1. Introduction

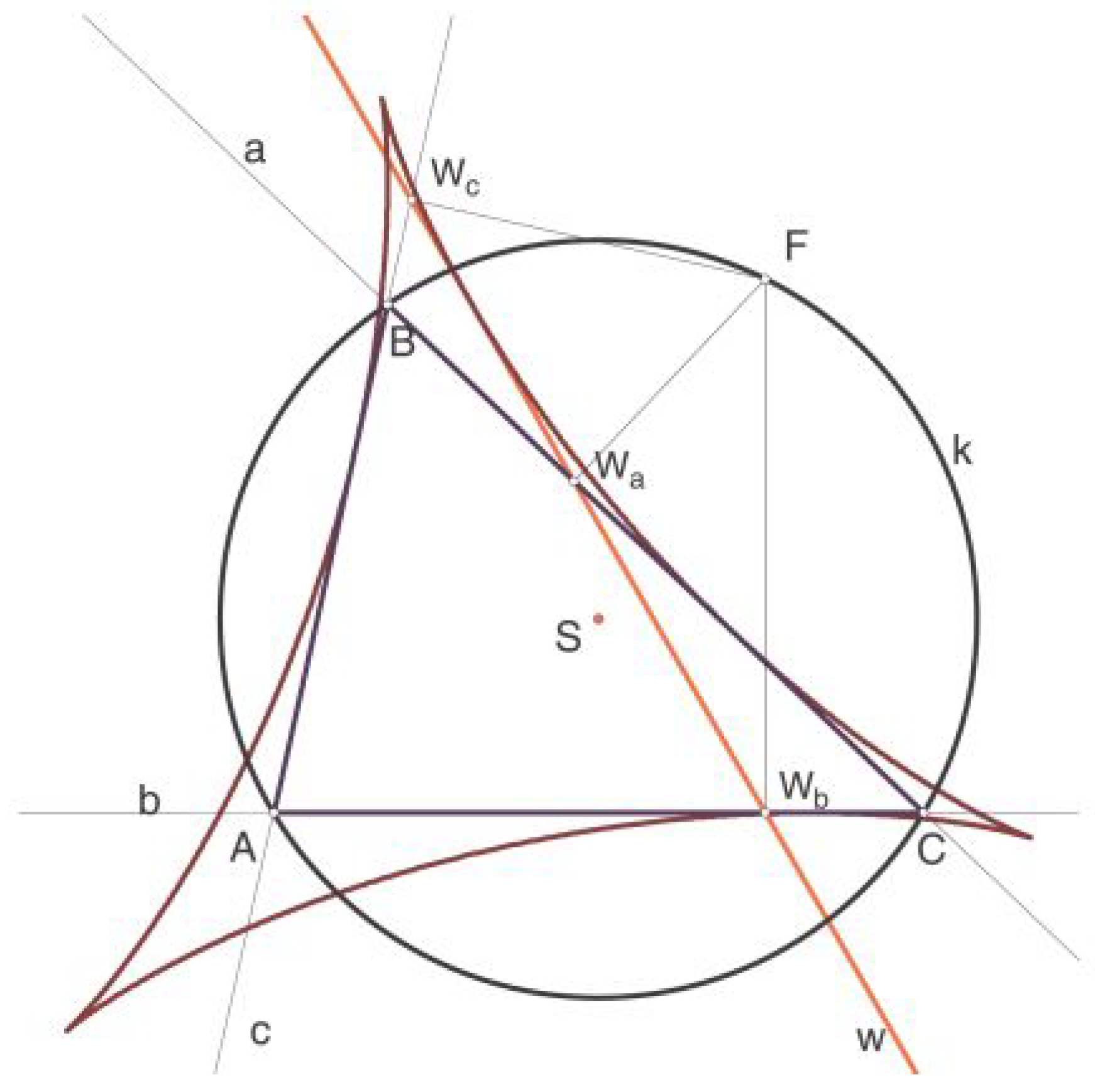

In 1856 Jakob Steiner proved that the envelope of Wallace-Simson lines when F moves around the circumscribed circle to a triangle ABC is a special curve of third class and fourth degree. That curve which has the line at infinity as double ideal tangent, a curve that is tangent to the three sides and to the three altitudes of the triangle, and has three cuspidal points and the three tangent lines on them meet at a point is called the Steiner deltoid, see

