1. Introduction

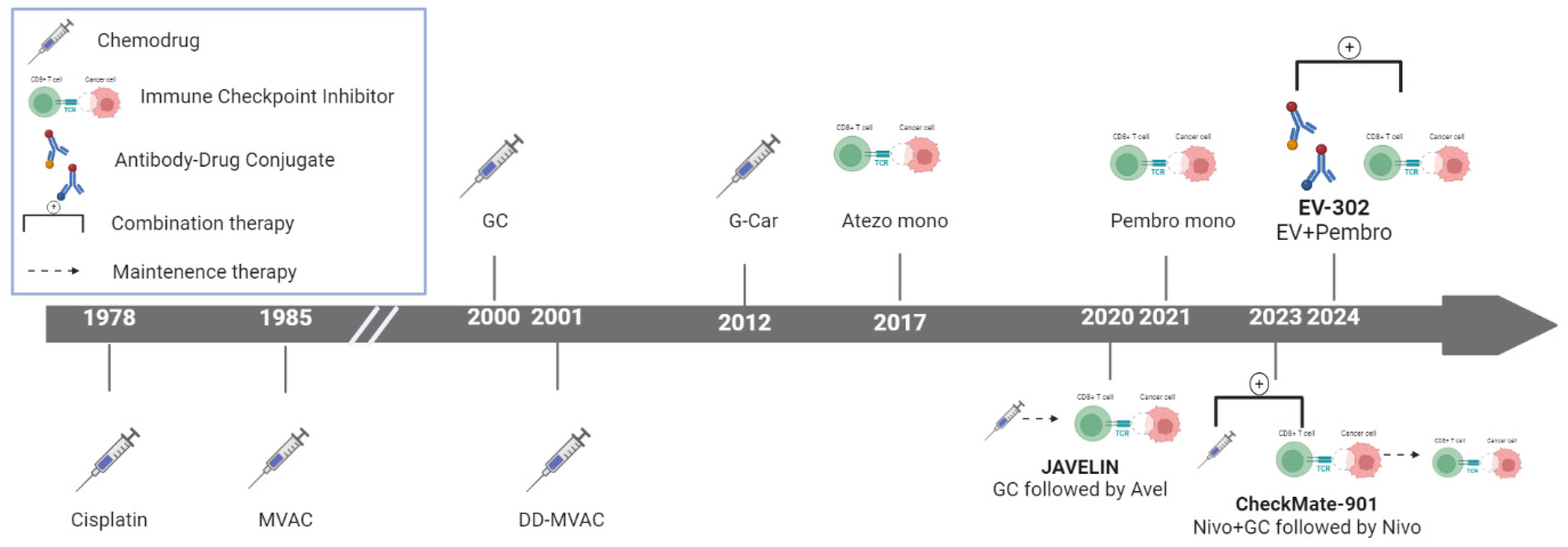

Significant advancements have recently been made in the therapeutic landscape of metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) (

Figure 1), a disease that poses formidable challenges in clinical oncology 1. Bladder cancer (BC), the tenth most common malignancy worldwide, accounted for approximately 573,000 new cases and 213,000 deaths in 2020. Urothelial carcinoma (UC), the most prevalent histological subtype, particularly in the United States and Europe, presents as metastatic in 5%–10% of patients at diagnosis 2. While approximately 75% of newly diagnosed cases are categorized as non-muscle-invasive BC, the remaining 25% are identified as muscle-invasive BC or metastatic disease. The prognosis for patients with mUC is particularly dire, with >90% of those with metastatic disease succumbing to the illness within 5 years 3.

Historically, the treatment of mUC has relied heavily on cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens such as gemcitabine–cisplatin (GC) and methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC), often supplemented with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for primary prophylaxis. Despite being the standard of care, these regimens yield a median (m) overall survival (OS) of approximately 14 months, and up to 50% of patients are ineligible for cisplatin owing to comorbidities, poor performance status, or renal impairment. For these patients, alternatives include carboplatin and gemcitabine, as well as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) 4.

There has been a transformative shift in the treatment of mUC with the introduction of ICIs, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), and targeted therapies 5. ICIs, such as pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, have gained regulatory approval for use in patients ineligible for cisplatin-based therapy, especially those whose tumors express programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), or in patients unsuitable for any form of platinum-based chemotherapy. Notably, pembrolizumab has demonstrated a significant survival benefit compared with second-line chemotherapy in patients who progress after platinum-based treatment 6.

A significant advancement in managing mUC has been the molecular characterization of the disease, leading to the approval of targeted therapies, such as erdafitinib (fibroblast growth factor receptor [FGFR] inhibitor), for patients with FGFR-altered tumors 7. These developments have broadened therapeutic options, particularly for patients who have progressed on or are ineligible for traditional chemotherapy.

Another notable milestone in mUC treatment is the approval of avelumab as a switch maintenance therapy following first-line chemotherapy. This strategy has demonstrated the ability to extend OS in patients responding to initial treatment 8. Recently, the results of the phase III EV-302 trial, which compared the combination of enfortumab vedotin (EV) and pembrolizumab as initial treatment, have challenged the established platinum-based treatment paradigm in mUC. The efficacy of this combination was further validated when the EV-302 trial successfully met its co-primary endpoints of OS and progression-free survival (PFS), marking a pivotal moment in mUC treatment and signaling a potential shift in the standard of care 9.

Nevertheless, mUC management remains complex and challenging. Determining the optimal therapy for each patient, identifying appropriate treatment sequences, and exploring potential synergies among therapeutic agents are critical areas of ongoing research 10. Real-world data suggest that only 30%–40% of patients receiving primary therapy for mUC proceed to second-line treatment, underscoring the need for effective first-line treatments and improved strategies for subsequent lines of therapy 11.

In this review, we explored the current therapeutic landscape of mUC, focusing on latest advancements and emerging treatment options. The challenges associated with optimizing treatment strategies and establishing effective treatment sequences, and the importance of personalized approaches in improving survival outcomes for patients with this aggressive disease have also been discussed.

2. Type and Mechanism of Drug Classes Used in the Frontline Treatment of mUC

2.1. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy

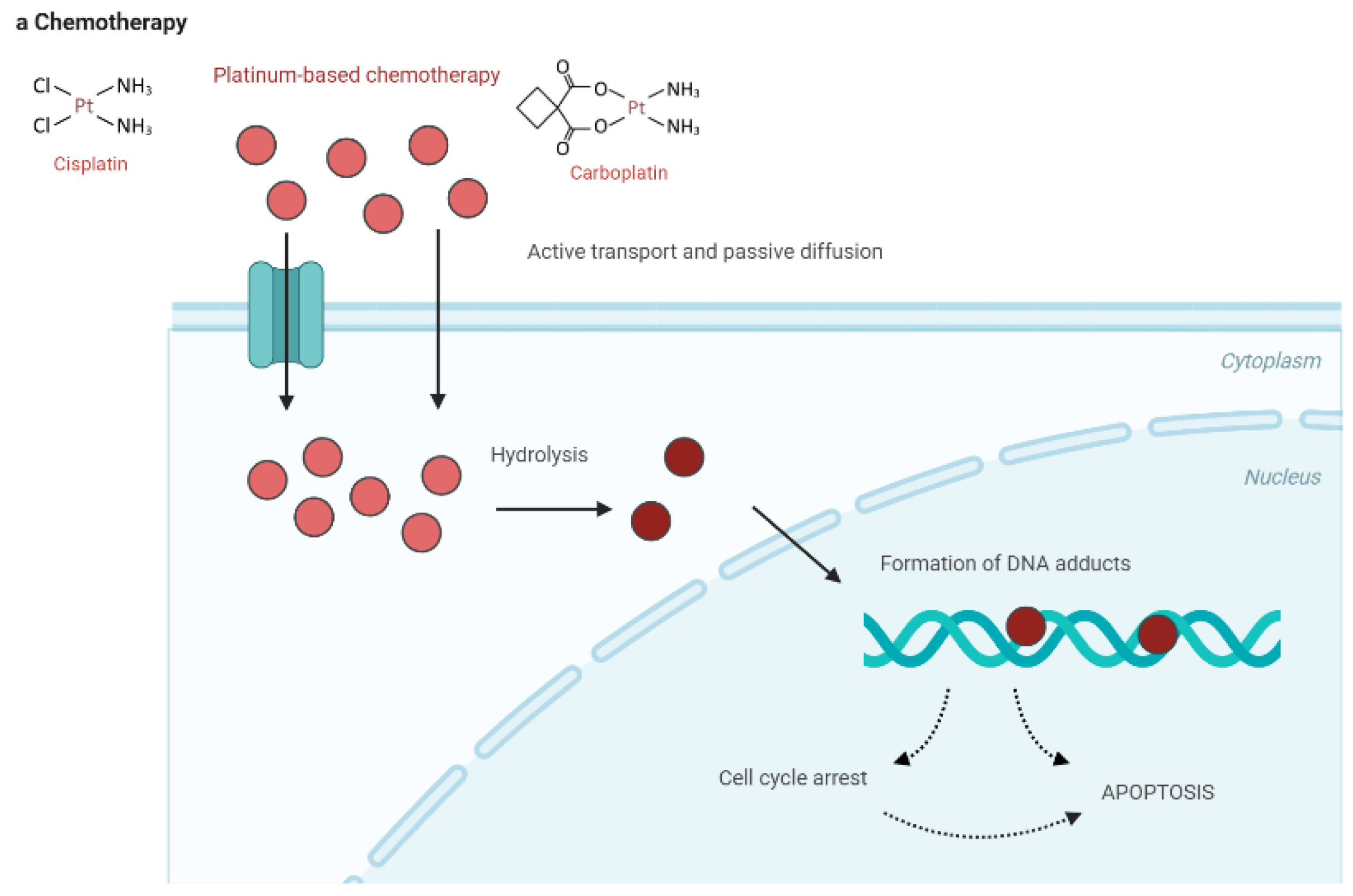

Platinum-based chemotherapy, particularly with agents like cisplatin, primarily exerts its anticancer effects by forming DNA cross-links that disrupt the DNA double helix, thereby inhibiting critical processes such as DNA replication and transcription. This damage activates cellular stress responses, including DNA damage response pathways, leading to cell cycle arrest, and ultimately, apoptosis. Apoptosis is further enhanced by the activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway and the tumor suppressor protein p53. Additionally, platinum compounds induce the production of reactive oxygen species, which further damage cellular components and amplify apoptosis. Although highly effective, platinum compounds affect normal cells, leading to nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity 12-14. The multifaceted action of platinum-based drugs underscores their effectiveness in cancer treatment, particularly in bladder cancer; however, their use requires careful management to balance efficacy with adverse effects.

