2. Introduction

This study examines the consequences the demographic changes occurring in Israeli society which cause to personnel shortage which has been plaguing Israeli hospitals and to increasing congestion and overload in in-patient wards in general and in delivery rooms and maternity wards in particular.

The consistent and continuous growth of the global population is creating many challenges for policy makers in various areas of life, such as housing; [

26], transportation [

22], education and higher education [

64]; [

36], health [

30]; [

21], and others. This reality requires decision makers in the various countries to seek and find technological and regulatory solutions for dealing with its different consequences [

24]; [

33]. Israel too is dealing with the implications of the population growth, which is even more prominent than in other developed countries [

61]; [

67].

The increase in Israel’s population stems from three main factors: First, a high immigration rate of Jews from other countries to Israel, usually for ideological and Zionist reasons [

20]. Second, a rise in life expectancy, deriving (among others) from the development and improvement of healthcare services [

19]. Third, relatively high marriage, childbirth, and fertility rates for religious, cultural, and traditional reasons [

66]; [

51]; [

68]. Israel is a pro-natalist country, where both Jewish and Arab women bear many of the consequences of the social imperative to have children. This social imperative, which is connected to militarism, patriarchy, and cultural values, heavily shapes and influences Jewish and Arab women’s access to contraception and abortion, as well as other reproductive healthcare services. These facts can clarify why reducing the demand for childbirth services is not an option in Israel, at least not in the near future [

25].

This reality is challenging policy makers in Israel, who must find solutions for the growing congestion on the roads [

14], the increasing shortage of nursing care workers for the elderly [

13], creating sources of employment for new immigrants [

23](, the growing congestion in the hospitals, the worsening shortage of medical staff ; [

1], and so on, as set out below.

2.1. The Shortage of Personnel in Israeli Hospitals

Israelis enjoy, as stated, a higher life expectancy than the average in developed countries. Infant mortality in Israel is fairly low and the number of children for each woman in the fertility age is the highest of all OECD countries, almost double the average in these countries (Source: OECD Family Database, Fertility indicators, SF2.1 Fertility rate:

https://www.oecd.org/social/database.htm) At the same time, Israelis must contend with a healthcare system that is lagging behind with regard to resources, infrastructure, and personnel, compared to OECD countries. The imbalance between the demand for medical services and the supply in the Israeli healthcare system has not gone unnoticed by the heads of the World Health Organization, which presented its report on the Israeli healthcare system at the organization's regional conference (European Region) held in Tel Aviv in September 2022. According the report’s findings, Israel has only about three doctors for every one thousand people, there are not enough midwives, there is a considerable shortage of nurses, and the number of medical graduates is among the lowest in the world .

In addition, the report indicated that the number of medical staff, the obstetricians, and psychologists in Israel is lower than the European average for the same number of people. This information corresponds with what is known and felt in Israel: an extremely congested healthcare system, where the average age of physicians is on the rise and the supply of medical services is failing to keep up with the demand for physicians. That and more, in the absolute majority of OECD countries (Aside from Italy, where the number of hospital employees is lower than in Israel.) the number of hospital employees is higher than in Israel. This fact may have a detrimental effect on the level of administrative and medical services provided to Israeli citizens (see

Table 3- Hospital Employment- Density per 1,000 Population, in the appendix).

The proportion of physicians in Israeli society is fairly low, both in absolute terms and relative to OECD countries. As a result, Israeli policy makers have expressed serious concerns with regard to the ability of the local healthcare system to meet the increasing demand for medical services [

31]. Indeed, in recent years there has been a certain rise in the proportion of physicians in Israel, mainly as a result of the increasing flow of physicians from abroad (The flow of physicians in Israel comes from three main sources: graduates of medical studies in Israel, Israelis who studied medicine abroad, and immigrants). In addition, the situation in Israel is outstanding relative to the rest of the world also due to the fact that it trains less than 40% of its physicians internally. This is the lowest rate of all developed countries [

42]. (see

Table 4 - Employed Doctors - Density per 1,000 Population, in the appendix). Moreover, the shortage of physicians is expected to increase considerably in the coming decade due to the upcoming retirement of many health care professionals who immigrated to Israel from the former Soviet Union in the large immigration waves of the 1990s.

Similarly, the rate of nursing personnel in Israel is also very low and for years has remained between 4 and 5 employees per one thousand people, about one half the average in other OECD countries [

1]. Indeed, the forecast is for a gradual rise in this rate following the increase in facilities for nursing studies in Israel, among other things due to the expansion of authority, the increase in areas of responsibility, and the more advanced professional training of nursing graduates in Israel in recent years [

47]. At the same time, the growth rate is expected to be slow and insufficient to meet the needs (See

Table 5 - Hospital Professional Nursing Workers- in the appendix).

2.2. Congestion in Israeli Hospitals

The congestion in Israeli hospitals did not appear out of thin air, as it is the result of the short-sighted public policy of the Israeli Ministry of Health and the lack of coordination between this ministry and the Ministry of Construction and Housing, which promotes residential projects in various cities in Israel. This regulatory failure allowed (and is continuing to allow) the heads of local authorities to approve many residential projects (that will increase the number of residents( directly versus the Ministry of Housing without coordinating with the Ministry of Health. This policy is enabling the population in Israeli city centers to increase without supplying any additional resources for local hospitals (medical equipment, personnel, hospital beds, etc.) which are needed in order to provide appropriate medical services to the local population, as detailed below.

The high life expectancy in Israel and the population increase are placing a load on the Israeli healthcare system. This load is manifested in lengthening waits for consultations with medical and paramedical specialists and for surgery. Nevertheless, these trends have not managed to generate a significant and efficient increase in budgetary resources for the hospitals, in favor of their expansion and increased capacity so that they can be adaptted to the increase in the Israeli population’s medical needs. As a result, Israel’s healthcare system has been dealing with a growing shortage of hospital beds in recent decades. Indeed, community services and the shortening of hospital stays have helped alleviate this problem, but the hospitals are still suffering from overload and high levels of congestion, as well as a significant shortage of hospital beds [

41].

The Israeli hospitals currently have less than 3 hospital beds for every thousand people. Moreover, the number of hospital beds relative to the population has diminished in recent years, indicating increased congestion in the hospitals. At the same time, compared to the various OECD countries, it is evident that aside from several countries that are particularly efficient in this respect (such as Austria and Germany), this problem is shared by other countries such as the United States, Britain, Spain, and even Denmark (known for its fairly well-developed welfare policy and civil services). (See

Table 6 - Hospital beds per 1,000 population, in the appendix).

