1. Introduction

The quest for sustainable and efficient methods of freshwater production is a critical issue in many regions around the globe [

1,

2,

3,

4]. One such method, solar distillation, has garnered significant attention due to its simplicity [

5], low operational cost, and reliance on renewable energy sources [

6,

7]. Solar stills, devices that utilize solar energy to purify water through evaporation and condensation, offer a viable solution for producing potable water in areas with limited access to freshwater sources. This study focuses on estimating the productivity of single-slope solar stills in the Caspian Sea region, which includes key cities such as Aktau, Atyrau, Astrakhan, Makhachkala, Baku, Tehran, and Turkmenbashi.

The Caspian Sea region presents a unique set of climatic conditions that impact the performance of solar stills. The region encompasses diverse geographical and meteorological settings, from the arid and semi-arid climates of Aktau and Turkmenbashi to the more temperate climates of Baku and Tehran. Many of these cities experience continental climatic conditions [

8,

9], characterized by four seasons, ranging from cold winters to hot summers. Understanding how these varying conditions affect the efficiency and productivity of solar stills is crucial for optimizing their design and implementation in this region.

Previous studies on solar distillation have focused on regions with consistently high solar irradiation and ambient temperatures, such as the Middle East (North Africa) [

10], Southeast Asia [

11], the Persian Gulf [

12], and India [

13]. In a study conducted by Yousef et al. [

10], an energy and exergy analysis was performed based on a heat balance model for a single-slope passive solar still under Egyptian climatic conditions. The findings indicate that the maximum energy and exergy efficiencies of the proposed solar still are 32.5% and 2%, respectively. Additionally, the irreversibility analysis revealed that the basin liner is responsible for 86% of the total exergy destruction. Another research [

11] evaluated the efficiency of an inclined copper-stepped solar still through both theoretical and experimental approaches under Malaysian tropical climate conditions. The study reported a maximum hourly productivity of 474 mL/m²·h and 605 mL/m²·h, with daily efficiency ranging from 28.33% to 29.5% from September to December 2016. Esfe and Toghraie [

12] investigated the effect of wind velocity on the performance of passive single-slope solar stills for the Persian Gulf region of Iran using a CFD simulation tool. The results indicated that an increase in wind velocity decreases the freshwater production rate, with the maximum reduction occurring at a wind velocity of 15 m/s. Based on the wind velocity effect results, several settlements in Khuzestan Province of Iran were identified as optimal regions for deploying solar stills. Another CFD simulation study on solar stills, which considered the two-phase heat transfer effect, was conducted for the climate conditions of Delhi, India [

13]. The study developed a thermal model using Ansys Fluent software to predict solar still performance. Their simulation findings reported that the basin water temperature, condensing glass cover temperature, and freshwater productivity were validated with experimental results, showing a 12.7% difference between the simulated output and the experimental results. In Nomor et al. [

14], an experimental assessment of solar still productivity under Australian climate conditions is presented. After statistical analysis of experimental readings, the authors reported that the mean and median productivity values for the modified solar still were found to be 17% and 22% higher, respectively, than those for the conventional solar still. The modified system included additional thermal mass inside the solar still. Solar desalination offers a sustainable solution to address freshwater scarcity in arid regions. A study conducted in the central region of Saudi Arabia evaluated the performance and productivity of four solar stills using both experimental and numerical approaches [

15]. The results indicated that reducing the air gap distance and water depth significantly enhanced freshwater yield. Optimal ratios for length-to-width and back-to-front wall height were found to be 2 and 3.65, respectively. Specifically, at a low water depth of 0.5 cm, the daily distillate yield increased by approximately 11% when the air gap distance decreased from 20 cm to 14 cm. Furthermore, at the lowest air gap distance of 14 cm, the distillate yield increased by about 23% when the water depth decreased from 1.5 cm to 0.5 cm.

Despite the lower productivity of solar stills compared to reverse osmosis and multi-stage distillation technologies, significant efforts are being directed toward enhancing the efficiency of this fundamental design without relying on energy-intensive methods [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Researchers are primarily focused on modifying the geometric configuration of the distiller [

16,

17], incorporating sensible and phase change materials (PCMs) [

18,

19,

20], and integrating solar stills with other renewable energy technologies [

6,

7]. These strategies can substantially reduce energy consumption compared to reverse osmosis and decrease dependence on hydrocarbon fuels compared to multi-stage distillation. However, it is also important to explore the combination of solar distillation with existing fossil fuel-based thermal desalination technologies. This approach is particularly relevant for regions rich in inexpensive hydrocarbon resources, such as the Caspian region, where access to drinking water remains a significant challenge.

A brief review of the literature on solar still productivity reveals that most studies have been conducted in hot climatic conditions. However, with its distinct climatic variability, the Caspian Sea region has not been extensively studied in this context. This gap in the literature underscores the need for a detailed numerical analysis of solar still productivity tailored to the specific conditions of the Caspian region. This research aims to provide a comprehensive numerical estimation of solar still productivity across different cities in the Caspian Sea region. Using a mathematical model based on heat balance equations and implemented via the 4th-order Runge-Kutta method, we simulate the distillation process under various seasonal conditions. The model accounts for key parameters such as solar irradiation, ambient temperature, water depth, and insulation thickness, providing insights into the optimal design and operation of solar stills in this region. A comprehensive mathematical model and calculation algorithm are presented, including all necessary closing coefficients and validation, enabling readers to fully replicate the calculations.

By evaluating the productivity, efficiency, and cost of distilled water, this study seeks to offer practical recommendations for enhancing solar still performance. The findings will also contribute to the broader understanding of solar distillation’s potential as a sustainable freshwater production method, particularly in regions with challenging climatic conditions. Furthermore, the research explores the possibility of integrating solar stills with other renewable energy technologies and fossil fuel-based systems, aiming to improve overall efficiency and reduce the environmental impact of water desalination processes.

This paper presents a detailed numerical analysis of single-slope solar still productivity in the Caspian Sea region, providing valuable insights into the factors influencing performance and offering guidelines for optimizing design and implementation in diverse climatic conditions.

2. System Description

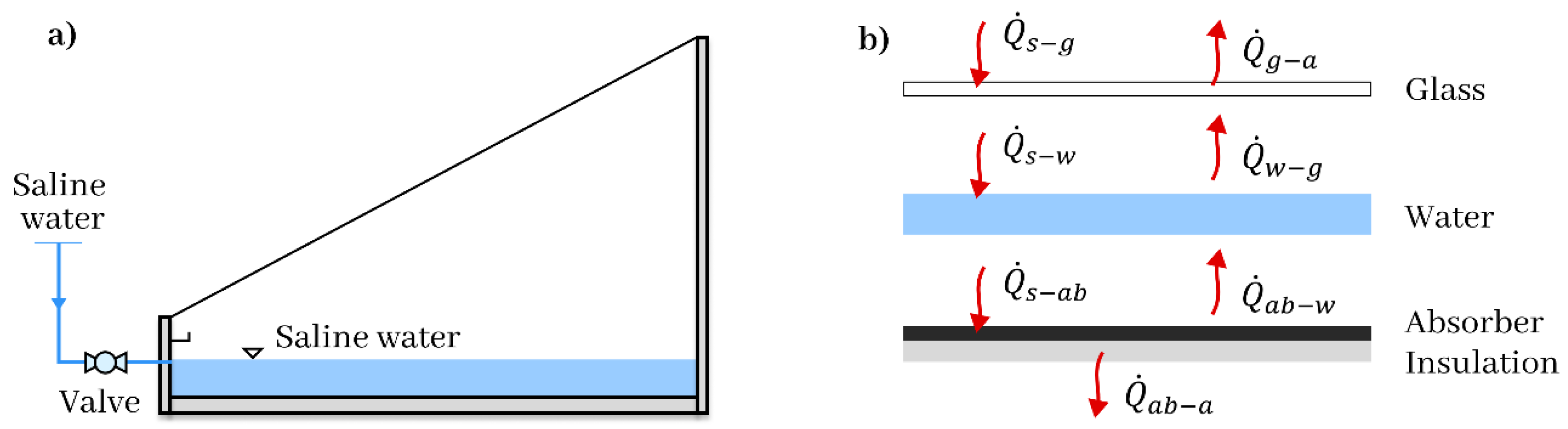

A solar still is a device that utilizes solar energy to purify water through the processes of evaporation and subsequent condensation. Its operation is based on the principle of distillation: solar energy heats the water, causing it to evaporate and leave behind impurities and salts. The resulting steam condenses on a cooler surface, typically glass, and the purified water then flows into a collection tank. The primary components of solar still include: basin - a container where the raw water, either dirty or saline, is poured; covering - usually made of transparent glass or plastic, allowing solar energy to penetrate and heat the water; condensing surface - the surface on which the steam condenses back into the water; collection tank - a container that collects the condensed, purified water. Solar stills are simple, environmentally friendly devices that can be particularly beneficial in regions with limited access to fresh water and high solar irradiation.

