1. Introduction

The free movement of goods and services and open borders make the EU market a haven for online traders and service providers, at the same time, the lack of full tax harmonization makes life more difficult for businesses and tax administrations. The cross-border tax and legal environment may differ between countries, regions or even cities. Different areas may have different tax rates, deadlines, tax rules, and cross-border legislation is complex and frequently changing. Businesses must deal with differences between countries, so they need to be familiar with several types of tax, such as Value Added Tax (VAT), Goods and Services Tax (GST), customs duties and import charges. The VAT rates highlighted in our study vary from country to country, in many cases, it is the seller's responsibility to determine the tax rates applicable to their goods and services in the other Member State.

The relevance of the research lies in the fact that cross-border e-commerce businesses in the European Union are subject to overly complex and often opaque VAT rules due to a lack of tax harmonization. Start-ups, smaller businesses, and resource-poor firms may not be able to automate their tax processes, which can be a barrier to further market penetration, thus reducing their competitiveness. Our research covers e-commerce businesses across the EU, especially those operating electronic interfaces and platforms. Value added tax (VAT) is the main focus of our study as it is, in our opinion, the most important and complex tax that affects the tax rules for e-commerce companies. Other taxes are not analyzed because their size is negligible compared to the VAT tax burden.

The aim of the research is to explore, using a qualitative method, what kind of harmonization would make the current legislation more uniform, simpler, more transparent, and easier to understand, without conflicting with the rules of any Member State. To this end, the aspects of the new platform regulation introduced on 1 July 2021 and its potential for expansion is assessed through information from the sales models.

First, we outline the theoretical framework of the topic in the context of the European Union, with a particular focus on VAT issues for e-commerce businesses. In terms of the nature of the activity, a distinction is made between cases covered by the regulation of agency activities, intermediary services and platforms. This is followed by a description of the possibilities and limitations of the OSS system for VAT compliance in the European Union. Finally, we highlight the importance of tax harmonization and the current problems for e-commerce businesses.

The sale of goods and provision of services in the digital space can take place in several scenarios, depending on where the seller and the buyer are physically located, and whether they use intermediate, third-party intermediary services or transport. Tax issues can be further complicated by whether the buyer and seller are taxable persons. In the discussion section of the paper, we outline different sales models based on these factors, and use them to highlight the shortcomings of the new platform rule. At the end of our study, we make proposals on how to extend the new platform legislation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study examines the tax issues for firms operating in the field of cross-border e-commerce, with a particular focus on VAT. The scope of this study applies to 2023 in EU context, from a Hungarian perspective mainly. In our research we examined e-commerce companies in the EU, especially those operating electronic interfaces and platforms. Sales within the EU and outside the EU are included, as well as B2B and B2C transactions.

We have distinguished between cases subject to agency activities, intermediated services, and platform regulation, depending on the nature of the underlying activity. Based on the changes brought by the new platform regulation in force since 1 July 2021, we have explored the main conditions and impacts of using an OSS system that brings administrative ease. In our research, we investigated the tax liability of a platform operator in each sales scenario in the light of the VAT legislation in 2023. The sale of goods and services in the digital space can take place in several scenarios, depending on where the seller and buyer are physically located, and whether they use third-party intermediary services or transport. Tax issues can be further complicated by whether the buyer and seller are taxable persons. Following the outlining of the sales models, we explore how a legislative change would make the current rules more uniform, simpler, more transparent, and easier to understand, without conflicting with the rules of any Member State.

The research methodology can be considered as summative evaluative research, assessing the current state of the EU e-commerce situation created by the platform regulation, with a particular focus on the VAT regulation and the associated tax liability. Following a synthesis of current tax options, we qualitatively outline a total of 9 different scenarios through content analysis. Finally, conducting scenario analysis, we propose tax harmonization through making recommendations for the extension of the new platform rule.

3. Results

The impact of digitalization and disruptive technologies has revolutionized the field of finance, and the resulting platformization is strongly shaping the delivery of financial services. The pandemic has further increased the digital presence of businesses and consumers, resulting in a regulatory and tax environment full of challenges and opportunities [

1,

2]. Most of the sales of goods and services in the digital space are cross-border transactions, so the tax issues can be complex e.g. within the European Union.

According to Póta and Becsky-Nagy, only those financial service providers that continuously modernize their technology to meet customer needs will remain competitive [

1]. But technological progress can also make a major contribution to more efficient and traceable compliance with tax obligations in several countries at the same time.

