1. Introduction

1.1. Algorithmic Game Theory

Algorithm game theory (AGT) is an area in the intersection of theoretical computer science and economy. It can be divided into three main parts for research: game and equilibrium, mechanism design, and routing network. The biggest difference between algorithmic game theory and other algorithm direction is that, AGT assumes all the agents are rational intelligence. In other words, they will make a choice based on their utility so they may give the wrong information to the central system.

Due to our topic, we only introduce the algorithmic mechanism design area. Here are some famous examples related to mechanism design: elections, markets, auctions, government policy, etc. A mechanism is similar to an algorithm, however, it must consider how to prevent agents from “lying", i.e. giving the wrong information. If it cannot prevent (e.g. the social choice problem with preference sequence instead of value as the input) lying, then this time it may be regarded as a normal algorithm.

Mechanism design can model many different situations in industry and life. As is known to all, the advertisement on Google, and the selling institution on Ebay are both designed based on auction theory. The reason why they use second price auction (i.e. the selling price is the second highest bidding instead of the first) is to get better social utility / welfare, which is a vital conclusion in mechanism design.

1.2. Incentive-Compatible Selection Mechanisms

Incentive-compatible (IC) selection mechanism is an important kind of mechanisms in mechanism design area. It has been studying in many different settings. The motivation for this research stems from many scenarios in which agents approve or disapprove each other, and there is an administrator (also called dictator) required to select one or several agents as the winner or loser. Here are some examples:

1. Select a prize winner in an academic area according to the committee. 2. Select a core node in a social network (the node refers to an agent). 3. Sort different web-pages according to the link from other web-pages.

We can easily notice that, all the agents may have an incentive to misreport their true information (including appreciation, interest, etc), i.e. tell a lie. An incentive-compatible selection mechanism guarantees that an agent’s decision about its submitted information does not affect its utility. A probabilistic selection mechanism assigns each agent a probability. In this paper, we only talk about IC probabilistic selection mechanisms.

We choose to apply this model on a directed forest following Babichenko et al’s work [

1]. A directed forest is an acyclic directed graph with maximum out-degree equal to 1. This model is suitable for such selection mechanisms. The fact that a forest is acyclic guarantees we can define the social utility conveniently. Also the restriction of maximum out-degree greatly reduces the difficulty of analysis.

1.3. Our Result and Technique

We explore the bound of quality for incentive-compatible, fair and exact selection mechanisms respectively. We prove that, for the number of vertices in the forest , the tight bound of quality is 0.8 always holds incentive-compatible, fair and exact mechanisms respectively.

Also, for , there is something different. For incentive-compatible selection mechanisms, we prove that we can achieve a mechanism with quality equal to . Notice that we have an upper bound of 0.8 with the case, so the gap between upper bound and lower bound is very tiny: .

For fair mechanisms with , we prove that we can achieve a mechanism with quality equal to 0.6. This gap of bounds is much larger than incentive-compatible one. And for exact mechanisms with , we prove that the tight bound of quality is .

As for mathematical technique, we use linear inequalities mainly with some basic technique for incentive-compatible mechanisms in algorithm game theory area.

1.4. Related Work

Our work is inspired by Yakov Babichenko et al’s work [

1]. They prove an upper bound of

and a lower bound of

for any IC selection mechanism. Also, they explore the fair and exact mechanisms with several different results.

Based on their result, we studied the specific lower bound of , which is an improvement of their work.

This model is based on the approximation mechanism design without money and here are some representative papers: [

2,

3,

4]. Generally speaking, the goal of this area’s work focuses on offering mechanisms with strategy-proof (i.e. truthful) solutions. Although in most of the cases, this will bring a large loss on the utility compared with the non-strategyproof ones, it is still worth studying.

The most similar model to this selection mechanism on directed forest model is [

5]. In that paper, the authors discuss different IC probabilistic selection mechanisms for trees, forests, and acyclic graphs. However, the ratio in their work is unbounded, i.e. related to

n and may reach infinite with

.

The work in [

6,

7,

8,

9] first presents the model of IC selection mechanisms in networks. They focus on the strong impossibility for a deterministic IC mechanism and offer a probabilistic mechanism which randomly partitions the agents to voters and candidates. Also, the bound is not good.

2. Preliminaries

A directed forest is an acyclic, directed graph with maximal out-degree 1. Let V denote the vertices in this forest and E denote the edges. Then is the directed forest, which may not be connected. A vertex is called root if its out-degree is 0 and obviously every other vertices’ out-degree is 1.

