Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Metabolic Activities of Human CYPs

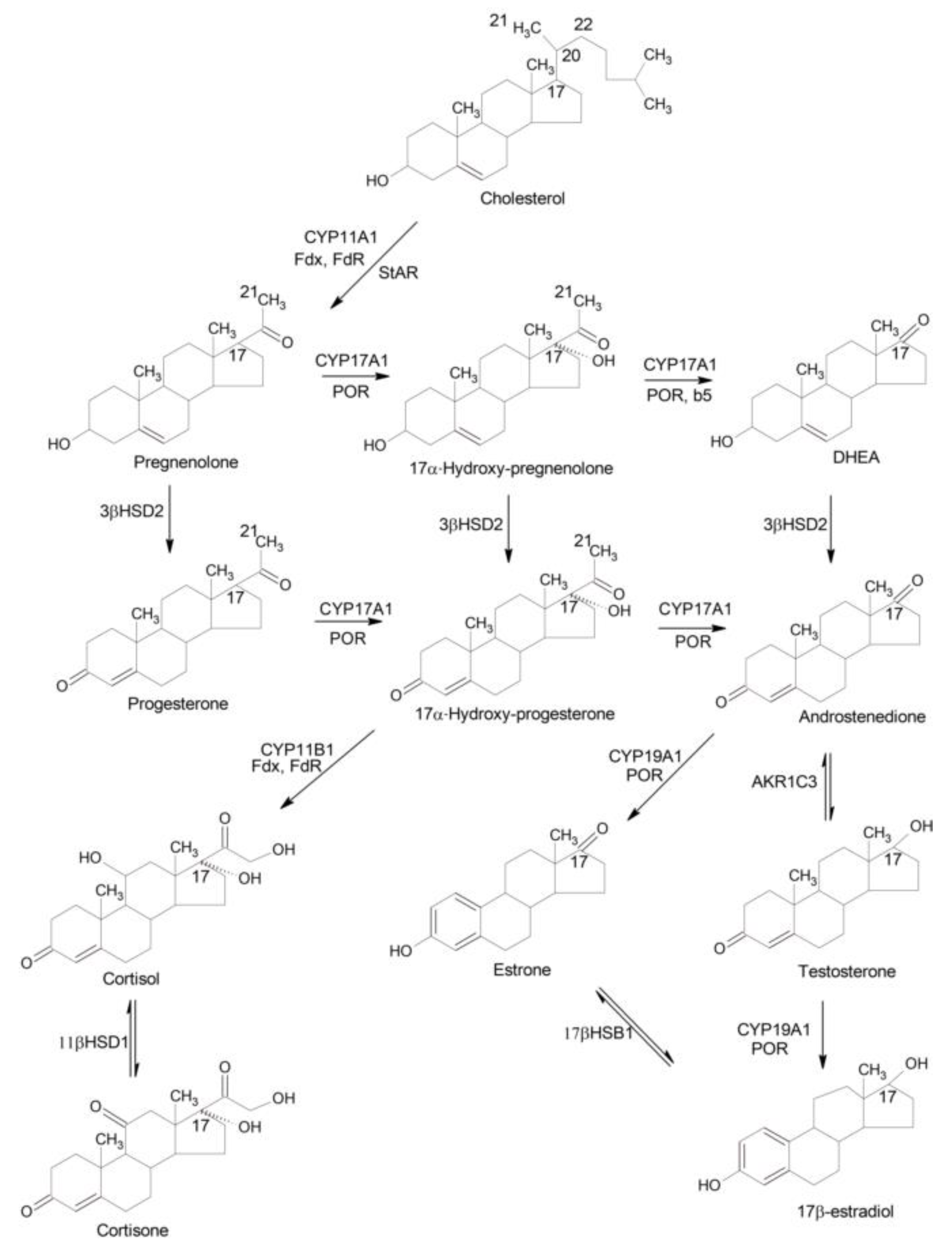

2.1. Biosynthesis of Steroid Hormones

2.2. Detoxification vs Bioactivation of Xenobiotics

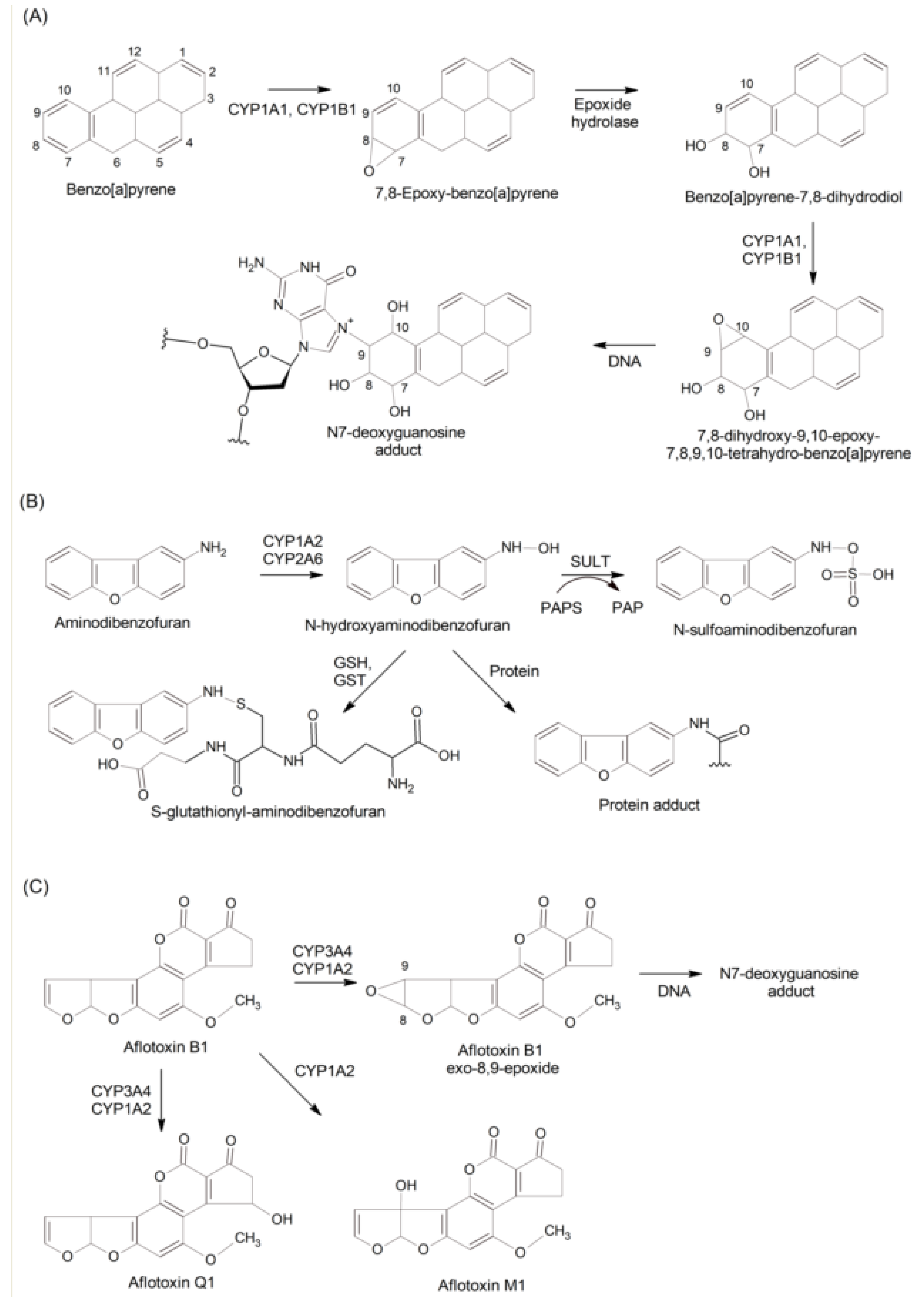

2.3. Bioactivation vs Inactivation of Procarcinogens

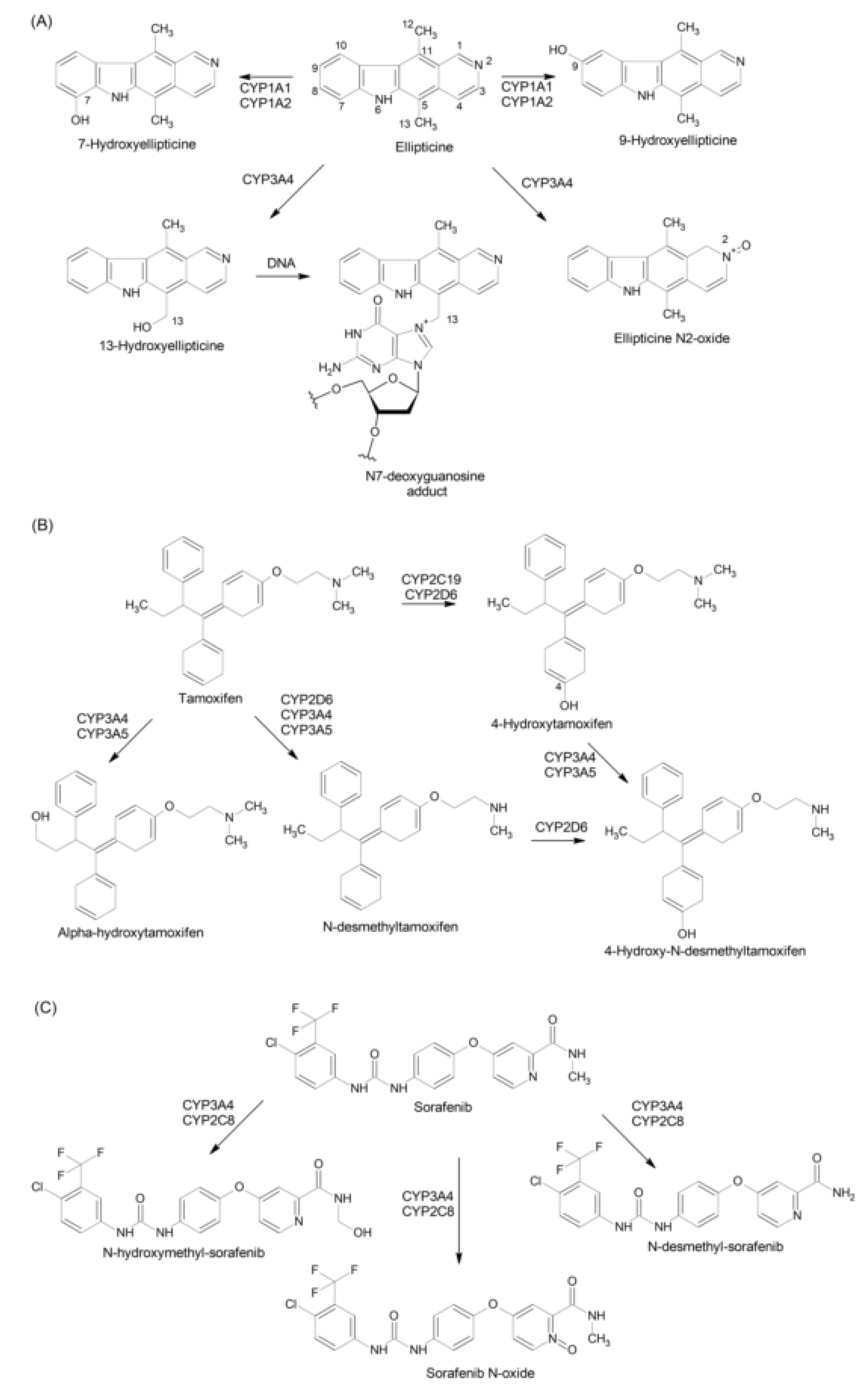

2.4. Metabolism of Drugs

2.4.1. Drugs as CYP Substrates

2.4.2. Drugs as CYP Inducers: the Roles of Nuclear Receptors and Drug Transporters

2.4.3. CYP Inhibition: Drug-Drug Interactions

3. Roles of CYPs in Cancer

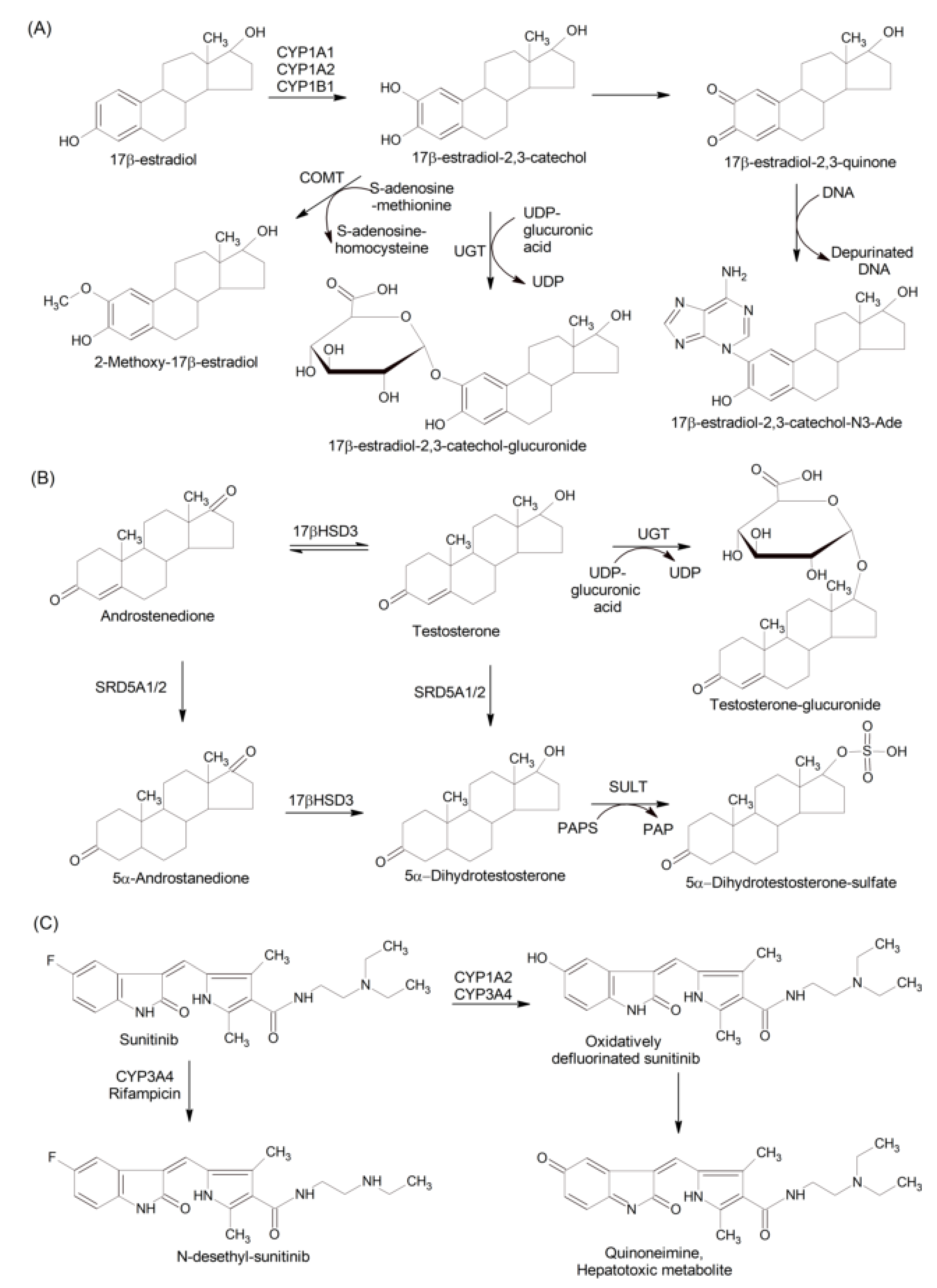

3.1. Breast, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer

3.1.1. Effects of Estrogen Metabolites

3.1.2. CYP Gene Polymorphisms

3.2. Prostate Cancer

3.2.1. Effects of Androgen Metabolism

3.2.2. CYP Gene Polymorphisms

3.3. CYP Hepatotoxicity and Liver Cancer

3.3.1. Anticancer Drug-Induced Liver Injury

3.3.2. CYP Gene Polymorphisms and Liver Cancer

4. Conclusions and Challenges

References

- D.R. Nelson, A world of cytochrome P450s, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci., 368(1612) (2013), p. 20120430. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Nelson, Cytochrome P450 diversity in the tree of life, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom., 1866(1) (2018), p. 141-154. [CrossRef]

- M. Šrejber, V. Navrátilová, M. Paloncýová, V. Bazgier, K. Berka, P. Anzenbacher, M. Otyepka, Membrane-attached mammalian cytochromes P450: An overview of the membrane's effects on structure, drug binding, and interactions with redox partners, J. Inorg. Biochem., 183 (2018), p. 117-136. [CrossRef]

- M. Nishimura, H. Yaguti, H. Yoshitsugu, S. Naito, T. Satoh, Tissue distribution of mRNA expression of human cytochrome P450 isoforms assessed by high-sensitivity real-time reverse transcription PCR. Yakugaku Zasshi, 123(5) (2003), p. 369-375. [CrossRef]

- N.C. Sadler, P. Nandhikonda, B.J. Webb-Robertson, C. Ansong, L.N. Anderson, J.N. Smith, R.A. Corley, A.T. Wright, Hepatic cytochrome P450 activity, abundance, and expression throughout human development, Drug Metab. Dispos., 44(7) (2016), p. 984-991. [CrossRef]

- J. McGraw, D. Waller, Cytochrome P450 variations in different ethnic populations, Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 8(3) (2012), p. 371-382. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Gerges, A.O.S. El-Kadi, Sexual dimorphism in the expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in rat heart, liver, kidney, lung, brain, and small intestine, Drug Metab. Dispos. 51(1) (2023), p. 81-94. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Fuscoe, V. Vijay, J.P. Hanig, T. Han, L. Ren, J.J. Greenhaw, R.D. Beger, L.M. Pence, Q. Shi, Hepatic transcript profiles of cytochrome P450 genes predict sex differences in drug metabolism, Drug Metab. Dispos. 48(6) (2020), p. 447-458. [CrossRef]

- M.F. Hoffmann, S.C. Preissner, J. Nickel, M. Dunkel, R. Preissner, S. Preissner, The Transformer database: biotransformation of xenobiotics, Nucleic Acids Res., 42(Database issue) (2014) D1113-D1117. [CrossRef]

- S.C. Khojasteh, N.N. Bumpus, J.P. Driscoll, G.P. Miller, K. Mitra, I.M.C.M. Rietjens, D. Zhang, Biotransformation and bioactivation reactions - 2018 literature highlights, Drug Metab. Rev., 51(2) (2019), p. 121-161. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhao, J. Ma, M. Li, Y. Zhang, B. Jiang, X. Zhao, C. Huai, L. Shen, N. Zhang, L. He, S. Qin, Cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug metabolism in humans, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22(23) (2021), p. 12808. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Guengerich, Y. Tateishi, K.D. McCarty, F.K. Yoshimoto, Updates on mechanisms of cytochrome P450 catalysis of complex steroid oxidations, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 25(16) (2024), p. 9020. [CrossRef]

- A.R. Modi, J.H. Dawson, Oxidizing intermediates in P450 catalysis: a case for multiple oxidants, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., 851 (2015), p. 63-81. [CrossRef]

- K. Fujiyama, T. Hino, S. Nagano, Diverse reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 and biosynthesis of steroid hormone, Biophys. Physicobiol., (19) (2022), p. e190021. [CrossRef]

