Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

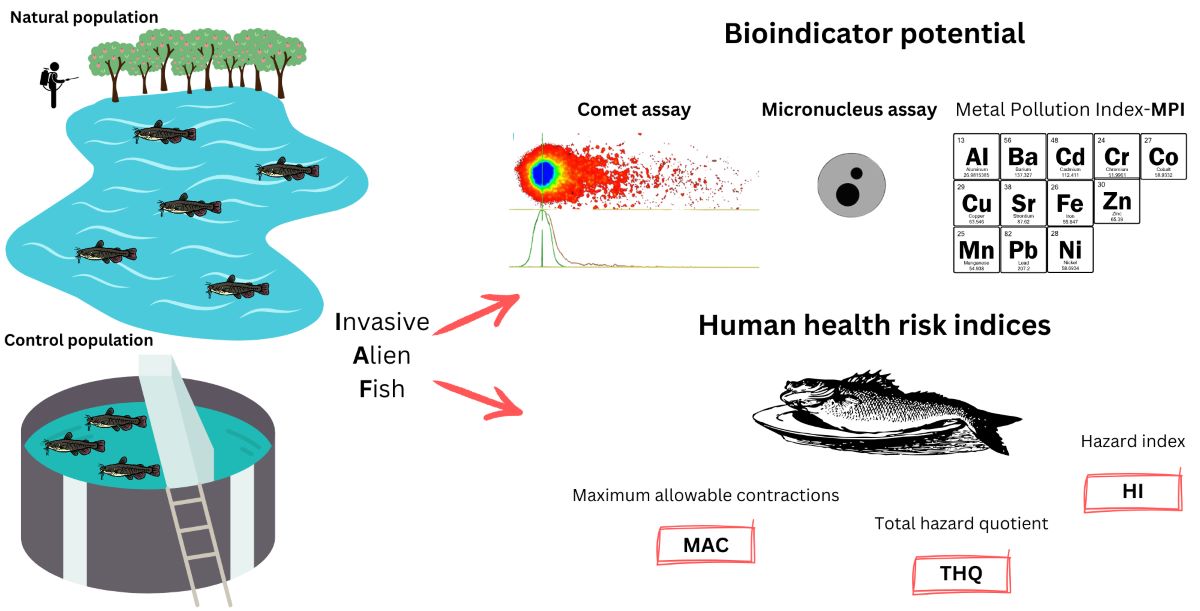

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

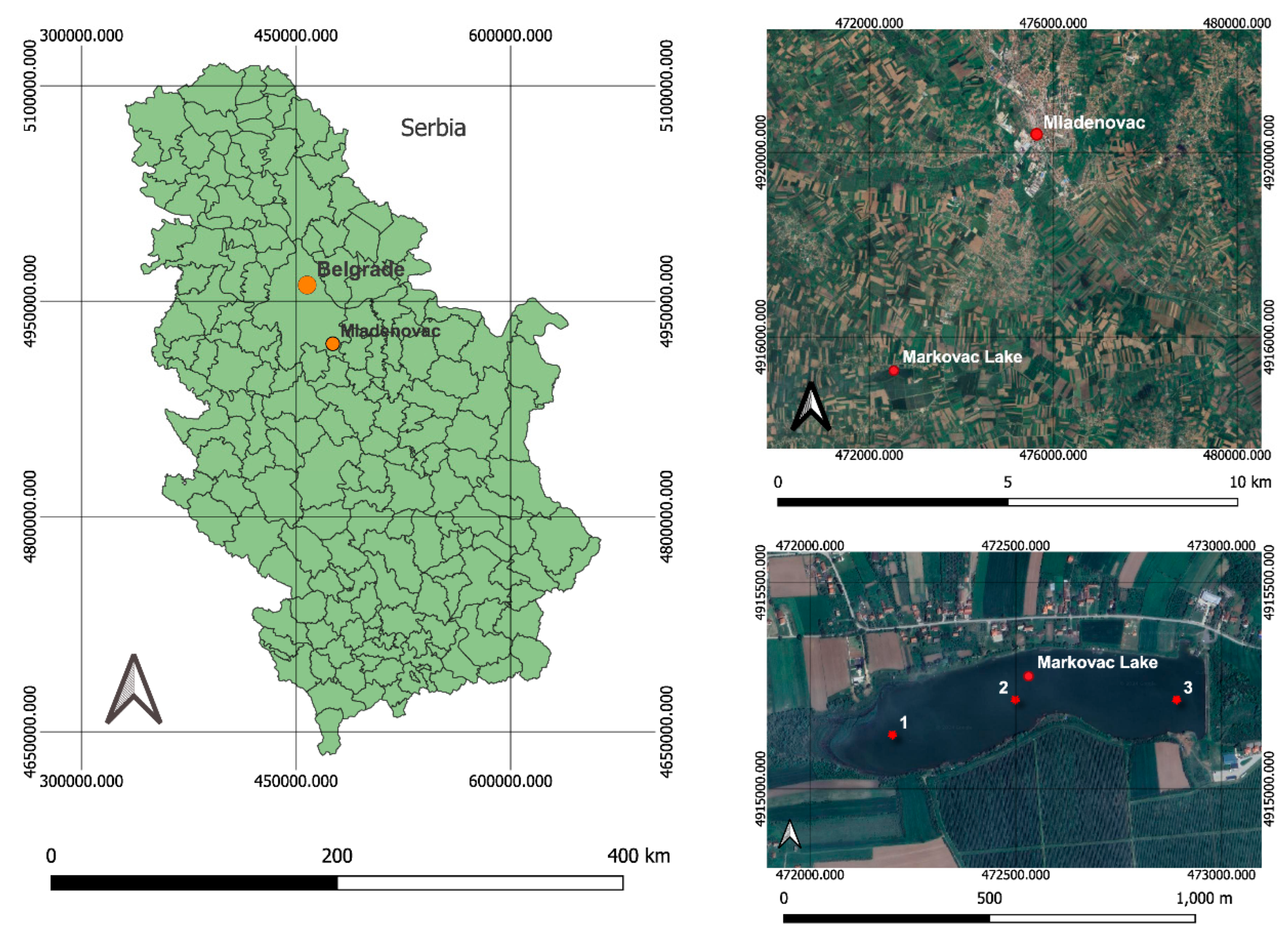

2.1. Sampling Site and Procedure

2.2. Analyses of Water

2.3. Fish Sampling

2.4. Alkaline Comet Assay

2.5. Micronucleus Assay

2.6. Analysis of Micro and Macro Elements in Muscle

2.7. Sediment Analysis

2.7.1. Sample Extraction

2.7.2. GC-MS Analysis

2.7.3. Method Validation and Accuracy Assurance

2.8. Integrated Biomarker Response (IBR) Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Analyses of Water

3.2. Fulton's Condition Factor

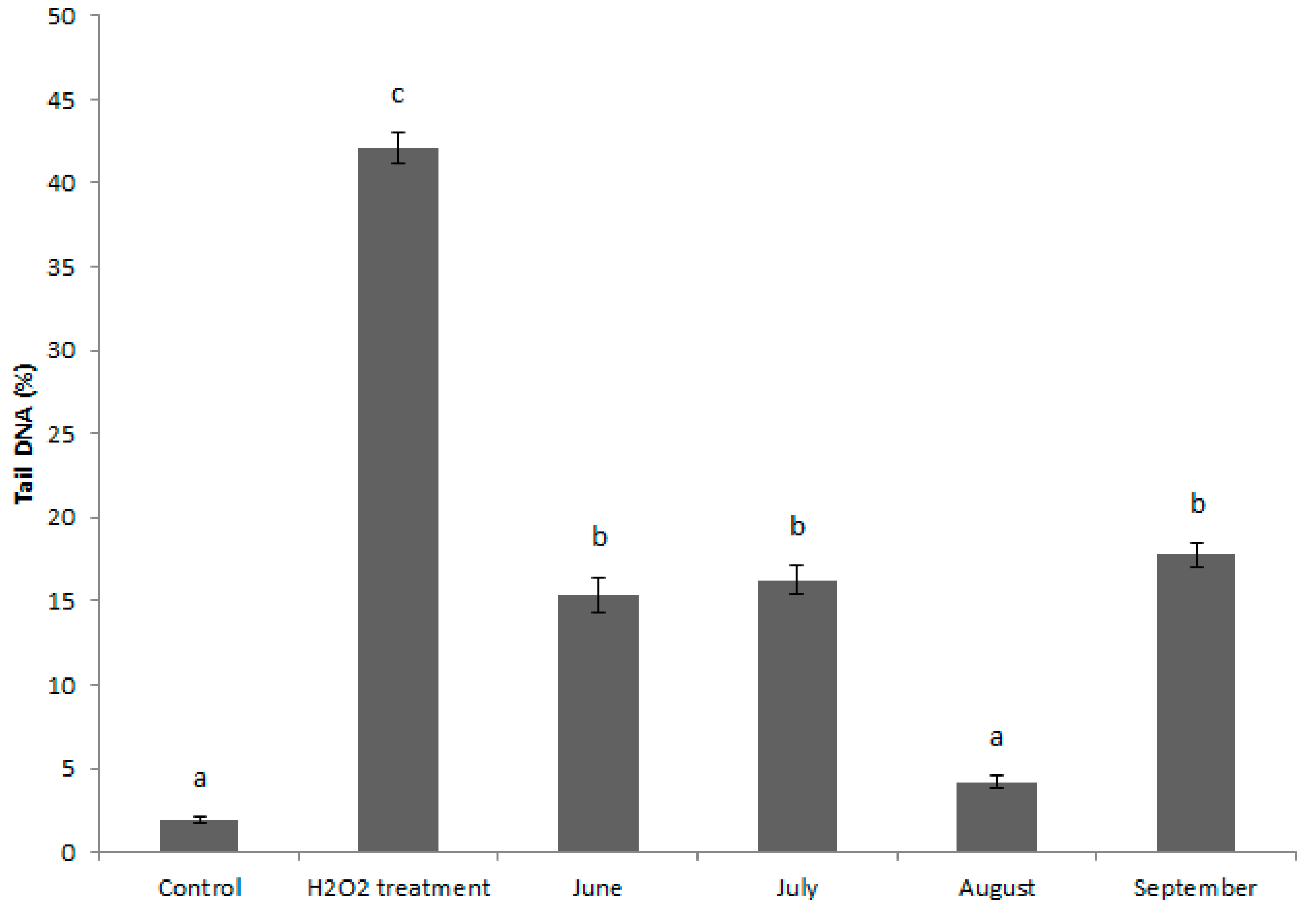

