Introduction

Dravet syndrome (DS) is a critical and severe type of pediatric epilepsy that not only presents with frequent and intense seizures but also has a notably high risk of

sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Despite extensive research, the exact biological mechanisms underlying the 15% incidence of SUDEP in DS remain elusive. [

1,

2,

3]. The majority of DS patients have

de novo mutations in the SCN1A gene [

1,

4,

5]. These mutations disrupt normal sodium ion flow across neuronal membranes, affecting neuronal excitability and potentially contributing to the severe epileptic phenotype and increased SUDEP risk observed in these patients [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Ionic channelopathies are disorders affecting multiple organ systems, with significant implications across various physiological functions. Recent studies utilizing concurrent electroencephalogram and electrocardiogram (ECG) assessments have identified a notably high prevalence (33-44%) of arrhythmias in patients with epilepsy [

6]. This data underscores the connection between neuronal and cardiac dysfunctions, suggesting that similar mechanistic pathways may be involved. Specifically, cardiac channelopathies can result from gain-of-function mutations, as observed in

Long QT Syndrome Type 3, or from loss-of-function mutations, as demonstrated in

Brugada Syndrome (BrS). Especially, BrS involves mutations in the SCN5A gene, responsible for encoding the myocardial sodium channel. This underscores the essential role of ion channel integrity in maintaining cardiac and neurological health [

1,

6].

In over 70% of individuals with DS, loss-of-function mutations are identified in the SCN1A gene [

7,

8,

9], responsible for encoding the α subunit Na

v1.1 of the

voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) [

4,

5], present in both the brains and hearts of mammals. This genetic anomaly highlights the interconnected nature of

“cardiocerebral channelopathies” where dysfunctions affect both cardiac and cerebral systems, potentially leading to sudden death [

10].

Cardiocerebral channelopathies are, therefore, types of epilepsy that manifest with arrhythmias. Thus, epilepsies can be exhibited in various ways on the ECG. Specifically, we wish to highlight the presence of

epsilon waves. These waves serve as a diagnostic criterion for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, manifesting as delayed depolarization of this ventricle, with low-amplitude potentials located between the end of the QRS complex and the onset of the T-wave, particularly in the right precordial leads from V1 to V3 [

11]. Although these waves can be detected in channelopathies involving sodium channels, such as in BrS [

12,

13], no specific cardiocerebral channelopathies involving these channels, such as DS, has ever been reported.

We present the first case of DS without structural cardiopathy, characterized by the presence of epsilon waves on the ECG.

Case Presentation

A 4-year-old child weighing 15 kg was attended at home by an Advanced Life Support Ambulance due to 16 generalized epileptic seizures in one day. The seizures are presumed to have been exacerbated by a fever of 39.5°C axillary, persisting for three days following vaccination. Upon physical examination, the patient was in an acceptable general condition. Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale was 15. No neck stiffness or other meningeal signs were present. Cardiac auscultation revealed rhythmic heart sounds with a good tone at 160 beats per minute. The remainder of the examination showed no notable findings.

Regular treatment included: Valproic acid 28 mg/kg/day, Clobazam 0.1 mg/kg/day, Stiripentol 125 mg every 12 hours, Epidiolex 12.5 mg/kg/day, and Carnitine 300mg every 12 hours.

The patient’s medical history revealed the following:

Family history: Two healthy adolescent siblings. Healthy parents. On the paternal side, a diagnosis of unspecified arrhythmia.

Genetic testing: Duplication of uncertain significance at 3p29. SCN1A gene mutation.

Two-dimensional Doppler echocardiography (performed two months prior): Atrioventricular and ventriculo-arterial concordance. Normal right chambers. Left ventricle was neither hypertrophic nor dilated with preserved systolic function. Left ventricular ejection fraction: 71%. Intact septa. No outflow tract obstruction. Conclusion: Structurally and functionally normal heart.

