Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of the Polyurethanes (PUs)

2.2.2. Experimental Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

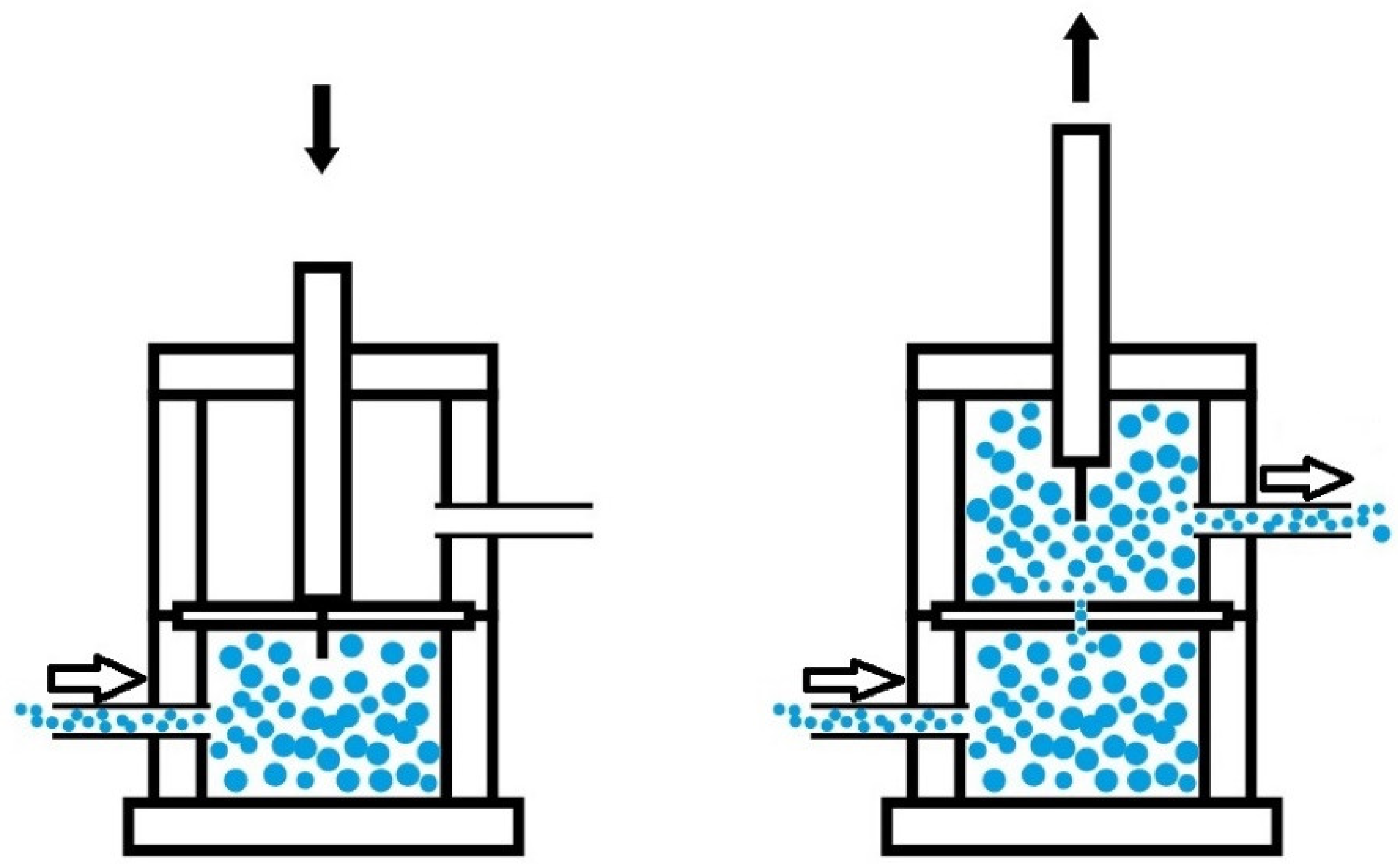

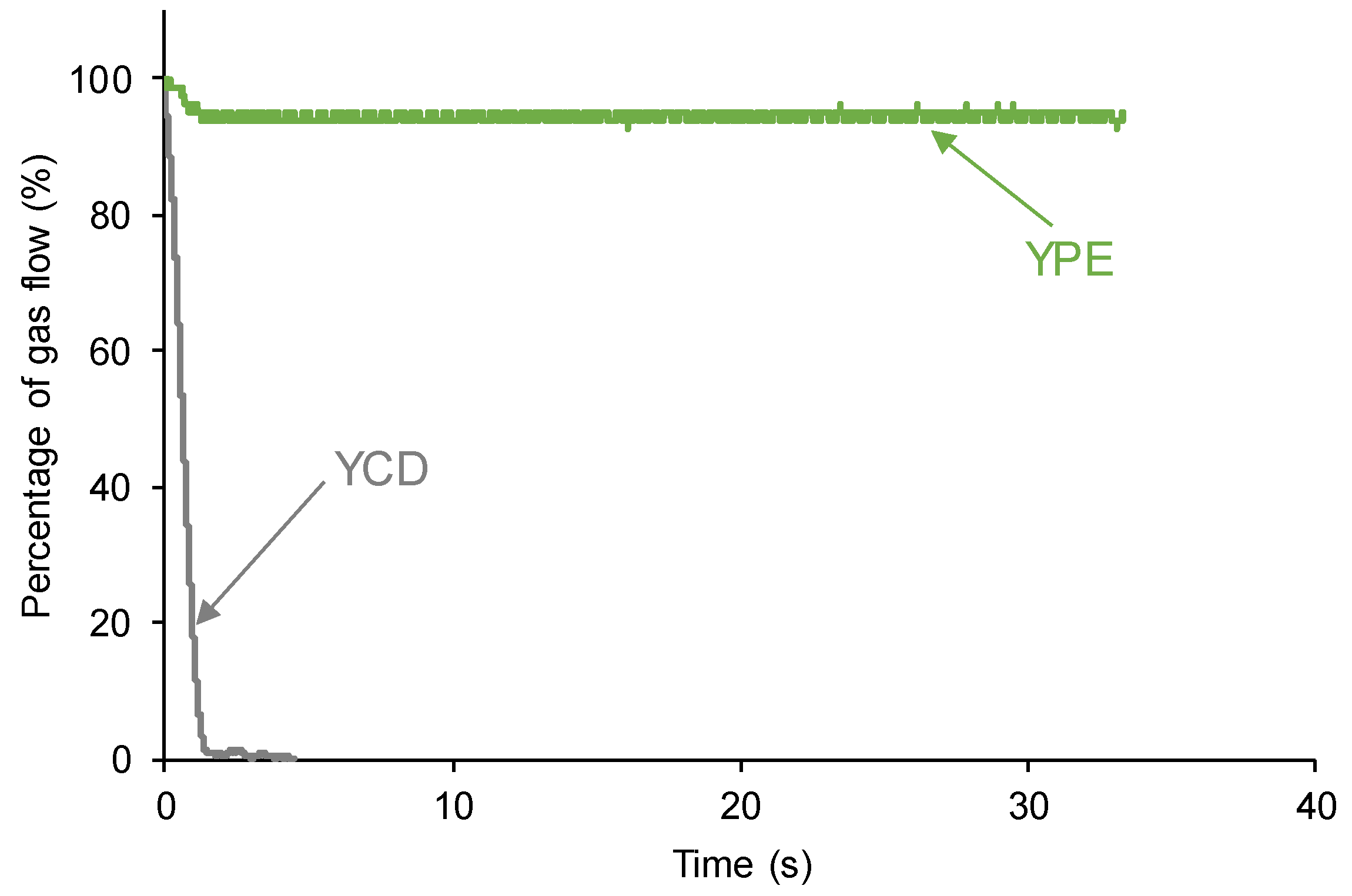

