Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Design & Methods

Basic Framework

3. Results

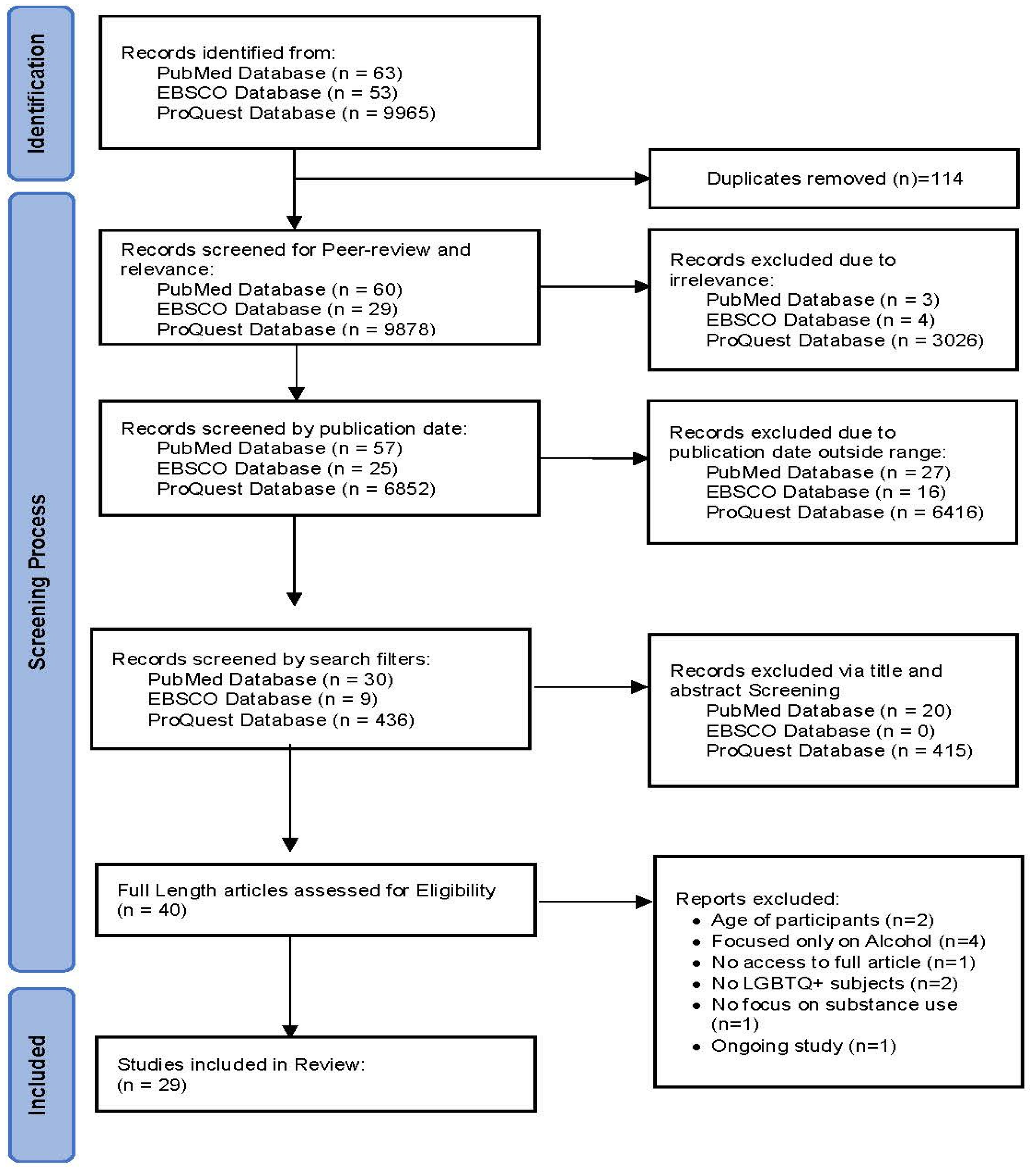

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Studies Characteristics

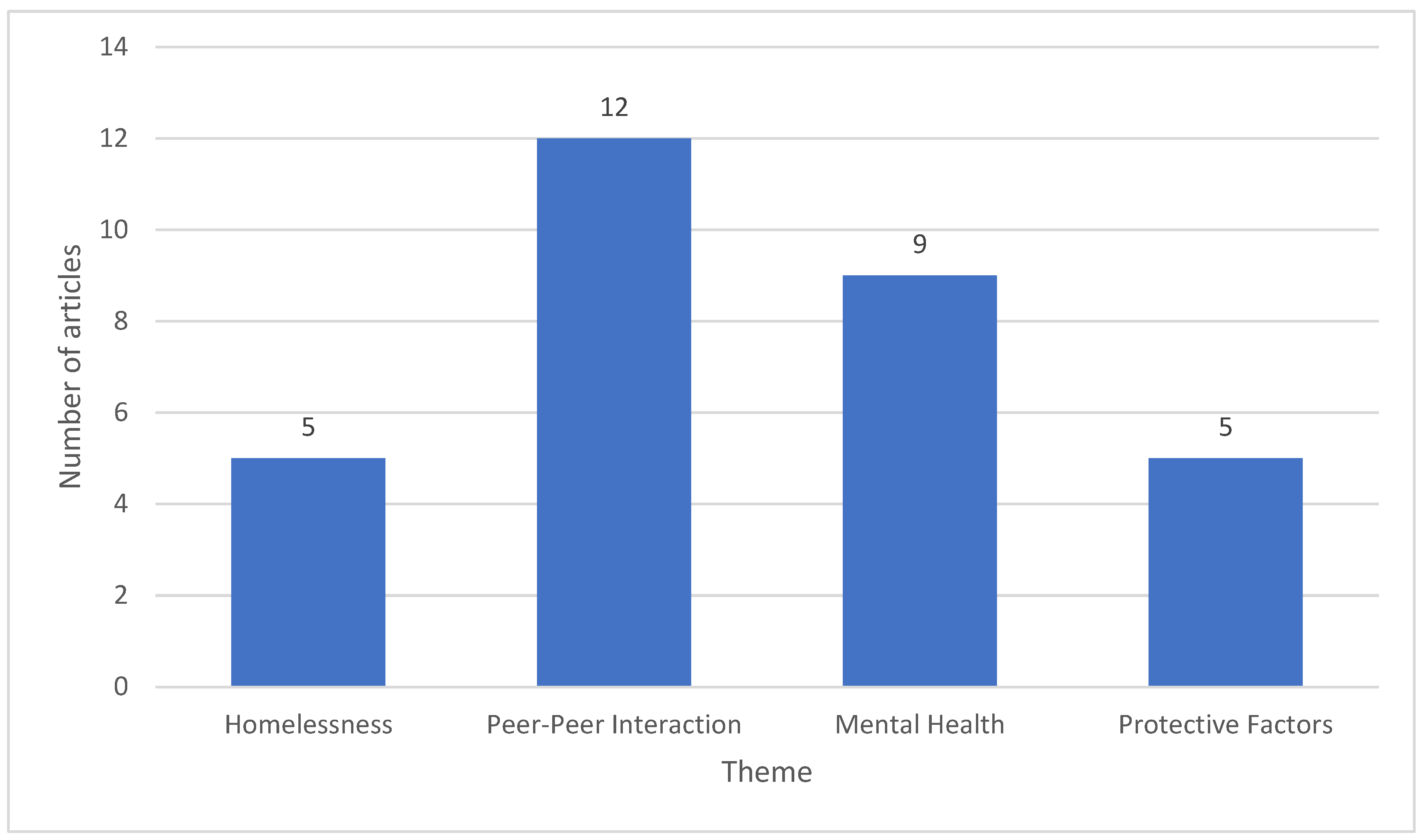

3.2.1. Homelessness

3.2.2. Peer-Peer Interactions

3.2.3. Mental Health

3.2.4. Protective Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

References

- Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. [CrossRef]

- Arrington-Sanders, R., Hailey-Fair, K., Wirtz, A. L., Cos, T., Galai, N., Brooks, D., Castillo, M., Dowshen, N., Trexler, C., D’Angelo, L. J., Kwait, J., Beyrer, C., Morgan, A., Celentano, D. D., & Study, P. (2020). Providing unique support for health Study among young Black and Latinx men who have sex with men and young Black and Latinx transgender women living in 3 urban cities in the United States: Protocol for a Coach-Based Mobile-Enhanced Randomized Control Trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(9), e17269. [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2023, June 30). Illicit Drug Use. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/illicit-drug-use.

