1. Introduction

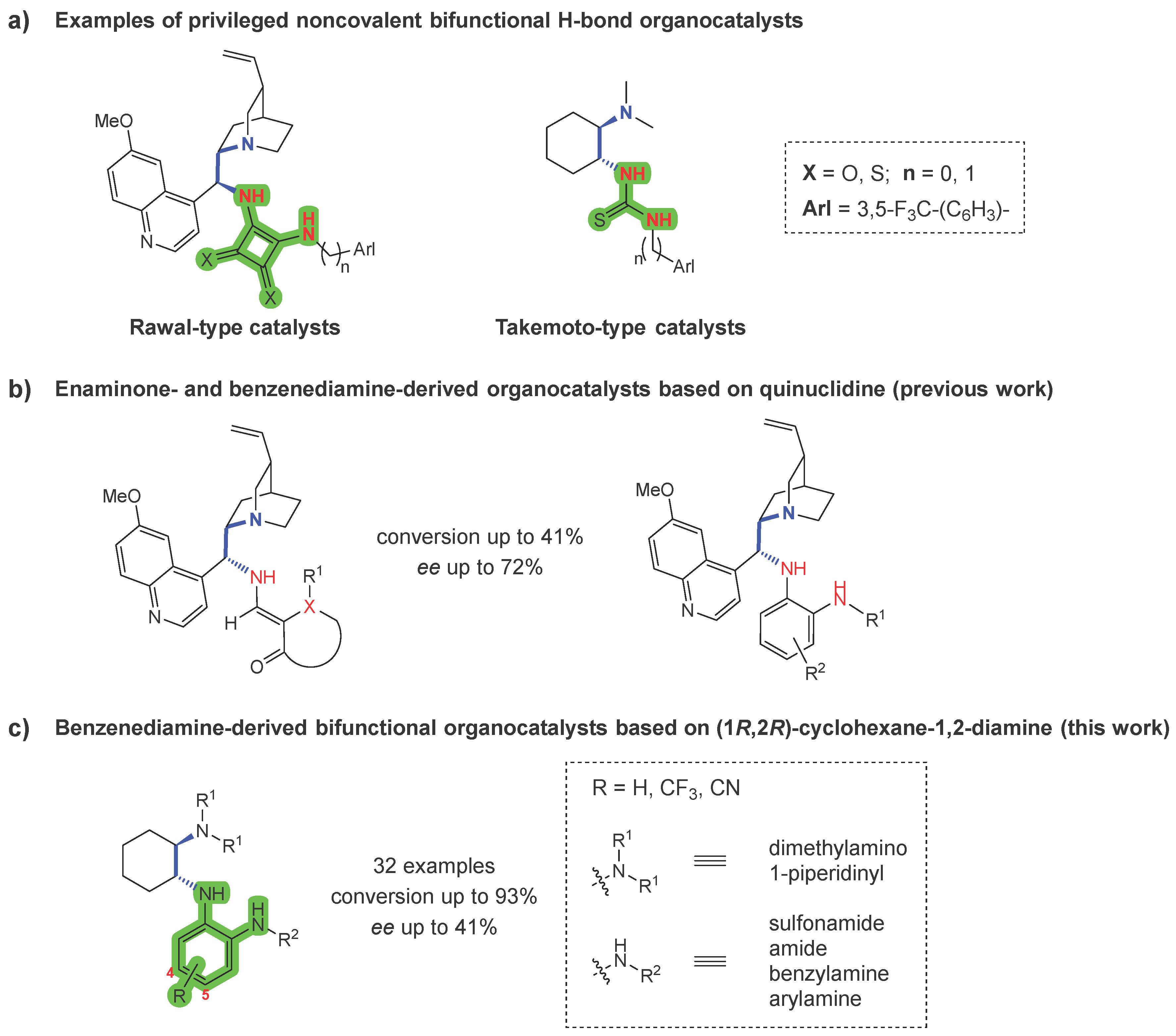

Since the introduction of the noncovalent bifunctional organocatalyst with thiourea double H-bond donor by Takemoto in 2003 [

1,

2], followed by a squaramide analogue developed by Rawal in 2008 [

3,

4], this class of catalysts has become the workhorses of noncovalent organocatalysis [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], as it enables the simultaneous activation and coordination of both nucleophilic and electrophilic reactants [

9,

10]. A typical and most commonly used organocatalyst of this type is a derivative of a chiral 1,2-diamine based on privileged cinchona alkaloids [

11,

12,

13] or cyclohexane-1,2-diamine (

Figure 1a) [

14]. While several double H-bond donors such as diaminomethylenemalononitrile (DMM) [

15,

16] and (heterocyclic) guanidines [

17] as well as single H-bond donors such as (thio)amides [

18], sulfonamides [

19] and phosphoramides [

20] have been described in the literature, thiourea and squaramide remain the most common and best H-bond donors [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

21,

22]. They have also been very successfully introduced into noncovalent bifunctional quaternary ammonium salt phase-transfer organocatalysts [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Recently, we reported the facile two- and three-step synthesis of 24 novel bifunctional noncovalent organocatalysts based on a chiral (

S)-quininamine scaffold and enaminone or benzene-1,2-diamine as novel H-bond donors (

Figure 1b). Their catalytic activity was evaluated in the Michael addition of acetylacetone to

trans-β-nitrostyrene. The catalysts were characterized by low to moderate enantioselectivity (up to 72%

ee) at low conversions (up to 41%) [

27]. Furthermore, no

N-arylated (3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) and

N-benzylated (3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl) catalysts could be prepared. In extension of this study, we report here the synthesis of benzenediamine-derived bifunctional organocatalysts based on chiral cyclohexane-1,2-diamine prepared in four simple steps starting from commercially available (1

R,2

R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine and

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene derivatives. The common aromatic primary amine intermediates enabled the preparation of four subclasses of catalysts,

i.e. sulfonamides, amides, benzylated amines and arylated amines (

Figure 1c). Their organocatalytic activity was investigated in the 1,4-addition of acetylacetone to

trans-β-nitrostyrene. Dimethylamine and piperidine were evaluated as tertiary amines, while trifluoromethyl (

i.e. 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl group) and/or cyano groups were introduced into the catalysts at strategic positions to increase the H-bond donor acidity and thus hopefully increase the rate and enantioselectivity of the catalysts [