3.1. Assessment of the Self-Healing at 20 °C of the PUs

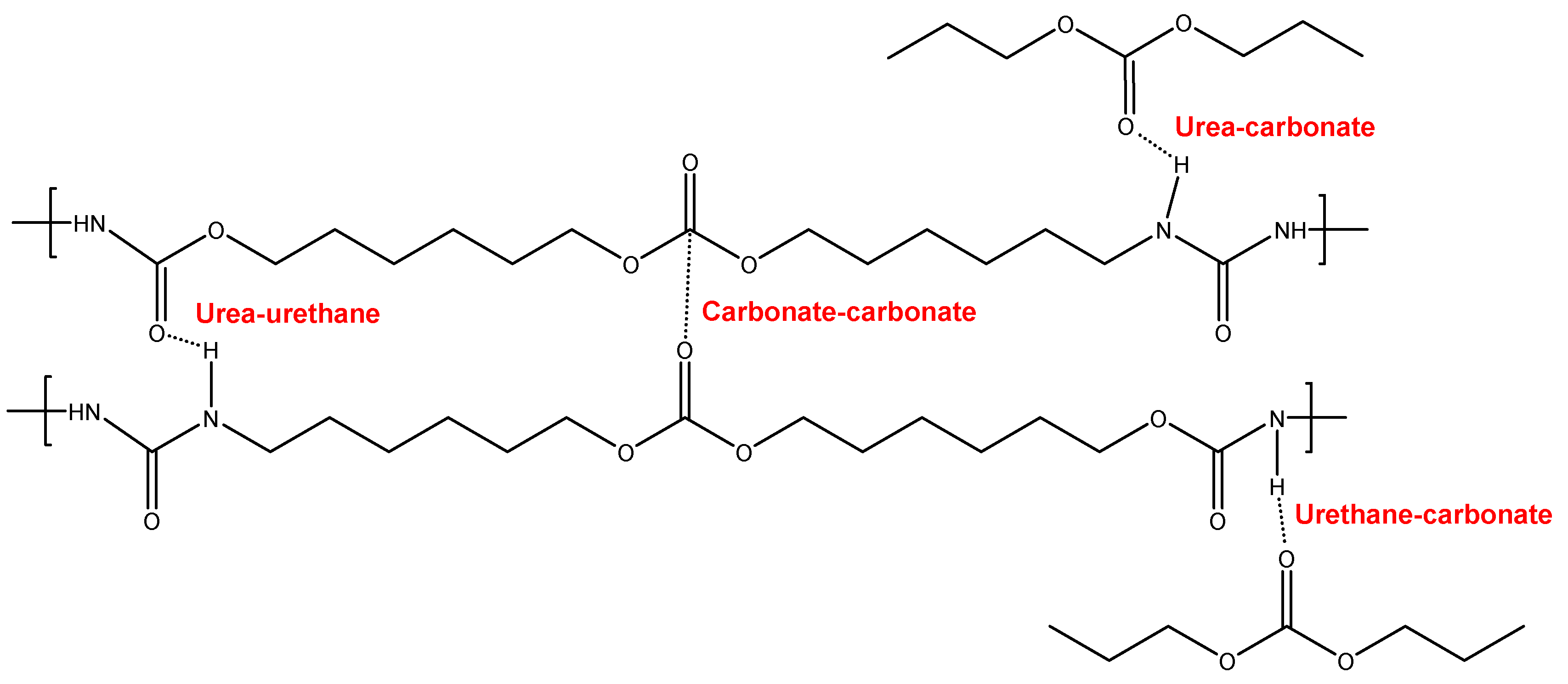

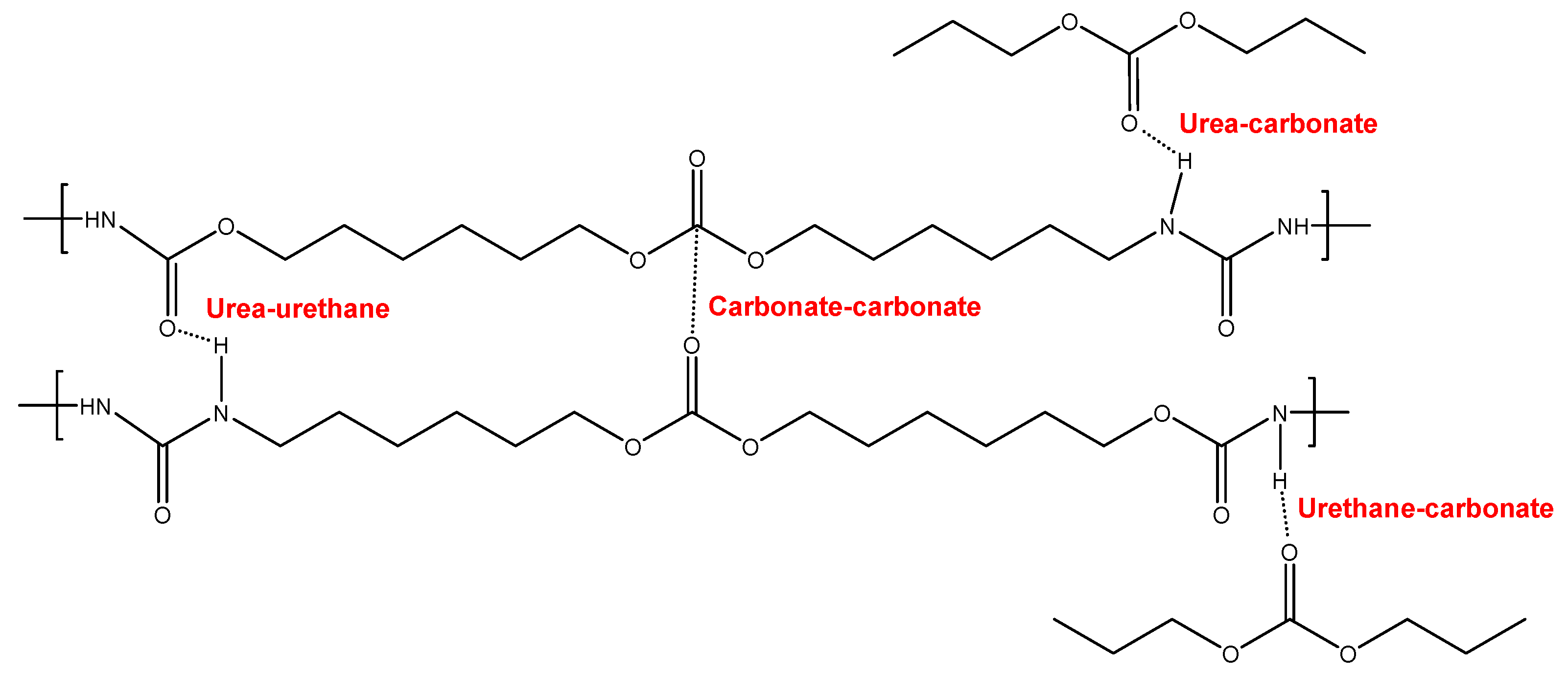

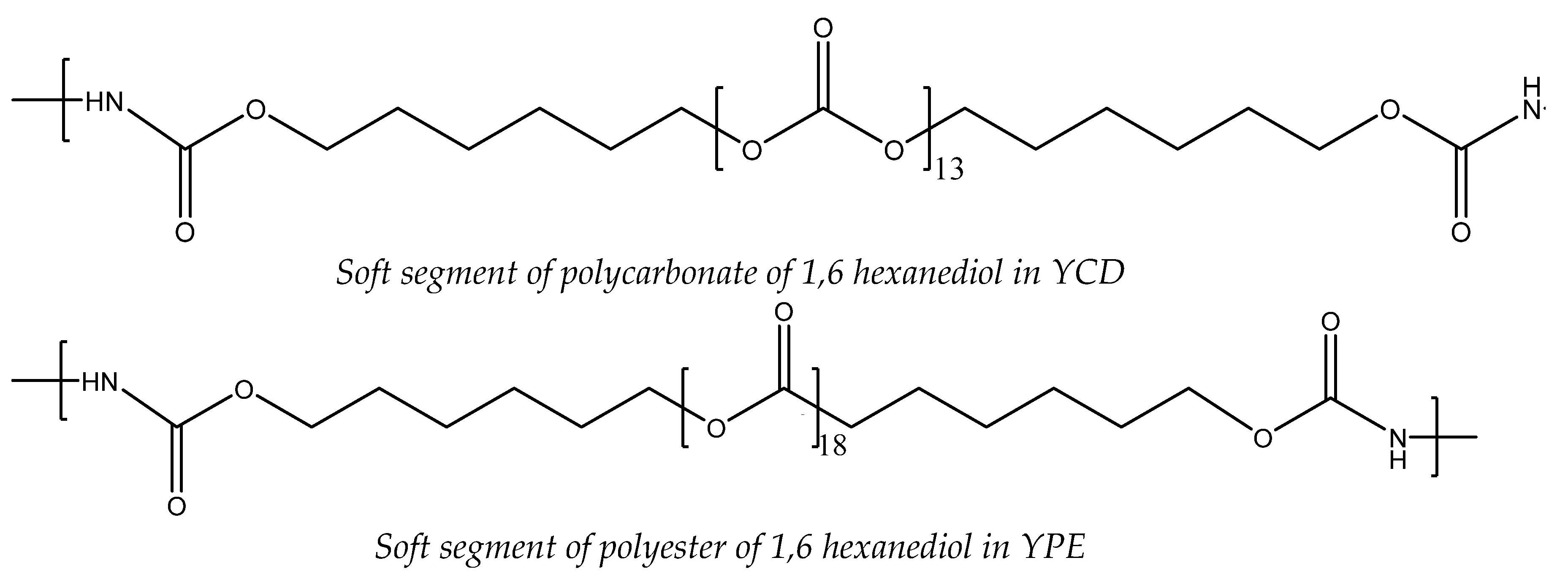