3.3. Alkaline Comet Assay

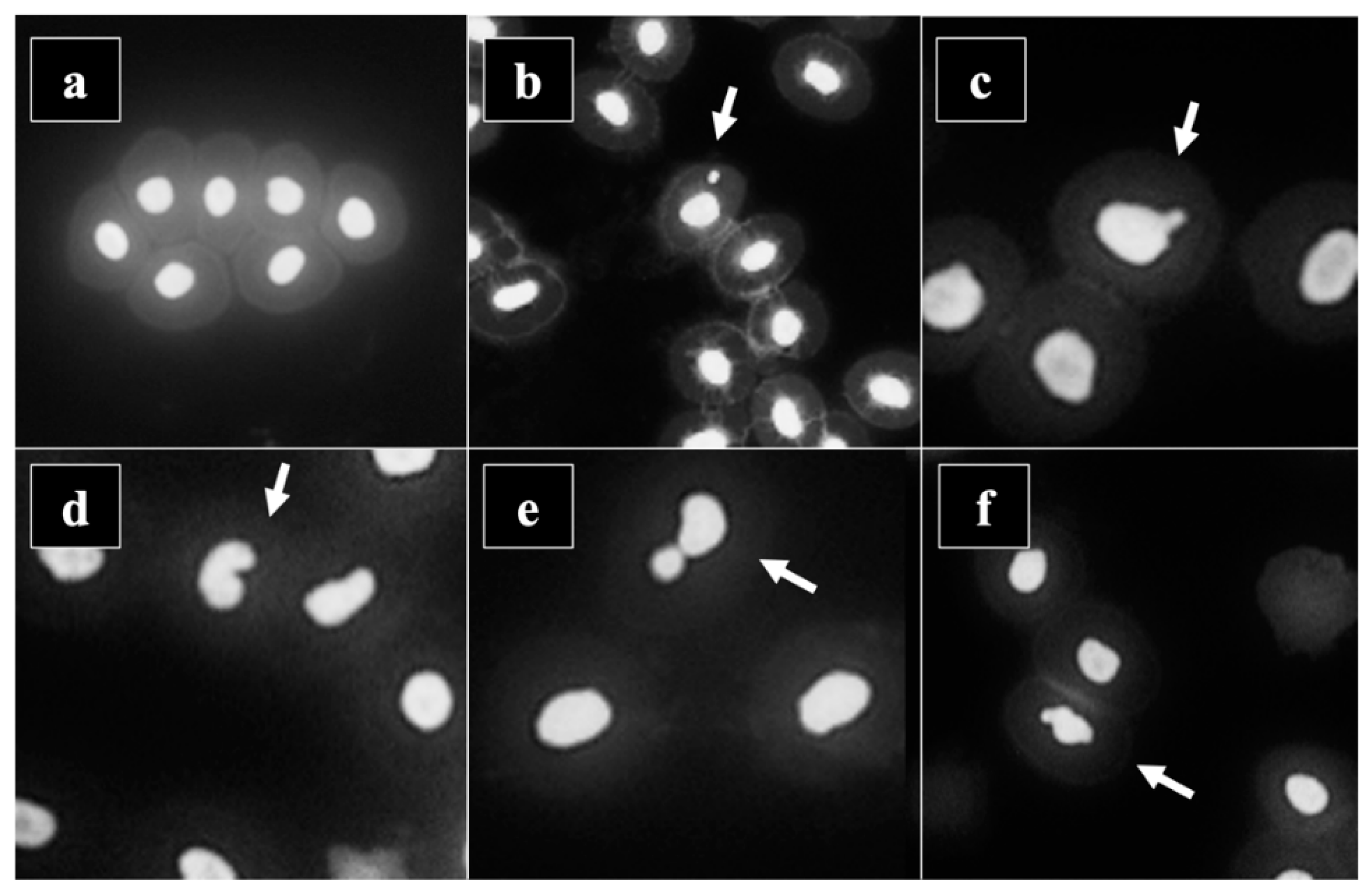

3.4. Micronucleus Assay

3.5. Analysis of Micro and Macro Elements in Muscle

3.6. Sediment Analysis

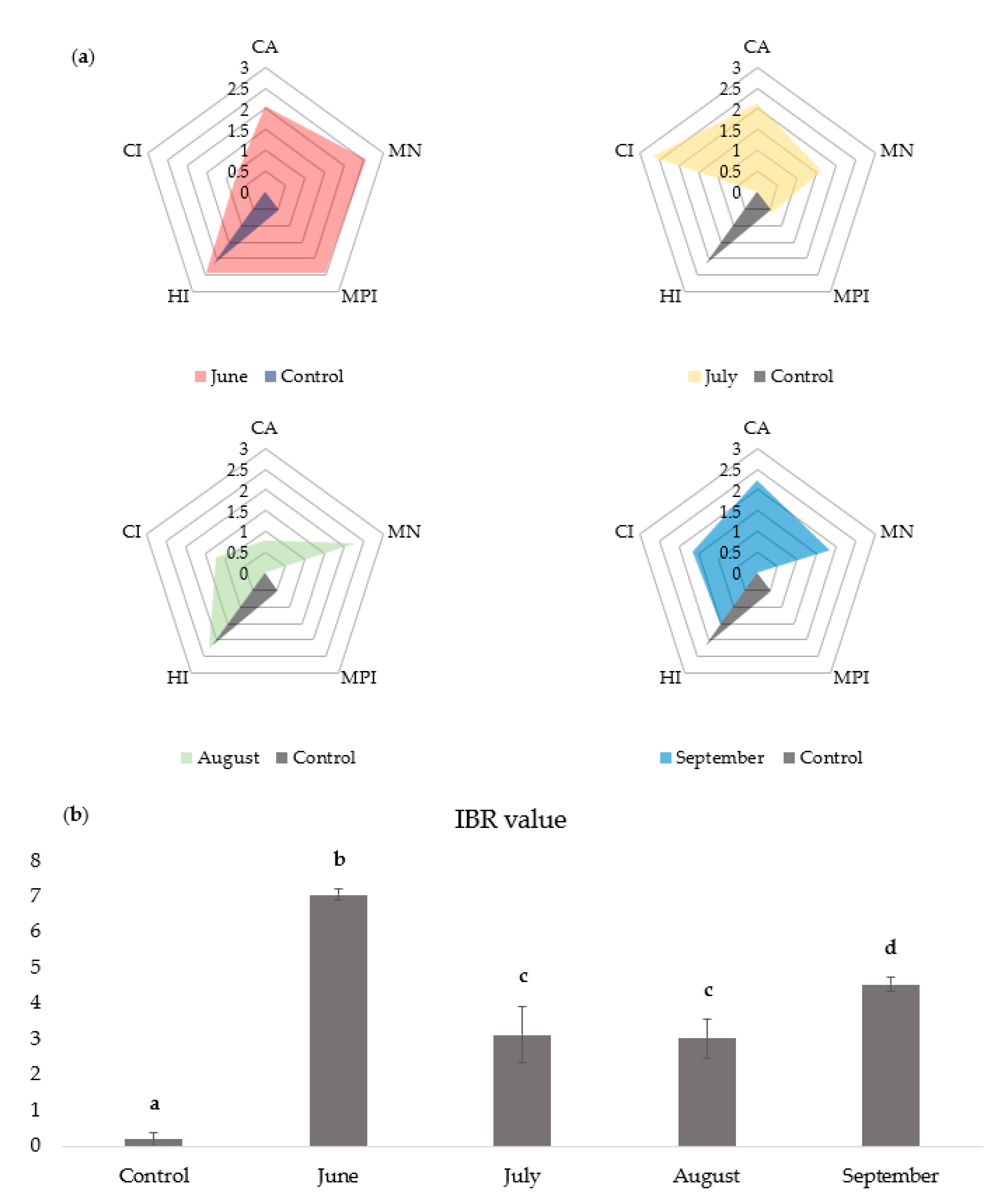

3.7. IBR Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strayer, D.L.; Dudgeon, D. Freshwater biodiversity conservation: Recent progress and future challenges. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2010, 29, 344–358. Doi:10.1899/08-171.1. [CrossRef]

- Koehnken, L.; Rintoul, M.S.; Goichot, M.; Tickner, D.; Loftus, A.C.; Acreman, M.C. Impacts of riverine sand mining on freshwater ecosystems: A review of the scientific evidence and guidance for future research. River Res. Appl. 2020, 36(3), 362-370. Doi:10.1002/rra.3586. [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; Kinzig, A.P.; Daily, G.C.; Loreau, M.; Grace, J.B.; Larigauderie, A.; Srivastava, D.S.; Naeem, S. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486(7401), 59-67. Doi: 10.1038/nature11148. [CrossRef]

- Darwall, W.R.T.; Freyhof, J. Lost fishes, who is counting? The extent of the threat to freshwater fish biodiversity. In Conservation of Freshwater Fishes, 1st ed.; Closs, G.P., Krkosek, M., Olden, J.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, Kingdom of England, 2016; pp. 1–36.

