1. Introduction

Clinical evidence has shown that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective in treating symptoms of depression and anxiety [

1]. CBT has expanded beyond depression and anxiety to include a wide range of psychiatric disorders [

2]. Schizophrenia is no exception; since the 1990s, large-scale randomized control trials (RCTs) have been conducted mainly in the U.K.

One in every 100 people develops schizophrenia [

3,

4]. Schizophrenia is described as a disorder of the form and content of perception and thought (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults, 2014), and is associated with significant social or occupational dysfunction [

5] in some patients. In contrast, early intervention, appropriate pharmacotherapy, and psychosocial support have been reported to lead to recovery and remission [

6].

Conversely, cognitive behavioral therapy of psychosis (CBTp) for schizophrenia has been widely used as a therapeutic intervention since the 1990s, especially in the U.K., and many textbooks have been published on this [

7,

8,

9]. CBTp is used in 58% and 91.3% of the medical institutions in the U.S. and U.K., respectively [

10]. Guidelines from the NICE [

11] in the U.K. and American Psychiatric Association [

12] in the U.S. have been published. A meta-analysis of 33 RCTs (n=1,940) on CBTp reported an effect size of 0.35–0.44 [

13].

Although the recommended standard duration of CBTp is approximately 16 sessions or more over 4-6 months, some evidence has been reported for short-term CBTp, consisting of approximately 6-10 sessions over less than 4 months, suggesting that short-term CBTp may have some benefit in treating symptoms of schizophrenia [

14,

15]. One report found that six brief CBTp sessions conducted by community psychiatric nurses visiting patients in their homes effectively improved depression and illness [

16]. Others have reported that six brief CBTp sessions in patients’ homes are effective for patients with low delusional beliefs [

17].

Supporters visiting patients in their homes and living environments to provide support and intervention as community life support for people with mental disorders is said to improve their quality of life (QOL) [

18]. In contrast, patients with schizophrenia tend to have latent anxiety, depressive symptoms, and low self-esteem due to self-stigma and other factors [

19]. These negative and depressive symptoms are also said to reduce their QOL [

20]. In Japan, the use of CBTp in psychiatric home nursing is uncommon, and there are no RCTs to date. Therefore, we hypothesized that nurses, public health nurses, and occupational therapists involved in psychiatric home nursing could contribute to reducing depression and anxiety in the community life of patients with schizophrenia by providing simple CBTp utilizing a workbook, in addition to their usual home visit support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

