Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

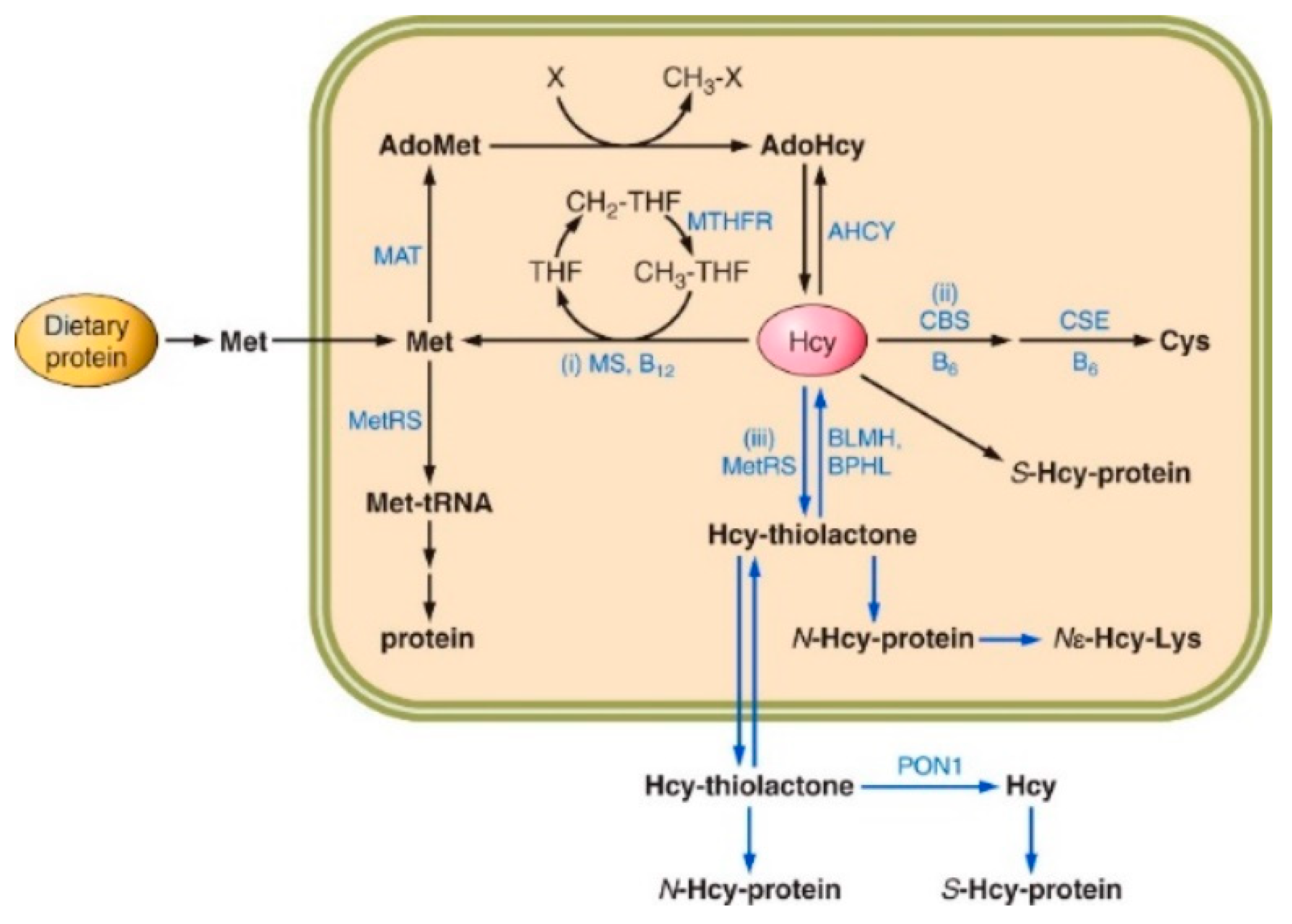

2. Homocysteine Metabolism

3. Homocysteine Thiolactone

4. N-Homocysteinylated Proteins

5. Hcy-Thiolactone Hydrolyzing Enzymes

5.1. Paraoxonase 1

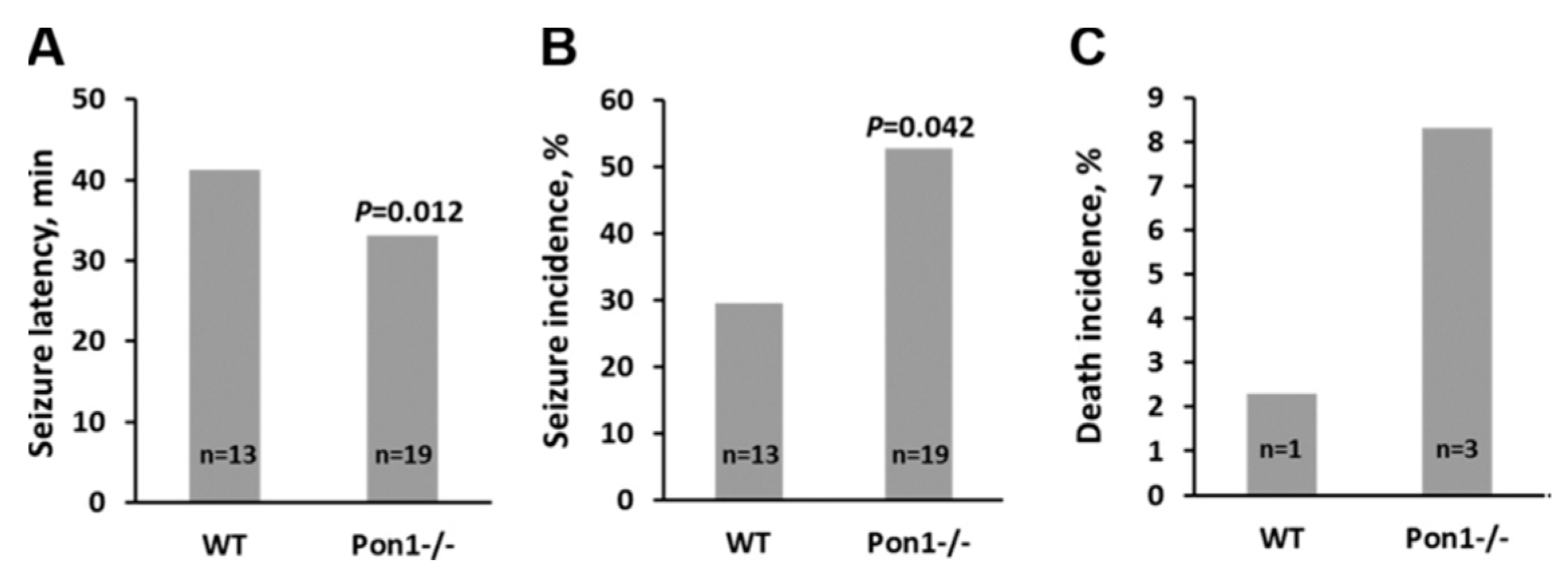

5.1.1. Consequences of Pon1 Gene Ablation

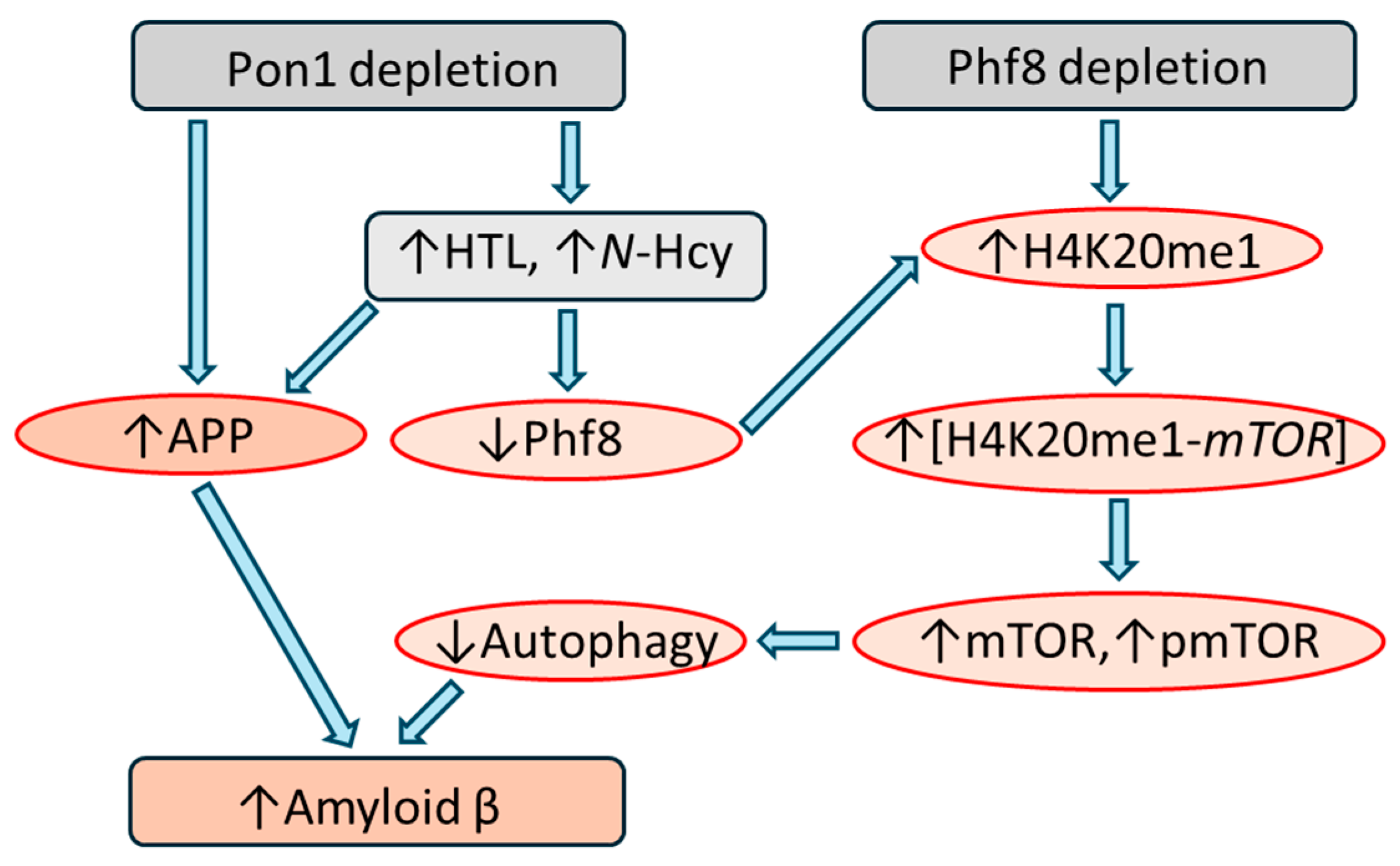

5.1.2. Pon1 Depletion Downregulates Phf8, Upregulates mTOR Signaling, Inhibits Autophagy

5.1.3. Pon1 Depletion Upregulates App and Aβ

5.1.4. Pon1 Interacts with App but Phf8 Does Not

5.1.5. Similar Effects of Pon1 Depletion and Hcy-Thiolactone/N-Hcy-Protein on Pathways Leading to Aβ

5.2. Bleomycin Hydrolase

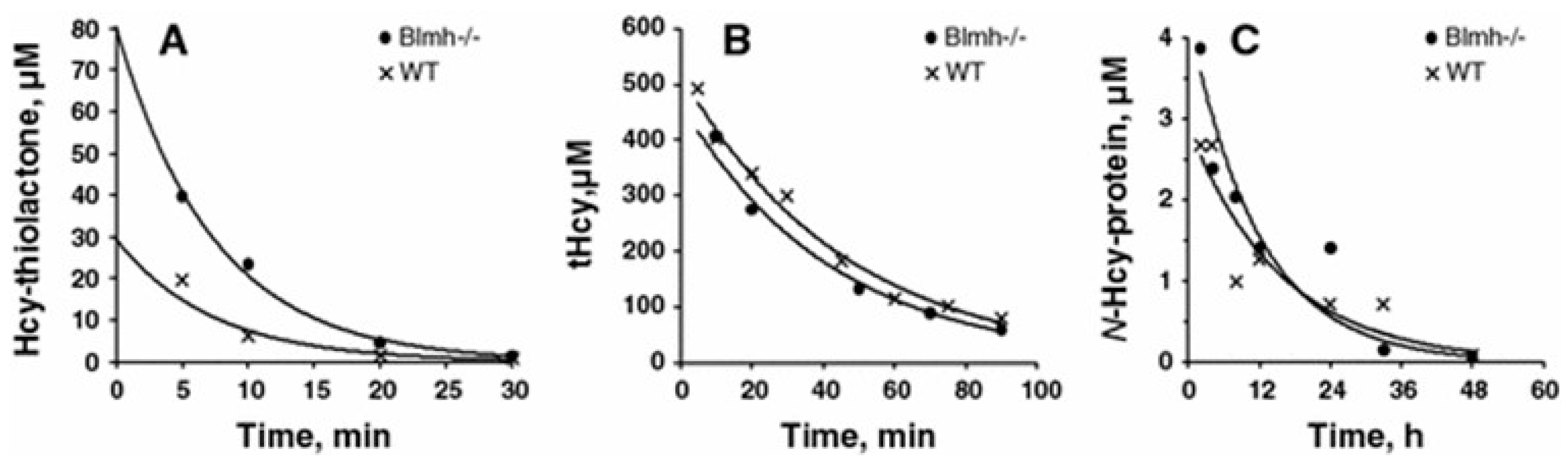

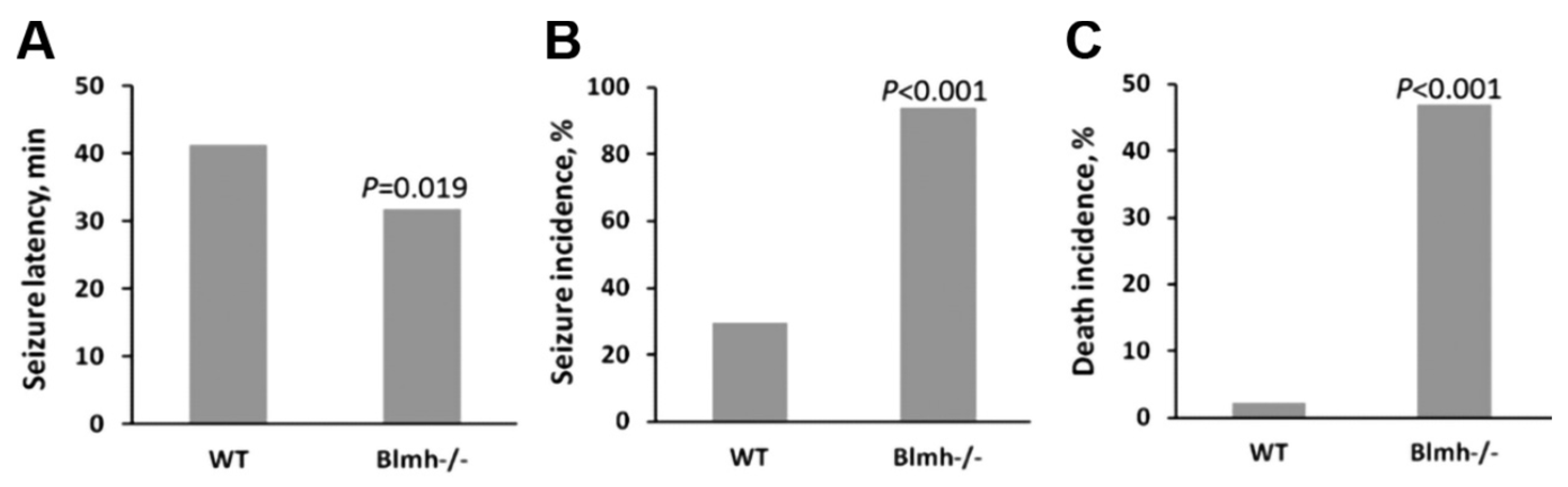

5.2.1. Consequences of Blmh Gene Ablation

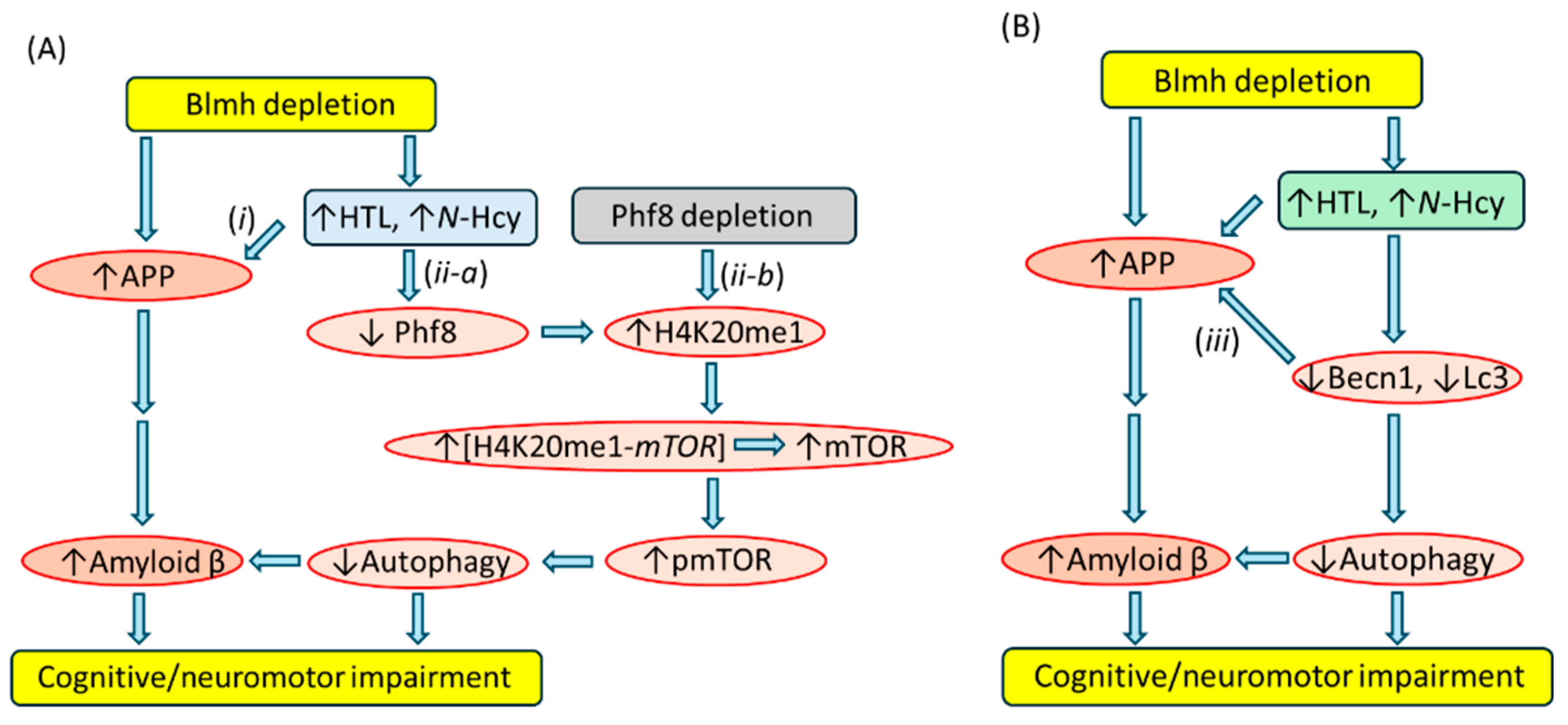

