Highlights:

The consequences of untreated hyperuricemia (HU) link high uric acid levels to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and stroke.

Metabolic syndrome is correlated with HU, as any disruption leading to a reduced number of caveolae on the cell surface can simultaneously manifest as metabolic syndrome and HU.

Patients with HU or gout may have a decreased risk of neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia) but an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease.

The integration of precision medicine principles, targeting individual genetic and metabolic profiles, holds promise for more effective and tailored interventions.

Emerging therapies, including microbiota-targeted interventions and anti-inflammatory agents, offer novel avenues for future research and therapeutic development.

Introduction

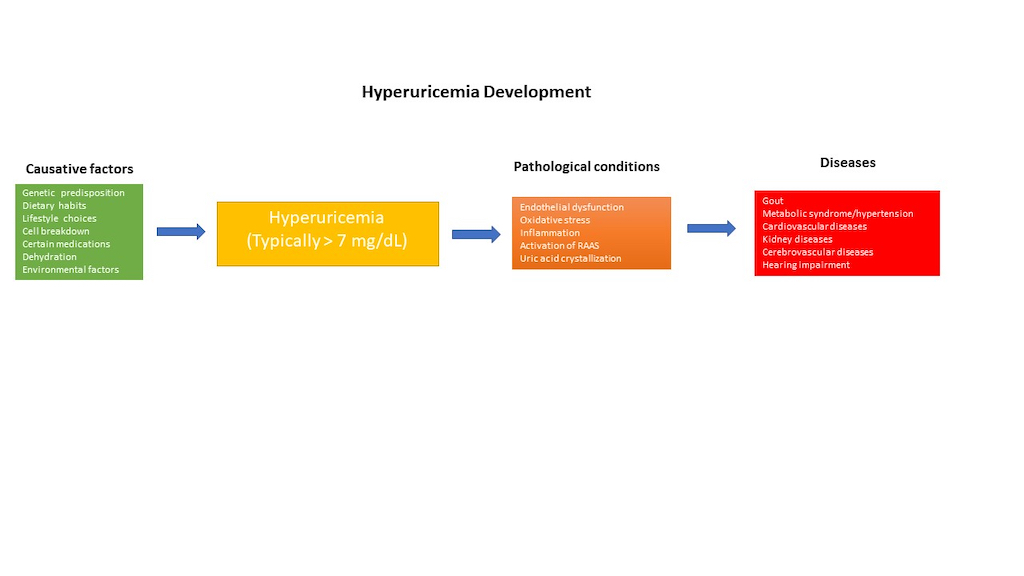

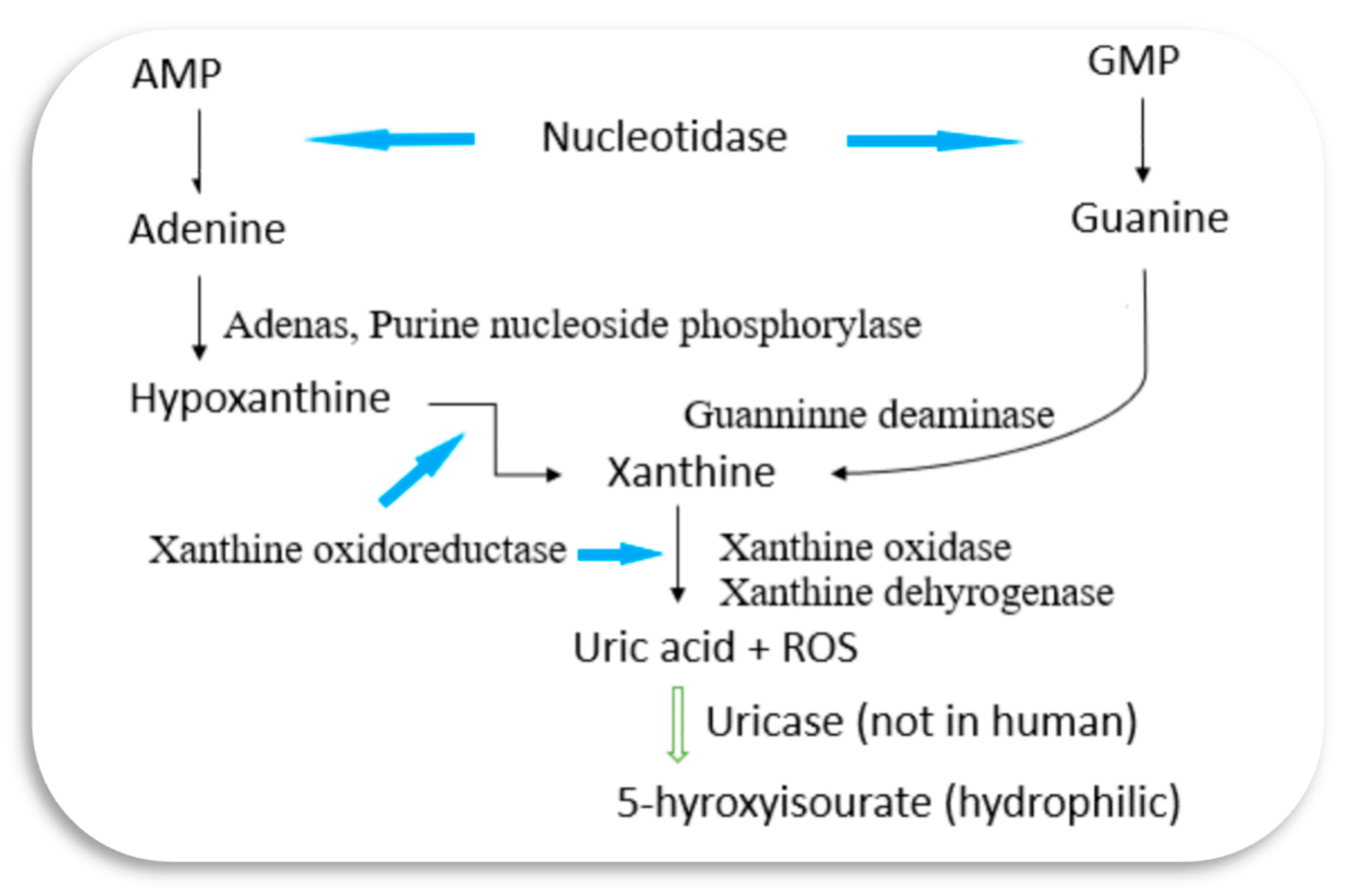

Hyperuricemia (HU), a metabolic disorder characterized by elevated levels of uric acid (UA) in the bloodstream, stands as a significant health concern globally. In general, hyperuricemia is diagnosed when UA levels rise above 420 µmol L−1 (7 mg/dL) for men and over 350 µmol L−1 (6 mg/dL) for women, typically exceeding 7.0 mg/dL. In many mammals, UA is further degraded to allantoin, a water-soluble compound, by the enzyme uricase. However, humans lack uricase, resulting in UA levels at the theoretical limit of solubility in the serum (6.8 mg/dL) [

1]. HU can be induced by consuming purine-rich foods, cell breakdown, genetic factors, impaired kidney function, obesity, certain medications, metabolic diseases, alcohol consumption, and dehydration. The etiologies of HU can be acute, such as acute renal failure, cell lysis syndromes, and rhabdomyolysis, or chronic, such as genetic or iatrogenic origins. This condition has garnered attention due to its association with a myriad of health complications, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), hypertension, gout, metabolic diseases and renal dysfunction [

2], as well as

hearing impairment [

3]. The pharmacological treatment of asymptomatic HU was not addressed in the American College of Rheumatology guidelines for managing gout [

4]

or the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology’s evidence-based recommendations for gout [

5]

. However, the guidelines from the Japanese Society of Hypertension and the Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism [

6]

recommend managing HU, although this management may often be insufficient. Additionally, in China, there is a positive attitude toward the treatment of HU [

7]. As our understanding of HU deepens, it becomes increasingly evident that its etiology is multifactorial, stemming from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, dietary habits, lifestyle choices, and environmental factors [

2,

8,

9].

