Introduction

There is growing recognition that many individuals accessing various health and social care services may have undergone past events that can result in traumatic experiences (Felitti, 1998). A significant portion of contemporary understanding regarding trauma-informed care can be attributed to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study (Felitti, 1998). This extensive retrospective study, involving over 17,000 predominantly White middle-class Americans, not only revealed the prevalence of childhood trauma but also highlighted its profound impact on physical, mental, and emotional health, influencing morbidity and lifetime mortality (Huges et al., 2017; Hopper et al., 2010; Felitti, 1998). Subsequent research has further validated and replicated the connection between adversity and lifelong health outcomes (Madigan et al., 2023). Traumatic experiences have an accumulative effect on individuals, with a higher number of exposures correlating with increased likelihood of later physical and mental health morbidities (Read, 2007; Shevlin, 2008).

Despite the significance of the ACE research, there exist several limitations in terms of the sample used, the scope of adversity measured, the absence of recognition of protective factors, and the oversimplification that not all adversity is experienced as trauma or diagnosable. For instance, factors such as personality type, social support networks, attachment style, and coping abilities may serve to mitigate the onset of trauma following adverse events or sequences of events (Barazzone et al., 2019; Campodonico et al., 2021; Fritz et al., 2019; Greene et al., 2018; Kornhaber et al., 2016).

However, for many people, substance use and addictions are developed as a way to cope with such adversity and trauma (Devries et al., 2014; Kuksis et al., 2017; Lawson et al., 2013; Thege et al., 2017). Khoury et al. (2010) found high rates of lifetime dependence on various substances (39% alcohol, 34.1% cocaine, 6.2% heroin/opiates, and 44.8% marijuana) in a population of individuals who had experience childhood adversity. The prevalence of comorbid substance use dependency and post-traumatic stress disorder is in the range of 25%–49% (Bonin et al., 2000; Driessen et al., 2008; Gielen et al., 2012). The extant literature on substance use interventions demonstrates robust research evidence of the effectiveness of various psychosocial approaches across different treatment settings (Bates et al., 2017; McGovern et al., 2017).

Similarly, a host of psychosocial therapies have been identified as being effective in the treatment of trauma (e.g. Benish et al., 2008; Jericho et al., 2020; Thielemann, et al., 2022). However, the treatment system itself can promote or impede healing based on a number of variables. For example, in a study with 900 practitioners, 30 clinics and 150,000 service users, Mahon et al. (2023a) demonstrated that even after variables such as diagnosis, level of distress and how effective the practitioner is are controlled for, the organisation that a service user attends impacts treatment outcomes, possibly through organisational climate. As such, organisations that can create an environment conducive to healing are more likely to provide an optimal level of care (Mahon et al., 2023a). Trauma informed care is increasingly being identified as one way to achieve a healing environment (Bloom, 2017; Harris and Fallot, 2001; SAMHSA, 2014; Mahon, 2022; Raja et al., 2015).

Trauma informed care is a system wide organisational strategy that seeks to limit the extent that individuals are at risk of being re-traumatised during interactions with service providers. Trauma informed care is a universal organisational approach, the rationale for a universal approach is based on the high prevalence of trauma and adversity in those accessing a range of social services. For example, in general population surveys Benjet et al. (2016) highlight that 70% of 68,894 individuals from 24 countries identified as having experienced a traumatic event, and 30.5% had exposure to 4 or more multiple traumatic events. This epidemiological research suggests that exposure to interpersonal violence has the strongest relationship with trauma experiences, and as such, in cases of limited resources, these may be best directed to those at risk of experiencing interpersonal violence.

Trauma informed organisations may or may not provide trauma specific therapies, however, they do utilise principle-based approaches. For instance, Harris and Fallot (2001) identify safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment to be core principle-based values. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) added two further principles, peer support, and cultural and gendered experiences. SAMHSA (2014 p.9) defines trauma informed systems of care as being underpinned by the ‘4 R’s’

“A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization”

For policy and practice to move further towards the uptake of an intervention, then evidence synthesis is often considered the gold standard of research. Trauma informed care has been the focus of a number of systematic reviews in allied health and social care settings with findings of effectiveness varying among youth populations, and often at high risk of bias (e.g. Bailey et al., 2019; Berger 2019; Newton et al., 2024; Roseby and Gascoigne 2021). In a review of the evidence in out of home care, Bailey et al. (2019) suggest that trauma informed care may have significant positive outcomes on children’s life’s, however, almost all studies were at high risk of bias. Roseby and Gascoigne (2021) report outcomes in academic and academic-related outcomes including attendance, disciplinary referrals, suspension, and academic achievement, as well as school attachment, resilience, and emotional regulation. However, findings were inconsistent across studies in this review. Kelly et al. (2023) describe how restrictive practices were reduced among employees caring for young people after the implementation of trauma informed care, however, the included intervention protocols were insufficiently outlined.

Other systematic reviews with adults in community, mental health, and hospital settings had similar finding. In a review of trauma informed care in primary care and community mental health, Lewis et al. (2023) report some positive benefits in service users readiness for disease management, and access to services; service users and providers felt safe; and one study noted service user quality of life and experience of pain management improved. However, the authors suggest that evidence of effectiveness was limited and conflicting. Brown et al. (2022) conducted a review of the literature in emergency medicine and found that all 10 studies found a positive benefit either on clinicians or service users, however, similar to other studies, they note that outcome data remains limited. Fernández et al. (2023) reviewed the literature of TIC where studies had an implementation component and found benefits in improved functioning of service users, improved accessibility, and quality of services provided. Once again, the quality of the included studies makes it difficult to drawn firm conclusions.

Other evidence syntheses explored the implementation of trauma informed care highlighting various facilitators and barriers across individual and organisational domains. In their review of implementation factors which included 27 studies predominately in mental health, Huo et al. (2023) describe a range of facilitators and barriers existing; such as leadership engagement, finances, staffing and policy, while external factors such as inter-agency collaboration and the actions of other organisation can promote or impede implementation. Flexible employee training and refresher courses can act to escalate implementation, as can the use of service user feedback and the collection of service data to demonstrate progress and outcomes. Bryson et al. (2017) reviewed the literature in psychiatric and residential settings inclusive of 13 studies and found that five factors were essential to successful implementation; commitment from senior leadership, employee supports, service user involvement/engagement, alignment of policy, and using data to motivate change in practices. Lewis et al. (2023) underscore the importance of moderating factors on TIC implementation, such as; governance, health system values, organisational culture, social determinants of health, buy in from employees, and funding). However, to data, no systematic review has synthesised the evidence in substance use settings with a focus on implementation factors.

1.1. Context

Trauma informed care is increasingly becoming a service delivery model with proponents advocating for its benefits. However, as noted in the literature review section, the quality and scope of evidence to date is rather limited in various allied health and social care settings. Although some studies suggest positive outcomes for service users, and employees, implementation of TIC is not without difficulties. No systematic reviews have been conducted in substance use setting. Therefore, the present review seeks to address this gap in knowledge and can add important findings to the literature, and offer further directions for research. The two questions informing this systematic review are:

How effective is the implementation of organisational trauma informed care on service user and employee outcomes

What trauma informed implementation domains are considered in the substance use literature to implement organisational trauma informed care.