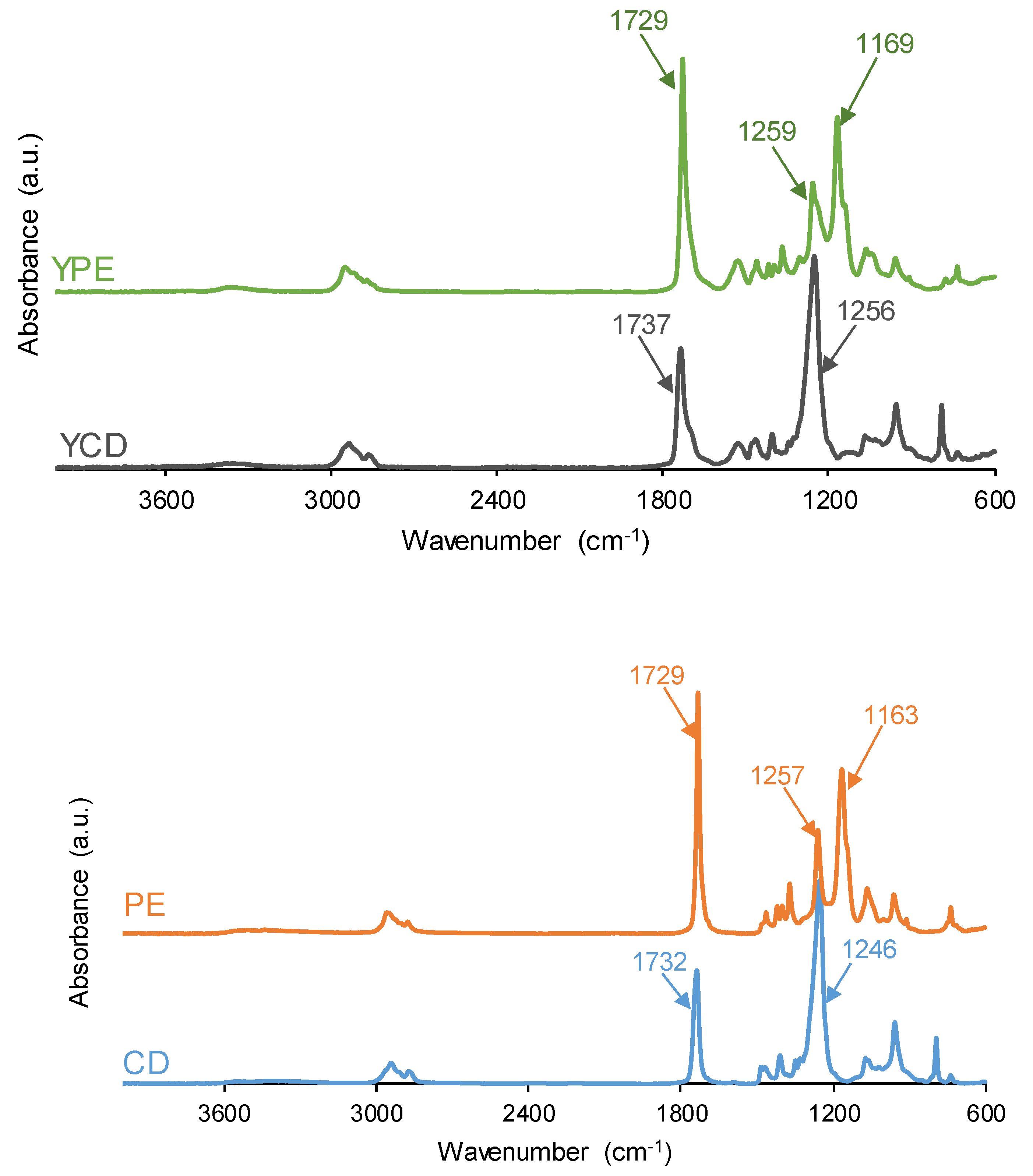

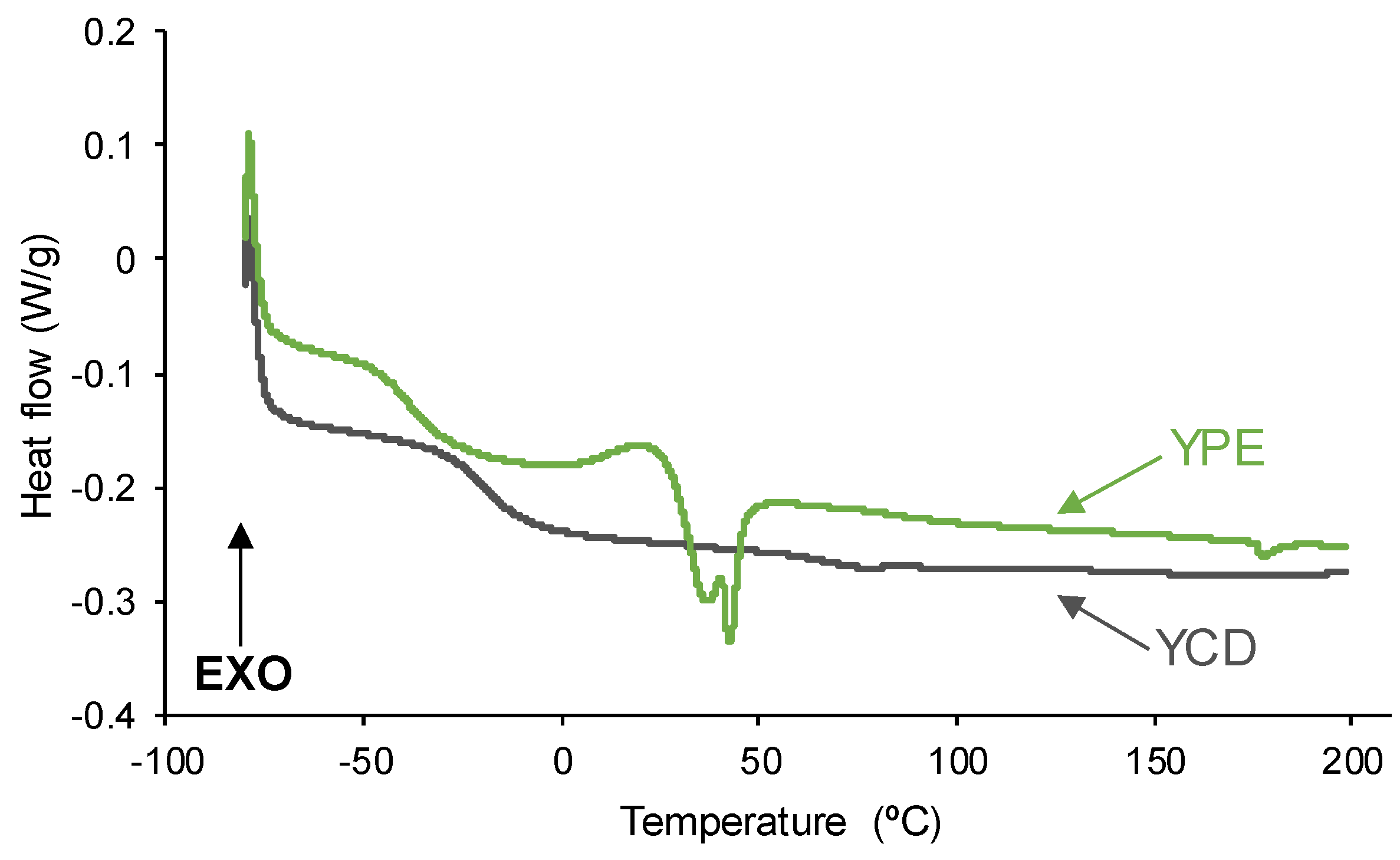

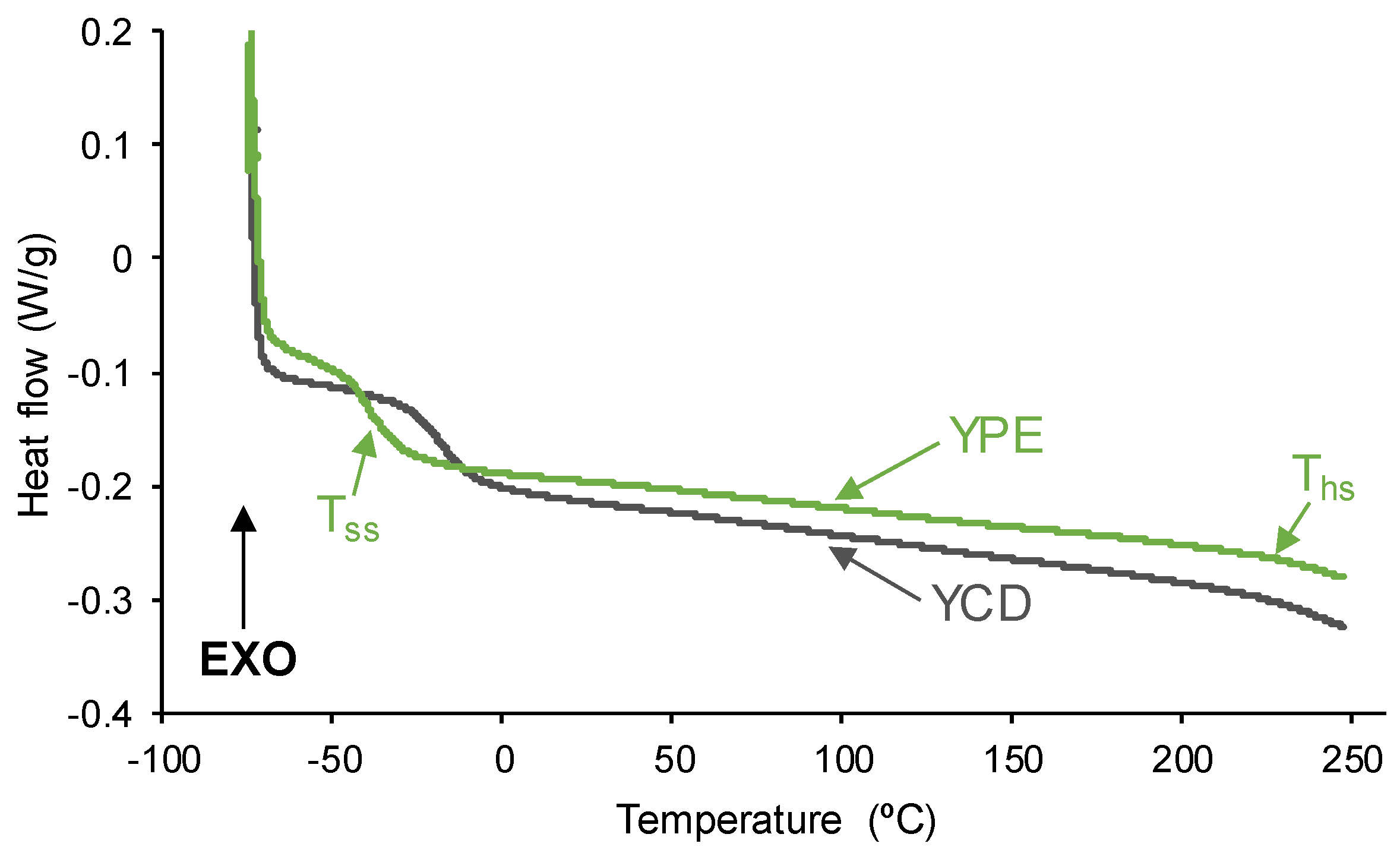

3.2. Structural Characterization of the PUs

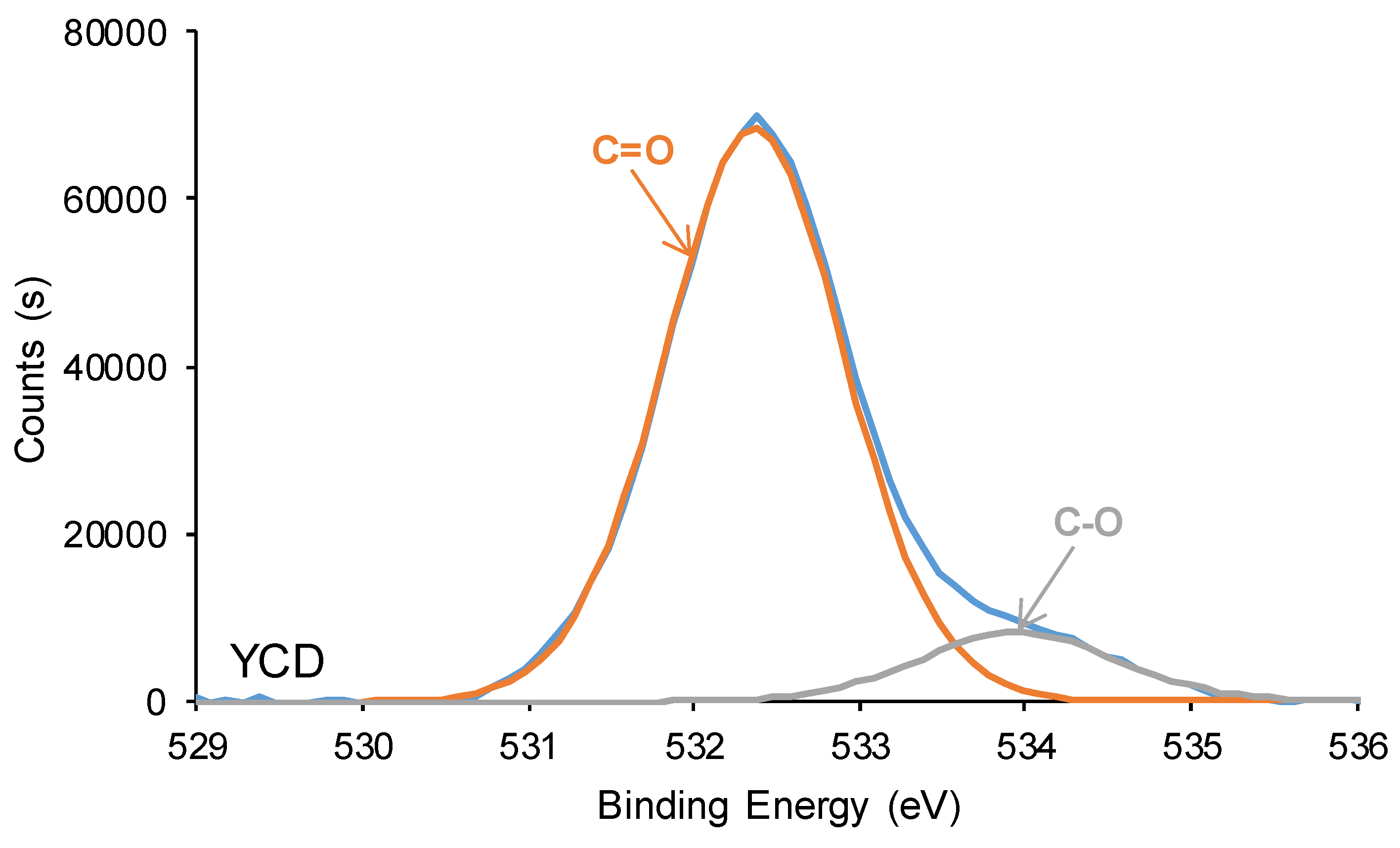

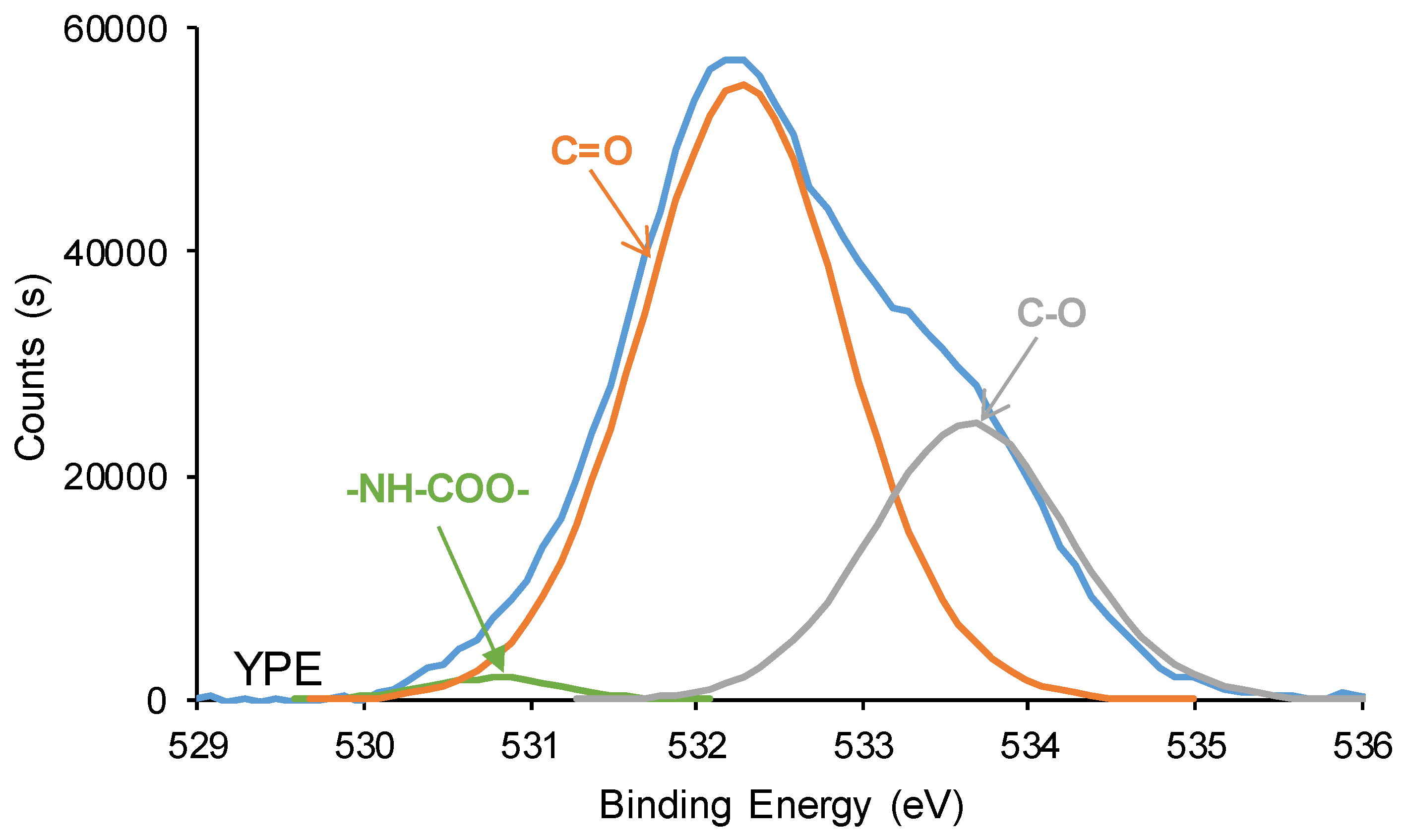