2.3. The Effect of the Shortage of Personnel and the Crowding in Israeli Hospitals on the Service Provided in Urgent Care Departments

The scarcity of medical and administrative personnel and the shortage of hospital beds in the various inpatient departments in Israel, as presented above, are manifested in a fairly lengthy patient stay in urgent care departments, as the shortage of beds in the various departments and the low availability of medical staff might delay patient discharge from the urgent care department (emergency room) and transfer to relevant internal care departments for further treatment. Although there is at present no accessible official data on the time spent at urgent care departments in Israel, it is possible to examine the data published by the Ministry of Health in 2016 [

45], as presented in the following table.

As evident from the table above, in 2016 the average time spent by patients in urgent care departments in Israel reached up to about four and a half hours. This can attest to the high congestion and lack of medical personnel in hospitals in that year. Indeed, since these data were published there seems to have been a certain improvement in waiting times at emergency rooms, as evident from subsequent surveys conducted by the Ministry of Health (Since 2016 the Ministry of Health has been publishing data from the survey on patient experience in urgent care departments, including data on waiting times as perceived by the patient but not official and objective waiting times reported by the Ministry of Health). In the last few years the ministry has conducted an annual survey examining the patient experience in urgent care departments. Surveys from recent years (2017-2020) indicate, as stated, a slight improvement in patient experience as regards the physical conditions in the urgent medicine department, the care continuum, provision of information and explanations by the professional staff, perceived attitude to and respect for the patient, and waiting times as perceived by the patient [

44].

In addition, in 2020 the Ministry of Health published measurements of response times by medical staff in emergency rooms in general and in cases of suspected stroke in particular, which also indicate an improvement [

43]. At the same time, it is notable that the only indices publicized on this topic were selected based on a parameter called “measurement feasibility”, meaning indices that are measurable and capable of showing that the process examined is indeed occurring, and therefore these indices are fairly limited, (See

Table 7 in the appendix).

Moreover, the data of the Ministry of Health for 2013-2020 attest to a constant improvement in hospitals’ national achievements with regard to meeting service goals [

43]. At the same time these data, which attest as stated to an improvement in waiting times and treatment provided in urgent care departments and in meeting the professional goals of the Ministry of Health for hospitals, do not refute the claim concerning increasing congestion in the hospitals and the growing shortage of personnel, as well as the implications of these for the quality of service and care. These trends are supported by the State Comptroller’s report for 2019, which indicates a shortage of medical personnel and a lack of hospital beds, sharply criticizes the hospitals for the continuous delay in providing a response to these problems,and sets timetables for resolving them [

65].

The abovementioned data attesting to a gradual improvement in waiting times as perceived by patients indicates that the Ministry of Health is aware of the shortages in the hospitals and concerned of the compromised quality of service due to the limited resources, and is therefore setting measurable quantitative service goals obligating all hospitals in Israel, as well as performing periodical service surveys to verify that these goals are indeed met.

2.4. Congestion in the Hospitals as Reflected in the Research Literature

Many studies have addressed the congestion in hospital wards around the world and their impact on the level of pressure on medical staff [

10], the performance of physicians in particular and of the hospital system in general [

27], service time and patient safety [

35], and the mortality rate in hospitals . Other studies presented models for regulating existing appointments and congestion in the hospitals ; [

18], while yet others proposed applied models capable of preventing the emergence of congestion in hospitals to begin with [

52]; [

63]. Then again, a fairly small number of studies focused on congestion in hospital maternity wards and its various effects on features of the childbirth process [

3].

Therefore, the contribution of this article stems from the fact that aside from focusing on congestion in delivery rooms and maternity wards in Israel and thus adding to the limited research literature on this specific topic, it also seeks to examine different alternatives for effective public policy aimed at reducing this congestion. Its findings present the data on fertility and childbirth in Israel in the recent decade, which have led to increased congestion in delivery rooms and maternity wards in local hospitals. And as mentioned, several possible alternatives for designing and implementing public policy to regulate this congestion are proposed, spelling out the benefits and risks of each. In light of the findings, the research conclusions present recommendations for designing an efficient public policy to regulate the congestion in Israeli delivery rooms, with the aim of preventing its future increase, which in an extreme case might result in loss of human life.

4. Findings

The research findings will begin by presenting the high fertility and delivery indicators in Israel, which constitute a significant cause of the congestion in hospital delivery rooms and maternity wards.

