1. Introduction

AUL is a shrub species that produces red fruits (

Figure 1) and belongs to the Ericaceae family. The literature reports that AUL fruits contain numerous phenolic acid derivatives [

1,

2], as well as vitamins E and C and important minerals [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, it can be concluded that AUL fruits possess strong antioxidant properties.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are free radicals that originate from oxygen, while reactive nitrogen species (RNS) originate from nitrogen. The increase in ROS during metabolism disrupts the balance between antioxidants and oxidants. Endogenous antioxidants attempt to restore this balance by increasing their levels. However, if the amount of free radicals exceeds the capacity of antioxidants to balance them, oxidative stress occurs. Cell and tissue damage occurs when oxidative stress exceeds the tolerable level, which should be noted is a level that can be tolerated up to a certain extent [

7].

Apoptosis is the process of eliminating cells that have completed their function or whose DNA has been damaged, without harming the surrounding cells and tissues. This process occurs throughout life. For instance, during embryonic development, the cells between the fingers and toes undergo programmed cell death, resulting in the separation of the digits. Similarly, the regression of the mammary gland after lactation and organ atrophy in old age are physiological examples of apoptosis. Cell deaths occurring in ischemic diseases, such as radiation, chemotherapy, hypoxia, and myocardial infarction (MI), are defined as pathological apoptosis [

8,

9,

10]. Formaldehyde is a highly reactive chemical compound in the aldehyde group that causes oxidative stress.

The aim of this study was to investigate the positive effects of AUE containing antioxidant compounds in rat hippocampus induced oxidative stress and apotosis by FA, which is known to have negative effects on the nervous system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Collection

Fruits of A.unedo L. were collected in November 2021 from Sakarya, Turkey. The plant was identified by Dr. Zuhal Sahin, an organic chemist at Sakarya University.

2.2. Extract Preparation

AUL fruits collected from the western black sea coast in season were dried and preserved by Freeze Drying method. AUL fruit was homogenised with methyl alcohol at 18000 rpm and extracted under room conditions. The filtrate was removed using a rotary evaporator after the extracts were filtered to dryness under vacuum in a Buhner funnel.

2.3. Determination of Phenolic Content

The HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) method was used to determine the analytical percentages of antioxidant phenolic compounds in the obtained AUE. The analysis was performed in triplicate using the Shimadzu LC-20A HPLC device.

Table 1 shows the average values of gallic acid, epicatechin, catechin, and resveratrol obtained from the three repetitions.

2.4. Experimental Design and Animal Treatments

The study used adult female Wistar rats (Experimental Medical Research and Application Center, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey) weighing 250-300 g. The rats were housed in an animal colony at a density of approximately 8 to 9 per cage for 2 weeks prior to the experiments. Before starting the experiment, the rats' body weights were measured and recorded (239.13± 13.26 g). The study's experiments were conducted in compliance with the Regulation of Animal Research Ethics Committee in Turkey (July 6, 2006, Number 26220). The Kocaeli University Animal Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval (Project number: HADYEK 2021/17, Kocaeli, Turkey).

The study randomly selected animals and divided them into four groups, each containing nine rats. The tails of the rats in each group were painted different colours. Group I was designated as the Control Group (CG), Group II as the Experimental Group (EG), Group III as the Formaldehyde Group (FAG), and Group IV as the Sham Group (SG). The experimental period lasted for five weeks, accounting for inhalation and gavage losses.

Nine rats were assigned to each of the following groups: CG, EG, SG, and FAG. The rats in the CG group were exposed to normal air, while the rats in the EG group were given 20mg of lyophilized A.Unedo L. extract (AUE) by oral gavage along with 10ppm FA for 4 hours daily, five days a week. The rats in the SG group were given 10mg of AU extract by oral gavage daily for 30 days. The rats in the FAG group were exposed to subacute FA (10 ppm FA) for 4 hours a day, five days a week throughout the experiment.