2.2. ICIs

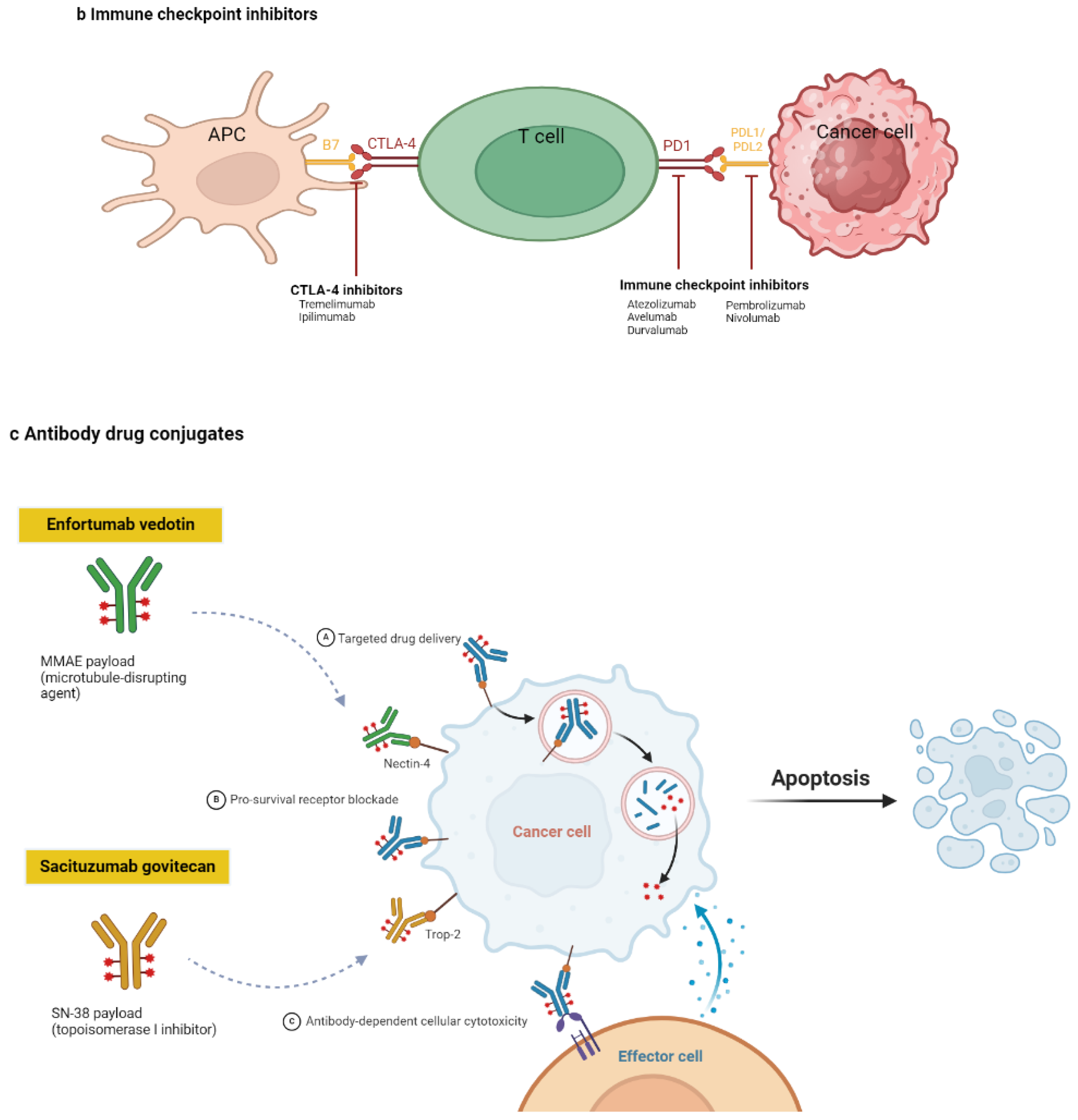

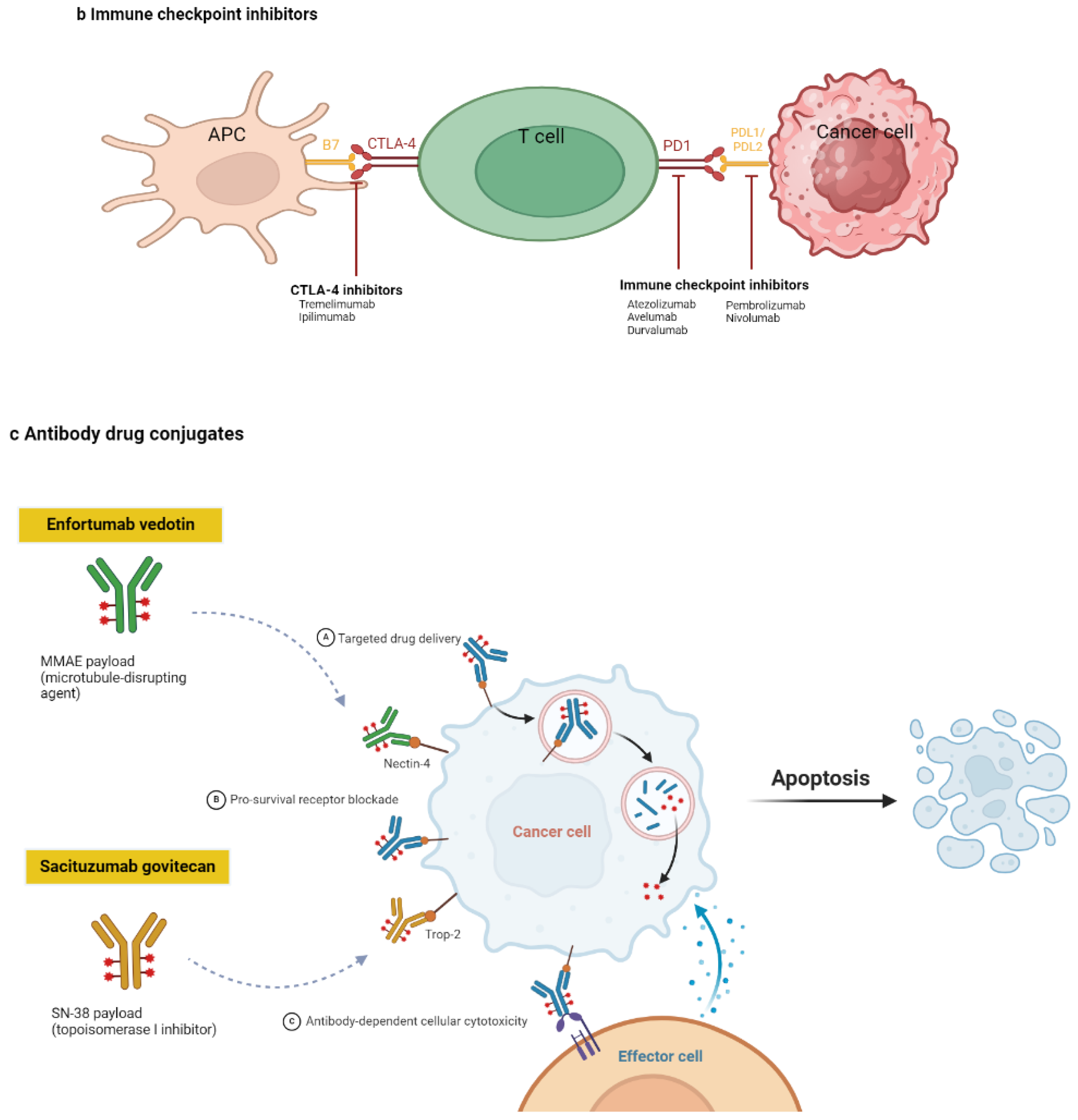

ICIs represent a significant advancement in cancer therapy by enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and eliminate tumor cells 15. ICIs act by blocking specific immune checkpoint pathways that normally maintain self-tolerance and modulate immune responses 16. Under physiological conditions, immune checkpoints are crucial for preventing autoimmunity and limiting the extent of immune responses to avoid excessive tissue damage. However, tumors often exploit these pathways to evade immune surveillance 17.

Two of the most well-studied immune checkpoints targeted by ICIs are cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), along with its ligand, PD-L1. CTLA-4 is expressed on activated T cells and functions as an inhibitory receptor by competing with the co-stimulatory receptor CD28 for binding to B7 molecules (B7-1/CD80 and B7-2/CD86) on antigen-presenting cells. The binding of CTLA-4 to B7 molecules transmits an inhibitory signal that reduces T cell activation and proliferation. By blocking the interaction between CTLA-4 and B7, CTLA-4 inhibitors, such as ipilimumab, enhance T cell activation, thereby promoting a robust immune response against cancer cells 18-20.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway plays a similar role in regulating immune responses. PD-1 is expressed on T, B, and natural killer cells. When PD-1 binds to its ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2, it delivers an inhibitory signal that dampens T cell activity, proliferation, and cytokine production. Tumor cells often upregulate PD-L1 to suppress T cell-mediated immune responses, effectively protecting themselves from immune attack. ICIs targeting this pathway, such as PD-1 inhibitors (e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab) or PD-L1 inhibitors (e.g. atezolizumab, durvalumab), block the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, thereby maintaining T cell activity and enabling them to target and destroy tumor cells.

The therapeutic efficacy of ICIs is a consequence of their ability to "release the brakes" on the immune system, allowing for enhanced T cell activation and sustained anti-tumor responses. This mechanism is effective across various malignancies, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and UC 21-23.