Figure 1. The following theorem is well known, [

1,

7]:

Theorem 1. If F is any point belonging to the circle k circumscribed to a triangle , then three points , , obtained by orthogonally projecting F, on the three sides of the triangle are collinear. The line thus obtained is called the Wallace-Simson line w of F, see Figure 1.

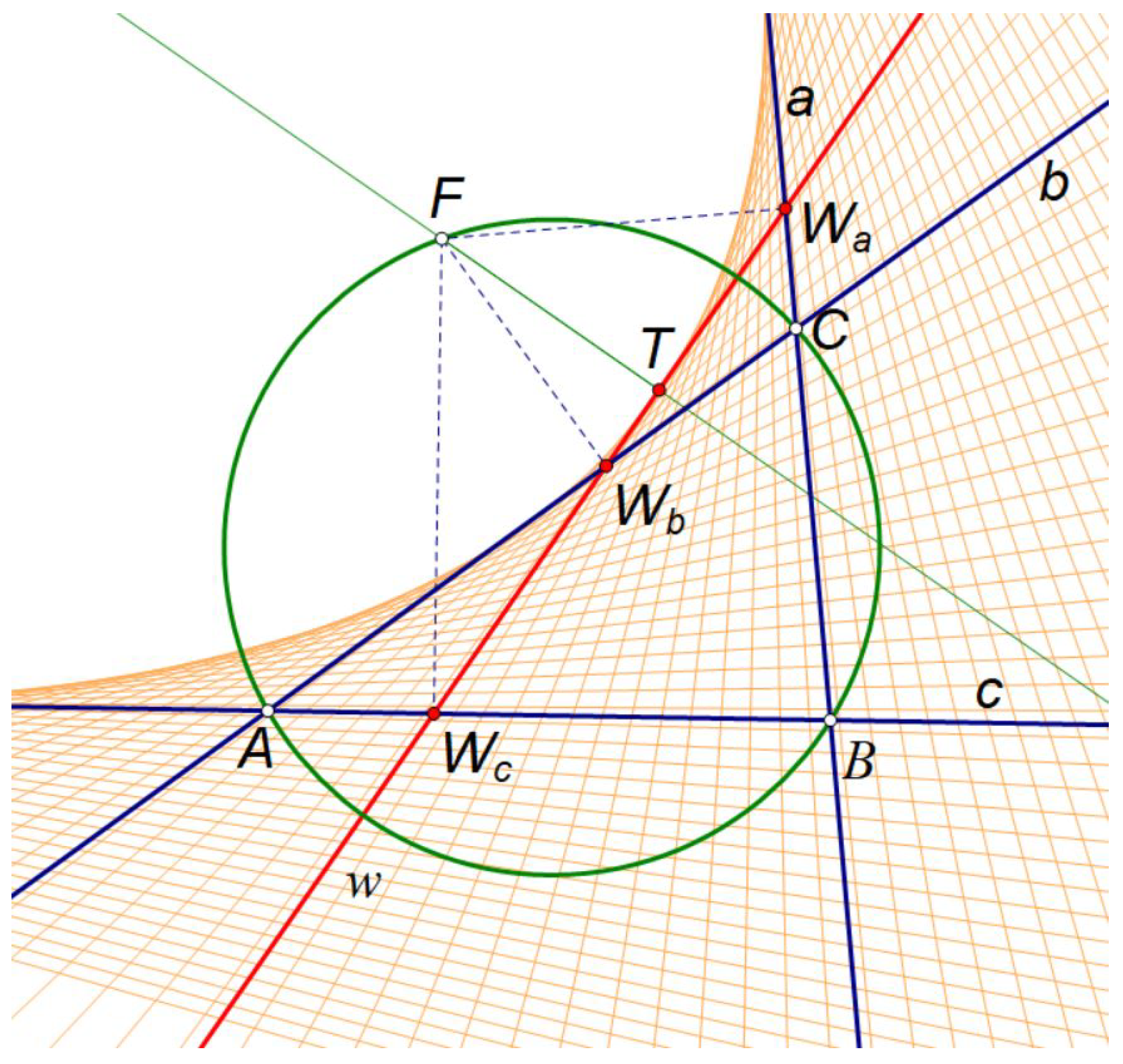

Notice, If the pencil of parabolas is given by three lines

a,

b,

c, and

F is any point belonging to the circle circumscribed to the triangle

given by the lines

a,

b,

c, then the Wallace-Simson line

w of the point

F is the vertex tangent of one parabola from the pencil, which is proved in [

1], see

Figure 2.