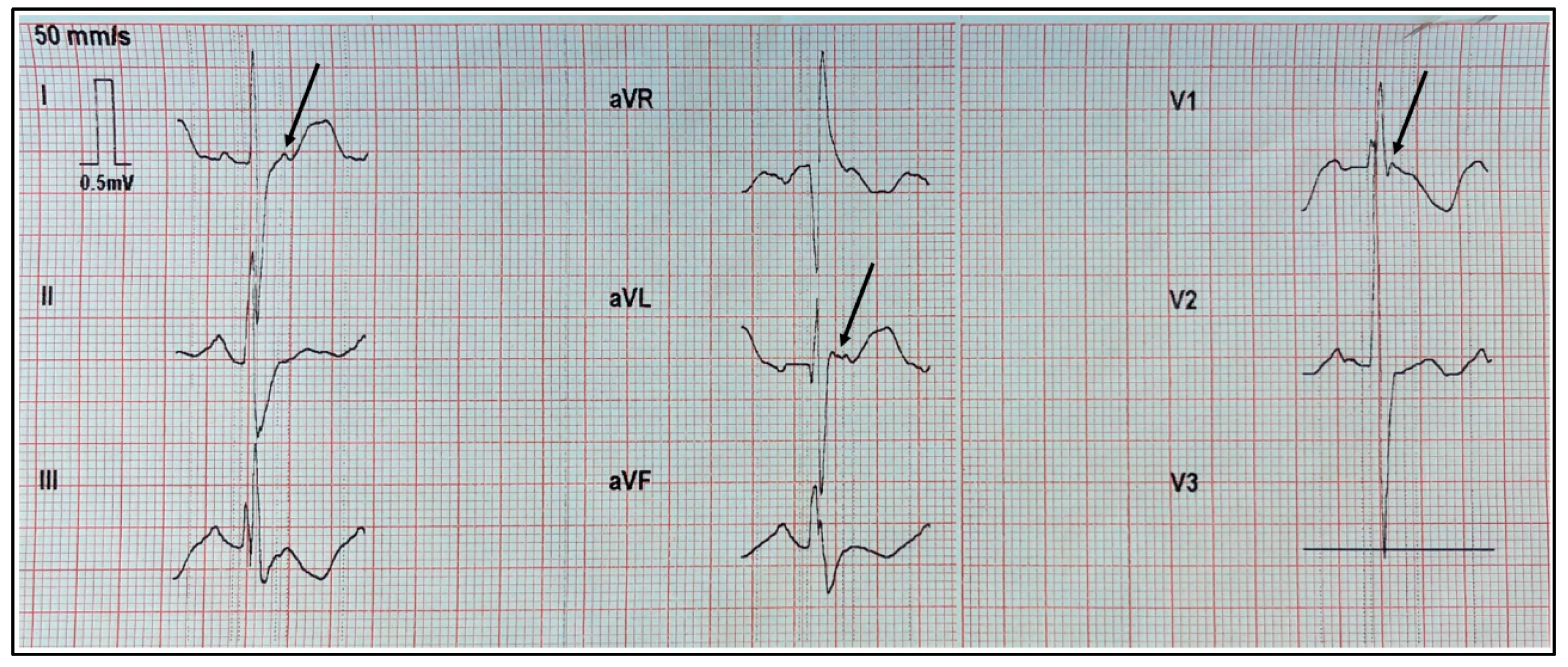

In the electrocardiogram performed at the patient’s home, we observed a right bundle branch block of the His bundle and epsilon waves in the high left frontal leads DI and aVL, as well as in the right precordial lead V1.

Figure 1 displays a recording at a speed of 50 mm/s with a vertical scale of 10 mm = 0.5 mV.

At the hospital, the blood tests did not reveal any significant changes, except for mild neutrophilia with accompanying lymphopenia. Valproic acid levels were normal at 54 μg/mL (normal range: 50 – 100 μg/mL).

Discussion

The SCN1A gene encodes the α-1 subunit of the Na

v1.1, a critical protein that constitutes VGSC. Pathogenic variants cause a reduction in sodium GABA-ergic inhibitory interneurons, leading to hyperexcitability of the neuronal network and the onset of seizures [

14,

15]. SCN1A is associated with various epileptic syndromes and a range of other disorders [

16,

17].

Epsilon waves serve as essential diagnostic markers for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, characterized by delayed depolarizations predominantly in the right precordial leads [

11]. Should the left ventricle be involved, epsilon waves can also manifest in the left and inferior leads [

13].

The epsilon wave represents delayed potentials resulting from slow intraventricular conduction due to segments of normal myocardium interspersed with fatty and fibrous tissue. It corresponds to early afterdepolarizations once the QRS reaches the isoelectric line. Although the epsilon wave is a depolarization anomaly, it manifests on the ECG at the beginning of repolarization [

13].