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Dirzo, R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114(30), E6089-E6096. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704949114. [CrossRef]

- Genovesi, P.; Shine, C. European strategy on invasive alien species: Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Habitats (Bern Convention) (No. 18-137). Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2004.

- Van der Veer, G.; Nentwig, W. Environmental and economic impact assessment of alien and invasive fish species in Europe using the generic impact scoring system. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2015, 24(4), 646-656. Doi:10.1111/eff.12181. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.J.; Midgley, G.F.; Archer, E.R.; Arneth, A.; Barnes, D.K.; Chan, L.; Hashimoto, S.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Insarov, G.; Leadley, P.; Levin, L.A.; Ngo, H.T.; Pandit, R.; Pires, A.P.F.; Pörtner, H.O.; Rogers, A.D.; Scholes, R.J.; Settele, J.; Smith, P. Actions to halt biodiversity loss generally benefit the climate. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28(9), 2846-2874. Doi: 10.1111/gcb.16109. [CrossRef]

- Rafinesque, C.S. Description of the Silures or catfishes of the River Ohio. Quart. J. Sci. Lit. Arts 1820, 9, 48-52.

- Nowak, M.; Koščo, J.; Popek, W.; Epler, P. First record of the black bullhead Ameiurus melas (Teleostei: Ictaluridae) in Poland. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 76(6), 1529-1532. Doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02601.x. [CrossRef]

- Cvijanović, G.; Lenhardt, M.B.; Hegediš. The first record of black bullhead Ameiurus melas (Pisces, Ictaluridae) in Serbian waters. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2005, 57(4), 307-308. Doi:10.2298/ABS0504307C. [CrossRef]

- Leunda, P.M.; Oscoz, J.; Elvira, B.; Agorreta, A.; Perea, S.; Miranda, R. Feeding habits of the exotic black bullhead Ameiurus melas (Rafinesque) in the Iberian Peninsula: first evidence of direct predation on native fish species. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73(1), 96-114. Doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.01908.x. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.; Elvira, B.; Collares-Pereira, M.J.; Moyle, P.B. Life-history traits of non-native fishes in Iberian watersheds across several invasion stages: a first approach. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 89-102. Doi: 10.1007/s10530-007-9112-2. [CrossRef]

- Pedicillo, G.; Bicchi, A.; Angeli, V.; Carosi, A.; Viali, P.; Lorenzoni, M. Growth of black bullhead Ameiurus melas (Rafinesque, 1820) in Corbara Reservoir (Umbria–Italy). Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2008, (389), 05 p1-15. Doi: 10.1051/kmae/2008011. [CrossRef]

- Novomeská, A.; Kováč, V. Life-history traits of non-native black bullhead Ameiurus melas with comments on its invasive potential. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2009, 25(1), 79-84. Doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2008.01166.x. [CrossRef]

- Jaćimović, M. Populaciona dinamika i ekotoksikologija crnog americkog patuljastog soma (Ameiurus melas Rafinesque, 1820) u Savskom jezeru [Population dynamic and ecotoxicology of the black bullhead (Ameiurus melas Rafinesque, 1820) in Sava Lake]. Doctoral dissertation, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. http://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/ handle/123456789/5170 [In Serbian].

- Jarić, I.; Jaćimović, M.; Cvijanović, G.; Knežević-Jarić, J.; Lenhardt, M. Demographic flexibility influences colonization success: profiling invasive fish species in the Danube River by the use of population models. Biol. Invasions. 2015, 17, 219-229. Doi: 10.1007/s10530-014-0721-2. [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Tarkan, A.S.; Masson, G.; Godard, M.J.; Koščo, J.; Kováč, V.; Novomeská, A.; Miranda, R.; Cucherousset, J.; Pedicillo, G.; Blackwell, B.G. A review of growth and life-history traits of native and non-native European populations of black bullhead Ameiurus melas. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2016, 26, 441-469. Doi: 10.1007/s11160-016-9436-z. [CrossRef]

- Jaćimović, M.; Lenhardt, M.; Krpo-Ćetković, J.; Jarić, I.; Gačić, Z.; Hegediš, A. Boom-bust like dynamics of invasive black bullhead (Ameiurus melas) in Lake Sava (Serbia). Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2019, 26, 153–164. Doi: 10.1111/fme.12335. [CrossRef]

- Kennard, M.J.; Arthington, A.H.; Pusey, B.J.; Harch, B.D. Are alien fish a reliable indicator of river health?. Freshw. Biol. 2005, 50(1), 174-193. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01293.x. [CrossRef]

- Koutsikos, N.; Koi, A.M.; Zeri, C.; Tsangaris, C.; Dimitriou, E.; Kalantzi, O.I. Exploring microplastic pollution in a Mediterranean river: The role of introduced species as bioindicators. Heliyon 2023, 9(4). Doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15069. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. Emerging alien species in Indian aquaculture: prospects and threats. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2014, 2(1) 2014, 32-41.

- Sicuro, B.; Tarantola, M.; Valle, E. Italian aquaculture and the diffusion of alien species: costs and benefits. Aquac. Res. 2016, (47)12, 3718-3728. Doi: 10.1111/are.12997. [CrossRef]

- Gajski, G.; Žegura, B.; Ladeira, C.; Novak, M.; Sramkova, M.; Pourrut, B.; Del Bo’, C.; Milić, M.; Bjerve Gutzkow, K.; Costa, S.; Dusinska, M.; Brunborg, G.; Collins, A. The comet assay in animal models: From bugs to whales–(Part 2 Vertebrates). Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019, 781, 130-164. Doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2019.04.002. [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Allemang, A.; Audebert, M.; Chauhan, V.; Dertinger, S.; Hendriks, G., Luijten, M; Marchetti, F.; Minocherhomji, S.; Pfuhler, S.; Roberts, D.J.; Trenz, K.; Yauk, C. L. AOP report: Development of an adverse outcome pathway for oxidative DNA damage leading to mutations and chromosomal aberrations. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2022, 63(3), 118-134. Doi: 10.1002/em.22479. [CrossRef]

- Obiakor, M.O.; Okonkwo, J.C.; Ezeonyejiaku, C.D. Genotoxicity of freshwater ecosystem shows DNA damage in preponderant fish as validated by in vivo micronucleus induction in gill and kidney erythrocytes. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen 2014, 775, 20-30. Doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2014.09.010. [CrossRef]

