Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Lactate plays a critical role in cell metabolism and disease development. Under conditions of hypoxia or high-intensity exercise, cells use the glycolytic pathway to convert glucose into pyruvate, which is then reduced to lactate to quickly obtain energy. The traditional role of lactate is being redefined, as it is not only a provider of energy but also an important signaling molecule that regulates cell physiological functions, including histone lactylation modification, which affects gene expression. However, excessive accumulation of lactate is associated with the development of various diseases, such as liver disease, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Research has also found that small-molecule drugs can regulate lactate levels, providing new possibilities for treating related diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

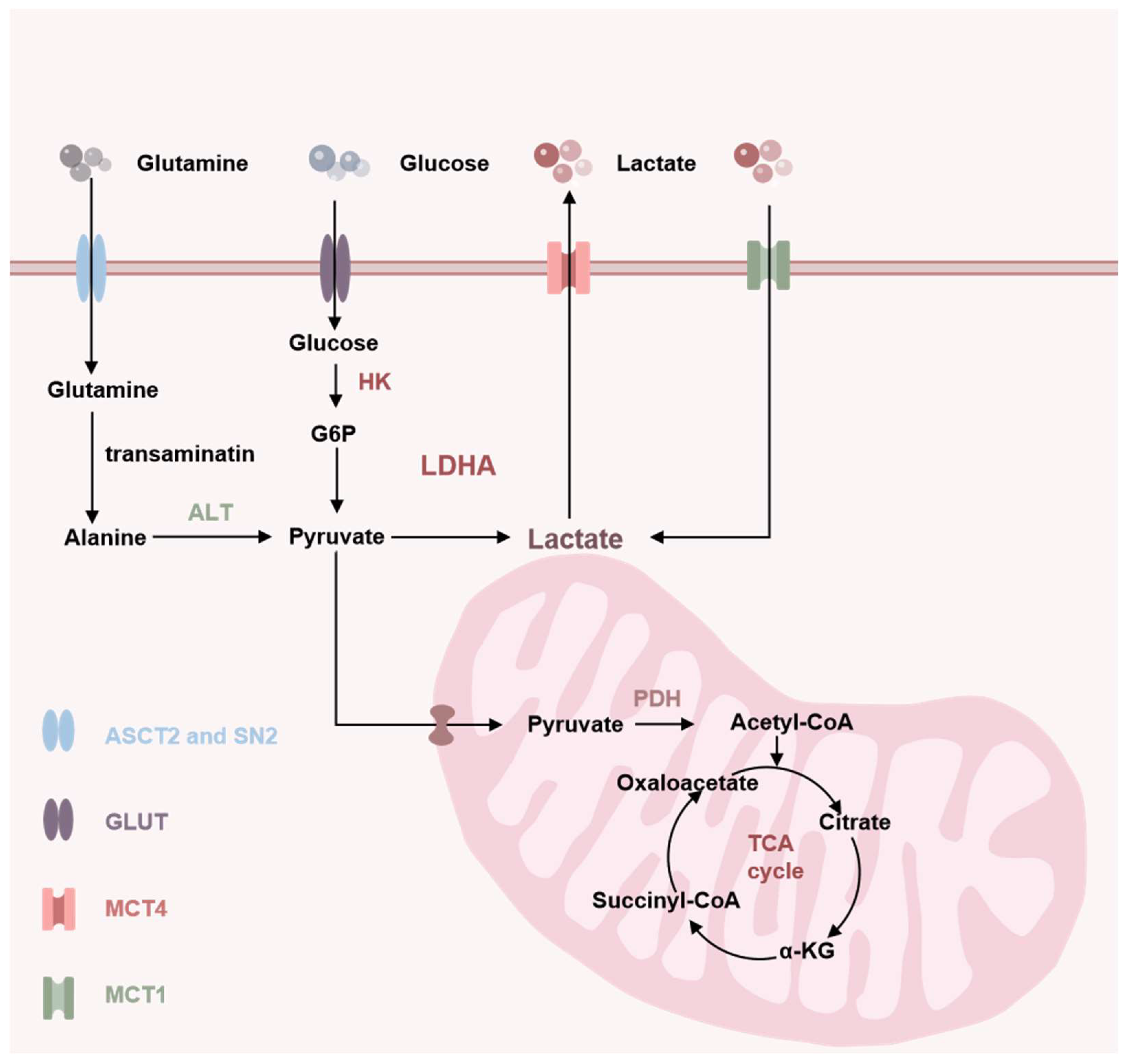

2. Soure of Lactate

3. Clearance of Lactate

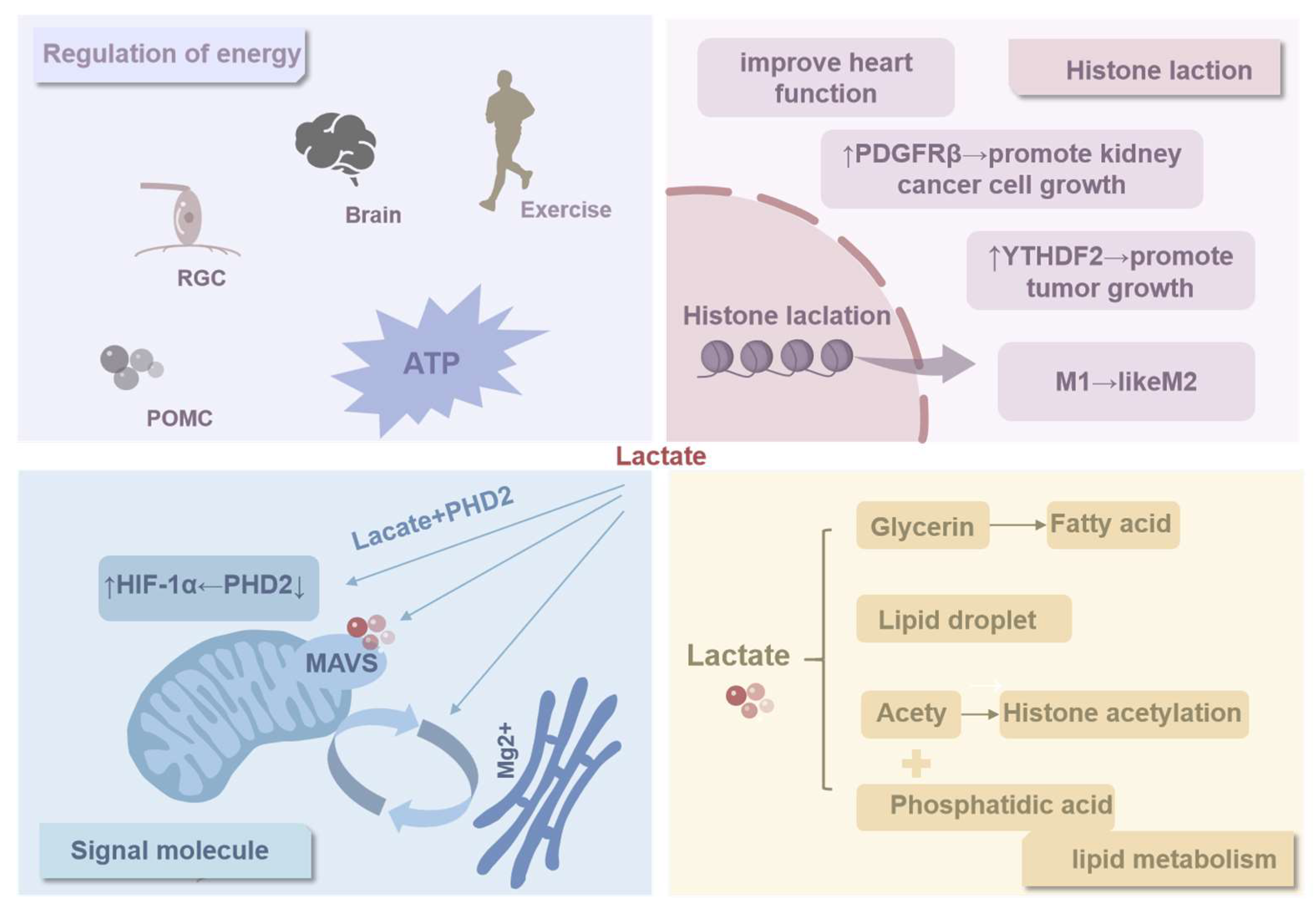

3.1. Regulation of Energy

3.2. Histone Lactylation

3.3. Signal Molecule

3.4. Biomimetic Principles of Biomembranes

4. Lactate’s Association with Diseases

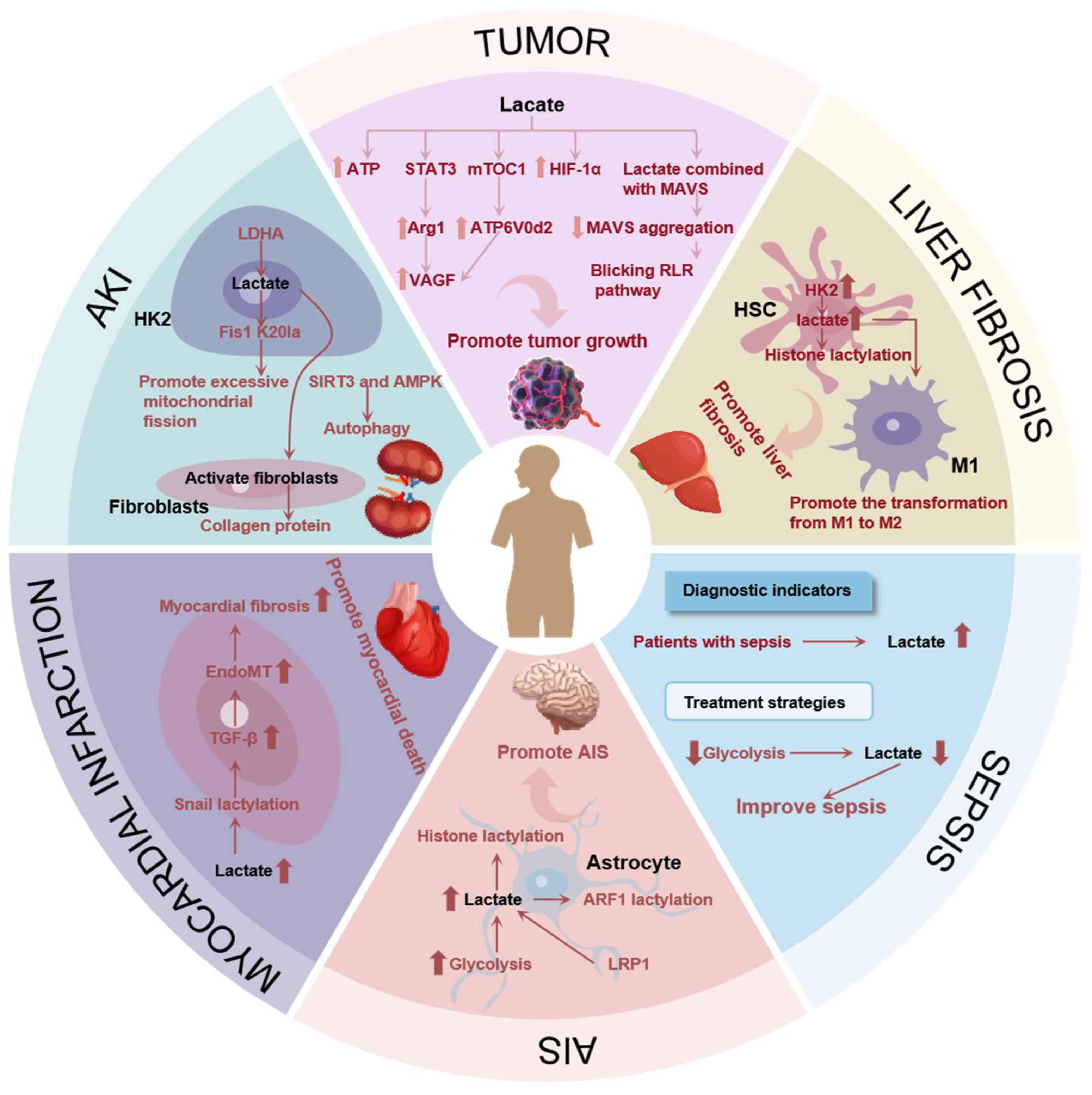

4.1. Lactate’s Role in Tumor

4.2. Lactate’s Role in Liver Fibrosis

4.3. Lactate’s Role in Sepsis

4.4. Lactate’s Role in Ischemic Stroke

4.5. Lactate’s Role in Myocardial Infarction

4.6. Lactate’s Role in Acute Kidney Injury

5. Small Molecule Drugs for Regulating Lactate Levels

5.1. Targeted Small Molecule Inhibitors for LDHA

5.2. Targeted Small Molecule Inhibitors for HIF-1α

5.3. Targeted Small Molecule Inhibitors for MCT1 or MCT4

| Small molecules drugs | Mechanism | Disease or Cell type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted inhibition of HK-2 to decrease lactate | |||

| 2-DG | Competition with glucose | Breast cancer | [110] |

| Prostate cancer | [111] | ||

| Ovarian cancer | [112] | ||

| Lung cancer | [113] | ||

| Glioma | [114] | ||

| Benz | Specific binding to HK2 | Rectal cancer cell | [117] |

| 3-BP | Pyruvate acid analogs | Colorectal cancer cell | [118] |