While epsilon waves are primarily associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, they have also been documented in various other conditions unrelated to this disease. These include right ventricular myocardial infarction, Uhl’s anomaly (partial or complete absence of the right ventricular myocardium), and after repair of tetralogy of Fallot, where one case was noted to develop a right ventricular outflow tract aneurysm following episodes of ventricular tachycardia. Additionally, epsilon waves have been reported in cardiac sarcoidosis, sickle cell anemia in patients with right ventricular hypertrophy due to pulmonary hypertension, and BrS [

12,

13].

Generally, the presence of epsilon waves is linked to fibrosis or structural changes in the myocardium of the right ventricle [

12]. However, an exception is BrS, which is primarily a cardiac channelopathy associated with sodium channels [

1,

6,

18,

19].

Two-dimensional Doppler echocardiography is highly sensitive to cardiac structural and functional changes and is used as one of the imaging tests in the diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia [

20]. The absence of findings on this test in our patient rules out structural heart disease. This prompts the question of how to account for the presence of epsilon waves in our patient. We propose that the underlying mechanism behind the emergence of epsilon waves might be related to abnormalities in sodium channel function.

In the study conducted by Auerbach et al. [

1], electrophysiological alterations were analyzed in a mouse model of DS through mutations in the SCN1A gene, which encodes the tetrodotoxin-sensitive Nav1.1 sodium channel. The results demonstrated a significant increase in both transient and persistent sodium current densities in isolated ventricular myocytes from these models. The researchers proposed that this increase could be attributed to augmented activity of the tetrodotoxin-resistant Nav1.5 sodium current, potentially resulting from a dysfunction in the Nav1.1 channel. This dysfunction could lead to a compensatory increase in the expression and functional activity of Nav1.5 channels in the membrane.

This heightened Nav1.5 current led to increased excitability, prolonged action potential duration, and the induction of early afterdepolarizations in the affected myocytes. Although the SCN5A gene encodes the α subunit of the Nav1.5 channel, which is predominant in mammalian hearts, it is important to note that Nav1.1 is also expressed in the ventricles, though its specific function in that region is still not clearly understood [

1].

We propose that the presence of epsilon waves, not only in our patient but also in any patient with DS, could be attributed to early afterdepolarizations due to non-structural phenomena. We hypothesize that the involvement of sodium channels, expressed by the SCN1A gene at both cerebral and cardiac levels, may be the initial factor triggering an increase in Nav1.5-mediated sodium currents. Thus, we introduce the novel hypothesis that epsilon waves could originate from intrinsic molecular processes of the sodium channels, rather than simply being due to myocardial fibrosis or delays in right ventricular activation.

