Submitted:

01 July 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Enrollment

2.2. ESD Procedure and Surveillance Methods

2.3. Definition of Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients, Endoscopic and Pathologic Characteristics

3.2. Short-Term Outcomes and ESD-Related Complications

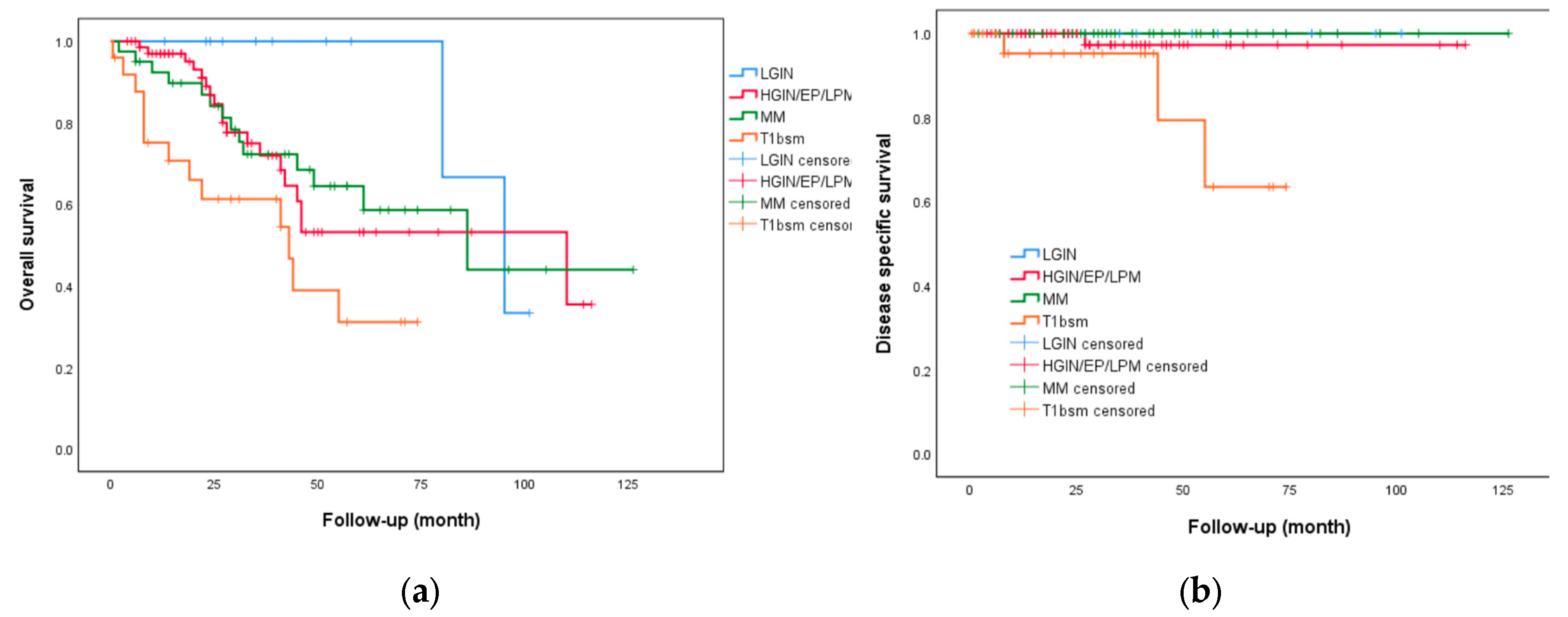

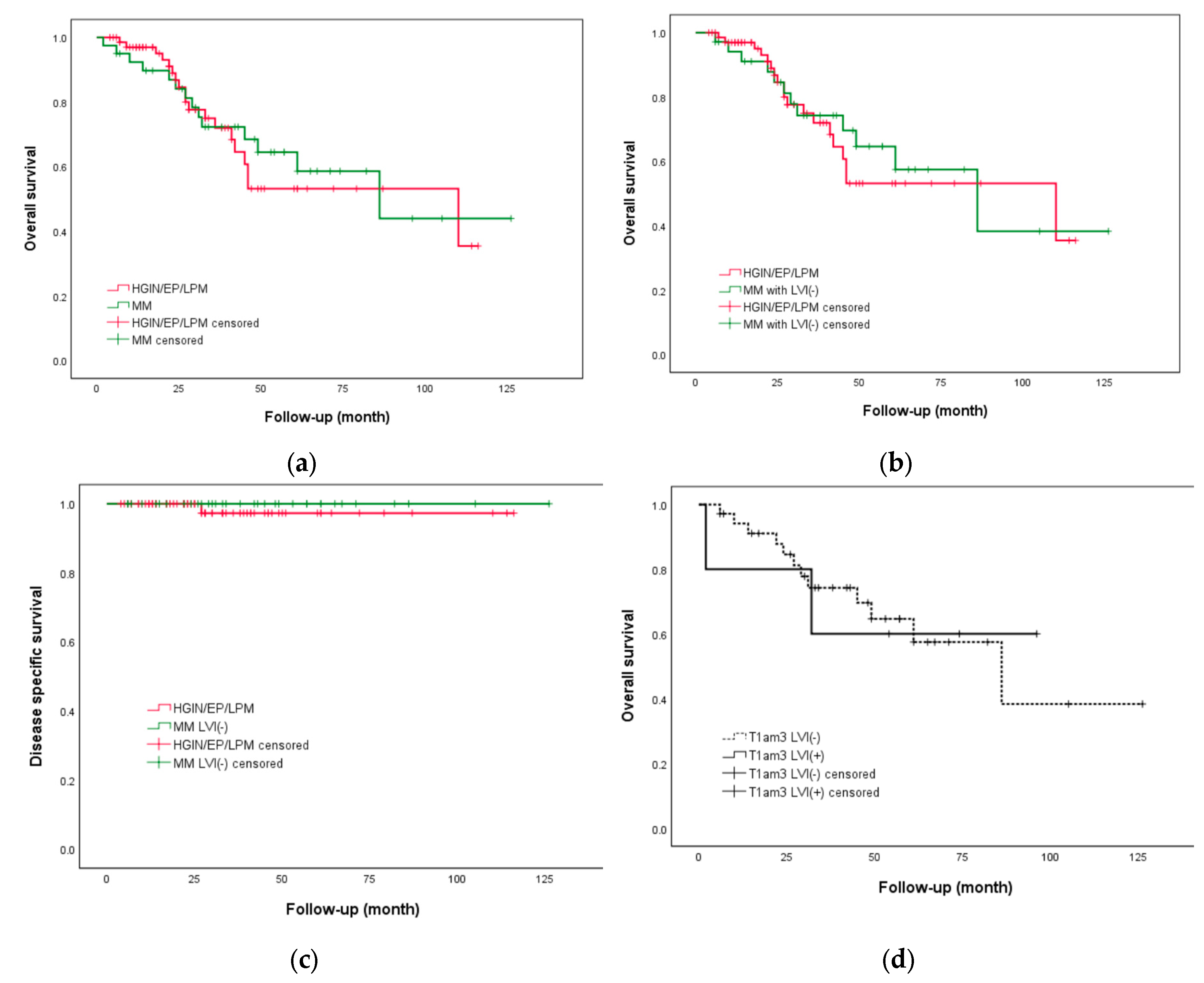

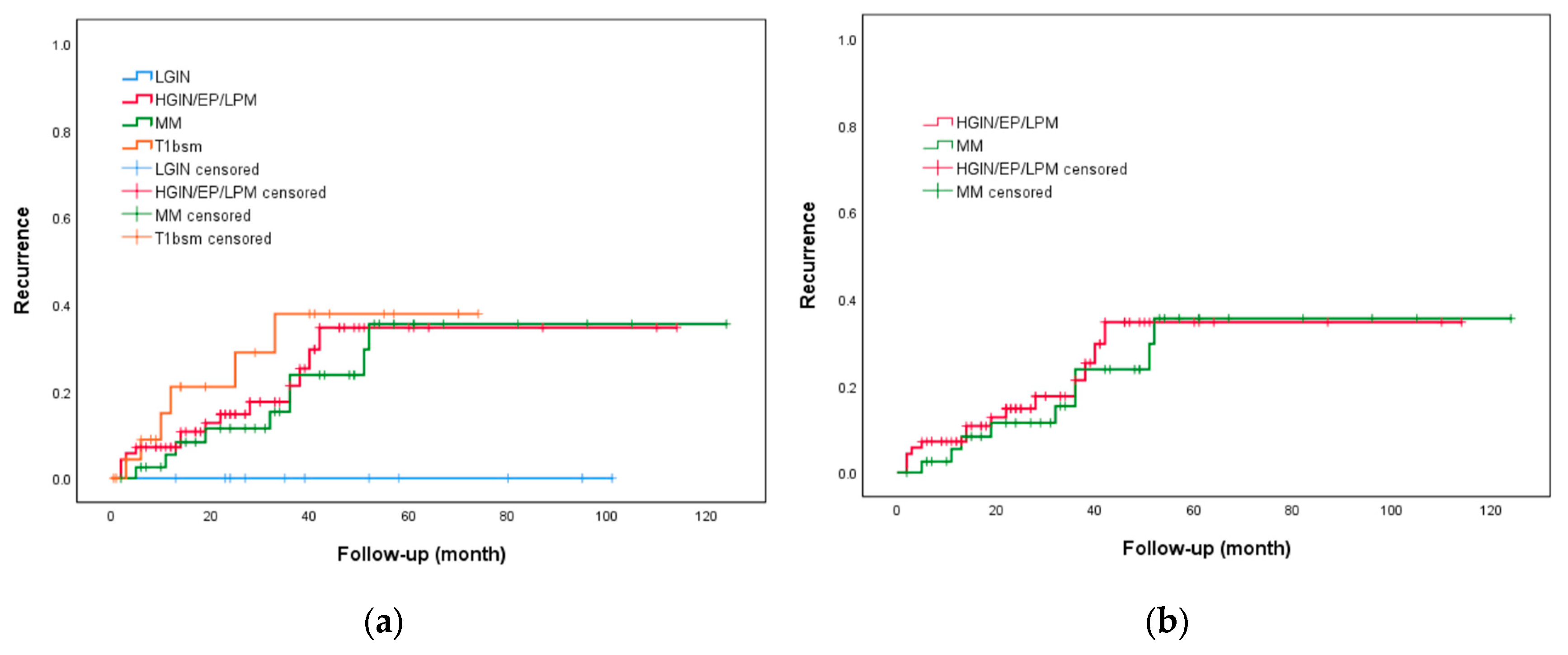

3.3. Long-Term Outcomes

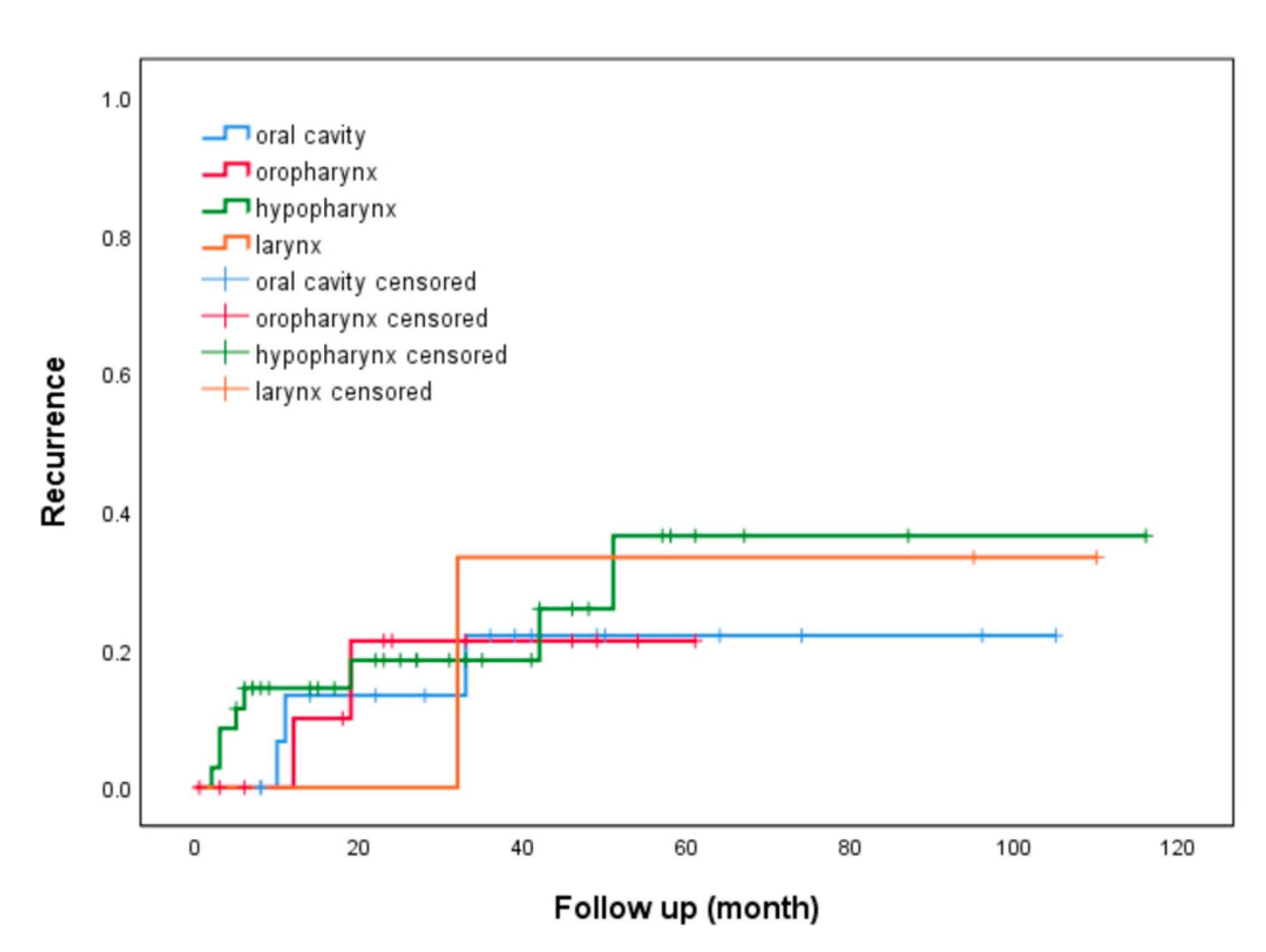

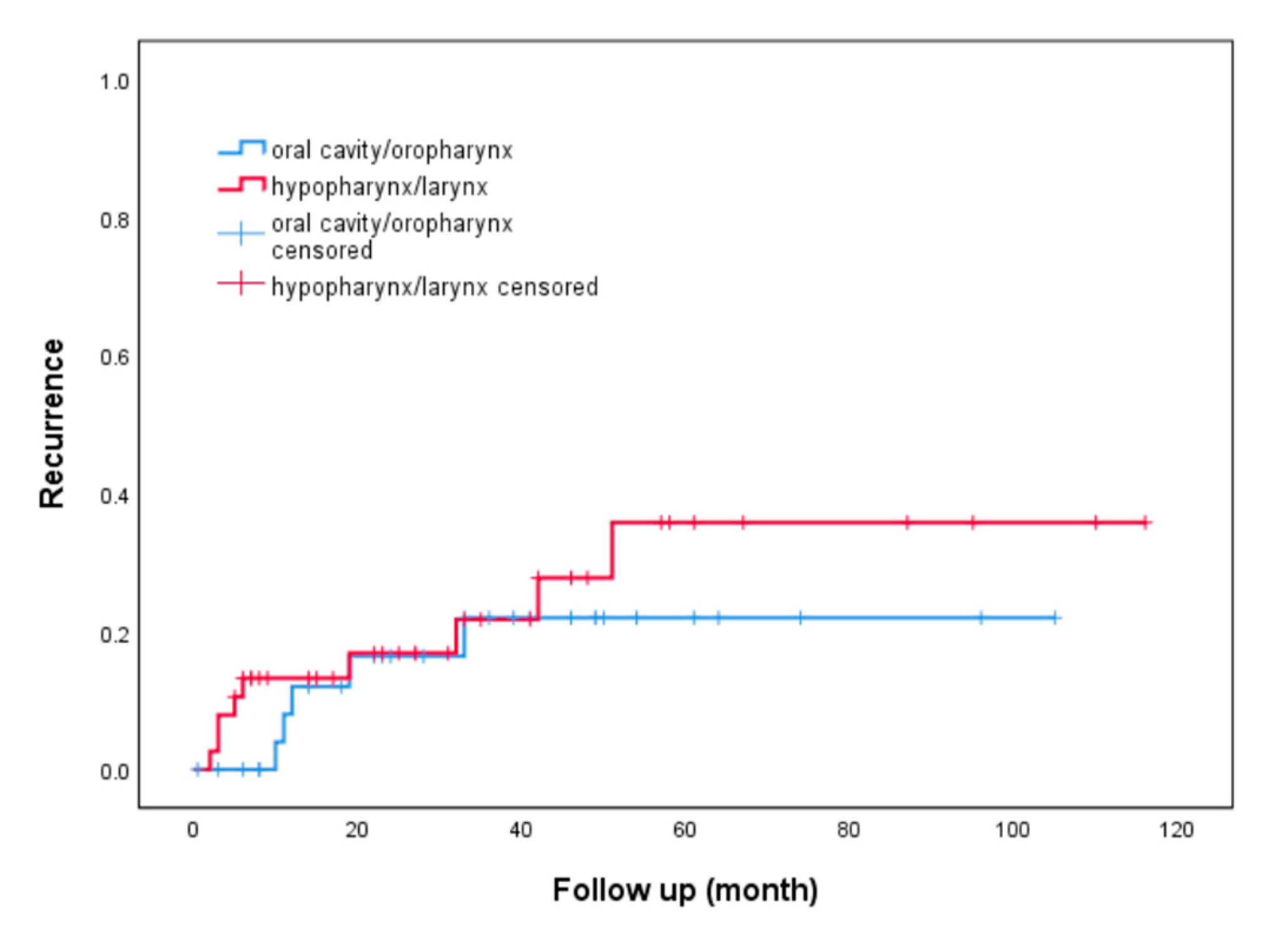

