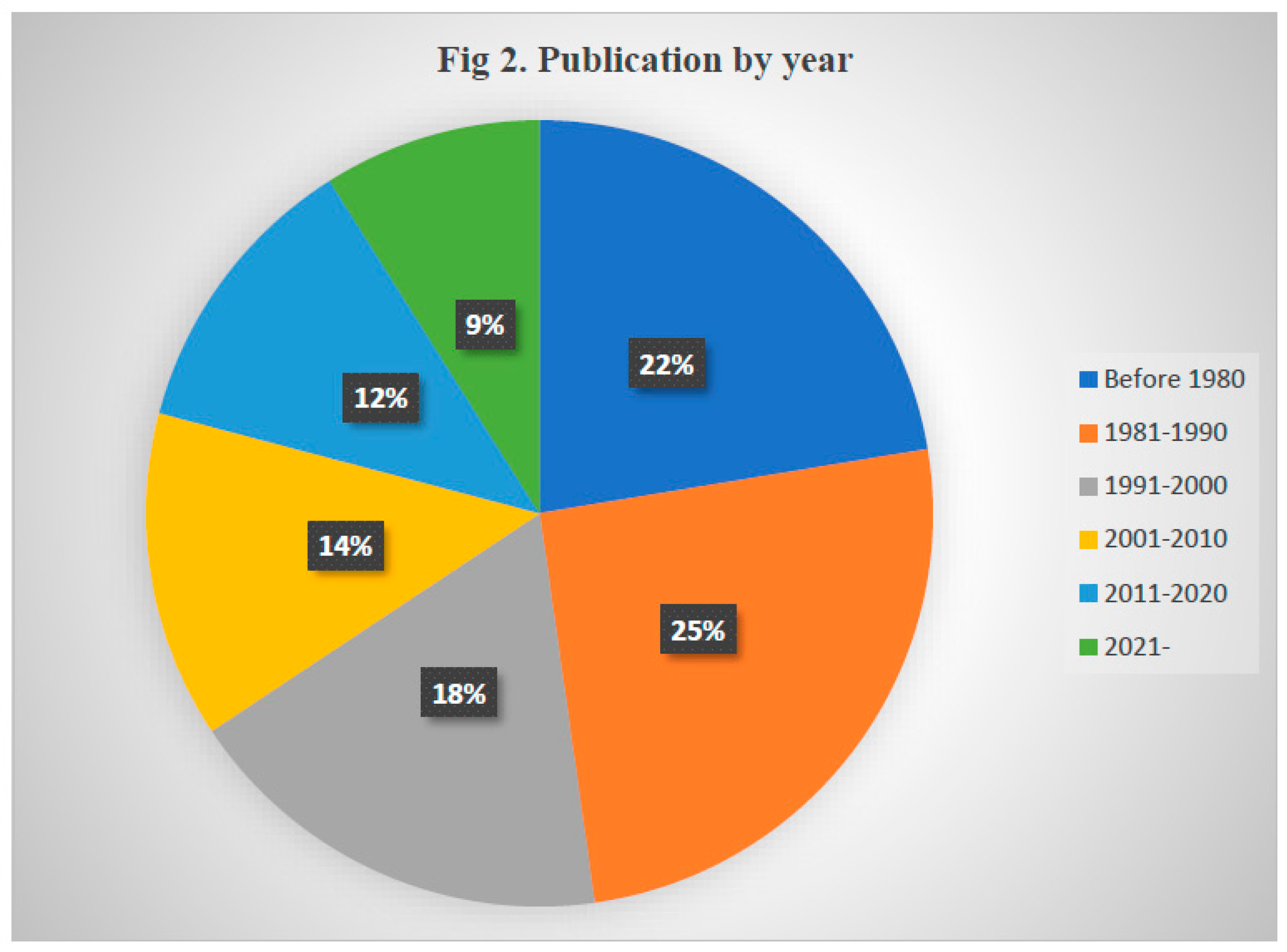

This section details the literature's statistical details, including publication frequency, and article distribution across journals, offering both a quantitative overview and insight into methodological trends and academic distribution over time.