| Metformi | mimicking the physiological effects of G6P | Hepatocellular carcinoma cell | [119] |

| Pachymic acid | Breast cancer cell | [120] | |

| Ikarugamycin | Pancreatic cancer cell | [121] | |

| Chrysin | Inhibition of the binding between HK2 and VDAC | Liver cancer cell | [124] |

| Piperlongumine | Non-small cell lung cancer cell | [125] | |

| Targeted inhibition of LDHA to decrease lactate | |||

| Oxamate | Structurally similar to pyruvate | Pituitary adenoma | [131] |

| Medulloblastoma | |||

| Glioblastoma | |||

| HICA | Human colon cancer cell | [133] | |

| PSTMB | [134] | ||

| Gossypol | Compete with NADH | Pulmonary fibrosis | [137] |

| FX-11 | Lymphoma cell | [138] | |

| Galloflavin | Breast cancer | [139] | |

| Colon cancer | |||

| Liver cancer | |||

| LDHA-IN3 | Unknown mechanism of action | Melanoma cell | [140] |

| Az-33 | MCF-7 and HCT116 | [141] | |

| GPEG-140 | Pulmonary fibrosis | [142] | |

| Targeted inhibition of HIF-1α to decrease lactate | |||

| PX-478 | Directly inhibiting HIF-1α | Gastric mucosal lesion | [145] |

| Diabetic | [146] | ||

| Oligomycin | Inhibiting the enzyme H+-ATP synthase | Senescent cell | [147] |

| Steppogenin | Directly inhibiting HIF-1α | HEK293T cell | [149] |

| Albendazole | Directly inhibiting HIF-1α | NSCLC | [150] |

| CRLX101 | Directly inhibiting HIF-1α | rectal cancer | [151] |

| Chloramphenicol | Inhibition of the HIF-1α/SENP-1 protein interaction | Non-small cell lung cancer | [155] |

| Targeted inhibition of MCT1 or MCT4 to decrease lactate | |||

| AR-C155858 | Inhibition of MCT1 | Breast cancer | [159] |

| AZD3965 | Breast cancer cell | [160] | |

| AZD0095 | Inhibition of MCT4 | lung cancer cell | [161] |

6. Conclusion and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, X.; Ng, C.P.; Jones, O.; Fung, T.S.; Ryu, K.W.; Li, D.; Thompson, C.B. Lactate activates the mitochondrial electron transport chain independently of its metabolism. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3904–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan VP, Miyamoto S. HK2/hexokinase-II integrates glycolysis and autophagy to confer cellular protection. Autophagy. 2015;11(6):963-4.