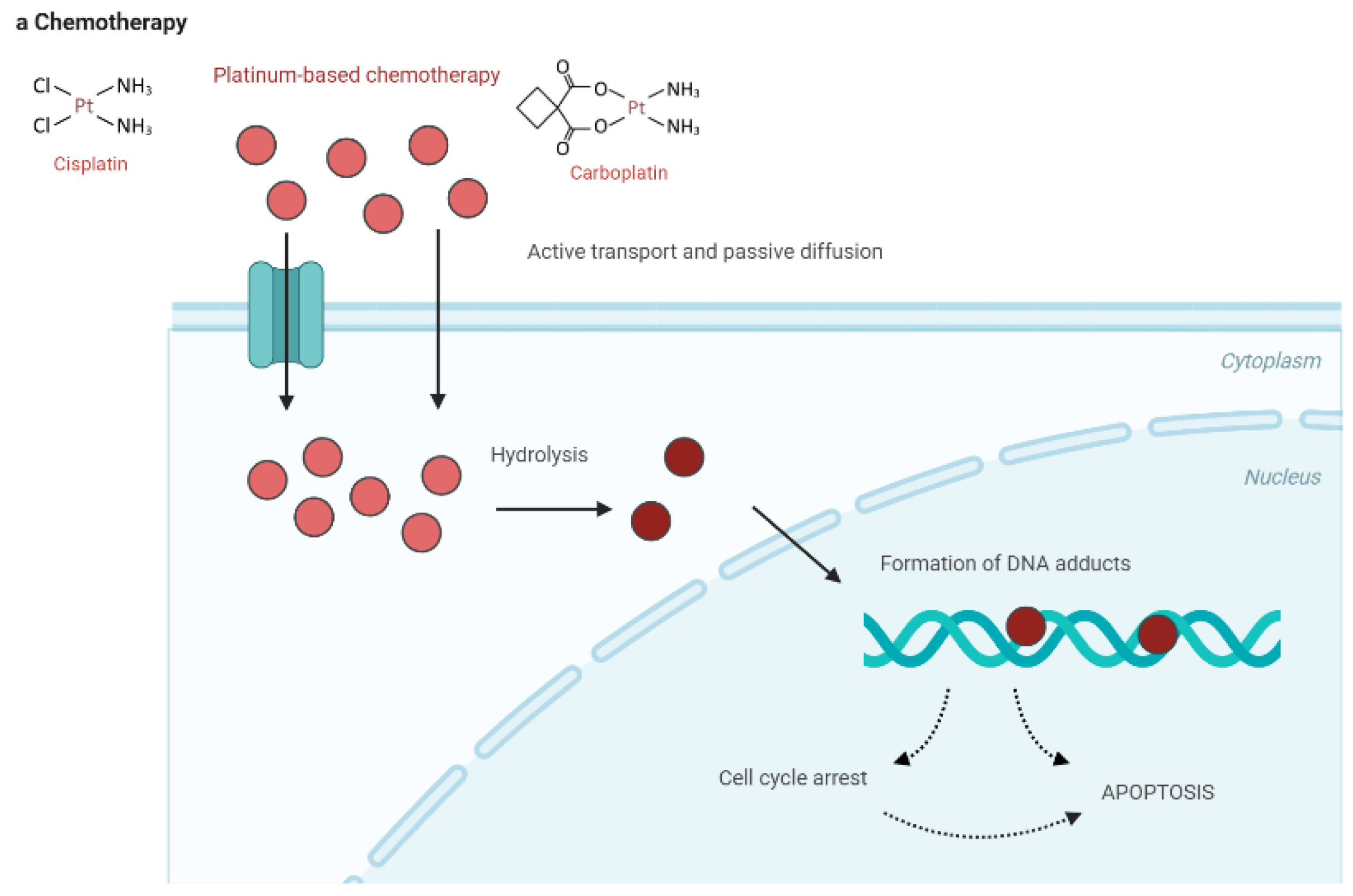

2.3. ADCs

ADCs are a class of targeted cancer therapies that combine the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents 24. Their mechanism of action involves several key steps, each critical to their ability to selectively target and kill cancer cells while minimizing damage to normal tissues 24, 25. The monoclonal antibody component of the ADC is designed to recognize and bind to a specific antigen overexpressed on cancer cell-surface. This antigen-binding property ensures that the ADC preferentially targets tumor cells while sparing most normal cells, which typically show low to no expression of the antigen. Once an ADC binds to the target antigen on the cancer cell surface, the entire complex is internalized through receptor-mediated endocytosis. After internalization, the ADC is trafficked to the lysosome, where the antibody-linked cytotoxic drug is released through various mechanisms, depending on the type of linker used in the ADC design. Linkers may be cleavable, breaking down owing to the acidic environment of the lysosome or through enzymatic action, or non-cleavable, where the drug is released only after the entire ADC is degraded. Once the cytotoxic drug is released inside the cancer cell, it interferes with critical cellular processes. Common payloads used in ADCs include highly potent chemotherapeutic agents, such as microtubule inhibitors (e.g. auristatins or maytansinoids) or DNA-damaging agents (e.g., calicheamicin). Microtubule inhibitors disrupt the microtubule network within the cell, preventing cell division and leading to apoptosis. DNA-damaging agents induce breaks in the DNA strand, leading to cell death through apoptosis or mitotic catastrophe.

The high potency of these cytotoxic drugs, which may be too toxic for systemic administration, is mitigated by the selective delivery mechanism of the ADC, concentrating the drug's effects within the tumor cells 26, 27. This selective targeting reduces the exposure of normal tissues to the cytotoxic drug, thereby minimizing systemic toxicity and enhancing the therapeutic index of the treatment. This targeted approach enables ADCs to deliver highly potent drugs directly to cancer cells, improving treatment efficacy while limiting off-target effects 28.

Figure 2 illustrates the mechanisms of the major drug classes used in the frontline treatment of mUC, including platinum-based chemotherapy, ICIs, and ADCs.

Figure 2.

Drug classes and their mechanisms in the frontline treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. a. Platinum-based chemotherapy works by disrupting cell division. Platinum compounds bind to the DNA of cancer cells, creating cross-links that impede normal DNA replication and cell division. This DNA damage hampers the cancer cells' growth and spread.b. Immunotherapy boosts the patient's immune system to fight against cancer cells. It works by blocking immune checkpoint pathways, such as PD1, PDL1, and CTLA4, which tumor cells use to evade immune detection. By inhibiting these pathways, immunotherapy enables the immune system to attack and eliminate cancer cells. c. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) consist of a cancer-specific antibody linked to a cytotoxic agent. Once the ADC attaches to the cancer cells, it is absorbed, and the toxic drug is released inside the cell, leading to cancer cell death. Enfortumab vedotin targets nectin-4, which is commonly overexpressed in urothelial cancer cells, while sacituzumab govitecan targets tumor cells through the anti-Trop-2 antibody. APC, antigen-presenting cell; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; MMAE, monomethyl auristatin; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PDL1, programmed death-ligand 1; PDL2, programmed death-ligand 2; SN-38, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin.

Figure 2.

Drug classes and their mechanisms in the frontline treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. a. Platinum-based chemotherapy works by disrupting cell division. Platinum compounds bind to the DNA of cancer cells, creating cross-links that impede normal DNA replication and cell division. This DNA damage hampers the cancer cells' growth and spread.b. Immunotherapy boosts the patient's immune system to fight against cancer cells. It works by blocking immune checkpoint pathways, such as PD1, PDL1, and CTLA4, which tumor cells use to evade immune detection. By inhibiting these pathways, immunotherapy enables the immune system to attack and eliminate cancer cells. c. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) consist of a cancer-specific antibody linked to a cytotoxic agent. Once the ADC attaches to the cancer cells, it is absorbed, and the toxic drug is released inside the cell, leading to cancer cell death. Enfortumab vedotin targets nectin-4, which is commonly overexpressed in urothelial cancer cells, while sacituzumab govitecan targets tumor cells through the anti-Trop-2 antibody. APC, antigen-presenting cell; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; MMAE, monomethyl auristatin; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PDL1, programmed death-ligand 1; PDL2, programmed death-ligand 2; SN-38, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin.

Figure 3.

Recommended treatment approaches for frontline in patients with mUC. a. All treatment decisions should be made only after thoroughly discussing the benefits and risks with the patient and/or their caregiver. Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; EV, enfortumab vedotin; GC, gemcitabine + cisplatin; Gem-Carbo, gemcitabine + carboplatin.

Figure 3.

Recommended treatment approaches for frontline in patients with mUC. a. All treatment decisions should be made only after thoroughly discussing the benefits and risks with the patient and/or their caregiver. Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; EV, enfortumab vedotin; GC, gemcitabine + cisplatin; Gem-Carbo, gemcitabine + carboplatin.

3. Patient Selection

Selecting the appropriate frontline therapy for patients with mUC is crucial for optimizing treatment outcomes. This process involves a comprehensive assessment of clinical, molecular, and patient-specific factors. Most patients with mUC are older, with the majority aged >65 years and approximately half being aged >70 years 29. This population often presents with comorbidities that complicate the use of standard cisplatin-based chemotherapy, which has long been the cornerstone of frontline treatment due to its proven efficacy 30. Consequently, many such patients are ineligible for cisplatin-based therapy, traditionally defined by factors such as an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of ≥2 31. Given the nephrotoxic nature of cisplatin, renal function assessment is essential, with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) of ≥60 mL/min typically serving as the threshold for cisplatin eligibility 32. Patients with renal impairment, indicated by a CrCl below this level, are often considered unsuitable for cisplatin and receive alternative treatments, such as carboplatin-based regimens or ICIs 33.