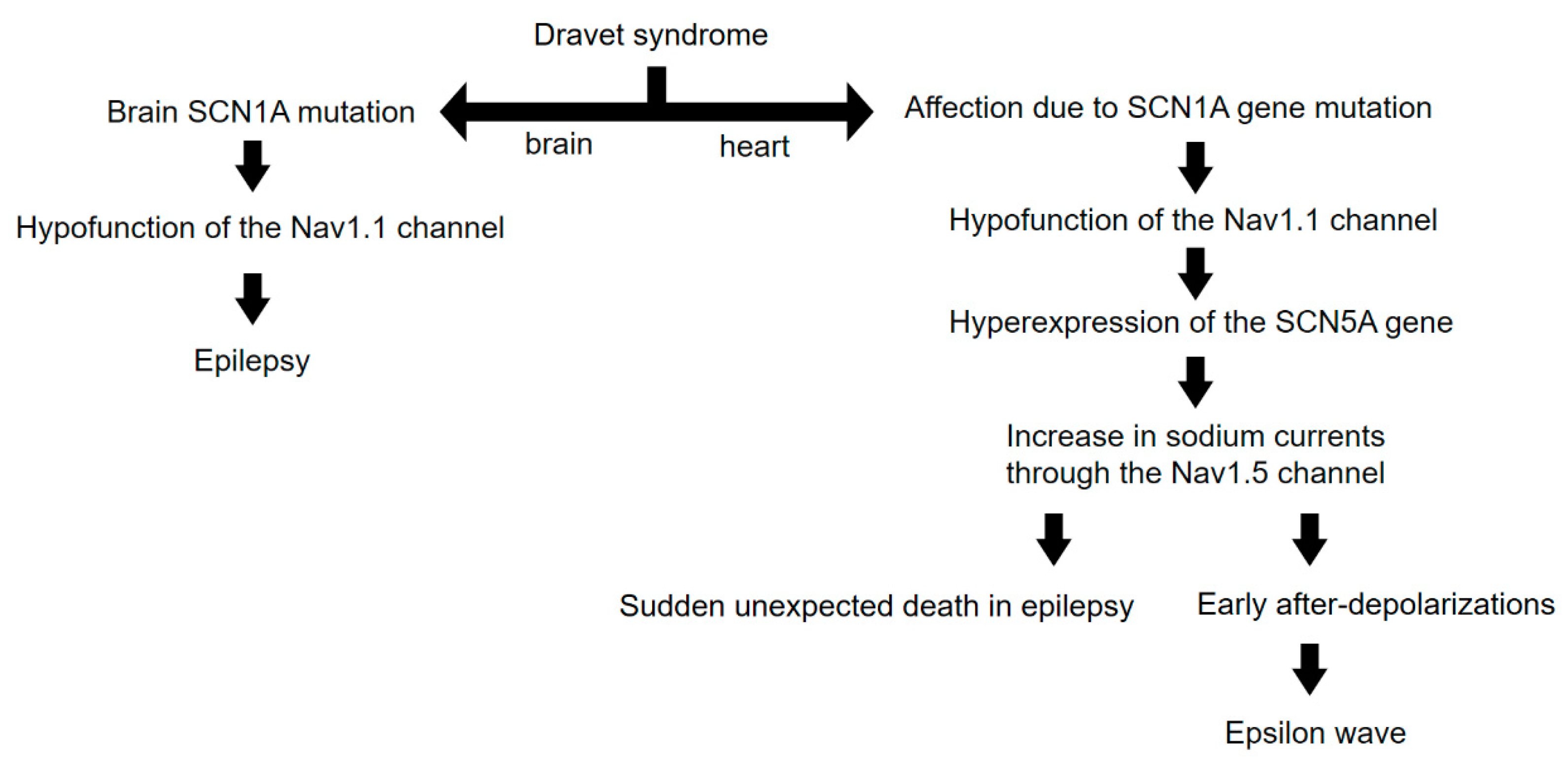

An outline of our reasoning up to this point is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Conclusions

In our study, we have documented for the first time the presence of epsilon waves in the electrocardiogram of a patient with Dravet Syndrome who lacks structural cardiac pathology. These epsilon waves are crucial indicators for the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia and manifest as delayed depolarizations, typically associated with structural changes in the myocardium. However, in our case, the epsilon waves appear to arise from non-structural phenomena related to alterations in sodium channels.

We suggest that anomalies in sodium channels, particularly those associated with the SCN1A gene, could explain the emergence of epsilon waves in patients with Dravet Syndrome. Our findings propose an underlying mechanism where alterations in sodium channels, observed at both the cerebral and cardiac levels, might contribute to atypical electrocardiographic manifestations, including epsilon waves, without the need for myocardial fibrosis or structural changes.

Therefore, the implications of our study are significant for understanding the connections between epilepsies and cardiac arrhythmias, emphasizing the importance of considering both aspects in the clinical assessment of patients with severe epilepsy such as Dravet Syndrome. Furthermore, we highlight the need for further research to explore in greater depth the interactions between sodium channels in the brain and heart, which could open new avenues for therapeutic interventions addressing both seizures and cardiac complications in these patients.

