Submitted:

30 March 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

- What are the needs in long-term follow-up of cancer survivors?

- Are there socio-demographic differences in the needs (e.g. age, gender, marital status, income, location, etc.)?

- Are the needs greater in the transition phase (directly after acute treatments)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Study design: Systematic reviews

- Published in peer-review journals

- Languages: English, French and German

-

Focusing on cancer survivors

- o

- all kinds of cancer

- o

- male or female

- o

- curative intent

- Studies from high-income countries

- Other study designs, conference proceedings (in the absence of a full-text paper)

- Publications older than 2011

- Focusing on cancer survivors < 18 years old (at diagnosis)

- Time since diagnosis < 2 years

- Studies focusing on specific supportive care needs (e.g. physiotherapy)

- Studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC)

- Focusing on the indigenous population of high-income countries (HIC)

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.4. Data Charting Process

2.5. Data Items

- Source: title, author(s), year, journal, DOI / ISBN

- Characteristics of the study: number of included articles, objectives, database consulted, inclusion / exclusion criteria, bias, results of the quality appraisal

- Population: age, gender, cancer type, number of participants

- Concept: domains of needs

- Context: country, period (of the studies), setting

- Results: needs, unmet needs, conclusion, recommendation for screening tool, influence of the comorbidities, influence of socio-demographical factors, information about the transitional phase

2.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.7. Synthesis of the Results

