Introduction

A recent Consensus Panel on Tremor defined

tremor as an oscillatory and rhythmical movement [

1]. A different Consensus Panel on Dystonia defined

dystonia as a disorder of sustained or intermittent muscle contractions leading to abnormal postures, repetitive movements, or both [

2]. With these defining characteristics, most common types of tremor or dystonia are usually easy to distinguish.

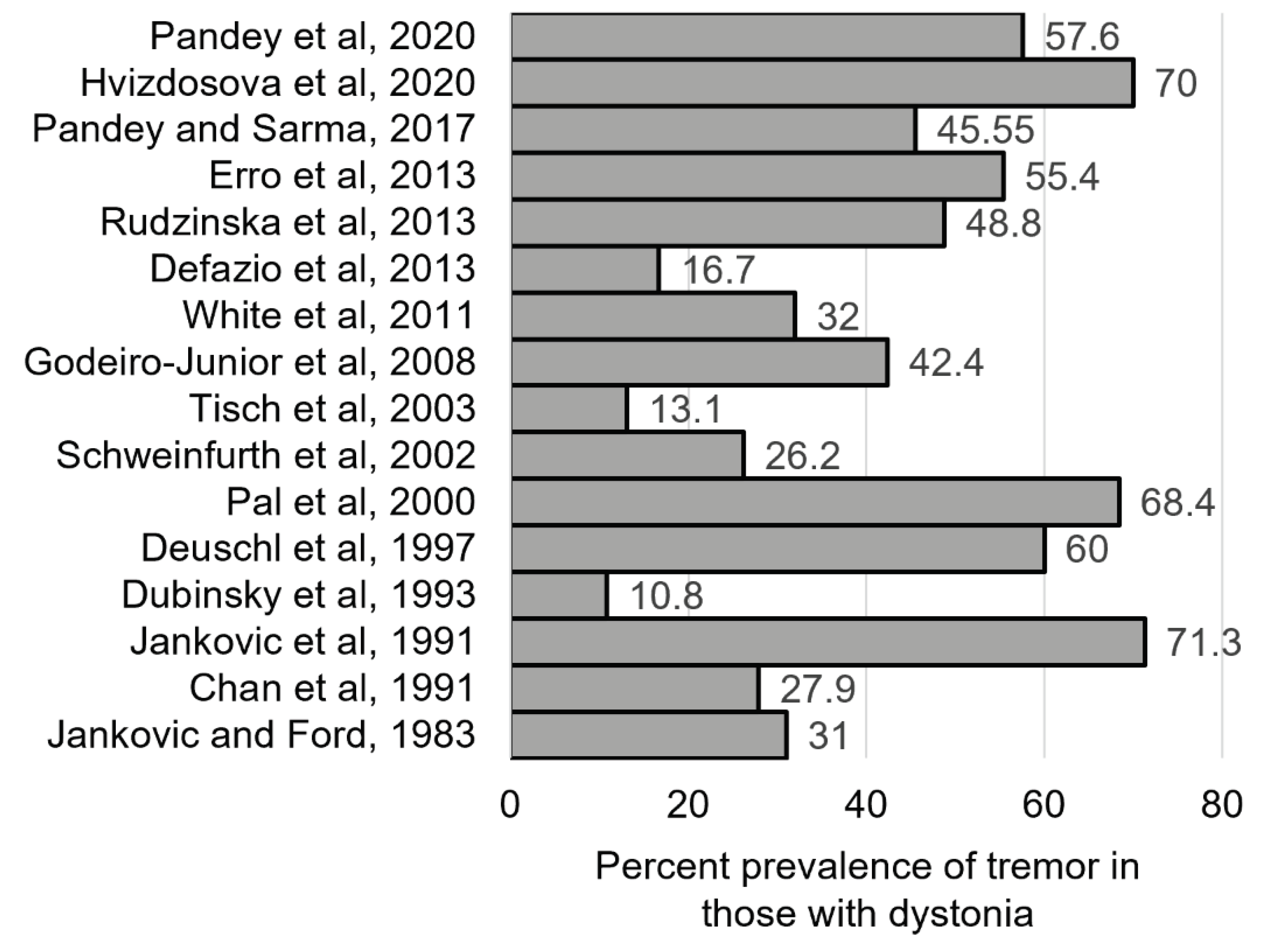

Dystonia and tremor often co-exist (

Figure 1). In a recent large study of 2362 individuals with different types of dystonia, 53% had tremor [

3] One view of the frequent co-occurrence of tremor and dystonia is that these movements reflect frequently combined yet independent movements. Another view is that different combinations of tremor with dystonia delineate unique clinical syndromes. A third view is that tremor and dystonia reflect a continuum [

4]. In some cases with dystonia, there may also be rapid and repetitive movements mimicking tremor, although the term

tremor may not be appropriate [

4]. The term

dystonic tremor is widely used to describe varied combinations of dystonia and tremor, and other tremor-like movements.

The Tremor Consensus Panel and the Dystonia Consensus Panel both recognized the frequent co-existence of dystonia and tremor, but their approaches to describing their relationships differed. To develop a more unified approach, a new Dystonia-Tremor Panel (D-T panel) was created with members from both the original Dystonia or Tremor Consensus panels, as well as new members who were not part of prior panels. The D-T panel did not aim to re-define dystonia or tremor. Instead, the goal was to develop a more consistent approach for describing tremor and other tremor-like movements in dystonia.

Methods

The D-T panel members met monthly via the internet and twice in person. In the first virtual meeting, the nature of the problem was laid out, with a description of the goal. Each panel member was invited to provide opinions on the relationship between dystonia and tremor, especially dystonic tremor. Following this meeting, areas of agreement and disagreement were identified, and several questions were generated to focus discussion on differences of opinion. During each meeting, one panel member was asked to provide a summary of the question, including a relevant literature review, and all members were invited to comment. Following each meeting, a written summary was distributed to the entire panel for additional comments. Additional comments were collected and shared through email. A summary manuscript describing the discussions was prepared, and members commented on multiple iterations. This is a review paper and

