1. Introduction

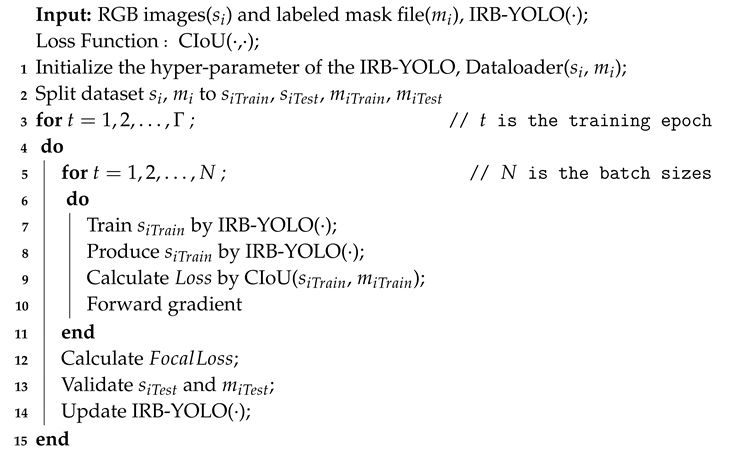

Vatica, due to its widely used fruit and timber and its pivotal role in forest ecosystems, has significant global impact. However, due to habitat loss and pest invasions, its survival status has been in decline, leading to its listing on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. To achieve precise pesticide application control, conduct scientific pruning, and effective post-harvest management, the development of models that can accurately assess canopy structure becomes particularly important. The technical approach is outlined in

Figure 1.

With the development of precision agriculture technologies, drone technology has been widely applied in the agricultural sector.Sen Shen proposed DFA Net [

1], integrating attention mechanisms to achieve effective fusion of infrared and visible light images from unmanned aerial vehicles for enhancing object detection and detail representation. Ruiyi Zhang introduced GA-Net [

2], an accurate and efficient drone image object detection method based on grid activation, which improves detection speed and accuracy by reducing redundant calculations and focusing on key areas. Complex modeling needs in agriculture are met through deep learning frameworks in the field of computer vision. Zhengxin Zhang [

3] addressed the issue of scale variation in drone imagery by proposing a strategy combining a three-level Pyramid Feature Fusion Network (PAFPN) with a specialized head module for small object detection. YOLO-FD [

4], based on the YOLOv5 framework, captures static and dynamic contextual information in citrus defect images through the construction of the CoT3 module.

Mask R-CNN [

5] extends Fast R-CNN [

6] by adding a parallel mask branch for pixel-level classification. FCN [

7] transforms fully connected layers into convolutional layers and uses skipping connections to fuse multi-scale features, effectively compensating for information loss during downsampling. SegNet [

8] uses unpooling operations instead of deconvolutions in FCNs to restore the scale of feature maps., preserving high-frequency information while reducing computational load. ResNet [

9] and RefineNet [

10] utilize residual connections to make full use of the information during downsampling. PSPNet [

11] captures global context information using a pyramid pool module, enhancing the model’s perception of image details and global structures. Despite CNNs capturing local features through convolution operations, they cannot establish long-range connections between pixels, leading to relatively low accuracy in pure CNN models.

On the other hand, the introduction of Vision Transformer [

12] has sparked significant change in the field of computer vision. The attention mechanism within these models enables better modeling of long-range dependencies, thereby improving accuracy but also increasing resource consumption. To address this issue, PVT [

13] introduces the SRA module, which improves the standard MHSA and reduces the computation of the QKV matrices. In contrast, Swin Transformer [

14] utilizes W-MSA + SW-MSA mechanisms to confine self-attention to individual windows, effectively addressing the problem of memory usage. Although these networks have made various optimizations to reduce resource consumption, the inherent parameter bloat and quadratic growth in computational cost associated with the multi-head self-attention mechanism still results in high computational requirements, limiting their practical applications in industrial settings.

In the field of agricultural remote sensing, target detection models such as R-CNN [

15], SPP-Net [

16], and YOLO [

17] have been widely applied. Although these models can provide bounding boxes representing predicted targets, these boxes often originate from prior-designed candidate regions or coarse grid regressions, making them insufficient for the precision required in some fine-grained remote sensing tasks. With the introduction of semantic segmentation models like FCN [

7], U-Net [

18], and Deeplab-V1 [

19], these models achieve higher precision by classifying each pixel in the image, resulting in more accurate object masks. However, this finer processing comes with increased computational demands, placing a significant disadvantage on semantic segmentation models in terms of resource consumption. Since the introduction of Mask R-CNN [

5] by Kaiming He, instance segmentation models have come into focus. Unlike semantic segmentation models, instance segmentation models typically incorporate a target detection component to localize objects in the image and then perform pixel-level classification on each proposed region, significantly reducing computational load and achieving a balance between precision and resource consumption.