While the cisplatin ineligibility criteria are relatively well-defined, the ineligibility criteria for carboplatin-based chemotherapy remain unclear, leading to variability in clinical practice 34. The approval of ICIs for first-line treatment of platinum-ineligible patients, including those unable to receive cisplatin or carboplatin, underscores the need for consistent definitions of platinum ineligibility 4. Consensus definitions suggest that patients with an ECOG PS of ≥3, CrCl of <30 mL/min, peripheral neuropathy grade > 3, or New York Heart Association heart failure class > 3 should be considered ineligible for platinum-based chemotherapy 35. Additionally, patients with an ECOG PS of 2 and CrCl of <30 mL/min may also be ineligible for platinum-based therapies. However, these criteria may not capture all relevant factors, such as advanced age, poorly controlled diabetes, or inadequate bone marrow reserve, which could further contraindicate the use of platinum-based treatments 4.

The first formal attempts to define cisplatin eligibility in mUC were made in the 1990s. A survey by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer identified a CrCl of ≥60 mL/min and a World Health Organization performance status of 0 or 1 as key requirements for cisplatin use 36. These criteria were refined in 2011 by Galsky et al., whose guidelines for cisplatin ineligibility have since become widely adopted in clinical practice 37. Despite this, some debate persists regarding the exact renal function thresholds for cisplatin eligibility, with CrCl cutoffs ranging from <45 mL/min to <60 mL/min, depending on the context 38.

In addition to these clinical considerations, molecular biomarkers have become increasingly important in guiding frontline therapy decisions, particularly regarding immunotherapy 39. High PD-L1 expression may identify patients more likely to benefit from ICIs, such as pembrolizumab or atezolizumab, especially those ineligible for cisplatin. However, PD-L1 expression alone should not be the sole factor in determining treatment but rather part of a broader clinical assessment 40. The histological subtype of UC also influences treatment decisions. Variants such as micropapillary, sarcomatoid, or neuroendocrine differentiation may respond differently to standard therapies, requiring a more personalized approach. In these cases, strategies such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy or enrollment in clinical trials may offer better outcomes 41.

Patient preferences and quality of life are also critical in selecting frontline therapy. Having a thorough discussion with patients regarding the potential benefits and risks of each treatment option is essential, considering how these will impact their daily life and long-term prognosis 29. This ensures that the chosen treatment aligns with the patient’s values and goals. Moreover, eligibility for clinical trials can provide access to novel therapies that may not yet be widely available 42.

Finally, the presence of specific genomic alterations, such as FGFR3 mutations, can guide the selection of targeted therapies, although these are currently used in the second-line setting. Ongoing research may expand their use in frontline therapy, further personalizing treatment approaches for patients with mUC 43.

Selecting frontline therapy for mUC requires a multifaceted evaluation, including performance status, renal function, comorbidities, molecular biomarkers, histological subtype, and patient preferences. A personalized approach is essential to optimize treatment outcomes and improve overall prognosis for patients with mUC.

Table 1 provides an overview of key factors involved in selecting the appropriate frontline therapy for patients with mUC.

4. Clinical Development

4.1. Chemotherapy

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy has long been the cornerstone of managing mUC, with an overall response rate (ORR) of approximately 50%, PFS of up to 7 months, and an mOS of 13–15 months 44, 45. Historically, the MVAC regimen was favored due to its superior OS compared to cisplatin monotherapy and other combinations like cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin. However, MVAC application has been limited by severe toxicities, including grade ≥3 leukopenia, neutropenic fever, mucositis, and gastrointestinal adverse events, with a notable drug-associated mortality rate of 3–4% 45, 46.

In a crucial phase III trial, the GC regimen was compared to MVAC, showing similar long-term OS and PFS outcomes but with better tolerability regarding adverse effects and quality of life, leading many oncologists to prefer GC over MVAC 46. Subsequently, high-dose-intensity chemotherapy with dose-dense (dd) MVAC plus G-CSF every 2 weeks demonstrated reduced toxicity and improved response rates compared to the conventional 4-week MVAC schedule 47, 48. Another phase III study reported similar outcomes between ddGC and ddMVAC, further supporting the use of either regimen based on patient tolerance 49.

For cisplatin-ineligible patients, carboplatin-based regimens have been employed, typically owing to renal impairment or other comorbidities. However, outcomes with carboplatin-based combinations have generally been considered inferior to cisplatin-based regimens, although evidence is limited by underpowered trials 50. Recent analyses, such as those from the DANUBE, IMvigor130, and JAVELIN-100 trials, continue to suggest the superiority of cisplatin over carboplatin in platinum-eligible patients 51-53. Split-dose administration of cisplatin has been considered for patients with borderline renal function, offering a potentially less nephrotoxic alternative while maintaining efficacy 54. However, the VEFORA GETUG-AFU V06 study, comparing split-dose cisplatin with standard-dose carboplatin, was halted due to excessive toxicities in the cisplatin arm 55.

Regarding chemotherapy cycles, consensus guidelines recommend 2–6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy 56. Post-hoc analysis from the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial suggests that survival benefits from maintenance avelumab are consistent regardless of whether patients received 4, 5, or 6 cycles of chemotherapy 57. Advances in treatment have diminished the role of second- and later-line chemotherapy regimens, which previously offered limited benefits over best supportive care (BSC) 58.

4.2. Immunotherapy

4.2.1. First-Line Monotherapy for Platinum-Ineligible Patients

ICIs such as atezolizumab and pembrolizumab have been extensively evaluated as monotherapy for cisplatin-ineligible patients with mUC 4. Atezolizumab was one of the first ICIs studied in this setting. The phase II IMvigor210 trial evaluated atezolizumab as a first-line therapy in 119 patients with locally advanced or metastatic (la/m) UC who were ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy 59. The trial reported an ORR of 23%, with 9% of patients achieving a complete response (CR) (mOS, 15.9 months). Atezolizumab demonstrated a manageable safety profile, with grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurring in 16% of patients. Despite these promising results, in May 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety alert after early data from the IMvigor130 trial and another study suggested decreased survival for patients receiving atezolizumab as first-line monotherapy compared to those receiving platinum-based chemotherapy 60. Consequently, the FDA restricted the use of atezolizumab as a first-line treatment to patients who were either ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy with high PD-L1 expression (≥5% of immune cells) or those ineligible for any platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of PD-L1 status 60. The IMvigor130 trial, a multicenter phase III study, further examined atezolizumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy 52. However, this trial did not show a significant overall survival advantage for atezolizumab monotherapy over chemotherapy alone. Consequently, the manufacturer voluntarily withdrew the first-line indication for atezolizumab in mUC in November 2022 11. Nevertheless, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Panel continues to recommend atezolizumab as a first-line option for specific patient populations, particularly those not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumors express PD-L1 or those ineligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 status (category 2B recommendation) 56.

Following atezolizumab, pembrolizumab was evaluated as a first-line monotherapy option for cisplatin-ineligible patients in the phase II KEYNOTE-052 trial 61, where pembrolizumab demonstrated an ORR of 24%, with 5% of patients achieving a CR. Long-term outcomes remained consistent, with an ORR of 28.6% and mOS of 11.3 months. However, similar to atezolizumab, the FDA issued a safety alert for pembrolizumab in May 2018 based on early findings from the KEYNOTE-361 trial, which suggested decreased survival in patients treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy compared to those receiving platinum-based chemotherapy 62. Therefore, the FDA restricted the use of pembrolizumab as a first-line treatment to patients who were ineligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and had high PD-L1 expression (combined positive score ≥ 10) or those ineligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 status 6. Pembrolizumab's indication was further limited to patients ineligible for any platinum-based chemotherapy, with the NCCN Panel continuing to recommend it as a first-line treatment for cisplatin-ineligible patients regardless of PD-L1 status, and specifically endorsing its use for those ineligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy 56.

Overall, while both atezolizumab and pembrolizumab provided new therapeutic options for cisplatin-ineligible patients with mUC, their use as first-line monotherapies has been restricted due to concerns over OS outcomes—particularly in patients with low PD-L1 expression—and the NCCN's continued endorsement of these therapies, albeit with specific limitations, underscores the importance of careful patient selection in the management of mUC.

4.2.2. First-Line Combination Therapy

Combination therapies involving ICIs and chemotherapy have been extensively investigated in mUC treatment. However, these efforts have generally yielded less favorable outcomes than anticipated 63. For instance, the phase III trials IMvigor130 and KEYNOTE-361 evaluated the efficacy of atezolizumab and pembrolizumab, respectively, either as monotherapies or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy, compared to chemotherapy alone 52, 64. The KEYNOTE-361 trial showed negligible improvements in PFS or OS when pembrolizumab was combined with platinum-based chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone in patients with mUC. Similarly, the final survival analysis from the IMvigor130 study did not demonstrate a significant OS advantage for the combination of atezolizumab with platinum and gemcitabine over chemotherapy alone in mUC patients 65. Nevertheless, exploratory data suggested a potential benefit of atezolizumab monotherapy in first-line cisplatin-ineligible patients with high PD-L1 expression, although these findings were not statistically significant. Interestingly, the analysis highlighted a disparity in outcomes based on the choice of platinum agent, with a potentially greater benefit observed when atezolizumab was combined with cisplatin instead of carboplatin, suggesting the need for further investigation into the optimal chemotherapy regimen.

The phase III DANUBE trial further explored ICI combinations by evaluating durvalumab, an anti-PD-L1 agent, either as a monotherapy or in combination with tremelimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 agent, against standard chemotherapy in patients with mUC 51. Unfortunately, the trial failed to meet its co-primary endpoints, which included OS comparisons between durvalumab monotherapy and chemotherapy in patients with high PD-L1 expression, as well as that between durvalumab-tremelimumab combination and chemotherapy in the overall population. Despite these disappointing results, the promising activity observed in the PD-L1-high population led to the revision of the NILE protocol, which now focuses on untreated mUC patients with high PD-L1 expression. The results of this global phase III trial are highly anticipated and may redefine treatment approaches for this subset of patients 66.