Fundamentally, HU manifests when the balance between UA production and excretion is disrupted. The production of UA primarily occurs through the metabolism of purine nucleotides, with dietary purines contributing to a significant portion of this process [

8].

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified UA metabolism pathway, highlighting the key enzymes involved. Genetic factors play a crucial role in predisposing individuals to HU [

10]. Variations in genes encoding UA transporters, such as SLC2A9 and ABCG2, can influence UA levels by affecting renal reabsorption and secretion [

11]. Furthermore, polymorphisms in enzymes involved in purine metabolism, such as xanthine oxidase (XO) [

12], may contribute to increased UA production. Environment factors such as some heavy metals could interfere UA excretion by damaging renal tissue cells [

13].

The intricate relationship between genetic predisposition and environmental influences highlights the multifaceted character of HU.

Due to the current controversies and less-than-ideal treatment outcomes in the management of HU worldwide, the evolving discoveries have drawn attention to its role in various pathologies. Timely consolidation and integration of fundings will facilitate effective treatment for HU individuals and aid clinicians in providing better care. This review offers a contemporary analysis of the current state of understanding HU, its underlying causes, associated health risks, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and prospects for future research and management.

Association with Health Risks

The consequences of untreated HU extend beyond the biochemical abnormalities associated with elevated UA levels. CVDs represent one of the most concerning complications of HU, with numerous studies linking high UA levels to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, hypertension, metabolic syndrome (MS), and stroke [

14]. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system have been proposed as potential mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of HU [

15]. HU can exacerbate endothelial cell pyroptosis within aortic atherosclerotic plaques, advancing the progression of atherosclerosis [

16]. Furthermore, elevated levels of soluble UA can initiate the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [

17], leading to endothelial cell pyroptosis, a process modulated by cellular ROS levels. Gout, a painful arthritic condition caused by the deposition of urate crystals in joints, is one of the most widely recognized consequences of elevated UA levels. Although not all HU patients will experience gout flares, HU is a primary risk factor for gout, and both conditions lead to systemic metabolic alterations underlying metabolic disorders [

18]. The association between HU and various health risks has been a subject of extensive research. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for implementing targeted interventions aimed at reducing cardiovascular and other risks in individuals with HU.

Gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis, is perhaps the most recognizable consequence of HU. The deposition of urate crystals in the joints triggers acute episodes of intense pain, swelling, and inflammation characteristic of gouty arthritis [

2]. Recurrent gout attacks not only cause significant morbidity but can also lead to joint damage and deformity if left untreated. Moreover, chronic HU has been implicated in the development of tophi, urate crystal deposits that can form in soft tissues surrounding the joints, further complicating the management of gout.

The association of HU with CVD has been debated over the last a few decades. The majority of recent studies show a favourable correlation between HU and CVDs despite the cut off of the damaging levels of UA have not been established as yet [

14]. However, whether treating HU could reduce cardiovascular events is still not concluded [

19].

HU has also been associated with increased risk of developing hypertension and a chronic phase of microvascular injury is known to occur after prolonged periods of HU [

20]

.

MS is correlated with HU, with approximately one-third of patients with MS also presenting HU [

21]. HU becomes an emerging potential biomarker of MS and its constellations of obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension and dyslipidemia. As the key molecules of those conditions, including insulin receptor, GLUT4, CAT1,eNOS, CD36 plus UA transporters, are collocated on cell surface domain of caveolae fulfilling their functions [

2,

22], any disruption causing a reduced number of caveolae presence on cell surface can concurrently manifest MS and HU.

HU is also an independent risk factor for renal insufficiency [

23] and for acute kidney injury in septic patients [

24]. Renal dysfunction is both a cause and consequence of HU, creating a vicious cycle that exacerbates the condition's severity [

25]. Chronic kidney disease impairs UA excretion, leading to further elevations in serum UA levels. Conversely, HU has been implicated in the progression of renal disease through mechanisms such as tubulointerstitial inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction.The weight of the evidence suggests asymptomatic HU is likely injurious, but it may primarily relate to subgroups of renal conditions, those who have systemic crystal deposits, those with frequent urinary crystalluria or kidney stones, and those with high intracellular UA levels [

26]. Managing HU in patients with renal impairment poses unique challenges, emphasizing the importance of early detection and intervention to mitigate renal complications.

Although low levels of plasma UA have a potential detrimental role on cognitive function [

27], patients with HU or gout might have a decreased risk of neurodegenerative diseases (such as

Alzheimer’s disease and dementia) and increased risk of cerebrovascular disease [

28]. Whether the neuroprotective or anti-oxidant roles of UA playing an important role in the pathogenesis is still warranted to confirm.

Recent advances in genomics have shed light on the genetic factors contributing to HU [

10]. Genetic variants associated with enzymes involved in purine metabolism and UA excretion have been identified. Understanding these genetic markers allows for a more personalized approach to treatment. Precision medicine, which involves tailoring therapeutic interventions based on an individual's genetic makeup, has the potential to revolutionize HU management. By identifying genetic predispositions, clinicians can develop targeted strategies that address the root causes of HU, optimizing treatment outcomes.

However, over the last decade, genome-wide association studies have pinpointed numerous genetic variants, predominantly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), linked to HU. These SNPs offer a continuous measure of genetic susceptibility, aiding in the assessment of HU development risk. Genetic variants of inflammasome genes and of genes encoding their molecular partners may influence HU and gout susceptibility. Notably, a newly identified UA binding protein, the neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein (NAIP), is proposed to play a role in the paradox of asymptomatic HU [

29]

. NAIP is a potential molecule of UA recognition protein and sensor for NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes. UA may serve as the endogenous ligand involved in activation of inflammatory and immunological pathways, playing a role in both pro-inflammatory and neuroprotective environments [

29]

.

HU represents a multifaceted metabolic disorder with far-reaching implications for health and well-being. Its intricate pathogenesis involves a combination of genetic predisposition, dietary factors, lifestyle choices, and environmental influences. The recognition of HU as a risk factor for CVDs, gout, and renal dysfunction underscores the importance of proactive management strategies aimed at reducing UA levels and mitigating associated complications. By addressing the underlying causes and implementing targeted interventions, healthcare providers can improve outcomes and enhance the quality of life for individuals living with HU.

Current Diagnostic Approaches

Timely and accurate diagnosis is crucial for effectively managing HU. Serum UA measurement remains the primary diagnostic method, with elevated levels indicating HU. While some metabolic profile variations between HU and gout have been discovered [

9,

30], the search for biomarkers of HU is not prioritized due to its straightforward definition. Reprogramming

E. coli has emerged as a potential synthetic biology therapy for monitoring serum UA levels [

31]. However, other contributing factors or coexisting conditions may also need to be assessed; the increase in serum UA levels with immunosuppression could contribute to the coexistence of HU or gout in patients with systemic inflammatory disorders receiving effective therapies [

32]. Technological advancements have improved diagnostic accuracy, with imaging techniques like ultrasound and dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) offering non-invasive visualization of urate crystal deposits, aiding in both diagnosis and understanding their severity [

33]. UA clearance, a calculated ratio based on blood and urine UA levels, may offer new insights into managing HU [

34]. Identifying novel biomarkers associated with HU and its complications could lead to promising treatment strategies. Advanced omics technologies enable a comprehensive examination of molecular pathways, facilitating the identification of intervention targets. Integrating these biomarkers into clinical practice could revolutionize early detection and risk assessment, allowing for proactive and personalized management approaches.