5.2.2. Blmh Depletion Downregulates Phf8, Upregulates mTOR Signaling, Inhibits Autophagy

5.2.3. Blmh Depletion Upregulates App and Aβ and Worsens Cognitive and Neuromotor Deficits

5.2.4. Treatments with Hcy-Thiolactone or N-Hcy-Protein Mimicked the Effects of Blmh Depletion

5.2.5. Blmh Interacts with App, but Phf8 Does Not

5.2.6. Becn1 Interacts with App

5.2.7. Similar Effects of Blmh Depletion and Hcy-Thiolactone/N-Hcy-Protein on Pathways Leading to Aβ

5.3. Biphenyl Hydrolase-Like Enzyme

5.3.1. Consequences of Bphl Ablation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2021, 17, 327–406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzi, R. E. (2012) The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2.

- Dorszewska, J., Prendecki, M., Oczkowska, A., Dezor, M., and Kozubski, W. (2016) Molecular Basis of Familial and Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 13, 952-963.

- Smith, A. D., and Refsum, H. (2021) Homocysteine - from disease biomarker to disease prevention. J Intern Med 290, 826-854.

- Mudd, S.; Skovby, F.; Levy, H.; Pettigrew, K.; Wilcken, B.; Pyeritz, R.; Andria, G.; Boers, G.; Bromberg, I.; Cerone, R.; et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1985, 37, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kozich, V., Sokolova, J., Morris, A. A. M., Pavlikova, M., Gleich, F., Kolker, S., Krijt, J., Dionisi-Vici, C., Baumgartner, M. R., Blom, H. J., Huemer, M., and consortium, E. H. (2021) Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in the E-HOD registry-part I: pyridoxine responsiveness as a determinant of biochemical and clinical phenotype at diagnosis. J Inherit Metab Dis 44, 677-692.