2.0. Methods

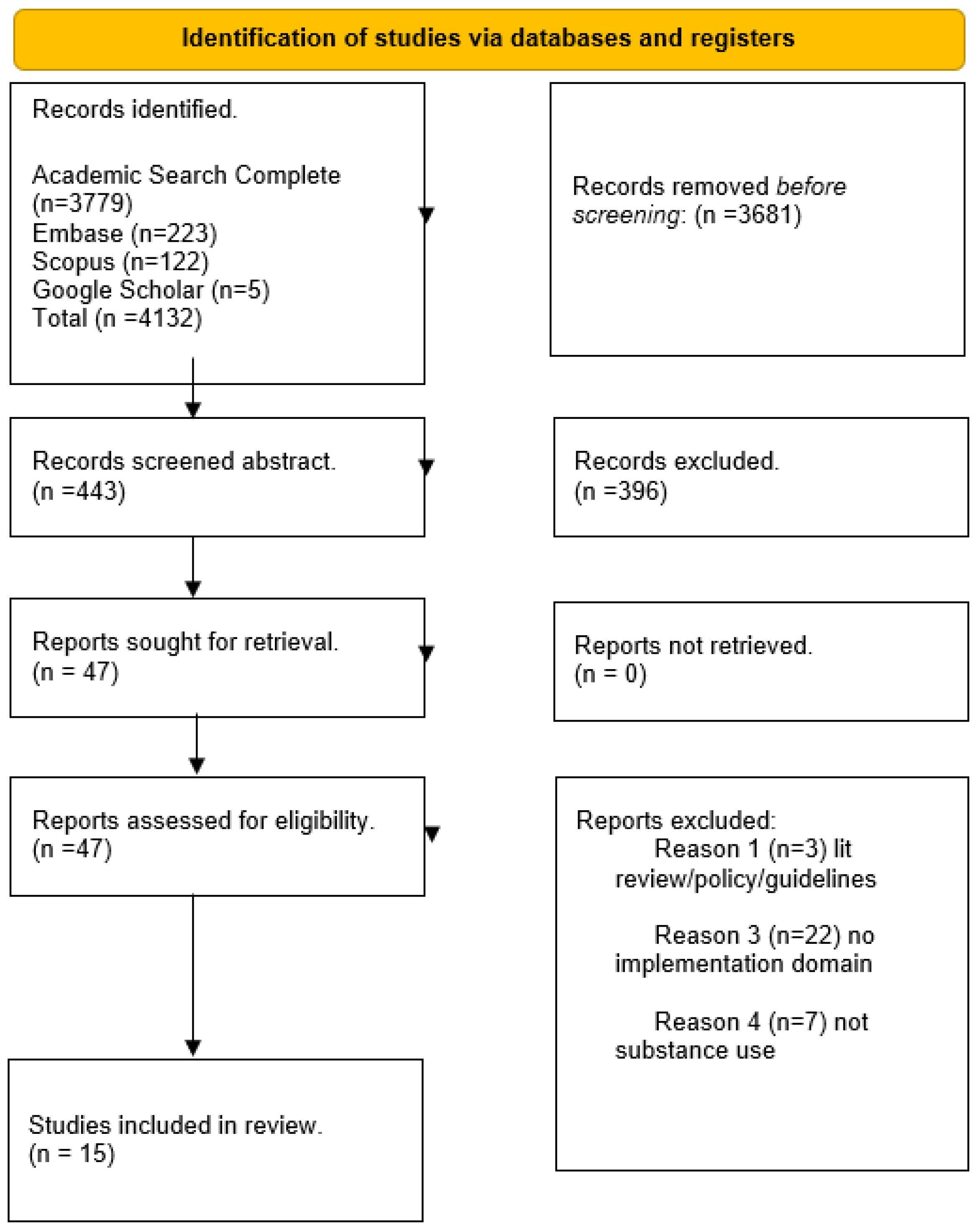

The preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) was followed (Page et al., 2021). Findings are analysed using a framework based on the 10-trauma informed implementation domains and reported using a narrative synthesis (Popay, 2006). Meta analysis is not undertaken due to the level of heterogeneity. Study qualities were appraised using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Study inclusion criteria was developed using the population, concept and context (PCC) framework due to the complex nature of system wide interventions (Peters et al., 2020; Pollock et al., 2023). Studies were included if they reported on empirical research, based on trauma informed care in substance use setting, and had at least one of the following 10 trauma informed care implementation domains; governance and leadership; policy; physical environment of the organization; engagement and involvement of people using services, cross-sector collaboration; screening, assessment, and treatment services; training and workforce development; progress monitoring and quality assurance; financing, and evaluation.

Substance use settings for the purpose of this review include organisations in the public, private or charity sectors delivering residential or community treatment to adults or families. Treatment is understood to include psychosocial (therapy and case management) and medical interventions such as opioid substitute treatment. Studies must of been conducted in English and peer reviewed.

Table 1 highlights the inclusion/exclusion criteria and the PCC framework.

2.2. Search Strategy & Selection

Three databases, Academic Search Complete, Embase and Scopus supplemented with searches in bibliographies and Google Scholar. The search strategy was employed during January-February 2024 with the last search conducted on 24th February. No exclusion criteria were applied to the search.

The full database search can be found in

Table 2. The search strategy yielded 4,132 articles, of which (N=15) are included. Articles were downloaded into Mendeley for appraisal. After duplicates were removed, the title and abstract of relevant articles were appraised based on the inclusion criteria (PCC), with full text appraisal also carried out.

Figure 1 PRISMA flowchart (Page et al., 2021) provides a graphic illustration of the reduction process.

2.3. Reporting Results

Data were extracted using an adapted version of the Joanne Briggs Institute Data Extraction Form for Review for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (Aromataris et al., 2015). Headings were developed iteratively, and piloted with the first three articles. Data were extracted under the following headings; author and year, study location, sample size, aims, characteristics/model of intervention, methods, and trauma informed implementation domains, comparisons and results. Findings are mapped onto the 10 trauma informed implementation domains, and reported using a narrative synthesis (Popya, 2006).

Table 3.

Data extracted from studies.

Table 3.

Data extracted from studies.

| Author & Year |

Country |

N |

Aim |

Characteristic of Model/Intervention |

Methods |

Comparison |

Findings |

Trauma informed implementation domain |

MMAT Quality appraisal of study |

| Finkelstein Markoff 2005 |

America |

328 |

To evaluate the WELL Project as part of the larger Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence

Project (WCDV) project |

Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence

Project (WCDV) |

quasi-experimental |

Treatment as usual |

the WELL Project is the possibility

of using a relational, collaborative model to bring about change at multiple levels of a service delivery system. Strategies such as bringing all

stakeholders to the table, especially consumers, and then engaging in

values clarification, providing cross-training, and creating a safe envi ronment for dialogue are effective in preparing the ground for change.