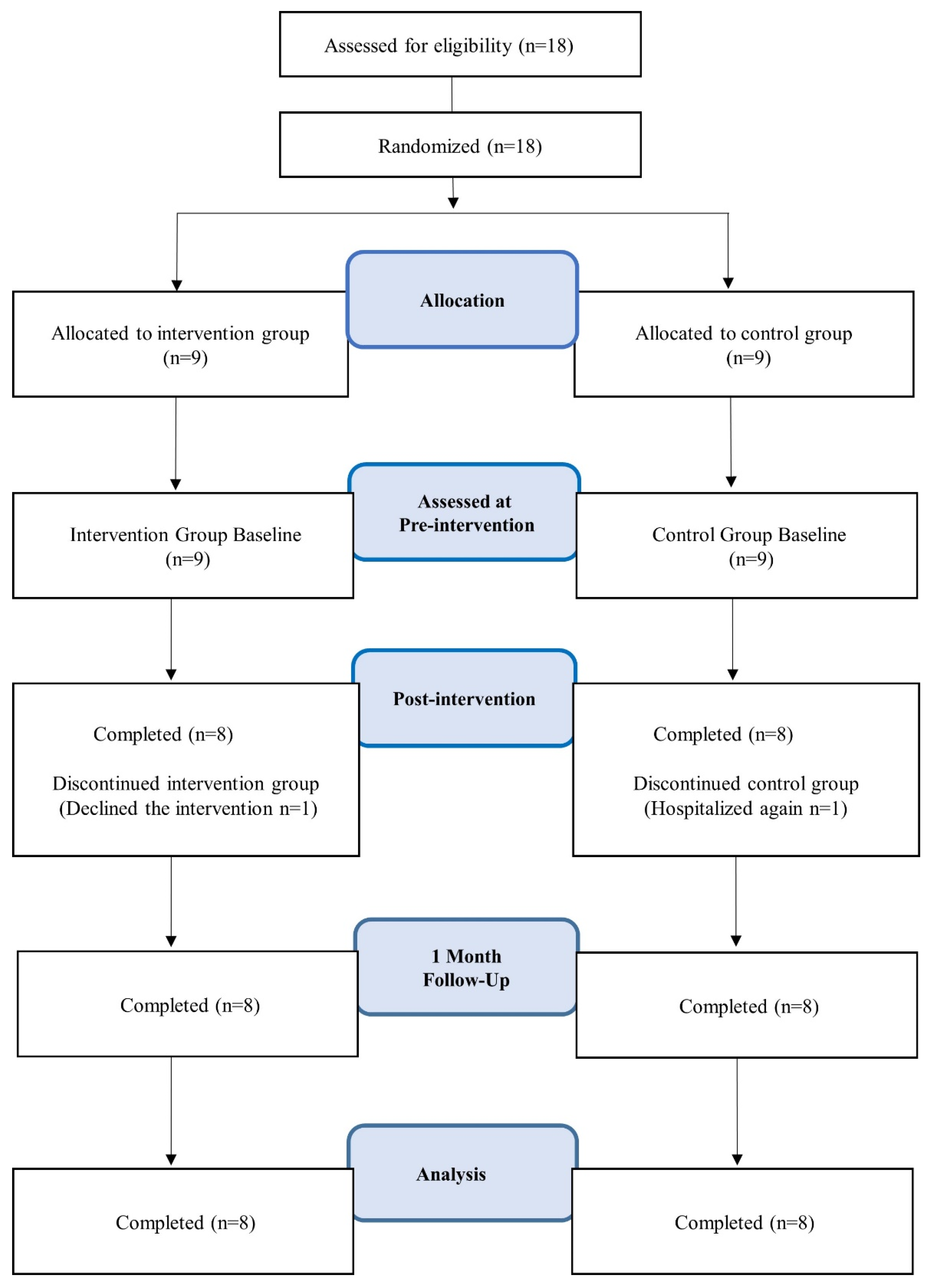

A nurse or occupational therapist recruited patients from among the assigned home nursing users via posters. We randomly assigned those who agreed to participate in two groups using the envelope method and made parallel-group comparisons (

Figure 1). We designated the group that received only usual home nursing care as the usual care (TAU) group, and the group that received usual home nursing care in addition to the CBTp intervention, as the CBTp+TAU group. For the intervention group, we conducted CBTp using manual materials during weekly home nursing visits. To compare the groups, we used a scale at each time point: pre-test, a week after the 8-week CBTp intervention period (post-test), and a month after the 13-week follow-up test (FU-test). We used the pre-test and FU test as the baseline and endpoint, respectively, and changes in the baseline and FU test were used as the primary and secondary endpoints.

2.2. Sample Size

A total of 24 patients (12 each in the TAU group and 12 in the TAU + CBTp groups) were initially selected as the target sample size as per a previous study [

21] which suggested that effect size estimation was possible even with 12 cases in each group in a pilot study.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were patients diagnosed with schizophrenia as an underlying medical condition, by their primary care physicians. They were enrolled at a home healthcare nursing station, a cooperating facility for the study, and after receiving a full explanation of their participation in the study, they fully understood and gave their free and voluntary written consent.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: four consecutive cancellations after the start of the intervention; withdrawal of consent or request to participate in the study; hospitalization during the study period due to worsening psychiatric symptoms; a serious or progressive physical illness; clear feelings of hopelessness; an agitated psychomotor state; a history of dependence on or abuse of drugs or alcohol within the past year; inability to give written consent of their own free will with full understanding despite receiving sufficient explanation of their participation in the study; or if the principal investigator determined that they were not appropriate for the study.

2.4. Intervention

As a psychosocial intervention to improve depression and anxiety, we used “Do-it-yourself cognitive-behavioral therapy” [

22] as a workbook to be used in sessions when conducting CBTp. The contents of the sessions were as follows: (1) Scoring emotions, (2) Self-affirmation, (3) Degree of confidence, (4) Looking for other thoughts, (5) Recording thought changes, (6) Noticing patterns of attention, (7) Noticing a counterexample, and (8) Activating actions. There were a total of eight sessions, each lasting approximately 40 min, conducted in the patients’ homes through visits at all times by in-charge nurses and occupational therapists who were skilled psychiatrists with more than 10 years of experience in clinical psychiatry. They additionally received approximately 10 hours of pre-session training from the study administrator (the author) and supervision after each session.