- Chwatko, G., Boers, G. H., Strauss, K. A., Shih, D. M., and Jakubowski, H. (2007) Mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase or cystathionine beta-synthase gene, or a high-methionine diet, increase homocysteine thiolactone levels in humans and mice. Faseb J 21, 1707-1713.

- Jakubowski, H., Boers, G. H., and Strauss, K. A. (2008) Mutations in cystathionine {beta}-synthase or methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene increase N-homocysteinylated protein levels in humans. FASEB J 22, 4071-4076.

- Jakubowski, H. Homocysteine Modification in Protein Structure/Function and Human Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 555–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bashir, H., Dekair, L., Mahmoud, Y., and Ben-Omran, T. (2015) Neurodevelopmental and Cognitive Outcomes of Classical Homocystinuria: Experience from Qatar. JIMD Rep 21, 89-95.

- Abbott, M. H., Folstein, S. E., Abbey, H., and Pyeritz, R. E. (1987) Psychiatric manifestations of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: prevalence, natural history, and relationship to neurologic impairment and vitamin B6-responsiveness. Am J Med Genet 26, 959-969.

- Sachdev, P.S.; Valenzuela, M.; Wang, X.L.; Looi, J.C.; Brodaty, H. Relationship between plasma homocysteine levels and brain atrophy in healthy elderly individuals. Neurology 2002, 58, 1539–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, S.; Bandelow, B.; Javaheripour, K.; Müller, A.; Degner, D.; Wilhelm, J.; Havemann-Reinecke, U.; Sperling, W.; Rüther, E.; Kornhuber, J. Hyperhomocysteinemia as a new risk factor for brain shrinkage in patients with alcoholism. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 335, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, R.; Smith, A.D.; Jobst, K.A.; Refsum, H.; Sutton, L.; Ueland, P.M. Folate, Vitamin B12, and Serum Total Homocysteine Levels in Confirmed Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 1998, 55, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, S.C.; Zafar, A.; Hubbard, P.; Nagy, S.; Durant, S.; Bicknell, R.; Wilcock, G.; Christie, S.; Esiri, M.M.; Smith, A.D.; et al. Dysfunction of the mTOR pathway is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2013, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majtan, T., Park, I., Cox, A., Branchford, B. R., di Paola, J., Bublil, E. M., and Kraus, J. P. (2019) Behavior, body composition, and vascular phenotype of homocystinuric mice on methionine-restricted diet or enzyme replacement therapy. FASEB J 33, 12477-12486.

- Akahoshi, N., Kobayashi, C., Ishizaki, Y., Izumi, T., Himi, T., Suematsu, M., and Ishii, I. (2008) Genetic background conversion ameliorates semi-lethality and permits behavioral analyses in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice, an animal model for hyperhomocysteinemia. Hum Mol Genet 17, 1994-2005.

- Witucki, L., and Jakubowski, H. (2023) Homocysteine metabolites inhibit autophagy, elevate amyloid beta, and induce neuropathy by impairing Phf8/H4K20me1-dependent epigenetic regulation of mTOR in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. J Inherit Metab Dis.

- Khayati, K.; Antikainen, H.; Bonder, E.M.; Weber, G.F.; Kruger, W.D.; Jakubowski, H.; Dobrowolski, R. The amino acid metabolite homocysteine activates mTORC1 to inhibit autophagy and form abnormal proteins in human neurons and mice. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. Protein homocysteinylation: possible mechanism underlying pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H., Zhang, L., Bardeguez, A., and Aviv, A. (2000) Homocysteine thiolactone and protein homocysteinylation in human endothelial cells: implications for atherosclerosis. Circ Res 87, 45-51.

- Jakubowski, H. (2013) Homocysteine in Protein Structure/Function and Human Disease - Chemical Biology Of Homocysteine-containing Proteins, Springer, Wien.

- Jakubowski, H. Protein N-Homocysteinylation and Colorectal Cancer. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H. Calcium-dependent Human Serum Homocysteine Thiolactone Hydrolase. A protective mechanism against protein N-homocysteinylation. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 3957–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimny, J., Sikora, M., Guranowski, A., and Jakubowski, H. (2006) Protective mechanisms against homocysteine toxicity: the role of bleomycin hydrolase. J Biol Chem 281, 22485-22492.

- Zimny, J., Bretes, E., and Guranowski, A. (2010) Novel mammalian homocysteine thiolactone hydrolase: Purification and characterization. Acta Biochimica Polonica 57 Suppl 4, 134.

- Zimny, J., Bretes, E., Grygiel, D., Guranowski, A. (2011) Human mitochondrial homocysteine thiolactone hydrolase; overexpression and purification. Acta Biochimica Polonica 58 Suppl 4, 57.

- Marsillach, J.; Suzuki, S.M.; Richter, R.J.; McDonald, M.G.; Rademacher, P.M.; MacCoss, M.J.; Hsieh, E.J.; Rettie, A.E.; Furlong, C.E. Human Valacyclovir Hydrolase/Biphenyl Hydrolase-Like Protein Is a Highly Efficient Homocysteine Thiolactonase. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Pratt, J. Genetic determinants of homocysteine thiolactonase activity in humans: implications for atherosclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2001, 491, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H. Molecular basis of homocysteine toxicity in humans. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. Pathophysiological Consequences of Homocysteine Excess. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1741S–1749S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B., Du Vigneaud, V. (1935) The isolation of homocysteine and its conversion to a thiolactone. J. Biol. Chem. 112, 149-154.

- Butz, L. W., du Vigneaud, V. (1932) The formation of homologue of cysteine by the decomposition of methionine with sulfuric acid. J Biol Chem 99, 135-142.

- de la Haba, G.; Cantoni, G. The Enzymatic Synthesis of S-Adenosyl-l-homocysteine from Adenosine and Homocysteine. J. Biol. Chem. 1959, 234, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.D. Homocysteine: A History in Progress. Nutr. Rev. 2000, 58, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H., and Goldman, E. (1993) Synthesis of homocysteine thiolactone by methionyl-tRNA synthetase in cultured mammalian cells. FEBS Lett 317, 237-240.

- Jakubowski, H. Metabolism of homocysteine thiolactone in human cell cultures. Possible mechanism for pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H. (1997) Synthesis of homocysteine thiolactone in normal and malignant cells. In Homocysteine Metabolism: From Basic Science to Clinical Medicine (Rosenberg, I. H., Graham, I., Ueland, P. M., and Refsum, H., eds) pp. 157-165, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA.

- Jakubowski, H.; Perła-Kaján, J.; Finnell, R.H.; Cabrera, R.M.; Wang, H.; Gupta, S.; Kruger, W.D.; Kraus, J.P.; Shih, D.M. Genetic or nutritional disorders in homocysteine or folate metabolism increase proteinN-homocysteinylation in mice. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baernstein, H.D. A modification of the method for determining methionine in proteins. J Biol Chem. 1934, 106, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H. (2007) Facile syntheses of [35S]homocysteine-thiolactone, [35S]homocystine, [35S]homocysteine, and [S-nitroso-35S]homocysteine Analytical biochemistry 370, 124-126.