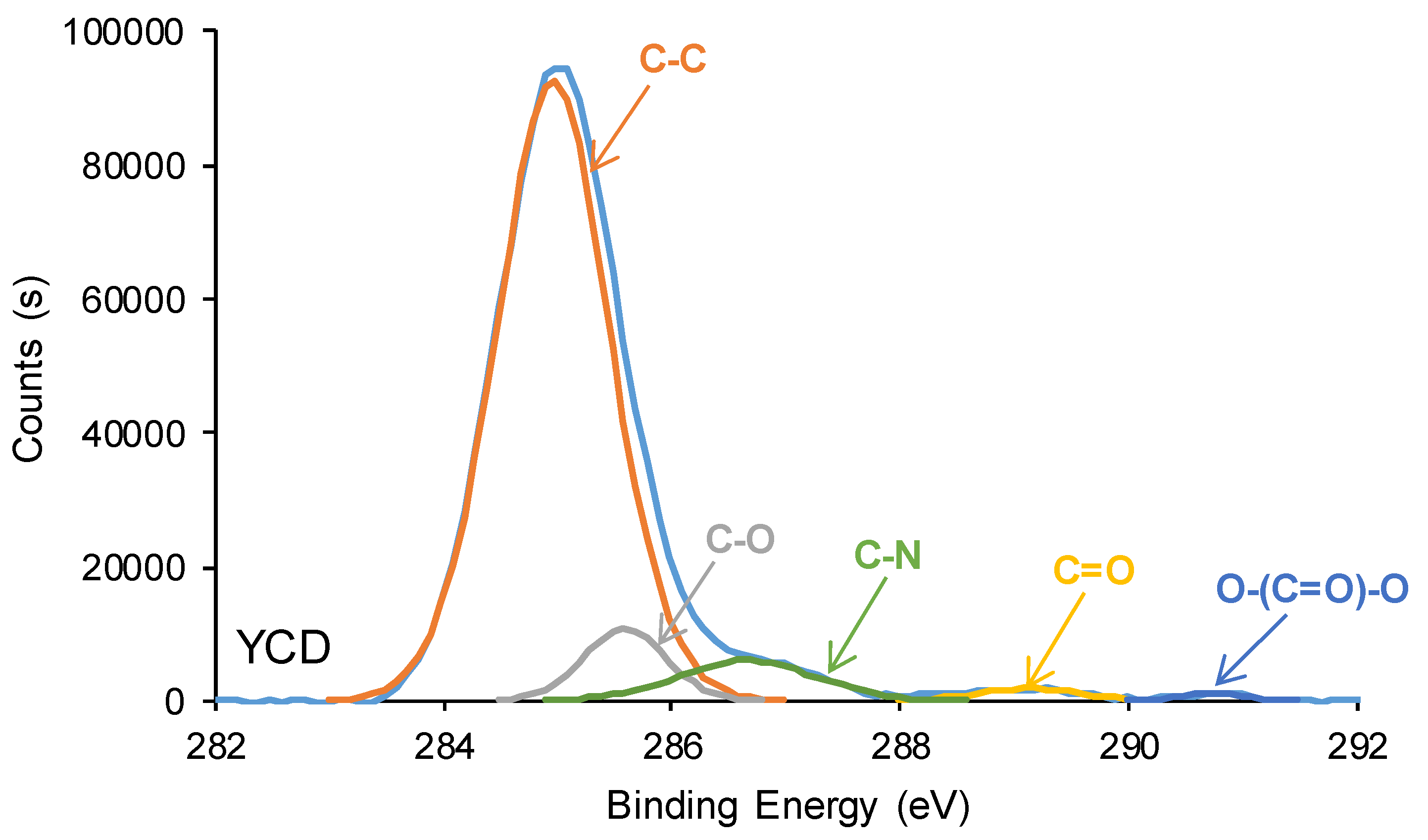

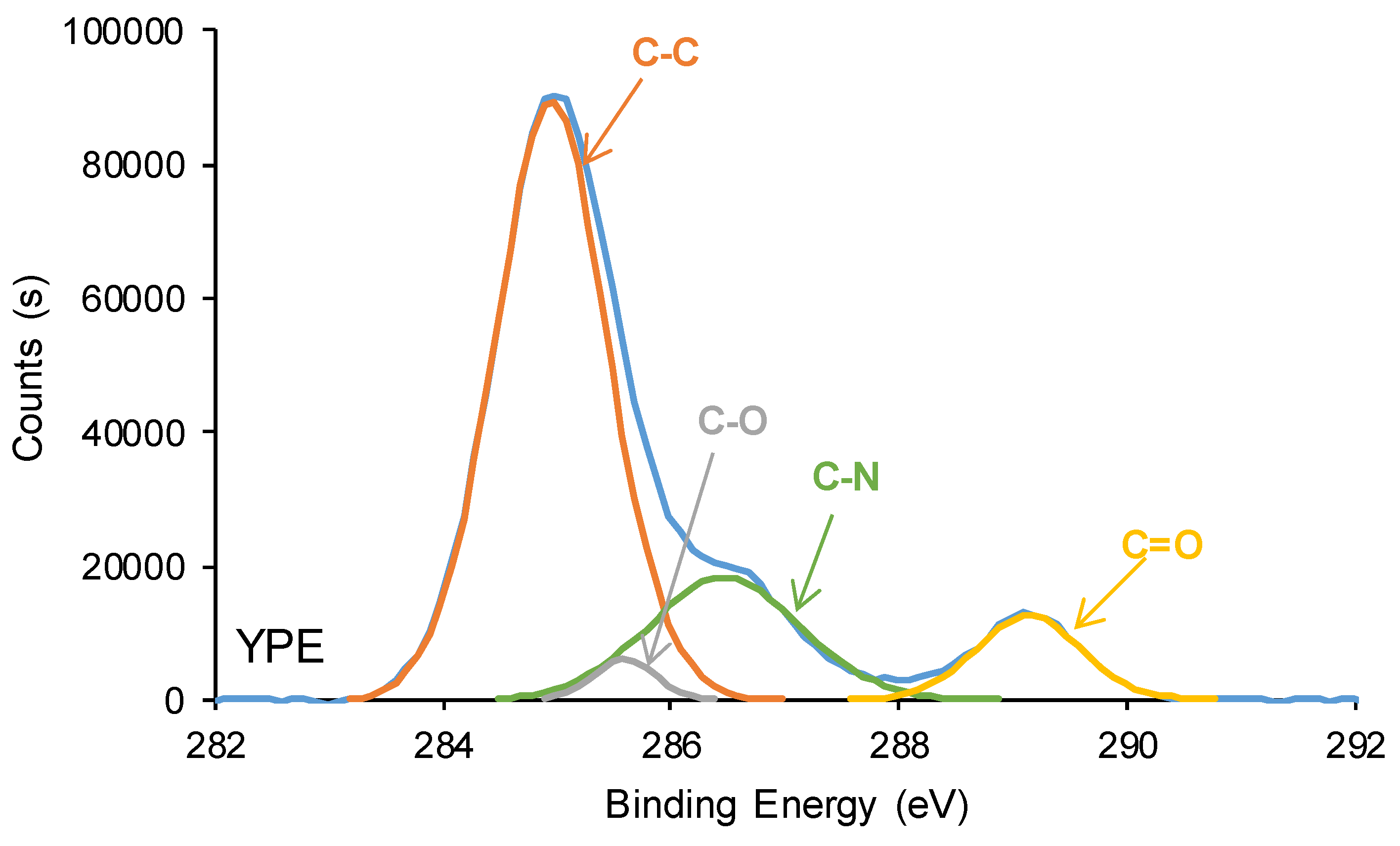

3.3. Surface Properties of the PUs

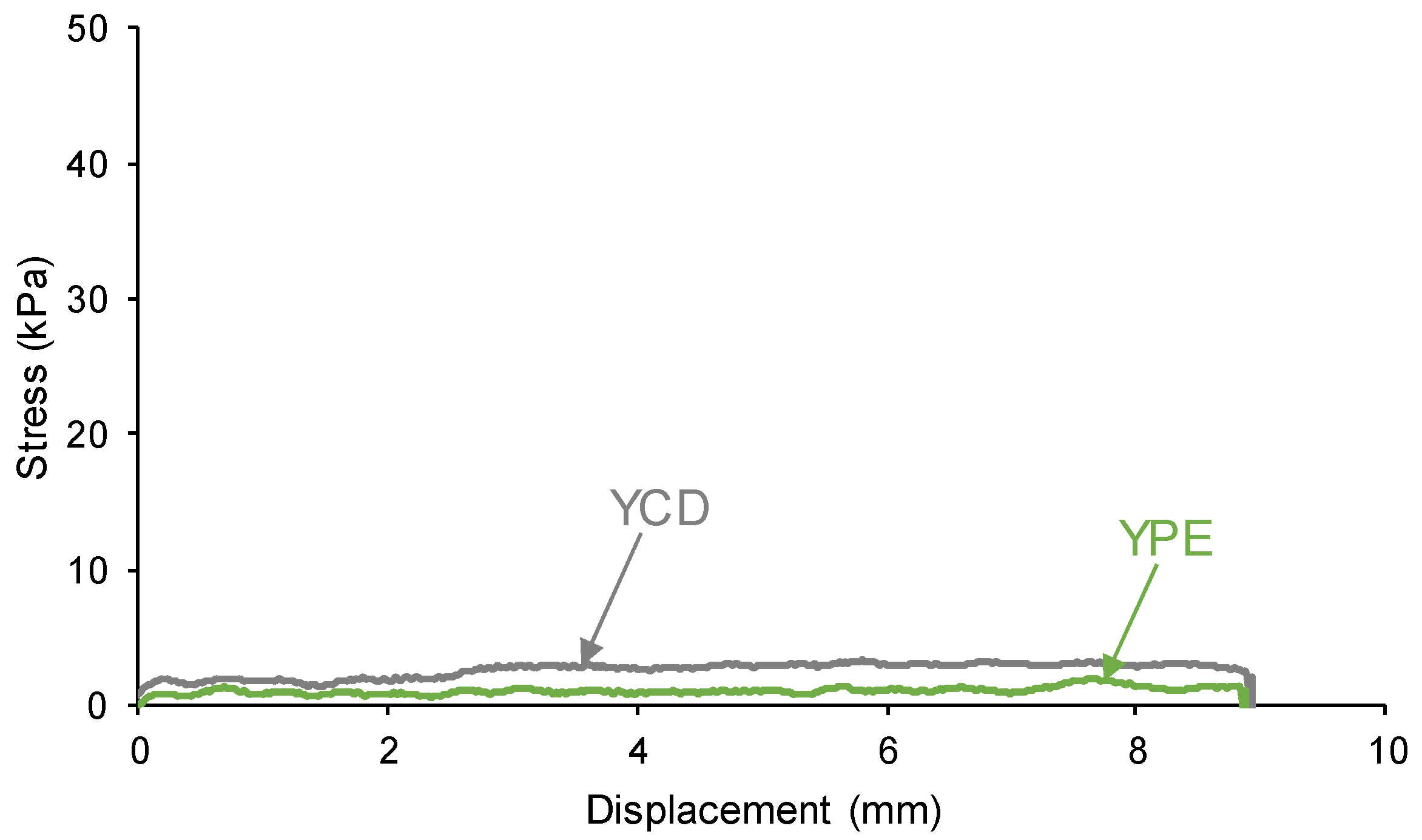

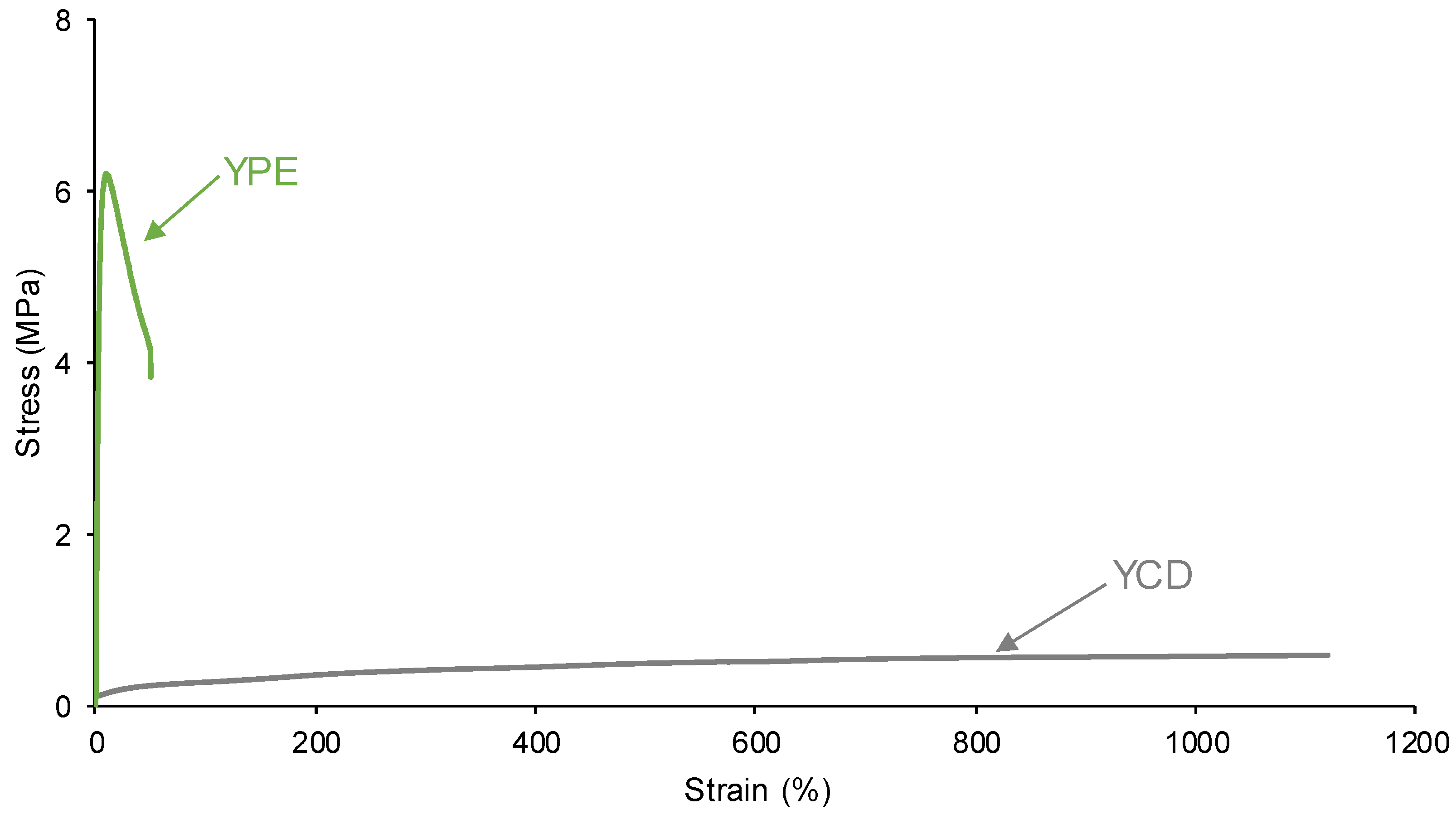

3.4. Mechanical Properties of the PUs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, M. Q.; Rong, M. Z. Extrinsic and intrinsic approaches to self-healing polymers and polymer composites, John Wiley & Sons, 2022.