2.5. Outcome Measures

Information on age, gender, number of hospitalizations, age at onset, presence of a cohabitant, and amount of antipsychotic medication being taken were collected from medical records at baseline. The patients were evaluated at pre-test (baseline), post-test, and FU tests (endpoints) for the primary and secondary outcomes.

2.5.1. Primary Outcome

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Japanese version) was used as the primary endpoint; the K6 self-administered questionnaire screens for anxiety and depressive symptoms [

23]. The Japanese version is a self-administered rating scale created by Furukawa et al. that has been examined for reliability and validity [

24]. The questionnaire is very simple, consisting of only six questions, and is not burdensome for the examinee. The K6 has been found to be useful in serious illnesses such as schizophrenia because of its simplicity [

25]. To our knowledge, there is no literature on the use of the K6 as a primary endpoint in schizophrenia intervention studies; however, it has been developed for community mental health research that appropriately reflects distress and psychological anxiety and is useful for monitoring mental health status [

26], and has shown versatility in monitoring depression and anxiety among community residents [

27]. In addition, patients with schizophrenia have some cognitive impairment [

28], and the K6 is considered suitable for participants to work with as a method of assessing anxiety and depression in patients with schizophrenia supported by psychiatric home care because of its six questions and the plain and easy to understand wording of the questions.

2.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

We used the following secondary outcomes.

2.5.2.1. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II)

Depression severity was assessed using the Japanese version [

29] of the BDI-II [

30], a self-administered questionnaire that evaluates depression severity over the past two weeks. It comprises 21 questions in total, with a score of 13 or less indicating “very mild depression,” 14 or more “mild depression,” 20 or more “moderate depression,” and 29 or more “severe depression.” The maximum possible score is 63.

2.5.2.2. Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale-Japanese Version (JSQLS)

The JSQLS was created as a Japanese version [

31] and its reliability and validity have been examined. The original version, the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS) [

32] is a QOL assessment scale for patients with schizophrenia. In this study, the JSQLS was used to evaluate participants’ QOL. It consists of a total of 30 questions, with sub-items in the three domains of “motivation and vitality,” “symptoms and side effects,” and “psychosocial relationships,” each of which, can be compared on a 100-point scale. The total score is 120 points on a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “always,” with higher scores denoting poorer QOL.

2.5.2.3. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale-Japanese Version (RSES-J)

Self-esteem was measured using the RSES-J [

33], which was developed as a Japanese version of the original RSES [

34], a 4-item self-administered questionnaire with each question scored on a scale of 1 to 4. The higher the total score, the higher the self-esteem. The total score ranges from 10 to 40 points.

2.5.2.4. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

The GAF, which is used to assess both the severity of psychiatric symptoms and the level of functioning, is a rating of overall functioning and is quantified on a 100-point scale. Its reliability and validity have been examined [

35]. A home health nurse and occupational therapist observed the participants and scored their assessments.

2.6. Data Analysis

For the CBTp and TAU groups, patient background attributes were compared using an unpaired t-test and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The baseline values (pre-test) for each rating scale were compared between the two groups using an unpaired t-test.

For outcomes, an unpaired t-test was performed to determine the amount of change from baseline. In addition, analysis of covariance was performed for the amount of change, with the CBTp and TAU groups as fixed factors and adjusted for baseline values and age as covariates. The effect sizes (Hedge’s g) of the two groups were also determined. Absolute values of: 0.2 to less than 0.5, 0.5 to less than 0.8, and 0.8 or greater indicate small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively [

36].

As a sensitivity analysis, a repeated-measures mixed-effects model was used to examine the differences between the CBTp and TAU groups in terms of their rating scale scores at each time point (pre-test, post-test, and FU-test), the interaction between the groups and time points (pre-test, post-test, and FU-test), and group and time points as fixed effects. The p-values were set at 0.05, two-tailed on both sides. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17.