3. Results

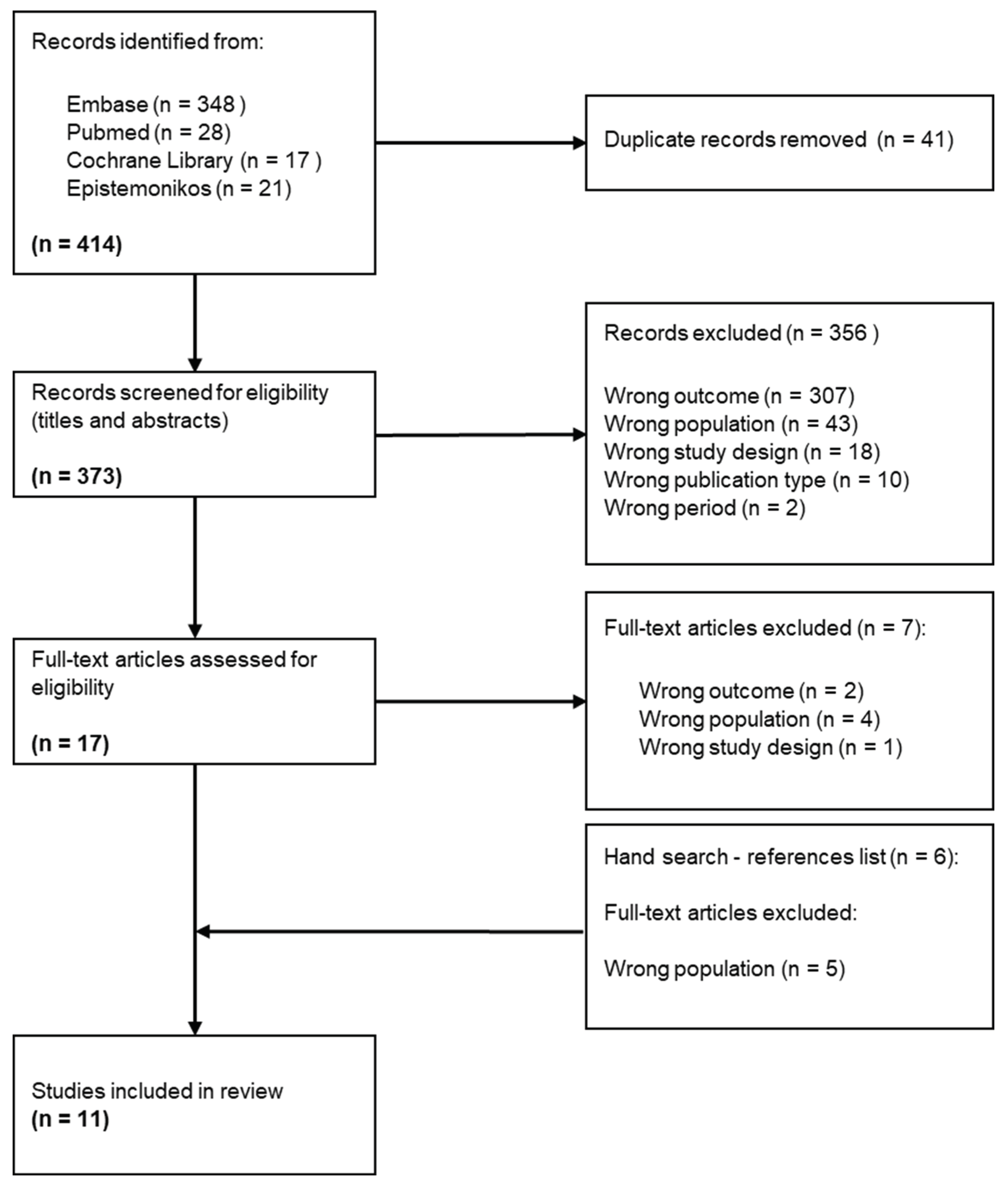

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

1.2. Critical Appraisal within Sources of Evidence

1.3. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

1.4. Synthesis of Results

3.1. Health-Related Information

3.2. Health System

3.3. Mental

3.4. Practical

3.5. Relationship

3.6. Physical

3.7. Socio-Demographic Factors

3.8. Transition Phase

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Review Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Cancer Tomorrow. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- WHO Number of Deaths Caused by Selected Chronic Diseases Worldwide as of 2019 (in 1,000) [Graph]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/265089/deaths-caused-by-chronic-diseases-worldwide/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- WHO World Factsheet. In: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/39-all-cancers-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Ligue suisse contre le cancer Ligue Suisse Contre Le Cancer. Le Cancer En Suisse : Les Chiffres. Available online: https://www.liguecancer.ch/a-propos-du-cancer/les-chiffres-du-cancer/-dl-/fileadmin/downloads/sheets/chiffres-le-cancer-en-suisse.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Mullan, F. Seasons of Survival: Reflections of a Physician with Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 1985, 313, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Merry, B.; Miller, J. Seasons of Survivorship Revisited. The Cancer Journal 2008, 14, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.K. Transition to Cancer Survivorship: A Concept Analysis. Advances in Nursing Science 2018, 41, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbez, B.; Rollin, Z. Sociologie Du Cancer. Edition, La.; Collection Repères: Paris, 2016; ISBN 978-2-7071-8286-9. [Google Scholar]

- Firkins, J.; Hansen, L.; Driessnack, M.; Dieckmann, N. Quality of Life in “Chronic” Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Delivering Cancer Survivorship Care. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C, 2006; ISBN 978-0-309-09595-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2020.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, V.; Laan, E.T.M.; den Oudsten, B.L. Sexual Health-Related Care Needs among Young Adult Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.Y.; Delfabbro, P. Are You a Cancer Survivor? A Review on Cancer Identity. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2016, 10, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I. Take Care When You Use the Word Survivor. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal 2019, 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, A.; Feder, G.; MacPherson, H.; Little, P.; Mercer, S.W.; Sharp, D. Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews of Complementary Medicine for Musculoskeletal and Mental Health Conditions. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotronoulas, G.; Papadopoulou, C.; Burns-Cunningham, K.; Simpson, M.; Maguire, R. A Systematic Review of the Supportive Care Needs of People Living with and beyond Cancer of the Colon and/or Rectum. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2017, 29, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, R.; Kotronoulas, G.; Simpson, M.; Paterson, C. A Systematic Review of the Supportive Care Needs of Women Living with and beyond Cervical Cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2015, 136, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, Y.G.; Alhashemi, A.; Fazelzad, R.; Goldberg, A.S.; Goldstein, D.P.; Sawka, A.M. A Systematic Review of Unmet Information and Psychosocial Support Needs of Adults Diagnosed with Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroševič, Š.; Prins, J.B.; Selič, P.; Zaletel Kragelj, L.; Klemenc Ketiš, Z. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Unmet Needs in Post-treatment Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2019, 28, e13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, L.; Wittrup, I.; Væggemose, U.; Petersen, L.K.; Blaakaer, J. Life After Gynecologic Cancer—A Review of Patients Quality of Life, Needs, and Preferences in Regard to Follow-Up. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2013, 23, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, R.A.; Heins, M.J.; Korevaar, J.C. Health Care Needs of Cancer Survivors in General Practice: A Systematic Review. BMC Fam Pract 2014, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.Y.S.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.C.; Young, J.M.; Kao, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Butow, P. Colorectal Cancer Survivorship: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisy, K.; Langdon, L.; Piper, A.; Jefford, M. Identifying the Most Prevalent Unmet Needs of Cancer Survivors in Australia: A Systematic Review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2019, 15, e68–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, E.; Vlerick, I.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Pattyn, P.; Van de Putte, D.; van Ramshorst, G.H.; Geboes, K.; Van Hecke, A. Experiences and Needs of Patients with Rectal Cancer Confronted with Bowel Problems after Stoma Reversal: A Systematic Review and Thematic-Synthesis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2021, 54, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruk, S.R.; Butow, P.; Mesters, I.; Boyle, T.; Olver, I.; White, K.; Sabesan, S.; Zielinski, R.; Chan, B.A.; Spronk, K.; et al. Psychosocial Well-Being and Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Patients and Survivors Living in Rural or Regional Areas: A Systematic Review from 2010 to 2021. Supportive Care in Cancer 2021, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I. Supportive Care Framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal 2008, 18, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.; Griffin, G.; Farrell, V.; Hauck, Y.L. Gaining Insight into the Supportive Care Needs of Women Experiencing Gynaecological Cancer: A Qualitative Study. J Clin Nurs 2020, 29, 1684–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, C.; Peytremann Bridevaux, I.; Eicher, M. The Swiss Cancer Patient Experiences-2 (SCAPE-2) Study: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Survey of Patient Experiences with Cancer Care in the French- and German-Speaking Regions of Switzerland 2023.

