1. Introduction

The mental capacity constitutes a core element to enable the full participation of patients in their clinical pathways and the consolidation of the therapeutic alliance between them and healthcare professionals (HCPs) (Mandarelli et al., 2014). Its foundations are based on cognitive autonomy and the integrity of decision-making abilities, which collectively allow patients to make free, conscious, and informed choices (Santurro et al., 2017).

In the healthcare context, mental capacity is primarily based on the competence to complete informed consent regarding diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, to participate in research, and to establish advanced directives (Turillazzi et al., 2014)

The difficulties associated with judgments on mental capacity determined solely by clinical assessments (Curley et al., 2022) have led to the development of various standardized assessment tools over the years (Lamont et al., 2013).

In mental health, instruments have been developed for the assessment of treatment consent (Grisso et al., 1997), research participation (Kreutzer et al., 2011; WONG, 2002), and advanced directives (Srebnik et al., 2004).

Most of these tools consist of subscales for assessing the four fundamental dimensions that have been identified as determinants of decisional capacity (Appelbaum, 2010), namely the abilities to:

i) comprehend the pertinent components of one's medical condition and assimilate all information relevant to decisions (Understanding); ii) utilize this information in evaluating its implications in alignment with personal values, beliefs, and expectations, including an assessment of potential consequences (Appreciation); analyze available information by structuring it in a logical and rational sequence, involving the evaluation of pros and cons, and assess potential therapeutic alternatives (Reasoning); communicate a decision or identify a designated individual who can assist in making the most suitable decision (Expression of a choice).

Decisional capacity is subject to change over time, and medical procedures demanding consent over extended periods necessitate recurrent assessments (Buchanan, 2004). These changes may stem from physiological processes, like aging (Tannou et al., 2020), or they could be shaped by multifaceted factors in pathological conditions, as evidenced in serious mental illnesses (SMI) (Stroup et al., 2005).

Certain symptomatic conditions, such as those occurring during the acute phases of affective or psychotic disorders, have the potential to hinder the competence to consent. This may also be exacerbated by exposure to stressful situations, such as hospitalization, or the administration of higher medication doses (Lepping et al., 2015).

For individuals with SMI, even the stable phases can, however, be characterized by mental incapacity due to cognitive impairment that affects the ability to concentrate, understand, assimilate information, and maintain consistency in decision-making (Gupta & Kharawala, 2012).

Specifically, for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, psychopathological status, insight, and cognitive performance can prove pivotal in influencing their decision-making processes (Jeste et al., 2006; Misra et al., 2008; Spencer et al., 2017).

Regarding clinically stable outpatients with schizophrenia, studies have found an overlap with the competence to consent to treatment or hospitalization when compared to the general population (Jeste et al., 2006; Lepping et al., 2015).

For these patients, additional distinctions have been observed in the ability to give consent for participation in research programs compared to treatment, particularly during acute phases of the illness, which are present in only approximately half and one-third of the sample, respectively (Spencer et al., 2018).

A meta-analysis conducted by Wang et al. (2017) demonstrated that particularly in the elderly, individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were significantly more prone to experiencing impaired decision-making capacity across all four core domains of competence when compared to healthy controls (Wang et al., 2017). Moreover, this was evident both for clinical research and treatment consent.

For patients with bipolar disorder, the available data is very limited, conflicting, and inconclusive (Director, 2023; Klein et al., 2019).

Palmer et al. compared the decisional capacity of three groups: one consisting of outpatients with bipolar disorder, another with schizophrenia, and a third comprising healthy subjects (Palmer et al., 2007). Both groups of patients exhibited a current minimal psychopathological status.

There were no differences between the group of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in all dimensions of capacity. The group of healthy subjects reported significantly higher scores in Understanding compared to both patient groups, and in Appreciation exclusively compared to the group of patients with schizophrenia. There were no significant correlations between scores of manic symptomatology and competence dimensions, while depressive symptomatology showed a negative correlation with the Reasoning score.

The study by Klein et al. involving patients with bipolar disorder highlighted a correlation between the severity of psychotic symptomatology and poorer performance on the Understanding and Appreciation dimensions (Klein et al., 2019). Instead, there was a reverse correlation between depressive symptoms and scores in Understanding, Appreciation, and Reasoning. However, it is worth noting that this data remains somewhat controversial (Cohen et al., 2004; Hindmarch et al., 2013).

Koukopoulos et al. found that patients hospitalized for a manic/hypomanic episode scored worse than outpatients in Understanding, Reasoning, and Expressing a choice, but not in Appreciating (Koukopoulos et al., 2020). Outpatients in a phase of clinical stability were more capable in the dimension of Understanding the characteristics of an alternative advance treatment. General cognitive functioning positively correlated with scores in all four dimensions of competence, whereas manic symptomatology showed an inverse correlation and depressive symptomatology correlated only with Appreciating scores.

Given the challenges posed by inconclusive current evidence, the purpose of this study was to assess the presence of differences in decision-making capacity among groups of patients with bipolar disorder and a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (primarily schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder). If differences exist, it is presumable that phase-related factors, primarily linked to psychopathological status, may influence decision-making capacity. However, in the case of a lack of differences, especially under conditions of clinical remission, as per our hypothesis, cognitive aspects should be considered predominant and potentially compromised in both groups.

