Introduction

G-CSFs play a crucial role in the mobilization of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) and the apheresis process. Additionally, these pharmaceutical agents are employed in the management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia among patients with non-myeloid malignancies undergoing myelotoxic chemotherapy, as they enhance the proliferation, maturation, and functional capacity of white blood cells [

1]. Febrile neutropenia (FN) is a common complication associated with chemotherapeutic treatment, underscoring its significance as a critical oncologic emergency. This condition is closely associated with a marked increase in both morbidity and mortality rates, elevated utilization of healthcare resources, and a considerable reduction in the efficacy of chemotherapy regimens [

2]. G-CSF has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing both the duration and severity of neutropenia, thereby decreasing the likelihood of febrile neutropenia. Furthermore, it facilitates the administration of full-dose-dense chemotherapy when clinically indicated [

3,

4,

5]. G-CSF serves as a viable option for primary prophylaxis when the risk of neutropenic fever exceeds 20% with any chemotherapy regimen. Additionally, it may be utilized for secondary prophylaxis or for the management of established neutropenic fever [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Moreover, a limited number of case reports have documented severe complications such as splenic rupture, splenic infarction, myocardial infarction, and stroke that are associated with the administration of colony-stimulating factors in both hematologic and solid tumors. Among individuals experiencing splenic complications, some cases were managed conservatively, while others with more severe complications required splenectomy [

6,

7,

8,

9].

This case study presents a 67-year-old male diagnosed with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), who underwent dose-dense chemotherapy accompanied by a colony-stimulating factor as a primary prophylactic measure to prevent febrile neutropenia. Midway through treatment, the patient developed splenic infarction, as confirmed by a computed tomography (CT) scan. The management of this complication was conducted conservatively, thereby eliminating the need for surgical intervention.

