Methodology

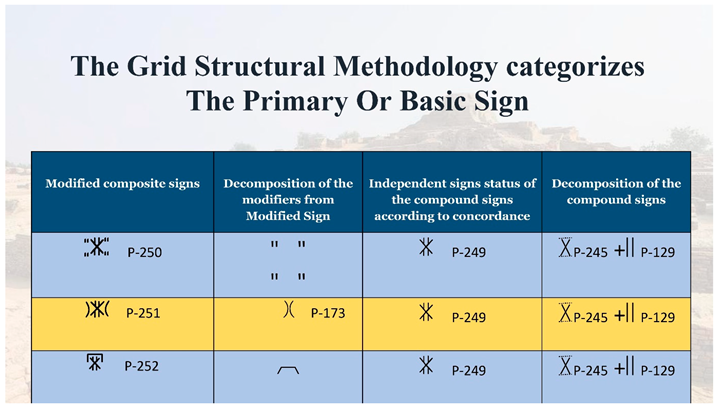

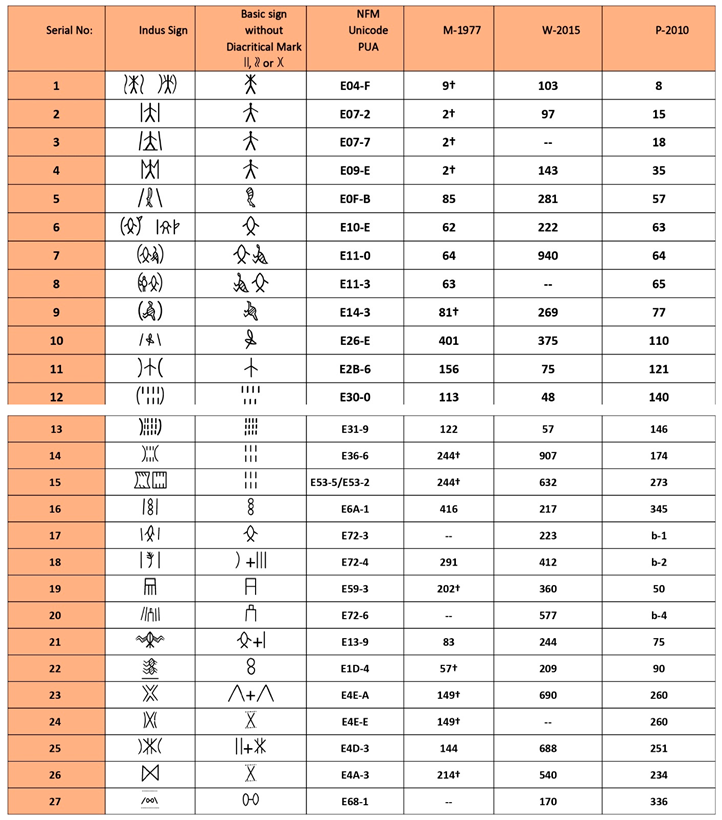

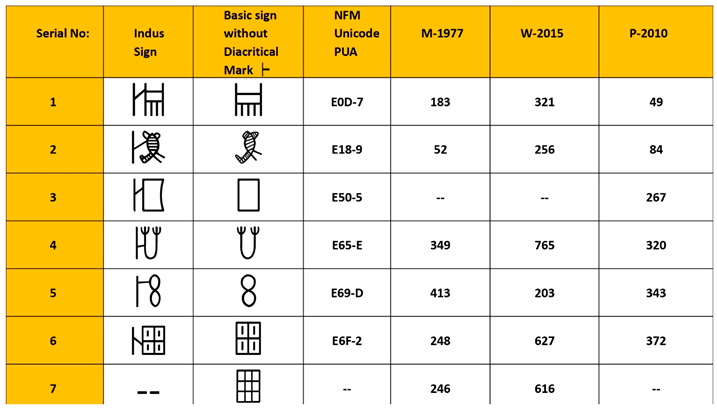

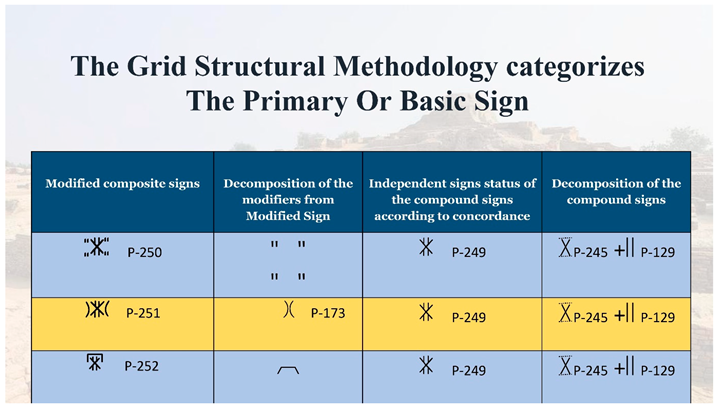

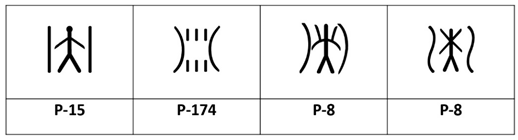

The process of isolating basic signs involves using a grid structural methodology to visually recognize and separate individual components within compound structures. This approach allows us to identify and distinguish basic signs from complex ligatures. By employing visual recognition techniques, we can isolate modifiers, diacritic marks, and composite signs within the modified signs, enabling analysis of their specific characteristics and contributions to the overall allography. Decomposing these elements provides insights into their function, phonetic value, reading, and meaning, enhancing our understanding of the Indus script’s writing styles and complexity. Further details on isolating basic signs are provided in the following section.

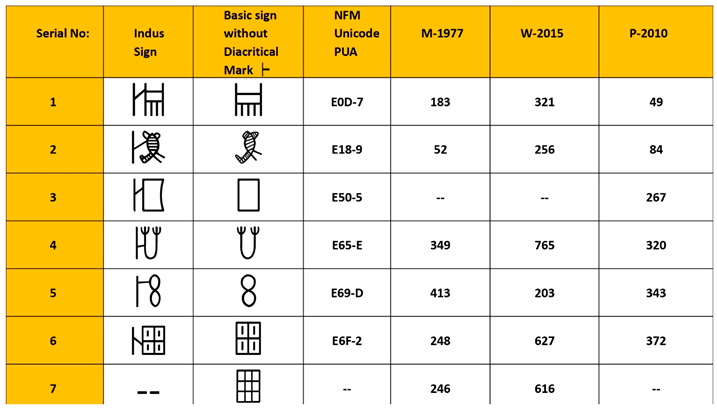

Compositing Primary Signs in Compound Signs (Ligatures)