Historical Perspective

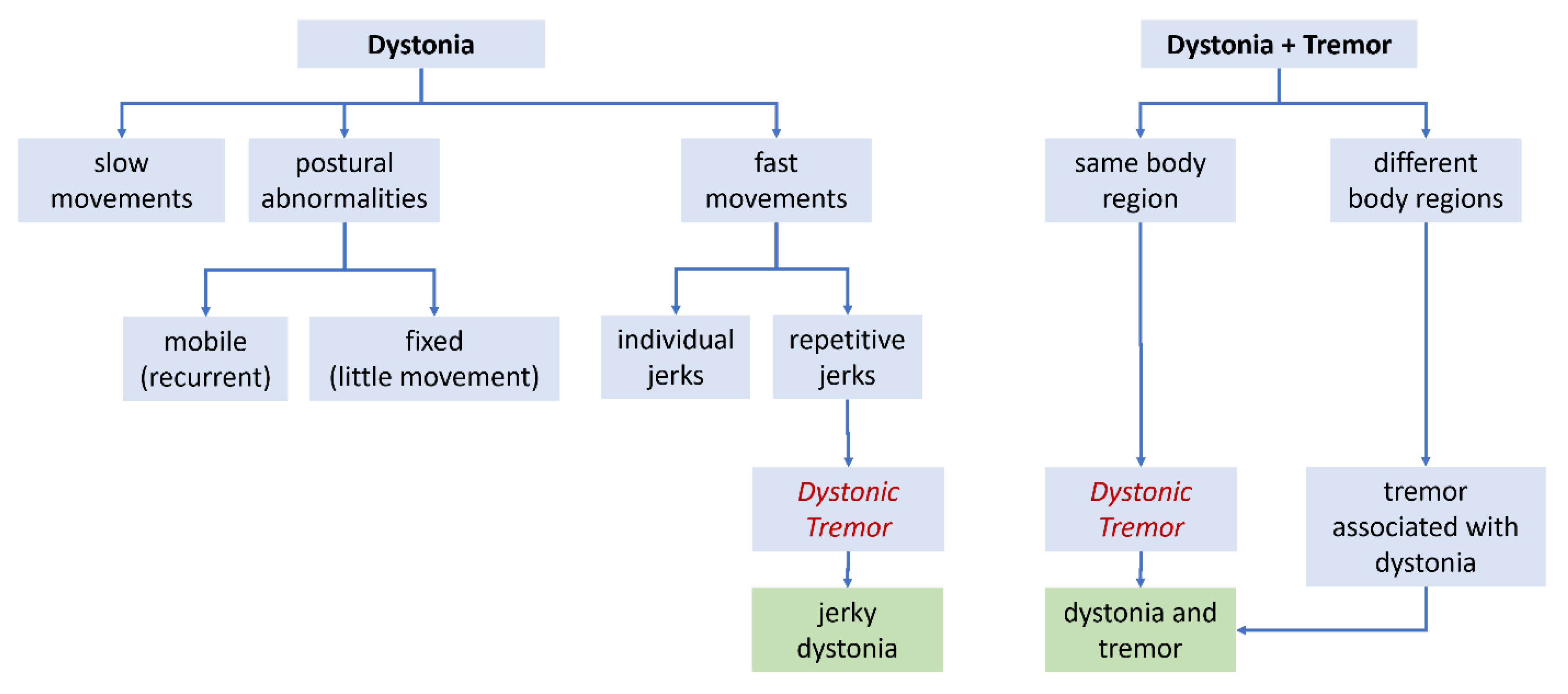

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the varied manifestations of dystonia were first being delineated, the main focus was on slow twisting movements and abnormal postures (

Figure 2A). However, rapid movements were recognized too, and they were sometimes repetitive [

5,

6,

7]. Two distinct types of rapid/repetitive movements were acknowledged. One was relatively rhythmical and sinusoidal, closely resembling the tremor of essential tremor (ET). In fact, individuals with dystonia often had family members who were diagnosed with ET, and some experts began to refer to this type of tremor as ET, even among individuals who also had dystonia [

3,

8], despite existing definitions of ET as a pure tremor disorder.

A second type of rapid/repetitive movement in dystonia, distinct from the tremor noted above, was also recognized [

5,

6,

7]. This type of movement was jerky, and often irregular (

Figure 2A). The term

dystonic tremor was introduced to distinguish this second type of repetitive movement from the first one [

6,

7]. In the ensuing literature,

dystonic tremor was often described as irregular and jerky (

Table 1). An additional feature said to aid in the identification of dystonic tremors was position-dependence, including a

null point where the movement attenuated or disappeared. Another feature was suppression of the movement by a

geste antagoniste (sensory trick or alleviating maneuver), a feature not observed in other tremors. This

dystonic tremor sometimes occurred in the absence of overt dystonic postures in the same body region, so the co-existence of dystonia was not required.

In 1998, the first consensus panel on tremor proposed new terms for tremor among individuals with dystonia [

9]. The panel proposed that

dystonic tremor be defined as a tremor that was accompanied by overt dystonic movements in the affected body region (

Figure 2B). The panel acknowledged that dystonic tremors were often irregular and jerky, but these features were not required. The panel also proposed a new term,

tremor associated with dystonia (TAWD) for cases where tremor occurred in a body region without dystonia, while dystonia occurred in a different body region (

Figure 2B). These views of

dystonic tremor were re-iterated by a second Tremor Consensus panel in 2018 [

1].

The Dystonia Consensus panel acknowledged that "tremulousness" could be a feature of dystonia [

2]. The text acknowledged early descriptions that "some dystonic contractions may be intermittent and seemingly rhythmical, as in the so-called

dystonic tremor". Additionally, a summary table described

dystonic tremor as "a spontaneous oscillatory, rhythmical, although often inconstant, patterned movement produced by contractions of dystonic muscles often exacerbated by an attempt to maintain primary posture" [

2] The Dystonia Consensus panel did not stipulate co-existing dystonic postures as required feature of

dystonic tremor.

The different descriptions of

dystonic tremor are not entirely consistent with each other. The early descriptions emphasized a jerky and irregular movement regardless of co-existing dystonic movements, while the Tremor Consensus panel definition emphasized the co-existence of tremor and dystonia, regardless of jerkiness or regularity (

Table 1). An empirical study demonstrated that these two definitions do not delineate the same group of individuals [

3]. Some literature on dystonic tremor continues to emphasize features of early descriptions, focusing on repetitive movements that are jerky and irregular, regardless of co-existing dystonia [

10,

11,

12] Other literature emphasizes the co-existence of repetitive movements with overt dystonia, regardless of jerkiness or regularity [

13]. Some literature employs a hybrid approach, emphasizing jerkiness and irregular qualities along with co-existing dystonic posturing [

14,

15]. Still other literature has adopted alternative terminology, such as

jerky dystonia [

16,

17,

18],

dystonia-tremor syndrome [

19,

20,

21],

dystonia with tremor [

22,

23,

24], and

tremulous dystonia [

25,

26]. Varying viewpoints are evident even among movement disorder specialists [

27,

28]. The D-T panel aimed re-evaluate concepts and nomenclature regarding dystonia and tremor, particularly

dystonic tremor [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

The current manuscript addresses: 1) the relevance of the nomenclature problem relating to dystonic tremor, 2) strengths & weaknesses of proposed defining features of dystonic tremor, 3) the concept of tremor associated with dystonia and 4) clinical applications vs laboratory-aided measures. It concludes with several recommendations.

1. Relevance of the Problem

Among D-T panel members, there was nearly universal acknowledgement that varied use of terminology regarding dystonia and tremor is an ongoing problem, both in the clinic and in the research literature. Two D-T panel members favored using the guidelines from the Tremor Consensus panel, four favored the earlier approach that focused on irregular and jerky qualities, and five favored a hybrid approach combining the two different approaches.

Similar differences in viewpoints are evident in the literature. In one study exploring inter-rater agreement in the assessment of ET, the poorest agreements were found in tremor items relating to dystonia [

27]. In another study, seven movement disorder specialists evaluated videos of five cases where dystonia and tremor were combined [

28]. One expert diagnosed all cases as having ET with dystonia, viewing these movement phenomenologies as independent but frequently co-existing. Another expert diagnosed all cases with dystonic tremor, viewing the combination of dystonia with tremor to be a distinct syndromic entity. A third expert diagnosed all cases with ET alone and considered the apparent dystonic postures to be compensatory movements or variants of normal behavior. The remaining experts gave various combinations of diagnoses to different cases, with little consistency. A similar study also involving seven movement disorder specialists evaluated videos of tremor cases with additional movement disorders that might be considered mild manifestations of dystonia [

42]. There was very low inter-rater agreement with respect to the presence of dystonic features, with almost no consensus when videos were evaluated by non-movement disorder specialists. These observations highlight a problem of terminology in need of a more unified approach.

There was also universal agreement among all D-T panel members that the problem of precise identification of tremor and other tremor-like movements in dystonia is not merely an academic exercise. From the clinical perspective, there are numerous reports of individuals said to be misdiagnosed with dystonia, tremor, or both [

8,

13,

31,

33,

34,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Misdiagnosis means patients may be treated inappropriately [

15,

52]. Misdiagnosis also impacts outcomes in clinical trials involving medications for tremor or dystonia. The issue is even more important for surgical interventions such as deep brain stimulation or focused ultrasound [

15,

22,

53,

54]. The pallidum is the favored target for dystonia while the thalamus is the favored target for tremor, and it has been argued that procedures targeting the thalamus for tremor might worsen dystonia [

55]. When the main goal of treatment is

dystonic tremor, it is not clear which target is best, because of dual use of the term for jerky dystonia or tremor in a dystonic body region.

