Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

18 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Tag-SNPs Selection and Genotype Analysis

2.3. Personality Dimensions and Psychopathological Symptoms

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

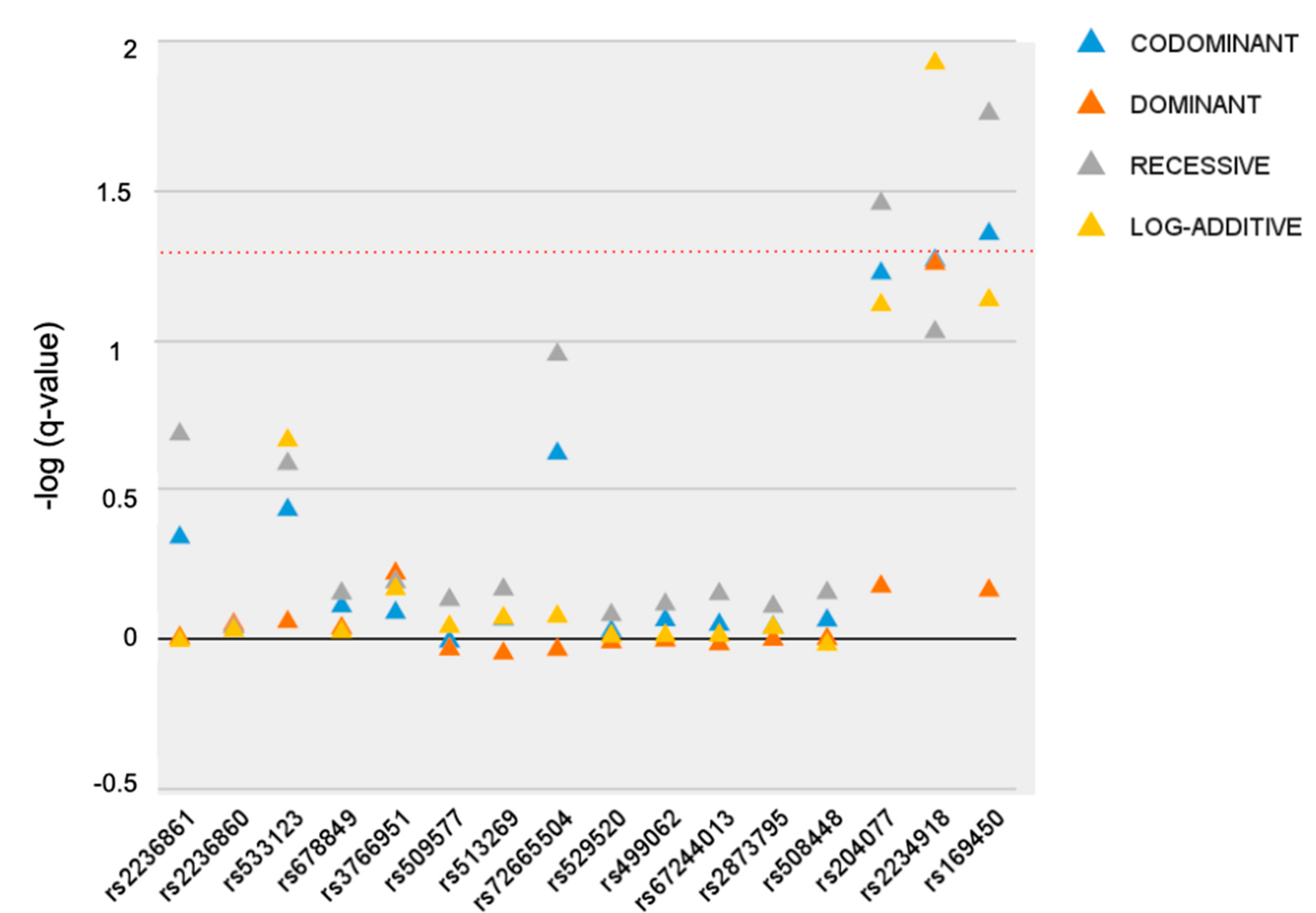

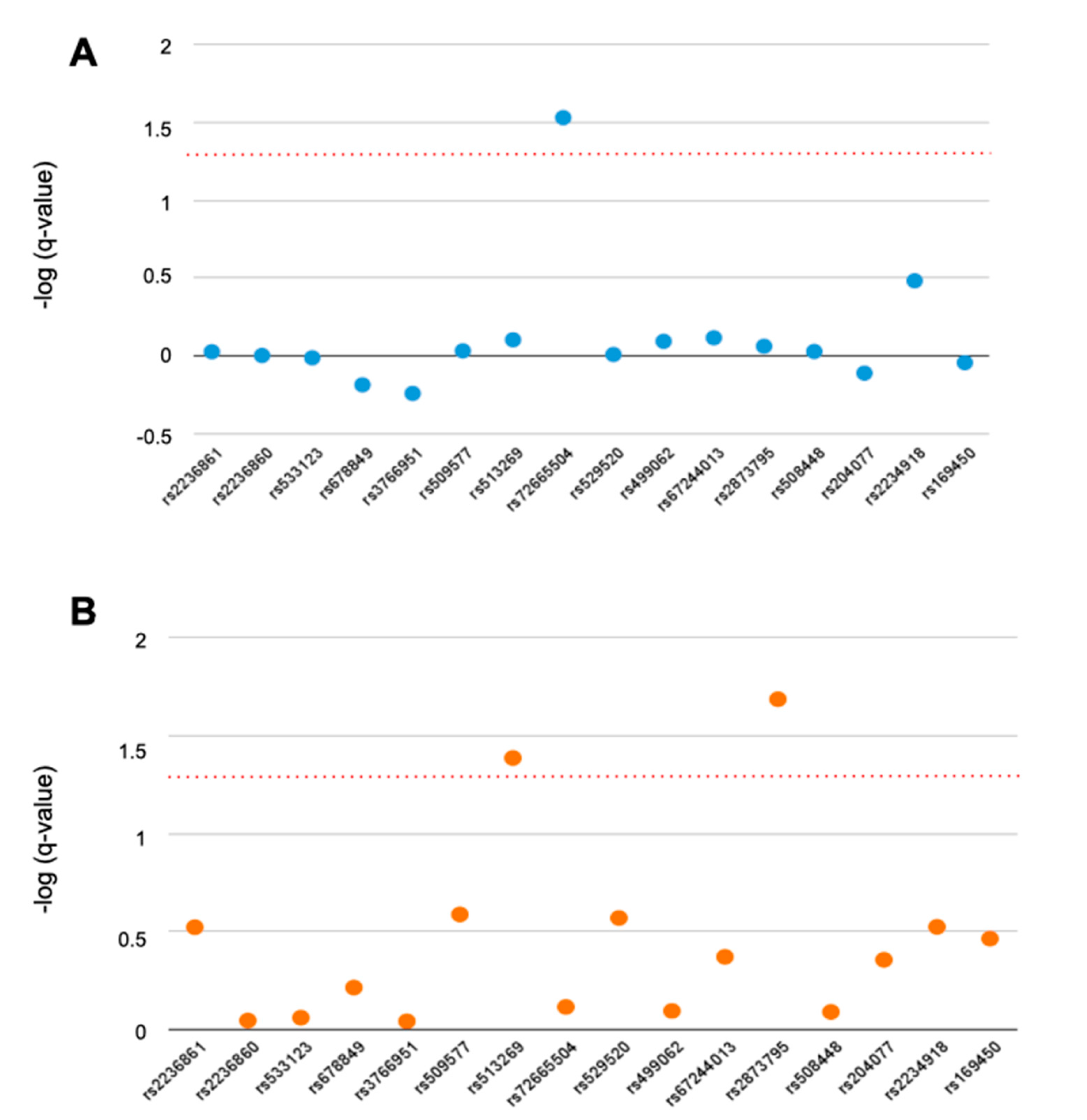

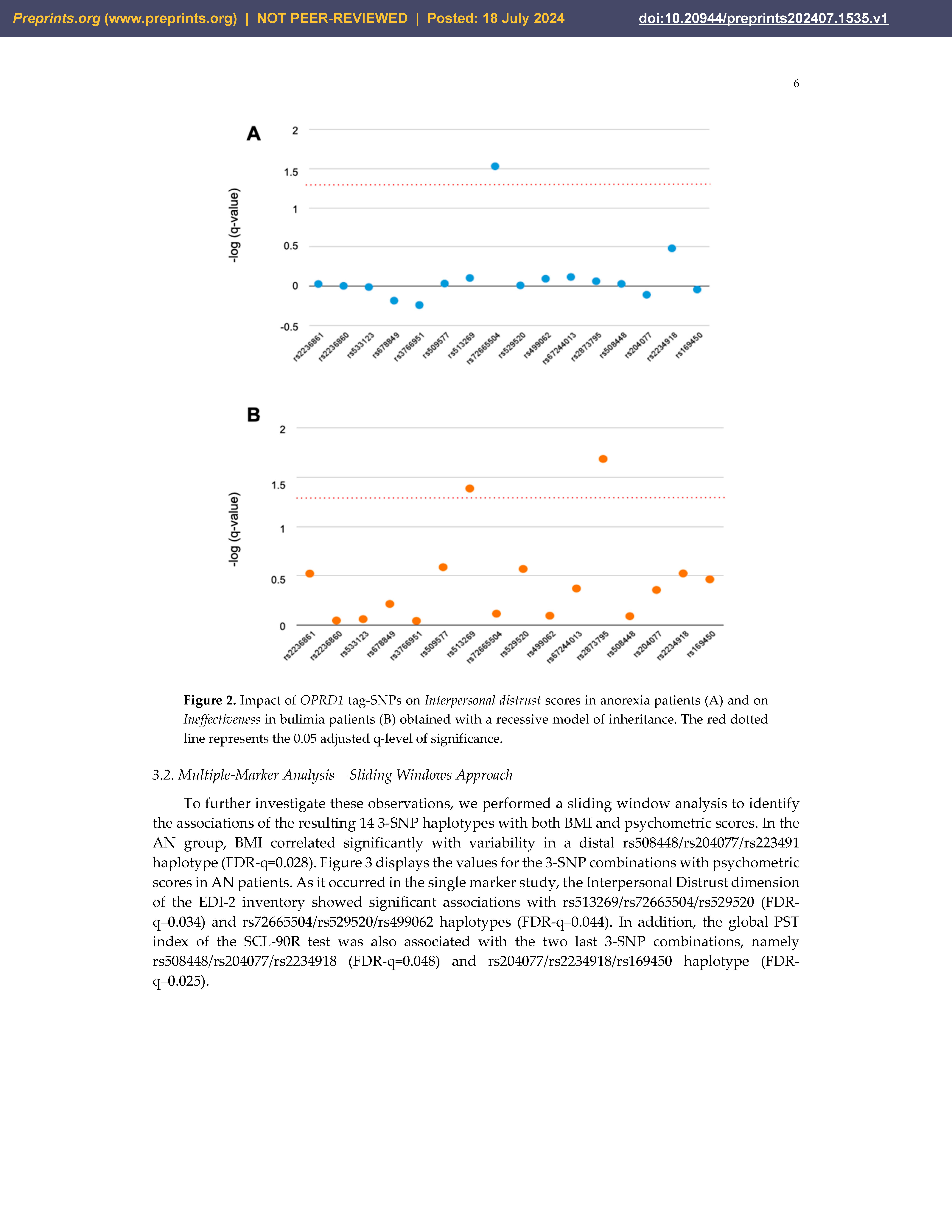

3.1. Single-Marker Analysis

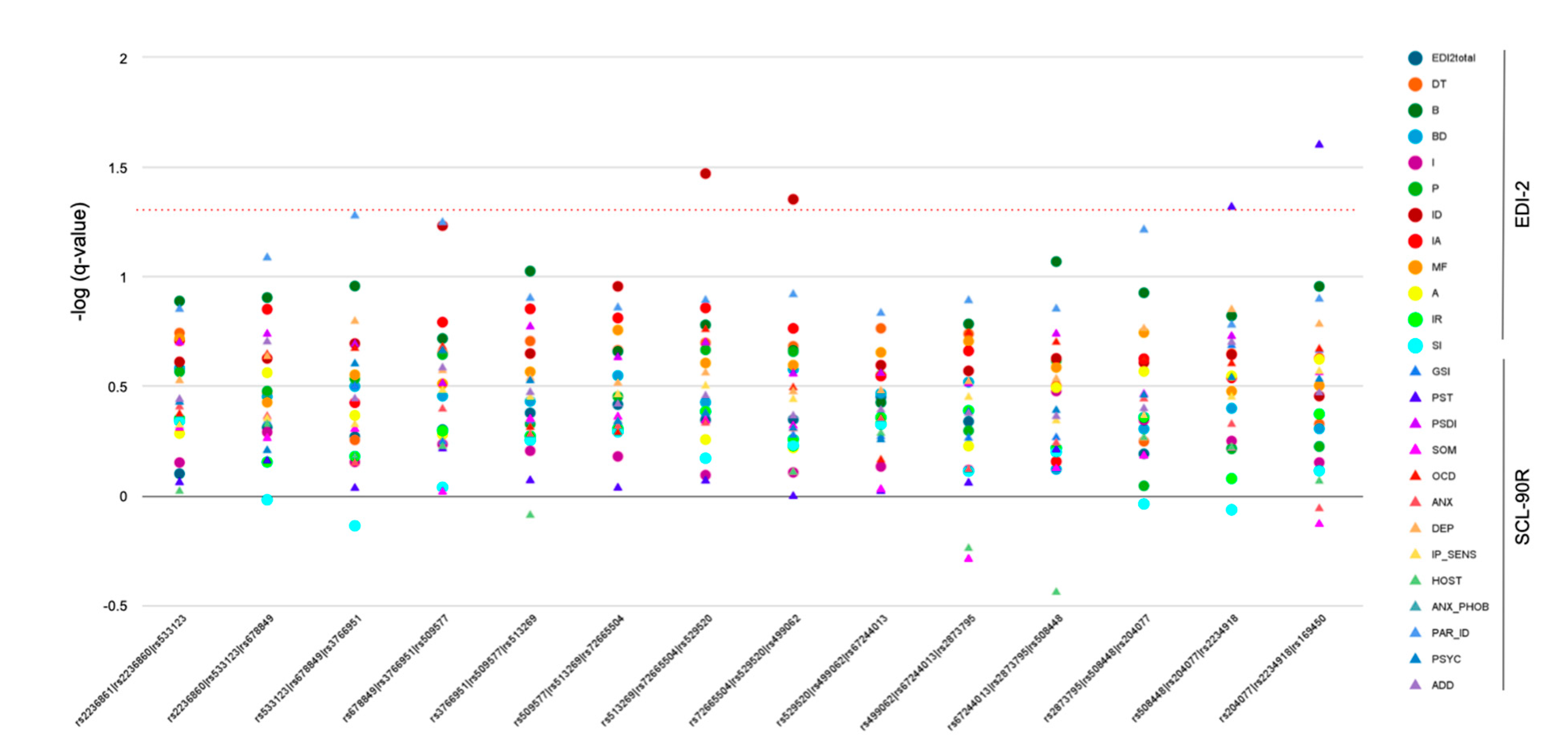

3.2. Multiple-Marker Analysis—Sliding Windows Approach

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bulik, C.M., J. R.I. Coleman, J.A. Hardaway, et al., Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders. Nat Neurosci, 2022. 25(5): 543-554. [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, S.S., M. R. Flores, A. Albu, Role of Endogenous Opioids in the Pathophysiology of Obesity and Eating Disorders. Adv Neurobiol, 2024. 35: 329-356. [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.R. and S.S. Zuniga, Endogenous Opioids in the Homeostatic Regulation of Hunger, Satiety, and Hedonic Eating: Neurobiological Foundations. Adv Neurobiol, 2024. 35: 315-327. [CrossRef]

- Galusca, B., B. Traverse, N. Costes, et al., Decreased cerebral opioid receptors availability related to hormonal and psychometric profile in restrictive-type anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2020. 118: 104711. [CrossRef]

- Roden, R.C., M. Billman, S. Lane-Loney, et al., An experimental protocol for a double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of the effectiveness of oral naltrexone in management of adolescent eating disorders. Contemp Clin Trials, 2022. 122: 106937. [CrossRef]

- Marrazzi, M.A. and E.D. Luby, An auto-addiction opioid model of chronic anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord, 1986. 5(2): 191-208.