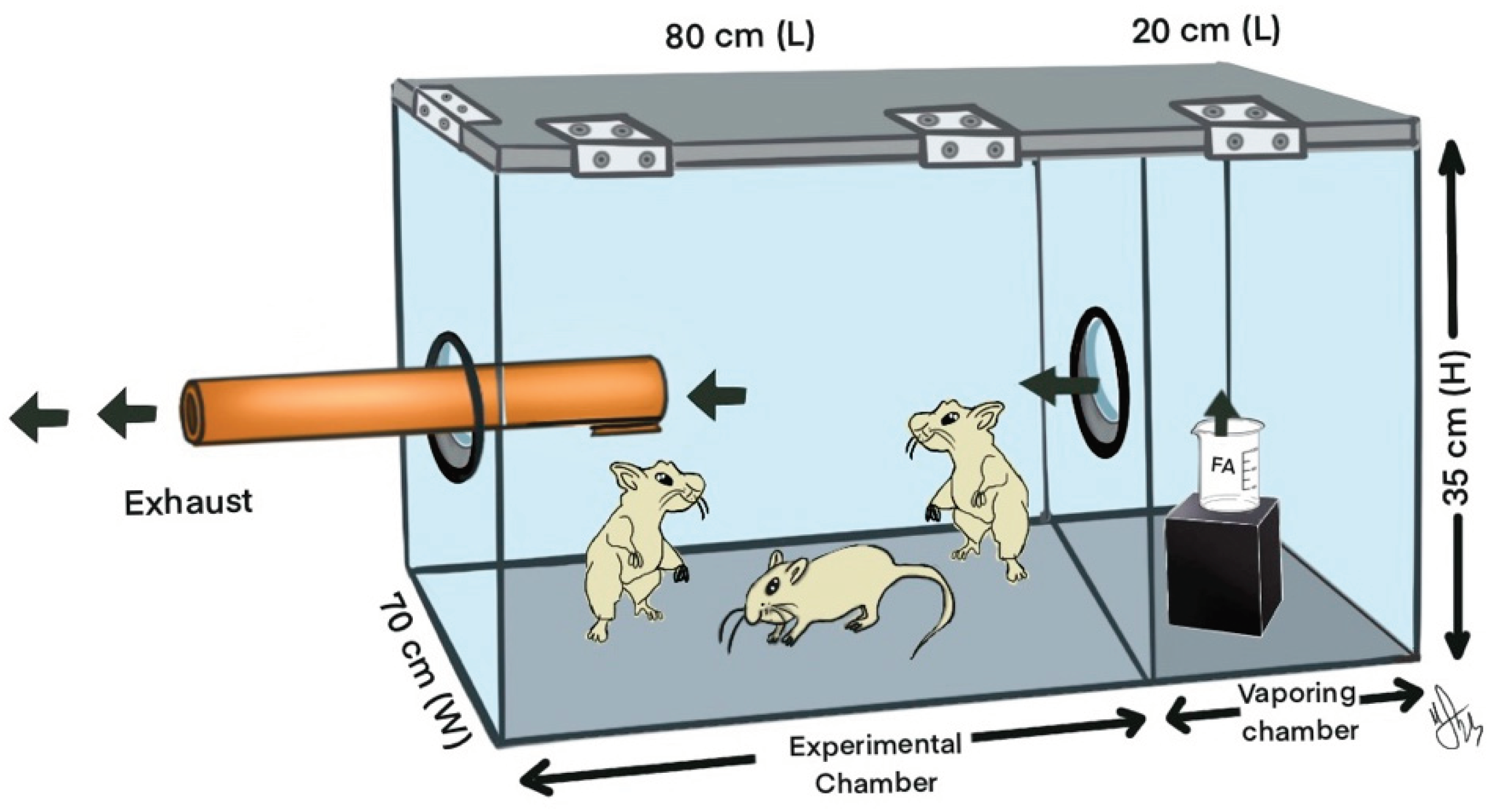

A glass experimental chamber was prepared, with dimensions of 100cm (length) x 70cm (width) x 35cm (height), following Matsuoka's methodology [

11]. The chamber was divided into two compartments: the experimental chamber and FA evaporation, as shown in

Figure 2.

Formaldehyde is passed through a small hole of 6 cm diameter between the two compartments. The reason for preferring the glass chamber is to be able to monitor the adverse situations that can develop in rats due to exposure to FA, which is highly toxic.

A Honeywell ToxiRAE PRO (HCHO) dosimeter was used to monitor levels of the volatile gas FA throughout the experiment, which lasted an average of 4 hours per day. When the level of FA in the environment fell below 10 ppm, the container of FA was replaced with a new one. To obtain reliable values, the dosimeter was calibrated each day before the start of the experiment.

