1. Introduction

In recent years, research examining the complex interrelationships between mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality has garnered increasing attention. The recognition of these interconnected domains not only elucidates the intricate nature of human behavior but also underscores the significance of addressing holistic well-being. The present study delves into this multifaceted nexus, aiming to shed light on the intricate dynamics that transpire "from mind, to plate, to pillow."

The correlation between mental health and eating disorders has been extensively investigated, with numerous studies clarifying the bidirectional relationship between them [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Individuals grappling with mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, or stress, often exhibit alterations in eating behaviors, ranging from excessive consumption to disordered eating patterns like binge eating or restrictive dieting [

5]. Conversely, the onset or exacerbation of mental health issues can stem from the distress associated with disordered eating habits, creating a cyclical pattern that perpetuates both conditions [

6].

Moreover, the role of sleep quality in this triad cannot be overstated. Sleep disturbances have been linked to a plethora of mental health disorders and eating disturbances, with evidence suggesting a bidirectional association [

7]. Poor sleep quality not only intensifies symptoms of mental health disorders and disrupts eating patterns but also independently contributes to the development of disordered eating behaviors [

8].

While considerable research has explored each component individually, there remains a dearth of comprehensive studies examining the interplay between mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality within a single framework. This is particularly crucial as diverging hypotheses exist regarding the directionalities and mechanisms underlying these associations. Some theories propose that mental health disorders precipitate disordered eating and sleep disturbances [

9], while others suggest that alterations in eating patterns or poor sleep quality serve as precursors to mental health issues [

10].

The current state of the research field reflects a growing consensus on the need for holistic approaches that consider the interconnectedness of mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality [

11]. However, a nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms and directional relationships remains elusive, necessitating further investigation.

With this backdrop, the primary aim of this cross-sectional study is to examine the intricate interplay between mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality among a diverse sample population. Specifically, we hypothesize that mental health, eating disorders and sleep quality will be intercorrelated, and poor sleep quality will predict poorer mental health outcomes and disordered eating.

By elucidating these relationships, this study endeavors to contribute to the development of targeted interventions and holistic treatment approaches that address the interconnected nature of mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality. Ultimately, a comprehensive understanding of "from mind, to plate, to pillow" dynamics holds promise for enhancing overall well-being and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Methodology

This investigation employed a cross-sectional approach, utilizing an online survey administered in both Greek and English languages via the Sogolytics online survey platform [

12]. The initial two survey queries served as inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring participants' acknowledgment of the study's terms and conditions, as well as confirming their age fell within the 18 to 65-year range. In order to reduce the likelihood of survey abandonment [

13], demographic questions covering areas such as education, employment status and gender were placed towards the end of the survey. The survey was distributed via direct messaging across various social media platforms, accompanied by follow-up reminders to enhance participant engagement and facilitate addressing any inquiries or concerns pertaining to the study. This blended methodology leverages the benefits of both online and mailed questionnaires [

14,

15,

16].

Prior to commencing data collection, the study's objectives and hypotheses were explicitly outlined, furnishing a comprehensive framework for research analysis and interpretation. The final sample meeting the inclusion-exclusion criteria comprised 404 adult participants.

2.2. Scales

2.2.1. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21)

The DASS-21 is a widely recognized self-report measure used to gauge the severity of symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Comprising 21 items, the scale is divided into three sub-scales, each focusing on specific psychological constructs: depression, anxiety, and stress. Respondents rate the frequency and intensity of their experiences over the past week using a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms [

17]. An example question is: "Over the past week, how often have you felt downhearted and blue?" Participants select a response ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time).

Employing a standardized scoring system, the DASS-21 enables the computation of individual sub-scale scores as well as a total combined score, offering a comprehensive assessment of emotional well-being. Renowned for its reliable and valid psychometric properties, it serves as an invaluable tool for both clinical and research purposes in assessing and monitoring mental health conditions [

18].

Due to its robust assessment framework and sensitivity to changes in symptom severity, the DASS-21 is indispensable for identifying and evaluating individuals experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Its systematic approach and thorough measurement contribute to a deeper understanding of psychological distress, enabling targeted interventions and improved mental health outcomes [

19]. In our study, the DASS-21 demonstrated excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.953.