Working together, stakeholders can then create a model for service

delivery that best meets the needs of all concerned. |

Cross sector collaboration

Involvement and engagement |

High |

| Domino et al 2005 |

America |

1023

|

Costs related to health care and other service use at 6-month follow-up are presented for women with co-occurring mental

health and substance abuse disorders implementation |

Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence

Project (WCDV) project |

quasi-experimental |

Treatment as usual |

There are no significant differences in total costs between participants in the intervention condition and those in the usual care comparison condition, either from a governmental (avg. $13,500) or Medicaid reimbursement

perspectives (avg. just over $10,000). But better outcomes were derived. |

Finance |

High |

| Morrissey et al 2005 |

America |

2,005 |

Women with mental health and substance use disorders

who have experienced physical or sexual abuse who enrolled in either comprehensive, integrated, trauma-informed, and consumer/

survivor/recovering person-involved services |

Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence

Project (WCDV) project |

quasi-experimental |

Treatment as usual |

Insites where the intervention condition provided more integrated counseling than the comparison condition, there are increased effects on mental health and substance use outcomes; these effects are partially mediated by person-level variables. |

Cross sector collaboration

Involvement and engagement

Trauma specific treatments |

Hight |

| Chung et al 2009 |

America |

2,087 |

An intervention targeted to

provide trauma-informed integrated services in the treatment of co-occurring disorders has changed the content of services reported by clients. |

Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence

Project (WCDV) |

Quasi-experimental |

Treatment as usual |

We found strong evidence that the intervention increased the provision of trauma-informed and integrated services as well as services addressing mental health or substance use problems in several service types within the scope of the WCDVS |

Cross-interagency collaboration |

High |

| Drabble 2013 |

America |

12 |

Implementing trauma-informed system change in the family drug courts |

Harris & Fallot |

Qualitative |

NA |

Results underscore the relevance of trauma-informed systems change in collaborative contexts designed to address the complex needs of children and families |

Leadership

Cross sector collaboration

Physical environment

Workforce development |

High |

| Kirst et al 2017 |

Canada |

19 |

To explore facilitators and barriers in implementing trauma-informed practices and delivering trauma-specific services in mental health and addiction service settings |

NA |

Qualitative |

NA |

Key facilitators included: organizational support, community partnerships, staff awareness of trauma, a safe environment, peer support, the quality of consumer-provider relationships, consumer and provider readiness to change, and staff supports. Challenges included: provider reluctance to address trauma, lack of accessible services, limited funding for programs/services, and staff burnout. |

Leadership

Financing

Cross sector collaboration

Physical environment

Workforce development

Involvement and engagement |

High |

| Hales et al 2017 |

America |

|

Examined the impact of implementing TIC on the satisfaction of agency staff |

Harris & Fallot |

Pre-post |

NA |

TIC implementation is associated with increased staff satisfaction, and may positively influence organizational characteristics of significance to social service agencies. |

Workforce development

Policy

Trauma specific therapies

Leadership/management |

Low |

| Tompkins & Neale 2016 |

United Kingdom |

37 |

The delivery of trauma-informed residential treatment, focusing on factors that affect how it is provided by staff and received by clients, particularly the challenges encountered. |

Harris & Fallot |

Qualitative |

NA |

Trauma-informed treatment delivery was affected by: ‘recruiting and retaining a stable and trained staff team’; ‘developing therapeutic relationships and working with clients’; and ‘creating and maintaining a safe and stable residential treatment environment’. Clients’ complex needs and programme intensity made trauma-informed working demanding for staff to deliver and for clients to receive. Staff working in the residential service needed sufficient training, support, and supervision to work with clients and keep themselves safe. Clients required safety and stability to build trusting relationships with staff and engage with the treatment. |

Workforce development

Trauma specific treatments

Physical environment |

High |

| Hales et al 2019 |

America |

62 |

To operationalize the processes, an agency can take to become trauma informed and assesses the impact of a multiyear TIC implementation project on organizational climate, procedures, staff and resident satisfaction, and client retention in treatment |

Organisational system wide Training & Consultation |

Longitudinal quantitative |

NA |

Following TIC implementation, there were positive changes in each of the five outcomes assessed. Workplace satisfaction, climate, and procedures improved by moderate to large effect sizes, while client satisfaction and the number of planned discharges

improved significantly. |

Training. Mentors

Policy

Physical environment

Workforce development/self care/supervision

Involvement/engagement |

Low |

| Rutman & Hubberstey 2020 |

America |

60 |

What difference is HerWay Home making for service partners, e.g., in terms of knowledge gained, shifts in practice, including in collaborative practice |

HerWay Home |

Mixed methods service evaluation |

NA |

Cross-sectoral service collaborations and outcomes for service partners as well as for women and families, including prevention of children going into care. |

Cultural

Finances

Involvement engagement for evaluation

Cross-sector collaboration |

Low |

Zoorob et al 2022

Edwards et al 2023

|

America

America |

180

58 |

Cultural and gender responsive trauma informed substance use program evaluation

The purpose of the proposed

evaluation of the Support, Education, Empowerment, and Directions (SEED Domestic and sexual violence (DSV) and substance use disorders (SUDs) |

The Women’s Access Project for Houston (WAPH)

Support,

Education, Empowerment, and Directions [SEEDs |

Evaluation pre-post

Longitudinal Evaluation |

NA |

Statistically significant decreases in alcohol-binge drinking, illegal drug use, and same-day alcohol and drug use were observed when comparing the baseline and 6-month follow-up.

interviews. Participants reported improvement in psychosocial functioning, substance use

Results suggest that SEEDs participants improved over time for primary (i.e., victimization,

perpetration, and substance use) and other (i.e., posttraumatic stress, depressive symptoms, financial worries, and housing instability) outcomes. Sense of purpose, posttraumatic growth, and personal empowerment did not change over time. Length of stay and program involvement in SEEDs were the most consistent predictors of improvements at the 12-month follow-up |

Evaluation

Evaluation |

Low

Moderate |

| Jirikowic et al 2023 |

America |

246 |

We present the Trauma Informed Parenting

(TIP) intervention model for mothers parenting young children while in residential SUD treatment |

Trauma Informed Parenting |

Quantitative |

NA |

The TIP intervention aimed to identify child development and parenting

needs in order to promote co-regulation and responsive parenting within the context of daily routines and activities, within the new or less-familiar treatment center environment. |

Workforce development Screening

Measurement/monitoring

Physical environment |

High |

| Sternberger et al 2023 |

America |

594 |

Describe the design and implementation of a multidisciplinary, integrated approach to perinatal care,

supporting pregnant, postpartum, and parenting people (PPPP) and their families affected by substance use disorders (SUD). |

The Moms Do Care (MDC) Program |

Evaluation quantitative |

NA |

By enhancing the capacity of medical and behavioral health providers offering integrated care across the perinatal health care continuum, MDC created a network of support for PPPP with SUD. Lessons learned include the need to continually invest in staff training to foster teambuilding and improve integrated service delivery, uplift the peer recovery coach role within the care team, improve engagement with and access to services for communities of color, and conduct evaluation and sustainability planning. |

Leadership

Workforce development

Cross system collaboration/referral paths

Peer support/involvement

Policy change

Finances

Use of data/monitoring

Evaluating |

Low |

| Mefodeva et al 2023 |

Australia |

38 |

We examined client and staff perceptions of the relationship between trauma and SUDs, and the integration of trauma-informed care (TIC) and specialist-delivered treatment for PTSD in residential alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment facilities. |

NA |

Qualitative |

|

Both clients and staff perceive comorbid SUD/PTSD as a challenge in residential treatment, that may be overcome through integrating TIC and PTSD treatment in residential treatment facilitates for substance use. |

Workforce development

Inter-agency collaboration for referral

Screening

Use of measures/monitoring |

High |

3.0. Results

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

3.1. Quality Appraisal

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018) was used to assess the quality of the included studies

Table 4. The protocol has five questions in each of the four methods sections. To communicate the appraisal a categorical approach was used with 20-40% indicating low quality; 60% indicating moderate quality, and 80-100% indicates high quality. Four studies used the same dataset from the Women Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Project (WCDV); therefore, appraisal is reported on just one for these studies. Overall, the quality of studies was low in (n=5), high in (n=6), and moderate in (n=1).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

There are (N=15) studies included reporting on (n=12) datasets, date range 2005-2023. Most research was conducted in America (n=9), Australia (n=1), Canada (n=1), and the United Kingdom (n=1), with (n=9) different models of trauma informed care. Qualitative methods were used in (n=4), mixed methods (n=1), and quantitative (n=9), of which (n=3) are evaluations, (n=3) longitudinal (n=2) and quasi-experiential (n=1). After removing three of the four studies reporting on the same dataset, the total sample size is (N=3,721). Two thirds of the sample come from this dataset (Chung et al., 2009; Domino et al., 2005; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Morrissey et al., 2005). The implementation domains highlighted in each study ranged from 1-8, see table 4.