Case Presentation

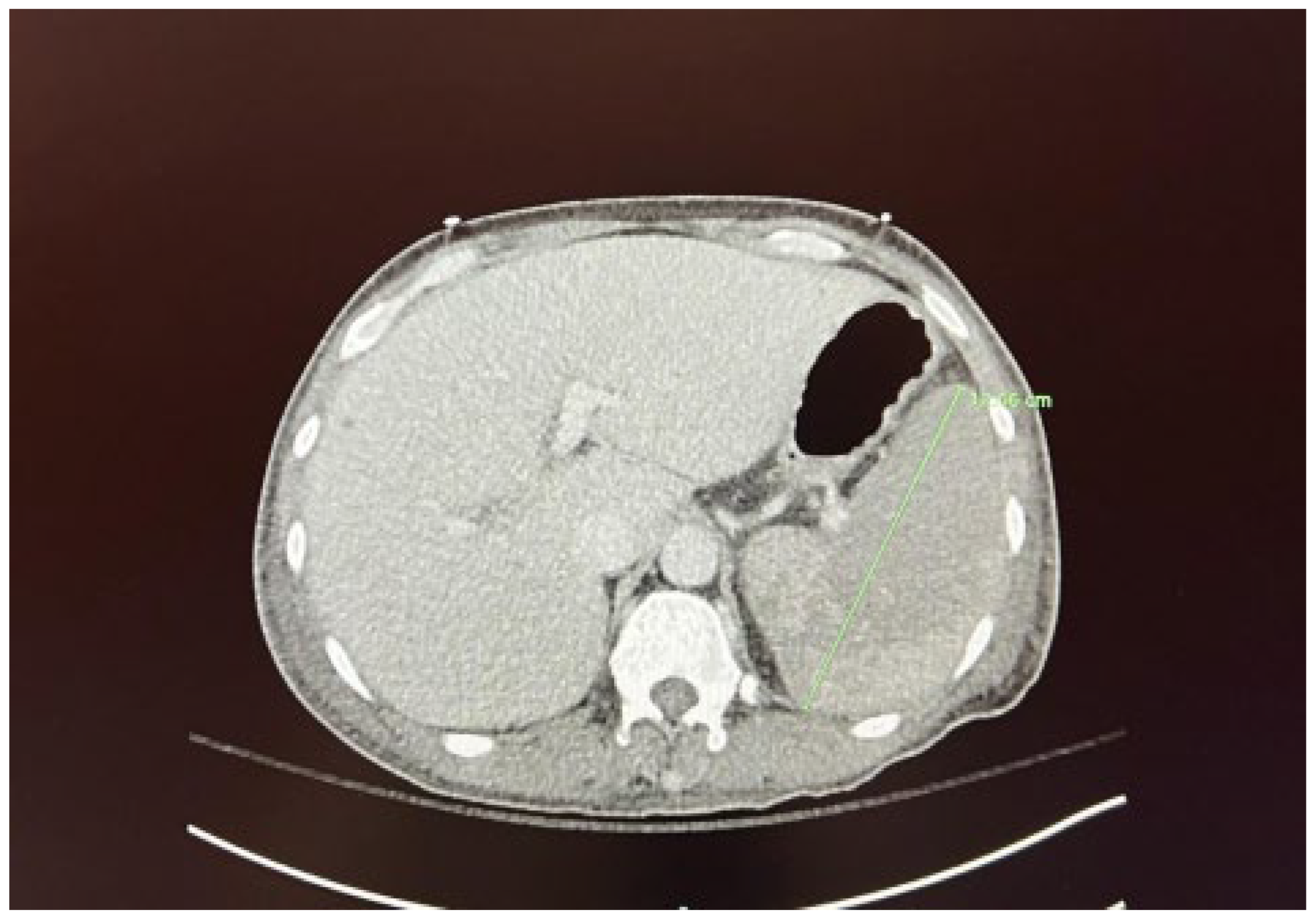

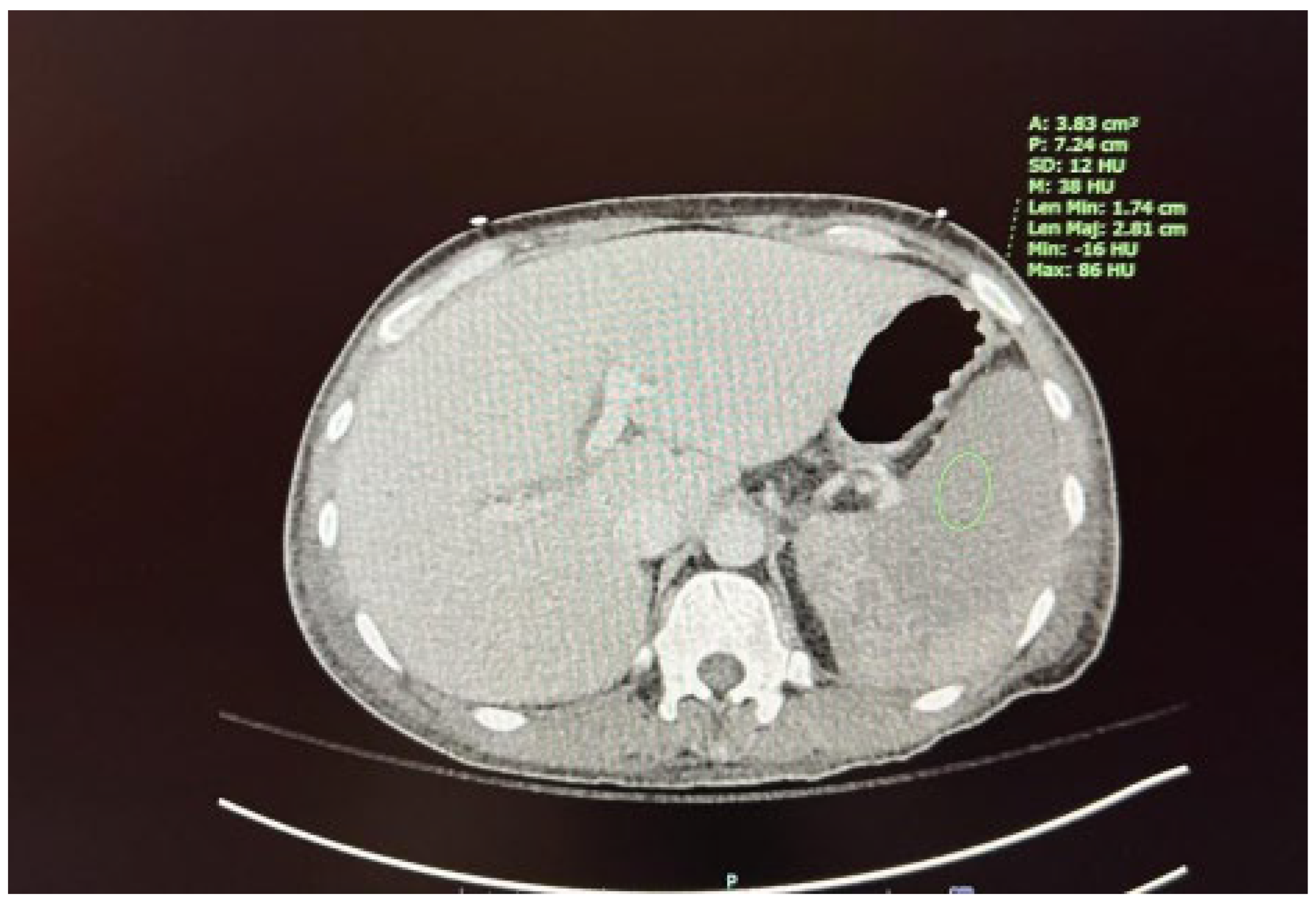

We present the case of a 67-year-old male diagnosed with high-risk chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) in October 2023. The patient presented to the hematology/oncology clinic exhibiting symptoms of malaise, dizziness, chills, tachycardia, and hypotension, which raised concerns about sepsis. Following the administration of 1 liter of intravenous fluids and cefepime, he was subsequently referred to the emergency department. Upon admission to the medicine floor, he underwent evaluation and management for sepsis and lactic acidosis. However, due to persistent hypotension necessitating vasopressor support and elevated lactic acid levels greater than 5 mmol/L, he was transferred to the medical intensive care unit. This admission marked the patient’s fourth instance of neutropenic fever since the initial diagnosis of CMML. His condition was further complicated by a peripheral blast crisis, prompting treatment with azacitidine and venetoclax, as well as the presence of pancytopenia accompanied by leukocytosis (now showing a downtrend) and severe thrombocytopenia, placing him at risk for tumor lysis syndrome. The patient had recently received chemotherapy on April 5, 2024, as well as Neulasta on April 8, 2024, for neutropenic support. He reported experiencing severe abdominal pain, rated at 8 out of 10. A computed tomography (CT) scan conducted on April 10, 2024, discounted the existence of an infectious focus and indicated hepatosplenomegaly, alongside diffuse low-density lesions in the spleen suggestive of a developing splenic infarct and minimal peri-splenic fluid accumulation; however, no active bleeding was detected (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The critical illness of the patient appeared to be associated with the underlying CMML, recent chemotherapy, and complications from treatment, including splenic infarction, potentially attributable to the use of filgrastim.