- D.W. Nebert, K. Wikvall, W.L. Miller, Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci., 368(1612) (2013), p. 20120431. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yan, J. Wu, G. Hu, C. Gao, L. Guo, X. Chen, L. Liu, W. Song, Current state and future perspectives of cytochrome P450 enzymes for C-H and C=C oxygenation, Synth. Syst. Biotechnol., 7(3) (2022), p. 887-899. [CrossRef]

- J. Ducharme, K. Auclair, Use of bioconjugation with cytochrome P450 enzymes, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom., 1866(1) (2018), p. 32-51. [CrossRef]

- M. Silva, M.D.G. Carvalho, Detoxification enzymes: cellular metabolism and susceptibility to various diseases, Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras., 64(4) (2018), p. 307-310. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Mokhosoev, D.V. Astakhov, A.A. Terentiev, N.T. Moldogazieva, Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems: Diversity and plasticity for adaptive stress response, Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol., (193) (2024), p. 19-34. [CrossRef]

- M. Ingelman-Sundberg, Cytochrome P450 polymorphism: From evolution to clinical use, Adv. Pharmacol., 95 (2022), p.393-416. [CrossRef]

- I.S. Lee, D. Kim, Polymorphic metabolism by functional alterations of human cytochrome P450 enzymes, Arch. Pharm. Res., 34(110) (2011), p. 1799-1816. [CrossRef]

- N. Gao, X. Tian, Y. Fang, J. Zhou, H. Zhang, Q. Wen, L. Jia, J. Gao, B. Sun, J. Wei, Y. Zhang, M. Cui, H. Qiao, Gene polymorphisms and contents of cytochrome P450s have only limited effects on metabolic activities in human liver microsomes, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., (92) (2016), p. 86-97. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, Y.F. Lu, J.C. Corton, C.D. Klaassen, Expression of cytochrome P450 isozyme transcripts and activities in human livers, Xenobiotica, 51(3) (2021), p. 279-286. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Zhou, J.P. Liu, B. Chowbay, Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact, Drug Metab. Rev., 41(2) (2009), p. 89-295. [CrossRef]

- F. Bray, M. Laversanne, E. Weiderpass, I. Soerjomataram, The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide, Cancer, 127(16) (2021), p. 3029-3030. [CrossRef]

- C. Mattiuzzi, G. Lippi, Current cancer epidemiology, J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health., (9)4 (2019), p. 217-222. [CrossRef]

- H. Sung, J. Ferlay, R.L. Siegel, M. Laversanne, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal, F. Bray, Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries, CA Cancer J. Clin., 71(3), p. 209-249. [CrossRef]

- N.M. Anderson, M.C. Simon, The tumor microenvironment, Curr. Biol., 30(16) (2020), p. R921-R925. [CrossRef]

- C.M. Neophytou, M. Panagi, T. Stylianopoulos, P. Papageorgis, The role of tumor microenvironment in cancer metastasis: Molecular mchanisms and therapeutic opportunities, Cancers (Basel), 13(9) (2021), p. 2053. [CrossRef]

- M. Benvenuto, C. Focaccetti, Tumor microenvironment: Cellular interaction and metabolic adaptations, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 25(7) (2024), p. 3642. [CrossRef]

- S. Arfin, N.K. Jha, S.K. Jha, K.K. Kesari, J. Ruokolainen, S. Roychoudhury, B. Rathi, D. Kumar, Oxidative stress in cancer cell metabolism, Antioxidants (Basel), 10(5) (2021), p. 642. [CrossRef]

- N.T. Moldogazieva, I.M. Mokhosoev, A.A. Terentiev, Metabolic heterogeneity of cancer cells: An interplay between HIF-1, GLUTs, and AMPK, Cancers (Basel) 12(4) (2020). p. 862. [CrossRef]

- N.T. Moldogazieva, S.P. Zavadskiy, D.V. Astakhov, A.A. Terentiev, Lipid peroxidation: Reactive carbonyl species, protein/DNA adducts, and signaling switches in oxidative stress and cancer, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 687 (2023), p. 149167. [CrossRef]

- S. Zavadskiy, S. Sologova, N. Moldogazieva, Oxidative distress in aging and age-related diseases: Spatiotemporal dysregulation of protein oxidation and degradation, Biochimie, 195 (2022), p. 114-134. [CrossRef]

- A.I. Archakov, I.M. Mokhosoev, Modification of proteins by active oxygen and their degradation, Biokhimiia, 54(2) (1989), p. 179-186.

