1. Introduction

The tactile Internet (TI) in the fifth-generation communication infrastructure (5G) and beyond 5G (B5G) has been considered a potential enabler for service categories such as Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) communication, Massive Machine-Type Communication (mMTC) and Ultra-Reliable Low Latency Communication (URLLC) [

1] to allow the interactions between humans, machines and Internet of Things (IoT) devices with audio and/or visual haptic feedback over a certain remote distance [

2,

3]. The TI communication infrastructure demands significantly high performance concerning ultra-low latency (≤ 1 ms), high bandwidth (30–300) GHz, ultra-high availability (

), ultra-reliable and high data rate support for augmented reality/virtual reality (AR/VR) applications.

Considering key enabling TI technologies such as software-defined networking (SDN), network slicing (NS), network function virtualisation (NFV), network coding (NC) and multiple access (MA) techniques, the TI communication infrastructure aims to improve their immersive, responsive and interactive services/applications. Thus, these technologies facilitate necessary dynamic infrastructure, optimising resource allocation and utilisation, offloading computational capabilities, and improving spectral efficiency, quality of service (QoS) and quality of experience (QoE).

According to the Ericsson Mobility Report [

4], a significant

surge was observed in mobile network data traffic between the 4

th quarter of 2022 and 2023, reaching a monthly consumption of 152 exabytes, contributing to approximately

billion mobile subscribers. In addition, the Cisco annual Internet report (2018–2023) [

5] stated that by 2023, global Internet users were estimated to touch

billion, constituting

of the world’s population. IoT devices will exceed three times the population, totalling

billion, whereas M2M (machine-to-machine) (a.k.a IoT) connections constitute half. The user devices surpassed the total connections, representing

, whereas the IoT applications forecasted substantial growth with a

compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

Despite the technological advancements in 5G communication infrastructure compared to first to fourth generations (1G - 4G) ones, the system capacity and spectral efficiency improvement fall short of the

increase mentioned in the International Mobile Telecommunications - 2020 (IMT - 2020) vision [

6].

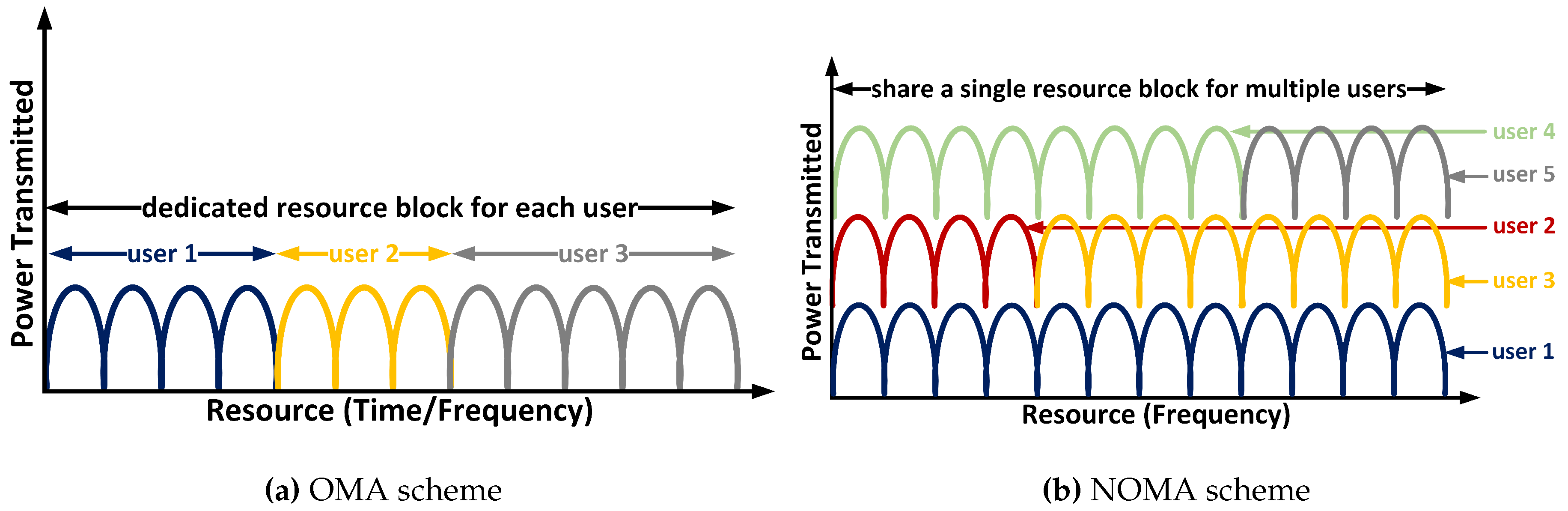

To improve the system capacity and spectral efficiency, the mobile and wireless communication infrastructure have employed several MA techniques from 1G to 4G, such as 1G - Frequency Division Multiple Access (FDMA), second generation (2G) - Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), third generation (3G) - Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA), and 4G - Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA), or combinations of these MA techniques. These MA techniques are adopted to share the available bandwidth among multiple users and reply on the resource (time/frequency) orthogonalisation, thus assigning different resources to individual users. Moreover, the bandwidth is wasted due to users’ utilisation of separate orthogonal resource blocks (RBs) using traditional MA techniques. These MA techniques are examples of orthogonal multiple access (OMA) schemes. Hence, these traditional MA techniques lack the competencies to serve multiple users having sensors and actuators simultaneously, rendering them unsuitable for a 5G communication infrastructure. In general, MA techniques can be structurally classified into OMA for 1G to 4G and non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) for 5G.

As mentioned, one of the high-performance enablers concerning parameters for TI communication infrastructure in 5G, the MA techniques, viz., NOMA, are complementing 5G New Radio (NR) robust, flexible and scalable framework. However, integrating NOMA can further resolve challenges and serve the demands of the proliferation of users, whether sensors or actuators, by utilising the same RB, according to 3GPP standardisation [

7]. This integration facilitates high system capacity, enhances spectral efficiency, supports massive connectivity, and reduces latency in the network [

8]. This technique concurrently assigns non-orthogonal resources amongst the multiple users whilst having some interference on the receiver side. In contrast, the traditional OMA techniques assign orthogonal resources solely to individual users, thus incurring challenges in achieving the required system capacity and spectral efficiency in 5G.