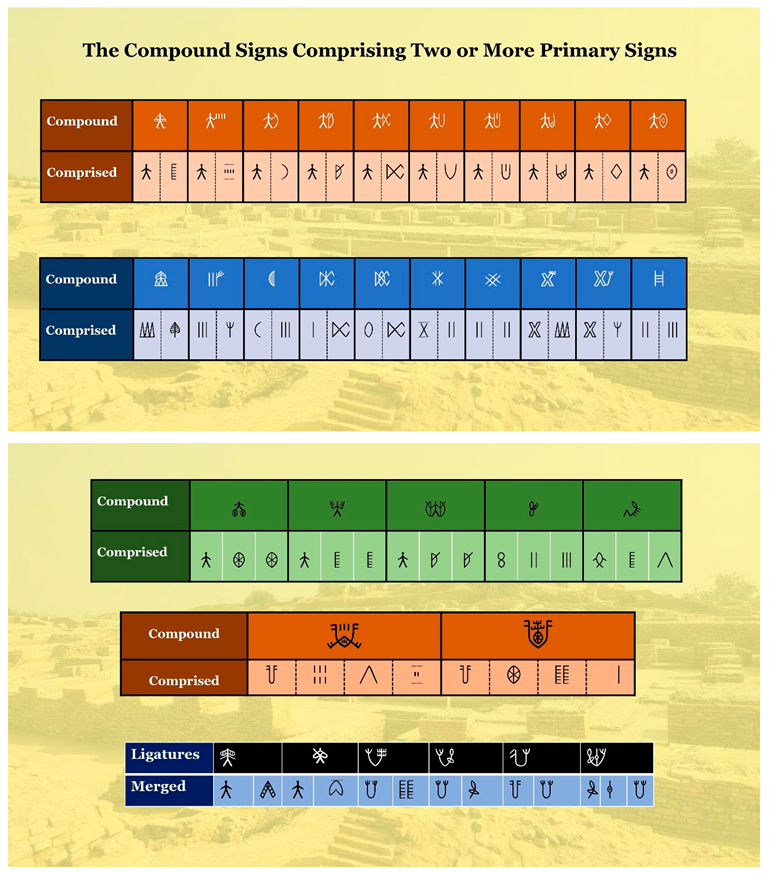

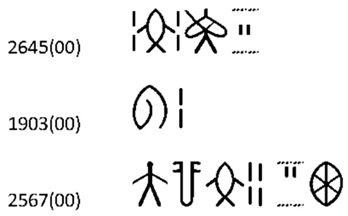

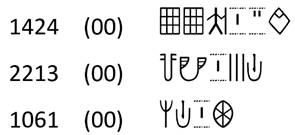

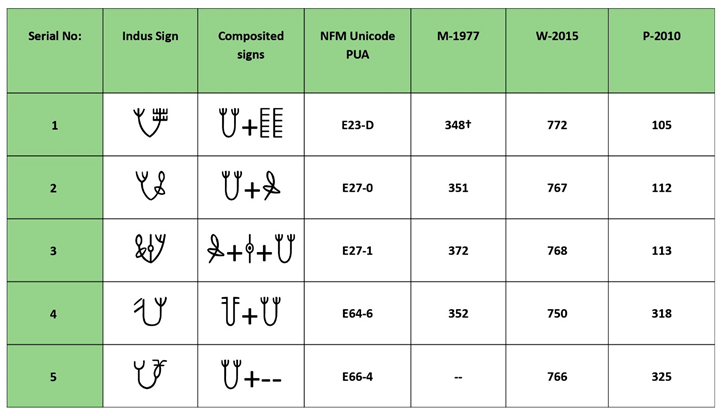

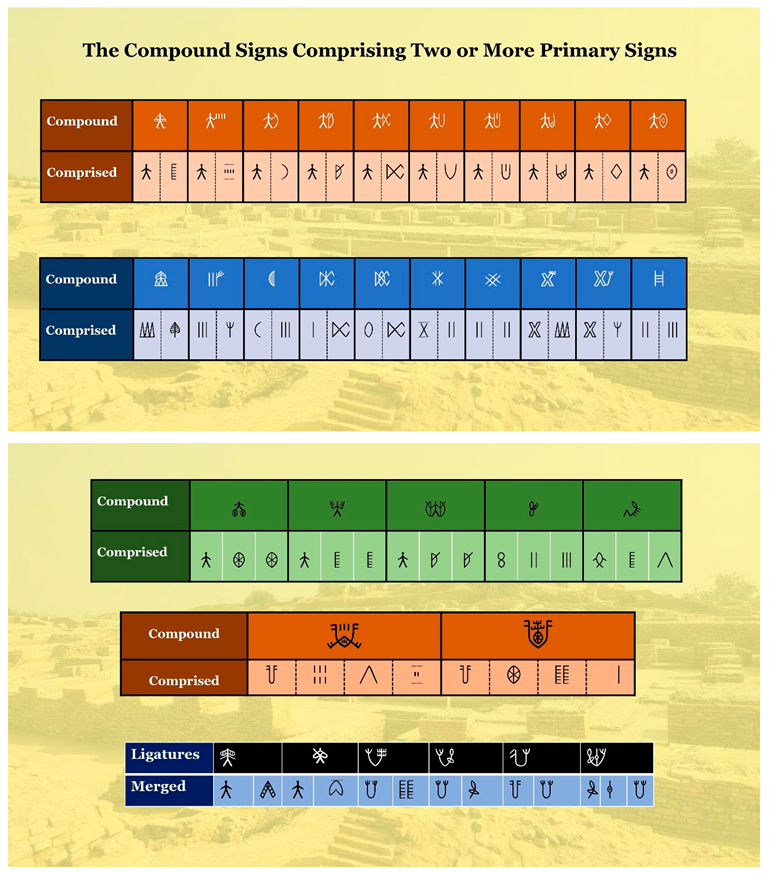

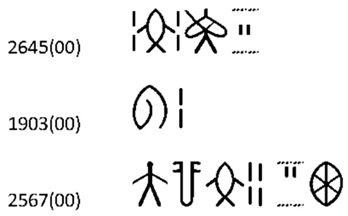

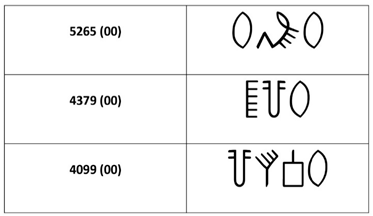

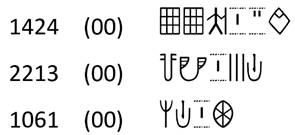

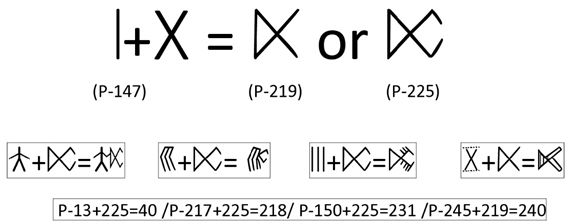

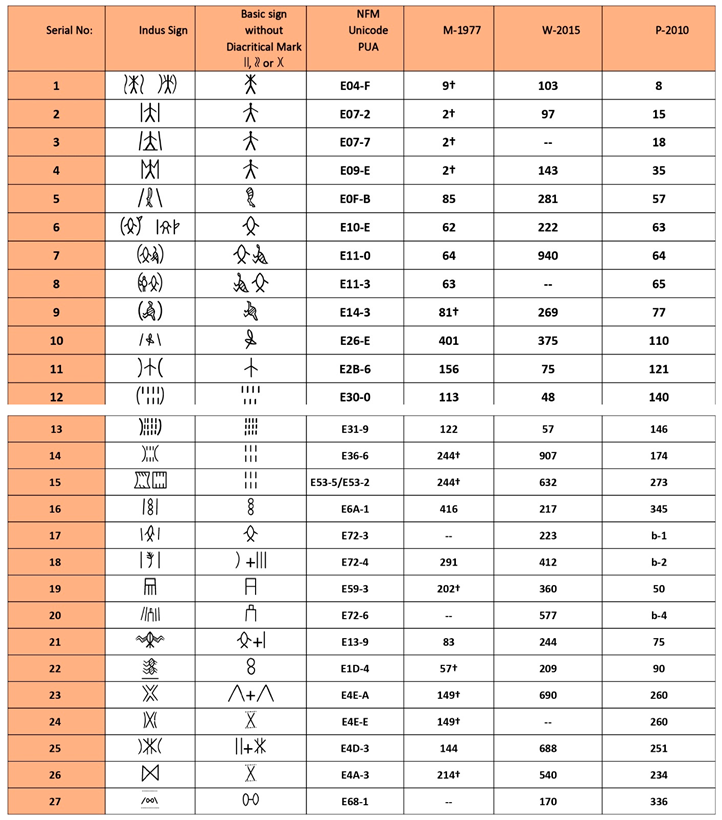

Currently, 90 compound signs have been identified, though this count may increase with further research. These compound signs are formed by combining two or more basic or primary signs into composite forms. The process of compositing involves merging individual phonemes to create a unified unit. Ligatures serve various purposes, such as enhancing aesthetics, improving readability, and efficiently representing frequently occurring combinations of allographs.

Within the compound signs, compositing brings together phonemes, the smallest meaningful units in the Indus writing system. This amalgamation can take different forms, such as merging allographic shapes or combining constituent parts. By integrating these components, compound signs establish a harmonious connection between the allographic variations of basic phonemes, resulting in a visually cohesive written representation. Notably, the process of combining elements within the Indus script has resulted in approximately 400 signs, many undergoing modifications similar to those observed in Brahmi (Kak, 1994).

The decomposition of compound signs has been conducted meticulously. It is crucial to recognize that compound signs should not be viewed as merely compressed versions of individual basic signs in the Indus texts. This is due to the infrequent occurrence of constituent basic signs appearing as sign sequences. Even when components of a compound sign do appear in certain combinations, the context of their use differs significantly (Yadav et al., 2010). Through careful observation and examination, the basic or primary signs have been isolated and identified.

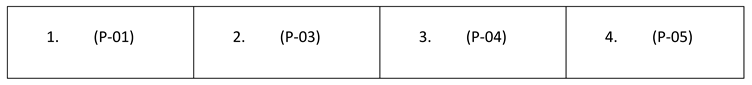

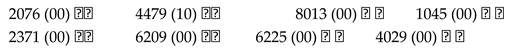

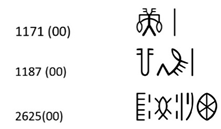

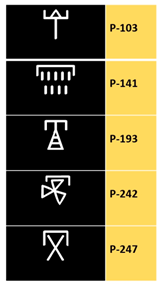

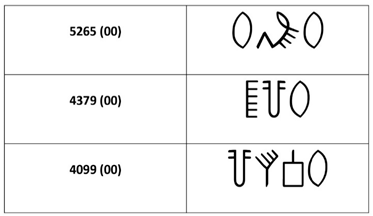

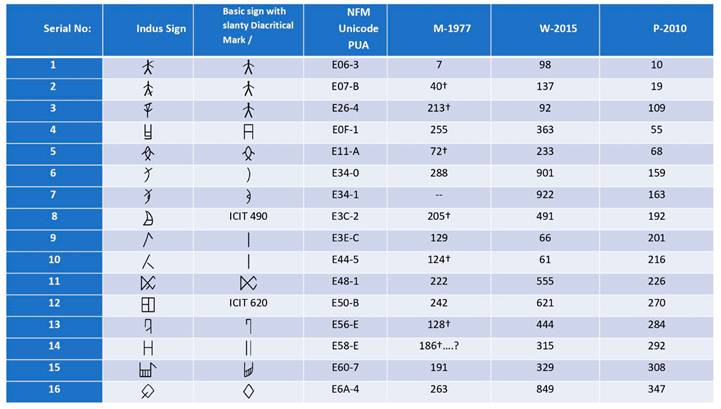

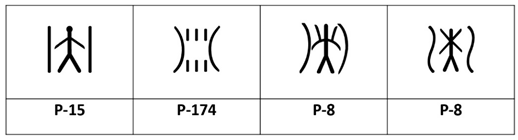

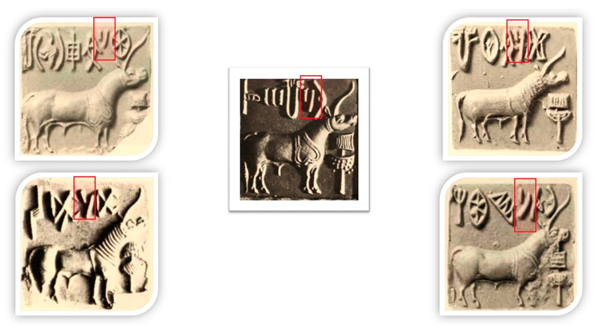

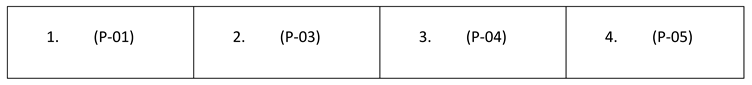

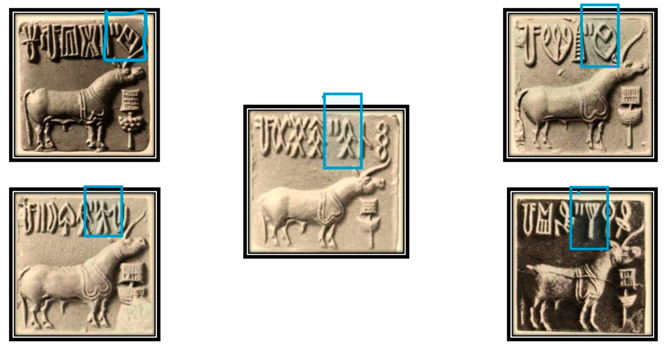

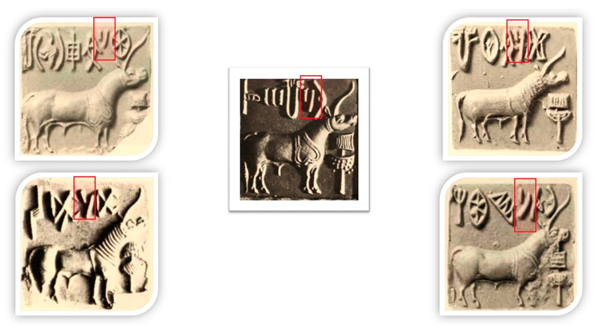

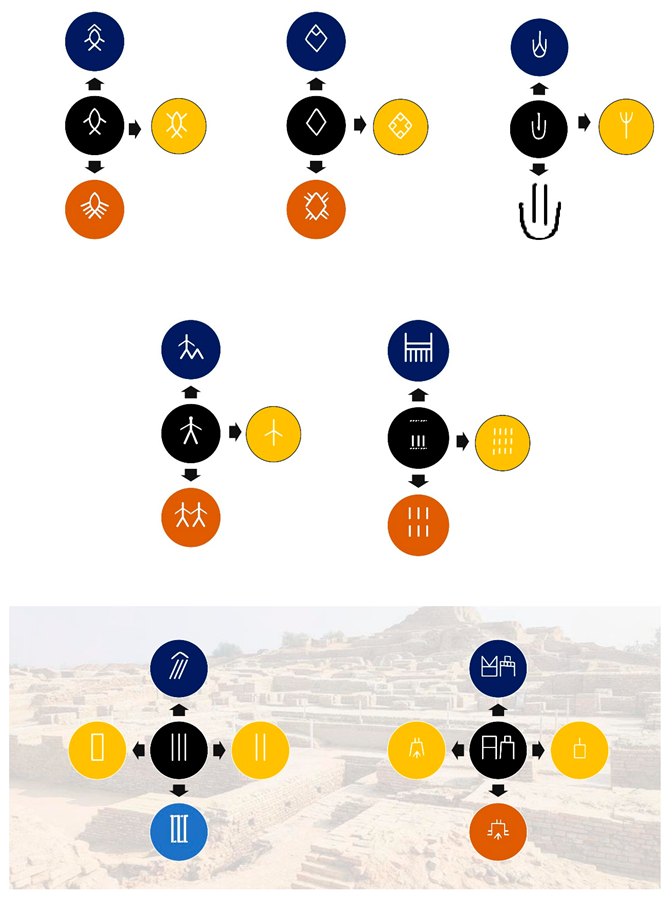

(FIG- 06) These signs are discussed well in the topic logographic sign Pati. (Muhammad, 2023)