2.2.2. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short (EDE-QS)

The EDE-QS, a shortened version of the 28-item Eating Disorder Examination (EDE-Q), is a validated self-report tool consisting of 12 items, designed to assess symptoms of eating disorders. It evaluates various aspects of disordered eating behaviors, including dietary restraint, eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns. Respondents rate the frequency and severity of these behaviors over the past week using a 4-point scale, where higher scores indicate a higher level of pathology [

20]. An example question is: "How dissatisfied have you been with your weight or shape?"

Recognized widely and utilized extensively, the EDE-QS plays a crucial role in identifying individuals at risk of eating disorders, allowing for early intervention and tailored treatment strategies. Its standardized scoring system and comprehensive assessment approach contribute to a thorough understanding of eating disorder pathology, aiding clinicians and researchers in effectively managing and studying these complex conditions [

21]. In our study, the EDE-QS exhibited strong internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.885.

2.2.3. Single-Item Sleep Quality Scale (SQS)

The SQS, is a validated tool specifically designed to evaluate sleep quality using a single-item approach. This scale offers a straightforward and convenient method for individuals to assess their own sleep quality. Participants are asked to rate their sleep quality over a period of seven days using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10. The incorporation of a discretizing visual analogue scale enhances the sensitivity of the measurement, allowing for more nuanced responses [

22]. It's important to note that this scale has been validated for use in assessing sleep quality among healthy adults [

23].

2.3. Data Analysis

A comprehensive review of the data was undertaken to identify any potential omissions. Instances where participants abruptly ceased the questionnaire (classified as Missing Completely at Random) led to the exclusion of the corresponding data from the analysis [

24]. In cases of inadvertent omissions (classified as Missing at Random), missing data points were substituted with the mean value derived from all respondents' answers.

The data was exported in a format compatible with SPSS v28 for import and processing. Statistical analysis and visualization were conducted using SPSS v28. Before subjecting the data to statistical tests, a regularity check was performed to ensure compliance with established criteria. To ensure the most accurate and reliable assessment of regularity, a combination of visual examination and the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed [

25].

Statistical analysis involved Pearson’s correlation, Independent samples t-test, and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables found to adhere to normal distribution, as determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Additionally, multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of sleep quality on eating disorders, adjusting for possible confounders. The predetermined level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

The survey drew 497 participants. After eliminating 75 respondents who did not fulfill the survey's inclusion requirements, as well as 15 incomplete (less than 50% of total questions answered) or random responses (items answered in less than 3 minutes), the final sample size was 407 adults, comprising 68.3% women, 31% men, and 0.7% identifying as non-binary. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) in the means of DASS-21 and EDE-QS, and BMI across genders, with women having higher scores. The majority of participants (61.6%) were aged between 18 and 29 years old. This age group had also statistically significant (p<0.05) higher scores of DASS-21, and lower sleep quality than individuals 60-65 years of age.

3.2. Correlations between Sleep Quality, Mental Health, and Eating Disorders

In order to investigate the potential associations between SQS, DASS-21, and EDE-QS in healthy individuals, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. The statistical analysis unveiled a significant correlation between SQS with DASS-21 and EDE-Q. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between DASS-21 and EDE-QS (

Table 1).

3.3. Correlations between Sleep Quality, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

When the relationship between sleep quality and the DASS-21 scale's components was further examined, it was found that there was a statistically significant (

p<0.05) negative correlation between stress, anxiety, and depression and sleep quality (

Table 2).