2. Deltoid Curves in a Pencil of Parabolas

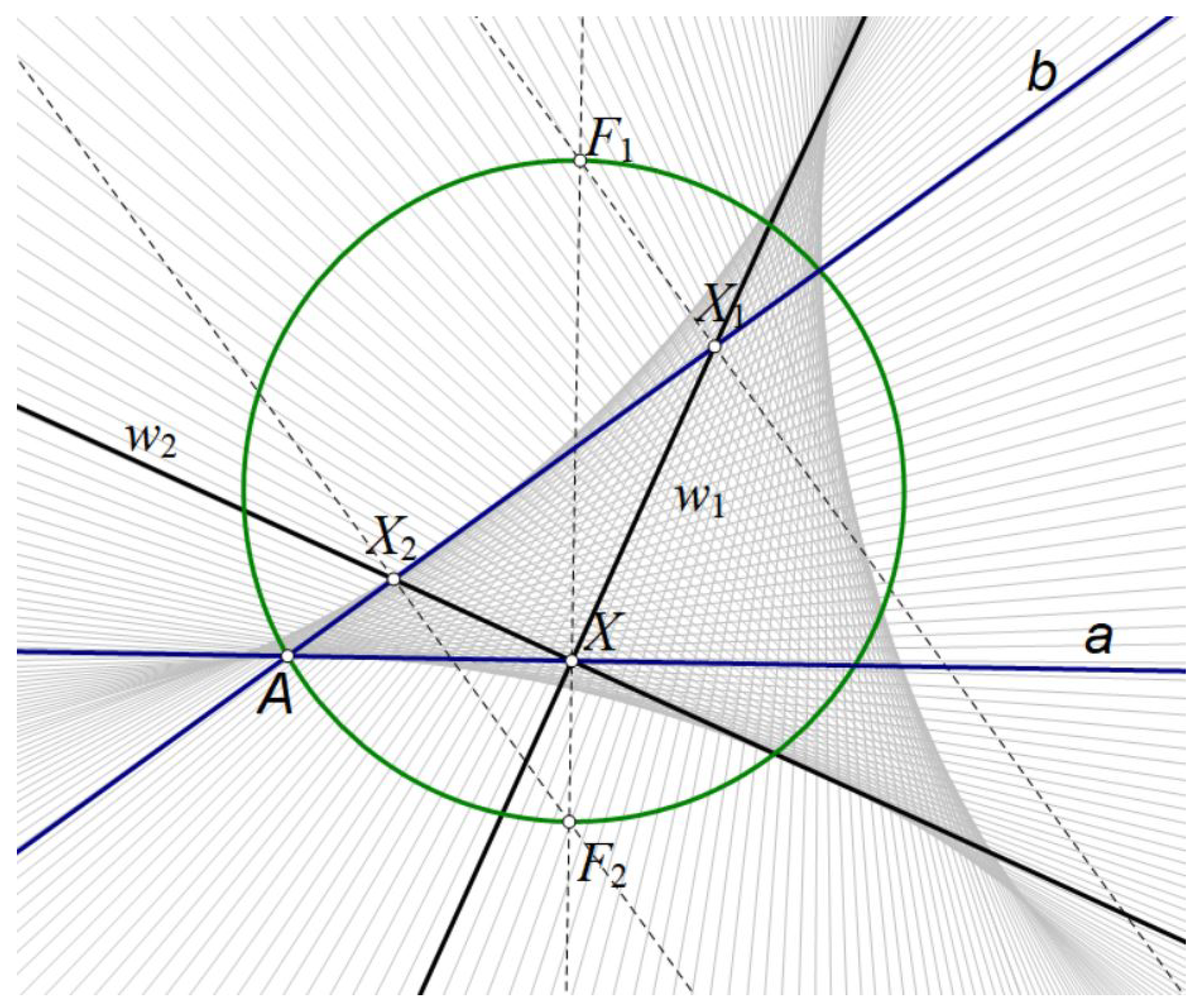

Analyzing Steiner’s constructions, we conclude that we can reach the deltoid by observing a pair of lines a and b with the intersection A on the circle, instead of the triangle inscribed in the circle, where we establish a 1–2-correspondence between two ranges of points and whose product will be the required envelope.

Theorem 2. Let the pencil of parabolas touching three lines be given. The envelope of the vertex tangents of the parabolas from the pencil is the Steiner deltoid curve, see Figure 3.

Proof of Theorem 2. Let’s construct the vertex tangents of parabolas as follows: On the two basic tangents of the given pencil, for example a and b, we establish a 1–2 -correspondence between two ranges of points and whose product will be the required envelope.

Let

X denote any point from range

, see

Figure 3. The intersections of the perpendicular to

a at the point

X with the circle circumscribed to the triangle

are denoted by

and

. These points are the foci of the two parabolas from the pencil. Perpendicular lines to

b at

and

intersect

b at

and

. On this way points

and

are associated to the point

X. On the same way reverse any point from

b is associated to two points from the range

a. Lines

and

are vertex tangents of those two parabolas from the pencil whose foci are

and

. These vertex tangents are elements of the required envelope. According to the Chasles relations [

6], we can conclude that this 1-2-correspondence between aforementioned ranges

and

is an 4

th class envelop. However, when the point

X is incident with triangle vertex

A,

is equal as

and

X,

can be any line from pencil of lines

, while

is incident with

b. Therefore, an envelope of class 4 splits into the envelope of class 3 and the pencil of lines

. It is still necessary to prove that this envelope is a curve of the 4

th order. In this sense, it is sufficient to prove that the envelope has one double tangent. For an infinite point

X on

a, perpendicular to line

a will be the infinite line of the plane, and its intersections with circle

k are absolute points. Perpendiculars from absolute points on the line

b coincide with the infinite line, so the two vertex tangents associated with the absolute foci coincide with the infinite line. So infinite line is double tangent.