2. Materials and Methods

Our quantitative systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Literature Search

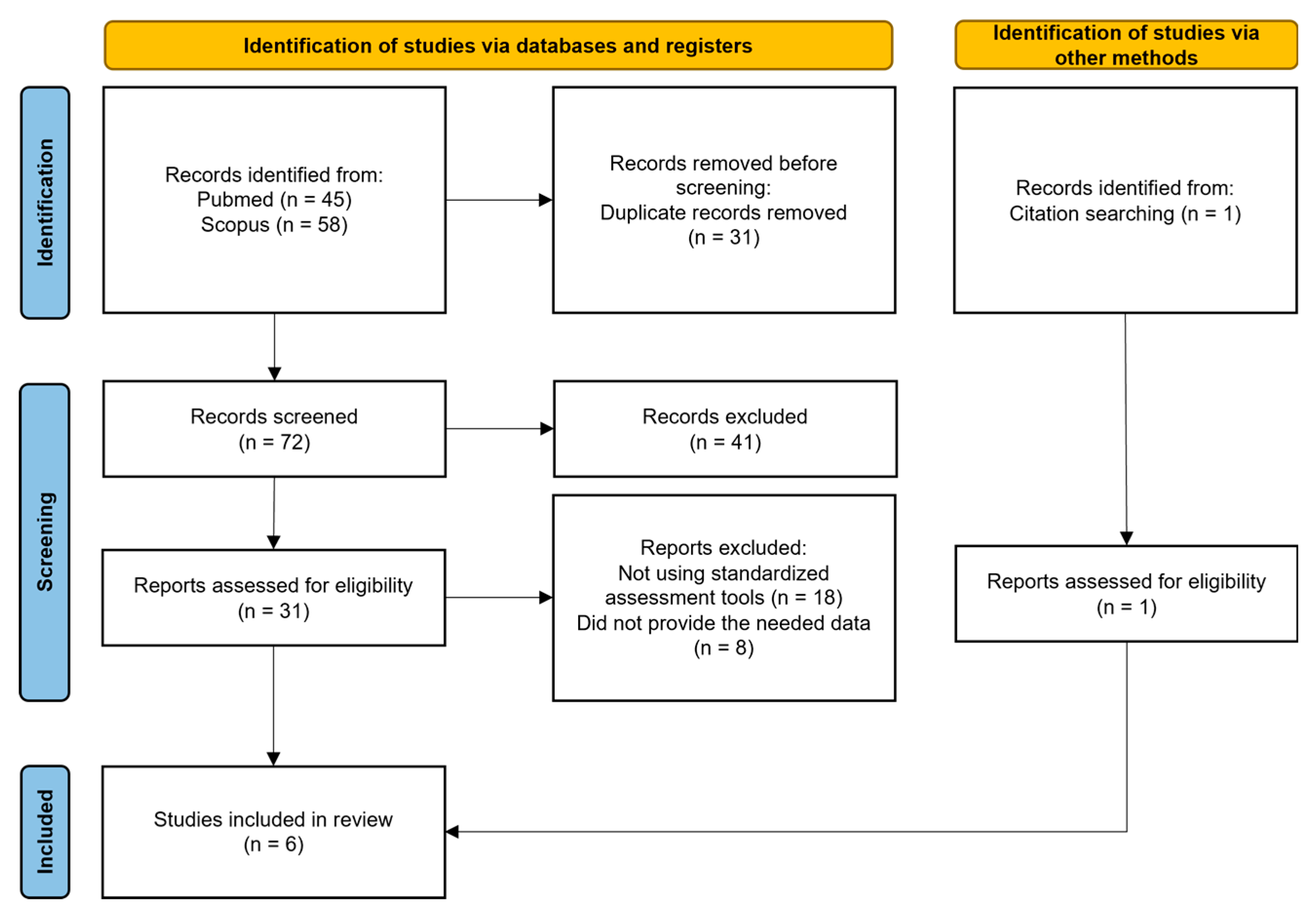

The process of identifying eligible studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis is shown in is outlined in

Figure 1.

Potential articles used in the meta-analysis were identified from Scopus, Pubmed, and Google Scholar. No temporal filters were applied. For the search on Scopus, the keywords used were “TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (schizhophreni*) AND/OR TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (bipolar*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (competen*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (consen*)”. For the search on PubMed, the keywords used were “((schizhophreni*) AND/OR (bipolar*)) AND (competen*) AND (consen*) any field”. Emerging reviews and reference lists of the retrieved papers were also manually searched by two investigators (D.M. and M.L.). Google Scholar was manually inspected, specifically looking for studies utilizing standardized tools for the assessment of capacity (e.g., MacCAT-T, MacCAT-CR, SICIATRI, SICIATRI-R, CAT-PAD).

Initially, eligibility screening was conducted on the abstracts of papers identified through the described procedures. Papers that successfully underwent this screening process were subsequently subjected to a more comprehensive assessment for potential inclusion in our study, involving a thorough examination of the full text. Two independent reviewers (D.M. and M.L.) evaluated the reports and extracted data; any disagreements were resolved by a third author (either P.F. or V.F.).

A comprehensive approach, deliberately keeping eligibility criteria broad, was adopted. The inclusion criteria specifically targeted cross-sectional studies where standardized tools were utilized to measure the capacity to provide consent, involving patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Papers not written in English or not published in peer-reviewed journals were excluded.

The protocol for this review has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO registration number CRD42024502141).