The 67 articles reviewed were published across a diverse set of 15 journals as shown in

Figure 1, demonstrating the broad relevance of country-of-origin research. The journal with the most publications was the International Marketing Review with 14 articles, followed by the Journal of International Consumer Marketing with 5 articles. The Journal of International Business Studies and the Journal of World Business also had multiple relevant articles with 6 and 5 respectively. High impact journals like the Journal of Consumer Research, the Journal of Marketing, and the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science contributed 3 articles each.

Other journals providing insights included the Journal of Advertising, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Service Marketing, and European Management Review. The sample also featured consumer behavior focused journals such as the International Journal of Consumer Studies and the Journal of Consumer Marketing. Overall, leading journals across marketing, international business, and consumer research contributed to the knowledge basis, highlighting country-of-origin as a cross-disciplinary topic generating diverse scholarly inquiry.

Analysis of publication dates reveals that country-of-origin research originated and saw significant attention between the 1980s and 1990s. As seen in

Figure 2, 15 of the reviewed articles were published before 1980, reflecting the foundational early work on the topic. Between 1981 to 1990, 17 articles came out as the field gained momentum. The period from 1991 to 2000 featured 12 publications, showing continuation of steady research activity. Between 2001 to 2010, 9 relevant articles were published. More recently from 2011 to 2020, 8 articles provided additional insights on the evolving nature of country effects. And since 2021, 6 articles demonstrate country-of-origin remains an active research stream. While the volume of publications has gradually declined from the peak decades ago, contemporary articles update understanding of country effects amid changing global realities. The distribution reflects enduring scholarship combined with calls to re-examine foundational conceptualizations.

4. Results

In relation to the RQ (1), traditional conceptualizations of country of origin emphasize a singular national affiliation, with effects based on an aggregate “made in” association (Bilkey & Nes 1982; Nagashima 1970; Roth & Romeo 1992). However, the dispersed reality of global production systems requires differentiating multiple potential origin facets encompassing design, parts sourcing, assembly, and branding locations (Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006; Phau & Prendergast 2000; Usunier 2011). Research incorporating such distinctions reveals complex blending effects. Regarding product design origin, multiple studies found it exerts a predominant influence on overall quality and performance perceptions compared to other origin elements (Chao 2001; Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006; Liu & Johnson 2005). Design Represents the critical front-end phase shaping engineering specifications, aesthetics, functionality priorities, and quality standards (Leclerc et al. 1994; Thakor & Kohli 1996). Therefore, country associations linked to precision design capabilities like Germany positively shape inferences (Herz & Diamantopoulos 2013; Insch & McBride 2004).

However, brands from countries lacking engineering reputations can dilute negative perceptions by offshoring design activities to more favorably viewed nations (Chao 1993; Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006). Still, design origin maintains significance, as German car models designed domestically elicit higher quality perceptions than those outsourced (Johansson et al. 1985; Leclerc et al. 1994). Overall, design country prominently colors product impressions. Component part origin also impacts perceptions, with influences varying by product category based on the diagnosticity of inputs (Ahmed & d’Astous 1996; Chao 2001). Electronic or mechanical products show stronger quality attributions based on component sourcing locales due to greater perceived importance of subsystem performance and precision (Chao 1993; Insch & McBride 2004). Countries renowned for production essentials relevant to given categories thereby boost perceptions when supplying key parts like German steel or Japanese semiconductors (Chao 2001; Tse & Lee 1993). Assembly origin exerts effects, but generally weaker than design or component hubs (Chao 1993; Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006). Localizing assembly domestically within target markets improves perceptions by signaling quality oversight and tailoring (Chao 2001). But offshore assembly prompts discounts when countries lack manufacturing reputations, although design and branding can partially override (Leclerc et al. 1994; Liu & Johnson 2005).

