1. Introduction

Results-based financing (RBF) is a funding approach that links financial resources to attaining specific results or outcomes rather than the quantity of assistance provided, emphasizing payment for performance. The system incentivizes healthcare providers to deliver services of high quality and achieve health results, usually through a formal contract between the funder (e.g., government, donor, or health insurance organization) and the healthcare providers, with payments contingent on the outcomes reached. In contrast, conventional funding mechanisms often concentrate on input indicators like the number of healthcare facilities constructed or equipment procured rather than health outcomes such as decreased disease prevalence or enhanced patient well-being.

This approach incentivizes healthcare providers to deliver high-quality assistance and achieve health results. Song et al. (2024) support this.

Reengineering pediatric services with RBF involves restructuring healthcare delivery systems to improve efficiency, quality, and patient outcomes, particularly in under-resourced areas like Northern Uganda.

Like various regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, healthcare systems face many challenges. They grapple with numerous challenges, ranging from scarce resources and inadequate staffing to the heavy burden of diseases afflicting the region. Pediatric assistance, essential for reducing child mortality and improving children’s health outcomes, is particularly affected.

Evidence from the implementation of RBF in Northern Uganda (see CEHURD, 2021) shows that a significant benefit is the enhancement of health outcomes facilitated by RBF mechanisms. These mechanisms incentivize healthcare providers to achieve quantifiable health results, ultimately enhancing critical indicators such as maternal and child mortality rates, control of infectious diseases, and the population’s overall health status. Moreover, RBF encourages the efficient utilization of resources by connecting payments to outcomes rather than inputs. This linkage promotes efficiency and accountability in allocating resources, ensuring funds are channeled toward interventions that significantly impact health outcomes.

Despite its potential advantages, healthcare professionals operating within underprivileged environments encounter many obstacles, such as restricted financial resources, insufficient facilities, a need for more adequately trained personnel, and barriers to organization and coordination. These challenges can impede the delivery of quality healthcare assistance and contribute to poor health outcomes. RBF has the potential to address these challenges by providing financial incentives for providers to overcome barriers to access, invest in infrastructure and equipment, recruit and retain skilled staff, and improve the quality of care delivery.

Within this framework, the paper’s research question is to examine the challenges faced by healthcare providers in under-resourced settings and the potential of RBF to address these issues, investigating the Long-Term Effects of RBF Intervention in Children’s Wards in two main Northern Uganda hospitals (Lacor and Kalongo) in a pre-and post-Covid timeframe, from 2018 to 2024.

The study conforms to an IMRAD pattern and is structured as follows: After a short literature analysis, we present a model backed by empirical findings that precede a discussion and conclusion.

2. Literature Analysis and Gaps

The design of RBF schemes in LMICs should allow for iterative modifications during implementation to ensure effectiveness and sustainability.

The study by Fondazione Corti, Lacor Hospital, and Fondazione Ambrosoli (2021) highlights the need for further exploration in areas such as Artificial Intelligence applications, sensitivity analyses in unique contexts, and fine-tuned benchmarking with standard cost/quality comparables to address existing research gaps and pave the way for future investigations.

There is a comprehensive literature analysis, mostly dating back to the last 15/20 years, documenting the practical applications of healthcare RBF (Grittner et al., 2013; Moro-Visconti, 2024; Nkangu et al., 2023).

Anthony et al., 2017 found that the verification processes of RBF schemes in many African countries are complex, costly, and time-consuming. The design of RBF schemes should adapt to the context, and there should be room for iterative modifications during implementation.

RBF schemes in LMICs are, for instance, examined by Bean et al., 2013, Brenner et al., 2014, Brenner et al., 2018, Falisse et al., 2015, Friedman et al., 2016, James et al., 2020, Kuunibe et al., 2020, Manongi et al., 2014, Oxman and Fretheim, 2008, Soeters et al., 2011, Turcotte-Tremblay et al., 2016, Witter et al., 2019, Zeng et al., 2018.

Mathonnat and Pelissier, 2017 link the RBF approach to developing countries’ efforts to achieve health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Accessibility to First-Mile health assistance in Uganda is examined by Moro-Visconti et al., 2020.

Mushasha and El Bcheraoui (2023) show that results-based approaches positively impact institutional delivery rates and the number of healthcare facility visits. However, this impact varies greatly by context, and it is essential to include rigorous monitoring and evaluation strategies when designing financing models.

Fondazione Corti, Lacor Hospital, and Fondazione Ambrosoli (2021) illustrate a pre-COVID RBF test of pediatric assistance in the two target hospitals (Lacor and Kalongo). This study represents an update of this test with further theoretical and empirical considerations.

This paper fills some research gaps, showing an empirical comparison of these two major hospitals in a difficult environment, plagued by twenty years of civil war (1986-2006) (Annan et al., 2011) and infectious diseases such as Ebola outbreaks (mainly in 2000), endemic malaria, TBC and AIDS. On-field evidence compares data from 2018 to 2024, passing through the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research lacunae may include Artificial Intelligence applications, sensitivity analyses in peculiar contexts, fine-tuned benchmarking with standard cost/quality comparable, etc. These can represent new research avenues.

3. The Model

The RBF intervention in Uganda, implemented jointly by various NGOs and the Ugandan Government, aims to evaluate its efficacy both during its implementation period and in the medium to long term after the intervention ceases.

The ongoing quarterly evaluations play a crucial role in assessing the immediate impact of the RBF intervention on beneficiaries. These evaluations, conducted regularly, provide real-time feedback on the effectiveness of the intervention, helping stakeholders make informed decisions and adjustments as needed. The medium to long-term evaluation phase focuses on understanding the sustained influence and efficiency of the RBF initiative beyond its active period. By delving into the lasting effects of the intervention, researchers aim to capture the true long-term benefits and changes brought about by the program in the specified regions. Engaging in follow-up surveys or interviews with beneficiaries offers valuable insights into the lasting impact of the RBF intervention.

By gathering feedback directly from those who benefited from the program, researchers can assess the continued effects on behaviors and outcomes, providing a comprehensive understanding of the intervention’s enduring legacy. Crafting a strong and resilient framework for gathering data and utilizing suitable statistical methods are crucial components in guaranteeing the accuracy and dependability of the assessment procedure. These steps lay the foundation for a thorough and meticulous evaluation process. By maintaining consistency with initial evaluation methods and addressing potential confounding variables, researchers can draw accurate conclusions about the long-term impact of the RBF intervention.

Here is a breakdown of the key points and potential steps for the evaluation:

Initial Evaluation (During Implementation):

∙

Quarterly evaluations measure the results achieved by beneficiaries.

∙

These evaluations should cover various metrics agreed upon with the stakeholders, including staff from Children’s wards and the administration of hospitals like Lacor and Kalongo.

∙

Data from these evaluations should be collected, analyzed, and compared against predetermined targets or benchmarks to assess the effectiveness of the RBF intervention during its active phase.

