1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases have become increasingly prevalent as our population has shifted to an older demographic over the last 30 years. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is now the seventh leading cause of the death in the United States and the most common form of neurodegeneration in the elderly [

1]. As our cells age, a functional decline in the machinery that maintains protein homeostasis results in accumulation of damaged, misfolded, and aggregate-prone proteins [

2,

3,

4]. Disruption of proteostasis is considered a hallmark of aging [

5,

6]. Aggregation of specific protein species is a defining feature—and is thought to be involved in pathogenesis—of age-associated neurodegenerative diseases including AD and Huntington’s disease (HD) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Current treatments for these diseases generally target symptoms (cholinergic and glutamatergic signaling in neurons in AD, huntingtin production in HD), but do not address the underlying pathology [

13,

14,

15]. Hundreds of clinical trials targeting different aspects of AD, HD, and other neurodegenerative disease neuropathology—amyloid toxicity, tau toxicity, huntingtin production, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation—have failed to demonstrate efficacy. Identifying effective treatments for AD and HD is a major current focus of scientific resources, and there is a critical need for novel therapeutic strategies.

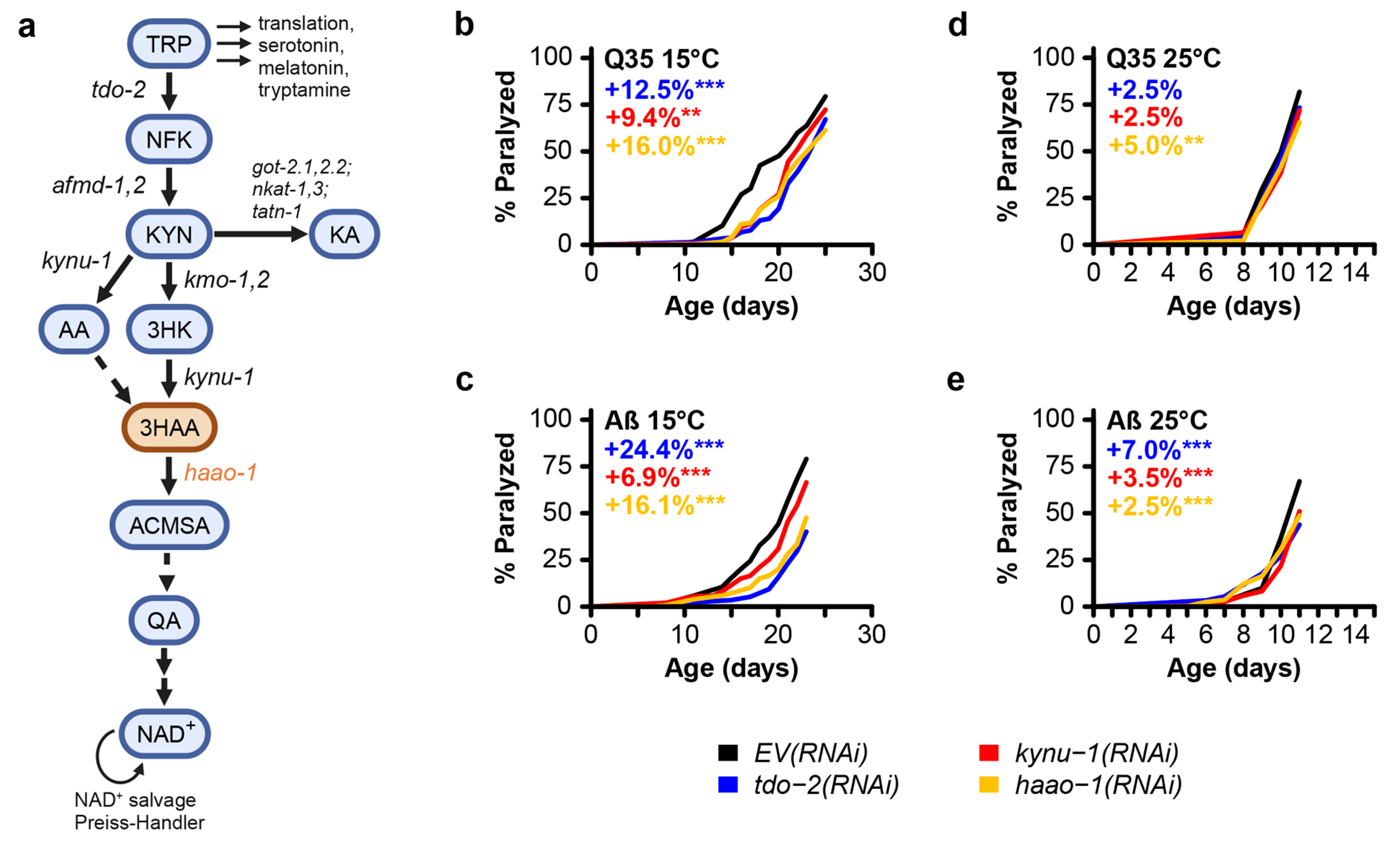

The kynurenine pathway (

Figure 1) is a highly conserved metabolic pathway that converts ingested tryptophan to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) [