Treatment Strategies

Pharmacological interventions are integral in managing HU, especially when lifestyle modifications are insufficient. However, it's essential to carefully consider individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and potential drug interactions when selecting medications. XO inhibitors like allopurinol and febuxostat are recommended as first-line treatments for HU, with uricosuric agents serving as second-line options. Combination therapy with both XO inhibitors and uricosuric agents is advised when monotherapy proves ineffective [

35]. Despite the availability of various oral urate-lowering medications, treatment failure and refractory disease remain significant challenges. Newly developed drugs such as lesinurad, when used in conjunction with XO inhibitors, offer promising outcomes for patients with gout who haven't achieved target serum UA levels with XO inhibitors alone [

36]. Interleukin-1 inhibitors have emerged as valuable additions to the treatment arsenal, particularly for refractory gout cases or patients with comorbidities [

35]. These drugs effectively lower serum UA levels and prevent gout recurrence. Uricosuric agents like dotinurad enhance UA excretion by targeting specific enzymes involved in purine metabolism [

37]. Anti-inflammatory agents are often co-administered with UA-lowering drugs. Nevertheless, ongoing research is focused on developing new uricosuric agents and investigating anti-inflammatory agents to improve HU management [

2].

While numerous UA lowering agents demonstrate efficacy, their application is often limited by adverse effects. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and edible plants have emerged as alternative treatments for

HU [

38]. Long-term clinical practice with TCM formulas has shown relative safety for short-term HU treatment [

39]. TCM and natural products offer similar UA-lowering efficacy as Western medicine but with fewer adverse effects [

40]. Various Chinese herbs and formulas targeting heat clearance and dampness drainage have proven effective and safe for HU treatment. Modern pharmacological studies in animal models have confirmed the protective effects of TCM herbs on liver XOR activity and renal urate transporters, similar to commercial drugs [

40]. Concomitant use of TCM for HU is gaining traction due to its ability to impact various signaling pathways and UA transporters, thus promoting balanced inflammatory interactions and UA excretion [

41]. Natural products containing flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and other compounds show promise as URAT1 or XO inhibitors [

42,

43]. Phytochemicals derived from natural sources possess the beneficial property of downregulating UA levels and dissolving monosodium urate

crystals [

44]. Specific TCM components like

Dendrobium officinale exhibit anti-HU effects by regulating urate transport-related transporters and inhibiting XO

activity [

45]. Additionally, dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diets play a role in reducing serum UA concentrations and preventing HU by influencing gut microbiota and purine metabolism directly or indirectly [

46].

Recent investigations have illuminated the potential engagement of gut microbiota in UA metabolism, unveiling fresh pathways for innovative interventions. Preliminary studies in animal models have yielded promising outcomes, indicating that interventions directed at the gut microbiota might have the capacity to modify UA metabolism. Probiotics have proven effective in alleviating HU by absorbing purines, restoring gut microbiota balance, and inhibiting XO

activity [

46].Treatment with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum improves gut microbiota dysbiosis in hyperuricemic mice, reducing inflammation and HU-associated flora while promoting the production of short-chain fatty acids [

47]. Conversely, the genus

Collinsella may be the gut microbiota most directly linked to elevated blood uric acid levels [

48]. Additionally, the depletion of microbiota in uricase-deficient mice has resulted in significant HU, while the administration of anaerobe-targeted antibiotics increases the risk of gout in humans [

49]. Pharmaceutically restoring the probiotic uricolytic pathway represents a promising approach to efficiently converting urate to (S)-allantoin without intermediate metabolite accumulation for HU treatment [

50]. Integration of FtsP-uricase into the genetically isolated region of probiotic

Escherichia coli Nissle maintains probiotic traits and overall gene expression for HU treatment [

51].

Streptococcus thermophilus IDCC 2201 effectively lowers UA levels by degrading purine nucleosides, restoring intestinal flora, and promoting short-chain fatty acid production, making it a potential adjuvant treatment for HU [

52]. Additionally, enhancing enzymatic capacity for urate degradation via a genome-based insulated system may offer an optimal strategy for lowering UA levels. Treatment options for HU encompass XO inhibitors, uricosuric medications, and recombinant uricases [

53]

.

Prioritizing serum UA optimization is crucial, with lifestyle modifications and novel therapeutic approaches offering hope. Combining XO inhibitors and uricosuric agents may enhance treatment efficacy, while personalized medicine and innovative interventions show promise for future management. Implementing lifestyle modifications could prove effective in reducing serum UA levels, however, dietary changes alone may not adequately optimize serum UA levels, necessitating specific treatments [

35]. The prospect of personalized medicine, tailoring treatment plans based on individual genetic and metabolic profiles [

54], holds promise for more effective and targeted management in the future.