4.1. Birth and Fertility Trends in Israel

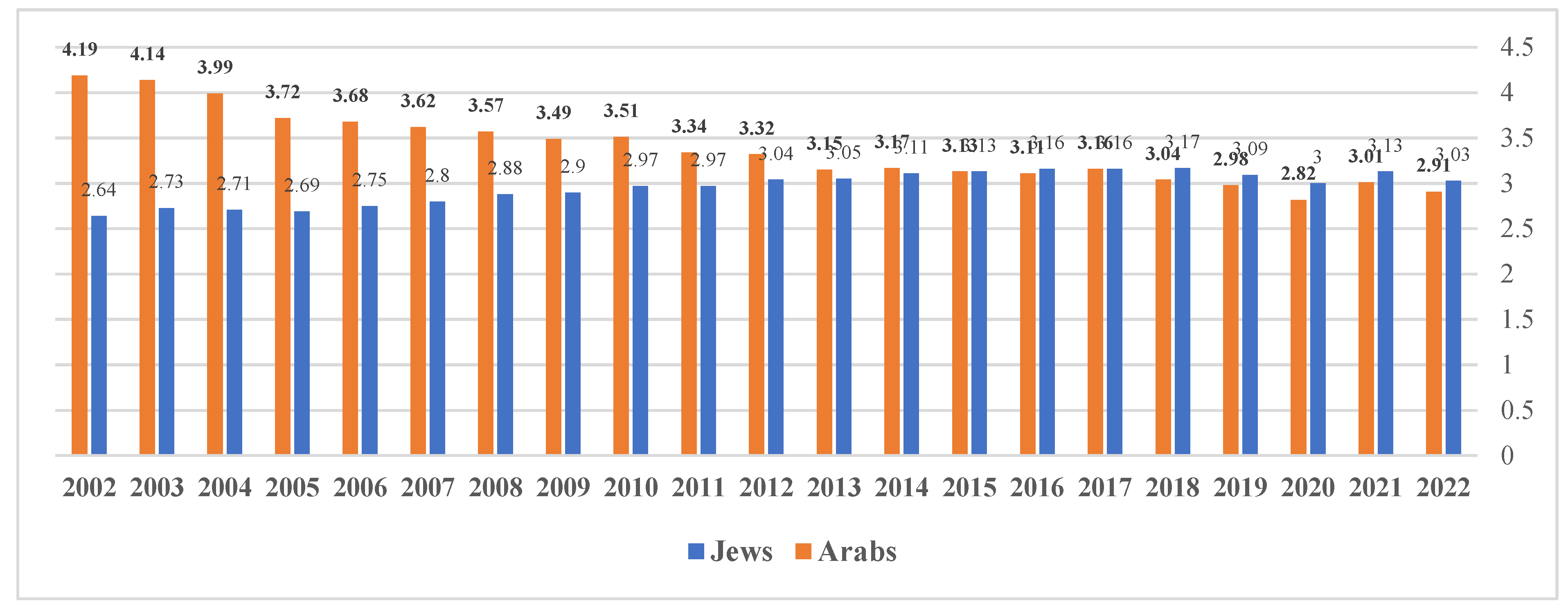

Cultural values in all sectors of the heterogeneous Israeli society (Jews and Arabs, secular and religious, etc.) encourage childbirth for various reasons (religion and tradition, financial support, social expectations, social status, etc.). Accordingly, Israel’s public policy supports these values and helps couples who have difficulty becoming pregnant by funding fertilization procedures and increasing fertility on one hand, and providing childbirth grants and child benefits on the other. The research findings show that since the beginning of the current millennium a drop is evident in the fertility rate in Israel’s Arab sector but there is a rise among women in the Jewish sector, as evident from the following figure.

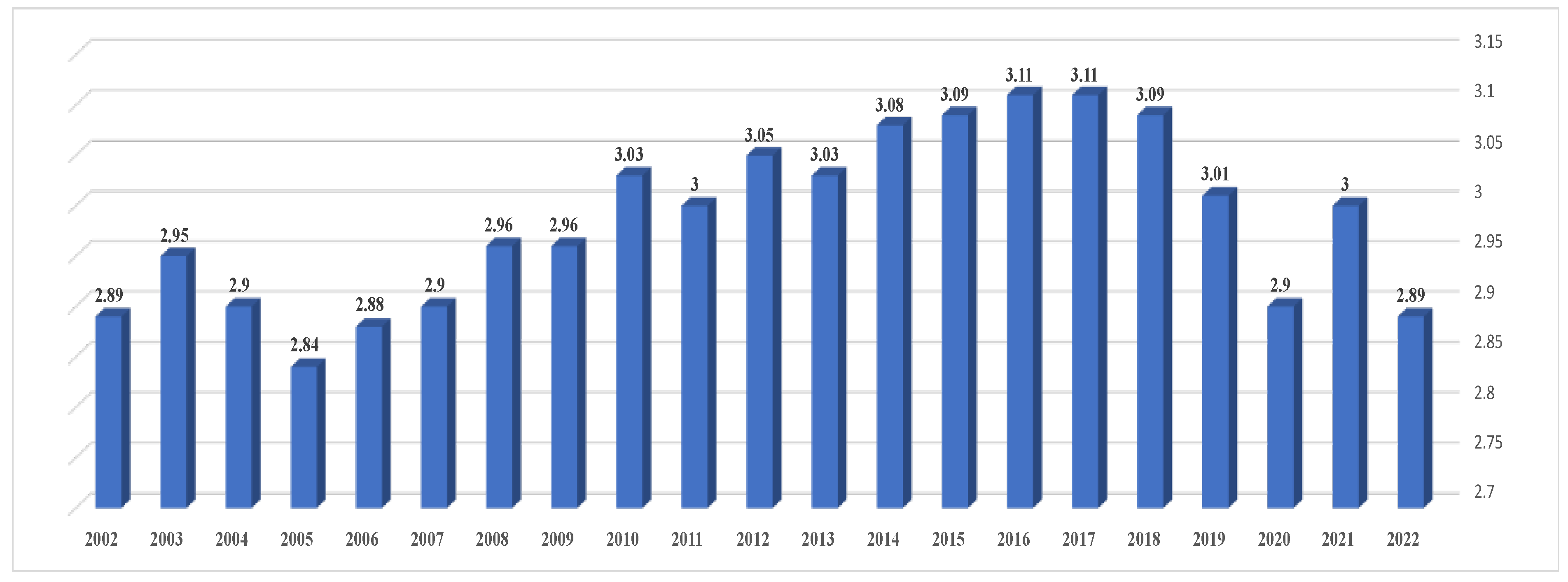

Despite the different trends of the fertility rate in the Jewish and Arab sectors in Israel, the average total fertility rate in Israel still seems to be on the rise in recent years, as shown in the figure below. Indeed, in 2019 and 2020 a drop was registered in this indicator but Israel’s fertility rate is still double the average in OECD countries (Which in 2019 was only 1.61, Source: OECD Family Database). The drop at 2020 is explained as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, which generated a sense of uncertainty and concern among many couples, who avoided pregnancy during this period due to the question marks surrounding the safety of the pregnancy, the fetus, and the mother in case of contracting the virus or being vaccinated against it [

8].