Misdiagnosis also has a big impact for scientific studies. In genetic mapping studies, misdiagnosis of a single family member can dramatically alter the outcome. This issue is particularly relevant considering that many family studies have noted that some family members have dystonia, some have tremor, and some have both [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Dual use of the term dystonic tremor makes it difficult to classify individual family members. Misdiagnosis or vaguely defined cohorts will also have an impact on studies addressing physiology, imaging, or biomarkers. In view of these considerations, the D-T panel recommended that a more unified approach is needed for both clinical application and interpretation of scientific studies.

2. Dystonic Tremor

Several different qualities have been proposed to define

dystonic tremor [

31]. The main features have included jerkiness, irregularity, and co-existing dystonic postures. Each feature has strengths and weaknesses.

Jerkiness. Jerkiness can be a helpful clinical feature for discriminating tremors from other movement disorders. The tremors of ET and Parkinson's disease are not usually jerky, although occasional jerks may be seen [

27]. In contrast, movements that are overtly jerky usually provide a clue for non-tremor movement disorders such as myoclonus or tics [

60].

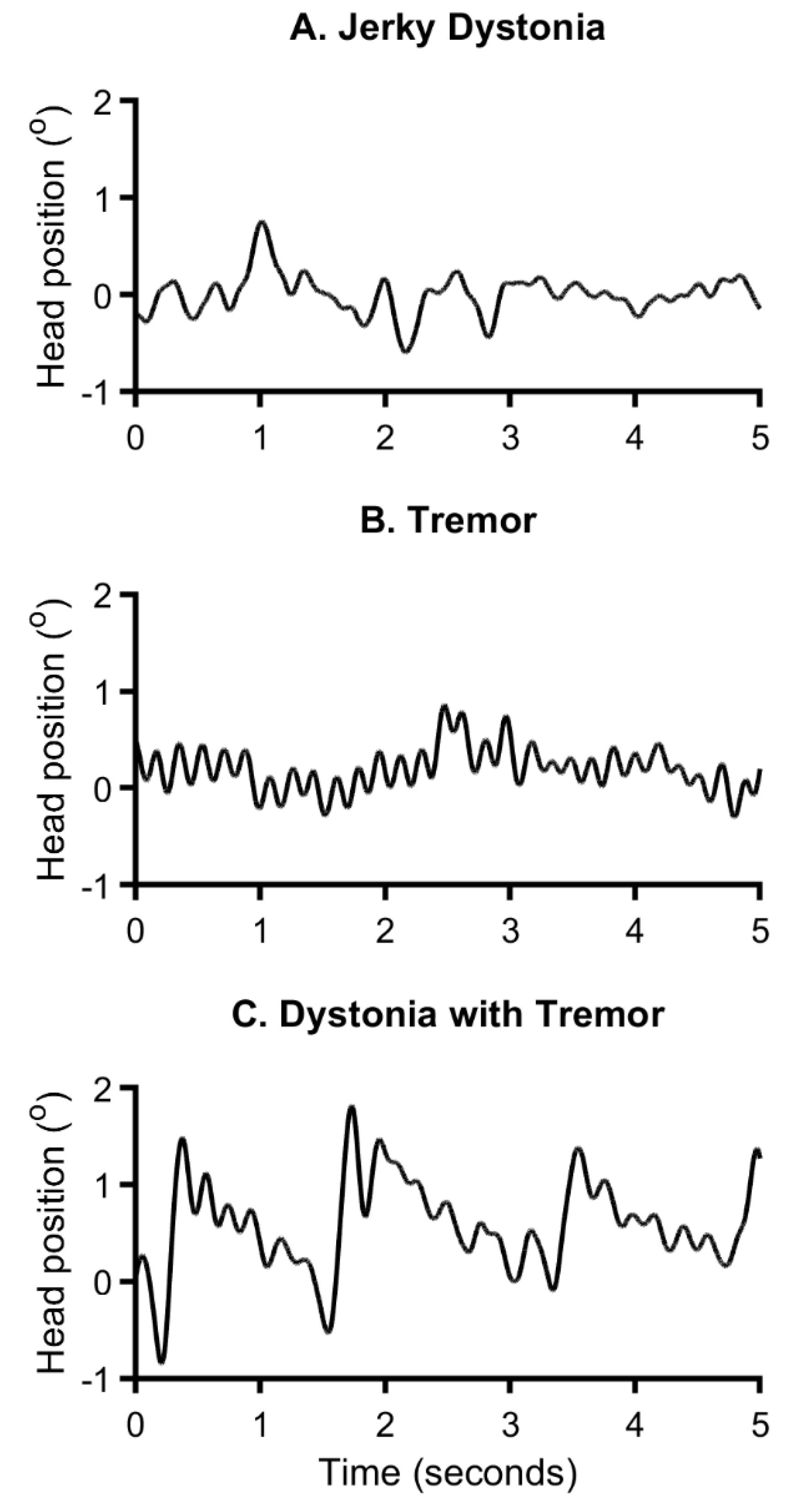

Jerkiness has two limitations. The first is that early descriptions of dystonic tremors never explicitly defined the term

jerky, leading to varied interpretations. Early descriptions referred to grouping or bursting of EMG action potentials underlying the jerks of dystonic tremor, implying a sudden movement in one direction followed by a slower resetting, analogous to jerks of myoclonus or tics [

5,

6]. Repeated jerks may resemble a tremor, but produce a sawtooth waveform (

Figure 3A) [

61,

62,

63]. In contrast, essential or Parkinsonian tremors usually produce a more sinusoidal waveform (

Figure 3B). Unfortunately, in the absence of an explicit definition, clinical impression of jerkiness may be derived from other phenomena such as superimposed dystonic spasms, or sudden changes in amplitude, frequency, direction, or any combination of these possibilities. In fact, a recent study showed that clinical impressions of "jerkiness" in dystonia subjects was associated with broadening of the peak in the power spectrum, a phenomenon associated with multiple oscillators of varying frequencies [

64] or a heterogenous movement combining dystonic muscle spasms with oscillations fulfilling the definition of tremor. These studies and others emphasize the importance of recognizing that multiple types of repetitive movements may co-exist in the same patient (

Figure 3C) [

61,

62,

63,

65,

66]. Thus, clinical impressions of jerkiness may be influenced by many variables.

The second limitation of the term "jerky" is that it is subjective and hard to reliably assess in the clinic. Repetitive movements that are overtly jerky may be easy to identify, but more subtle jerkiness is difficult to ascertain at bedside. There are no studies exploring the reliability of clinical impressions of jerkiness. Similarly, there are no studies exploring if jerkiness differentiates distinct types of tremor-like movements into meaningful subgroups.

The problem with imprecise definitions of jerkiness is evident in the literature, where very few articles define the term. In a recent study, the term "jerk" was used in two different ways [

27]. The first use was defining "mini jerks" or "isolated jerks" without tremor, presumably referring to a sudden isolated movement similar to a myoclonic jerk. The same study simultaneously defined "jerkiness" as "arrhythmic or irregular amplitude variations". The latter application implies that jerkiness results from changes in rhythm or amplitude [

27]. Such dual usage of the same term for different purposes is confusing.

Overall, the majority of the D-T panel agreed that jerkiness was usually but not always a useful feature for distinguishing dystonic tremors from other tremors. The panel questioned whether these variables can be detected by the clinical exam, and which feature may most correspond to clinical impressions of jerkiness. As a result, the panel recommended that this term be replaced by more specific terminology related to actual movements such as waveform shape or variations in amplitude or rhythmicity.