- Carrola, J.; Santos, N.; Rocha, M.J.; Fontainhas-Fernandes, A.; Pardal, M.A.; Monteiro, R.A.; Rocha, E. Frequency of micronuclei and of other nuclear abnormalities in erythrocytes of the grey mullet from the Mondego, Douro and Ave estuaries—Portugal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 6057-6068. Doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2537-0. [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.R.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, C.F.; Chuang, X.Y.; Dong, C. D. Assessment of heavy metals in aquaculture fishes collected from southwest coast of Taiwan and human consumption risk. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 124, 314-325. Doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.04.003. [CrossRef]

- Subotić, S.; Spasić, S.; Višnjić-Jeftić, Ž.; Hegediš, A.; Krpo-Ćetković, J.; Mićković, B.; Skorić, S.; Lenhardt, M. Heavy metal and trace element bioaccumulation in target tissues of four edible fish species from the Danube River (Serbia). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 98, 196-202. Doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.08.020. [CrossRef]

- Kalipci, E.; Cüce, H.; Ustaoğlu, F.; Ali Dereli, M.; Türkmen, M. (2023). Toxicological health risk analysis of hazardous trace elements accumulation in the edible fish species of the Black Sea in Türkiye using multivariate statistical and spatial assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 97, 104028. Doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2022.104028. [CrossRef]

- Risk Assessment Guideline for Superfund Volume 1 Human Evaluation Manual (Part A); Office of Emergency and Remedial Response, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Kruć-Fijałkowska, R.; Dragon, K.; Drożdżyński, D.; Górski, J. Seasonal variation of pesticides in surface water and drinking water wells in the annual cycle in western Poland, and potential health risk assessment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), 3317. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07385-z. [CrossRef]

- 74/2011; Regulation on the parameters of ecological and chemical status of surface waters and the parameters of the chemical and quantitative status of groundwater. Official Gazette of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011.

- ISO 9308-2:2012. Water Quality—Enumeration of Escherichia coli and Coliform Bacteria—Part 2: Most Probable Number Method; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Kavka, G.G.; Kasimir, D.G.; Farnleitner, A.H. (2006). Microbiological water quality of the River Danube (km 2581 - km 15): Longitudinal variation of pollution as determined by standard parameters. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference of IAD (pp. 415–421). Austrian Committee Danube Research / IAD, Vienna, Austria, 04-08/09/2006.

- Kirschner, A.K.; Kavka, G.G.; Velimirov, B.; Mach, R.L.; Sommer, R.; Farnleitner, A.H. Microbiological water quality along the Danube River: integrating data from two whole-river surveys and a transnational monitoring network. Water Res. 2009, 43(15), 3673-3684. Doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.05.034. [CrossRef]

- Ricker, W.E. Computation and interpretation of biological statistics of fish populations. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 191: Ottawa, Canada, 1975., 191, 1-382.

- Kostić, J.; Kolarević, S.; Kračun-Kolarević, M.; Aborgiba, M.; Gačić, Z.; Lenhardt, M.; Vuković-Gačić, B. Genotoxicity assessment of the Danube River using tissues of freshwater bream (Abramis brama). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 20783-20795. Doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7213-0. [CrossRef]

- Boutet-Robinet, E.; Haykal, M.M.; Hashim, S.; Frisan, T.; Martin, O.C. Detection of DNA damage by alkaline comet assay in mouse colonic mucosa. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2(4), 100872. Doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100872. [CrossRef]

- Janković, S.; Antonijević, B.; Ćurčić, M.; Radičević, T.; Stefanović, S.; Nikolić, D.; Ćupić, V. Assessment of mercury intake аssociated with fish consumption in Serbia. Meat Technol. 2012, 53(1), 56-61. Doi:10.5937/tehmesa1201056J. [CrossRef]

- Copat, C.; Arena, G.; Fiore, M.; Ledda, C.; Fallico, R.; Sciacca, S.; Ferrant, M. Heavy metals concentrations in fish and shellfish from eastern Mediterranean Sea: Consumption advisories. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 53 (2013), 33–37. Doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.038. [CrossRef]

- Milošković, A.; Milošević, Đ.; Radojković, N.; Radenković, M.; Đuretanović, S.; Veličković, T.; Simić, V. Potentially toxic elements in freshwater (Alburnus spp.) and marine (Sardina pilchardus) sardines from the Western Balkan Peninsula: An assessment of human health risk and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644(2018), 899-906. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.041. [CrossRef]

- Varol, M.; Sünbül, M.R. Macroelements and toxic trace elements in muscle and liver of fish species from the largest three reservoirs in Turkey and human risk assessment based on the worst-case scenarios. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109298. Doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109298. [CrossRef]

- Usero, J.; Gonzalez-Regalado, E.; Gracia, I. Trace metals in the bivalve molluscs Ruditapes decussatus and Ruditapes philippinarum from the Atlantic Coast of Southern Spain. Environ. Int. 1997, 23(3), 291-298. Doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(97)00030-5. [CrossRef]

- 1881/2006/EC; Setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union, European Commission Regulation: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- 29/2014, 37/2014 - corr., 39/2014 and 72/2014; Rules on the maximum allowable residues of pesticides in food and animal feed which is determined by the maximum allowable amounts of residues of plant protection products. Official Gazette of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014.

- FAO Fishery Circular No. 464; Compilation of legal limits for hazardous substances in fish and fishery products. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 2000 ; pp. 5-10.

- Mazza, F.C.; de Souza Sampaio, N.A.; von Mühlen, C. Hyperspeed method for analyzing organochloride pesticides in sediments using two-dimensional gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415(13), 2629-2640. Doi: 10.1007/s00216-022-04464-y. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, W.; Burgeot, T.; Porcher, J.M. A novel “Integrated Biomarker Response” calculation based on reference deviation concept. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2721-2725. Doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1359-1. [CrossRef]

- SANTE/12682/2019; Analytical Quality Control and Method Validation for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed. European Commission Directorate General for Health and Food Safety: Brussel, Belgium, 2019.

- Hewitt, C.L.; Campbell, M.L.; Gollasch, S. Alien species in aquaculture. Considerations for responsible use. IUCN The World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 1-46.

- Katsanevakis, S.; Rilov, G.; Edelist, D. (2018). Impacts of marine invasive alien species on European fisheries and aquaculture - plague or boon? In CIESM Monograph 50 - Engaging marine scientists and fishers to share knowledge and perceptions - early lessons; Briand, F., Ed.; CIESM Publisher: Monaco, Principality of Monaco, 2018; pp. 125–132.