16]. Several studies have shown promise in delaying aging and age-associated decline in protein homeostasis through inhibition of tryptophan degradation via the kynurenine pathway. In the roundworm

Caenorhabditis elegans, proteotoxicity is commonly modeled by expressing aggregate-prone proteins in body wall muscle, which causes accumulation of muscle protein aggregates and accelerated paralysis with age [

17,

18]. van der Goot et al. [

19] reported that knockdown of the gene

tdo-2, encoding the kynurenine pathway enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), delayed age-associated pathology in several of these models, including worms expressing human amyloid-beta (Aβ) or a 35-unit polyglutamine tract (Q35), modeling proteotoxicity in AD and HD, respectively. We validated this observation and further found that knockdown of

kynu-1, encoding the kynurenine pathway enzyme kynureninase (KYNU) similarly delays paralysis in these models [

20]. Both interventions extend lifespan in wild type animals, supporting the broader link between maintenance of protein homeostasis and aging [

19,

20]. We recently reported that knockdown of

haao-1, a third kynurenine pathway gene encoding the enzyme 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase (HAAO), increases lifespan in

C. elegans [

21]. Worms lacking

haao-1 accumulate the HAAO metabolic substrate, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3HAA), and supplementing 3HAA in the growth media similarly extends lifespan [

21].

Here we examine the impact of haao-1 inhibition on Aβ and Q35 proteotoxicity in C. elegans. We find that haao-1 knockdown delays paralysis in both contexts but does not prevent Q35 protein aggregation. Supplementing 3HAA similar delays paralysis. The effectiveness at delaying paralysis was also dependent on environmental temperature. We include previously published data on knockdown of tdo-2 or kynu-1 in these models for comparison. These results suggest that inhibition of HAAO or supplementation with 3HAA may hold potential as a clinical intervention for neurodegenerative disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. C. elegans Strains and Maintenance.

The following strains were obtained from the

Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC) in the College of Biological Sciences at the University of Minnesota:

dvIs2[pCL12(unc-54/human Abeta peptide 1-42 minigene) + rol-6(su1006)] (CL2006) and

rmIs132[unc-54p::Q35::YFP] (AM140). We maintained worms on solid nematode growth media (NGM) seeded with

Escherichia coli strain HT115 bacteria at 20°C as previously described [

22]. Worms were age-synchronized via bleach prep and transferred to plates containing 50 μM 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUdR) to prevent reproduction at the L4 larval stage [

22].

2.2. RNA Interference

We conducted RNA interference (RNAi) feeding assays using standard media preparation procedures [

22]. RNAi feeding bacteria were obtained from the Ahringer

C. elegans RNAi feeding library [

23,

24]. All RNAi plasmids were sequenced to verify the correct target sequence. All RNAi experiments were conducted on NGM containing 1 mM Isopropyl β-D-1 thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to activate production of RNAi transcripts and 25 μg/mL carbenicillin to select RNAi plasmids and seeded with live

E. coli (HT115) containing RNAi feeding plasmids. Worms were raised on egg plates seeded with RNAi bacteria until the L4 larval stage, then transferred to FUdR-containing plates seeded with RNAi bacteria as described above.

2.3.3. HAA Supplementation

3HAA supplementation was achieved by adding the appropriate mass of solid 97% pure 3HAA (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number 148776) to NGM media during preparation prior to autoclaving. Worms were raised on egg plates containing 1 mM 3HAA until the L4 larval stage, then transferred to FUdR-containing plates containing 1 mM 3HAA as described above.

2.4. Paralysis Analysis

Paralysis experiments were conducted as previously described [

20,

22]. Briefly, adult worms were maintained on NGM RNAi or 3HAA plates with FUdR for the duration of their lives. Animals were examined every 1-2 days (25°C) or 2-3 days (15°C) by nose- and tail-prodding with a platinum wire pick. Worms were scored as paralyzed if they were unable to move relative to the plate surface. Worms showing vulva rupture were included in all analyses and worms that fled the surface of the plate were excluded. P-values for statistical comparison of paralysis between test groups were calculated using the log rank test (via the

survdiff function in the R “survival” package). For paralysis experiments, raw data is provided in

Appendix A and summary statistics are provided in

Table S1.

2.5. Polyglutamine Aggregate Imaging and Analysis

Polyglutamine aggregate imaging and quantification was completed as previously described [

20]. Briefly, we quantified polyglutamine aggregate number and volume using 3D fluorescence microscopy of transgenic worms expressing fluorescently tagged polyglutamine repeats (Q35::YFP) at 7, 12, and 17 days of age at 15°C and 7 and 11 days of age at 25°C. At least 8 animals were examined for each RNAi at each age. Worms were immobilized using 25 nM sodium azide in M9 buffer on microscope slides with 6% agarose pads. Worms were imaged using a Leica TCS SP8 Laser Scanning Microscope equipped with a 10x objective. Z-stack images were collected for whole worms with stack spacing selected based on the Nyquist sampling theorem (minimum 2.3 images per minimum aggregate diameter). The microscope was set to capture images with resonance scanning and line averaging of 16. Images for worms that did not fit a single field of view were merged with XuvStitch version 1.8.099x64. Protein aggregates in each worm were detected and analyzed using Imaris x64 version 8.1.2. The surface tool was used to identify aggregates with thresholds for minimum fluorescence intensity and aggregate volume to ensure the analyzed surfaces were aggregates and not discrete proteins: surface = 3.0, absolute intensity = 75, seed points = 5:15, intensity > 150, volume > 45, number of voxels > 500. Aggregate volume and number were exported to R for analysis. Two-sided Welch’s t-tests were used to determine significance in observed differences between target and EV RNAi at each age. For aggregate quantification experiments, raw data is provided in

Appendix A and summary statistics are provided in

Table S2.