- Tavoulari, S.; Sichrovsky, M.; Kunji, E.R.S. Fifty years of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier: New insights into its structure, function, and inhibition. Acta Physiol. 2023, 238, e14016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; De Marchi, E.; Suski, J.M.; Bononi, A.; Giorgi, C.; Marchi, S.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; et al. ATP synthesis and storage. Purinergic Signal. 2012, 8, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantin VR, St-Pierre J, Leder P. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2006 Jun;9(6):425-34.

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):211-218.

- Zhang, S.-L.; Hu, X.; Zhang, W.; Yao, H.; Tam, K.Y. Development of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitors in medicinal chemistry with particular emphasis as anticancer agents. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeva-Andany, M.; López-Ojén, M.; Funcasta-Calderón, R.; Ameneiros-Rodríguez, E.; Donapetry-García, C.; Vila-Altesor, M.; Rodríguez-Seijas, J. Comprehensive review on lactate metabolism in human health. Mitochondrion 2014, 17, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, Y.; Bodeau, S.; Batteux, B.; Gras-Champel, V.; Masmoudi, K.; Maizel, J.; De Broe, M.E.; Lalau, J.-D.; Lemaire-Hurtel, A.-S. A Study of Associations Between Plasma Metformin Concentration, Lactic Acidosis, and Mortality in an Emergency Hospitalization Context. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e1194–e1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, Y.; Bodeau, S.; Batteux, B.; Gras-Champel, V.; Masmoudi, K.; Maizel, J.; De Broe, M.E.; Lalau, J.-D.; Lemaire-Hurtel, A.-S. A Study of Associations Between Plasma Metformin Concentration, Lactic Acidosis, and Mortality in an Emergency Hospitalization Context. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e1194–e1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha MK, Lee IK, Suk K. Metabolic reprogramming by the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-lactate axis: Linking metabolism and diverse neuropathophysiologies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 Sep;68:1-19.