2.2. Data Extraction

A standardized form was employed to extract data from the included studies, aiding in study quality and evidence synthesis. Extracted information encompassed the study's focus; participant characteristics such as age, sex (expressed as percentages of female participants), years of education, diagnosis, stage (acute vs. chronic), and duration of the illness; baseline symptom severity; the type of assessment tools used to determine the capacity to provide consent; and the information required for the assessment of the risk of bias. Extraction was independently conducted by two reviewers (D.M. and M.L.) in duplicate. A third reviewer (V.F.) was consulted when needed.

2.3. Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (D.M and M.L.) using the Newcastle

-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies (Moskalewicz & Oremus, 2020; Wells et al., 2000). This scale assigns a maximum of 10 “stars” for the lowest risk of bias. Three areas are explored: 1) Study sample selection (5 stars); 2) comparability of groups (2 stars); 3) outcomes (3 stars). Any disagreements were resolved through comparison between the two reviewers. Four studies scored 8 stars, indicating good quality (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; Cairns et al., 2005; López-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Mandarelli et al., 2018), while two studies scored 6 stars, which still reflects satisfactory quality (Palmer et al., 2007; Srebnik et al., 2004). The results are summarized in

Table 1.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Differences between patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorder were investigated concerning the main domains constituting the competence assessment scales, namely Understanding, Appreciation, Reasoning, and Expression of a choice. These outcomes were further explored through metaregressions and subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Regarding general psychopathology, in cases where studies reported multiple rating instruments for symptoms, only one scale per study was selected. Priority was given to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall & Gorham, 1962).

2.5. Meta-Analysis Procedure

We conducted four meta-analyses to examine the differences between the two studied groups of patients with bipolar disorder (hereafter referred to as the 'BD group') and schizophrenia spectrum disorder (hereafter referred to as the 'SZ group') in the four dimensions considered by the literature as constitutive of decisional capacity in the healthcare field, namely Understanding, Appreciation, Reasoning, and Expression of a choice.

Effect sizes were computed utilizing means and standard deviations (SD). Since scores on the decisional capacity subscales were continuous data obtained from different scales (i.e., CAT-PAD, MacCAT-T, MacCAT-CR), but mostly investigated similar domains (i.e., understanding, appreciation, reasoning), and given the small sample size of patients found in the selected studies, Hedges’s g with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was chosen to analyze the studies (Crocetti, 2016).

The mean effect size for the group of studies was calculated by pooling individual effect sizes using a random-effect model instead of a fixed-effect model, given that the selected studies were not identical (i.e., did not have either an identical design or target the same population).

Values of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 for Hedges’ g were considered indicative of small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Brydges, 2019).

Heterogeneity among studies in each meta-analysis was assessed using the chi-squared statistic (Q), I2, and Tau2. Substantial heterogeneity was considered if I2 exceeded 30%, and either Tau2 was greater than zero or there was a low p-value (less than 0.10) in the chi-squared statistic (Q) test for heterogeneity. I2 measures the proportion of heterogeneity to the total observed dispersion and is not influenced by low statistical power. We considered I2 values as low ranging from 0% to 25%, intermediate from 25% to 50%, moderate from 50% to 75%, and high when ≥75% (Higgins et al., 2003). A subgroup analysis was performed on studies sharing the same decisional capacity instrument and the same psychological status of stable conditions. We deemed p<0.05 (two-tailed) as statistically significant. The risk of publication bias was evaluated through visual examination of funnel plots and a statistical test of asymmetry (Egger test)(Egger et al., 1997).

The meta-analysis was carried out using the software ProMeta 3.

3. Results

We found 31 potentially eligible studies from 103 records obtained from the selected databases and 1 after references screening. After reviewing the full content of the papers, 26 papers were excluded for various reasons: 18 did not examine the capacity to consent to treatment or clinical research, and 8 did not supply the needed data. Regarding the exclusion of these articles, we specify that initially we identified 9 articles worthy of inclusion in our meta-analysis as they provided an assessment of competence to consent in both patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder and a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. However, the available information within the articles themselves did not initially allow for obtaining the necessary data for our study. For this reason, a personal communication was sent individually to the corresponding authors of each article, along with a specially designed data sheet for each study, with the aim of collecting the required data. Only one author (Prof. Hotopf) kindly responded and made the requested data available (Cairns et al., 2005). Therefore, out of these 9 articles, we were forced to exclude 8, while only 1 was included.

Finally, 6 articles were included in our meta-analysis. All of them compared the domains of Understanding, Appreciation, and Reasoning, while only three reported the results of the Expression of a choice.

3.1. Studies, Participants, and Treatment Characteristics

All the six studies selected in this meta-analysis have been published in peer-reviewed journals and were all conducted at the national level: three in the USA (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; Palmer et al., 2007; Srebnik et al., 2004), one in England (Cairns et al., 2005), one in Italy (Mandarelli et al., 2018) and one in Colombia (López-Jaramillo et al., 2016). The majority of these (four) were conducted at a multicenter level (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; López-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Mandarelli et al., 2018; Srebnik et al., 2004). Furthermore, all the studies included had a cross-sectional design. In addition, two studies aimed to validate a psychometric scale: López-Jaramillo et al. (2016) intended to validate and adapt the MacCAT-CR scale to the Spanish language, while Srebnik et al. (2004) aimed to validate a new instrument for assessing the decision-making capacity of psychiatric patients (CAT-PAD tool).