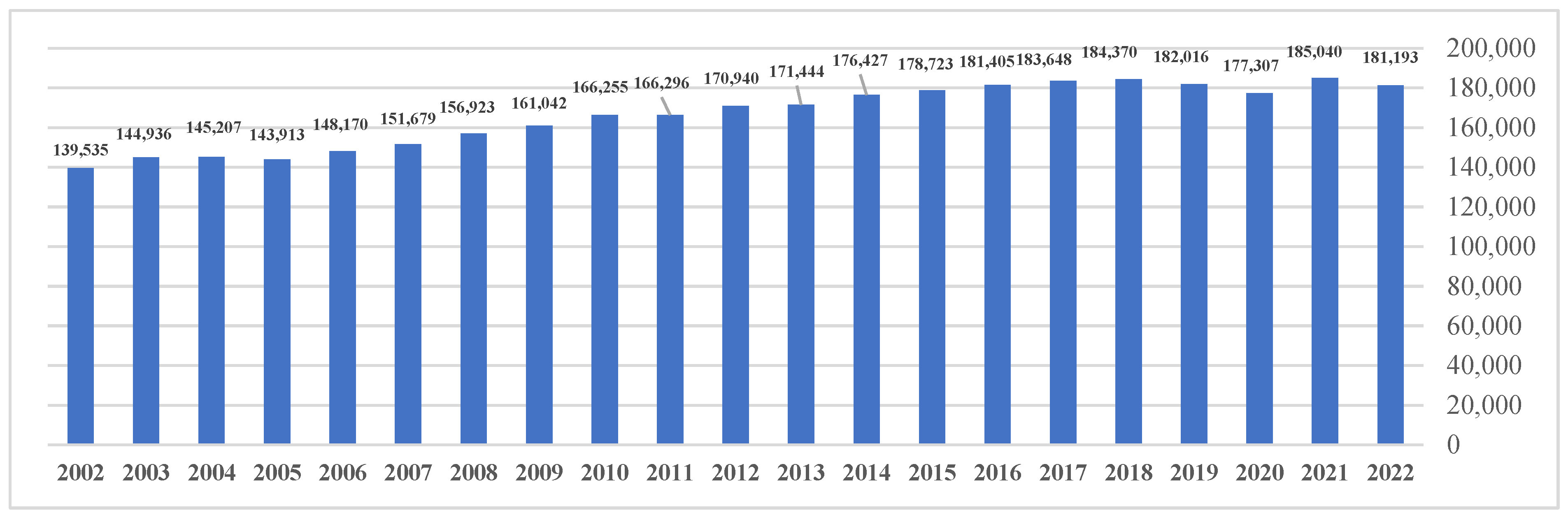

The rise in the total fertility rate (Jews and Arabs) in Israel in recent years is manifested in an increase in the number of births in this country, as shown in the following figure.

The birth rate in Israel, presented in the figure above, indicates a similar trend as the fertility rate (shown in the previous figure): The number of births in Israel shows an increasing trend since the early 2000s and has reached more than 180 thousand births (per year) in recent years. At the same time, the findings show a drop in the number of births in Israel in 2019 and 2020. However, the decreasing trend in the birth rate during these two years is also evident in other countries and can be associated with the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic [

39].

4.2. The Congestion in Maternity Wards in Israeli Hospitals

One customary indicator for examining the ability of the hospital system to meet the current needs of the population is bed occupancy. The data of the Israeli Ministry of Health indicates a high occupancy rate in Israeli hospitals (over 90% occupancy Rate in most in-patient hospital wards), placing Israel at the top of all OECD countries on this indicator (the data of the Ministry of Health are available in the following link:

https://www.gov.il/he/departments/publications/reports/hospital-beds). The following table lists the bed occupancy rate in Israel both in general and in several selected departments, during 2010-2020.

Table 2.

Bed Occupancy Rate in Israel (By Department) at Years 2010-2022 (By Percentage).

Table 2.

Bed Occupancy Rate in Israel (By Department) at Years 2010-2022 (By Percentage).

| 2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

|

| 86.7 |

85.6 |

84.0 |

89.8 |

90.9 |

92.6 |

93.2 |

93.7 |

92.8 |

94.1 |

94.5 |

94.0 |

95.0 |

General care - Total |

| 88.6 |

85.9 |

79.2 |

97.0 |

97.0 |

98.9 |

98.9 |

99.1 |

98.2 |

101.1 |

101.9 |

99.7 |

98.9 |

Internal medicine |

| 76.4 |

76.3 |

74.7 |

82.0 |

87.5 |

90.0 |

80.0 |

84.8 |

88.1 |

93.7 |

95.2 |

95.3 |

100.1 |

Oncology |

| 91.7 |

82.7 |

80.9 |

89.6 |

89.8 |

85.2 |

89.9 |

88.2 |

89.2 |

88.7 |

100.1 |

93.8 |

95.0 |

Cardiothoracic surgery |

| 97.4 |

99.5 |

95.9 |

101.4 |

102.5 |

95.3 |

99.2 |

101.4 |

110.9 |

110.6 |

99.4 |

105.4 |

107.6 |

Rehabilitation |

| 93.4 |

94.1 |

85.0 |

97.2 |

99.1 |

97.2 |

96.2 |

98.2 |

98.8 |

102.5 |

105.0 |

105.0 |

102.9 |

Gynecology |

| 91.8 |

84.8 |

85.3 |

97.1 |

101.7 |

100.9 |

103.5 |

101.0 |

99.4 |

97.8 |

103.0 |

106.0 |

110.9 |

Obstetrics |

Table 3.

Hospital Employments- Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2022 (Head Counts).

Table 3.

Hospital Employments- Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2022 (Head Counts).

| 2022 |

2021

|

2020

|

2019

|

2018

|

2017

|

2016

|

2015

|

2014

|

2013

|

2012

|

2011

|

2010

|

|

| N.A |

13.7 |

13.78

|

13.69

|

13.42

|

13.41

|

13.29

|

13.29

|

13.27

|

13.11

|

13.05

|

12.9

|

12.7

|

Austria |

| N.A |

17.78 |

17.54

|

17.11

|

16.57

|

16.48

|

16.26

|

16.1

|

16.04

|

15.98

|

15.75

|

15.56

|

15.09

|

Germany |

| N.A |

22.7

|

21.17

|

20.63

|

20.59 |

20.6

|

20.59

|

20.79

|

21.03

|

20.89

|

20.46

|

20.45

|

20.78

|

Denmark |

| N.A |

N.A |

11.01 |

10.72

|

10.52

|

10.34

|

10.34

|

10.29

|

10.37

|

10.62

|

10.73

|

10.95

|

11.08

|

Italy |

| 11.71 |

11.53

|

11.31

|

10.3

|

11.11

|

10.9

|

10.62

|

10.69

|

11.22

|

10.89

|

11.34

|

11.34

|

11.73

|

Israel |

| N.A |

14.18 |

13.58 |

12.78 |

12.59 |

12.27 |

11.95 |

11.76

|

11.58

|

11.3

|

11.33

|

11.56

|

11.71

|

Spain |

| N.A |

24.66 |

23.5 |

23.11

|

22.48

|

22.16

|

22.19

|

21.92

|

21.68

|

21.48

|

21.43

|

22.27

|

23.03

|

United Kingdom |

| N.A |

21.25 |

21.19 |

21.36 |

21.15

|

21.02

|

20.13

|

19.65

|

19.51

|

19.57

|

19.59

|

19.50

|

19.57

|

United States |

Table 4.

Employed Doctors - Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2021.

Table 4.

Employed Doctors - Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2021.

| 2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

|

| 3.19 |

3.38 |

3.29 |

3.22 |

3.14 |

3.08 |

3.07 |

2.98 |

2.94 |

2.97 |

3.00 |

3.01 |

Israel |

| 3.5 |

3.5 |

3.56 |

3.50 |

3.44 |

3.35 |

3.32 |

3.25 |

3.23 |

3.15 |

3.19 |

3.12 |

Average OECD |

Table 5.

Hospital Professional Nursing Workers – Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2022 (Head Counts).

Table 5.

