1. Introduction

The endocrine system is the body's signaling and messenger pathway [

1]. Numerous glands in the body produce specialized chemicals called hormones [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Hormones attach themselves to special proteins inside and outside cells called receptors [

4]. Each receptor has a specific site on the protein called a binding site, a spot on the receptor that fits a particular hormone [

5]. A binding site on a hormone receptor consists of several functional groups that will weaklybind to the different parts of a hormone and hold it in place [

6,

7]. The binding sites of hormone receptors are very selective for each type of hormone to prevent accidental activation [

4]. The high selectivity of receptor sites means hormones are present in very low concentrations in the body [

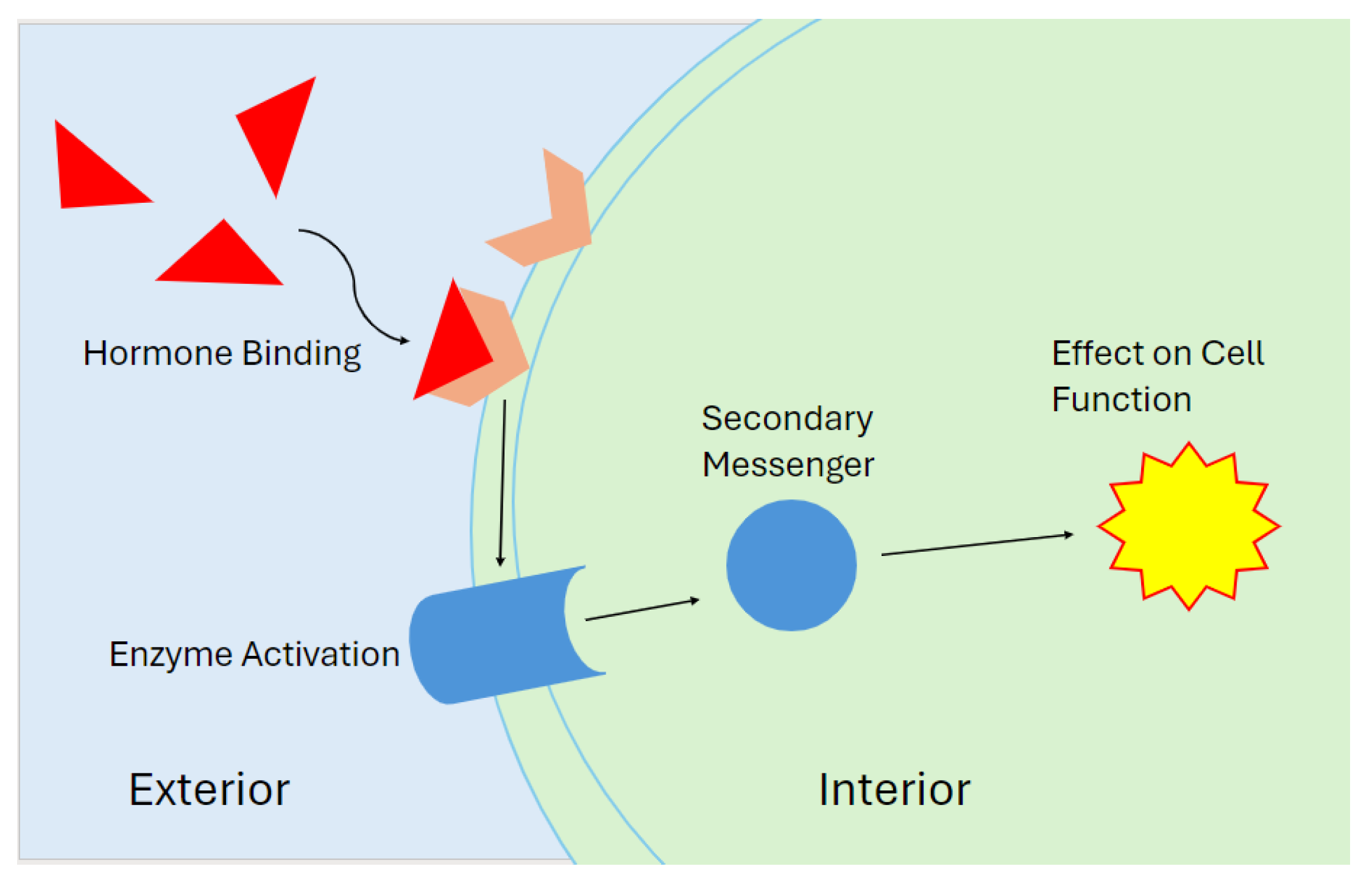

1]. Once a hormone binds to a receptor, the receptor will activate and generate a signal. An activated hormone receptor will change its physical shape from an “inactive” state to an “active” state. This “active” state creates a signal which then reacts with other parts of the cell to create a response (

Figure 1) [

2,

3,

4,

5].

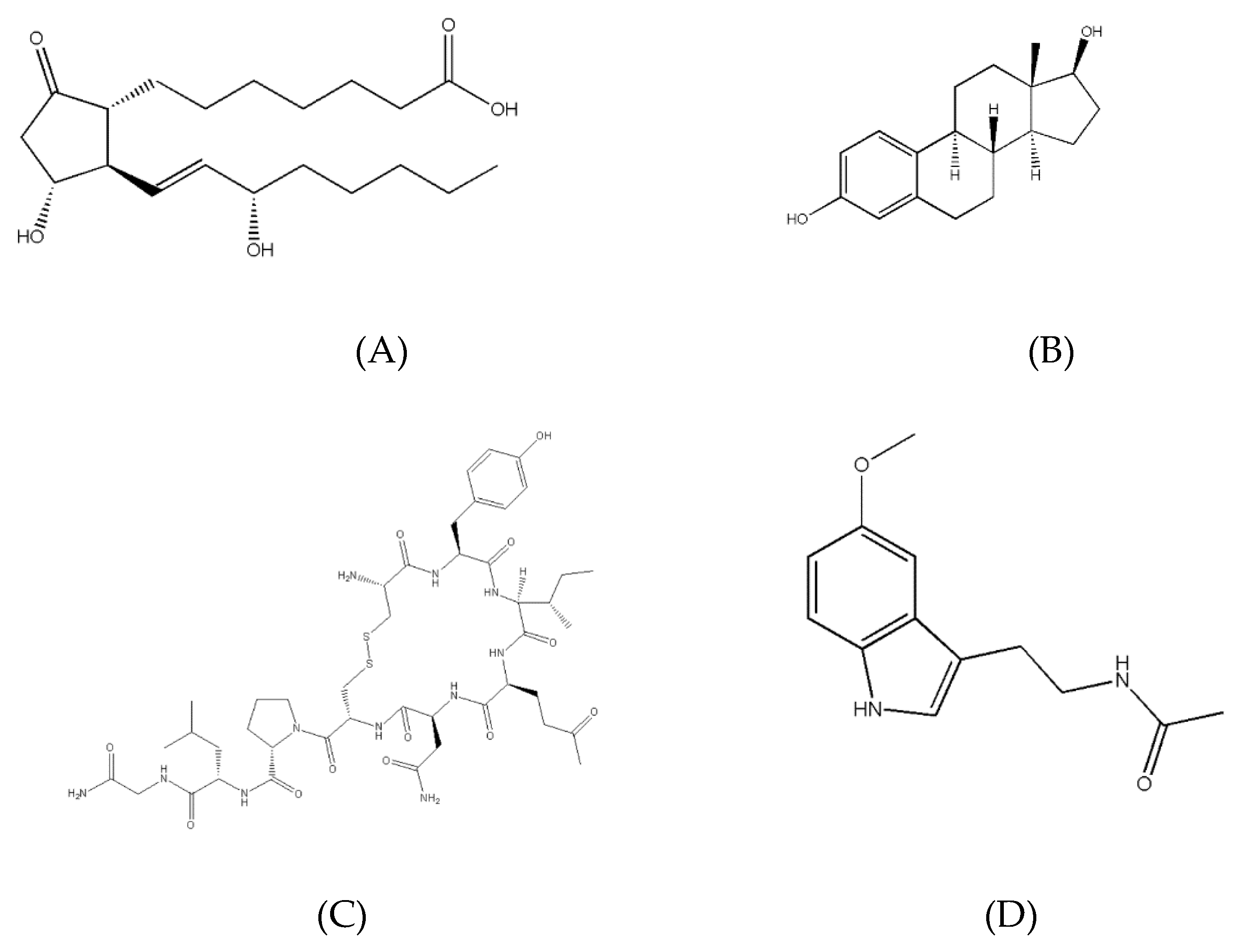

There are three main types of hormones: eicosanoids, steroids, and peptide derivatives (

Figure 2). An eicosanoid hormone is derived from a long-chain fatty acid such as arachidonic acid [

8]. They are usually used to signal either the same cell that produced the hormone or another nearby cell and can produce numerous effects in the body depending on the receptor the eicosanoid binds to [

8]. The chemical structure of eicosanoids indicates that they can only bind to exterior receptors as they cannot easily cross the cell membrane [

8]. A steroid is a hormone derived from the base structure of cholesterol [

2,

5]. Steroid hormones are used as signaling molecules for male/female sexual expression and stress responses [

2,

5]. Most steroid hormones are lipophilic, which means they can cross cell membranes to interact with receptors inside cells [

2,

4]. Peptide-derivative hormones are either made of a single amino acid or a long chain of amino acids (a peptide) [

5]. These hormones are created inside cells through the same DNA transcription method as longer proteins [

2]. Most are stored inside vesicles, which are small bubbles within cells used for storage and transport and are often ejected out of the cell to interact with other cell types [

2]. They will usually signal on surface receptors as they cannot cross the cell membrane without special transport proteins or storage within vesicles prior to removal [

2,

4].