Contrastingly, the multinational phase III CheckMate 901 study demonstrated the efficacy of adding nivolumab to GC chemotherapy in 608 patients with previously untreated, unresectable, or mUC 67. In this study, 251 patients who received the nivolumab combination continued with maintenance nivolumab for up to 2 years. After a median follow-up of 33.6 months, the results showed that the nivolumab plus GC combination significantly improved mOS compared to GC alone (21.7 vs. 18.9 months; HR, 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–0.96; P=.02). Although the median PFS (mPFS) was similar between the two groups (7.9 vs. 7.6 months; P=.001), the PFS curves began to diverge over time, with a higher percentage of patients remaining progression-free at 12 months in the nivolumab combination group (34.2% vs. 21.8%). Furthermore, the ORR was notably higher in the nivolumab combination group (57.6% vs. 43.1%), with a CR rate of 21.7% compared to 11.8% in the chemotherapy-alone group. However, the combination therapy was associated with a higher incidence of grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs (TRAEs), occurring in 61.8% of patients compared to 51.7% in the chemotherapy-alone group. These findings significantly advanced first-line mUC treatment, leading to the regimen being designated as a category 1 recommendation by the NCCN Panel 56. The results from the CheckMate-901 trial stand in contrast to earlier phase III trials, such as KEYNOTE-361 and IMvigor130, which did not show significant improvements in either OS or PFS when ICIs like pembrolizumab or atezolizumab were added to platinum-based chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of mUC. Differences in the immunomodulatory effects of cisplatin and carboplatin may partially explain the discrepancies between these trials 67. Exploratory analyses of both KEYNOTE-361 and IMvigor130 suggested that combining ICIs with cisplatin-based therapy, but not carboplatin-based therapy, resulted in better outcomes. Specifically, pretreated tumors with higher PD-L1 expression were associated with more favorable outcomes in patients treated with GC but not with gemcitabine-carboplatin 68. Further supporting this hypothesis, single-cell RNA sequencing of circulating immune cells in the IMvigor130 trial revealed that GC, but not gemcitabine-carboplatin, upregulated immune-related transcriptional programs, including those involved in antigen presentation 69. These data suggest that cisplatin-based chemotherapy may have particularly favorable immunogenic effects when combined with ICIs in mUC treatment, providing a potential explanation for the positive results observed in the CheckMate-901 trial. This insight highlights the importance of chemotherapy selection in optimizing the efficacy of combination therapies in mUC.

4.2.3. Maintenance Therapy

Avelumab as maintenance therapy following platinum-based first-line chemotherapy has become a significant advancement in mUC treatment 70. This regimen is based on findings from the phase III JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial 53, which demonstrated that avelumab significantly prolongs OS compared to BSC alone in patients who achieved either a response or stable disease after first-line chemotherapy. Specifically, the trial showed an mOS of 21.4 months for patients treated with avelumab, compared to 14.3 months for those who received BSC alone, corresponding to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.56–0.86; P=.001). This OS benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups, including patients with PD-L1-positive tumors. Apart from the OS benefit, avelumab was also associated with a longer PFS compared to BSC alone. Importantly, preplanned subgroup analyses demonstrated that the OS benefit of avelumab was significant regardless of previous treatment with cisplatin or carboplatin and irrespective of the extent of the response to chemotherapy. Despite a higher incidence of subsequent treatments in the control group, including ICIs, the 12-month OS was substantially higher in the avelumab arm (71%) compared to the BSC arm (58%). The incidence of grade ≥3 AEs was higher in the avelumab group (47.4%) compared to the BSC group (25.2%). Yet, the safety profile of avelumab remained manageable over the long term, with the most common TRAEs including pruritus, hypothyroidism, fatigue, diarrhea, and asthenia. The JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial's findings have led to the NCCN assigning avelumab maintenance therapy a category 1 recommendation for patients with mUC who do not experience disease progression after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy 56. Subsequent extended follow-up data, with a median duration of 38 months, confirmed the durability of the OS and PFS benefits of avelumab, with an OS of 23.8 months versus 15.0 months (HR 0.76; 95% CI, 0.631–0.915; P=.0036) and a PFS of 5.5 months versus 2.1 months (HR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.457–0.645; P<.0001) 71.

Real-world studies conducted in Italy (READY study) and France (AVENANCE study) have further validated the clinical benefits and manageable safety profile of avelumab as a first-line maintenance therapy for patients with mUC 72, 73. These studies reported 12-month OS rates of 65.4%–69.2% and mPFS of 5.7–8.1 months, consistent with the findings of the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial.

Following the results of the CheckMate-901 trial, nivolumab has also emerged as a viable maintenance therapy option for patients with mUC who respond to nivolumab plus first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The trial demonstrated that nivolumab plus GC significantly improved outcomes in these patients, leading the NCCN to recommend nivolumab as an alternative maintenance therapy alongside avelumab 56. This expanded recommendation gives clinicians more flexibility when selecting an appropriate maintenance therapy based on patient-specific factors.

While both avelumab and nivolumab maintenance therapies have significantly improved outcomes for patients with mUC, ongoing phase II and phase III trials are exploring combinations of these agents with other therapies as first-line maintenance treatments. The optimal second-line therapy for patients with disease progression during or after maintenance therapy with either avelumab or nivolumab is still under investigation, and enrollment in clinical trials is strongly recommended to explore new therapeutic strategies 74.

4.3. EV Combination Therapy

The combination of the ICI pembrolizumab with the ADC EV has been explored extensively in mUC treatment 10. Initial studies were conducted within certain phase Ib/II EV-103 cohorts, mainly focusing on cisplatin-ineligible patients with previously untreated, la/mUC 75. In cohort A, 45 patients received the combination therapy, resulting in a confirmed ORR of 73.3%, including a CR rate of 15.6%. However, the treatment was associated with significant AEs, including peripheral sensory neuropathy (55.6%), fatigue (51.1%), and alopecia (48.9%), with 64.4% of patients experiencing grade ≥3 AEs, and one treatment-related death. Following the promising results from cohort A, cohort K of the EV-103 trial randomized cisplatin-ineligible patients to receive either EV alone or in combination with pembrolizumab. The combination therapy achieved a confirmed ORR of 64.5% (95% CI, 52.7%–75.1%) compared to 45.2% (95% CI, 33.5%–57.3%) for EV monotherapy. The median duration of response was not reached for the combination, whereas it was 13.2 months for the monotherapy.

Based on these findings, the combination was further evaluated in the phase III EV-302 trial, which involved 886 patients with previously untreated, la/mUC 9. Patients were randomized to receive either EV plus pembrolizumab or standard chemotherapy with gemcitabine in combination with either cisplatin or carboplatin. After a median follow-up of 17.2 months, the combination therapy significantly improved PFS and OS. Specifically, the mPFS was 12.5 months with the combination versus 6.3 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.38–0.54; P<.001), and the mOS was 31.5 months versus 16.1 months (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38–0.58; P<.001). Additionally, the confirmed ORR was 67.7% for the combination compared to 44.4% for chemotherapy, with CRs in 29.1% of patients in the combination group versus 12.5% in the chemotherapy group. Notably, grade ≥3 TRAEs occurred in 55.9% of patients receiving the combination therapy, compared to 69.5% of those receiving chemotherapy.

The impressive outcomes from the EV-302 trial led to the combination of EV and pembrolizumab being recognized as the preferred first-line systemic therapy for patients with advanced or mUC, regardless of cisplatin eligibility. This regimen has received a category 1 designation from the NCCN panel, solidifying its status as a new standard of care in this setting 56.

4.3.1. EV-302 and JAVELIN Paradigm Versus CheckMate-901

In the evolving treatment landscape of mUC, the role of GC/nivo (gemcitabine/cisplatin with nivolumab) and the JAVELIN paradigm is being reevaluated in light of impressive data from EV/pembro (enfortumab vedotin with pembrolizumab) 9. The significance of GC/nivo in cisplatin-eligible patients is underscored by several factors. Firstly, cisplatin-based combination therapies have historically demonstrated potential cures in 5% to 15% of patients 46, 48. The long-term CR observed in approximately 22% of patients receiving GC/nivo further support the possibility of achieving a cure in a subset of patients 67. While EV/pembro may also lead to cures, long-term follow-up is required to confirm this potential. Secondly, Compared to EV/pembro, GC/nivo offers a finite duration of chemotherapy, providing advantages in terms of reduced toxicity and improved patient quality of life during treatment 9, 67. Additionally, GC/nivo is more cost-effective compared to EV/pembro, making it a financially viable option for many healthcare systems and patients 76, 77. Moreover, GC/nivo may be considered for patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or liver dysfunction due to specific safety and tolerability considerations associated with EV 67, 78, 79. These comorbidities can complicate treatment plans, and the regimen's tolerability in such conditions enhances its clinical applicability.

The identification of biomarkers predictive of CR is crucial for advancing precision medicine in mUC. Disease confined to lymph nodes serves as a favorable prognostic factor for both cisplatin-based chemotherapy and PD-1 inhibition, suggesting that aggressive use of GC/nivo is recommended for this patient group 80, 81. Additionally, ERCC2 mutations, previously validated for predicting pathological CR with neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy, may serve as candidates for predicting CR with cisplatin-based therapy 82.

Given that aggressive multi-agent combination therapies are feasible only in suitable patients in real-world settings, all first-line regimens—including EV/pembro, GC/nivo, and the JAVELIN paradigm—have legitimate roles in clinical practice 56.

Despite the availability of maintenance immunotherapy, its optimal implementation in real-world practice appears limited. In the EV-302 study, only 32.2% of patients received a PD-1/L1 inhibitor as maintenance therapy after platinum-based chemotherapy, and only 20% of patients in the GC arm of the CheckMate-901 study received a PD-1/L1 inhibitor before progression. The suboptimal application of the JAVELIN paradigm may be attributed to attrition from disease progression, persistent toxicities, poor ECOG performance status (PS), frailty, comorbidities, and patient decisions 74. Therefore, potent first-line regimens that provide early and durable benefits—such as EV/pembro and GC/nivo, both of which induce rapid responses within 2–3 months—are expected to replace the JAVELIN paradigm for most patients. Nonetheless, in frail or vulnerable cisplatin-ineligible patients (including potentially some with ECOG PS 2), employing the JAVELIN paradigm of carboplatin/gemcitabine followed by maintenance avelumab may be a safer option.