Figure 1a presents a conventional single-slope solar still, illustrating its main components. The absorber and basin water area are 1 m

2, while the glazed surface area is 1.15 m

2. The glass slope is adjusted to match the local conditions of the specified city.

3. Mathematical Model

3.1. Heat Balance Model

The mathematical model comprises a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on the heat balance of the solar still components. The primary heat balance equation is formulated for the glass cover, saline/brackish water, and absorber plate. The following assumptions were made in the energy performance modeling:

Water vapor leakages are neglected.

Influences due to potential, kinetic, and chemical changes are ignored.

The temperature of the saline water in the basin is assumed to be uniform.

The first law of thermodynamics is employed to derive the heat balance equations for the solar still components. According to the heat balance principle, the amount of incoming heat to a specific component of the system equals the sum of the outgoing heat and the stored heat within this component.

Figure 1b provides a schematic representation of the heat balance within the conventional solar still.

For the glass cover, the incoming heat includes solar irradiation and heat from the basin water surface, while the outgoing heat encompasses convective heat transfer to the ambient air and radiative heat transfer to the sky. The general energy balance equation for a glass cover is given by:

where

represents the fraction of the solar flux absorbed by the glass. The overall heat transfer coefficient, accounting for radiation, convection [

21], and evaporation [

22], is given by the following equation [

8,

9]:

The mentioned heat transfer coefficients are determined by the following equations:

The convective heat transfer coefficient between the glass and ambient air is determined using Equation (7):

The radiative heat transfer coefficient between the glass and ambient air is determined using Equation (8):

For saline or brackish water, the inlet heat includes solar irradiation and convective heat transfer between the absorber plate. The outlet involves heat exchange between the water and the glass. Equation (10) represents this heat balance for saline water:

where

is a fraction of the solar flux coefficient, representing the absorbance of saline water. The convective heat transfer coefficient between the water and the absorber plate is determined using Equation (11) [

23]:

For the absorber plate, the incoming heat consists of solar irradiation. The outgoing heat includes convective heat transfer between the absorber plate and water, as well as heat loss from the rear side of the absorber, considering insulation. Equation (12) describes this heat balance for the absorber plate:

where

is a fraction of the solar flux coefficient, representing the absorbency of the absorber plate. The overall heat loss coefficient is determined using Equation (13):

The convective heat transfer coefficient between the absorber plate and ambient air is determined using Equation (14):

The instantaneous productivity of the solar still is determined using the following equation [

8,

9]:

The daily accumulated productivity of the solar still is determined using the following equation [

8,

9]:

The energy efficiency of the solar still is determined using Equation (17) [

8,

9]:

Here,

represents the latent heat of water vaporization. In Equations (1)-(17), any coefficients not listed in

Table 1 have their calculation formulas provided in the Appendix.

3.2. Economic Analysis Model

The cost of distilled water is a critical parameter in determining the feasibility and applicability of a desalination device [

25,

26]. Although solar stills are less cost-effective and scalable than other desalination systems, this work evaluates its freshwater production performance in terms of cost. The solar still is considered a fundamental benchmark case for studying thermal desalination systems. The unit cost of distilled water is evaluated using Equation (18):

where

is the total annualized cost, and

is the annual yield. The

is calculated using the fixed annual cost (

), annual maintenance cost (

), annual operating cost (

), and annual salvage value (

) as follows:

where

is the capital cost of solar still,

is the capital recovery factor of the system,

– the interest rate per year,

– the lifetime of the system.

is considered to be 10 % of the .

The is considered to be zero, as the natural physical processes of evaporation and condensation in the solar still occur without any external work.

The

of a system is the estimated residual value of the system at the end of its useful life, typically calculated on an annual basis. It accounts for the remaining value of the system components after depreciation. The

can be calculated using the following formula:

Here, the salvage value (

) of the system is considered to be 20% of the

. The Sinking Fund Factor (

) is calculated using Equation (25):

Details on estimating the cost of distilled water, as determined by Equations (18)-(25), are provided below.

4. Model Validation

A mathematical model of heat balance, based on Equations (1)-(17) and incorporating all closure coefficients, was numerically implemented using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method in the Python programming language. The obtained numerical results were validated by comparing them with experimental data provided by Agrawal et al. [

27]. All geometric dimensions of the solar still, thermophysical properties of the fluid, meteorological conditions, and initial input conditions were adapted based on the parameters outlined in Agrawal et al. [

27].

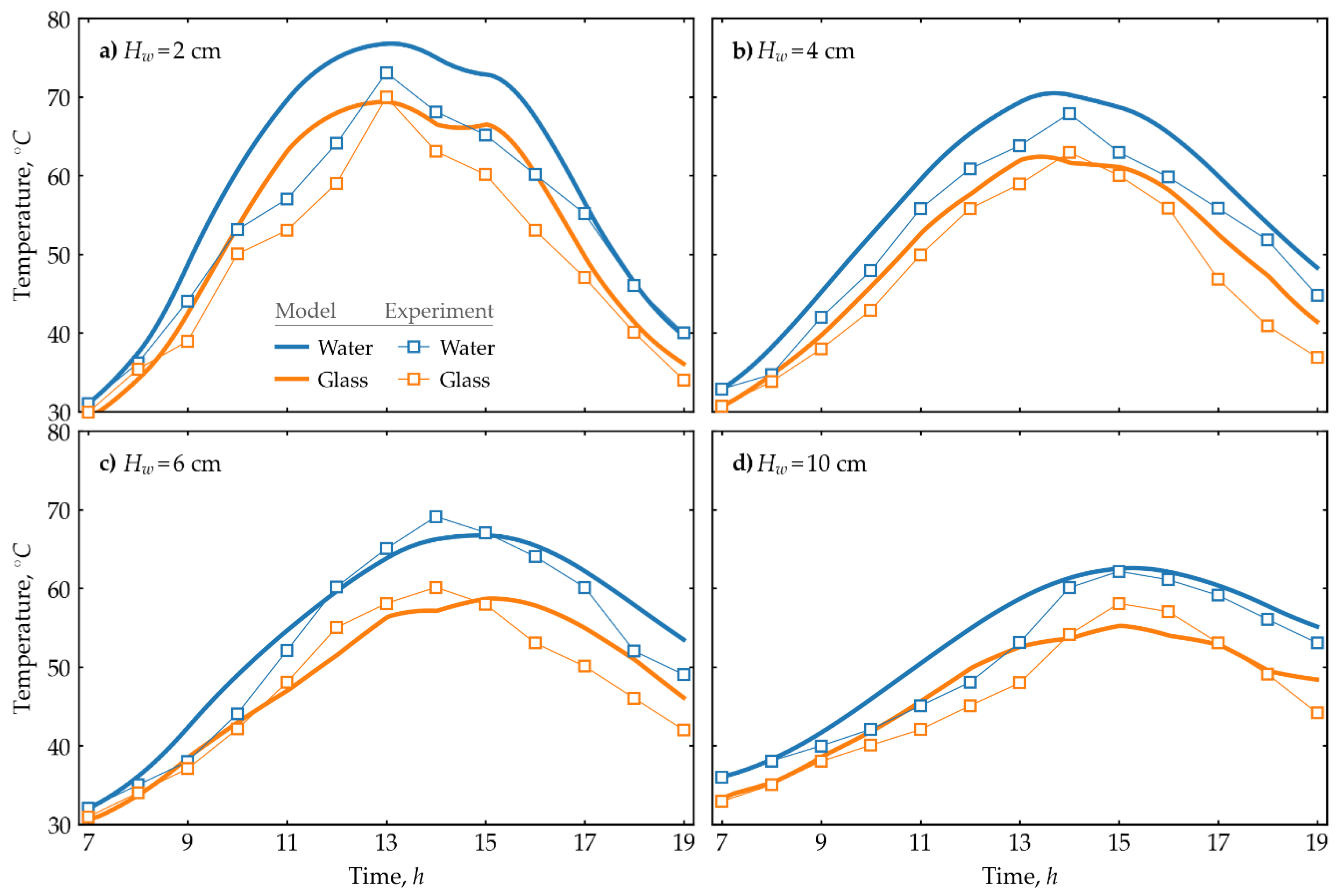

Figure 2 presents a comparative analysis of the results.