- Kaye, W.H., L. R. Lilenfeld, W.H. Berrettini, et al., A search for susceptibility loci for anorexia nervosa: methods and sample description. Biol Psychiatry, 2000. 47(9): 794-803. [CrossRef]

- Grice, D.E., K. A. Halmi, M.M. Fichter, et al., Evidence for a susceptibility gene for anorexia nervosa on chromosome 1. Am J Hum Genet, 2002. 70(3): 787-92. [CrossRef]

- Bergen, A.W., M. B. van den Bree, M. Yeager, et al., Candidate genes for anorexia nervosa in the 1p33-36 linkage region: serotonin 1D and delta opioid receptor loci exhibit significant association to anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry, 2003. 8(4): 397-406. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., H. Zhang, C.S. Bloss, et al., A genome-wide association study on common SNPs and rare CNVs in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry, 2011. 16(9): 949-59. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.M., S. R. Bujac, E.T. Mann, D.A. Campbell, M.J. Stubbins, J.E. Blundell, Further evidence of association of OPRD1 & HTR1D polymorphisms with susceptibility to anorexia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry, 2007. 61(3): 367-73. [CrossRef]

- Boraska, V., C. S. Franklin, J.A. Floyd, et al., A genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry, 2014. 19(10): 1085-94. [CrossRef]

- Lilenfeld, L.R., S. Wonderlich, L.P. Riso, R. Crosby, J. Mitchell, Eating disorders and personality: a methodological and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev, 2006. 26(3): 299-320. [CrossRef]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A. and L. Mustelin, Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2016. 29(6): 340-5. [CrossRef]

- Bang, L., S. Bahrami, G. Hindley, et al., Genome-wide analysis of anorexia nervosa and major psychiatric disorders and related traits reveals genetic overlap and identifies novel risk loci for anorexia nervosa. Transl Psychiatry, 2023. 13(1): 291. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.M., A. Garcia-Herraiz, S. Mota-Zamorano, I. Flores, D. Albuquerque, G. Gervasini, Variability in cannabinoid receptor genes is associated with psychiatric comorbidities in anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord, 2021. 26(8): 2597-2606. [CrossRef]

- Derogaitis, L.R. , SCL-90R: Cuestionario de 90 síntomas. 2002, Madrid: TEA Ed.

- Guimera, E. and R. Torrubia, Adaptación española del "Eating Disorder Inventory Inventory" (EDI) en una muestra de pacientes anoréxicas. Anal Psiquiatr, 1987. 3: 185-190.

- Purcell, S., B. Neale, K. Todd-Brown, et al., PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet, 2007. 81(3): 559-75. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Z., A. S. Kaplan, A.K. Tiwari, et al., The role of leptin, melanocortin, and neurotrophin system genes on body weight in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res, 2014. 55: 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E., M. Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M. Roszak, et al., Salivary opiorphin levels in anorexia nervosa: A case-control study. World J Biol Psychiatry, 2020. 21(3): 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Martinussen, M., O. Friborg, P. Schmierer, et al., The comorbidity of personality disorders in eating disorders: a meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord, 2017. 22(2): 201-209. [CrossRef]

- Gazzillo, F., V. Lingiardi, A. Peloso, et al., Personality subtypes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry, 2013. 54(6): 702-12. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, II and T.D. Gould, The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. AJ Psychiatry, 2003. 160(4): 636-45. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.P., C. M. Lindgren, E. Zeggini, et al., A powerful approach to sub-phenotype analysis in population-based genetic association studies. Genet Epidemiol, 2010. 34(4): 335-43. [CrossRef]

- Boraska, V., O. S. Davis, L.F. Cherkas, et al., Genome-wide association analysis of eating disorder-related symptoms, behaviors, and personality traits. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, 2012. 159B(7): 803-11. [CrossRef]

- Jones, H., V. V.W. McIntosh, E. Britt, J.D. Carter, J. Jordan, C.M. Bulik, The effect of temperament and character on body dissatisfaction in women with bulimia nervosa: The role of low self-esteem and depression. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 2022. 30(4): 388-400. [CrossRef]