- Wen, N.; Song, T.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z. Recent advancements in self-healing materials: Mechanicals, performances and features. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 168, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzima, B. J.; Kloxin, C. J.; Bowman, C. N. Externally triggered healing of a thermoreversible covalent network via self-limited hysteresis heating. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2784–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshie, N.; Watanabe, M.; Araki, H.; Ishida, K. Thermo-responsive mending of polymers crosslinked by thermally reversible covalent bond: Polymers from bisfuranic terminated poly (ethylene adipate) and tris-maleimide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, B. D.; Singh, S. P.; Bowman, C. N.; Anseth, K. S. Photodegradable, photoadaptable hydrogels via radical-mediated disulfide fragmentation reaction. Macromolecules. 2011, 44, 2444–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.; Jia, H.; Gu, S. Y. A transparent, highly stretchable, self-healing polyurethane based on disulfide bonds. European Polymer Journal. 2019, 112, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, D. Self-healing polyurethane/attapulgite nanocomposites based on disulfide bonds and shape memory effect. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 195, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Yu, C.; Fei, G.; Wang, Z.; Xia, H. A facile strategy for self-healing polyurethanes containing multiple metal–ligand bonds. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1700678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dam, M. A.; Ono, K.; Mal, A.; Shen, H.; Nutt, S. R.; Sheran, K.; Wudl, F. A thermally re-mendable cross-linked polymeric material. Science 2002, 295, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrhardt, D.; Van Durme, K.; Jansen, J. F.; Van Mele, B.; Van den Brande, N. Self-healing UV-curable polymer network with reversible Diels-Alder bonds for applications in ambient conditions. Polymer 2020, 203, 122762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, K. K.; Nam, J.; Kim, E.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T. H. A self-healable polymer binder for Si anodes based on reversible Diels–Alder chemistry. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 364, 137311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, S.; Gao, C.; Xu, X.; Bai, X.; Duan, H.; Gao, N.; Feng, C.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, M. Injectable and self-healing carbohydrate-based hydrogel for cell encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015, 7, 13029–13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C. M.; Roh, Y. S.; Cho, S. Y.; Kim, J. G. Crack healing in polymeric materials via photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3982–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Jin, H.; Shao, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Gan, L.; Long, M. Polysaccharide-based fast self-healing ion gel based on acylhydrazone and metal coordination bonds. Mater. Des. 2020, 192, 108723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, J. H.; Liu, Z. Q.; Xu, F.; Zhou, J. X.; Zrínyi, M.; Osada, Y.; Chen, Y. M. Novel biocompatible polysaccharide-based self-healing hydrogel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Fu, S. Facile strategy to construct a self-healing and biocompatible cellulose nanocomposite hydrogel via reversible acylhydrazone. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 218, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Jian, X. Self-healing alginate hydrogel based on dynamic acylhydrazone and multiple hydrogen bonds. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 8814–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amamoto, Y.; Kamada, J.; Otsuka, H.; Takahara, A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Repeatable photoinduced self-healing of covalently cross-linked polymers through reshuffling of trithiocarbonate units. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1660–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Cui, K.; Xu, F.; Jiang, T.; Ma, Z. Synthesis of new ionic crosslinked polymer hydrogel combining polystyrene and poly (4-vinyl pyridine) and its self-healing through a reshuffling reaction of the trithiocarbonate moiety under irradiation of ultraviolet light. Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. A.; Kamada, J.; Koynov, K.; Mohin, J.; Nicolaÿ, R.; Zhang, Y.; Balazs, A. C.; Kowalewski, T.; Matyjaszewski, K. Self-healing polymer films based on thiol–disulfide exchange reactions and self-healing kinetics measured using atomic force microscopy. Macromolecules. 2012, 45, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadell, J.; Goossens, H.; Klumperman, B. Self-healing materials based on disulfide links. Macromolecules. 2011, 44, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y. A molecular dynamics simulation on self-healing behavior based on disulfide bond exchange reactions. Polymer. 2021, 212, 123111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, Z.; Rong, J.; Yang, K.; Zhou, J.; Shen, L.; Gao, F.; Huang, X.; He, H. A high stiffness and self-healable polyurethane based on disulfide bonds and hydrogen bonding. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 124, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Sheng, D.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, S.; Xie, H.; Tian, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, B.; Yang, Y. High performance and near body temperature induced self-healing thermoplastic polyurethane based on dynamic disulfide and hydrogen bonds. Polymer 2021, 214, 123261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H.; Shin, S. R.; Lee, D. S. Self-healing of cross-linked PU via dual-dynamic covalent bonds of a Schiff base from cystine and vanillin. Mater. Des. 2019, 172, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imato, K.; Nishihara, M.; Kanehara, T.; Amamoto, Y.; Takahara, A.; Otsuka, H. Self-healing of chemical gels cross-linked by diarylbibenzofuranone-based trigger-free dynamic covalent bonds at room temperature. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, P.; Tournilhac, F.; Soulié-Ziakovic, C.; Leibler, L. Self-healing and thermoreversible rubber from supramolecular assembly. Nature 2008, 451, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, M.; Zhang, L.; He, B.; Chen, X.; Sun, J. Facile synthesis of self-healing and layered sodium alginate/polyacrylamide hydrogel promoted by dynamic hydrogen bond. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 256, 117580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J. Novel high-strength thermoplastic starch reinforced by in situ poly (lactic acid) fibrillation. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2009, 294, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydovich, D.; Urban, M. W. Water accelerated self-healing of hydrophobic copolymers. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Hao, B.; Ge, P.; Chen, S. Highly stretchable, self-healing, and 3D printing prefabricatable hydrophobic association hydrogels with the assistance of electrostatic interaction. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 4741–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, T.; Yu, Z.; Wang, F.; Shi, D.; Ni, Z.; Chen, M. Effects of surfactant and ionic concentration on properties of dual physical crosslinking self-healing hydrogels by hydrophobic association and ionic interactions. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 4061–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S.; Greenland, B. W.; Merino, D. H.; Weng, W.; Seppala, J.; Colquhoun, H. M.; Hayes, W.; Mackay, M. E.; Hamley, I. W.; Rowan, S. J. A healable supramolecular polymer blend based on aromatic π− π stacking and hydrogen-bonding interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12051–12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burattini, S.; Greenland, B. W.; Hayes, W.; Mackay, M. E.; Rowan, S. J.; Colquhoun, H. M. A supramolecular polymer based on tweezer-type π−π stacking interactions: Molecular design for healability and enhanced toughness. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Peng, J.; Yan, N.; Yu, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Fang, Y. Simple design but marvelous performances: Molecular gels of superior strength and self-healing properties. Soft Matter. 2013, 9, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnworth, M.; Tang, L.; Kumpfer, J. R.; Duncan, A. J.; Beyer, F. L.; Fiore, G. L.; Rowan, S. J.; Weder, C. Optically healable supramolecular polymers. Nature. 2011, 472, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Yang, K.; Cui, Y. Self-healing flexible sensor based on metal-ligand coordination. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2020, 394, 124932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, K.; Guo, K.; Yuan, L.; Wu, Y.; Gao, C. A novel type of self-healing silicone elastomers with reversible cross-linked network based on the disulfide, hydrogen and metal-ligand bonds. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 144, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Hu, Z. Disulfide bonds and metal-ligand co-crosslinked network with improved mechanical and self-healing properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2017, 13, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mynar, J. L.; Yoshida, M.; Lee, E.; Lee, M.; Okuro, K.; Kinbara, K.; Aida, T. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature. 2010, 463, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, G.; Wu, J. Strong and tough self-healing elastomers enabled by dual reversible networks formed by ionic interactions and dynamic covalent bonds. Polymer. 2018, 157, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Yang, P.; Yi, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, T.; Shu, C.; Qu, L.; Tang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, B. Self-healing and high stretchable polymer electrolytes based on ionic bonds with high conductivity for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources. 2020, 450, 227629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, A.; Roger, E.; Phoeung, T.; Antheaume, C.; Orthlieb, C.; Boulmedais, F.; Lavalle, P.; Schlenoff, J. B.; Frisch, B.; Schaaf, P. On the benefits of rubbing salt in the cut: Self-healing of saloplastic PAA/PAH compact polyelectrolyte complexes. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2547–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, X.; Urban, M. W. Chemical and physical aspects of self-healing materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 49, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A. V.; Madras, G.; Bose, S. The journey of self-healing and shape memory polyurethanes from bench to translational research. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 4370–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, H. Viscosity, plasticity, and diffusion as examples of absolute reaction rates. J. Chem. Phys. 1936, 4, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P. J.; Krigbaum, W. R. Statistical mechanics of dilute polymer solutions. II. J. Chem. Phys. 1950, 18, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, R.; Boyer, R. F. On a general relation involving the glass temperature and coefficients of expansion of polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 1962, 37, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, A. M.; Bijleveld, J. C.; Garcia, S. J.; Van Der Zwaag, S. A combined fracture mechanical–rheological study to separate the contributions of hydrogen bonds and disulphide linkages to the healing of poly (urea-urethane) networks. Polymer 2016, 96, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschweiler, N.; Keul, H.; Millaruelo, M.; Weberskirch, R.; Moeller, M. Synthesis of α, ω-isocyanate telechelic polymethacrylate soft segments with activated ester side functionalities and their use for polyurethane synthesis. Polym. Int. 2014, 63, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljanšek, I.; Fabjan, E.; Moderc, D.; Kukanja, D. The effect of free isocyanate content on properties of one component urethane adhesive. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2014, 51, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H. J.; Boyce, M. C. Stress–strain behavior of thermoplastic polyurethanes. Mech. Mat. 2005, 37, 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilgör, I.; Yilgör, E.; Wilkes, G. L. Critical parameters in designing segmented polyurethanes and their effect on morphology and properties: A comprehensive review. Polymer 2015, 58, A1–A36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Xin, A.; Feng, Z.; Lee, K. H.; Wang, Q. Mechanics of self-healing thermoplastic elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2020, 137, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirresarobe, R. H.; Nevejans, S.; Reck, B.; Irusta, L.; Sardon, H.; Asua, J. M.; Ballard, N. Healable and self-healing polyurethanes using dynamic chemistry. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 114, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J. W.; Kim, J. W.; Jung, Y. C.; Goo, N. S. Electroactive shape-memory polyurethane composites incorporating carbon nanotubes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2005, 26, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, D. A novel self-healing polyurethane based on disulfide bonds. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016, 217, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, D. Shape memory-assisted self-healing polyurethane inspired by a suture technique. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 10582–10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y. M.; Kim, Y. O.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S. K.; Lee, J. S.; Park, M.; Chung, J. W.; Jung, Y. C. Robust and stretchable self-healing polyurethane based on polycarbonate diol with different soft-segment molecular weight for flexible devices. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, R. P.; Beijer, F. H.; Brunsveld, L.; Folmer, B. J.; Hirschberg, J. K.; Lange, R. F. : Lowe, J. K. L.; Meijer, E. W. Reversible polymers formed from self-complementary monomers using quadruple hydrogen bonding. Science 1997, 278, 1601–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamiryan, D.; Abell, T.; Iacopi, F.; Maex, K. Low-k dielectric materials. Materials Today. 2004, 7, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D. H.; Slark, A. T.; Colquhoun, H. M.; Hayes, W.; Hamley, I. W. Thermo-responsive microphase separated supramolecular polyurethanes. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, A.; Nedolisa, C.; Houton, K. A.; Lindsay, C. I.; Saiani, A.; Wilson, A. J. Tunable self-assembled elastomers using triply hydrogen-bonded arrays. Macromolecules. 2012, 45, 4723–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feula, A.; Pethybridge, A.; Giannakopoulos, I.; Tang, X.; Chippindale, A.; Siviour, C. R.; Buckley, C. P.; Hamley, I. W.; Hayes, W. A thermoreversible supramolecular polyurethane with excellent healing ability at 45 C. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 6132–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Heng, X.; Guifeng, X.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Guo, X. Rapid self-healing and tough polyurethane based on the synergy of multi-level hydrogen and disulfide bonds for healing propellant microcracks. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pacios, V.; Costa, V.; Colera, M.; Martín-Martínez, J. M. Affect of polydispersity on the properties of waterborne polyurethane dispersions based on polycarbonate polyol. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2010, 30, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. M.; Jeon, H.; Shin, S. H.; Park, S. A.; Jegal, J.; Hwang, S. Y.; Oh, D. X.; Park, J. Superior toughness and fast self-healing at room temperature engineered by transparent elastomers. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Duan, N.; Chen, S.; Guo, Z.; Hu, J.; Guo, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L. Synthesis, mechanical properties and self-healing behavior of aliphatic polycarbonate hydrogels based on cooperation hydrogen bonds. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2020, 319, 114134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Yang, L. Flexible segments regulating the gelation behaviours of aliphatic polycarbonate gels with excellent shape memory and self-healing properties. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 364, 120015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Han, S.; Guo, J.; Yang, L.; Hu, J. Physical cross-linked aliphatic polycarbonate with shape-memory and self-healing properties. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 381, 121798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. W.; Zhang, Y. Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G. P.; Xu, Z. K.; Darensbourg, D. J. Construction of autonomic self-healing CO2-based polycarbonates via one-pot tandem synthetic strategy. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matějka, L.; Špírková, M.; Dybal, J.; Kredatusová, J.; Hodan, J.; Zhigunov, A.; Šlouf, M. Structure evolution during order–disorder transitions in aliphatic polycarbonate based polyurethanes. Self-healing polymer. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 357, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, M.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Z. Self-healing polycarbonate-based polyurethane with shape memory behavior. Macromol. Res. 2019, 27, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colera-Llavata, M.; Costa-Vayá, V.; Jofre-Reche, J.A.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Self-healing polyurethane polymers. 2016, Patent. EP 3103846 A1, Europe.

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Carpena-Montesinos, J.; Martín-Martínez, J. M. Innovative device and procedure for in situ quantification of the self-healing ability and kinetics of self-healing of polymeric materials. Polymers 2023, 15, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuensanta, M.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Thermoplastic polyurethane coatings made with mixtures of polyethers of different molecular weights with pressure sensitive adhesion property. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 118, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, A.; Piegat, A.; Olalla, Á. S.; El Fray, M. New approach to evaluate microphase separation in segmented polyurethanes containing carbonate macrodiol. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 93, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princi, E.; Vicini, S.; Castro, K.; Capitani, D.; Proietti, N.; Mannina, L. On the micro-phase separation in waterborne polyurethanes. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2009, 210, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuensanta, M.; Khoshnood, A.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Structure–properties relationship in waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s synthesized with dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA) internal emulsifier added before, during and after prepolymer formation. Polymers 2020, 12, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Martín-Martínez, J. M. Understanding the interactions between soft segments in polyurethanes: Structural synergies in blends of polyester and polycarbonate diol polyols. Polymers 2023, 15, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PU | Mn (Da) | Mw (Da) | Mz (Da) | PDI |