Regarding the recruitment of participants, four studies recruited patients anew (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018; Srebnik et al., 2004), while two studies enrolled participants from those already recruited for two larger studies (López-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2007).

Moreover, in two studies, patients were recruited from inpatients in psychiatric wards (Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018), while in the other four, participants were recruited from outpatient patients under the care of community mental health centers (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; López-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2007; Srebnik et al., 2004). The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in

Table 2.

Among the six studies, as assessment tools, one utilized the CAT-PAD (Srebnik et al., 2004), while three studies employed the MacCAT-T (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006; Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018) and two the MacCAT-CR (López-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2007).

The MacCAT-T is a semi-structured interview designed to assess key aspects of treatment-related decision-making, aligning with commonly applied legal standards for competence to consent to treatment (Grisso et al., 1997).

The subscales within the MacCAT-T evaluate understanding, which involves grasping information about the disorder and the main features of the treatment, as well as presumed associated risks and benefits (rated 0–6); appreciation, reflecting patients’ ability to comprehend their own diagnosis and treatment (rated 0–4); reasoning ability, encompassing consequential and comparative thinking, and logical consistency (rated 0–8); and the ability to clearly express a choice (rated 0–2).

The MacCAT-CR is a semi-structured interview that utilizes the same multidimensional capacity model as MacCAT-T but includes 21 items assessing the well-known four abilities related to competence, specifically in the context of consent to clinical research: understanding of purposes, procedures, potential benefits, risks, of the research project (rated 0–26); appreciation of the impact of participation in research on personal condition (rated 0–6); reasoning about the consequences of participation (range 0–8); and consistent expression of a choice (rated 0–2).

The Competence Assessment Tool for Psychiatric Advance Directives (CAT-PAD) is a tool designed to assess competence in completing a psychiatric advance directive (PAD). Despite some differences from the Mac-CAT scales, it similarly involves a series of disclosures of information representative of what is relevant for decisions about completing a PAD (Srebnik et al., 2004). The CAT-PAD consists of three subscales: Understanding (rated 0-20), Appreciation (rated 0-6), and Reasoning (rated 0-10), totaling 18 items. Its construct is similar to the MacCAT-T Alternative Treatment (AT) variant, which measures the ability to make a valid choice between two proposed alternative treatments, including the current one, in case of a possible future acute phase of illness (Koukopoulos et al., 2020).

In the overall analysis, a total of 189 patients were included for the 'BD group' and 324 for the 'SZ group' for the dimensions of understanding, appreciation, and reasoning, while for the dimension of expression of choice, which was investigated by only three studies (Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018; Palmer et al., 2007), 107 and 180 patients were respectively included.

More information are about the included studies are listed in

Table 3.

3.2. Competence to Consent

3.2.1. Understanding

For Understanding (

Table 4), the 'BD group' exhibited a slightly positive effect size (ES=0.09) but was not statistically significant (p=0.352). Despite some discrepancies in the direction of the effect sizes, there was no significant heterogeneity (Q (5) = 4.21, p = 0.519).

3.2.2. Appreciation

As seen in

Table 5, a small but significant effect size was obtained for Appreciation, with the 'BD group' performing slightly better than the 'SZ group' (ES=0.23, p=0.037). Also for this dimension there was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (Q(5)=6.73, p=0.242).

The worst results for the 'BD group' were obtained in the study by Cairns et al. (Cairns et al., 2005), with an ES= -0.04 (p=0.840). Anyway, this study included patients in an acute phase of psychopathological symptoms and with a particularly high severity index of illness (BPRS: 'SZ group'=48.3 ±10.6; 'BD group'=46.8 ±8.0).

A null effect size was also reported for the study by López-Jaramillo (López-Jaramillo et al., 2016). In this study, the compared groups had significantly different mean ages (p<0.001), with the ‘BD group’ (46.3 y ± 12.4) being older than the ‘SZ group’ (34.9 y ± 10.5).

Due to the limited availability of data, additional analysis was unable to identify which clinical, demographic, and illness-related variables were relevant in differentiating the 'BP group' and 'SZ concerning this dimension of capacity.

3.2.3. Reasoning

For Reasoning (

Table 6), the 'BD group' had a slightly positive effect size (ES=0.18) but was not statistically significant (p=0.236). The only study with a significant effect size (p=0.001) was that of Mandarelli

et al. (Mandarelli et al., 2018), with an ES=0.65. In this case, the studies exhibited significant heterogeneity (Q(5)=12.40, p = 0.030).

The only study to highlight a negative effect size (ES=-0.31, p=0.21) was that of Appelbaum & Redlich (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006). However, the results of this study showed a discrepancy between the data collected at one recruitment center (Durham), where the results of the two groups tended to overlap (SZ=6.94 ±1.61; BD=6.86 ±1.46), compared to another center (Worcester) (SZ=5.20 ±1.42; BD= 4.93 ±1.94).

The only study to show a negative effect size (ES=-0.31, p=0.21) was that of Appelbaum & Redlich (Appelbaum & Redlich, 2006). However, the statistical analysis conducted by the researchers did not reveal any significant difference between the scores of the 'BD group' compared to that of the 'SZ group'.