Figure 2 presents the distribution results for water and glass temperatures only. It is visually evident that the model exhibits greater deviation from experimental results at shallower depths compared to deeper depths. At a depth of 2 cm, the maximum deviation in water temperature from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. was 16.94%, while the maximum deviation in glass temperature was 18.87%. For depths of 4 cm, 6 cm, and 10 cm, the corresponding maximum deviations for water and glass are 9.42% and 15.72%, 11.29% and 10.69%, and 14.09% and 10.35%, respectively. The mean relative error for water at depths of 2 cm and 4 cm is 16.11% and 13.54%, respectively, while for glass, it is 14.89% and 12.84%, respectively. Similarly, at depths of 6 cm, the mean relative errors are 7.95% for water and 9.27% for glass. At a depth of 10 cm, the mean relative errors are 5.68% for water and 4.65% for glass. The numerical results also confirm that the relative errors decrease as the depth increases. Based on the validation results, it can be concluded that the numerical model simulates the distillation process with adequate accuracy.

5. Heat Balance Results

As previously mentioned, Equations (1)-(17) were numerically implemented using the 4th-order Runge-Kutta method to solve the system of ODEs. The computational program was developed using the Python programming language. This section presents the modeling results for the climatic conditions of Aktau, Kazakhstan.

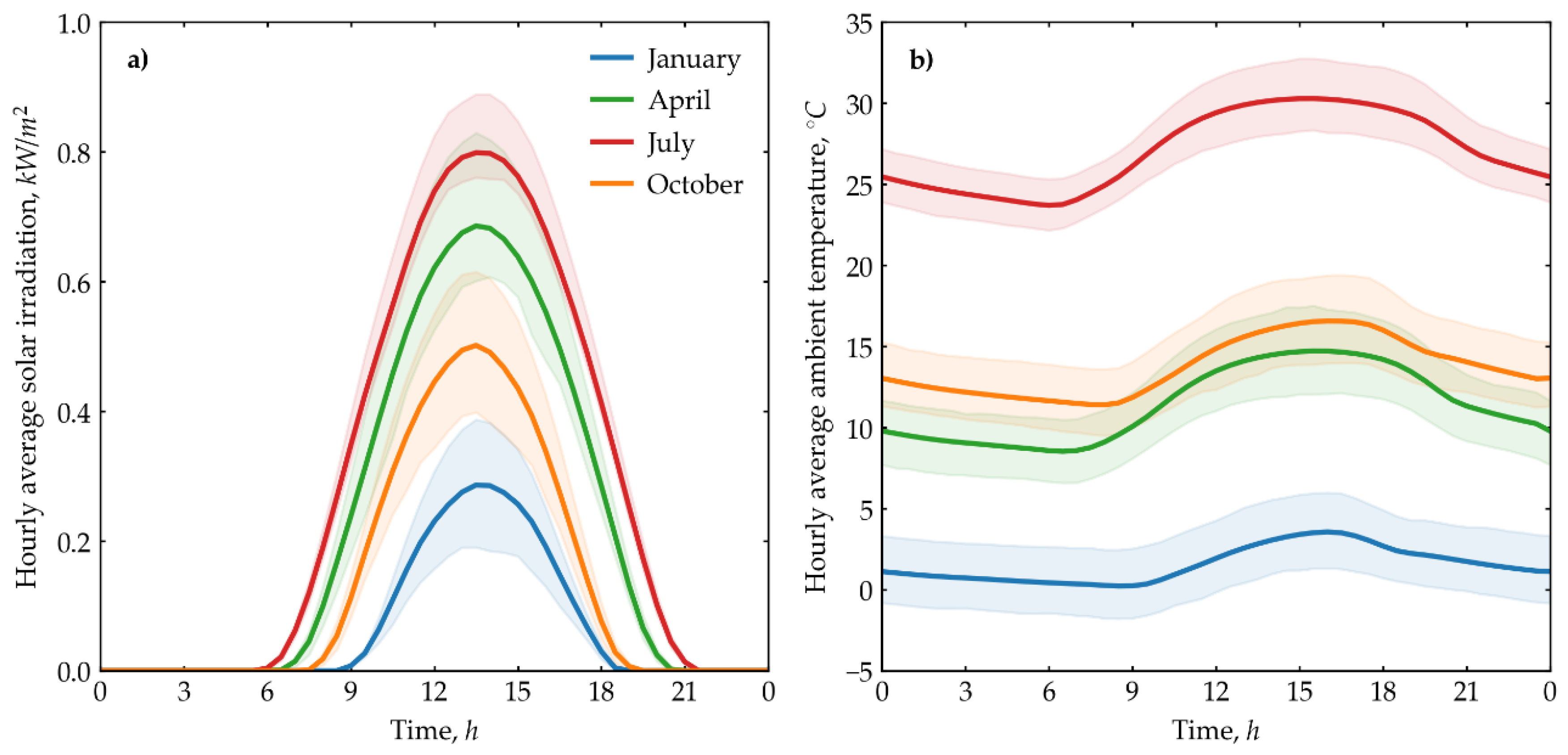

Figure 3 presents data on solar irradiation and ambient air temperature for Aktau.

The meteorological data was extracted from authoritative sources [

28]. These data were processed and averaged for a typical day in the months shown in the graph, representing the actual conditions for the corresponding season. The presented data indicate solar irradiation peaks between 12:00 and 15:00 in all seasons. The maximum values are 286 W/m² in January, 686 W/m² in April, 799 W/m² in July, and 502 W/m² in October. The minimum average temperature in January is 0.22 °C, while the maximum temperature is 3.56 °C. For April, the minimum and maximum average temperatures are 8.53 °C and 14.72 °C, respectively. In July, these values are 23.70 °C and 30.28 °C, and in October, they are 11.40 °C and 16.57 °C. As mentioned in the Introduction section, the main studies on solar stills in the literature have focused on regions with hot climates. This work differs by assessing productivity in regions with cold climates. According to climate data for Aktau, the range of average outdoor temperatures varies from 0.22 °C to 30.28 °C.