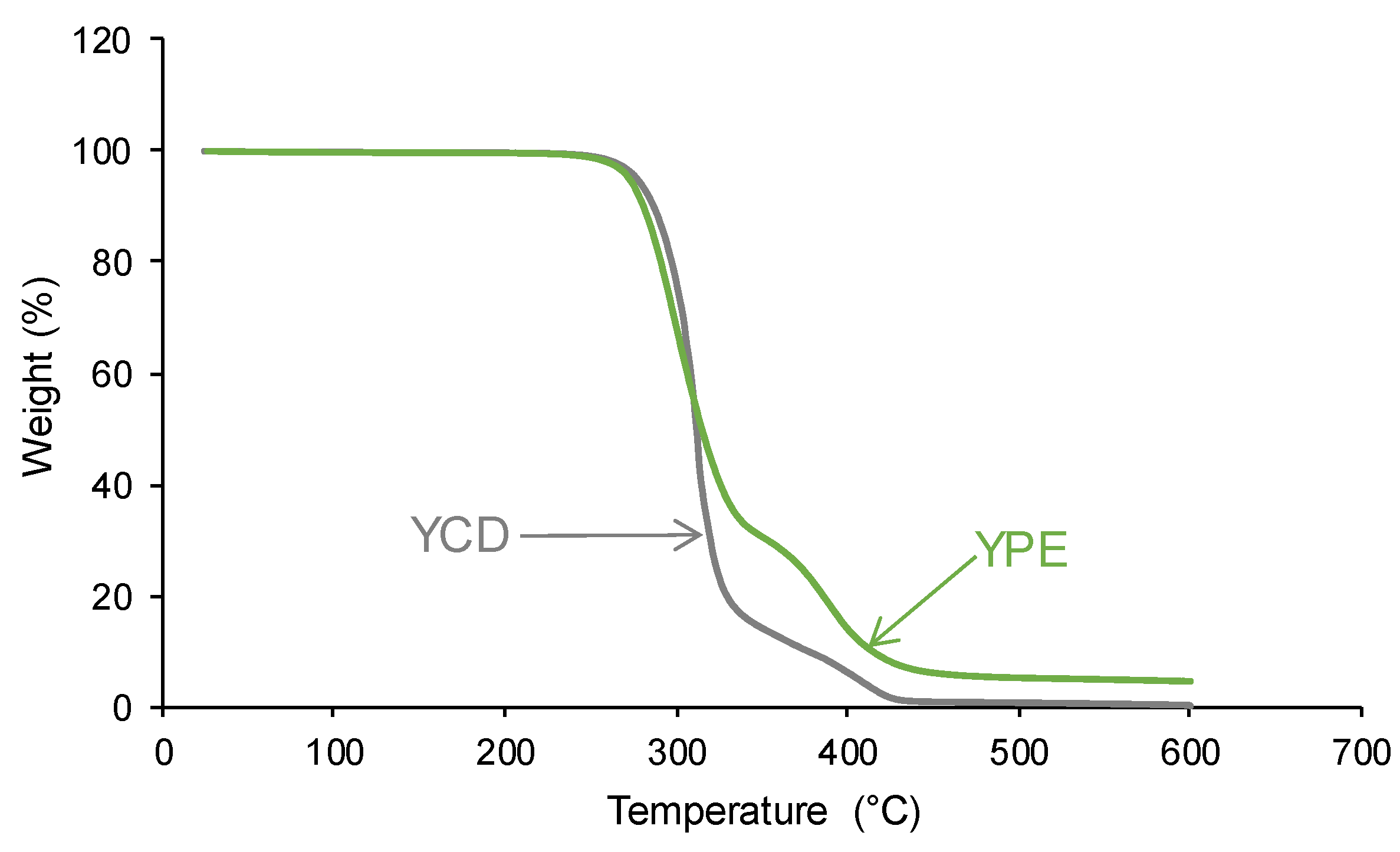

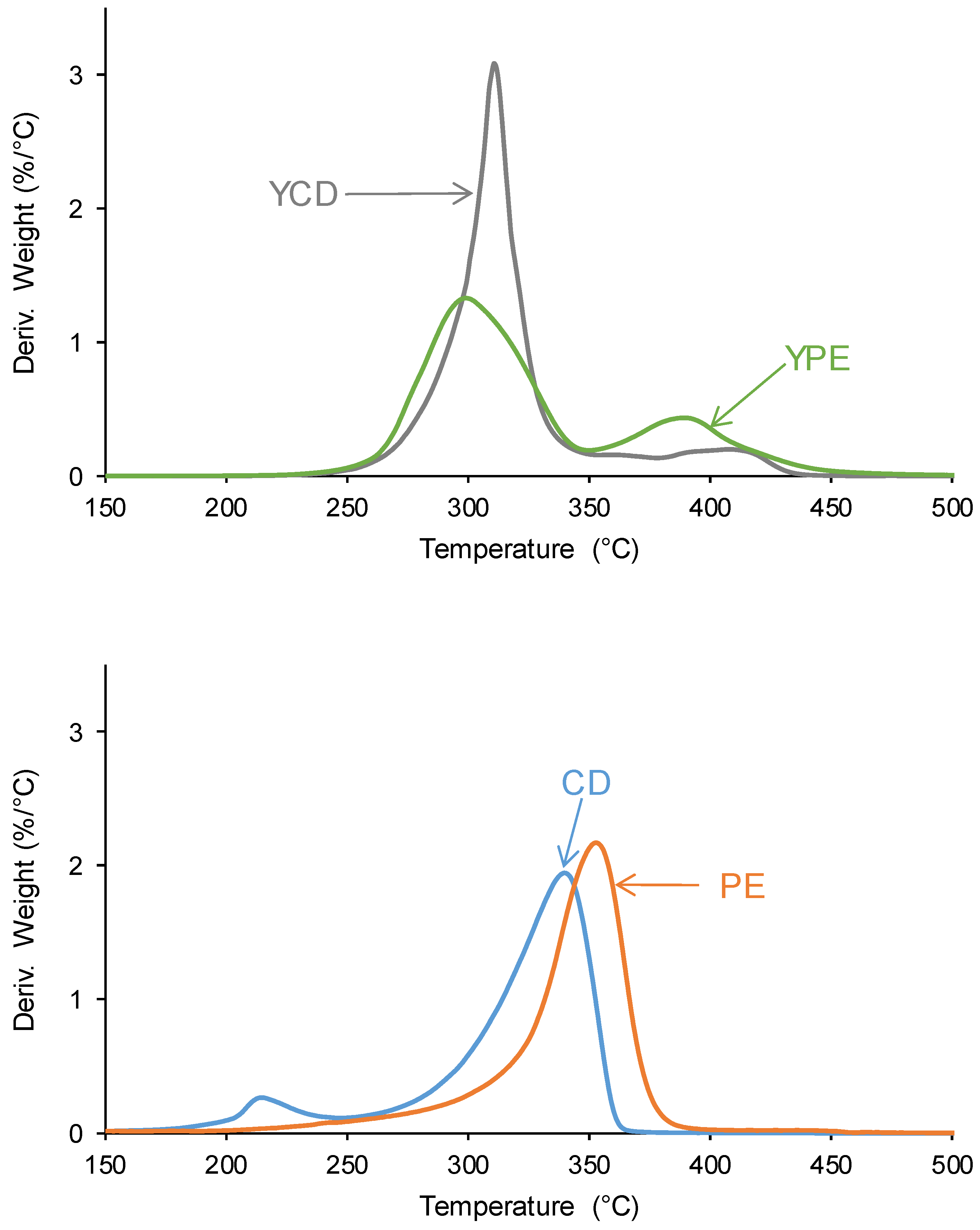

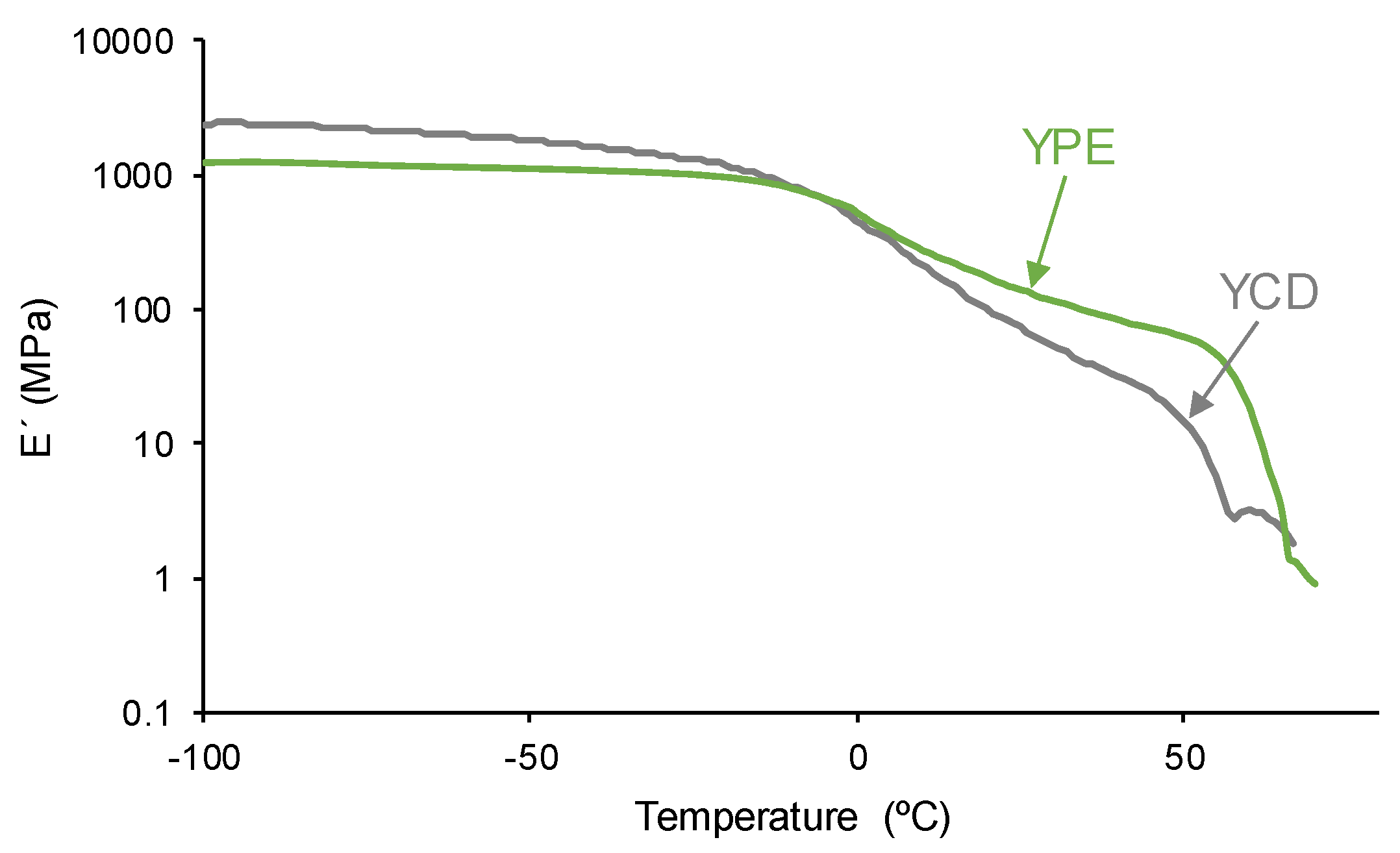

| YCD | 19762 | 66779 | 178483 | 3.4 |

| YPE | 16986 | 40299 | 82150 | 2.4 |

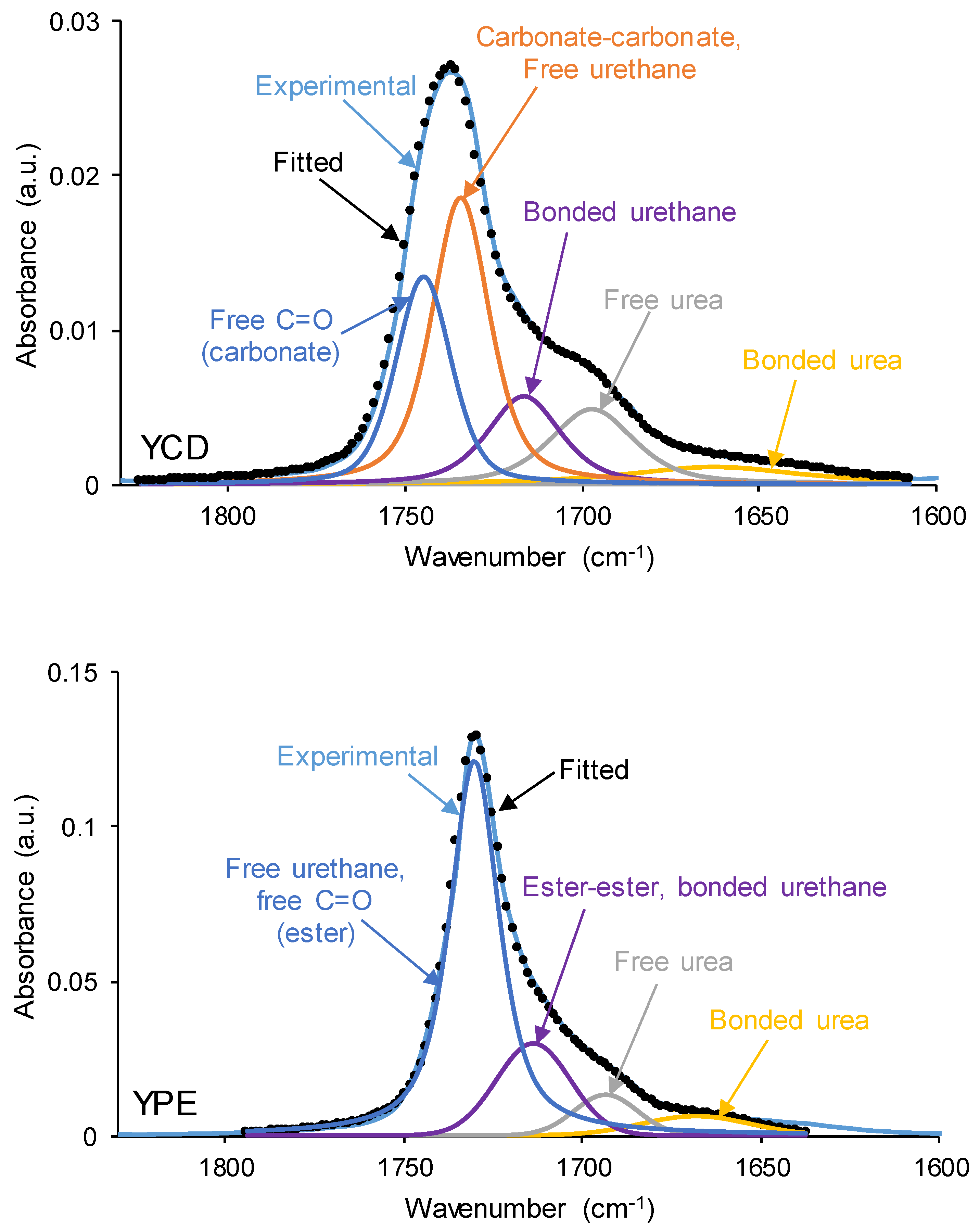

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | YCD | YPE | Assignment |

| 1653-1667 | 9 | 8 | Bonded urea |

| 1692-1695 | 15 | 10 | Free urea |

| 1716-1719 | 14 | 26 | Ester-ester, bonded urethane |

| 1726-1732 | 38 | 56 | Carbonate-carbonate, Free C=O (ester), free urethane |

| 1742 | 24 | - | Free C=O (carbonate) |

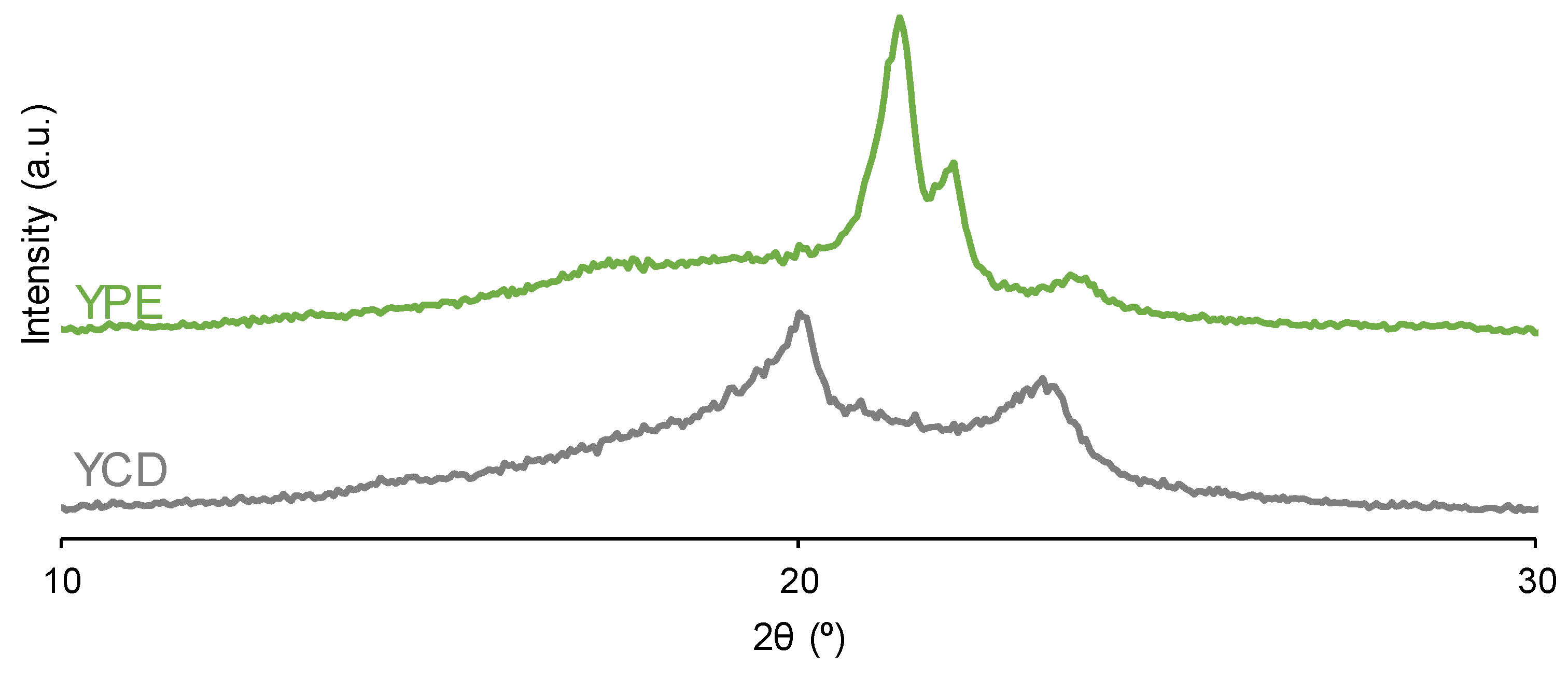

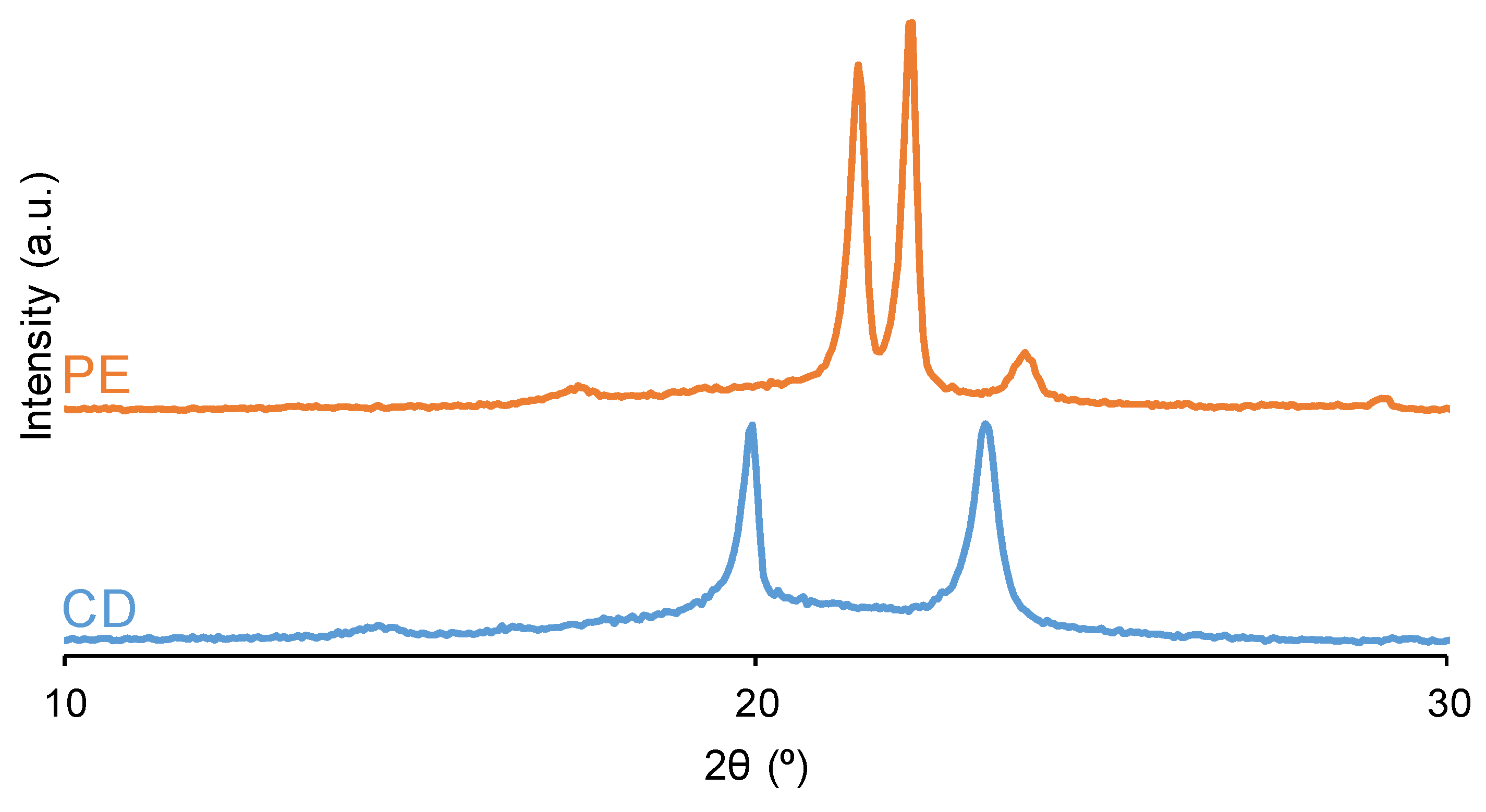

| PU | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) |

| YCD | 20 | 3186 | - | - | - | - | 23 | 1677 | - | - |

| YPE | - | - | 21 | 4182 | 22 | 2092 | - | - | 24 | 859 |

| Polyol | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | Intensity (a.u.) |

| CD | 20 | 3825 | - | - | - | - | 23 | 3891 | - | - |

| PE | - | - | 21 | 6042 | 22 | 6759 | - | - | 24 | 1035 |

| Species | Percentage (at.%) | |

| YCD | YPE | |

| C-C, C-H (B.E. = 284.9 eV) | 83 | 69 |

| C-O (B.E. = 285.5-285.6 eV) | 7 | 3 |

| C-N (B.E. = 286.6-286.9 eV) | 7 | 19 |

| C=O (B.E. = 289.1-289.2 eV) | 2 | 9 |

| O-(C=O)-O (B.E. = 290.8 eV) | 1 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).