2. Endocrine Disruptors

Every day, humans come into contact with both natural and synthetic substances. Some of these exogenous substances can potentially interfere with the hormonal system, leading to their classification as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [

4]. An endocrine disruptor is any molecule that interferes with the endocrine system’s functioning to create a harmful or adverse effect in the body of an organism or its descendants [

1,

4]. The molecules can be man-made or can come from natural sources [

9]. Hormone receptors are very selective regarding what can bind to the active site and usually can only be activated by a specific hormone [

4]. An endocrine disruptor can bind to a receptor site accidentally by possessing either a similar carbon structure to a hormone or by possessing similar functional groups in a similar layout to a real hormone [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The binding affinity is often much lower for a non-hormone molecule but is still possible with a high enough dose and the correct binding orientation [

6,

10,

14]. A few cases exist where an endocrine disruptor may bind to a receptor despite having no chemical similarity with a hormone. This can be caused by the endocrine disruptor binding in a completely different way than the hormone [

6,

12].

Both hormones and endocrine disruptors can exhibit a nonlinear binding effect [

4]. This means that the amount of the substance present in the body does not increase the effect on the endocrine system in a linear pattern [

1]. Hormones have such a high specificity for their target receptor that a small amount is all that is required for activation. [

4]. Trace amounts on an endocrine disruptor may create a much larger biological response than is expected through the same mechanism [

15].

An EDC can affect the endocrine system in several ways, including interfering with or enhancing hormone creation and removal, interfering with hormone signaling, either by binding to a receptor and activating it or blocking access to the receptor site, interfering with the signaling pathway of the hormone after it has activated a receptor, or interfering with or overexpressing transport proteins that move hormones in the body.

Interference or enhancement of hormone creation and removal. Several classes of endocrine disruptors can interfere with either the creation or release of hormones from several glands in the body [

3,

9,

16,

17]. They can also accelerate the removal of free hormones, causing a loss of hormone activity in the body. There is also a possibility of interfering with the removal process, causing a higher than required number of hormones [

9,

14].

Interference with hormone signaling, either by binding to a receptor and activating it or blocking access to the receptor site. Hormone receptors are very selective about which hormones bind to them but can be fooled by synthetic molecules with a similar structure [

7,

9]. If an endocrine disruptor possesses a similar structure, it can activate the receptor like a hormone and trigger undesired responses [

6,

16,

17]. When an endocrine disruptor activates a receptor, it is referred to as an agonist for that receptor type [

9]. An endocrine disruptor can also bind to keep the receptor locked into the inactive state, preventing it from being activated at all. This leads to a decrease in the desired signal in the cell and is considered an antagonistic response [

9,

10,

17].

Interference with the hormone's signaling pathway after it has activated a receptor. This can include activating other molecular binding sites without a hormone signal, interference with secondary messenger molecules at binding sites, activation or interference with enzymes and transcription proteins, and triggering cell signal cascades without a hormone signal [

9,

13].

Interference with or overexpression of transport proteins that move hormones in the body. Several types of hormones cannot pass through the cellular membrane independently and require special transport proteins. Endocrine disruptors can block access to the transport proteins, keeping hormones inside or outside of the target cell [

16,

17]. They can also cause cells to overproduce transport proteins and cause hormones to move too freely.

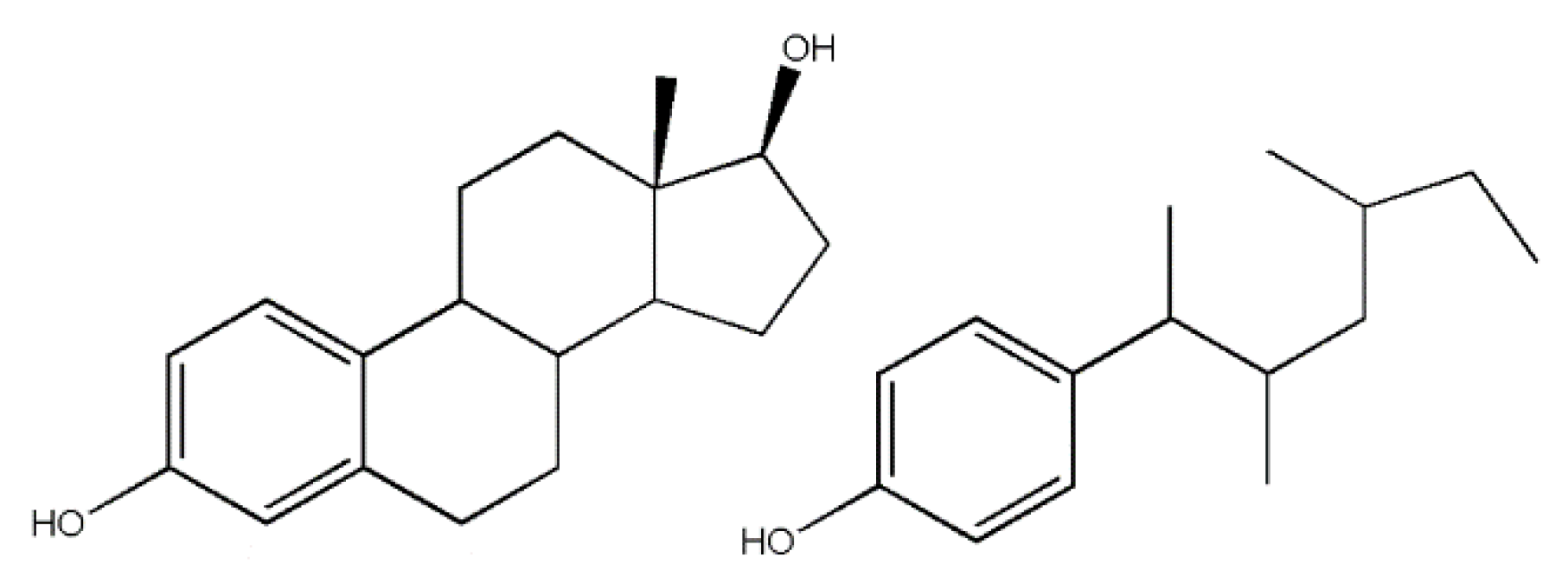

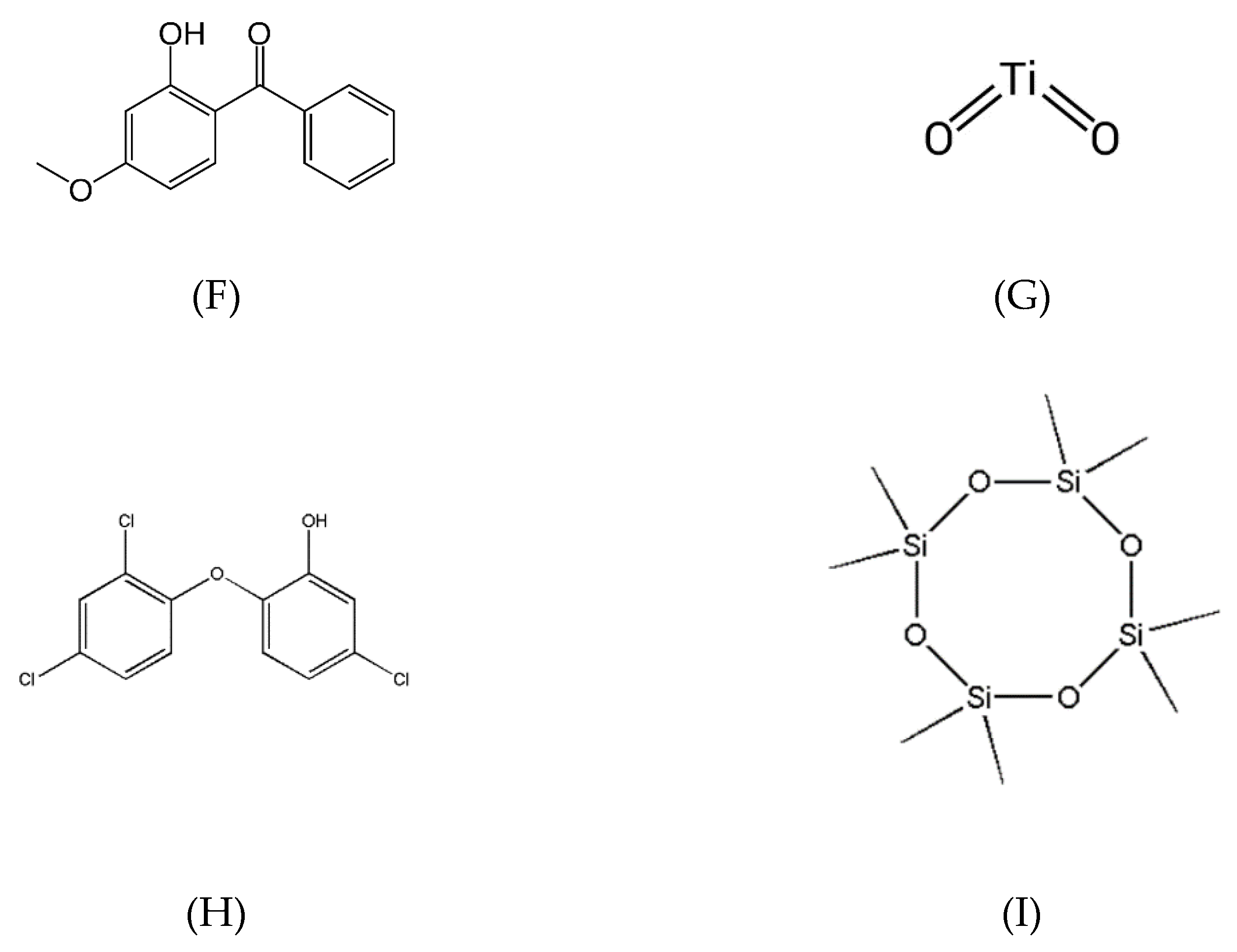

Figure 3.