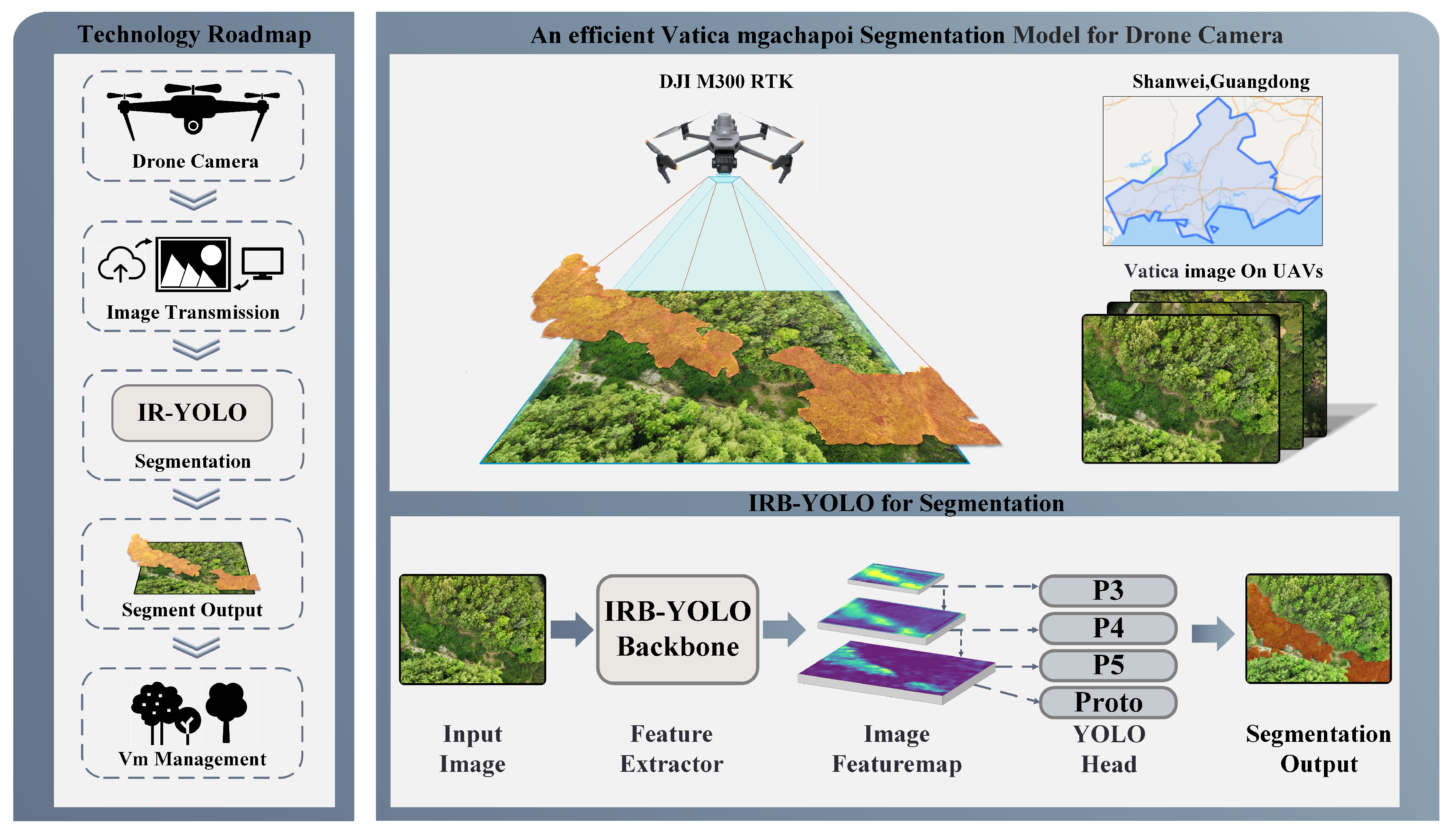

The inference results of different visual task models are illustrated in

Figure 2. This study focuses on the precise localization of the center of the Vatica canopy. For object detection models, the most valuable part of their inference results is the geometric center of the bounding boxes. However, due to the precision and rectangular shape limitations of the bounding boxes, their geometric centers cannot accurately represent the centers of polygonal canopies. Although the inference results of semantic segmentation models can better depict the edges of the canopy, since semantic segmentation segments by class, the model treats the segmentation results of the same class as a single entity. It requires image processing to obtain the canopy masks corresponding to each tree, which inevitably leads to a loss in accuracy; instance segmentation models segment individual instances, meaning they perform pixel-level segmentation for each instance that the model considers might be a tree. Their inference results are typically independent, allowing for the direct calculation of the centroid of each instance’s segmentation mask to locate the canopy center. Based on the above discussion, this study selects the instance segmentation model YOLOv8-Seg as the baseline model.

In the context of drone deployment, deep learning models face challenges in balancing computational efficiency, resource constraints, and model complexity. Drones require lightweight models with real-time processing capabilities, while high-precision complex models typically consume significant computational resources, which contrasts with drones’ limited edge computing resources. In drone applications, models need to maintain consistent performance under varying lighting conditions, climate factors, and other conditions, requiring a focus not only on efficiency and accuracy but also on robustness. For the Vatica scene, deploying models on drones presents additional challenges. The lower height of Vatica trees results in a low effective pixel ratio in images, increasing the difficulty of recognition. Moreover, the limited geographic distribution of Vatica fields leads to a scarcity of high-quality annotated data, impacting the model’s learning and generalization capabilities. In this context, we propose a lightweight and efficient model, IRB-YOLO (Inverted Residual Block-YOLO).

The main contributions of this article are summarized as follows:

(1) We propose an efficient model, IRB-YOLO, which is designed after rethinking the power of inverted residual blocks in MobileNet series, achieving highly efficiency representation learning through the integration of depth wise separable convolutions(DW-Conv) and multi-head self-attention(MHSA).

(2) IRB-YOLO is well-balanced between accuracy and latency, demonstrating the superiority of YOLO framework and the backbone based on inverted residual block in such various challenging tasks like object detection and segmentation for drones.

(3) We train the IRB-YOLO with CIoU as the loss function in the segmentation task of Vatica trees, overcoming the shortage of ignoring central points and aspect ratio. The ablation experiments reveal that, such the CIoU that get a better performance than the original loss function(GIoU and DIoU) in YOLOv8, accelerating the training process and bringing the bounding boxes closer to the ground truth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials of Dataset

With the continuous evolution of agricultural drone technology and its expanding applications, agricultural drones have evolved beyond mere aerial platforms to become integral parts of smart agricultural ecosystems. Current visual algorithms often prioritize architecture expansion and increased computational load for marginal accuracy gains, overlooking model efficiency constraints in edge computing environments.