Brand origin associations also emerge based on corporate headquarters, history and identity claims (Andehn et al. 2014; Thakor & Kohli 1996). Brands from innovator nations enjoy halo effects, while developing economy brands struggle from inconsistent imagery unless acquiring foreign firms (Piron 2000; Ulgado & Lee 1993). Acquisition pathways enable “born global” brands to tap positive equity through brand acquisition rather than endogenous cultivation (Gammoh et al. 2014). Overall, while singular origin cues dominate marketing, multiple facets interact in forming impressions. Strong design and brand origins offset weaker assembly locales (Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006), and synergies between reputed component sources and assembly nations boost perceptions (Chao 2001). Disentangling country roles represents an imperative amid complex global supply chains.

In relation to the RQ (2), Research reveals product category as a pivotal moderator of country-of-origin effects, as certain categories show greater salience and diagnosticity for origin information (Ahmed & d'Astous 1993; Peterson & Jolibert 1995). Categories closely tied to national identities and reputations exhibit the strongest country-of-origin influences including French perfumes and wines, Swiss watches, German cars, and Japanese electronics (Agrawal & Kamakura 1999; Jaffe & Nebenzahl 2006). Consumers view origin as more relevant for categories intrinsically linked to perceived national capabilities and strengths (Verlegh & Steenkamp 1999). Additionally, products viewed as more complex or technical elicit greater reliance on country stereotypes regarding requisite expertise for development and manufacture (Ahmed et al. 2004; Maheswaran 1994). Origin functions as a proxy cue for inferring technological advancement or innovative design capabilities when ability to directly scrutinize functional attributes proves limited (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran 2000; Lee & Ganesh 1999). However, low involvement categories like consumer-packaged goods show attenuated effects, as origin makes for a less diagnostic intrinsic cue (Ahmed & d’Astous 1996; Lim et al. 1994).

Beyond product differences, consumer knowledge also moderates country-of-origin effects. Specifically, those lacking familiarity or direct experience with products tend to rely more on accessible country imagery when evaluating options (Maheswaran 1994; Schaefer 1997). Knowledge provides alternate bases for judgment and strengthens ability to discount or counter-argue country heuristics through motivated reasoning (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran 2000; Maheswaran & Sternthal 1990). Additionally, strong brands dilute country effects by overriding origin with established familiarity and equity (Leclerc et al. 1994; Thakor & Kohli 1996). Consumer involvement represents an additional key moderator, as highly involving purchases show more extensive processing of all available decision cues including country (Ahmed et al. 2004; Lin & Chen 2006). However, increased elaboration can either increase weighting on origin inconsistencies or enable rationalizing preferred options despite contrasting country associations (Johansson et al. 1985; Maheswaran & Sternthal 1990). Highly ethnocentric segments also consistently avoid foreign origins across low or high involvement categories (Klein 2002; Siamagka & Balabanis, 2015). In terms of consumption situation, purchases for public or conspicuous consumption exhibit greater sensitivity to country-of-origin effects given the prestige or status signaling value of origin in front of relevant others (Ahmed et al. 2004; Balabanis & Diamantopoulos 2008). Self-expressive possessions more tightly integrate country equity into identity displays (Batra et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2012). However, private practical consumption diminishes origin influence. Overall country effects hinge on category diagnosticy, consumer knowledge, and purchase motivations.

In answering the RQ (3), most studies reveals country reputations and images exhibit dynamism over time as economic and industrial capabilities evolve (Anholt 2005; Roth & Diamantopoulos 2009). As previously developing economies like South Korea, China, India, and Mexico emerge as manufacturing powerhouses, traditional negative perceptions require re-evaluation (Josiassen & Harzing 2008; Kinra 2006). Consumers increasingly recognize capabilities for advanced production and quality control systems, weakening blanket discounts (Ahmed et al. 2004; Dinnie 2004). However, progress remains uneven, as developing nations continue fighting ingrained negativity biases (Li et al. 1997). Beyond dynamic reputations, consumer sentiments also shift toward countries over time. For instance, animosity toward Japan stemming from wartime atrocities gradually dissipated across generations (Riefler & Diamantopoulos 2007). And pockets of anti-Americanism or resentment toward Western dominance diminished alongside growing embrace of brands evoking cosmopolitan global citizenship (Strizhakova et al. 2012). However, resurgent economic nationalism and populist backlash currently foster re-emerging animosity against globalization’s winners (Burton 2020; Johnson 2018).