- Skorupski, J.; Śmietana, P.; Stefánsson, R.A.; von Schmalensee, M.; Panicz, R.; Nędzarek, A.; Eljasik, P.; Szenejko, M. Potential of invasive alien top predator as a biomonitor of nickel deposition–the case of American mink in Iceland. Eur. Zool. J. 2021, 88(1), 142-151. Doi: 10.1080/24750263.2020.1853264. [CrossRef]

- Nekrasova, O.; Pupins, M.; Tytar, V.; Fedorenko, L.; Potrokhov, O.; Škute, A.; Čeirāns, A.; Theissinger, K.; Georges, J. Y. Assessing Prospects of Integrating Asian Carp Polyculture in Europe: A Nature-Based Solution under Climate Change? Fishes 2024, 9(4), 148. Doi: 10.3390/fishes9040148. [CrossRef]

- Van der Oost, R.; Beyer, J.; Vermeulen, N.P. Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 13(2), 57-149. Doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(02)00126-6. [CrossRef]

- Rašković, B.; Poleksić, V.; Skorić, S.; Jovičić, K.; Spasić, S.; Hegediš, A.; Vasić, N.; Lenhardt, M. Effects of mine tailing and mixed contamination on metals, trace elements accumulation and histopathology of the chub (Squalius cephalus) tissues: Evidence from three differently contaminated sites in Serbia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 153, 238-247. Doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.01.058. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, D.; Kostić, J.; Đorđević Aleksić, J.; Sunjog, K.; Rašković, B.; Poleksić, V.; Pavlović, S.; Borković-Mitić, S.; Dimitrijević, M.; Stanković, M.; Radotić, K. Effects of mining activities and municipal wastewaters on element accumulation and integrated biomarker responses of the European chub (Squalius cephalus). Chemosphere 2024, 143385. Doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143385. [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.; Fazekas, D.L.; Halasi-Kovács, B.; Józsa, V.; Tóth, F.; Nyeste, K.; Mozsár, A. Fecundity, growth and body condition of invasive black bullhead (Ameiurus melas) in eutrophic oxbow lakes of River-Körös (Hungary). Bioinvasions Rec. 2024, 13(2), 515–527. Doi: 10.3391/bir.2024.13.2.16. [CrossRef]

- Lacaze, E.; Geffard, O.; Goyet, D.; Bony, S.; Devaux, A. Linking genotoxic responses in Gammarus fossarum germ cells with reproduction impairment, using the Comet assay. Environ. Res. 2011, 111(5), 626-634. Doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.03.012. [CrossRef]

- Pandrangi, R.; Petras, M.; Ralph, S.; Vrzoc, M. Alkaline single cell gel (comet) assay and genotoxicity monitoring using bullheads and carp. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1995, 26(4), 345-356. Doi: 10.1002/em.2850260411. [CrossRef]

- Arcand-Hoy, L.D.; Metcalfe, C.D. Hepatic micronuclei in brown bullheads (Ameiurus nebulosus) as a biomarker for exposure to genotoxic chemicals. J. Great Lakes Res. 2000, 26(4), 408-415. Doi: 10.1016/S0380-1330(00)70704-0. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meier, J.; Chang, L.; Rowan, M.; Baumann, P.C. DNA damage and external lesions in brown bullheads (Ameiurus nebulosus) from contaminated habitats. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25(11), 3035-3038. Doi: 10.1897/05-706R.1. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P.C.; LeBlanc, D.R.; Blazer, V.; Meier, J.R.; Hurley, S.T.; Kiryu, Y. Prevalence of tumors in brown bullhead from three lakes in Southeastern Massachusetts, 2002. Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5198. U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, United States, 2008. Doi: 10.3133/sir20085198. [CrossRef]

- Pinkney, A.E.; Harshbarger, J.C.; Karouna-Renier, N.K.; Jenko, K.; Balk, L.; Skarphéðinsdóttir, H.; Liewenborg, B.; Rutter, M.A. Tumor prevalence and biomarkers of genotoxicity in brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) in Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 410, 248-257. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.035. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Shen, W.; Xu, C.; Di, S.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Synergistic effect of fenpropathrin and paclobutrazol on early life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115067. Doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115067. [CrossRef]

- Naz, H.; Abdullah, S.; Abbas, K.; Shafique, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, P. Comparative study: antioxidant enzymes, DNA damage and nuclear abnormalities in three fish species Cirrhina mrigala, Catla catla and Labeo rohita exposed to insecticides mixture (endosulfan+ chlorpyrifos+ bifenthrine). Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 59(2), 295-301. Doi: 10.17582/journal.pjz/20220429100432. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wainwright, H.; Moore, K.G. Effects of orchard application of paclobutrazol on the post-harvest ripening of apples. J. Hortic. Sci. 1987, 62(3), 295-301. Doi: 10.1080/14620316.1987.11515784. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.D.; Wu, C.Y.; Lonameo, B.K. Toxic effects of paclobutrazol on developing organs at different exposure times in Zebrafish. Toxics 2019, 7(4), 62. Doi: 10.3390/toxics7040062. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Audira, G.; Siregar, P.; Lin, Y.C.; Villalobos, O.; Villaflores, O.; Wang, W.D.; Hsiao, C.D. Waterborne exposure of paclobutrazol at environmental relevant concentration induce locomotion hyperactivity in larvae and anxiolytic exploratory behavior in adult zebrafish. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(13), 4632. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134632. [CrossRef]

- Soderlund, D.M.; Clark, J.M.; Sheets, L.P.; Mullin, L.S.; Piccirillo, V.J.; Sargent, D.; Stevens, J.T.; Weiner, M.L. Mechanisms of pyrethroid neurotoxicity: implications for cumulative risk assessment. Toxicology 2002, 171(1), 3-59. Doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00569-8. [CrossRef]

- Napierska, D.; Sanseverino, I.; Loos, R.; Cortés, L.G.; Niegowska, M.; Lettieri, T. Modes of action of the current Priority Substances list under the Water Framework Directive and other substances of interest. EUR 29008 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018. Doi:10.2760/226911. [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, S.; Holm, S. Hazard assessment of the synthetic pyrethroid insecticides bifenthrin, cypermethrin, esfenvalerate, and permethrin to aquatic organisms in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River system. Office of Spill Prevention and Response 00-6. Administrative Report. California Department of Fish and Game, Rancho Cordova, CA, USA, 2000.