Hospital Professional Nursing Workers – Density per 1,000 Population, at Years 2010-2022 (Head Counts).

| 2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

|

| N.A |

10.79 |

10.32 |

10.29 |

6.85 |

6.85 |

6.77 |

6.8 |

6.79 |

6.69 |

6.75 |

6.62 |

6.53 |

Austria |

| N.A |

12.03 |

12.06 |

11.78 |

11.52 |

11.05 |

10.84 |

10.71 |

10.69 |

10.52 |

10.17 |

10.13 |

9.84 |

Germany |

| N.A |

N.A |

10.24 |

10.13 |

10.1 |

10.03 |

9.95 |

9.92 |

9.93 |

9.95 |

9.96 |

9.87 |

9.82 |

Denmark |

| N.A |

6.21 |

6.28 |

6.16 |

5.74 |

5.8 |

5.57 |

5.44 |

5.28 |

5.08 |

5.11 |

5.2 |

5.23 |

Italy |

| N.A |

5.09 |

4.87 |

4.72 |

4.64 |

4.63 |

4.48 |

4.32 |

4.3 |

4.32 |

4.25 |

4.17 |

4.04 |

Israel |

| N.A |

6.34 |

6.1 |

5.89 |

5.87 |

5.74 |

5.51 |

5.29 |

5.15 |

5.14 |

5.24 |

5.22 |

5.15 |

Spain |

| 6.91 |

6.94 |

6.78 |

66.1 |

6.5 |

6.41 |

6.45 |

6.45 |

6.46 |

6.44 |

6.42 |

6.59 |

6.68 |

United Kingdom |

Table 6.

Hospital Beds at Years 2010-2022 (per 1,000 Population).

Table 6.

Hospital Beds at Years 2010-2022 (per 1,000 Population).

| 2022 |

2021 |

2020

|

2019

|

2018

|

2017

|

2016

|

2015

|

2014

|

2013

|

2012

|

2011

|

2010

|

|

| N.A |

6.91 |

7.05 |

7.19

|

7.27

|

7.37

|

7.42

|

7.54

|

7.58

|

7.64

|

7.67

|

7.68

|

7.65

|

Austria |

| N.A |

7.76 |

7.82 |

7.91

|

7.98

|

8.00

|

8.06

|

8.13

|

8.23

|

8.29

|

8.34

|

8.38

|

8.25

|

Germany |

| N.A |

2.52 |

2.59 |

2.59

|

2.61

|

2.61

|

2.6

|

2.53

|

2.69

|

3.07

|

N.A |

3.13

|

3.05

|

Denmark |

| N.A |

3.12 |

3.19 |

3.16

|

3.14

|

3.18

|

3.17

|

3.2

|

3.21

|

3.31

|

3.42

|

3.52

|

3.64

|

Italy |

| 2.99 |

2.91 |

2.92 |

2.96

|

2.96

|

3.00

|

2.97

|

3.00

|

3.05

|

3.07

|

3.07

|

3.11

|

3.13

|

Israel |

| N.A |

2.96 |

2.96 |

2.95

|

2.97

|

2.97

|

2.97

|

2.98

|

2.97

|

2.96

|

2.99

|

3.05

|

3.11

|

Spain |

| 2.44 |

2.42 |

2.43 |

2.45

|

2.5

|

2.54

|

2.57

|

2.61

|

2.73

|

2.76

|

2.81

|

2.88

|

2.93

|

United Kingdom |

| N.A |

2.77 |

2.78 |

2.8 |

2.83

|

2.87

|

2.77

|

2.8

|

2.83

|

2.89

|

2.93

|

2.97

|

3.05

|

United States |

Table 7.

Quality Indices in Hospitals in Israel: Duration of Treatment (In Minutes).

Table 7.

Quality Indices in Hospitals in Israel: Duration of Treatment (In Minutes).

| 2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

|

| 27 |

28 |

29 |

33 |

38 |

55 |

Median time from Hospital admission to performing MRI / CT head. |

| 9 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

N.A |

N.A |

Median time from arrival at the emergency room to clinical examination. |

The data in the table indicate a fairly high occupancy rate in all in-patient departments in Israeli hospitals during the period under examination, aside from 2020 when the occupancy seems to have dropped, probably due to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, which postponed and shortened hospital stays throughout the world due to the concern of contracting the virus [

2]. Examination of the occupancy rate in the gynecology and obstetrics departments indicates a very high occupancy of hospital beds, both in absolute terms and relative to other departments (Aside from the rehabilitation department, where the occupancy of hospital beds was found to be relatively high as well). One explanation for this bottleneck in supply may be related to the lobbying by hospitals to prevent out-of-hospital birth procedures (as mentioned later in the article). This policy focuses on considerations of financial gain for the hospital and may sometimes come at the expense of public good.

4.3. The Justification for Designing Public Policy to Regulate the Congestion in Delivery Rooms and Maternity Wards in Israel

The sociodemographic characteristics of Israel on one hand, and the indicators for hospital personnel and department infrastructure on the other (as presented above) underlie, as stated, the choice of Israel as a case study in the current study. The choice to focus specifically on maternity wards and delivery rooms stems from the following reasons: First, unlike the other hospital departments where the hospital bed occupancy rate reflects the demand for medical services associated with illnesses and injuries, the bed occupancy in maternity wards (which derives from the level of activity in the delivery rooms) reflects the level of demand for pregnancy and childbirth, considered a natural, healthy, and even desirable process in any society and all the more so in Israeli society that encourages fertility and childbirth processes.

Second, the congestion in the various departments can be regulated by increasing the supply of hospital beds, as well as by decreasing the demand for their services. Decreasing the demand can be achieved by developing and improving medications for treating and preventing various illnesses and by improving technological processes that allow monitoring the patient’s condition and conducting independent tests and even remote medical consultations with no need to present at the hospital. This is not true of the demand for medical services associated with pregnancy and childbirth, which at the moment require physical presence at the medical facility, in concern for the fetus and mother’s health.

Third, the bed occupancy rate in maternity wards is relatively high compared to that evident in other hospital departments (and shown in

Table 5) and therefore it seems to require giving high priority to its regulation relative to the congestion issue in other hospital departments. Therefore, this study examines the justification for designing a public policy to regulate the congestion in delivery rooms and maternity and gynecology wards in Israeli hospitals.

4.3. Examination of Alternative Proposals for Public Policy Aimed at Regulating the Congestion in Delivery Rooms and Maternity Wards

The research literature on issues related to the congestion in hospital delivery rooms and maternity wards presents several possible ways of addressing the topic, such as attracting international medical graduates to increase the number of obstetric health care providers [

59], improving the infrastructure, or expanding the capacity of the existing hospitals [

52], investing in new technology [

58], and even transferring patients from congested to less congested wards . However, it seems that the possibility of implementing these alternatives in Israel is quite limited.