Within developing markets, research finds younger consumers more welcoming of imported brands from developed nations for status gains, although older individuals retain stronger preferences for local products (Batra et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2012). Additionally, identity-congruent countries enjoy favoritism, as diasporic immigrants maintain affinity toward their home countries’ offerings (Josiassen 2011). Overall, shifts in both objective country reputations and subjective consumer sentiments continually reshape country-of-origin effects. Studies also reveal halo effects from positive country associations transfer across multiple categories, while negative reputations extend beyond directly relevant industries (Han 1989; Pisharodi & Parameswaran 1992). Countries accrue equity and image profiles spanning broader emotional connections beyond specific product-country linkages (Askegaard & Ger 1998; Roth & Diamantopoulos 2009). Therefore, evolving sentiments fundamentally update heuristics. However, research also cautions that global brands and transnational value chains complicate traditional country-of-origin conceptualizations (Leclerc et al. 1994; Usunier 2011). As production disperses across borders, brands effectively deterritorialize beyond singular national identities (Thakor & Kohli 1996). This enables strategic mitigation of unfavorable country effects amid blended sourcing locales (Hamzaoui & Merunka 2006). Overall, country equity remains central in consumer psychology, but exhibits ongoing evolution. Marketing increasingly emphasizes multinational identities and diverse cultural representations transcending monolithic images (Wang et al. 2012). While country of origin maintains relevance, absolute generalizations risk becoming outdated amid shifts in reputation and sentiment alongside global interconnectedness.

5. Conclusions

This literature review synthesizes current knowledge on the influence of country of origin on consumer perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. The expansive body of research analyzed underscores country of origin as a salient cue shaping product evaluations, brand equity, and purchase decisions through both cognitive and emotional mechanisms. However, findings also reveal complexity and context-dependency in country effects based on product categories, consumer characteristics, and shifting global landscapes. Additional research is needed to further probe the evolving dynamics of origin influences amid transnational brands, dispersed production networks, and growing emerging markets. More nuanced conceptualizations and updated empirical testing can advance international marketing strategy in an increasingly interconnected world.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This literature review holds several key theoretical implications. Firstly, it reaffirms the overall validity of the country-of-origin concept as a meaningful driver of consumer behavior and marketing strategy. However, traditional conceptualizations of singular national affiliations require augmentation to account for increasingly complex origin blending across transnational value chains. Theoretical frameworks need to incorporate multiple facets like design, manufacturing, and branding origin and their interactions. This challenges conventional singular "made in" perspectives.

Secondly, the dynamics of consumer psychology show country effects are not static or absolute. Country equity exhibits ongoing evolution as national reputations shift over time alongside economic and industrial development. Consumer sentiments also change as animosities dissipate and new markets emerge. This underscores the need for contingent, context-specific theorization.

Thirdly, variations in country-of-origin outcomes across products and consumers highlight the context-dependency at the heart of categorization theory foundations. Country effects prove more salient for some categories than others based on diagnostic principles. Individual factors like knowledge, involvement, and identities also moderate effects. Incorporating contingency factors can strengthen theorization.

Finally, while country of origin remains relevant, globalization requires balancing parsimony with sufficient sophistication in models. The dispersed and blended reality of production today challenges conventional assumptions. Yet countries still provide meaningful cues. Effectively reconciling these tensions has theoretical importance for properly specifying country-related constructs. Overall, this review highlights promising directions for enriching country of origin perspectives attuned to contemporary landscapes.

5.2. Managerial Implication

This review holds several important implications for international marketing managers. Firstly, country equity remains a vital asset. Firms must understand their origin advantages and limitations based on category stereotypes and reputational dimensions. Capitalizing on positive country images while mitigating weaker associations is imperative. Secondly, managers must track evolutions in country perceptions. As developing economy reputations improve and animosities fade, proactive reputation management is essential. Marketing should monitor international sentiment, address animosity roots, and communicate progress.