- Moore, K.A.; Ford, P.J.; Farah, C.S. “I Have Quality of Life...but...”: Exploring Support Needs Important to Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2014, 18, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan Cancer Support Cancer Self-Help and Support Groups. Available online: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/get-help/emotional-help/local-support-groups (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Chambers, S.K.; Hyde, M.K.; Laurie, K.; Legg, M.; Frydenberg, M.; Davis, I.D.; Lowe, A.; Dunn, J. Experiences of Australian Men Diagnosed with Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.E.; Doroudi, M.; Yabroff, K.R. Financial Hardship. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, H.R.; Durbin, S.; Huang, C.X.; Johnson, S.F.; Nayak, R.K.; Zahner, G.J.; Peppercorn, J. Financial Toxicity in Cancer Care: Origins, Impact, and Solutions. Transl Behav Med 2021, 11, 2043–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleaume, C.; Bousquet, P.-J.; Joutard, X.; Paraponaris, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Vernay, P. Situation Professionnelle Cinq Ans Après Un Diagnostic de Cancer. In La vie cinq ands après diagnostic de cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa), Ed.; 2018; pp. 174–201.

- Alleaume, C.; Bousquet, P.-J.; Joutard, X.; Paraponaris, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V. Trajectoire Professionnelle Après Un Diagnostic de Cancer. In La vie cinq ans après un diagnostic de cancer ; Institut National du Cancer (INCa), Ed.; 2018; pp. 202–221.

- Von Ah, D.; Duijts, S.; van Muijen, P.; de Boer, A.; Munir, F. Work. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ancellin, R.; Ben Diane, M.-K.; Bouhnik, A.-D.; Mancini, J.; Menard, E.; Monet, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Sarradon-Eck, A. Alimentation et Activité Physique. In La vie cinq ans après un diagnostic de cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa), Ed.; 2018; pp. 278–297.

- Deutsch, A.; Monet, A.; Peretti-Watel, P. Consommation de Tabac et d’alcool. In La vie cinq ans après un diagnostic de cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa), 2018; pp. 298–311.

- Han, X.; Robinson, L.A.; Jensen, R.E.; Smith, T.G.; Yabroff, K.R. Factors Associated With Health-Related Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.E.; Jones, J.; Syrjala, K.L. Comprehensive Healthcare. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, J.S.; Riley, K.E.; Dhingra, L.K. Smoking. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Mollica, M.A.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Mayer, D.K.; Shulman, L.N.; Geiger, A.M. Developing a Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework: Implications for Clinical Care, Research and Policy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, B.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, C.; Han, L. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2020, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thong, M.S.Y.; van Noorden, C.J.F.; Steindorf, K.; Arndt, V. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Causes and Current Treatment Options. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2020, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperisen, N.; Cardinaux-Fuchs, R.; Schneider-Mörsch, B.; Stoll, S.; Haslbeck, J. Onkologiepflege. Kleinandelfingen 21, pp. 12–14. 20 March.