- Halestrap, A.P. The SLC16 gene family – Structure, role and regulation in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P. The SLC16 gene family – Structure, role and regulation in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felmlee, M.A.; Jones, R.S.; Rodriguez-Cruz, V.; Follman, K.E.; Morris, M.E. Monocarboxylate Transporters (SLC16): Function, Regulation, and Role in Health and Disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felmlee, M.A.; Jones, R.S.; Rodriguez-Cruz, V.; Follman, K.E.; Morris, M.E. Monocarboxylate Transporters (SLC16): Function, Regulation, and Role in Health and Disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6917–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tu, F.; Gill, P.S.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarr, R.L.; Esco, M.R.; Tolusso, D.V.; Hallmark, A.V.; Earley, R.L.; Higginbotham, J.C.; Fedewa, M.V.; Bishop, P. Comparison of Lactate and Electromyographical Thresholds After an Exercise Bout. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 3322–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy-Kanniappan, S.; Geschwind, J.-F.H. Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: progress and prospects. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, R.; Aldana, B.I.; Bulli, G.; Skytt, D.M.; Waagepetersen, H.; Bergersen, L.H.; Kolko, M. Lactate-Mediated Protection of Retinal Ganglion Cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 1878–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.; Rabe, D.; Duysen, K.; Melchert, U.H.; Oltmanns, K.M. Lactate infusion increases brain energy content during euglycemia but not hypoglycemia in healthy men. NMR Biomed. 2019, 32, e4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhomme, T.; Clasadonte, J.; Imbernon, M.; Fernandois, D.; Sauve, F.; Caron, E.; Lima, N.d.S.; Heras, V.; Martinez-Corral, I.; Mueller-Fielitz, H.; et al. Tanycytic networks mediate energy balance by feeding lactate to glucose-insensitive POMC neurons. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, E.C.; Li, Q. Lactate activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert, B.; Li, K.Y.; Cai, L.; Hensley, C.T.; Kim, J.; Zacharias, L.G.; Yang, C.; Do, Q.N.; Doucette, S.; Burguete, D.; et al. Lactate Metabolism in Human Lung Tumors. Cell 2017, 171, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Wang G. Protein Modification and Autophagy Activation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1206:237-259.

- Bickel, D.; Vranken, W. Effects of Phosphorylation on Protein Backbone Dynamics and Conformational Preferences. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 4998–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Pan, R. Protein ubiquitination in plant peroxisomes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Pan, R. Protein ubiquitination in plant peroxisomes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, A.; Cai, L.; Huang, W.; Yan, S.; Wei, Y.; Ruan, X.; Fang, W.; Dai, X.; Cheng, J.; et al. ACSS2-dependent histone acetylation improves cognition in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troutman, T.D.; Hu, W.; Fulenchek, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Kurosaki, T.; Bazan, J.F.; Pasare, C. Role for B-cell adapter for PI3K (BCAP) as a signaling adapter linking Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to serine/threonine kinases PI3K/Akt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 109, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry-Caro, R.A.; McDaniel, M.M.; Overcast, G.R.; Jain, V.G.; Troutman, T.D.; Pasare, C. TLR signaling adapter BCAP regulates inflammatory to reparatory macrophage transition by promoting histone lactylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 30628–30638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chai, P.; Xie, M.; Ge, S.; Ruan, J.; Fan, X.; Jia, R. Histone lactylation drives oncogenesis by facilitating m6A reader protein YTHDF2 expression in ocular melanoma. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.-Y.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liao, Y.; Gao, J.; Liao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; et al. Positive feedback regulation of microglial glucose metabolism by histone H4 lysine 12 lactylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.-Y.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liao, Y.; Gao, J.; Liao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; et al. Positive feedback regulation of microglial glucose metabolism by histone H4 lysine 12 lactylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.; Di, C.; Chang, P.; Li, L.; Feng, Z.; Xiao, S.; Yan, X.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Qi, R.; et al. Lactylated Histone H3K18 as a Potential Biomarker for the Diagnosis and Predicting the Severity of Septic Shock. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 786666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Mang, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, X.; Tong, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; et al. Histone Lactylation Boosts Reparative Gene Activation Post–Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, X.; Gu, P.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Guo, Q.; Long, Q.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Adipocyte-derived lactate is a signalling metabolite that potentiates adipose macrophage inflammation via targeting PHD2. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Xu, Z.-G.; Tu, H.; Hu, F.; Dai, J.; Chang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, H.; et al. Lactate Is a Natural Suppressor of RLR Signaling by Targeting MAVS. Cell 2019, 178, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, C.C.; Ramachandran, K.; Enslow, B.T.; Maity, S.; Bursic, B.; Novello, M.J.; Rubannelsonkumar, C.S.; Mashal, A.H.; Ravichandran, J.; Bakewell, T.M.; et al. Lactate Elicits ER-Mitochondrial Mg2+ Dynamics to Integrate Cellular Metabolism. Cell 2020, 183, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton RG, Simons K. The Biology of Lipids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2024 Aug 1;16(8):a041713.

- Snaebjornsson, M.T.; Janaki-Raman, S.; Schulze, A. Greasing the Wheels of the Cancer Machine: The Role of Lipid Metabolism in Cancer. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund J, Aas V, Tingstad RH, Van Hees A, Nikolić N. Utilization of lactate in human myotubes and interplay with glucose and fatty acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2018 Jun 29;8(1):9814.