2.7. Research Ethics

This study was approved in 2014 by the Ethics Review Committees of Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine and Teikyo Heisei University (Approval Nos. 926 and 26-080, respectively). Written and oral explanations were provided to the collaborating institutions and study participants, and their written consent was obtained, stating that they could withdraw their participation from the study at any point in time and that there would be no disadvantages resulting from withdrawal.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic Information

This study was conducted between November 2014 and November 2016 with 18 participants. As one participant from the intervention group withdrew due to withdrawal of her consent, and one participant from the control group was hospitalized due to deterioration of his condition, there were finally eight participants each in both groups, that is a total of 16 participants (mean age 47.94 years, standard deviation ±13.17), were included in the analysis as a per protocol set. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of gender, age, age at schizophrenia onset, number of previous hospitalizations, duration of most recent community living (months), or amount of antipsychotic medication (chlorpromazine equivalent) taken at study entry (

Table 1). In addition, a comparison of the main and secondary items at baseline (pretest) using a t-test showed no significant differences between the two groups.

3.2. Primary Outcome

For the change from baseline on the primary endpoint of K6, the intervention and control groups scored -2.00 and 2.75, respectively, and the difference between the groups was 4.75 (confidence interval (Cl)=-10.21 to 0.71, p=0.08) on a t-test, indicating a trend toward improvement in anxiety and depression in the intervention group, but the difference was not significant (

Table 2). Furthermore, the amount of change was subjected to analysis of covariance with the intervention and control groups as fixed factors and adjusted for baseline values and age as covariates. Hence, similar to a t-test, no analysis of covariance was necessary. The effect size (Hedge’s g) of K6 at baseline at the endpoint was -0.95 (CI -1.98 to 0.08), with a large effect size.

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

As for changes in other endpoints, BDI-II showed a difference between groups of 8.0 (CI=-17.0 to 1.00, p=0.075), indicating a trend toward improvement in the CBTp+TAU group, but the difference was not significant; JSQLS showed a difference between groups of 14.75 (CI=-25.97 to 3.525, p=0.014), indicating a significant improvement in QOL in the CBTp+TAU group; and -0.87 (CI=-4.85 to 3.10) in RESE-J, as the TAU group showed more improvement than the CBTp + TAU group. The change in GAF was 8.38 (CI=-3.61 to 20.36), which was not significant. For the above two-group comparisons regarding the amount of change, not only t-tests but also analysis of covariance with the intervention group as a fixed factor and baseline values and age as covariates were performed. However, no covariance was necessary, and the results were similar to those of the t-tests. The effect sizes (Hedge’s g) for each endpoint at baseline were -0.95 (CI=-1.98 to 0.08) for BDI-II, and -1.33 (CI= -2.42 to -0.25) for JSQLS; hence the JSQLS showed a large effect.

To examine the differences between the two groups in the means of the scores of the primary and secondary measures at each time point, analyses were conducted using a mixed-effects model with repeated measures for the CBTp and TAU groups and time points (pre-test, post-test, and FU-test), and group and time point interactions as fixed effects, but there were no significant differences between the two groups.

4. Discussion

This pilot RCT explored whether depression and anxiety could be reduced by psychiatric home nursing providers offering brief cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp) at home using a workbook. Our study confirmed that the intervention has the potential to alleviate anxiety and depression compared to standard psychiatric home nursing care alone. Specific findings are discussed below.

4.1. Depression and Anxiety

A relatively large effect size was observed for change in K6, although there was no significant difference in the amount of change from baseline to endpoint, one month after completion of the 8-session CBT intervention between the intervention and the control group. The higher effect size in this study compared to the overall effect size previously reported in a meta-analysis [

13] suggests that CBT may also reduce depression and anxiety in patients with schizophrenia. However, the findings should be interpreted with caution since the sample size was limited because it was a pilot study.

4.2. Quality of Life

The effect sizes were large in the JSQLS sub-domains “Symptoms and Side Effects” and “Psychosocial Relationships,” which indicate that CBTp improved patients’ self-perception regarding symptoms and their moods and feelings. Patients may experience various events and stressors in their community life. Improving coping skills for depression and anxiety improves the QOL as it leads to self-help [

37], and CBTp interventions may contribute to improved coping skills [

38].