The minimum standard rate of VAT, which is the highest in the EU and therefore the focus of our research, is 15%, but each country sets the tax at its own discretion. Member States may also apply reduced tax rates, which should not be less than 5% [

3].

3.1. VAT Rules on Agency Activities with Hungarian Examples

Agency activity is an economic event between an agent, their principal and a third party. The object of the mandate is typically to facilitate the sale of a product or service owned by the agent's principal. Under Hungarian VAT law, agent activity is taxed as a supply of services, regardless of whether the agent is involved in the supply of goods or services. The standard rate of tax on agency services provided in the country is 27% of the taxable amount. If the agent is involved in a transaction subject to the reverse charge rule, this does not affect the amount of tax on the agent's activities, as the transaction itself is between the agent’s principal and the buyer. This means that if the agent is not exempt, he will charge 27% VAT to their principal, regardless of whether the facilitated service is subject to the reverse charge rules. As the agent acts in the name and on behalf of the principal, there is no legal relationship between the agent and the buyer. It follows that the invoicing obligation arising from the sale is borne by the principal, since the transaction is effectively between the principal and the buyer. As for the remuneration due to the agent, the agent invoices the principal.

Determining the place of supply is important because it determines whether the service is subject to VAT. Where the agent provides a service to a taxable person, the place of supply is, under the general rules, the place where the taxable person (customer) is established, or the permanent establishment of the party most directly concerned by the use of the agency service. If a domestic taxable person uses the services of an agent who does not have a permanent establishment in the country, the place of supply is domestic, and tax (27% VAT) is payable by the resident taxable person making use of the service.

If the recipient (principal) of the agency service is a taxable person who does not have a registered office or permanent establishment in the country, the agency service is not taxable, as the place of supply is not in the country but in another Member State or a country outside the Community. In this case, VAT is not charged on the consideration for the service. If the agent provides services to a non-taxable person, the place of supply is the place where the transaction is actually carried out.

If the agent provides services to a non-taxable principal and the place of performance of the transaction is domestic, then the agency activity is also performed domestically. Since the facts necessary for exemption cannot arise in the case of agency services provided to a non-taxable person, the VAT rate to be charged will be 27%. If the place of performance of the transaction is not domestic, the agency activity is also not performed domestically, which is not taxable and therefore VAT is not charged [

4].

3.2. Rules on Intermediated Services in Hungary

According to the Hungarian Accounting Law, an intermediary service is defined as a service purchased by an enterprise on its own behalf and resold (re-invoiced) in whole or in part but in unchanged form to a third party (the customer) under a contract, in the manner specified in the contract. In an intermediated service, the enterprise is both the buyer and the provider of the service. The enterprise mediates all or part of the purchased service in such a way that the possibility of mediation can be clearly established from the contract with the customer, the fact of mediation can be clearly established from the invoice, i.e. that the trader sells not only his own service but also the service he has purchased in an unchanged form, but not necessarily at the same price [

5].

The Hungarian VAT Law does not define an intermediated service, but it does stipulate that it should be treated as two separate economic events (and thus VAT should be examined separately), the first being the purchase of the service and the second the resale in an unaltered form. A written contract must be concluded with the customer. The invoice must show separately the intermediated service and the own service and must include the mandatory note "The invoice includes an intermediated service". The sale price and the purchase price may differ, and the place of supply and VAT rate may also be different, so only the service, i.e. the subject of the contract, is the same. For example, for a sub-billed internet service, there are two options. In the first case, it is invoiced as a stand-alone service, so the reduced VAT rate applies (5%), in the second case, if it is linked to one of their activities (e.g. it can be used in addition to a telephone service), it is subject to the main service VAT rate (27%) [

6].

According to Simić [

7], the definition of intermediated services in the proposed DST Directive is not always clear, which allows for different interpretations of Member States. A further source of problems is the relatively confusing definition of exceptions to the general definition of taxable intermediate services, which does not make a transitional solution easy to implement in a short timeframe.

3.3. Specific Rules for Online Marketplaces and Platforms

According to NAV [

8], most distance sales between Member States and even from third countries to the Community are made via an electronic interface, such as an online marketplace, platform or portal. In the following, we look at the new EU VAT rules for e-commerce that have entered into force on 1 July 2021, focusing on the rules for platforms.