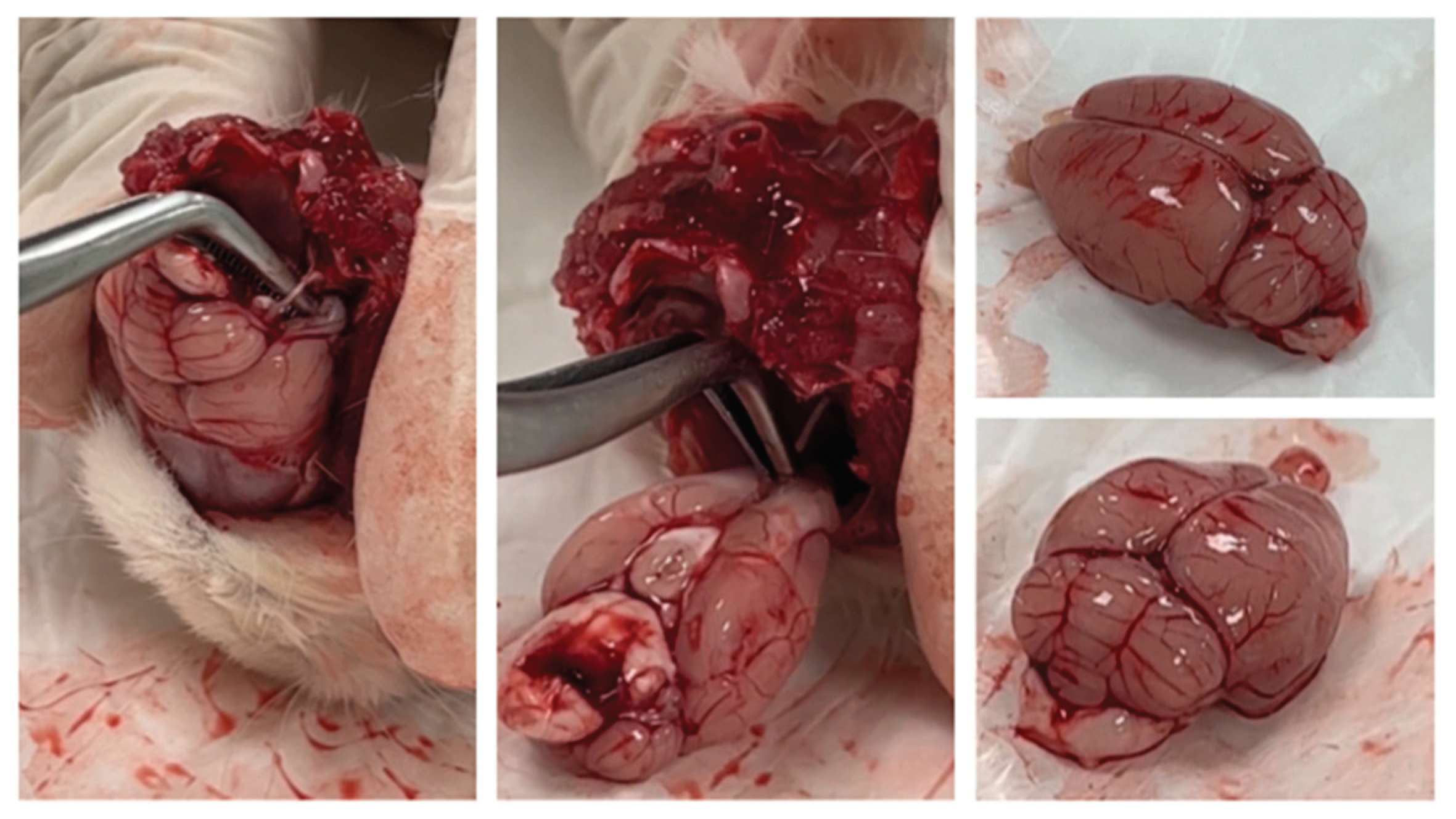

The experiment was terminated at the end of the fifth week. At the end of the experiment, all rats were sacrificed after blood sampling under deep anaesthesia. Brain tissue from the sacrificed rats was removed using the isolation technique according to the procedure (

Figure 3).