3. Results

To test the efficacy of

haao-1 disruption at improving proteotoxicity linked to neurodegeneration, we used RNAi to knockdown

haao-1 in

C. elegans transgenically expressing polyglutamine fused to a yellow fluorescence protein (Q35::YFP) or human Aβ in body wall muscle, modeling proteotoxicity in HD and AD, respectively. We include data for both

tdo-2 and

kynu-1 knockdown for comparison [

20]. Similar to previous reports for knockdown of

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

19,

20],

haao-1 knockdown delayed age-associated paralysis in worms at 15 °C (

Figure 1b,c). At 25 °C, the effect was present but much smaller in both models (

Figure 1d,e). These results show that

haao-1 disruption may be protective against AD- and HD-associated proteotoxicity.

Figure 1.

Knockdown of the kynurenine pathway gene

haao-1 delays paralysis in

C. elegans models of polyglutamine and amyloid-beta proteotoxicity. (a) Schematic of the kynurenine pathway in

C. elegans. Knockdown of

haao-1 substantially delayed age-associated pathology in

C. elegans expressing either (b) Aβ or (c) a 35-unit polyglutamine tract (Q35) in body wall muscle at 15 °C to a similar degree as previously reported knockdown of

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

20]. Knockdown of

haao-1 slightly delayed age-associated pathology in

C. elegans expressing either (b) Aβ or (c) a Q35 in body wall muscle at 25 °C to a similar degree as previously reported knockdown of

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

20]. Colored numbers indicate the percent change in mean age of paralysis vs.

EV(RNAi). * p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001 for log rank test vs.

EV(RNAi).

Figure 1.

Knockdown of the kynurenine pathway gene

haao-1 delays paralysis in

C. elegans models of polyglutamine and amyloid-beta proteotoxicity. (a) Schematic of the kynurenine pathway in

C. elegans. Knockdown of

haao-1 substantially delayed age-associated pathology in

C. elegans expressing either (b) Aβ or (c) a 35-unit polyglutamine tract (Q35) in body wall muscle at 15 °C to a similar degree as previously reported knockdown of

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

20]. Knockdown of

haao-1 slightly delayed age-associated pathology in

C. elegans expressing either (b) Aβ or (c) a Q35 in body wall muscle at 25 °C to a similar degree as previously reported knockdown of

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

20]. Colored numbers indicate the percent change in mean age of paralysis vs.

EV(RNAi). * p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001 for log rank test vs.

EV(RNAi).