Discussion

G-CSF is frequently prescribed to cancer patients for the prevention and treatment of febrile neutropenia resulting from myelosuppressive chemotherapy. The prophylactic administration of G-CSF is recommended when the risk of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia exceeds 20%, as this approach aids in maintaining dose density and intensity, which confers a significant survival benefit [

1,

2]. Pegfilgrastim, a long-acting formulation of filgrastim, is one of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factors utilized for this purpose. Its formulation includes a polyethylene glycol molecule, extending its action duration. Pegfilgrastim prevents febrile neutropenia by increasing neutrophil levels by promoting proliferation, differentiation, and maturation of neutrophils, in addition to enhancing the survival of mature neutrophils [

10]. Another clinical scenario in which G-CSF proves beneficial is in the context of healthy donors for peripheral blood stem cell transplant (PBSCT) recipients or in patients undergoing mobilization. While G-CSF administration is generally regarded as effective and relatively safe, it is associated with potential adverse effects, including bone pain and localized skin reactions at the injection site [

2]. Case reports involving both cancer patients receiving G-CSF for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and healthy stem cell donors have recorded instances of splenic infarction and life-threatening rupture [

6,

7]. Given pegfilgrastim’s mechanism of action in preventing febrile neutropenia through its effects on neutrophils, it is imperative to closely monitor the patient’s complete blood count throughout the treatment, particularly emphasizing the white blood cell count [