3.3.1. Service User Benefits

The evidence for trauma informed care implementation on service user outcomes is rather limited and of mixed quality. Several studies reported on reductions in substance use . Pre-post baseline data using a battery of substance use and mental health questionnaires after controlling for person level and program level covariates found integrated trauma informed care to be more beneficial for substance use and mental health difficulties (Morrissey et al., 2005). Similarly, Edwards et al. (2023) found that the SEEDs trauma informed care model had a range of outcomes from baseline to 12 month follow up across, victimization, perpetration, and substance use) and other outcomes such as posttraumatic stress, depressive symptoms, financial worries, and housing insecurity ). In their integrated trauma informed care evaluation, Zoorob et al. (2022) demonstrate outcomes from baseline to 6 months in decreases in alcohol-binge drinking, and improvement in psychosocial functioning, substance use, and self-sufficiency. Hales et al. (2019) highlight that a multiyear trauma informed implementation in a residential setting was associated with more planned discharges, indicating lower levels of attrition. This is an important outcome when viewed in the context of Edwards et al. (2023) who found that 12 month follow up outcomes were predicted by length of stay.

Trauma informed integrated care was further correlated with service user satisfaction (Hales et al., 2019), and it is plausible that satisfaction mediates treatment retention as 40% more service users completed discharge satisfaction surveys on the second assessment relative to the first. However, the non-randomisation does mean that these studies need to be interpretated with caution.

3.3.2. Parent and Child Benefits

Outcomes were reported for children and parents in residential and justice settings (Drabble, 2013; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Rutman and Hubberstey 2020). Jirikowic et al. (2023) note the benefits of Trauma Informed Parenting in a residential setting for helping parents co-regulate with their child during routine day to day living and activities. Rutman and Hubberstey (2020) describe how the HerWay Home program may act as a protective factor against children going into care based on the collaborative relationships built up between program staff and social workers. Drabble et al (2013) reports on findings from a qualitative four year implementation study in the family drug courts, noting that parents are better supported and feel safer to open up and engage with support structures, while practitioners have an increased understanding of the impact of trauma on families making them more empathic. Again, the small sample sizes, qualitative research, and non-randomisation in quantitative studies means findings could be explained by other factors.

3.3.3. Employee Benefits

The implementation of trauma informed care is associated with employee satisfaction (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2017; Hales et al., 2019). Employee satisfaction may in part be due to the cultivation of organisational climate, whereby employees experience the organisational climate as more positive after implementation (Hales et al., 2019). Drabble et al. (2013) describes how participants in their qualitative study explained how using a trauma informed approach directly impact service user outcomes positively, which in turn impacted their job satisfaction. In addition, employees become more comfortable in having trauma discussions with clients and feel more competent to do so (Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005).

3.4. Implementation Domains

3.4.1. Leadership

Leadership is an essential component of trauma informed implementation. Leadership was described as an implementation domain in (Drabble, 2013; Hales et al., 2017; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023). Leaders can act as champions for trauma informed care implementation (Kirst et al., 2017). Drabble et al. (2013) describes how during the implementation process in family drug courts that it was essential to have trauma informed leadership from judges referred to as ‘bench leadership’. The leadership team can plan, design, make resources available, and help embed a culture of continuous improvement (Sternberger et al., 2023). Where this type of positive leadership style is experienced by employees, they feel more cared for, and develop better relationships with management (Hales et al., 2017).

3.4.2. Workforce Development

Workforce development consists of all developmental activities undertake from planning to implementation, as well as continuous ongoing training and self-care provided to employees. (Drabble et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2017; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Hales et al., 2019; Hales et al., 2017; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Sternberger et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). It includes training the entire workforce form front of house, to clinicians in universal principles of trauma informed care (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2019; Hales et al., 2017; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Kirst et al., 2017). The training and support structures for peer support/recovery coaches was identified as important (Drabble et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023; Zoorob et al., 2022). Concern about employee health was discussed with vicarious trauma and occupational stress as risk factors (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2019). Support structures such as reflective supervision are described as essential (Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). Sternberger et al. (2023) conclude their study by identifying the need to continuously invest in employee development.

3.4.3. Screening, Assessment & Treatment

While trauma informed care is applied as an organisational intervention, some organisations may not implement screening, assessment, or specific trauma focused treatments. However, screening can be the first step taken to recognise trauma responses in service users.

Screening was implemented through the asking of questions or using questionnaires (Mefodeva et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016), or screening parents and children in residential treatment (Jirikowic et al., 2023). How comprehensive assessments were conducted is absent from this review. However, trauma focused treatments such as Seeking Safety were discussed in (Hales et al., 2017; Chung et al., 2009; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Zoorob et al., 2022), and trauma focused psychotherapies in (Mefodeva et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016), while psychoeducation was also provided (Mefodeva et al., 2023). It was highlighted that underpinning treatment approaches is the need to establish a strong therapeutic relationship to inform the work (Kirst et al., 2017; Tompkins and Neale, 2016).

3.4.4. Cross-Sectoral Collaboration

Cross sectoral/inter-agency collaboration is an important implementation domain discussed in seven studies (Chung et al, 2009; Drabble et al., 2013; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Kirst et al., 2017; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Sternberger et al., 2023). Collaboration operates on several levels with the aim of building capacity for trauma informed implementation (Drabble et al., 2013; Finkelstein and Markoff 2005; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023). Where trauma informed collaborations exist, referrals can be made (Mefodeva et al., 2023), and outcomes in mental health, substance use and psychosocial domains may be improved (Chung et al., 2009; Rutman and Hubberstey 2020). Rutman and Hubberstey (2020) found that the relationships employees developed through cross-sectoral work with other organisations were integral to their inter-agency collaboration and meeting the needs of service users. These findings are reinforced in the context of the Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Project (WCDV), where collaboration was identified as essential for the provision of trauma-informed and integrated services (Chung et al., 2009; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Morrisey et al., 2005;. Finkelstein and Markoff (2005) report using an Integrated Care Facilitator to achieve these aims.

3.4.5. Service User Involvement/Engagement

Involvement and engagement of those with lived experience can help escalate implementation and make it more relevant to the needs of the populations served.

Engagement and involvement were discussed in seven studies (Drabble et al., 2013; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Hales et al., 2019; Kirst et al., 2017; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Sternberger et al., 2023). Those with lived experience can be engaged early on during the planning stage, and become part of committees and steering groups (Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005); they can be engaged to deliver service as peer support/recovery coaches (Drabble et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023; Zoorob et al., 2022), and those with lived experience should be included in the evaluation process, helping to shape questions and objectives (Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020). Training is needed for both service users and providers to engage in this type of integration (Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005).