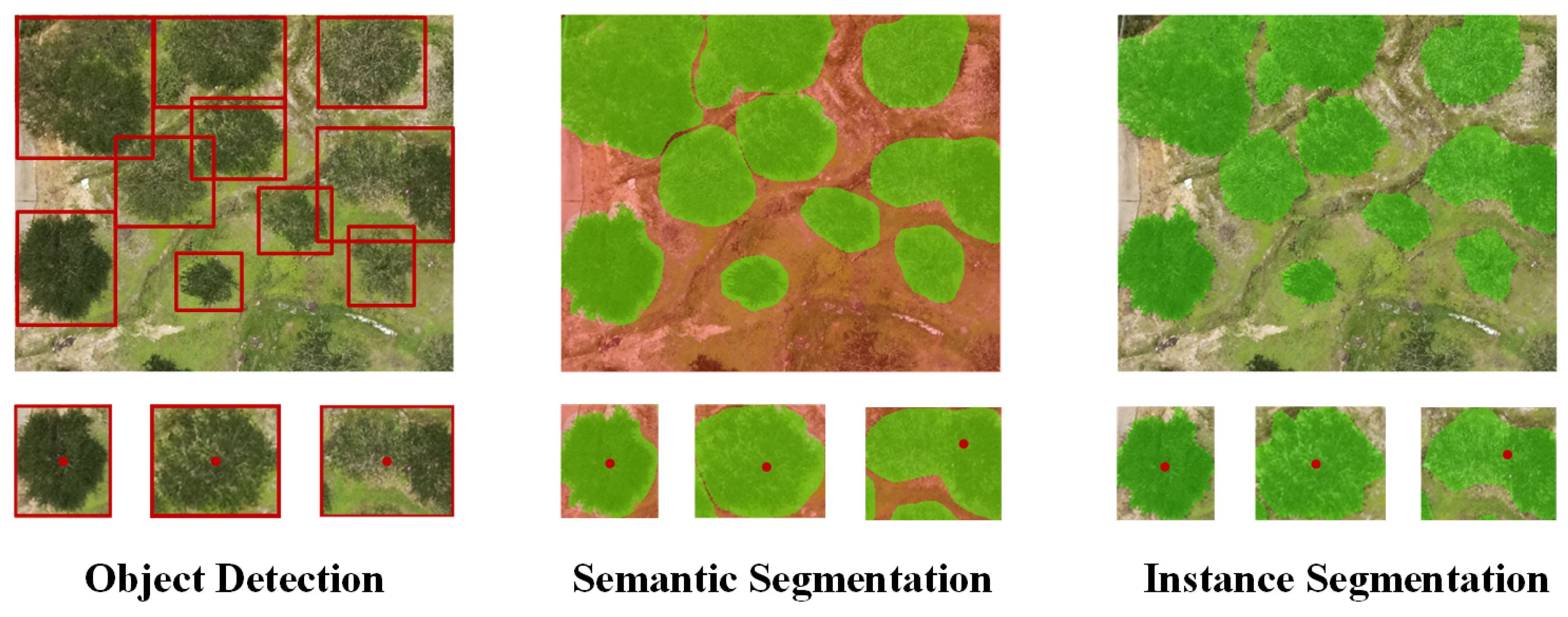

This paper evaluates the IRB-YOLO model using high-resolution images of green plum tree canopies captured by a DJI M300 RTK multi-sensor drone at altitudes ranging from 47.113 to 124.092 meters, where each pixel represents 2.35 to 6.19 meters. The Vatica dataset used in this study comprises 583 RGB images (5280×3956 pixels) with standard visible light spectrum (

Figure 3), collected from a plum orchard in Dongkeng Town, Luhhe County, Shanwei City, Guangdong Province (114.03°E, 22.75°N) between March and July. This period covers the full lifecycle of green plum fruits, ensuring the dataset adequately represents the specific species. The dataset also includes two canopy types: densely unpruned natural growth (

Figure 3a) and isolated pruned (

Figure 3c), aiming to enable comprehensive adaptation and learning of green plum trees under varying conditions.

Past research has focused on single-species datasets, improving accuracy but lacking generalization in cross-species scenarios. To enhance model robustness, this study expanded the plum tree dataset by incorporating data from two different tree species with similar morphological and textural features, resulting in a mixed dataset. The mixed dataset includes a plum tree-pine tree(

Figure 2b) dataset representing densely unpruned plum trees and a plum tree-lychee tree(

Figure 2d) dataset representing isolated pruned plum trees. Images were obtained using the same drone imaging strategy from fieldwork in Guangzhou and Qingyuan, Guangdong Province. This study aims to integrate information from other tree species to help the model learn common features, enhancing its generalization capability in cross-species scenarios.