∙

2. Medium to Long-Term Evaluation (Four Years Post-Intervention):

∙

This stage encompasses a thorough assessment of the RBF initiative’s long-lasting influence and efficiency, extending beyond its official completion, to delve into its enduring implications and outcomes in the targeted areas.

∙

Since long-term data are scarce, it is essential to design a strategy to gather relevant data over the four years following the end of the intervention.

∙

Potential data sources could encompass a variety of avenues for gathering information. One such avenue involves conducting follow-up surveys or interviews with beneficiaries to assess any lasting benefits or behavioral changes that may have stemmed from the initial intervention or program. These follow-up interactions gauge the intervention’s sustained impact over time. Moreover, data on health outcomes retrieved from hospitals can be instrumental in determining whether the positive changes observed during the intervention phase have persisted or if there have been any setbacks. By analyzing economic data, researchers can uncover any ripple effects and advantages that the intervention may have catalyzed across different sectors of the economy. Furthermore, qualitative assessments are indispensable in capturing a comprehensive range of perspectives and firsthand experiences from individuals or groups closely involved in the intervention.

∙

3. Methodology and Analysis:

∙

Develop a robust methodology for data collection, ensuring consistency with the initial evaluation methods where applicable.

∙

Employ appropriate statistical analysis techniques to compare data collected during the intervention period with data from the medium to long-term evaluation.

∙

Consider potential confounding variables or factors that may influence outcomes post-intervention and introduce bias or obscure the intervention’s true impact, requiring a thorough evaluation and adjustment of the analysis to ensure accurate and reliable conclusions. Failure to address these variables could lead to inaccurate conclusions and flawed results.

∙

4. Reporting and Recommendations:

Prepare a thorough and detailed report encompassing the results derived from evaluations conducted in both the short-term and medium- to long-term periods, ensuring that all pertinent data and analyses allow for a comprehensive overview. This report should encapsulate essential revelations about the efficiency of the RBF intervention over time, encompassing any enduring advantages or aspects that require enhancements. Additionally, it should offer suggestions for forthcoming interventions or policy modifications based on the outcomes observed, aiming to optimize impact and ensure longevity in analogous scenarios. The recommendations should be grounded in the insights from the evaluations, aiming to foster continuous improvement and effectiveness in future endeavors.

By conducting thorough evaluations during and after the active phase of the RBF intervention, stakeholders can gain valuable insights into its effectiveness and inform future decision-making and resource allocation strategies.

Inizio Modulo

Various NGOs and the Ugandan Government have selected RBF to evaluate the efficacy of financing based on the verified results reached at definite intervals by the beneficiaries. Several studies proved the efficacy of this intervention while it was in place, i.e., during the actual verification and reward. However, the real effectiveness of these interventions needs consideration after they stop: long-term data are indeed scarcely, if ever, available.

This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of an RBF intervention during the three years of action (quarterly evaluation) and in the medium-long term (four years after the stop).

All the staff of the Children’s wards and the administration of the two hospitals, Lacor and Kalongo, agreed upon the RBF targets.

The starting period. A target for quality improvements in the children’s ward is reported in the Ambrosoli and Lacor Foundation (2024) repository. This repository contains:

After a baseline evaluation at time 0, every three months, a commission with internal and external reviewers assigned a quality score to each of 5 domains (structure and management, Hygiene, Clinical work, Emergency, and training): staff received a financial reward according to the % of target score reached in that quarter. To evaluate the actual impact on the care of children in the two wards of Lacor and Kalongo, an independent evaluator team screened clinical charts two years before the RBF (2016), at the end of RBF (2020), and four years after the end (2024).

The study design is the following:

Prospective observational study.

Process and health indicators in the years before the intervention.

Process and health indicators at the end of the intervention.

Progress of quality scores over time.

Process and health indicators four years after the end of the intervention.

At Lacor and Kalongo Hospital, an external commission visited the Children’s wards every quarter and scrupulously examined structures, administration, and procedures within each of these domains to be evaluated and to which assign the relevant numeric scores.

The figures show the trend over time from Time 0 (2018) to quarter 12 (2020) and four years after the stop (2024).

We fit Linear regression or 2nd-degree polynomials to the raw data.

Analysis of variance was adopted to estimate the difference among average clinical scores across hospitals and years of assessment. Canonical discriminant analysis selects the clinical administration variable that discriminated more in performance in 2018 (start of RBF) than in the end (2020). Wilk’s lambda estimates the capacity of each variable to distinguish between the two years in a multivariate fashion after considering all other variables, where Wilks 1 = complete overlap between the two years and 0 = complete distance.

The long-run extension. Ambrosoli and Lacor Foundations (2024) repository contains a checklist of qualitative items collected retrospectively (year 2016) and prospectively (years 2020 and 2024). They are concerned about adherence to the protocols for the diseases subjected to revision.

A second section of the study contains a report on the quality assessment of the clinical administration of sick children before and after the RBF project and in the long run. The target is to compare the clinical management of children admitted for more than 48 hours in both hospitals’ children’s wards before RBF (the year 2016), after the three years of RBF (the year 2020), and four years after the stop of the project (2024). An independent quality officer scrutinized a large series of clinical records of the three time periods from each hospital to compare two indicators from the RBF checklist regarding proper diagnosis and therapy. We recorded the date of admission and discharge from each clinical record, the child’s age, and the final diagnosis. For each checklist item, a score shows the fulfillment of the single item (presence of information, complete and clear information, done according to WHO protocol).

| 0 = N.A. (missing or not applicable) |

| -1 = Absent, not done, not according to guidelines |

| 1 = present, done, but unclear |

| 3 = present, done, done according to guidelines |

Summing the scores for history, examination, weight, treatment, and antibiotics obtained an overall ‘Clinical management’ score.

Since the items are correlated, we may offer an overenthusiastic view of the achieved results. For this reason, a multivariate analysis found which variable more efficiently differentiated the management of patients between 2016 (before RBF) and 2020 (after). A stepwise Canonical Discriminant analysis model selects the best items that could discriminate between the two periods.

4. Results

The investigation examines treatment efficacy and patient recovery in Lacor Hospital’s Ward and assesses improvements in treatment modalities and patient recovery at Kalongo Hospital. The analysis includes a detailed look at the percentage of target scores and hygiene practices. The study explores the maintenance of target scores post-project implementation and performance sustainability over time.

To effectively analyze and interpret the results of implementing RBF in pediatric assistance at Lacor and Kalongo Hospitals, the findings consider two distinct sections:

Lacor Hospital’s ward

Kalongo Hospital’s ward

Lacor Hospital’s clinical management

Kalongo Hospital’s clinical management

Quality Assessment Before and After the RBF Project in both hospitals

This structure facilitates a clear understanding of RBF’s impact on various aspects of healthcare delivery. It allows for a comprehensive evaluation of its effectiveness in improving pediatric healthcare in these under-resourced settings.