Excluding the sign P-05 that has used only one time in the texts, the usage of the rest three signs with the same signs indicates the possibility of having the same value despite having some allographic variation:

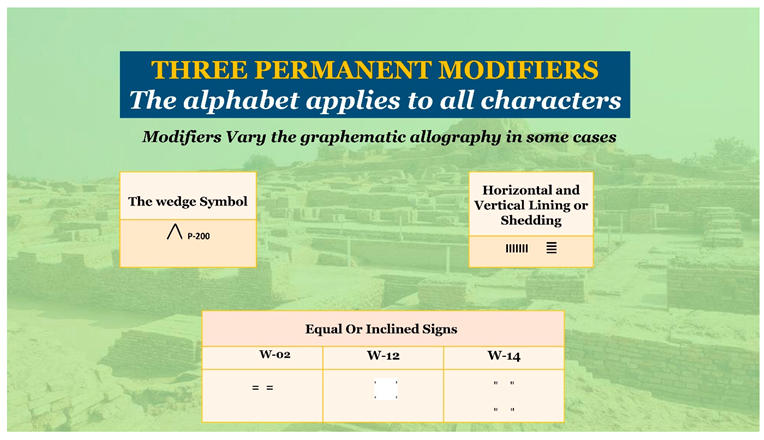

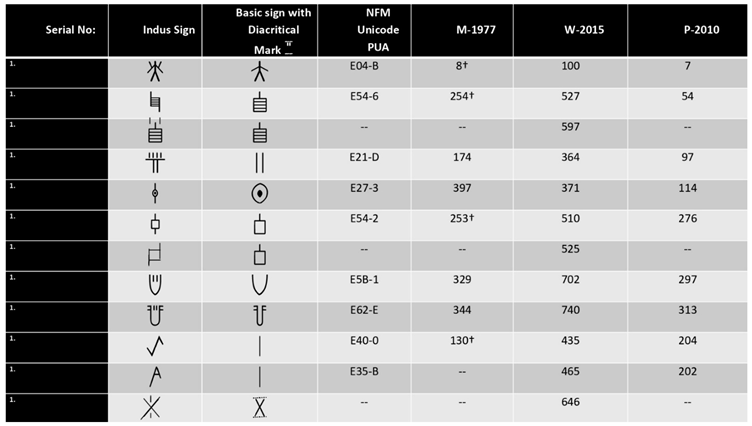

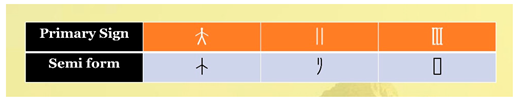

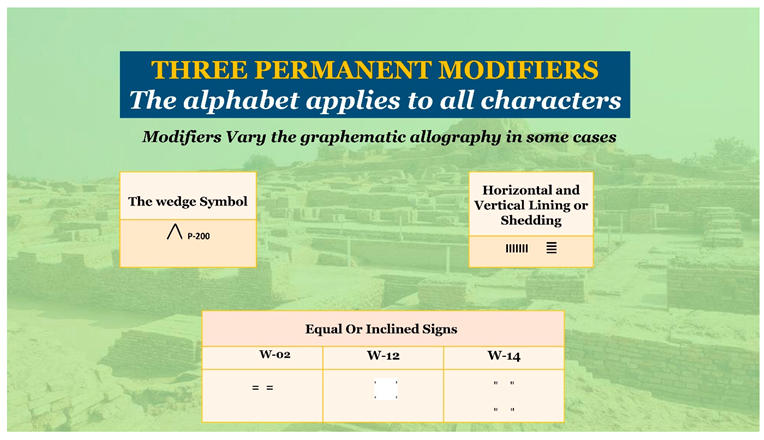

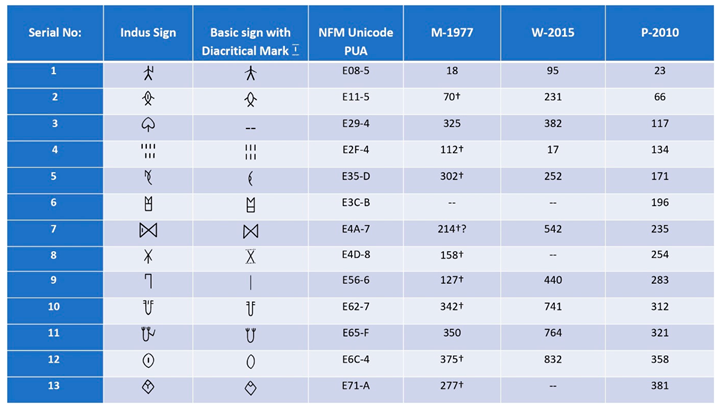

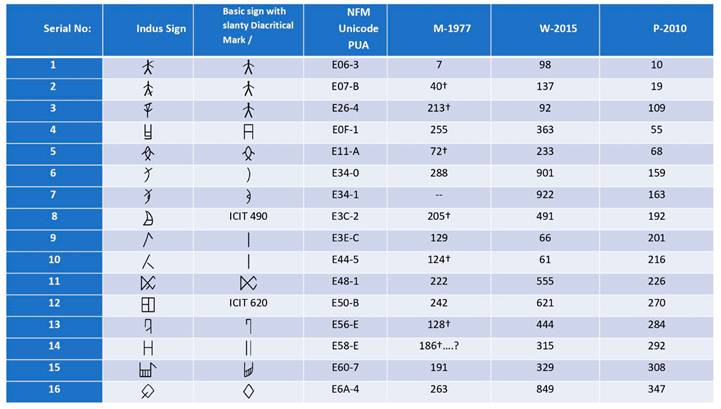

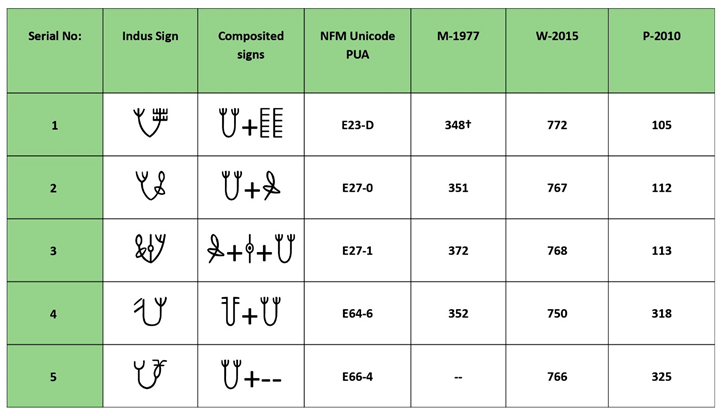

Three Permanent Modifiers

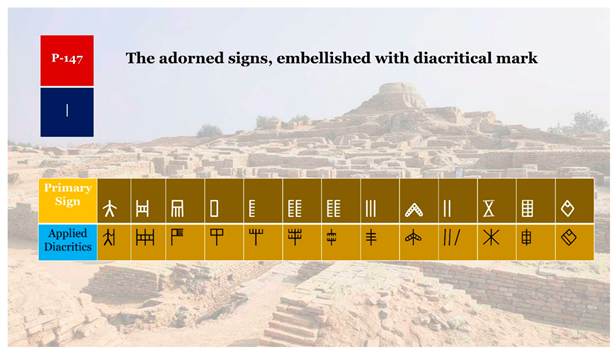

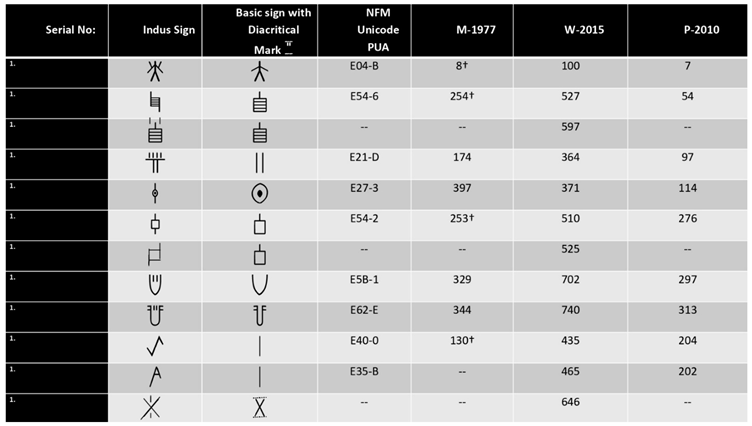

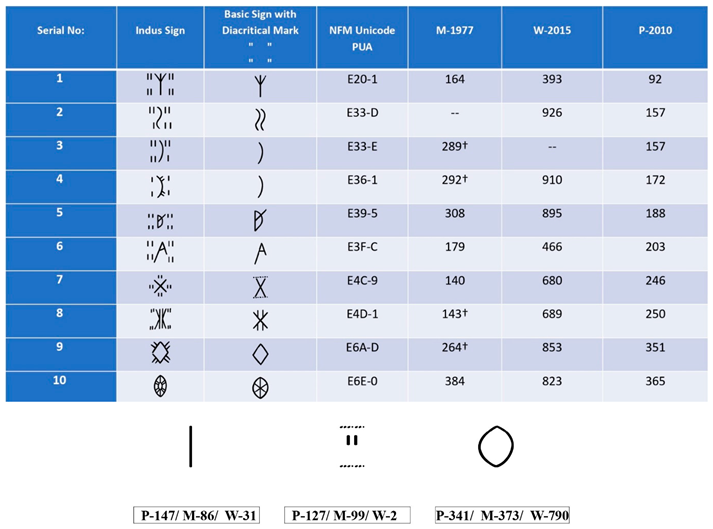

Examination of the Indus Writing System reveals a system of three distinct modifiers employed with base signs. These modifiers demonstrably alter the phonetic value associated with a base sign, expanding the inventory of phonemic distinctions. Each modifier exhibits consistent application patterns, yet these patterns vary across different base signs, influencing the resulting allographic form. This observation suggests a structured approach to sign modification within the system.