28,

29,

30,

31].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

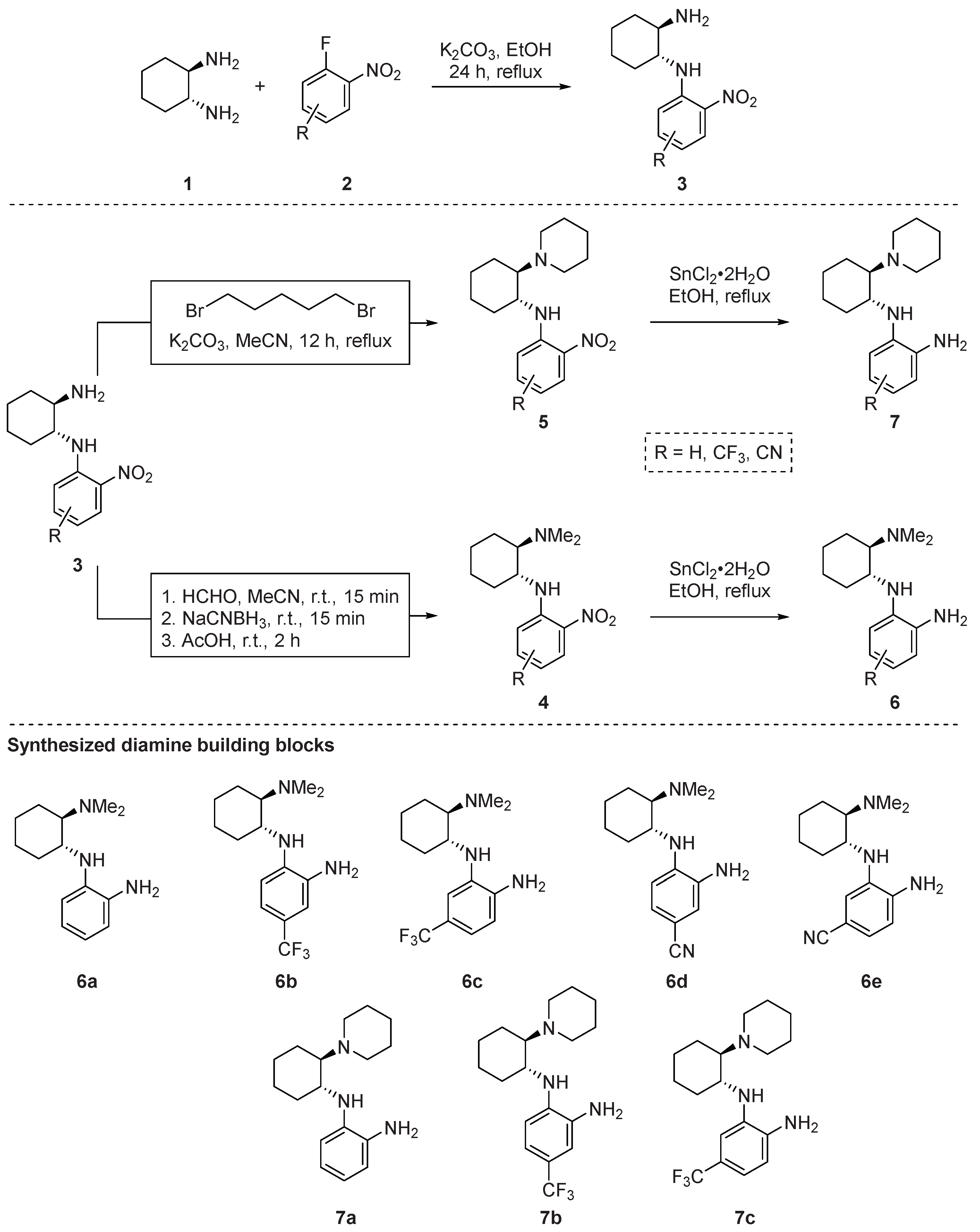

First, a reliable and as straightforward as possible synthesis of the chiral benzene-1,2-diamine building blocks

6 and

7, which contain a primary aromatic amino group and an aliphatic tertiary amino group, had to be established starting from inexpensive, commercially available (1

R,2

R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine and

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene derivatives (

Scheme 1). While the introduction of the benzene-1,2-diamine moiety was already developed on a chiral (

S)-quininamine scaffold [

27], the introduction of the aliphatic tertiary amino group had to be considered. Although the initial introduction of the tertiary amino group is well documented in the literature [

32,

33,

34,

35], this would potentially introduce unwanted additional protection/deprotection steps. Therefore, a nucleophilic aromatic substitution-alkylation-reduction sequence was preferred. First,

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene

2 was reacted with (1

R,2

R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine (

1) in the presence of a base to give nitrobenzene derivatives

3 in 45–72% yields. Only unsubstituted

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene (

2a) and

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene derivatives

2b–

e substituted with electron withdrawing groups (CF

3, CN) were considered. The electron-donating substituents have a detrimental effect on enantioselectivity and yield, as has already been shown [

27].Subsequently, the primary aliphatic amino group of

3 was selectively alkylated. To introduce the dimethylamino group for the preparation of compounds

4, reductive alkylation with aqueous formaldehyde using NaCNBH

3 in acetonitrile worked best (

4 prepared in 68–99% yields), since alkylation with iodomethane was accompanied by numerous side products. In contrast, the initially attempted reductive alkylation of

3 with glutaraldehyde in combination with NaCNBH

3 did not give a clean reaction profile; instead, the double nucleophilic S

N2 substitution with 1,5-dibromopentane in the presence of K

2CO

3 in acetonitrile worked best and gave the desired products

5 in 70–88% yields. Finally, the reduction of the aromatic nitro group of

4 and

5 was carried out with tin(II) chloride in ethanol, giving the desired benzene-1,2-diamines building blocks

6 and

7, respectively, in 71–98% yields. Surprisingly, all attempts to reduce the aromatic nitro group by catalytic hydrogenation with palladium on charcoal (also in the presence of acetic acid) led to complex product mixtures (

Scheme 1). The established three-step synthesis proved to be reproducible and scalable (up to 20 mmol). Compound

3a, prepared from diamine

1 and

ortho-fluoronitrobenzene (

2a), is the only compound described in the literature [

36].