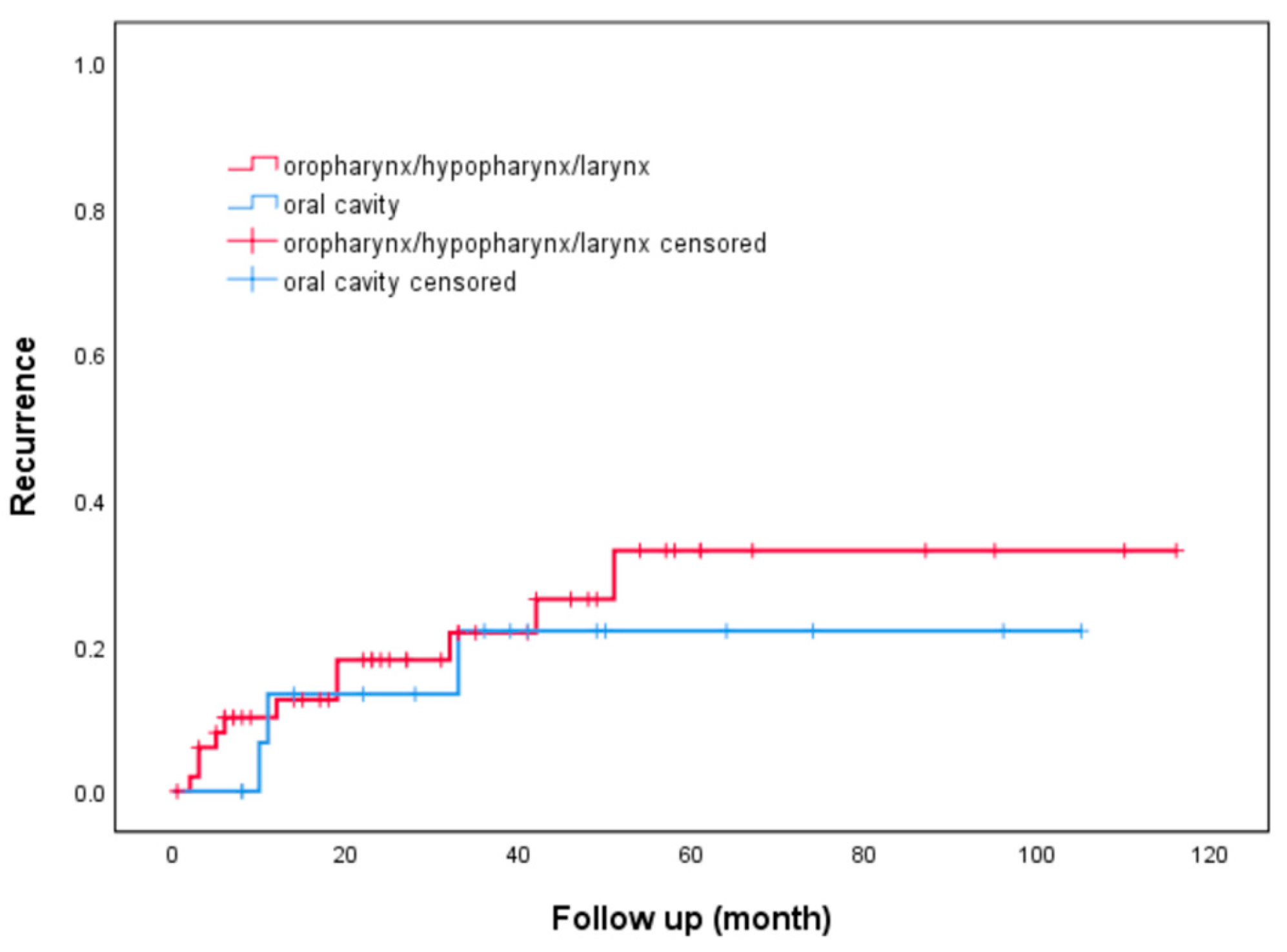

3.4. Predictors Associated with Recurrence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Location of head and neck cancer Oral cavity |

|

| 18 (24.7) | |

| Oropharynx | 13 (17.8) |

| Hypopharynx | 36 (49.3) |

| Larynx | 3 (4.1) |

| Other location1 | 3 (4.1) |

| Stage of head and neck cancer | |

| I | 5 (6.8) |

| II | 8 (11.0) |

| III | 21 (28.8) |

| IV | 39 (53.4) |

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer Pulmonary comorbidities1 |