- Ippolito L, Comito G, Parri M, et al. Lactate Rewires Lipid Metabolism and Sustains a Metabolic-Epigenetic Axis in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2022 Apr 1;82(7):1267-1282.

- Liu, L.; MacKenzie, K.R.; Putluri, N.; Maletić-Savatić, M.; Bellen, H.J. The Glia-Neuron Lactate Shuttle and Elevated ROS Promote Lipid Synthesis in Neurons and Lipid Droplet Accumulation in Glia via APOE/D. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M. Evidence for acutely hypoxic cells in mouse tumours, and a possible mechanism of reoxygenation. Br. J. Radiol. 1979, 52, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M. Evidence for acutely hypoxic cells in mouse tumours, and a possible mechanism of reoxygenation. Br. J. Radiol. 1979, 52, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamdar, S.; Suresh, A.P.; Mangal, J.L.; Ng, N.D.; Sundem, A.; Wu, C.; Lintecum, K.; Thumsi, A.; Khodaei, T.; Halim, M.; et al. Rescue of dendritic cells from glycolysis inhibition improves cancer immunotherapy in mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Xue, L.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Luo, D. Lactate from glycolysis regulates inflammatory macrophage polarization in breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Xu, H.-M.; Ma, Y.-H.; Zhang, D.-K. Demethylzeylasteral targets lactate to suppress the tumorigenicity of liver cancer stem cells: It is attributed to histone lactylation? Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 194, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hen, P. , Zuo H., Xiong H., Kolar M.J., Chu Q., Saghatelian A., Siegwart D.J., Wan Y. Gpr132 sensing of lactate mediates tumor-macrophage in-terplay to promote breast cancer metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:580–585.

- Cassavaugh J, Lounsbury KM. Hypoxia-mediated biological control. J Cell Biochem. 2011 Mar;112(3):735-744.

- Li, T.; Mao, C.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Tao, Y. Epigenetic crosstalk between hypoxia and tumor driven by HIF regulation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactate. Nature. 2014 Sep 25;513(7519):559-563.

- Luo M, Zhu J, Ren J, Tong Y, Wang L, Ma S, Wang J. Lactate increases tumor malignancy by promoting tumor small extracellular vesicles production via the GPR81-cAMP-PKA-HIF-1α axis. Front Oncol. 2022 Dec 1;12:1036543.

- Daw, C.C.; Ramachandran, K.; Enslow, B.T.; Maity, S.; Bursic, B.; Novello, M.J.; Rubannelsonkumar, C.S.; Mashal, A.H.; Ravichandran, J.; Bakewell, T.M.; et al. Lactate Elicits ER-Mitochondrial Mg2+ Dynamics to Integrate Cellular Metabolism. Cell 2020, 183, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Xu, Z.-G.; Tu, H.; Hu, F.; Dai, J.; Chang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, H.; et al. Lactate Is a Natural Suppressor of RLR Signaling by Targeting MAVS. Cell 2019, 178, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Luo, J.; Kuang, D.; Xu, S.; Duan, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xie, X.; Yin, B.; Chen, F.; et al. Lactate inhibits ATP6V0d2 expression in tumor-associated macrophages to promote HIF-2α–mediated tumor progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, M.; Pinzani, M. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 65, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou WC, Zhang QB, Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jun 21;20(23):7312-7324.

- Higashi, T.; Friedman, S.L.; Hoshida, Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 121, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, H.; Terry, A.R.; Chronis, C.; Hay, N. Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Huangyang, P.; Burrows, M.; Guo, K.; Riscal, R.; Godfrey, J.; Lee, K.E.; Lin, N.; Lee, P.; Blair, I.A.; et al. FBP1 loss disrupts liver metabolism and promotes tumorigenesis through a hepatic stellate cell senescence secretome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, H.; Terry, A.R.; Chronis, C.; Hay, N. Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubil, E.; Caskey, L.; Holtzhausen, A.; Hunter, D.; Story, C.; Earp, H.S. Tumor-secreted Pros1 inhibits macrophage M1 polarization to reduce antitumor immune response. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2356–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Peña S, O’Neill LA. Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 2014 Sep 2;5:420.

- Gharib, S.A.; McMahan, R.S.; Eddy, W.E.; Long, M.E.; Parks, W.C.; Aitken, M.L.; Manicone, A.M. Transcriptional and functional diversity of human macrophage repolarization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 143, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Huang, Z.; Cao, Y. Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells Promote the M1 to M2 Macrophage Transformation and Liver Fibrosis by Elevating the Histone Acetylation Level. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, B.; Ramakrishna, K.; Dhamoon, A.S. Sepsis: The evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach, L.J.; Watson, R.S.; Sorce, L.R.; Argent, A.C.; Menon, K.; Hall, M.W.; Akech, S.; Albers, D.J.; Alpern, E.R.; Balamuth, F.; et al. International Consensus Criteria for Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA 2024, 331, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhou, R.; Qin, J.; Li, Y. Hierarchical Capability in Distinguishing Severities of Sepsis via Serum Lactate: A Network Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X. Potential biomarker for diagnosis and therapy of sepsis: Lactylation. Immunity, Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Kong L, Tan S, et al. Zhx2 Accelerates Sepsis by Promoting Macrophage Glycolysis via Pfkfb3. J Immunol. 2020 Apr 15;204(8):2232-2241.

- Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, et al. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022 [published correction appears in Int J Stroke. 2022 Apr;17(4):478.

- Herpich F, Rincon F. Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(11):1654-1663.

- Sharma, D.; Singh, M.; Rani, R. Role of LDH in tumor glycolysis: Regulation of LDHA by small molecules for cancer therapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 87, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin XX, Fang MD, Hu LL, Yuan Y, Xu JF, Lu GG, Li T. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase predicts poor prognosis of acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 7;17(10):e0275651.