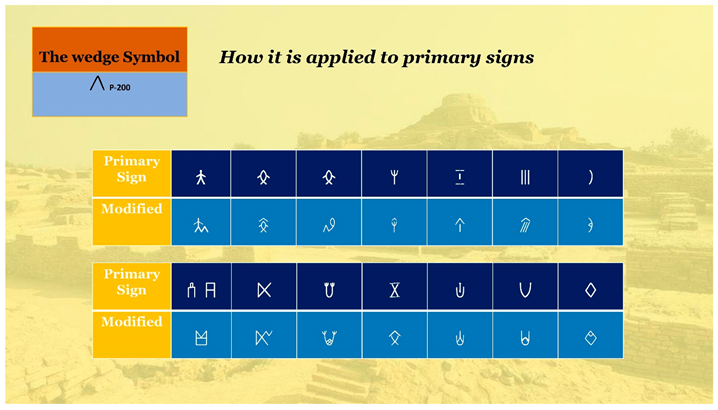

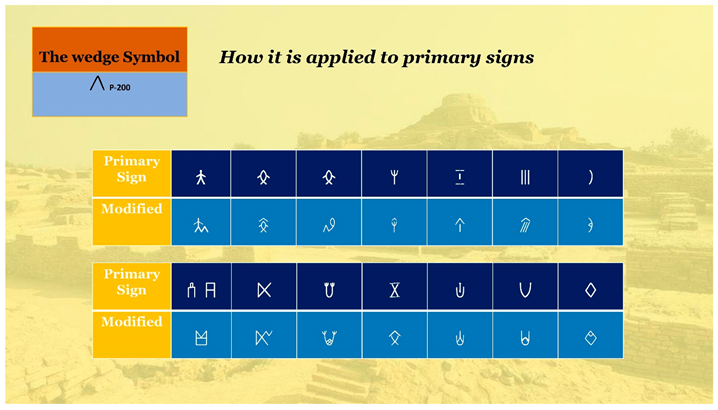

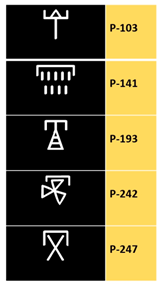

The Wedge Type Sign

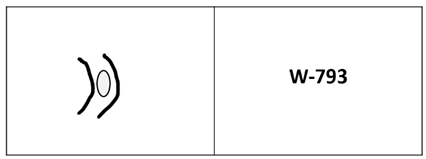

The frequent presence of a distinctive “wedge” sign merits further investigation. While limited to only nineteen characters, it exhibits consistent usage across diverse base signs, defying a strict applying rule. This suggests a potential role in modifying phonetic values across the alphabet. The wedge sign primarily associates with the main sign, typically positioned at the top (e.g., ). However, variations exist based on the underlying sign’s design (e.g., ).

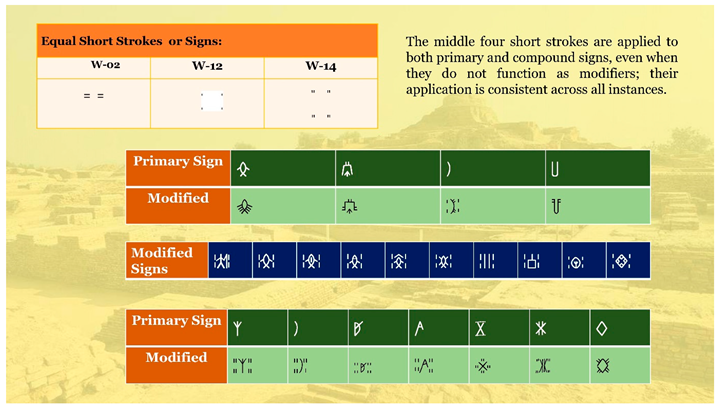

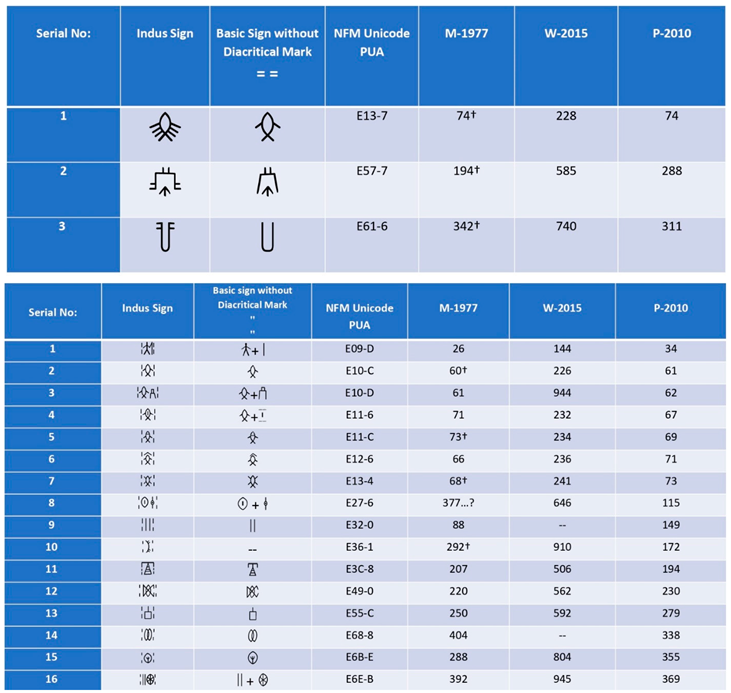

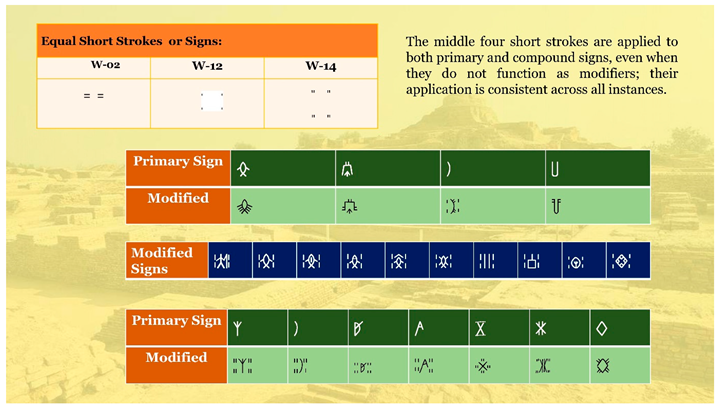

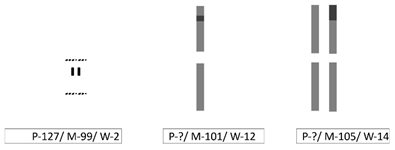

Double Horizontal and Quadruple Diagonal Modifiers

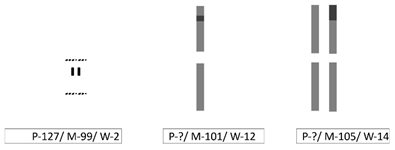

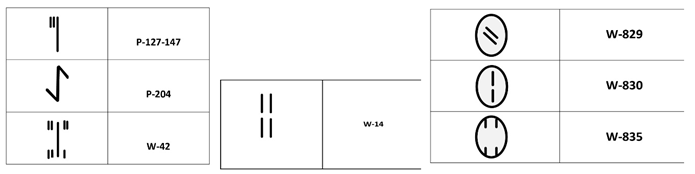

The usage of two equal signs or the double use of the sign P-127 as a modifier can be observed with signs P-(74, 172, 311, and 288). Furthermore, there are four inclined stroke signs that may function as modifiers and can be seen in association with 18 different basic, modify the combined or two independent single signs, such as the sign , , and . Upon careful analysis, it becomes apparent that the inscriber or engraver occasionally attempted to combine both the two equal signs and the four inclined strokes into a double inclined modifier sign. For instance, the sign P-172 was merged into P-157, albeit with one stroke missing. This practice can also be observed in other signs, including P-92 or P-351. It appears that the two equal signs modify the value, while the inclined signs may serve different functions, as indicated by their simultaneous usage on the two basic signs. These observations suggest that such modifications do not necessarily alter the significance or value of the individual primary signs.

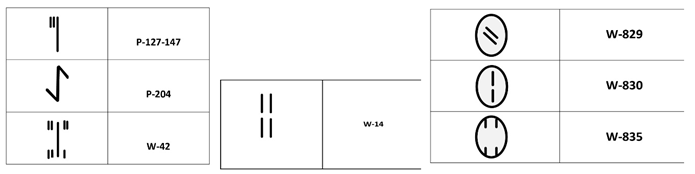

The independent form of the inclined sign can be represented by the signs W-14 and M-105, while its singular form is denoted by W-12 and M-101. The application of the two equal signs as a modifier appears to be a common practice to modify the primary sign, as seen in the example . However, when attempting to use both the equal signs and inclined signs simultaneously, the engraver deviates from the typical implied approach of the sign, resulting in variations such as . Nonetheless, the general concept of the design is maintained.

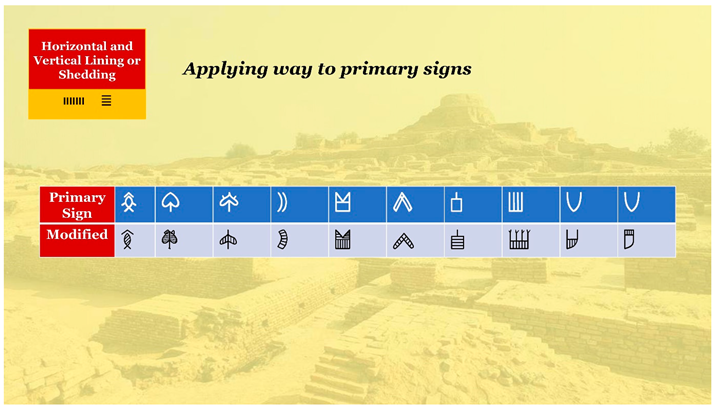

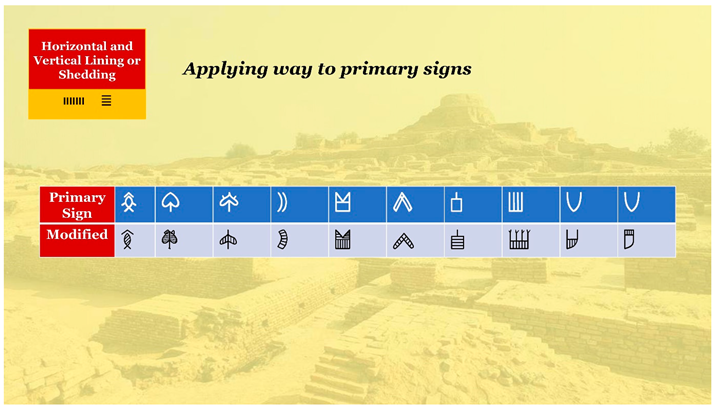

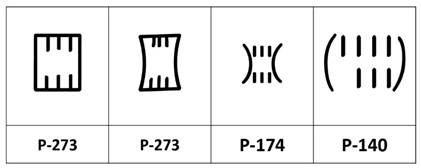

The Horizontal and Vertical Lining or Shedding

The observational analysis of the basic signs suggests that both shedding techniques may serve different functions in terms of adding phonetic variations. However, it is important to note that this discussion is not directly relevant to the purpose of classification or decomposition. As a result, the signs with both horizontal and vertical elements are presented together in the same table, regardless of their potential phonetic differences. IIII or ≣ : The vertical and horizontal shedding may have different functions as according to the general behavior in the usage in the texts but sometimes the engraver drops the strictness;