3.4.6. Physical Environment

The physical environment in which trauma informed care is delivered needs to be well thought out as it can enhance feelings of safety (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2019; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Kirst et al., 2017; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). When service users feel safe, only then can they undertake the difficult work they may need to engage in. After implementing trauma informed care, employee pre-post scores on physical safety were of a moderate effect size (Hales et al., 2019). The physical environment was described in studies as contributing to a felt sense of physical safety, and as such, the space that service users are located in needs to be calm and conducive to engaging people (Kirst et al., 2017; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). Very often services find it difficult to achieve this safe physical environment. For example, Drabble et al. (2013) highlight how in the court system domestic abuse survivors found the environment triggering and frightening, in addition to a lack of physical space for confidential conversations with professionals.

3.4.7. Progress Monitoring & Evaluations

Progress monitoring and evaluation are two important domains and can be achieved using various methods such as the establishment of key performance metrics at the planning stage, (Sternberger et al., 2023) or service user and employee satisfaction with services (Hales et al., 2019). However, there was scant reference to monitoring outcomes for service users, or the process of care (therapeutic alliance), which is one of the strongest predictors of outcomes. Evaluation can be thought of as the final domain to close the feedback loop.

In this review, four studies conducted evaluations of trauma informed organisations (Edwards et al., 2023; Hales et al., 2019; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Zoorob et al., 2022). Stakeholders such as employees and service users should help shape the evaluation process.

3.4.8. Financing Implementation

The type of health system and socioeconomic factors may impact upon how an organisation is resourced, as such, planning how the initial, and ongoing implementation will be financed is integral (Domino et al., 2005; Kirst et al., 2017; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Sternberger et al., 2023). The most comprehensive study of trauma informed care implementation to date, using the most advanced research methods (in this review) has demonstrated that there was no difference in the cost of implementing trauma informed care when compared to treatment as usual (Chung et al., 2009; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Morrisey et al., 2005). While Rutman and Hubberstey (2020) included a return-on-investment analysis in their evaluation, finding that for every dollar invested by HerWay Home, it created a social value of approximately $4.45.

3.4.9. Policy Development

Developing policy towards a more trauma informed culture needs to be considered as it can provide guidelines and a framework for practice (Hales et al., 2019; Hales et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023). Policy should be examined early on and can be planned for by assessing the organisations administration functions and documentation (Hales et al., 2017). Using external consultants to help assess an organisations readiness for implementation can be considered, and evaluation of policy can be carried out as part of this assessment (Hales et al., 2019). Policy should be assessed across all facets of the organisation from practice and implementation to human resources. Sternberger et al. (2023) note how organisational policy can act as a barrier to hiring people with lived experience as peer recovery coaches, and therefore flexibility in how policy is developed and applied may need to be examined.

4.0. Discussion

This systematic review of trauma informed care with implementation domains in substance use settings included (N=15) studies of varying quality; low in (n=5), moderate in (n=1) and high in (n=6). Many of the studies reported positive findings of effectiveness and implementation in different treatment contexts. For example, community-based services and residential services report on positive outcomes across mental health, substance use, treatment retention, parenting capacity and outcomes for children. However there were no experiential studies in this review, meaning drawing casual inferences cannot be made. Rather we can speak only of correlations.

Of note, one study used a quasi-experiential methodology with comparison groups and had, by far, the largest sample, and therefore deserves special attention. The Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Project (WCDV) remains the single example of large-scale implementation of trauma informed systems demonstrating multiple outcomes (Chung et al., 2009; Domino et al., 2005; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Morrissey et al., 2005). However, while there were nine sites in the study, only five of these sites as a group had positive effects on mental health status and substance use. These five sites were those in which women’s experiences of integrated counselling were greater in the intervention condition than in the usual care condition.

While the study controlled for baseline severity, and personal and programme level variables, the non-randomised nature of the methodology means that it is possible that selection bias masked other variables such as therapist effectiveness, or the effectiveness of clinic in which they were attending. Prior research demonstrated that the difference between therapists and clinics is quite large, even after controlling for variables such as diagnosis, and level of severity at baseline. Thus, it could be that this cohort of individuals were attending more effective practitioners or sites (Mahon et al., 2023). Another plausible explanation for these findings is that the intervention group with the greater experiences of integrated counselling received a greater dose of treatment. This explanation would align with prior research on the dose effects, that is, the more treatment as person receives, the more symptom reduction they will experience (Robinson et al., 2020).

Implementation is not without difficulty, however, the findings from this review provide some evidence that the 10 implementation domains can support the uptake and cultural shift that is needed to move towards a more responsive trauma system. The findings in this review suggest that leadership can play an integral role in planning, championing and resourcing implementation strategies (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2017; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023), which should include involvement from service users (Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005); who can be engaged to deliver services as peer support/recovery coaches (Drabble et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023; Zoorob et al., 2022). Prior research on facilitators and barriers to implementation note how important the role of senior leadership is for engaging in and driving the implementation process (Huo et al., 2023).

Leadership is essential for resourcing training and workforce development which has been highlighted as across studies various studies in this review (Drabble et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2017; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Hales et al., 2019; Hales et al., 2017; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Sternberger et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). A recent systematic review by Purtle et al. (2020) suggests that trauma informed care training in organisations can help employees to become more knowledgeable and competent, highlighting that initial, refresher and ongoing training should be considered as part of implementation.

Several studies noted how employee occupational stress is a concern for trauma informed organisations (Drabble et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2019). Leaders who adapt a trauma informed leadership style can help mitigate organisational stress through enhanced relationships with employees, who also feel more supported (Hales et al., 2017; Hale et al., 2019). However, there is little by way of instruction on the range of behaviours exhibited by such leaders, Mahon (2022) developed a trauma informed servant leadership style of leadership arguing that its very philosophy (service to others and developing employees) is congruent with the values of trauma informed care. A recent systematic review also demonstrated that servant leadership is predictive of burnout (Mahon, 2024), and that this was mediated by psychological safety. The studies included here speak to the importance of safety, both physical and emotional for employees, therefore, servant leadership may be the ideal leadership approach to adapt in trauma informed organisations.

Similarly, previous research conducted by Grunhaus et al. (2023) demonstrated that a servant leadership model of clinical supervision reduced burnout and secondary trauma in mental health practitioners, all important workforce development areas to consider. Indeed, in this review, supervision was described as helping to develop reflective practice and self-care strategies (Kirst et al., 2017; Sternberger et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). Organisations should consider how they can make their supervision and treatment more culturally responsive, and to this end, the evidence suggests that multicultural orientation during treatment and supervision can be helpful when working with those of diverse ethnic and racial demographics (Mahon, 2024). Prior research demonstrates that in the absence of multi-cultural responsiveness service user outcomes can be greatly diminished (Davis et al., 2018).

There was only limited information available on screening in this review (Mefodeva et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). Screening is often an area of contention and some employees don’t feel prepared to deliver this intervention, or fear re- traumatisation during the process. However, identifying trauma is an important component of trauma informed care, as such, organisations should implement screening, and provide training to employees for asking service users questions about trauma (Ferentz, 2018; Read et al., 2007). Where trauma is identified, a more comprehensive trauma informed assessment should be conducted (Sweeney, 2021), and for trauma specific services using evidence based interventions to be provided (Hales et al., 2017; Chung et al., 2009; Jirikowic et al., 2023; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Tompkins and Neale, 2016; Zoorob et al., 2022).