The envelope is 4

th order and 3

rd class so it is deltoid, see

Figure 3. □

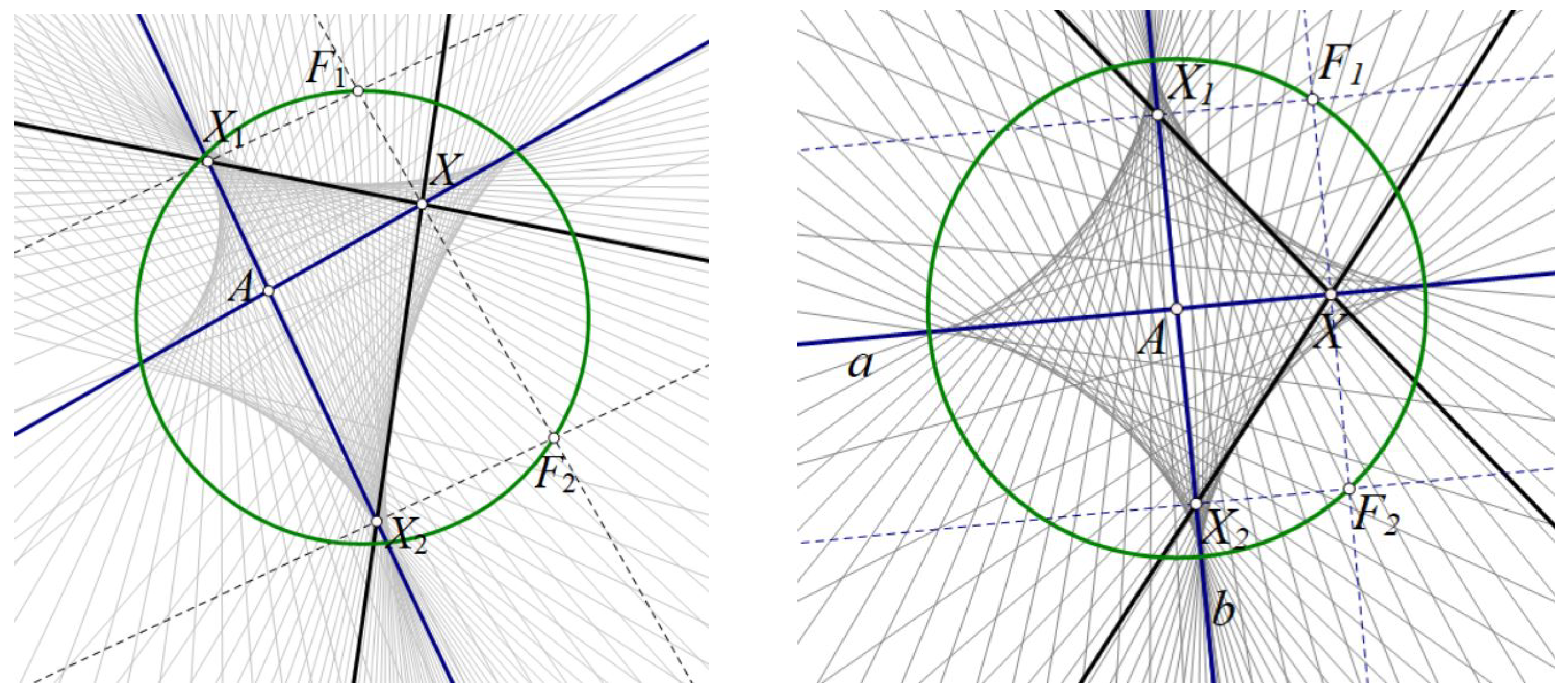

It is also interesting to show what happens in the cases when the intersection A of a pair of lines a and b is outside or inside the circle.

In the case when A is on the circle an envelope of class 4 splits into the envelope of class 3 (Steiner deltoid curve) and the pencil of lines .

In the case when

A is outside or inside the circle the required envelope is an 4

th class curve, see

Figure 4 left. If the lines

a,

b are perpendicular to each other and their intersection

A is the center of the circle, the resulting envelope is an astroid, see

Figure 4 right.

3. Curve of Centers of the Special Conic Section Pencil

A conic is uniquely determined by five of its points no three of which are collinear. Four points, called base points determine infinitely many conics which are called an order pencil of conics, [

7], (see Definition 7.3.1). Depending on whether the base points of a pencil of conics in

are real or not, whether they are proper (finite) or not, we see different versions of pencils of conics and we know that the corresponding centers of conics

1 are incident with hyperbola, ellipse, parabola or a circle.

The question is how to set the base points of a pencil of conics so that curve of centers would be a hyperbole, an ellipse, or a parabola, and how to make it a circle?

The answer is in the involution on the line at infinity. The double points of the involution that given pencil of conics cut on the line at infinity are centers of two parabolas from the pencil, if there are some. We learn that there are at most two parabolas in a generic pencil of conics in

,

7].We can distinguish the following particular cases.

If there are two parabolas in the pencil, the curve of centers is a hyperbola, which is equilateral if the given pencil contains a circle.

If there is one parabola in the pencil, the curve of centers is a parabola.

If there are no parabolas in the pencil, (only hyperbolas) the curve of centers is an ellipse. Therefore, we conclude, if the involution generated on the line at infinity is circular then the curve of centers is a circle

2.