Role of Lifestyle Factors

Various lifestyle factors, including sleep, exercise, dietary supplements, eating habits, and other behaviors, along with genetic predispositions, contribute to either UA overproduction or underexcretion, predisposing individuals to HU. Unfavorable habits such as excessive consumption of meat broth, seafood, fructose, and alcohol, as well as irregular or insufficient sleep [

55] and prolonged sedentary behavior [

56], may contribute to the onset of HU. Managing UA levels emphasizes the concept of "food as medicine," with dietary adjustments effectively controlling UA levels. Alkalization of urine by eating nutritionally well-designed food could be effective for removing UA from the body [

57,

58]. It's crucial to identify foods suitable for individuals with high UA levels and provide tailored meal plans and eating schedules. Despite purine-rich foods potentially raising UA levels [

8], especially in those with impaired UA clearance, excessive alcohol and fructose-rich beverages have also been linked to HU [

10]. The associated factors such as

ethanol catabolism, lactic acid inhibition of renal urate excretion, acute liver damage, and fructose consumption affect the production of UA metabolic enzymes and UA transporters [

59]

or intensifying adenosine triphosphate (ATP) degradation [

60]

, contributing to elevated serum UA levels following alcohol or fructose intake. Encouraging moderation in alcohol consumption and ensuring adequate hydration are essential aspects of HU management.

Regular physical activity aids in managing HU [

61] by promoting weight loss or maintenance, crucial for reducing UA levels associated with excess body weight. Exercise improves insulin sensitivity, regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, thus potentially lowering UA levels. Enhanced blood circulation from exercise stimulates kidney function, promoting UA excretion through urine, aiding in its elimination. Exercise increases blood shear stress which can regulate UA transporters dynamically sited on cell surface domain of caveolae [

2,

62]. Additionally, exercise exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, reducing inflammation linked to HU and gout [

18]. These combined benefits of exercise contribute to lower UA levels and decreased risk of gout attacks. However, it's worth noting that intense exercise may potentially reduce UA solubility by elevating lactate concentration [

63], induce dehydrated HU [

64], and increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis through the release of UA from skeletal muscle [

65]. Therefore, consulting a healthcare professional before starting an exercise regimen is advised, especially for those with medical conditions.

Adopting a healthy lifestyle may partially mitigate the genetic predisposition to HU, with dietary factors playing a smaller but still significant role in serum urate variance, influencing the overall population risk [

66]. Lifestyle modifications, including reducing purine-rich food intake, maintaining a healthy weight, and engaging in regular physical activity, are crucial for preventing or managing HU [

67]. Additionally, promoting good sleep hygiene [

68], regular physical activity, and outdoor recreational activities [

61] can help individuals maintain normal UA levels.

Prospective Directions

Recent research has expanded the therapeutic landscape for HU, with a focus on novel drug targets and innovative approaches. Enzymes involved in purine metabolism, such as adenosine deaminase [

69], are under investigation as potential targets for drug development. Modulating these enzymes could offer a more targeted and efficient way to regulate UA levels. Another promising avenue is the exploration of anti-inflammatory agents for managing HU-related complications [

70]. Inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of gout and other associated conditions. Investigating the use of anti-inflammatory medications, including colchicine and interleukin-1 inhibitors, may provide additional benefits in reducing the frequency and severity of gout attacks [

71]. Recent studies have highlighted the intricate interplay between the gut microbiota and UA metabolism. The gut microbiome influences the breakdown of purines and the production of short-chain fatty acids, which can impact UA levels. Modulating the gut microbiota through probiotics or fecal microbiota transplantation represents a novel approach to managing HU [

47]. However, further research is needed to establish the safety and efficacy of microbiota-targeted interventions in humans. Understanding the complex relationship between the gut microbiota and HU opens avenues for innovative and personalized therapeutic strategies.

The era of precision medicine also extends to lifestyle recommendations. Understanding an individual's genetic predisposition to HU allows for personalized dietary advice, considering variations in purine metabolism. Tailoring lifestyle interventions based on genetic and metabolic profiles enhances their effectiveness and promotes long-term adherence. Genetic factors, lifestyle choices, and environmental influences contribute to the heterogeneity of HU presentation. By incorporating individual patient data, including genetic information, into treatment decisions, clinicians can optimize therapeutic outcomes. Genetic markers associated with HU susceptibility and drug response can guide treatment selection. For example, certain genetic variants may influence the efficacy and safety of specific pharmacological agents [

72]. Integrating genetic testing into the diagnostic process allows for a more nuanced understanding of the patient's risk profile and potential treatment responses.