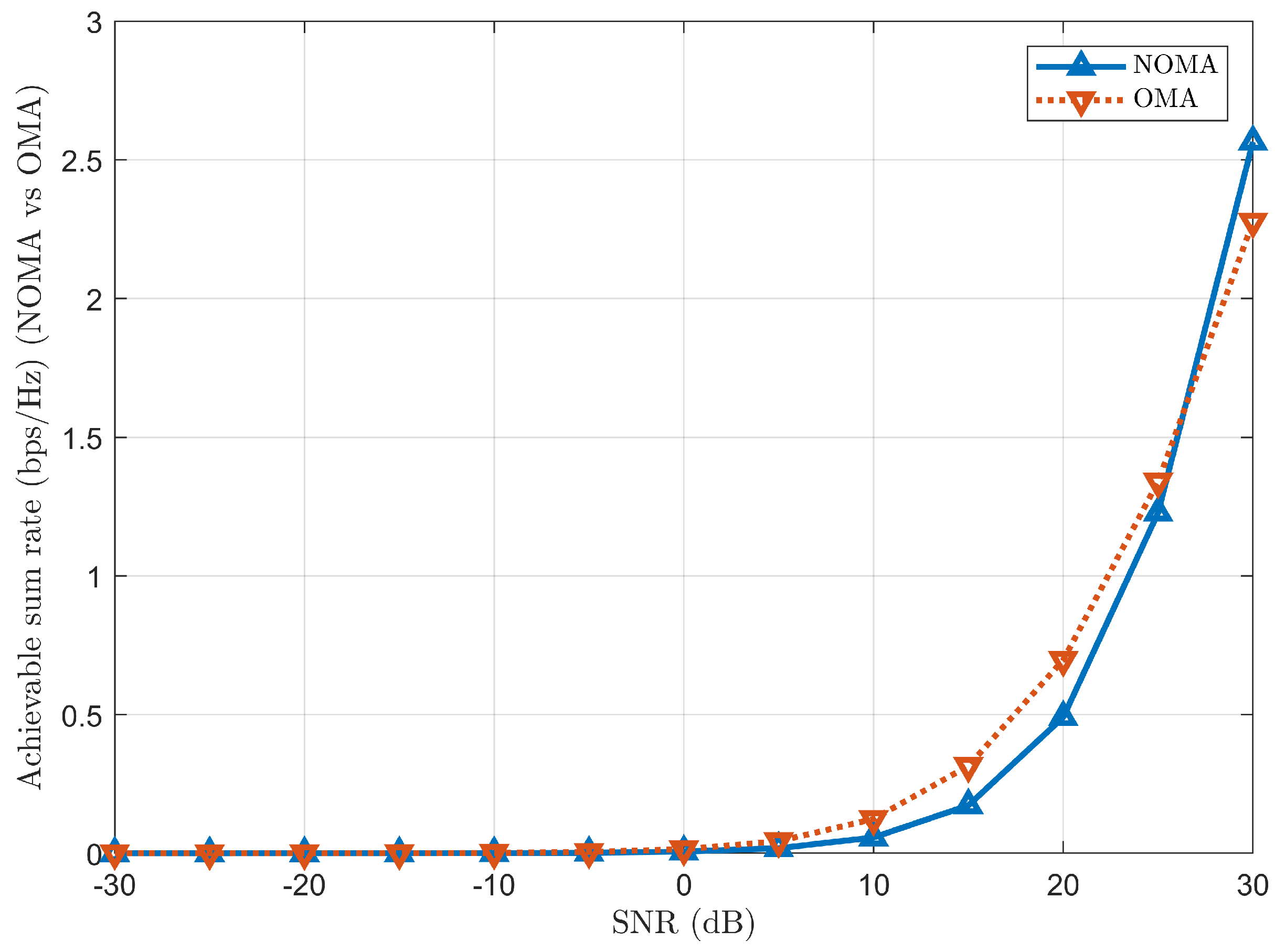

Figure 1 depicts the pictorial representation of NOMA when compared to OMA. Considering each user a sensor or an actuator, the power with respect to the resource graph is plotted to understand how the resources are allocated to the users in both cases.

Figure 1a represents the OMA scheme - how the users are orthogonal to each other and have a dedicated/assigned RB for each user (

,

, ...,

). On the other hand,

Figure 1b represents the NOMA scheme - how multiple users share a single RB, as the available bandwidth is not split across the users and assigns a single frequency channel to multiple users. Hence, the bandwidth wastage is minimised, and the system throughput is increased since the entire frequency spectrum is accessible to each user for transmission.

Consequently, it can be inferred that the NOMA environment is crucial and allows a dense deployment of sensors and actuators from users to share the assigned single RB, thus increasing the spectral efficiency and capacity compared to traditional OMA. Moreover, NOMA offers improved user fairness and QoS by having flexibility in power allocation (PA) and allowing users to be prioritised for stricter latency requirements by allocating them more power for faster data transmission. There are fewer waiting times to access the resources as users are sharing the resources concurrently. So this leads to overall reduced latency in data transmission. Finally, NOMA can effectively support heterogeneous networks with diverse user requirements and traffic characteristics. These benefits suit TI applications [

1], such as enhanced mobile broadband, massive connectivity and latency-sensitive applications.

In addition, NOMA techniques can be categorised into power-domain NOMA (PD-NOMA) and code-domain NOMA (CD-NOMA). In PD-NOMA, multiple users share the same RB. However, each user (whether a sensor or an actuator) is identified or allocated with varying power levels (coefficients) for transmission according to the channel conditions and distance from the base station (BS). Users with high channel gain (near BS) are allocated low power levels, whereas users with low channel gain (far from BS) are allocated high power levels. It utilises superposition coding (multiplexing) at BS and performs successive interference cancellation (SIC) at the receiver to detect and extract the users’ original data signals and vice versa. In CD-NOMA, multiple users share the same RB and are assigned distinct non-orthogonal codes, such as low-density spreading (LDS), sparse code multiple access (SCMA) and multi-user shared access (MUSA) [

9]. Increasing the number of users in CD-NOMA requires sophisticated algorithms for multi-user reception when non-orthogonal codes are adopted.

Furthermore, in PD-NOMA, both uplink (UL) and downlink (DL) transmissions play crucial roles in facilitating seamless message exchange between the user (whether a sensor or an actuator) and BS. Considering UL PD-NOMA, the simultaneous transmission happens from user to BS using the same RB and is distinguished by varying power levels. Conversely, for DL PD-NOMA, the simultaneous transmission happens from BS to the user, where BS assigns the proportion of power levels to multiple users based on the channel conditions and distance between BS and the user. Therefore, these PD-NOMA concepts enhance system capacity and optimise spectral efficiency, thus accommodating more sensors and actuators and reducing congestion in the TI communication infrastructure. Based on a sensor or actuator’s priority, channel conditions and power requirements, it can empower low-power communication to conserve energy and extend the battery life with less frequent need to replace it.

1.1. Research Challenges

While the PD-NOMA is broadly considered a promising multiple access technique which enhances the existing 5G-NR framework and B5G, several challenges [

10,

11] demand further investigation into implementing NOMA to improve capacity, spectral efficiency and latency. Considering resource allocation in NOMA, multiple users having sensors and actuators share the same RB. They are paired based on the distinct (strong and weak) channel gains, resulting in different PAs. At BS, the user signals are superimposed and transmitted, whereas at the user’s location, SIC is applied to received user signals to decode and extract the original signal. However, decoding the superimposed signal using SIC considering a perfect channel state information (CSI) can be challenging. Assuming a perfect CSI can pose real-time channel estimation errors, which may degrade the system’s performance [

12]. Therefore, new hybrid techniques and algorithms can be developed to yield a practical channel estimation.