Regularity. A regular tempo is a defining feature of most tremors. In fact, the tremor consensus panels definition of tremor included the terms

rhythmical and

oscillation, both of which imply temporal regularity [

1,

9]. Although no tremor is perfectly rhythmical, ET and Parkinsonian tremors are sufficiently rhythmic to produce a statistically significant power spectral peak at one frequency [

27]. A repetitive movement that is overtly non-rhythmical therefore can provide a useful clue for a different movement disorder [

60].

The term

regularity has several limitations too. First, the definition of

regularity is not directly synonymous with

rhythmicity, and therefore may carry different meanings. Early descriptions regarding irregularity of dystonic tremors appeared to refer to changes in tempo, but the term was not specifically defined. In fact, the term

regular more specifically means

following standard rules. As a result, clinical impressions of regularity may include occasional movements that are not like the majority of other repetitions of the same movement. Occasional movements may have unexpected changes in amplitude, frequency, direction, or any combination of these possibilities. In fact, in a study assessing various features of tremor, the "regularity" of hand tremor received increasing scores according to arrhythmicity, jerkiness, and variations in amplitude [

27].

Second, even if

regularity is limited to rhythmicity, assessing rhythmicity can be subjective. Biological tremors are rarely perfectly rhythmical, and some variations always occur. There may be continuum between more or less rhythmic movements, and whether there is a clear border between them has not been established. Impressions of rhythmicity are also frequency-dependent, such that faster movements tend to be judged as rhythmical more often than slower ones. Additional complexity is represented by individuals with rhythmical tremor and superimposed dystonic movements, which may give the false impression of a non-rhythmic movement (

Figure 3). There are few studies exploring the reliability of clinical impressions of rhythmicity.

Overall, 9 of 12 D-T panel members agreed that a lack of regularity was usually but not always a useful feature for distinguishing dystonic tremors from other tremors. However, to avoid varied interpretations, the term regularity should be replaced by more specific terms, such as rhythmicity. Further studies addressing clinical impressions of rhythmicity combined with instrumented measures of various features that may contribute to clinical impressions of regularity are needed.

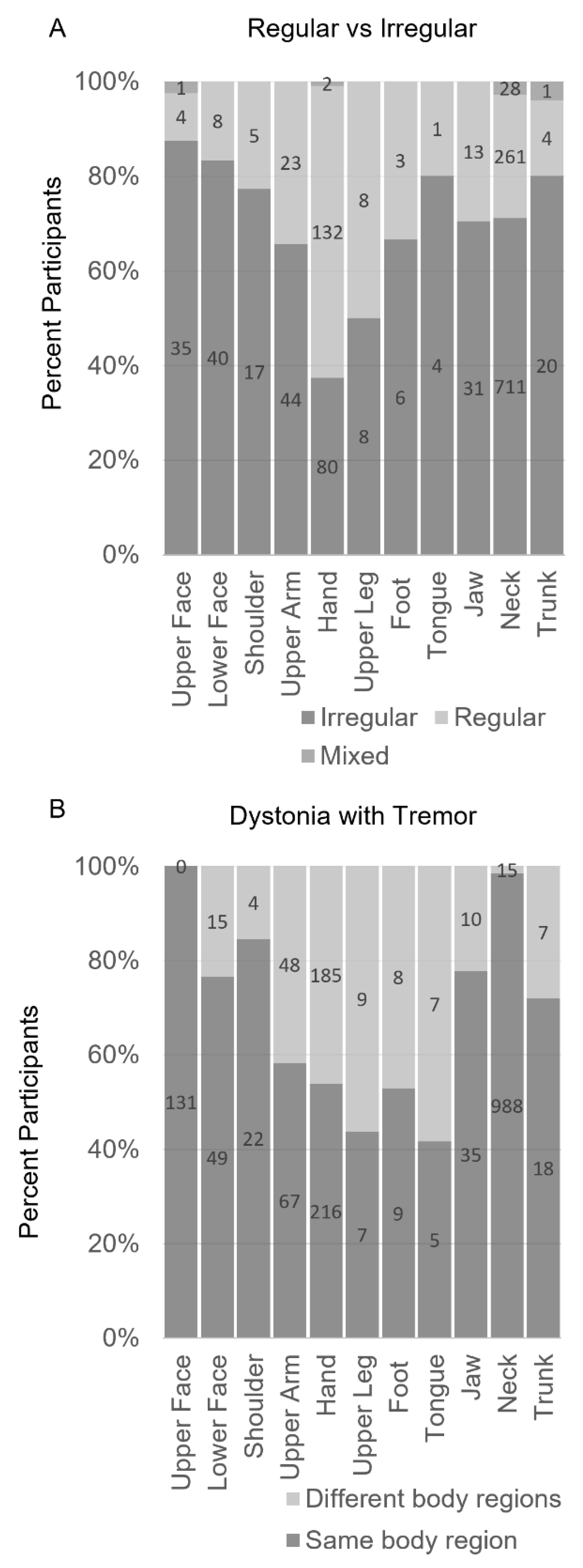

Co-existence of overt dystonic postures or movements. The Tremor Consensus panels defined dystonic tremor as tremor in a body region affected by dystonia. Earlier definitions did not require co-existence of additional overt dystonic movements (

Table 1). While this distinction may seem minor, a recent study showed that these different criteria delineate different subgroups of individuals (

Figure 4) [

3]. A major advantage of requiring simultaneous dystonia in the definition of dystonic tremor is that it may facilitate clinical recognition of a common phenomenology. A related advantage is that it eliminates the subjectivity associated with jerky or irregular qualities.

This approach also has some limitations. First, the identification of concomitant dystonia can be subjective [

67,

68]. Overt twisting movements or abnormal postures may be easy to recognize, but slightly abnormal postures are easy to overlook. More importantly, it may be unclear if slightly abnormal postures reflect dystonia, a normal variant, or even behavioral compensation for severe tremor [

27,

28]. This problem led to introduction of the concept of ET-plus, where ET is combined with soft neurological signs of unclear significance [

1]. This concept of ET-plus has already been extensively criticized [

67,

69,

70]

A second limitation of the requirement for overt dystonic postures is that these are not always present. Examples include isolated head or voice tremors [

25,

71,

72,

73], and task-specific tremors such as primary writing tremor [

65,

74,

75]. Similarly, for TAWD (such as hand tremors in individuals with cervical dystonia), it is not clear if the hand tremors should be considered a manifestation of dystonia or a coincidental movement phenomenology [

76,

77,

78,

79]. A related condition is

tremor-dominant dystonia, a term previously used to describe repetitive movements that are far more prominent than abnormal postures or twisting movements [

6,

34,

71,

80,

81,

82].

The final limitation in requiring overt dystonic movements in the definition of dystonic tremor is the implication that any type of tremor in a dystonic body part is a dystonic tremor. This assumption obscures the possibility that dystonia may be coincidentally combined with another tremor, such as action tremors, the tremor of Parkinson disease, or cerebellar disease. In view of these many limitations, most D-T panel members recommended against defining dystonic tremor solely by the co-existence of overt dystonia in the same body part.

Dystonic tremor terminology. D-T panel members also acknowledged some limitations of the term

dystonic tremor itself. All D-T panel members agreed that tremors are usually rhythmical and sinusoidal. All also agreed that a repetitive movement that is grossly non-rhythmical or has disparity in speeds of to and fro movements should not be called a tremor. If arrhythmicity is a defining feature of dystonic tremor, then the early definition of

dystonic tremor was a misnomer, because a defining feature was temporal irregularity. However, panel members acknowledged that some disorders classified as tremors are not rhythmical, such as some cases of palatal tremor [

1] so the requirement for rhythmicity is not uniformly applied for tremor disorders.