2.5. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

GSH, NO determination and BDNF and MDA analysis were performed on the blood samples obtained. 4 μm thick sections were cut from brain tissue embedded in paraffin blocks. Immunohistochemical labelling with caspase-3 antibody was performed to detect apoptosis in the obtained hippocampal sections. H-score analysis was performed using the cell numbers obtained from caspase-3 labelling of the groups in the experiment.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 21 statistical software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare response groups. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test to examine significant differences in mean histopathological lesion scores.

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Findings of Hippocampus Tissue

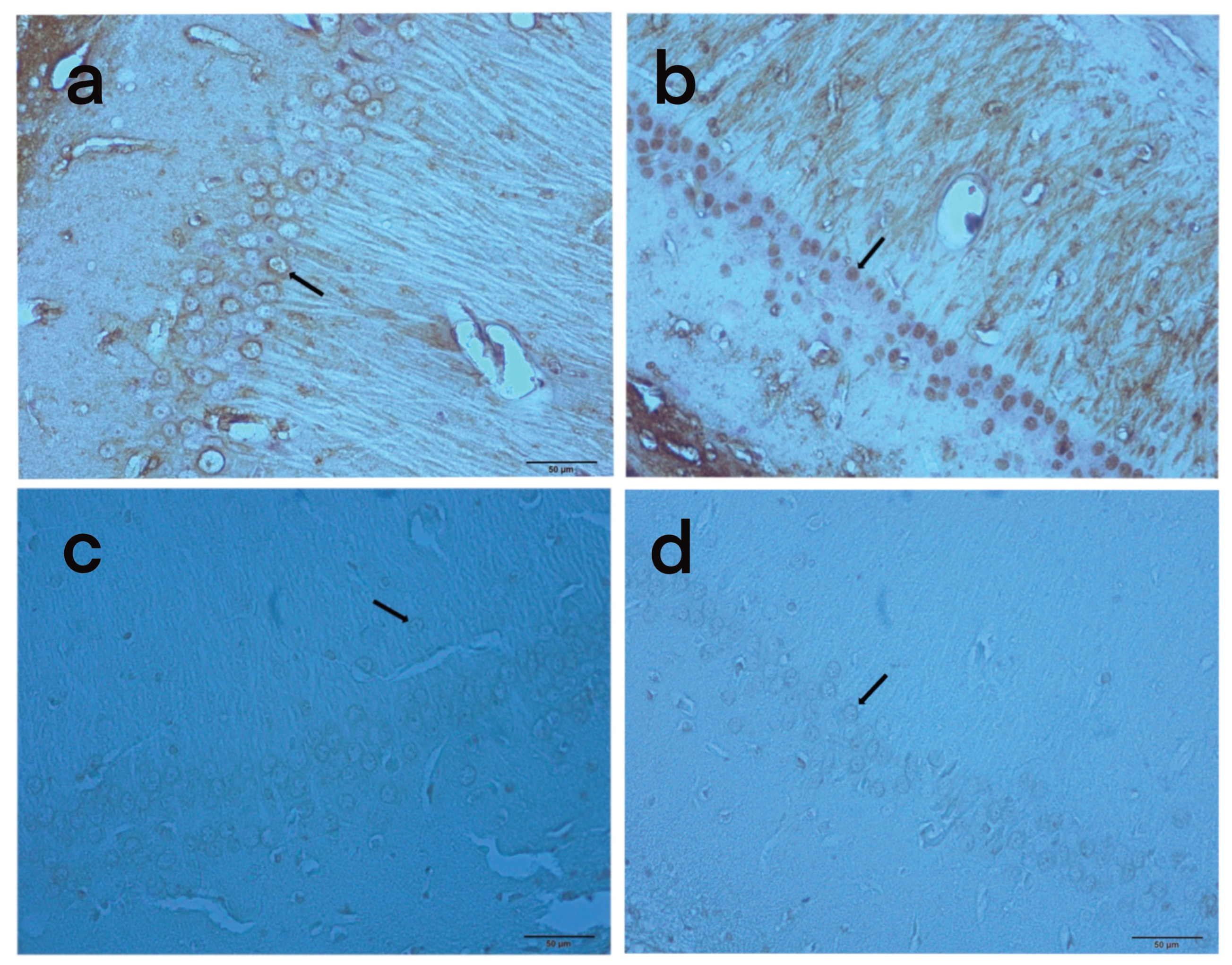

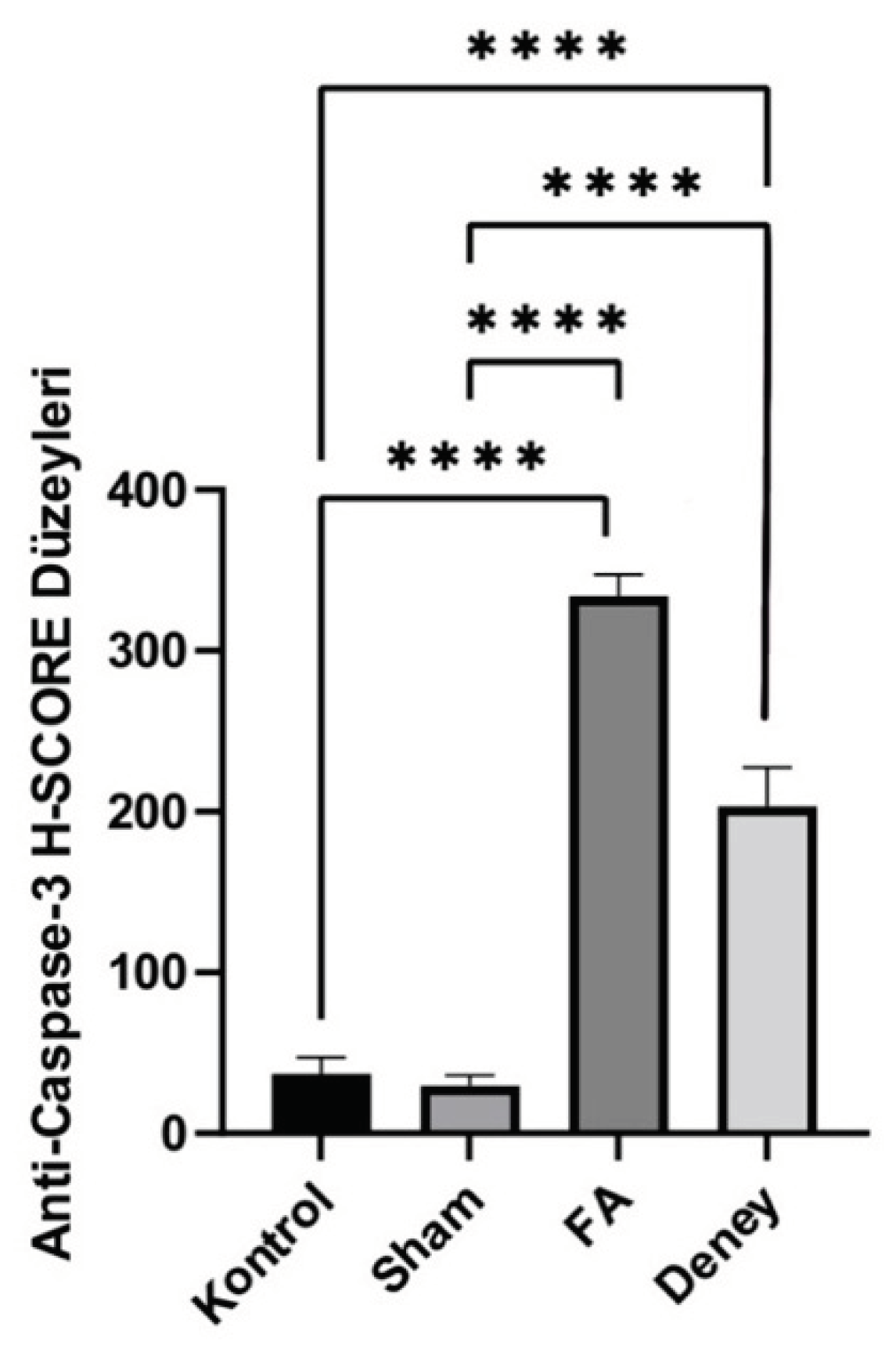

In the hippocampus of rats that we induced oxidative stress and apoptosis with FA; neuronal cells of brain tissue were morphologically examined to show the effects of Arbutus Unedo L. extract. In anti-caspase-3 positive staining, differences were observed between the rate of apoptosis in the experimental and sham groups and the rate of apoptotic cells between the FA and control groups (

Figure 4).