By categorizing the outcomes into these specific divisions, individuals involved can acquire a more intricate comprehension of the effects of RBF on providing healthcare assistance for children in the northern region of Uganda. An in-depth examination of this nature could shed light on the advantages and limitations of implementing the RBF approach within these environments, presenting essential insights and tactics for expanding upon or customizing the model for comparable situations worldwide. This breakdown of the results allows for a thorough exploration of the intricacies of utilizing RBF in pediatric healthcare delivery in Northern Uganda, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the implications and the potential for broader application in diverse global settings.

Lacor Hospital’s Ward. The pediatric ward of Lacor Hospital, known as the Lacor Hospital’s Ward, is the primary focus of this analysis, along with Kalongo. This investigation will explore specific health outcomes associated with prevalent pediatric illnesses managed in the ward, including malaria, respiratory infections, and malnutrition, to evaluate enhancements in the efficacy of treatment modalities and the recovery of patients. By examining these factors comprehensively, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of RBF on the pediatric care assistance offered at Lacor Hospital.

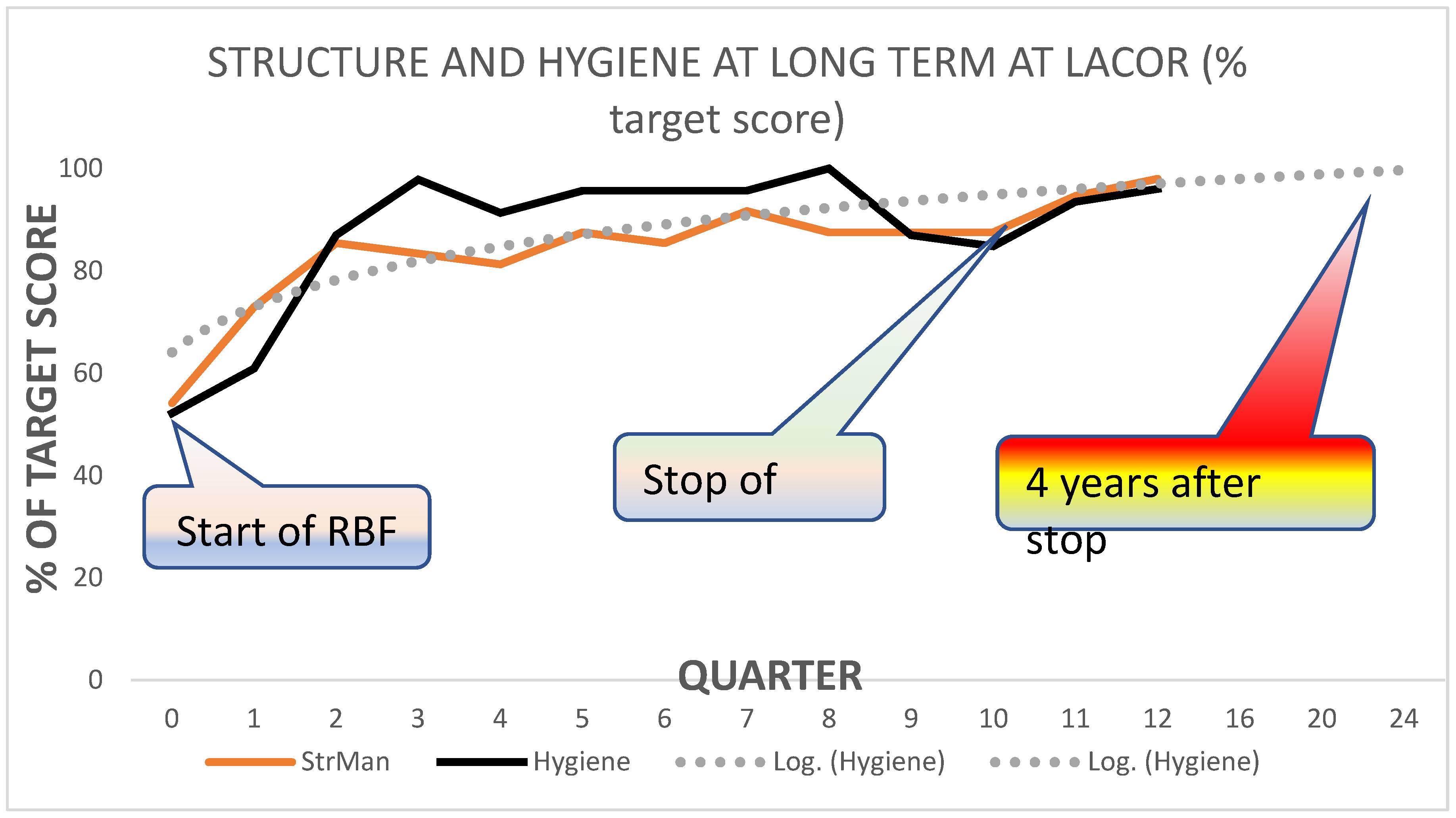

Figure 1 shows the percentage of the target score for the domain of Structure and Management of the ward, plus the actions to preserve hygiene and prevent infections at Lacor.

At Lacor, the project’s first year covers the gaps in the respective domains, and at the end of the first year (quarter 4), scores were quite close to the set target. After the project stopped (2020), there was no performance decay: at the point assessment of 2024, four years after the stop, the scores were very close to the target (see

Table 1).

The pattern is like the one observed in

Figure 1: During the first year, there was a significant performance improvement, which remained stable up to the end of the project (2020) and four years after the end. A special note addresses the training domain: during the second and third years, the occasional absence of senior supervisors and the uncontrolled rotation of students (especially medical) made this activity unstable. By 2024, training also appeared to be stabilized at a high level of performance.

Kalongo Hospital’s Ward. Like the section on Lacor Hospital, this part would analyze the same metrics and health outcomes for Kalongo Hospital’s pediatric ward. Comparing the results between the two hospitals could identify patterns or differences in the impact of RBF, highlighting factors that might influence the success of the financing model, such as hospital size, staffing levels, or community engagement.