In addition, NOMA’s system performance reduction may arise due to an imperfect SIC receiver [

13]. This imperfection depends on building efficient hardware to reduce computational complexity. The efficient PA among multiple users can pose another challenge in the NOMA system. Inefficient PA may lead to interference in the received user signal, unfairness among paired users and higher outage probability, thus resulting in performance degradation. Moreover, most researchers focus on adopting a two-user pairing or sensor clustering for easy superimposition at BS and to reduce SIC complexity at the receiver’s end. To cater to the growing demands of mMTC devices, multi-user pairing strategies or sensor clustering must be formed to take complete advantage of NOMA systems. Finally, due to the heterogeneous wireless network, a need for hybrid-NOMA (NOMA with other multiple access techniques) arises to address the diverse needs of devices through BS. Integrating NOMA with other multiple access techniques can be challenging, optimising the system’s performance.

1.2. Motivation

PD-NOMA offers several significant benefits over traditional MA techniques, such as enhancing capacity, increasing spectral efficiency, improving user fairness and QoS, mitigating interference and serving multiple users with the same RB, thus addressing shortcomings of current communication infrastructure and directing future networks. Therefore, PD-NOMA flexible PA enables and prioritises eMBB, mMTC and URLLC TI applications/services with required resources for seamless operation. However, research in PD-NOMA is needed to improve system performance further and address the aforementioned challenges, such as PA algorithms, hardware impairments, receiver design with imperfect SIC and CSI, and integration of PD-NOMA with other MA techniques to cater to the diverse needs of user devices. Subsequently, it is driven by the need for an efficient, flexible, and user-centric communication infrastructure that meets the ever-growing demands of future networks.

1.3. Research Contributions

In accordance with the findings from the literature review and to the best of our knowledge, the research still lacks in the field of PD-NOMA for TI applications. The performance analysis and evaluation of PD-NOMA in TI have not been comprehensively conducted in the past. Therefore, in this research, we have developed a novel downlink PD-NOMA communication scenario for TI employing multiple sensors and actuators (e.g. users), focusing on transmitted signals from a BS and processed received signals at the user’s end. Furthermore, the key performance indicators (KPIs) are derived, discussed, and evaluated to compare the performance characterisation of NOMA and OMA schemes. The main contributions of this paper are highlighted below.

We developed an analytical system model incorporating signal-to-interference and noise ratio (SINR), sum rate, fair power allocation (PA) coefficients and latency among the available NOMA users.

