1. Introduction

Lough Derg is perhaps best known due to its inclusion in Edith and Victor Turners’ classic (1978)

Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. 1 In their study, the Turners gave greater attention to Lough Derg than to any other pilgrimage site in Ireland. They classified Lough Derg as an ‘archaic pilgrimage -- a hybrid that had been shaped by older practices and traditions. The Turners also portrayed Lough Derg as the dominant symbol of Irish nationalism. But not all Irish Catholics have seen Lough Derg in that way. Many residents of the nearby town of Pettigo (a few miles from Lough Derg), for example, have never done a pilgrimage to Lough Derg, and they claim to know little of Lough Derg’s rituals. This is especially true for residents who work in resorts or operate bed and breakfasts in the area.

Given Lough Derg’s highly elaborate websites and the many postings by Lough Derg pilgrims, I anticipated that pilgrimages to Lough Derg would attract mostly recreational tourists. It does not. Like other pilgrimage sites, Lough Derg does blur the distinction between pilgrims and tourist and, in many respects, follows the Turners’ (1978, p. 20) famous dictum: “a tourist is half a pilgrim if a pilgrim is half a tourist.” In recent years, however, the dominant focus has become religious experience. What might make Lough Derg attractive to casual tourists would simultaneously lessen its appeal for many religious pilgrims.

As noted, Lough Derg rituals are intense: fasting, sleep deprivation, bare feet, prayer, no cell phones, and exposure to jagged rocks and the cold. Pilgrims do not (and are not expected to) see Lough Derg as a "pleasant" place. The local Tourist Board feels differently and boasts of numerous vacation homes, several high-end resorts, a monastery, and a yacht club. The tourist board touts the pristine environment, while the Lough Derg website compares the climate of Lough Derg’s Station Island to that of Alcatraz.

Between late-June and mid-August, thousands journey to Lough Derg to participate in 3-day, as well as shorter pilgrimages and One-Day retreats. Few provisions are made for casual visitors during the summer months and -- according to the Lough Derg website – the island is "too cold and damp" to allow for visitors during the winter months. Nevertheless, Lough Derg hosts multiple retreats during the colder months, and monks live year-round on in a monastery on another island less than a mile away.

The Lough Derg website notes that limited facilities are available for group retreats in the colder months -- but only when there are no pilgrims on the island. Retreat facilities are somewhat limited. While some the priests' quarters have central heating, most dormitories, the basilica, and areas frequented by pilgrims do not.

Lough Derg is mentioned in tourist guides like

Lonely Planet, Rough Guides, and on

TripAdvisor -- but these guidebooks do not recommend Lough Derg for tourists citing the rigors of the 3-day ritual.

2

The history of Lough Derg is extremely well-documented, but there has been comparatively little ethnographic research. Priests and workers are very forthcoming. They answer all questions thoughtfully and to the best of their knowledge. Pilgrims, however, are not as forthcoming. Lough Derg pilgrims are not encouraged to talk to one another or to outsiders during pilgrimages. To get around this, pilgrims often communicate non-verbally (Gierek, 2022).

3 Limited conversations take place while pilgrims are on the return ferry, while shopping at the Lough Derg giftshop, and while on return bus trips (Kaell, 2016).

4

Churches and other religious organizations offer chartered bus tours to and from Lough Derg. Group tickets usually provide round-trip bus transportation from Dublin and other locations. Interestingly, few group tours visit multiple sites. Lough Derg is a singular destination. Ticket holders are guaranteed transportation and a place on the ferry to and from Station Island. Individual pilgrims arrange their own transportation (by private car or public buses) and are not guaranteed a place on the ferry. Over the past ten years, the percentage of solitary pilgrims has declined. Clerics express concern about this.

As noted, pilgrims are expected to maintain a degree of silence. Theyare encouraged to fast during outward journeys (sometimes 4+ hours). They are allowed to talk on their return journeys, but – when they do --they seldom speak about their ecstatic experiences. On organized charters, many travelers are family members and friends of pilgrims who did not participate in the pilgrimage. As Hillary Kaell (2016) has pointed out, organized bus trips often create multiple opportunities for researchers to learn about the experiences of pilgrims. On the other hand, pilgrims to Lough Derg do not talk about their experiences beforel many months have passed. As in Spiritual Baptist mourning ceremonies,

5 the proof of religious experience becomes known long after the event is over. One of the most detailed participant-observation studies of Lough Derg was conducted in the 19th century by William Carleton (1844).

6 Carleton's interviewed pilgrims on row boats going back and forth from Station Island (see also Casey, 1971).

7

During 2020-2021, a high point of the covid epidemic, Lough Derg was closed. Activities focused on web postings and re=telling accounts of earlier pilgrimages. One-Day pilgrims posted most frequently. In 2021, One-Day pilgrims posted on Facebook: 34+ times, while 3-Day pilgrims posted on Facebook only 7+ times. Pilgrims who attend organized retreats posted to websites of their sponsoring organization – not the Lough Derg website. Two 2020 virtual pilgrims published articles in the Irish Times and the Princeton Review, respectively.

Lough Derg maintains a sophisticated web presence. Their website

<www.loughderg/live> is hosted almost 24 hours a day. It features: a webcam of the lake; Prior LA Flynn's daily blogs, selected items (6-7) for purchase from the giftshop, and a weekly newsletter. Prior LA Flynn himself posts twice-weekly updates on Instagram and tweets 10-20 times a day. Email inquiries receive a response, and LA Flynn sometimes responds personally to inquiries.

8 The goal is to make what happens at Lough Derg transparent.

2. A Brief Chronology of St Patrick's Purgatory from Cave to Island

Lough Derg is the name of two lakes in Ireland which gives rises to confusion. Lough Derg (Shannon) is a large lake on the Shannon River. It borders counties Clare and Tipperary. The second Lough Derg (the focus of this study) is in Donegal.

This is a site of great antiquity. Pilgrims have travelled to the second Lough Derg for over 1500 years (Nolan, 1983).

9 Martin Behaim's 1492 world map gives only one toponym (place name) for all of Ireland: "the penitential island of Lough Derg."

Lough Derg has been and remains strongly associated with St. Patrick, but – according to their own website --Patrick may not have visited the site which predates him. The earliest accounts of Patrick's Purgatory do not mention either an island or a lake (Zaleski, 1985)

10 In 1180, St. Patrick's Purgatory was said to be located on the top of a mountain. But according to the

Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii (13th century), the location of Purgatory was an Irish cave located in an "unspecified deserted place" (Taylor, 1995)

11 This cave was said to have been an entranceway into hell. Here, Patrick (and earlier pilgrims) are said to have witnessed the tortures of eternal damnation. In 1148, Knight Owein reported that he was dragged into the underworld at Lough Derg cave and was tormented by demons with iron hooks.

Depending on the century (and church politics) papal authorities have condemned, supported, and/or ignored Lough Derg. Prior to the eighteenth century, most pilgrims visited two separate sites: a cave at the lakeshore and a basilica on Station Island. The cave was considered the primary destination.

The strongest statement of papal support for Lough Derg came in 1870 when Pope Pius IX granted

Perpetual Plenary Indulgences 12 to pilgrims making a journey to Lough Derg. Notice of Pope Pius's indulgence is prominently featured on the current Lough Derg website. The website also lists multiple visits by papal nuncios between 1870 and 2018.

The first official reference to Lough Derg is in the Annals of Ulster 1497. The Annals report that Pope Alexander VI ordered a cave at Lough Derg be "broken." Evidently, Pope Alexander VI's orders were not followed or perhaps a different cave was destroyed. In 1632, the Anglican Bishop of Clogher ordered the destruction of a cave. Again, the cave does not seem to have been destroyed, and it was reportedly open to pilgrims in 1635. Finally -- in 1780 -- the cave was destroyed, and, after 1780, Station Island became the only sanctioned pilgrimage site at Lough Derg. It remained so until 1997 when a rustic Pilgrim Path was constructed on the lakeshore. The path, which has become a new focus for pilgrims was refurbished in 2006 and again in 2021. The current Pilgrim Path circles around the original cave site. Some things are emphasized. Other things are not. There is elaborate signage marking Holy Wells, sacred trees, natural features of the landscape -- but no sign marking a cave site.

For most contemporary travelers on the Pilgrim Path, a major attraction is three Holy Wells.

13 After 1780, water (lake water/ Holy water) became the dominant sacred symbols at Lough Derg, and pilgrims began to express their experiences in terms of water and blood (e. g. the blood of Christ is symbolized on the bloodied feet of pilgrims as they struggle on jagged penitential beds).

Lough Derg is both "modern" and "timeless." It blends ancient ritual and theology and 21st century technology. The Lough Derg website is technologically sophisticated, but pilgrims are expected to give up selected bits of their technology (cell phones) at least temporarily. As one pilgrim commented, "the requirement for pilgrims not to use phones and other electronic devices is perhaps the most significant means of disengaging from contemporary society. Not just leaving the mainland and leaving your technology behind, but there is something almost Medieval about it, in the sense of the bare feet, everything is so basic" (Noel, Male, 36–55 years, RC).