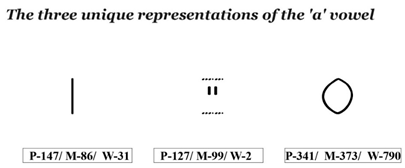

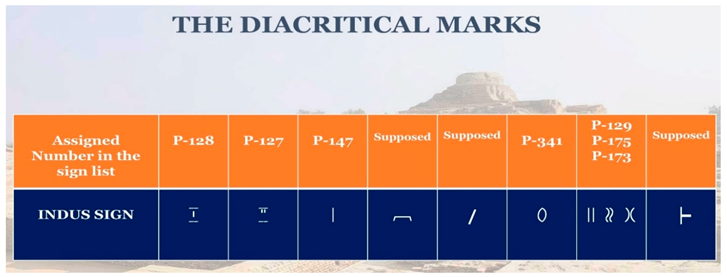

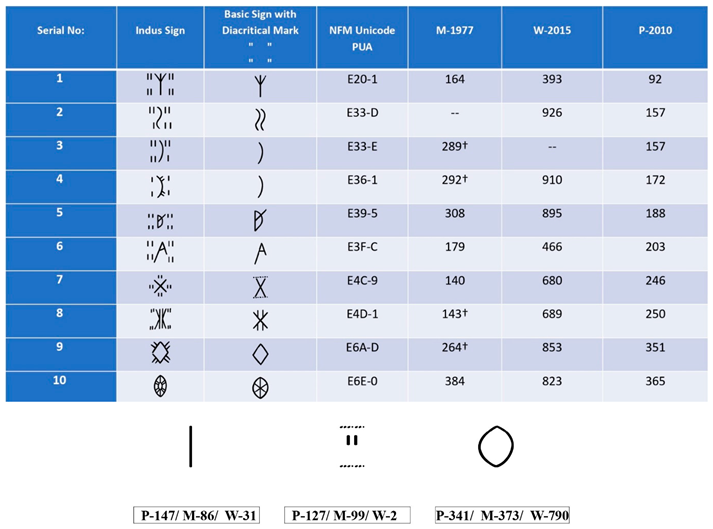

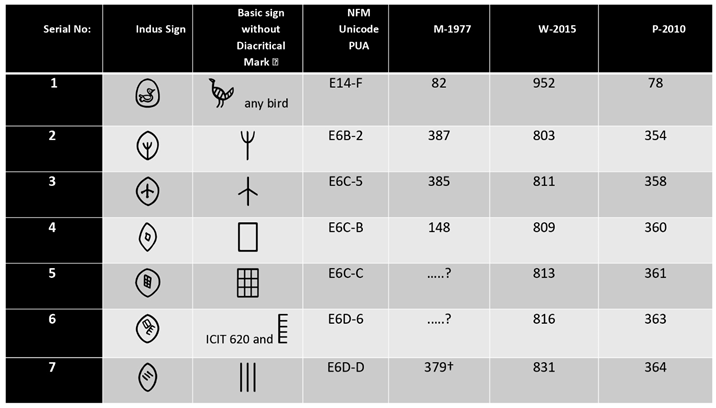

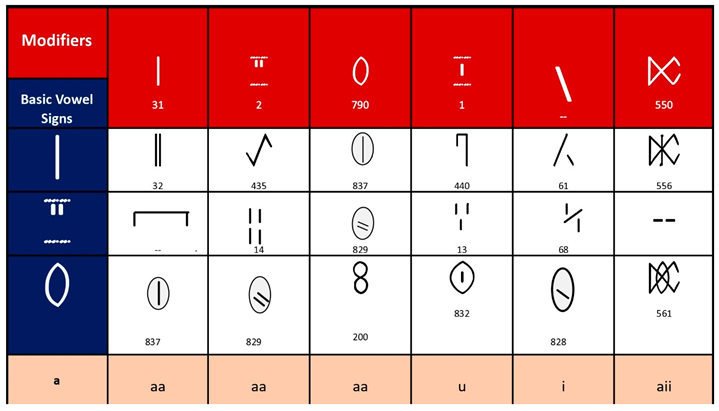

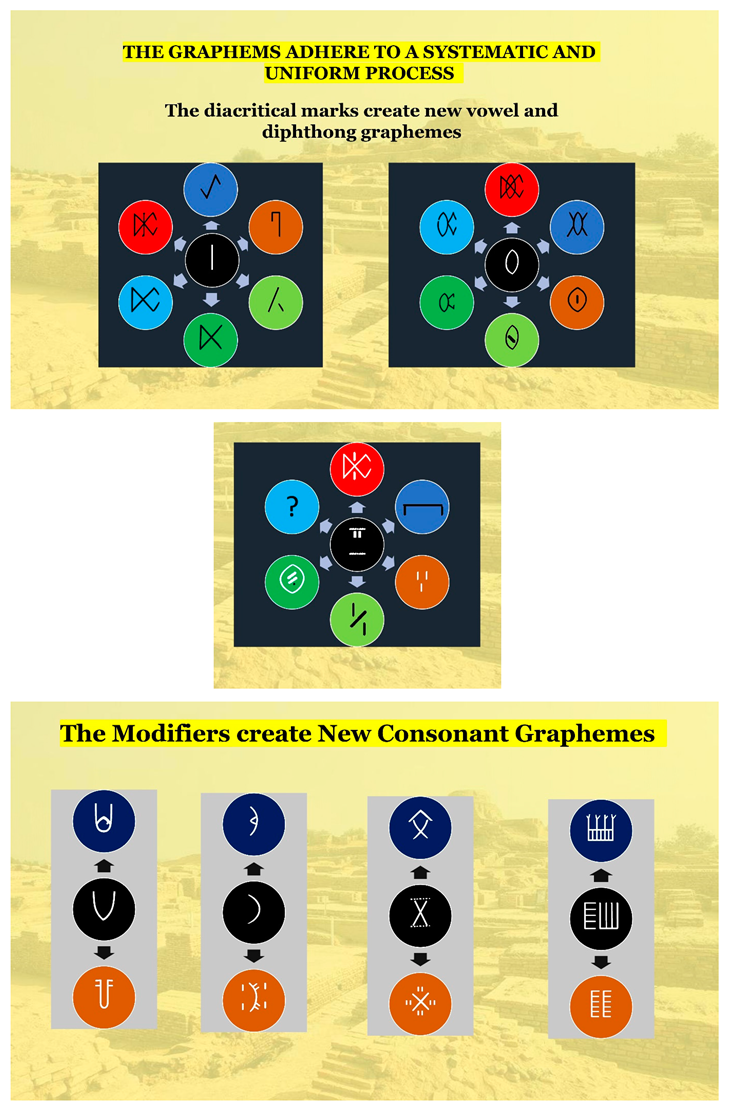

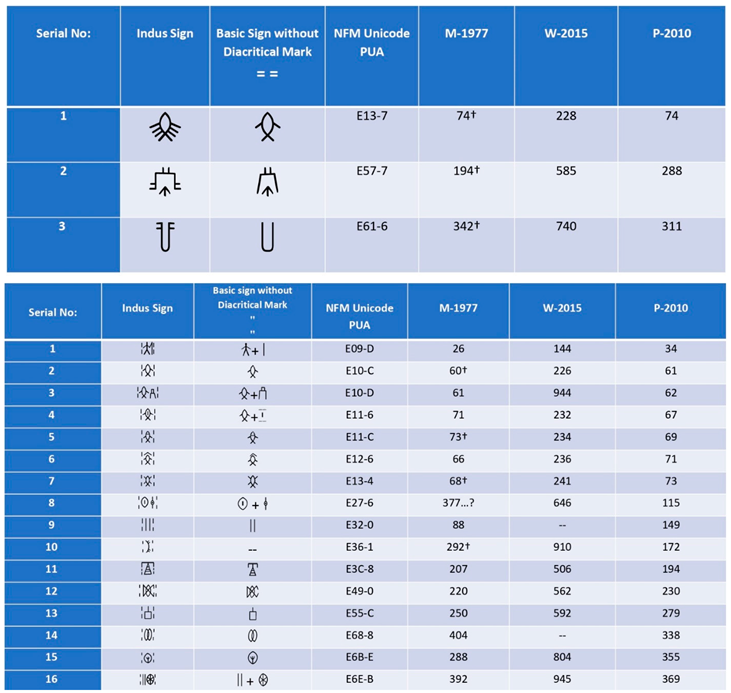

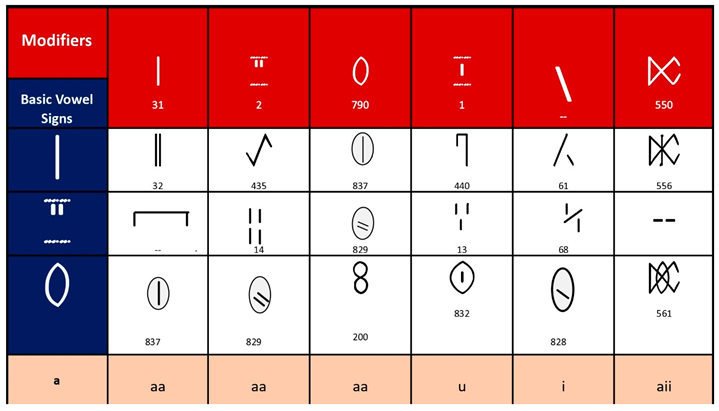

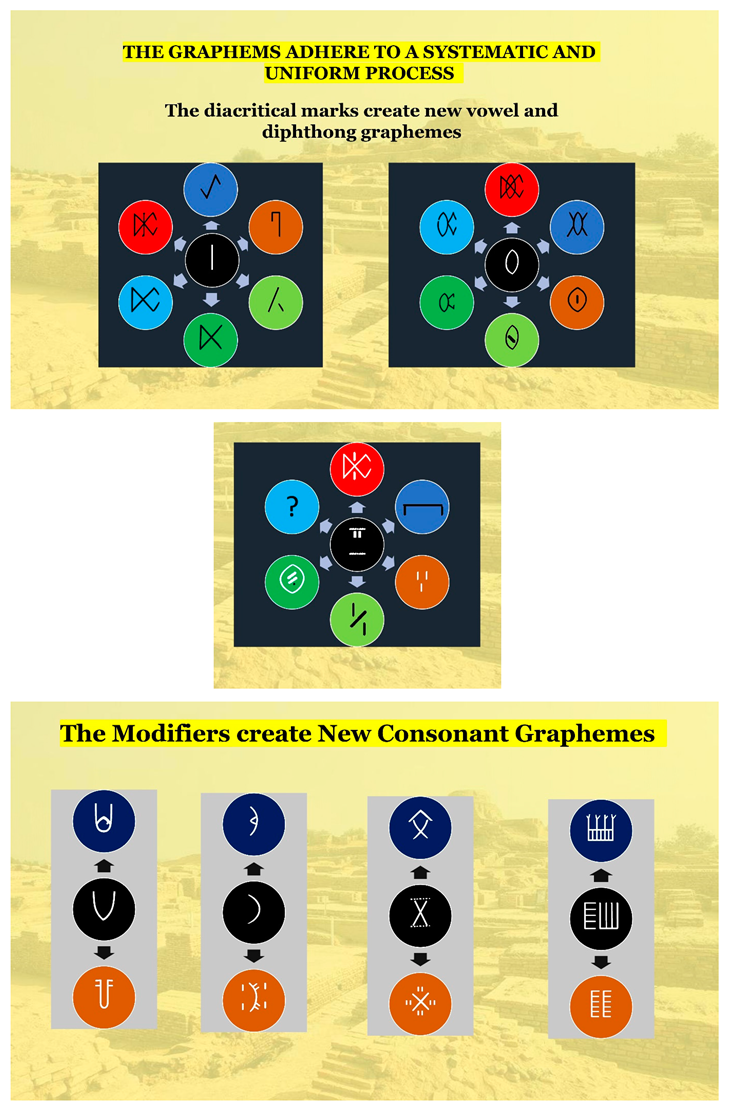

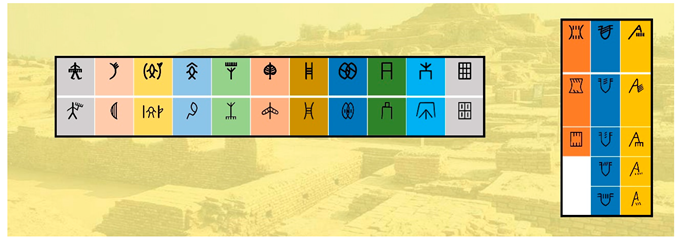

Indus Script Vowel System: Diacritics and Primary Signs

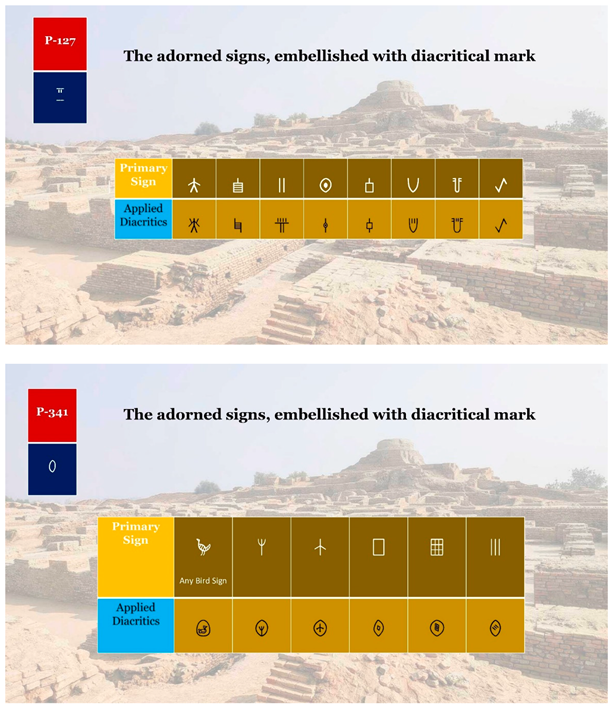

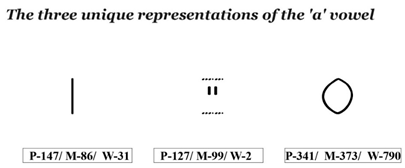

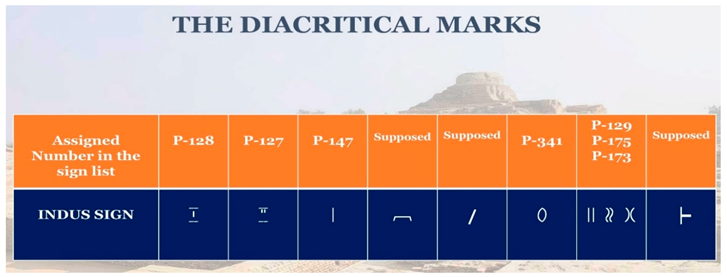

Analysis reveals eight distinct diacritics potentially influencing the vocalic repertoire of the Indus script. These diacritics likely served a phonemic function, similar to vowel markings used in various ancient and modern writing systems. Additionally, the script appears to possess three distinct primary signs potentially representing the vowel “a.” The identification of these signs is based on their resemblance to known vowel markers from other writing systems.

Dual Functionality of Indus Vowel Signs

The Indus script’s vowel signs exhibit remarkable versatility. Beyond functioning as independent phonetic entities.

These symbols also possess the ability to modify the phonetic values of other primary signs, or graphemes. This suggests a potentially complex interplay between vowels and consonants within the writing system.

Beyond three core vowel signs, the Indus script employs a consistent repertoire of diacritics modifying both vowels and consonant graphemes, suggesting a rich vocalic system.

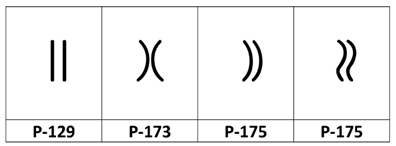