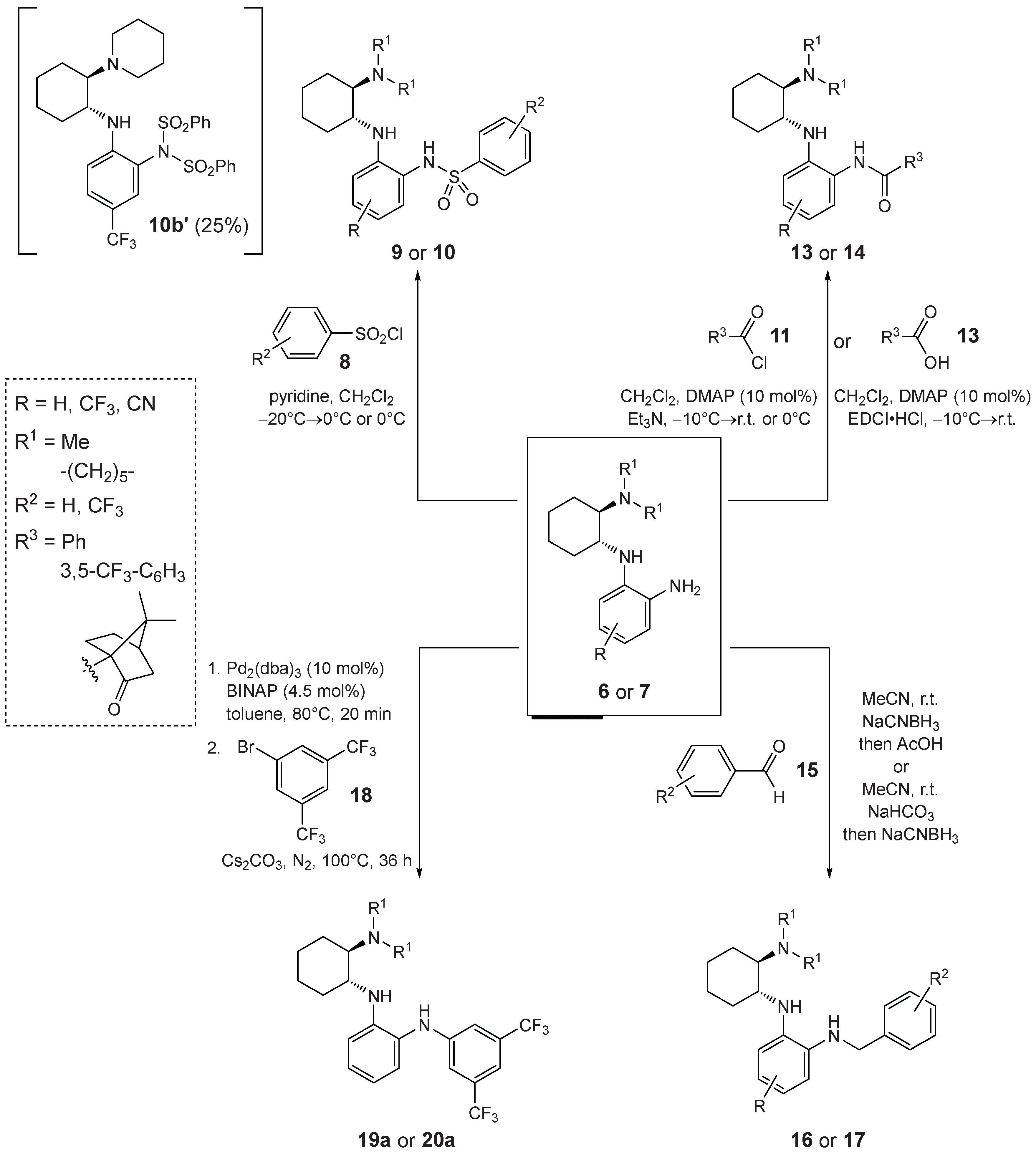

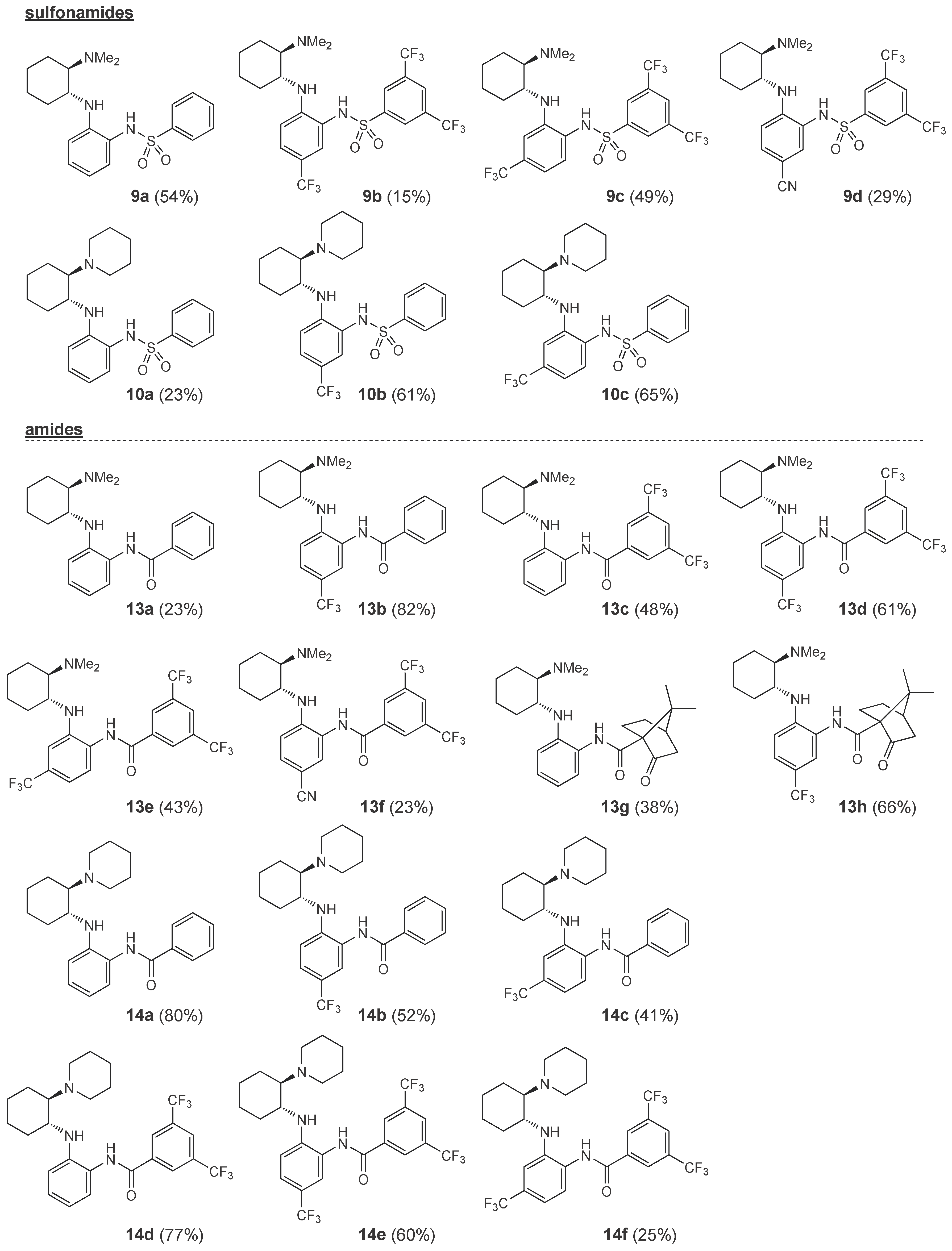

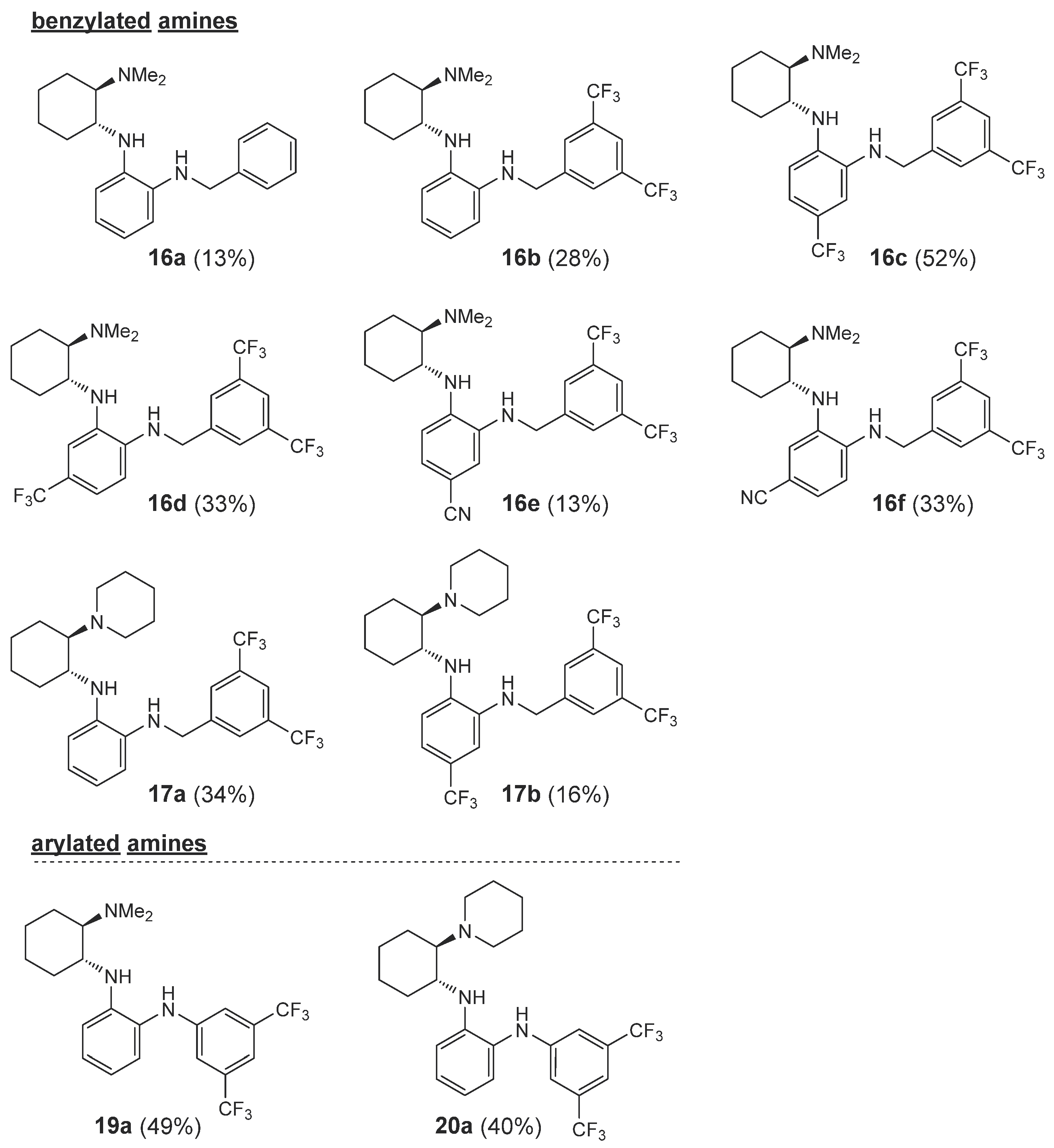

Starting from the chiral benzene-1,2-diamines

6 and

7, four subclasses of noncovalent bifunctional organocatalysts were prepared based on the type of functionalization of the aromatic primary amino group,

i.e. the formation of sulfonamides, amides, alkylated amines and arylated amines (

Scheme 2,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Sulfonamides

9 and

10 were prepared in 15–65% yield from amines

6 and

7, respectively, and benzenesulfonyl chloride (

8a) and 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzenesulfonyl chloride (

8b) in the presence of pyridine. The reactions of amines

7 were carried out at –20°C with a sub-stoichiometric amount of benzenesulfonyl chloride (

8a) (0.9 equiv.) to minimize the formation of double sulfonamides, such as compound

10b’ (isolated in 25% yield), which was formed as a by-product in the sulfonation of amine

7b. Amidations of amines

6 and

7 were carried out either with benzoyl chloride (

11) in the presence of DMAP and Et

3N or with EDCI-activated carboxylic acid (3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (

12a) and (1S)-(+)-ketopinic acid (

12b) were used) to amides

13 and

14, respectively, in 23–82% yields. The reductive benzylation of amines

6 and

7 was carried out with benzaldehyde (

15a) and 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde (

15b) using NaCNBH

3 as reducing agent in the presence of acetic acid or sodium hydrogencarbonate. The corresponding benzylated secondary amines

16 and

17 were formed in yields of 13–52%. Finally, the Buchwald-Hartwig arylation of amines

6 and 7 with 1-bromo-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene (

18) catalyzed by Pd was carried out using Pd

2(dba)

3 and BINAP in the presence of Cs

2CO

3 in anhydrous degassed toluene according to the literature procedure [

37]. Compounds

19a and

20a were isolated in 49% and 40% yield, respectively (

Scheme 2,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). All experimental data and procedures can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