Thirdly, managers must leverage country synergies across brands through coordination. Halo effects mean overall country equity transfers across products and categories. Managing integrated country campaigns and assets can maximize positive spillover. Fourthly, marketers need cognizance of category and consumer moderators to country effects. Standardized global strategies may falter given variations in diagnostic and receptiveness across cultures and demographics. Tailoring based on category and target market relevance is crucial. Fifthly, managers should embrace country of origin multiplicity in branding and positioning. As production disperses, rigid “made in” labels lose relevance. Flexibly communicating multifaceted sourcing narratives allows mitigating disadvantageous associations.

Finally, marketers must balance standardization and localization in light of context-specific country effects. Adaptation to particular product-country matchups and consumer biases may be prudent even amid broader globalization. There are no blanket universal rules regarding country leveraging. Discerning areas for consolidation versus customization is key.

Overall, proactive country of origin management requires marketers move beyond assumptions and simplistic associations to capture the nuanced, contingent realities of country equity in the contemporary world.

References

- Agrawal, J., & Kamakura, W. A. (1999). Country of origin: A competitive advantage?. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 16(4), 255-267. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. A., & d'Astous, A. (2008). Antecedents, moderators and dimensions of country-of-origin evaluations. International Marketing Review, 25(1), 75-106. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. A., & d'Astous, A. (1993). Cross-national evaluation of made-in concept using multiple cues. European Journal of Marketing, 27(7), 39-52. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z. U., Johnson, J. P., Yang, X., Fatt, C. K., Teng, H. S., & Boon, L. C. (2004). Does country of origin matter for low-involvement products? International Marketing Review, 21(1), 102-120. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. A., & d’Astous, A. (1996). Country-of-origin and brand effects: A multi-dimensional and multi-attribute study. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 9(2), 93-115. [CrossRef]

- Akaah, I. P., & Yaprak, A. (1993). Assessing the influence of country of origin on product evaluations: An application of conjoint methodology. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 5(2), 39-53. [CrossRef]

- Andehn, M., Nordin, F., & Nilsson, M. E. (2014). Facets of country image and brand equity: Revisiting the role of product categories in country-of-origin effect research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 13(3), 225-238. [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. (2005). Some important distinctions in place branding. Place Branding, 1(2), 116-121. [CrossRef]

- Askegaard, S., & Ger, G. (1998). Product-country images: Towards a contextualized approach. European Advances in Consumer Research, 3, 50-58.

- Balabanis, G., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2008). Brand origin identification by consumers: A classification perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 16(1), 39-71. [CrossRef]

- Batra, R., Ramaswamy, V., Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Ramachander, S. (2000). Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(2), 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, V., Kumar, A., & Kim, Y. K. (2010). Brand analyses of U.S. global and local brands in India: The case of Levi’s. Journal of Global Marketing, 23(1), 80-94. [CrossRef]

- Bilkey, W. J., & Nes, E. (1982). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. Journal of International Business Studies, 13(1), 89-99. [CrossRef]

- Burton, N. (2020). Nationalism and protectionism after the crisis. Journal of European Integration, 42(4), 485-501. [CrossRef]

- Chao, P. (1998). Impact of country-of-origin dimensions on product quality and design quality perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 42(1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Chao, P. (1993). Partitioning country of origin effects: Consumer evaluations of a hybrid product. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(2), 291-306. [CrossRef]

- Chao, P. (2001). The moderating effects of country of assembly, country of parts, and country of design on hybrid product evaluations. Journal of Advertising, 30(4), 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Chasin, J., & Jaffe, E. D. (1979). Industrial buyer attitudes towards goods made in Eastern Europe. Columbia Journal of World Business, 14(2), 74-81.