- Jakubowski, H. Quality control in tRNA charging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2012, 3, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. (2017) Homocysteine Editing, Thioester Chemistry, Coenzyme A, and the Origin of Coded Peptide Synthesis dagger. Life (Basel) 7.

- Jakubowski, H. (1990) Proofreading in vivo: editing of homocysteine by methionyl-tRNA synthetase in Escherichia coli Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87, 4504-4508.

- Jakubowski, H. (1995) Proofreading in vivo. Editing of homocysteine by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 270, 17672-17673.

- Jakubowski, H. (1991) Proofreading in vivo: editing of homocysteine by methionyl-tRNA synthetase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Embo J 10, 593-598.

- Jakubowski, H.; Guranowski, A. Metabolism of Homocysteine-thiolactone in Plants. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 6765–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowczyk, K.; Piechocka, J.; Głowacki, R.; Dhar, I.; Midtun, Ø.; Tell, G.S.; Ueland, P.M.; Nygård, O.; Jakubowski, H. Urinary excretion of homocysteine thiolactone and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in coronary artery disease patients: the WENBIT trial. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. Quality control in tRNA charging -- editing of homocysteine. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. (2015) Transfer RNA Synthetase Editing of Errors in Amino Acid Selection. In eLS pp. 1-18, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester.

- Borowczyk, K.; Tisończyk, J.; Jakubowski, H. Metabolism and neurotoxicity of homocysteine thiolactone in mice: protective role of bleomycin hydrolase. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowczyk, K.; Shih, D.M.; Jakubowski, H. Metabolism and Neurotoxicity of Homocysteine Thiolactone in Mice: Evidence for a Protective Role of Paraoxonase 1. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2012, 30, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głowacki, R.; Jakubowski, H. Cross-talk between Cys34 and Lysine Residues in Human Serum Albumin Revealed by N-Homocysteinylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10864–10871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikora, M.; Marczak, L.; Twardowski, T.; Stobiecki, M.; Jakubowski, H. Direct monitoring of albumin lysine-525 N-homocysteinylation in human serum by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 405, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marczak, L., Sikora, M., Stobiecki, M., and Jakubowski, H. (2011) Analysis of site-specific N-homocysteinylation of human serum albumin in vitro and in vivo using MALDI-ToF and LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry. J Proteomics 74, 967-974.

- Paoli, P.; Sbrana, F.; Tiribilli, B.; Caselli, A.; Pantera, B.; Cirri, P.; De Donatis, A.; Formigli, L.; Nosi, D.; Manao, G.; et al. Protein N-Homocysteinylation Induces the Formation of Toxic Amyloid-Like Protofibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 400, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undas, A., Perla, J., Lacinski, M., Trzeciak, W., Kazmierski, R., and Jakubowski, H. (2004) Autoantibodies against N-homocysteinylated proteins in humans: implications for atherosclerosis. Stroke 35, 1299-1304.

- Perla, J., Undas, A., Twardowski, T., and Jakubowski, H. (2004) Purification of antibodies against N-homocysteinylated proteins by affinity chromatography on Nomega-homocysteinyl-aminohexyl-Agarose. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 807, 257-261.

- Perła-Kaján, J., Stanger, O., Ziółkowska, A., Melandowicz, L. K., Twardowski, T., and Jakubowski, H. (2007) Immunohistochemical detection of N-homocysteinylated proteins in cardiac surgery patients. Clin Chem Lab Med 45, A36.

- Gurda, D.; Handschuh, L.; Kotkowiak, W.; Jakubowski, H. Homocysteine thiolactone and N-homocysteinylated protein induce pro-atherogenic changes in gene expression in human vascular endothelial cells. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 1319–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Marczak, L.; Kubalska, J.; Graban, A.; Jakubowski, H. Identification of N-homocysteinylation sites in plasma proteins. Amino Acids 2013, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauls, D.L.; Lockhart, E.; Warren, M.E.; Lenkowski, A.; Wilhelm, S.E.; Hoffman, M. Modification of Fibrinogen by Homocysteine Thiolactone Increases Resistance to Fibrinolysis: A Potential Mechanism of the Thrombotic Tendency in Hyperhomocysteinemia. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 2480–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akchiche, N., Bossenmeyer-Pourie, C., Kerek, R., Martin, N., Pourie, G., Koziel, V., Helle, D., Alberto, J. M., Ortiou, S., Camadro, J. M., Leger, T., Gueant, J. L., and Daval, J. L. (2012) Homocysteinylation of neuronal proteins contributes to folate deficiency-associated alterations of differentiation, vesicular transport, and plasticity in hippocampal neuronal cells. FASEB J 26, 3980-3992.

- Zhou, L., Guo, T., Meng, L., Zhang, X., Tian, Y., Dai, L., Niu, X., Li, Y., Liu, C., Chen, G., Liu, C., Ke, W., Zhang, Z., Bao, A., and Zhang, Z. (2023) N-homocysteinylation of alpha-synuclein promotes its aggregation and neurotoxicity. Aging Cell 22, e13745.

- Guo, T., Zhou, L., Xiong, M., Xiong, J., Huang, J., Li, Y., Zhang, G., Chen, G., Wang, Z. H., Xiao, T., Hu, D., Bao, A., and Zhang, Z. (2024) N-homocysteinylation of DJ-1 promotes neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Aging Cell, e14124.

- Mei, X.; Qi, D.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, P.; et al. Inhibiting MARSs reduces hyperhomocysteinemia-associated neural tube and congenital heart defects. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e9469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, R.; Qu, Y.-Y.; Mei, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.-B.; Zuo, Z.-G.; Chen, Y.-M.; et al. Colonic Lysine Homocysteinylation Induced by High-Fat Diet Suppresses DNA Damage Repair. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 398–412.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H. Homocysteine Thiolactone: Metabolic Origin and Protein Homocysteinylation in Humans. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 377S–381S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perla-Kajan, J., and Jakubowski, H. (2010) Paraoxonase 1 protects against protein N-homocysteinylation in humans. FASEB J 24, 931-936.

- Sikora, M., Marczak, L., Suszynska-Zajczyk, J., Jakubowski, H. (2012) Monitoring site-specific N-homocysteinylation in fibrinogen in vitro and in vivo as a potential marker of thrombosis in CBS-deficient patients. In 22nd International Fibrinogen Workshop Vol. Abstract Book, P018 p. 94, International Fibrinogen Research Society (IFRS), Brighton, UK.

- Perla-Kajan, J., Utyro, O., Rusek, M., Malinowska, A., Sitkiewicz, E., and Jakubowski, H. (2016) N-Homocysteinylation impairs collagen cross-linking in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice: a novel mechanism of connective tissue abnormalities. FASEB J 30, 3810-3821.