In the immunohistochemical images obtained, apoptotic cells surrounded by shrunken membranes are visible in the hippocampal sections of FG and EG rats (

Figure 4a,

Figure 4b). The changes in the nuclear structure of these groups in the microscopic images confirmed apoptosis and oxidative stress. When the microscopic images of FG and EG rats were compared, it was observed that the cell shape with the specified characteristics was present in FG. According to the H-score values, the number of apoptotic cells is higher in FG than in DG, indicating that AUE has a neuroprotective effect (

Figure 5).

3.1. Biochemical Analysis Results

Serum BDNF, MDA, GSH and NO values were analysed in the biochemical analysis of rat sera.

In the comparison of MDA, BDNF, NO, GSH and H-score results according to the groups, a significant difference was found between the groups in MDA, NO and H-score (p<0.05, p<0.05 and p<0.001) (

Table 2).

In the pairwise group comparisons of MDA, NO and H-score values, no significant difference was found between the groups for BDNF and GSH (p>0.05, p>0.05) (

Table 3).

As a result of pairwise group comparison tests, the MDA values of the Sham group were found to be significantly lower than both the Experiment and FA groups (p<0.05, p<0.05). When the average MDA values of the groups are examined, the lowest MDA value is found in the sham group, while the highest MDA value is found in the FA group. The oxidative stress inducing effect of FA is clear. It was observed that the average MDA values tended to decrease in the sham and experimental groups to which A unedo L extract was applied. It was found that A unedo L extract applied to the experimental group tended to reduce the oxidative stress caused by FA, but this reduction was not significant. The MDA level of A unedo L extract applied to healthy rats was lower than the control group average, resulting in a significant difference in MDA level between the experimental and FA groups.

BDNF plays an important role in the plasticity, regeneration and memory functions of cells in the brain. On average, BDNF was lowest in the sham group and highest in the control group. However, there was no significant difference between the groups. (p>0.05) The lower average level of BDNF in the FA group compared to the control group may be related to the impairment of memory functions due to FA. It can be said that A undeo L extract partially corrects the negative effects of FA on BDNF. However, studies with larger samples are needed to confirm this.

When NO levels are examined, the group with the lowest average is the FA group and the highest is the control group. The NO levels of the experimental and FA groups were found to be significantly lower than those of the control group (p<0.05, p<0.01). However, as there is no significant difference in NO between the experimental and FA groups, it can be said that A undeo L extract does not contribute to the formaldehyde-induced decrease in NO levels.

The group means for GSH were very close to each other and there was no significant difference between the groups (p>0.05). It can be said that GSH levels were not affected in rats in the FA environment and A undeo L extract did not have a regulatory effect on GSH levels.

When the H-scores, which express the number of apoptotic cells in the brain, were analysed, it was found that both the experimental and FA groups were significantly higher than the control and sham groups. The highest average number of dead cells in the FA group and the fact that both the sham and control groups contained significantly fewer dead cells than the experimental and FA groups suggest that formaldehyde damage to the hippocampus. Although the experimental group had a lower average number of dead cells than the FA group, this difference was not found to be significant. Although the average number of dead cells in the sham group was lower than in the control group, this difference was not found to be significant. However, it can be said that A undeo L extract tends to slow down cell death in the brain.

Correlation analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between MDA and H-score (p<0.001) (

Table 4). The strong positive correlation between oxidative stress indicator MDA and H-score, which expresses cell death in brain tissue, shows that oxidative stress induces apoptosis in the brain. However, no significant difference was found between BDNF, NO and GSH and H-score. (p>0.05, p>0.05 and p>0.05)

4. Discussion

Inhalation shows acute and chronic effects, particularly in the respiratory tract, eyes, CNS and skin [

12]. FA can be found endogenously in living organisms as well as through environmental exposure [

13].

Studies with FA have shown yellowing of the fur of rats exposed to inhaled FA [

14] and movements such as avoiding left and right and closing in on each other during exposure [

15]. In our study, in parallel with the literature, similar avoidance and yellowing of feathers, increased eye blinking and initial avoidance of movement were observed; slowing of movement in the following minutes was among the physical observations noted.