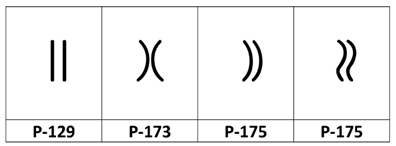

From the diacritical marks list, the signs P-128-129-175-173 are also used as independent graphemic characters. Supposed signs are implied as a modifier but not used as independent graphemes.

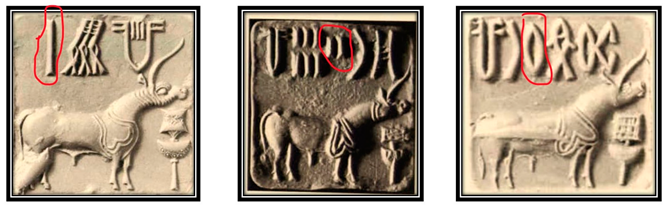

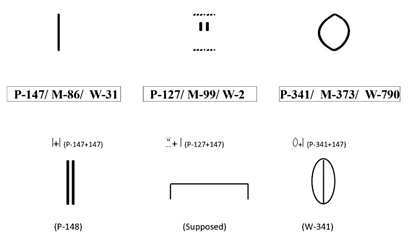

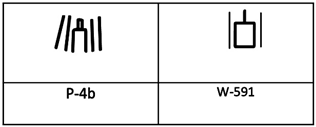

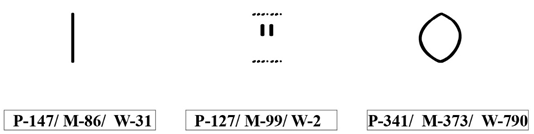

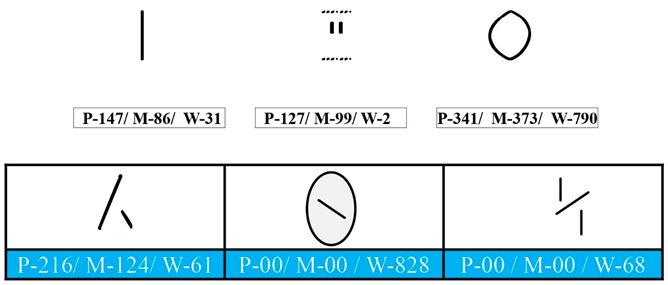

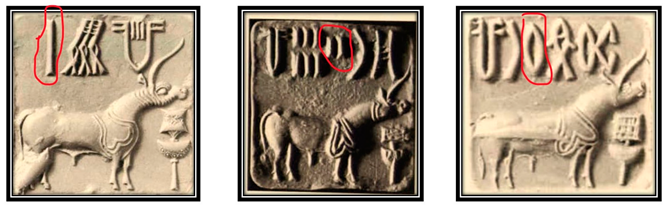

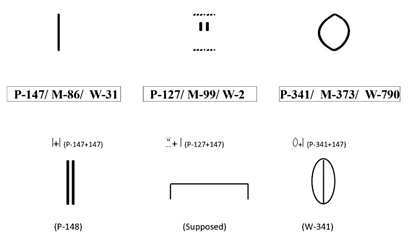

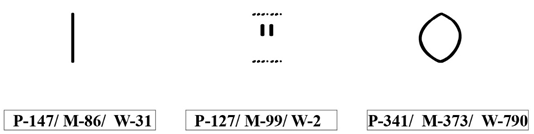

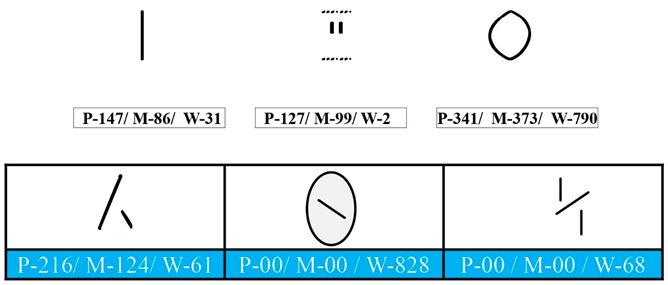

The sign P-147/M-86/W-31 has been used independently, indicating its separate value as a vowel.

and consistently modifying other consonantal graphemes as well

The only sign P-148, with its two vertical line strokes appearing very closely aligned, maybe a self-modification of the aforementioned vowel sign. However, it resembles the other sign P-129, only with the difference of space and therefore, this form does not appear frequently in usage. However, the use of the sign P-147 as a modifier with the other two primary vowel signs P-127 and 341 is evident.

The supposed sign (not included as an independent sign in the Indus Sign lists) is not found in a separate single form but only as a modifier in compound signs.

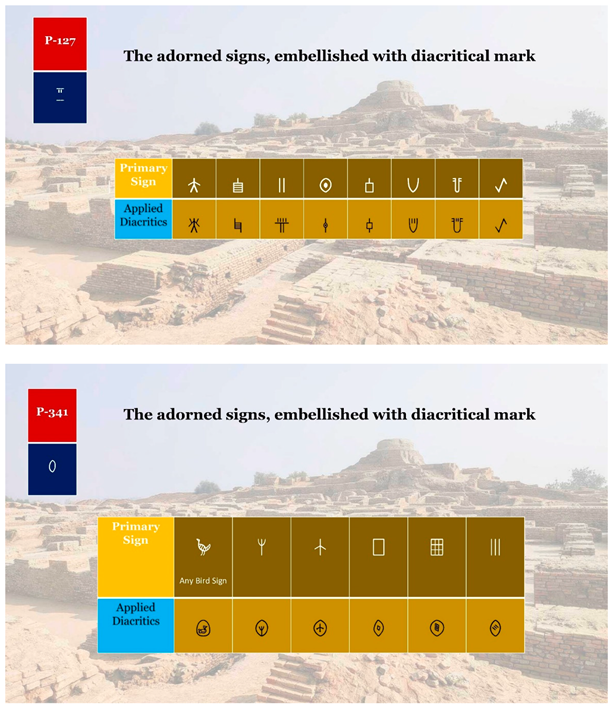

The vowel diacritical mark P-127 in the Indus Script exhibits the following allographic variations, with the last one being a dual form.

These three variations have been used as single independent graphemes and possess distinct phonetic values in the Indus Texts.