2.2. IRB-YOLO Network

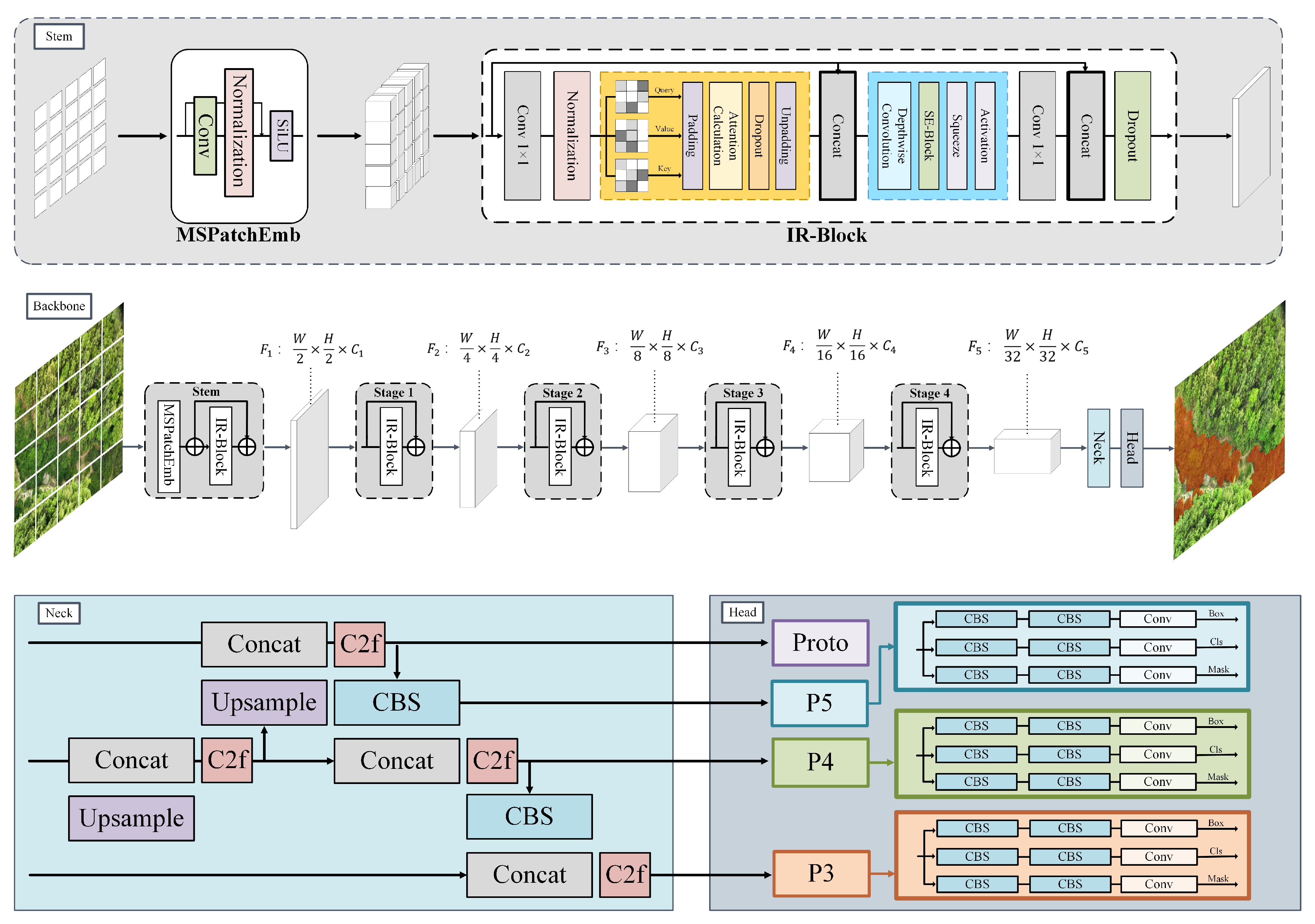

To accommodate the deployment requirements for edge computing scenarios in drones, we developed an efficient network model based on YOLOv8-Seg, named IRB-YOLO (

Figure 4). This network is composed of three primary components: Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone is tasked with extracting features from input images; the Neck module implements the extraction and fusion of multi-scale features; the Head module outputs predictions for bounding boxes, classes, and segmentation masks, which can be used to compute the corresponding loss to support backpropagation.

Based on predefined hyperparameters, three-channel input images are initially fed into the Stem component of the Backbone. Here, the channel count is expanded by the MSPatchEmb module, followed by normalization and the introduction of nonlinear activation. Within each layer of the Backbone, the IR-Block first utilizes 1×1 convolutions to acquire high-dimensional representations of features, then constructs attention matrices to establish long-range dependencies among pixels. Following this, depthwise separable convolutions (DW-Conv) are employed to capture local features, and finally, 1×1 convolutions reduce the feature dimensions back to their original state before concatenation with the original input, producing a feature map rich in multidimensional characteristics.

Neck component is a key element for extracting and fusing features at different scales. It uses upsampling to restore detail information and enhance spatial resolution, enabling accurate segmentation. The Neck employs Concat operations to integrate semantic information across different scales and abstraction levels, ultimately generating feature maps of varying dimensions through the C2f module. The C2f module processes the input data into two branches: one branch is output directly, while the other branch undergoes transformations through multiple Bottleneck blocks before being output. This design enables the network to better model complex data.

Head receives multi-scale feature maps from the neck for segmentation tasks. The high-resolution feature map, which is closest to the original image size, enters the Proto branch; this branch upsamples its spatial dimensions by a factor of two to generate prototype mask feature maps. All feature maps from the neck are fed into the segmentation block. This block uses three distinct convolutional paths to generate feature maps corresponding to Box, Cls, and Mask, enabling precise pixel-level classification. Finally, the Box Loss, Cls Loss, and Seg Loss are calculated separately and backpropagated to optimize the network weights.

IRB-YOLO has network architectures of varying sizes, with network parameters shown in