- Magistretti, P.J.; Allaman, I. Lactate in the brain: from metabolic end-product to signalling molecule. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.-Y.; Pan, X.-R.; Luo, X.-X.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.-X.; Yang, S.-H.; Zhong, Z.-Q.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Wang, P.-F.; et al. Astrocyte-derived lactate aggravates brain injury of ischemic stroke in mice by promoting the formation of protein lactylation. Theranostics 2024, 14, 4297–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oue, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Qiao, W.; Yuanxin, C.; Ren, Y.; Kurti, A.; Shue, F.; Parsons, T.M.; Perkerson, R.B.; Kawatani, K.; et al. LRP1 in vascular mural cells modulates cerebrovascular integrity and function in the presence of APOE4. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Kang, X.; Su, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Deng, X.; Huang, H.; Li, T.; et al. Agomelatine promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and preserves white matter integrity after cerebral ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Huang, A.; Du, F.; Liao, Y.; He, Y.; et al. Astrocytic LRP1 enables mitochondria transfer to neurons and mitigates brain ischemic stroke by suppressing ARF1 lactylation. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 2054–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Morddarvanjoghi, F.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaleghi, A.A.; Hezarkhani, L.A.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wal, P.; Aziz, N.; Singh, Y.K.; Wal, A.; Kosey, S.; Rai, A.K. Myocardial Infarction as a Consequence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 19, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, J. The role of lactate in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, W.; Yang, K.; Wu, B.; Xie, D.; Peng, C. Association between lactate/albumin ratio and prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 54, e14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Luo, C.; Li, Q.; Zheng, T.; Gao, P.; Wang, B.; Duan, Z. Association between lactate/albumin ratio and all-cause mortality in critical patients with acute myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrić, Z.; Zaputović, L.; Žagar, D.; Matana, A.; Smokvina, D. Usefulness of blood lactate as a predictor of shock development in acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991, 67, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talman, V.; Ruskoaho, H. Cardiac fibrosis in myocardial infarction—from repair and remodeling to regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2016, 365, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González A, Schelbert EB, Díez J, Butler J. Myocardial Interstitial Fibrosis in Heart Failure: Biological and Translational Perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Apr 17;71(15):1696-1706.

- Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007 Aug;13(8):952-61.

- Medici, D.; Potenta, S.; Kalluri, R. Transforming growth factor-β2 promotes Snail-mediated endothelial–mesenchymal transition through convergence of Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signalling. Biochem. J. 2011, 437, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan M, Yang K, Wang X, Chen L, Gill PS, Ha T, Liu L, Lewis NH, Williams DL, Li C. Lactate promotes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via Snail1 lactylation after myocardial infarction. Sci Adv. 2023 Feb 3;9(5):eadc9465.

- Levey AS, James MT. Acute Kidney Injury. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 7;167(9):ITC66-ITC80.

- Pickering, J.W.; Blunt, I.R.H.; Than, M.P. Acute Kidney Injury and mortality prognosis in Acute Coronary Syndrome patients: A meta-analysis. Nephrology 2018, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Jung, J.-Y.; Yoon, H.-K.; Yang, S.-M.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, W.H.; Jung, C.-W.; Suh, K.-S. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and lactate level during surgery predict acute kidney injury and early allograft dysfunction after liver transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Yao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Sun, M.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. PDHA1 hyperacetylation-mediated lactate overproduction promotes sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via Fis1 lactylation. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin JY, Wei XX, Zhi XL, Wang XH, Meng D. Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission in cardiovascular disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021 May;42(5):655-664.

- Lin, Q.; Li, S.; Jiang, N.; Jin, H.; Shao, X.; Zhu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; et al. Inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome attenuates apoptosis in contrast-induced acute kidney injury through the upregulation of HIF1A and BNIP3-mediated mitophagy. Autophagy 2020, 17, 2975–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan C, Gu J, Li T, Chen H, Liu K, Liu M, Zhang H, Xiao X. Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis alleviates sepsis induced acute kidney injury by promoting lactate/Sirtuin 3/AMPK regulated autophagy. Int J Mol Med. 2021 Mar;47(3):19.

- Livingston, M.J.; Shu, S.; Fan, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiao, Q.; Yin, X.-M.; Venkatachalam, M.A.; Dong, Z. Tubular cells produce FGF2 via autophagy after acute kidney injury leading to fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis. Autophagy 2022, 19, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculae, A.; Gherghina, M.-E.; Peride, I.; Tiglis, M.; Nechita, A.-M.; Checherita, I.A. Pathway from Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease: Molecules Involved in Renal Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhai, P.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J.; Suo, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Weng, X.; Zhou, X.; et al. Fibroblastic reticular cell-derived exosomes are a promising therapeutic approach for septic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2023, 105, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wen, P.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, H.; Luo, J.; Xu, L.; Zen, K.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Tubule-derived lactate is required for fibroblast activation in acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020, 318, F689–F701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciscato, F.; Ferrone, L.; Masgras, I.; Laquatra, C.; Rasola, A. Hexokinase 2 in Cancer: A Prima Donna Playing Multiple Characters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicano, H.; Martin, D.S.; Xu, R.-H.; Huang, P. Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4633–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Zhu X, Wu H, Jiang K, Zhao G, Shaukat A, Deng G, Qiu C. Targeting the ROS/PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α/HK2 axis of breast cancer cells: Combined administration of Polydatin and 2-Deoxy-d-glucose. J Cell Mol Med. 2019 May;23(5):3711-3723.

- Wanyan Y, Xu X, Liu K, Zhang H, Zhen J, Zhang R, Wen J, Liu P, Chen Y. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose Promotes Buforin IIb-Induced Cytotoxicity in Prostate Cancer DU145 Cells and Xenograft Tumors. Molecules. 2020 Dec 7;25(23):5778.