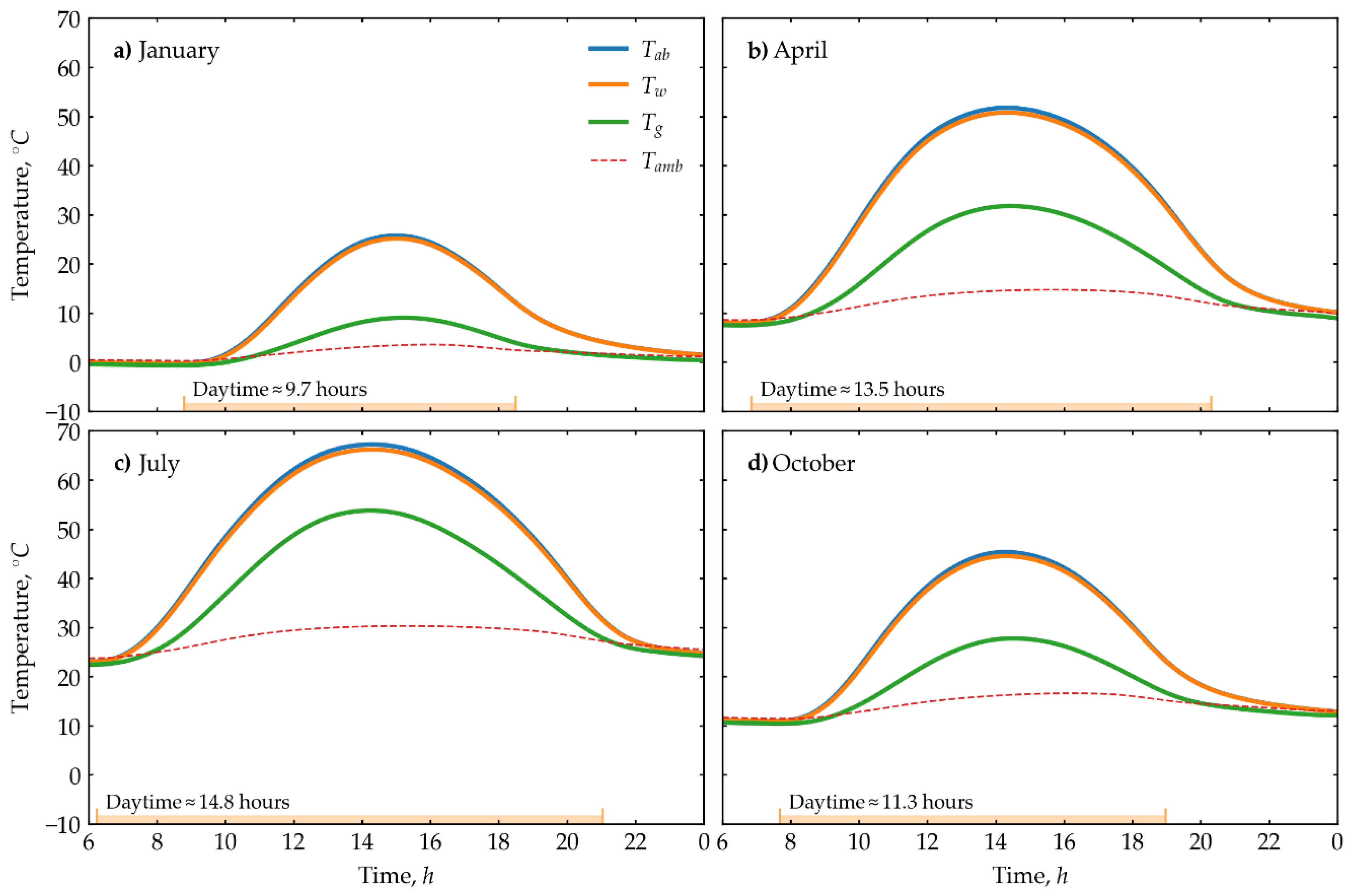

Figure 4 presents data on the temperature variation of the absorber (

), water (

), and glass (

) for the four seasons. The temperatures of the absorber and water are nearly identical across all seasons. For instance, in January, the minimum temperature of the absorber is -0.34 °C, while the water temperature is -0.37 °C. The maximum temperatures are 25.73°C for the absorber and 25.14°C for the water. Similarly, in July, the minimum temperature of the absorber is 22.99 °C, and the water temperature is 22.96 °C. The maximum temperatures are 67.23 °C for the absorber and 66.20 °C for the water. For comparison, the maximum temperature of the glass is 9.02°C in January, 31.73°C in April, 53.77°C in July, and 27.75°C in October. Consequently, the peak glass temperature in January is 64.12% lower than the peak water temperature, while in July, the difference is 18.78%.

The mathematical model, represented by Equations (1)-(17), which incorporates the specified heat transfer mechanisms within the solar still, accurately characterizes the thermal processes under the continental climate conditions of Aktau. The numerical results obtained for the temperature distribution of the solar still components align well with physical expectations.

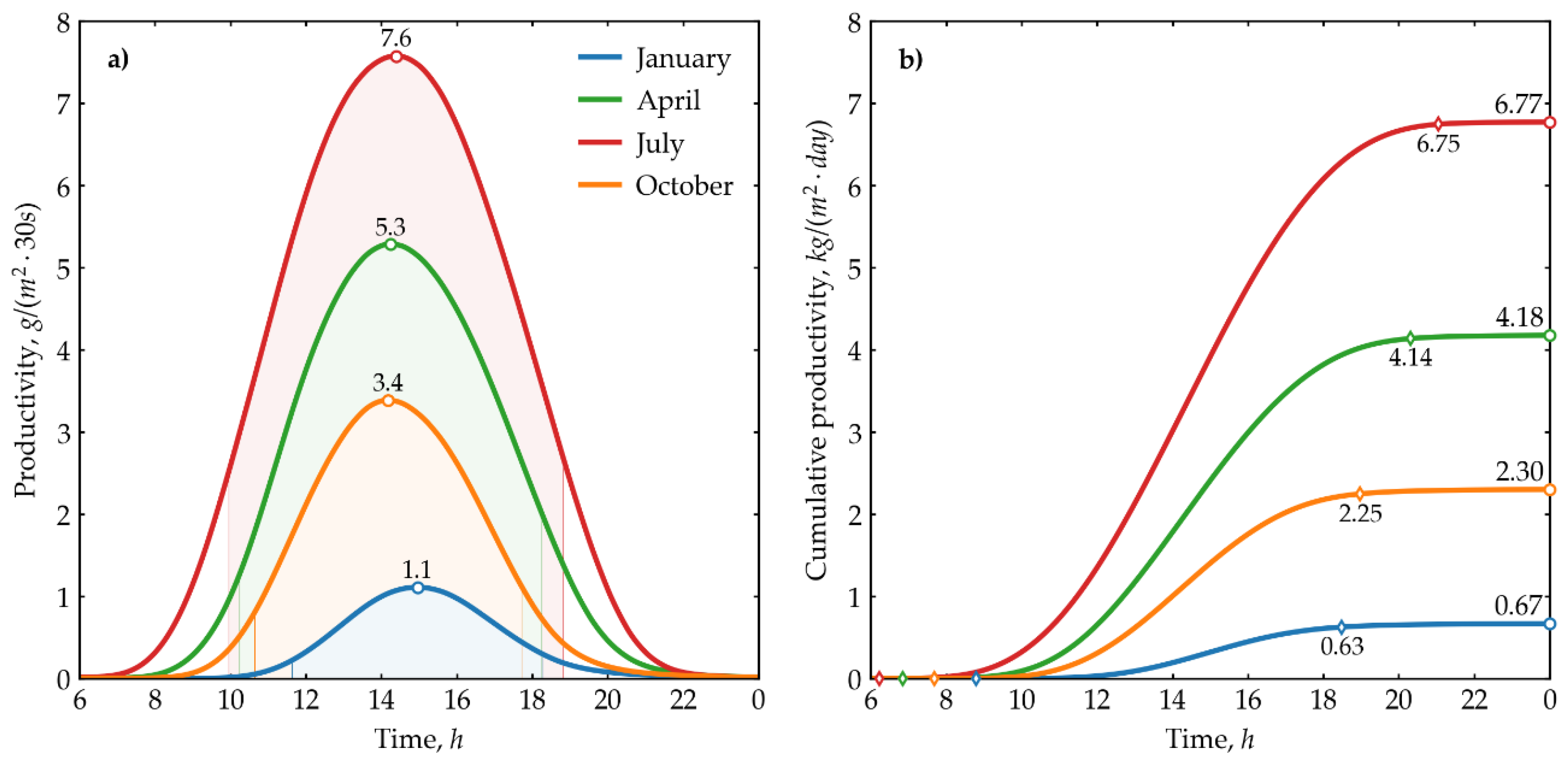

Figure 5 illustrates the instantaneous and cumulative productivity of freshwater across the four seasons. While the temperature distribution data offer insights into the internal heat exchange processes within the solar still, the productivity graph provides a more comprehensive understanding of the system’s seasonal performance.

As shown in

Figure 5a, the distribution of instantaneous productivity closely follows the distribution of solar irradiation. Peak values of instantaneous productivity correspond to peak solar irradiation, occurring between 12:00 and 15:00. The maximum instantaneous productivity is 1.1 g/(m²·30s) for January, 5.3 g/(m²·30s) for April, 7.6 g/(m²·30s) for July, and 3.4 g/(m²·30s) for October, respectively. More than 90% of productivity is produced in the area under the instantaneous productivity graph. The size of this area varies for each season, depending on the length of the day (see

Figure 5a). Cumulative productivity is an indicator of the total productivity accumulated throughout the day. As shown in

Figure 5b, the main productivity of the day accumulates at sunset. The cumulative productivity values at sunset are 0.63 kg/(m²·day) in January, 4.14 kg/(m²·day) in April, 6.75 kg/(m²·day) in July, and 2.25 kg/(m²·day) in October. Notably, cumulative productivity increases slightly after sunset; for instance, in July, cumulative productivity is 6.77 kg/(m²·day) at the end of the day compared to 6.75 kg/(m²·day) at sunset. The numerical results indicate that the productivity of the system is low during the cold seasons. Therefore, it is advisable to consider integrating the solar still with other thermal systems to enhance productivity in continental climate conditions.