FA causes toxicological and carcinogenic effects by triggering the formation of reactive oxygen species [

16]. A study has shown that FA, which has effects on many cellular pathways, slows motor activity by causing neurodegenerative changes in the CNS [

17]. In our study, rats in groups exposed to FA; while motor movements were normal before exposure, the observation of slowed movements after exposure confirms this explanation.

In a study where MDA, an indicator of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, was used as a parameter, it was observed that the MDA level increased significantly in the FA exposed group [

18]. Similarly, in our study the highest MDA level was found in the FA group. This can be interpreted as oxidative damage occurring most in the FA group.

It was observed that the MDA level tended to decrease in the experimental and sham groups where Arbutus Unedo L. extract, a powerful antioxidant, was applied. In this case, it can be explained that AUE is effective in balancing oxidative damage. The fact that the sham group had the lowest MDA value in the evaluation of all the groups can be interpreted as the fact that there is currently no factor affecting the balance between ROS and antioxidants and that AUE has positive effects on the changes that occur in the natural apoptosis process.

One study reported that oxidative stress in brain tissue increased in the group of rats exposed to FA and parallel DNA damage [

19]. According to the results of our study, the highest oxidative damage was found in the FA group.

A study conducted in 2013 reported degenerations related to learning and memory and an increase in the number of apoptotic cells in the hippocampal region in rats exposed to FA [

20]. In our study, a relationship was established between the apoptotic cell index and neuronal damage in the immunohistochemical evaluations of FG and DG due to FA exposure. Apoptotic cell indices in the CA3 region of the hippocampus were found to be significantly higher in FG and DG rats than in SG and CG.

In cells undergoing apoptosis, the cytoplasm begins to shrink and contract. With the degradation of some structural proteins, the nucleus begins to condense and usually the nuclear chromatin is displaced towards the inner side of the nuclear membrane, taking on a shape similar to a horseshoe or the letter C [

21]. In the immunohistochemical images obtained in our study, apoptotic cells surrounded by shrunken membrane were visible in the hippocampal sections of FG and DG rats. The apoptotic changes in the nuclear structure of these groups in both microscopic imaging and H-score analysis confirmed the above statement. When the microscopic images of FG and DG rats were compared, it was observed that the cell shape with the specified characteristics was present in FG. According to the H-score values, the number of apoptotic cells is higher in FG than in DG, indicating that AUE has a neuroprotective effect.

There is a positive correlation between oxidative stress and GSH levels. If we look at the literature, animal studies show that when oxidative stress increases, so do GSH levels increase [

22]. In contrast to the literature, in our study the mean values of the groups in terms of GSH levels were very close to each other and no significant difference was found between the groups. This can be interpreted as GSH levels are not affected in rats in the FA environment and A Undeo L extract does not have a regulatory effect on GSH levels.

5. Conclusions

According to the results of our study, there was a correlation between FA exposure and apoptosis, in line with the literature. A significant increase in the rate of apoptotic cells was observed in hippocampal tissues due to formaldehyde exposure compared to other groups.

Biochemical and histological data showed that cell death was reduced in the groups given Arbutus Unedo L extract compared to the groups not given the extract.