- A.M. Alzahrani, P. Rajendran, The multifarious link between cytochrome P450s and cancer, Oxid. Med. Cell Longev., 2020 (2020), p. 3028387. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Guengerich, Cytochrome P450 enzymes as drug targets in human disease, Drug Metab. Dispos., 52(6) (2024), p. 493-497. [CrossRef]

- B. Hossam Abdelmonem, N.M. Abdelaal, E.K.E. Anwer, A.A. Rashwan, M.A. Hussein, Y.F. Ahmed, R. Khashana, M.M. Hanna, A. Abdelnaser, Decoding the role of CYP450 enzymes in metabolism and disease: A comprehensive review, Biomedicines, 12(7) (2024), p. 1467. [CrossRef]

- D.Y. Cooper, R.W. Estabrook, O. Rosenthal, The stoichiometry of C21 hydroxylation of steroids by adrenocortical microsomes, J. Biol. Chem., 238 (1963), p. 1320-1323.

- D.Y. Cooper, S. Levin, S. Narasimhulu, O. Rosenthal, Photochemical action spectrum of the terminal oxidase of the mixed function oxidase systems, Science, 147(3556) (1965), p. 400-402. [CrossRef]

- R.H. Menard, S.A. Latif, J.L. Purvis, The intratesticular localization of cytochrome P-450 and cytochrome P-450-dependent enzymes in the rat testis, Endocrinology, 97(6) (1975) p. 1587-1592. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Purvis, R.H. Menard, Compartmentation of microsomal cytochrome P-450 and 17 alpha-hydroxylase activity in the rat testis, Curr. Top Mol. Endocrinol., 2 (1975), p. 65-84. [CrossRef]

- S. Nakajin, P.F. Hall, Microsomal cytochrome P-450 from neonatal pig testis. Purification and properties of A C21 steroid side-chain cleavage system (17 alpha-hydroxylase-C17,20 lyase), J. Biol. Chem., 256(8) (1981), p. 3871-3876.

- L. Schiffer, L. Barnard, E.S. Baranowski, L.C. Gilligan, A.E. Taylor, W. Arlt, C.H.L. Shackleton, K.H. Storbeck, Human steroid biosynthesis, metabolism and excretion are differentially reflected by serum and urine steroid metabolomes: A comprehensive review, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 194 (2019), p. 105439. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chien, K. Rosal, B.C. Chung, Function of CYP11A1 in the mitochondria, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 441 (2017), p. 55-61. [CrossRef]

- K. Fujiyama, T. Hino, S. Nagano, Diverse reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 and biosynthesis of steroid hormone, Biophys. Physicobiol., 19 (2022), p. e190021. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Conley, I.M. Bird, The role of cytochrome P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the integration of gonadal and adrenal steroidogenesis via the delta 5 and delta 4 pathways of steroidogenesis in mammals, Biol. Reprod., 56(4) (1997), p. 789-799. [CrossRef]

- D.H. Geller, R.J. Auchus, W.L. Miller, P450c17 mutations R347H and R358Q selectively disrupt 17,20-lyase activity by disrupting interactions with P450 oxidoreductase and cytochrome b5, Mol. Endocrinol., 13(1) (1999), p. 167-175. [CrossRef]

- W.L. Miller, Androgen biosynthesis from cholesterol to DHEA, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 198(1-2) (2002), p. 7-14. [CrossRef]

- C.M. Klinge, B.J. Clark, R.A. Prough, Dehydroepiandrosterone research: Past, current, and future, Vitam. Horm., 108 (2018), p. 1-28. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Petrunak, N.M. DeVore, P.R. Porubsky, E.E. Scott, Structures of human steroidogenic cytochrome P450 17A1 with substrates, J. Biol. Chem., 289(47) (2014), p. 32952-32964. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Penning, The aldo-keto reductases (AKRs): Overview, Chem. Biol. Interact., 234 (2015), p. 236-246. [CrossRef]

- C. Stocco, Tissue physiology and pathology of aromatase, Steroids, 77(1-2) (2012), p. 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Y. Takeda, M. Demura, M. Kometani, S. Karashima, T. Yoneda, Y. Takeda, Molecular and epigenetic control of aldosterone synthase, CYP11B2 and 11-hydroxylase, CYP11B1, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(6) (2023), p. 5782. [CrossRef]

- A. Midzak, V. Papadopoulos, Adrenal mitochondria and steroidogenesis: From individual proteins to functional protein assemblies, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne), 7 (2016), p. 106. [CrossRef]

- S. Brixius-Anderko, E.E. Scott, Structural and functional insights into aldosterone synthase interaction with its redox partner protein adrenodoxin, J. Biol. Chem., 296 (2021), p. 100794. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Ziegler, G.E. Schulz, Crystal structures of adrenodoxin reductase in complex with NADP+ and NADPH suggesting a mechanism for the electron transfer of an enzyme family, Biochemistry 39(36) (2000), p. 10986-10995. [CrossRef]

- S. Rendic, Summary of information on human CYP enzymes: human P450 metabolism data, Drug Metab. Rev., 34(1-2) (2002), p. 83-448. [CrossRef]

- S. Rendic, F.P. Guengerich, Survey of human oxidoreductases and cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic and natural chemicals, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 28(1) (2015), p. 38-42. [CrossRef]

- B. Merchel Piovesan Pereira, I. Tagkopoulos, Benzalkonium chlorides: Uses, regulatory status, and microbial resistance, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 85(13) (2019), p. e00377-19. [CrossRef]

- W.A. Arnold, A. Blum, J. Branyan, T.A. Bruton, C.C. Carignan, G. Cortopassi, S. Datta, J. DeWitt, A.C. Doherty, R.U. Halden, H. Harari, E.M. Hartmann, T.C. Hrubec, S. Iyer, C.F. Kwiatkowski, J. LaPier, D. Li, L. Li, J.G. Muñiz Ortiz, A. Salamova, T. Schettler, R.P. Seguin, A. Soehl, R. Sutton, L. Xu, G. Zheng, Quaternary ammonium compounds: A chemical class of emerging concern, Environ. Sci. Technol., 57(20) (2023), p. 7645-7665. [CrossRef]

- R.P. Seguin, J.M. Herron, V.A. Lopez, J.L. Dempsey, L. Xu, Metabolism of benzalkonium chlorides by human hepatic cytochromes P450, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 32(12) (2019), p. 2466-2478. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Kim, D. Kwon, S. Lee, S.W. Son, J.T. Kwon, P.-J. Kim, Y.-H. Lee, Y.-S. Jung, Concentration- and time-dependent effects of benzalkonium chloride in human lung epithelial cells: Necrosis, apoptosis, or epithelial mesenchymal transition, Toxics, 8 (2020), p. 17. doi: 10.3390/toxics8010017.

- A.M. King, C.K. Aaron, Organophosphate and carbamate poisoning, Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am., 33(1) (2015), p. 133-151. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Jett, J.R. Richardson, Neurotoxic pesticides. In: Dobbs MR, editor. Clinical Neurotoxicology: Syndromes, Substances, and Environments. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 491–499.

- Y.H. Jan, J.R. Richardson, A.A. Baker, V. Mishin, D.E. Heck, D.L. Laskin, J.D. Laskin, Novel approaches to mitigating parathion toxicity: targeting cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism with menadione, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 1378(1) (2016), p. 80-86. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Yan, J.R. Richardson, A.A. Baker, V. Mishin, D.E. Heck, D.L. Laskin, J.D. Laskin, Vitamin K3 (menadione) redox cycling inhibits cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism and inhibits parathion intoxication, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 288(1) (2015), p. 114-120. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Foxenberg, B.P. McGarrigle, J.B. Knaak, P.J. Kostyniak, J.R. Olson, Human hepatic cytochrome p450-specific metabolism of parathion and chlorpyrifos, Drug Metab. Dispos., 35(2) (2007), p. 189-193. [CrossRef]

- H. Imaishi, T. Goto, Effect of genetic polymorphism of human CYP2B6 on the metabolic activation of chlorpyrifos, Pestic. Biochem. Physiol., 144 (2018), p. 42-48. [CrossRef]

- A.L. Crane, K. Klein, J.R. Olson, Bioactivation of chlorpyrifos by CYP2B6 variants, Xenobiotica, 42(12) (2012), p. 1255-1262. [CrossRef]

- J. Tang, Y. Cao, R.L. Rose, E. Hodgson, In vitro metabolism of carbaryl by human cytochrome P450 and its inhibition by chlorpyrifos, Chem. Biol. Interact., 141(3) (2002), p. 229-241. [CrossRef]

- K.A. Usmani, T.M. Cho, R.L. Rose, E. Hodgson, Inhibition of the human liver microsomal and human cytochrome P450 1A2 and 3A4 metabolism of estradiol by deployment-related and other chemicals, Drug Metab. Dispos., 34(9) (2006), p. 1606-1614. [CrossRef]

- S. Rendic, F.P. Guengerich, Contributions of human enzymes in carcinogen metabolism, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 25(7) (2012), p. 1316-1383. [CrossRef]

- Y.W. Sun, F.P. Guengerich, A.K. Sharma, T. Boyiri, S. Amin, K. el-Bayoumy, Human cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1 catalyze ring oxidation but not nitroreduction of environmental pollutant mononitropyrene isomers in primary cultures of human breast cells and cultured MCF-10A and MCF-7 cell lines, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 17(8) (2004), p. 1077-1085. [CrossRef]

- L. Reed, V.M. Arlt, D.H. Phillips, The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in carcinogen activation and detoxication: an in vivo-in vitro paradox, Carcinogenesis, 39(7) (2018), p. 851-859. [CrossRef]

- T. Shimada, C.L. Hayes, H. Yamazaki, S. Amin, S.S. Hecht, F.P. Guengerich, T.R. Sutter, Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P-450 1B1, Cancer Res., 56(13) (1996), p. 2979-2984.

- T. Shimada, E.M. Gillam, Y. Oda, F. Tsumura, T.R. Sutter, F.P. Guengerich, K. Inoue, Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene to trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7, 8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene by recombinant human cytochrome P450 1B1 and purified liver epoxide hydrolase, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 12(7) (1999), p. 623-629. [CrossRef]

- J. Jacob, G. Raab, V. Soballa, W.A. Schmalix, G. Grimmer, H. Greim, J. Doehmer, A. Seidel, Cytochrome P450-mediated activation of phenanthrene in genetically engineered V79 Chinese hamster cells, Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 1(1) (1996), p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- M. Baum, S. Amin, F.P. Guengerich, S.S. Hecht, W. Köhl, G. Eisenbrand, Metabolic activation of benzo[c]phenanthrene by cytochrome P450 enzymes in human liver and lung, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 14(6) (2001), p. 686-693. [CrossRef]

- A. Seidel, V.J. Soballa, G. Raab, H. Frank, H. Greim, G. Grimmer, J. Jacob, J. Doehmer, Regio- and stereoselectivity in the metabolism of benzo[c]phenanthrene mediated by genetically engineered V79 Chinese hamster cells expressing rat and human cytochromes P450, Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 5(3) (1998), p. 179-196. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li K, Zou Y, Zhou M, Li J, Wu C, Tan R, Liao Y, Li W, Zheng J. Metabolic activation of 3-aminodibenzofuran mediated by P450 enzymes and sulfotransferases. Toxicol Lett., 360 (2022), p. 44-52. [CrossRef]

- M. Pitaro, N. Croce, V. Gallo, A. Arienzo, G. Salvatore, G. Antonini, Coumarin-induced hepatotoxicity: A narrative review, Molecules, 27(24) (2022), p. 9063. [CrossRef]

- N. Murayama, H. Yamazaki, Metabolic activation and deactivation of dietary-derived coumarin mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes in rat and human liver preparations, J. Toxicol. Sci., 46(8) (2021), p. 371-378. [CrossRef]

- Y.F. Ueng, T. Shimada, H. Yamazaki, F.P. Guengerich, Oxidation of aflatoxin B1 by bacterial recombinant human cytochrome P450 enzymes, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 8(2) (1995), p. 218-225. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Guengerich, W.W. Johnson, T. Shimada, Y.F. Ueng, H. Yamazaki, S. Langouët, Activation and detoxication of aflatoxin B1, Mutat. Res., 402(1-2) (1998), p. 121-128. [CrossRef]

- T. Shimada, F.P. Guengerich, Evidence for cytochrome P-450NF, the nifedipine oxidase, being the principal enzyme involved in the bioactivation of aflatoxins in human liver, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 86(2) (1989), p. 462-465. [CrossRef]

- V.M. Arlt, A. Hewer, B.L. Sorg, H.H. Schmeiser, D.H. Phillips, M. Stiborova, 3-aminobenzanthrone, a human metabolite of the environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone, forms DNA adducts after metabolic activation by human and rat liver microsomes: evidence for activation by cytochrome P450 1A1 and P450 1A2, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 17(8) (2004), p. 1092-1101. [CrossRef]

- M. Miksanová, M. Sulc, H. Rýdlová, H.H. Schmeiser, E. Frei, M. Stiborová, Enzymes involved in the metabolism of the carcinogen 2-nitroanisole: evidence for its oxidative detoxication by human cytochromes P450, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 17(5) (2004), p. 663-671. [CrossRef]

- H. Dracínska, M. Miksanová, M. Svobodová, S. Smrcek, E. Frei, H.H. Schmeiser, M. Stiborová, Oxidative detoxication of carcinogenic 2-nitroanisole by human, rat and rabbit cytochrome P450, Neuro Endocrinol. Lett., 27 (Suppl 2) (2006), p. 9-13.