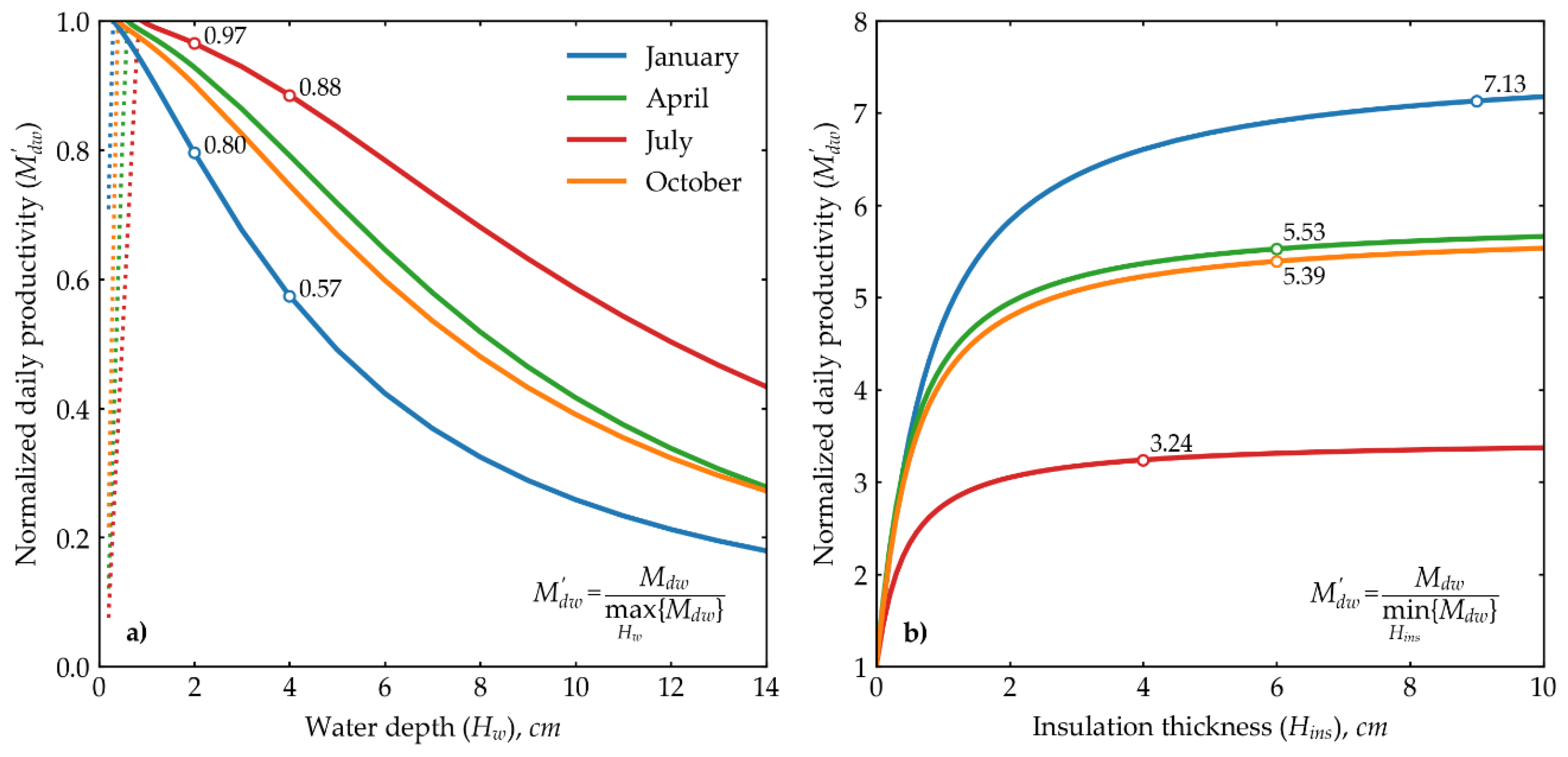

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of basin water depth and insulation thickness on the productivity of the solar still. In the calculations, the water depth ranged from 0.2 cm to 14 cm. Productivity was normalized relative to the maximum productivity value across all specified depths. Productivity is highest at shallower depths due to faster evaporation rates. However, these shallow depths are less effective at retaining heat, leading to rapid heat transfer to surrounding components. For example, in July, at a depth of 2 cm, the normalized daily productivity is 97% of the maximum, while in January it is 80%. Similar values at a depth of 4 cm in July were 88%, and in January, 57%. These results support previous findings that as the basin water depth increases, productivity decreases.

The influence of insulation thickness, ranging from without insulation case to 10 cm, was studied. In this case, productivity was normalized relative to the minimum productivity value across all specified insulation thicknesses. Accordingly, the minimum productivity will be without insulation, meaning productivity is normalized to the case without insulation.

Figure 6b illustrates that in July, a 4 cm insulation thickness increased normalized daily productivity by a factor of 3.24. Further increasing the insulation thickness by an additional 1 cm results in a productivity increase of less than 5%. Similarly, in April and October, with 6 cm of insulation, productivity increases by factors of 5.53 and 5.39, respectively. In January, at 9 cm of insulation, productivity rises by a factor of 7.13, with any additional increase in thickness yielding less than a 5% gain in productivity. These results demonstrate that insulation thickness has a substantial impact on productivity during colder seasons.

Based on the parametric analysis, it is concluded that to achieve optimal productivity in the continental climate of Aktau, the water depth in the basin should be maintained at approximately 2 cm, and the insulation thickness should range between 4 and 9 cm.

6. Caspian Region Results

This section presents the results of calculations for various cities in the Caspian region, using the developed heat balance calculation algorithm. The cities included in this analysis are Aktau and Atyrau in Kazakhstan; Astrakhan and Makhachkala in Russia; Baku in Azerbaijan; Tehran in Iran; and Turkmenbashi in Turkmenistan.