Another problem was that some D-T panel members viewed the hybrid term dystonic tremor on purely phenomenological grounds, as a movement syndrome in which dystonia and tremor are combined. Others viewed the hybrid term as implying a tremor caused by dystonia, thereby confounding the separation of phenomenology and etiology with Axes I and II.

The D-T panel recommended a more consistent approach to usage of the term dystonic tremor, and possibility of replacing the term with an alternative term was considered. Despite problems introduced by varied potential interpretations of the term dystonic tremor, the panel recognized widespread use of the term and felt it would be challenging to eliminate it.

3. The Concept of Tremor Associated with Dystonia

TAWD was defined by the Tremor Consensus panels as an oscillatory movement (ET-like) occurring in a body part that is not affected by dystonia, but dystonia is present elsewhere [

1,

9]. In principle, this concept is relatively straightforward and easy to apply in the clinic. However, TAWD was not acknowledged in the Dystonia Consensus panel report [

2], and it has not been universally adopted by movement disorders specialists.

Seven of twelve D-T panel members believed that the concept of TAWD is not useful [

2]. Five members believed that TAWD is a useful construct, but several used definitions that were modified from the Tremor Consensus panel. For example, one member diagnosed TAWD only if the tremor developed after dystonia. Some suggested that TAWD is a "forme fruste" of dystonia rather than a tremor. Others interpreted the term TAWD to mean that tremor and dystonia reflect a distinct syndrome, while others believed that it means tremor and dystonia are independent but frequently co-existing problems.

Several limitations of TAWD may explain why it has not gained broad acceptance. The first is that the concept of TAWD implies that tremor occurring in a patient with dystonia is somehow distinct from other isolated tremors, either phenomenologically or etiologically. There is limited evidence that TAWD should be handled differently from isolated tremors. There is some evidence that TAWD is kinematically distinct from isolated tremors [

66,

77,

78], but most of these studies did not address the possibility of a mixed movement disorder, such as tremor with intermittent dystonic jerking. In fact, very subtle or mild dystonia of uncertain significance is hard to reliably detect, making the discrimination of TAWD from dystonic tremor challenging.

Many members of the D-T panel questioned the value of the concept of TAWD, because it is not clear that TAWD deserves recognition as a diagnostic entity distinct from two co-existing movements. However, most also felt the concept might be more useful if this value could be better delineated. This is particularly important to avoid common mistakes caused by the common combination of cervical dystonia and tremor of the arms.

4. Clinical Applications vs Laboratory-Aided Measures

The D-T panel unanimously agreed that there is a need for an approach that can be used in the clinic by practicing clinicians. The panel also agreed that the clinical evaluation alone may be too crude for discriminating important characteristics of tremors and other movements that may mimic tremor. Therefore, laboratory-aided measures may be needed. Multiple methods are available for this purpose, each with advantages and disadvantages [

61,

62,

63,

66,

83]. These techniques include surface electromyography (EMG) [

5,

66,

72,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90], digital analysis of video [

83,

91], and kinematic methods that use accelerometers, gyroscopes, and/or magnetometry.

Surface EMG. Surface EMG is one of the earliest methods used to quantify tremor and dystonia. It is relatively inexpensive and easy to apply and widely available. EMG can measure activation of agonist-antagonist pairs, and the intervals between EMG bursts can be used to assess frequency and rhythmicity. EMG can also be used to determine if there is one or multiple superimposed rapid/repetitive movements.

An early study of 8 individuals with generalized dystonia revealed characteristic features of dystonia, including two distinct rapid/repetitive movements resembling tremor [

5]. These movements were either rhythmic or arhythmic, and sometimes both occurred in the same individual. Two distinct types of rapid/repetitive movements have since been documented by EMG for numerous other types of dystonia including focal dystonia affecting the hand, neck, or larynx [

66,

72,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Individuals with dystonia and tremor have a wider peak power spectrum peak compared to ET [

66]. In addition, clinical impression of jerkiness are associated with a broader peak of the power spectrum [

64]. These findings all suggest that rapid/repetitive movements in dystonia reflect more than one underlying repetitive movement.

The main limitation of surface EMG is that data analysis requires a certain degree of expertise that may not be widely available. Further, EMG measures muscle contractions, not movement itself. This issue may be important, because EMG can detect oscillations in dystonic subjects even when overt movements are absent.

Accelerometers and gyroscopes. Wearable sensors can measure the acceleration and velocity of movement in multiple planes. These sensors measure frequency and regularity, and they can estimate amplitudes. Like EMG, multiple oscillators can be identified by widening of the power spectrum peak. An important benefit is that they are cost-effective and portable and analyses can be automated, making them easy to deploy in the clinic. They have been widely used for tremor, although few studies focused on dystonia.

The main limitation is that they may not provide clear distinctions when multiple abnormal movements are combined. Spectral widening may result from any variability in the movement frequency, either due to multiple oscillators, superimposed dystonic jerks, or voluntary compensations. The

tremor stability index discriminates frequency changes over time and can reliably separate rhythmic oscillations with arrhythmic involuntary movements [

66,

92]. A greater tremor stability index means increased variation of tremor frequency. Subjects with dystonia have a higher tremor stability index as compared to ET, but this difference cannot discriminate multiple oscillators that might result from a typical tremor combined with dystonic jerking. Accordingly, its clinical value has been criticized [

93].

Magnetic search coils. This technique allows measurement of the position of a body part in all three planes of movement. It is very precise, with a spatial resolution of 0.1° and temporal resolution of 1000 Hz or more. It can assess frequency, amplitude, waveform shape, and their variances. It can also be used to discriminate multiple oscillators at the same time [

61,

62,

63,

94]. The technique can also disentangle a mixture of signals with different shapes and frequencies (degree of

distortion). Machine learning algorithms can be applied to separate distinct movement trajectories including tremor and dystonic jerking. The algorithms can deploy various parameters such as ratio of to and fro movements, shape and pattern of trajectory, predictability of the waveform, or the waveform complexity.

While providing a valuable tool, this method remains impractical for day-to-day clinical utilization. Only select laboratories in the world have the necessary equipment, and they require extensive technical expertise.

Video based analyses. Frame-by-frame analysis of digital video can also be used to measure tremor and dystonic jerking. This technique measures the position of a target to assess movement in two planes. This method can assess frequency, amplitude, direction, and variability of movements. One major advantage of this method is that digital video cameras are widely available in the clinic, and algorithms for assessing the video can be done off-line or even remotely. One limitation is that it only estimates movement in two planes. Another is that many inexpensive digitial video cameras used in the clinic only capture 25-30 frames/second, which may limit detection of fast movements, although cameras with higher frame rates (up to 1000) are available. It only recently been deployed in studies of dystonia [

83,

91,

95].

Overall, there was unanimous agreement among D-T panel members that further development of laboratory-based tools is needed to discriminate key features of tremor, superimposed dystonic jerking, and other tremor-like movements such as repetitive dystonic jerking. All available methods can identify certain relevant features such as frequency and amplitude. However, when applied to tremor and dystonia, the ideal methods should also be capable of measuring variability including both rhythmicity and changes in amplitude. Because there is strong evidence that different tremors or tremor-like movements may be combined, the method should also be capable of detecting more than one type of movement at the same time.

Conclusions & Recommendations

The D-T panel generated several specific conclusions and recommendations.

The terminology used to describe the relationships between tremor, dystonia, and other rapid/repetitive movements in dystonia that may mimic tremor has evolved over the years. This evolution has led to this terminology being inconsistently used. In particular, the term

dystonic tremor is currently used to describe two very different kinds of movement (

Figure 2). As a result, its meaning is not always clear. There is therefore a need for a more universally used terminology relating to dystonia and tremor.