3.4. Sleep Quality Categories, Mental Health and Disordered Eating

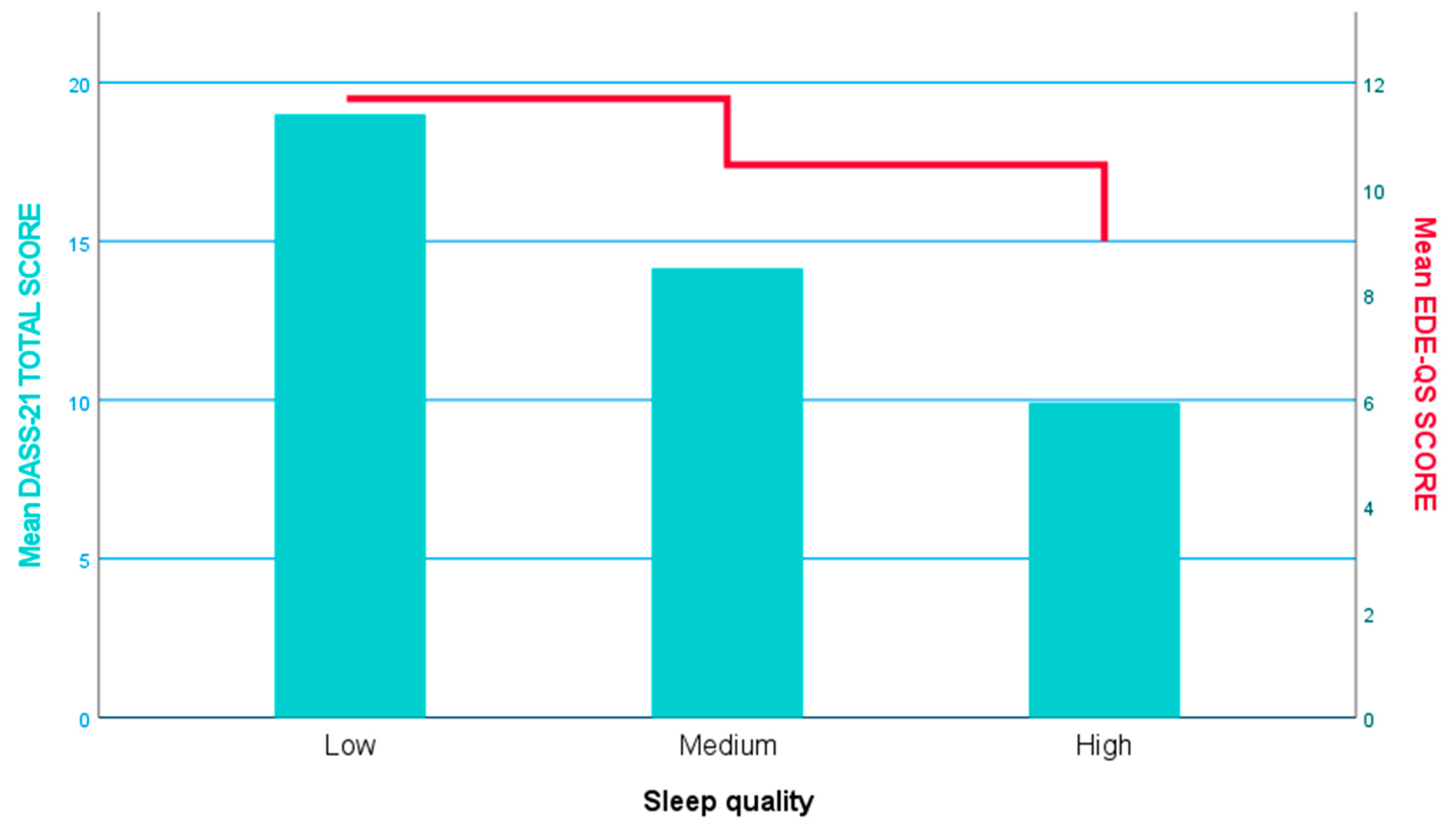

One-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant (

p<0.05) difference in the means of both DASS-21 and EDE-QS scores in various sleep quality categories, with individuals with low sleep quality demonstrating higher DASS-21 and EDE-QS scores (

Figure 1).

Moreover, multinomial logistic regression analysis highlighted (

Table 3) low sleep quality as a risk factor for both mental health (OR: 1.071, 95% CI: 1.042, 1.102,

p<0.05, low

vs. high sleep quality), and eating disorders (OR: 1.047, 95% CI: 1.004, 1.092,

p<0.05, low

vs. high sleep quality).

4. Discussion

The current research marks the inaugural exploration of the relationships between sleep quality, mental health, and eating disorders in Greece. By delving into this intersection, our study contributes to the existing body of literature on the significance of sleep quality in both mental and physical health [

26]. While previous research has investigated various aspects of well-being, to our knowledge, none have investigated the collective impact of sleep quality and factors affecting mental health, such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

The findings of this study reveal significant associations between mental health status, disordered eating, and sleep quality among participants. Notably, individuals with higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress reported poorer sleep quality, consistent with previous research linking psychological distress to sleep disturbances [

27,

28]. Furthermore, the presence of disordered eating behaviors was found to exacerbate these associations, with higher levels of disordered eating correlating with worse sleep outcomes. These findings support the notion of a bidirectional relationship between mental health and sleep, whereby disturbances in one domain can exacerbate issues in the other.