- U.M. Zanger, M. Schwab, Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation, Pharmacol. Ther., 138(1) (2013), p. 103-141. [CrossRef]

- Almazroo, M.K. Miah, R. Venkataramanan, Drug metabolism in the liver, Clin. Liver Dis., 21(1) (2017), p. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- S.P. Rendic, F.P. Guengerich, Human family 1-4 cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of xenobiotic and physiological chemicals: an update, Arch. Toxicol., 95(2) (2021), p. 395-472. [CrossRef]

- B. Achour, J. Barber, A. Rostami-Hodjegan, Expression of hepatic drug-metabolizing cytochrome p450 enzymes and their intercorrelations: a meta-analysis, Drug Metab. Dispos., 42(8) (2014), p. 1349-1356. [CrossRef]

- M. Samadi-Baboli, G. Favre, E. Blancy, G. Soula, Preparation of low density lipoprotein-9-methoxy-ellipticin complex and its cytotoxic effect against L1210 and P 388 leukemic cells in vitro, Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol., 25(2) (1989), p. 233-241. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Froelich-Ammon, M.W. Patchan, N. Osheroff, R.B. Thompson, Topoisomerase II binds to ellipticine in the absence or presence of DNA. Characterization of enzyme-drug interactions by fluorescence spectroscopy, J. Biol. Chem., 270(25) (1995), p. 14998-5004. [CrossRef]

- M. Stiborová, J. Sejbal, L. Borek-Dohalská, D. Aimová, J. Poljaková, K. Forsterová, M. Rupertová, J. Wiesner, J. Hudecek, M. Wiessler, E. Frei, The anticancer drug ellipticine forms covalent DNA adducts, mediated by human cytochromes P450, through metabolism to 13-hydroxyellipticine and ellipticine N2-oxide, Cancer Res., 64(22) (2004), p. 8374-8380. [CrossRef]

- V. Kotrbová, B. Mrázová, M. Moserová, V. Martínek, P. Hodek, J. Hudeček, E. Frei, M. Stiborová, Cytochrome b(5) shifts oxidation of the anticancer drug ellipticine by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2 from its detoxication to activation, thereby modulating its pharmacological efficacy, Biochem. Pharmacol., 82(6) (2011), p. 669-680. [CrossRef]

- L. Pichard-Garcia, R.J. Weaver, N. Eckett, G. Scarfe, J.M. Fabre, C. Lucas, P. Maurel, The olivacine derivative s 16020 (9-hydroxy-5,6-dimethyl-N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)-6H-pyrido(4,3-B)-carbazole-1-carboxamide) induces CYP1A and its own metabolism in human hepatocytes in primary culture, Drug Metab. Dispos., 32(1) (2004), p. 80-88. [CrossRef]

- B. Tylińska, B. Wiatrak, Bioactive olivacine derivatives-potential application in cancer therapy, Biology (Basel), 10(6) (2021), p. 564. [CrossRef]

- J. Piasny, B. Wiatrak, A. Dobosz, B. Tylińska, T. Gębarowski, Antitumor activity of new olivacine derivatives, Molecules, 25(11) (2020), p. 2512. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Hsiang, R. Hertzberg, S. Hecht, L.F. Liu, Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I, J. Biol. Chem., 260(27) (1985), p. 14873-14878.

- M.C. Haaz, C. Riché, L.P. Rivory, J. Robert, Biosynthesis of an aminopiperidino metabolite of irinotecan [7-ethyl-10-[4-(1-piperidino)-1-piperidino]carbonyloxycamptothecine] by human hepatic microsomes, Drug Metab. Dispos., 26(8) (1998), p. 769-774.

- A. Santos, S. Zanetta, T. Cresteil, A. Deroussent, F. Pein, E. Raymond, L. Vernillet, M.L. Risse, V. Boige, A. Gouyette, G. Vassal, Metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11) by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 in humans, Clin. Cancer Res., 6(5) (2000), p. 2012-2020.

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG); C. Davies, J. Godwin, R. Gray, M. Clarke, D. Cutter, S. Darby, P. McGale, H.C. Pan, C. Taylor, Y.C. Wang, M. Dowsett, J. Ingle, R. Peto, Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials, Lancet, 378(9793) (2011), p. 771-784. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Singh, P.A. Francis, M. Michael, Tamoxifen, cytochrome P450 genes and breast cancer clinical outcomes, Breast, 20(2) (2011), p. 111-118. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Goetz, S.K. Knox, V.J. Suman, J.M. Rae, S.L. Safgren, M.M. Ames, D.W. Visscher, C. Reynolds, F.J. Couch, W.L. Lingle, R.M. Weinshilboum, E.G. Fritcher, A.M. Nibbe, Z. Desta, A. Nguyen, D.A. Flockhart, E.A. Perez, J.N. Ingle, The impact of cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism in women receiving adjuvant tamoxifen, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 101(1) (2007), p. 113-121. [CrossRef]

- E.Y. Tan, L. Bharwani, Y.H. Chia, R.C.T. Soong, S.S.Y. Lee, J.J.C. Chen, P.M.Y Chan, Impact of cytochrome P450 2D6 polymorphisms on decision-making and clinical outcomes in adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast cancer, World J. Clin. Oncol., 13(8) (2022), p. 712-724. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Stingl, S. Parmar, A. Huber-Wechselberger, A. Kainz, W. Renner, A. Seeringer, J. Brockmöller, U. Langsenlehner, P. Krippl, E. Haschke-Becher, Impact of CYP2D6*4 genotype on progression free survival in tamoxifen breast cancer treatment, Curr. Med. Res. Opin., 26(11) (2010), p. 2535-2542. [CrossRef]

- Z. Desta, B.A. Ward, N.V. Soukhova, D.A. Flockhart, Comprehensive evaluation of tamoxifen sequential biotransformation by the human cytochrome P450 system in vitro: prominent roles for CYP3A and CYP2D6, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 310(3) (2004), p. 1062-1075. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Boocock, K. Brown, A.H. Gibbs, E. Sanchez, K.W. Turteltaub, I.N. White, Identification of human CYP forms involved in the activation of tamoxifen and irreversible binding to DNA, Carcinogenesis, 23(11) (2002), p. 1897-901. [CrossRef]

- Y.C. Lim, Z. Desta, D.A. Flockhart, T.C. Skaar, Endoxifen (4-hydroxy-N-desmethyl-tamoxifen) has anti-estrogenic effects in breast cancer cells with potency similar to 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 55(5) (2005), p. 471-478. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Boocock, J.L. Maggs, I.N. White, B.K. Park, Alpha-hydroxytamoxifen, a genotoxic metabolite of tamoxifen in the rat: identification and quantification in vivo and in vitro, Carcinogenesis, 20(1) (1999), p. 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Y. Okamoto, S. Shibutani, Development of novel and safer anti-breast cancer agents, SS1020 and SS5020, based on a fundamental carcinogenic research, Genes Environ., 41 (2019), p. 9. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Klein, C.F. Thorn, Z. Desta, D.A. Flockhart, R.B. Altman, T.E. Klein, PharmGKB summary: tamoxifen pathway, pharmacokinetics, Pharmacogenet. Genomics, 23(11) (2013), p. 643-647. [CrossRef]

- N.T. Moldogazieva, D.S. Ostroverkhova, N.N. Kuzmich, V.V. Kadochnikov, A.A. Terentiev, Y.B. Porozov, Elucidating binding sites and affinities of ERα agonists and antagonists to human alpha-fetoprotein by in silico modeling and point mutagenesis, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(3) (2020), p. 893. [CrossRef]

- J.N. Mills, A.C. Rutkovsky, A. Giordano, Mechanisms of resistance in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer: overcoming resistance to tamoxifen/aromatase inhibitors, Curr. Opin. Pharmacol., (41) (2018), p. 59-65. [CrossRef]

- K. Kiyotani, T. Mushiroda, Y. Nakamura, H. Zembutsu, Pharmacogenomics of tamoxifen: roles of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters, Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet., 27(1) (2012), p. 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ando, E. Fuse, W.D. Figg, Thalidomide metabolism by the CYP2C subfamily, Clin. Cancer Res., 8(6) (2002), p. 1964-1973.

- P. Chhetri, A. Giri, S. Shakya, S. Shakya, B. Sapkota, K.C. Pramod, Current development of anti-cancer drug S-1, J. Clin. Diagn. Res., 10(11) (2016), p.XE01-XE05. [CrossRef]

- Yamamiya, K. Yoshisue, Y. Ishii, H. Yamada, K. Yoshida, Enantioselectivity in the cytochrome P450-dependent conversion of tegafur to 5-fluorouracil in human liver microsomes, Pharmacol. Res. Perspect., 1(1) (2013), p. e00009. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Tebbens, M. Azar, E. Friedmann, M. Lanzendörfer, P. Pávek, Mathematical models in the description of pregnane X receptor (PXR)-regulated cytochrome P450 enzyme induction, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 19(6) (2018), p. 1785. [CrossRef]

- T. Smutny, S. Mani, P. Pavek, Post-translational and post-transcriptional modifications of pregnane X receptor (PXR) in regulation of the cytochrome P450 superfamily, Curr. Drug Metab., 14(10) (2013), p. 1059-1069. [CrossRef]

- G. Bradley, P.F. Juranka, V. Ling, Mechanism of multidrug resistance, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 948(1) (1988), p. 87-128. [CrossRef]

- R.L. Juliano, V. Ling, A surface glycoprotein modulating drug permeability in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 455(1) (1976), p. 152-162. [CrossRef]

- Fardel, L. Payen, A. Courtois, L. Vernhet, V. Lecureur, Regulation of biliary drug efflux pump expression by hormones and xenobiotics, Toxicology, 167(1) (2001), p. 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lv, Y.Y. Luo, H.W. Ren, C.J. Li, Z.X. Xiang, Z.L. Luan, The role of pregnane X receptor (PXR) in substance metabolism, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne), 13 (2022), p. 959902. [CrossRef]

- P. Germain, B. Staels, C. Dacquet, M. Spedding, V. Laudet, Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors, Pharmacol. Rev., 58(4) (2006), p.685-704. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, M.H. Lambert, H.E. Xu, Activation of nuclear receptors: a perspective from structural genomics, Structure, 11(7) (2003), p. 741-746. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma, J.R. Idle, F.J. Gonzalez, The pregnane X receptor: from bench to bedside, Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol., 4(7) (2008), p. 895-908. [CrossRef]

- J. Huwyler, M.B. Wright, H. Gutmann, J. Drewe, Induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein by the isoxazolyl-penicillin antibiotic flucloxacillin, Curr. Drug Metab., 7(2) (2006), p. 119-126. [CrossRef]

- F. Lakehal, P.M. Dansette, L. Becquemont, E. Lasnier, R. Delelo, P. Balladur, R. Poupon, P.H. Beaune, C. Housset, Indirect cytotoxicity of flucloxacillin toward human biliary epithelium via metabolite formation in hepatocytes, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 14(6) (2001), p. 694-701. [CrossRef]

- T. Kawashiro, K. Yamashita, X.J. Zhao, E. Koyama, M. Tani, K. Chiba, T. Ishizaki, A study on the metabolism of etoposide and possible interactions with antitumor or supporting agents by human liver microsomes, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 286(3) (1998), p. 1294-1300.