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance bifenthrin. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2159. Doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2159. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, G.; Tabinda, A.B.; Kashif, M.; Yasar, A.; Mahmood, A.; Rasheed, R.; Khan, M.I.; Iqbal, J.; Siddique, S.; Mahfooz, Y. Monitoring and spatiotemporal variations of pyrethroid insecticides in surface water, sediment, and fish of the river Chenab Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 22584-22597. Doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1963-9. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, S.; Altaf, Y.; Dawar, F.U.; Anjum, S.I.; Baig, M.M.F.A.; Fahad, S.; Al-Misned, F.; Atique, U.; Guo, X.; Nabi, G.; Wanghe, K. Bifenthrin induced toxicity in Ctenopharyngodon idella at an acute concentration: a multi-biomarkers-based study. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34(2), 101752. Doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101752. [CrossRef]

- Mokry, L.E.; Hoagland, K.D. Acute toxicities of five synthetic pyrethroid insecticides to Daphnia magna and Ceriodaphnia dubia. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1990, 9(8), 1045-1051. Doi: 10.1002/etc.5620090811. [CrossRef]

- Padilla, S.; Corum, D.; Padnos, B.; Hunter, D.L.; Beam, A.; Houck, K.A.; Sipes, N.; Kleinstreuer, N.; Knudsen, T.; Dix, D.J.; Reif, D.M. Zebrafish developmental screening of the ToxCast™ Phase I chemical library. Reprod. Toxicol. 2012, 33(2), 174-187 Doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.10.018. [CrossRef]

- Marinowic, D.R.; Mergener, M.; Pollo, T.A.; Maluf, S.W.; da Silva, L.B. In vivo genotoxicity of the pyrethroid pesticide β-cyfluthrin using the comet assay in the fish Bryconamericus iheringii. Z. Naturforsch. C 2012, 67(5-6), 308-311. Doi: 10.1515/znc-2012-5-610. [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.; Curchod, L.; Davies, E.; Veludo, A.F.; Oltramare, C.; Dalvie, M.A.; Stamm, C.; Röösli, M.; Fuhrimann, S. Seasonal drivers and risks of aquatic pesticide pollution in drought and post-drought conditions in three Mediterranean watersheds. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159784. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159784. [CrossRef]

- Ayllon, F.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Micronuclei and other nuclear lesions as genotoxicity indicators in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2001, 49(3), 221-225. Doi: 10.1006/eesa.2001.2065. [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, A.A.; Seriani, R.; Pereira, C.D.; Assunção, A.; Abessa, D.M.D.S.; Rotundo, M.M.; Rahossnzani-Paiva, M.J. Cytogenotoxicity biomarkers in fat snook Centropomus parallelus from Cananéia and São Vicente estuaries, SP, Brazil. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2009, 32(1), 151-154. Doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009005000007. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.R.; Pruski, A.M.; Dixon, L.R.; Jha, A.N. Marine invertebrate eco-genotoxicology: a methodological overview. Mutagenesis 2002, 17(6), 495-507. Doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.6.495.

- Çavaş, T.; Ergene-Gözükara, S. Micronuclei, nuclear lesions and interphase silver-stained nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) as cyto-genotoxicity indicators in Oreochromis niloticus exposed to textile mill effluent. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2003, 538(1-2), 81-91. Doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(03)00091-3. [CrossRef]

- Baršienė, J.; Rybakovas, A.; Lang, T.; Andreikėnaitė, L.; Michailovas, A. Environmental genotoxicity and cytotoxicity levels in fish from the North Sea offshore region and Atlantic coastal waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 68(1-2), 106-116. Doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.12.011. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Sultana, T.; Sultana, S.; Masoud, M.S.; Ahmed, Z.; Mahboob, S. Fish eco-genotoxicology: Comet and micronucleus assay in fish erythrocytes as in situ biomarker of freshwater pollution. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25(2), 393-398. Doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.11.048. [CrossRef]

- Campana, M.A.; Panzeri, A.M.; Moreno, V.J.; Dulout, F.N. Genotoxic evaluation of the pyrethroid lambda-cyhalothrin using the micronucleus test in erythrocytes of the fish Cheirodon interruptus interruptus. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 1999, 438(2), 155-161. Doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00167-3. [CrossRef]

- Muranli, F.D.G.; Güner, U. Induction of micronuclei and nuclear abnormalities in erythrocytes of mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) following exposure to the pyrethroid insecticide lambda-cyhalothrin. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2011, 726(2), 104-108. Doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Luzhna, L.; Kathiria, P.; Kovalchuk, O. Micronuclei in genotoxicity assessment: from genetics to epigenetics and beyond. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 131. Doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00131. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabti, K.; Metcalfe, C. D. Fish micronuclei for assessing genotoxicity in water. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. 1995, 343(2-3), 121-135. Doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(95)90078-0. [CrossRef]

- Udroiu, I. The micronucleus test in piscine erythrocytes. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 79(2), 201-204. Doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.06.013. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Tanjin, F.; Rahman, M.S.; Yu, J.; Akhter, S.; Noman, M.A; Sun, J. Metals Bioaccumulation in 15 Commonly Consumed Fishes from the Lower Meghna River and Adjacent Areas of Bangladesh and Associated Human Health Hazards. Toxics 2022, 10(3), 139. Doi:10.3390/toxics10030139. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jayachandran, M.; Bai, W.; Xu, B. A critical review on the health benefits of fish consumption and its bioactive constituents. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130874. Doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130874. [CrossRef]

- Isangedighi, I.A.; David, G.S. Heavy Metals Contamination in Fish: Effects on Human Health. J. Aquat. Sci. Mar. Biol. 2019, 2(4), 7-12. Doi:10.22259/2638-5481.0204002. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, D.; Skorić, S.; Lenhardt, M.; Hegediš, A.; Krpo-Ćetković, J. Risk assessment of using fish from different types of reservoirs as human food–A study on European perch (Perca fluviatilis). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113586. Doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113586. [CrossRef]

- Fallah, A.A.; Saei-Dehkordi, S.S.; Nematollahi, A.; Jafari, T. Comparative study of heavy metal and trace element accumulation in edible tissues of farmed and wild rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) using ICP-OES technique. Microchem. J. 2011, 98(2), 275-279. Doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2011.02.007. [CrossRef]

- Kalantzi, I.; Shimmield, T.M.; Pergantis, S.A.; Papageorgiou, N.; Black, K.D.; Karakassis, I. Heavy metals, trace elements and sediment geochemistry at four Mediterranean fish farms. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 128-137. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.082. [CrossRef]

- Umirah Idris, N.S.; Yaakub, N; Abdul Halim, N.S. Assessment of metal distribution in various tissues of wild-caught and cultured Pangasius sp. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020, 15, 40-48. Doi: 10.46754/jssm.2020.10.005. [CrossRef]