- Riley, S.; Riley, C. The Role of Patient Navigation in Improving the Value of Oncology Care | Journal of Clinical Pathways. Journal of Clinical Pathways 2016, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bellas, O.; Kemp, E.; Edney, L.; Oster, C.; Roseleur, J. The Impacts of Unmet Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Survivors in Australia: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022, 31, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Supportive, Survivorship and Palliative Care. WHO REPORT ON CANCER: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020; pp. 94–97. ISBN 978-92-4-000129-9. [Google Scholar]

- National comprehensive cancer network Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects 2020.

- Jefford, M.; Karahalios, E.; Pollard, A.; Baravelli, C.; Carey, M.; Franklin, J.; Aranda, S.; Schofield, P. Survivorship Issues Following Treatment Completion-Results from Focus Groups with Australian Cancer Survivors and Health Professionals. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2008, 2, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. TARGET ARTICLE: “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. ” Psychol Inq 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Ganz, P.A. Life after Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer in Adulthood: Contributions from Psychosocial Oncology Research. American Psychologist 2015, 70, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the studies | Context | Population | Limitations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim of the studies | Number of included articles | Period of analysis (of the studies) | Countries | Number of participants (range) | Gender | Cancer type | ||

| Dahl et al. (2013) [22] | To investigate knowledge on the quality of life after cancer, which factors could be predictors, and knowledge on gynecological cancer patients' needs and preferences regarding follow-up | 57 | 1995-2012 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Gynecological | ▪No limitations are reported ▪Little or no information about the target group and setting ▪Prisma flow chart is not available ▪Only capture English research |

| Hoekstra et al. (2014) [23] | To report how adult cancer survivors describe their care needs in the general practice environment | 15 | 1990-2012 | UK, USA, Canada, Denmark, Italy | 970 (6 - 431) | Men, women | Bladder, prostate, breast, colorectal, head and neck, lung, melanoma, testis, gynecological, bowel, hematological, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Hodgkin's, gastrointestinal, unknown / other | ▪Use of only 3 databases for the search ▪Delay between the search and the publication ▪Possibly under representation of all existing needs |

| Hyun et al. (2016) [20] | To examine the unmet information needs and the unmet psychosocial support needs of adult thyroid cancer survivors | 7 | 2008-2016 | USA, Canada, Netherlands, South Korea, | 6,215 | Majority of women | Thyroid | ▪Level of agreement between reviewers was limited ▪No stratification of needs according to important variables (clinic-histopathologic sub-group, life stage, or disease status in response to treatment) ▪Only capture English research |

| Kotronoulas et al. (2017) [18] | To synthesize evidence in relation to the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and / or rectum | 45 | 1996-2016 | UK, Australia, other (not specified) | 10,057 (5 - 3011) | "Men (64.5%) Women (35.5%)" | Colon and / or rectum | ▪Mixed patient samples ▪No grey literature researches ▪Limitations due to the tool used for appraising the methodological quality ▪Only capture English research |

| Lehmann et al. (2021) [13] | To identify the prevalence of sexual health-related care needs and the types of needs that should be addressed by providers | 35 | 2004-2019 | Denmark, USA, Germany, Canada, Australia, Netherlands | 5,938 (8-879) | Majority of women | Breast, testicular, gynecological, | ▪ Focus on need addressed by professionals ▪ Risk of biased assessment of all the included studies. ▪Only capture English research |

| Lim et al. (2021) [24] | To synthesize the current body of qualitative research on colorectal cancer survivorship as early as the immediate post-operative period, and to compare the experiences of early-stage and advanced colorectal cancer survivors | 81 | 2006-2019 | USA, Europe, UK, Australia, Asia, Canada, New Zealand, Middle East | Not reported | Not reported | Colon and / or rectum | ▪ Search was not exhaustive ▪ Subjective inclusion of articles due to differing definition of "survivorship" and lacked clarity on participants "survivorship status" ▪ Deviation from the original PROSPERO protocol ▪Only capture English research |