- Leskela, T.T., P. M. Markkanen, I.A. Alahuhta, J.T. Tuusa, U.E. Petaja-Repo, Phe27Cys polymorphism alters the maturation and subcellular localization of the human delta opioid receptor. Traffic, 2009. 10(1): 116-29. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A.E., H. Sato, L.M. Nielsen, et al., The genetic influences on oxycodone response characteristics in human experimental pain. Fundam Clin Pharmacol, 2015. 29(4): 417-25. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C., S. C. Kuo, T.C. Yeh, et al., OPRD1 gene affects disease vulnerability and environmental stress in patients with heroin dependence in Han Chinese. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Bol Psychiatry, 2019. 89: 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I., E. Hiripi, H.G. Pope, Jr., R.C. Kessler, The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry, 2007. 61(3): 348-58. [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, E., A. Grzywacz, J. Samochowiec, The association of catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype with the phenotype of women with eating disorders. Brain Res, 2010. 1307: 142-8.

- Gamero-Villarroel, C., L. M. Gonzalez, I. Gordillo, et al., Impact of NEGR1 genetic variability on psychological traits of patients with eating disorders. Pharmacogenomics J, 2015. 15(3): 278-83. [CrossRef]

- Gamero-Villarroel, C., I. Gordillo, J.A. Carrillo, et al., BDNF genetic variability modulates psychopathological symptoms in patients with eating disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2014. 23(8): 669-79. [CrossRef]

- Gamero-Villarroel, C., L. M. Gonzalez, R. Rodriguez-Lopez, et al., Influence of TFAP2B and KCTD15 genetic variability on personality dimensions in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Brain Behav, 2017. 7(9): e00784. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.M., A. Garcia-Herraiz, S. Mota-Zamorano, I. Flores, D. Albuquerque, G. Gervasini, Variants in the Obesity-Linked FTO gene locus modulates psychopathological features of patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Gene, 2021. 783: 145572. [CrossRef]

- Mercader, J.M., F. Fernandez-Aranda, M. Gratacos, et al., Blood levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlate with several psychopathological symptoms in anorexia nervosa patients. Neuropsychobiology, 2007. 56(4): 185-90. [CrossRef]

| Tag-SNP | Alleles | Position | MAF | HWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2236861 | G/A | 1:28813244 | 0.394 | 0.586 |

| rs2236860 | C/T | 1:28814236 | 0.355 | 0.819 |

| rs533123 | A/G | 1:28814643 | 0.408 | 0.758 |

| rs678849 | C/T | 1:28818676 | 0.25 | 0.483 |

| rs3766951 | T/C | 1:28843047 | 0.433 | 0.531 |

| rs509577 | A/C | 1:28845884 | 0.458 | 0.545 |

| rs513269 | C/T | 1:28846339 | 0.394 | 0.208 |

| rs72665504 | G/A | 1:28847410 | 0.465 | 0.530 |

| rs529520 | A/C | 1:28848434 | 0.203 | 0.420 |

| rs499062 | T/C | 1:28848540 | 0.219 | 1.000 |

| rs67244013 | G/A | 1:28848988 | 0.469 | 0.168 |

| rs2873795 | G/T | 1:28850273 | 0.289 | 0.208 |

| rs508448 | A/G | 1:28855013 | 0.356 | 0.474 |

| rs204077 | C/T | 1:28862203 | 0.448 | 0.329 |

| rs2234918 | T/C | 1:28863085 | 0.334 | 0.543 |

| rs169450 | G/T | 1:28871216 | 0.255 | 0.828 |

| AN | BN | ED | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 221 | 88 | 309 | 396 |

| Age, years | 17.0±4.1 | 18.7±5.9ʃ | 17.5±4.7* | 32.6±8.0 |

| Weight, kg | 45.0±7.0 | 68.1±22.3** | 51.5±16.8* | 63.1±7.7 |

| BMI | 17.3±2.1 | 25.9±8.2** | 19.7±6.1* | 23.4±2.72 |

| Height, m | 1.61±0.07 | 1.62±0.06 | 1.61±0.07* | 1.64±0.06 |

| Total EDI2 | 89.9±46.3 | 121.4±41.0** | 98.8±47.0 | - |

| GSI | 1.6±0.8 | 2.0±0.8** | 1.7±0.8 | - |

| PST | 61.1±21.5 | 70.4±16.76** | 63.8±20.6 | - |

| PSDI | 2.2±0.6 | 2.4±0.6** | 2.3±0.6 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).