Early descriptions of dystonic tremor focused on certain phenomenological features that may be too subjective to serve as reliably defining features. More precise terminology is needed for more consistent and widespread usage. Terms such as jerky and irregular with multiple potential meanings ultimately should be replaced by terms that more precisely describe distinct and measurable features such as rhythmicity, amplitude, and potentially other characteristics such as waveform morphology.

The term tremor should be reserved for movements that are relatively rhythmical. While no tremor is perfectly rhythmical, the boundaries for defining rhythmicity have never been defined, either clinically or in terms of spectral peaks in kinematic measures. Further efforts to define these boundaries may provide a useful tool to separate tremors from other rapid and repetitive movements that may mimic tremor.

Although dystonic movements are often described by slow twisting movements or postures, rapid and repetitive movements also occur. Sometimes these rapid and repetitive movements are the major feature of dystonia, and they may be sufficiently regular to produce the appearance of a movement that resembles a tremor. While these types of movements are sometimes called

dystonic tremor, rapid/repetitive movements that are grossly arhythmical should not be called

tremor or

dystonic tremor. Terms such as

jerky dystonia may be preferred (

Figure 2). By example is the precedent of the term

fixed dystonia, which is another unusual subtype of dystonia with specific clinical implications.

It is not uncommon for a single individual to have both tremor and overt dystonic posturing. When tremor occurs in a body region distant from dystonia, the term tremor associated with dystonia has been recommended. When tremor occurs in a body region that also has overt dystonic posturing, the term dystonic tremor has been recommended. Whether or not two terms are needed to describe the overlap between dystonia and tremor in different body regions remains unproven. If overt dystonic movements are combined with tremor, alternative terms such as dystonia and tremor or dystonia-tremor syndrome can be considered, whether both movements occur in the same or different body regions. The specific body regions affected can be specified, such as head dystonia with tremor or head dystonia with hand tremor.

The term dystonic tremor is in widespread use, making it difficult to eliminate. However, users of this term should acknowledge its limitation, and any future use of the term should require an explicit definition.

Whatever terminology is chosen, it must be easy for clinicians to apply bedside, and it should not require laboratory-based measures. Although there is a clear need for consistent terminology for the clinic, importnt characteristics of tremor (rhythmicity, amplitude, waveform shape, multiple oscillators) may not be feasible to ascertain by bedside clinical exam alone. It is likely that the discrimination of various types of tremors and related dystonic movements will require more precise laboratory-based measures. Development and evaluation of these tools in cohorts of individuals with different types of tremor and dystonia disorders is needed.

Authors' Roles

AS and HJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and made subsequent edits. All authors contributed to conceptualizing the content and edited the manuscript.

Funding

AGS was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) CSR&D Merit Review (I01CX002086) VA RR&D Merit Review (I01RX003676), VA RR&D SPiRE (I21RX003878), Care Source Ohio Community Partnership Grant, and philanthropic funds to the Department of Neurology at University Hospitals (Penni and Stephen Weinberg Chair in Brain Health). AF is partly funded by the University of Toronto and the University Health Network Chair in Neuromodulation. RE is funded by Kiwanis Neuroscience Research Foundation, Illinois-Eastern Iowa District. BJ received funding from Peptron Korea, Gemvax and Kael, and Abbvie Korea. RH was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO VIDI grant # 09150172010044). MH is supported by the NINDS Intramural Program. MDT received grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development ZonMW Topsubsidie (91218013) and ZonMW Program Translational Research(40-44600-98-323). She also received an European Fund for Regional Development from the European Union (01492947) and an European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) Networking Support Scheme. Furthermore, from the province of Friesland, the Stichting Wetenschapsfonds Dystonie and unrestricted grants from Ipsen and Merz.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gamze Kilic Berkmen and the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation for their administrative support. AGS was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) CSR&D Merit Review (I01CX002086) VA RR&D Merit Review (I01RX003676), VA RR&D SPiRE (I21RX003878), Care Source Ohio Community Partnership Grant, and philanthropic funds to the Department of Neurology at University Hospitals (Penni and Stephen Weinberg Chair in Brain Health). AF is partly funded by the University of Toronto and the University Health Network Chair in Neuromodulation. RE is funded by Kiwanis Neuroscience Research Foundation, Illinois-Eastern Iowa District. BJ received funding from Peptron Korea, Gemvax and Kael, and Abbvie Korea. RH was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO VIDI grant # 09150172010044). MH is supported by the NINDS Intramural Program. MDT received grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development ZonMW Topsubsidie (91218013) and ZonMW Program Translational Research(40-44600-98-323). She also received an European Fund for Regional Development from the European Union (01492947) and an European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) Networking Support Scheme. Furthermore, from the province of Friesland, the Stichting Wetenschapsfonds Dystonie and unrestricted grants from Ipsen and Merz.

Conflicts of Interest

AGS serves on the speaker bureau for Accorda Therapeutics and Abbott Neuromodulation and is chief-editor of Dystonia. AA received speaker’s honoraria from IPsen Pharma, Merz Pharma, Boston Scientific, is President of the International Association for Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, and is Specialty Chief editor of Frontiers in Neurology. AF has stock ownership in Inbrain Pharma and has received payments as consultant and/or speaker from Abbvie, Abbott, Boston Scientific, Ceregate, Dompé Farmaceutici, Inbrain Neuroelectronics, Ipsen, Medtronic, Iota, Syneos Health, Merz, Sunovion, Paladin Labs, UCB, Sunovion. He has received research support from Abbvie, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Praxis, ES and receives royalties from Springer. RE is a paid consultant for Applied Therapeutics, Attune, Encora, Fasikl, Jazz, Neurocrine, Praxis Precision Medicines, and Sage Therapeutics. VF receives a salary from NSW Health, has received unrestricted research grants from the Michael J Fox Foundation, Abbvie and Merz, and receives royalties from Health Press Ltd and Taylor and Francis Group LLC. MH is an inventor of a patent held by NIH for the H-coil for magnetic stimulation for which he receives license fee payments from the NIH (from Brainsway). He is on the Medical Advisory Boards of Brainsway, QuantalX, and VoxNeuro and has consulted for Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Bhatia, K.P.; Bain, P.; Bajaj, N. Consensus statement on the classification of tremors. from the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov Disord 2018, 33, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.; Bressman, S.B.; et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: A consensus update. Mov Disord 2013, 28, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, A.G.; Beylergil, S.B.; Scorr, L.; et al. Dystonia & tremor: A cross-sectional study of the Dystonia Coalition cohort. Neurology 2021, 96, e563–e574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panyakaew, P.; Jinnah, H.A.; Shaikh, A.G. Clinical features, pathophysiology, treatment, and controversies of tremor in dystonia. J Neurol Sci 2022, 435, 120199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, N.; Goto, A. Dystonia musculorum deformans. Analysis with electromyography. J Neurol Sci 1971, 13, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S. The varied clinical expressions of dystonia. Neurol Clinics 1984, 2, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S. Atypical tremors, rare tremors and unclassified tremors. In: Findley LJ, Capildeo R, eds. Movement Disorders: Tremor. London: Palgrave Macmillon, 1984:555-563.