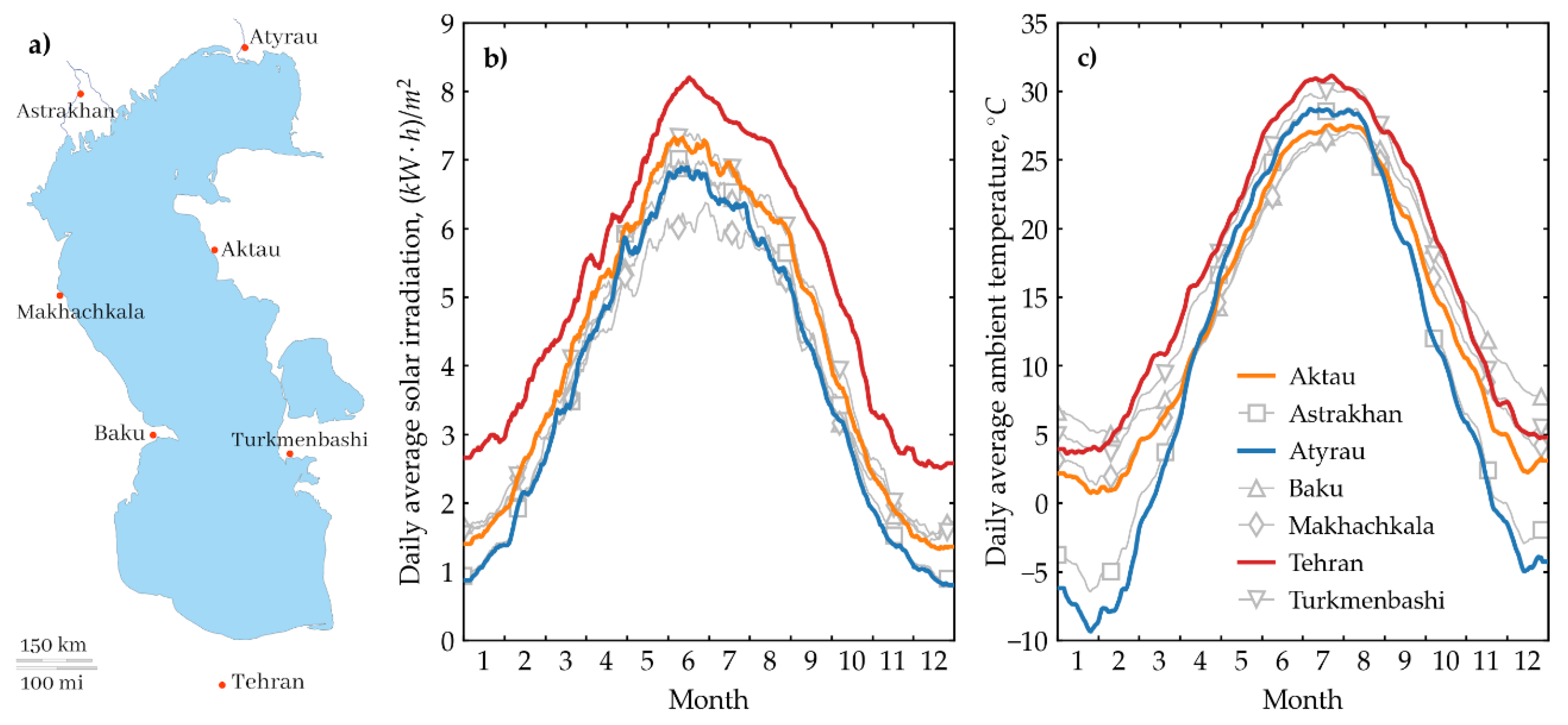

Figure 7a illustrates a map of the Caspian Sea, highlighting the locations of the specified cities. Among the cities considered, many do not face issues with access to fresh water due to their proximity to major rivers: the Ural River (Zhaiyk River) for Atyrau, the Volga River (Yedil River) for Astrakhan, the Terek River for Makhachkala, and the Kura River for Baku. Tehran is supplied by smaller rivers such as the Lar and Karaj. In contrast, the cities of Aktau and Turkmenbashi are in steppe and desert regions without access to river water, relying solely on desalinating water from the Caspian Sea. Due to population growth, the demand for large volumes of drinking water is increasing in cities such as Baku and Tehran. Baku also relies on the Caspian Sea as a source of drinking water. For Tehran, Iran utilizes the Persian Gulf, which hosts large desalination plants and extends water pipelines deep into the country. This study evaluates the productivity, efficiency, and cost of distilled water using a solar still, considering the climatic conditions of the specified cities.

Figure 7 presents meteorological data for these cities, including solar irradiation and ambient air temperature. The data shown are daily averages over the past 13 years, as reported in reference [

28]. According to the presented data, Tehran exhibits the highest levels of solar irradiation across all seasons, while Atyrau experiences the lowest solar irradiation during the cold seasons and Makhachkala during the hot seasons.

The remaining cities fall within these ranges. Regarding atmospheric air temperature, Tehran records the highest temperatures throughout all seasons, whereas Atyrau shows the lowest temperatures during the cold seasons and Makhachkala and Baku during the hot seasons.

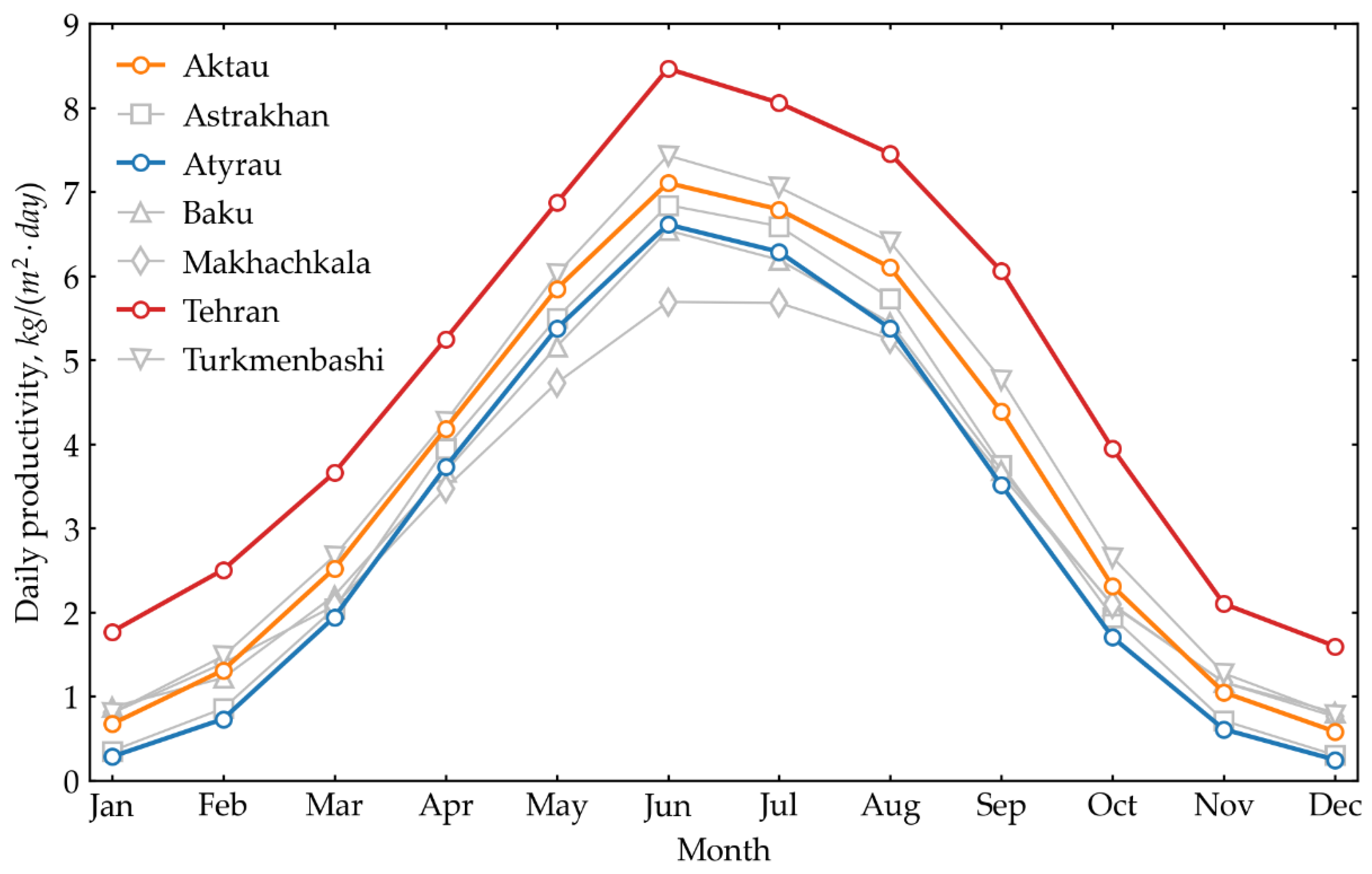

Figure 8 illustrates the average daily productivity for a typical day in each month across various cities. The figure demonstrates that Tehran achieves the highest productivity, Atyrau exhibits the lowest productivity during the cold seasons, and Makhachkala shows the lowest during the hot seasons.

The maximum productivity in Tehran is 8.47 kg/(m2·day) in June, whereas the minimum is 1.76 kg/(m2·day) in January. The maximum productivity in Atyrau is 6.61 kg/(m2·day) in June, and in Makhachkala, it is 5.69 kg/(m2·day). The minimum productivity in Atyrau occurs in January, with a value of 0.28 kg/(m2·day), while in Makhachkala, it is 0.80 kg/(m2·day). The results confirm that the productivity of the solar still is quite low, especially in cold seasons for all these cities. Therefore, it would make sense to combine solar stills with other thermal desalination systems to increase productivity and decarbonize existing fossil fuel thermal desalination systems.