| Lisy et al. (2019) [25] | To identify the most prevalent unmet needs of cancer survivors in Australia and to identify demographic, disease, or treatment-related predictors of unmet needs | 17 | 2007-2018 | Australia | Not reported | Not reported | Gynecological, breast, brain, hematological, endometrial, prostate, testicular, various | ▪ Data are limited by the measure used to assess unmet needs ▪ Review does not include a proportionate distribution of cancer types in Australia ▪ Study selection and quality appraisal were conducted primarily by one reviewer ▪ Studies included in this narrative review were equally weighted regardless of sample size |

| Maguire et al. (2015) [19] | To synthesize evidence with regard to the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer | 14 | 1990-2013 | USA, Canada, UK, Indonesia, South Korea, Nigeria, Thailand | 1,414 (10 - 968) | Women | Cervical | ▪ Search was limited to the most common databases ▪ No grey literature research ▪Only capture English research |

| Miroševič et al. (2019) [21] | To determine the prevalence and identify the factors that contribute to higher levels of the unmet needs. To identify the most commonly unmet needs and those factors that contribute to higher levels of unmet needs in each domain separately | 26 | 2007-2015 | Australia, UK, USA, China, Singapore, Canada, Ireland, Netherlands, Iran, South Korea | 10,533 (63 - 1668) | Men, women | Breast, gynecological, hematological, head and neck, colorectal, endometrial, various | ▪Most of the included studies were cross-sectional ▪Included studies lacked information (prevalence, factors associated with specific domains, stage of cancer at diagnosis) ▪Homogenous sample in several studies ▪Only capture English research |

| Pape et al. (2021) [26] | To describe the experiences and needs of patients with rectal cancer confronted with bowel problems after stoma reversal. | 10 | 2006-2021 | UK, USA, China, Taiwan, Sweden, Netherlands | 156 (5 - 36) | "Men (approx. 58%) Women (approx. 42%)" | Rectal with Stoma reversal | ▪ Some studies do not reach data saturation ▪ Small sample for some studies ▪ Some studies were performed as single centre studies ▪ Most of the studies did not report on the severity of participants' bowel problems |

| Van der Kruk et al. (2021) [27] | To review levels of psychosocial morbidity and the experiences and needs of people with cancer and their informal caregivers, living in rural or regional areas | 65 | 2010-2021 | Australia, USA, Canada, Europe | Not reported | Not reported | Breast, hematological, colorectal, lung, head & neck, gynecological, prostate, myeloma, various | ▪ Included studies have different definition of "rurality" ▪ Different methodological approach and data sources of the studies ▪ No meta-analysis was conducted due to the heterogeneity of the studies ▪ Findings are conceptual rather than statistical ▪ Only capture English research |

| Authors (year) | Identified needs (domains) | Socio-demographic factors associated with needs | Greater needs in the transition phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoekstra et al. (2014) [23] | • Medical • Psychosocial • Information • Proactive contact • Other |

- | • Proactive approach of the general practitioner |

| Hyun et al. (2016) [20] | Information on: • Thyroid cancer • Thyroid cancer treatment • Diagnostic tests • Aftercare • Psychosocial issues • Coordination of care • Complementary and alternative medicine |

- | - |

| Kotronoulas et al. (2017) [18] | • Physical / cognitive • Psychosocial / emotional • Family-related • Social / societal • Interpersonal / intimacy • Practical / daily living • Information / education • Health system / patient-clinician communication needs |

• Gender • Age • Education level • Employment status • Family support |

• Better coordination among healthcare professionals • Psychological support for feeling of abandonment |

| Lehmann et al. (2021) [13] | Sexual health-related care / Sex-related: ▪ Information ▪ Practical / emotional support ▪ Communication |

• Age • Gender • Relationship status |

- |

| Lim et al. (2021) [24] | ▪ Physical symptoms ▪ Functional limitations ▪ Psychosocial impacts ▪ Financial impacts ▪ Interaction with healthcare system ▪ Coping ▪ Positive outcome |