Some pilgrims' vlogs express what are essentially Medieval notions of sin and salvation/ Heaven and Hell. But most pilgrims express these ideas in modern terms (see Cunningham and Gillespie, 2004).

14 Unlike Medieval pilgrims, modern pilgrims articulate their visions (

fisi) of Heaven and Hell as direct experiences of the sacred. For Braga (2013), it is most significant that these experiences are not mediated by an institutional Church.

15

Again, Lough Derg is portrayed as both “modern” and “timeless.” Laura Shalvey (2003)

16 described Lough Derg as: "a bubble with its own rules, changeable and evolving and yet asserting its eternal nature. It is an archive of places and spaces, nestled together in ever-diminishing containers." More recently, pilgrim John Lynch

17 described his own impression of Lough Derg as a place "with its own vocabulary, culture and ethos." Lynch underscored the intensity of the ritual and emphasized that "there are no short cuts on this tiny island."

While many Lough Derg pilgrims see the site as "timeless," it is also a place of change. The most important changes relate to organizational structure. Since 1780, Lough Derg has been under the care of the Diocese of Clogher, and Priors to Lough Derg have been appointed -- and could be removed-- by the Clogher hierarchy. The Lough Derg Prior has ultimate responsibility for all pilgrimages and all facilities. Since 1780, the Prior has been directly accountable to the Diocese. Before the 20th century, Lough Derg’s Prior enjoyed considerable autonomy. Since then, the Diocese has taken a more active interest in Lough Derg (including the 3-day pilgrimage). Lough Derg is not “just another church.” Lough Derg is located near an ancient site that was/is believed to be above the entranceway to Hell. From this perspective, it is not seen as an ideal venue for casual visitors and/or youth retreats.

While the

locus of pilgrimage has changed (from cave, to island, to path, to cyberspace); the

duration 18 of pilgrimage has changed even more (from 3 days to one day, to an afternoon hike). Nevertheless, ritual and theology have remained very much the same (Butler, 1892; Richardson 1747).

19

Overall, pilgrimages to Lough Derg have become less intensive and now give greater attention to what Corin Braga calls fisi (ecstatic revelations of Christian eschatology) than to physical expeditions (i e. somanodias). But at some time, the focus may again shift back to somanodias.

While the general layout of the island is very much the same as a map drawn by John Richardson in 1747, the basilica has been expanded on pilings and additional dormitories have been built. As Reckwitz (2012)

20 correctly argued, "built architectural spaces are made for and correspond to specific practices." This has been especially true at Lough Derg. The construction of new dormitories and the expansion of the basilica dramatically altered the physical organization of space. These buildings increased the number of bodies accommodated; how these bodies could be gathered and/or separated one from another, and how close and/or distant they might be. With respect to

fisi and

somanodias, the island is a very different place than it was in 1747. Nevertheless, 18th and 19th century observers like Richardson and Butler would immediately recognize the theological continuity of Lough Derg.

As in past centuries, Lough Derg's theology is easy to grasp. Pilgrims' blogs and tweets reaffirm the vision of St. Patrick: "

When Patrick endeavored to convert the Irish people to Christianity by preaching to them of the happiness of heaven and the misery of hell, they turned a deaf ear to him, and said that they would never be converted by his words and miracles unless one of their number should be permitted to see with his own eyes the torments of the damned and the bliss of the saved. Upon this Our Lord appeared to him, and led him into a desert place, w

here He showed, him a certain round pit, dark within, and said, " Whatever man, being truly penitent, and armed with a lively faith, shall enter that pit, and there remain for a day and a night, shall be purged from all his sins, and going through it shall behold not only the torments of the lost but the joy of the blessed." (O‘Connor, 2012, 6).

21 For most pilgrims

, pilgrimage is praxis. If a pilgrim remains at the sacred site for a day and a night, he/she

will be purged of sin and

will receive blessings.

Pilgrims to Lough Derg do not offer detailed descriptions of Hell nor do they offer precise definitions of sin (O’Connor, 2012, 8).

22 This is to be expected since less than half of Irish adults say they believe in Hell.

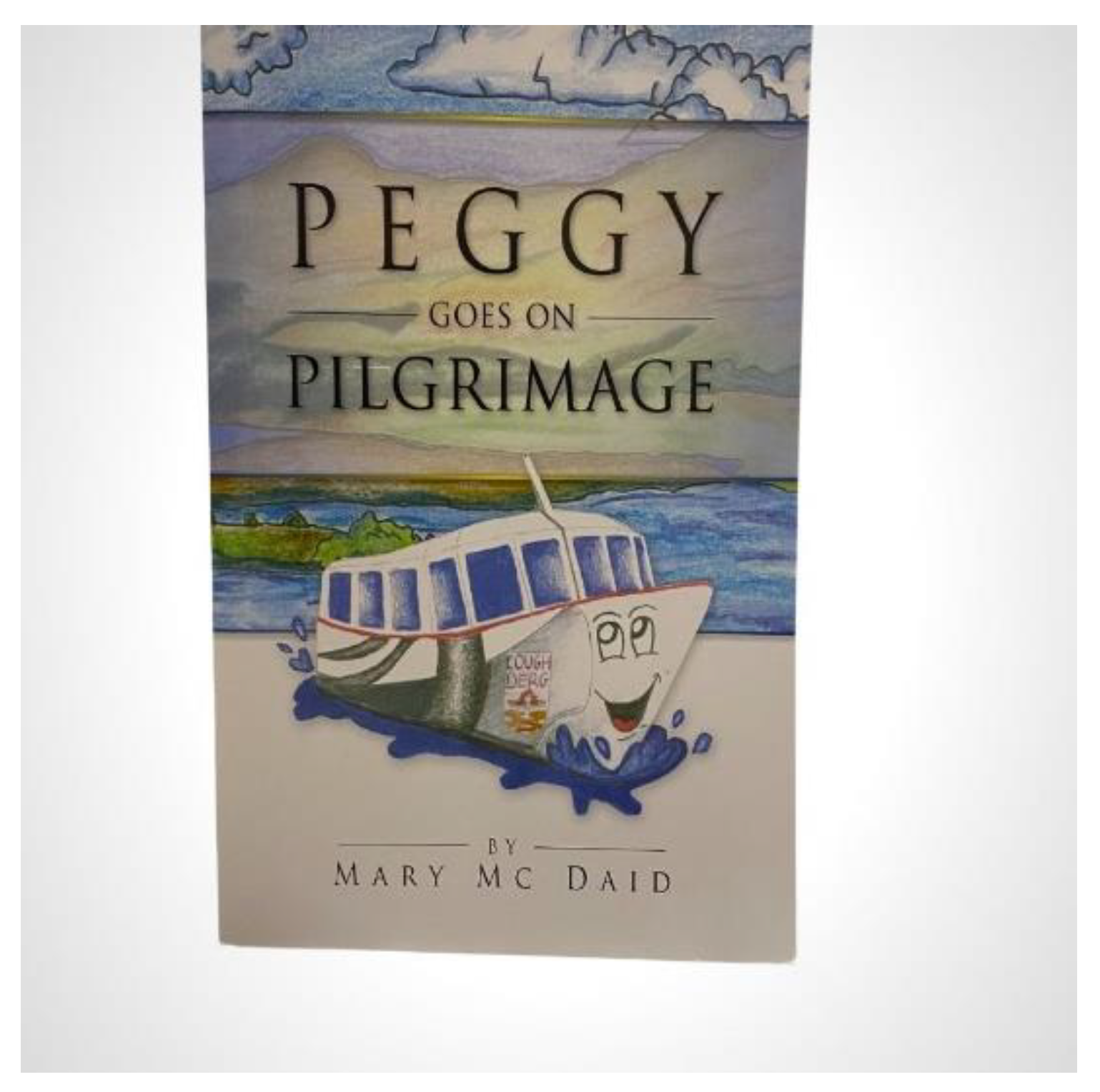

23 Lough Derg theology is perhaps best illustrated in a children's book -- "

Peggy Goes on Pilgrimage" -- available in the Lough Derg giftshop. The book's main characters are Peggy (a ferry boat) and the lake. The book's message: "Pilgrimage solves problems in your life."

Hillary Kaell (2016) reports one key characteristics of pilgrimages: “Pilgrims never fail" (Kaell, 2016). Pilgrims' vlogs express initial skepticism, but they usually end up supporting the rite. Pilgrims to Lough Derg return year after year. Clergy do not recognize mention "failed pilgrims.” If one sails to the island or walks the Pilgrims Path, he/she will receive blessings. This is true – even if their pilgrimage is not completed. Although it is not widely publicized, contemporary pilgrims may break from ritual and rest in dormitories. As long as they do not put on their shoes or utilize their cell phones, they are encouraged to resume pilgrimage later at their own pace. Prior LA Flynn and other clergy underscore the importance of intention. Any attempt at pilgrimage is always considered efficacious.

Lough Derg mediates – and transcends – numerous institutional contradictions. It is (and has been) an international pilgrimage site (Tingle 2020)

24 but 60-70% of pilgrims are local (Aubrey 2020).