The low number of doctors and professional nursing workers employed in hospitals (as measured per 1,000 population) is mainly caused by a from a limited number of jobs that is related both to budget constraints and primarily to a lack of training and specialization placements for those studying these fields. Thus, improving the infrastructure or investing in new technologies will not contribute significantly to expanding the capacity at the existing hospitals. Moreover, the current Israeli immigration policy makes it very difficult to provide employment assurance to immigrants and allows entry visas for employment purposes only for a limited number of years even in sectors with a shortage of workers such as construction, nursing [

12], and so. Hence, at present importing doctors to Israel is not a long-term solution to Israel’s medical needs.

A solution to the congestion problem in the Israeli healthcare system in general and in hospital maternity wards in particular can be achieved both from the supply side and from the demand side. On the supply side, training and internship placements for Israeli medical students can be increased (both in hospitals and in private childbirth centers that will be established). In this way, the number of jobs in hospitals can be increased and enable to employ more medical and midwifery nurse graduates in maternity wards. On the demand side - the home birth alternative can be legalized, thus eliminating the need to present at hospital delivery rooms (which will only be utilized in cases defined as relevant (. Thus, it can be concluded that the increasing congestion in the delivery rooms and maternity wards of Israeli hospitals justifies designing and implementing public policy capable of leading to mitigation of this congestion. Two possible alternatives for such a policy will be proposed below.

Recognizing that the increasing congestion in the delivery rooms and maternity wards of Israeli hospitals justifies designing and implementing a public policy capable of leading to mitigation of this congestion, two possible alternatives for such a policy will be proposed below.

4.3.1. Home Birth

Home births are births that take place, by prior planning, at home or in some other non-medical facility. The delivery is usually accompanied by a midwife, doula, or obstetrician, and in limited cases with no assistance. Home births are very controversial. While medical organizations object to them, other organizations associated with childbirth (nursing, midwifery, public health, consumer information, doulas, and childbirth education) support home birth as a safe and logical choice for healthy women. Women themselves choose home birth mostly for reasons of safety, in the wish to avoid negative experiences in hospitals, in the expectation for low rates of medical intervention, and in the desire to give birth in a familiar and safe environment [

37].

4.3.1.1. Benefits and Risks of Home Birth

Most births in Israel and in the western world occur in a hospital. Some women, however, prefer to give birth at home for various reasons (such as giving birth in a calm home atmosphere, the woman has control of the entire delivery process and of her actions in its process, the wish for a natural delivery with no pain medications or medical intervention, the possibility of moving around and choosing their preferred labor position, and others). Side by side with these advantages for the mother, home births can also lead to reduced congestion in hospital delivery rooms and maternity wards. At the same time, there is a danger of possible risks entailed by delivery procedures that take place at home rather than in a hospital.

Therefore, many studies have been conducted with the aim of examining the risk of home births. On one hand, studies published attest to the relative safety of the home delivery procedure. For example, a study conducted in 2005, focusing on home births in North America, determined that preplanned home births with a certified midwife are as safe as giving birth in a hospital. The researchers compared some 5,500 home births to three million hospital births in the same year (all low-risk pregnancies). The number of medical interventions in home births was less than half those conducted during hospital deliveries and the infant mortality rate was similar to that in hospitals [

34].

Similarly, the results of another study conducted in England, which examined 65,000 births, showed that preplanned home births in low-risk pregnancies accompanied by a certified midwife, were just as safe as giving birth in a hospital delivery room [

6]. Similar results were shown in a study conducted in the United States, which arrived at the conclusion that preplanned home births in low-risk pregnancies involved much less medical interventions and a similar level of risk to the mother and baby, as hospital deliveries [

9].

Similarly, a study published in 2019, examining about half a million home births and half a million hospital births, also reached the conclusion that there is no difference in the mortality and morbidity of mothers and infants in the two methods [

32]. A further study conducted about a year later revealed too that low-risk pregnant women who opt for preplanned home birth have a much lower chance of undergoing medical interventions than women on a similar risk level who choose to give birth in a hospital [

56]. At the same time, all the studies held on this subject State that in cases of high-risk pregnancy the recommendation is to give birth in a hospital due to the relatively high chance of labor complications.

Then again, there are studies attesting to the high risk involved in the home birth procedure. For instance, a study that presents the many risks entailed by home births in the case of high-risk pregnancies as well as of home births carried out by uncertified midwives [

28]. The study conducted by Sánchez-Redeondo et al. also strongly determines that although home births can entail advantages for the mother and infant, there are at present insufficient data on safety or scientific evidence to support home birth [

60].

4.3.1.2. Increasing Awareness of Home Birth around the World

Due to the drop in maternal and fetal mortality during hospital delivery procedures over the years, pregnancy and childbirth are now treated as a relatively safe process. As a result, social awareness of the option of home birth, which can have advantages for the mother and baby, has grown. A good example of this is the activity of the home birth movement, which began operating in the United States in the early 1990s and maintains an alternative set of health-related beliefs promoting a prenatal and childbirth model contrary to the customary medical model [

48]. Home births occur in developing countries and in developed countries [

5], however the attitude of the establishment to home birth differs between countries.

In the Netherlands, where the proportion of home birth is the highest in Europe, the State encourages mothers to give birth at home by providing negative financial incentives to those who choose to give birth in a hospital with no underlying medical reason (however, despite the fact that home birth was very common in Netherlands for decades, nowadays the rates are actually declining). Britain too has a positive attitude to home birth in low-risk pregnancies, and it is included in the basket of medical services for which mothers are eligible [

71]. The proportion of home births is still low in all countries, however, including those that encourage them.

In the United States, for example, the rate of home births was only 0.6-0.8% annually during 2004-2019 [

38]. However, their prevalence has grown in recent years and the absolute number of home births in the United States reached more than 38 thousand per year during 2018-2019, for a relative rate of 1.02% and 1.03% (respectively) of all births in each of these years. Moreover, in 2020 a conspicuous rise was evident in the number of home births in the United States, where their number reached more than 45 thousand births, 1.26% of all births for that year [

29]. It appears that the lockdown policy applied in the United States during the corona virus epidemic (similar to other countries) stimulated the growth in the number of home births [

54].