An example of how an endocrine-disrupting compound can mimic the structure of a hormone. The molecule on the left is estradiol, a natural hormone found in the body. The molecule on the right is an isomer of nonylphenol, a suspected endocrine disruptor. The structural similarity is how a molecule other than a hormone can bind to a hormone receptor site despite the binding site’s specific structure.

Figure 3.

An example of how an endocrine-disrupting compound can mimic the structure of a hormone. The molecule on the left is estradiol, a natural hormone found in the body. The molecule on the right is an isomer of nonylphenol, a suspected endocrine disruptor. The structural similarity is how a molecule other than a hormone can bind to a hormone receptor site despite the binding site’s specific structure.

Health Effects of Endocrine Disruption

Endocrine disruption has been linked to several health concerns, including loss of fertility, reproductive health concerns, various forms of cancer, birth defects/mutations, premature/delayed puberty, obesity/diabetes, hyper and hypothyroidism, immune system interference, and mental health disorders [

1,

4,

14,

18,

19].

3. Endocrine Disrupting Compounds in Fragranced Products

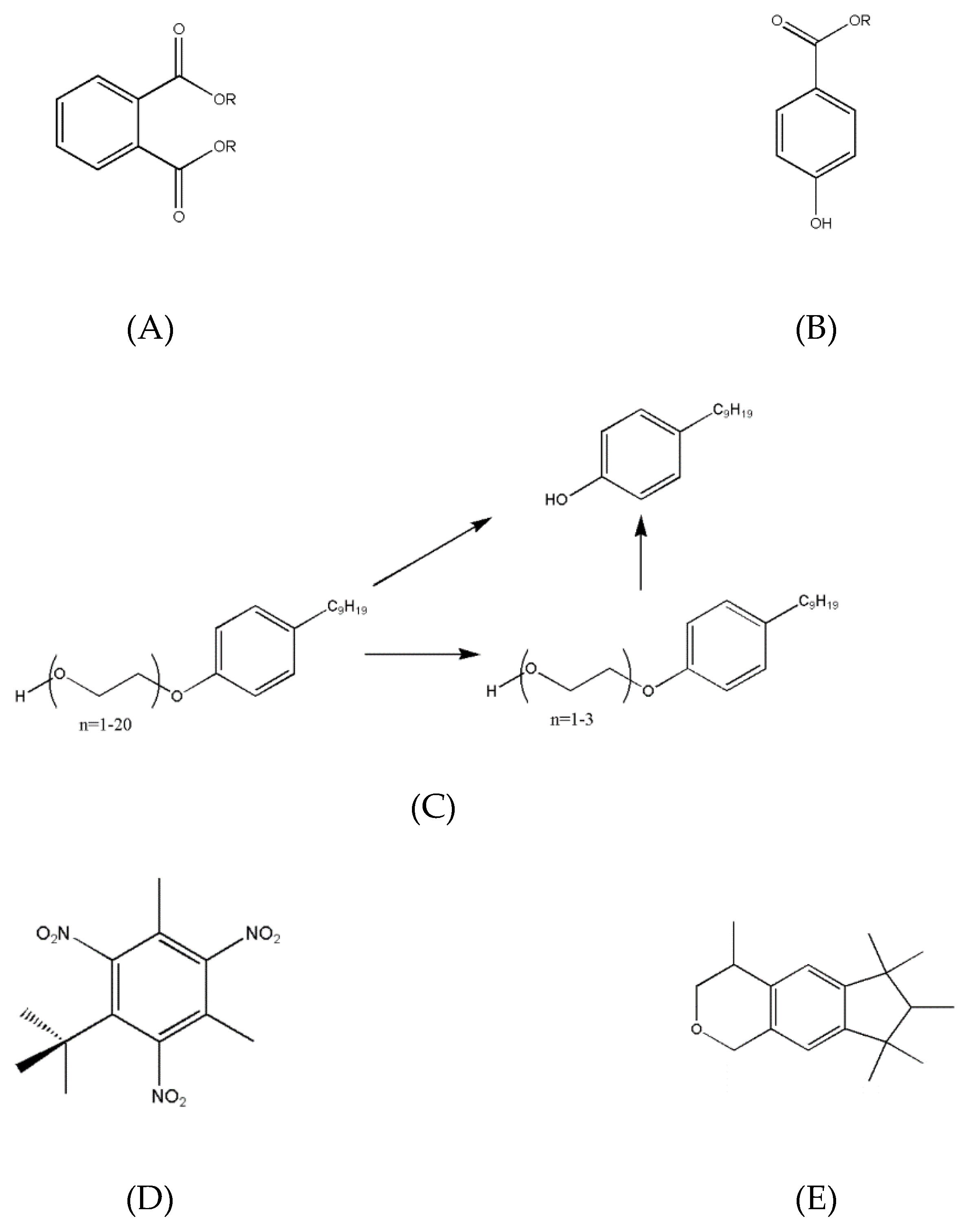

The chemical structures of endocrine-disrupting compounds in fragranced products are shown in

Figure 4.

3.1. Phthalates

A phthalate is an ester of phthalic acid, with various varieties named after the carbon chain length attached to the base molecule (

Figure 4A) [

7,

14,

20]. Several examples are dimethylphthalate (DMP), diethylphthalate (DEP), dibutylphthalate (DBP), and di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) [

21]. Small chain phthalates can be aerosolized; longer varieties will usually stay in solution [

18]. They are used as fixatives and solvents in perfumes, and as components of the plastic bottles many types of personal care products are stored [

7,

21,

22,

23]. The phthalate molecules are not directly bound to the plastic polymers, allowing them to transfer to other liquids or solids that contact the plastic [

1,

21,

24]. Even if phthalates are not part of a particular product's formula, they may still be found in products due to the phthalate dissolving into the product from the bottle itself [

14,

18,

23,

25]. Phthalates have been found to interfere with both thyroid and androgen hormone receptors, along with being suspected of causing several types of cancer and birth defects [

1,

14,

17,

20,

26,

27,

28].

3.2. Parabens

A paraben is an ester of hydroxybenzoic acid (

Figure 4B) [

14,

20]. Several examples include ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben [

28,

29]. Due to their antimicrobial properties, they are used as preservatives in many cosmetics, lotions, and makeup formulations [

1,

23,

29]. Parabens are odorless, colorless, heat and pH-stable, and resistant to chemical reactions [

23,

28,

29]. Though they are generally classified as "safe," shorter-chain parabens can be absorbed into the skin intact and pass into the bloodstream [

18,

28]. Long-chain parabens are more concerning due to a higher chance of binding to hormone receptors [

14,

18,

23]. There is evidence that parabens can act as artificial estrogens and mild androgen/thyroid blockers and are also suspected of increasing breast cancer risk [

3,

14,

18,

28,

29]. There is also evidence that parabens cause allergic skin reactions and contact dermatitis in some cases [

20,

29].

3.3. Alkylphenols

An alkylphenol is a phenol ring combined with a hydrocarbon chain (

Figure 4C) [

30]. The chain can be straight or branched, with multiple isomers present within a product [

21]. Alkylphenols are usually found as ethoxylates (ethylene oxide polymer) in a product but will break down into the base alkylphenol when in the body or natural environment [

28]. The ethoxylate form is relatively unstable, but the basic alkylphenol form has shown greater stability and bioaccumulative properties [

30]. Alkylphenol ethoxylates are used as surfactants (foaming agents) and cleansers in products like soaps, shampoos, conditioners, and toothpaste [

3,

18,

28,

30]. Alkylphenols with longer chains, such as nonylphenol and octophenol, have estrogenic activity and possible antiandrogenic effects [

3,

18,

21,

28,

30].