We use to denote the number of vertices which can reach v either directly or indirectly plus itself, i.e. the size of the subtree with root v. If there is an edge , then we say u points to v and obviously a vertex can point at most one other vertex.

Here are some common terms for directed forest. A k-star tree is a tree with one center vertex (the root) and leaf vertices. A vertex is called isolated vertex if it has neither out-edge nor in-edge.

Let denote all the directed forests. A selection mechanism is a function , where n is the number of vertices in the forest, such that for any , we have . We define the probability of no selection is . We use for convenience and let denote the maximal in-degree of the forest.

Definition 1. A mechanism M is incentive-compatible (IC) if for any vertex , its probability of selection does not change when it changes which it points to.

Notice that increase is also not allowed. This means that one vertex can point to another new vertex, add or delete its direction as long as it does not break the rule of a directed forest. Using a formula, we can say , where is the forest after changes its direction. Next we give some other definitions for the property of selection mechanisms.

Definition 2. An IC mechanism M is fair if the following two conditions hold:

1. If , then .

2. If , then .

Definition 3. An IC mechanism M is exact if always holds.

Definition 4. An IC mechanism M is symmetric if for any automorphism that takes to , we have . Here, an automorphism taking to means that the two vertices are completely symmetric.

Notice that both fair and exact mechanisms are established on the premise of incentive-compatible. Next we give the benchmark we use to measure the performance of mechanisms.

Definition 5.

The quality of mechanism M for forest F is defined as follows:

And the general minimum quality is as follows:

Obviously we can find that the quality of a mechanism is a rational number in . And our goal is to improve the mechanism to get higher minimum quality as well as get the tight bound of such mechanisms. Here, the upper bound is achieved by a special case and the lower bound is achieved by a suitable mechanism.

3. Proof of Results

3.1. One Key Lemma

First we give a lemma which can help us simplify the IC mechanisms. The idea of this lemma comes from [

1].

Lemma 1. If a mechanism M is incentive-compatible, then there exists a symmetric mechanism with at least the same quality.

Proof. Consider different mechanisms which are symmetric by picking a random automorphism of F before using the original mechanism. Then we get the linear average mechanism. Therefore this new mechanism preserves IC / fair / exact property. Also its quality is no less than the original one. □

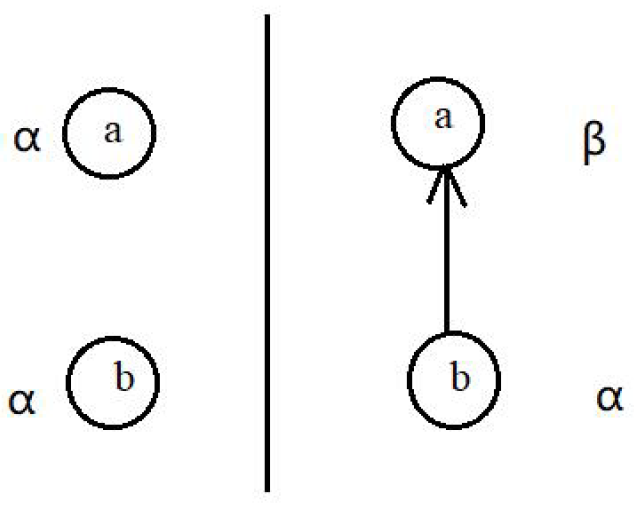

In order to see this method intuitively, let’s see the following IC example.

Let . First we let the two vertices be isolated. Suppose that and . Then we have . Then we let . This time according to IC and suppose . Then we have and .

So with restrictions

, we can get the following results:

So here we only need to prove that

Then we only need to prove that, the left part is smaller than one case of the rightp part. Notice that

So we have . With this lemma, we can assume the mechanisms are always symmetric when computing the bound of quality for IC / fair / exact mechanisms.

3.2. Results for

Theorem 1. When , holds for any IC mechanism M and this bound is tight, i.e. . For fair and exact mechanisms, the result does not change.

Proof. There are two cases for

. The first is

, so we assume

. The second is

, and according to IC, we know

and assume

. So we have the following restrictions:

Therefore we get the quality:

The equality holds if and only if and . Notice such mechanism is also fair and exact, so we prove the tight bound of quality for is 0.8. □

So this means that even if for only two persons, it’s still not very easy to keep both IC and fair (and exact). Of course we can use random selecting method (algorithm), and obviously it is IC (but not fair). But the bound of this algorithm is very bad, which is no more than half of the optimal method.