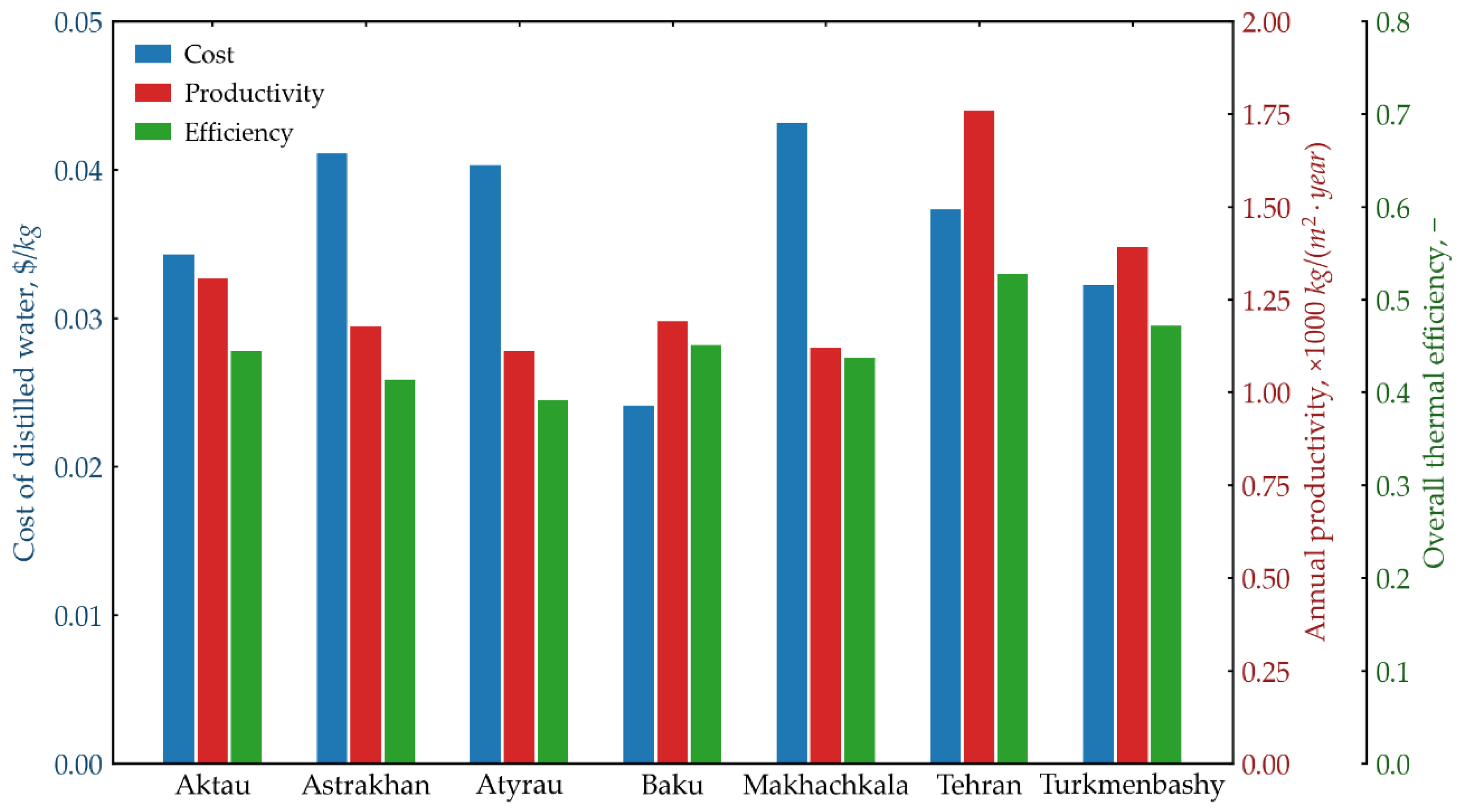

Next, according to Equations (15)-(17), the annual productivity and thermal efficiency of the solar still are evaluated. Based on Equations (18)-(25), the cost of distilled water is estimated for the specified cities in the Caspian region.

Figure 9 presents the results. The highest productivity is observed in Tehran with a value of 1760 kg/(m²·year). Following Tehran, Turkmenbashi has a productivity of 1391 kg/(m²·year), Aktau 1308 kg/(m²·year), Baku 1191 kg/(m²·year), Astrakhan 1178 kg/(m²·year), Makhachkala 1120 kg/(m²·year), and Atyrau 1308 kg/(m²·year). According to the efficiency of the solar still, calculated using Equation (17), a different ranking order is obtained. Tehran ranks first with an efficiency of 0.53, followed by Turkmenbashi at 0.47, Baku at 0.45, Aktau and Makhachkala both at 0.44, Astrakhan at 0.41, and Atyrau at 0.39

The obtained numerical data are consistent with the results reported by other authors in the open literature.

Capital costs () were estimated based on material prices in the specified countries. The annual interest rate () was adopted according to available online data for these countries. The system’s operating lifetime () was assumed to be 15 years. According to the data obtained, among these cities, the cheapest distilled water is produced in Baku 0.024 USD/kg, then Turkmenbashi 0.032 USD/kg, then Aktau 0.034 USD/kg, Tehran 0.037 USD/kg, Atyrau 0.040 USD/kg, Astrakhan 0.041 USD/kg, and Makhachkala 0.043 USD/kg. As previously mentioned, this work evaluates the efficiency and performance of a conventional solar still. The Caspian region is rich in natural resources, with access to inexpensive energy sources such as natural gas and oil. Therefore, combining solar still with thermal desalination systems that utilize natural gas is feasible. This integration can enhance the productivity of distilled water and subsequently reduce the cost of pure water. Additionally, it will facilitate the decarbonization of fossil fuel-based thermal desalination systems by incorporating solar thermal energy. The potential of integrating solar stills with other technologies in the Caspian region will be investigated in future research.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive numerical estimation of the productivity of single-slope solar stills in the Caspian region, focusing on key cities such as Aktau, Atyrau, Astrakhan, Makhachkala, Baku, Tehran, and Turkmenbashi. Utilizing a mathematical model based on heat balance equations and implemented using the 4th-order Runge-Kutta method, we have successfully simulated the distillation process under various climatic conditions.

The numerical results indicate that the productivity of solar stills is highly dependent on both the geographic location and the corresponding meteorological conditions. Tehran exhibited the highest productivity across all seasons due to its favorable solar irradiation and ambient temperature profiles. Conversely, Atyrau and Makhachkala showed lower productivity, particularly during the cold seasons, highlighting the significant impact of ambient temperature on the efficiency of solar distillation.

Our parametric analysis further elucidates the critical factors affecting the productivity of solar stills. The optimal water depth in the basin was identified to be around 2 cm, while the insulation thickness ranged between 4 and 9 cm for maximizing productivity in the continental climate of Aktau. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing design parameters to enhance the performance of solar stills in specific climatic regions.

The maximum productivity and efficiency were obtained for Tehran, with values of 1760 kg/(m²·year) and 0.53, respectively. The minimum cost of distilled water was $0.024 per kilogram in Baku.

The results obtained in this research are consistent with existing literature, providing a robust validation of our numerical model. Future work will focus on exploring the integration of solar stills with other renewable energy technologies and fossil fuel-based systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., S.S., T.R., M.M. and Y.B.; methodology, Y.Y., T.R., M.M., and Y.B.; software, D.B., Y.Y., Y.K.; validation, D.B., Y.Y., Y.K.; formal analysis, D.B., Y.Y., and Y.K.; investigation, D.B., Y.Y., Y.K., and Y.B.; resources, S.S., T.R., M.M., and Y.B.; data curation, D.B., Y.Y., Y.K.; writing - original draft preparation, Y.B.; writing - review & editing, T.R., and M.M.; visualization, D.B., Y.Y., Y.K.; supervision, M.M., and Y.B.; project administration, D.B., S.S. and Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan Grant No. AP14871988 “Development of a solar-thermal desalination plant based on a heat pump”.