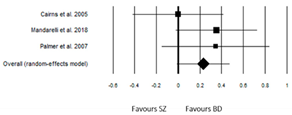

3.2.4. Expression of a choice

For Expression of a choice (

Table 7), the BD group had a slightly positive effect size (ES=0.23) but not significant (p=0.060). None of the studies had a significant effect size, and overall, they were not heterogeneous (Q(3)=1.80, p=0.407).

3.3. Sensitivity

To address the challenges associated with comparing studies utilizing various decisional capacity measures, we conducted a subgroup analysis involving 169 patients from the 'BD group' and 283 from the 'SZ group' across five studies. These studies employed similar instruments, such as MacCAT-T and Mac-CAT-CR. Notably, we excluded the study conducted by Srenbnik et al. (Srebnik et al., 2004), where the CAT-PAD scale was utilized. Our analysis focused on evaluating scores related to Understanding, Appreciating, and Reasoning (refer to supplementary material online S1 for details).

We did not perform this analysis with the Expression of a choice subscale as the two studies included (Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018; Palmer et al., 2007) were the same studies included in the overall analysis.

Utilizing random-effect models, the 'BD group' did not demonstrate significant differences compared to the 'SZ group' across any of the investigated competence dimensions. Specifically, for Understanding (ES = 0.04, 95% CI: -0.16 to 0.23, p = 0.707; Q (4) = 2.08, I² = 0.00, Tau² = 0.00), Appreciation (ES = 0.21, 95% CI: -0.04 to 0.46, p = 0.102; Q (4) = 6.50, p = 0.165, I² = 38.43%, Tau² = 0.03), and Reasoning (ES = 0.12, 95% CI: -0.21 to 0.45, p = 0.465, Q (4) = 11.05, p = 0.465, I² = 63.81%, Tau² = 0.09).

A subsequent subgroup analysis, including studies with patients in a clinical remission status, was conducted to minimize potential interference related to the acute psychopathological phase of illness. Hence, two studies, which recruited patients consecutively admitted to adult psychiatry wards (Cairns et al., 2005; Mandarelli et al., 2018) were excluded (refer to supplementary material online S2).

For this analysis as well, using random-effect models, the 113 patients of ‘BD group’ did not exhibit significant differences compared to the 175 patients of ‘SZ group’ across any of the investigated competence dimensions, that is Understanding (ES = 0.15, 95% CI: -0.10 to 0.41, p = 0.226; Q (3) = 3.24, p = 0.356, I² = 7.37, Tau² = 0.00), Appreciation (ES = 0.21, 95% CI: -0.04 to 0.46, p = 0.095; Q (3) = 3.17, p = 0.367, I² = 5.27%, Tau² = 0.00), Reasoning (ES = 0.08, 95% CI: -0,24 to 0.39, p = 0.632; Q (3) = 4.98, p = 0.173, I² = 39.79%, Tau² = 0.04).

For the Expression of a choice, only the study conducted by Palmer et al. remained (Palmer et al., 2007), comparing 31 patients of the 'BD group' to 31 patients of the 'SZ group’, and indicating no significant differences (ES = 0.35, p = 0.167, 95% CI: -0.15 to 0.84).

3.4. Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

Visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test did not show any publication bias for the subscales of Understanding (t = 1.27; p = 0.272), Appreciation (t = 0.03; p = 0.976), Reasoning (t = -0.64; p = 0.559), and Expression of a choice (t = -0.01; p = 0.992) in the comparison between ‘BD group’ and ‘SZ group’. The application of the trim-and-fill method, revealing symmetrical funnel plots for all four subscales of capacity, further suggested the consistency of the results. However, caution is warranted when excluding the presence of publication bias, given the limited statistical power of the test in a meta-analysis with a small number of trials (Crocetti, 2016; Egger et al., 1997).

4. Discussion

In our study, the primary objective was to investigate potential differences in decision-making capacity within the healthcare context among groups of patients with bipolar disorder and a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (primarily schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder). This addresses the existing gap in evidence in this field specifically for patients with bipolar disorder.

Several studies have focused on assessing patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (Hirakawa, 2023), while a literature review has revealed a shortage of studies primarily involving patients with bipolar disorder.

Regarding the latter group, there is evidence of an association between a lack of capacity measured with the MacCAT-T and manic symptomatology, poor insight, and symptomatic severity (Koukopoulos et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2009).

Our meta-analysis, conducted on all available studies comparing the two groups of patients, did not reveal differences except for Appreciation, where a significantly slightly better score in the 'BD group' emerged. However, in the sensitivity analysis conducted exclusively on studies involving patients in stable clinical conditions, this difference also became non-significant.

An in-depth analysis of one of the included studies, involving patients in an acute state (Mandarelli et al., 2018), revealed the presence of a significant difference between the two groups for some scores on the utilized assessment scale, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Specifically, the 'BD group' exhibited significantly higher scores for the excitement subscale, while the 'SZ group' showed significantly higher scores for the positive and negative symptoms subscales.

We hypothesize that in the study by Mandarelli et al. (2018), the prevalent psychotic symptomatology in the 'SZ group' may have negatively influenced the Appreciation, thus causing a significant divergence between the two groups of involved patients.

It is possible that psychotic symptomatology may have a greater impact on this dimension of the MacCAT-T even compared to excitatory symptomatology. However, this point remains controversial: for example, Owen et al. (2009) found an association between the lack of capacity measured with the MacCAT-T and manic episodes.