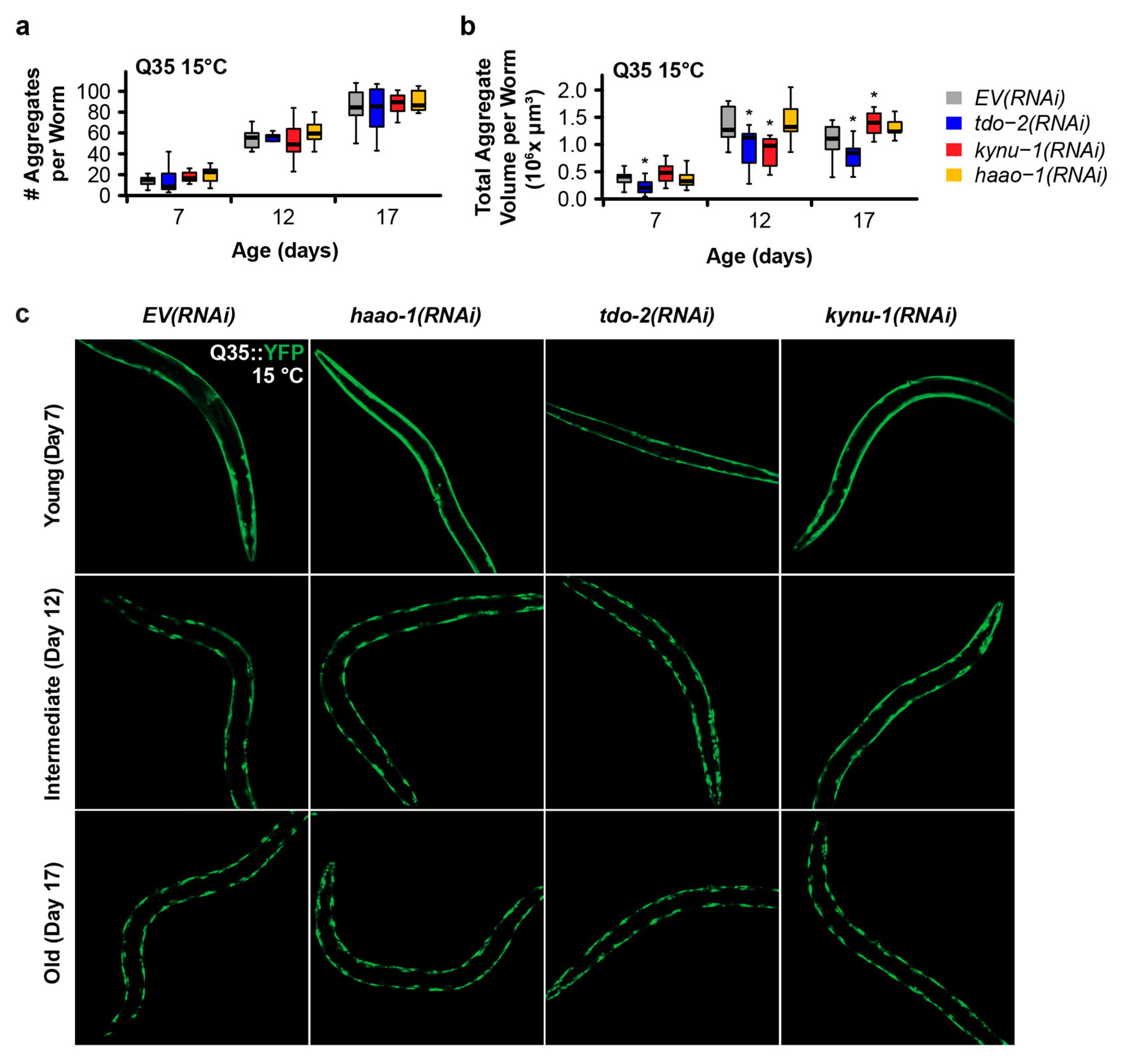

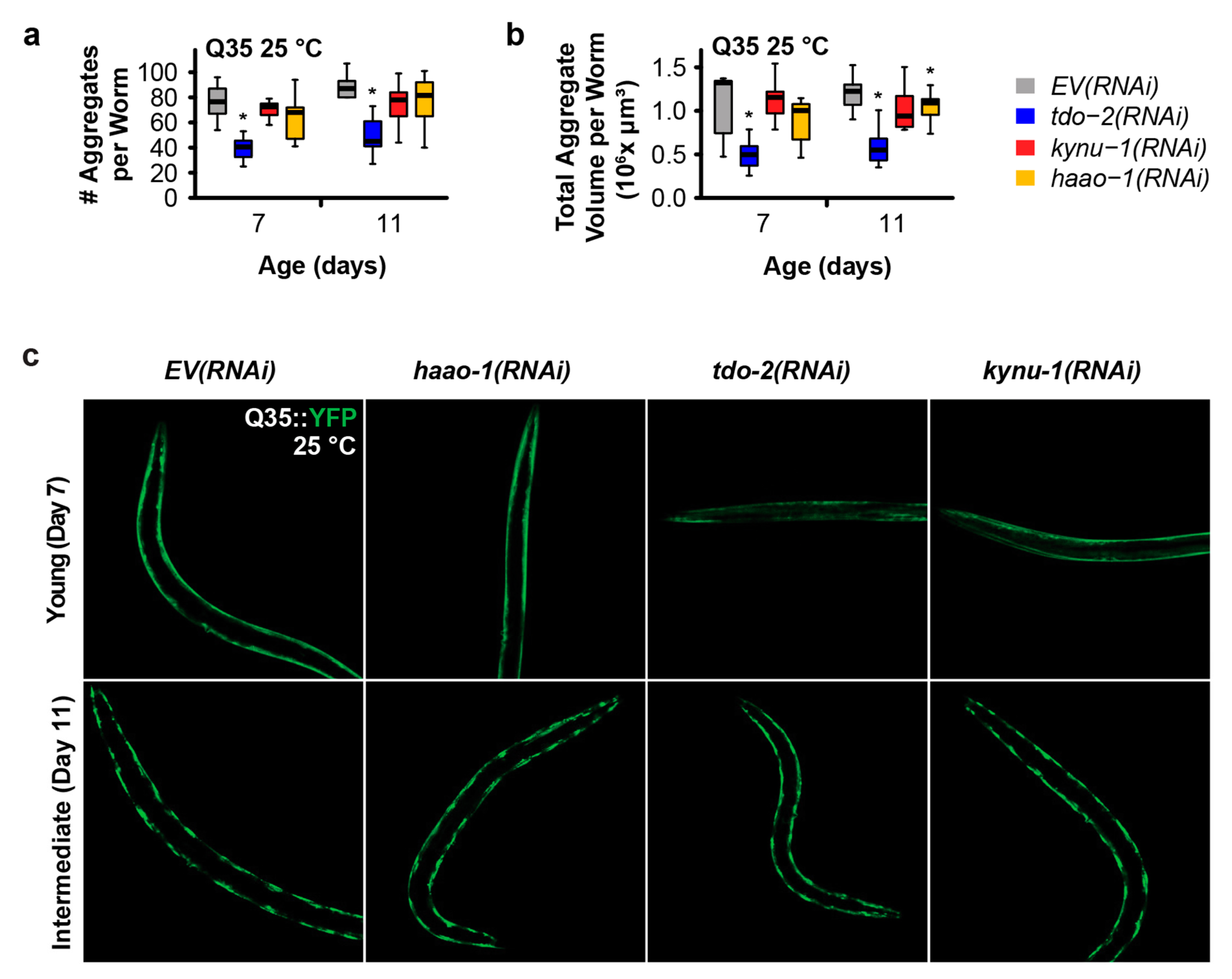

We next investigated whether the mechanism of delayed paralysis in Q35::YFP worms might be a consequence of inhibition of Q35 protein aggregate formation, a hallmark of HD. We used confocal microscopy to quantify the number and size of Q35::YFP aggregates at different ages for worms cultured at a both 15 °C and 25 °C.

haao-1 knockdown did not affect either the number or volume of protein aggregates at either 15 °C (

Figure 2) or 25 °C (

Figure 3), with the exception of a small but significant reduction in aggregate volume at 25 °C in 11-day-old worms (

Figure 3b). This is in contrast to our previously reported observation that

tdo-2(RNAi) can reduce the number of aggregates 25 °C (

Figure 3a) and aggregate volume at both 15 °C (

Figure 2b) and 25 °C (

Figure 3b), and that

kynu-1(RNAi) can reduced mid-life aggregate volume at 15 °C (

Figure 2b) [

20]. This suggests that the protective effects of

haao-1 knockdown against polyglutamine toxicity are independent of protein aggregation.

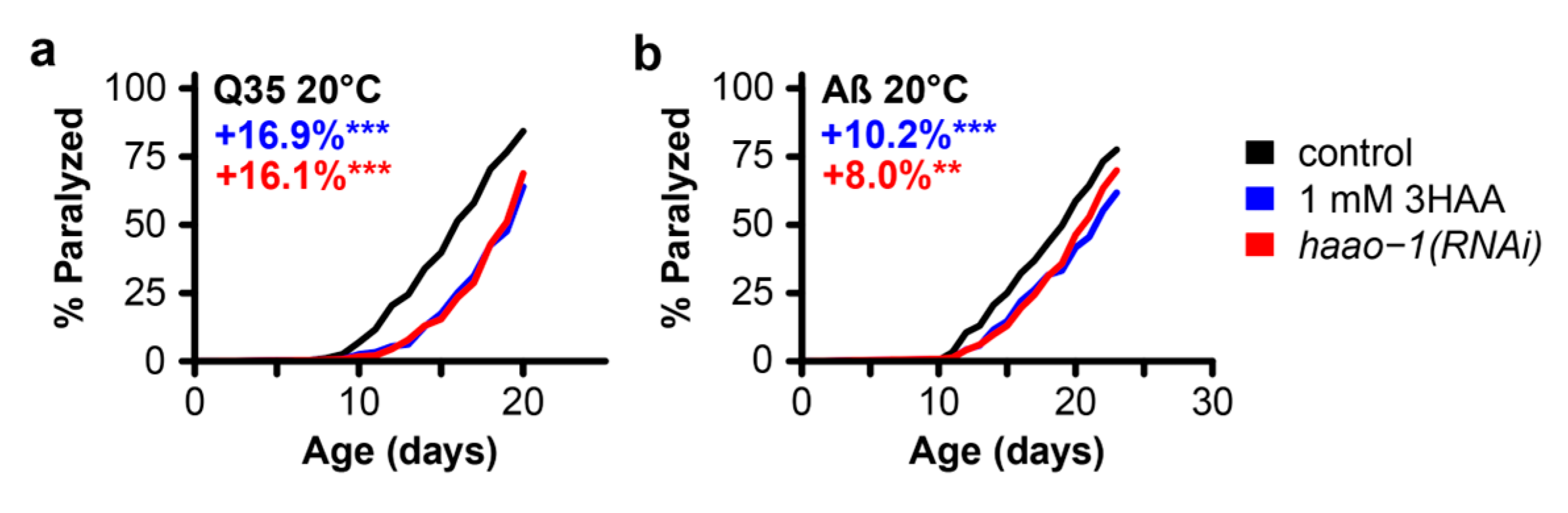

In earlier work, we found that the beneficial effects of

haao-1 knockdown on lifespan are mediated by increased physiological levels of the HAAO substrate metabolite 3HAA (

Figure 1). Animals lacking functional

haao-1 accumulate 3HAA with age and 1 mM 3HAA supplementation in the growth media is sufficient to extend

C. elegans lifespan to a similar degree as knockdown of

haao-1 [

21]. Meek et al. [

25] predicted

in silico that 3HAA should bind human Aβ at a critical region for protein misfolding, and found

in vitro that 3HAA prevented protein Aβ aggregation. To investigate whether 3HAA supplementation can similarly recapitulate the protective effects of

haao-1(RNAi) against proteotoxicity in

C. elegans, we supplemented worms expressing muscle Q35 and Aβ with 1 mM 3HAA. 1 mM 3HAA supplementation delayed age-associated paralysis to a nearly identical degree as experiment-matched worms subjected to

haao-1(RNAi) in both Q35 (

Figure 4a) and Aβ (

Figure 4b) animals. This observation supports a model in which elevated physiological 3HAA mediates the protection against proteotoxicity by

haao-1 disruption.