3.3. Results of IC Mechanisms for

Theorem 2. When , We can find an IC mechanism M with .

Proof. There are 4 cases for :

Case 1: . We assume .

Case 2: . We assume . Notice if vertex 1 deletes its direction, then it will be the same as every vertex in case 1.

Case 3: . We assume . Notice if vertex 1 deletes its direction, then it will be the same as vertex 3 in case 2; and if vertex 2 deletes its direction, then it will be the same as vertex 2 in case 2.

Case 4: . We assume . Notice if vertex 1 or vertex 3 deletes its direction, then it will be the same as vertex 3 in case 2.

Therefore we want to get the following result as maximal as possible:

This is similar to a linear programming problem. Notice that

and

, we have

Let

, then we have

Notice that

, then we have

This formula reaches its maximum when

, therefore

The equality holds if and only if . In this way, we prove this theorem. Compared with , we can find that this case is a little worse than the previous one, which means with larger n, the quality may decrease. □

3.4. Results of Fair Mechanisms for

Theorem 3. When , We can find a fair mechanism M with .

Proof. In the same way, we write the probability distribution for the 4 cases.

Case 1: . We assume .

Case 2: . We assume and . Notice that a fair mechanism requires that all the vertices with the same number of “supporters" should have the same probabilities.

Case 3: . We assume . Notice that a fair mechanism is also IC, so we should apply the restrictions as above.

Case 4: . We assume and . We can find that with a new restriction “fairness", the number of variables needed decreases.

Therefore we want to get the following result as maximal as possible:

Consider

and

, then we can simplify this question:

Let

, then we have

This formula reaches its minimum when

. Therefore we have

In this way we prove the theorem and the equality holds if and only if . □

3.5. Results of Exact Mechanisms for

Theorem 4. When , We can find an exact mechanism M with , which is a tight bound.

Proof. We use the same cases as IC mechanisms and add some extra restrictions. Then we have

After simplifying, we get

Finally, we get the formula as following:

Therefore when , the mechanism achieves quality . We finish the proof. □

Linear program model is useful in low-sample situations. But with more agents, the difficulty grows rapidly. So it’s important to find a more general way to study the lower bound and upper bound for more-agent situations.

Also, we can use these results in our daily life, including “decide where to go during vacation", “select a leader for student group", etc. Since we know how to design an IC mechanism, we will meet less problems.

Acknowledgments

We thank our collaborators for their insightful discussions.

References

- Babichenko, Yakov, Oren Dean, and Moshe Tennenholtz. “Incentive-compatible selection mechanisms for forests." In Proceedings of the 21st ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, pp. 111-131. 2020.

- Procaccia, Ariel D., and Moshe Tennenholtz. “Approximate mechanism design without money." ACM Transactions on Economics and Computation (TEAC) 1, no. 4 (2013): 1-26. [CrossRef]

- G. Caldarelli, Scale-Free Networks, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Babaioff, Moshe, Moran Feldman, and Moshe Tennenholtz. “Mechanism design with strategic mediators." ACM Transactions on Economics and Computation (TEAC) 4, no. 2 (2016): 1-48. [CrossRef]

- Babichenko, Yakov, Oren Dean, and Moshe Tennenholtz. “Incentive-compatible diffusion." In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, pp. 1379-1388. 2018.

- Alon, Noga, Felix Fischer, Ariel Procaccia, and Moshe Tennenholtz. “Sum of us: Strategyproof selection from the selectors." In Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge, pp. 101-110. 2011.

- Hongwei Niu, Zhengyuan Lin, Xuan Zhang, and Tianzhi Jia. “Image Segmentation For pneumothorax disease Based On based on Nested Unet Model." In 2022 3rd International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning & International Conference on Computer Engineering and Applications (CVIDL & ICCEA) (pp. 756-759). IEEE. 2022.

- Siwen Wu, Jiale Wang, Yihan Ping, and Xuan Zhang. “Research on Individual Recognition and Matching of Whale and Dolphin Based on EfficientNet Model." In 2022 3rd International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering (ICBAIE) (pp. 635-638). IEEE. 2023.

- Hui Zhang, Fengrui Zhang, Bing Gong, Xuan Zhang, and Yifan Zhu. “The Optimization of Supply Chain Financing for Bank Green Credit Using Stackelberg Game Theory in Digital Economy Under Internet of Things." Journal of Organizational and End User Computing (JOEUC), 35(3), 1-16. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).