The absence of additional information on possible concurrent psychotic symptomatology (which may be present during manic episodes) determines difficulties in inferring whether the impact on capacity was predominantly due to psychotic or excitatory symptomatology.

Conflicting data are also reported regarding the correlation between Appreciation and negative symptomatology (Grisso et al., 1997; Raffard et al., 2021).

Positive symptomatology, on the other hand, has a well-known detrimental impact on the Appreciation (Palmer et al., 2007). This evidence could be mediated by the effect of psychotic symptoms on insight, as a negative correlation has been found between the latter and Appreciation and Reasoning (Capdevielle et al., 2009). The dearth data, however, has prevented the verification of this point in our analysis.

However, an interesting finding is represented by the absence of significant differences in Appreciation during stable phases of illnesses, suggesting that other elements may be at play, shared by both groups of patients.

Overall, under stable conditions, despite trends favoring the 'BD group' in every dimension of capacity, no significant differences emerged in our meta-analysis.

This data is quite surprising when considering that historically, the group of patients with bipolar disorders is believed to be more suitable for a restitutio ad integrum during symptomatic remission (Belmaker & Bersudsky, 2009).

However, more recent evidence has identified poor functioning as a key driver of disability in patients with bipolar disorder (Sanchez-Moreno et al., 2009), even during phases of symptomatic remission (Thomas et al., 2016), and the World Health Organization (WHO) has ranked this category as the 12th leading cause of disability worldwide (Chen et al., 2019).

Cognitive impairment, well-known for both patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, albeit with both qualitative and quantitative differences (Vaskinn et al., 2020), could be the preeminent factor compared to psychopathology during stable phases to explain the differences between the two diagnostic groups.

Studies employing comprehensive cognitive assessment batteries (Carpenter et al., 2000; Jeste et al., 2006; Moser et al., 2002; Stroup et al., 2005) have indicated a relationship between overall cognitive functioning and the capacity to provide consent. However, specific links between cognitive domains and the dimensions influencing capacity have not been clearly demonstrated.

Thus, this point could explain why, despite different cognitive impairments, patient groups with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders may share alterations in capacity.

Finally, it is worth noting that patients with bipolar disorder tend to exhibit cognitive trajectories that overlap with those of individuals with schizophrenia as they age, while, for the latter group, cognitive impairment emerges early, during early adulthood (Vöhringer et al., 2013).

This data could explain why, in the study by Palmer et al. (2007), age did not show effects on decisional capacity, unlike cognitive deficits, while in the study by Mandarelli et al. (2018), which assessed a younger sample, significant differences between the two groups emerged for Appreciation and Reasoning.

A final point concerns the subscale Expression of a choice, for which literature does not report differences between groups of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders compared to healthy subjects (Jeste et al., 2006; Palmer et al., 2007). However, this subscale has been noted as the least sensitive as defined by current assessment tools.

5. Limits

For our work, several limitations should be recognized. Firstly, the sample size in the included studies was relatively small. Secondly, diverse versions of the MacCAT were utilized across the studies, and one study employed a tool specifically designed for the assessment of advance directives. As a result, random-effects models were employed. Furthermore, there was no differentiation between bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder, as the focus was on an overarching assessment of the bipolar spectrum (McIntyre et al., 2020). Nevertheless, despite differences between these diagnoses, they are all characterised by ‘unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, concentration and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

6. Conclusions

With our study, we aimed to gather evidence on the decision-making capacity of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. We found this topic valuable as informed consent competency is often assessed merely on a clinical basis (Gowensmith et al., 2013), and patients with bipolar disorder are typically considered more functional during remission phases compared to those with schizophrenia. The results of our meta-analysis, however, indicate that there are no significant differences between the two groups, at least as revealed by standardized assessment tools. We hypothesize that cognitive aspects predominantly play a role in determining capacity during stable phases.

These results lead to the consideration that it is useful to assess the capacity to provide consent at any stage of illness, both for diagnostic-therapeutic phases and for research and advance directives.

However, in the clinical milieu, assessment of capacity should be always considered in a personalized manner, avoiding a general judgment of presence or absence. Assessment scales serve as a support to delve into the dimensions of competence and provide guidance to HCPs, in the absence of a specific cut-off to determine whether a person is legally competent or not.

Additionally, HCPs should also be mindful that the assessment of capacity should not be regarded as a 'global' evaluation of patients’ overall mental status or ability to make a multitude of decisions. Rather, it should be focused on a specific decision-making task at a particular moment in time only (Moye et al., 2007; Carroll, 2010).

The results of our study provide further indication regarding the limited reliability of assessments based on clinical judgment, especially relying solely on the value of the diagnosis.

Furthermore, it is emphasized that despite similar results emerging for both patient groups, additional elements are lacking to define the reasons for this overlap. Further studies could clarify this point by examining whether the absence of differences in capacity between the two patient groups is only based on cognitive profiles or if additional variables, potentially imbricated, have a peculiar role.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Studies employing similar instruments, such as MacCAT-T and Mac-CAT-CR; Table S1: Studies enrolling patients in a clinical remission status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; methodology, D.M. and M.L.; software, D.M. and G.D.; validation and formal analysis, P.F.; investigation, D.M., M.L. and V.F.; resources, R.R.; data curation, D.M. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; visualization, N.D.F.; supervision, V.F.; project administration, V.F. and P.F.; funding acquisition, G.D. and R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, A. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Appelbaum, P. S. (2010). Consent in impaired populations. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 10(5), 367–373. [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, P. S., & Redlich, A. (2006). Impact of decisional capacity on the use of leverage to encourage treatment adherence. Community Mental Health Journal, 42(2), 121–130. [CrossRef]

- Belmaker, R. H., & Bersudsky, Y. (2009). Bipolar Disorder: Mania and Depression. Discovery Medicine, 4(23), 239–245.