Table 2.

summarizes key clinical trials in frontline therapy for mUC, highlighting the interventions, outcomes, and AEs associated with each treatment strategy.

Table 2.

summarizes key clinical trials in frontline therapy for mUC, highlighting the interventions, outcomes, and AEs associated with each treatment strategy.

| Table 2. Trial. |

Intervention arm |

Control arm |

Median PFS in the intervention arm (months) |

Median PFS in the control arm (months) |

Hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) |

P-value |

Median OS in the intervention arm (months) |

Median OS in the control arm (months) |

Hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) |

P-value |

CR (%) |

Adverse events |

| De Santis et al. 2009 50

|

Gemcitabine/Carboplatin |

Methotrexate/Carboplatin/Vinblastine |

Not available |

Not available |

|

|

9.3 |

8.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Sternberg et al. 2006 48

|

High-dose intensity M-VAC + G-CSF |

Classic M-VAC |

Not available |

Not available |

|

|

15.9 |

14.2 |

|

0.075 |

|

Reduced toxicity with dose-dense M-VAC |

| GC vs MVAC 45

|

Gemcitabine + Cisplatin |

MVAC |

7.0 |

7.5 |

Similar HR |

0.8 |

14.0 |

15.2 |

Similar HR |

0.6 |

|

GC better tolerability, lower toxicity (grade 3+ AE) |

| KEYNOTE-901 67

|

Nivolumab + GC |

Gemcitabine-cisplatin |

7.9 |

7.6 |

0.78 (0.63–0.96) |

0.02 |

21.7 |

18.9 |

0.78 (0.63–0.96) |

0.02 |

|

Grade 3+ TRAEs 61.8% vs 51.7% |

| JAVELIN-100 71

|

Avelumab (maintenance) |

Best Supportive Care |

5.5 |

2.1 |

0.69 (0.56–0.86) |

0.001 |

21.4 |

14.3 |

0.69 (0.56–0.86) |

0.001 |

|

Grade 3+ TRAEs 47% vs 25% |

| DANUBE 51

|

Durvalumab + tremelimumab |

Chemotherapy |

6.7 |

6.9 |

0.85 (0.71–1.02) |

0.075 |

15.1 |

12.1 |

0.85 (0.72–1.02) |

0.054 |

|

Grade 3+ TRAEs 61% vs 50% |

| IMvigor130 52

|

Atezolizumab + chemo |

Chemotherapy alone |

8.2 |

6.3 |

0.82 (0.70–0.96) |

0.007 |

16.0 |

13.4 |

0.83 (0.69–1.00) |

0.027 |

|

Grade 3+ TRAEs 81% vs 76% |

| IMvigor210 59

|

Atezolizumab (monotherapy) |

No control (single-arm) |

2.7 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

7.9 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Grade 3–4 TRAEs 16% |

| EV-103 95

|

EV + Pembrolizumab |

No control (single-arm) |

12.3 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

26.1 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Grade 3–4 TRAEs 54% |

| EV-302 9

|

EV + Pembrolizumab |

Standard chemotherapy |

12.5 |

6.3 |

0.45 (0.38–0.54) |

<0.001 |

31.5 |

16.1 |

0.47 (0.38–0.58) |

<0.001 |

|

Grade 3+ TRAEs 55.9% vs 69.5% |

| KEYNOTE-052 61

|

Pembrolizumab (monotherapy) |

No control (single-arm) |

2.1 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

11.3 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Grade 3–4 TRAEs 16% |

| KEYNOTE-361 64

|

Pembrolizumab + chemo |

Chemotherapy alone |

8.3 |

7.1 |

0.78 (0.65–0.93) |

0.003 |

17.0 |

14.3 |

0.86 (0.72–1.02) |

0.04 |

|

Grade 3–4 TRAEs 67% vs 63% |

5. Future Perspectives

The evolving landscape of frontline therapy for mUC presents significant advancements, yet several critical questions remain unresolved. Recent developments have introduced promising therapeutic agents and combinations, such as EV with pembrolizumab, which have shown substantial potential to enhance patient outcomes. However, challenges persist in determining the optimal sequencing, duration, and combination of these therapies, as well as in identifying predictive biomarkers that can guide clinical decision-making.

5.1. Challenges in Optimizing EV Plus Pembrolizumab for Frontline mUC Treatment

The introduction of EV with pembrolizumab in the frontline setting represents a significant shift in mUC treatment, with this combination showing promise as a potential standard of care for all patients, regardless of their eligibility for platinum-based chemotherapy. This change raises the possibility of reserving chemotherapy and targeted agents for later lines of treatment, adding complexity to treatment decisions 74. However, several questions remain, such as the optimal duration of therapy, sequencing of treatments, and the potential for EV rechallenge after discontinuation due to toxicity. Additionally, the role of EV plus pembrolizumab versus EV alone in patients who have previously received adjuvant immunotherapy is a crucial area of investigation 83, 84. Clinical trials are exploring these questions, including alternative dosing schedules and maintenance strategies, such as reducing the dosing frequency of EV or implementing maintenance pembrolizumab after an initial course of EV plus pembrolizumab 85.

As the mUC treatment landscape continues to evolve, the sequencing of therapies is becoming increasingly complex. The potential widespread adoption of EV plus pembrolizumab as frontline therapy may shift the use of chemotherapy and other targeted agents to subsequent lines, necessitating a re-evaluation of current treatment paradigms, particularly for patients who experience disease progression after first-line therapy 9, 86. Despite the promise of new combinations, questions remain regarding the role of chemotherapy after progression on EV plus pembrolizumab. Ongoing trials are examining the efficacy of various sequences, such as gemcitabine-carboplatin following EV plus pembrolizumab, and exploring the combination of newer agents like sacituzumab govitecan with pembrolizumab 87, 88. These studies aim to identify the best strategies for managing mUC in a rapidly changing therapeutic environment.

5.2. Biomarkers of Response

Identifying predictive biomarkers is crucial in frontline mUC treatment to guide therapeutic decisions. Predicting which patients will benefit most from specific regimens, such as EV plus pembrolizumab, GC with nivolumab followed by maintenance, or other chemo-immunotherapy combinations, is essential for optimizing outcomes 89. Current research has made significant progress in this area, particularly with biomarkers related to immunotherapy, such as PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability, defective mismatch repair phenotype, and tumor mutational burden 90. Emerging biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and gut microbiota, also show promise but require further validation 91. The STING trial underscored the potential of plasma ctDNA sequencing in mUC 92. The trial demonstrated the feasibility and reliability of ctDNA in identifying actionable targets and promptly initiating genotype-specific therapies. These findings highlight the growing importance of biomarkers in tailoring frontline treatments to individual patients.

5.3. Managing Toxicities in Frontline Therapy

The emergence of EV plus pembrolizumab as a frontline treatment brings not only efficacy but also challenges in managing associated toxicities. Peripheral neuropathy and skin reactions are among the most-reported AEs of EV, requiring careful management, especially in patients with comorbidities such as diabetes. While these toxicities are generally manageable, they can lead to treatment interruptions or discontinuation, emphasizing the need for strategies to mitigate these effects 9, 93. Given the increasing use of EV plus pembrolizumab, there is a growing focus on optimizing dosing schedules to minimize toxicity while maintaining efficacy. For example, ongoing clinical trials are exploring fixed-duration EV therapy followed by pembrolizumab maintenance as a potential approach to improve patient quality of life 94.

To address these challenges, numerous ongoing trials are being conducted to explore optimal dosing, sequencing, and combination strategies in mUC.

Table 3 provides an overview of ongoing clinical trials in mUC, highlighting the interventions, target populations, and primary endpoints under investigation.

6. Conclusions

The evolving landscape of frontline mUC treatment is marked by a shift from traditional platinum-based chemotherapy to more innovative and targeted therapies, such as EV plus pembrolizumab and GC plus nivolumab followed by nivolumab maintenance. These regimens have significantly improved survival outcomes, offering effective first-line options for a broader range of patients, including those previously ineligible for cisplatin-based treatments. As EV plus pembrolizumab becomes increasingly favored owing to its substantial impact on PFS and OS, managing its associated toxicities, such as neuropathy and other AEs, remains a critical challenge. Similarly, the GC plus nivolumab combination, with its potential for durable responses, particularly in node-only disease, offers new hope for curative outcomes. These developments signal a significant shift in the treatment paradigm.