This provision applies only to B2C distance sales of goods imported from countries outside EU jurisdiction with an intrinsic value not exceeding EUR 150. In addition, the provision also applies to intra-EU B2C sales if the seller is not established in the EU. The new rules affect taxable persons who facilitate [

9] distance sales of products through platform interfaces. It involves them in the collection of VAT on sales and makes them liable to pay tax on certain goods sold through them. Accordingly, in the case of certain supplies to non-taxable persons (B2C), there is a special role for the taxable persons operating the platforms. Under the new rules, taxable persons who act as intermediaries for certain B2C supplies of goods will be deemed to have bought and sold the goods themselves. This means that a single sale from the intermediary service provider to the final consumer is split into two deemed sales:

sales from the supplier to the intermediary (sales considered as B2B sales),

sales by the intermediary to the final consumer (sales considered as B2C sales). Any intermediation services provided by an intermediary are disregarded for VAT purposes.

Accordingly, this case should be treated as if there were two sales of goods: the first transaction is between the original seller and the platform and the second transaction is between the platform and the buyer. Thus, platforms are liable to pay tax on the transactions they facilitate. Sales to the intermediary platform are VAT-free and sales made by the platform follow the e-commerce VAT rules. So, platforms are obliged to collect and remit VAT on sales made through their platform.