4.3.1.3. Home birth in Israel

Hundreds of home births take place in Israel each year, constituting some 0.3-0.4% (from the data of the Israeli Ministry of Health) of the total number of births, and their number is growing every year [

7]. The Israeli Ministry of Health recognizes childbirth as a medical procedure for all purposes (and even as a medical emergency) and therefore does not encourage deliveries outside the hospitals and even acts against this practice. Accordingly, the Israeli policy imposes many restrictions on home birth and specifies the necessary preconditions (Such as: a pregnancy of a single fetus with head presentation, fetus weight of 2.5-4 kg, documentation of the mother's medical history, ruling out gestational diabetes, prenatal ultrasound screening, and more) that allow a physician or midwife to attend them. In addition, the position of the Ministry of Health (until 2017) has been manifested in the policy regarding financial benefits to which mothers are entitled, and the hospitalization grant and childbirth grant in particular (Accordingly, the hospitalization grant and childbirth grant have been awarded only to those who give birth in a hospital or who present at a hospital after the delivery for a stay of at least 12 hours). This policy has strictly criticized by those in favor of encouraging home births in Israel [

40]. However, since then they do receive the universal childbirth grant, which is given to every woman who gives birth in Israel.

Therefore, examining the option of designing a public policy to encourage home births in Israel must take into account the need for planning to keep home births and births at out-of-hospital clinics as safe as possible in order to avoid possible harm to the mother and child. Detailed plans and strategies for transferring patients from out-of-hospital settings to hospital settings should be made, as well as predicating the approval for home births on required threshold conditions regarding constraints involving the distance [and therefore evacuation/transfer times] to medical facilities. In addition, such a policy should take into account the fact that home birth requires much more investment in training midwives for this purpose and providing them with the necessary equipment. Also, the State must allocate budgetary resources to fund home births, since at present these are not subsidized at all by the state. Therefore, women pay a substantial sum of money out-of-pocket for home births, although it is much less costly than hospital births.

4.4. Privatization of Out-of-Hospital Birth Procedures

At present, the policy of the Israeli Ministry of Health forbids private out-of-hospital births and states that from a medical respect, preference should be given to birth in the delivery room of a recognized and certified hospital [

43]. According to this policy, only hospital births can ensure best medical and nursing supervision and care of the mother and child. At the same time, ministry policy allows home birth but limits the mother’s financial benefits (as shown above).

Nevertheless, several private childbirth centers operate in Israel, where hundreds of babies have been born over the years, however their activity has not been recognized by the heads of the Ministry of Health, to say the least, who have taken action to close them by legal means and through closure orders. One example of this is a petition heard in an Israeli court in April 2018, submitted by the directors of a private facility called “Bet Yoldot” against the Ministry of Health’s decision to close it, where the petition was rejected. Eventually, they appealed to the Supreme Court, which in 2021 ruled that the closure was illegal and that birth centers are not hospitals in the way the law regulating hospitals had intended (reflecting the approach that physiological birth is not a medical event). In March 2023, the Ministry of Health distributed new regulations for public comment (which were given by May 2023). Some professionals reacted with much criticism of these regulations, which State that in the absence of laws regulating birth centers, the existing regulations for home birth will be implemented in the meantime. However, those regulations are very restricting and certainly very far from promoting out-of-hospital solutions.

Hospitals in Israel perceive births as an important source of financial income, as they are significantly compensated by the Ministry of Health for services provided, by the number of mothers who give birth. Therefore, hospitals market themselves to expecting mothers and offer them pampering conditions in order to convince them to give birth in their delivery rooms. This allows the hospitals to become a monopoly as birthing facilities in Israel and to reduce the options of giving birth elsewhere. As a result, congestion in the delivery rooms and maternity wards at Israeli hospitals is growing.

In addition, the money hospitals receive from the State for childbirth is not utilized only for operating and improving maternity services, rather they are free to use it for any other purpose in the hospital. This and more, a large number of hospitals are owned by the State, so this is a way to provide funds that eventually return to the State. Hence, it can be said that organizational politics determine some of the considerations and decisions involved in this issue.

This Israeli policy is contrary to the general trend in many other countries to move health care services (including rehabilitation and mental health services) to the community. Hence, adding non-medical deliveries to this trend will not only save money but can contribute to the well-being of women and their family. Therefore, it seems that changing the policy of the Ministry of Health to allow and even encourage establishment and operation of private birthing centers outside the hospitals can have a real contribution both to the well-being of the women giving birth as well as to regulating the congestion at the hospitals. Moreover, such a policy (if applied) will enable the employment of additional medical personnel involved in the delivery process (gynecologists, pediatricians, midwives, nurses, etc.), to meet the existing demand for delivery services in Israeli society, unrelated to the limited number of positions allocated in advance to the hospitals and subject to Ministry of Health budgets.

5. Conclusions

The study describes the market failure in the Israeli healthcare system, which is linked to the high congestion in Israeli hospitals. This congestion is generated by a combination of the increasing demand for healthcare services and the relatively slow growth rate of the healthcare system’s supply of services and various resources (as medical personnel and hospital rooms). In accordance with this, the research findings indicate that Israeli society is characterized by a high fertility level (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and a birth rate that has been rising consistently over the years (

Figure 3), side by side with extremely high congestion in the gynecology and obstetrics departments of local hospitals (

Table 2).

As stated, unlike illnesses and injuries that can be reduced by developing medications, medical technologies, and tele-medicine, pregnancy and childbirth are not considered an illness and there is no justification for encouraging reduced demand, but rather a way must be found to provide access to healthcare services in a different and more efficient method in order to reduce the congestion in hospital maternity wards and delivery rooms. Accordingly, the study presents two alternatives for a public policy related to the delivery procedure, capable (together or separately) of regulating the high congestion in delivery rooms and maternity words in Israeli hospitals.

The first alternative proposed is home birth, which allows carrying out delivery procedures at home with no need to come to a hospital. There is indeed a professional debate and many differences of opinion regarding the safety of home birth, however in recent years various western countries (Britain, United States and more) have begun to allow and even encourage this form of birth. In these countries, the home birth policy focuses on pregnant women at low risk and is based on studies showing that the risk to these women and their babies is no greater than that existing in hospitals. In contrast, the Israeli policy on home birth seeks to limit this option as much as possible, by presenting medical opinions that warn of the dangers and by instituting restrictions and conditions, as well as completely depriving women who do not give birth in a hospital from eligibility for childbirth benefits.

The second alternative proposed is establishing private childbirth centers in Israel, as a way of regulating the congestion in delivery rooms and maternity wards in public hospitals. Examination of the Israeli policy on this issue shows that the Ministry of Health objects to the operation of such private centers, while presenting the medical risks allegedly inherent in their activity. Notably, Israeli hospitals receive budgetary compensation by the number of births that take place within them, and therefore the possibility that their objection to private birthing centers is affected among other things by financial considerations should not be ruled out.