- J.S. Lagas, L. Fan, E. Wagenaar, M.L. Vlaming, O. van Tellingen, J.H. Beijnen, A.H. Schinkel, P-glycoprotein (P-gp/Abcb1), Abcc2, and Abcc3 determine the pharmacokinetics of etoposide, Clin. Cancer Res., 16(1) (2010), p. 130-140. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Yang, H.G. Choi, S.J. Lim, M.G. Lee, S.H. Kim, Effects of morin on the pharmacokinetics of etoposide in 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary tumors in female Sprague-Dawley rats, Oncol. Rep., 29(3) (2013), p. 1215-1223. [CrossRef]

- J. Hofman, D. Vagiannis, S. Chen, L. Guo, Roles of CYP3A4, CYP3A5 and CYP2C8 drug-metabolizing enzymes in cellular cytostatic resistance, Chem. Biol. Interact., 340 (2021), p. 109448. [CrossRef]

- C. Martínez, E. García-Martín, R.M. Pizarro, F.J. García-Gamito, J.A. Agúndez, Expression of paclitaxel-inactivating CYP3A activity in human colorectal cancer: implications for drug therapy, Br. J. Cancer, 87(6) (2002), p. 681-686. [CrossRef]

- N.R. Powell, T. Shugg, R.C. Ly, C. Albany, M. Radovich, B.P. Schneider, T.C. Skaar, Life-threatening docetaxel toxicity in a patient with reduced-function CYP3A variants: A case report, Front. Oncol., 11 (2022), p. 809527. [CrossRef]

- S. Sim, J. Bergh, M. Hellström, T. Hatschek, H. Xie, Pharmacogenetic impact of docetaxel on neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer patients, Pharmacogenomics, 19(16) (2018), p. 1259-1268. [CrossRef]

- H. Masuyama, K. Nakamura, E. Nobumoto, Y. Hiramatsu, Inhibition of pregnane X receptor pathway contributes to the cell growth inhibition and apoptosis of anticancer agents in ovarian cancer cells, Int. J. Oncol., 49(3) (2016), p. 1211-1220. [CrossRef]

- H. Masuyama, H. Nakatsukasa, N. Takamoto, Y. Hiramatsu, Down-regulation of pregnane X receptor contributes to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis by anticancer agents in endometrial cancer cells, Mol. Pharmacol., 72(4) (2007), p. 1045-1053. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, J.A. Goldstein, The transcriptional regulation of the human CYP2C genes, Curr. Drug Metab., 10(6) (2009), p. 567-578. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Vilanova-Costa, H.K. Porto, L.C. Pereira, B.P. Carvalho, W.B. Dos Santos, P. Silveira-Lacerda Ede, MDR1 and cytochrome P450 gene-expression profiles as markers of chemosensitivity in human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells treated with cisplatin and Ru(III) metallocomplexes, Biol. Trace Elem. Res., 163(1-2) (2015), p. 39-47. [CrossRef]

- J. Hakkola, C. Bernasconi, S. Coecke, L. Richert, T.B. Andersson, O. Pelkonen, Cytochrome P450 induction and xeno-sensing receptors pregnane X receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, aryl hydrocarbon receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α at the crossroads of toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics, Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 123 (Suppl.5) (2018), p. 42-50. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Ferguson, E.L. LeCluyse, M. Negishi, J.A. Goldstein, Regulation of human CYP2C9 by the constitutive androstane receptor: discovery of a new distal binding site, Mol. Pharmacol., 62(3) (2002), p. 737-746. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Preiss, R. Liu, P. Hewitt, D. Thompson, K. Georgi, L. Badolo, V.M. Lauschke, C. Petersson, Deconvolution of cytochrome P450 induction mechanisms in HepaRG nuclear hormone receptor knockout cells, Drug Metab. Dispos., 49(8) (2021), p. 668-678. [CrossRef]

- P. Wei, J. Zhang, D.H. Dowhan, Y. Han, D.D. Moore, Specific and overlapping functions of the nuclear hormone receptors CAR and PXR in xenobiotic response, Pharmacogenomics J., 2(2) (2002), p. 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, H. Masuyama, E. Nobumoto, G. Zhang, Y. Hiramatsu, The inhibition of constitutive androstane receptor-mediated pathway enhances the effects of anticancer agents in ovarian cancer cells, Biochem. Pharmacol., 90(4) (2014), p. 356-366. [CrossRef]

- B. Goodwin, E. Hodgson, D.J. D'Costa, G.R. Robertson, C. Liddle, Transcriptional regulation of the human CYP3A4 gene by the constitutive androstane receptor, Mol. Pharmacol., 62(2) (2002), p. 359-365. [CrossRef]

- D. Smirlis, R. Muangmoonchai, M. Edwards, I.R. Phillips, E.A. Shephard, Orphan receptor promiscuity in the induction of cytochromes p450 by xenobiotics, J. Biol. Chem., 276(16) (2001), p. 12822-12826. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, L. Li, H. Yang, S.S. Ferguson, M.R. Baer, R.B. Gartenhaus, H. Wang, The constitutive androstane receptor is a novel therapeutic target facilitating cyclophosphamide-based treatment of hematopoietic malignancies, Blood, 121(2) (2013), p. 329-338. [CrossRef]

- S. Ren, J.S. Yang, T.F. Kalhorn, J.T. Slattery, Oxidation of cyclophosphamide to 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and deschloroethylcyclophosphamide in human liver microsomes, Cancer Res., 57(19) (1997), p. 4229-4235.

- S.F. Zhou, Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4, Curr. Drug Metab., 9(4) (2008), p. 310-322. [CrossRef]

- S.P. Rendic, Metabolism and interactions of ivermectin with human cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug transporters, possible adverse and toxic effects. Arch Toxicol. 2021 May;95(5):1535-1546. [CrossRef]

- Y.L. Teo, H.K. Ho, A. Chan, Metabolism-related pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: current understanding, challenges and recommendations, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 79(2) (2015), p. 241-253. [CrossRef]

- A. Didier, F. Loor, The abamectin derivative ivermectin is a potent P-glycoprotein inhibitor, Anticancer Drugs, 7(7) (1996), p. 745-751. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhou, T.M. Li, J.Z. Luo, C.L. Lan, Z.L. Wei, T.H. Fu, X.W. Liao, G.Z. Zhu, X.P. Ye, T. Peng, CYP2C8 suppress proliferation, migration, invasion and sorafenib resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma via PI3K/Akt/p27kip1 axis, J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma, 8 (2021), p. 1323-1338. [CrossRef]

- P.C. Nair, T.B. Gillani, T. Rawling, M. Murray, Differential inhibition of human CYP2C8 and molecular docking interactions elicited by sorafenib and its major N-oxide metabolite, Chem. Biol. Interact., 338 (2021), p. 109401. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghassabian, T. Rawling, F. Zhou, M.R. Doddareddy, B.N. Tattam, D.E. Hibbs, R.J. Edwards, P.H. Cui, M. Murray, Role of human CYP3A4 in the biotransformation of sorafenib to its major oxidized metabolites, Biochem. Pharmacol., 84(2) (2012), p. 215-223. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Guengerich, A history of the roles of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the toxicity of drugs, Toxicol. Res., 37(1) (2020), p. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- B.L. Salerni, D.J. Bates, T.C. Albershardt, C.H. Lowrey, A. Eastman, Vinblastine induces acute, cell cycle phase-independent apoptosis in some leukemias and lymphomas and can induce acute apoptosis in others when Mcl-1 is suppressed, Mol. Cancer Ther., 9(4) (2010), p. 791-802. [CrossRef]

- X.R. Zhou-Pan, E. Sérée, X.J. Zhou, M. Placidi, P. Maurel, Y. Barra, R. Rahmani, Involvement of human liver cytochrome P450 3A in vinblastine metabolism: drug interactions, Cancer Res., 53(21) (1993), p. 5121-5126.

- J.B. Dennison, P. Kulanthaivel, R.J. Barbuch, J.L. Renbarger, W.J. Ehlhardt, S.D. Hall, Selective metabolism of vincristine in vitro by CYP3A5. Drug Metab. Dispos., 34(8) (2006), p. 1317-1327. [CrossRef]

- N. Nebot, S. Crettol, F. d'Esposito, B. Tattam, D.E. Hibbs, M. Murray, Participation of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 in the N-demethylation of imatinib in human hepatic microsomes, Br. J. Pharmacol., 161(5) (2010), p. 1059-1069. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Filppula, M. Neuvonen, J. Laitila, P.J. Neuvonen, J.T. Backman, Autoinhibition of CYP3A4 leads to important role of CYP2C8 in imatinib metabolism: variability in CYP2C8 activity may alter plasma concentrations and response, Drug Metab. Dispos., 41(1) (2013), p. 50-59. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhao, X. Li, Y. Chen, J. Du, X. Chen, D. Wang, L. Wang, S. Zhao, C. Wang, Q. Meng, H. Sun, K. Liu, J. Wu, Risk assessment and molecular mechanism study of drug-drug interactions between rivaroxaban and tyrosine kinase inhibitors mediated by CYP2J2/3A4 and BCRP/P-gp, Front. Pharmacol., 13 (2022), p. 914842. [CrossRef]

- A,M, Filppula, P.J. Neuvonen, J.T. Backman, In vitro assessment of time-dependent inhibitory effects on CYP2C8 and CYP3A activity by fourteen protein kinase inhibitors, Drug Metab. Dispos., 42(7) (2014), p. 1202-1209. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Filppula, T.M. Mustonen, J.T. Backman, In vitro screening of six protein kinase inhibitors for time-dependent inhibition of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4: Possible implications with regard to drug-drug interactions, Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 123(6) (2018), p. 739-748. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Latham, D.S. Oskin, R.D. Crouch, M.J. Vergne, K.D. Jackson, Cytochromes P450 2C8 and 3A catalyze the metabolic activation of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 35(9) (2022), p. 1467-1481. [CrossRef]

- N. Eliyatkın, E. Yalçın, B. Zengel, S. Aktaş, E. Vardar, Molecular classification of breast carcinoma: From traditional, old-fashioned way to a new age, and a new way, J. Breast Health, 11(2) (2015), p. 59-66. [CrossRef]

- M.H. Zhang, H.T. Man, X.D. Zhao, N. Dong, S.L. Ma, Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer molecular signatures and therapeutic potentials (Review), Biomed. Rep., 2(1) (2014), p. 41-52. [CrossRef]

- V. Makker, H. MacKay, I. Ray-Coquard, D.A. Levine, S.N. Westin, D. Aoki, A. Oaknin, Endometrial cancer, Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers, 7(1) (2021), p. 88. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Hecht, G.L. Mutter, Molecular and pathologic aspects of endometrial carcinogenesis, J. Clin. Oncol., 24(29) (2006), 4783-4791. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Brinton, B. Trabert, G.L. Anderson, R.T. Falk, A.S. Felix, B.J. Fuhrman, M.L. Gass, L.H. Kuller, R.M. Pfeiffer, T.E. Rohan, H.D. Strickler, X. Xu, N. Wentzensen, Serum estrogens and estrogen metabolites and endometrial cancer risk among postmenopausal women, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 25(7) (2016), p. 1081-1089. [CrossRef]

- U.M. Zamwar, A.P. Anjankar, Aetiology, epidemiology, histopathology, classification, detailed evaluation, and treatment of ovarian cancer, Cureus, 14(10) (2022), e30561. [CrossRef]