In its simple modification form, it has been mostly used at the left top of the other primary signs or graphemes.

However, in many cases, when applied to the primary signs or other consonantal graphemes, it alters the allographic shape of the primary sign or grapheme. The first (P-127) and second (M-101/W-12) variations of the two vertical short strokes have been applied according to the allographic formation of the sign. Sometimes, the variation forms extend, but the engraver seems to be attempting to maintain the allographic basics.

The third allographic variation of the sign (M-105, W-14), which consists of four short vertical strokes or two equal marks, functions as a singular form that modifies the other base signs.

If we consider the concept of modification for the below-mentioned signs, it appears that both singular and dual forms are in practice.

Then, we can perceive the same sense of modification for the third allographic variation of the sign (M-105/W-14) in the same way as a dual form.

Similarly, these sign variations modify the basic vowels.

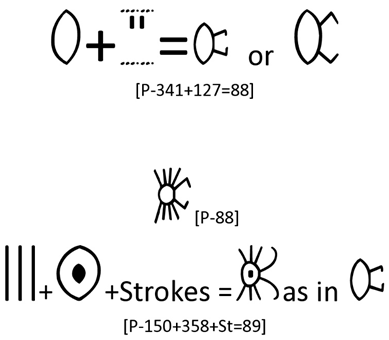

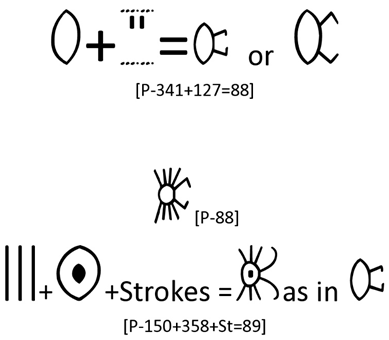

Among the three basic vowel signs, the third one (P-341/M-373/W-790) is also used as an independent grapheme with a separate phonetic value.

At the same time, it modifies the other consonantal signs or graphemes. However, its implementation is clear, but generally, it alters the shape of the primary signs as compound signs.

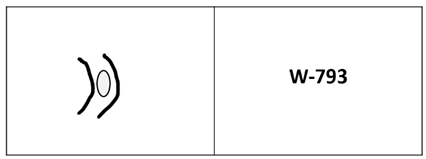

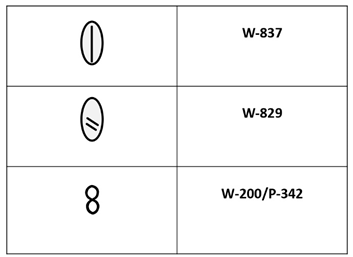

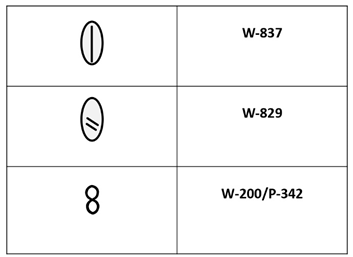

In Wells’s sign collection, another form of modification is found.

when it modifies the other basic vowel primary signs;

its allographic forms are;

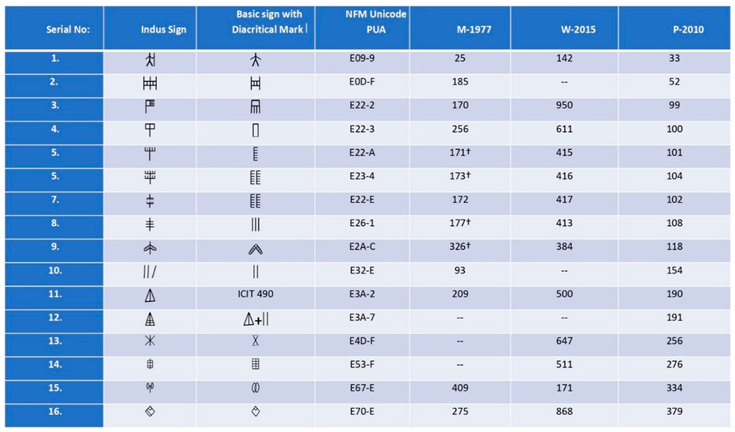

The short stroke sign P-128, M-97, and W-1 exhibits minor variations in size and placement within the text. It is also considered a vowel grapheme, being used independently as a separate character with its own distinct phonetic value.

In its simple form, this sign modifies the phonetic value of other graphemes. It is predominantly used at the left top of other primary signs or graphemes, similar to the usage of the sign P-127.

Simultaneously to the vowel sign P-127, when applied to primary signs or other consonantal graphemes, it alters the allographic shape. The vertical short stroke is applied in accordance with the allographic formation of the sign.

Similarly, it modifies the basic vowel signs;

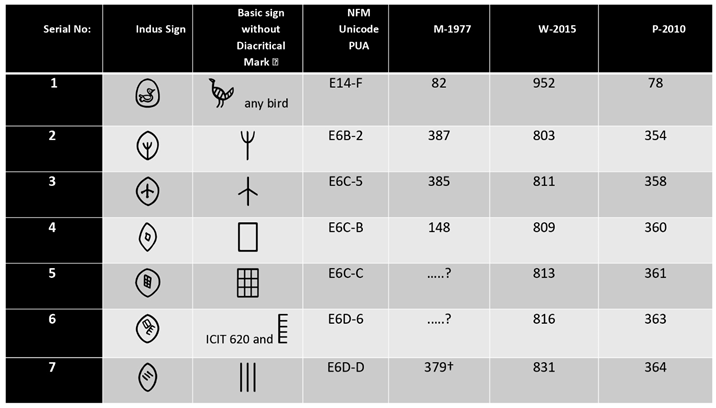

There is no example yet of the slanted short-stroke diacritical mark being used independently as a sign or grapheme in the Indus script. However, it may have a separate phonetic value, it is used only as a modifier mark, consistently modifying the consonantal graphemes or primary signs.

At the same time, it is applied to the three basic vowel signs and graphemes in the same manner.

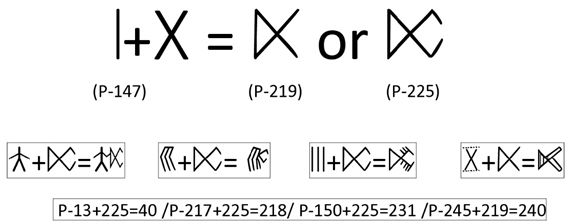

For additional vowel sounds, two crossed-slanted strokes are added to the primary sign P-147 to create a new vowel grapheme. These vowel graphemes also modify the consonantal graphemes or signs.

At the same time, it is applied to the three basic vowel signs and graphemes in the same manner.

Similarly, two short strokes added to the primary vowel sign P-341 create a new vowel grapheme. This is the only example found of its application, following the same concept of modification as the previous example.

Indus Script Vowel System: Consistent and Systematic

The Indus script exhibits a remarkably systematic approach to vowel representation. Basic vowel graphemes, whether used independently or combined, demonstrate consistent application. This uniformity facilitates the identification of potential vowels and diphthongs. Furthermore, the consistent use of these graphemes suggests a well-defined system for encoding phonetic elements, crucial for deciphering the script’s underlying language.

Note: All these assigned numbers are from Well’s signs collection

Other possible variations of the vowel signs include different orientations, positions, or additional diacritic marks that modify their phonetic values.

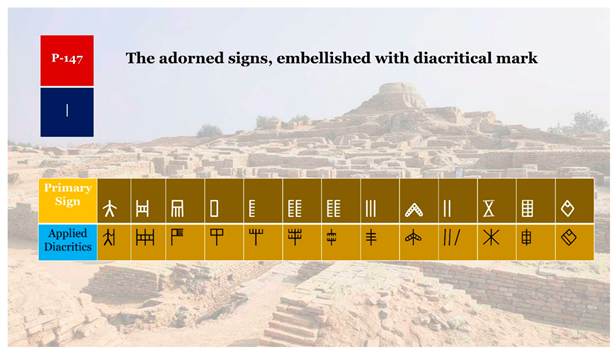

Indus Script Diacritics: Possible Semi-Vowels

Diacritics positioned on primary signs in the Indus script exhibit unique behavior compared to other composite signs. They seem to act as semi-vowels, modifying the primary sign’s pronunciation without full integration. This suggests a distinct phonetic role, potentially indicating the presence of semi-vowel sounds within the writing system.

These diacritical marks have been utilized on the sides of primary signs.