- Lalli, S.; Albanese, A. The diagnostic challenge of primary dystonia: Evidence from misdiagnosis. Mov Disord 2010, 25, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G.; Bain, P.; Brin, M. Consensus statement of the movement disorder society on tremor. Mov Disord 1998, 13 (Suppl. 3), 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, W.J.; Shah, B.B. Tremor. JAMA 2014, 311, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, A.; Bhalsing, K.S.; Jhunjhunwala, K.R.; Chandran, V.; Pal, P.K. Are patients with limb and head tremor a clinically distinct subtype of essential tremor? Can J Neurol Sci 2015, 42, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschmann, A.; Wszolek, Z.K. Diagnosis and treatment of common forms of tremor. Semin Neurol 2011, 31, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defazio, G.; Conte, A.; Gigante, A.F.; Fabbrini, G.; Berardelli, A. Is tremor in dystonia a phenotypic feature of dystonia? Neurology 2015, 84, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G. Dystonic tremor. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2003, 159, 900–905. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Lang, A.E. The treatment of dystonic tremor: A systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014, 85, 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Ghika, J.; Bogousslavsky, J.; Henderson, J.; Maeder, P.; Regli, F. The "jerky dystonic unsteady hand": A delayed motor syndrome in posterior thalamic infarctions. J Neurol 1994, 241, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnery, P.F.; Reading, P.J.; McCarthy, E.L.; Curtis, A.; Burn, D.J. Late-onset axial jerky dystonia due to the DYT1 deletion. Mov Disord 2002, 17, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmus, F.; Langseth, A.; Doherty, E.; et al. "Jerky" dystonia in children: Spectrum of phenotypes and genetic testing. Mov Disord 2009, 24, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuukasjarvi, A.; Landoni, J.C.; Kaukonen, J.; et al. IMPDH2: A new gene associated with dominant juvenile-onset dystonia-tremor disorder. Eur J Hum Genet 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loens, S.; Hamami, F.; Lohmann, K.; et al. Tremor is associated with familial clustering of dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2023, 110, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, P.; Skorvanek, M.; Kittke, V.; et al. Dystonia linked to EIF4A2 haploinsufficiency: A disorder of protein translation dysfunction. Mov Disord 2023. [CrossRef]

- Paoli, D.; Mills, R.; Brechany, U.; Pavese, N.; Nicholson, C. DBS in tremor with dystonia: VIM, GPi or both? A review of the literature and considerations from a single-center experience. J Neurol 2023, 270, 2217–2229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stamelou, M.; Charlesworth, G.; Cordivari, C.; et al. The phenotypic spectrum of DYT24 due to ANO3 mutations. Mov Disord 2014, 29, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erro, R.; Stamelou, M.; Saifee, T.A.; et al. Facial tremor in dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014, 20, 924–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuhr, F.; Wissel, J.; Muller, J.; Scholz, U.; Poewe, W. Quantification of sensory trick impact on tremor amplitude and frequency in 60 patients with head tremor. Mov Disord 2000, 15, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, G.; Plagnol, V.; Holmstrom, K.M.; et al. Mutations in ANO3 cause dominant craniocervical dystonia: Ion channel implicated in pathogenesis. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 91, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becktepe, J.; Govert, F.; Balint, B.; et al. Exploring interrater disagreement on essential tremor using a standardized tremor elements assessment. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2021, 8, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Bain, P.G.; Defazio, G.; et al. The conundrum of dystonia in essential tremor patients: How does one classify these cases? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govert, F.; Deuschl, G. Tremor entities and their classification: An update. Curr Opin Neurol 2015, 28, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elble, R.J. What is essential tremor? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elble, R.J. Defining dystonic tremor. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013, 11, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, N.P.; Schneider, S.A.; Schwingenschuh, P.; Bhatia, K.P. Tremor - some controversial aspects. Mov Disord 2011, 26, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Sarma, N. Tremor in dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016, 29, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Sorbo, F.D. Dystonia and tremor: The clinical syndromes with isolated tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2016, 6, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, E.D. The evolving definition of essential tremor: What are we dealing with? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;in press.

- Hopfner, F.; Haubenberger, D.; Galpern, W.R.; et al. Knowledge gaps and research recommendations for essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016, 33, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajalingam, R.; Breen, D.P.; Lang, A.E.; Fasano, A. Essential tremor plus is more common than essential tremor: Insights from the reclassification of a cohort of patients with lower limb tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 56, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, E.D. Essential tremor: "Plus" or "Minus". Perhaps now is the time to adopt the term "the essential tremors". Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 56, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Pal, P.K. Reclassifying essential tremor: Implications for the future of past research. Mov Disord 2019, 34, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A. Classifying tremor: Language matters. Mov Disord 2018, 33, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Lang, A.E.; Espay, A.J. What is "essential" about essential tremor? A diagnostic placeholder. Mov Disord 2018, 33, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, C.; Espay, A.J.; Lang, A.E.; et al. Soft signs in movement disorders: Friends or foes? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019, 90, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, A.; Munchau, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Quinn, N.P.; Marsden, C.D. Essential tremor: An overdiagnosed condition? J Neurol 2000, 247, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Lo, S.E.; Louis, E.D. Common misdiagnosis of a common neurological disorder: How are we misdiagnosing essential tremor? Arch Neurol 2006, 63, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.A.; Edwards, M.J.; Mir, P.; et al. Patients with adult-onset dystonic tremor resembling parkinsonian tremor have scans without evidence of dopaminergic deficit (SWEDDs). Mov Disord 2007, 22, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, A.; Lalli, S. Is this dystonia? Mov Disord 2009, 24, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiebler, S.; Schmidt, A.; Zittel, S.; et al. Arm tremor in cervical dystonia: Is it a manifestation of dystonia or essential tremor? Mov Disord 2011, 26, 1789–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, F. Difficult diagnoses in hyperkinetic disorders - a focused review. Front Neurol 2012, 3, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepitskaya, O.; Neuwelt, A.J.; Nguyen, T.; Leehey, M. Primary dystonia misinterpreted as Parkinson disease: Video case presentation and practical clues. Neurol Clin Pract 2013(6):469-474.

- Testa, C.M. Key issues in essential tremor genetics research: Where are we now and how can we move forward? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2013;3.

- Macerollo, A.; Superbo, M.; Gigante, A.F.; Livrea, P.; Defazio, G. Diagnostic delay in adult-onset dystonia: Data from an Italian movement disorder center. J Clin Neurosci 2015, 22, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.D. Tremor. Continuum 2019, 25, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, T.; Au, K.L.K.; Deeb, W.; et al. Motor outcomes and adverse effects of deep brain stimulation for dystonic tremor: A systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020, 76, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, S.; Becktepe, J.S.; Hobert, M.A.; et al. The challenge of choosing the right stimulation target for dystonic tremor: A series of instructive cases. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2023, 10, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picillo, M.; Paramanandam, V.; Morgante, F.; et al. Dystonia as complication of thalamic neurosurgery. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2019, 66, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Beach, J.; Pandolfo, M.; Patel, P.I. Familial essential tremor in 4 kindreds. Prospects for genetic mapping. Arch Neurol 1997, 54, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatunov, A.; Sambuughin, N.; Jankovic, J.; et al. Genomewide scans in North American families reveal genetic linkage of essential tremor to a region on chromosome 6p23. Brain 2006, 129, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedera, P.; Phibbs, F.T.; Fang, J.Y.; Cooper, M.K.; Charles, P.D.; Davis, T.L. Clustering of dystonia in some pedigrees with autosomal dominant essential tremor suggests the existence of a distinct subtype of essential tremor. BMC Neurol 2010, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.D.; Hernandez, N.; Alcalay, R.N.; Tirri, D.J.; Ottman, R.; Clark, L.N. Prevalence and features of unreported dystonia in a family study of "pure" essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013, 19, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apartis, E.; Vercueil, L. To jerk or not to jerk: A clinical pathophysiology of myoclonus. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2016, 172, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.G.; Wong, A.L.; Zee, D.S.; Jinnah, H.A. Keeping your head on target. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 11281–11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.G.; Zee, D.S.; Jinnah, H.A. Oscillatory head movements in cervical dystonia: Dystonia, tremor, or both? Mov Disord 2015, 30, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beylergil, S.B.; Singh, A.P.; Zee, D.S.; Jinnah, H.A.; Shaikh, A.G. Relationship between jerky and sinusoidal oscillations in cervical dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2019, 66, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwhof, F.; Toni, I.; Buijink, A.W.G.; van Rootselaar, A.F.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.C.; Helmich, R.C. Phase-locked transcranial electrical brain stimulation for tremor suppression in dystonic tremor syndromes. Clin Neurophysiol 2022, 140, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elble, R.J.; Moody, C.; Higgins, C. Primary writing tremor. A form of focal dystonia? Mov Disord 1990, 5, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panyakaew, P.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Wu, T.; Hallett, M. The pathophysiology of dystonic tremors and comparison with essential tremor. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 9317–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Bhattad, S.; Hallett, M. The problem of questionable dystonia in the diagnosis of 'essential tremor-plus'. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Bhattad, S. Questionable dystonia in essential tremor plus: A video-based assessment of 19 patients. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2019, 6, 722–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionco, J.T.; Hartstone, W.G.; Martuscello, R.T.; Kuo, S.H.; Faust, P.L.; Louis, E.D. Essential tremor versus "ET-plus": A detailed postmortem study of cerebellar pathology. Cerebellum 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, E.D. Rising problems with the term "ET-plus": Time for the term makers to go back to the drawing board. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivest, J.; Marsden, C.D. Trunk and head tremor as isolated manifestations of dystonia. Mov Disord 1990, 5, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedynak, C.P.; Bonnet, A.M.; Agid, Y. Tremor and idiopathic dystonia. Mov Disord 1991, 6, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkmeier-Kraemer, J.M. Isolated voice tremor: A clinical variant of essential tremor or a distinct clinical phenotype? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2020;10.