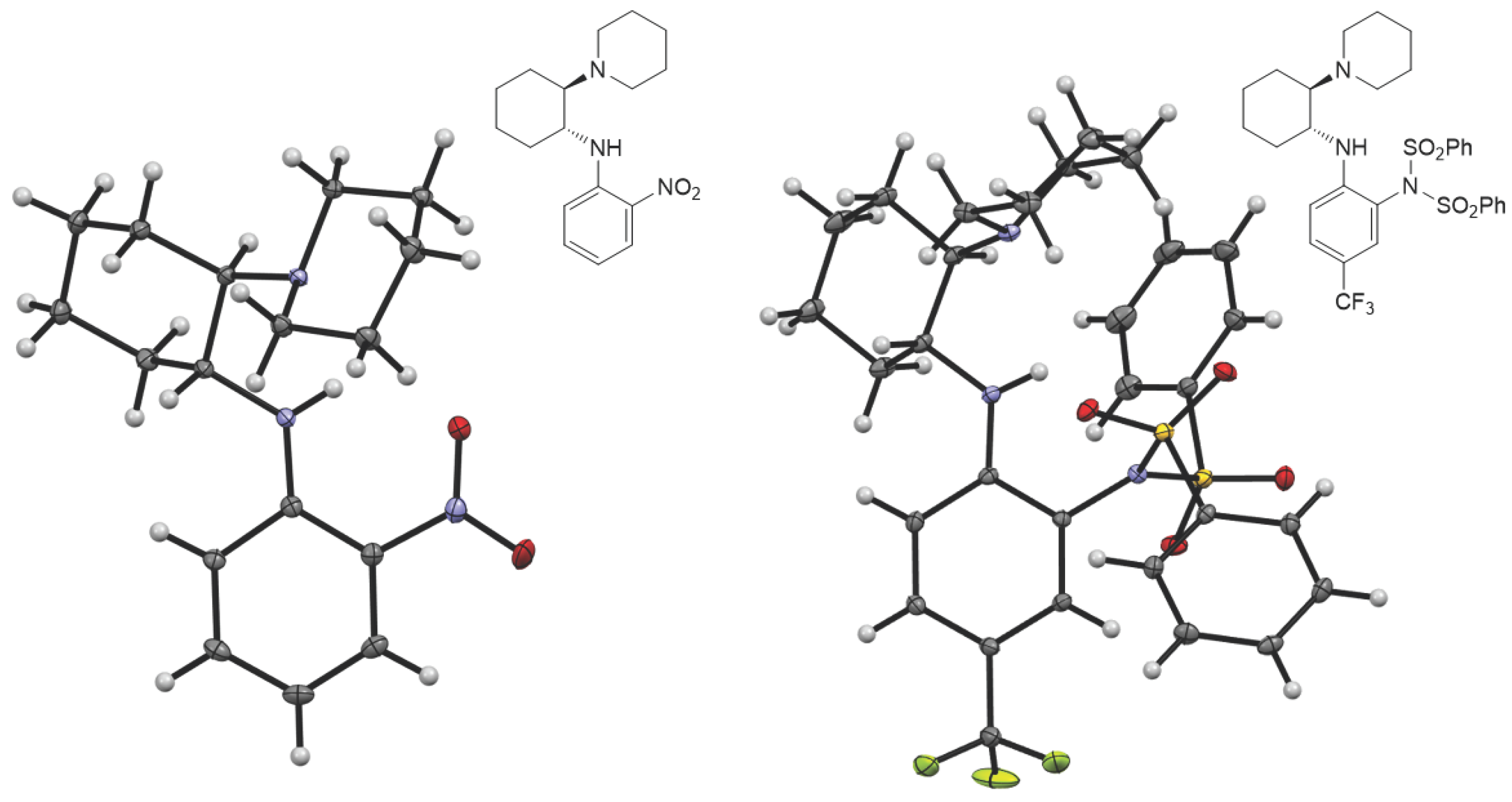

All new compounds

3b–

e,

4a–

e,

5a–

c,

6a–

e,

7a–

c,

9a–

d,

10a–

c,

10’b,

13a–

h,

14a–

f,

16a–

f,

17a,b,

19a, and

20a were characterized by spectroscopic methods (

1H- and

13C-NMR, 2D-NMR, HRMS and IR). The structures of compounds

5a and

10b’ were determined by X-ray single crystal analysis (

Figure 4).

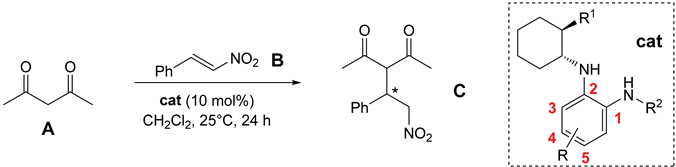

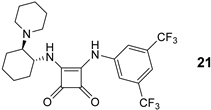

2.3. Organocatalytic Activity

The organocatalytic activity (conversion, enantioselectivity) of 1,2-benzenediamine-derived organocatalysts based on (1

R,2

R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine was investigated in the 1,4-addition of acetylacetone (

A) to

trans-β-nitrostyrene (

B) [

38,

39]. All reactions were carried out in anhydrous dichloromethane at 25°C for 24 hours with 10 mol% of the catalyst (

Table 1). Similar to the quinuclidine-derived analogues [

27], all the synthesized subtypes of organocatalysts were characterized by incomplete conversion (up to 93%) and low (

S)-enantioselectivity (up to 41%

ee). For comparison, the squaramide organocatalyst

21 [

40] yielded the addition product

C in 98% conversion and with high reversed enantioselectivity (93%

ee,

R) (

Table 1,

Entry 1). 9 of 32 catalysts (

9a,

10a,

13a–

e,

14d,

16a) achieved ≥80% conversion, with the highest conversion (93%) obtained with amide

14d (

Entry 21) and benzylamine

16a (

Entry 24), albeit with low enantioselectivity (≤13%

ee). 4 of 32 catalysts (

9b,

13d–

f) afforded the product

C with ≥30%

ee, with the highest enantioselectivity observed with catalyst

9b (41%

ee,

Entry 3) although the conversion was low (11%). The best catalysts in terms of both conversion and enantioselectivity were amides

13d (86% conversion, 32%

ee,

Entry 13) and

13e (83% conversion, 32%

ee,

Entry 14). The introduction of an electron-withdrawing substituent (R = CF

3, CN) on the benzene-1,2-diamine moiety in either position

4 or

5 generally resulted in lower conversion compared to the unsubstituted derivative (see and compare catalyst series

9a–

d,

10a–

c,

14a–

c,

14d–

f and

16a–

f), with the exception of amide series

13a–

e. The introduction of electron-withdrawing substituents (CF

3, CN) at any position in the catalyst,

i.e. 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl group, did not lead to a significant improvement in enantioselectivity; no clearly defined trends were observed. Both dimethylamino and piperidine containing catalysts show no convincing preference (conversion, enantioselectivity) for one of the two tertiary bases investigated. The double sulfonated catalyst

10b’ failed to give any addition product (

Entry 8), presumably due to steric reasons (see

Figure 4).

3. Materials and Methods

Solvents for extractions and chromatography were of technical grade and were distilled prior to use. Extracts were dried over technical grade anhydrous Na2SO4. Melting points were determined on a Kofler micro hot stage and on SRS OptiMelt MPA100 – Automated Melting Point System (Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, California, United States). The NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker UltraShield 500 plus (Bruker, Billerica, Massachusetts, United States) at 500 MHz for 1H and 126 MHz for 13C nucleus, using CDCl3 with TMS as the internal standard, as solvent. Mass spectra were recorded on an Agilent 6224 Accurate Mass TOF LC/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States), IR spectra on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum BX FTIR spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States). Column chromatography (CC) was performed on silica gel (Silica gel 60, particle size: 0.035-0.070 mm (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, United States)). HPLC analyses were performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity LC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States) using CHIRALPAK AD-H (0.46 cm ø × 25 cm) as chiral column (CHIRAL TECHNOLOGIES, INC., West Chester, Pennsylvania, United States). The EasyMax 102 Basic Thermostat system reactor (METTLER TOLEDO, Columbus, Ohio, United States) was used for reactions at low temperatures. All the commercially available chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, United States).