3.4. Nitro Musks and Polycyclic Musks

Synthetic musk compounds are used as a substitute for natural musk compounds extracted from animal glands [

26,

31,

32,

33]. Natural musk is currently very expensive due to strict regulations on harvesting, so synthetic musks are used in most products to reduce production costs and increase profit [

32,

34]. Most animal musk compounds are macrocyclic ketones, meaning they are a single large carbon ring containing double-bonded oxygen [

32,

33]. Nitro Musks are benzene rings that contain multiple nitro (NO

2 ) groups (

Figure 4D) [

31,

33,

34]. Several common examples are musk xylene, musk ketone, and musk moskene [

33,

35]. Polycyclic Musks are several linked rings, usually with an oxygen molecule as part of one ring (

Figure 4E) [

31,

34,

35]. Several examples are Tonalide (AHTN), Galaxolide (HHCB), and Phantolide (AHMI) [

32]. These compounds are found in many perfumes and scented products and are added as a base note to enhance the smell of other components [

31,

34,

35]. Synthetic musks have been found to be endocrine disruptors for all types of hormones, and several are identified as possible carcinogens and organic pollutants [

26,

28,

32,

36]. Nitro musks have been found to have a much stronger effect, and several varieties have already been banned or restricted in several countries [

18,

28,

31,

33,

34].

3.5. UV Filters

A UV filter is a chemical that either absorbs or reflects UV light and is found in sunscreens and in some varieties of cosmetics, such as lip balms, make up, and lotions [

14,

17,

36,

37]. They can either be organic, usually a derivative of benzophenone or cinnamate, or inorganic, like titanium dioxide [

14,

17,

18,

28]. Organic filters have chemical structures that absorb the UV region, protecting the skin underneath (

Figure 4F) [

14,

28,

37,

38]. Inorganic filters block and scatter the incoming light, reducing its impact (

Figure 4G) [

28,

37]. Inorganic UV filters are suspected of endocrine disruption, but organic filters have shown stronger endocrine-disrupting effects on estrogen, androgen, and thyroid receptors [

14,

18,

28,

36,

38]. Benzophenones and camphor derivatives have shown concerningly high levels of receptor binding and skin penetration [

1,

17,

18,

28,

36,

37]. If left in contact with the skin for long enough, organic filters have been shown to be able to cross the skin barrier due to their lipophilic structures [

28,

38]. Inorganic filters have a much harder time crossing the skin barrier, except in cases where nanoparticles are used [

28].

3.6. Triclosan

Triclosan is an antibacterial agent used in many cleaning products, such as soaps, shampoos, toothpaste, and hospital disinfectants [

18,

23,

39,

40]. It is a weak endocrine disruptor with various effects on estrogen, androgen, and thyroid receptors [

1,

18,

39]. Due to its presence in many types of oral and skin care products, it tends to enter the body through accidental ingestion and dermal absorption [

23,

28,

40]. Triclosan and its metabolites can enter the environment through wastewater treatment [

23,

40]. It shares a similar structure with several other categories of molecules, including PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and PCDDs (polychlorinated dibenzodioxins), which are known carcinogens and highly bioaccumulative (

Figure 4H) [

40]. Triclosan is possibly metabolized into several forms of dioxin under UV radiation while in water [

23,

40]. On its own, Triclosan has not shown definitive carcinogenic properties, but testing has been limited to animal studies [

40].

3.7. Cyclic Methylsiloxanes

A siloxane is a silicon-based molecule bonded to oxygen and carbon (

Figure 4I) [

28,

39,

41]. Cyclic siloxanes are used as conditioners, smoothing agents, and viscosity-controlling agents in various hair products, lotions, and skin care products [

28,

39,

41,

42]. Dermal absorption is usually low, but cyclic siloxanes can be easily volatilized and inhaled [

41,

42,

43]. Evidence shows that cyclic siloxanes can activate estrogen receptors and possibly block androgen receptors. However, the results are inconclusive due to minimal testing [

18,

28,

39]. Smaller rings, such as D4, show a stronger binding effect, but larger rings have a higher chance of bioaccumulation [

41,

43].

4. Exposure Pathways of Endocrine Disruptors

4.1. Inhalation

This is the most common exposure pathway for small molecules that can evaporate into the air. Other endocrine disruptors may be inhaled through dust and powder residues left behind after product use [

1,

20,

25,

39,

44]. Some small molecules are also slowly released from construction materials like plywood, drywall, linoleum tiles, industrial epoxy, and paints [

1,

42,

44,

45]. It also allows for direct access to the bloodstream without barriers for compounds that could be blocked by the skin. Exposure can occur by either direct application of a scented product to the body (such as perfume) or by residual inhalation of molecules absorbed into surfaces or furniture (from an air freshener or cleaning product) [

20,

35,

41,

42,

45]. While inhalation is the most direct exposure pathway, the amounts of molecules that enter the body this way are in trace amounts compared to other exposure pathways [

45,

46]. In addition, smaller molecules are easily metabolized and have a lower affinity for binding to receptor sites [

18,

23].

4.2. Dermal Application

Larger molecules (UV filters, long-chain parabens, etc.) cannot enter the air but can be absorbed through the skin when products containing them are applied. Many types of endocrine disruptors are lipophilic, which means they can bypass the skin's moisture barrier and enter the body [

35,

38,

47]. This absorption occurs more often with products that are made to be left on the skin, such as lotions, some perfumes, and sunscreens [

23,

31,

34,

35,

38,

41,

47]. The body can metabolize many types of molecules as they diffuse across the skin barrier, but some of the intact molecules will get through in their pure form [

22,

27,

28,

35]. This absorption can be accelerated by additional ingredients found in products like lotions that aid skin penetration and hydration [

23,

35]. The skin barrier usually prevents water and other polar molecules from entering or exiting, but certain active ingredients in personal care products aid in the diffusion of polar molecules across the barrier. Longer and larger molecules can have a higher endocrine disrupting effect due to more closely resembling hormones [

7,

15,

18]. They are also harder for the body to metabolize effectively and can accumulate more readily [

23].

4.3. Ingestion

Ingestion of endocrine disruptors is usually unintentional but can still occur due to trace amounts of personal care products or perfumes settling on food or drinks after use [

44,

45]. Other EDCs can enter food from packaging or drink containers containing plasticizers like phthalates [

7,

20,

25]. Triclosan can enter the body through products like mouthwash and toothpaste [

40]. Many EDCs can also be found in food and water due to human pollution [

1,

40,

48]. These environmental pollutants are highly resistant to removal and will remain in water, plants, and animals until they end up being ingested by humans [

48].

5. Environmental Impact

Many types of EDCs in personal care products are highly resistant to removal from the environment and do not easily break down over time. Some compounds can even react to form even more dangerous molecules or highly stable analogs after introduction to the environment [

40,

49]. These compounds enter the environment through sewage treatment and waste disposal when products are rinsed off or thrown away [

30,

34,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Other products can enter the environment from human waste as metabolites or the parent compound, depending on their reactivity [

27,

55,

56]. Even with processes in place, such as wastewater treatment plants, many endocrine disruptors can get released into natural water sources at a substantial rate [

30,

48,

49,

50,

52,

54,

55]. The discharge is significantly higher in treatment plants connected to industrial processors or companies that produce personal care products [

30,

40,

51,

55,

57]. Sediment can act as a storage medium for endocrine disruptors, slowly releasing them back into the water over long periods of time [

52,

57,

58]. Certain organisms, such as earthworms, may also be able to pull endocrine disruptors out of soil [

58].

Endocrine disruptors are hazardous to humans and can also affect animals that drink contaminated water or eat contaminated plants, leading to biomagnification and damage to the ecosystem [

4,

18,

53,

55]. Their effects on animals can lead to fertility loss, species depopulation, and a higher chance of non-viable offspring [

55,

58,

59]. Evidence shows that endocrine disruptors persist and reach environments with little to no human contact through water systems and ocean currents [

48,

60].

These environmental effects are not limited to endocrine disruptors from personal care products. Additional contaminants such as polyhalogenated compounds (PCBs, brominated flame retardants, polyfluoroalkyls), pesticides, bisphenols (BPA), and others are also accumulative in the environment and act as endocrine disruptors [

1,

3,

21,

54]. These other categories of endocrine disruptors have shown far more hazardous health effects and can be even harder to remove from the environment due to forming highly stable metabolites [

21,

61]. Many of these types of endocrine disruptors have been restricted or banned in many parts of the world but continue to be present due to their highly persistent nature [

3,

21].

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification

Bioaccumulation occurs when certain molecules cannot be removed easily from the body and slowly build up a high concentration [

58]. This is mainly caused by repeated exposure to chemicals from various sources [

24,

25,

39,

62]. Hydrophobic molecules tend to bioaccumulate more easily by being absorbed into fat deposits inside organisms [

24,

52,

62]. The human body will attempt to metabolize and remove small amounts of EDCs, but when the number and amount of chemicals from external sources entering the body is too high, the body can no longer remove them effectively [

23,

25]. Bioaccumulation can easily lead to health concerns as accumulating molecules can exceed recommended use levels in individuals exposed to multiple sources of the same molecule [

1,

23,

25]. Bioaccumulation also occurs in animals and plants in environments exposed to endocrine disruptors [

52,

53,

55,

59,

62].