- Bochicchio, L., Reeder, K., Ivanoff, A., Pope, H., & Stefancic, A. (2022). Psychotherapeutic interventions for LGBTQ + youth: a systematic review. Journal of Lgbt Youth, 19(2), 152–179. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE.

- Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:2, 77-101, DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [CrossRef]

- Bremond, P. (2022). World Drug Report 2022. Dianova. https://www.dianova.org/news/world-drug-report-2022/#:~:text=suggests%20possible%20responses.-,Current%20trends,part%20to%20global%20population%20growth.

- Cartwright, W. S. (2008). Economic costs of drug abuse: Financial, cost of illness, and services. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(2), 224–233. [CrossRef]

- Crews, F. T., He, J., & Hodge, C. W. (2007). Adolescent cortical development: A critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 86(2), 189–199. [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, J., & Curry, T. R. (2007). The prevalence and comorbidity between delinquency, drug abuse, suicide attempts, physical and sexual abuse, and Self-Mutilation among delinquent Hispanic females. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 29(1), 68–82. [CrossRef]

- Cutuli, J. J., Treglia, D., & Herbers, J. E. (2020). Adolescent homelessness and associated features: prevalence and risk across eight states. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(1), 48–58. [CrossRef]

- Damian, A. J., Ponce, D., Ortiz-Siberon, A., Kokan, Z., Curran, R., Azevedo, B., & Gonzalez, M. L. (2022). Understanding the Health and Health-Related Social Needs of Youth Experiencing Homelessness: A Photovoice study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9799. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G. C., Hall, W., & Lynskey, M. T. (2016). The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), 251–264. [CrossRef]

- D’Orsogna, M. R., Böttcher, L., & Chou, T. (2023). Fentanyl-driven acceleration of racial, gender and geographical disparities in drug overdose deaths in the United States. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(3), e0000769. [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, E. A., Nace, A., Hirshfield, S., & Birnbaum, J. M. (2019). Young transgender women of color: homelessness, poverty, childhood sexual abuse and implications for HIV care. Aids and Behavior, 25(S1), 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M. E., Erickson, D. J., Gower, A. L., Kne, L., Watson, R. J., Corliss, H. L., & Saewyc, E. (2020). Supportive Community Resources Are Associated with Lower Risk of Substance Use among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning Adolescents in Minnesota. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 836–848. [CrossRef]

- Ewald, H., Klerings, I., Wagner, G., Heise, T. L., Stratil, J. M., Lhachimi, S. K., Hemkens, L. G., Gartlehner, G., Armijo-Olivo, S., & Nussbaumer-Streit, B. (2022). Searching two or more databases decreased the risk of missing relevant studies: a metaresearch study. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 149, 154–164. [CrossRef]

- Filia, K., Menssink, J. M., Gao, C. X., Rickwood, D., Hamilton, M., Hetrick, S., Parker, A. G., Herrman, H., Hickie, I. B., Sharmin, S., McGorry, P. D., & Cotton, S. (2022). Social inclusion, intersectionality, and profiles of vulnerable groups of young people seeking mental health support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(2), 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B., Pierse, N., Chisholm, E., & Cook, H. (2019). LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A review of the literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2677. [CrossRef]

- Goldbach, J. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Bagwell, M., & Dunlap, S. (2014). Minority Stress and Substance Use in Sexual Minority Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K. W., Lindley, L. L., Russell, E., Mudd, T., Williams, C., & Botvin, G. J. (2022). Sexual Violence and Substance Use among First-Year University Women: Differences by Sexual Minority Status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10100. [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, M., Jin, F., Maher, L., Bourne, A., Haire, B., Saxton, P., Vaccher, S., Lea, T., Degenhardt, L., & Prestage, G. (2020). Biomedical HIV protection among gay and bisexual men who use crystal methamphetamine. Aids and Behavior, 24(5), 1400–1413. [CrossRef]

- Hatchel, T., Ingram, K. M., Mintz, S., Hartley, C., Valido, A., Espelage, D. L., & Wyman, P. A. (2019). Predictors of Suicidal Ideation and Attempts among LGBTQ Adolescents: The Roles of Help-seeking Beliefs, Peer Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Drug Use. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2443–2455. [CrossRef]

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Sarda, V., Austin, S. B., & Harris, S. K. (2021). Longitudinal effects of gender minority stressors on substance use and related risk and protective factors among gender minority adolescents. PLOS ONE, 16(6), e0250500. [CrossRef]