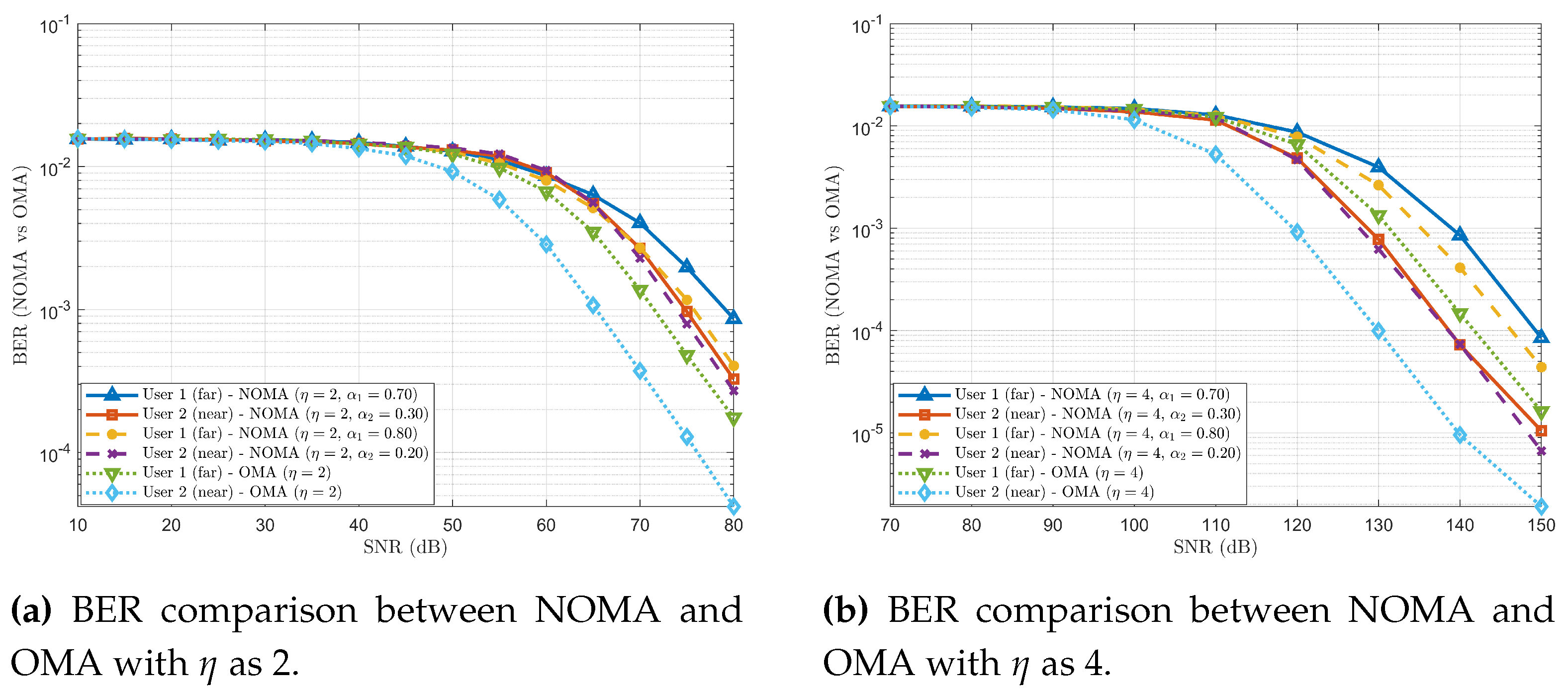

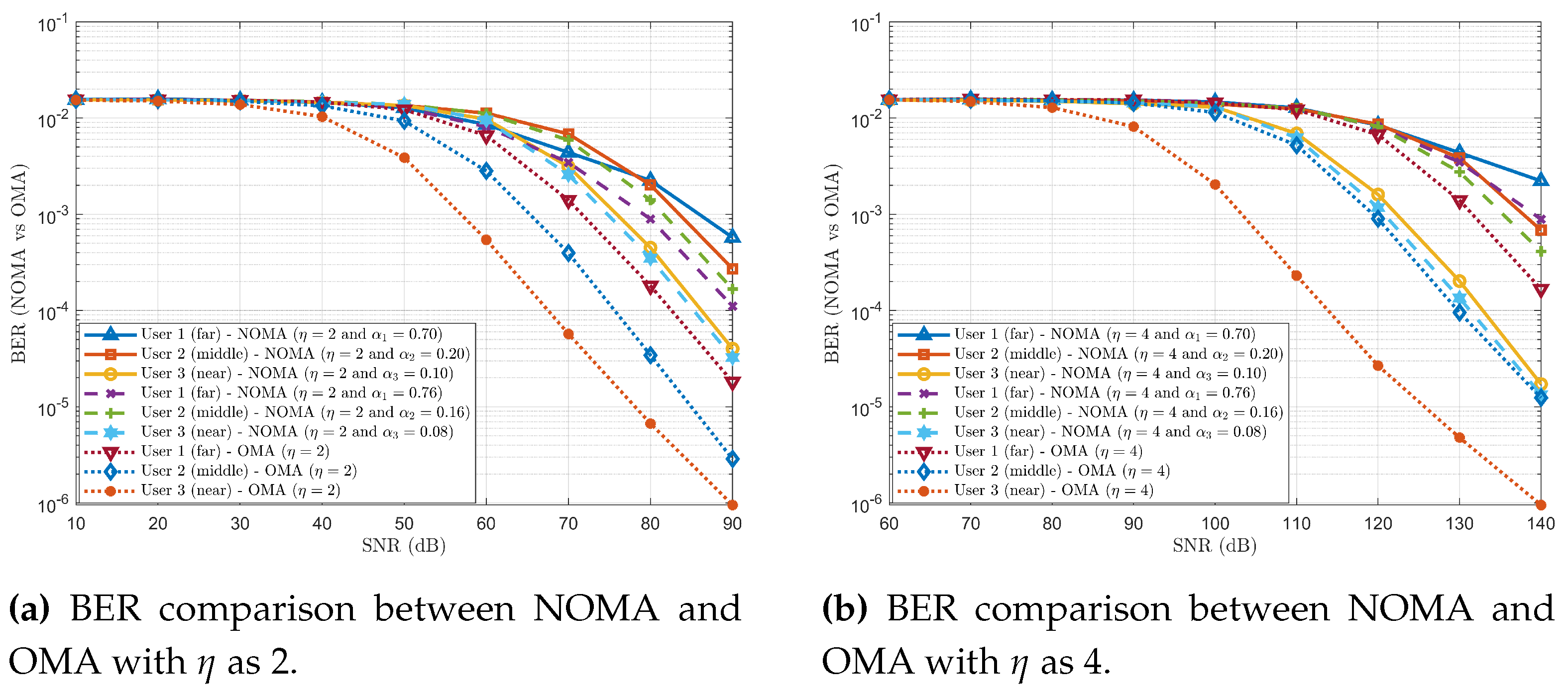

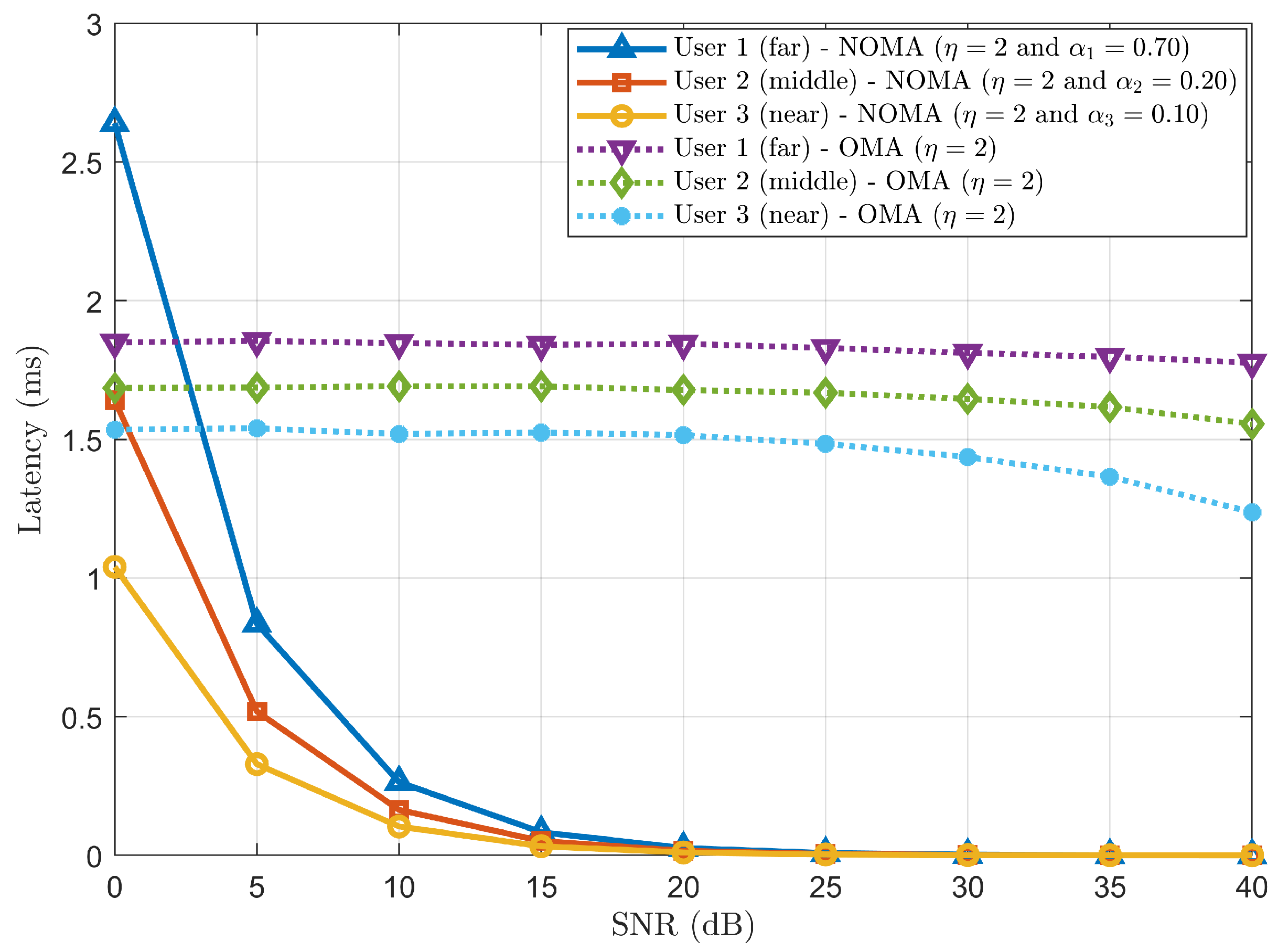

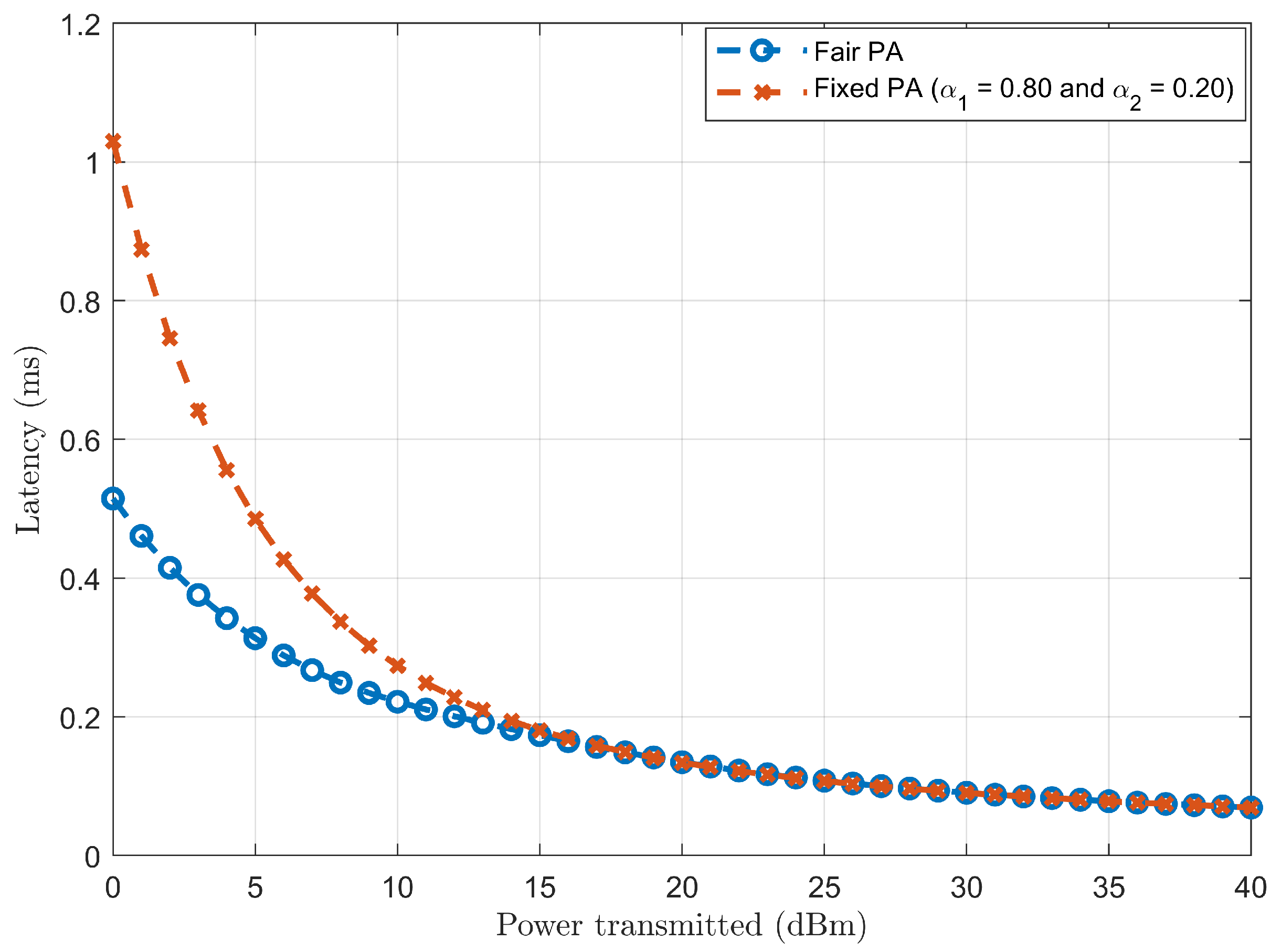

We compared and analysed BER for NOMA and OMA schemes with varying path loss exponent and fixed PA coefficients using two- and three-user scenarios. To this end, we compared the achievable sum rate and latency trends for NOMA and OMA schemes for fixed PA coefficients.