Synthesis of (1R,2R)-N1-(2-Nitrophenyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamines 3—General Procedure 1 (GP1)

To a solution of (1R,2R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine (1) (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous ethanol the corresponding 1-fluoro-2-nitrobenzene 2 (1.0 equiv.) and K2CO3 (1.1 equiv.) were added. The resulting mixture was refluxed for 24 hours. The volatiles were evaporated in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in EtOAc (1.5 mL/1 mmol) and washed with water (0.5 mL/1 mmol). The aqueous phase was extracted twice more with EtOAc (0.5 mL/1 mmol). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60, 1. EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:1; 2. CH2Cl2/MeOH = 10:1). The fractions containing the pure product 3 were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Synthesis of (1R,2R)-N1,N1-Dimethyl-N2-(2-nitrophenyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamines 4—General Procedure 2 (GP2)

Formaldehyde (aqueous, 37%, 5.0 equiv.) was added to the corresponding (1R,2R)-N1-(2-nitrophenyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine 3 (1.0 equiv.) dissolved in acetonitrile at room temperature. After stirring for 15 minutes at room temperature, NaCNBH3 (2.0 equiv.) was added. After 15 minutes of stirring at room temperature, acetic acid (4.5 equiv.) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 2 hours, a solution of 2% MeOH in CH2Cl2 (14 mL/1 mmol) was added and the mixture was washed three times with NaOH (aqueous, 1 M, 14 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60, 1. EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:1). The fractions containing the pure product 4 were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Synthesis of 2-Nitro-N-((1R,2R)-2-(piperidin-1-yl)cyclohexyl)aniline 5—General Procedure 3 (GP3)

To a solution of the corresponding (1R,2R)-N1-(2-nitrophenyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine 3 (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous acetonitrile under argon were added 1,5-dibromopentane (1.1 equiv.) and K2CO3 (2.2 equiv.). The resulting reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 12 hours. The volatiles were evaporated in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (6 mL/1 mmol) and washed with water (4 mL/1 mmol). The aqueous phase was additionally extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 mL/1 mmol). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60, EtOAc/petroleum ether = 5:1). The fractions containing the pure product 5 were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. The residue was additionally purified by short-path vacuum distillation (120°C, 2 mbar, several hours) to remove the unreacted 1,5-dibromopentane.

Reduction of the Aromatic Nitro Group—General Procedure 4 (GP4)

To a solution of the corresponding (2-nitrophenyl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine 4 or 5 (1.0 equiv.) in ethanol was added SnCl2•2H2O (6 equiv.). The resulting reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and then NaOH (aq., 6 M) was added until a homogeneous solution was obtained (pH = 14). CH2Cl2 (6 mL/1 mmol) was then added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes. The phases were then separated and the organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. If necessary, the resulting product 6 or 7 was additionally purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 6 or 7, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Synthesis of Benzenesulfonamides 9 and 10—General Procedure 5 (GP5)

To a solution of benzene-1,2-diamine 6 or 7 (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane, pyridine (1.1 equiv.) (and optionally DMAP (10 mol%)) were added under argon. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C or –20°C and then benzenesulfonyl chloride 8 was added. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at 0°C for 2 hours. In the case where the reaction mixture was cooled to –20°C, the resulting reaction mixture was gradually warmed from –20°C to 0°C within 4 hours with constant stirring. Then, ethyl acetate (14 mL/1 mmol) was added. The resulting mixture was washed with NaHCO3 (aq. sat., 7 mL/1 mmol) and NaCl (aq. sat., 7 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 9 or 10, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Acylation of the Primary Amine with Benzoyl Chloride—General Procedure 6 (GP6)

To a solution of benzene-1,2-diamine 6 or 7 (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane, Et3N (1.2 equiv.) and DMAP (10 mol%) were added under argon. The reaction mixture was cooled to –10°C or 0°C and then benzoyl chloride (11) (1.2 equiv.) was added. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature or 0°C for 2 hours. Then, ethyl acetate (14 mL/1 mmol) was added. The resulting mixture was washed with NaHCO3 (aq. sat., 7 mL/1 mmol) and NaCl (aq. sat., 7 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 13 or 14, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Acylation of the Primary Amine with EDCI Activated Carboxylic Acid—General Procedure 7 (GP7)

To a solution of benzene-1,2-diamine 6 or 7 (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane, carboxylic acid 12 (1.0 equiv.) and DMAP (10 mol%) were added under argon. The reaction mixture was cooled to –10°C and then EDCI•HCl (1.2 equiv.) was added. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. Then, CH2Cl2 (35 mL/1 mmol) was added. The resulting mixture was washed with H2O (7 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 13 or 14, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Reductive Alkylation of the of Primary Amine—General Procedure 8 (GP8)

To a solution of N1-((1R,2R)-2-(dimethylamino)cyclohexyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (6a) (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous acetonitrile at room temperature, aldehyde 15 (2.0 equiv.) and NaCNBH3 (2.0 equiv.) were added. After stirring for 15 minutes at room temperature, AcOH was added to the reaction mixture. After stirring for 2 hours at room temperature, a 2% solution of MeOH in CH2Cl2 (22 mL/1 mmol) was added. The resulting mixture was washed three times with NaOH (aq., 1 M, 22 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 16 were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Reductive Alkylation of the of Primary Amine—General Procedure 9 (GP9)

Aldehyde 15 (1.0 equiv.) and NaHCO3 (2.0 equiv.) were added to a solution of benzene-1,2-diamine 6 or 7 (1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous acetonitrile at room temperature. After stirring at room temperature for 15 minutes, NaCNBH3 (4.0–6.0 equiv.) was added to the reaction mixture in portions (1.0–1.5 equiv. per hour). After stirring at room temperature for 4 hours, HCl (aq., 2 M) was added to pH 1, followed by the addition of NaOH (aq., 2 M) to pH = 12. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (14 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 16 or 17, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Arylation of the Primary Amine—General Procedure 10 (GP10)

An AC heavy wall reaction tube was charged with Pd2(dba)3 (1.5 mol%) and BINAP (4.5 mol%) in anhydrous degassed toluene under argon. The mixture was heated at 80°C under argon for 20 minutes. The resulting red mixture, cooled to room temperature, was then transferred to a separate heavy-walled AC reaction tube that had previously been charged with Cs2CO3 (1.53 equiv.) and 1-bromo-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene (18) (1 equiv.) in anhydrous degassed toluene under argon. Finally, benzene-1,2-diamine 6 or 7 (1.0 equiv.) was added and the sealed reaction mixture was heated at 100°C for 36 hours. Then, H2O (20 mL/1 mmol) was added to the cooled reaction mixture (room temperature) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (60 mL/1 mmol). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the volatiles evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60). The fractions containing the pure product 12 or 13, respectively, were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo.