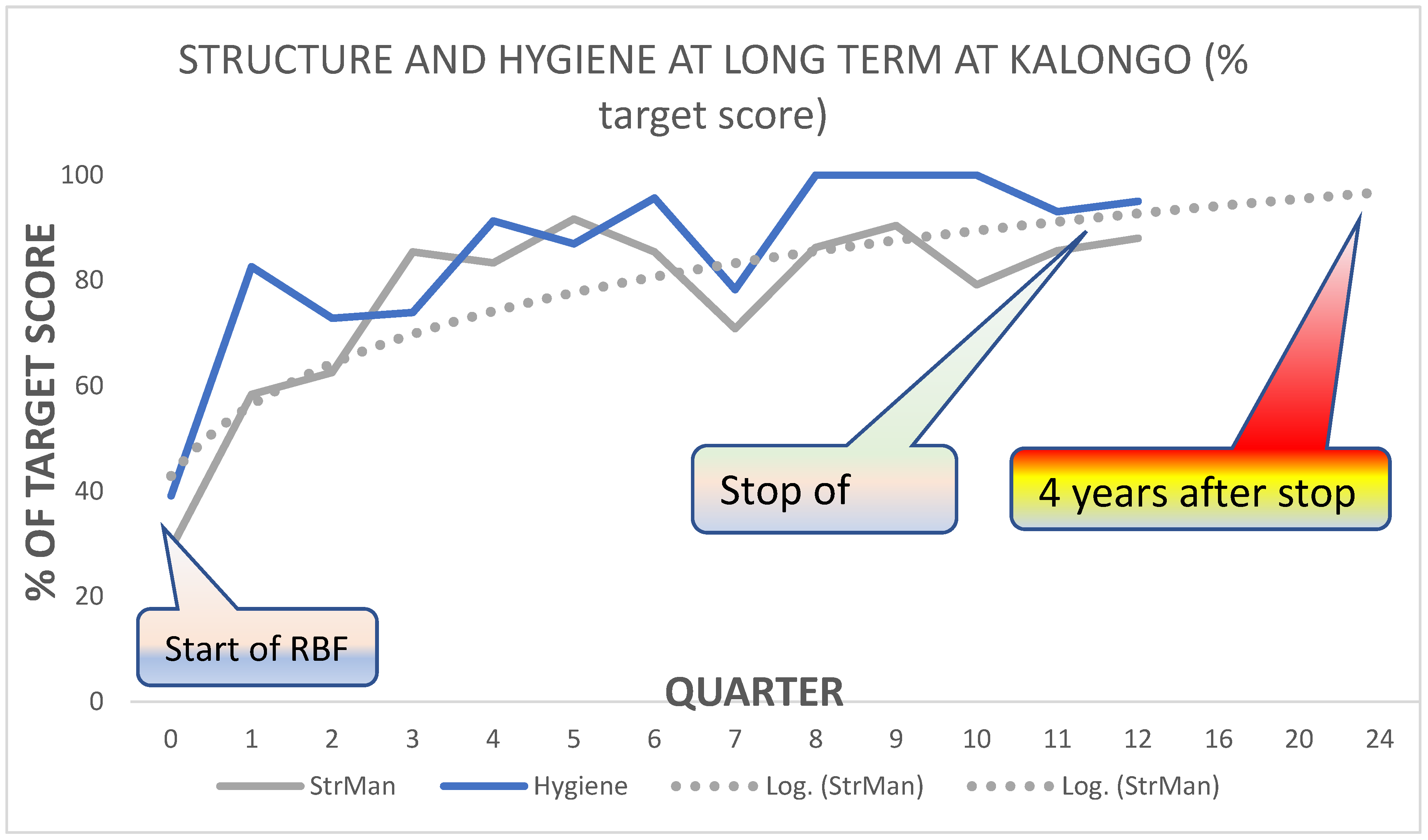

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the target score for the domains of structure and administration of the ward, plus the action to preserve hygiene and prevent infections at Kalongo.

At Kalongo, in the first year of the project, they examined the gaps in the respective domains, investing the resources gained by the RBF project in the amendment and maintenance of the basic structure of the children’s ward. In the second year (quarters 5-8), the improvement toward the target became sensible, reaching the third-year scores very close to the final objectives. After the stop of the project (2020), there was no decay of the performance: at the point assessment of 2024, four years after the stop, the scores were very close to the target (see

Table 1).

Figure 4 shows the performance (as a percentage of the target score) in the domains of patient Clinical Administration, Emergency readiness, and student training (nurses, medical doctors, and postgraduates) at Kalongo.

The pediatrician’s inconstant presence affected considerably the stability of clinical management and student training. Especially in the second year, supervision and guidance appeared to be unstable, significantly impacting performance. A significant improvement was observed in the third year, which was maintained for four years after the project stopped.

Lacor Hospital’s Clinical Management. This section will explore how RBF has affected clinical administration practices within Lacor Hospital. It might include analyses of changes in clinical guidelines adherence, decision-making processes, diagnostic use, and treatment protocols. The focus would be on understanding how financial incentives have improved the efficiency and quality of clinical administration in pediatric care.