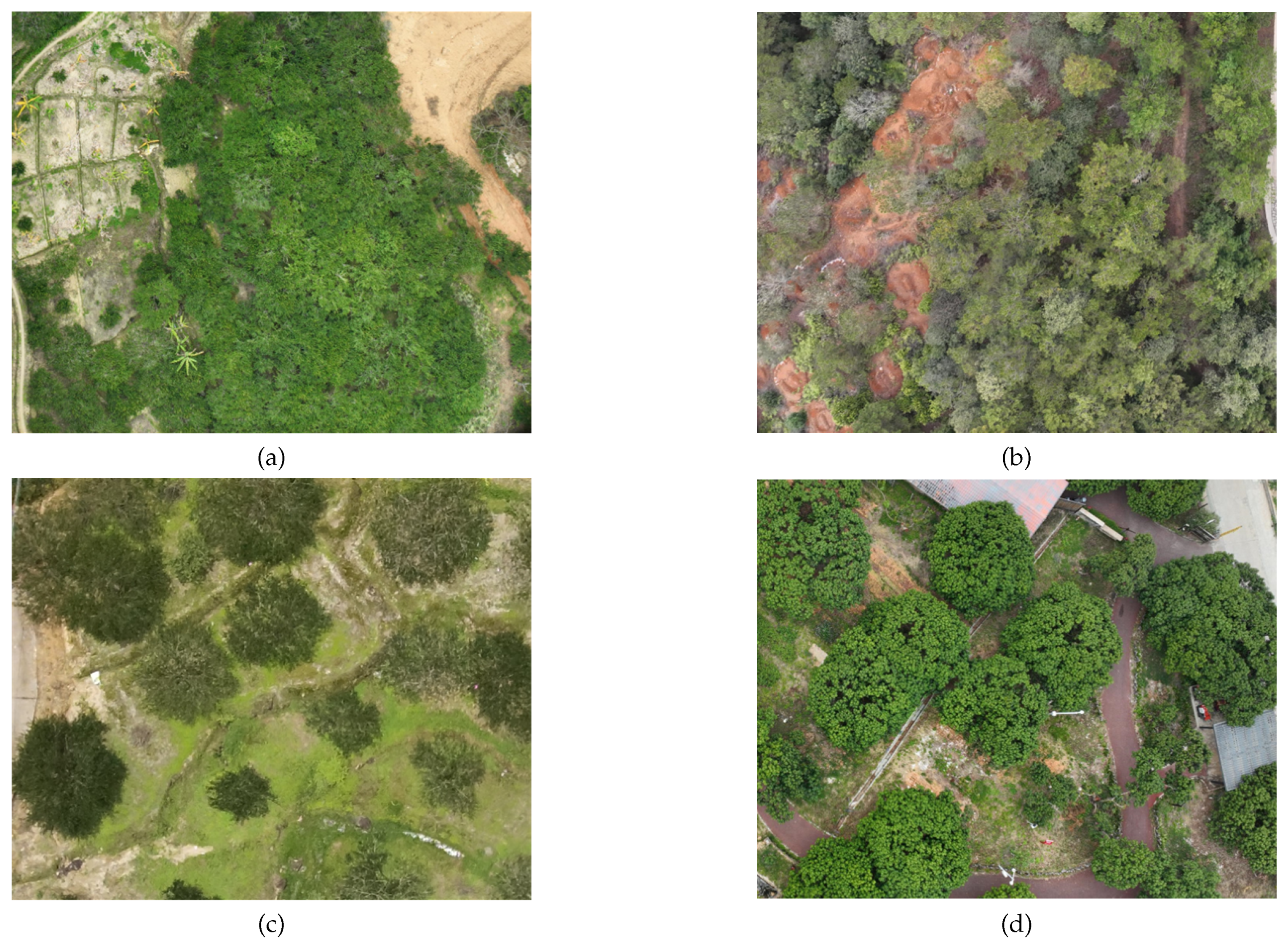

Table 1. The network primarily consists of Convolution Layers and Inverted Residual Blocks, . In Stages 1-4, Inverted Residual Blocks are used, which are composed of combinations of one or multiple 1×1 convolution layers plus 3×3 convolution layers. This paper provides models of different computational costs, allowing users to adjust the number of convolution kernels in the Inverted Residual Blocks according to the needs of specific tasks. The training pseudocode for IRB-YOLO is shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1:Training Algorithm of IRB-YOLO |

|

2.3. Efficiency Components

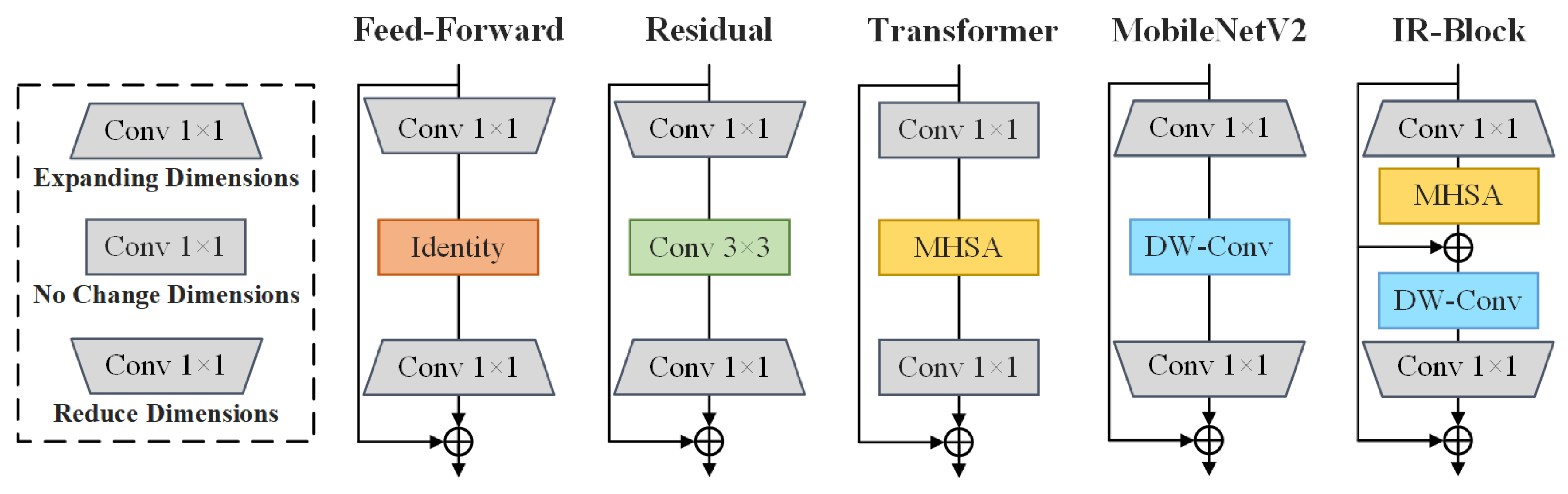

Early feed-forward neural networks [

20] were constrained by the computational capabilities available at the time, making it challenging to handle the significant computational load imposed by high-dimensional feature maps within the network. Researchers adopted a strategy that involved reducing the input dimensionality to extract salient features and subsequently restoring the output dimensionality. Numerous experiments validated the effectiveness of this architecture. ResNet [

9] inherited this efficient design philosophy and innovatively introduced the residual connection mechanism, enabling the model to learn features across different dimensions simultaneously. These characteristics are considered fundamental building blocks for constructing efficient convolutional neural network modules. With the widespread application of high-performance computing chips in deep learning, large-scale models based on Transformer architectures have rapidly developed. Since Vaswani first introduced MHSA [

21], visual models have been able to map pixel information into high-dimensional vector spaces through matrix operations and normalization in attention mechanisms, effectively capturing long-range dependencies between pixels to enhance classification accuracy [

12]. However, Transformer architectures typically require extensive attention computations to ensure performance, leading to substantial computational costs and inevitably impacting inference speed. In recent years, with the increasing demand for deploying models on mobile devices with limited storage and computational resources, many efficient models incorporating lightweight CNN designs have emerged. MobileNet [

22] introduced DW-Conv, which significantly reduced the model’s parameter count and computational requirements, greatly improving deployment efficiency on resource-constrained platforms. Building upon DW-Conv, MobileNetV2 [

23] further proposed inverted residual blocks (IRBs) with linear bottlenecks. This inverted residual structure reverses the traditional dimensionality reduction mindset, instead employing an expansion of the input dimensions. This strategy achieves better feature extraction with only a slight increase in computational cost, enabling more efficient feature mapping and transmission. To maintain excellent feature capture capability while achieving lightness, this paper proposes IR-Block, an efficient component inspired by inverted residual structures and multi-head self-attention (MHSA). IR-Block combines the strengths of CNNs and Transformers. It models local features and global features through DW-Conv and MHSA, respectively. Based on the inverted residual structure, IR-Block obtains high-dimensional representations of input features, providing a richer feature space for both MHSA and DW-Conv. Although MHSA requires substantial computational resources when dealing with high-dimensional vectors, the fact that each convolution kernel in DW-Conv operates on a single channel results in much lower computational cost compared to standard convolution kernels. Consequently, the additional computational burden caused by expanding feature dimensions and the introduction of MHSA remains within an acceptable range. A comparison of the representative components mentioned above is shown in

Figure 5.