- Brydges, C. R. (2019). Effect Size Guidelines, Sample Size Calculations, and Statistical Power in Gerontology. Innovation in Aging, 3(4), igz036. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. (2004). Mental capacity, legal competence and consent to treatment. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 97(9), 415–420. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R., Maddock, C., Buchanan, A., David, A. S., Hayward, P., Richardson, G., Szmukler, G., & Hotopf, M. (2005). Prevalence and predictors of mental incapacity in psychiatric in-patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 187, 379–385. [CrossRef]

- Capdevielle, D., Raffard, S., Bayard, S., Garcia, F., Baciu, O., Bouzigues, I., & Boulenger, J.-P. (2009). Competence to consent and insight in schizophrenia: Is there an association? A pilot study. Schizophrenia Research, 108(1–3), 272–279. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, W. T., Gold, J. M., Lahti, A. C., Queern, C. A., Conley, R. R., Bartko, J. J., Kovnick, J., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2000). Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(6), 533–538. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D. W. (2010). Assessment of Capacity for Medical Decision Making. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 36(5), 47–52. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Fitzgerald, H. M., Madera, J. J., & Tohen, M. (2019). Functional outcome assessment in bipolar disorder: A systematic literature review. Bipolar Disorders, 21(3), 194–214. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. J., McGarvey, E. L., Pinkerton, R. C., & Kryzhanivska, L. (2004). Willingness and competence of depressed and schizophrenic inpatients to consent to research. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 32(2), 134–143.

- Crocetti, E. (2016). Systematic Reviews With Meta-Analysis: Why, When, and How? Emerging Adulthood, 4(1), 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Curley, A., Watson, C., & Kelly, B. D. (2022). Capacity to consent to treatment in psychiatry inpatients—A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 26(3), 303–315. [CrossRef]

- Director, S. (2023). Bipolar disorder and competence. Journal of Medical Ethics, jme-2023-109479. [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 629–634. [CrossRef]

- Gowensmith, W. N., Murrie, D. C., & Boccaccini, M. T. (2013). How reliable are forensic evaluations of legal sanity? Law and Human Behavior, 37(2), 98–106. [CrossRef]

- Grisso, T., Appelbaum, P. S., & Hill-Fotouhi, C. (1997). The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 48(11), 1415–1419. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U. C., & Kharawala, S. (2012). Informed consent in psychiatry clinical research: A conceptual review of issues, challenges, and recommendations. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 3(1), 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Hindmarch, T., Hotopf, M., & Owen, G. S. (2013). Depression and decision-making capacity for treatment or research: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 14, 54. [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, H. (2023). Assessing Medical Decision-Making Competence Using the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool-Treatment for Schizophrenia. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 25(3), 22br03424. [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D. V., Depp, C. A., & Palmer, B. W. (2006). Magnitude of Impairment in Decisional Capacity in People With Schizophrenia Compared to Normal Subjects: An Overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(1), 121–128. [CrossRef]

- Klein, C. C., Jolson, M. B., Lazarus, M., Masterson, B., Blom, T. J., Adler, C. M., DelBello, M. P., & Strakowski, S. M. (2019). Capacity to provide informed consent among adults with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Koukopoulos, A., Mandarelli, G., Maglio, G., Macellaro, M., Cifrodelli, M., Kotzalidis, G., Tarsitani, L., Biondi, M., & Ferracuti, S. (2020). Evaluation of the capacity to consent to treatment among patients with bipolar disorder: Comparison between the acute psychopathological episode and the stable mood phase. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 2, 100037. [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, J. S., DeLuca, J., & Caplan, B. (A c. Di). (2011). MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology (pp. 1501–1501). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Lamont, S., Jeon, Y.-H., & Chiarella, M. (2013). Assessing patient capacity to consent to treatment: An integrative review of instruments and tools. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(17–18), 2387–2403. [CrossRef]

- Lepping, P., Stanly, T., & Turner, J. (2015). Systematic review on the prevalence of lack of capacity in medical and psychiatric settings. Clinical Medicine (London, England), 15(4), 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1-34. [CrossRef]

- López-Jaramillo, C., Tobler, C. A., Gómez, C. O., & Triana, J. E. (2016). Correlation Between Insight and Capacity to Consent to Research in Subjects With Bipolar Disorder Type I and Schizophrenia. Revista Colombiana De Psiquiatria, 45(3), 194–200. [CrossRef]

- Mandarelli, G., Carabellese, F., Parmigiani, G., Bernardini, F., Pauselli, L., Quartesan, R., Catanesi, R., & Ferracuti, S. (2018). Treatment decision-making capacity in non-consensual psychiatric treatment: A multicentre study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(5), 492–499. [CrossRef]