- | • Long-term support • Support for feeling of abandonment by the healthcare team |

| Lisy et al. (2019) [25] | • Psychosocial • Supportive care • Physical |

• Age • Education level • Employment status • Social support |

• Support for anxiety about leaving the hospital system |

| Maguire et al. (2015) [19] | • Physical • Psychological / emotional • Social • Interpersonal / intimacy concerns • Health system / information • Patient-clinician communication • Spiritual / existential |

- | • Support about intimate relationships • More information regarding prognosis • Better communication with the clinical team |

| Miroševič et al. (2019) [21] | • Psychological • Physical and daily living, • Relationship • Patient care • Information |

• Age • Employment statusa • Education levela • Social supporta a weak evidence |

• Support for fear of cancer recurrence • Better information • Reassurance about being treated |

| Pape et al. (2021) [26] | Before surgery (stoma reversal): • Information before surgery • Sources of information After surgery: • Management and coping • Support from peers and the environment • Support of the healthcare professionals |

- | - |

| Van der Kruk et al. (2021) [27] | • Financial and travel issues • Accessibility to care • Psychological • Information |

• Location (urban vs rural) • Education level • Age • Income |

- |

| Domains of needs | Definition | Categories of needs | Examples of challenges | Number of studies reporting these needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related information | Need to receive and process adequate information on all types of subjects to meet certain objectives | Access | Lack of information (all kinds of information), quality and delivery of information | 10 |

| Education | Difficulties to process information, comprehension, and quality assessment | |||

| Health system | Need to access a personalized, comprehensive, and integrated care and support pathway to reduce or treat the consequences of the disease and / or treatments. | Healthcare professionals | Lack of knowledge of the unique needs of rural survivors by medical staff located in metropolitan treatment centers, on-going patient-clinician contact, post-operative follow-up (hospital doctor) or post-treatment follow-up (specialist nurse), helping with common (late) treatment effect, initialization of discussions about sexual health by providers, empathic and sensitive discussion on sexual health, overcome taboos, enough time to discuss sensitive matters | 10 |

| Health and supportive care | Coordination of health care services (primary and secondary), access to counselling / support groups, access to complementary / alternative medicine, gap in supportive care, medical help / treatment for non-cancer related problems, general preventative healthcare, access and continuity of care, comprehensive care, regular monitoring of needs, navigation in health system | |||

| Mental | Supportive care needs to reduce emotional, existential, interpersonal and / or psychic health conditions, due to illness and / or treatment, that disrupt a person's behavior or reasoning | Emotional | Deal with altered body image, appearance (attractiveness, self-image, desirability, femininity), emotional health | 9 |

| Existential | Fear of cancer recurrence, uncertainty, adversity, lifestyle changes, worries about the future | |||

| Interpersonal / intimacy | Changes in sexuality, coping with sexual dysfunction, lack of sexual desire, anxiety about sexual intercourse, feeling to be forced to fulfill the partner's sexual desires (cultural pressure and expectation) | |||

| Psychic | Stress, feeling of abandonment after treatment, anxiety, distress, depression | |||

| Practical | Need for support to limit the impact of the disease and / or treatment on daily life | Daily activities | Not being able to do usual things, transportation, identification, and integration of health behaviors | 7 |

| Financial impact | Financial well-being, worry about earning money, fighting financial toxicity | |||

| Work | Return to work, adapting work to new capacities (position, schedule, workload, etc.), change of professional activity, reactions of colleagues / leaders | |||

| Relationship | Need for support to reduce or deal with the consequences of the illness and / or treatments that disrupt interactions with the family and the social environment | Family | Support of family for its own worries, family's future, worry about partners and family | 6 |

| Social | Embarrassment in social situation, relationship with others, lack of practical and emotional support from peers and the environment, difficulties and tensions in relationships, isolation, social role change, social desirability | |||

| Physical | Supportive care needs to alleviate or treat the physical and cognitive consequences of the disease and / or treatments | Body | Fatigue / lack of energy, pain, physical problems, dysfunction, sleep loss, urinary incontinence, bowel dysfunction, difficulty breathing, infertility, hormone changes, loss of strength, nausea-vomiting, neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, skin irritation, weight changes, infected or bleeding wound, mouth- or eye-related, physical examination, managing side-effects (physical symptoms) | 6 |

| Cognitive | Memory loss, difficulty concentrating or cognitive dysfunction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).