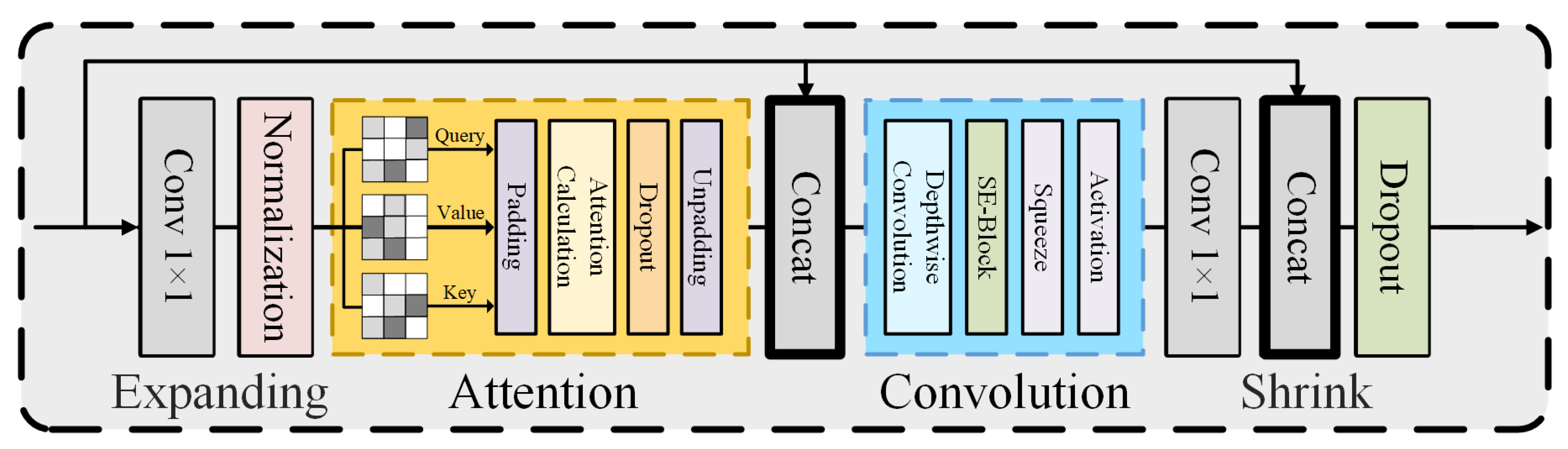

2.4. Inverted Residual Block

The IR-Block also employs an inverted residual structure, consisting of simple attention blocks and DW-Conv blocks to capture the expanded feature information (

Figure 6). The IR-Block first expands the channel dimensions of the input.The expanded result

can be expressed as (

1)

where

is the ratio of input to output channels, and

represents the expansion convolution. After the input is expanded, it first enters the MHSA block to compute the

and

matrices separately. The obtained attention weights are then multiplied with

to produce the output,capture low-frequency signals providing global information, and construct long-range interactions among pixels in high-dimensional space.

after passing through the MHSA can be expressed as (

2)

Perform a Concat operation on

to concatenate it with the original input

X, forming a fused feature representation. The expression for the final output

is shown in (

3)

The output from MHSA is combined through skipping connections and processed by DW-Conv, constructing short-range dependencies and fusing multi-level semantic information without expanding the dimensions.

,the result of the DW-Conv, can be represented as in (

4)

Finally, an inverted output/input

convolution kernel is used to contract the IR-Block. The shrank result

can be expressed as (

5)

are concatenated with the original input

X via a residual connection to form an enhanced feature representation. The expression for the final output

Y is shown in (

6)

IR-Block has a simple structure without complex operators, combining the efficiency of CNNs to model short-range dependencies and the dynamic modeling capabilities of Transformers to learn long-range interactions. Multiple comparative experiments show that a backbone constructed solely with IR-Blocks exhibits high efficiency and excellent feature extraction capabilities.

2.5. Complete IoU: More Efficient Regression Loss Function

Given the high-precision requirement for tree canopy segmentation tasks, the model’s output prediction masks need to closely match the tree canopies. Traditional loss functions primarily focus on the Intersection over Union (IoU [

24]) between the prediction mask and ground truth labels but fail to accurately reflect their overlap. The Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU [

25]) proposed by Hamid Rezatofighi, although introducing the minimum enclosing box as a penalty term to improve precision, still suffers from slow convergence. To address the issue of divergence during training with IoU [

24] and GIoU [

25], and to enhance the stability and regression performance of the model’s convergence, IRB-YOLO adopts Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU [

25]) as the loss function. The calculation formula related to CIoU [

25] can be expressed as eq7,eq8,eq9,eq10

4. Discussion

To achieve precise pesticide application on green plums, the spraying drone requires an optimal flight path, as shown in

Figure 10. The surveying drone acquires vertical images of the green plum tree canopies using a visible light sensor, for each image, it is fed into the instance segmentation model for inference, after obtaining the segmentation masks, the centroids are calculated and used as target waypoints, finally, the optimal pesticide spraying flight path is determined by applying a path planning algorithm to the target waypoints. The main dataset used in this experiment consists of Vatica images captured in the Vatica orchard located in Dongkeng Town, Luhhe County, Shanwei City, Guangdong Province (geographical coordinates: 114.03°E, 22.75°N). This dataset comprises 583 RGB images with a resolution of 5280×3956 pixels, obtained by a drone equipped with a visible light sensor. To enhance the model’s ability to capture and analyze canopy features at different flight altitudes, the drone flew along predefined routes at heights ranging from 47.113 meters to 124.092 meters, where each pixel represents a ground distance of 2.35 meters to 6.19 meters. To ensure that the dataset adequately represents the characteristics of Vatica, the data collection period was set from March to July, covering the entire lifecycle of the Vatica fruit from budding to maturity. Given the varying management conditions under which Vatica canopies exhibit diverse forms, this dataset particularly includes two representative types: densely unpruned natural growth and isolated pruned canopies, aimed at ensuring that the model learns the appearance characteristics of Vatica trees under different management conditions. In addition to the standard Vatica dataset, to validate the robustness of the model in cross-species applications, this study also incorporated data from two other tree species with similar morphological texture features to construct a mixed dataset. Data from these species were collected using the same drone and identical acquisition strategies as the Vatica dataset, maintaining consistent image resolution and sensor channels.