11]. The maximum safe dosage of pegfilgrastim has yet to be established, with clinical trials permitting doses of up to 300 mcg/kg. Reports of accidental overdoses have emerged, including a case involving a 79-year-old patient who self-administered pegfilgrastim over eight consecutive days without experiencing immediate symptoms, and a 69-year-old patient who ingested a 36 mg overdose, leading to symptoms such as leukocytosis, bone pain, and rhinorrhea. As there is currently no established treatment for pegfilgrastim overdose, preventive measures through vigilant monitoring for signs and symptoms of toxicity are essential [

12].

Conclusion

G-CSFs have revolutionized the management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, which is indispensable in reducing the risk of febrile neutropenia and enabling patients to maintain dose-dense chemotherapy regimens. This case highlights the therapeutic benefits of G-CSF, particularly in high-risk patients like those with CMML. However, it also underscores the potential for severe complications, such as splenic infarction, which, though rare, can occur as a consequence of G-CSF administration.

In this case, the 67-year-old patient developed splenic infarction after receiving filgrastim during his chemotherapy for CMML, illustrating the need for careful monitoring of patients undergoing G-CSF therapy. While conservative management was successful in this case, avoiding the need for surgical intervention, the occurrence of splenic complications signals the importance of vigilance when utilizing G-CSF, especially in patients with predisposing risk factors or comorbidities.

The case also reaffirms the clinical necessity of individualized treatment protocols, where the benefits of G-CSF must be weighed against potential risks, such as splenic complications. Close surveillance of hematologic parameters, particularly white blood cell counts, during G-CSF therapy is crucial to minimizing adverse effects. Moreover, the dose and duration of G-CSF should be carefully managed to prevent overdose, which, although not common, can result in significant toxicity.

In conclusion, while G-CSF remains a cornerstone in preventing chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and febrile neutropenia, clinicians must remain cautious of its rare but serious side effects. This case serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between therapeutic benefit and risk, reinforcing the need for thorough patient monitoring and an individualized approach to cancer treatment.

References

- Tigue CC, McKoy JM, Evens AM, Trifilio SM, Tallman MS, Bennett CL. (2007: Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administration to healthy individuals and persons with chronic neutropenia or cancer: An overview of safety considerations from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports project. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 40:185-92. [CrossRef]

- Smith TJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH (2015: Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 33:3199-212. [CrossRef]

- Möbus V. (2016: Adjuvant dose-dense chemotherapy in breast cancer: Standard of care in high-risk patients. Breast Care. 11:8-12. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Chen S, Xu F, Zeng X. (2018: Survival benefit of pure dose-dense chemotherapy in breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 16:144. [CrossRef]

- Reinisch M, Ataseven B, Kümmel S. (2016: Neoadjuvant dose-dense and dose-intensified chemotherapy in breast cancer: Review of the literature. Breast Care. 11:13-20. [CrossRef]

- Masood N, Shaikh AJ, Memon WA, Idress R. (2008: Splenic rupture secondary to G-CSF use for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: A case report and review of literature. Cases Journal. 1:418. [CrossRef]

- Stroncek D, Shawker T, Follmann D, Leitman SF. (2003: G-CSF-induced spleen size changes in peripheral blood progenitor cell donors. Transfusion. 43:609-13. [CrossRef]

- Raut SS, Shukla SN, Talati SS. (2015: Splenic infarcts following treatment with filgrastim: An unusual complication. International Journal of Medical and Applied Sciences. 4:190-3.

- Watring NJ, Wagner TW, Stark JJ. (2003: Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to pegfilgrastim to prevent neutropenia in a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. The. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 25:247-8. [CrossRef]

- Yang BB, Kido A. (2011: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pegfilgrastim. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 50:295-306. [CrossRef]

- Kosaka Y, Rai Y, Masuda N (2015: Phase III placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of pegfilgrastim to reduce the risk of febrile neutropenia in breast cancer patients receiving docetaxel/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 23:1137-43. [CrossRef]

- Riu G, Estefanell A, Nomdedeu M, Creus N. (2012: Overdose of pegfilgrastim: Case report. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 34:690-2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).