Despite significant progress in understanding HU, several challenges and unanswered questions persist. The optimal duration of pharmacological interventions, potential long-term side effects, and the impact of HU management on cardiovascular outcomes require further investigation. Additionally, the complex interplay between genetics, environmental factors, and lifestyle choices necessitates a holistic and personalized approach to patient care. Future research should focus on identifying additional genetic markers, refining diagnostic criteria, and elucidating the molecular pathways underlying HU-related complications. Large-scale prospective studies are essential to establish the long-term safety and efficacy of emerging therapies. Collaborative efforts between clinicians, researchers, and pharmaceutical industries will be crucial in advancing our understanding and improving patient outcomes.

Conclusion

HU, with its intricate interplay of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors, presents a multifaceted challenge in contemporary medicine. This comprehensive review has provided an in-depth analysis of the current state of knowledge on HU, covering its definition, causes, associated health risks, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and future prospects. Advancements in genomics, diagnostic imaging, and therapeutic options have significantly expanded our understanding and capabilities in managing HU. The integration of precision medicine principles, targeting individual genetic and metabolic profiles, holds promise for more effective and tailored interventions. Emerging therapies, including microbiota-targeted interventions and anti-inflammatory agents, offer novel avenues for future research and therapeutic development. As we navigate the complexities of HU, a holistic approach that considers the diverse factors influencing its development and progression is paramount. The collaborative efforts of researchers, clinicians, and patients will drive further innovations, ultimately enhancing our ability to prevent, diagnose, and manage HU, improving the overall quality of patient care.

Abbreviation

| ATP |

adenosine triphosphate |

| CAT1 |

cationic amino acid transporter-1 |

| CD36 |

glycoprotein IV |

| CVD |

cardiovascular disease |

| DECT |

dual-energy computed tomography |

| eNOS |

endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| GLUT4 |

glucose transporter type 4 |

| HU |

hyperuricemia |

| MS |

metabolic syndrome |

| NAIP |

neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein |

| NLRP3 |

NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| NLRC4 |

NLR family caspase activation and recruitment domain-containing 4 |

| ROS |

reactive oxidative species |

| SNP |

single nucleotide polymorphism |

| TMC |

traditional Chinese medicine |

| UA |

uric acid |

| URAT1 |

urate transporter 1 |

| XO |

xanthine oxidase |

| XOR |

xanthine oxidoreductase |

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Y. Saito, A. Tanaka, K. Node, and Y. Kobayashi, “Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review,” Journal of Cardiology, vol. 78, no. 1. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. zheng Zhang, “Uric acid en route to gout,” in Advances in Clinical Chemistry, 2023.

- H. Jeong, Y. S. Chang, and C. H. Jeon, “Association between Hyperuricemia and Hearing Impairment: Results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,” Med., vol. 59, no. 7. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. D. FitzGerald et al., “2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout,” Arthritis Care Res., vol. 72, no. 6. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Richette et al., “2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout,” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 76, no. 1. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Yamanaka, “Essence of the revised guideline for the management of Hyperuricemia and gout,” Japan Medical Association Journal, vol. 55, no. 4. 2012.