- Chattalas, M., Kramer, T., & Takada, H. (2008). The impact of national stereotypes on the country of origin effect: A conceptual framework. International Marketing Review, 25(1), 54-74. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, H. K., & Ahmed, J. U. (2009). An examination of the effects of partitioned country of origin on consumer product quality perceptions. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(4), 496-502. [CrossRef]

- Chung, J. E., Pysarchik, D. T., & Hwang, S. J. (2009). Effects of country-of-origin cues on consumer perceptions of quality and value for generic and high-end apparel brands. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(2), 143-154. [CrossRef]

- Czinkota, M. R., & Ronkainen, I. A. (1993). International marketing (3rd ed.). The Dryden Press.

- Dinnie, K. (2004). Country-of-origin 1965-2004: A literature review. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 3(2), 49-166. [CrossRef]

- Durach, C. F., Kembro, J. H., & Wieland, A. (2021). How to advance theory through literature reviews in logistics and supply chain management. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 51(10), 1090–1107. [CrossRef]

- Funk, C. A., Arthurs, J. D., Treviño, L. J., & Joireman, J. (2010). Consumer animosity in the global value chain: The effect of international production shifts on willingness to purchase hybrid products. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5), 639-651. [CrossRef]

- Gammoh, B. S., Koh, A. C., & Okoroafo, S. C. (2014). Consumer culture brand positioning strategies: An experimental investigation. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(1), 62-74. [CrossRef]

- Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs\rand methods art:10.1186/2046-4053-1-28. Systematic Reviews, 1–9.

- Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Maheswaran, D. (2000). Determinants of country-of-origin evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 96-108. [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, L., & Merunka, D. (2006). The impact of country of design and country of manufacture on consumer perceptions of bi-national products' quality: an empirical model based on the concept of fit. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(3), 145-155. [CrossRef]

- Han, C. M. (1989). Country image: Halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 222-229. [CrossRef]

- Herz, M. F., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2013). Activation of country stereotypes: Automaticity, consonance, and impact. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(4), 400-417. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. T., & Kang, D. K. (2006). Country-of-origin influences on product evaluations: The impact of animosity and perceptions of industriousness brutality on judgments of typical and atypical products. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19(2), 7-41. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. T., & Toner, J. F. (1989). Are there gender differences in the use of country-of-origin information in the evaluation of products?. In T. K. Srull (Ed.), NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 16 (pp. 468-472). Association for Consumer Research. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. A., Phau, I., & Lin, C. (2010). Consumer animosity, economic hardship, and normative influence: How do they affect consumers’ purchase intention?. European Journal of Marketing, 44(7/8), 909-937. [CrossRef]

- Hui, M. K., & Zhou, L. (2003). Country-of-manufacture effects for known brands. European Journal of Marketing, 37(1/2), 133-153. [CrossRef]

- Insch, G. S., & McBride, J. B. (2004). The impact of country-of-origin cues on consumer perceptions of product quality: A binational test of the decomposed country-of-origin construct. Journal of Business Research, 57(3), 256-265. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, E. D., & Nebenzahl, I. D. (2006). National image and competitive advantage. Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Javalgi, R. G., Cutler, B. D., & Winans, W. A. (2001). At your service! Does country of origin research apply to services?. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(7), 565-582. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J. K. (1989). Determinants and effects of the use of ‘made in’ labels. International Marketing Review, 6(1), 47-58. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J. K., Douglas, S. P., & Nonaka, I. (1985). Assessing the impact of country of origin on product evaluations: A new methodological perspective. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(4), 388-396. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. (2018). The US-China trade war: A review of the economic impact and geopolitical implications. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 10(2), 96-104. [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Assaf, G. A., Karpen, I. O., & Farrelly, F. J. (2008). Consumer ethnocentrism and willingness to buy: Analyzing the role of three demographic consumer characteristics. International Marketing Review, 25(4), 327–346. [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., & Harzing, A. W. (2008). Descending from the ivory tower: Reflections on the relevance and future of country-of-origin research. European Management Review, 5(4), 264-270. [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Assaf, A. G., Karpen, I. O., & Farrelly, F. J. (2011). Consumer ethnocentrism and willingness to buy: Analyzing the role of three demographic consumer characteristics. International Marketing Review, 28(6), 627-646. [CrossRef]