Organocatalyzed Addition of Acetylacetone to trans-β-Nitrostyrene

To a solution of trans-β-nitrostyrene (B) (29.8 mg, 0.2 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (1 mL) under argon, catalyst (10 mol%) was added, followed by the addition of acetylacetone (C) (30.8 μL, 0.3 mmol). The resulting reaction mixture under argon was stirred at 25°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, an aliquot of 100 μL of the reaction mixture was withdrawn to determine the reaction conversion by 1H NMR (in CDCl3). The remainder of the reaction mixture was used to isolate the addition product C. The residue was purified by column chromatography (Silica gel 60, EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:1 – in the case of non-polar catalysts EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:3 was used, ). The reaction mixture was transferred directly to the top of the column without prior evaporation of the volatile components. The fractions containing product C were combined and the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. Enantioselectivity was determined by chiral HPLC analysis (chiral column CHIRALPAK AD-H, mobile phase: n-hexane/i-PrOH = 90:10, flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; λ = 210 nm).

X-ray Crystallography

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data was collected on Agilent Technologies SuperNova Dual diffractometer with an Atlas detector using monochromated Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) at 150 K. The data was processed using CrysAlis PRO [

41]. Using Olex2.1.2. [

42], the structures were solved by direct methods implemented in SHELXS [

43] or SHELXT [

44] and refined by a full-matrix least-squares procedure based on F2 with SHELXT-2014/7 [

45]. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropicallly. Hydrogen atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions and were refined using a riding model. The drawings and the analysis of bond lengths, angles and intermolecular interactions were carried out using Mercury [

46] and Platon [

47]. Structural and other crystallographic details on data collection and refinement for compounds

5a and

10b’ have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary publication number CCDC Deposition Numbers 2330833 and 2330834, respectively. These data are available free of charge at

https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/, accessed on 04 February 2024 (or from CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

4. Conclusions

The chiral benzene-1,2-diamine building blocks 6 and 7, containing a primary aromatic amino group and an aliphatic tertiary amino group, were prepared from commercially available (1R,2R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine (1) and ortho-fluoronitrobenzene derivatives 2 in a three-step synthesis involving a nucleophilic aromatic substitution-alkylation-reduction sequence. Subsequent functionalization of the primary aromatic amino group of 6 and 7 led to four subclasses of noncovalent organocatalysts, namely sulfonamides 9/10, amides 13/14, alkylated amines 16/17 and arylated amines 19/20. All new compounds were fully characterized. The organocatalytic activity (conversion, enantioselectivity) of 1,2-benzenediamine-derived organocatalysts based on (1R,2R)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine was investigated in the 1,4-addition of acetylacetone to trans-β-nitrostyrene in anhydrous dichloromethane at 25°C for 24 h with 10 mol% of the catalyst. All synthesized subtypes of organocatalysts were characterized by incomplete conversion (up to 93%) and low (S)-enantioselectivity (up to 41% ee). The alkylated amines 16/17 and the arylated amines 19/20 have the potential to be converted into benzimidazole N-heterocyclic carbene precursors in one step.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org: Syntheses and characterization; HPLC data, Copies of 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra; Copies of HRMS reports; Structure determination using X-ray diffraction analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K., A.G., L.C., U.G., J.S. and B.Š.; methodology, K.K., A.G., L.C. and U.G.; software, K.K., A.G., L.C., H.B., U.G., J.S. and B.Š.; validation, K.K., A.G., L.C., H.B., U.G., J.S., F.P. and B.Š.; formal analysis, K.K., A.G., U.G., H.B. and L.C.; investigation, K.K., A.G., L.C. and U.G.; resources, L.C., U.G. and J.S.; data curation, K.K., A.G., L.C., H.B., U.G., J.S. and B.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, U.G., J.S. and B.Š.; writing—review and editing, L.C., U.G., J.S., F.P. and B.Š.; visualization, L.C., H.B., U.G., B.Š. and J.S.; supervision, U.G.; project administration, U.G. and J.S.; funding acquisition, U.G. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency through grant P1-0179.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the EN-FIST Centre of Excellence, Dunajska 156, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia, for the use of their BX FTIR spectrophotometer and Agilent 1260 Infinity LC for HPLC analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Okino, T.; Hoashi, Y.; Takemoto, Y. Enantioselective Michael Reaction of Malonates to Nitroolefins Catalyzed by Bifunctional Organocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12672–12673. [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.; Jin, Y. Organocatalytic Enantioselective Michael Reaction of Aminomaleimides with Nitroolefins Catalyzed by Takemoto’s Catalyst. Molecules 2022, 27, 7787. [CrossRef]

- Malerich, J.P.; Hagihara, K.; Rawal, V.H. Chiral Squaramide Derivatives are Excellent Hydrogen Bond Donor Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14416–14417. [CrossRef]

- Rombola, M.; Sumaria, C.S.; Montgomery, T.D.; Rawal, V.H. Development of Chiral, Bifunctional Thiosquaramides: Enantioselective Michael Additions of Barbituric Acids to Nitroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5297–5300. [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.R. (Ed.) Stereoselective Organocatalysis: Bond Formation Methodologies and Activation Modes, 1st ed.; JohnWiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013.

- a) List, B. Asymmetric Organocatalysis 1. Lewis Base and Acid Catalysis. In Science of Synthesis, vol. ed., Georg Thieme Verlag KG: Germany, 2012. b) Maruoka, K. Asymmetric Organocatalysis 2. Brønsted Base and Acid Catalysis. In Science of Synthesis, vol. ed., Georg Thieme Verlag KG: Germany, 2012.

- Dalko, P.I. Comprehensive Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Catalysts, Reactions, and Applications, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2013.

- Etzenbach-Effers, K.; Berkessel, A. Noncovalent Organocatalysis Based on Hydrogen Bonding: Elucidation of Reaction Paths by Computational Methods. In: List, B. (eds) Asymmetric Organocatalysis. Topics in Current Chemistry, vol. 291. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.M.F.; Prechtl, M.H.G.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Non-Covalent Interactions in Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Theoretical and Mechanistic Studies of Reactions Mediated by Dual H-Bond Donors, Bifunctional Squaramides, Thioureas and Related Catalysts. Catalysts 2021, 11, 569. [CrossRef]

- Kótai, B.; Kardos, G.; Hamza, A.; Farkas, V.; Pápai, I; Soós, T. On the Mechanism of Bifunctional Squaramide-Catalyzed Organocatalytic Michael Addition: A Protonated Catalyst as an Oxyanion Hole. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 5631–5639. [CrossRef]

- Cassani, C.; Martín-Rapún, R.; Arceo, E.; Bravo, F.; Melchiorre, P. Synthesis of 9-amino(9-deoxy)epi cinchona alkaloids, general chiral organocatalysts for the stereoselective functionalization of carbonyl compounds. Nature Protocols, 2013, 8, 325–344. https://doi.org.10.1038/nprot.2012.155.