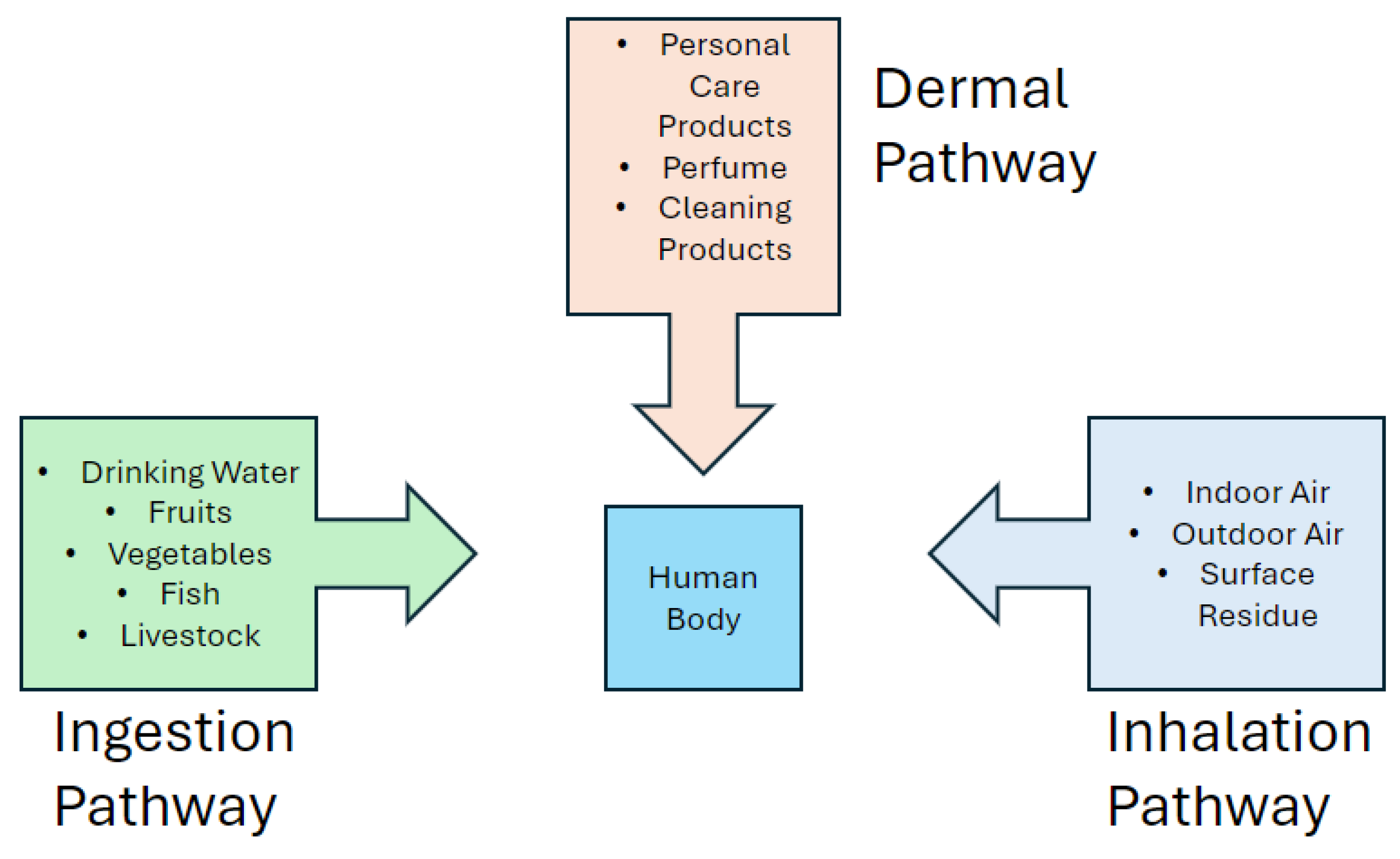

Figure 5.

A diagram that demonstrates bioaccumulation. Endocrine disruptors can enter the body through several pathways and accumulate if the body cannot easily remove them.

Figure 5.

A diagram that demonstrates bioaccumulation. Endocrine disruptors can enter the body through several pathways and accumulate if the body cannot easily remove them.

Biomagnification occurs when the level of a chemical, such as an endocrine disruptor, increases each step up the food chain [

58,

60,

61]. In a contaminated ecosystem, all organisms will have some acquired concentration of the endocrine disruptor [

52,

53,

57,

61]. The amounts acquired are initially small, but with each step up in trophic level, they accumulate more and more from the previous food source [

40,

52,

57]. Exposure to endocrine disruptors starts in the water and soil, accumulating in producers, such as plankton, bacteria, or small plants, and continues to increase as animals consume organisms with higher concentrations [

53,

61]. Humans are at the top of most food chains and thus receive the highest doses of environmental endocrine disruptors [

23].

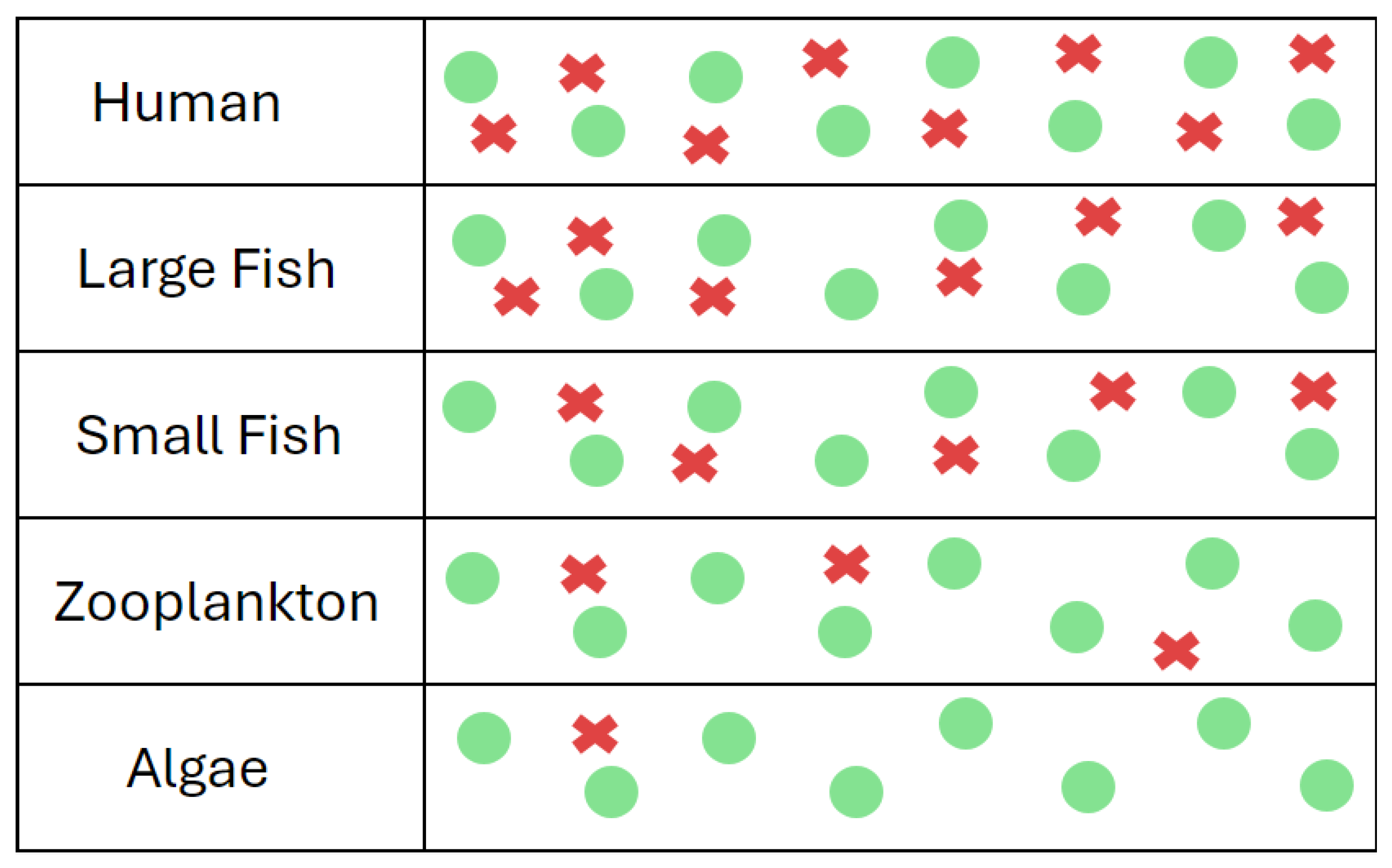

Figure 6.

An example of biomagnification in an aquatic ecosystem. The green dots represent normal molecules present in the organism's body, and the red symbols represent an endocrine disruptor. As larger predators consume animals or plants lower on the food chain, they accumulate higher levels of endocrine disruptors from each level below.

Figure 6.

An example of biomagnification in an aquatic ecosystem. The green dots represent normal molecules present in the organism's body, and the red symbols represent an endocrine disruptor. As larger predators consume animals or plants lower on the food chain, they accumulate higher levels of endocrine disruptors from each level below.