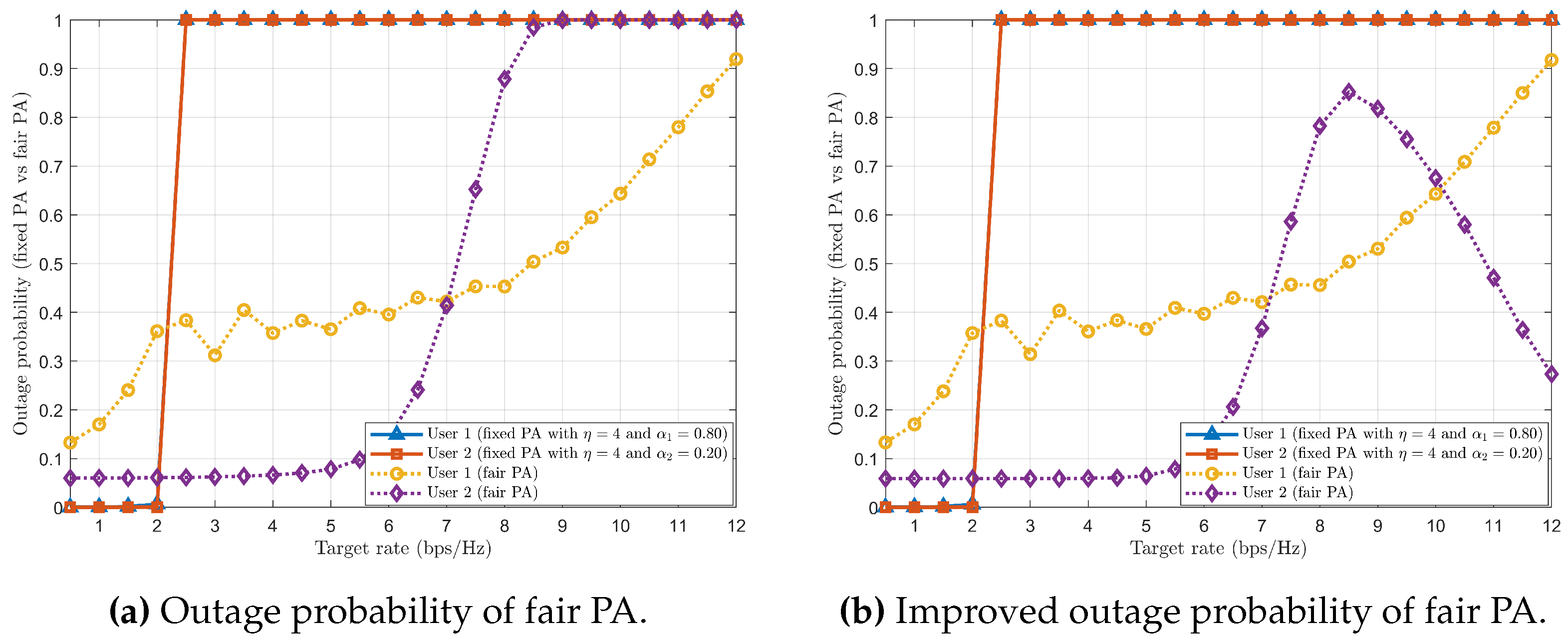

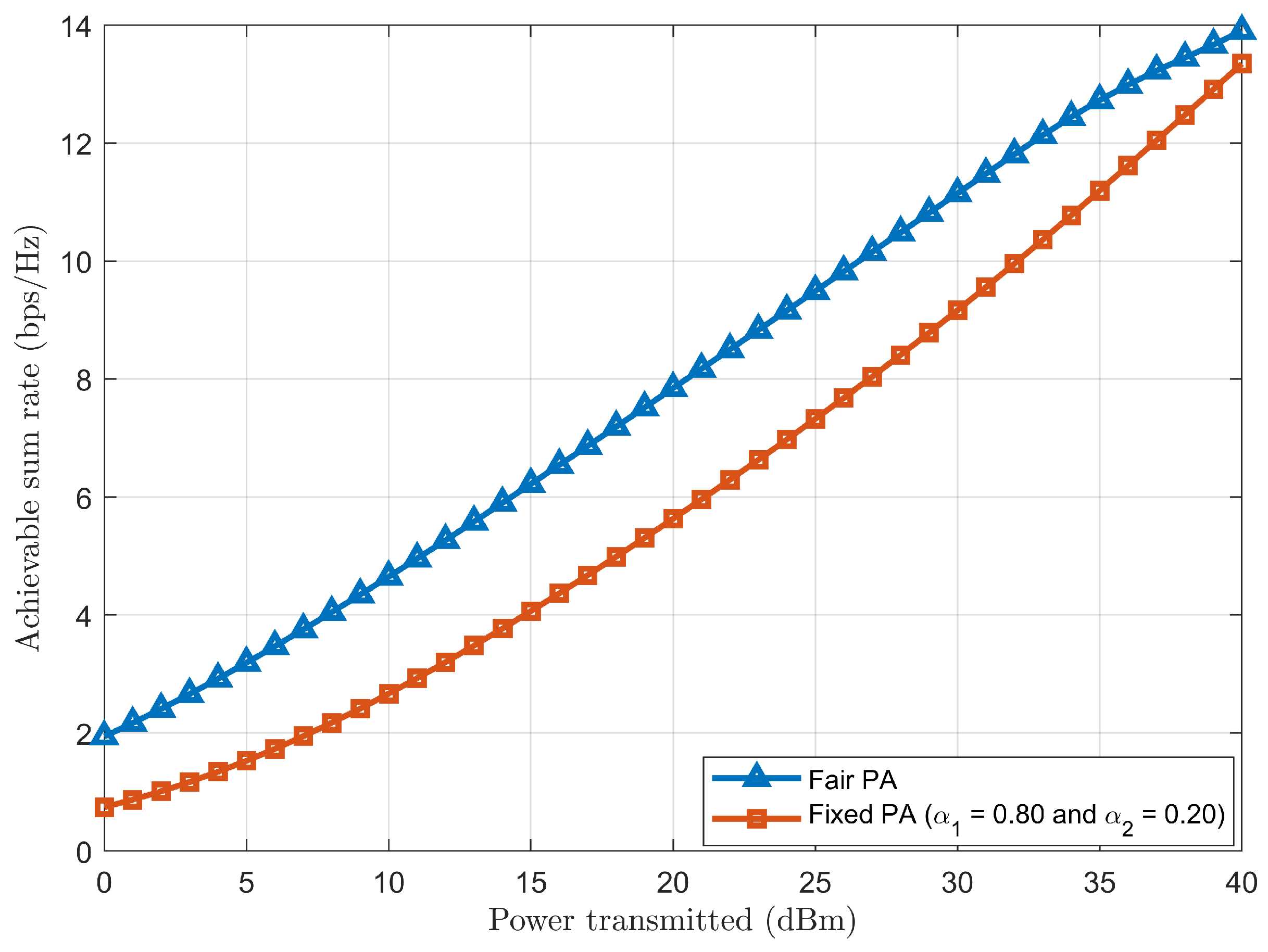

Finally, the outage probability, achievable sum rate and latency trends are compared and analysed for fixed and fair PA coefficients. To this end, the performance trend of outage probability for NOMA users in varying fixed PA coefficients is also analysed.

1.4. Structure of the Article

The rest of the article is organised as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review relevant to the NOMA scheme used in the network.

Section 3 describes the proposed system model for the downlink PD-NOMA communication scenario for TI. This section also includes the derivation and analysis of SINR, achievable sum rate, fair PA and latency. The performance evaluation is presented in

Section 4. The simulation results are also presented in this section.

Section 5 concludes our work with future directions. Finally,

Table A1 lists the abbreviations and their explanation (see Appendix).

2. Related Work

Several research studies have been conducted on NOMA to enhance system capacity, improve spectral efficiency and reduce latency. In [

14], NOMA is adopted on 5G communication infrastructure (test-bed) with the objective of minimising latency and optimising resource allocation for autonomous vehicles (AVs). Also, some challenges for implementing and adopting NOMA for 5G-based applications are highlighted for researchers and AV manufacturers. A novel cloud-based queuing model for TI is proposed in [

15] by utilising the PD-NOMA strategy. This model uses a baseband processing unit (BBU) and radio remote head (RRH) queuing delays for tactile end-users. Resource allocation is formulated to reduce the latency between tactile end-users. The transmit power is reduced by choosing a dynamic approach of fronthaul and access delays rather than a fixed approach. Finally, the energy efficiency of PD-NOMA and OFDMA is compared.

In [

13], the critical features of NOMA are reviewed and highlighted merits and demerits against other OMA strategies. The features of several NOMA schemes, such as PD-NOMA, SCMA, MUSA and pattern division multiple access (PDMA), have been discussed. In addition, the KPIs such as sum rate, energy efficiency, and BER are compared between NOMA strategies. Thus, NOMA has the potential to achieve the objectives of the required KPIs. On the other hand, the authors in [

16] have proposed deep learning-based grant-free NOMA to tackle and minimise the ultra-low latency and ultra-reliability requirements in massive access scenarios. They mentioned that the combination of grant-free access and NOMA can be leveraged and is a promising approach for tactile IoT. However, random interference is caused, which lowers the system’s reliability. Hence, a grant-free NOMA-based neural network model and a novel multi-loss function are considered highly suited for automated applications in tactile IoT. Simulation results of the proposed model outperform the traditional grant-free NOMA strategies.