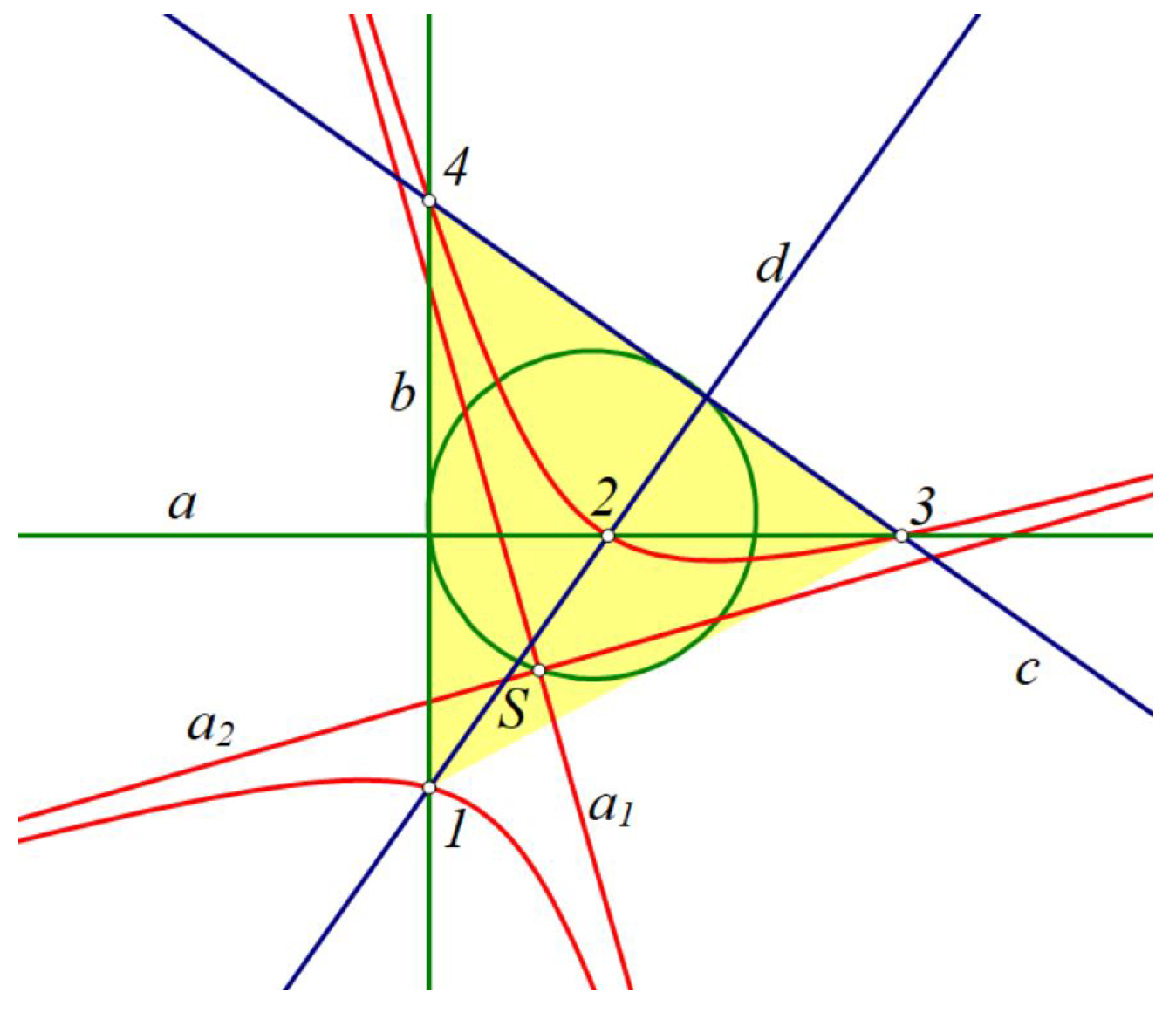

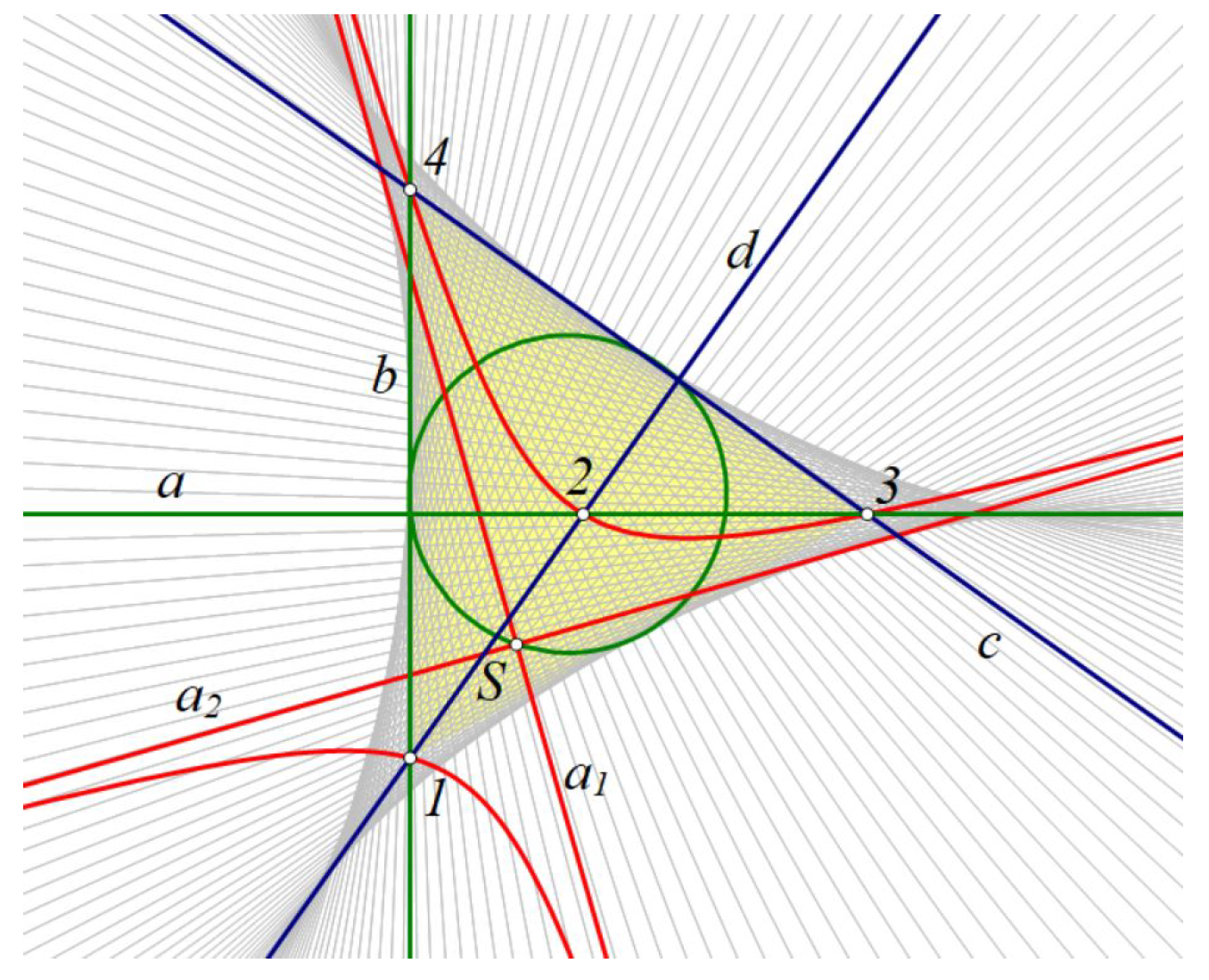

Theorem 3. Curve of centers in the pencil of equilateral hyperbolas is a circle, see Figure 5.