Cross-sectoral and interagency work is integral. For example, where a service is not in a position to offer trauma specific interventions, or where another psychosocial need is present, then external partners become essential. The studies in this review underscore the importance of such integrated services, and the evidence points to the benefits of helping service users access timely and needed interventions to improve outcomes in substance use, mental health, parenting, and service satisfaction (Chung et al., 2009; Hales et al., 2017; Rutman and Hubberstey 2020).

Leadership should actively seek out and cultivate cross-sectoral relationships as the studies in this review speak to its importance as an added resource for referrals and inter-agency collaboration to meet service user needs (Chung et al, 2009; Drabble, 2013; Finkelstein and Markoff, 2005; Kirst et al., 2017; Mefodeva et al., 2023; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Sternberger et al., 2023). Prior research by Oral et al. (2020) highlights how cross-sectoral collaboration underpins trauma informed care implementation at the state level.

Where trauma therapies are offered there is a host of interventions found to be effective. What may be more important, and discussed in this review, is the therapeutic alliance (Kirst et al., 2017; Tompkins and Neale, 2016). Previous research on the therapeutic alliance with adults, young people and their carers using samples of 160,000 (30,000 substance use), demonstrated that when ruptures in the therapeutic alliance occur and they are not repaired, then outcomes are up to 50% worse (Mahon et al., 2023a; Mahon et al., 2024). This underscores the importance of monitoring both the alliance and outcome of care routinely for quality assurance purposes. However, in this review, there was scant information on how this domain was operationalised.

Feedback systems that utilise alliance and outcome questionnaires should be considered based on strong psychometric properties (Mahon et al., 2023a ; Mahon et al., 2023b). Feedback informed treatment serves a dual purpose of activating the monitoring/quality assurance domain, while also providing evidence based strategies to improve care, reduce attrition, and provide service users with a platform to provide feedback in order to adapt the treatment approach in real time to meet needs and preferences (Bovendeerd et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2021;de Jong et al., 2021; Delgadillo et al., 2017). At the organisational system level, monitoring and quality assurance can be maintained through the use of various measures and questionnaires to maintain fidelity to the process. Indeed, previous research by Bryson et al. (2017) found that the use of such data can act as a facilitator to implementation by motivating employees. How data can be used should be decided during the planning and baseline assessment stage of implementation (Hales et al., 2017; Hales et al., 2019; SAMSHA, 2014).

Evaluation is another important implementation domain, and in this review four studies used external evaluators to assess organisations (Edwards et al., 2023; Hales et al., 2019; Rutman and Hubberstey, 2020; Zoorob et al., 2022).

However, in their study, Sternberger et al. (2023) note how intrusive it was administering a battery of measures to an already marginalised and historically traumatised group, with a potential to re-traumatise and therefore, had the programme employees administer them as part of routine care. If services are using feedback systems such as those highlighted previously, then external evaluations can utilise this dataset as these systems offer data driven algorithms in addition to treatment effectiveness presented as a Cohens d standardised effect size (Brown et al., 2015; de Jong et al., 2021; Delgadillo et al., 2017).

Financing and policy development can play key roles in the implementation and cultural shift needed to embrace trauma informed care at the system level. Prior systematic reviews have described the importance of both areas which can act as barriers and facilitators to implementation (Hou et al. , 2023; Lewis et al., 2023; Orla et al., 2020).

4.1. Implications for Practice

For organisations planning to implement system wide trauma informed care, the following recommendation can be considered. Leadership needs to drive the process and champion the uptake of new ways of working, while also making the resources available for initial and ongoing training. A steering group made up of key stakeholders, inclusive of service users can direct and govern the process, which should begin with an initial baseline assessment of the organisations current situation. Employees should be trained in the application of trauma informed care as a universal approach, but also where relevant, in screening, assessment and trauma specific treatments. Interventions should be culturally and gender responsive, and peer supporters incorporated into the system approach. A physically and emotionally safe environment is integral for this work to occur, and the leadership and supervision approach should engender these principles, with servant leadership a viable model to embrace.

Likewise, leaders will need to develop relationships with other organisations and disciplines to help meet the needs of service users through cross-sectoral collaboration. Implementation and service user outcomes should be monitored with the use of different measurement questionnaires based on sound psychometric properties, while well planned and thought out evaluations can help further the evidence base and implementation process, and provide evidence for commissioning bodies.

4.2. Limitations & Further Research

While some important findings are presented in this systematic review, it is not without limitations. Firstly, it is recommended that evidence syntheses be conducted by at least two people, and this did not occur. However, potential bias was reduced through the setting of a priori design, research questions, inclusion criteria, and extraction methods by following protocols. In addition, it is possible that the search strategy missed relevant studies as grey literature was not included, and it is becoming more prevalent for evaluation reports to be conducted in organisations without publication. Moreover, although half the studies were rated as high quality, these were mostly qualitative studies. The remaining studies were quantitative descriptive and one quasi-experiential study. As such, drawing inferences about causality is not possible.

The lack of replication studies in this area may speak to how difficult it is to use advanced research methods on whole systems with various moving parts across an ecology (Bloom, 2010; Mahon, 2022). Trauma informed care as an integrated care service delivery model has many moving parts, and experiential research is extremely difficult to conduct as it is difficult to maintain internal validity or isolate variables across an organisation. Case in point is illustrated by drawing on the previous mentioned study, The Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Project (WCDV) where organisations delivered different types of interventions termed trauma informed and as such isolating specific ingredients was not possible.

Conducting research on systems with various dynamic parts is a complex endeavour, and experiential research such as the randomised control trial can be a prohibitive methodology in such naturalistic settings. Not least because identifying relevant covariates and their impact is not always straight forward. Future research must take this into account by controlling for service user variables such as diagnosis, baseline level of severity, and socioeconomic status. Similarly, program level variables need to be controlled for, including the intervention delivered, the practitioners prior effectiveness, and the effectiveness of the organisation where service users are attending. Other research methodologies will also be of use.

Well-designed prospective longitudinal research with multiple data collection points and time series studies are needed. Additionally, other methods may be effective for exploring the overall implementation across systems, for instance; case study designs, action research to find workarounds in real time, or qualitative approaches to capture employee and service user experiences of the process.

5.0. Conclusion

This systematic review of trauma informed care with implementation domains in substance use settings included (N=15) studies, and had positive benefits across for service users and employees. However, there was no experiential research and therefore causality cannot be ascertained. While trauma informed care as a system wide integrated care model may have benefits across service, employee and service user outcomes, the current evidence base is far from an empirical reality, Notwithstanding the evidence to practice gaps, organisations seeking to implement trauma informed care across the whole system will find it helpful to use an implementation framework, and the domains in this review seem to be relevant and effective for this purpose.

References

- Amaro, H., Chernoff, M., Brown, V., Arévalo, S., & Gatz, M. (2007). Does integrated trauma-informed substance abuse treatment increase treatment retention? Journal of Community Psychology, 35(7), 845–862. [CrossRef]

- Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M., & Skouteris, H. (2021). Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(3), 381–397. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C., Klas, A., Cox, R., Bergmeier, H., Avery, J., & Skouteris, H. (2019). Systematic review of organisation-wide, trauma-informed care models in out-of-home care (OoHC) settings. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(3), e10–e22. [CrossRef]

- Bates, G and Jones, Lisa Cochrane, Madeleine and Pendlebury, Marissa and Sumnall, Harry (2017). The effectiveness of interventions related to the use of illicit drugs: prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery. A ‘review of reviews’. Dublin: Health Research Board. HRB Drug and Alcohol Evidence Review 5.