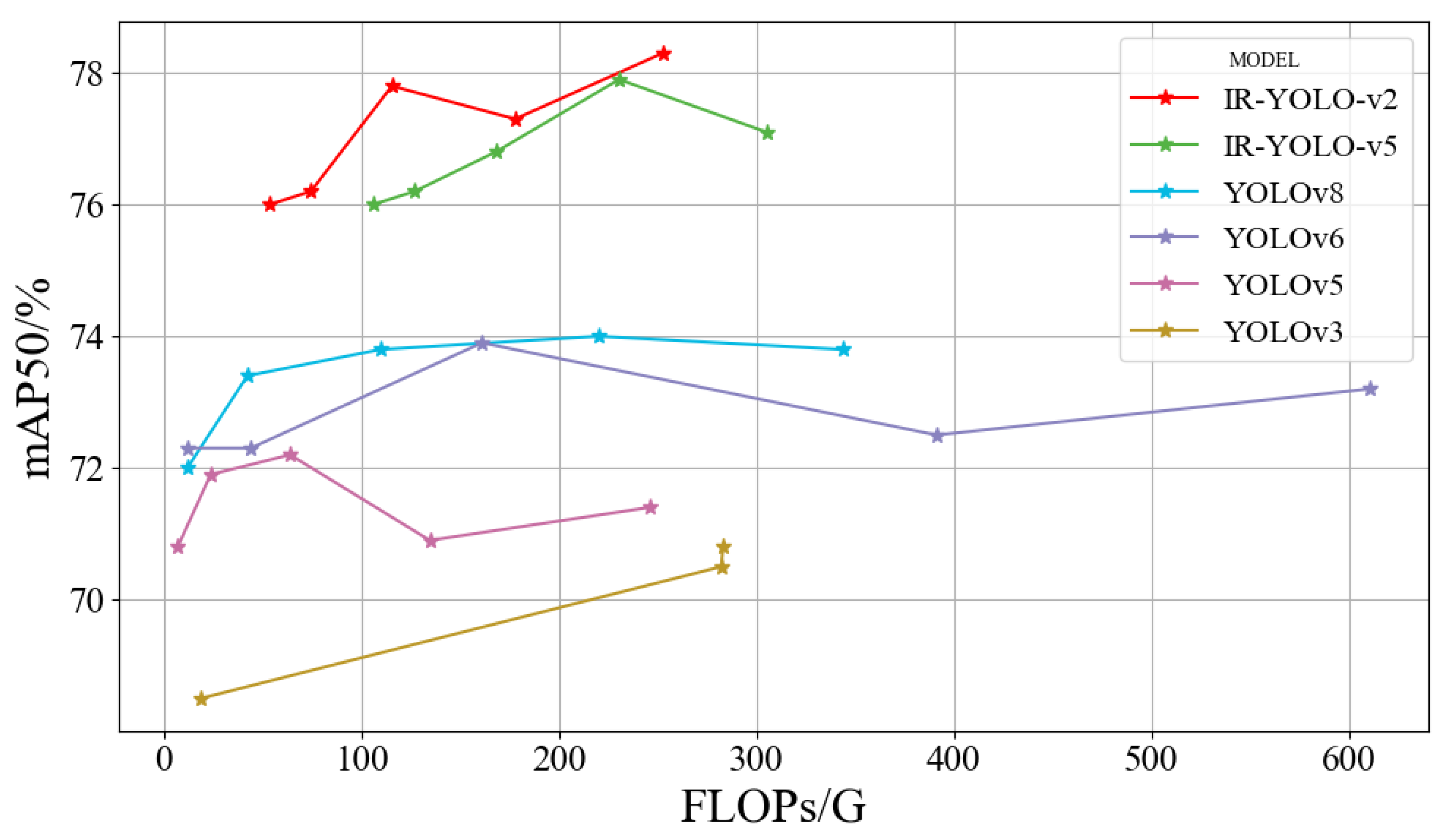

The experimental results demonstrate that a feature extraction module without complex operators can achieve satisfactory feature capture by modeling both long- and short-range dependencies; an inverted residual structure provides a rich feature space, serving as the foundation for effective feature extraction; thanks to the computational cost reduction brought about by the efficient component DW-Conv, the resource consumption resulting from the use of inverted residuals and attention mechanisms is controlled within acceptable limits, allowing the overall module to exhibit high performance. Since the introduction and application of ViT [

12] in computer vision in 2021, many researchers have been eager to incorporate attention mechanisms and Transformer blocks into their work, despite the fact that the accompanying increase in computational load is often overlooked, even though these models show improvements in accuracy. In practical applications, balancing model accuracy, size, and inference latency is crucial. When utilizing MHSA, which is computationally intensive, efficiency optimizations should be applied to other components to distribute the computational burden, thereby achieving an ideal balance between efficiency and accuracy.

Figure 1.

Technical roadmap and workflow. In the Donkeng Plum Garden(114.03°E,22.75°N), Shanwei, Guangdong, the DJI M300 RTK drone captured RGB images of Vatica trees at varying altitudes, with a resolution of 5280×3956 pixels. Flying heights ranged from 47.113m to 124.092m, averaging 94.058m. A single pixel corresponded to 2.35m-6.19m in reality. Trained models effectively segmented Vatica trees, providing a visual algorithmic base for geospatial mapping and agricultural operations, as illustrated by the IRB-YOLO deployment strategy in the figure.

Figure 1.

Technical roadmap and workflow. In the Donkeng Plum Garden(114.03°E,22.75°N), Shanwei, Guangdong, the DJI M300 RTK drone captured RGB images of Vatica trees at varying altitudes, with a resolution of 5280×3956 pixels. Flying heights ranged from 47.113m to 124.092m, averaging 94.058m. A single pixel corresponded to 2.35m-6.19m in reality. Trained models effectively segmented Vatica trees, providing a visual algorithmic base for geospatial mapping and agricultural operations, as illustrated by the IRB-YOLO deployment strategy in the figure.

Figure 2.

Comparison of inference results from different visual task models. Object detection models locate the center of the canopy using the geometric center of the bounding boxes; Semantic segmentation models treat all canopies of the same class as a single entity, requiring post-processing of the segmentation results to compute the centroid of each canopy object to locate the canopy center; Instance segmentation models segment each individual object, and their segmentation results can be directly used to calculate the centroid, thereby locating the canopy center.

Figure 2.

Comparison of inference results from different visual task models. Object detection models locate the center of the canopy using the geometric center of the bounding boxes; Semantic segmentation models treat all canopies of the same class as a single entity, requiring post-processing of the segmentation results to compute the centroid of each canopy object to locate the canopy center; Instance segmentation models segment each individual object, and their segmentation results can be directly used to calculate the centroid, thereby locating the canopy center.