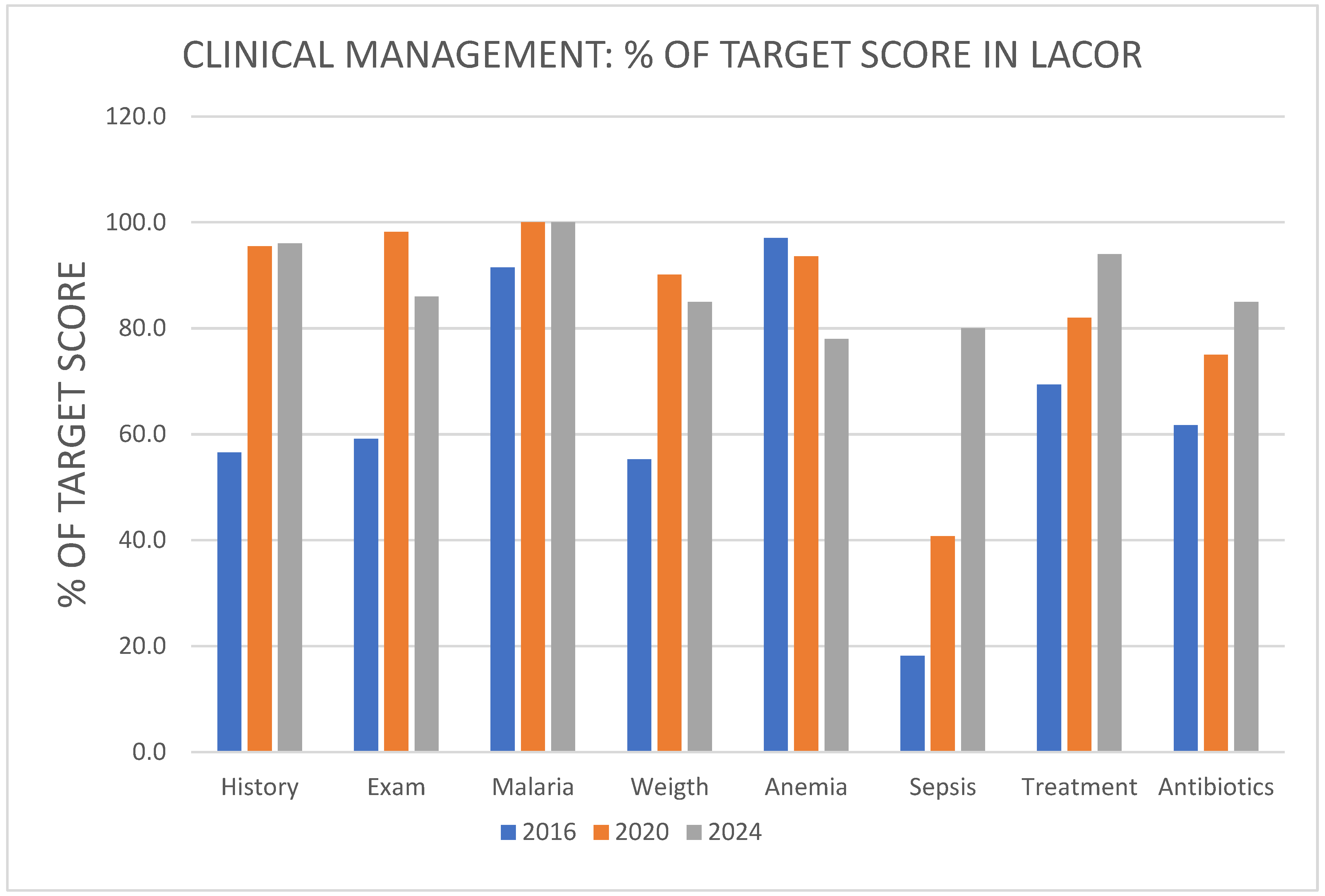

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the distribution of scores for each of the quality items for Clinical Management. The number of clinical records scrutinized was 162 for the year before RBF (2016), 111 for the year after RBF 2020, and 100 4 years after the stop (2024). For each score, we report the numbers and the % of the maximum score attained (i.e., the value of ‘3’) below. A Chi-Square compares the differences between 2016 and 2020, with first-degree error (p) below. How many folds changed from 2016 to 2020 is in the last line.

Figure 3 graphically shows the percentage maximum scores (=3) reached in 2016 (first bar), 2020 (second bar), and 2024 (third bar).

Since most of the observed analyses are correlated, a multivariate analysis was required to find which variable more efficiently differentiates the administration of patients between 2016 and 2020. A stepwise Canonical Discriminant analysis model selects the best variables to discriminate between the two years. Wilk’s lambda estimates the capacity of each variable to differentiate between the two years, where 1 = complete overlap and 0 = complete distance.

The symptoms based on clinical history, weight measurement, and clinical examination are the best discriminators: no other variable contributes significantly to the model. The acceptable correct prediction of 75% of cases in the year they belong provides a sufficiently robust estimate of the adequacy of the model. The practical indication suggests that these three items improve the service quality.

Unfortunately, the child’s weight is not reported in all cases since there is no space on the forms to report the weight centile, which is essential to estimate the child’s health; this is more often recorded in the Outpatient form, which most admitted children go through. Screening for malnutrition is occasional, and a specific query is absent on the clinical record. The main reason is that the assessment is done in the outpatient department but is only sometimes reported in the clinical record.

Similarly, the child’s immunization status is erratic since no specific query is marked on the forms.

The diagnosis of ‘Sepsis’ is often applied without the necessary investigation into the underlying infection. Introducing a readily available infection marker, such as the C-reactive protein (CRP), could significantly enhance the precision of diagnosis, thereby addressing the issue of overdiagnosis.

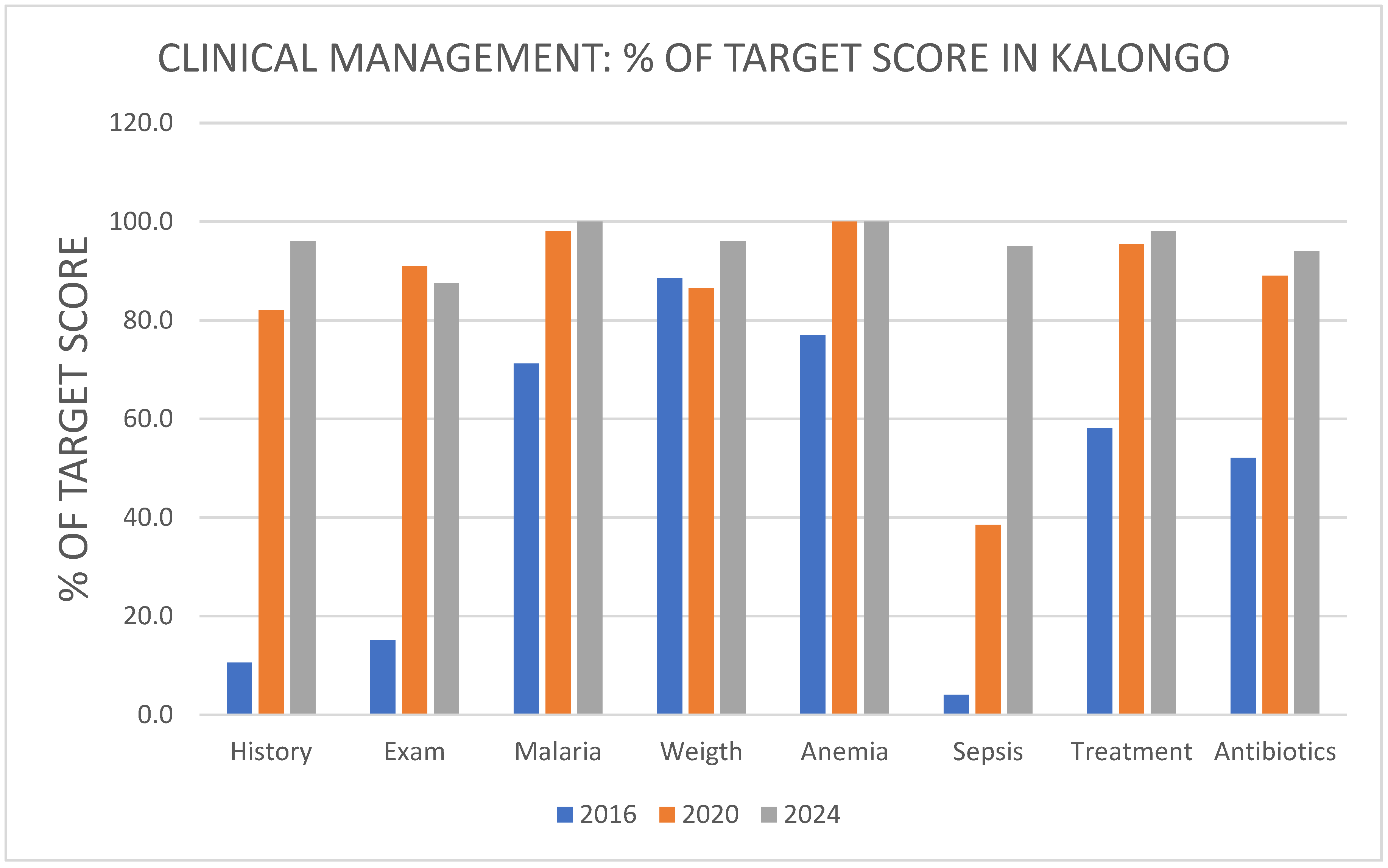

This section examines the same aspects of clinical management as in Lacor Hospital, providing a comprehensive view of the internal processes and practices at Kalongo Hospital. It also allows for a comparison of how the implementation of Results-Based Financing (RBF), a pivotal factor in driving change, has influenced clinical administration across different settings, thereby identifying best practices and areas for improvement.