25 Lough Derg is widely known as he "Ironman" of pilgrimages, but over 60 % of pilgrims are women (

ibid).

26 Its organizational structure is geared to once-yearly pilgrims, but over 30% of pilgrims are "first-timers." As noted, pilgrimages to Lough Derg were/are structured for individual pilgrims, but over 50% of pilgrims come as part of organized groups (McGrath, 1989).

27 Organized groups differ from individual pilgrims in that they negotiate their own time-frames (8 hours, 12 hours, 16 hours); negotiate their own penitential rounds (more time in the basilica; less time at the penitential beds); and get a lot more free time. Some groups are allowed to bring their own food. Nevertheless, the website stresses that conditions at the traditional 3-day pilgrimage (ritual sequence, duration, and food) are non-negotiable and – as noted – have not changed very much.

3. Responses to Covid 19: Virtual Pilgrimage and the Pilgrim Path

In 1826, over 15,000 pilgrims came to the Island. In 1845, 30,000 pilgrims came. By 1860, the number of pilgrims dropped to about 3000 where it remained for the 19th and 20th centuries. Between 2000 and 2016, about 2000-3000 pilgrims participated in the 3-day pilgrimage each year. The first group pilgrimage occurred in 1988. In 1992, One-Day pilgrimages began. The Pilgrim Path was refurbished in 2020 and in 2021. It was closed in March of 2020 due to Covid 19. It has been open since 2021 – but not daily. The Pilgrim Path is part of much longer trail around the lake’s parameter. Clergy control access to what they consider the main holy spots. They request paid reservations. Preference is for guided walks --some of which are conducted by Prior La Flynn himself. Parts of the Path are not open during the 3-day pilgrimage (July and August). Nor is it open between mid-November and mid-March (locals and hikers use the trail year- round). Most significantly, few contemporary pilgrims walk to Lough Derg. Walking – as Bouldrey, Montelongo, Prescott and Perez, Mendez and Marzan have all pointed out – is a central metaphor for pilgrimage.

By moving the site from the shoreline to Station Island, priests exerted greater control over pilgrims. Water facilitates movement -- but it is also a barrier. A major difference between Disney's Magic Kingdom in Florida and Disneyland in Anaheim is a ride on a ferry. Priests thereby control access, actions, numbers, and fares.

May 2020 marked the first virtual pilgrimage. Prior LA Flynn invited prospective pilgrims to complete a 3-Day virtual pilgrimage from "wherever you are." This virtual pilgrimage was intended for annual pilgrims, but it also attracted a limited number of "first-timers." 2020 was the first time since 1828 that summer pilgrimages at Lough Derg were suspended. Between 120 and 160 pilgrims participated in virtual pilgrimage. Most were repeat pilgrims.

Virtual pilgrimages are highly selective and controlled experiences – with some similarities to a Disney ride. The principle of synecdoche (= the extent to which a part stands for the whole) comes into play. Texts, places, and persons, through their different combinations, may help to reestablish sites of pilgrimage practice away from their original centers themselves, complicating the distinctions between “site” and "elsewhere." The major challenge of a virtual pilgrimage is to re-create the "affect" of Lough Derg on a computer screen. Of course, it is easier to re-create affect for return pilgrims than for the "first-timers." While it is possible to approximate some of the bodily sensations/movements in a virtual pilgrimage, it is much more difficult to replicate the emotional/affective/geographical sensibilities associated with the actual journey.

Over the past 40 years, Priors at Lough Derg have tried to make Lough Derg more accessible. In his daily blogs and tweets, Prior LA Flynn underscores the need to attract more diverse pilgrims to Lough Derg (geographically and religiously), including casual visitors and non-Catholics. To this end, he promotes ecumenical workshops and invites non-Catholics to the island. No pilgrims are required to divulge their religious affiliations.

To what extent does the virtual pilgrimages of 2020-2021 represent a radical departure from past practices and to what degree is it a continuation of changes implemented over the past two centuries? A major challenge of a virtual pilgrimage is to re-create the "affect" of Lough Derg on-line. As James L. Smith

28 noted, memory plays a key role in pilgrims' experiences. It is easier to re-create affect for return pilgrims than for "first-timers." While it may be possible to approximate some of the bodily sensations/movements in a virtual pilgrimage, it is much more difficult to replicate the emotional/affective/geographical sensibilities associated with an actual journey.

The Lough Derg website provided excerpts of a virtual on-line retreat

<https://loughderg.live/lough-derg-may-online-retreat-recording>. Virtual pilgrimages – like all pilgrimages at Lough Derg -- begin at the lake – a voyage from the lakeshore to Station Island. Prior to 1948, pilgrims were transported to the island by row boats. The trip took over an hour. Motorized ferries now make the journey in 15-20 minutes. However, virtual pilgrims in 2020 followed the pre-1948 schedule and spend nearly an hour on-line traveling the lake. The lake journey is conducted in “real time” with soft music in the background. None of the sounds that would accompany an actual motorized ferry trip are present. There is no narration.

After arrival, virtual pilgrims find themselves in the basilica where they hear hymns, listen to scripture readings, and hear a brief sermon. Virtual pilgrims then sprinkle themselves with Holy Water which they have obtained from their local churches or ordered on-line from Lough Derg. The shift to the first penitential bed is sudden. Virtual pilgrims do not visit all beds. What is included and what is left out? Virtual penitential beds appear as noisy and crowded as the actual beds. Pilgrims are constantly surrounded by "virtual" others (strangers). Unlike an actual pilgrimage, virtual pilgrims move abruptly from one penitential bed to the next. They do not control the pace of their experience (as in an actual pilgrimage).

4. Lough Derg as Experience: Fisi and Somanodias

Corin Braga (2019) emphasizes that the goals of visionary experiences have changed over time. Since the 18th century, there has been less emphasis on ecstasy (what Braga calls fisi -- eschatological revelations which take the form of psychanodias) than on physical bodily experience (somanadias). Modern visions, Braga contends, are anchored in bodily experience. They are not free flights of imagination (raptus animae). While scholars might quibble over some of Braga's distinctions (e. g. psychanadias and somanadiasa overlap), the focus of pilgrimage to Lough Derg has clearly moved from fisi to bodily experience. Can this bodily experience be duplicated virtually? How are such bodily experiences connected to place?

Lough Derg pilgrimage is an intense bodily experience. It incorporates all the senses: sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell. As a former Prior of Lough Derg, Monsignor Richard Mohan, posted: " It’s all about patterns and it’s all about movement … But, it’s the doing these things I think are important and it’s praying with the body."

In the 20th century, Lough Derg ritual focused almost exclusively on individual pilgrims. Pilgrims were crowded into tight spaces -- "alone, together." The ritual began – as now -- with repetition of the Hail Mary, Our Fathers, and the Apostles Creed at different times. Pilgrims moved from one penitential bed to another – each pilgrim moving at his or her own pace. There are an even number of beds, but an odd number of stations. Thus, individuals – then as now --were quickly separated from friends and would not see them again for many hours.

Lough Derg ritual is characterized by a cacophony of sounds. Some pilgrims pray aloud; others pray silently. Pilgrims are not expected to recite the Hail Mary, the Lord's Prayer, and the Apostle's Creed in unison. Friends are not encouraged to stay together. Seating at meals and bed assignments are random. As noted, pilgrims are not supposed to not converse with one another.

Ritual centers on seven penitential beds: St Brigid’s, St Brendan’s, St Catherine’s, St Columba’s, St Patrick’s and Saints Davog and Molaise’s (the latter two are double beds). At each bed, pilgrims walk three times around the outside, clockwise, while saying three Our Fathers, three Hail Marys, and one Creed; kneel at the entrance to each bed and repeat the prayers; walk three times around the inside saying the prayers again; and, finally, kneel at the cross at the center and recite prayers for a fourth time. Pilgrims then retreat to the basilica for an all-night vigil; retire briefly to dormitories; and repeat prayers and recitations the following day.

Lough Derg is experienced viscerally (Skoggard and Waterston, 2015).

29 The Lough Derg experience consists of a barrage of sounds, sights, smells, and bodily sensations. All pilgrims to Lough Derg

must remove their shoes.

Peter Tiernan highlights the smell and sight of feet: "Lough Derg is a great place to study feet; all shapes and sizes. As the rounds of the 'beds' are made, it is impossible not to notice feet as they curl and twitch over sharp and often wet stones."

30 The blood of Christ is remembered on the bloodied feet of pilgrims as they struggle on the sharp stones of penitential beds. In the nineteenth century, William Carleton (1844) documented sectarian conflict at the site.

31 He claimed that disdain for Lough Derg exhibited by his Protestant co-religionists resulted from the site’s "failure to attract positive affect." He posited a negative relationship between affects, sectarianism, and geographical isolation. Religious affects and emotions, he asserted, "failed" due to the isolated environment. Isolated environments "degrade and pollute" religious affects. Carleton does not speculate on how or why this may have occurred.