Figure 3.

The dataset of experiments. Some different varieties of image from drones RGB sensor at different heights. (a) Untrimmed Vatica; (b) Untrimmed Pine; (c) Trimmed Vatica; (d) Trimmed Lychee Tree.

Figure 3.

The dataset of experiments. Some different varieties of image from drones RGB sensor at different heights. (a) Untrimmed Vatica; (b) Untrimmed Pine; (c) Trimmed Vatica; (d) Trimmed Lychee Tree.

Figure 4.

The architecture of IRB-YOLO. The network consists of three main parts: Backbone, Neck, and Head. Important components within the Backbone, Neck, and Head are listed in the figure.

Figure 4.

The architecture of IRB-YOLO. The network consists of three main parts: Backbone, Neck, and Head. Important components within the Backbone, Neck, and Head are listed in the figure.

Figure 5.

Comparison of several Transformer blocks and CNN blocks.

Figure 5.

Comparison of several Transformer blocks and CNN blocks.

Figure 6.

The detailed structure of the IR-Block.Including four components: Expand, Attention, Convolution, and Shrink.

Figure 6.

The detailed structure of the IR-Block.Including four components: Expand, Attention, Convolution, and Shrink.

Figure 7.

The device used for the above benchmark test has an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6240R CPU @ 2.40GHz with 100 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA Tesla A800 GPU graphics card with a VRAM of 80GB.

Figure 7.

The device used for the above benchmark test has an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6240R CPU @ 2.40GHz with 100 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA Tesla A800 GPU graphics card with a VRAM of 80GB.

Figure 8.

IRB-YOLO perform segmentation masks on images captured under different pruning conditions and species. (a) Untrimmed Vatica; (b) Untrimmed Pine; (c) Trimmed Vatica; (d) Trimmed Lychee Tree.

Figure 8.

IRB-YOLO perform segmentation masks on images captured under different pruning conditions and species. (a) Untrimmed Vatica; (b) Untrimmed Pine; (c) Trimmed Vatica; (d) Trimmed Lychee Tree.

Figure 9.

IRB-YOLO-v2 and YOLOv8-l perform heatmaps based on EigenCAM. Through the comparison of three identical Head layers extracted from two models, it is observed that from P3 to P5, the depth increases and the corresponding feature map resolutions gradually increase.

Figure 9.

IRB-YOLO-v2 and YOLOv8-l perform heatmaps based on EigenCAM. Through the comparison of three identical Head layers extracted from two models, it is observed that from P3 to P5, the depth increases and the corresponding feature map resolutions gradually increase.

Figure 10.

Flight path generation process. The drone uses a visible light sensor to acquire high-resolution images, and then inputs the images into the instance segmentation model for inference to obtain the segmentation masks; For each instance’s segmentation mask, calculate its centroid as the target waypoint; Finally, optimal pesticide spraying flight paths are planned based on all the target waypoints.

Figure 10.

Flight path generation process. The drone uses a visible light sensor to acquire high-resolution images, and then inputs the images into the instance segmentation model for inference to obtain the segmentation masks; For each instance’s segmentation mask, calculate its centroid as the target waypoint; Finally, optimal pesticide spraying flight paths are planned based on all the target waypoints.

Table 1.

The network structure parameters of different sizes for IRB-YOLO. The network primarily consists of Convolution Layers and Inverted Residual Blocks, and Fully Connected Layers. In stages 1-4, Inverted Residual Blocks are used, composed of combinations of one or multiple 1×1 convolution layers plus 3×3 convolution layers. This paper provides models of different computational costs, allowing users to adjust the number of convolution kernels in the Inverted Residual Blocks according to the needs of specific tasks.

Table 1.

The network structure parameters of different sizes for IRB-YOLO. The network primarily consists of Convolution Layers and Inverted Residual Blocks, and Fully Connected Layers. In stages 1-4, Inverted Residual Blocks are used, composed of combinations of one or multiple 1×1 convolution layers plus 3×3 convolution layers. This paper provides models of different computational costs, allowing users to adjust the number of convolution kernels in the Inverted Residual Blocks according to the needs of specific tasks.

Table 2.

Comparison with mainstream models.

Table 2.

Comparison with mainstream models.

| Model |

Param |

FLOPs |

Latency |

(Precision) |

(Recall) |

mAP50 |

| |

(/M) |

(/G) |

(/ms) |

(/%) |

(/%) |

(/%) |

| YOLOv3 [17] |

103.67 |

282.2 |

5.4 |

71.5 |

70.4 |

70.5 |

| YOLOv3-tiny [17] |

12.13 |

18.9 |

1.6 |

65.9 |

70.1 |

68.5 |

| YOLOv3-spp [17] |

104.71 |

283.1 |

7.0 |

66.0 |

73.4 |

70.8 |

| YOLOv5-m |

25.05 |

64.0 |

4.0 |

70.7 |

70.0 |

72.2 |

| YOLOv5-l |

53.13 |

134.7 |

5.1 |

72.5 |

67.6 |

70.9 |

| YOLOv6-m [26] |

51.98 |

161.1 |

4.7 |

71.5 |

71.8 |

73.9 |

| YOLOv6-l [26] |

110.86 |

391.2 |

7.0 |

69.5 |

71.5 |

72.5 |

| YOLOv8-m |

27.22 |

110.0 |

6.4 |

69.7 |

72.2 |

73.8 |

| YOLOv8-l |

45.91 |

220.1 |

6.8 |

71.6 |

70.6 |

74.0 |

| IRB-YOLO-v2 |

28.26 |

177.9 |

9.1 |

75.9 |

71.6 |

77.3 |

| IRB-YOLO-v5 |

31.05 |

230.5 |

8.5 |

75.3 |

73.0 |

77.9 |

Table 3.

Ablation Experiment.

Table 3.

Ablation Experiment.

| Strategies |

Param |

FLOPs |

Precision |

mAP50 |

| |

(/M) |

(/G) |

(/ms) |

(/%) |

| Backbone–YOLOv8-l |

45.91 |

220.1 |

71.6 |

74.0 |

| Backbone–IRB-YOLO |

31.05 |

230.5 |

70.3 |

76.7 |

| Backbone–IRB-YOLO and CIoU |

31.05 |

230.5 |

75.3 |

77.9 |