It is sufficient to see the fold changes from 2016 to 2020 (% max score achieved in 2020 / % max score achieved in 2016) to estimate the dramatic changes observed at Kalongo (Tables 4 and 5).

The reporting of a detailed clinical history and the accurate examination of the child at Kalongo Hospital have shown remarkable improvements, increasing more than six times (= 600%!). This significant increase indicates the positive impact of the changes implemented. Similarly, the quality of care for sepsis has increased nine times. However, the appropriateness of the treatment and use of antibiotics have shown a smaller increase (1.6 - 1.7 times) due to the already high level of appropriateness in 2016. These changes reflect the hospital’s commitment to improving healthcare quality.

At Lacor, the improvements from 2016 to 2020 appeared less impressive because they started with decent care. However, the improvement was significant when considering clinical management and treating sick children.

The number of clinical records scrutinized was 218 for the time before RBF (2016), 111 three years later (2020), and 50 four years after the end of RBF (2024).

Table 3 shows the distribution of scores for the required quality items in 2016, 2020, and 2024: Clinical Management and Treatment. We report the numbers and the percentage of the total for each score. Chi-Square compares the differences between 2016 and 2020, with first-degree error (p) below. The last line shows how many folds the score changed from 2016 to 2020.

The Percentages of the maximum score achieved in 2016 (before), 2020 (at the end), and 2024 (four years after the end) are illustrated in

Figure 4, which shows the % maximum scores (=3) reached in the year 2016 (first bar), year 2020 (second bar) and year 2024 (third bar).

The symptoms based on clinical history, the appropriate treatment, and the clinical examination are the best discriminators: no other variable contributes significantly to the model. A stepwise Canonical Discriminant analysis model fits the data to select the best items that discriminate between the two years. Wilk’s lambda estimates the capacity of each variable to differentiate the two years, where 1 = complete overlap and 0 = complete distance. If we apply the discriminant score obtained by this analysis, we could unthinkingly predict each clinical record year for all the dates. The discriminant model adequately fits the observed data and allows the correct prediction of which year the record belongs in 90% of cases.

Quality Assessment Before and After the RBF Project. This section provides a comprehensive quality assessment of pediatric care in both hospitals, comparing the period before and after RBF implementation. This assessment could include patient satisfaction surveys, healthcare provider feedback, and adherence to national or international healthcare standards. Key performance indicators (KPIs) like healthcare-associated infections, vaccination rates, and the timeliness of care would be crucial metrics. This section could also explore the broader impact of RBF on hospital reputation, staff morale, and community trust.

Both hospitals, although with different starting points at time 0, showed a steep increase in the quality of assistance over the first and half year of intervention, reaching, by the 6th-8th quarter, a score close to 85-90% of the target score. By the end of RBF, a remarkable change in the structure, administration, and procedures occurred. The expected fall in performance after the program stopped did not happen. The high average quality score remained four years after the stop (2024). Not all domains reached the same results: training nurses and medical students was frequently erratic.

The management of sick children in the wards also improved significantly, comparing the charts of 2020 to those of 2016 before the project. The high quality of clinical activity persisted after the project’s end in 2024.

Scores for each domain over time, where the following: 0 = starting time 2018, 12 = end of the project Dec. 2020, 24 = four years after the end of project 2024

The score improvement for each domain resulted from the ratio between the observed score and the maximum score possible for the respective domain, expressed as a percentage of the target score (see scoring form in the Appendix). The Appendix also shows the distribution of the final diagnosis of children for the three years and the distribution of scores in the three observation periods for both hospitals.

Figure 5 shows the improvement of quality scores as a percentage of the starting scores (at time 0 start of the project) either of the scores reached at the end of the project (2020) as well of the scores four years after the end of the project (2024) for Lacor and Kalongo Children’s Wards. (‘20’ = Scores 2020-scores of 2018)*100/Scores of 2018), (‘24’ = Scores 2024-scores of 2018)*100/Scores of 2018).

Analysis of variance shows that Clinical Management was similar between the two hospitals. However, the difference across years of observation was marked and significant for both hospitals, as tested by the interaction Hosp x Year.

5. Discussion

The assessment framework in Uganda includes quarterly evaluations during implementation and follow-up surveys for lasting effects. Stakeholders receive valuable insights for decision-making. RBF models can enhance healthcare quality and outcomes but require addressing complexities for sustainability. Lacor and Kalongo hospitals showcase improvements in healthcare efficiency.

The study underscores the importance of evaluating and adapting RBF models to local contexts and health crises.

Detailed methodologies provide a solid framework for assessing impact over time. Lacor maintained high scores throughout the project, indicating stable, high-quality service. Kalongo required a longer period to establish a high level of service quality.

The framework for evaluating the RBF intervention in Uganda illustrates a holistic strategy for examining effectiveness both during the implementation phase and in the medium to long term after the intervention’s cessation. The initial assessment comprises quarterly evaluations of predetermined indicators to ensure efficacy during the active phase. In contrast, the medium to long-term assessment concentrates on the lasting effects of acquiring data from follow-up surveys, health outcomes, and economic ramifications.

The process of reporting and making recommendations highlights the production of comprehensive reports that encompass evaluations conducted in the short and long term, providing valuable insights for future interventions and policy adjustments based on the observed results. This robust evaluation model guarantees that stakeholders receive invaluable insights to support well-informed decision-making processes and the development of resource allocation strategies, thereby contributing to continuous enhancement and efficiency in future endeavors.

This analysis has shown that RBF can improve healthcare quality and outcomes while pointing out the complexities and challenges that ensure the success and sustainability of these models. RBF can enhance healthcare delivery in challenging environments through financial incentives aligned with desired health outcomes. Lacor and Kalongo hospitals have navigated challenges before and after the implementation of RBF, showcasing improvements in healthcare efficiency, quality, and patient outcomes, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The longitudinal study from 2018 to 2024 offers a valuable perspective on the long-term effects of RBF in pediatric care. It underlines the importance of continuously evaluating and adapting these models to local contexts and emerging health crises. Including detailed models and methodologies for evaluating the effectiveness of RBF interventions provides a solid framework for assessing their impact over time.

At Lacor, soon after the start of the project, the actions put in place to improve the structure, the administration, and the procedures at the Children’s ward allowed a steep rise in the achieved percentage of the maximum score. The starting status was already quite acceptable in 2018, so dramatic changes could not be expected. After the first year (Time 3 = 3rd quarter), minimal changes occurred for most items. The exception was training, where the rotation of medical students and the occasional presence of expatriates did not allow for an estimate of adequate performance in the training domain.