- Y. Li, Z. Lin, Y. Wang, H. Wu, and B. Zhang, “Are hyperuricemia and gout different diseases? Comment on the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hyperuricemia and gout with the healthcare professional perspectives in China,” International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 26, no. 9. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Lubawy and D. Formanowicz, “High-Fructose Diet–Induced Hyperuricemia Accompanying Metabolic Syndrome–Mechanisms and Dietary Therapy Proposals,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 20, no. 4. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu and C. You, “The biomarkers discovery of hyperuricemia and gout: proteomics and metabolomics,” PeerJ, vol. 11. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang et al., “Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Hyperuricemia: The TCLSIH Cohort Study,” Am. J. Med., vol. 136, no. 5. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Xin, J. Zhou, Z. Wu, X. Zhang, and J. Gao, “Advances in Urate Excretion and Urate Transporters in Hyperuricemia,” Chinese Gen. Pract., vol. 26, no. 15. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Lu et al., “Fuling-Zexie formula attenuates hyperuricemia-induced nephropathy and inhibits JAK2/STAT3 signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in mice,” J. Ethnopharmacol., vol. 319. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Lu et al., “Association and Interaction between Heavy Metals and Hyperuricemia in a Taiwanese Population,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 10. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Chrysant, “Association of hyperuricemia with cardiovascular diseases: current evidence,” Hospital Practice, vol. 51, no. 2. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Jia, A. R. Aroor, C. Jia, and J. R. Sowers, “Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease, vol. 1865, no. 7. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. He et al., “Hyperuricemia promotes the progression of atherosclerosis by activating endothelial cell pyroptosis via the ROS/NLRP3 pathway,” J. Cell. Physiol., vol. 238, no. 8. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Q. Liu, X. Meng, L. Zhao, X. Zheng, and W. Feng, “Catalpol ameliorates fructose-induced renal inflammation by inhibiting TLR4/MyD88 signaling and uric acid reabsorption,” Eur. J. Pharmacol., vol. 967. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Z. Zhang, “Why does hyperuricemia not necessarily induce gout?,” Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 2. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Akashi et al., “Hyperuricemia predicts increased cardiovascular events in patients with chronic coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention: A nationwide cohort study from Japan,” Front. Cardiovasc. Med., vol. 9. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Stewart, V. Langlois, and D. Noone, “Hyperuricemia and hypertension: Links and risks,” Integrated Blood Pressure Control, vol. 12. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sadia Nizamani, Khadim Hussain, Ramesh Kumar, Saajan Sawai, and Doulat Singh, “Hyperuricemia in metabolic syndrome.,” Prof. Med. J., vol. 30, no. 05. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, “An association of metabolic syndrome constellation with cellular membrane caveolae,” Pathobiol. Aging Age-related Dis., vol. 4, no. 1. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Shi and Q. Ma, “Correlation between hyperuricemia and renal function in elderly who received health examination,” Chinese J. Heal. Manag., vol. 17, no. 7. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. X. Jiang et al., “Association between hyperuricemia and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with sepsis,” BMC Nephrol., vol. 24, no. 1. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Bakhshaei et al., “Allopurinol and renal impairment; as review on current findings,” J. Ren. Endocrinol., vol. 9. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Johnson, L. G. Sanchez Lozada, M. A. Lanaspa, F. Piani, and C. Borghi, “Uric Acid and Chronic Kidney Disease: Still More to Do,” Kidney International Reports, vol. 8, no. 2. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang et al., “Association of plasma uric acid levels with cognitive function among non-hyperuricemia adults: A prospective study,” Clin. Nutr., vol. 41, no. 3. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Latourte, J. Dumurgier, C. Paquet, and P. Richette, “Hyperuricemia, Gout, and the Brain—an Update,” Current Rheumatology Reports, vol. 23, no. 12. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. D. de Lima et al., “Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of the Innate Immune Response to Gout,” Immunological Investigations, vol. 52, no. 3. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Shen et al., “Serum Metabolomics Identifies Dysregulated Pathways and Potential Metabolic Biomarkers for Hyperuricemia and Gout,” Arthritis Rheumatol., vol. 73, no. 9. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Gencer et al., “Engineering Escherichia coli for diagnosis and management of hyperuricemia,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 11. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. E. W. Pietsch, P. Kubler, and P. C. Robinson, “The effect of reducing systemic inflammation on serum urate,” Rheumatology (United Kingdom), vol. 59, no. 10. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Zhang et al., “Burden and distribution of monosodium urate deposition in patients with hyperuricemia and gout: a cross-sectional Chinese population-based dual-energy CT study,” Quant. Imaging Med. Surg., vol. 13, no. 7. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Zheng et al., “A wide-range UAC sensor for the classification of hyperuricemia in spot samples,” Talanta, vol. 266. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. F. G. Cicero, F. Fogacci, M. Kuwabara, and C. Borghi, “Therapeutic strategies for the treatment of chronic hyperuricemia: An evidence-based update,” Medicina (Lithuania), vol. 57, no. 1. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Deeks, “Lesinurad: A Review in Hyperuricaemia of Gout,” Drugs and Aging, vol. 34, no. 5. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Yanai, H. Adachi, M. Hakoshima, S. Iida, and H. Katsuyama, “A Possible Therapeutic Application of the Selective Inhibitor of Urate Transporter 1, Dotinurad, for Metabolic Syndrome, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Cardiovascular Disease,” Cells, vol. 13, no. 5. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Cheng-yuan and D. Jian-gang, “Research progress on the prevention and treatment of hyperuricemia by medicinal and edible plants and its bioactive components,” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 10. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Leong, H. H. Chen, S. Y. Gau, C. Y. Chen, Y. C. Su, and J. C. C. Wei, “Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients with hyperuricemia: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded clinical trial,” Int. J. Rheum. Dis., vol. 27, no. 1. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, B. Wang, L. Ma, and P. Fu, “Traditional Chinese herbs and natural products in hyperuricemia-induced chronic kidney disease,” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 13. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Fu, M. Zhang, X. Ci, and T. Cui, “Research progress of therapeutic agents for gout and hyperuricemia,” Drug Eval. Res., vol. 44, no. 8. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yuan, Y. Cheng, R. Sheng, Y. Yuan, and M. Hu, “A Brief Review of Natural Products with Urate Transporter 1 Inhibition for the Treatment of Hyperuricemia,” Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou and G. Huang, “The Inhibitory Activity of Natural Products to Xanthine Oxidase,” Chemistry and Biodiversity, vol. 20, no. 5. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Y. Alhamoud, S. Lv, F. Feng, and J. Wang, “Beneficial properties and mechanisms of natural phytochemicals to combat and prevent hyperuricemia and gout,” Trends in Food Science and Technology, vol. 138. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Z. Li et al., “Effects of a Macroporous Resin Extract of Dendrobium officinale Leaves in Rats with Hyperuricemia Induced by Anthropomorphic Unhealthy Lifestyle,” Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med., vol. 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, C. Ni, J. Zhao, G. Wang, and W. Chen, “Probiotics, bioactive compounds and dietary patterns for the effective management of hyperuricemia: a review,” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 64, no. 7. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zou et al., “The anti-hyperuricemic and gut microbiota regulatory effects of a novel purine assimilatory strain, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum X7022,” Eur. J. Nutr., vol. 63, no. 3. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Miyajima et al., “Prediction and causal inference of hyperuricemia using gut microbiota,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 9901, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “A widely distributed gene cluster compensates for uricase loss in hominids,” Cell, vol. 186, no. 16. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Ronda et al., “A Trivalent Enzymatic System for Uricolytic Therapy of HPRT Deficiency and Lesch-Nyhan Disease,” Pharm. Res., vol. 34, no. 7. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. He et al., “Rational design of a genome-based insulated system in Escherichia coli facilitates heterologous uricase expression for hyperuricemia treatment,” Bioeng. Transl. Med., vol. 8, no. 2. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim, J. S. Moon, J. E. Kim, Y. J. Jang, H. S. Choi, and I. Oh, “Evaluation of purine-nucleoside degrading ability and in vivo uric acid lowering of Streptococcus thermophilus IDCC 2201, a novel antiuricemia strain,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 2 February. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Piani, D. Agnoletti, and C. Borghi, “Advances in pharmacotherapies for hyperuricemia,” Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, vol. 24, no. 6. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ma et al., “Obesity-related genetic variants and hyperuricemia risk in Chinese men,” Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)., vol. 10, no. APR. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Son et al., “Association between weekend catch-up sleep and hyperuricemia with insufficient sleep in postmenopausal Korean women: A nationwide cross-sectional study,” Menopause, vol. 30, no. 6. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Hong et al., “Association of Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity With Hyperuricemia and Sex Differences: Results From the China Multi-Ethnic Cohort Study,” J. Rheumatol., vol. 49, no. 5. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Kanbara, Y. Miura, H. Hyogo, K. Chayama, and I. Seyama, “Effect of urine pH changed by dietary intervention on uric acid clearance mechanism of pH-dependent excretion of urinary uric acid,” Nutr. J., vol. 11, no. 1. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, S. Pang, J. Guo, J. Yang, and R. Ou, “Assessment of the efficacy of alkaline water in conjunction with conventional medication for the treatment of chronic gouty arthritis: A randomized controlled study,” Medicine (Baltimore)., vol. 103, no. 14, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/fulltext/2024/04050/assessment_of_the_efficacy_of_alkaline_water_in.69.aspx.