- Xu, L.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, P. Crosstalk of homocysteinylation, methylation and acetylation on histone H3. Anal. 2015, 140, 3057–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Liu, J.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. Chemical proteomic profiling of proteinN-homocysteinylation with a thioester probe. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2826–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bai, B.; Mei, X.; Wan, C.; Cao, H.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; et al. Elevated H3K79 homocysteinylation causes abnormal gene expression during neural development and subsequent neural tube defects. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossenmeyer-Pourie, C., Smith, A. D., Lehmann, S., Deramecourt, V., Sablonniere, B., Camadro, J. M., Pourie, G., Kerek, R., Helle, D., Umoret, R., Gueant-Rodriguez, R. M., Rigau, V., Gabelle, A., Sequeira, J. M., Quadros, E. V., Daval, J. L., and Gueant, J. L. (2019) N-homocysteinylation of tau and MAP1 is increased in autopsy specimens of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. J Pathol 248, 291-303.

- Perła-Kaján, J.; Jakubowski, H. Paraoxonase 1 and homocysteine metabolism. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsillach, J., Mackness, B., Mackness, M., Riu, F., Beltran, R., Joven, J., and Camps, J. (2008) Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases-1, 2, and 3 expression in normal mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med 45, 146-157.

- Costa, L.G.; Giordano, G.; Cole, T.B.; Marsillach, J.; Furlong, C.E. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) as a genetic determinant of susceptibility to organophosphate toxicity. Toxicology 2012, 307, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, T.; Nicholls, S.J.; Topol, E.J.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Schmitt, D.; Fu, X.; Shao, M.; Brennan, D.M.; Ellis, S.G.; et al. Relationship of Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Gene Polymorphisms and Functional Activity With Systemic Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Risk. JAMA 2008, 299, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.W.; Hartiala, J.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Stewart, A.F.; Erdmann, J.; Kathiresan, S.; Roberts, R.; McPherson, R.; Allayee, H.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Association of Serum Paraoxonase and Arylesterase Activities With Cardiovascular Risk. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 2803–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.J.; Tang, W.H.W.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Mann, S.; Pepoy, M.; Hazen, S.L. Diminished Antioxidant Activity of High-Density Lipoprotein-Associated Proteins in Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2013, 2, e000104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Dohi, T.; Miyauchi, K.; Ogita, M.; Kurano, M.; Ohkawa, R.; Nakamura, K.; Tamura, H.; Isoda, K.; Okazaki, S.; et al. Prognostic impact of homocysteine levels and homocysteine thiolactonase activity on long-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Bakker, S.J.; James, R.W.; Dullaart, R.P. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: The PREVEND study and meta-analysis of prospective population studies. Atherosclerosis 2015, 245, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, D.M.; Gu, L.; Xia, Y.-R.; Navab, M.; Li, W.-F.; Hama, S.; Castellani, L.W.; Furlong, C.E.; Costa, L.G.; Fogelman, A.M.; et al. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphate toxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature 1998, 394, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, D.M.; Xia, Y.-R.; Wang, X.-P.; Miller, E.; Castellani, L.W.; Subbanagounder, G.; Cheroutre, H.; Faull, K.F.; Berliner, J.A.; Witztum, J.L.; et al. Combined Serum Paraoxonase Knockout/Apolipoprotein E Knockout Mice Exhibit Increased Lipoprotein Oxidation and Atherosclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17527–17535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikora, M.; Bretes, E.; Perła-Kaján, J.; Lewandowska, I.; Marczak, Ł.; Jakubowski, H. Genetic Attenuation of Paraoxonase 1 Activity Induces Proatherogenic Changes in Plasma Proteomes of Mice and Humans. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikora, M., and Jakubowski, H. (2021) Changes in redox plasma proteome of Pon1-/- mice are exacerbated by a hyperhomocysteinemic diet. Free Radic Biol Med 169, 169-180.

- Perla-Kajan, J.; Borowczyk, K.; Glowacki, R.; Nygard, O.; Jakubowski, H. Paraoxonase 1 Q192R genotype and activity affect homocysteine thiolactone levels in humans. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 6019–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tward, A.; Xia, Y.-R.; Wang, X.-P.; Shi, Y.-S.; Park, C.; Castellani, L.W.; Lusis, A.J.; Shih, D.M.; A, R.; M, W.; et al. Decreased Atherosclerotic Lesion Formation in Human Serum Paraoxonase Transgenic Mice. Circulation 2002, 106, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menini, T.; Gugliucci, A. Paraoxonase 1 in neurological disorders. Redox Rep. 2013, 19, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsillach, J.; Adorni, M.P.; Zimetti, F.; Papotti, B.; Zuliani, G.; Cervellati, C. HDL Proteome and Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence of a Link. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervellati, C. Valacchi, G., Tisato, V., Zuliani, G., and Marsillach, J. (2019) Evaluating the link between Paraoxonase-1 levels and Alzheimer's disease development. Minerva Med 110, 238-250.

- de la Torre, J.C. (2002) Alzheimer disease as a vascular disorder: nosological evidence. Stroke 33, 1152-1162.

- Costa, L. G., Cole, T. B., Jarvik, G. P., and Furlong, C. E. (2003) Functional genomic of the paraoxonase (PON1) polymorphisms: effects on pesticide sensitivity, cardiovascular disease, and drug metabolism. Annu Rev Med 54, 371-392.

- Moren, X.; Lhomme, M.; Bulla, A.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Kontush, A.; James, R.W. Proteomic and lipidomic analyses of paraoxonase defined high density lipoprotein particles: Association of paraoxonase with the anti-coagulant, protein S. Proteom. – Clin. Appl. 2015, 10, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlich, P.M.; Lunetta, K.L.; Cupples, L.A.; Abraham, C.R.; Green, R.C.; Baldwin, C.T.; Farrer, L.A. Serum paraoxonase activity is associated with variants in the PON gene cluster and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1015.e7–1015.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska-Makaruk, M.E.; Krzywkowski, T.; Graban, A.; Lipczyńska-Łojkowska, W.; Bochyńska, A.; Rodo, M.; Wehr, H.; Ryglewicz, D.K. Original article Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene -108C>T and p.Q192R polymorphisms and arylesterase activity of the enzyme in patients with dementia. Folia Neuropathol. 2013, 2, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantoine, T. F., Debord, J., Merle, L., Lacroix-Ramiandrisoa, H., Bourzeix, L., and Charmes, J. P. (2002) Paraoxonase 1 activity: a new vascular marker of dementia? Ann N Y Acad Sci 977, 96-101.

- Paragh, G., Balla, P., Katona, E., Seres, I., Egerhazi, A., and Degrell, I. (2002) Serum paraoxonase activity changes in patients with Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 252, 63-67.

- Bednarz-Misa, I.; Berdowska, I.; Zboch, M.; Misiak, B.; Zieliński, B.; Płaczkowska, S.; Fleszar, M.; Wiśniewski, J.; Gamian, A.; Krzystek-Korpacka, M. Paraoxonase 1 decline and lipid peroxidation rise reflect a degree of brain atrophy and vascular impairment in dementia. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perla-Kajan, J., Wloczkowska, O., Ziola-Frankowska, A., Frankowski, M., Smith, A. D., de Jager, C. A., Refsum, H., and Jakubowski, H. (2021) Paraoxonase 1, B Vitamins Supplementation, and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 81, 1211-1229.