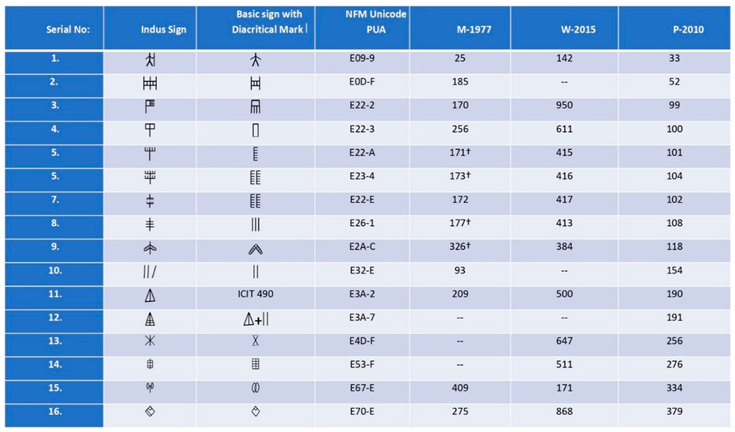

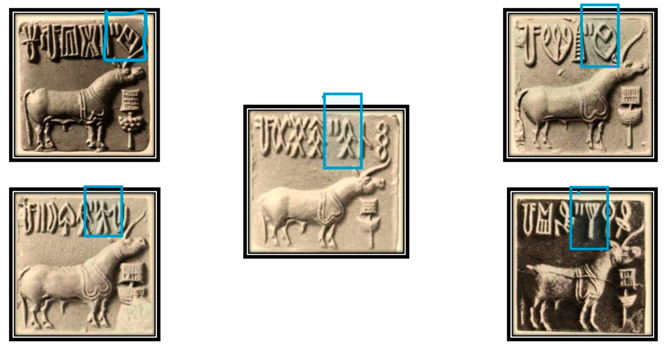

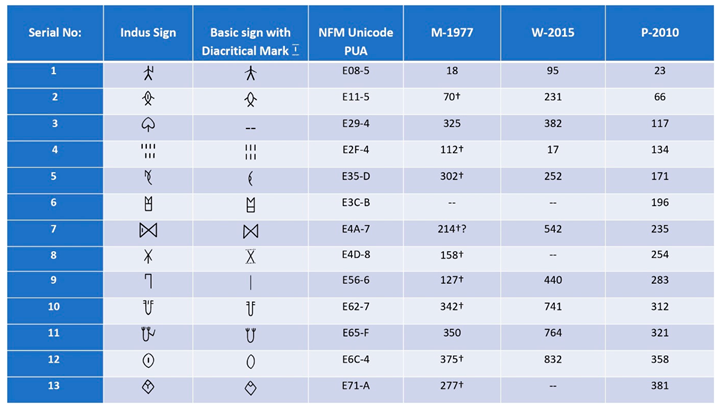

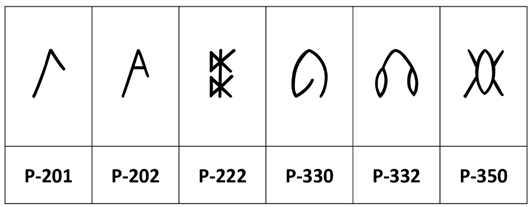

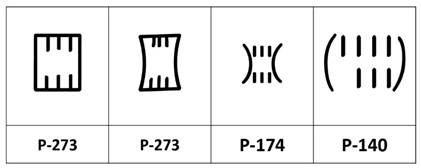

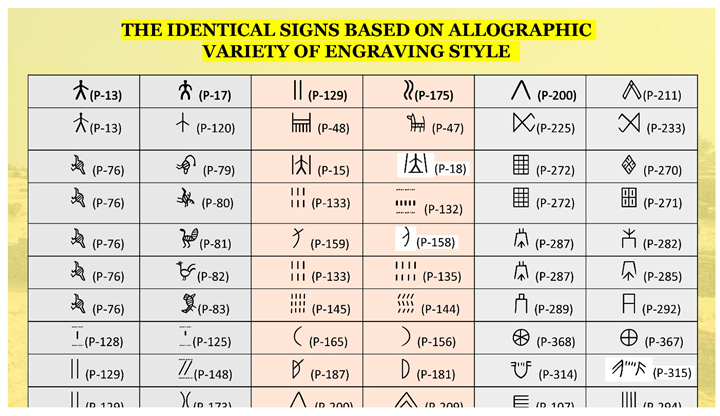

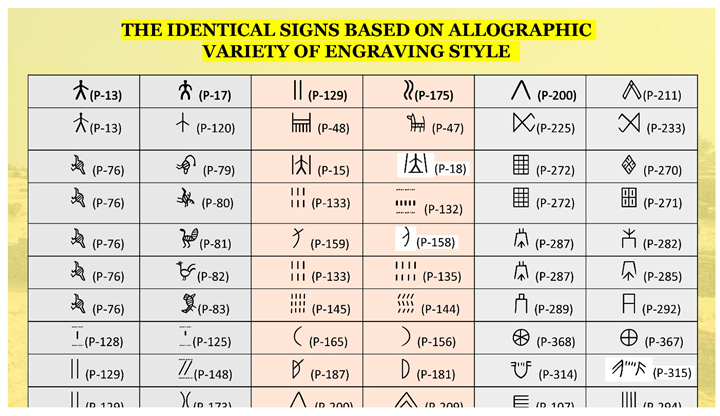

Mahadevan and Parpola accepted the variation of the sign P-175 as identical and assigned them the same number in their respective sign lists.

However, after meticulous observation, it can be noted that signs P-129 and P-173, as well as modifying signs in P-140, can also be categorized similar based on these variations.

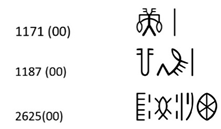

For further clarification, let’s consider an example from the texts.

These allographic variations of the sign P-129 have all been used in the same manner with other consonantal graphemes.

There is another semi-form of the previous sign P-129, used only on the left side of the primary sign.

The sign P-126, which is consistently used at the left top of the primary sign, likely functions as a diacritical mark. It also appears to be the semi-form of the sign P-129, with a similar usage but in a different manner.

There are examples of merged signs whose combining process differs from that of traditional compound signs. Therefore, the sign P-319 may have a semi-vowel value.

The Diacritical Marks Create New Vowel and Diphthong Graphemes

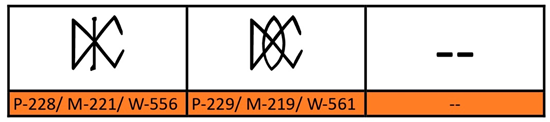

The Perception of Identical Signs: Examining Engraving Style Variation

This paper investigates the potential for seemingly distinct signs to represent the same underlying symbol within a particular writing system. While Parpola assigns separate identity numbers to the signs in question, this analysis suggests a reinterpretation. The observed variations appear to be minor and attributable to stylistic choices made by the engraver. These stylistic deviations may reflect the engraver’s artistic expression or inherent variability within the writing system itself. Further investigation into the context and frequency of these variations is necessary to definitively determine if they represent distinct signs or stylistic flourishes.

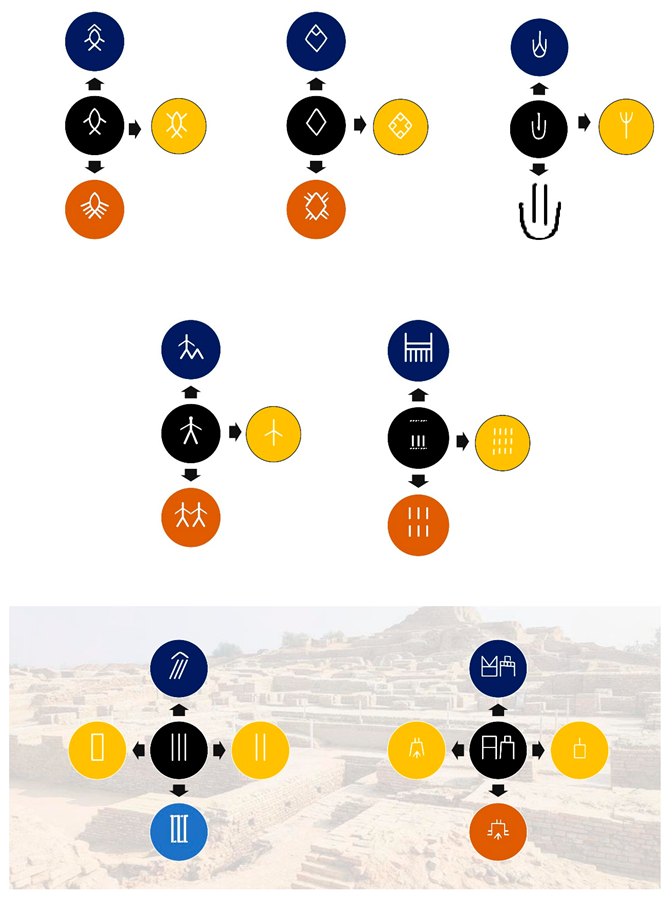

Rethinking Stroke Signs: Beyond Numerical Indicators

The prevailing view of stroke signs within the Indus writing system is that they function primarily as numerical indicators, directly linked to specific values. However, this perspective overlooks a crucial element: their versatility in usage. A closer examination reveals that stroke signs not only participate in grapheme representation but also undergo modifications akin to those observed with core signs. This observation challenges the prevailing classification and suggests that stroke signs may warrant reclassification as a type of primary sign, rather than being solely confined to a numerical role.

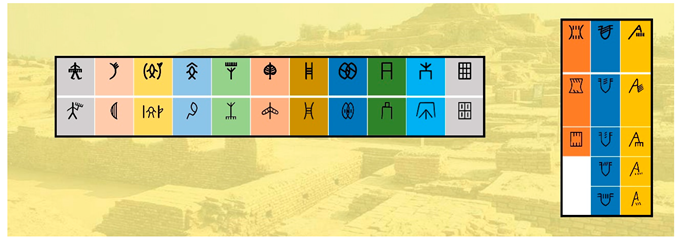

Interplay of Combining Techniques and Allographic Variations

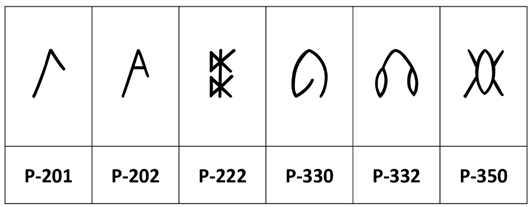

Positional Variability of Primary Signs in the Indus Script

This analysis explores the phenomenon of positional variability observed amongst primary signs within the Indus script. Evidence suggests that the placement of these signs can exhibit flexibility, potentially influenced by the engraver’s artistic preferences and the available writing space. Notably, this inversion does not appear to impact the phonetic value associated with the sign, nor does it necessarily represent a distinct form of the primary sign itself. The following examples illustrate this concept:

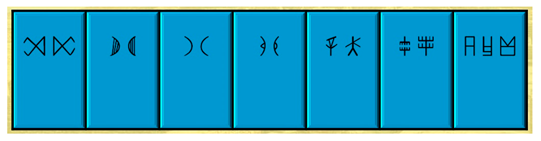

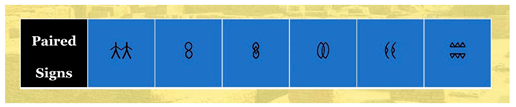

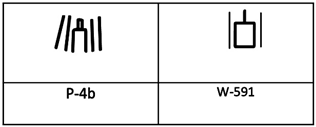

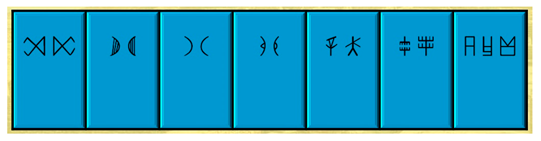

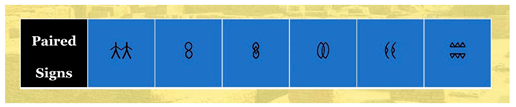

The Paired Primary Signs

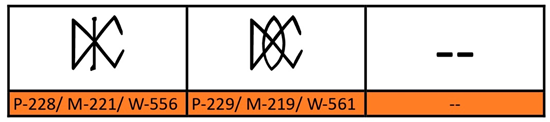

In M-77, 30 pairs of signs have been identified. Wells has classified all of them as independent signs in his sign collection. However, only some of these pairs have been given the status of independent signs in the sign collections of Mahadevan and Parpola.

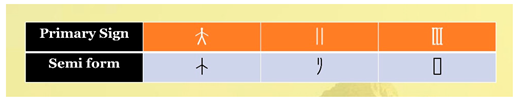

Semi Signs: Two additional signs, P-120 and P-266, appear to have been derived from the basic signs P-13 and P-270/W-620, respectively. These signs may represent a semi-phonetic value associated with the basic signs.

Classification of Primary Signs: A Foundational Approach

Analysis of the Indus Script Sigil Inventory

A rigorous examination has been undertaken of the Indus script’s sigil inventory. This analysis builds upon Parpola’s extensive compilation of 391 signs. Each sign underwent meticulous scrutiny to discern its design principles, underlying mechanisms, and stylistic variations across writing samples. For instances requiring further clarification, in-depth investigations were conducted. Additionally, the examination incorporates the updated collections of signs compiled by Wells and Mahadevan, bringing the total number of analyzed signs to over 404.

Despite potential counter-arguments concerning the deconstruction of individual signs, the core proposition of the Indus script functioning as an alphabetic writing system remains well-supported. This exhaustive approach fosters a deeper understanding of the actual number of Indus signs and their specific applications. Consequently, the notion of the Indus script as an alphabet is significantly bolstered by this comprehensive analysis.

or

or

or

or

or

or

or

or  or

or