- Katrak, P., Bialocerkowski, A. E., Massy-Westropp, N., Kumar, V. S. S., & Grimmer, K. A. (2004). A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 4, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kinra, N. (2006). The effect of country-of-origin on foreign brand names in the Indian market. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24(1), 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R., & Morris, M. D. (1998). The animosity model of foreign product purchase: An empirical test in the People's Republic of China. Journal of Marketing, 62(1), 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Klein, J. G. (2002). Us versus them, or us versus everyone? Delineating consumer aversion to foreign goods. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2), 345-363. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S., & Dasí-rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research Content courtesy of Springer Nature , terms of use apply . Rights reserved . Content courtesy of Springer Nature , terms of use apply . Rights reserved . International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16, 1023–1042.

- Lee, W. N., & Ganesh, G. (1999). Effects of partitioned country image in the context of brand image and familiarity: A categorization theory perspective. International Marketing Review, 16(1), 18-41. [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, F., Schmitt, B. H., & Dube, L. (1994). Foreign branding and its effects on product perceptions and attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2), 263-270. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. G., Fu, S., & Murray, W. L. (1997). Country and product images: The perceptions of consumers in the People's Republic of China. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 10(1-2), 115-138. [CrossRef]

- Liefeld, J. P. (1993). Experiments on country-of-origin effects: Review and meta-analysis of effect size. In N. Papadopoulos & L.A. Heslop (Eds.), Product-country images: Impact and role in international marketing (pp. 117-156). International Business Press.

- Liefeld, J. P. (2004). Consumer knowledge and use of country-of-origin information at the point of purchase. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 4(2), 85-87. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K., Darley, W. K., & Summers, J. O. (1994). An assessment of country of origin effects under alternative presentation formats. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(3), 274-282. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. R., Liu, B. S., Lin, W. B., & Wang, X. Z. (2020). Home country bias in consumer ethnocentrism and animosity: An integrative review and a conceptual framework. International Marketing Review, 38(1), 238-265. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. S., & Johnson, K. F. (2005). The automatic country-of-origin effects on brand judgments. Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 87-97. [CrossRef]

- Luque-Martinez, T., Ibanez-Zapata, J. A., & Del Barrio-Garcia, S. (2000). Consumer ethnocentrism measurement–An assessment of the reliability and validity of the CETSCALE in Spain. European Journal of Marketing, 34(11/12), 1353-1374. [CrossRef]

- Maher, A. A., & Mady, S. (2010). Animosity, subjective norms, and anticipated emotions during an international crisis. International Marketing Review, 27(6), 630-651. [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D. (1994). Country of origin as a stereotype: Effects of consumer expertise and attribute strength on product evaluations. Journal of consumer research, 21(2), 354-365. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, A. (1970). A comparison of Japanese and US attitudes toward foreign products. The Journal of Marketing, 34(1), 68-74. [CrossRef]

- Nes, E. B., Yelkur, R., & Silkoset, R. (2012). Exploring the animosity domain and the role of affect in a cross-national context. International Business Review, 21(5), 751-765. [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. (1989). Exploring the effects of country-of-origin labels: an information processing framework. ACR North American Advances.

- Ozsomer, A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (1991). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations: A sequel to Bilkey and Nes review. Enhancing Knowledge Development in Marketing, 2, 269-277.

- Paswan, A. K., & Sharma, D. (2004). Brand-country of origin (COO) knowledge and COO image: Investigation in an emerging franchise market. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 13(3), 144-155. [CrossRef]

- Pechmann, C., & Ratneshwar, S. (1992). Consumer covariation judgments: Theory or data driven?. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 373-386. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. A., & Jolibert, A. J. (1995). A meta-analysis of country-of-origin effects. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(4), 883-900. [CrossRef]

- Pharr, J. M. (2005). Synthesizing country-of-origin research from the last decade: Is the concept still salient in an era of global brands?. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(4), 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Phau, I., & Prendergast, G. (2000). Conceptualizing the country of origin of brand. Journal of Marketing Communications, 6(3), 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Piron, F. (2000). Consumers’ perceptions of the country-of-origin effect on purchasing intentions of (in) conspicuous products. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(4), 308-321. [CrossRef]

- Pisharodi, M., & Parameswaran, R. (1992). Assimilation effects in country image research. Developments in Marketing Science, 15, 249-253.