5. Water, Affect and the Remoteness of Place

James L. Smith (2019)

32 contended that the isolation of Lough Derg within County Donegal and its "great distance" (about 1/2 mile) from the shore are fundamental components of its rural (spiritual) geography. He explores water's role in influencing community responses to place and documents ways in which Catholic and Protestant narratives of place have shaped Lough Derg in the 21st century.

Post-1780, lake water became a powerful symbol of pilgrimage. The most prominent decorations in the basilica at Lough Derg are fonts containing Holy water. Replicas of these fonts are among the best-selling items at the Lough Derg gift shop. Smith underscores connections between water and purification. Just as Lough Derg pilgrims draw power from repetition -- stations, circuits, rosaries, prayers – the lake's ebb and flow of water "remembers that power in its hydro-social and socio-ecological arrangements." Water facilitates isolation. It is a physical and an ontological boundary – separating the everyday from the extraordinary. Richard Scriven (2014)

33 further suggests that it is the position of Station Island on the water of Lough Derg that gives it its transformative power. Water both separates and unifies.

Ireland has long seen itself as being a place at the "edge" of the earth, and within Ireland, Donegal has been -- and still sees itself as -- the "edge" of that edge. Remoteness is a physical/geographical condition, but it is also an affective/emotional state. The area surrounding Lough Derg has long been associated with low population, a lack of commercial development, and the absence of intensive agriculture. While Protestants have seen such underdevelopment as "folly," local Catholics see underdevelopment as a badge of virtue – what Laurence Taylor (1995)

34 described as the region's "moral geography." Alice Curtayne (1944)

35 contended that Lough Derg is "

a time machine for the re-experience of an earlier and more austere form of wilderness devotion, the heart of which is to embark on a mountain-locked lake that is just as secluded to-day as when Saint Patrick was attracted to its solitude." She argues, incorrectly, that the physical features of the landscape have remained practically unaltered through the centuries. As Prior LA Flynn expressed it: " I intend to seek the way for Lough Derg to move ahead in a missionary key, reaching out from a place that is geographically ‘on the margins’ to offer a welcome to those who feel themselves to be ‘on the margins’, and spiritual accompaniment to all who hear the call to be a pilgrim and who come our way as part of their journey.” But Lough Derg is no longer that remote and its "moral geography" is becoming more difficult to maintain. Nowhere in Ireland is truly isolated.

6. Isolation, Nationalism and “Moral Geography”: A Critique of Smith

Contemporary pilgrims travel to religious sites with varied expectations and myriad motives. James L. Smith (2016) – like the Turners (1978) – portrayed Lough Derg as a dominant symbol of Irish nationalism. But Lough Derg is (and has always been) an international destination. Most pilgrims are still Irish Catholics, but – as in the past (Butler, Richardson) – Protestants from Ulster are also welcomed by Prior LA Flynn and his predecessors. Muslims and Hindus also make the journey.

Access to Station Island is (and has always been) strictly regulated. Advanced reservations are required for most visitors – even to walk the Pilgrim Path (which not encouraged during pilgrimage season). Fewer pilgrims walk to the site. Most post-covid pilgrims travel by public transportation and are part of an organized group. Bus service to Lough Derg is readily available during the summer. There is daily bus service from Dublin to Lough Derg, but --unlike Knock or St. Fechin, it is not possible to make a return trip from Dublin to Lough Derg on the same day. James L. Smith equates Lough Derg’s isolation with its “moral geography.” But this equation is being challenged as the area has become less isolated. As noted, the surrounding area is being developed as a tourist destination.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Edmund Leach, in Political Systems of Highland Burma, discovered that social and political systems can change dramatically over time. It depends on when a particular observer happens to be there. Systems are in constant flux and vary depending on the time of research. With respect to Lough Derg, the focus on experience rather than place (exacerbated by covid-19) is subject to change.

William H. Swatos Jr. (2006) perceptively pointed out that in the case of pilgrimages, “theory seems to have worked well ahead of data.” (Swatos, viii). He also noted that contemporary pilgrimages “change so fast that theory often struggles to keep up.” Some pilgrimages are not primarily focused on sites (that is: buildings, statues, etc.) but on travel through space. Participants in Celtic pilgrimages, for example, “walked the walk” of Celtic saints. Spiritual Baptist pilgrims are more concerned with the journey than the destination.

36.

The original cave site (St Patrick’s Purgatory) was restricted, but it was still relatively accessible. Station Island – which is now only accessible by ferry and regulated by clerics – is considerably less accessible than the original cave site.

Lough Derg pilgrims are "alone together." Brian D. Bouldrey aptly compares pilgrims to members of an art colony: "Being alone but craving community." Pilgrims are not just "betwixt and between" (as the Turners argued) but also seeking connections. Perhaps this the most difficult component of pilgrimage to recreate virtually its “missing essence."

As noted, Lough Derg's theology is practical. Pilgrims' vlogs and tweets cite Patrick’s experience: "When Patrick endeavored to convert the Irish people to Christianity by preaching to them of the happiness of heaven and the misery of hell, they turned a deaf ear to him, and said that they would never be converted by his words and miracles, .unless one of their number should be permitted to see with his own eyes the torments of the damned and the bliss of the saved. Upon this Our Lord appeared to him, and led him into a desert place, where He showed, him a certain round pit, dark within, and said, " Whatever man, being truly penitent, and armed with a lively faith, shall enter that pit, and there remain for a day and a night, shall be purged from all his sins, and going through it shall behold not only the torments of the lost but the joy of the blessed."

Lutz Kaelber (2006) examined the intersection between real and virtual pilgrimages, including what he saw as the somewhat unsettling topic of ‘dark’ pilgrimage (and/or tourism). Kaelber contended that virtual pilgrimages have a long history connected to the major faith traditions (see Swatos,2006: xiv).

Kaelber (2006)

37 points particularly to the

Sionpilger of the late-fifteenth-century friar Felix Schmidt (perhaps better known under the Latinized Felix Fabri). The

Sionpilger was, in a sense, a ‘virtual pilgrimage’ – a book about the Holy Land written primarily for nuns, who were not allowed to make a ‘real’ pilgrimage (Swatos, xiv).

Computer simulations can take virtual pilgrimage to new heights—and, as Lutz points out— to new depths as well (Swatos, xv; Kaelber, 2006, p. 278). Pilgrimage and religious tourism are at the intersection of new means of mass communication such as the Internet and the subsequent proliferation of virtual texts such as online travel accounts, weblogs, and Internet sites which evaluate and rate travel destinations, and the diversification of the motives of travelers to traditionally religious sites.

Lough Derg virtual pilgrimages are highly selective. The principle of synecdoche, the extent to which a part stands for the whole, frequently comes into play. Eade and Sallnow (2000 [1991]) suggested that “texts, places, and persons are deeply interwoven, signifying and shaping pilgrims’ motives, movement, perceptions, and experiences. Texts, places, and persons, through their different combinations, may help to reestablish sites of pilgrimage practice away original centers themselves, complicating the distinctions between “site” and elsewhere.”

Virtual pilgrimage to Lough Derg may supplement rather than substitute for the physical journey. As Coleman and Elsner (1995) have pointed out, “sites offer religious experiences that do not rely exclusively on textual knowledge” (p. 208). Pilgrimage and the way it is experienced are influenced by the materiality of pilgrimage sites.

Perhaps the best way to conclude is by providing an argument of images:

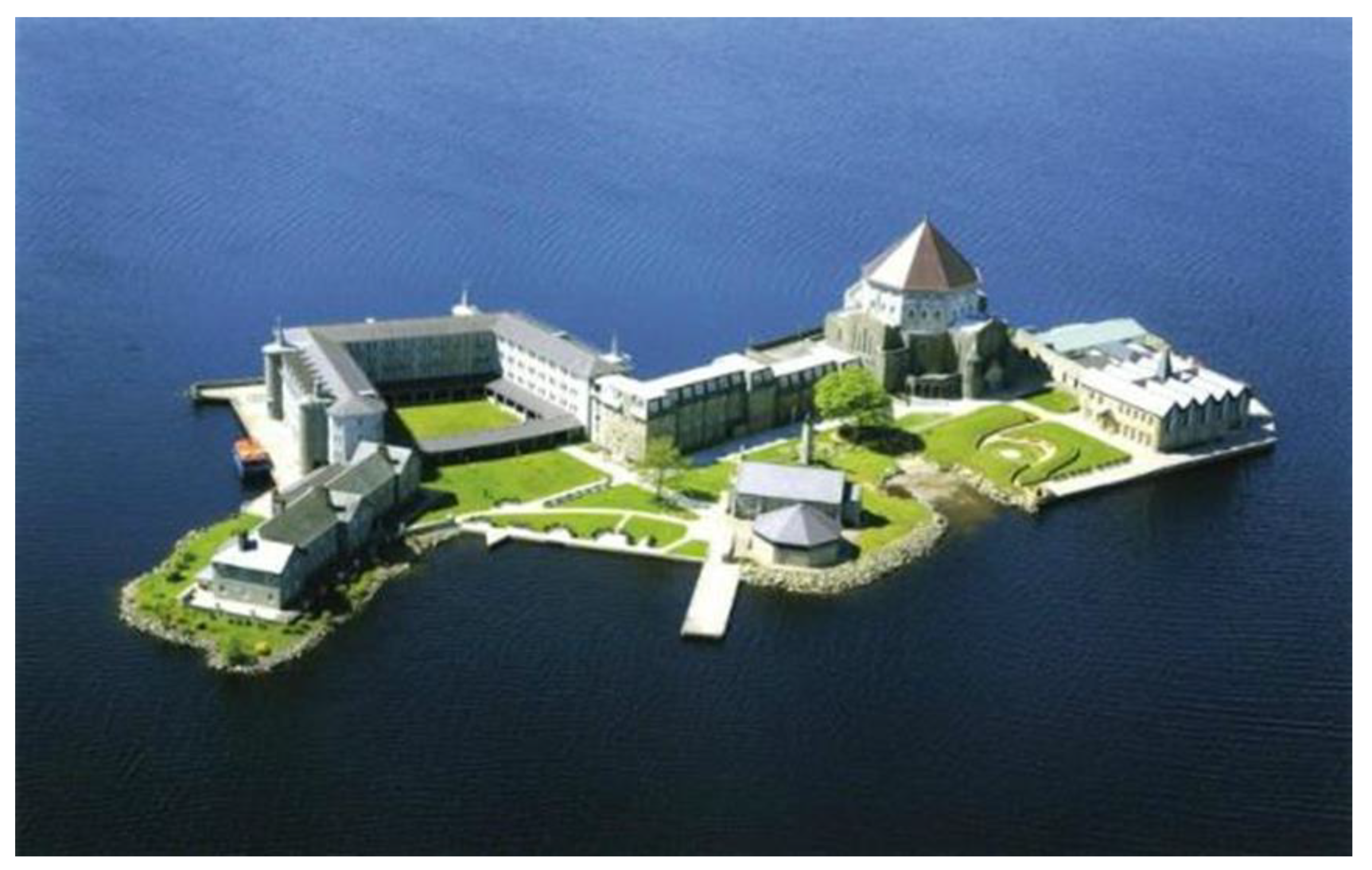

Figure 1.

Lake water is a powerful symbol of the pilgrimage. The most prominent decorations in the basilica at Lough Derg are fonts containing Holy water. Replicas of these fonts are among the best-selling items at the Lough Derg gift shop. Just as Lough Derg pilgrims draw power from repetition -- stations, circuits, rosaries, prayers – the lake's ebb and flow of water "remembers that power in its hydro-social and socio-ecological arrangements." The position of Station Island on the water of Lough Derg that gives it its transformative power. Participants in cyber pilgrimage were provided with holy water from the lake. The first hour of virtual pilgrimage replicates the voyage from shoreline to Station Island in "real time" (about 40 minutes). .

Figure 1.

Lake water is a powerful symbol of the pilgrimage. The most prominent decorations in the basilica at Lough Derg are fonts containing Holy water. Replicas of these fonts are among the best-selling items at the Lough Derg gift shop. Just as Lough Derg pilgrims draw power from repetition -- stations, circuits, rosaries, prayers – the lake's ebb and flow of water "remembers that power in its hydro-social and socio-ecological arrangements." The position of Station Island on the water of Lough Derg that gives it its transformative power. Participants in cyber pilgrimage were provided with holy water from the lake. The first hour of virtual pilgrimage replicates the voyage from shoreline to Station Island in "real time" (about 40 minutes). .

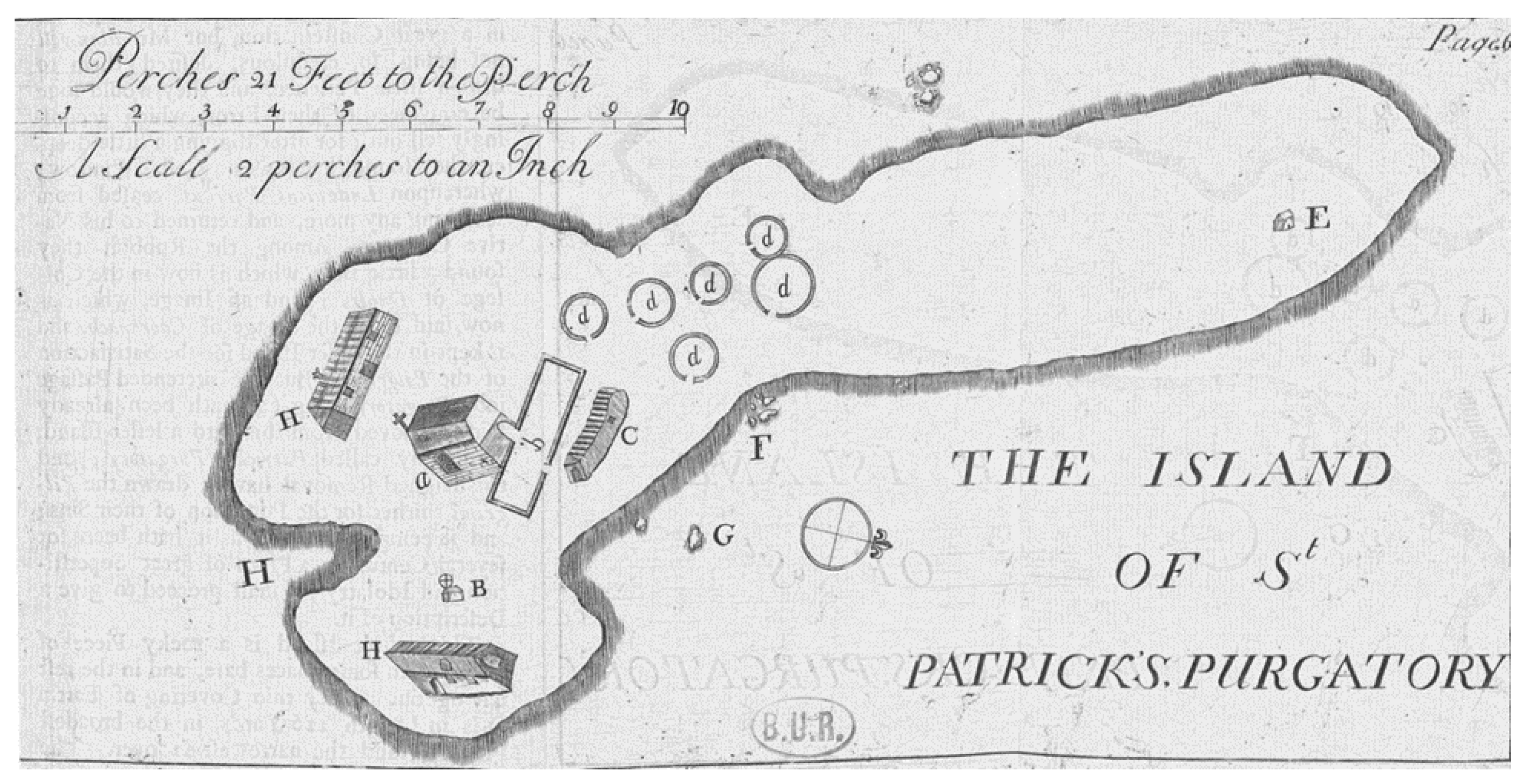

Figure 2.

The general physical layout of the Island is very much the same as the map drawn by John Richardson in 1747, the basilica has been expanded on pilings and new dormitories have been built. As Reckwitz (2016) correctly argued, architecture is a special type of technology and "built architectural spaces are made for and correspond to specific practices.".

Figure 2.

The general physical layout of the Island is very much the same as the map drawn by John Richardson in 1747, the basilica has been expanded on pilings and new dormitories have been built. As Reckwitz (2016) correctly argued, architecture is a special type of technology and "built architectural spaces are made for and correspond to specific practices.".

Figure 3.

Lough Derg theology is perhaps best illustrated in a children's book -- "Peggy Goes on Pilgrimage" -- available in the Lough Derg giftshop. The book's main characters are Peggy (a ferry boat) and the lake. The book's message: "Pilgrimage solves the problems in your life.".

Figure 3.

Lough Derg theology is perhaps best illustrated in a children's book -- "Peggy Goes on Pilgrimage" -- available in the Lough Derg giftshop. The book's main characters are Peggy (a ferry boat) and the lake. The book's message: "Pilgrimage solves the problems in your life.".