6. Synergistic Effects

Mixtures of EDCs can exert synergistic effects with one another, causing ever stronger effects. A synergistic effect is when a mixture of two or more molecules produces a greater biological effect than a single molecule produces on its own [

15,

16,

18,

63]. Some mixtures can possess unpredictable synergy (1+1 = 8) where each component magnifies the effect of each other several times higher than what a simple additive effect (1+1=2) would be expected to produce [

1,

12,

18,

64]. The intensity of the synergistic effect is often difficult to predict due to the large number of binding sites in the body, combined with all the possible endocrine disruptors that could synergize with each other [

15,

16,

64].

While the exact mechanism of action for mixtures is not well known, synergistic effects are mainly believed to occur due to several molecules simultaneously binding to a hormone receptor [

1,

12,

64]. Hormone receptor binding sites have multiple sites where functional groups on the hormone bind, ensuring the binding site's selectivity. It is very unlikely that an endocrine disruptor matches a hormone's structure and will only match a few functional groups. Two or more smaller endocrine disruptors together could make a near-perfect match to certain receptors if they match the functional groups, even if the main structure does not match [

12,

64].

It is also possible that a mixture of two endocrine disruptors may have synergy by one molecule, which indirectly assists the binding of the other [

18]. Some receptors can have additional binding sites that other small molecules can bind to. These small sites affect the shape of the hormone-binding site and can allow for easier binding and activation [

65]. This is referred to as allosteric binding.

A synergistic reaction may not even be caused by a mixture of two endocrine disruptors. Environmental pollutants, heavy metals, medications, cleaning agents, and other unrelated chemicals could cause unintentional synergistic effects [

1,

12,

16,

63]. Anything that matches part of a binding site functional group may bind when combined with another molecule.

7. Natural vs Synthetic Products

Most essential oils (EOs) are considered non-harmful under the instructions for recommended use. Authentic EOs are free from synthetic additives and contain only molecules present in the plant [

66]. Even in the case of diluted oils, the dilution is usually carried out using carrier oils, which are also plant-based and have been shown to be safe in recommended amounts. It is crucial to mention that the chemical profiles and component concentrations of most of the common EOs are well-documented in the literature [

66]. This makes it much easier for consumers to avoid skin contact with oils containing known skin irritants [

66].

On the other hand, perfumes often contain synthetic scent molecules, along with fixatives, preservatives, and other chemicals [

22,

23,

27,

67]. They are usually diluted in chemical solvents; some can be hazardous in large doses. They contain EDCs, skin allergens, artificial dyes, and other less desirable chemicals [

22,

23,

26,

27,

35,

68]. Most perfumes will not disclose fragrance ingredients, only ingredients required by law [

23,

26,

34,

39,

50,

67,

69]. Required ingredients include synthetic scent molecules known to be hazardous in high doses or known to cause contact allergy [

47,

50,

67,

68]. Even when potentially hazardous ingredients are disclosed, they are often used at the maximum allowed concentration or misleadingly labeled [

23,

39,

70]. Perfumes also tend to cause much higher rates of allergic reactions, phototoxicity, skin sensitivity, and other undesirable effects [

23,

26,

27,

67]. These problems also extend to many other personal care products [

39,

69].

An important thing to note is that buying from a reputable source is important for both forms of product. EOs and perfumes can very easily be counterfeited to sell at a discount [

66,

71,

72]. Unlike actual oils or perfumes, these counterfeit products have zero regulation on what goes into them and often have low-quality control and safety standards [

72]. Counterfeit perfumes have been found to contain toxic solvents, banned fragrance ingredients, and dangerous levels of ingredients that are restricted in genuine perfume [

71].

Some EOs contain certain molecules that have shown signs of endocrine disruption. Anethole from fennel, linalool from lavender, terpinen-4-ol from tea tree oil, and geraniol/nerol from citronella and other flowers are some of the most common examples [

28,

73,

74,

75]. While the endocrine-disrupting effects of these molecules have been documented, a very high dose over an extended time is required to cause any noticeable effect. Experiments performed on isolated EO components show that the binding affinity for hormone receptors is so low that it can require doses over 10000 times higher than an artificial hormone to trigger a similar response [

73]. If all safety instructions on essential oil bottles are followed, the risk of endocrine disorders from EOs will be minimal. It is important to note that the low reactivity of essential oil components applies to pure oil [

76]. Personal care products and perfumes that use essential oil for fragrance may still contain other endocrine disruptors, such as parabens, phthalates, and xenoestrogens from soy products used in soaps and lotions [

12,

74,

75]. This can trigger a synergistic effect and produce stronger disruptive effects, either from synthetic components synergizing or the natural ones combined with synthetics [

4,

74,

75].

7.1. Chirality

Several components of essential oils are “chiral, which means two molecules with identical formulas and structures that are mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed on each other [

77]. Most chiral molecules have a chiral center, a single carbon atom bonded to four unique atoms or carbon structures. Molecules may also be considered chiral if they contain an unmoving bond, such as a double bond, connected to four unique atoms or carbon structures. A chiral molecule will have two forms, or enantiomers, each with its own physical and chemical properties [

66,

77,

78]. The two enantiomers will be labeled either (+) or (—), which is determined by the optical properties of the molecule. Chiral molecules will rotate light passing through them, and the direction of the spin will determine which symbol identifies it [

77]. Clockwise is +, and counterclockwise is -—. Chiral enantiomers may also be labeled with an S or an R, which is related to the absolute configuration of the chiral center.

Natural essential oils will usually contain mostly one form of a chiral molecule, but synthetic scents will have an equal mix of the two. Plants tend to have a biological preference for one form of chiral molecule [

66,

77]. This is because chemical synthesis within plants is based on the chiral structure of both the plant’s DNA and proteins. Both types of large molecules are made of chiral isomers and will create other molecules that match their enantiomer form [

77]. Industrial synthesis, however, does not have a biological preference and will result in an equal mix of the two enantiomers. Creating only one enantiomer of a chiral molecule is possible, but it requires many additional steps, making the final product far more expensive.

Chiral molecules will have different biological activities based on their form and can trigger stronger endocrine-disrupting effects [

77,

78]. Human proteins are chiral, just like plant proteins, and will more easily bind to molecules with the same chiral form. This increases the chance of binding and triggering a biological effect [

77]. This is why some essential oils show stronger signs of endocrine disruption than others [

74]. Artificial scents, conversely, are more likely to trigger an endocrine effect due to having both forms equally present [

74].

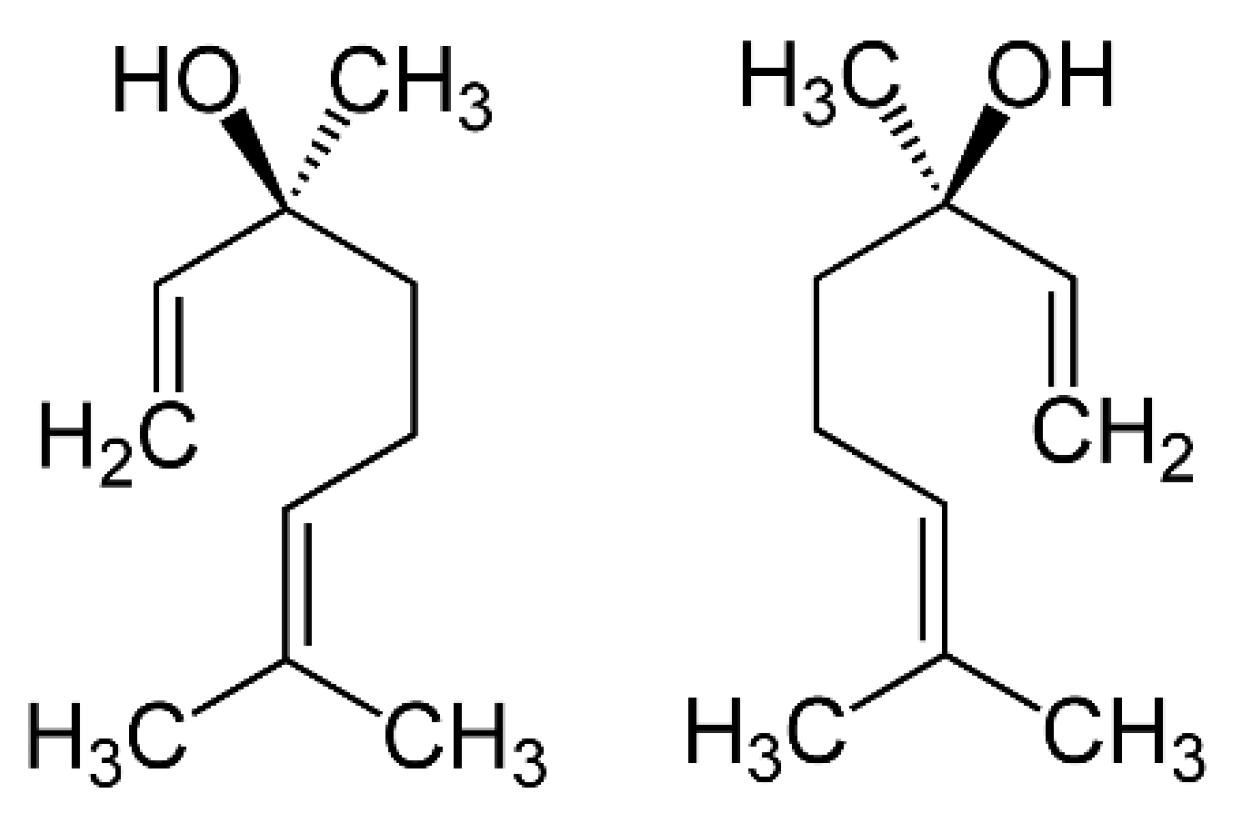

Figure 7.