24 (50) |

| 8 (16.7) | |

| Other cancer2 | 4 (8.3) |

| Esophageal cancer | 3 (6.3) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 2 (4.2) |

| Complication of esophagectomy | 1 (2.1) |

| Other3 | 6 (12.5) |

| Variable, Patients No. (%) | All patients (n=146) |

HN cancer (n=73) |

Without HN cancer (n=73) |

P Value (HN cancer vs without HN cancer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| 1-year | 124 (91.9) | 60 (85.7) | 64 (98.5) | 0.007 |

| 3-year | 66 (67.3) | 30 (53.6) | 36 (85.7) | 0.001 |

| 5-year | 36 (48) | 17 (37) | 19 (65.5) | 0.018 |

| Disease-specific survival | ||||

| 1-year | 134 (99.3) | 69 (98.6) | 65 (100) | 0.33 |

| 3-year | 96 (98) | 55 (98.2) | 41 (97.6) | 0.84 |

| 5-year | 71 (94.7) | 45 (97.8) | 26 (89.7) | 0.13 |

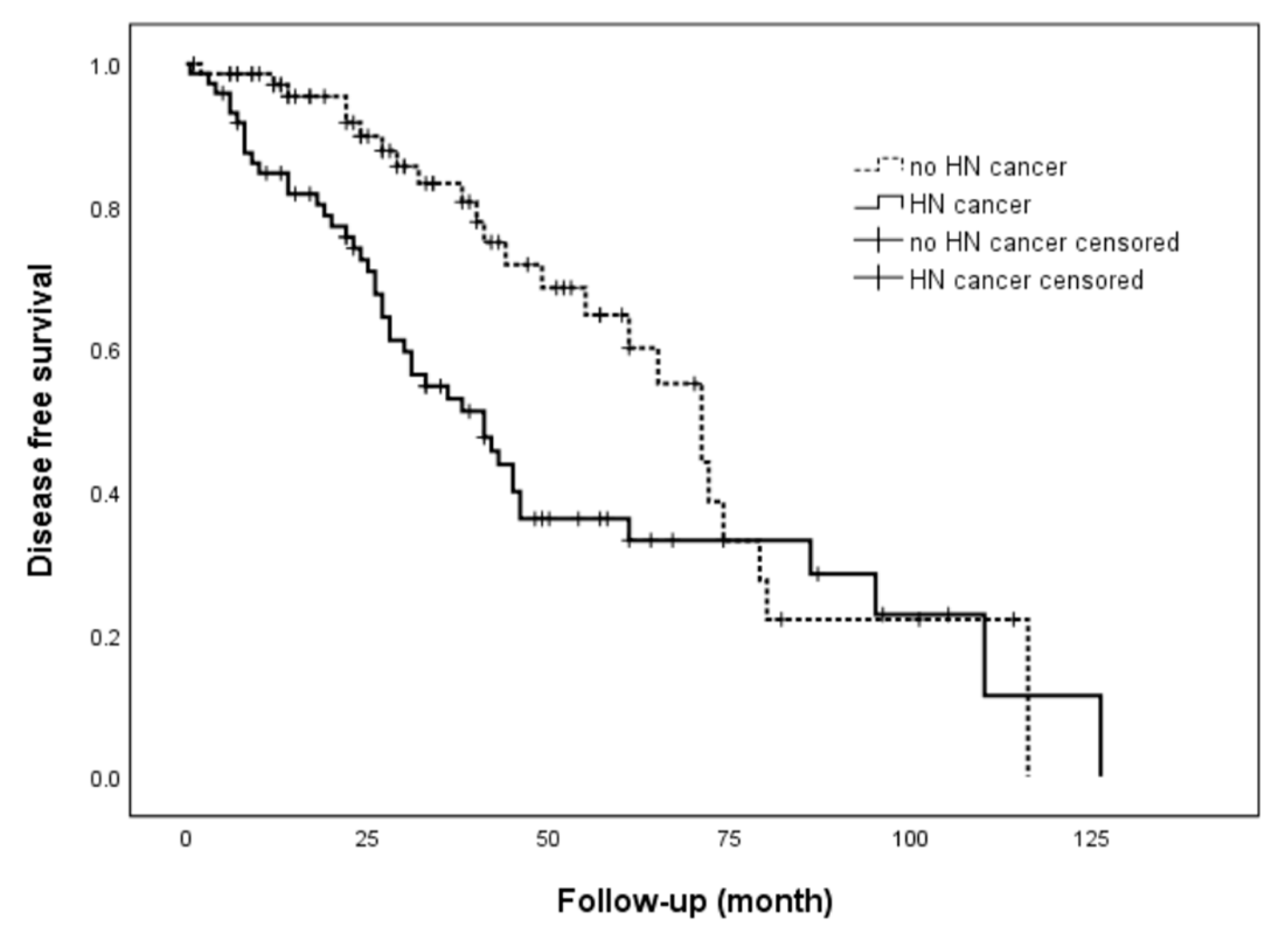

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| 1-year | 112 (83.6) | 52 (75.4) | 60 (92.3) | 0.008 |

| 3-year | 49 (51.6) | 26 (46.4) | 23 (59) | 0.23 |

| 5-year | 24 (32.9) | 14 (31.8) | 10 (34.5) | 0.81 |

| Local recurrence | 30 (20.5) | 16 (21.9) | 14 (19.2) | 0.68 |

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of additional therapy CCRT |

|

| 13 (68.4) | |

| Esophagectomy | 5 (26.3) |

| RT alone | 1 (5.3) |

| Stage | |

| HGIN | 1 (5.2) |

| T1am3 | 4 (21.1) |

| T1bsm1 | 3 (15.8) |

| T1bsm2 | 11 (57.9) |

| Reasons of additional therapy | |

| R1 resection | 8 (42.1) |

| pT1bsm2 | 5 (26.3) |

| pT1bsm1, LVI(+) | 2 (10.5) |

| pT1am3, LVI(+) | 2 (10.5) |

| pT1am3, LVI(-) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other1 | 1 (5.3) |