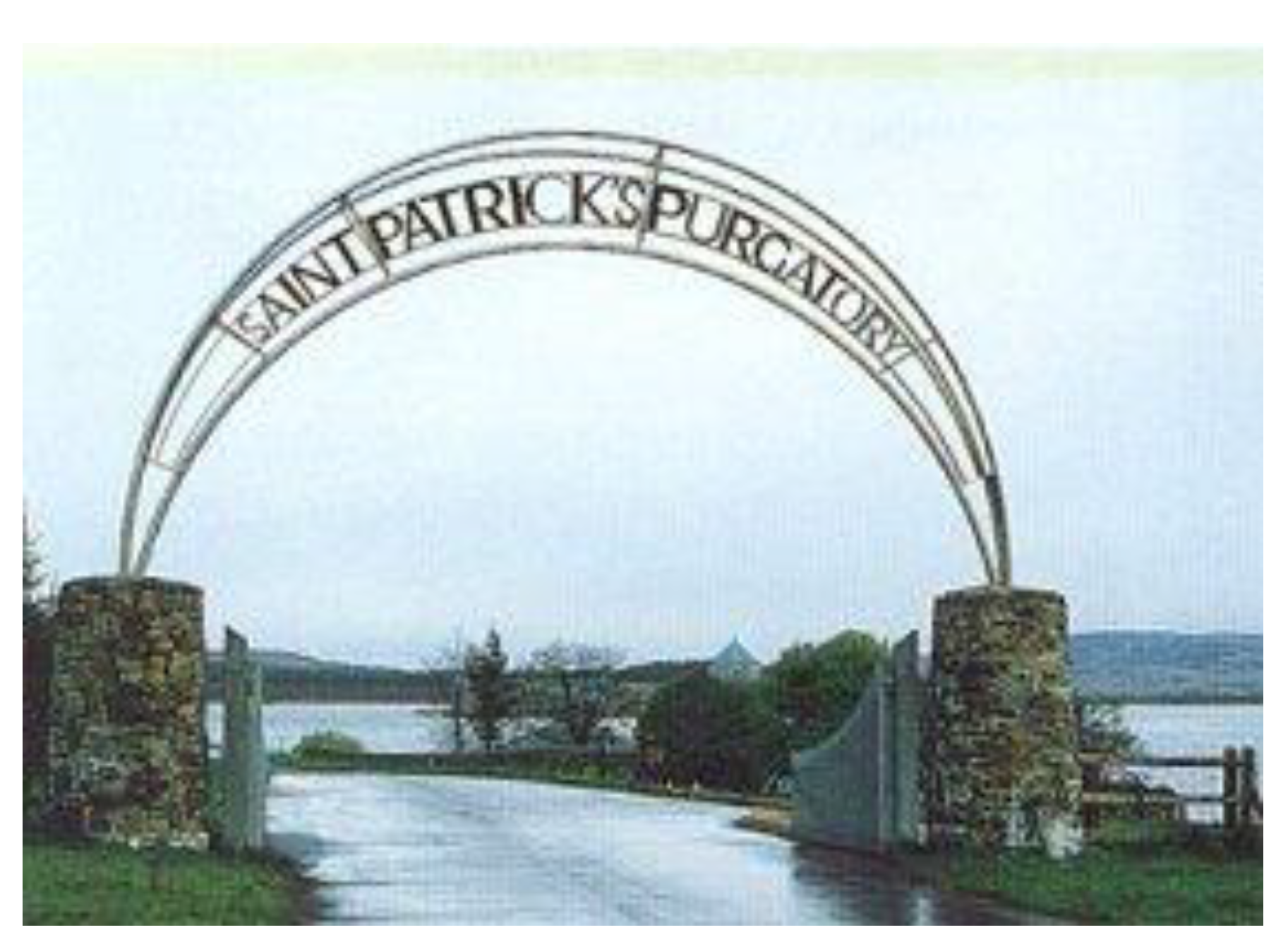

Figure 4.

As noted, water is a powerful symbol of the pilgrimage. The most prominent decorations in the basilica at Lough Derg are fonts containing Holy water. Replicas of these fonts are among the best-selling items at the Lough Derg gift shop. Just as Lough Derg pilgrims draw power from repetition -- stations, circuits, rosaries, prayers – the lake's ebb and flow of water "remembers that power in its hydro-social and socio-ecological arrangements." Participants in cyber pilgrimage were provided with holy water from the lake. The first hour of virtual pilgrimage replicates the voyage from shoreline to Station Island in "real time" (about 40 minutes). .

Figure 4.

As noted, water is a powerful symbol of the pilgrimage. The most prominent decorations in the basilica at Lough Derg are fonts containing Holy water. Replicas of these fonts are among the best-selling items at the Lough Derg gift shop. Just as Lough Derg pilgrims draw power from repetition -- stations, circuits, rosaries, prayers – the lake's ebb and flow of water "remembers that power in its hydro-social and socio-ecological arrangements." Participants in cyber pilgrimage were provided with holy water from the lake. The first hour of virtual pilgrimage replicates the voyage from shoreline to Station Island in "real time" (about 40 minutes). .

Figure 5.

As noted, Lough Derg pilgrimages focus on seven penitential beds: St Brigid’s, St Brendan’s, St Catherine’s, St Columba’s, St Patrick’s and Saints Davog and Molaise’s (the latter two are double beds). At each bed, pilgrims walk three times around the outside, clockwise, while saying three Our Fathers, three Hail Marys, and one Creed; kneel at the entrance to each bed and repeat the prayers; walk three times around the inside saying the prayers again; and, finally, kneel at the cross at the center and recite prayers for a fourth time. Pilgrims then retreat to the basilica for an all-night vigil; retire briefly to dormitories; and repeat prayers and recitations the following day.

Figure 5.

As noted, Lough Derg pilgrimages focus on seven penitential beds: St Brigid’s, St Brendan’s, St Catherine’s, St Columba’s, St Patrick’s and Saints Davog and Molaise’s (the latter two are double beds). At each bed, pilgrims walk three times around the outside, clockwise, while saying three Our Fathers, three Hail Marys, and one Creed; kneel at the entrance to each bed and repeat the prayers; walk three times around the inside saying the prayers again; and, finally, kneel at the cross at the center and recite prayers for a fourth time. Pilgrims then retreat to the basilica for an all-night vigil; retire briefly to dormitories; and repeat prayers and recitations the following day.

Figure 1:

Bus services Dublin-Lough Derg run four days a week during pilgrimage season. It is possible to travel directly to Lough Derg from Dublin airport. It is not possible, however, to make a round trip on the same day.

Valid 3rd June to 15th August 2022

Dublin – Cavan - Enniskillen - Lough Derg

Friday, Saturday, Sunday & Monday

Location Depart Arrive NOTE

Dublin (Bus Aras) 09.30

Bus Eireann

Dublin – Airport – Cavan - Donegal Express

Service Number 30

Dublin Airport (Atrium Rd, Zone 10) 09.50

Virginia (Main Street) 10.55

Cavan Town (Bus Station) 11.25

Cavan Town (Bus Station) 11.35

Butlersbridge 11.42

Belturbet (Post Office) 11.52

Derrylin (opp Market Square) 12.05

Bellanaleck (Northbound Stop) 12.17

Enniskillen Bus Station 12.25

Enniskillen Bus Station 13.00 Bus Eireann Lough Derg Services

Lough Derg 14.05 Service No 486*

Lough Derg – Enniskillen – Cavan - Dublin

Friday, Saturday, Sunday & Monday

Location Depart Arrive NOTE

Lough Derg 11.00

Bus Eireann Lough Derg Services

Service No 486*

Pettigo 11.10

Pettigo 11.15

Enniskillen Bus Station 12.20

Enniskillen Bus Station 12.35

Bus Eireann

Donegal – Cavan – Airport – Dublin Express

Service Number 30

Cavan Town (Bus Station) 13.25

Cavan Town (Bus Station) 13.35

Virginia (Main Street) 14.05

Dublin Airport (Atrium Rd, Zone 10) 15.10

Dublin (Bus Aras) 15.30

NOTE:

*Bus Eireann Shuttle Bus Service No 486 operates Friday to Monday inclusive

The best option for using this Shuttle Bus service is to:

Arrive Lough Derg Friday – Depart Sunday

or arrive Lough Derg Saturday – Depart Monday

If you arrive using this service on a Sunday or Monday there is no return service on Tuesday or Wednesday to Enniskillen

FARES: (subject to change)

Busaras, Dublin / Enniskillen €21.00 Single €32.00 Return

Enniskillen / Lough Derg €12.00 Single €21.00 Return

Free Travel Passes are valid on all Bus Eireann services.