- Aluganti Narasimhulu, C., Mitra, C., Bhardwaj, D., Burge, K. Y., and Parthasarathy, S. (2019) Alzheimer's Disease Markers in Aged ApoE-PON1 Deficient Mice. J Alzheimers Dis 67, 1353-1365.

- Salazar, J.G.; Marsillach, J.; Reverte, I.; Mackness, B.; Mackness, M.; Joven, J.; Camps, J.; Colomina, M.T. Paraoxonase-1 and -3 Protein Expression in the Brain of the Tg2576 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. The susceptibility of humans to neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental toxicities caused by organophosphorus pesticides. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 3037–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suszyńska-Zajczyk, J.; Łuczak, M.; Marczak, Ł.; Jakubowski, H. Inactivation of the Paraoxonase 1 Gene Affects the Expression of Mouse Brain Proteins Involved in Neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2014, 42, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, M. C., James, R. W., Messmer, S., Barja, F., and Pometta, D. (1993) Identification of a distinct human high-density lipoprotein subspecies defined by a lipoprotein-associated protein, K-45. Identity of K-45 with paraoxonase. Eur J Biochem 211, 871-879.

- Witucki, L., and Jakubowski, H. (2023) Depletion of Paraoxonase 1 (Pon1) Dysregulates mTOR, Autophagy, and Accelerates Amyloid Beta Accumulation in Mice. Cells 12.

- Kamata, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Kajiya, A.; Karasawa, S.; Sakatani, C.; Takekoshi, S.; Osamura, R.Y.; Takeda, A. Quantification of Neutral Cysteine Protease Bleomycin Hydrolase and its Localization in Rat Tissues. J. Biochem. 2006, 141, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromme, D., Rossi, A. B., Smeekens, S. P., Anderson, D. C., and Payan, D. G. (1996) Human bleomycin hydrolase: molecular cloning, sequencing, functional expression, and enzymatic characterization. Biochemistry 35, 6706-6714.

- O'Farrell, P. A., Gonzalez, F., Zheng, W., Johnston, S. A., and Joshua-Tor, L. (1999) Crystal structure of human bleomycin hydrolase, a self-compartmentalizing cysteine protease. Structure 7, 619-627.

- Suszynska, J., Tisonczyk, J., Lee, H. G., Smith, M. A., and Jakubowski, H. (2010) Reduced homocysteine-thiolactonase activity in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 1177-1183.

- Kajiya, A., Kaji, H., Isobe, T., and Takeda, A. (2006) Processing of amyloid beta-peptides by neutral cysteine protease bleomycin hydrolase. Protein and peptide letters 13, 119-123.

- Papassotiropoulos, A., Bagli, M., Jessen, F., Frahnert, C., Rao, M. L., Maier, W., and Heun, R. (2000) Confirmation of the association between bleomycin hydrolase genotype and Alzheimer's disease. Molecular psychiatry 5, 213-215.

- Lefterov, I.M.; Koldamova, R.P.; Lefterova, M.I.; Schwartz, D.R.; Lazo, J.S. Cysteine 73 in Bleomycin Hydrolase Is Critical for Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 283, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajiya, A., Kaji, H., Isobe, T., and Takeda, A. (2006) Processing of amyloid beta-peptides by neutral cysteine protease bleomycin hydrolase. Protein and Peptide Letters 13, 119-123.

- Kamata, Y.; Taniguchi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Nomura, J.; Ishihara, K.; Takahara, H.; Hibino, T.; Takeda, A. Neutral Cysteine Protease Bleomycin Hydrolase Is Essential for the Breakdown of Deiminated Filaggrin into Amino Acids. 2009, 284, 12829–12836. [CrossRef]

- Ratovitski, T.; Chighladze, E.; Waldron, E.; Hirschhorn, R.R.; Ross, C.A. Cysteine Proteases Bleomycin Hydrolase and Cathepsin Z Mediate N-terminal Proteolysis and Toxicity of Mutant Huntingtin. 2011, 286, 12578–12589. [CrossRef]

- Okamura, Y.; Nomoto, S.; Hayashi, M.; Hishida, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Fujii, T.; Sugimoto, H.; Takeda, S.; Kodera, Y.; et al. Identification of the bleomycin hydrolase gene as a methylated tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel triple-combination array method. Cancer Lett. 2011, 312, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamata, Y.; Maejima, H.; Watarai, A.; Saito, N.; Katsuoka, K.; Takeda, A.; Ishihara, K. Expression of bleomycin hydrolase in keratinization disorders. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 304, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Jakasa, I.; Riethmüller, C.; Schön, M.P.; Braun, A.; Haftek, M.; Fallon, P.G.; Wróblewski, J.; Jakubowski, H.; Eckhart, L.; et al. Filaggrin Expression and Processing Deficiencies Impair Corneocyte Surface Texture and Stiffness in Mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 615–623.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, S. E., Aston, C. E., DeKosky, S. T., Kamboh, M. I., Lazo, J. S., and Ferrell, R. E. (1998) Bleomycin hydrolase is associated with risk of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet 18, 211-212.

- Namba, Y., Ouchi, Y., Asada, T., Hattori, H., Ueki, A., and Ikeda, K. (1999) Lack of association between bleomycin hydrolase gene polymorphism and Alzheimer's disease in Japanese people. Ann Neurol 46, 136-137.

- Farrer, L. A., Abraham, C. R., Haines, J. L., Rogaeva, E. A., Song, Y., McGraw, W. T., Brindle, N., Premkumar, S., Scott, W. K., Yamaoka, L. H., Saunders, A. M., Roses, A. D., Auerbach, S. A., Sorbi, S., Duara, R., Pericak-Vance, M. A., and St George-Hyslop, P. H. (1998) Association between bleomycin hydrolase and Alzheimer's disease in caucasians. Ann Neurol 44, 808-811.

- Thome, J., Gewirtz, J. C., Sakai, N., Zachariou, V., Retz-Junginger, P., Retz, W., Duman, R. S., and Rosler, M. (1999) Polymorphisms of the human apolipoprotein E promoter and bleomycin hydrolase gene: risk factors for Alzheimer's dementia? Neurosci Lett 274, 37-40.

- Schwartz, D.R.; Homanics, G.E.; Hoyt, D.G.; Klein, E.; Abernethy, J.; Lazo, J.S. The neutral cysteine protease bleomycin hydrolase is essential for epidermal integrity and bleomycin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4680–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, S.; Thiels, E.; Card, J.; Lazo, J. Astrogliosis and behavioral changes in mice lacking the neutral cysteine protease bleomycin hydrolase. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towne, C.F.; York, I.A.; Watkin, L.B.; Lazo, J.S.; Rock, K.L. Analysis of the Role of Bleomycin Hydrolase in Antigen Presentation and the Generation of CD8 T Cell Responses. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 6923–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y., Qian, S., Chen, D., Ye, M., Wu, J., and Wang, Y. L. (2023) Serum BLMH and CKM as Potential Biomarkers for Predicting Therapeutic Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's Disease: A Proteomics Study. J Integr Neurosci 22, 163.