- Mandarelli, G., Tarsitani, L., Parmigiani, G., Polselli, G. M., Frati, P., Biondi, M., & Ferracuti, S. (2014). Mental capacity in patients involuntarily or voluntarily receiving psychiatric treatment for an acute mental disorder. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 59(4), 1002–1007. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R. S., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Goldstein, B. I., López-Jaramillo, C., Kessing, L. V., Malhi, G. S., Nierenberg, A. A., Rosenblat, J. D., Majeed, A., Vieta, E., Vinberg, M., Young, A. H., & Mansur, R. B. (2020). Bipolar disorders. Lancet (London, England), 396(10265), 1841–1856. [CrossRef]

- Misra, S., Socherman, R., Park, B. S., Hauser, P., & Ganzini, L. (2008). Influence of mood state on capacity to consent to research in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 10(2), 303–309. [CrossRef]

- Moser, D. J., Schultz, S. K., Arndt, S., Benjamin, M. L., Fleming, F. W., Brems, C. S., Paulsen, J. S., Appelbaum, P. S., & Andreasen, N. C. (2002). Capacity to provide informed consent for participation in schizophrenia and HIV research. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(7), 1201–1207. [CrossRef]

- Moskalewicz, A., & Oremus, M. (2020). No clear choice between Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies to assess methodological quality in cross-sectional studies of health-related quality of life and breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 120, 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Moye, J., Karel, M. J., Edelstein, B., Hicken, B., Armesto, J. C., & Gurrera, R. J. (2007). Assessment of Capacity to Consent to Treatment. Clinical Gerontologist, 31(3), 37–66. [CrossRef]

- Overall, J. E., & Gorham, D. R. (1962). The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports, 10, 799–812. [CrossRef]

- Owen, G. S., David, A. S., Richardson, G., Szmukler, G., Hayward, P., & Hotopf, M. (2009). Mental capacity, diagnosis and insight in psychiatric in-patients: A cross-sectional study. Psychological Medicine, 39(8), 1389–1398. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B. W., Dunn, L. B., Depp, C. A., Eyler, L. T., & Jeste, D. V. (2007). Decisional capacity to consent to research among patients with bipolar disorder: Comparison with schizophrenia patients and healthy subjects. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(5), 689–696. [CrossRef]

- Raffard, S., Lebrun, C., Laraki, Y., & Capdevielle, D. (2021). Validation of the French Version of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) in a French Sample of Individuals with Schizophrenia: Validation de la version française de l’instrument d’évaluation des compétences MacArthur-traitement (MacCAT-T) dans un échantillon français de personnes souffrant de schizophrénie. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 66(4), 395–405. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Moreno, J., Martinez-Aran, A., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., Torrent, C., Vieta, E., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2009). Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: An extensive review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(5), 285–297. [CrossRef]

- Santurro, A., Vullo, A. M., Borro, M., Gentile, G., Russa, R. L., Simmaco, M., Frati, P., & Fineschi, V. (2017). Personalized medicine applied to forensic sciences: New advances and perspectives for a tailored forensic approach. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 18(3), 263–273. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B. W. J., Gergel, T., Hotopf, M., & Owen, G. S. (2018). Unwell in hospital but not incapable: Cross-sectional study on the dissociation of decision-making capacity for treatment and research in in-patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(2), 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B. W. J., Shields, G., Gergel, T., Hotopf, M., & Owen, G. S. (2017). Diversity or disarray? A systematic review of decision-making capacity for treatment and research in schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses. Psychological Medicine, 47(11), 1906–1922. [CrossRef]

- Srebnik, D., Appelbaum, P. S., & Russo, J. (2004). Assessing competence to complete psychiatric advance directives with the competence assessment tool for psychiatric advance directives. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 45(4), 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Stroup, S., Appelbaum, P., Swartz, M., Patel, M., Davis, S., Jeste, D., Kim, S., Keefe, R., Manschreck, T., McEvoy, J., & Lieberman, J. (2005). Decision-making capacity for research participation among individuals in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophrenia Research, 80(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Tannou, T., Koeberlé, S., Aubry, R., & Haffen, E. (2020). How does decisional capacity evolve with normal cognitive aging: Systematic review of the literature. European Geriatric Medicine, 11(1), 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. P., Nisha, A., & Varghese, P. J. (2016). Disability and Quality of Life of Subjects with Bipolar Affective Disorder in Remission. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 336–340. [CrossRef]

- Turillazzi, E., Neri, M., Riezzo, I., Frati, P., & Fineschi, V. (2014). Informed consent in Italy-traditional versus the law: A gordian knot. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 38(4), 759–764. [CrossRef]

- Vaskinn, A., Haatveit, B., Melle, I., Andreassen, O. A., Ueland, T., & Sundet, K. (2020). Cognitive Heterogeneity across Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder: A Cluster Analysis of Intellectual Trajectories. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS, 26(9), 860–872. [CrossRef]

- Vöhringer, P. A., Barroilhet, S. A., Amerio, A., Reale, M. L., Alvear, K., Vergne, D., & Ghaemi, S. N. (2013). Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 87. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-B., Wang, Y.-Y., Ungvari, G. S., Ng, C. H., Wu, R.-R., Wang, J., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2017). The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tools for assessing decision-making capacity in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 183, 56–63. [CrossRef]

- Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, je, Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2000). The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis.

- WONG, J. (2002). MacCAT-CR: MacArthur Competence Tool for Clinical Research. By P. S. Appelbaum and T. Grisso. (Pp. 84; $22.00.) Professional Resource Press: Sarasota, FL. 2001. -. Psychological Medicine, 32, 943–948. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).