- Költő, A., Cosma, A., Young, H., Moreau, N., Pavlova, D., Tesler, R., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Vieno, A., Saewyc, E., & Gabhainn, S. N. (2019). Romantic Attraction and Substance Use in 15-Year-Old Adolescents from Eight European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3063. [CrossRef]

- Loi, N. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Rice, K., & Rock, A. J. (2022). Illicit drug use in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Health, 12. [CrossRef]

- Luikinga, S. J., Kim, J. H., & Perry, C. (2018). Developmental perspectives on methamphetamine abuse: Exploring adolescent vulnerabilities on brain and behavior. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 87, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Maria, D. S., Daundasekara, S. S., Hernandez, D. C., Zhang, W., & Narendorf, S. C. (2020). Sexual risk classes among youth experiencing homelessness: Relation to childhood adversities, current mental symptoms, substance use, and HIV testing. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0227331. [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M. P., Friedman, M., Stall, R., King, K. M., Miles, J. C., Gold, M. A., Bukstein, O. G., & Morse, J. Q. (2008). Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction, 103(4), 546–556. [CrossRef]

- Metheny, N., Stephenson, R., Darbes, L. A., Chavanduka, T., Essack, Z., & Van Rooyen, H. (2022). Correlates of Substance Misuse, Transactional Sex, and Depressive Symptomatology Among Partnered Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in South Africa and Namibia. Aids and Behavior, 26(6), 2003–2014. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol, 62(10), 1006-1012. [CrossRef]

- Nawi, A. M., Ismail, R., Ibrahim, F., Hassan, M. R., Manaf, M. R. A., Amit, N., Ibrahim, N., & Shafurdin, N. S. (2021). Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Noble, A., Owens, B., Thulien, N., & Suleiman, A. (2022). “I feel like I’m in a revolving door, and COVID has made it spin a lot faster”: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Canada. PLOS ONE, 17(8), e0273502. [CrossRef]

- O’Donohue, W., Carlson, G., Benuto, L., & Bennett, N. (2014). Rape Trauma syndrome. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 21(6), 858–876. [CrossRef]

- Ong, C., Tan, R. K. J., Le, D., Tan, A., Tyler, A., Tan, C., Kwok, C., Banerjee, S., & Wong, M. L. (2021). Association between sexual orientation acceptance and suicidal ideation, substance use, and internalised homophobia amongst the pink carpet Y cohort study of young gay, bisexual, and queer men in Singapore. BMC Public Health, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Soares, C., & Parker, D. (2017). 2017 Guidance for the Conduct of JBI Scoping Reviews. In.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Trico, A., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Pike, I., Kraus-Perrotta, C., & Ngo, T. D. (2023). A scoping review of survey research with gender minority adolescents and youth in low and middle-income countries. PLOS ONE, 18(1), e0279359. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. A. (2020). Coming Out to the Streets: LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520299276/coming-out-to-the-streets.

- Ryan, C., Huebner, D. M., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Scheer, J. R., & Mereish, E. H. (2021). Intimate Partner violence and illicit substance use among sexual and gender minority youth: The Protective Role of Cognitive Reappraisal. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 9956–9976. [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M. S., Prince, D. M., Breslau, J., & Collins, R. L. (2020). Substance Use Disparities at the Intersection of Sexual Identity and Race/Ethnicity: Results from the 2015–2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. LGBT Health, 7(6), 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M. S., Stein, B. D., & Collins, R. L. (2019). Differences in substance use disparities across age groups in a national Cross-Sectional Survey of Lesbian, gay, and Bisexual adults. LGBT Health, 6(2), 68–76. [CrossRef]

- Seekaew, P., Lujintanon, S., Pongtriang, P., Nonnoi, S., Hongchookait, P., Tongmuang, S., Srisutat, Y., & Phanuphak, P. (2019). Sexual patterns and practices among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand: A qualitative assessment. PLOS ONE, 14(6), e0219169. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Kahle, E., Todd, K., Peitzmeier, S., & Stephenson, R. (2019). Variations in testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections across gender identity among transgender youth. Transgender Health, 4(1), 46–57. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). The Development of Coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 119–144. [CrossRef]

- Soares, F., Magno, L., Filho, M. E., Duarte, F. M., Grangeiro, A., Greco, D. B., & Dourado, I. (2023). Important steps for PrEP uptake among adolescent men who have sex with men and transgender women in Brazil. PLOS ONE, 18(4), e0281654. [CrossRef]

- Thi, L. A., Voelker, M., Kanchanachitra, C., Boonmongkon, P., Ojanen, T. T., Samoh, N., & Guadamuz, T. E. (2020). Social violence among Thai gender role conforming and non-conforming secondary school students: Types, prevalence and correlates. PLOS ONE, 15(8), e0237707. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. (2022). World Drug Report 2022. United Nations. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html.

- Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Breiding, M. J. (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation [Dataset]. In PsycEXTRA Dataset. [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. J., Fish, J. N., McKay, T., Allen, S. H., Eaton, L. A., & Puhl, R. M. (2020). Substance use among a national sample of sexual and gender minority adolescents: intersections of sex assigned at birth and gender identity. LGBT Health, 7(1), 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Whitton, S. W., Dyar, C., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2018a). Effects of romantic involvement on substance use among young sexual and gender minorities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Whitton, S. W., Dyar, C., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2018b). Effects of romantic involvement on substance use among young sexual and gender minorities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Wichaidit, W., Assanangkornchai, S., & Chongsuvivatwong, V. (2021). Disparities in behavioral health and experience of violence between cisgender and transgender Thai adolescents. PLOS ONE, 16(5), e0252520. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2019, November 26). Adolescent health. www.who.int. Retrieved August 19, 2023, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1.

- Yockey, R. A., & Barnett, T. E. (2023). Past-Year Blunt Smoking among Youth: Differences by LGBT and Non-LGBT Identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5304. [CrossRef]

| # |

Author Year & Country |

Article Title |

Population (n) Age range |

Aims/Parameters Examined | Study Design/Key Findings |

| 1 | Arrington-Sanders et al, 2020. USA. |

Providing unique support for health study among Young Black and Latinz Men who have sex with Men and Young Black and Latinx Transgender Women living in 3 urban Cities in the USA: Protocol for a Coach-Based Mobile-Enhanced Randomized Control Trial. | Young Black and Latinx men who have sex with men, and transgender women. Ages 15-24 years. N=402 participants. |

To assess mobile enhanced interventions compared to standard care, to increase engagement and retention into HIV, PrEP and Substance use treatment care. |

|

| 2 | Bochicchio et al, 2022. USA. |

Psychotherapeutic interventions for LGBTQ+ youth: a systematic review. | LGBTQ+ adolescents. Age range: 14-22 years old (yo). (n) = 10 articles (n=822) that ranged from 10-268 participants. |

Psychotherapeutic interventions for LGBT+ adolescents with mental illness and substance abuse. |

|

| 3 | Cutuli et al, 2020. USA. |

Adolescent Homelessness and Associated Features: Prevalence and Risk Across Eight States. | LGBTQ+ youth from 14-18 yo in specific states in the USA. N=77,559. |

To test for positive associations between homelessness and key indicators. |

|

| 4 | Damian et al,2022. USA. |

Understanding the Health and Health-Related Social Needs of Youth Experiencing Homelessness: A photovoice Study. | LGBTQ+ youths (14-24 yo) experiencing homelessness during COVID-19 pandemic in Connecticut. N=14. |

Record homeless youth everyday reality. | Participant described vicious cycle of alcohol and substance use which made housing insecurity worse. |

| 5 | Do et al, 2020. Thailand. |

Social Violence Among Thai gender role conforming and non-conforming secondary school students: Types, prevalence, and correlates. | Secondary school students who are trans or same sex attracted. Age 13-20 yo. N=2070. |

Substance use was found in 98 (4.8%) participants and included: cannabis, amphetamine pills, crystal methamphetamine, ecstasy/MDMA, sleeping pills and injection drug use. | |

| 6 | Eastwood et al, 2021. USA. |

Young Transgender Women of Colour: Homelessness, Poverty, Childhood Sexual Abuse and Implications for HIV Care. | HIV+ young (18-24 yo) transgender women of colour. N=102. |

To engage and retain transgender women of colour with HIV in care to manage viral load suppression and determine factors contributing to sustained health care. | 15.6% of participants reported drug dependence. |

| 7 | Eisenberg et al, 2020. USA. |

Supportive Community Resources Are Associated with Lower Risk of Substance Use among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning Adolescents in Minnesota. | LGBQ high school students. N=2454. |