- F. Modugno, R. Laskey, A.L. Smith, C.L. Andersen, P. Haluska, S. Oesterreich, Hormone response in ovarian cancer: time to reconsider as a clinical target? Endocr. Relat. Cancer, 19(6) (2012), R255-R279. [CrossRef]

- F. Shen, X. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Ding, Q. Chen, Hormone receptors expression in ovarian cancer taking into account menopausal status: a retrospective study in Chinese population, Oncotarget, 8(48) (2017), p. 84019-84027. [CrossRef]

- B. Luo, D. Yan, H. Yan, J. Yuan, Cytochrome P450: Implications for human breast cancer, Oncol. Lett., 22(1) (2021), p. 548. [CrossRef]

- J. Wunder, D. Pemp, A. Cecil, M. Mahdiani, R. Hauptstein, K. Schmalbach, L.N. Geppert, K. Ickstadt, H.L. Esch, T. Dandekar, L. Lehmann, Influence of breast cancer risk factors on proliferation and DNA damage in human breast glandular tissues: role of intracellular estrogen levels, oxidative stress and estrogen biotransformation, Arch. Toxicol., 96(2) (2022), p. 673-687. [CrossRef]

- H. Piotrowska, M. Kucinska, M. Murias, Expression of CYP1A1, CYP1B1 and MnSOD in a panel of human cancer cell lines, Mol. Cell. Biochem., 383(1-2) (2013), p. 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Y.K. Leung, K.M. Lau, J. Mobley, Z. Jiang, S.M. Ho, Overexpression of cytochrome P450 1A1 and its novel spliced variant in ovarian cancer cells: alternative subcellular enzyme compartmentation may contribute to carcinogenesis, Cancer Res., 65(9) (2005), p. 3726-3734. [CrossRef]

- A.E. Cribb, M.J. Knight, D. Dryer, J. Guernsey, K. Hender, M. Tesch, T.M. Saleh, Role of polymorphic human cytochrome P450 enzymes in estrone oxidation, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 15(3) (2006), p. 551-558. [CrossRef]

- V. Kerlan, Y. Dreano, J.P. Bercovici, P.H. Beaune, H.H. Floch, F. Berthou, Nature of cytochromes P450 involved in the 2-/4-hydroxylations of estradiol in human liver microsomes, Biochem. Pharmacol., 44(9) (1992), p. 1745-1756. [CrossRef]

- E. Cavalieri, E. Rogan, The 3,4-quinones of estrone and estradiol are the initiators of cancer whereas resveratrol and N-acetylcysteine are the preventers, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22(15) (2021), p. 8238. [CrossRef]

- M. Gupta, A. McDougal, S. Safe, Estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities of 16alpha- and 2-hydroxy metabolites of 17beta-estradiol in MCF-7 and T47D human breast cancer cells, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 67(5-6) (1998), p. 413-419. [CrossRef]

- E. Sawicka, A. Długosz, The role of 17β-estradiol metabolites in chromium-induced oxidative stress, Adv. Clin. Exp. Med., 26(2) (2017), p. 215-221. [CrossRef]

- H. Samavat, M.S. Kurzer, Estrogen metabolism and breast cancer, Cancer Lett., 356(Pt A) (2015), p. 231-243. [CrossRef]

- S. Verenich, P.M. Gerk, Therapeutic promises of 2-methoxyestradiol and its drug disposition challenges, Mol. Pharm., 7(6) (2010), p. 2030-2039. [CrossRef]

- C. Guillemette, a. Bélanger, J. Lépine, Metabolic inactivation of estrogens in breast tissue by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes: an overview, Breast Cancer Res., 6(6) (2004), p. 246-254. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Yager, Mechanisms of estrogen carcinogenesis: The role of E2/E1-quinone metabolites suggests new approaches to preventive intervention--A review, Steroids, 99(Pt A) (2015), p. 56-60. [CrossRef]

- F. Lu, M. Zahid, M. Saeed, E.L. Cavalieri, E.G. Rogan, Estrogen metabolism and formation of estrogen-DNA adducts in estradiol-treated MCF-10F cells. The effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induction and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 105(1-5) (2007), p. 150-158. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Fuhrman, C. Schairer, M.H. Gail, J. Boyd-Morin, X. Xu, L.Y. Sue, S.S. Buys, C. Isaacs, L.K. Keefer, T.D. Veenstra, C.D. Berg, R.N. Hoover, R.G. Ziegler, Estrogen metabolism and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 104(4) (2012), p. 326-339. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Lavigne, J.E. Goodman, T. Fonong, S. Odwin, P. He, D.W. Roberts, J.D. Yager, The effects of catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition on estrogen metabolite and oxidative DNA damage levels in estradiol-treated MCF-7 cells, Cancer Res., 61(20) (2001), p. 7488-7494.

- C. Lin, D.R. Chen, S.J. Kuo, C.Y. Feng, D.R. Chen, W.C. Hsieh, P.H. Lin, Profiling of protein adducts of estrogen quinones in 5-year survivors of breast cancer without recurrence, Cancer Control., 29 (2022), p. 10732748221084196. [CrossRef]

- B. Trabert, A.M. Geczik, D.C. Bauer, D.S.M. Buist, J.A. Cauley, R.T. Falk, G.L. Gierach, T.F. Hue, J.V. Lacey Jr, A.Z. LaCroix, K.A. Michels, J.A. Tice, X. Xu, L.A. Brinton, C.M. Dallal, Association of endogenous pregnenolone, progesterone, and related metabolites with risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers in postmenopausal women: The B∼FIT cohort, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 30(11) (2021), p. 2030-2037. [CrossRef]

- M. Zahid, C.L. Beseler, J.B. Hall, T. LeVan, E.L. Cavalieri, E.G. Rogan, Unbalanced estrogen metabolism in ovarian cancer, Int. J. Cancer, 134(10) (2014), p. 2414-2423. [CrossRef]

- E. Taioli, H.L. Bradlow, S.V. Garbers, D.W. Sepkovic, M.P. Osborne, J. Trachman, S. Ganguly, S.J. Garte, Role of estradiol metabolism and CYP1A1 polymorphisms in breast cancer risk, Cancer Detect. Prev., 23(3) (1999), p. 232-237. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramírez, C. Castro-Hernández, R. Pérez-Morales, L. Casas-Ávila, R.M. de Lorena, A. Salazar-Piña, J. Rubio, Pathological characteristics, survival, and risk of breast cancer associated with estrogen and xenobiotic metabolism polymorphisms in Mexican women with breast cancer, Cancer Causes Control., 32(4) (2021), p. 369-378. [CrossRef]

- V. Singh, N. Rastogi, A. Sinha, A. Kumar, N. Mathur, M.P. Singh, A study on the association of cytochrome-P450 1A1 polymorphism and breast cancer risk in north Indian women, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 101(7) (2007), p. 73-81. [CrossRef]

- M. Okobia, C. Bunker, J. Zmuda, C. Kammerer, V. Vogel, E. Uche, S. Anyanwu, E. Ezeome, R. Ferrell, L. Kuller, Cytochrome P4501A1 genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in Nigerian women, Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 94(3) (2005), p. 285-293. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, L. Gu, B. Qian, X. Hao, W. Zhang, Q. Wei, K. Chen, Association of genetic polymorphisms of ER-alpha and the estradiol-synthesizing enzyme genes CYP17 and CYP19 with breast cancer risk in Chinese women, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 114(2) (2009), p. 327-338. [CrossRef]

- D.F. Han, X. Zhou, M.B. Hu, W. Xie, Z.F. Mao, D.E. Chen, F. Liu, F. Zheng, Polymorphisms of estrogen-metabolizing genes and breast cancer risk: a multigenic study, Chin. Med. J. (Engl), 118(18) (2005), p. 1507-1516.

- B.M. Tüzüner, T. Oztürk, H.I. Kisakesen, S. Ilvan, C. Zerrin, O. Oztürk, T. Isbir, CYP17 (T-34C) and CYP19 (Trp39Arg) polymorphisms and their cooperative effects on breast cancer susceptibility, In Vivo, 24(1) (2010), p. 71-74.

- M. McGrath, S.E. Hankinson, L. Arbeitman, G.A. Colditz, D.J. Hunter, I. De Vivo, Cytochrome P450 1B1 and catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms and endometrial cancer susceptibility, Carcinogenesis, 25(4) (2004), p. 559-565. [CrossRef]

- T.N. Sergentanis, K.P. Economopoulos, S. Choussein, N.F. Vlahos, Cytochrome P450 1A1 gene polymorphisms and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011 Feb;21(2):323-31. [CrossRef]

- J.B. Ramirez Sabio, J.V. Sorli, R. Barragan, F.-C. Rebeca, E.M. Asensio, D. Cjrella, Effect of the polymorphism rs2470893 of the CYP1A1 gene on ovarian and endometrial cancer in Mediterranean women, Ann. Oncol., 29(Suppl. 8) (2018), viii6.

- J.Y Liu, Y. Yang, Z.Z. Liu, J.J. Xie, Y.P. Du, W. Wang, Association between the CYP1B1 polymorphisms and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis, Mol. Genet. Genomics, 290(2) (2015), p. 739-765. [CrossRef]

- K. Gajjar, G. Owens, M. Sperrin, P.L. Martin-Hirsch, F.L. Martin, Cytochrome P1B1 (CYP1B1) polymorphisms and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis, Toxicology, 302(2-3) (2012), p. 157-162. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, L. Feng, M. Lou, X. Deng, C. Liu, L. Li, The ovarian carcinoma risk with the polymorphisms of CYP1B1 come from the positive selection, Am. J. Transl. Res., 13(5) (2021), p. 4322-4341.

- M.B. Culp, I. Soerjomataram, J.A. Efstathiou, F. Bray, A. Jemal, Recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates, Eur. Urol., 77(1) (2020), p. 38-52. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Y. Zhou, Z. Xing, R.K. Sah, J. Hu, H. Hu, Androgen metabolism and response in prostate cancer anti-androgen therapy resistance, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23(21) (2022), p. 13521. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, P.H. Lin, S.J. Freedland, J.T. Chi, Metabolic response to androgen deprivation therapy of prostate cancer, Cancers (Basel), 16(11) (2024), p. 1991. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Auchus, Steroid 17-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase deficiencies, genetic and pharmacologic, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 165(Pt A) (2017), p. 71-78. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Chung, J. Picado-Leonard, M. Haniu, m. Bienkowski, P.F. Hall, J.E. Shively, W.L. Miller, Cytochrome P450c17 (steroid 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase): cloning of human adrenal and testis cDNAs indicates the same gene is expressed in both tissues, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 84(2) (1987), p. 407-411. [CrossRef]

- T. Suzuki, H. Sasano, J. Takeyama, C. Kaneko, W.A. Freije, B.R. Carr, W.E. Rainey, Developmental changes in steroidogenic enzymes in human postnatal adrenal cortex: immunohistochemical studies, Clin. Endocrinol (Oxf), 53(6) (2000), p. 739-747. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Mostaghel, K.R. Solomon, K. Pelton, M.R. Freeman, R.B. Montgomery, Impact of circulating cholesterol levels on growth and intratumoral androgen concentration of prostate tumors, PLoS One 7(1) (2012), p. e30062. [CrossRef]

- A. Giatromanolaki, V. Fasoulaki, D. Kalamida, A. Mitrakas, C. Kakouratos, T. Lialiaris, M.I. Koukourakis, CYP17A1 and androgen-receptor expression in prostate carcinoma tissues and cancer cell lines, Curr. Urol., 13(3) (2019), p. 157-165. [CrossRef]

- M. Sakai, D.B. Martinez-Arguelles, A.G. Aprikian, A.M. Magliocco, V. Papadopoulos, De novo steroid biosynthesis in human prostate cell lines and biopsies, Prostate, 76(6) (2016), p. 575-587. [CrossRef]

- K.H. Chang, C.E. Ercole, N. Sharifi, Androgen metabolism in prostate cancer: from molecular mechanisms to clinical consequences, Br. J. Cancer, 111(7) (2014), p. 1249-1254. [CrossRef]