References

- Auerbach DS, Jones J, Clawson BC, Offord J, Lenk GM, Ogiwara I, Yamakawa K, Meisler MH, Parent JM, Isom LL. Altered cardiac electrophysiology and SUDEP in a model of Dravet syndrome. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e77843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, A.B. , Spinelli, A., Battaglia, D., Dravet, C., De Nisco, A., Saracino, A., Romagnoli, C., Lanza, G.A. and Crea, F. Electrical and autonomic cardiac function in patients with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dravet C, Bureau M, Oguni H, Fukuyama Y, Cokar O. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy: Dravet syndrome. Adv Neurol. 2005, 95, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Claes L, Del-Favero J, Ceulemans B, Lagae L, Van Broeckhoven C, De Jonghe P. De novo mutations in the sodium-channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001, 68, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisler MH, Kearney JA. Sodium channel mutations in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. J Clin Invest. 2005, 115, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman AM, Glasscock E, Yoo J, Chen TT, Klassen TL, Noebels JL. Arrhythmia in heart and brain: KCNQ1 mutations link epilepsy and sudden unexplained death. Sci Transl Med. 2009, 1, 2ra6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini C, Mei D, Temudo T, Ferrari AR, Buti D, Dravet C, Dias AI, Moreira A, Calado E, Seri S, Neville B, Narbona J, Reid E, Michelucci R, Sicca F, Cross HJ, Guerrini R. Idiopathic epilepsies with seizures precipitated by fever and SCN1A abnormalities. Epilepsia. 2007, 48, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djémié T, Weckhuysen S, von Spiczak S, Carvill GL, Jaehn J, Anttonen AK, Brilstra E, Caglayan HS, de Kovel CG, Depienne C, Gaily E, Gennaro E, Giraldez BG, Gormley P, Guerrero-López R, Guerrini R, Hämäläinen E, Hartmann C, Hernandez-Hernandez L, Hjalgrim H, Koeleman BP, Leguern E, Lehesjoki AE, Lemke JR, Leu C, Marini C, McMahon JM, Mei D, Møller RS, Muhle H, Myers CT, Nava C, Serratosa JM, Sisodiya SM, Stephani U, Striano P, van Kempen MJ, Verbeek NE, Usluer S, Zara F, Palotie A, Mefford HC, Scheffer IE, De Jonghe P, Helbig I, Suls A; EuroEPINOMICS-RES Dravet working group. Pitfalls in genetic testing: the story of missed SCN1A mutations. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016, 4, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall RD, Crompton DE, Petrovski S, Lam L, Cutmore C, Garry SI, Sadleir LG, Dibbens LM, Cairns A, Kivity S, Afawi Z, Regan BM, Duflou J, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, Semsarian C. Exome-based analysis of cardiac arrhythmia, respiratory control, and epilepsy genes in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2016, 79, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmuely S, Surges R, Helling RM, Gunning WB, Brilstra EH, Verhoeven JS, Cross JH, Sisodiya SM, Tan HL, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Cardiac arrhythmias in Dravet syndrome: an observational multicenter study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020, 7, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javier García-Niebla, Adrián Baranchuk, Antonio Bayés de Luna. Vol. 69. Issue 4. pages 438 (April 2016. [CrossRef]

- Platonov PG, Svensson A. Epsilon Waves as an Extreme Form of Depolarization Delay: Focusing on the Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2021, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrés Ricardo Pérez-Riera, Raimundo Barbosa-Barros, Rodrigo Daminello-Raimundo, Luiz Carlos de Abreu, Javier García-Niebla, Mauro José de Deus Morais, Kjell Nikus, Frank I. Marcus. Epsilon wave: A review of historical aspects. Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal. 2019, 19, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall WA, Kalume F, Oakley JC. NaV1.1 channels and epilepsy. J Physiol. 2010, 588 Pt 11, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogiwara I, Miyamoto H, Morita N, Atapour N, Mazaki E, Inoue I, Takeuchi T, Itohara S, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Furuichi T, Hensch TK, Yamakawa K. Nav1.1 localizes to axons of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons: a circuit basis for epileptic seizures in mice carrying an Scn1a gene mutation. J Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5903–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer IE, Nabbout R. SCN1A-related phenotypes: Epilepsy and beyond. Epilepsia. 2019, 60, S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lange IM, Koudijs MJ, van 't Slot R, Gunning B, Sonsma ACM, van Gemert LJJM, Mulder F, Carbo EC, van Kempen MJA, Verbeek NE, Nijman IJ, Ernst RF, Savelberg SMC, Knoers NVAM, Brilstra EH, Koeleman BPC. Mosaicism of de novo pathogenic SCN1A variants in epilepsy is a frequent phenomenon that correlates with variable phenotypes. Epilepsia. 2018, 59, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahn AD, Behr ER, Hamilton R, Probst V, Laksman Z, Han HC. Brugada Syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugada R, Campuzano O, Sarquella-Brugada G, Brugada J, Brugada P. Brugada syndrome. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014, 10, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, Fontaine G, Gear K, Hauer R, Nava A, Picard MH, Protonotarios N, Saffitz JE, Sanborn DM, Steinberg JS, Tandri H, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Tsatsopoulou A, Wichter T, Zareba W. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010, 31, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).