In 2018, Kalongo’s starting status suffered from several gaps, so the scores of each domain gradually improved over the first five quarters. The children’s ward was completely re-established in 2018-2019, allowing a significant score catch-up. The erratic presence of a pediatric specialist was related to the several gaps observed in the Clinical Procedures. Similarly to Lacor, even in Kalongo, the training domain suffered from the absence of supervision and the occasional presence of trainees.

The project indicators and verification assessment focused on qualitative and quantitative outputs of pediatric assistance involving the children’s ward and other hospital assistance necessary for diagnostic support to the children’s ward, such as radiology and laboratory.

The first project verification obtained a score of 62%. It highlighted several areas for improvement, including infrastructure, ward organization, waste administration, incomplete clinical forms, and fluid balance charts. During the first staff follow-up meeting to discuss the verification results, the quality team and children’s ward staff proactively identified a clear action plan, setting out individual responsibilities and deadlines for each point. Some of the non-compliances highlighted in the first verification regarded the purchase of equipment, which were addressed immediately by staff and management, such as setting up more hand-washing facilities and hypochlorite, the purchase of waste bins, and sterilization units. The non-compliances that regarded broader aspects, such as management of clinical forms and other factors related to clinical and nursing processes, required a lengthier process for improvement. However, at mid-project, such improvements have started to be visible in the quarterly verifications, and the results show an improvement in all areas subject to verification, with exceptions made for aspects that an RBF project cannot solve, such as the difficulty in retaining specialists in rural and underserved health facilities.

Throughout the project implementation, staff has been proactive in carrying out post-assessment follow-up meetings, clearly identifying responsibilities and deadlines. However, the documentation of follow-up meetings to record progress in addressing non-compliance needs to be stronger and should be a point of attention for future RBF projects.

The bonus produced by the verification scores has been used by the hospital both for assigning incentives to staff involved in the project activities and for supporting general hospital costs, with priority for expenses related to addressing any weaknesses identified during the verifications.

Through the RBF project in the Paediatric ward at Lacor Hospital, there was an improvement in several quality impacts:

Implement measures to promote and enhance patient safety, reduce harm, and prevent errors within the ward and its surroundings.

Evidence-based, consistent practices are utilized through enhanced adherence to guidelines and protocols to standardize care.

Regularly assess and monitor outcomes, processes, and infrastructures to identify areas for improvement.

Continuous medical and nursing education and training for staff to keep them updated on best practices and advancements in healthcare.

The motivation to carry on beyond the project concerns the involvement of department members in the routine assessments, identification of gaps, and designing solutions/recommendations. This involvement created a sense of local ownership of not just the processes but also the impacts. It has also been satisfying seeing this adapted in the other departments within the hospital.

Both hospitals showed steep increases in scores for all domains in the first year (quarters 0-3).

In Lacor, the levels achieved for most domains did not require greater improvement: the graphs show high scores’ persistence throughout the project. Lacor Hospital staff and management showed a remarkable capacity to maintain a stable and sustainable high-quality profile over time, suggesting that the RBF project became mostly ordinary routine practice rather than an occasional effort to improve the service.

The starting facilities in Kalongo Hospital suffered from several gaps; hence, a longer period, the first six quarters, was required to establish a high level of service quality.

The stability of performance post-project end indicates the sustained impact of RBF implementation. The fluctuating supervision and student rotation affected the training domain’s stability and performance. The improvements in clinical management and training underscore the lasting benefits of RBF. Kalongo Hospital’s substantial enhancements in clinical management highlight the effectiveness of RBF implementation.

6. Conclusions

The primary contribution of this research lies in the comprehensive assessment of RBF models within healthcare delivery, with a specific focus on pediatric assistance within resource-constrained regions such as Northern Uganda, as delineated in various empirical inquiries. These studies accentuate the favorable effects of RBF on healthcare quality and outcomes, demonstrating enhancements in service utilization, maternal and child health metrics, and institutional delivery rates.

By aligning financial incentives with precise health objectives, RBF amplifies service efficiency and effectiveness, tackling obstacles like limited resources and personnel shortages. The discoveries underscore the critical nature of meticulous monitoring and evaluation mechanisms in the formulation and execution of financing frameworks, underscoring the imperative to amalgamate all vital healthcare system elements for a holistic enhancement in service provision.

The research underscores the necessity for continuous assessment and adaptation of RBF models to ensure sustainability and optimal impact on healthcare delivery in resource-limited settings like Northern Uganda. The integration of robust data collection methods and stakeholder engagement is pivotal to the success of RBF initiatives, enabling a nuanced understanding of the contextual factors influencing program effectiveness and sustainability in pediatric healthcare assistance.

The practical application of RBF in pediatric healthcare assistance at Lacor and Kalongo Hospital, specifically in regions with limited resources, such as Northern Uganda, is firmly grounded and substantiated by many academic studies. These research papers underscore the beneficial effects of RBF on the quality of healthcare assistance and health outcomes, demonstrating improvements in various aspects, including service utilization rates, maternal and child health indicators, and rates of institutional deliveries.

By aligning financial incentives with health-related goals, RBF enhances the efficiency and efficacy of healthcare assistance, effectively tackling obstacles such as scarce resources and shortages of healthcare personnel. There is a crucial necessity for ongoing evaluation, adaptation, and incorporation of robust data collection techniques in RBF frameworks to ensure their sustainability and achieve maximum impact, as indicated in several scholarly works. The practical implications and hurdles associated with implementing RBF in providing pediatric care, particularly in regions with limited resources, are elucidated through real-world case studies, offering valuable insights into the model’s efficacy and underscoring the significance of resilience and innovation in healthcare service delivery.

RBF has positively impacted healthcare assistance in low- and middle-income countries, improving institutional delivery rates and the number of healthcare facility visits. However, the impact varies depending on the context.

The application of RBF in pediatric services, particularly in under-resourced areas such as Northern Uganda, presents a promising avenue for enhancing healthcare delivery. By design, RBF aligns financial incentives with desired health outcomes, directly correlating healthcare provider performance and compensation. This model encourages providers to improve service quality, efficiency, and effectiveness, focusing on achieving specific, measurable health outcomes for children.

Applying the theoretical concepts of RBF to empirical cases involving Lacor and Kalongo hospitals provides valuable insights into the practical implications and challenges of implementing RBF in pediatric assistance.

Before the introduction of RBF, both hospitals, like many healthcare institutions located in areas with limited resources, encountered obstacles, including restricted resource availability, inadequacies in staffing, and inconsistent levels of healthcare quality. With the introduction of RBF, these hospitals would have developed and agreed upon specific health outcomes, such as reductions in child mortality rates, improved vaccination coverage, or increased rates of timely antenatal care visits.

The global outbreak of COVID-19 brought forth unparalleled obstacles to healthcare systems on a worldwide scale. Within RBF, these healthcare facilities needed to modify their approaches and functions to uphold their healthcare service objectives amidst the pandemic. Such adaptations could have entailed reallocating resources, integrating telehealth innovations, or establishing fresh guidelines to handle COVID-19 instances while ensuring pediatric healthcare assistance remained uninterrupted. The critical need for healthcare organizations to swiftly adjust their operational frameworks to navigate the complexities introduced by the pandemic underscored the importance of resilience and innovation in the face of such unprecedented challenges.