To examine stigma and support and their association with substance use in LGBQ youth. |

|

| 8 | Filia et al, 2022. AUS/NZ. |

Social inclusion, intersectionality, and profiles of vulnerable groups of young people seeking mental health support. | Young people 12-25 yo presenting to a Headspace Centre for mental health +/- substance use related issues. Age range 12-25 yo. N=1107. |

To examine social inclusion across specific domains of housing, employment, study, alcohol and other drugs. |

|

| 9 | Fraser et al, 2019. NZ. |

LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of Literature. | “LGBT Homelessness” “Queer Homelessness” “LGBT Housing First” essentially LGBTIQ+ homelessness. N=53 articles. |

To examine the intersecting factors associated with homelessness and LGBTIQ+ homelessness. |

|

| 10 | Griffin et al, 2022. USA. |

Sexual Violence and Substance Use among First-Year University Women: Differences by Sexual Minority Status. | 1st year university women from 14 USA Universities. N =974. Mean age 19.1. |

To examine the rates of sexual violence, perpetration and substance use seen in first year university women. |

|

| 11 | Hammoud et al, 2020. AUS. |

Biomedical HIV Protection Among Gay and Bisexual Men Who Use Crystal Methamphetamine. | Gay/Bisexual men >16 yo who’ve had sex with another man in the last 12 months and lived in Australia. Median age 35 (16-81 yo). N=1367. |

To investigate the relationship between crystal use and HIV risk behaviours in relation to biomedical prevention. |

|

| 12 | Hatchel et al, 2019. USA. |

Predictors of Suicidal Ideation and Attempts among LGBTQ Adolescents: The Roles of Help-seeking Beliefs, Peer Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Drug Use. | LGBTQ+ high school students participating in randomised clinical trial testing the effects of sources of strengths. Mean age=15 yo. N=713 (LGBTQ). |

To examine whether peer victimization, drug use, depressive symptoms, and help-seeking beliefs predict suicidal ideation/attempts among LGBTQ adolescents. |

|

|

13 |

Ksatz-Wise et al, 2021. USA. |

Longitudinal effects of gender minority stressors on substance use and related risk and protective factors among gender minority adolescents. |

Gender minority adolescents in the US from the Trans Teen and Family Narratives (TTFN) project. Ages 13-17 yo. N=30. |

To determine the effects of minority stressors (gender) on substance use among gender minority adolescents and the related risk/protective factors. |

|

| 14 | Költö et al, 2019. Europe. |

Romantic Attraction and Substance Use in 15-Year-Old Adolescents from Eight European Countries. | Same- and both-gender attracted 15 yo adolescents from different European countries. Ave Age = 15.55. N=14,545. |

To explore the association between being of sexual minority and different substance use behaviours. |

|

| 15 | Maria et al, 2020. USA. |

Sexual risk classes among youth experiencing homelessness: Relation to childhood adversities, current mental symptoms, substance use, and HIV testing. | Youth between the ages of 13-24yo that were homeless or had unstable housing. Age 13-24 yo. N=416 (final analysis). |

To determine if different subgroups of youth with different types of sexual risk behaviours experience homelessness and to examine the associations between potential classes and other variables. |

|

| 16 | Metheny et al, 2022. South Africa. |

Correlates of Substance Misuse, Transactional Sex, and Depressive Symptomatology Among Partnered Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in South Africa and Namibia. | Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in South Africa and Nambia. Age 18-24. N=152. |

To assess the association between 3 major HIV risk factors in Gay/Bisexual men in Southern Africa. |

|

| 17 | Noble Aet al, 2022. Canada. |

“I feel like I’m in a revolving door, and COVID has made it spin a lot faster”: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Canada. | Youth Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto, Ontario Canada. With some focus on particular sub-groups; mainly 2SLGBTQ, black youth and newcomer youth. Age= 16-24 N=45 youth N=31 staff members N=9 2SLGBTQ (20%) |

To appraise the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness. |

|

| 18 | Ong et al, 2021. Singapore. |

Association between sexual orientation acceptance and suicidal ideation, substance use, and internalised homophobia amongst the pink carpet Y cohort study of young gay, bisexual, and queer men in Singapore. | Gay/Bi/Questioning men that live within Singapore that are either HIV-negative or unsure about their HIV status. Age 18-25 yo (mean 21.9). N=564. |