4. Discussion

Here we describe a small study examining the impact of haao-1 disruption or 3HAA supplementation on improving pathology in C. elegans models of AD- and HD-associated proteotoxicity. We first showed that haao-1 knockdown delayed age-associated paralysis in worms, suggesting that haao-1 disruption may be protective against proteotoxicity in AD and HD. We next investigated the mechanism of delayed paralysis and found that haao-1 knockdown did not meaningfully affect either the number or volume of protein aggregates, suggesting that the protective effect of haao-1 knockdown against polyglutamine or amyloid-beta proteotoxicity in C. elegans muscle is independent of protein aggregation. Finally, we showed that media supplementation with 1 mM 3HAA closely mimicked the benefit of haao-1 knockdown on age-associated paralysis, supporting a model in which protection against proteotoxicity by haao-1 disruption is mediated by elevated physiological 3HAA.

These observations suggest that

haao-1 disruption likely acts to reduce proteotoxicity via a mechanism that is at least partially distinct from both

tdo-2 and

kynu-1 because (1)

haao-1 disruption appears to be acting through 3HAA, which is not elevated by disruption of either

tdo-2 or

kynu-1 [

20,

21] and (2)

haao-1 disruption does not impact Q35::YFP aggregate size or volume, while disruption of both aggregate number or volume in at least one context. This leaves open that possibility that these interventions act via both common mechanisms (such as reducing production downstream metabolites) and distinct mechanisms (with

haao-1 knockdown elevating 3HAA and

tdo-2 and

kynu-1 acting via a separate mechanism). Lifespan extension from disruption of

tdo-2,

kynu-1, and

haao-1 was partially dependent on different combinations of established aging pathways [

20,

21]. Evidence presented by van der Goot et al. [

19] suggests that the protection of

tdo-2 knockdown against pathology in a

C. elegans model of alpha-synuclein proteotoxicity (modeling Parkinson’s disease) may be mediated by elevated physiological levels of tryptophan. These observations provide guidance for future detailed mechanistic studies of the broader mechanisms mediating the protection of kynurenine pathway interventions against proteotoxicity.

The role of 3HAA in neurodegenerative disease has only been explored in a few small studies. Meek et al. [

25] showed

in silico that 3HAA was capable of binding to and preventing misfolding of β-amyloid in an energetically favorable reaction. Other groups have found evidence linking 3HAA to improved prognosis and survival from spinal cord injury [

26,

27] and represses pro-inflammatory signaling and behavior of innate immune cells [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], including both astrocytes and microglia [

34]. Parrott et al. [

35] found that

Haao knockout mice were protected against behavioral despair induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation. Together, these studies suggest that elevating 3HAA may have specific benefits in preventing A

β aggregation in AD and broader benefits in neurodegenerative disease by reducing neuroinflammation.

Quinolinic acid (QA), another metabolite of the kynurenine pathway which is created from 3HAA by HAAO (

Figure 1a), has been described as an endogenous neurotoxin produced in active microglia and implicated in several human neurological diseases, including AD and HD [

36,

37,

38]. Tau, an endogenous microtubule-associated protein whose phosphorylation and subsequent aggregation is considered a pathological hallmark of AD, has been shown to have elevated phosphorylation levels in the presence of QA [

39]. QA has also been proposed to modulate excitotoxic neuronal death in HD [

40]. Combined, this evidence suggests that HAAO disruption may be doubly beneficial for treatment of neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis in both increasing 3HAA and decreasing QA.

In summary, in this study we use C. elegans to investigate the benefits of HAAO disruption in preventing AD- and HD-associated proteotoxicity. We note that, while our results are positive, there are limitations with these proteotoxicity models. First, these models express Q35 or Aβ in body wall muscle instead of neurons, a distinct cellular context from the proteotoxicity that occurs in neurodegenerative disease. Second, C. elegans while C. elegans do have cells that carry out analogous roles to the mammalian innate immune system in mammals and share many conserved immune signaling pathways with mammals, they lack many elements of mammalian immunity, including an analogous adaptive immune system. Third, the Q35 polyglutamine repeat model of HD disease mimics the polyglutamine expansion in the huntingtin gene that causes human HD but does not contain the full huntingtin gene. This limits strong interpretation of these data with respect to the impact of 3HAA and HAAO in human AD and HD. However, this study and the related literature discussed above motivates future detailed mechanistic studies of 3HAA supplementation and HAAO inhibition in worm models of neuronal Aβ and polyglutamine, which have a more subtle pathology than the muscle transgenic strains used in this study, and in preclinical rodent models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Summary statistics for paralysis experiments in C. elegans Alzheimer's (Aβ) and Huntington's (Q35) disease models, Table S2: Summary statistics for Q35::YFP aggregate quantification experiments in C. elegans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. S., R.K., and G.L.S.; methodology, G. B., S.S., and G.L.S.; software, B.T.H., K.M.M., C.C., S.S., and G.L.S.; formal analysis, B.T.H., K.M.M., C.C., S.S., and G.L.S.; investigation, B.T.H., K.M.M., C.C., G.B., S.S., R.K., and G.L.S.; data curation, S.S., R.K., and G.L.S; writing—original draft preparation, B.T.H., K.M.M., and G.L.S.; writing—review and editing, B.T.H., K.M.M., S.S., R.K., and G.L.S; visualization, B.T.H., K.M.M., C.C., S.S., and G.L.S.; supervision, R.K. and G.L.S.; project administration, R.K. and G.L.S.; funding acquisition, R.K. and G.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute on Aging grant AG038070 to The Jackson Laboratory and National Institute on Aging grant R35GM133588 to G.L.S.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