Future efforts should focus on optimizing treatment strategies, identifying biomarkers to tailor therapies, and further understanding resistance mechanisms. As new frontline therapies are integrated into clinical practice, their long-term impact on outcomes and quality of life of patients will continue to shape the future of mUC treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.K. M.K.L; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.K.; writing—review and editing, W.A.K., M.K.L. supervision, W.A.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2022R1F1A061069), and the Technology Innovation Program (20008924), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nadal, R.; Valderrama, B.P.; Bellmunt, J. Progress in systemic therapy for advanced-stage urothelial carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 21, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witjes, J.A.; Bruins, H.M.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; Gakis, G.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; Lorch, A.; Neuzillet, Y.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2020 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2020, 79, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, M.J.; Campbell, M.T.; Alhalabi, O. Revisiting Treatment of Metastatic Urothelial Cancer: Where Do Cisplatin and Platinum Ineligibility Criteria Stand? Biomedicines 2024, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, W.-A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jeong, T.Y.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, M.-K. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Urothelial Cancer: From Scientific Rationale to Clinical Development. Cancers 2024, 16, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzman, D.L.; Agrawal, S.; Ning, Y.-M.; Maher, V.E.; Fernandes, L.L.; Karuri, S.; Tang, S.; Sridhara, R.; Schroeder, J.; Goldberg, K.B.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab or Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma Ineligible for Cisplatin-Containing Chemotherapy. Oncol. 2018, 24, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.J.; Hsu, R. Treatment approaches for FGFR-altered urothelial carcinoma: targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1258388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, M.; Shimizu, T.; Oda, Y.; Tachibana, A.; Ohmori, C.; Itami, Y.; Kiba, K.; Tomioka, A.; Yamamoto, H.; Ohnishi, K.; et al. Switch-maintenance avelumab immunotherapy following first-line chemotherapy for patients with advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: the first Japanese real-world evidence from a multicenter study. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 53, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gupta, S.; Bedke, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Iyer, G.; Vulsteke, C.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.J.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin and Pembrolizumab in Untreated Advanced Urothelial Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhu, C.; You, X.; Gu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bu, R.; Wang, K. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates in the treatment of urogenital tumors: a review insights from phase 2 and 3 studies. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.M.; Jo, Y.; Tripathi, N.; Roy, S.; Chigarira, B.; Narang, A.; Gebrael, G.; Chehade, C.H.; Sayegh, N.; Fortuna, G.G.; et al. Treatment Patterns and Attrition With Lines of Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e249417–e249417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgie, B.N.; Prakash, R.; Telleria, C.M. Revisiting the Anti-Cancer Toxicity of Clinically Approved Platinating Derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazonova, E.V.; Kopeina, G.S.; Imyanitov, E.N.; Zhivotovsky, B. Platinum drugs and taxanes: can we overcome resistance? Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O’byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wu, H.; Wu, J.; Ding, P.; He, J.; Sang, M.; Liu, L. Mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitors: insights into the regulation of circular RNAS involved in cancer hallmarks. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhan, H.; Ye, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Zhuang, Y. Current Progress and Future Perspectives of Immune Checkpoint in Cancer and Infectious Diseases. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 785153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Xu, L.; Yi, M.; Yu, S.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Novel immune checkpoint targets: moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtukiewicz, M.Z.; Rek, M.M.; Karpowicz, K.; Górska, M.; Polityńska, B.; Wojtukiewicz, A.M.; Moniuszko, M.; Radziwon, P.; Tucker, S.C.; Honn, K.V. Inhibitors of immune checkpoints—PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4—new opportunities for cancer patients and a new challenge for internists and general practitioners. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; Shabafrouz, K.; Ribi, C.; Cairoli, A.; Guex-Crosier, Y.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Liu D, Li L. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 727–742.

- Gao, M.; Shi, J.; Xiao, X.; Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J. PD-1 regulation in immune homeostasis and immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2024, 588, 216726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, C.; Luong, G.; Sun, Y. A snapshot of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parit, S.; Manchare, A.; Gholap, A.D.; Mundhe, P.; Hatvate, N.; Rojekar, S.; Patravale, V. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: A promising breakthrough in cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 659, 124211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Bordeau, B.M.; Balthasar, J.P. Mechanisms of ADC Toxicity and Strategies to Increase ADC Tolerability. Cancers 2023, 15, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, H.E.; Cenciarelli, C.; Hasan, A. Potential of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, D.; Yang, J.; Salam, A.; Sengupta, S.; Al-Amin, Y.; Mustafa, S.; Khan, M.A.; Huang, X.; Pawar, J.S. Antibody-drug conjugates: the paradigm shifts in the targeted cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1203073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemenway, G.; Anker, J.F.; Riviere, P.; Rose, B.S.; Galsky, M.D.; Ghatalia, P. Advancements in Urothelial Cancer Care: Optimizing Treatment for Your Patient. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2024, 44, e432054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Mottet, N.; De Santis, M. Urothelial carcinoma management in elderly or unfit patients. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2016, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Ma, E.; Shah-Manek, B.; Mills, R.; Ha, L.; Krebsbach, C.; Blouin, E.; Tayama, D.; Ogale, S. Cisplatin Ineligibility for Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Survey of Clinical Practice Perspectives Among US Oncologists. Bl. Cancer 2019, 5, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, S.S.; Sandhu, S.K.; Kitchlu, A. Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity: Novel Insights Into Mechanisms and Preventative Strategies. Semin. Nephrol. 2023, 42, 151341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Comperat, E.; De Santis, M.; Huddart, R.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Valderrama, B.; Ravaud, A.; Shariat, S.; et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline interim update on first-line therapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Andreev-Drakhlin, A.; Fajardo, O.; Fassò, M.; A Garcia, J.; Wee, C.; Schröder, C. Platinum ineligibility and survival outcomes in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma receiving first-line treatment. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 116, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Bellmunt, J.; Plimack, E.R.; Sonpavde, G.P.; Grivas, P.; Apolo, A.B.; Pal, S.K.; Siefker-Radtke, A.O.; Flaig, T.W.; Galsky, M.D.; et al. Defining “platinum-ineligible” patients with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 4577–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, R. Overview of bladder cancer trials in the European Organization for Research and Treatment. Cancer 2003, 97, 2120–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Hahn, N.M.; Rosenberg, J.; Sonpavde, G.; Hutson, T.; Oh, W.K.; Dreicer, R.; Vogelzang, N.; Sternberg, C.; Bajorin, D.F.; et al. A consensus definition of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, G.; Alqaisi, H.; Chan, C.T.; Jiang, D.M.; Kandel, C.; Pelletier, K.; Wald, R.; Sridhar, S.S.; Kitchlu, A. Kidney and Cancer Outcomes with Standard Versus Alternative Chemotherapy Regimens for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Kidney360 2023, 4, e1203–e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Molina, J.R. Comparative Analysis of Predictive Biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Cancers: Developments and Challenges. Cancers 2021, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, B.A.; Di Maio, M.; Cerbone, L.; Maiello, E.; Procopio, G.; Roviello, G.; MeetURO Group; Accettura, C. ; Aieta, M.; Alberti, M.; et al. Significance of PD-L1 in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e241215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claps, F.; Biasatti, A.; Di Gianfrancesco, L.; Ongaro, L.; Giannarini, G.; Pavan, N.; Amodeo, A.; Simonato, A.; Crestani, A.; Cimadamore, A.; et al. The Prognostic Significance of Histological Subtypes in Patients with Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: An Overview of the Current Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamat, A.M.; Apolo, A.B.; Babjuk, M.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Black, P.C.; Buckley, R.; Campbell, M.T.; Compérat, E.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Grivas, P.; et al. Definitions, End Points, and Clinical Trial Designs for Bladder Cancer: Recommendations From the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer and the International Bladder Cancer Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5437–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascione, C.M.; Napolitano, F.; Esposito, D.; Servetto, A.; Belli, S.; Santaniello, A.; Scagliarini, S.; Crocetto, F.; Bianco, R.; Formisano, L. Role of FGFR3 in bladder cancer: Treatment landscape and future challenges. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 115, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenis, A.T.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K. Bladder cancer: A review. JAMA 2020, 324, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Der Maase, H.; Hansen, S.W.; Roberts, J.T.; Dogliotti, L.; Oliver, T.; Moore, M.J.; Bodrogi, I.; Albers, P.; Knuth, A.; Lippert, C.M.; et al. Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Versus Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin in Advanced or Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Results of a Large, Randomized, Multinational, Multicenter, Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3068–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Maase, H.; Sengelov, L.; Roberts, J.T.; Ricci, S.; Dogliotti, L.; Oliver, T.; Moore, M.J.; Zimmermann, A.; Arning, M. Long-Term Survival Results of a Randomized Trial Comparing Gemcitabine Plus Cisplatin, With Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, Plus Cisplatin in Patients With Bladder Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4602–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, C.N.; de Mulder, P.H.; Schornagel, J.H.; Théodore, C.; Fossa, S.D.; van Oosterom, A.T.; Witjes, F.; Spina, M.; van Groeningen, C.J.; de Balincourt, C.; et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of High–Dose-Intensity Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin (MVAC) Chemotherapy and Recombinant Human Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor Versus Classic MVAC in Advanced Urothelial Tract Tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Protocol No. 30924. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 2638–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, C.; de Mulder, P.; Schornagel, J.; Theodore, C.; Fossa, S.; van Oosterom, A.; Witjes, J.; Spina, M.; van Groeningen, C.; Duclos, B.; et al. Seven year update of an EORTC phase III trial of high-dose intensity M-VAC chemotherapy and G-CSF versus classic M-VAC in advanced urothelial tract tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamias, A.; Dafni, U.; Karadimou, A.; Timotheadou, E.; Aravantinos, G.; Psyrri, A.; Xanthakis, I.; Tsiatas, M.; Koutoulidis, V.; Constantinidis, C.; et al. Prospective, open-label, randomized, phase III study of two dose-dense regimens MVAC versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with inoperable, metastatic or relapsed urothelial cancer: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study (HE 16/03). Ann. Oncol. 2012, 24, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.; Bellmunt, J.; Mead, G.; Kerst, J.M.; Leahy, M.; Maroto, P.; Skoneczna, I.; Marreaud, S.; de Wit, R.; Sylvester, R. Randomized Phase II/III Trial Assessing Gemcitabine/ Carboplatin and Methotrexate/Carboplatin/Vinblastine in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Cancer “Unfit” for Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy: Phase II—Results of EORTC Study 30986. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5634–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Castellano, D.; Loriot, Y.; Ogawa, O.; Park, S.H.; De Giorgi, U.; Bögemann, M.; Bamias, A.; Gurney, H.; Fradet, Y.; et al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1574–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galsky, M.D.; Arija, J.Á.A.; Bamias, A.; Davis, I.D.; De Santis, M.; Kikuchi, E.; Garcia-Del-Muro, X.; De Giorgi, U.; Mencinger, M.; Izumi, K.; et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterman, C.K.; Babu, D.S.; Geynisman, D.M.; Lewis, B.; Somer, R.A.; Balar, A.V.; Zibelman, M.R.; Guancial, E.A.; Antinori, G.; Yu, S.; et al. Efficacy of Split Schedule Versus Conventional Schedule Neoadjuvant Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Oncol. 2019, 24, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, L.; Flechon, A.; Tosi, D.; Lacourtoisie, S.A.; Joly, F.; Guillot, A.; Loriot, Y.; Dauba, J.; Roubaud, G.; Rolland, F.; et al. Vefora, GETUG-AFU V06 study: Randomized multicenter phase II/III trial of fractionated cisplatin (CI)/gemcitabine (G) or carboplatin (CA)/g in patients (pts) with advanced urothelial cancer (UC) with impaired renal function (IRF)—Results of a planned interim analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 461–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines Version 4.2024 "Bladder Cancer". Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1417 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Grivas, P.; Grande, E.; Davis, I.; Moon, H.; Grimm, M.-O.; Gupta, S.; Barthélémy, P.; Thibault, C.; Guenther, S.; Hanson, S.; et al. Avelumab first-line maintenance treatment for advanced urothelial carcinoma: review of evidence to guide clinical practice. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tan, A.; Shah, A.Y.; Iyer, G.; Morris, V.; Michaud, S.; Sridhar, S.S. Reevaluating the role of platinum-based chemotherapy in the evolving treatment landscape for patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma. Oncol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balar, A.V.; Galsky, M.D.; Rosenberg, J.E.; et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Walker, J.; Williams, J.A.; Bellmunt, J. The evolving role of PD-L1 testing in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 82, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuky, J.; Balar, A.V.; Castellano, D.; O’donnell, P.H.; Grivas, P.; Bellmunt, J.; Powles, T.; Bajorin, D.; Hahn, N.M.; Savage, M.J.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes in KEYNOTE-052: Phase II Study Investigating First-Line Pembrolizumab in Cisplatin-Ineligible Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2658–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatalia, P.; Zibelman, M.; Geynisman, D.M.; Plimack, E.R. First-line Immunotherapy in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Focus 2019, 6, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhea, L.P.; Aragon-Ching, J.B. Advances and Controversies With Checkpoint Inhibitors in Bladder Cancer. Clin. Med. Insights: Oncol. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Matsubara, N.; Cheng, S.Y.-S.; Fradet, Y.; Oudard, S.; Vulsteke, C.; Barrera, R.M.; Gunduz, S.; Loriot, Y.; Rodriguez-Vida, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (KEYNOTE-361): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, E.; Bamias, A.; Galsky, M.D.; Kikuchi, E.; Davis, I.D.; Arranz, J.A.; Rezazadeh, A.; del Muro, X.G.; Park, S.H.; De Giorgi, U.; et al. Overall survival (OS) by response to first-line (1L) induction treatment with atezolizumab (atezo) + platinum/gemcitabine (plt/gem) vs placebo + plt/gem in patients (pts) with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC): Updated data from the IMvigor130 OS final analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4503–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Necchi, A.; Sridhar, S.S.; Ogawa, O.; Angra, N.; Hois, S.; Xiao, F.; Goluboff, E.; Bellmunt, J. A phase III, randomized, open-label, multicenter, global study of first-line durvalumab plus standard of care (SoC) chemotherapy and durvalumab plus tremelimumab, and SoC chemotherapy versus SoC chemotherapy alone in unresectable locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (NILE). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, TPS504–TPS504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M.; Sade, J.P.; Bamias, A.; Beuzeboc, P.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus Gemcitabine–Cisplatin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssiau, H.; Seront, E. Improving the role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of advanced urothelial carcinoma, where do we stand? Transl. Oncol. 2022, 19, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Guan, X.; Banchereau, R.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Yu, H.; Rishipathak, D.; Hajaj, E.; Herbst, R.; Davis, I.; et al. 658MO Cisplatin (cis)-related immunomodulation and efficacy with atezolizumab (atezo) + cis- vs carboplatin (carbo)-based chemotherapy (chemo) in metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC). Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S682–S683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.-A.; Seo, H.K. Emerging agents for the treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2021, 62, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Ullén, A.; Loriot, Y.; Sridhar, S.S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Bellmunt, J.; et al. Avelumab First-Line Maintenance for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma: Results From the JAVELIN Bladder 100 Trial After ≥2 Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3486–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracarda, S.; Antonuzzo, L.; Maruzzo, M.; Santini, D.; Tambaro, R.; Buti, S.; Carrozza, F.; Calabrò, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Fornarini, G.; et al. Subgroup analyses from READY: Real-world data from an Italian compassionate use program (CUP) of avelumab first-line maintenance (1LM) treatment for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 558–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelemy, P.; Loriot, Y.; Voog, E.; Eymard, J.C.; Ravaud, A.; Flechon, A.; Jaillon, C.A.; Chasseray, M.; Lorgis, V.; Hilgers, W.; et al. Full analysis from AVENANCE: A real-world study of avelumab first-line (1L) maintenance treatment in patients (pts) with advanced urothelial carcinoma (aUC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 471–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasalu, V.K.; Robbrecht, D. Advancements in First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Bladder Cancer: EV-302 and Checkmate-901 Insights and Future Directions. Cancers 2024, 16, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Donnell, P.H.; Milowsky, M.I.; Petrylak, D.P.; Hoimes, C.J.; Flaig, T.W.; Mar, N.; Moon, H.H.; Friedlander, T.W.; McKay, R.R.; Bilen, M.A.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin With or Without Pembrolizumab in Cisplatin-Ineligible Patients With Previously Untreated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4107–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Wang, C.; He, X.-Y.; Yao, Q.-M.; Chen, J. Comparative cost-effectiveness of first-line pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone in persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1345942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li A, Wu M, Xie O.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of First-Line Enfortumab Vedotin in Addition to Pembrolizumab for Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma in the United States. Frontiers in Immunology. 15, 1464092.