- X. Ding et al., “Interaction of Harmful Alcohol Use and Tea Consumption on Hyperuricemia Among Han Residents Aged 30–79 in Chongqing, China,” Int. J. Gen. Med., vol. 16. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Puddu, G. M. Puddu, E. Cravero, L. Vizioli, and A. Muscari, “The relationships among hyperuricemia, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications,” Journal of Cardiology, vol. 59, no. 3. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hou et al., “The Effect of Low and Moderate Exercise on Hyperuricemia: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Study,” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Damaske et al., “Peripheral hemorheological and vascular correlates of coronary blood flow,” in Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation, 2011, vol. 49, no. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Y. He et al., “Interaction between Hyperuricemia and Admission Lactate Increases the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction,” CardioRenal Med., vol. 12, no. 5–6. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Roncal-Jimenez et al., “Heat Stress Nephropathy from Exercise-Induced Uric Acid Crystalluria: A Perspective on Mesoamerican Nephropathy,” Am. J. Kidney Dis., vol. 67, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdelnabi, N. Leelaviwat, E. D. Liao, S. Motamedi, W. Pangkanon, and K. Nugent, “Daptomycin-induced rhabdomyolysis complicated with acute gouty arthritis,” American Journal of the Medical Sciences, vol. 365, no. 5. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Healthy lifestyle counteracts the risk effect of genetic factors on incident gout: a large population-based longitudinal study,” BMC Med., vol. 20, no. 1. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Yokose, N. McCormick, and H. K. Choi, “Dietary and Lifestyle-Centered Approach in Gout Care and Prevention,” Current Rheumatology Reports, vol. 23, no. 7. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. C. Wiener and A. Shankar, “Association between serum uric acid levels and sleep variables: Results from the national health and nutrition survey 20052008,” International Journal of Inflammation, vol. 2012. 2012. [CrossRef]

- X. Peng, K. Liu, X. Hu, D. Gong, and G. Zhang, “Hesperitin-Copper(II) Complex Regulates the NLRP3 Pathway and Attenuates Hyperuricemia and Renal Inflammation,” Foods, vol. 13, no. 4. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Xu et al., “Eupatilin inhibits xanthine oxidase in vitro and attenuates hyperuricemia and renal injury in vivo,” Food Chem. Toxicol., vol. 183. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Tai, P. C. Robinson, and N. Dalbeth, “Gout and the COVID-19 pandemic,” Current opinion in rheumatology, vol. 34, no. 2. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ohashi, H. Ooyama, H. Makinoshima, T. Takada, H. Matsuo, and K. Ichida, “Plasma and Urinary Metabolomic Analysis of Gout and Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia and Profiling of Potential Biomarkers: A Pilot Study,” Biomedicines, vol. 12, no. 2. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).