References

- Pennathur, A.; Gibson, M. K.; Jobe, B. A.; Luketich, J. D. , Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013, 381, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Uno, T.; Oyama, T.; Kato, K.; Kato, H.; Kawakubo, H.; Kawamura, O.; Kusano, M.; Kuwano, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Toh, Y.; Doki, Y.; Naomoto, Y.; Nemoto, K.; Booka, E.; Matsubara, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Muto, M.; Yanagisawa, A.; Yoshida, M. , Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan Esophageal Society: part 1. Esophagus 2019, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Uno, T.; Oyama, T.; Kato, K.; Kato, H.; Kawakubo, H.; Kawamura, O.; Kusano, M.; Kuwano, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Toh, Y.; Doki, Y.; Naomoto, Y.; Nemoto, K.; Booka, E.; Matsubara, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Muto, M.; Yanagisawa, A.; Yoshida, M. , Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 2. Esophagus 2019, 16, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölscher, A. H.; Bollschweiler, E.; Schröder, W.; Metzger, R.; Gutschow, C.; Drebber, U. , Prognostic impact of upper, middle, and lower third mucosal or submucosal infiltration in early esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 2011, 254, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Singh, V.; Fleischer, D. E.; Sharma, V. K. , A comparison of endoscopic treatment and surgery in early esophageal cancer: an analysis of surveillance epidemiology and end results data. Am J Gastroenterol 2008, 103, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, H.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W. F.; Li, Q.; Yao, L.; Korrapati, P.; Jin, X. J.; Zhang, Y. X.; Xu, M. D.; Zhou, P. H. , Outcomes of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection vs Esophagectomy for T1 Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Real-World Cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 17, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashina, T.; Ishihara, R.; Nagai, K.; Matsuura, N.; Matsui, F.; Ito, T.; Fujii, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Hanaoka, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Higashino, K.; Uedo, N.; Iishi, H. , Long-term outcome and metastatic risk after endoscopic resection of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2013, 108, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagami, Y.; Ominami, M.; Shiba, M.; Minamino, H.; Fukunaga, S.; Kameda, N.; Sugimori, S.; Machida, H.; Tanigawa, T.; Yamagami, H.; Watanabe, T.; Tominaga, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; Arakawa, T. , The five-year survival rate after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasia. Dig Liver Dis 2017, 49, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, I.; Shimizu, Y.; Yoshio, T.; Katada, C.; Yokoyama, T.; Yano, T.; Suzuki, H.; Abiko, S.; Takemura, K.; Koike, T.; Takizawa, K.; Hirao, M.; Okada, H.; Yoshii, T.; Katagiri, A.; Yamanouchi, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Kawakubo, H.; Kobayashi, N.; Shimoda, T.; Ochiai, A.; Ishikawa, H.; Yokoyama, A.; Muto, M. , Long-term outcome of endoscopic resection for intramucosal esophageal squamous cell cancer: a secondary analysis of the Japan Esophageal Cohort study. Endoscopy 2020, 52, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, N.; Dohi, O.; Yamada, S.; Ishida, T.; Fukui, A.; Horie, R.; Yasuda, T.; Yamada, N.; Horii, Y.; Majima, A.; Zen, K.; Yagi, N.; Naito, Y.; Itoh, Y. , Clinical Outcomes of Follow-Up Observation After Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Invading the Muscularis Mucosa Without Lymphovascular Involvement. Dig Dis Sci 2023, 68, 3679–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Santiago, E.; van Tilburg, L.; Deprez, P. H.; Pioche, M.; Pouw, R. E.; Bourke, M. J.; Seewald, S.; Weusten, B.; Jacques, J.; Leblanc, S.; Barreiro, P.; Lemmers, A.; Parra-Blanco, A.; Küttner-Magalhães, R.; Libânio, D.; Messmann, H.; Albéniz, E.; Kaminski, M. F.; Mohammed, N.; Zabala, F. R.; Herreros-de-Tejada, A.; Koecklin, H. U.; Wallenhorst, T.; Santos-Antunes, J.; Cunha Neves, J. A.; Koch, A. D.; Ayari, M.; Duran, R. G.; Ponchon, T.; Rivory, J.; Bergman, J.; Verheij, E. P. D.; Gupta, S.; Groth, S.; Lepilliez, V.; Franco, A. R.; Belkhir, S.; White, J.; Ebigbo, A.; Probst, A.; Legros, R.; Pilonis, N. D.; de Frutos, D.; González, R. M.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M. , Western outcomes of circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M. H.; Wang, W. L.; Chen, T. H.; Tai, C. M.; Wang, H. P.; Lee, C. T. , Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterol 2021, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. S.; Liao, L. J.; Lo, W. C.; Chou, Y. H.; Chang, Y. C.; Lin, Y. C.; Hsu, W. F.; Shueng, P. W.; Lee, T. H. , Risk factors for second primary neoplasia of esophagus in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. K.; Chuang, Y. S.; Wu, T. S.; Lee, K. W.; Wu, C. W.; Wang, H. C.; Kuo, C. T.; Lee, C. H.; Kuo, W. R.; Chen, C. H.; Wu, D. C.; Wu, I. C. , Endoscopic screening for synchronous esophageal neoplasia among patients with incident head and neck cancer: Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. Int J Cancer 2017, 141, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. S.; Lo, W. C.; Wen, M. H.; Hsieh, C. H.; Lin, Y. C.; Liao, L. J. , Long Term Outcome of Routine Image-enhanced Endoscopy in Newly Diagnosed Head and Neck Cancer: a Prospective Study of 145 Patients. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. H.; Ho, C. M.; Wu, M. S.; Hsu, W. H.; Wang, W. Y.; Yuan, S. F.; Hsieh, H. M.; Wu, I. C. , Effect of esophageal cancer screening on mortality among patients with oral cancer and second primary esophageal cancer in Taiwan. Am J Otolaryngol 2023, 44, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.-S.; Wu, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lo, W.-C.; Cheng, P.-C.; Hsu, W.-L.; Liao, L.