One of the strengths of this study is its examination of the role of eating behaviors in the mental health-sleep relationship. Previous research has primarily focused on either mental health or eating disorders separately [

29,

30] neglecting the potential interplay between these factors. By incorporating measures of disordered eating, this study underscores the importance of considering eating behaviors in understanding the complexities of mental health and sleep disturbances. Future research should continue to explore these interconnected pathways, perhaps employing longitudinal designs to elucidate temporal relationships and potential mechanisms underlying these associations.

The observed associations between depressive symptoms, eating disorders, and poor sleep quality raise important clinical implications. Given the bidirectional nature of these relationships, interventions targeting mental health, eating behaviors, and sleep quality may yield synergistic benefits. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has shown promise in addressing depressive symptoms, eating disorders, and insomnia [

31,

32,

33]. Integrative approaches that incorporate mindfulness-based techniques, dietary interventions, and sleep hygiene education may also be beneficial in improving overall well-being among individuals with comorbid mental health and sleep disturbances [

34].

Furthermore, the findings highlight the need for holistic assessments and interventions in clinical settings. Rather than treating mental health, eating disorders, and sleep disturbances as separate entities, healthcare professionals should adopt a comprehensive approach that addresses the interconnectedness of these factors. Screening tools that assess for symptoms across these domains may facilitate early identification and intervention. Collaborative care models involving multidisciplinary teams (e.g., psychologists, dietitians, sleep specialists) may also enhance treatment outcomes by addressing the diverse needs of individuals with comorbid conditions.

While this study provides valuable insights into the interplay between mental health, eating disorders, and sleep quality, several limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and the directionality of the observed relationships remains unclear. Longitudinal studies are needed to elucidate temporal sequences and potential mechanisms underlying these associations. Secondly, reliance on self-report measures introduces the possibility of response bias and social desirability effects [

35]. Future research could utilize objective measures (e.g., actigraphy, polysomnography) to complement self-reported data and provide a more nuanced understanding of sleep patterns. Additionally, the sample predominantly comprised young adults from a single geographic region, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Replication studies involving more diverse populations are warranted to validate the current findings and ensure their applicability across different demographic groups.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the intricate connections between mental health, eating disorders, and sleep quality. By elucidating these interrelationships, this research contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of psychological well-being. Moving forward, interdisciplinary collaborations and longitudinal investigations will be essential in further unraveling the complexities of these interactions and developing targeted interventions to improve the overall health and well-being of individuals affected by these interconnected issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Efstratios Christodoulou; Data curation, Efstratios Christodoulou and Verra Markopoulou; Formal analysis, Efstratios Christodoulou; Investigation, Efstratios Christodoulou and Verra Markopoulou; Methodology, Efstratios Christodoulou, Verra Markopoulou and Antonios Koutelidakis; Project administration, Antonios Koutelidakis; Resources, Efstratios Christodoulou and Verra Markopoulou; Software, Efstratios Christodoulou and Verra Markopoulou; Supervision, Antonios Koutelidakis; Validation, Efstratios Christodoulou and Antonios Koutelidakis; Visualization, Antonios Koutelidakis; Writing – original draft, Efstratios Christodoulou; Writing – review & editing, Antonios Koutelidakis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of the Aegean’s ethics and deontology committee (no. 17715/09.09.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tan EJ, Raut T, Le LK, et al. The association between eating disorders and mental health: an umbrella review. J Eat Disord. 2023, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costandache GI, Munteanu O, Salaru A, Oroian B, Cozmin M. An overview of the treatment of eating disorders in adults and adolescents: pharmacology and psychotherapy. Postep Psychiatr Neurol. 2023, 32, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou E, Markopoulou V, Koutelidakis AE. Exploring the Link between Mindful Eating, Instagram Engagement, and Eating Disorders: A Focus on Orthorexia Nervosa. Psychiatry International. 2024, 5, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche M, Godefroy C, Achamrah N, et al. Mental health and health behaviours among patients with eating disorders: a case-control study in France. J Eat Disord. 2022, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braden A, Barnhart WR, Kalantzis M, et al. Eating when depressed, anxious, bored, or happy: An examination in treatment-seeking adults with overweight/obesity. Appetite. 2023, 184, 106510. [CrossRef]