Acknowledgments

Postdoctoral Research Program for Ye. Belyayev, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan. Postdoctoral Research Program for D. Baimbetov, the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| A |

Surface area (m2) |

| AMC |

Annual maintenance cost (USD) |

| AOC |

Annual operating cost (USD) |

| ASV |

Annual salvage value |

| C |

Specific heat capacity (J/kg) |

|

Cost of distilled water (USD) |

| CC |

Capital cost of solar still (USD) |

| CRF |

Capital recovery factor |

| FAC |

Fixed annual cost (USD) |

| H |

Thickness/ depth (m) |

| h |

Heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2 ) |

|

Latent heat (J/kg) |

| I |

Solar irradiation (W/m2) |

| i |

Interest rate per year |

| k |

Thermal conductivity coefficient (W/m) |

| L |

Length (m) |

| L’ |

Characteristic length |

| m |

Mass (kg) |

|

Instantaneous productivity (kg/m2s) |

|

Daily productivity (kg/m2 day) |

| M |

Annual productivity (kg/m2year) |

| n |

Lifetime of the system (year) |

| P |

Pressure (Pa) |

| Pr |

Prandtl number |

| R |

Reflectivity |

| Ra |

Rayleigh number |

| S |

Salinity (g/kg) |

| SFF |

Sinking Fund Factor |

| SV |

Salvage value |

| t |

Time (s) |

| T |

Temperature () |

| TAC |

Total annualized cost (USD) |

| U |

Overall heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2 ) |

| V |

Wind speed (m/s) |

| W |

Width (m) |

| Greek symbol |

| α |

Absorptivity |

| ε |

Emissivity |

| η |

efficiency |

| σ |

Stefan–Boltzmann constant (W/(m2K4) |

| Subscripts |

| ab |

absorber |

| amb |

ambient |

| c |

convective |

| dw |

distilled water |

| e |

evaporative |

| eff |

effective |

| g |

glass |

| ins |

insulation |

| r |

radiative |

| sky |

sky |

| t |

total |

| w |

water |

Appendix

The Rayleigh number (Ra) is defined as follows:

Properties of fluid are determined at temperature:

where subscript s is for the solid temperature, f is for the fluid temperature.

Seawater properties of saline water with temperature in °C and salinity in g/kg.

Density,

:

where

with

Thermal conductivity,

:

where

and

– thermal conductivity of distilled water in critical point,

– critical temperature of distilled water.

Dynamic viscosity,

:

where

with pure water viscosity

Latent heat of vaporization,

:

with pure water property

Specific heat capacity of saline water,

:

where

Vapor pressure,

:

with pure water property

References

- Elsheikh, A.; Hammoodi, K.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.M.; Mourad, A.-H.I.; Fujii, M.; Abd-Elaziem, W. Augmentation and evaluation of solar still performance: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2024, 574, 117239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, O.; Hussein, A.K.; Attia, M.E.H.; Aljibori, H.S.S.; Kolsi, L.; Togun, H.; Ali, B.; Abderrahmane, A.; Subkrajang, K.; Jirawattanapanit, A. Comprehensive review on solar stills – latest developments and overview. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.S.; Essa, F.A.; Panchal, H.; Alawee, W.H.; Elsheikh, A.H. Enhancing the performance of tubular solar stills for water purification: A comprehensive review and comparative analysis of methodologies and materials. Results in Engineering 2024, 21, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.K.; Rashid, F.L.; Abed, A.M.; Al-Khaleel, M.; Togun, H.; Ali, B.; Akkurt, N.; Malekshah, E.H.; Biswal, U.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; et al. Inverted solar stills: A comprehensive review of designs, mathematical models, performance, and modern combinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, F.L.; Kaood, A.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Mohammed, H.I.; Alsarayreh, A.A.; Al-Muhsen, N.F.O.; Abbas, A.S.; Zubo, R.H.A.; Mohammad, A.T.; Alsadaie, S.; et al. A review of configurations, capabilities, and cutting-edge options for multistage solar stills in water desalination. Designs 2023, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, S.M.; Mansour, R.B.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Rehman, S. Renewable energy systems for water desalination applications: A comprehensive review. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 286, 117035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, E.T.; Olabi, A.G.; Elsaid, K.; Al Radi, M.; Alqadi, R.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Recent progress in renewable energy based-desalination in the Middle East and North Africa MENA region. Journal of Advanced Research 2023, 48, 125–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyayev, Ye.; Mohanraj, M.; Jayaraj, S.; Kaltayev, A. Thermal performance simulation of a heat pump assisted solar desalination system for Kazakhstan climatic conditions. Heat Transfer Engineering 2019, 40, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, Ye.; Saparova, B.; Belyayev, Ye.; Kaltayev, A.; Mohanraj, M.; Jayaraj, S. Numerical simulation of a heat pump assisted regenerative solar still with PCM heat storage for cold climates of Kazakhstan. Thermal Science 2017, 21, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.S.; Hassan, H.; Ahmed, M.; Ookawara, S. Energy and exergy analysis of single slope passive solar still under Egyptian climate conditions. Energy Procedia 2017, 141, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujazar, M.S.S.; Fatihah, S.; Lotfy, E.R.; Kabeel, A.E.; Sharil, S. Performance evaluation of inclined copper-stepped solar still in a wet tropical climate. Desalination 2018, 425, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfe, M.H.; Toghraie, D. Numerical investigation of wind velocity effects on evaporation rate of passive single-slope solar stills in Khuzestan province in Iran. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 62, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, A.; Yadav, A.C.; Kumar, A. Performance analysis of single slope solar still under composite climate in India: Numerical simulation and thermal modeling approach. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 63, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomor, E.; Islam, R.; Alim, M.A.; Rahman, A. Production of fresh water by a solar still: An experimental case study in Australia. Water 2021, 13, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Helal, I.M.; Alsadon, A.; Marey, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Shady, M.R. Optimizing a single-slope solar still for fresh-water production in the deserts of arid regions: An experimental and numerical approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.V.; Patel, S.K.; Patel, A.M. Impact of modification in the geometry of absorber plate on the productivity of solar still – A review. Solar Energy 2023, 264, 112009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serradj, D.E.B.; Anderson, T.; Nates, R. The effect of geometry on the yield of fresh water from single slope solar stills. Energies 2022, 15, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, E.A.; Hameed, R.M.S.; Illyas, M.; Athikesavan, M.M. Experimental investigation of inclined solar still with and without sand as energy storage materials. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katekar, V.P.; Deshmukh, S.S. A review of the use of phase change materials on performance of solar stills. Journal of Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeel, A.E.; El-Samadonya, Y.A.F.; El-Maghlany, W.M. Comparative study on the solar still performance utilizing different PCM. Desalination 2018, 432, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, R.V. Solar water distillation: The roof type still and multiple effect diffusion still. International Developments in Heat Transfer, ASME, Proceedings of International Heat Transfer, University of Colorado 1961, 5, 895–902.

- Shukla, S.K.; Sorayan, V.P.S. Thermal modeling of solar stills an experimental validation. Renewable Energy 2005, 30, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer. Wiley 2017.

- Halima, H.B.; Frikha, N.; Slama, R.B. Numerical investigation of a simple solar still coupled to a compression heat pump. Desalination 2014, 337, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaseenivasan, T.; Shanmugam, R.K.; Hareesh, V.M.; Srithar, K. Combined probation of bubble column humidification dehumidification desalination system using solar collectors. Energy 2016, 116, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, S.; Siva, K.; Mohanraj, M. Energy performance and economic assessments of a solar air collector and compression heat pump-integrated solar humidifier desalination system. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering 2023, 237–235, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Rana, R.S.; Srivastava, P.K. Heat transfer coefficients and productivity of a single slope single basin solar still in Indian climatic condition: Experimental and theoretical comparison. Resource-Efficient Technologies 2017, 3, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The data was obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Langley Research Center (LaRC) Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource (POWER) Project funded through the NASA Earth Science/Applied Science Program. The data was obtained from the POWER Project’s Hourly 2.0.0 version on 2024/05/02.

- Belessiotis, V.; Kalogirou, S.; Delyannis, E. Thermal Solar Desalination. Methods and Systems. Academic Press 2016.

- Shahrim, N.A.; Abounahia, N.M.; Ahmed El-Sayed, A.M.; Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J. An overview on the progress in produced water desalination by membrane-based technology. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 51, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharqawy, M.H.; Lienhard, J.H.V.; Zubair, S.M. Thermophysical properties of seawater: A review of existing correlations and data. Desalination and Water Treatment 2010, 16, 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of and/or the editor(s). and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).