-J. , Screening and surveillance of esophageal cancer by magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging improves the survival of hypopharyngeal cancer patients. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, T.; Inoue, H.; Arima, M.; Momma, K.; Omori, T.; Ishihara, R.; Hirasawa, D.; Takeuchi, M.; Tomori, A.; Goda, K. , Prediction of the invasion depth of superficial squamous cell carcinoma based on microvessel morphology: magnifying endoscopic classification of the Japan Esophageal Society. Esophagus 2017, 14, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y.; Omori, T.; Yokoyama, A.; Yoshida, T.; Hirota, J.; Ono, Y.; Yamamoto, J.; Kato, M.; Asaka, M. , Endoscopic diagnosis of early squamous neoplasia of the esophagus with iodine staining: high-grade intra-epithelial neoplasia turns pink within a few minutes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008, 23, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus 2017, 14, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Wright, C. D.; Kucharczuk, J. C.; O'Brien, S. M.; Grab, J. D.; Allen, M. S. , Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009, 137, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, L. M.; Gawande, A. A.; Semel, M. E.; Lipsitz, S. R.; Berry, W. R.; Zinner, M. J.; Jha, A. K. , Esophagectomy outcomes at low-volume hospitals: the association between systems characteristics and mortality. Ann Surg 2011, 253, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujii, Y.; Nishida, T.; Nishiyama, O.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawai, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamada, T.; Yoshio, T.; Kitamura, S.; Nakamura, T.; Nishihara, A.; Ogiyama, H.; Nakahara, M.; Komori, M.; Kato, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Shinzaki, S.; Iijima, H.; Michida, T.; Tsujii, M.; Takehara, T. , Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy 2015, 47, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, T.; Kikuchi, D.; Hoteya, S.; Kajiyama, Y.; Kaise, M. , Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial cancer of the cervical esophagus. Endosc Int Open 2017, 5, E736–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyonaga, T.; Man-i, M.; East, J. E.; Nishino, E.; Ono, W.; Hirooka, T.; Ueda, C.; Iwata, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Dozaiku, T.; Hirooka, T.; Fujita, T.; Inokuchi, H.; Azuma, T. , 1,635 Endoscopic submucosal dissection cases in the esophagus, stomach, and colorectum: complication rates and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 2013, 27, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z. P.; Chen, T.; Li, B.; Ren, Z.; Yao, L. Q.; Shi, Q.; Cai, S. L.; Zhong, Y. S.; Zhou, P. H. , Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal cancer in elderly patients with relative indications for endoscopic treatment. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephant, S.; Jacques, J.; Brochard, C.; Legros, R.; Lepetit, H.; Barret, M.; Lupu, A.; Rostain, F.; Rivory, J.; Ponchon, T.; Pioche, M.; Wallenhorst, T. , High proficiency of esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection with a "tunnel + clip traction" strategy: a large French multicentric study. Surg Endosc 2023, 37, 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.; Ebigbo, A.; Eser, S.; Fleischmann, C.; Schaller, T.; Märkl, B.; Schiele, S.; Geissler, B.; Müller, G.; Messmann, H. , Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: long-term follow-up in a Western center. Clin Endosc 2023, 56, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Arimura, Y.; Masao, H.; Okahara, S.; Tanuma, T.; Kodaira, J.; Kagaya, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Hokari, K.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Shinomura, Y.; Fujita, M. , Endoscopic submucosal dissection is superior to conventional endoscopic resection as a curative treatment for early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2010, 72, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollar, M.; Krajciova, J.; Prefertusová, L.; Sticova, E.; Malušková, J.; Pazdro, A.; Harustiak, T.; Kodetova, D.; Vackova, Z.; Spicak, J.; Martínek, J. , Su1124 – Long Term Results of Endoscopic Treatment Vs. Esophagectomy with Lymphadenectomy in Patients with High-Risk Early Esophageal Cancer Including Detailed Analysis of Lymph Node Micrometastases. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, S–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, O.; Behrens, A.; May, A.; Nachbar, L.; Gossner, L.; Rabenstein, T.; Manner, H.; Guenter, E.; Huijsmans, J.; Vieth, M.; Stolte, M.; Ell, C. , Long-term results and risk factor analysis for recurrence after curative endoscopic therapy in 349 patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and mucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus. Gut 2008, 57, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katada, C.; Yokoyama, T.; Yano, T.; Kaneko, K.; Oda, I.; Shimizu, Y.; Doyama, H.; Koike, T.; Takizawa, K.; Hirao, M.; Okada, H.; Yoshii, T.; Konishi, K.; Yamanouchi, T.; Tsuda, T.; Omori, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Shimoda, T.; Ochiai, A.; Amanuma, Y.; Ohashi, S.; Matsuda, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Yokoyama, A.; Muto, M. , Alcohol Consumption and Multiple Dysplastic Lesions Increase Risk of Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Esophagus, Head, and Neck. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minashi, K.; Nihei, K.; Mizusawa, J.; Takizawa, K.; Yano, T.; Ezoe, Y.; Tsuchida, T.; Ono, H.; Iizuka, T.; Hanaoka, N.; Oda, I.; Morita, Y.; Tajika, M.; Fujiwara, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Katada, C.; Hori, S.; Doyama, H.; Oyama, T.; Nebiki, H.; Amagai, K.; Kubota, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Suzuki, T.; Hirasawa, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Fukuda, H.; Muto, M. , Efficacy of Endoscopic Resection and Selective Chemoradiotherapy for Stage I Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Lesion No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics Age (mean ± SD), years |