Moreover, in [

17], the NOMA in mobile edge computing (MEC) enabled wireless tactile IoT scenario is investigated and optimisation algorithms for system and user performance. The proposed network model incorporates an MEC server at the access point, thus supporting computation for two sensor clusters. The system and cluster heads’ performance using the successful computation probability (SCP) is assessed, mainly focusing on high signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) for a comprehensive understanding. The simulation results of the proposed network model outperform and boost system performance compared to traditional OMA strategies. The authors in [

18] explore and analyse the application-specific NOMA-based communication infrastructure for TI, allowing the non-orthogonal RB sharing among 5G generic services such as eMBB, mMTC and URLLC devices to a shared BS. A comparative analysis of NOMA and OMA is shown concerning the sum rate and number of users. Various NOMA variants are discussed to check the feasibility of future low-latency TI applications/services.

To meet the requirements of high spectral efficiency, ultra-low latency, and multi-user connectivity, the authors in [

8] have considered NOMA a potential solution which allows some degree of interference on the receiver side. In contrast, the OMA technique may not meet the strict previously mentioned requirements. Here, they have focussed on providing a novel NOMA model, including uplink (UL) and downlink (DL) transmissions in multiple input multiple output (MIMO) and cooperative communication scenarios. Hence, the performance of NOMA and OMA are compared to analyse the system in terms of spectral efficiency, sum rate, and BER. In [

19], authors have predominantly investigated the implementation of NOMA on a software-defined radio (SDR) platform. They have highlighted SDR as a flexible platform for testing and implementing 5G and B5G technologies. In addition, various SIC receivers such as Ideal SIC, Symbol-level SIC, Codeword-level SIC, and Log Likelihood Ratio (LLR) based receivers are mathematically evaluated and analysed. When NOMA is compared with OMA with simulation results, NOMA showcases its superiority over OMA in terms of KPIs.

Furthermore, a survey on the NOMA system is presented in [

20], focussing on error rate analysis. The enhanced NOMA strategies, which consist of constellation diagrams, multicarrier systems, and detector designs, are discussed, along with research problems and future directions. In [

21], a discussion of a deep learning technique for the NOMA systems is presented. The emphasis is given to deep learning-based NOMA systems for solving communication issues. These NOMA systems can be integrated with potential technologies such as MEC, MIMO, Intelligent Reflecting Surfaces (IRSs) and simultaneous wireless and information power transfer (SWIPT). Also, the focus has been given to KPIs such as SIC, CSI, user fairness, and other valuable parameters.

Considering the IRS, [

22] has addressed the issues related to harnessing the performance of wireless networks in 1G to 5G propagation environments. The issues can be resolved in the sixth generation (6G) by employing the IRS with NOMA. The designs and challenges related to IRS-based NOMA systems are comprehensively discussed with a detailed analysis of the communication framework. In [

23], a survey is conducted based on combining the benefits of NOMA and cell-free massive MIMO systems and a detailed review of how the performance can be increased. Moreover, the challenges of combining cell-free massive MIMO systems with other potential technologies are discussed.

Visible light communication is a potential solution for high-speed data communications. In [

24], the authors have conducted a comprehensive review of NOMA techniques with the involvement of visible light communication systems. They also discussed the limitations and challenges of integrating NOMA with visible light communication systems and the role of machine learning and physical layer security. The authors in [

25] have reviewed NOMA-enabled MEC systems in depth, focusing on the issues, challenges, and shortcomings that arise. They have claimed that integrating NOMA with MEC will bring umpteen performance characteristics to 5G and B5G communication infrastructure, such as energy efficiency, latency, throughput and massive end-user connectivity.

To overcome the issues related to poor channel quality and disconnected communication from BS to users, the work in [

26] has analysed the BER and outage probability for multi-hop decode and forward relay-assisted NOMA systems. The BER and outage probability equations are also derived by considering imperfect SIC and CSI. The proposed model’s simulation results depict the superiority over traditional OMA systems. The authors in [

9] have focussed on the efficient strategies to integrate NOMA in 5G and 6G systems. This integration can be beneficial for UL and DL application environments under the 3

rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) standardisation.

The author in [

27] has focussed on optimising PA coefficients to gain optimum proportional fairness in PD-NOMA transmission with complete or limited SIC. The numerical results illustrate the impact of complete or limited SIC on the system performance with sum rate loss due to proportional fairness. Similarly, [

28] considers a hybrid automatic repeat request protocol for PD-NOMA with proportional fairness on the fading channel. It analyses the system performance for different symmetric and asymmetric scenarios concerning throughput, outage probabilities and delays with varying PA.

3. System Model

A NOMA-based power-domain multiplexing system model is considered mathematically, consisting of a BS with users (, , ..., ). Here, we are considering a downlink NOMA communication scenario. At the transmitter side, the users’ messages are multiplexed using superposition coding, whereas, at the receiver end, the received users’ messages are demultiplexed (decoded) to retrieve the original message and perform successive interference cancellation (SIC) to remove interference from other user’s messages.

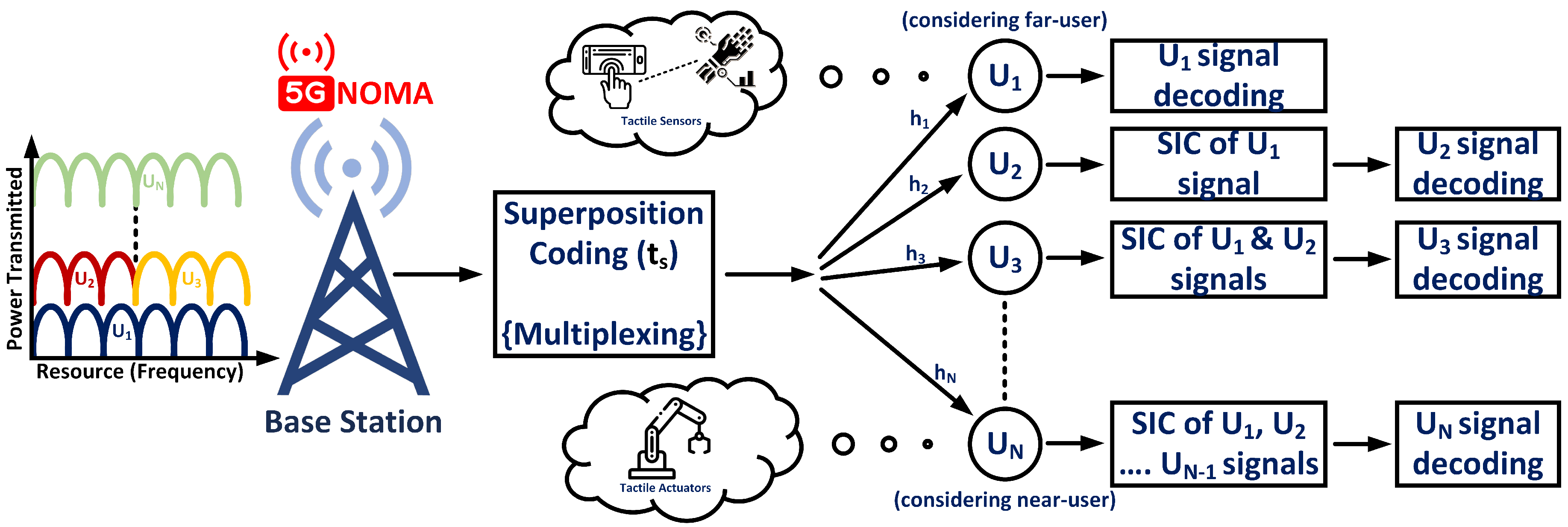

3.1. Downlink PD-NOMA Communication Scenario

Figure 2 represents the downlink power-domain communication scenario in TI. Let

,

, ...,

denote users’ messages to be transmitted from the BS with transmitted power as

. Let the PA coefficients be

,

, ...,

with the corresponding channel coefficients as

,

, ...,

.