- Rosenbaum, F.; Jankovic, J. Focal task-specific tremor and dystonia: Categorization of occupational movement disorders. Neurology 1988, 38, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L.; Batla, A.; Berardelli, A.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P. The signature of primary writing tremor is dystonic. Mov Disord 2021;in press.

- Deuschl, G.; Heinen, F.; Guschlbauer, B.; Schneider, S.; Glocker, F.X.; Lucking, C.H. Hand tremor in patients with spasmodic torticollis. Mov Disord 1997, 12, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munchau, A.; Schrag, A.; Chuang, C.; et al. Arm tremor in cervical dystonia differs from essential tremor and can be classified by onset age and spread of symptoms. Brain 2001, 124, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.G.; Jinnah, H.A.; Tripp, R.M.; et al. Irregularity distinguishes limb tremor in cervical dystonia from essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat 2008, 79, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic-Berkmen, G.; Pirio Richardson, S.; Perlmutter, J.S.; et al. Current guidelines for classifying and diagnosing cervical dystonia: Empirical evidence and recommendations. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2021, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, A.; Gupta, P.; Jacobs, J.; et al. Impaired saccade adaptation in tremor-dominant cervical dystonia: Evidence for maladaptive cerebellum. Cerebellum 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Schroder, L.; Rekhtman, A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Wang, L.L.; Espay, A.J. Tremor-dominant cervical dystonia: A cerebellar syndrome. Cerebellum 2021, 20, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Cardoso, F.; et al. Isolated cervical dystonia: Diagnosis and classification. Movement Disorders 2023, 38, 1367–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Vu, J.P.; Cisneros, E.; et al. Postural directionality and head tremor in cervical dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov 2020;10.

- Kachi, T.; Rothwell, J.C.; Cowan, J.M.; Marsden, C.D. Writing tremor: Its relationship to benign essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985, 48, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.G.; Hallett, M. Hand cramps: Clinical features and electromyographic patterns in a focal dystonia. Neurology 1988, 38, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G.; Heinen, F.; Kleedorfer, B.; Wagner, M.; Lucking, C.H.; Poewe, W. Clinical and polymyographic investigation of spasmodic torticollis. J Neurol 1992, 239, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, P.G.; Findley, L.J.; Britton, T.C.; et al. Primary writing tremor. Brain 1995, 118, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Sole, J.; Tolosa, E.S.; Nobbe, F.; et al. Neurophysiological investigations in patients with head tremor. Mov Disord 1997, 12, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, P.; Edwards, M.; Tijssen, M.A.; et al. Patterns of EMG-EMG coherence in limb dystonia. Mov Disord 2004, 19, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, D.A.; Maronian, N.C.; Waugh, P.F.; Shahinfar, A.; Robinson, L.; Hillel, A.D. Findings of multiple muscle involvement in a study of 214 patients with laryngeal dystonia using fine-wire electromyography. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2004, 113, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, J.P.; Lee, H.Y.; Chen, Q.; et al. Head tremor and pain in cervical dystonia. J Neurol 2021;in press.

- Biase, L.; Brittain, J.-S.; Shah, S.A.; et al. Tremor stability index: A new tool for differential diagnosis in tremor. Brain 2017;in press.

- Balachandar, A.; Algarni, M.; Oliveira, L.; et al. Are smartphones and machine learning enough to diagnose tremor? J Neurol 2022, 269, 6104–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.G.; Zee, D.S.; Crawford, J.D.; Jinnah, H.A. Cervical dystonia: A neural integrator disorder. Brain 2017, 139, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.A.; Littlewort, G.C.; Bartlett, M.S.; et al. Objective, computerized video-based rating of blepharospasm severity. Neurology 2016, 87, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Ford, J. Blepharospasm and orofacial-cervical dystonia: Clinical and pharmacological findings in 100 patients. Ann Neurol 1983, 13, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Brin, M.F.; Fahn, S. Idiopathic cervical dystonia: Clinical characteristics. Mov Disord 1991, 6, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Leder, S.; Warner, D.; Schwartz, K. Cervical dystonia: Clinical findings and associated movement disorders. Neurology 1991, 41, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, R.M.; Gray, C.S.; Koller, W.C. Essential tremor and dystonia. Neurology 1993, 43, 2382–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.K.; Samii, A.; Schulzer, M.; Mak, E.; Tsui, J.K. Head tremor in cervical dystonia. Can J Neurol Sci 2000, 27, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweinfurth, J.M.; Billante, M.; Courey, M.S. Risk factors and demographics in patients with spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisch, S.H.D.; Brake, H.M.; Law, M.; Cole, I.E.; Darveniza, P. Spasmodic dysphonia: Clinical features and effects of botulinum toxin therapy in 169 patients - an Australian experience. J Clin Neurosci 2003, 10, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeiro-Junior, C.; Felicio, A.C.; Aguiar, P.C.; Borges, V.; Silva, S.M.; Ferraz, H.B. Head tremor in patients with cervical dystonia: Different outcome? Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2008, 66, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, L.J.; Klein, A.M.; Hapner, E.R.; et al. Coprevalence of tremor with spasmodic dysphonia: A case-control study. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1752–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defazio, G.; Gigante, A.F.; Abbruzzese, G.; et al. Tremor in primary adult-onset dystonia: Prevalence and associated clinical features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013, 84, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erro, R.; Rubio-Agusti, I.; Saifee, T.A.; et al. Rest and other types of tremor in adult-onset primary dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013, 85, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzinska, M.; Krawczyk, M.; Wojcik-Pedziwiatr, M.; Szczudlik, A.; Wasielewska, A. Tremor associated with focal and segmental dystonia. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2013, 47, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Sarma, N. Tremor in dystonia: A cross-sectional study from India. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2017, 4, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvizdosova, L.; Nevrly, M.; Otruba, P.; Hlustik, P.; Kanovsky, P.; Zapletalova, J. The prevalence of dystonic tremor and tremor associated with dystonia in patients with cervical dystonia. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kreisler, A.; Druzdz, A.; et al. Tremor in idiopathic cervical dystonia - Possible implications for botulinum toxin treatment considering the col-cap classification. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2020, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).