- Zhang, L.; Su, J.; Xie, Q.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yi, D.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Xu, Y. 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose Sensitizes Human Ovarian Cancer Cells to Cisplatin by Increasing ER Stress and Decreasing ATP Stores in Acidic Vesicles. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2015, 29, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-B.; Li, T.-H.; Ren, Z.-P.; Liu, Y. Combination of 2-deoxy d-glucose and metformin for synergistic inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer: A reactive oxygen species and P-p38 mediated mechanism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Fan T, Sun G, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Zhang N, Zhao L, Zhong R, Peng Y. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose increases the sensitivity of glioblastoma cells to BCNU through the regulation of glycolysis, ROS and ERS pathways: In vitro and in vivo validation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022 May;199:115029.Chen M, Wang S, Chen Y, et al. Precision cardiac targeting: empowering curcumin therapy through smart exosome-mediated drug delivery in myocardial infarction. Regen Biomater. 2023;11:rbad108.

- Pajak B, Siwiak E, Sołtyka M, et al. 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose and Its Analogs: From Diagnostic to Therapeutic Agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21(1):234. Published 2019 Dec 29.

- Raez, L.E.; Papadopoulos, K.; Ricart, A.D.; Chiorean, E.G.; DiPaola, R.S.; Stein, M.N.; Rocha Lima, C.M.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Tolba, K.; Langmuir, V.K.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation trial of 2-deoxy-d-glucose alone or combined with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zheng, M.; Wu, S.; Gao, S.; Yang, M.; Li, Z.; Min, Q.; Sun, W.; Chen, L.; Xiang, G.; et al. Benserazide, a dopadecarboxylase inhibitor, suppresses tumor growth by targeting hexokinase 2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X.; Yu, J. 3-Bromopyruvate overcomes cetuximab resistance in human colorectal cancer cells by inducing autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWaal D, Nogueira V, Terry AR, et al. Hexokinase-2 depletion inhibits glycolysis and induces oxidative phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma and sensitizes to metformin [published correction appears in Nat Commun. 2018 Jun 26;9(1):2539.

- Miao, G.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tong, G. Targeting Pyruvate Kinase M2 and Hexokinase II, Pachymic Acid Impairs Glucose Metabolism and Induces Mitochondrial Apoptosis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang SH, Dong FY, Da LT, Yang XM, Wang XX, Weng JY, Feng L, Zhu LL, Zhang YL, Zhang ZG, Sun YW, Li J, Xu MJ. Ikarugamycin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell glycolysis by targeting hexokinase 2. FASEB J. 2020 Mar;34(3):3943-3955.

- Tian, G.; Zhou, J.; Quan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Li, J.; Xin, Y.; Wu, W.; Tang, X.; Liu, X. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) overexpression alleviates cardiac fibroblast activation in cardiac fibrosis via regulating fatty acid metabolism. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach CH, Jung KH, Lee JH, Park JW, Moon SH, Cho YS, Choe YS, Lee KH. Mild Alkalization Acutely Triggers the Warburg Effect by Enhancing Hexokinase Activity via Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel Binding. PLoS One. 2016 Aug 1;11(8):e0159529.

- Xu, D.; Jin, J.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, H. Chrysin inhibited tumor glycolysis and induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting hexokinase-2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Li, M.; Yu, X.; Gao, F.; Li, W. Repression of Hexokinases II-Mediated Glycolysis Contributes to Piperlongumine-Induced Tumor Suppression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Tang, X.; Yin, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Dong, L.; Shi, M.; Qin, J.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals BHLHE40-driven pro-tumour neutrophils with hyperactivated glycolysis in pancreatic tumour microenvironment. Gut 2022, 72, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Chen L, Kong D, Zhang X, Xia S, Liang B, Li Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Shao J, Zheng S, Zhang F. Canonical Wnt signaling promotes HSC glycolysis and liver fibrosis through an LDH-A/HIF-1α transcriptional complex. Hepatology. 2024 Mar 1;79(3):606-623.

- Wang, L.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Yan, P.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Pan, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; et al. Serum Proteomics Identifies Biomarkers Associated With the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, P.; Xia, F.; Tang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gu, L.; et al. Capsaicin ameliorates inflammation in a TRPV1-independent mechanism by inhibiting PKM2-LDHA-mediated Warburg effect in sepsis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022, 29, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA)-mediated lactate generation promotes pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvona, C.J.; Fillmore, H.L. Oxamate, but Not Selective Targeting of LDH-A, Inhibits Medulloblastoma Cell Glycolysis, Growth and Motility. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinoz, M.A.; Ozpinar, A. Oxamate targeting aggressive cancers with special emphasis to brain tumors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-Y.; Chung, T.-W.; Han, C.W.; Park, S.Y.; Park, K.H.; Jang, S.B.; Ha, K.-T. A Novel Lactate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor, 1-(Phenylseleno)-4-(Trifluoromethyl) Benzene, Suppresses Tumor Growth through Apoptotic Cell Death. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-Y.; Chung, T.-W.; Han, C.W.; Park, S.Y.; Park, K.H.; Jang, S.B.; Ha, K.-T. A Novel Lactate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor, 1-(Phenylseleno)-4-(Trifluoromethyl) Benzene, Suppresses Tumor Growth through Apoptotic Cell Death. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patgiri, A.; Skinner, O.S.; Miyazaki, Y.; Schleifer, G.; Marutani, E.; Shah, H.; Sharma, R.; Goodman, R.P.; To, T.-L.; Bao, X.R.; et al. An engineered enzyme that targets circulating lactate to alleviate intracellular NADH:NAD+ imbalance. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, J.A.; Winter, V.J.; Eszes, C.M.; Sessions, R.B.; Brady, R.L. Structural basis for altered activity of M- and H-isozyme forms of human lactate dehydrogenase. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2001, 43, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, J.L.; Lacy, S.H.; Ku, W.-Y.; Owens, K.M.; Hernady, E.; Thatcher, T.H.; Williams, J.P.; Phipps, R.P.; Sime, P.J.; Kottmann, R.M. The Lactate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor Gossypol Inhibits Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Radiat. Res. 2017, 188, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.A.; Brassington, C.; Breeze, A.L.; Caputo, A.; Critchlow, S.; Davies, G.; Goodwin, L.; Hassall, G.; Greenwood, R.; Holdgate, G.A.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Novel Lactate Dehydrogenase A Inhibitors by Fragment-Based Lead Generation. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3285–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Sheng, X.; Jones, H.M.; Jackson, A.L.; Kilgore, J.; E Stine, J.; Schointuch, M.N.; Zhou, C.; Bae-Jump, V.L. Evaluation of the anti-tumor effects of lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor galloflavin in endometrial cancer cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppicelli, S.; Kersikla, T.; Menegazzi, G.; Andreucci, E.; Ruzzolini, J.; Nediani, C.; Bianchini, F.; Calorini, L. The critical role of glutamine and fatty acids in the metabolic reprogramming of anoikis-resistant melanoma cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1422281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaidi, B.; Hashimi, S.M.; Alqosaibi, A.I.; Alqurashi, N.; Alhazmi, S. Targeting the monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 and lactate dehydrogenase A LDHA in cancer cells with FX-11 and AR-C155858 inhibitors. 2023, 27, 6605–6617. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shao, M.; Li, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ding, W. Urban airborne PM2.5 induces pulmonary fibrosis through triggering glycolysis and subsequent modification of histone lactylation in macrophages. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 273, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, M.; Dong, Y.; Xu, B.; Chen, J.; Ding, Y.; Qiu, S.; Li, L.; Zaharieva, E.K.; Zhou, X.; et al. Circular RNA circRNF20 promotes breast cancer tumorigenesis and Warburg effect through miR-487a/HIF-1α/HK2. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, V.; Santarsiero, A.; Convertini, P.; Todisco, S.; Iacobazzi, V. Cancer Cell Metabolism in Hypoxia: Role of HIF-1 as Key Regulator and Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilegems E, Bryzgalova G, Correia J, Yesildag B, Berra E, Ruas JL, Pereira TS, Berggren PO. HIF-1α inhibitor PX-478 preserves pancreatic β cell function in diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Mar 30;14(638):eaba9112.