4.3. Possibility of Relapse Prevention

Regarding the change from baseline in the primary and secondary endpoints at the end point (FU-test time point), there was a trend toward improvement in the CBTp group; however, in the TAU group, the K6, BDI-II, JSQLS, and GAF endpoints worsened after 13 weeks of non-intervention, and the trend toward worsening of K6, BDI-II, and JSQLS in patients in the TAU group may also be related to the ease of relapse of schizophrenia symptoms [

39]. However, the intervention group did not experience exacerbations and showed a trend toward improvement, suggesting that the CBTp intervention may have contributed to the prevention of exacerbations. Relapse and rehospitalization are characteristic features of schizophrenia, and prevention of relapse is a major objective of community life support. There have been prior reports on stepped care models for depression and anxiety disorders [

11]. A similar model has been identified to be necessary for schizophrenia [

40,

41]. Providing simple CBTp with a limited number of sessions in home nursing support for schizophrenia, as in this study, may lead to stress management for early depression and anxiety and prevent the exacerbation or relapse of symptoms [

42].

4.4. Implementation Costs

The CBTp may face practitioner shortage [

43]; hence, the use of workbook materials may allow CBTp to be practiced with less cost and effort, thereby improving patient access to CBTp. Such CBTp has been reported to have the advantage of being inexpensive, flexible, and easy to use [

44]. They may be appropriate for those with access difficulties and can be relatively easily incorporated into the tiered care model of CBTp. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy provided by healthcare professionals other than psychologists with some training was considered to contribute to stepped care.

4.5. Limitations and Future Challenges

This study has some limitations. First, the envelope method was used to randomly assign patients to two groups for simplicity of conduction in a home nursing setting; however, the endpoints caused differences between the groups at baseline. In the subsequent RCTs, stratified allocation with respect to baseline severity in both groups may be performed using a computer. Second, objective assessments such as the GAF should be blinded to the assessors to eliminate bias. Third, although the present study used the K6 self-administered scale for depression and anxiety, the use of structured interview rating scales should be considered.

5. Conclusion

In this pilot RCT, it was observed that the addition of CBTp by psychiatric home nursing care supporters such as nurses and occupational therapists may improve anxiety and depression in patients with schizophrenia using psychiatric home nursing services, compared to usual psychiatric home nursing services alone.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used conceptualization, M.K. and E.S.; software, E.S.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing; supervision, E.S.; project administration, M.K.; Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number 926) and Teikyo Heisei University (approval number 26-080) in 2014, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the visiting nurses and occupational therapists of Yen Group Inc. for their understanding and advice, and the patients who participated in this study. We also thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rachman, S. The evolution of behaviour therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther 2015, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, N.; Pilecki, B.; McKay, D. Contemporary cognitive behavior therapy: A review of theory, history, and evidence. Psychodyn Psychiatry 2015, 43, 423–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueser, K.T.; McGurk, S.R. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2004, 363, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J.; McGrath, J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLOS Med 2005, 2, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.; Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J. Schizophrenia: A concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev 2008, 30, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAqeel, B.; Margolese, H.C. Remission in schizophrenia: Critical and systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2012, 20, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, E.; Fowler, D.; Garety, P. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychosis: Theory and Practice; Wiley: Chichester; East Susex. ISBN: 978-0-471-95618-1, 1995. 224 pages.

- Birchwood, M.J.; Chadwick, P.; Trower, P. Cognitive Therapy for Delusions, Voices and Paranoia; Wiley: Chichester. ISBN: 978-0-471-96173-4, 1996; p. 232pages.

- Kingdon, D.G.; Turkington, D. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy of Schizophrenia. First edition; Psychology Press: London. ISBN 9781003210528, 1994. 240 pages.

- Kuller, A.M.; Ott, B.D.; Goisman, R.M.; Wainwright, L.D.; Rabin, R.J. Cognitive behavioral therapy and schizophrenia: A survey of clinical practices and views on efficacy in the United States and United Kingdom. Community Ment Health J 2010, 46, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental H. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Schizophrenia: Core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in primary and secondary care (update). Copyright ©2009; British Psychological Society: Leicester UK; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2009.

- American Psychiatric A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth edition edition; American Psychiatric Association; 2013 2013/05/22/.