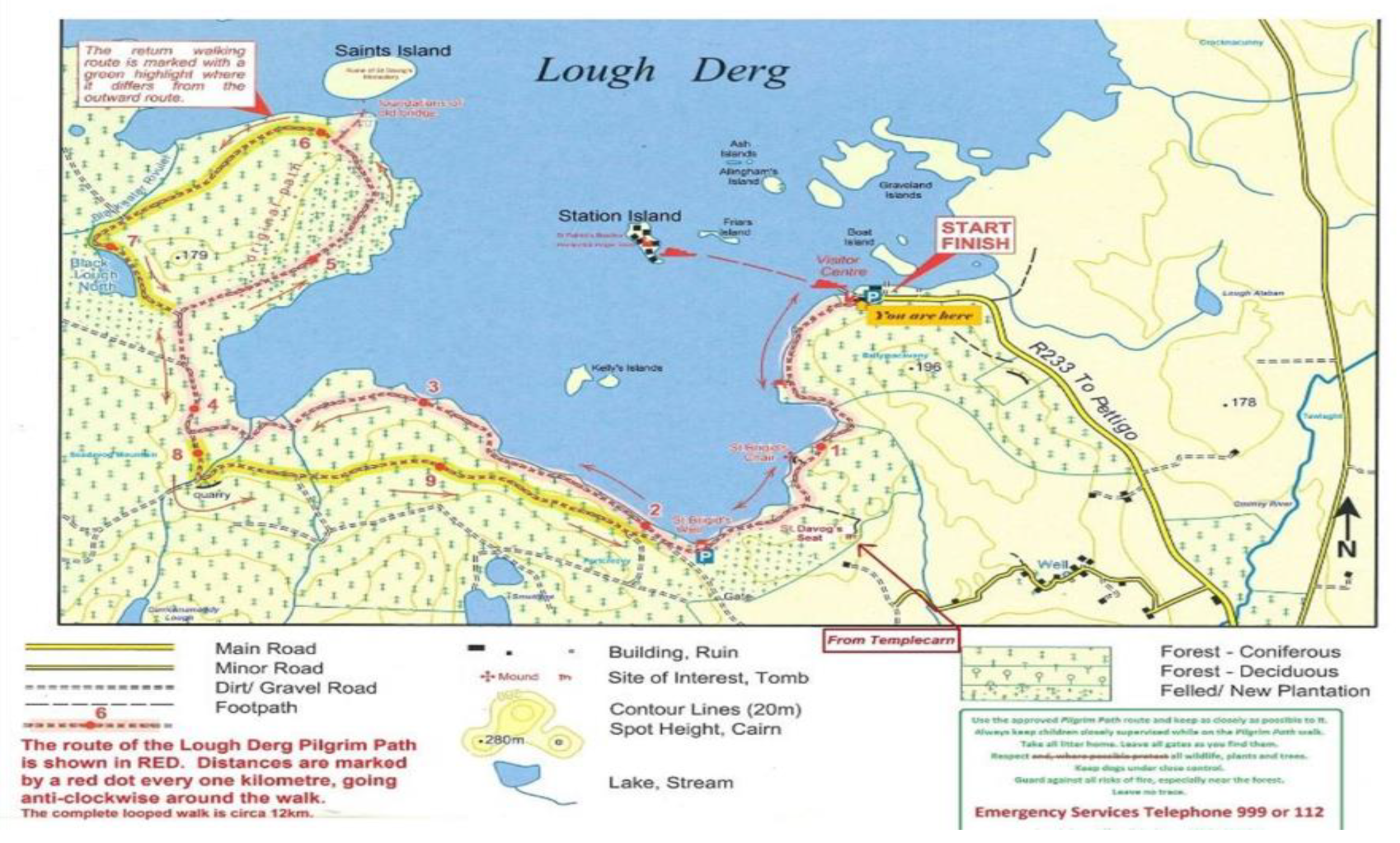

Figure 6.

The Pilgrim Path created in 1997 by kind co-operation with the Heritage Council and Coillte Teoranta, the state forestry service, on lands that belong to them. In 2014 it became part of “Pilgrim Paths Ireland,” a network of 12 traditional pilgrim routes scattered across the island of Ireland. After the first 2 km, it follows a pilgrim way that was used in the Middle Ages by pilgrims to St Patrick’s Purgatory. The latest Pilgrim Path begins and ends at the Visitor Centre at the lakeshore at Lough Derg. The path is marked by black recycled plastic markers, recognizable by the yellow Pilgrim Symbol, with arrows showing the direction to be taken. There is no plastic marker at the former cave site.

Figure 6.

The Pilgrim Path created in 1997 by kind co-operation with the Heritage Council and Coillte Teoranta, the state forestry service, on lands that belong to them. In 2014 it became part of “Pilgrim Paths Ireland,” a network of 12 traditional pilgrim routes scattered across the island of Ireland. After the first 2 km, it follows a pilgrim way that was used in the Middle Ages by pilgrims to St Patrick’s Purgatory. The latest Pilgrim Path begins and ends at the Visitor Centre at the lakeshore at Lough Derg. The path is marked by black recycled plastic markers, recognizable by the yellow Pilgrim Symbol, with arrows showing the direction to be taken. There is no plastic marker at the former cave site.

Figure 7.

June 2020 marked the first virtual pilgrimage. Prior La Flynn invited prospective pilgrims to complete a 3-Day virtual pilgrimage from "wherever you are." This virtual pilgrimage was intended for annual pilgrims, but it also attracted a limited number of "first-timers." According to La Flynn, 2020 was the first time since 1828 that summer pilgrimages at Lough Derg were suspended. In 2021, Virtual Pilgrimage was replaced by The Pilgrim Path. The Pilgrim Path, originally established in 1997, was designed to follow a typical pilgrim’s way used in the Middle Ages by pilgrims to St Patrick’s Purgatory. Pilgrims came from as far away as Spain, Italy, and Hungary.

Figure 7.

June 2020 marked the first virtual pilgrimage. Prior La Flynn invited prospective pilgrims to complete a 3-Day virtual pilgrimage from "wherever you are." This virtual pilgrimage was intended for annual pilgrims, but it also attracted a limited number of "first-timers." According to La Flynn, 2020 was the first time since 1828 that summer pilgrimages at Lough Derg were suspended. In 2021, Virtual Pilgrimage was replaced by The Pilgrim Path. The Pilgrim Path, originally established in 1997, was designed to follow a typical pilgrim’s way used in the Middle Ages by pilgrims to St Patrick’s Purgatory. Pilgrims came from as far away as Spain, Italy, and Hungary.

References

-

Traveling Souls: Contemporary Pilgrimage Stories; Bouldrey, B.D., Ed.; Whereabouts Press: location, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C. Fisi vs. journeys into St. Patrick's purgatory: Irish psychanodias and somanodias. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 2013, 12, 180–227. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, I. A Journey to Lough Derg. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 1892, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, W. Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry; W. Curry, Jr. and Co: Dublin, 1843. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, D.J. Lough Derg's Infamous Pilgrim. Clogher Record 1971, 7, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Elsner, J. (Eds.) Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, B.; Gillespie, R. The Lough Derg Pilgrimage in the Age of the Counter-Reformation. Éire-Ireland 2004, 39, 167–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtayne, A. Lough Derg: St. Patrick’s Purgatory; Burns Oates & Washbourne: London & Dublin, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Dewsnap, T. Island of Daemons: The Lough Derg Pilgrimage and the Poets Patrick Kavanagh, Denis Devlin and Seamus Heaney; University of Delaware Press: Newark, NJ, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, J.; Sallnow, M.J. (Eds.) Contesting the Sacred: The Anthropology of Christian Pilgrimage; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, E. The Pilgrim's Way to St. Patrick's Purgatory; Italica Press: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gierek, B. Nonverbal Communication in Rituals on Irish Pilgrimage Routes. Religions 2022, 13, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogarty, T.R. Some pilgrim impressions of Lough Derg. The Catholic Bulletin 1913, 3, 800–881. [Google Scholar]

- Kaell, H. Can Pilgrimage Fail? Intent, Efficacy, and Evangelical Trips to the Holy Land. Journal of Contemporary Religion 2016, 31, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, E.R. (Edmund Ronald). Political systems of highland Burma: a study of Kachin social structure; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelber, L. 2006. Place and Pilgrimage, Real and Imagined. In On the Road to Being There: Studies in Pilgrimage and Tourism in Late Modernity; Swatos, W.H., Jr., Ed., pp. 277–295. E. J. Brill. [CrossRef]

- Maddrell, A.; Scriven, R. Celtic Pilgrimage, Past and Present: From Historical Geography to Contemporary Embodied Practices. Social & Cultural Geography 2016, 17, 300–321. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, F. Characteristics of Pilgrims to Lough Derg. Irish Geography 1989, 22, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.L. Irish Pilgrimage: The Different Tradition. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 1983, 73, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, A. To Hell or to Purgatory? Irish Folk Religion and Post-Tridentine Counter-Reformation Catholic Teachings. Béaloideas 2012, 80, 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pasulka, D.W. When Purgatory Was a Place on Earth: The Purgatory Cave on The Red Lake in Ireland. [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. The Origin of Ireland’s Holy Wells; Archaeopress: Oxford, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, A. Affective spaces: a praxeological outlook. Rethinking History 2012, 16, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. The Great Folly, superstition and idolatry of Pilgrimages in Ireland, especialy of that to St. Patrick’s Purgatory: together with an account of the loss that the publick sustaineth thereby, truly and impartially represented; J. Hyde: Dublin, 1747. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, M. Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (and Is That What Makes Them Have a History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion. History and Theory 2012, 51, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, R. Geographies of Pilgrimage: Meaningful Movements and Embodied Mobilities. Geography Compass 2014, 8, 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, R. Ireland. In Spaces of Spirituality; Bartolini, N., MacKian, S., Pile, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, 2018; pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoggard, I.; Waterston, A. Introduction: Toward an Anthropology of Affect and Evocative Ethnography. Anthropology of Consciousness 2015, 26, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L. Rural Waterscape and Emotional Sectarianism in Accounts of Lough Derg, County Donegal. Rural Landscapes: Society, Environment, History 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swatos, W.H., Jr. Introduction. In On the Road to Being There: Studies in Pilgrimage and Tourism in Late Modernity; Swatos, W.H., Jr., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Eds.; E. J. Brill: Leiden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L. Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tingle, E. Sacred Journeys in the Counter-Reformation; De Gruyter: Boston, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W.; Turner, E.L.B. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture; Columbia University Press: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, H. Christian theologies of pilgrimage. In Christian Pilgrimage, Landscape and Heritage; Maddrell, A., della Dora, V., Sacfi, A., Walton, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski, C.G. St. Patrick's Purgatory: Pilgrimage Motifs in a Medieval Otherworld Vision. Journal of the History of Ideas 1985, 46, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdars-Swartz, S.L. Bodies in motion: Pilgrims, seers, and religious experience at Marian apparition sites. Journeys 2012, 13, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Notes