- Rosenberg, J.E.; O’Donnell, P.H.; Balar, A.V.; McGregor, B.A.; Heath, E.I.; Yu, E.Y.; Galsky, M.D.; Hahn, N.M.; Gartner, E.M.; Pinelli, J.M.; et al. Pivotal Trial of Enfortumab Vedotin in Urothelial Carcinoma After Platinum and Anti-Programmed Death 1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Garg, A.; Bonate, P.L.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Matsangou, M.; Kadokura, T.; Yamada, A.; Choules, M.; Pavese, J.; Nagata, M.; et al. Clinical Pharmacology of the Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enfortumab Vedotin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma and Other Malignant Solid Tumors. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2024, 63, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajorin, D.F.; Dodd, P.M.; Mazumdar, M.; Fazzari, M.; McCaffrey, J.A.; Scher, H.I.; Herr, H.; Higgins, G.; Boyle, M.G. Long-Term Survival in Metastatic Transitional-Cell Carcinoma and Prognostic Factors Predicting Outcome of Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 3173–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonpavde, G.; Manitz, J.; Gao, C.; Tayama, D.; Kaiser, C.; Hennessy, D.; Makari, D.; Gupta, A.; Abdullah, S.E.; Niegisch, G.; et al. Five-Factor Prognostic Model for Survival of Post-Platinum Patients with Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Receiving PD-L1 Inhibitors. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Plimack, E.R.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Garraway, L.A.; Bellmunt, J.; Van Allen, E.; Rosenberg, J.E. Clinical Validation of Chemotherapy Response BiomarkerERCC2in Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Nadal, R. Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab combination as a relevant game changer in urothelial carcinoma: What is left behind? Med 2024, 5, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni, M.; Takeshita, H.; Massari, F.; Bamias, A.; Cerbone, L.; Fiala, O.; Mollica, V.; Buti, S.; Santoni, A.; Bellmunt, J. Pembrolizumab plus enfortumab vedotin in urothelial cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2024, 21, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.M.; Mateen, R.; Qaddour, N.; Carrillo, A.; Verschraegen, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sundi, D.; Mortazavi, A.; Collier, K.A. A Comprehensive Review of Immunotherapy Clinical Trials for Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Alone or in Combination, Novel Antibodies, Cellular Therapies, and Vaccines. Cancers 2024, 16, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.S.; Tan, M.-Y.; Alhalabi, O.; Campbell, M.T.; Kamat, A.M.; Gao, J. Evolving systemic management of urothelial cancers. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2023, 35, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, P.; Pouessel, D.; Park, C.H.; Barthelemy, P.; Bupathi, M.; Petrylak, D.P.; Agarwal, N.; Gupta, S.; Fléchon, A.; Ramamurthy, C.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Combination With Pembrolizumab for Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Cancer That Progressed After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy: TROPHY-U-01 Cohort 3. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonni, E.; Oltrecolli, M.; Pirola, M.; Tchawa, C.; Roccabruna, S.; D’agostino, E.; Matranga, R.; Piombino, C.; Pipitone, S.; Baldessari, C.; et al. New Advances in Metastatic Urothelial Cancer: A Narrative Review on Recent Developments and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, P.; Marcq, G.; Adeleke, S.; Turpin, A.; Boussios, S.; Rassy, E.; Penel, N. Predictive biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitor response in urothelial cancer. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; de Souza, Z.S.; Gongora, A.B.L.; Barbosa, F.d.G.; Buchpiguel, C.A.; de Castro, M.G.; de Macedo, M.P.; Coelho, R.F.; Soko, E.S.; Camargo, A.A.; et al. Emerging biomarkers in metastatic urothelial carcinoma: tumour mutational burden, PD-L1 expression and APOBEC polypeptide-like signature in a patient with complete response to anti-programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitor. ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Qiu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Guan, X.; Cen, X.; Zhao, Y. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Baldini, C.; Bayle, A.; Pages, A.; Danlos, F.X.; Vasseur, D.; Rouleau, E.; Lacroix, L.; de Castro, B.A.; Goldschmidt, V.; et al. Impact of Clonal Hematopoiesis–Associated Mutations in Phase I Patients Treated for Solid Tumors: An Analysis of the STING Trial. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2300631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, B.; McCoy, A.; Ahmad, H.; Eitman, C.; Bowman, I.A.; Rembisz, J.; Milowsky, M.I. Managing potential adverse events during treatment with enfortumab vedotin + pembrolizumab in patients with advanced urothelial cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1326715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretelli, G.; Mati, K.; Motta, L.; Stathis, A. Antibody-drug conjugates combinations in cancer treatment. Explor. Target. Anti-tumor Ther. 2024, 5, 714–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Rosenberg, J.E.; McKay, R.R.; Flaig, T.W.; Petrylak, D.P.; Hoimes, C.J.; Friedlander, T.W.; Bilen, M.A.; Srinivas, S.; Burgess, E.F.; et al. Study EV-103 dose escalation/cohort A: Long-term outcome of enfortumab vedotin + pembrolizumab in first-line (1L) cisplatin-ineligible locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC) with nearly 4 years of follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4505–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).