- Okun, M. S. (2012) Deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 367, 1529-1538.

- Thompson, A.G.; Gray, E.; Mäger, I.; Thézénas, M.-L.; Charles, P.D.; Talbot, K.; Fischer, R.; Kessler, B.M.; Wood, M.; Turner, M.R. CSF extracellular vesicle proteomics demonstrates altered protein homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Proteom. 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suszyńska-Zajczyk, J.; Łuczak, M.; Marczak, Ł.; Jakubowski, H. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Bleomycin Hydrolase Modulate the Expression of Mouse Brain Proteins Involved in Neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2014, 40, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witucki, L., Borowczyk, K., Suszynska-Zajczyk, J., Warzych, E., Pawlak, P., and Jakubowski, H. (2023) Deletion of the Homocysteine Thiolactone Detoxifying Enzyme Bleomycin Hydrolase, in Mice, Causes Memory and Neurological Deficits and Worsens Alzheimer's Disease-Related Behavioral and Biochemical Traits in the 5xFAD Model of Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis.

- Oakley, H., Cole, S. L., Logan, S., Maus, E., Shao, P., Craft, J., Guillozet-Bongaarts, A., Ohno, M., Disterhoft, J., Van Eldik, L., Berry, R., and Vassar, R. (2006) Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci 26, 10129-10140.

- Thinakaran, G., Teplow, D. B., Siman, R., Greenberg, B., and Sisodia, S. S. (1996) Metabolism of the "Swedish" amyloid precursor protein variant in neuro2a (N2a) cells. Evidence that cleavage at the "beta-secretase" site occurs in the golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem 271, 9390-9397.

- Sobering, A.K.; Bryant, L.M.; Li, D.; McGaughran, J.; Maystadt, I.; Moortgat, S.; Graham, J.M.; van Haeringen, A.; Ruivenkamp, C.; Cuperus, R.; et al. Variants in PHF8 cause a spectrum of X-linked neurodevelopmental disorders and facial dysmorphology. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2022, 3, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumonnier, F.; Holbert, S.; Ronce, N.; Faravelli, F.; Lenzner, S.; E Schwartz, C.; Lespinasse, J.; Van Esch, H.; Lacombe, D.; Goizet, C.; et al. Mutations in PHF8 are associated with X linked mental retardation and cleft lip/cleft palate. J. Med Genet. 2005, 42, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Deng, Y.; Yu, L.; et al. Phf8 histone demethylase deficiency causes cognitive impairments through the mTOR pathway. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefterov, I.M.; Koldamova, R.P.; Lazo, J.S. Human bleomycin hydrolase regulates the secretion of amyloid precursor protein. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshua-Tor, L.; Xu, H.E.; Johnston, S.A.; Rees, D.C. Crystal Structure of a Conserved Protease That Binds DNA: the Bleomycin Hydrolase, Gal6. Science 1995, 269, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, A., Higuchi, D., Yamamoto, T., Nakamura, Y., Masuda, Y., Hirabayashi, T., and Nakaya, K. (1996) Purification and characterization of bleomycin hydrolase, which represents a new family of cysteine proteases, from rat skin. Journal of biochemistry 119, 29-36.

- Pickford, F. Masliah, E., Britschgi, M., Lucin, K., Narasimhan, R., Jaeger, P. A., Small, S., Spencer, B., Rockenstein, E., Levine, B., and Wyss-Coray, T. (2008) The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid beta accumulation in mice. J Clin Invest 118, 2190-2199.

- Jaeger, P.A.; Pickford, F.; Sun, C.-H.; Lucin, K.M.; Masliah, E.; Wyss-Coray, T. Regulation of Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing by the Beclin 1 Complex. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perła-Kaján, J.; Jakubowski, H. Dysregulation of Epigenetic Mechanisms of Gene Expression in the Pathologies of Hyperhomocysteinemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente, X. S., and Lopez-Otin, C. (1995) Cloning and expression analysis of a novel human serine hydrolase with sequence similarity to prokaryotic enzymes involved in the degradation of aromatic compounds. J Biol Chem 270, 12926-12932.

- Puente, X.S.; Pendás, A.M.; López-Otı́n, C. Structural Characterization and Chromosomal Localization of the Gene Encoding Human Biphenyl Hydrolase-Related Protein (BPHL). Genomics 1998, 51, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.J.; Doh, M.J.; Kim, I.H.; Kong, H.S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.M. Prednisolone 21-sulfate sodium: a colon-specific pro-drug of prednisolone. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Epling, D., Shi, J., Song, F., Tsume, Y., Zhu, H. J., Amidon, G. L., and Smith, D. E. (2018) Effect of biphenyl hydrolase-like (BPHL) gene disruption on the intestinal stability, permeability and absorption of valacyclovir in wildtype and Bphl knockout mice. Biochem Pharmacol 156, 147-156.

- Lai, L., Xu, Z., Zhou, J., Lee, K. D., and Amidon, G. L. (2008) Molecular basis of prodrug activation by human valacyclovirase, an alpha-amino acid ester hydrolase. J Biol Chem 283, 9318-9327.

- Ren, P.; Zhai, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Z.; Cai, K.; Wang, H. Inhibition of BPHL inhibits proliferation in lung carcinoma cell lines. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witucki, L., Suszyńska-Zajczyk, J., Perła-Kajan, J., Bretes, E., Włoczkowska, O., Jakubowski, H. . (2023) Deletion of the Homocysteine Thiolactone Detoxifying Enzyme Biphenyl Hydrolase-like (Bphl), in Mice, Induces Biochemical and Behavioral Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease. In 14th International Conference One Carbon Metabolism, B Vitamins and Homocysteine & 2nd CluB-12 Annual Symposium (Hcy2023) (Cambridge University, U., ed), Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK.

| Substrate | PON1, % | BLMH, % | BPHL, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

L-Hcy-thiolactone (kcat/Km) |

100 (10 M-1s-1) |

100 (103 M-1s-1) |

100 (7.7x104 M-1s-1) |

| D-Hcy-thiolactone | 24 | <1 | ND |

| γ-Thiobutyrolactone | 545 | <1 | <0.001 |

| N-Acetyl-D, L-HTL | <1 | <1 | <0.001 |

| L-Hse-lactone | ++++ | – | +++ |

| L-Met methyl ester | <1 | ++ | 30 |

| L-Cys methyl ester | <1 | ++ | ++ |

| L-Lys methyl ester | ND | – | – |

| L-Phe ethyl ester | 0 | ND | 16 |

| Nε-Hcy-aminocaproate | ND | ++++ | ND |

| Val(Nε-Hcy-Lys) | ND | ++++ | ND |

| HcyLeuAla | ND | ++++ | ND |

| Bleomycin | ND | 500 | ND |

| Paraoxon | 330 | – | ND |

| Phenyl acetate | 280,000 | – | <0.001 |

| Valacyclovir | – | ND | 22 |

| Genotype | Hcy-thiolactone hydrolase activity*, % | Paraoxonase activity#, % | ||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Pon1-/- | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pon1+/- | 51 | 30 | 50 | 40 |

| Pon1+/+ | 100 | 73 | 100 | 70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).