Let us consider to be the farthest user, followed by to be the nearest user to the BS.

As superposition coding is performed at the BS, the transmitted signal (

) from BS is given by,

In short,

at

user can be written as,

Therefore, the received signal (

) at

user is given by,

Comparing Eqs.

2 and

3,

can be written as,

where,

is additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) with mean 0 and variance

.

By considering Eq.

4, the

for User 1 (

= farthest user), where

, will be,

As User 1 is allocated with the highest power coefficients (), the component of User 1 is the desired and dominant signal, and other components are considered undesired (interference).

Along the same lines,

for User 2 (

= relatively near to BS), where

, will be,

As User 2 is allocated with a relatively lower power coefficient (), the component of User 2 is considered as desired but not dominant. The dominant signal is still the User 1 signal component, which is considered undesired (interference), along with other remaining user signal components. Hence, SIC is performed on the to decode/retrieve the user’s original message/signal to remove undesired (interference) signal components.

3.2. SINR Analysis

To retrieve the original message from the received signal (), the particular users’ received signal must be directly decoded, considering other signal components as interference.

Therefore, to decode

signal for User 1 from Eq.

5, the instantaneous SINR for User 1 is given as,

where,

is channel gain for User 1.

Similarly, to decode

signal for User 2 from Eq.

6, the

must decode the User 1 signal and perform SIC as User 1’s received signal component is an undesired but dominant signal. Hence, after performing SIC, the resulting

will be,

Once User 1’s dominant signal component is removed from Eq.

6, resulting in Eq.

8, the

signal can be directly decoded so that User 2 can have the desired and dominant signal after SIC. Hence, other remaining user signal components can be treated as interference. Hence, the instantaneous SINR for User 2 is given as,

where,

is channel gain for User 2.

Therefore, the SINR for

user can be expressed as,

where,

is channel gain for

user.

3.3. Sum Rate Analysis

The achievable sum rate of

user for downlink NOMA can be computed as,

From Eq.

10, Eq.

11 (

) can be written as,

Therefore, the overall achievable sum rate for NOMA downlink can be expressed as,

To evaluate NOMA scheme at higher SNR, the variance

tends to 0 (

). Hence, from Eq.

13, the achievable sum rate can be approximated as,

3.4. Fair PA Analysis

The fair PA in NOMA downlink communication is crucial to ensure that all system users (, , ..., ) have a guaranteed QoS and maximise the sum rate. Thus, fair PA promotes user fairness, balances interference (undesired signal components), and enhances spectral efficiency.

Moreover, the PA coefficients (, , ..., ) are directly dependent on channel conditions. Without considering the channel conditions, the fixed PA coefficients are used, where the outage probabilities of the users are higher with a lower sum rate (bps/Hz).

Considering the CSI, the PA coefficients can be fairly optimised to improve the system performance. The fair PA focuses on the far user (User 1 in our case), as the far user is weak and located relatively away from BS compared to other users.

To better evaluate the NOMA scheme, let us consider two users (User 1 – far user and User 2 – near user) presented in the system. From Eq.

12, the achievable sum rate for Users 1 and 2, respectively, can be given as,

Hence, in this case, the PA coefficients (

and

) are designed/derived by setting up the target rate (

) for the far user (User 1), which is less than or equal to the sum rate, i.e.,

, from Eq.

15. Once

for User 1 is met, the optimised PA coefficients can be derived instead of having a fixed PA.

Therefore, Eq.

15 becomes,

Let us consider

We know that the sum of the PA coefficients is equal to 1 as we have two users (User 1 and User 2 having PA coefficients

and

, respectively),

. Therefore, Eq.

18 implies,

Hence, Eq.

19 can be also written as,

Once the PA coefficient (

) of a far user (User 1) is calculated, the PA coefficient (

) of a near user (User 2) can be calculated using,

In this case, if the calculation for the term (let us consider 20), then , which does not satisfy the condition .

If is designed to have 20, then User 1 will meet the target rate (). But, if , User 1 will not meet , leading to an outage condition. Moreover, cannot hold the value 20, which violates the condition . Consequently, even if User 1’s holds the value 1 (not meeting the considered condition ), User 1 will be in an outage situation.

In contrast, if , then will be 0. This infers that User 2 will not have any PA coefficient. Hence, User 2 will also be in an outage condition.

The solution for this outage problem of Users 1 and 2 can be resolved by setting up as 0 (no PA) and as 1 (entire PA). To keep User 1 away from the outage situation, the considered value of must be kept at 20. But, the ideal value of cannot exceed 1, i.e., for , User 1 will still be in an outage and not meet the desired target rate. Therefore, allocating the entire PA to User 2 () can be considered to a point where allocating any PA to User 1 will not matter or affect the outage condition, i.e., User 1 will be in outage condition even if PA is done. Thus, User 2 will not be in the outage, achieving a higher sum rate (bps/Hz).

3.5. Latency Analysis

In the downlink power-domain communication scenario in TI, latency can be defined as the delay incurred when the signal (ts) is transmitted from BS until it is received by users (, , ..., ). This latency includes delays such as transmission delay, propagation delay, queuing delay and processing delay.

The transmission delay (

) is the time required to transmit data packets over the communication channel. This delay considers the sum rate (Eq.

15 and Eq.

16) or set target rate (Eq.

17) of users and the amount of data to be sent (packet size). Thus,

is given by,

where, transmission rate = sum rate in (bps/Hz) × system bandwidth (Hz).

Moreover, the propagation delay (

) is the time required for the data packets to travel the physical distance between the BS and the user. This delay also relies on the transmission rate of the signal and thus is given by,

where, speed of light =

m/s.

The queuing delay () is the time required to wait in queues at the BS before data packet transmission. This delay may arise due to network congestion or scheduled multiple users based on channel conditions. On the other hand, the processing delay () is the time required to process superposition coding (multiplexing) at the BS and SIC decoding at the receiver’s side.

Hence, the overall latency (

) for a particular user will be given by,