Linalool comes in two forms: (+)-linalool (left) or (—)-linalool (right). Each form has a different smell and a different biological activity.

Figure 7.

Linalool comes in two forms: (+)-linalool (left) or (—)-linalool (right). Each form has a different smell and a different biological activity.

"Green" or "All Natural" Products

Several varieties of personal care products and perfumes may be labeled as "green" or "all-natural"; however, there is no legal regulation on what the term means [

23,

39,

42]. Regulations are only in place to ensure safety guidelines are followed and known hazardous ingredients are disclosed and kept below limits, but even those guidelines may be ignored [

23,

26,

50,

67,

70]. Other terms are used for marketing and have no regulatory backing. All natural products can often contain the exact same types of molecules as regular products of the same type in smaller or equal amounts [

39,

69].

Perfumes might claim to be using scents from natural sources but use synthetically created molecules that are identical to what is found in a plant to replicate the smell [

23,

66]. Without extensive testing, such as radiocarbon dating, it is difficult to determine if a scent molecule came from a natural or artificial source as the structure is identical. While there is no real chemical difference between an artificial scent molecule and a natural one with the same structure, the ratios of molecules in a natural essential oil may differ, leading to different effects on the body [

66].

A perfume made with only essential oils may still contain up to 90% solvent and additives or fixatives [

50,

66,

67]. Different perfume and cologne varieties will use different solvent ratios based on their intended use [

50,

66]. Solvents such as ethanol can be toxic, aid in hazardous substances diffusing across the skin membrane, or cause allergic skin reactions after extended use [

35].

Other products, such as cleaners and personal care products, may also be called “unscented.” However, this can occasionally be untrue due to the presence of “masking scents” [

67,

70]. Masking scents are molecules added to a product to cover up the smell of cleaning agents or other undesirable smells to create a neutral result [

23]. These masking smells are often synthetic oil components like limonene and various forms of pinene [

70].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the endocrine system plays a crucial role in our body's overall functioning, and any disruption caused to this system can have severe consequences. Both natural and synthetic substances can act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormone signaling and affecting the body's overall health. It is necessary to be aware of the potential dangers of these substances and take necessary measures to avoid exposure to them. Researchers must continue studying endocrine disruptors' impact on human health to identify and mitigate potential risks. Ultimately, our understanding of endocrine disruptors can help us make informed decisions and lead healthier lives.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank xxx for supporting this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Demeneix, B. Endocrine Disruptors: From Scientific Evidence to Human Health Protection.

- Rosol, T.J.; DeLellis, R.A.; Harvey, P.W.; Sutcliffe, C. Endocrine System. In Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 2391–2492 ISBN 978-0-12-415759-0.

- Darbre, P. Overview of Air Pollution and Endocrine Disorders. IJGM 2018, Volume 11, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Å.; Heindel, J.; Jobling, S.; Kidd, K.; Zoeller, R.T. State-of-the-Science of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals, 2012. Toxicology Letters 2012, 211, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S. The Endocrine System. Research World 1998, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Le Maire, A.; Bourguet, W.; Balaguer, P. A Structural View of Nuclear Hormone Receptor: Endocrine Disruptor Interactions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, I.A.; Turki, R.F.; Abuzenadah, A.M.; Damanhouri, G.A.; Beg, M.A. Endocrine Disruption: Computational Perspectives on Human Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and Phthalate Plasticizers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Eicosanoids. Essays in Biochemistry 2020, 64, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combarnous, Y.; Nguyen, T.M.D. Comparative Overview of the Mechanisms of Action of Hormones and Endocrine Disruptor Compounds. Toxics 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, S.; Tokunaga, T.; Liu, X.; Okada, H.; Matsushima, A.; Shimohigashi, Y. Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A Strongly Binds to Human Estrogen-Related Receptor γ (ERRγ) with High Constitutive Activity. Toxicology Letters 2006, 167, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; De, P.; Kumar, V.; Kar, S.; Roy, K. Quick and Efficient Quantitative Predictions of Androgen Receptor Binding Affinity for Screening Endocrine Disruptor Chemicals Using 2D-QSAR and Chemical Read-Across. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, P.; Delfosse, V.; Grimaldi, M.; Bourguet, W. Structural and Functional Evidences for the Interactions between Nuclear Hormone Receptors and Endocrine Disruptors at Low Doses. Comptes Rendus. Biologies 2017, 340, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Grajales, D.; Bernardes, G.J.L.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Urban Endocrine Disruptors Targeting Breast Cancer Proteins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witorsch, R.J.; Thomas, J.A. Personal Care Products and Endocrine Disruption: A Critical Review of the Literature. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2010, 40, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Tan, T.; Lee, S.; Cheng, S.; Lee, F.; Xu, S.; Ho, K. Toxicity and Estrogenic Endocrine Disrupting Activity of Phthalates and Their Mixtures. IJERPH 2014, 11, 3156–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, N.; Junaid, M.; Pei, D.-S. Combined Toxicity of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: A Review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 215, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuttke, W.; Jarry, H.; Seidlovα-Wuttke, D. Definition, Classification and Mechanism of Action of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals.

- Ripamonti, E.; Allifranchini, E.; Todeschi, S.; Bocchietto, E. Endocrine Disruption by Mixtures in Topical Consumer Products. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.P.; Herring, A.H.; Wolff, M.S.; Calafat, A.M.; Engel, S.M. Prenatal Exposure to Environmental Phenols and Childhood Fat Mass in the Mount Sinai Children’s Environmental Health Study. Environment International 2016, 91, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralczyk, K. A Review of the Impact of Selected Anthropogenic Chemicals from the Group of Endocrine Disruptors on Human Health. Toxics 2021, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Bayen, S.; Desrosiers, M.; Muñoz, G.; Sauvé, S.; Yargeau, V. An Introduction to the Sources, Fate, Occurrence and Effects of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Released into the Environment. Environmental Research 2022, 207, 112658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingin, K.; Chen, H.; Gamez, G.; Zhu, L.; Zenobi, R. Detection of Diethyl Phthalate in Perfumes by Extractive Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, L. The Health Risks of Chemicals in Personal Care Products and Their Fate in the Environment.

- He, M.-J.; Lu, J.-F.; Wang, J.; Wei, S.-Q.; Hageman, K.J. Phthalate Esters in Biota, Air and Water in an Agricultural Area of Western China, with Emphasis on Bioaccumulation and Human Exposure. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 698, 134264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net, S.; Sempéré, R.; Delmont, A.; Paluselli, A.; Ouddane, B. Occurrence, Fate, Behavior and Ecotoxicological State of Phthalates in Different Environmental Matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4019–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rádis-Baptista, G. Do Synthetic Fragrances in Personal Care and Household Products Impact Indoor Air Quality and Pose Health Risks? JoX 2023, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, Z.; Aboutaleb, E.; Shahsavani, A.; Kermani, M.; Kazemi, Z. Evaluation of Pollutants in Perfumes, Colognes and Health Effects on the Consumer: A Systematic Review. J Environ Health Sci Engineer 2022, 20, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantelouve, M.; Ripoll, L. Review_Endocrine_disruptors_in_cosmetics_preprint.Pdf. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Paul, N.; Ghosh, S.; Das, M. An Overview of Endocrine Disrupting Chemical Paraben and Search for An Alternative – A Review. Proc Zool Soc 2021, 74, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priac, A.; Morin-Crini, N.; Druart, C.; Gavoille, S.; Bradu, C.; Lagarrigue, C.; Torri, G.; Winterton, P.; Crini, G. Alkylphenol and Alkylphenol Polyethoxylates in Water and Wastewater: A Review of Options for Their Elimination. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2017, 10, S3749–S3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosens, L.; Covaci, A.; Neels, H. Concentrations of Synthetic Musk Compounds in Personal Care and Sanitation Products and Human Exposure Profiles through Dermal Application. Chemosphere 2007, 69, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Burg, B.; Schreurs, R.; Van Der Linden, S.; Seinen, W.; Brouwer, A.; Sonneveld, E. Endocrine Effects of Polycyclic Musks: Do We Smell a Rat? Int J of Andrology 2008, 31, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeiser, H.H.; Gminski, R.; Mersch-Sundermann, V. Evaluation of Health Risks Caused by Musk Ketone. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2001, 203, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homem, V.; Silva, E.; Alves, A.; Santos, L. Scented Traces – Dermal Exposure of Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Personal Care Products and Environmental Input Assessment. Chemosphere 2015, 139, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragrances; Frosch, P. J., Johansen, J.D., White, I.R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998; ISBN 978-3-642-80342-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs, R.H.M.M. Interaction of Polycyclic Musks and UV Filters with the Estrogen Receptor (ER), Androgen Receptor (AR), and Progesterone Receptor (PR) in Reporter Gene Bioassays. Toxicological Sciences 2004, 83, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santander Ballestín, S.; Luesma Bartolomé, M.J. Toxicity of Different Chemical Components in Sun Cream Filters and Their Impact on Human Health: A Review. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, L.; Wu, S.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhuang, S. Recent Advances on Endocrine Disrupting Effects of UV Filters. IJERPH 2016, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, R.E.; Nishioka, M.; Standley, L.J.; Perovich, L.J.; Brody, J.G.; Rudel, R.A. Endocrine Disruptors and Asthma-Associated Chemicals in Consumer Products. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.-L.; Stingley, R.L.; Beland, F.A.; Harrouk, W.; Lumpkins, D.L.; Howard, P. Occurrence, Efficacy, Metabolism, and Toxicity of Triclosan. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C 2010, 28, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horii, Y.; Kannan, K. Survey of Organosilicone Compounds, Including Cyclic and Linear Siloxanes, in Personal-Care and Household Products. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2008, 55, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, Z.; Chen, Z.; Haghighat, F.; Nasiri, F.; Dong, J. Estimation of Anthropogenic VOCs Emission Based on Volatile Chemical Products: A Canadian Perspective. Environmental Management 2023, 71, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.L.; Regan, J.M.; Tobin, J.M.; Marinik, B.J.; McMahon, J.M.; McNett, D.A.; Sushynski, C.M.; Crofoot, S.D.; Jean, P.A.; Plotzke, K.P. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of the Estrogenic, Androgenic, and Progestagenic Potential of Two Cyclic Siloxanes. Toxicological Sciences 2006, 96, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halios, C.H.; Landeg-Cox, C.; Lowther, S.D.; Middleton, A.; Marczylo, T.; Dimitroulopoulou, S. Chemicals in European Residences – Part I: A Review of Emissions, Concentrations and Health Effects of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Science of The Total Environment 2022, 839, 156201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazaroff, W.W.; Coleman, B.K.; Destaillats, H.; Hodgson, A.T.; Liu, D.-L.; Lunden, M.M.; Singer, B.C.; Weschler, C.J. Indoor Air Chemistry: Cleaning Agents, Ozone and Toxic Air Contaminants 2006.