| 1 |

Edith L. B. Turner and Victor W. Turner ( pp. 108-110; 123-137). The Turners saw the Lough Derg pilgrimage in terms of communitas – a relaxation of social barriers. In many respects, this is accurate. Lough Derg is indeed a "levelling experience." All pay the same price (rates have posted since the 1930s). All pilgrims are treated the same: same access; same food; same levels of assistance. On the other hand, 3-day pilgrimages stress individuality. Pilgrims are "alone together." Pilgrims "lose themselves" in the ritual. Their experience may have more in common with Emile Durkheim's (1912) formulation of "group euphoria" than Arnold van Gennep's (1908) idea of "liminality." |

| 2 |

According to Trip Advisor, "St Patrick's purgatory or Lough Derg is a unique pilgrimage experience which is not for the faint hearted. Consisting of 3 days of fasting, 24 hours without sleep and 48 hours in bare feet, one would wonder why people come year after year?" https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g1067518-d3256511-Reviews-St_Patrick_s...

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

Hillary Kaell (2016) Can Pilgrimage Fail? Intent, Efficacy, and Evangelical Trips to the Holy Land, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 31:3, 393-408, DOI: 10.1080/13537903.2016.1206254. |

| 5 |

Stephen D. Glazier. 1991. Marchin’ the Pilgrims Home: A Study of the Spiritual Baptists of Trinidad. Salem, WI: Sheffield Press. |

| 6 |

William Carleton. 1844. ‘The Lough Derg Pilgrim’, in Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry Vol. III [1st ed. 1830; definitive edition 1843-44]. New York: Collier. |

| 7 |

See also. Casey, Daniel J. “Lough Derg's Infamous Pilgrim.” Clogher Record, vol. 7, no. 3, 1971, pp. 449–479. www.jstor.org/stable/27695662. Casey contends that Carleton produced an exaggerated comedic account of the Lough Derg pilgrimage -- yet he also captured the "spirit" of pilgrims making the journey to Lough Derg. |

| 8 |

The 3-day pilgrimage has been the island's major source of revenue. Lough Derg is self-supporting. Building maintenance is the major expense. Most helpers are unpaid. The Prior and other priests draw no salary. An annual lottery ("the draw") is promoted to prior pilgrims. The Lough Derg "draw" does not compete with lotteries run by local parishes. The giftshop is open mainly for pilgrims. As noted, there is a very small on-line selection of books, rosaries, hats, and decorative items – many of which are sold at cost. |

| 9 |

Nolan, Mary L. "Irish Pilgrimage: The Different Tradition." Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 73, no. 3, 1983, pp. 421-438. |

| 10 |

Zaleski, Carol G. “St. Patrick's Purgatory: Pilgrimage Motifs in a Medieval Otherworld Vision.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 46, no. 4, 1985, pp. 467–485. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2709540

|

| 11 |

Taylor, Lawrence. 1995. Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. There are natural caves in the Donegal area (e. g. Marble Arch caves). The cave at Lough Derg may have been of human manufacture. |

| 12 |

The indulgence was given once, for all time – yet many pilgrims return year after year. |

| 13 |

Sacred wells are associated with healing. In Ireland: there are wells for taking away warts; wells for healing sore eyes, and a famous well in Gleann na Gealt in Kerry, which helps cure depression. The water at Gleann na Gealt contains high levels of lithium -- a natural anti-depressant. |

| 14 |

Cunningham, B., & Gillespie, R. 2004. The Lough Derg Pilgrimage in the Age of the Counter-Reformation . Éire-Ireland, 39(3), 167–79. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/eir.2004.0019. Changing Catholic religious sensibilities, termed the Catholic Reformation or the Counter-Reformation, placed increasing emphasis on interior piety at the expense of external practice. |

| 15 |

Braga, Corin. (2013) "Fisi vs. journeys into St. Patrick's purgatory: Irish psychanodias and somanodias." Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, vol. 12, no. 36, 2013, p. 180- 227. |

| 16 |

Shalvey, Laura Brigid. 2003. “Continuity through Change: A Study of the Pilgrimage to Lough Derg In the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” MA diss., NUI Maynooth. |

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

In the past, the pilgrimage has been as long as nine or even fifteen, days, as is alleged in the story of Knight Owein. |

| 19 |

Butler, Isaac. "A Journey to Lough Derg." The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, 2, no. 1 (1892): 13-24; Richardson, Rev. John. 1747. The great folly, superstition and idolatry of pilgrimage in Ireland (Dublin). |

| 20 |

A. Reckwitz. 2012. "Affective spaces: a praxeological outlook." Rethinking History 16 (2): 241-258. |

| 21 |

SAINT PATRICK'S PURGATORY: A MEDLEVAL PILGRIMAGE IN IRELAND. by. JOHN D. SEYMOUR, B.D. W. TEMPEST, DUNDALK: DUNDALGAN PRESS, 1918. |

| 22 |

O'Connor, Anne. “To Hell or to Purgatory? Irish Folk Religion and Post-Tridentine Counter-Reformation Catholic Teachings.” Béaloideas, vol. 80, 2012, pp. 115–141. |

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

Lough Derg is said to be the oldest pilgrimage site in Ireland. Pilgrims from all over Europe have been coming to the site since as early as the 5th or 6th century. There are records of pilgrims who travelled from Hungary (1363 and 1411), France (1325, 1397 and 1516), Italy (1358 and 1411) and Holland (1411 and 1494). See, Tingle, Elizabeth. 2020. Sacred Journeys in the Counter-Reformation. Boston: De Gruyter. |

| 25 |

As Aubrey notes, Prior LA Flynn sees Lough Derg is “an international, multi-religious site” (Protestants, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Hindu) – but – as most tourist guidebooks warn potential participants – rituals and prayers are deeply rooted in Roman Catholic traditions. RCs would feel more comfortable than non-RCs.

|

| 26 |

Women participated in the pilgrimage as early as 1600. Women's liberation came to Lough Derg before it hit the mainland, because St Brigid is at the top here. You start with her and you must watch your step as she is extremely steep .".. Alice Taylor referring to St Brigid's Penitential bed. #stationisland #loughderg #stpatrickssanctuary #pilgrimage #pilgrims #loughdergpilgrims #pilgrimtales #pilgrimtalesbook #loughdergstories #loughdergpoetry. |

| 27 |

Fiona McGrath’s study of Lough Derg pilgrimages would seem to agree, with 33.6% of her survey respondents stating either ‘pilgrim atmosphere’ (20.8%) or ‘tradition’ (12.8%) as their reason for coming to the lake. See: McGrath, Fiona. 1989." Characteristics of Pilgrims to Lough Derg." Irish Geography, 22, 44–47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00750778909478785. Only 36%? |

| 28 |

James L. Smith. 2019. "Rural Waterscape and Emotional Sectarianism in Accounts of Lough Derg, County Donegal." Rural Landscapes: Society, Environment, History, 6 (1), p.8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16993/rl.54

|

| 29 |

Skoggard, Ian and Alisse Waterston. 2015. "Introduction: Toward an Anthropology of Affect and Evocative Ethnography." Anthropology of Consciousness 26(2): 109-120. Skoggard and Waterston argue that affect is "pre-discursive." It is distributed between -- and outside of – bodies. Natural and social qualities become shrouded in an "atmosphere" -- an ambience or sense of place. Reckwitz underscores the inventive potentials of affect. |

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

William Carleton. 1844 |

| 32 |

James L. Smith., 2019. "Rural Waterscape and Emotional Sectarianism in Accounts of Lough Derg, County Donegal." Rural Landscapes: Society, Environment, History, 6(1), p.2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16993/rl.54

|

| 33 |

Richard Scriven. 2014. “Geographies of Pilgrimage: Meaningful Movements and Embodied Mobilities.” Geography Compass 8: 249–61. |

| 34 |

Lawrence Taylor. 1995. Occasions of Faith |

| 35 |

Alice Curtayne. 1944. Lough Derg: St. Patrick’s Purgatory. London and Dublin: Burns, Oates & Washbourne. |

| 36 |

xxxx. 1981. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion.

|

| 37 |

Kaelber, Lutz. 2006. “Place and Pilgrimage, Real and Imagined.” On the Road to Being There: Studies in Pilgrimage and Tourism in Late Modernity. William H. Swatos Jr. ed., pp. 277-295. E. J. Brill. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047409823_013

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).