We assume that the four base points of a pencil of the first kind are the vertices 1,3, 4 of a triangle ▵ in the Euclidean plane together with ▵’s orthocenter 2. As a matter of fact, the three singular conics in this pencil are the three pairs of lines i.e., any side line of ▵ together with the altitude through the opposite vertex. Any of these pairs can be viewed as a limiting case of an equilateral hyperbola with principal axis equal to zero. Any regular conic in this pencil is an equilateral hyperbola.

Proof of Theorem 3. Without loss of generality, let the pencil of equilateral hyperbolas be set with two degenerate equilateral hyperbolas that intersects at points 1, 2, 3, 4, i.e., two pairs of orthogonal lines (a,b) and (c,d). The involution that given pencil of conics cut on the line at infinity is circular. The double points of the involution that given pencil of conics cut on the line at infinity are the absolute points. Therefore the curve of centers is a circle. □

A short analytical presentation of the statement from the previous theorem is given in the

Appendix A.

Notice that in the pencil of equilateral hyperbola, curve of centers is equal to Feuerbach circle. Also, in [

8] it is proved that the curve of the butterfly points coincides with the curve of the centers for the same quadrilateral of base points.

Furthermore, from the construction of the butterfly line in [

9] it is concluded that the butterfly line coincides with an asymptote of that hyperbola from the pencil that touches another conic from the given pencil at the butterfly point. Therefore, we conclude that the proof of the following theorem is shown in [

9].

Theorem 4. Asymptotes of hyperbolas in a generic pencil of conics envelope a curve of order four and class three.

Remark 1. Each asymptotes in the pencil of equilateral hyperbolas envelope Steiner deltoid curve, see Figure 6.

The centers of all conics from the pencil of equilateral hyperbolas lie on the circle so each infinite point is associated to one hyperbola from the pencil, which is associated to one point of a curve of centers. And reverse each point on the curve of centers is associated to one infinite point. We can conclude that this 1–1 correspondence between aforementioned ranges of first and second class is an 3th class envelop. The line at infinity is the double line on an envelope.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the article conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IBD and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this manuscript are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The contents of this manuscript have not been published previously. The contents of this manuscript are not now under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Appendix A

The equation of the curve of centers in the pencil of conic can be found as follows:

Let the pencil of conics

be determined with two conics

The center

of any conic from the pencil fulfilling the equation

where

For example, for the pencil of equilateral hyperbolas set as

curve of centers is a circle

where

References

- Sliepčević, A.; Božić, I. Steiner Curve in a Pencil of Parabolas. KOG 2012, 16, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- A.Sliepčević, I.Božić. The Analogue of Theorems Related To Wallace-Simson’s Line in Quasi-Hyperbolic Plane. In ICGG Pro-ceedings of the 16th International Conference on Geometry and Graphics, 2014.

- I. Božić Dragun. Wallace-Simson Line in Four Cayley-Klein Planes. In ICGG Pro-ceedings of the 18th International Conference on Geometry and Graphics, 2018, 2167-2170.

- Božić Dragn, I.; Koncul, H. Evolutes of conics in the quasi-hyperbolic and the hyperbolic plane. Journal of geometry 2023, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Božić Dragun, I. Evolutes of conics in the pseudo-Euclidean plane. Mathematica Pannonica 2023, 29, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieleitner, H. Theorie der ebenen algebraischen Kurven hoherer Ordnung. G. J. Goschen’sche Verlagshandlung, Leipzig, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- G. Glaeser, H. Stachel, B. Odehnal, The Universe of Conics. Springer, Berlin 2016.

- A. Sliepčević. A New Generalization of the Butterfly Theorem Journal for Geometry and Graphics, Volume 6 2002, 61–68.

- A. Sliepčević. Eine neue Schmetterlingskurve. Mathematica Pannonica 16/1 2005, 57-64.

| 1 |

The center of the conic is the pole of the ideal line with respect to the conic. |

| 2 |

Any non-degenerate conic that passes through the absolute points of Euclidean geometry is a Euclidean circle. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).