- Lee, I.; Scrochi, C.; Chon, O.; Cancellieri, M.A.; Ghosh, A.; O’Brien, J.; Ring, B.; McNamara, C.; Api, A.M. Detailed Aggregate Exposure Analysis Shows That Exposure to Fragrance Ingredients in Consumer Products Is Low: Many Orders of Magnitude below Thresholds of Concern. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2024, 148, 105569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickers, D.R.; Calow, P.; Greim, H.A.; Hanifin, J.M.; Rogers, A.E.; Saurat, J.-H.; Glenn Sipes, I.; Smith, R.L.; Tagami, H. The Safety Assessment of Fragrance Materials. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2003, 37, 218–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, N.R.; Guitart, C.; Fuentes, G.; Readman, J.W. Inputs and Distributions of Synthetic Musk Fragrances in an Estuarine and Coastal Environment; a Case Study. Environmental Pollution 2010, 158, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wang, B.; Yuan, H.; Deng, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G. Pay Special Attention to the Transformation Products of PPCPs in Environment. Emerging Contaminants 2017, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Mirza, F. Fragrances and Their Effects on Public Health: A Narrative Literature Review.

- Ramirez, A.J.; Brain, R.A.; Usenko, S.; Mottaleb, M.A.; O’Donnell, J.G.; Stahl, L.L.; Wathen, J.B.; Snyder, B.D.; Pitt, J.L.; Perez-Hurtado, P.; et al. Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Fish: Results of a National Pilot Study in the United States. Enviro Toxic and Chemistry 2009, 28, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebele, A.J.; Abou-Elwafa Abdallah, M.; Harrad, S. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in the Freshwater Aquatic Environment. Emerging Contaminants 2017, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, V.; Simões, M.; Gomes, I.B. Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Water Systems and Their Impact on Microbial Communities. Water 2022, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Petrie, B.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Wolfaardt, G.M. The Fate of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs), Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants (EDCs), Metabolites and Illicit Drugs in a WWTW and Environmental Waters. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, A.S.; Xue, J.; Zhao, Y.; Taylor, A.A.; Zenobio, J.E.; Sun, Y.; Han, Z.; Salawu, O.A.; Zhu, Y. Abundance, Fate, and Effects of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Aquatic Environments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 424, 127284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopardo, L.; Adams, D.; Cummins, A.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Verifying Community-Wide Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors in Personal Care Products – In Quest for Metabolic Biomarkers of Exposure via in Vitro Studies and Wastewater-Based Epidemiology. Water Research 2018, 143, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-K. Trophic Transfer of Organochlorine Pesticides through Food-Chain in Coastal Marine Ecosystem. Environmental Engineering Research 2019, 25, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, B.; Böhling, S.; Bruckmann, U.; Franke, C.; Jöhncke, U.; Studinger, G. The Assessment of Bioaccumulation.

- Kesic, R.; Elliott, J.E.; Fremlin, K.M.; Gauthier, L.; Drouillard, K.G.; Bishop, C.A. Continuing Persistence and Biomagnification of DDT and Metabolites in Northern Temperate Fruit Orchard Avian Food Chains. Enviro Toxic and Chemistry 2021, 40, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarphedinsdottir, H.; Gunnarsson, K.; Gudmundsson, G.A.; Nfon, E. Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification of Organochlorines in a Marine Food Web at a Pristine Site in Iceland. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2010, 58, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikemoto, T.; Tu, N.P.C.; Watanabe, M.X.; Okuda, N.; Omori, K.; Tanabe, S.; Tuyen, B.C.; Takeuchi, I. Analysis of Biomagnification of Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Aquatic Food Web of the Mekong Delta, South Vietnam Using Stable Carbon and Nitrogen Isotopes. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagi, T. Bioconcentration, Bioaccumulation, and Metabolism of Pesticides in Aquatic Organisms. In Review of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 204; Whitacre, D.M., Ed.; Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010; Vol. 204, pp. 1–132; ISBN 978-1-4419-1445-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Ji, K. Identification of Combinations of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Household Chemical Products That Require Mixture Toxicity Testing. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 240, 113677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfosse, V.; Huet, T.; Harrus, D.; Granell, M.; Bourguet, M.; Gardia-Parège, C.; Chiavarina, B.; Grimaldi, M.; Le Mével, S.; Blanc, P.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Synergistic Activation of the RXR–PXR Heterodimer by Endocrine Disruptor Mixtures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2020551118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Wang, F.; Xin, F. Structural and Biochemical Insights into the Allosteric Activation Mechanism of AMP -activated Protein Kinase. Chem Biol Drug Des 2017, 89, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmeen, J.; Mahomoodally, F.; Zengin, G.; Maggi, F. Essential Oils as Natural Sources of Fragrance Compounds for Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, A.C.; Frosch, P.J. Adverse Reactions to Fragrances: A Clinical Review. Contact Dermatitis 1997, 36, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempińska-Kupczyk, D.; Kot-Wasik, A. The Potential of LC–MS Technique in Direct Analysis of Perfume Content. Monatsh Chem 2019, 150, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. Fragranced Consumer Products: Exposures and Effects from Emissions. Air Qual Atmos Health 2016, 9, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Fang, M.-C.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Huang, S.-C.; Wang, D.-Y. Quantitative Analysis of Fragrance Allergens in Various Matrixes of Cosmetics by Liquid-Liquid Extraction and GC-MS. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2021, 29, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghoutane, Y.; Brebu, M.; Moufid, M.; Ionescu, R.; Bouchikhi, B.; El Bari, N. Detection of Counterfeit Perfumes by Using GC-MS Technique and Electronic Nose System Combined with Chemometric Tools. Micromachines 2023, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, C.L.; De Lima, A.C.A.; Loiola, A.R.; Da Silva, A.B.R.; Cândido, M.C.L.; Nascimento, R.F. Multivariate Classification of Original and Fake Perfumes by Ion Analysis and Ethanol Content. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2016, 61, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.-J.R.; Houghton, P.J.; Barlow, D.J.; Pocock, V.J.; Milligan, S.R. Assessment of Estrogenic Activity in Some Common Essential Oil Constituents. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2010, 54, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.T.; Li, Y.; Arao, Y.; Naidu, A.; Coons, L.A.; Diaz, A.; Korach, K.S. Lavender Products Associated With Premature Thelarche and Prepubertal Gynecomastia: Case Reports and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Activities. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2019, 104, 5393–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J. Prepubertal Gynecomastia Linked to Lavender and Tea Tree Oils. The New England Journal of Medicine 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Dunne, E.; Keenan, L. Prevalence of Endocrine Disorders among Children Exposed to Lavender Essential Oil and Tea Tree Essential Oils. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2022, 9, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.K.; Bahadur, B. Chirality in Nature and Biomolecules: An Overview. Int. Jrnl. Life Sci. 2020, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, N.; Ross, P.A.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Kolev, S.D.; Steinemann, A. Limonene Emissions: Do Different Types Have Different Biological Effects? IJERPH 2021, 18, 10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).