G.L.S. is co-founder, owner, and Managing Members of Senfina Biosystems, LLC. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A

This appendix contains raw data for paralysis, aggregate number, and aggregate volume.

References

- Xu, J.; Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021; CDC: NCHS Data Brief, No. 456, 2022;

- Hipp, M.S.; Kasturi, P.; Hartl, F.U. The Proteostasis Network and Its Decline in Ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 421–435. [CrossRef]

- Labbadia, J.; Morimoto, R.I. The Biology of Proteostasis in Aging and Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 435–464. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.C.; Dillin, A. Aging as an Event of Proteostasis Collapse. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004440. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [CrossRef]

- Bates, G.P.; Dorsey, R.; Gusella, J.F.; Hayden, M.R.; Kay, C.; Leavitt, B.R.; Nance, M.; Ross, C.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Wetzel, R.; et al. Huntington Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2015, 1, 15005. [CrossRef]

- Irvine, G.B.; El-Agnaf, O.M.; Shankar, G.M.; Walsh, D.M. Protein Aggregation in the Brain: The Molecular Basis for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 451–464. [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2021, 7, 33. [CrossRef]

- Masters, C.L.; Simms, G.; Weinman, N.A.; Multhaup, G.; McDonald, B.L.; Beyreuther, K. Amyloid Plaque Core Protein in Alzheimer Disease and Down Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985, 82, 4245–4249. [CrossRef]

- Masters, C.L.; Bateman, R.; Blennow, K.; Rowe, C.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Cummings, J.L. Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2015, 15056. [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, E.; Lurz, R.; Turmaine, M.; Mangiarini, L.; Hollenbach, B.; Hasenbank, R.; Bates, G.P.; Davies, S.W.; Lehrach, H.; Wanker, E.E. Huntingtin-Encoded Polyglutamine Expansions Form Amyloid-like Protein Aggregates in Vitro and in Vivo. Cell 1997, 90, 549–558. [CrossRef]

- Andhale, R.; Shrivastava, D. Huntington’s Disease: A Clinical Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e28484. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-K.; Kuan, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-W.; Hu, C.-J. Clinical Trials of New Drugs for Alzheimer Disease: A 2020–2023 Update. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 83. [CrossRef]

- Wild, E.J.; Tabrizi, S.J. Therapies Targeting DNA and RNA in Huntington’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 837–847. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Portuguez, R.; Sutphin, G.L. Kynurenine Pathway, NAD+ Synthesis, and Mitochondrial Function: Targeting Tryptophan Metabolism to Promote Longevity and Healthspan. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 132, 110841. [CrossRef]

- Link, C.D. Expression of Human Beta-Amyloid Peptide in Transgenic Caenorhabditis Elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995, 92, 9368–9372.

- Morley, J.F.; Brignull, H.R.; Weyers, J.J.; Morimoto, R.I. The Threshold for Polyglutamine-Expansion Protein Aggregation and Cellular Toxicity Is Dynamic and Influenced by Aging in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 10417–10422. [CrossRef]

- van der Goot, A.T.; Zhu, W.; Vazquez-Manrique, R.P.; Seinstra, R.I.; Dettmer, K.; Michels, H.; Farina, F.; Krijnen, J.; Melki, R.; Buijsman, R.C.; et al. Delaying Aging and the Aging-Associated Decline in Protein Homeostasis by Inhibition of Tryptophan Degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 14912–14917. [CrossRef]

- Sutphin, G.L.; Backer, G.; Sheehan, S.; Bean, S.; Corban, C.; Liu, T.; Peters, M.J.; van Meurs, J.B.J.; Murabito, J.M.; Johnson, A.D.; et al. Caenorhabditis Elegans Orthologs of Human Genes Differentially Expressed with Age Are Enriched for Determinants of Longevity. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 672–682. [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Espejo, L.; Backer, G.; Freitas, S.; Spence, E.; Meyers, J.; Shuck, K.; Gardea, E.A.; Chang, L.M.; et al. On the Benefits of the Tryptophan Metabolite 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid in Caenorhabditis Elegans and Mouse Aging. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8338. [CrossRef]