- S. Crnalic, E. Hörnberg, P. Wikström, U.H. Lerner, A. Tieva, O. Svensson, A. Widmark, A. Bergh, Nuclear androgen receptor staining in bone metastases is related to a poor outcome in prostate cancer patients, Endocr. Relat. Cancer, 17(4) (2010), p. 885-895. [CrossRef]

- N. Sharifi. Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation in castration-resistant prostate cancer, Endocrinology, 154(11) (2013), p. 4010-4017. [CrossRef]

- K.H.Chang, R. Li, M. Papari-Zareei, L. Watumull, Y.D. Zhao, R.J. Auchus, N. Sharifi, Dihydrotestosterone synthesis bypasses testosterone to drive castration-resistant prostate cancer, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 108(33) (2011), p. 13728-13733. [CrossRef]

- G.L. Varaprasad, V.K. Gupta, K. Prasad, E. Kim, M.B. Tej, P. Mohanty, H.K. Verma, G.S.R. Raju, L. Bhaskar, Y.S. Huh, Recent advances and future perspectives in the therapeutics of prostate cancer, Exp. Hematol. Oncol., 12(1) (2023), p. 80. [CrossRef]

- H. Bolek, S.C. Yazgan, E. Yekedüz, M.D. Kaymakcalan, R.R. McKay, S. Gillessen, Y. Ürün, Androgen receptor pathway inhibitors and drug-drug interactions in prostate cancer, ESMO Open, 9(11) (2024), p. 103736. [CrossRef]

- T.K. Le, Q.H. Duong, V. Baylot, C. Fargette, M. Baboudjian, L. Colleaux, D. Taïeb, P. Rocchi, Castration-resistant prostate cancer: From uncovered resistance mechanisms to current treatments, Cancers (Basel), 15(20) (2023), p. 5047. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Montgomery, E.A. Mostaghel, R. Vessella, D.L. Hess, T.F. Kalhorn, C.S. Higano, L.D. True, P.S. Nelson, Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth, Cancer Res., 68(11) (2008), p. 4447-4454. [CrossRef]

- C. Padmakar Darne, U. Velaparthi, M. Saulnier, D. Frennesson, P. Liu, A. Huang, J. Tokarski, A. Fura, T. Spires, J. Newitt, V.M. Spires, M.T. Obermeier, P.A. Elzinga, M.M. Gottardis, L. Jayaraman, G.D. Vite, A. Balog, The discovery of BMS-737 as a potent, CYP17 lyase-selective inhibitor for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 75 (2022), p. 128951. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Wróbel, O. Rogova, K. Sharma, M.N. Rojas Velazquez, A.V. Pandey, F.S. Jørgensen, F.S. Arendrup, K.L. Andersen, F. Björkling, Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of novel non-steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors as potential prostate cancer agents, Biomolecules, 12(2) (2022), p. 165. [CrossRef]

- S.A.H. Abdi, A. Ali, S.F. Sayed, M.J. Ahsan, A. Tahir, W. Ahmad, S. Shukla, A. Ali, Morusflavone, a new therapeutic candidate for prostate cancer by CYP17A1 inhibition: Exhibited by molecular docking and dynamics simulation, Plants (Basel), 10(9) (2021), p. 1912. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Latysheva, V.A. Zolottsev, V.S. Pokrovsky, I.I. Khan, A.Y. Misharin, Novel nitrogen containing steroid derivatives for prostate cancer treatment, Curr. Med. Chem., 28(40) (2021), p. 8416-8432. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Wróbel, O. Rogova, K.L. Andersen, R. Yadav, S. Brixius-Anderko, E.E. Scott, L. Olsen, F.S. Jørgensen, F. Björkling, Discovery of novel non-steroidal cytochrome P450 17A1 inhibitors as potential prostate cancer agents, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(14) (2020), p. 4868. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Wróbel, F.S. Jørgensen, A.V. Pandey, A. Grudzińska, K. Sharma, J. Yakubu, F. Björkling, Non-steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors: Discovery and assessment, J. Med. Chem., 66(10) (2023), p. 6542-6566. [CrossRef]

- L. Yin, Q. Hu, CYP17 inhibitors--abiraterone, C17,20-lyase inhibitors and multi-targeting agents, Nat Rev Urol. 2014 Jan;11(1):32-42. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Rowlands, S.E. Barrie, F. Chan, J. Houghton, M. Jarman, R. McCague, G.A. Potter, Esters of 3-pyridylacetic acid that combine potent inhibition of 17 alpha-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase (cytochrome P45017 alpha) with resistance to esterase hydrolysis, J. Med. Chem., 38(21) (1995), 4191-4197. [CrossRef]

- J.S. de Bono, C.J. Logothetis, A. Molina, K. Fizazi, S. North, L. Chu, K.N. Chi, R.J. Jones, O.B. Goodman, Jr, F. Saad, J.N. Staffurth, P. Mainwaring, S. Harland, T.W. Flaig, T.E. Hutson, T. Cheng, H. Patterson, J.D. Hainsworth, C.J. Ryan, C.N. Sternberg, S.L. Ellard, A. Fléchon, M. Saleh, M. Scholz, E. Efstathiou, A. Zivi, D. Bianchini, Y. Loriot, N. Chieffo, T. Kheoh, C.M. Haqq, H.I. Scher; COU-AA-301 Investigators, Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer, N. Engl. J. Med., 364(21) (2011), p. 1995-2005. [CrossRef]

- E. Efstathiou, M. Titus, D. Tsavachidou, V. Tzelepi, S. Wen, A. Hoang, A. Molina, N. Chieffo, L.A. Smith, M. Karlou, P. Troncoso, C.J. Logothetis, Effects of abiraterone acetate on androgen signaling in castrate-resistant prostate cancer in bone, J. Clin. Oncol., 30(6) (2012), p. 637-643. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Norris, S.J. Ellison, J.G. Baker, D.B. Stagg, S.E. Wardell, S. Park, H.M. Alley, R.M. Baldi, A. Yllanes, K.J. Andreano, J.P. Stice, S.A. Lawrence, J.R. Eisner, D.K. Price, W.R. Moore, W.D. Figg, D.P. McDonnell, Androgen receptor antagonism drives cytochrome P450 17A1 inhibitor efficacy in prostate cancer, J. Clin. Invest., 127(6) (2017), p. 2326-2338. [CrossRef]

- H. Mehralitabar, A.S. Ghasemi, J. Gholizadeh, Abiraterone and D4, 3-keto Abiraterone binding to CYP17A1, a structural comparison study by molecular dynamic simulation, Steroids, 167 (2021), p. 108799. [CrossRef]

- E.J.Y. Cheong, P.C. Nair, R.W.Y. Neo, H.T. Tu, F. Lin, E. Chiong, K. Esuvaranathan, H. Fan, R.Z. Szmulewitz, C.J. Peer, W.D. Figg, C.L.L. Chai, J.O. Miners, E.C.Y. Chan, Slow-, tight-binding inhibition of CYP17A1 by abiraterone redefines its kinetic selectivity and dosing regimen, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 374(3) (2020), p. 438-451. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhang, Q. Cheng, Z. Ou, J.H. Lee, M. Xu, U. Kochhar, S. Ren, M. Huang, B.R. Pflug, W. Xie, Pregnane X receptor as a therapeutic target to inhibit androgen activity, Endocrinology, 151(12) (2010), p. 5721-5729. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Salamat, E.M. Ayala, C.J. Huang, F.S. Wilbanks, R.C. Knight, B.T. Akingbemi, S.R. Pondugula, Pregnenolone 16-alpha carbonitrile, an agonist of rodent pregnane X receptor, regulates testosterone biosynthesis in rodent Leydig cells, J. Xenobiot., 14(3) (2024), p. 1256-1267. [CrossRef]

- A. Gsur, E. Feik, S. Madersbacher, Genetic polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk, World J. Urol., 21(6) (2004), p. 414-423. [CrossRef]

- M. Izmirli, B. Arikan, Y. Bayazit, D. Alptekin, Associations of polymorphisms in HPC2/ELAC2 and SRD5A2 genes with benign prostate hyperplasia in Turkish men, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev., 12 (2011), p. 731-733.

- M.S. Cicek, D.V. Conti, A. Curran, P.J. Neville, P.L. Paris, G. Casey, J.S. Witte, Association of prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness to androgen pathway genes: SRD5A2, CYP17, and the AR, Prostate, 59(1) (2004), p. 69-76. [CrossRef]

- I.H. Onen, A. Ekmekci, M. Eroglu, F. Polat, H. Biri, The association of 5alpha-reductase II (SRD5A2) and 17 hydroxylase (CYP17) gene polymorphisms with prostate cancer patients in the Turkish population, DNA Cell Biol., 26(2) (2007), p. 100-107. [CrossRef]

- N.E. Allen, M.S. Forrest, T.J. Key, The association between polymorphisms in the CYP17 and 5alpha-reductase (SRD5A2) genes and serum androgen concentrations in men, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 10(3) (2001), p. 185-189.

- S. Lindström, F. Wiklund, H.O. Adami, K.A. Bälter, J. Adolfsson, H. Grönberg, Germ-line genetic variation in the key androgen-regulating genes androgen receptor, cytochrome P450, and steroid-5-alpha-reductase type 2 is important for prostate cancer development, Cancer Res., 66(22) (2006), p. 11077-11083. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Sobti, L. Gupta, S.K. Singh, A. Seth, P. Kaur, H. Thakur, Role of hormonal genes and risk of prostate cancer: gene-gene interactions in a North Indian population, Cancer Genet. Cytogenet., 185(2) (2008), p. 78-85. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yamada, M. Watanabe, M. Murata, M. Yamanaka, Y. Kubota, H. Ito, T. Katoh, J. Kawamura, R. Yatani, T. Shiraishi, Impact of genetic polymorphisms of 17-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450 (CYP17) and steroid 5alpha-reductase type II (SRD5A2) genes on prostate-cancer risk among the Japanese population, Int. J. Cancer, 92(5) (2001), p. 683-686. [CrossRef]

- M. Murata, M. Watanabe, M. Yamanaka, Y. Kubota, H. Ito, M. Nagao, T. Katoh, T. Kamataki, J. Kawamura, R. Yatani, T. Shiraishi, Genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2E1, glutathione S-transferase (GST) M1 and GSTT1 and susceptibility to prostate cancer in the Japanese population, Cancer Lett., 165(2) (2001), p. 171-177. [CrossRef]

- M. Koda, M. Iwasaki, Y. Yamano, X. Lu, T. Katoh, Association between NAT2, CYP1A1, and CYP1A2 genotypes, heterocyclic aromatic amines, and prostate cancer risk: a case control study in Japan, Environ. Health Prev. Med., 22(1) (2017), p. 72. [CrossRef]

- B.L. Chang, S.L. Zheng, S.D. Isaacs, A. Turner, G.A. Hawkins, K.E. Wiley, E.R. Bleecker, P.C. Walsh , D.A. Meyers, W.B. Isaacs, J. Xu, Polymorphisms in the CYP1B1 gene are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer, Br. J. Cancer, 89(8) (2003), p. 1524-1529. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Cicek, X. Liu, G. Casey, J.S. Witte, Role of androgen metabolism genes CYP1B1, PSA/KLK3, and CYP11alpha in prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 14(9) (2005), p. 2173-2177. [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Liu, Y. Yang, Z.Z. Liu, J.J. Xie, Y.P. Du, W. Wang, Association between the CYP1B1 polymorphisms and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis, Mol. Genet. Genomics, 290(2) (2015), p. 739-765. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Gu, G.X. Li, Y. Zhu, H. Xu, Y. Zhu, X.J. Qin, D. Bo, D.W. Ye, A single nucleotide polymorphism in CYP1B1 leads to differential prostate cancer risk and telomere length, J. Cancer, 9(2) (2018), p. 269-274. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Gu, X.J. Qin, Y.Y. Qu, Y. Zhu, F.N. Wan, G.M. Zhang, L.J. Sun, Y. Zhu, D.W. Ye, Genetic variants of the CYP1B1 gene as predictors of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer patients, Medicine (Baltimore), 95(27) (2016), p. e4066. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu, H. Liu, X. Wang, J. Lu, H. Zhang, S. Wang, W. Yang, Associations of CYP1 polymorphisms with risk of prostate cancer: an updated meta-analysis, Biosci. Rep., 39(3) (2019), p.BSR20181876. [CrossRef]

- M. Vilčková, M. Škereňová, D. Dobrota, P. Kaplán, J. Jurečeková, J. Kliment, M. Híveš, R. Dušenka, D. Evin, M. Knoško Brožová, M. Kmeťová Sivoňová, Polymorphisms in the gene encoding CYP1A2 influence prostate cancer risk and progression, Oncol. Lett. 25(2) (2023), p. 85. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Plummer, D.V. Conti, P.L. Paris, A.P. Curran, G. Casey, J.S. Witte, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genotypes, haplotypes, and risk of prostate cancer, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 12((9) (2003), p. 928-932.