- Benish, S. G., Imel, Z. E., & Wampold, B. E. (2008). The relative efficacy of bona fide psychotherapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Clinical psychology review, 28(5), 746–758. [CrossRef]

- Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered Approaches to Trauma-Informed Care in Schools: A Systematic Review. School Mental Health, 11(4), 650–664. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S. L. (2017). The sanctuary model: Through the lens of moral safety. In S. N. Gold (Ed.), APA handbook of trauma psychology: Trauma practice (pp. 499–513). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Bonin, M. F., Norton, G. R., Asmundson, G. J., Dicurzio, S., & Pidlubney, S. (2000). Drinking away the hurt: the nature and prevalence of PTSD in substance abuse patients attending a community-based treatment program. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 31(1), 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Bovendeerd, B., De Jong, K., De Groot, E., Moerbeek, M., & De Keijser, J. (2022). Enhancing the effect of psychotherapy through systematic client feedback in outpatient mental healthcare: A cluster randomized trial. Psychotherapy research : journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 32(6), 710–722. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., Ashworth, H., Bass, M., Rittenberg, E., Levy-Carrick, N., Grossman, S., Lewis-O’Connor, A., & Stoklosa, H. (2022). Trauma-informed Care Interventions in Emergency Medicine: A Systematic Review. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health, 23(3), 334–344. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. S. J., Cazauvieilh, C., & Simon, A. (2021). Clinician engagement in feedback informed care and patient outcomes. http://www.societyfor psych other apy. org/clini cian-engagement -in-feedback-informed-care-and-patient-outcomes.

- Brown, G. S., Simon, A. E., Cameron, J., & Minami, T. (2015). A collaborative outcome resource network (ACORN): Tools for increasing the value of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 412–421. [CrossRef]

- Bryson, S. A., Gauvin, E., Jamieson, A., Rathgeber, M., Faulkner-Gibson, L., Bell, S., Davidson, J., Russel, J., & Burke, S. (2017). What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S., Domino, M. E., & Morrissey, J. P. (2009). Changes in Treatment Content of Services During Trauma-informed Integrated Services for Women with Co-occurring Disorders. Community Mental Health Journal, 45(5), 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Devries, K. M., Child, J. C., Bacchus, L. J., Mak, J., Falder, G., Graham, K., Watts, C., & Heise, L. (2014). Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 109(3), 379–391. [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, J., Overend, K., Lucock, M., Groom, M., Kirby, N., McMillan, D., Gilbody, S., Lutz, W., Rubel, J. A., & de Jong, K. (2017). Improving the efficiency of psychological treatment using outcome feedback technology. Behaviour research and therapy, 99, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Domino, M., Morrissey, J. P., Nadlicki-Patterson, T., & Chung, S. (2005). Service costs for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2), 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Driessen, M., Schulte, S., Luedecke, C., Schaefer, I., Sutmann, F., Ohlmeier, M., Kemper, U., Koesters, G., Chodzinski, C., Schneider, U., Broese, T., Dette, C., Havemann-Reinecke, U., & TRAUMAB-Study Group (2008). Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: a multi-center study. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 32(3), 481–488. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K. M., Wheeler, L., Siller, L., Murphy, S. B., Ullman, S. E., Harvey, R., Palmer, K., Lee, K., & Marshall, J. (2023). Outcomes associated with participation in a sober living home for women with histories of domestic and sexual violence victimization and substance use disorders. Traumatology, 29(2), 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, V., Gausereide-Corral, M., Valiente, C., & Sánchez-Iglesias, I. (2023). Effectiveness of trauma-informed care interventions at the organizational level: A systematic review. Psychological Services, 20(4), 849–862. [CrossRef]

- Finkeistein, N., & Markoff, L. S. (2004). The Women Embracing Life and Living (WELL) Project: Using the Relational Model to Develop Integrated Systems of Care for Women with Alcohol/Drug Use and Mental Health Disorders with Histories of Violence. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 22(3/4), 63–80.

- 23. Gielen, N Remco C. Havermans, Mignon Tekelenburg & Anita Jansen (2012) Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among patients with substance use disorder: it is higher than clinicians think it is, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3:1. [CrossRef]

- Hales, T. W., Green, S. A., Bissonette, S., Warden, A., Diebold, J., Koury, S. P., & Nochajski, T. H. (2019). Trauma-Informed Care Outcome Study. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(5), 529–539. [CrossRef]

- Hales, T. W., Nochajski, T. H., Green, S. A., Hitzel, H. K., & Woike-Ganga, E. (2017). An Association Between Implementing Trauma-Informed Care and Staff Satisfaction. Advances in Social Work, 18(1), 300–312. [CrossRef]

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (Eds.). (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Hopper, E.K., Bassuk, E.L., & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the Storm: Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness Services Settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y., Couzner, L., Windsor, T. et al. Barriers and enablers for the implementation of trauma-informed care in healthcare settings: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun 4, 49 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jericho, B., Luo, A., & Berle, D. (2022). Trauma-focused psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 145(2), 132–155. [CrossRef]

- Jirikowic, T., Graham, J. C., & Grant, T. (2023). A Trauma-Informed Parenting Intervention Model for Mothers Parenting Young Children During Residential Treatment for Substance Use Disorder. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 39(2), 156–183. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, L., Tang, Y. L., Bradley, B., Cubells, J. F., & Ressler, K. J. (2010). Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an urban civilian population. Depression and anxiety, 27(12), 1077–1086. [CrossRef]

- Kirst, M., Aery, A., Matheson, F., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2017). Provider and Consumer Perceptions of Trauma Informed Practices and Services for Substance Use and Mental Health Problems. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 15(3), 514–528. [CrossRef]

- Konkolÿ Thege, B., Horwood, L., Slater, L. et al. Relationship between interpersonal trauma exposure and addictive behaviors: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 17, 164 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kuksis, Markus MSc; Di Prospero, Cynthia MSc; Hawken, Emily R. PhD; Finch, Susan MD (2017). The correlation between trauma, PTSD, and substance abuse in a community sample seeking outpatient treatment for addiction. The Canadian Journal of Addiction 8(1):p 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.M., Back, S.E., Hartwell, K.J., Maria, M.M.-S. and Brady, K.T. (2013), A Comparison of Trauma Profiles among Individuals with Prescription Opioid, Nicotine, or Cocaine Dependence. Am J Addict, 22: 127-131. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N. V, Bierce, A., Feder, G. S., Macleod, J., Turner, K. M., Zammit, S., & Dawson, S. (2023). Trauma-Informed Approaches in Primary Healthcare and Community Mental Healthcare: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review of Organisational Change Interventions. Health & Social Care in the Community, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., & Elmore Borbon, D. L. (2017). Trauma is a public health issue. European journal of psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1375338. [CrossRef]

-

Mahon, D. (2022a), Trauma-Responsive Organisations: The Trauma Ecology Model, Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds.