|

| 59.17 ± 9.45 | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 130 (89) |

| Female | 16 (11) |

| Smoking | 125 (85.6) |

| Alcohol drinker | 132 (90.4) |

| Betel nut chewing | 64 (43.8) |

| Smoking cessation | 48 (38.4) |

| Alcohol abstinence | 91 (68.9) |

| Betel nut cessation | 45 (70.3) |

| HN cancer history | 73 (50) |

| Endoscopic characteristics | |

| Tumor location | |

| Upper third of the esophagus | 24 (13.1) |

| Middle third of the esophagus | 102 (55.7) |

| Lower third of the esophagus | 57 (31.1) |

| Endoscopic tumor size (mean ± SD), cm | 2.48 ± 1.90 |

| Circumference of the tumor | |

| < 1/2 | 71 (38.8) |

| < 3/4 | 140 (76.5) |

| ≥ 3/4 | 43 (23.5) |

| JES type | |

| B1 | 140 |

| LGIN/HGIN/T1am1/T1am2 | 109 (77.9) |

| T1am3/ T1bsm1 | 28 (20) |

| T1bsm2 | 3 (2.1) |

| B2 | 43 |

| LGIN/HGIN/T1am1/T1am2 | 7 (16.3) |

| T1am3/ T1bsm1 | 24 (55.8) |

| T1bsm2 | 12 (27.9) |

| Pathological characteristics | |

| Histological subtype | |

| Well differentiated (G1) | 18 (23.3) |

| Moderately differentiated (G2) | 55 (71.4) |

| Poorly differentiated (G3) | 4 (5.1) |

| LVI | 14 (7.6) |

| Perineural invasion | 3 (1.6) |

| Pathologic stage | |

| LGIN | 16 (8.7) |

| HGIN/T1am1 | 90 (49.1) |

| T1am2 | 10 (5.5) |

| T1am3 | 42 (23) |

| T1bsm1 | 10 (5.5) |

| T1bsm2 | 15 (8.2) |

| Variable | Lesion No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Short term outcomes En bloc resection, lesions No. (%) |

|

| 183 (100) | |

| R0 resection, lesions No. (%) | 175 (95.6) |

| Complete local remission, lesions No. (%) | 161 (88) |

| Overall post-ESD AE | 18 (9.8) |

| Stricture | 18 (9.8) |

| Bleeding | 0 |

| Perforation | 0 |

| Long term outcomes | |

| Mean follow-up period (mean ± SD), month | 37.05 ± 26.79 |

| Overall survival | |

| 1-year | 124 (91.9) |

| 3-year | 66 (67.3) |

| 5-year | 36 (48) |

| Disease-specific survival | |

| 1-year | 134 (99.3) |

| 3-year | 96 (98) |

| 5-year | 71 (94.7) |

| Recurrence | 30 (20.5) |

| Local recurrence | 16 (11.0) |

| Metachronous recurrence | 14 (9.5) |

| Time to recurrence (mean ± SD), month | 24.50 ± 24.31 |

| Recurrence | Non-recurrence | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=30) | (n=116) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Males | 27 (90%) | 103 (89%) | 0.85 | 1.14 (0.30-4.27) | ||

| Age (mean±SD), years | 56.63±9.59 | 59.83±9.34 | 0.10 | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | ||

| Smoking | 26 (87%) | 99 (85%) | 0.85 | 1.12 (0.35-3.60) | ||

| Alcohol | 30 (100%) | 102 (88%) | ||||

| Betel nut | 15 (50%) | 49 (42%) | 0.45 | 1.37 (0.61-3.06) | ||

| Smoking cessation | 13 (50%) | 35 (35%) | 0.17 | 1.82 (0.76-4.37) | ||

| Alcohol abstinence | 12 (40%) | 79 (78%) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.08-0.46) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.08-0.48) |

| Betel nut cessation | 11 (73%) | 34 (69%) | 0.77 | 1.21 (0.33-4.43) | ||

| HN cancer | 16 (53%) | 57 (49%) | 0.68 | 1.18 (0.53-2.64) | ||

| Oral cavity cancer | 3 (19%) | 15 (26%) | 0.57 | 0.67 (0.17-2.70) | ||

| HPC and laryngeal cancer | 10 (63%) | 30 (53%) | 0.49 | 1.50 (0.48-1.68) | ||

| LVI | 5 (17%) | 9 (8%) | 0.15 | 2.38 (0.73-7.71) | ||

| Perineural invasion | 0 | 3 (3%) | ||||

| T1am3/T1bsm | 16 (53%) | 49 (42%) | 0.28 | 1.56 (0.70-3.50) | ||

| T1bsm | 6 (20%) | 19 (16%) | 0.64 | 1.28 (0.46-3.54) | ||

| Histology subtype G2/G3 | 13 (62%) | 45 (76%) | 0.21 | 0.51 (0.17-1.47) | ||

| Histology subtype G3 | 0 | 4 (3%) | ||||

| Endoscopy tumor size (mean±SD),cm | 3.60±2.01 | 3.23±2.18 | 0.41 | 1.08 (0.90-1.29) | ||

| Circumference over 3/4 | 8 (27%) | 30 (26%) | 0.93 | 1.04 (0.42-2.59) | ||

| Circumference over 1/2 | 23 (77%) | 78 (67%) | 0.32 | 1.60 (0.63-4.06) | ||

| R0 resection | 26 (87%) | 112 (97%) | 0.05 | 0.23 (0.05-0.99) | 0.31 | 0.36 (0.05-2.60) |

| CLR | 22 (73%) | 103 (89%) | 0.04 | 0.35 (0.13-0.94) | 0.56 | 0.66 (0.17-2.63) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).