Implementation of these alternatives could reasonably have a positive impact on Israel’s healthcare system, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, encouraging home birth as an alternative and providing options for giving birth at private childbirth centers would diminish utilization of the limited delivery room resources, reduce the demand for them, and thus ease the burden on hospital medical staff (physicians, midwives, nurses, etc.). In addition, expanding employment options for midwives, gynecologists, and pediatricians outside the hospitals would increase the demand for these professions, which might lead to a rise in the number of practitioners and an improved ratio of physicians, nurses, and midwives per thousand residents in international indices. In addition ,many countries offer midwifery-led services in birth centers and obstetrician-led services in hospitals, so that women can choose the type of service that fits their needs and values. Therefore Implementation of these alternatives is not only a solution for congestion, but it is a basic human rights and women's rights issue.

Qualitatively, providing additional options for childbirth on a parallel track to the current customary well-organized childbirth procedure in hospitals would improve the quality of the birth procedure. First, when out-of-hospital solutions are not widely implemented, the overwhelmed maternity and childbirth services become more and more medicalized, resulting in suboptimal services and further restricting women's choices. For example, Pitocin administration to induce birth has increased in recent years at a rate that cannot reflect a change in medical needs; it seems to reflect a congested system, seeking ways to streamline processes. Therefore, expanding birth options outside the hospitals can help reduce the incidence of this phenomenon.

Secondly, increase the competition between the different factors engaged in this field (hospitals, private childbirth centers, private doulas, etc.) and lead to an improvement in the quality of services provided to mothers and families. At present there is already considerable competition between hospitals, resulting in attempts to attract women to their delivery services in order to receive the significant financial compensation provided by the Ministry of Health. This is attested to by the recently expanding trend in Israeli hospitals of allocating private luxurious delivery rooms to women giving birth and their families in order to tempt them to opt for these hospitals. Therefore, developing additional options for childbirth outside the hospitals would compel the hospitals to improve the quality of services for mothers even further.

Therefore, it is necessary to examine and gauge the effects of these policy steps )after a period of time( on the following indicators: Measures of impact on hospital performance - Gauging the number of births that take place in hospitals, the congestion rate at hospital delivery rooms and maternity wards and the quality of services provided to mothers and families compared to the period before implementation of the proposed policy steps. In addition, it is suggested that the financial incentives for hospitals be changed, basing them on service quality indicators instead of quantitative measures (the number of births that take place in hospitals) as at present. Home birth indicators- Gauging the number of home births in Israel before implementation of the policy steps versus the number of home births after removing the restrictions on this alternative. Also, measuring the rate of complications and death cases (infant and mother mortality) caused during home births and examining the satisfaction rates of mothers who preferred this alternative. Occupational impact (gynecologists, midwives, etc.)- Examining the change in the number of gynecologists, midwives, etc. after offering employment opportunities in private birthing centers in Israel.

In conclusion, the purpose of public policy is to deal with known market failures or imbalances through policy tools. However, the most effective way of dealing with public problems is to prevent them to begin with or at least to slow down their aggravation. Therefore, public policy should not be seen only as a response to an event or a crisis that occurred, but mainly as an effort to take actions with horizons, in the public interests. That is, it is possible to design a policy in a certain domain before a problem is identified, in order to prevent an anticipated problem.

The high congestion and occupancy rate problems in Israel’s hospital wards are well known and have been detailed in various official reports (by the Israeli Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization). However, while in order to reduce congestion in the various in-patient departments it is possible to act to reduce the demand for in-patient services, there is no intention to reduce the demand for maternity services, since the State of Israel sees this as a positive trend that corresponds with the values of Israeli society )high birth rates(. Therefore, based on the assumption that the demand for delivery room services in Israel is expected to continue growing in accordance with the continuous growth of the Israeli population, policy makers must act immediately to prevent future failures that may be caused by these expected trends.

Indeed, on one hand, it is not realistic to present home births as the only alternative to the birthing procedure that takes place in hospitals, but as another alternative to it. On the other hand, the privatization of the birth process can indeed help reduce congestion in the delivery room, but can create social problems such as increasing socio-demographic gaps and inequality level in Israeli society. Hence, It is possible to combine these two alternatives and at the same time take care of expanding the personnel in the maternity wards in the hospitals.

Therefore, the innovation of this study is manifested by bringing this issue to the research field and the public agenda in Israel with the aim of shining a spotlight on the paradox that exists in the emergence of a real (and even life-threatening) problem related to overcrowding in maternity wards and delivery rooms arising from a welcome and desirable phenomenon (fertility rates, high pregnancy and birth). This paradoxical reality requires the attention of the decision makers relevant to the issue in order to design a public policy that will allow the continued encouragement of childbirth while maintaining the safety of the women giving birth and the young babies. Therefore, this article anticipates the future and calls to establish public policy that involves regulating the congestion in Israel’s delivery rooms in order to prevent disasters that may occur in the absence of actions addressing this issue.

However, the government instability typical of Israel in recent years is contributing to the formation of short-sighted public policy that reacts to current events in retrospect instead of planning and designing in advance policy capable of preventing failures and future problems [

12];[

16]. Therefore, it is only to be expected that the issue of the increasing congestion in Israeli hospitals in general and in the delivery rooms and maternity wards in particular does not top Israeli decision makers’ priorities. Nevertheless, this study calls for forming a public policy on this issue, in light of the continued anticipated growth in fertility and childbirth rates in Israeli society, which might increase the congestion in delivery rooms and maternity wards until the resources of the healthcare system will be exhausted, resulting in loss of human life.

Past events around the world and in Israel show that sudden constraints and crises expedite changes in people’s behavior patterns in various life areas and compel policy makers to respond to current constraints and promote significant policy changes within a fairly short time range. The outburst of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 and the introduction of a lockdown policy aimed at eradicating the pandemic and generating behavior and policy changes in various areas around the world constitute a conspicuous example of this argument. Closing the public expanse, paralyzing public transportation, and the like, accelerated the transition to tele-work in all countries in general and in Israel in particular [

49]; [

55]. Similarly, institutions of higher education as well began to teach remotely and rapidly expedited the promotion of digitation and virtualization processes necessary for the system of higher education at present [

17]. Finally, the significant increase in the number of home births in the United States in 2020, as mentioned in the findings chapter, is notable.

Therefore, the research conclusions indicate that policy makers in Israel must foresee in advance the increasing congestion in hospital delivery rooms and maternity words and design alternative solutions at present, before the appearance of crisis circumstances will make it essential to find prompt solutions. The study recommends simultaneously examining and promoting the two alternative solutions proposed in this study, in the assumption that the growing demand for pregnancy and birth in Israeli society will continue and therefore actions must be taken to increase the supply of birthing facilities, including home birth and private medical birthing centers.