- Bray B, Bray C, Bradley R, Zwickey H. Mental health aspects of binge eating disorder: A cross-sectional mixed-methods study of binge eating disorder experts' perspectives. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 953203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palagini L, Hertenstein E, Riemann D, Nissen C. Sleep, insomnia and mental health. J Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehr JB, James MH. Sleep disruption as a potential contributor to the worsening of eating disorder pathology during the COVID-19-pandemic. J Eat Disord. 2022, 10, 181. [CrossRef]

- Carollo A, Zhang P, Yin P, et al. Sleep Profiles in Eating Disorders: A Scientometric Study on 50 Years of Clinical Research. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti C, Malagutti G, Maraglino V, et al. Sleep Pathologies and Eating Disorders: A Crossroad for Neurology, Psychiatry and Nutrition. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheonea TC, Oancea CN, Mititelu M, Lupu EC, Ioniță-Mîndrican CB, Rogoveanu I. Nutrition and Mental Well-Being: Exploring Connections and Holistic Approaches. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou E, Meca A, Koutelidakis AE. Herbal Infusions as a Part of the Mediterranean Diet and Their Association with Psychological Resilience: The Paradigm of Greek Mountain Tea. Nutraceuticals. 2023, 3, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones TL, Baxter MA, Khanduja V. A quick guide to survey research. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013, 95, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedbakhsh M, Omid A, Khodadoostan M, Shavakhi A, Adibi P. Using instant messaging applications to promote clinical teaching of medical students. J Educ Health Promot. 2022, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon V, Muraleedharan A. Internet-based surveys: relevance, methodological considerations and troubleshooting strategies. Gen Psychiatr. 2020, 33, e100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou E, Meca A, Koutelidakis AE. Herbal Infusions as a Part of the Mediterranean Diet and Their Association with Psychological Resilience: The Paradigm of Greek Mountain Tea. Nutraceuticals. 2023, 3, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezirkianidis, C.; Karakasidou, E.; Lakioti, A.; Stalikas, A.; Galanakis, M. Psychometric Properties of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a Greek Sample. Sci. Res. Publ. 2018, 9, 2933–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei TP, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F. Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol. 2013, 48, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, PJ. Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21): psychometric analysis across four racial groups. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2007, 20, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gideon N, Hawkes N, Mond J, Saunders R, Tchanturia K, Serpell L. Development and Psychometric Validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 Item Short Form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2018 Nov 5;13, e0207256]. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prnjak K, Mitchison D, Griffiths S, et al. Further development of the 12-item EDE-QS: identifying a cut-off for screening purposes. BMC Psychiatry. 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder E, Cai B, DeMuro C, Morrison MF, Ball W. A New Single-Item Sleep Quality Scale: Results of Psychometric Evaluation in Patients With Chronic Primary Insomnia and Depression. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereli M, Kahraman T. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of single-item Sleep Quality Scale in healthy adults. Sleep Med. 2021, 88, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak SK, Kim JH. Statistical data preparation: management of missing values and outliers. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement-Carbonell V, Portilla-Tamarit I, Rubio-Aparicio M, Madrid-Valero JJ. Sleep Quality, Mental and Physical Health: A Differential Relationship. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J Cell Mol Med. 2019, 23, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou E, Pavlidou E, Mantzorou M, et al. Depression is associated with worse health-related quality of life, lower physical activity levels, and inadequate sleep quality in a Greek elderly population. Psychol Health Med. 2023, 28, 2486–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St James M, Rowse G, Weich S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021, 60, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzischinsky O, Tokatly Latzer I, Alon S, Latzer Y. Sleep Quality and Eating Disorder-Related Psychopathologies in Patients with Night Eating Syndrome and Binge Eating Disorders. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers P, Miguel C, Harrer M, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy vs. control conditions, other psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and combined treatment for depression: a comprehensive meta-analysis including 409 trials with 52,702 patients. World Psychiatry. 2023, 22, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaidesoja M, Cooper Z, Fordham B. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A map of the systematic review evidence base. Int J Eat Disord. 2023, 56, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossman, J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: An Effective and Underutilized Treatment for Insomnia. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou E, Deligiannidou G-E, Kontogiorgis C, Giaginis C, Koutelidakis AE. Fostering Resilience and Wellness: The Synergy of Mindful Eating and the Mediterranean Lifestyle. Applied Biosciences. 2024, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, JP. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Rev Saude Publica. 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).