- Mahon, D. (2022b), "A systematic scoping review of interventions delivered by peers to support the resettlement of refugees and asylum seekers", Mental Health and Social Inclusion, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 206-229. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. (2024a), "Beyond multicultural competency: a scoping review of multicultural orientation in psychotherapy and clinical supervision", Mental Health and Social Inclusion, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D., Minami, T., & Brown, (G. S.) J. (2024b). The psychometric properties and treatment outcomes associated with two measures of youth therapeutic alliance using naturalistic data. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 00, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D., Minami, T., & Brown, (G. S.). J. (2023a). The variability of client, therapist and clinic in psychotherapy outcomes: A three-level hierarchical model. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 23, 761–769. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D., Minami, T., & Brown, G. S. J. (2023b). The psychometric properties and treatment outcomes associated with two measures of the adult therapeutic alliance using naturalistic data. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 00, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. (2024). A systematic review of servant leadership and burnout. , Mental Health and Social Inclusion. [CrossRef]

- Markoff, L. S., Finkelstein, N., Kammerer, N., Kreiner, P., & Prost, C. A. (2005). Relational systems change: implementing a model of change in integrating services for women with substance abuse and mental health disorders and histories of trauma. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 32(2), 227–240.

- McGovern, R., Addison, M. T., Newham, J. J., Hickman, M., & Kaner, E. F. S. (2017). Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for reducing parental substance misuse. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD012823. [CrossRef]

- Mefodeva, V., Carlyle, M., Walter, Z., & Hides, L. (2023). Client and staff perceptions of the integration of trauma informed care and specialist posttraumatic stress disorder treatment in residential treatment facilities for substance use: A qualitative study. Drug and alcohol review, 42(1), 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Oral, R., Coohey, C., Zarei, K., Conrad, A., Nielsen, A., Wibbenmeyer, L., Segal, R., Wojciak, A. S., Jennissen, C., & Peek-Asa, C. (2020). Nationwide efforts for trauma-informed care implementation and workforce development in healthcare and related fields: a systematic review. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 62(6), 906. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., de Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI evidence synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. [CrossRef]

- Purtle, J. (2020). Systematic Review of Evaluations of Trauma-Informed Organizational Interventions That Include Staff Trainings. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(4), 725–740. [CrossRef]

- Read, J., Hammersley, P., & Rudegeair, T. (2007). Why, when and how to ask about childhood abuse. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Roseby, S., & Gascoigne, M. (2021). A systematic review on the impact of trauma-informed education programs on academic and academic-related functioning for students who have experienced childhood adversity. Traumatology, 27(2), 149–167. [CrossRef]

- Rutman, D., & Hubberstey, C. (2020). Cross-sectoral collaboration working with perinatal women who use substances: outcomes and lessons from HerWay Home. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 20(3), 179–193. [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M., Houston, J. E., Dorahy, M. J., & Adamson, G. (2008). Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the national comorbidity survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophrenia bulletin, 34(1), 193–199. [CrossRef]

- Shier, M. L., & Turpin, A. (2022). Trauma-Informed Organizational Dynamics and Client Outcomes in Concurrent Disorder Treatment. Research on Social Work Practice, 32(1), 92–105. [CrossRef]

- Sternberger, L., Sorensen-Alawad, A., Prescott, T., Sakai, H., Brown, K., Finkelstein, N., Salomon, A., & Schiff, D. M. (2023). Lessons Learned Serving Pregnant, Postpartum, and Parenting People with Substance Use Disorders in Massachusetts: The Moms Do Care Program. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 27, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4801. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

- Sweeney A, White S, Kelly K, Faulkner A, Papoulias S, Gillard S. Survivor-led guidelines for conducting trauma-informed psychological therapy assessments: development and modified Delphi study. Health Expect. 2022; 25: 2818-2827. [CrossRef]

- Tach, L., Morrissey, M. B., Day, E., Vescia, F., & Mihalec-Adkins, B. (2022). Experiences of Trauma-Informed Care in a Family Drug Treatment Court. Social Service Review, 96(3), 465–506. [CrossRef]

- Thielemann, J. F. B., Kasparik, B., König, J., Unterhitzenberger, J., & Rosner, R. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents. Child abuse & neglect, 134, 105899. [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, C. N. E., & Neale, J. (2018). Delivering trauma-informed treatment in a women-only residential rehabilitation service: Qualitative study. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 25(1), 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Zoorob, R., Gonzalez, S. J., Kowalchuk, A., Mosqueda, M., & MacMaster, S. (2022). Evaluation of an Evidence-Based Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program for Urban High-Risk Females. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 1–12. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

mpopulation, concept and context.

Table 1.

mpopulation, concept and context.

| |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

| Population |

Substance use organisations delivering trauma informed care to adults. |

Non trauma informed organisations. |

| Concept |

Organisational trauma informed interventions which have at least one of the 10 implementation domain as described by SAMSHA |

Trauma specific interventions only. Trauma focused therapies. Trauma intervention without implementation factors. Not defined as trauma informed. No substance use element |

| Context |

Any health and social care, mental health, criminal justice, homelessness, hospital and community settings. Any organisation in public, private or NGO. |

N/A |

Type of studies

Reported Outcomes

|

Peer reviews empirical articles, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, or service evaluations that report on a model of trauma informed care with outcomes on implementation of at least one domain.

.

Reductions in substance use, reductions in mental health diagnosis, reductions in trauma symptoms, improved functioning, improved quality of life, satisfaction with service delivery, improved service utilisation |

Scoping review, narrative review, integrated review, single studies, grey literature. studies with only service user outcomes reported without implementation considerations. Case studies with no data |

| |

| Time frame |

From inception to 2024 |

No limiters applied |

| Language |

English |

Papers in non-English |

Table 2.

Search strategy.

Table 2.

Search strategy.

Academic Search

Complete |

trauma informed care OR trauma informed practice OR trauma OR trauma informed approach AND substance abuse OR substance use OR drug abuse OR drug addiction OR drug use |

| Scopus |

( TITLE-ABS KEY ( trauma AND informed AND care OR trauma AND informed AND practice OR trauma OR trauma AND informed AND approach ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( substance AND abuse OR substance AND use OR drug AND abuse OR drug AND addiction OR drug AND use ) |

| Embase |

trauma informed care OR trauma informed practice OR trauma OR trauma informed approach AND substance abuse OR substance use OR drug abuse OR drug addiction OR drug use |

Table 4.

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool.

Table 4.

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool.

| The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool questions |

Yes |

No |

Cannot tell |

Total assessed |

| N |

|

N |

|

CT |

|

N |

% |

Screening questions

S1. Are there clear research questions? |

12 |

|

12 |

|

|

|

12 |

100 |

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

12 |

|

12 |

|

|

|

12 |

100 |

Qualitative study component

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

4 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

100 |

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

4 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

100 |

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

4 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

100 |

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

1 |

|

3 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

100 |

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? |

2 |

|

2 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

100 |

Quantitative non-randomised study component

3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? |

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

1 |

100 |

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? |

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

1 |

100 |

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? |

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

1 |

100 |

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? |

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

1 |

100 |

| 3.5 During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

1 |

100 |

Quantitative Decriptive

4.1 Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? |

5 |

|

1 |

|

0 |

|

6 |

100 |

| 4.2 Is the sample representative of the target population? |

1 |

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

6 |

100 |

| 4.3 Are the measurements appropriate? |

4 |

|

2 |

|

0 |

|

6 |

100 |

| 4.4 Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? |

2 |

|

0 |

|

4 |

|

6 |

100 |

| 4.5 Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

3 |

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

6 |

100 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).