- Riefler, P., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2007). Consumer animosity: A literature review and a reconsideration of its measurement. International Marketing Review, 24(1), 87-119. [CrossRef]

- Roth, K. P., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Advancing the country image construct. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 726-740. [CrossRef]

- Roth, M. S., & Romeo, J. B. (1992). Matching product category and country image perceptions: A framework for managing country-of-origin effects. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(3), 477-497. [CrossRef]

- Saffu, K., & Walker, J. H. (2005). An assessment of the consumer ethnocentric scale (CETSCALE) in an advanced and transitional country: The case of Canada and Russia. International Journal of Management, 22(4), 556.

- Sauer, P. C., & Seuring, S. (2023). How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions. In Review of Managerial Science (Vol. 17, Issue 5). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, G., Otter, T., & Strebinger, A. (1997). The influence of country-of-origin and brand on product evaluation and buying intention: An empirical study with Austrian consumers. Marktforschung & Management, 41(2), 39-44.

- Shankarmahesh, M. N. (2006). Consumer ethnocentrism: an integrative review of its antecedents and consequences. International Marketing Review, 23(2), 146-172. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. (2011). Service quality, satisfaction and behaviour intentions: Examining the moderating influence of visitor characteristics and destination image. Anatolia, 22(3), 362-377. [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T. A., & Sharma, S. (1987). Consumer ethnocentrism: construction and validation of the CETSCALE. Journal of marketing research, 24(3), 280-289. [CrossRef]

- Siamagka, N. T., & Balabanis, G. (2015). Revisiting consumer ethnocentrism: Review, reconceptualization, and empirical testing. Journal of International Marketing, 23(3), 66-86. [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M. S. (2005). Malaysian consumers’ evaluation of products made in Germany: The country of origin effect. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 17(1), 89-105. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, N., Jain, S. C., & Sikand, K. (2004). An experimental study of two dimensions of country-of-origin (manufacturing country and branding country) using intrinsic and extrinsic cues. International Business Review, 13(1), 65-82. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104(July), 333–339. [CrossRef]

- Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R. A., & Price, L. L. (2012). Branded products as a passport to global citizenship: Perspectives from developed and developing countries. Journal of International Marketing, 20(4), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Thakor, M. V., & Kohli, C. S. (1996). Brand origin: Conceptualization and review. Journal of consumer Marketing, 13(3), 27-42. [CrossRef]

- Tse, D. K., & Lee, W. N. (1993). Removing negative country images: Effects of decomposition, branding, and product experience. Journal of International Marketing, 1(4), 25-48. [CrossRef]

- Ulgado, F. M., & Lee, M. (1993). Consumer evaluations of bi-national products in the global market. Journal of International Marketing, 1(3), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Usunier, J. C. (2006). Relevance in business research: the case of country-of-origin research in marketing. European Management Review, 3(1), 60-73. [CrossRef]

- Usunier, J. C. (2011). The shift from manufacturing to brand origin: Suggestions for improving COO relevance. International Marketing Review, 28(5), 486-496. [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P. W., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. (1999). A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), 521-546. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L., & Chen, Z. X. (2004). Consumer ethnocentrism and willingness to buy domestic products in a developing country setting: Testing moderating effects. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(6), 391-400. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Lamb, C. W. (1983). The impact of selected environmental forces upon consumers' willingness to buy foreign products. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 11(2), 71-84. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Yang, Z., & Liu, N. R. (2012). The impacts of brand personality and congruity on purchase intention: Evidence from the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. Journal of Global Marketing, 25(2), 58-74. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. J., & Wright, K. (2000). Consumer ethnocentrism and attitudes toward domestic and foreign products. European Journal of Marketing, 34(9/10), 1149-1166. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N. M., Noor, M. N., & Mohamad, O. (2007). Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity?. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 16(1), 38-48. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).