To explore the associations between delayed acceptance of sexual orientation and the health specific outcomes relating to gay/bi/questioning men in Singapore. |

|

| 19 | Pike et al, 2023. USA. |

A scoping review of survey research with gender minority adolescents and youth in low and middle-income countries. | Peer-reviewed articles published in English that utilize surveying data to explore gender minority youth experiences. N=33 articles analysis. |

To explore the different ways studied in the experience of gender minority youth. |

|

| 20 | Scheer Jet al, 2021. USA. |

Intimate Partner Violence and Illicit Substance Use Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth: The Protective Role of Cognitive Reappraisal. | Self-identified sexual and gender minority youths between ages 18-25. N=149. Ages 18-25 yo. |

To examine cognitive reappraisal as a moderator to the various forms of intimate partner violence and illicit substance use among sexual and gender minority youths. |

|

| 21 | Schuler et al, 2019. USA. |

Differences in substance use disparities across age groups in a national cross-sectional survey of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults. | LGB adults of different age groups (18-25, 26-34, 35-49). N=76354, LGBTQ+=4868. |

To examine LGB disparities and recent substance use in different age groups and compare these to their heterosexual counterparts. |

|

| 22 | Schuler et al, 2020. USA. |

Substance Use Disparities at the Intersection of Sexual Identity and Race/Ethnicity: Results from the 2015-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. | LGB adults of different ages groups and races/ethnicities from the 2015-2016 NSDUH. (n)=168560; LGB=11389. |

To examine the differences in the presence and magnitude of substance use disparities in LGB adults across different races/ethnicities. |

|

| 23 | Seekaew et al, 2019. Thailand. |

Sexual patterns and practices among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand: A qualitative assessment. | Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women, living in Bangkok, Thailand that are over 18 yo. N=12MSM N=13TGW Median Age MSM=33.1 (29.9-35.7) TGW=25.8 (23.4-29.1) |

To understand the diversity of men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand and to identify sexual patterns and themes of men who have sex with men in Bangkok. |

|

| 24 | Sharma et al, 2019. USA. |

Variations in Testing for HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections Across Gender Identity Among Transgender Youth. | Individuals between 15-24 yo currently living in USA, that identify as non-cisgender and have never been diagnosed with HIV, but willing to conduct a rapid home HIV test. N=186 Age range 15-24 yo |

To quantify HIV and other STI testing levels and examine the variations in testing levels across three categories of gender identity: transgender men, transgender women and nonbinary individuals. | 71.5% of participants admitted that they use drugs. |

| 25 | Soares et al, 2023. Brazil. |

Important steps for PrEP uptake among adolescent men who have sex with men and transgender women in Brazil. | Participants were between the ages of 15-19yo and lived within testing city. Age 15-19. N=751. |

The aim of this study was to analyse the factors associated with drug use among adolescent men who have sex with men and transgender women in Brazil. | 31.5% of participants reported drinking alcohol, and 32.5% reported using drugs. |

| 26 | Watson R et al, 2020. USA. |

Substance Use among a National Sample of Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents: Intersections of Sex Assigned at Birth and Gender Identity. | Participants aged between 13-17yo, self-identified as sexual or gender minority and reside in the US. N=11,129. Age range 15-17 yo. |

The aim of this study was to test whether current gender identity and sex at birth were key factors in substance use among a large sample. |

|

| 27 | Whitton et al, 2018. USA. |

Effects of romantic involvement on substance use among young sexual and gender minorities. | Gender minority youth, living in Chicago. N=248. Age range 16-20 yo. |

The aim of this study was to identify protective factors that decreased the risk of substance use among sexual and gender minority adolescents. |

|

| 28 | Wichaidit et al, 2021. Thailand. |

Disparities in behavioural health and experiences of violence between cisgender and transgender Thai adolescents. | Data from The National School Survey on Alcohol Consumption, Substance Use and Other Health-Risk Behaviours (cross-sectional survey) The participants were then stratified based on sex at birth and their gender identity. N=31898. |

The objective of this study was to assess the extent of behavioural health outcomes and violence among respondents of the National School Survey on Alcohol Consumption, Substance Use and Other Health-Risk Behaviours. |

|

| 29 | Yockey R and Barnett T, 2023. USA. |

Past-Year Blunt Smoking among Youth: Differences by LGBT and Non-LGBT Identity. | LGBT+ youth. Age range 14-17 yo. N=7518. |

The aim of this study was to investigate the past year’s marijuana and tobacco use among a national sample of adolescents and compare the difference between LGBT+ youth versus non-LGBT youth. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).