- Ilegems E, Bryzgalova G, Correia J, Yesildag B, Berra E, Ruas JL, Pereira TS, Berggren PO. HIF-1α inhibitor PX-478 preserves pancreatic β cell function in diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Mar 30;14(638):eaba9112.

- Hearne, A.; Chen, H.; Monarchino, A.; Wiseman, J.S. Oligomycin-induced proton uncoupling. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020, 67, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leontieva, O.V.; Blagosklonny, M.V. M(o)TOR of pseudo-hypoxic state in aging: Rapamycin to the rescue. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.; Kim, H.-G.; Jang, H.; Lee, J.; Chao, T.; Baek, N.-I.; Song, I.-S.; Lee, Y.M. Steppogenin suppresses tumor growth and sprouting angiogenesis through inhibition of HIF-1α in tumors and DLL4 activity in the endothelium. Phytomedicine 2022, 108, 154513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Du, J.; Wang, J. Albendazole inhibits HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis and VEGF expression in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 428, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian X, Nguyen M, Foote HP, Caster JM, Roche KC, Peters CG, Wu P, Jayaraman L, Garmey EG, Tepper JE, Eliasof S, Wang AZ. CRLX101, a Nanoparticle-Drug Conjugate Containing Camptothecin, Improves Rectal Cancer Chemoradiotherapy by Inhibiting DNA Repair and HIF1α. Cancer Res. 2017 Jan 1;77(1):112-122.

- Wada, H.; Maruyama, T.; Niikura, T. SUMO1 modification of 0N4R-tau is regulated by PIASx, SENP1, SENP2, and TRIM11. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Dai, A.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, X.; Zhang, X. SENP-1 enhances hypoxia-induced proliferation of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by regulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 3482–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Matsuhashi, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Umezawa, H. Distribution of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase and chloramphenicol-3-acetate esterase among Streptomyces and Corynebacterium. J. Antibiot. 1977, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-L.; Liao, P.-L.; Cheng, Y.-W.; Huang, S.-H.; Wu, C.-H.; Li, C.-H.; Kang, J.-J. Chloramphenicol Induces Autophagy and Inhibits the Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Alpha Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.; Robay, D.; Hindupur, S.K.; Pohlmann, J.; Colombi, M.; El-Shemerly, M.Y.; Maira, S.-M.; Moroni, C.; Lane, H.A.; Hall, M.N. Dual Inhibition of the Lactate Transporters MCT1 and MCT4 Is Synthetic Lethal with Metformin due to NAD+ Depletion in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 3047–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonen, A. The expression of lactate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4) in heart and muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 86, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droździk, M.; Szeląg-Pieniek, S.; Grzegółkowska, J.; Łapczuk-Romańska, J.; Post, M.; Domagała, P.; Miętkiewski, J.; Oswald, S.; Kurzawski, M. Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 (MCT1) in Liver Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alobaidi, B.; Hashimi, S.M.; Alqosaibi, A.I.; Alqurashi, N.; Alhazmi, S. Targeting the monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 and lactate dehydrogenase A LDHA in cancer cells with FX-11 and AR-C155858 inhibitors. 2023, 27, 6605–6617. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Rodriguez-Cruz, V.; Morris, M.E. Cellular Uptake of MCT1 Inhibitors AR-C155858 and AZD3965 and Their Effects on MCT-Mediated Transport of L-Lactate in Murine 4T1 Breast Tumor Cancer Cells. AAPS J. 2019, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, F.W.; Kettle, J.G.; Lamont, G.M.; Buttar, D.; Ting, A.K.T.; McGuire, T.M.; Cook, C.R.; Beattie, D.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Kavanagh, S.L.; et al. Discovery of Clinical Candidate AZD0095, a Selective Inhibitor of Monocarboxylate Transporter 4 (MCT4) for Oncology. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 66, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).