The period from 2018 to 2024 offers a significant timeframe for evaluating the impact of RBF on pediatric services. This would involve analyzing health outcome data before and after RBF implementation, as well as during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Key factors for the evaluation would include changes in healthcare delivery efficiency, quality of care, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes among the pediatric population.

Lacor and Kalongo Hospital’s experiences would provide valuable lessons on the effectiveness of RBF in improving pediatric healthcare assistance, particularly in challenging and resource-limited settings. Identifying best practices, challenges, and strategies for overcoming obstacles would be crucial for refining RBF models and guiding future implementations.

In conclusion, the empirical application of RBF in pediatric services at Lacor and Kalongo Hospital offers a practical examination of how theoretical RBF models can be applied and adapted to real-world settings. It underscores the potential of RBF to drive improvements in healthcare quality and outcomes, particularly in under-resourced areas facing additional challenges such as those posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aligning financial incentives with health goals improves service efficiency and effectiveness. Continuous assessment ensures maximum impact on healthcare delivery in resource-limited settings. Involving stakeholders and collecting data provide insights into program effectiveness and sustainability. Real-world case studies demonstrate the efficacy of RBF in enhancing healthcare delivery in complex settings.

Contributions

*** See cover letter.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability

Data sharing does not apply to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank *** for their support in the design and on-field implementation. See cover letter.

References

- Ambrosoli and Lacor Foundations, 2024. Repository. RBF pediatrics Lacor and Kalongo Hospitals, URL https://data.mendeley.com/v1/datasets/publish–confirmation/tpbnxy54cw/1.

- Annan, J.; Blattman, C.; Mazurana, D.; Carlson, K. Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda. J. Confl. Resolut. 2011, 55, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.; Bertone, M.P.; Barthes, O. Exploring implementation practices in results-based financing: the case of the verification in Benin. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beane, C.R.; Hobbs, S.H.; Thirumurthy, H. Exploring the potential for using results-based financing to address non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Heal. 2013, 13, 92–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, S.; Muula, A.S.; Robyn, P.J.; Bärnighausen, T.; Sarker, M.; Mathanga, D.P.; Bossert, T.; De Allegri, M. Design of an impact evaluation using a mixed methods model – an explanatory assessment of the effects of results-based financing mechanisms on maternal healthcare services in Malawi. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 180–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, S.; Mazalale, J.; Wilhelm, D.; Nesbitt, R.C.; Lohela, T.J.; Chinkhumba, J.; Lohmann, J.; Muula, A.S.; De Allegri, M. Impact of results-based financing on effective obstetric care coverage: evidence from a quasi-experimental study in Malawi. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD), 2021. Tracking The Progress and Implications Of The Global Financing Facility (In This Case Results-Based Financing) In The Healthcare Sector In Uganda, July, URL https://www.csogffhub.org/wp–content/uploads/2021/12/GFF–RBF–Study_CEHURD_UDN_Wemos_2021.pdf.

- Falisse, J.-B.; Ndayishimiye, J.; Kamenyero, V.; Bossuyt, M. Performance-based financing in the context of selective free health-care: an evaluation of its effects on the use of primary health-care services in Burundi using routine data. Heal. Policy Plan. 2014, 30, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondazione Corti, Lacor Hospital, Fondazione Ambrosoli. 2021. Results Based Financing an engine of change for Paediatric services, URL https://fondazionecorti.it/wp–content/uploads/2014/07/RBF–study–2021.pdf.

- Friedman, J. , Qamruddin, J., Chansa, C., Das, A.K., 2016. Impact evaluation of Zambia’s health results–based financing pilot project. World Bank Group.

- Grittner, A.M. , 2013. Results–based Financing: Evidence from performance-based financing in the health sector. Discussion Paper No. 6/2013, URL https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/Results-based-financing.pdf.

- James, N.; Lawson, K.; Acharya, Y. Evidence on result-based financing in maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Glob. Heal. Res. Policy 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuunibe, N.; Lohmann, J.; Hillebrecht, M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Tougri, G.; De Allegri, M. What happens when performance-based financing meets free healthcare? Evidence from an interrupted time-series analysis. Heal. Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manongi, R.; Mushi, D.; Kessy, J.; Salome, S.; Njau, B. Does training on performance based financing make a difference in performance and quality of health care delivery? Health care provider’s perspective in Rungwe Tanzania. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 154–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathonnat, J. , Pelissier, A., 2017. How a Results-Based Financing approach can contribute to the Health Sustainable Development Goals-Policy-oriented lessons: What we know, what we need to know and don’t yet know. FERDI Working Paper No. P204, URL https://ferdi.fr/dl/df-DcyCwHKqtU36VFwax5RqyTV3/ferdi-p204-how-a-results-based-financing-approach-can-contribute-to-the.pdf.

- Visconti, R.M.; Larocca, A.; Marconi, M. Accessibility to First-Mile health services: A time-cost model for rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro-Visconti. R., 2024. Results-Based Financing in Healthcare: Evidence from Northern Uganda, URL https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377781738_Results–Based_Financing_in_Healthcare_Evidence_from_Northern_Uganda.

- Mushasha, R.; El Bcheraoui, C. Comparative effectiveness of financing models in development assistance for health and the role of results-based funding approaches: a scoping review. Glob. Heal. 2023, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkangu, M.; Little, J.; Omonaiye, O.; Pongou, R.; Deonandan, R.; Geneau, R.; Yaya, S. A systematic review of the effect of performance-based financing interventions on out-of-pocket expenses to improve access to, and the utilization of, maternal health services across health sectors in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Glob. Heal. 2023, 13, 04035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, A.D. , Fretheim, A., 2008. An overview of research on the effects of results–based financing. Report from Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services (NOKC) No. 16-2008, URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464844/.

- Soeters, R.; Peerenboom, P.B.; Mushagalusa, P.; Kimanuka, C. Performance-Based Financing Experiment Improved Health Care In The Democratic Republic Of Congo. Heal. Aff. 2011, 30, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Financial inclusion, education, and employment: empirical evidence from 101 countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M.; Spagnolo, J.; De Allegri, M.; Ridde, V. Does performance-based financing increase value for money in low- and middle- income countries? A systematic review. Heal. Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witter, S.; Bertone, M.P.; Namakula, J.; Chandiwana, P.; Chirwa, Y.; Ssennyonjo, A.; Ssengooba, F. (How) does RBF strengthen strategic purchasing of health care? Comparing the experience of Uganda, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob. Heal. Res. Policy 2019, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Shepard, D.S.; Rusatira, J.d.D.; Blaakman, A.P.; Nsitou, B.M. Evaluation of results-based financing in the Republic of the Congo: a comparison group pre–post study. Heal. Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).