- Wykes, T.; Steel, C.; Everitt, B.; Tarrier, N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull 2008, 34, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, S.; Garety, P.; Peters, E.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Onwumere, J.; Harris, V.; Brabban, A.; Johns, L. Opportunities and challenges in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies for people with Severe Mental Illness (IAPT-SMI): Evaluating the first operational year of the South London and Maudsley (SLaM) demonstration site for psychosis. Behav Res Ther 2015, 64, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, F.; Farooq, S.; Kingdon, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy (brief vs standard duration) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2014, 40, 958–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkington, D.; Kingdon, D.; Turner, T. Insight into Schizophrenia Research Group. Effectiveness of a brief cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2002, 180, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabban, A.; Tai, S.; Turkington, D. Predictors of outcome in brief cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.B.; Dickerson, F.; Bellack, A.S.; Bennett, M.; Dickinson, D.; Goldberg, R.W.; Lehman, A.; Tenhula, W.N.; Calmes, C.; Pasillas, R.M.; et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull 2010, 36, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, P.B.; Williams, C.L.; Corteling, N.; Filia, S.L.; Brewer, K.; Adams, A.; de Castella, A.R.; Rolfe, T.; Davey, P.; Kulkarni, J. Subject and observer-rated quality of life in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001, 103, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, J.D.; Weiss, K.A.; Lim, R.; Pratt, S.; Smith, T.E. Quality of life in schizophrenia: Contributions of anxiety and depression. Schizophr Res 2001, 51, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julious, S.A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, E. Do-It-Yourself Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Seiwa Shoten Publishers Inc.: Tokyo, 2010 (in Japanese). 197 pages 9784791107476.

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H.; et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, J.A.; Lurigio, A.J. Screening for serious mental illness in populations with co-occurring substance use disorders: Performance of the K6 scale. J Subst Abuse Treat 2006, 31, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J. Evaluating psychological distress data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, A.S.; Paradies, Y.; Kelaher, M. Mental health impacts of racial discrimination in Australian culturally and linguistically diverse communities: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, S.C.; Murray, A. Assessing cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2016, 77, Suppl–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ball, R.; Ranieri, W. Comparison of beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. In J Pers Assess 1996, 67, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Takahashi, H.; Kawai, M.; Nagaya, T.; Tokudome, S. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res 2002, 110, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, Y.; Imakura, A.; Fujii, A.; Ohmori, T. Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale: Validation of the Japanese version. Psychiatry Res 2002, 113, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, G.; Hesdon, B.; Wild, D.; Cookson, R.; Farina, C.; Sharma, V.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Jenkinson, C. Self-report quality of life measure for people with schizophrenia: The SQLS. Br J Psychiatry 2000, 177, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, C.; Griffiths, P. A Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and equivalence assessment. J Psychosom Res 2007, 62, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Accept Commitment Ther Meas Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Bodlund, O.; Kullgren, G.; Ekselius, L.; Lindström, E.; von Knorring, L. Axis V--Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Evaluation of a self-report version. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994, 90, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; Cooper, H.; Hedges, L. Parametric measures of effect size. The handbook of research synthesis 1994, 621, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy Izquierdo, D.; Vázquez Pérez, M.L.; Lara Moreno, R.; Godoy García, J.F. Training coping skills and coping with stress self-efficacy for successful daily functioning and improved clinical status in patients with psychosis: A randomized controlled pilot study. Sci Prog 2021, 104, 368504211056818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrier, N.; Beckett, R.; Harwood, S.; Baker, A.; Yusupoff, L.; Ugarteburu, I. A trial of two cognitive-behavioural methods of treating drug-resistant residual psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients: I. Outcome. Br J Psychiatry 1993, 162, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, R.; Chiliza, B.; Asmal, L.; Harvey, B.H. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelovich, S.L.; Strachan, E.; Sivec, H.; Kreider, V. Stepped care as an implementation and service delivery model for cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis. Community Ment Health J 2019, 55, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelovich, S.L.; Maura, J.; Blank, J.; Lockwood, G. Sequential mixed method evaluation of the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis stepped care. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazell, C.M.; Hayward, M.; Cavanagh, K.; Strauss, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of low intensity CBT for psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016, 45, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimhy, D.; Tarrier, N.; Essock, S.; Malaspina, D.; Cabannis, D.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis - Training practices and dissemination in the United States. Psychosis 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, F.; Johal, R.; McKenna, C.; Rathod, S.; Ayub, M.; Lecomte, T.; Husain, N.; Kingdon, D.; Farooq, S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for psychosis based Guided Self-help (CBTp-GSH) delivered by frontline mental health professionals: Results of a feasibility study. Schizophr Res 2016, 173, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).