FA is a highly reactive free radical commonly used in cadaver embalming laboratories. According to literature data, occupational groups working with FA have negative effects on the nervous system, especially in groups with chronic exposure. We believe that a multi-faceted study of high antioxidant content, such as AUL, which can minimise the degenerative effects of FA on the hippocampus, which is involved in learning and memory, may help to prevent damage that may occur at the cellular level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mehtap Erdogan.; methodology, Mehtap Erdogan; validation, Sema Kurnaz Ozbek, Ozgur Doga Ozsoy.; formal analysis; Tuncay Colak; resources, Zuhal Sahin.; data curation, Ozgur Doga Ozsoy; writing—original draft preparation —Mehtap Erdogan; writing—review and editing, Mehtap Erdogan, Tuncay Colak; visualization, Mehtap Erdogan, Sema Kurnaz Ozbek.; supervision, Tuncay Colak, Fatma Sureyya Ceylan, Hale Maral Kır.; project administration, Tuncay Colak. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by Kocaeli University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit [Project No. 2021/2706].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kocaeli University Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments (KOU HADYEK) (protocol code: KOU HADYEK 7/2-2021, date of approval: [10.09.21]).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Ethical review and approval were obtained from Kocaeli University Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments (KOU HADYEK) (protocol code: KOU HADYEK 7/2-2021, date of approval: [10.09.21]).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ayaz, F.A.; Kucukislamoglu, M.; Reunanen, M. Sugar, Non-volatile and Phenolic Acids Composition of Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo L. var.ellipsoidea) Fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallauf, K.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; del Castillo, M.D.; Cano, M.P.; de Pascual-Teresa, S. Characterization of the antioxidant composition of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabuçcuoğlu, A.; Kivçak, B.; Baş, M.; Mert, T. Antioxidant activity of Arbutus unedo leaves. Fitoterapia 2003, 74, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G.; Faleiro, M.L.; Guerreiro, A.C.; Antunes, M.D. Arbutus unedo L.: Chemical and biological properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 15799–15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, M.M.; Hacıseferoğulları, H. The Strawberry (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits: Chemical composition, physical properties and mineral contents. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olveria, I.; Baptista, P.; Malherio, R.; Casal, A.; Pereira, J.A. Influence of Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruit ripening stage on chemical composition and antioxidant activity. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Lee, M.G. Oxidative stress and antioxidant strategies in dermatology. Redox Rep. 2016, 21, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistritto, G.; Trisciuoglio, D.; Ceci, C.; Garufi, A.; D'Orazi, G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: Function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging 2016, 8, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiess, W.; Gallaher, B. Hormonal control of programmed cell death/apoptosis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1998, 138, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, T.; Takaki, A.; Ohtaki, H.; Shioda, S. Early changes to oxidative stress levels following exposure to formaldehyde in ICR mice. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 35, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, D.; Mansour, N.; Taha, F.; Seif El Dein, A. Assessment of lipid peroxidation and p53 as a biomarker of carcinogenesis among workers exposed to formaldehyde in the cosmetic industry. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, H.D.; Casanova-Schmitz, M.; Dodd, P.B.; Schachter, E.N.; Witek, T.J.; Tosun, T. Formaldehyde (CH2O) concentrations in the blood of humans and Fischer-344 rats exposed to CH2O under controlled conditions. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1985, 46, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, A.; Bouley, G.; Godin, J.; Boudène, C.; Girard, F. Inhalation, en continu, de faibles doses de formaldéhyde: Etude expérimentale chez le rat [Continuous inhalation of small amounts of formaldehyde: Experimental study in the rat]. Eur. J. Toxicol. Environ. Hyg. 1976, 9, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xi, R.; McLaughlin, S.; Salcedo, E.; Tizzano, M. The Nasal Solitary Chemosensory Cell Signaling Pathway Triggers Mouse Avoidance Behavior to Inhaled Nebulized Irritants. eNeuro 2023, 10, ENEURO.0245-22.2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.Q.; Ren, Y.K.; Chen, R.Q.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Fang, H.R.; Xu, J.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Hu, B. Formaldehyde induces neurotoxicity to PC12 cells involving inhibition of paraoxonase-1 expression and activity. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 38, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boja, J.W.; Nielsen, J.A.; Foldvary, E.; Truitt, E.B., Jr. Acute low-level formaldehyde behavioural and neurochemical toxicity in the rat. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1985, 9, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zararsiz, I.; Kus, I.; Akpolat, N.; Songur, A.; Ogeturk, M.; Sarsilmaz, M. Protective effects of omega-3 essential fatty acids against formaldehyde-induced neuronal damage in prefrontal cortex of rats. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 2006, 24, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciftci, G.; Aksoy, A.; Cenesiz, S.; et al. Therapeutic role of curcumin in oxidative DNA damage caused by formaldehyde. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2015, 78, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Q.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Zhang, P.; et al. Formaldehyde impairs learning and memory involving the disturbance of hydrogen sulfide generation in the hippocampus of rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013, 49, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump, B.F.; Berezesky, I.K.; Chang, S.H.; Phelps, P.C. The pathways of cell death: Oncosis, apoptosis, and necrosis. Toxicol. Pathol. 1997, 25, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.J.; Houston, M.; Anderson, J. Increased levels of glutathione in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993, 147 Pt 1, 1461–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).