- Y. Liang, W. Han, H. Yan, Q. Mao, Association of CYP3A5*3 polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk: A meta-analysis, J. Cancer Res. Ther., 14(Suppl) (2018), p. S463-S467. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Bellah, M.A. Salam, S.M.S. Billah, M.R. Karim, Genetic association in CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genes elevate the risk of prostate cancer, Ann. Hum. Biol., 50(1) (2023), p. 63-74. [CrossRef]

- M.H. Vaarala, H. Mattila, P. Ohtonen, T.L. Tammela, T.K. Paavonen, J. Schleutker, The interaction of CYP3A5 polymorphisms along the androgen metabolism pathway in prostate cancer, Int. J. Cancer, 122(11) (2008), p. 2511-2516. [CrossRef]

- A. Loukola, M. Chadha, S.G. Penn, D. Rank, D.V. Conti, D. Thompson, M. Cicek, B. Love, V. Bivolarevic, Q. Yang, Y. Jiang, D.K. Hanzel, K. Dains, P.L. Paris, G. Casey, J.S. Witte, Comprehensive evaluation of the association between prostate cancer and genotypes/haplotypes in CYP17A1, CYP3A4, and SRD5A2, Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 12(4) (2004), p. 321-332. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Villeneuve, V, Pichette, Cytochrome P450 and liver diseases, Curr. Drug Metab., 5(3) (2004), p. 273-282. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bao, M. Phan, J. Zhu, X. Ma, J.E. Manautou, X.B. Zhong, Alterations of cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism during liver repair and regeneration after acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice, Drug Metab. Dispos., 50(5) (2022), p. 694-703. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bao, P. Wang, X. Shao, J. Zhu, J. Xiao, J. Shi, L. Zhang, H.J. Zhu, X. Ma, J.E. Manautou, X.B. Zhong, Acetaminophen-induced liver injury alters expression and activities of cytochrome P450 enzymes in an age-dependent manner in mouse liver, Drug Metab. Dispos., 48(5) (2020), p. 326-336. [CrossRef]

- A. Michaut, C. Moreau, M.A. Robin, B. Fromenty, Acetaminophen-induced liver injury in obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Liver Int., 34(7) (2014), p. e171-e179. [CrossRef]

- K.E. Thummel, J.T. Slattery, H. Ro, J.Y. Chien, S.D. Nelson, K.E. Lown, P.B. Watkins, Ethanol and production of the hepatotoxic metabolite of acetaminophen in healthy adults, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther., 67(6) (2000), p. 591-599. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, R. Cheng, H. He, K. Ding, R. Zhang, Y. Chai, Q. Yu, X. Huang, L. Zhang, Z. Jiang, 8-methoxypsoralen protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury by antagonising Cyp2e1 in mice, Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 741 (2023), p. 109617. [CrossRef]

- W. Yang, Z. Liang, C. Wen, X. Jiang, L. Wang, Silymarin protects against acute liver injury induced by acetaminophen by downregulating the expression and activity of the CYP2E1 enzyme, Molecules, 27(24) (2022), p. 8855. [CrossRef]

- B. Speed, H.Z. Bu, W.F. Pool, G.W. Peng, E.Y. Wu, S. Patyna, C. Bello, P. Kang, Pharmacokinetics, distribution, and metabolism of [14C]sunitinib in rats, monkeys, and humans, Drug Metab. Dispos., 40(3) (2012), p. 539-555. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, F. Xiao, Z. Feng, M. Li, L. Kong, L. Huang, Y. Wei, H. Li, F. Liu, H. Zhang, W. Zhang, Sunitinib facilitates metastatic breast cancer spreading by inducing endothelial cell senescence, Breast Cancer Res., 22(1) (2020), p. 103. [CrossRef]

- G.M. Amaya, R. Durandis, D.S. Bourgeois, J.A. Perkins, A.A. Abouda, K.J. Wines, M. Mohamud, S.A. Starks, R.N. Daniels, K.D. Jackson, Cytochromes P450 1A2 and 3A4 catalyze the metabolic activation of sunitinib, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 31(7) (2018), p. 570-584. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Burnham, A.A. Abouda, J.E. Bissada, D.T. Nardone-White, J.L. Beers, J. Lee, M.J. Vergne, K.D. Jackson, Interindividual variability in cytochrome P450 3A and 1A activity influences sunitinib metabolism and bioactivation, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 35(5) (2022), p. 792-806. [CrossRef]

- S. Castellino, M. O'Mara, K. Koch, D.J. Borts, G.D. Bowers, C. MacLauchlin, Human metabolism of lapatinib, a dual kinase inhibitor: implications for hepatotoxicity, Drug Metab. Dispos., 40(1) (2012), p. 139-150. [CrossRef]

- J.K. Towles, R.N. Clark, M.D. Wahlin, V. Uttamsingh, A.E. Rettie, K.D. Jackson, Cytochrome P450 3A4 and CYP3A5-catalyzed bioactivation of lapatinib, Drug Metab. Dispos., 44(10) (2016), p. 1584-1597. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, X. Li, Y. Li, X. He, M. Bryant, X. Qin, F. Li, J.E. Seo, X. Guo, N. Mei, L. Guo, The involvement of hepatic cytochrome P450s in the cytotoxicity of lapatinib, Toxicol. Sci., 197(1) (2023), p. 69-78. [CrossRef]

- G. García-Lainez, I. Vayá, M.P. Marín, M.A. Miranda, I. Andreu, In vitro assessment of the photo(geno)toxicity associated with lapatinib, a tyrosine knase inhibitor, Arch. Toxicol., 95(1) (2021), p. 169-178. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, M. Zhao, P. He, M. Hidalgo, S.D. Baker, Differential metabolism of gefitinib and erlotinib by human cytochrome P450 enzymes, Clin. Cancer Res., 13(12) (2007), p. 3731-3737. [CrossRef]

- D. McKillop, A.D. McCormick, A. Millar, G.S. Miles, P.J. Phillips, M. Hutchison, Cytochrome P450-dependent metabolism of gefitinib, Xenobiotica, 35(1) (2005), p. 39-50. [CrossRef]

- M. El Ouardi, L. Tamarit, I. Vayá, M.A. Miranda, I. Andreu, Cellular photo(geno)toxicity of gefitinib after biotransformation, Front. Pharmacol., 14 (2023), p. 1208075. [CrossRef]

- D.Y. Kim, K.H. Han, Epidemiology and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma, Liver Cancer 1 (2012), p. 2–14. [CrossRef]

- S. Caldwell, S.H. Park, The epidemiology of hepatocellular cancer: From the perspectives of public health problem to tumor biology, J. Gastroenterol., (2009), 44, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Y.J. Chu, H.I. Yang, H.C. Wu, J. Liu, L.Y. Wang, S.N. Lu, M.H. Lee, C.L. Jen, S.L. You, R.M. Santella, C.J. Chen, Aflatoxin B1 exposure increases the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers, Int. J. Cancer, 141(4) (2017), p. 711-720. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhu, Y. Ma, J. Liang, Z. Wei, M. Li, Y. Zhang, M. Liu, H. He, C. Qu, J. Cai, X. Wang, Y. Zeng, Y. Jiao, AHR mediates the aflatoxin B1 toxicity associated with hepatocellular carcinoma, Signal Transduct. Target Ther., 6(1) (2021), p. 299. [CrossRef]

- L. Silvestri, L. Sonzogni, A. De Silvestri, C. Gritti, L. Foti, C. Zavaglia, M. Leveri, A. Cividini, M.U. Mondelli, E. Civardi, E.M. Silini, CYP enzyme polymorphisms and susceptibility to HCV-related chronic liver disease and liver cancer, Int. J. Cancer, 104(3) (2003), p. 310-317. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Agúndez, M. Olivera, J.M. Ladero, A. Rodriguez-Lescure, M.C. Ledesma, M. Diaz-Rubio, U.A. Meyer, J. Benítez, Increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in NAT2-slow acetylators and CYP2D6-rapid metabolizers, Pharmacogenetics, 6(6) (1996), p. 501-12. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, Q. Wen, S.F. Li, Y.F. Zhang, N. Gao, X. Tian, Y. Fang, J. Gao, M.Z. Cui, X.P. He, L.J. Jia, H. Jin, H.L. Qiao, Significant change of cytochrome P450s activities in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, Oncotarget, 31 (2016), p. 50612-50623. [CrossRef]

- J. Mochizuki, S. Murakami, A. Sanjo, I. Takagi, S. Akizuki, A. Ohnishi, Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 20(8) (2005), p. 1191-1197. [CrossRef]

- G. Hu, F. Gao, G. Wang, Y. Fang, Y. Guo, J. Zhou, Y. Gu, C. Zhang, N. Gao, Q. Wen, H. Qiao, Use of proteomics to identify mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma with the CYP2D6*10 polymorphism and identification of ANGPTL6 as a new diagnostic and prognostic biomarker, J. Transl. Med., 19(1) (2021), p. 359. [CrossRef]

- B. de Jesus Brait, S.P. da Silva Lima, F.L. Aguiar, R. Fernandes-Ferreira R, C.I.F. Oliveira-Brancati, J.A.M.L. Ferraz, G.D. Tenani, M.A. de Souza Pinhel, L.C.P. Assoni, A.H. Nakahara, N. Dos Santos Jábali, O.R.F. Costa, M.E.L. Baitello, S.P. Júnior, R.F. Silva, R. de Cássia Martins Alves Silva, D.R. da Silva, Genetic polymorphisms related to the vitamin D pathway in patients with cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Ecancermedicalscience, 16 (2022), p. 1383. [CrossRef]

- M.W. Yu, A. Gladek-Yarborough, S. Chiamprasert, R.M. Santella, Y.F. Liaw, C.J. Chen, Cytochrome P450 2E1 and glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma, Gastroenterology, 109(4) (1995), 1266-1273. [CrossRef]

- S. Boccia, L. Miele, N. Panic, F. Turati, D. Arzani, C. Cefalo, R. Amore, M. Bulajic, M. Pompili, G. Rapaccini, A. Gasbarrini, C. La Vecchia, A. Grieco, The effect of CYP, GST, and SULT polymorphisms and their interaction with smoking on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, Biomed. Res. Int., 2015 (2015), p. 179867. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, Z. Wang, G.J. Wang, H.X. Zhang, N. Gao, J. Wang, C.E. Wang, Z. Chang, Y. Fang, Y.F. Zhang, J. Zhou, H. Jin, H.L. Qiao, Higher CYP2E1 activity correlates with hepatocarcinogenesis induced by diethylnitrosamine, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 365(2) (2018), p. 398-407. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fang, H. Yang, G. Hu, J. Lu, J. Zhou, N. Gao, Y. Gu, C. Zhang, J. Qiu, Y. Guo, Y. Zhang, Q. Wen, H. Qiao, The POR rs10954732 polymorphism decreases susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma and hepsin as a prognostic biomarker correlated with immune infiltration based on proteomics, J. Transl. Med., 20(1) (2022), p. 88. [CrossRef]

- F. Cao, A. Luo, C. Yang, G6PD inhibits ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase, Cell Signal., 87 (2021), p. 110098. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).