- Sutphin, G.L.; Kaeberlein, M. Measuring Caenorhabditis Elegans Life Span on Solid Media. JoVE J. Vis. Exp. 2009, e1152. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.G.; Kamath, R.S.; Zipperlen, P.; Martinez-Campos, M.; Sohrmann, M.; Ahringer, J. Functional Genomic Analysis of C. Elegans Chromosome I by Systematic RNA Interference. Nature 2000, 408, 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, R.S.; Fraser, A.G.; Dong, Y.; Poulin, G.; Durbin, R.; Gotta, M.; Kanapin, A.; Le Bot, N.; Moreno, S.; Sohrmann, M.; et al. Systematic Functional Analysis of the Caenorhabditis Elegans Genome Using RNAi. Nature 2003, 421, 231–237. [CrossRef]

- Meek, A.; Simms, G.; Weaver, D. Searching for an Endogenous Anti-Alzheimer Molecule: Identifying Small Molecules in the Brain That Slow Alzheimer Disease Progression by Inhibition of β-Amyloid Aggregation. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013, 38, 269–275. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.R.; Lovejoy, D.B. Inhibiting the Kynurenine Pathway in Spinal Cord Injury: Multiple Therapeutic Potentials? Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 2073–2076. [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.R.; Gay, E.A.; Heyes, M.P.; Blight, A.R. Effects of Methylprednisolone and 4-Chloro-3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid in Experimental Spinal Cord Injury in the Guinea Pig Appear to Be Mediated by Different and Potentially Complementary Mechanisms. Spinal Cord 2014, 52, 662–666. [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.; Stenuit, B.; Ho, J.; Wang, A.; Parke, C.; Knight, M.; Alvarez-Cohen, L.; Shapira, M. Assembly of the Caenorhabditis Elegans Gut Microbiota from Diverse Soil Microbial Environments. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1998–2009. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ovchinnikova, O.; Jönsson, A.; Lundberg, A.M.; Berg, M.; Hansson, G.K.; Ketelhuth, D.F.J. The Tryptophan Metabolite 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Lowers Plasma Lipids and Decreases Atherosclerosis in Hypercholesterolaemic Mice. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2025–2034. [CrossRef]

- Fallarino, F.; Grohmann, U.; Vacca, C.; Bianchi, R.; Orabona, C.; Spreca, A.; Fioretti, M.C.; Puccetti, P. T Cell Apoptosis by Tryptophan Catabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2002, 9, 1069–1077. [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Saito, K.; Takemura, M.; Maekawa, N.; Fujigaki, S.; Fujii, H.; Wada, H.; Takeuchi, S.; Noma, A.; Seishima, M. 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid, an L-Tryptophan Metabolite, Induces Apoptosis in Monocyte-Derived Cells Stimulated by Interferon-Gamma. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 38, 242–251. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S.; Lee, S.-M.; Kim, M.-K.; Park, S.-G.; Choi, I.-W.; Choi, I.; Joo, Y.-D.; Park, S.-J.; Kang, S.-W.; Seo, S.-K. The Tryptophan Metabolite 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Suppresses T Cell Responses by Inhibiting Dendritic Cell Activation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013, 17, 721–726. [CrossRef]

- Gargaro, M.; Vacca, C.; Massari, S.; Scalisi, G.; Manni, G.; Mondanelli, G.; Mazza, E.M.C.; Bicciato, S.; Pallotta, M.T.; Orabona, C.; et al. Engagement of Nuclear Coactivator 7 by 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Enhances Activation of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Immunoregulatory Dendritic Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1973. [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.; Suh, H.-S.; Tarassishin, L.; Cui, Q.L.; Durafourt, B.A.; Choi, N.; Bauman, A.; Cosenza-Nashat, M.; Antel, J.P.; Zhao, M.-L.; et al. The Tryptophan Metabolite 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Plays Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Roles During Inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 1360–1372. [CrossRef]

- Parrott, J.M.; Redus, L.; Santana-Coelho, D.; Morales, J.; Gao, X.; O’Connor, J.C. Neurotoxic Kynurenine Metabolism Is Increased in the Dorsal Hippocampus and Drives Distinct Depressive Behaviors during Inflammation. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e918. [CrossRef]

- Espey, M.G.; Chernyshev, O.N.; Reinhard, J.F.; Namboodiri, M.A.; Colton, C.A. Activated Human Microglia Produce the Excitotoxin Quinolinic Acid. Neuroreport 1997, 8, 431–434. [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J.; Noonan, C.E.; Takikawa, O.; Cullen, K.M. Indoleamine 2,3 Dioxygenase and Quinolinic Acid Immunoreactivity in Alzheimer’s Disease Hippocampus. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2005, 31, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón, R.; Ugalde Muñiz, P.; Pineda, B.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Ríos, C.; Pérez-de la Cruz, V. Quinolinic Acid: An Endogenous Neurotoxin with Multiple Targets. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 104024. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Ting, K.; Cullen, K.M.; Braidy, N.; Brew, B.J.; Guillemin, G.J. The Excitotoxin Quinolinic Acid Induces Tau Phosphorylation in Human Neurons. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6344. [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, P.; Luthi-Carter, R.E.; Augood, S.J.; Schwarcz, R. Neostriatal and Cortical Quinolinate Levels Are Increased in Early Grade Huntington’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 17, 455–461. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).