- Andreji, J.; Stránai, I.; Massányi, P.; Valent, M. Concentration of selected metals in muscle of various fish species. J. Environ. Sci. Health 2005, 40(4), 899-912. Doi: 10.1081/ese-200048297. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Sasina, N.V.; Kryshev, A.I.; Belova, N.V.; Kudelsky, A.V. A review and test of predictive models for the bioaccumulation of radiostrontium in fish. J. Environ. Radioact. 2009, 100, 950-954. Doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2009.07.005. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah Alnuwaiser, M. An analytical survey of trace heavy elements in insecticides. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 2019(1), 8150793. Doi: 10.1155/2019/8150793. [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Kumar, A.; Nayak, A.K.; Shahid, M.; Tripathi, R.; Vijayakumar, S.; Bhaduri, D.; Kumar, U.; Mohanty, S.; Panneerselvam, P.; Chatterjee, D.; Satapathy, B.S.; Pathak, H. Metal (loid) s (As, Hg, Se, Pb and Cd) in paddy soil: Bioavailability and potential risk to human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134330. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134330. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13(6), 1521. Doi: 10.3390/agronomy13061521. [CrossRef]

- Defarge, N.; De Vendômois, J.S.; Séralini, G.E. Toxicity of formulants and heavy metals in glyphosate-based herbicides and other pesticides. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 156-163. Doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.12.025. [CrossRef]

- Beliaeff, B.; Burgeot, T. Integrated biomarker response: a useful tool for ecological risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21(6), 1316-1322. Doi: 10.1002/etc.5620210629. [CrossRef]

- Kolarević, S.; Aborgiba, M.; Kračun-Kolarević, M.; Kostić, J.; Simonović, P.; Simić, V.; Milošković, A.; Reischer, G.; Farnleitner, A.; Gačić, Z.; Milačič, R.; Zuliani, T.; Vidmar, J.; Pergal, M.; Piria, M.; Paunović, M.; Vuković-Gačić, B. Evaluation of genotoxic pressure along the Sava River. PloS one 2016, 11(9), e0162450. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162450. [CrossRef]

| June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | 21.7 | 25.8 | 23.5 | 19.7 |

| pH | 8.17 | 7.91 | 8.42 | 8.93 |

| O2 (mg/L) | 6.84 | 2.57 | 5.40 | 6.77 |

| O2 (%) | 77.5 | 32.3 | 63.0 | 74.4 |

| Conductivity (μS/cm) | 357 | 409 | 306 | 288 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 0.247 | 0.261 | 0.205 | 0.208 |

| NO2- (mg/L) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| NO3- (mg/L) | 1.26 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| NH4+ (mg/L) | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| TC MPN/100 mL | 763 | 381.5 | 2442 | >12098 |

| EC MPN/100 mL | 20 | 10 | 43 | 10 |

| Control | June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 25.2±1.1 | 13.6± 1.5 | 13.5±1.5 | 14.5±1.6 | 16.0±1.0 |

| W | 226.9±45.3 | 34.7± 11.2 | 30.2±8.7 | 41.2±11.8 | 53.5±10.8 |

| K | 1.4±0.1 | 1.4±0.3 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 |

| Control | June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN* | 0.15±0,34a | 1.30±0.89b | 0.60±0.61ab | 1.08±0.87b | 0.70±0.42b |

| BUD** | 0.55±0.44ab | 0.85±0.71b | 0.33±0.24a | 0.75±0.54ab | 0.90±0.61b |

| NOTCHED** | 0.90±0.61a | 0.10±0.21b | 0.25±0.63ab | 0.20±0.48b | 0.23±0.25b |

| BI** | 0±0a | 0.15±0.34ab | 0.20±0.26b | 0.43±0.44b | 0.55±0.72b |

| IRR** | 0.05±0.16 | 0.40±0.61 | 0.20±0.35 | 0.10±0.21 | 0.25±0.49 |

| Control | June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 12.61±18.32 | 34.05±18.53 | 8.93±12.41 | 15.50±29.27 | 12.81±29.12 |

| Ba | 2.18±1.14 | 5.15±1.08* | 2.97±2.34 | 2.18±0.99 | 3.30±1.74 |

| Cd | 0.01±0.02 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.08±0.02* | 0.04±0.02 | 0.05±0.02 |

| Cr | 0.42±0.21 | 0.59±0.28 | 0.37±0.07 | 0.34±0.12 | 0.39±0.11 |

| Co | 0.17±0.06 | 0.19±0.09 | 0.11±0.06 | 0.11±0.07 | 0.09±0.07* |

| Cu | 1.82±0.37 | 4.79±1.50* | 0.40±0.34 | 2.19±0.35 | 1.87±0.40 |

| Pb | 0.60±0.19 | 0.40±0.12* | 0.41±0.17* | 0.70±0.23 | 0.58±0.14 |

| Li | 0.04±0.03 | 0.34±0.08* | 0.07±0.03 | 0.04±0.03 | 0.60±0.05 |

| Se | 0.71±0.48 | 0.42±0.31 | 0.73±0.25 | 0.53±0.35 | 0.86±0.32 |

| Pt | 0.27±0.13 | 0.25±0.15 | 0.24±0.16 | 0.25±0.05 | 0.22±0.11 |

| Ti | 0.31±0.43 | 0.79±0.55 | 0.28±0.32 | 0.31±0.66 | 0.16±0.25 |

| Sr | 2.93±2.69 | 11.77±5.53* | 5.23±3.76 | 3.75±3.54 | 6.67±6.25* |

| Fe | 33.03±22.24 | 48.63±30.84 | 33.22±17.93 | 34.32±24.92 | 30.45±17.65 |

| Zn | 124.45±28.82 | 204.98±33.45* | 124.00±32.24 | 109.04±24.54 | 123.22±40.58 |

| Mn | 3.54±2.43 | 5.53±5.93 | 11.42±2.08* | 7.83±4.97* | 6.28±1.86 |

| Ni | 4.97±2.39 | 8.93±7.03 | 13.97±2.21* | 10.79±4.71* | 8.82±1.85* |

| Control | June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al THQ | 0.433 | 0.408 | 0.280 | 0.451 | 0.417 |

| Cd THQ | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| Co THQ | 0.077 | 0.074 | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.036 |

| Cu THQ | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| Pb THQ | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Fe THQ | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| Zn THQ | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| Mn THQ | - | - | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Ni THQ | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.085 | 0.061 | 0.055 |

| HI | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.53 |

| MPI | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).