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Deng, L. Cinchona Alkaloids. In Privileged Chiral Ligands and Catalysts, Q.-L. Zhou (Ed.), 2011. [CrossRef]

- Cinchona Alkaloids in Synthesis and Catalysis: Ligands, Immobilization and Organocatalysis. Ed. Choong E.S. VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kopyt, M.; Głowacki, M.P.; Kwiatkowski, P. trans-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane and Its Derivatives in Asymmetric Organocatalysis. In Chiral Building Blocks in Asymmetric Synthesis (eds Wojaczyńska E.; Wojaczyński J.), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hirashima, S.-I.; Arai, R.; Nakashima, K.; Kawai, N.; Kondo, J.; Koseki, Y.; Miura, T. Asymmetric Hydrophosphonylation of Aldehydes using a Cinchona–Diaminomethylenemalononitrile Organocatalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 3863–3867. [CrossRef]

- Arai, R.; Hirashima, S.-i.; Kondo, J.; Nakashima, K.; Koseki, V.; Miura, T. Cinchona–Diaminomethylenemalononitrile Organocatalyst for the Highly Enantioselective Hydrophosphonylation of Ketones and Enones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5569–5572. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Hayama, N.; Inokuma, T.; Takemoto, Y. A Powerful Hydrogen-Bond-Donating Organocatalyst for the Enantioselective Intramolecular Oxa-Michael Reaction of α,β-Unsaturated Amides and Esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11114–11118. [CrossRef]

- Maddox, S.M.; Dawson, G.A.; Rochester, N.C.; Ayonon, A.B.; Moore, C.E.; Rheingold, A.L.; Gustafson, J.L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Biaryl Atropisomers via the Addition of Thiophenols into Aryl-Naphthoquinones. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5443–5447. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, J.; Lu Y. Highly Enantioselective Michael Addition of 2-Fluoro-1,3-diketones to Nitroalkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 320–324. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Zhou, F.; Liu, Y.-L; Wang, C.-H.; Zhao, X.-L.; Zhou, J. Cinchona alkaloid-based phosphoramide catalyzed highly enantioselective Michael addition of unprotected 3-substituted oxindoles to nitroolefins. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 2035–2039. [CrossRef]

- Žabka, M.; Šebesta, R. Experimental and Theoretical Studies in Hydrogen-Bonding Organocatalysis. Molecules 2015, 20, 15500-15524. [CrossRef]

- Vera, S.; García-Urricelqui, A.; Mielgo, A.; Oiarbide, M. Progress in (Thio)urea- and Squaramide-Based Brønsted Base Catalysts with Multiple H-Bond Donors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202201254. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Chai, Z.; Zhao, G. Novel bifunctional thiourea–ammonium salt catalysts derived from amino acids: Application to highly enantio-and diastereoselective aza-Henry reaction. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 5104–5111. [CrossRef]

- Novacek, J.; Waser, M. Syntheses and Applications of (Thio) Urea-Containing Chiral Quaternary Ammonium Salt Catalysts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014, 802–809. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Chiral Phase-Transfer Catalysts with Hydrogen Bond: A Powerful Tool in the Asymmetric Synthesis. Catalysts 2019, 9, 244. [CrossRef]

- Waser, M.; Winter, M.; Mairhofer, C. (Thio)urea containing chiral ammonium salt catalysts. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200198. [CrossRef]

- Ciber, L.; Požgan, F.; Brodnik, H.; Štefane, B.; Svete, J.; Grošelj, U. Synthesis and Catalytic Activity of Organocatalysts Based on Enaminone and Benzenediamine Hydrogen Bond Donors. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1132. [CrossRef]

- Gilli, P.; Pretto, L.; Bertolasi, V.; Gilli, G. Predicting Hydrogen-Bond Strengths from Acid−Base Molecular Properties. The pKa Slide Rule: Toward the Solution of a Long-Lasting Problem. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Jakab, G.; Tancon, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lippert, K.M.; Schreiner, P.R. (Thio)urea Organocatalyst Equilibrium Acidities in DMSO. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1724–1727. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, J.-P. Equilibrium acidities of cinchona alkaloid organocatalysts bearing 6′-hydrogen bonding donors in DMSO. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 170–176. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.-P. Squaramide Equilibrium Acidities in DMSO. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 1786–1789. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Sadeh, E.; Ahmadi, S. Exploration of tertiary aminosquaramide bifunctional organocatalyst in controlled/living ring-opening polymerization of l-lactide. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 2483–2493. [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Xiong, W.; Li, D.-Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, J.-B. Bifunctional thiourea-based organocatalyst promoted kinetic resolution polymerization of racemic lactide to isotactic polylactide. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 12731–12734. [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, N.R.; Turner, P.; Todd, M.H. The First Catalytic, Enantioselective Aza-Henry Reaction of an Unactivated Cyclic Imine. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 2954–2958. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.M.; Finney, N. S. An efficient method for the preparation of N,N-disubstituted 1,2-diamines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 8431–8434. [CrossRef]

- Boratyński, P.J.; Nowak, A.E.; Skarżewski, J. New Chiral Benzimidazoles Derived from 1,2-Diaminocyclohexane. Synthesis 2015, 47, 3797–3804. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Lewis, A.J.; Williams, U.J.; Carroll, P.J.; Schelter, E.J. Fluorinated diarylamide complexes of uranium(iii, iv) incorporating ancillary fluorine-to-uranium dative interactions. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 798–805. [CrossRef]

- Ričko, S.; Svete, J.; Štefane, B.; Perdih, A.; Golobič, A.; Meden, A.; Grošelj, U. 1,3-Diamine-Derived Bifunctional Organocatalyst Prepared from Camphor. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 3786–3796. [CrossRef]

- Okino, T; Hoashi, Y; Furukawa, F; Xu, X; Takemoto,Y. Enantio- and Diastereoselective Michael Reaction of 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds to Nitroolefins Catalyzed by a Bifunctional Thiourea. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Du, D.-M. Chiral Squaramide-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Michael Addition of 2-Hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinones to Nitroalkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1241–1246. [CrossRef]

- CrysAlis PRO; Agilent Technologies UK Ltd.: Yarnton, UK, 2011.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cristallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT-Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Shields, G.P.; Taylor, R.; Towler, M.; van de Streek, J. Mercury: visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 453–457. [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).