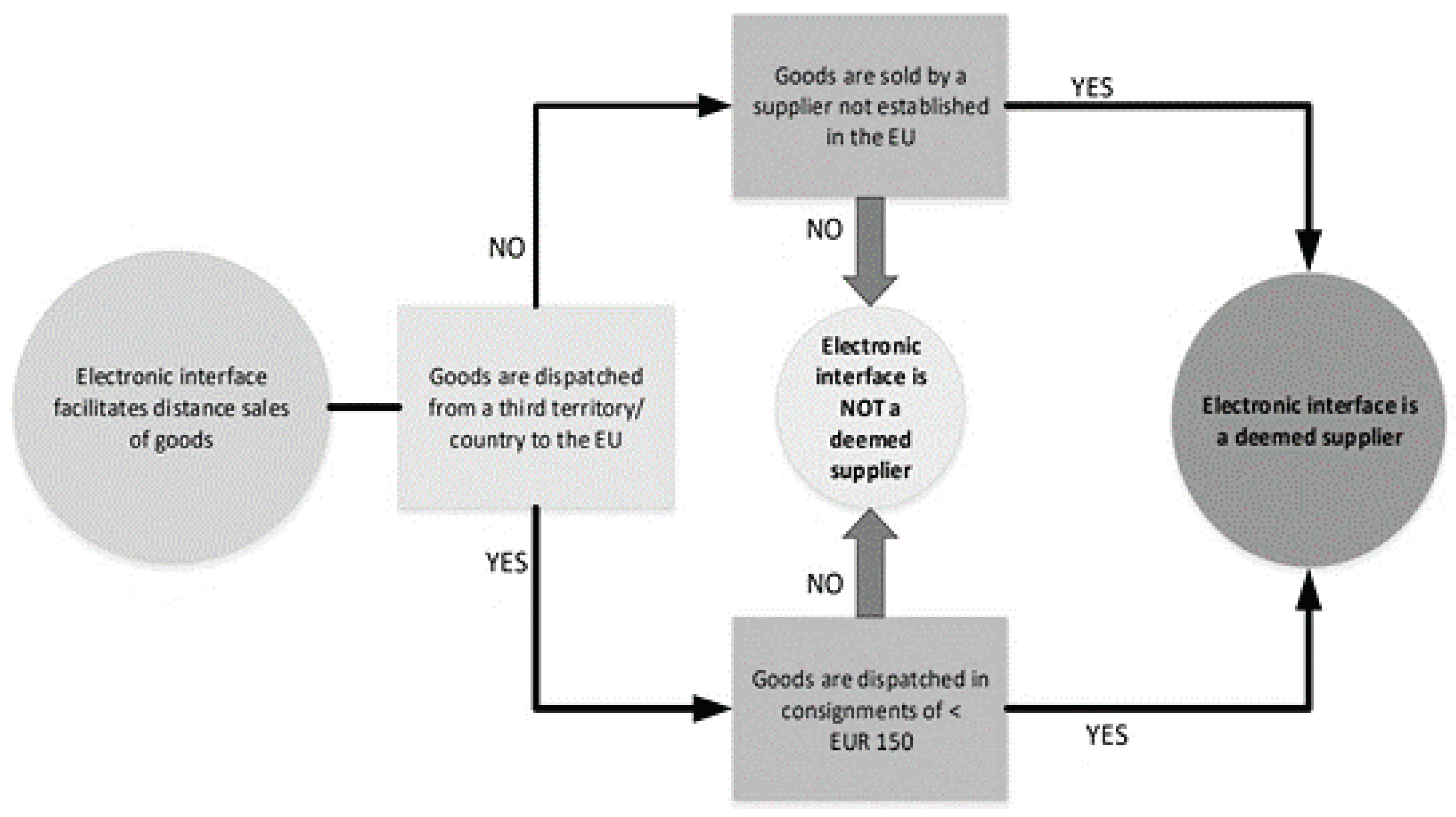

From 1 July 2021, operators of marketplaces and so-called "electronic interfaces" may also face new VAT rules; the so-called deemed supplier rule. The EU definition of electronic interfaces (EI) is a broad concept that allows communication between two independent systems or between a system and an end-user using a device or program. An electronic interface can include a website, portal, gateway, marketplace, application programming interface (API), etc. [

10]. Generally, online sellers must declare VAT on their sales, unless the operator of the electronic interface (e.g. Amazon or Alibaba) is a deemed supplier. The operator of an electronic platform is a deemed supplier if the recipient of the product is the consumer and if (see

Figure 1):

the goods are within the EU and the online seller is outside the EU,

the goods are outside the EU and must be imported into the EU.

Here the intrinsic value must not exceed EUR 150 (the location of the online seller is irrelevant in this scenario) [

11].

If one of the above scenarios applies, the operator of the electronic interface is considered to be a supplier and is liable to declare and pay VAT. The operator can use the One Stop Shop (OSS) to declare intra-Community distance sales. However, the operator may also declare a local sale of goods if they are the deemed supplier [

11]. The deemed supplier status of a platform is independent of whether it is a domestic taxable person, a taxable person established in another Member State of the Community or a taxable person in a third country. The deemed supplier status of the platform in this case exists when it facilitates the supply of goods already in free circulation in the Community to a non-taxable person within the Community, where the taxable person who actually supplies the goods is not established in the Community. If the platform only makes intra-Community sales, it is neither an EI nor a deemed supplier.

3.4. One Stop Shop – OSS System

Where a business is not a local supplier, it can choose to register for VAT in each Member State and account for VAT on all its supplies in accordance with local rules or reclaim input tax [

13]. However, this choice represents a very heavy administrative burden and extra resource requirements for the business.

From 1 July 2021, a supplier can now choose to account for VAT on intra-EU cross-border supplies of goods or services to final consumers in the EU One Stop Shop (OSS). OSS is an electronic portal that allows businesses to register for VAT electronically in a single Member State for all intra-EU distance and B2C supplies. They also declare and pay VAT on all supplies of goods and services in a single electronic quarterly return.

The OSS can be used by businesses established in the EU and outside the EU. If a supplier decides to register for the OSS, they must declare and pay VAT on all supplies of goods and services covered by the OSS [

13].

A taxable person, including a platform acting as a deemed supplier, whose place of business in the EU, or place of business is outside the Community but has a permanent establishment in the EU, may choose, in respect of his intra-Community distance sales and provided services made to a non-taxable person in a Member State of the Community where he is not established for business purposes, to, fulfil its tax payment and tax return obligations through the tax authority in the Community where it is established. It is important to note that VAT on services can only be declared and paid in the EU's OSS for services in the Member State where the supplier is not established. In the case of intra-Community distance sales, there is no such restriction, i.e. VAT on intra-Community distance sales can be declared and paid in all Member States, regardless of whether the supplier is established in that Member State or not [

8].

It is important to stress that the use of OSS is not an obligation but an opportunity, which ensures that taxable persons do not have to register in the Member State(s) where the supply takes place in order to fulfil their tax payment and declaration obligations arising from specific transactions carried out in another Member State(s) of the Community, but can fulfil these obligations in one Member State using the OSS system.

However, even if the threshold of EUR 10 000 is not reached, a taxable person may opt to pay tax in the Member State of consumption on intra-Community distance supplies or on services supplied at a distance (to which they can use the OSS), however, in that case, he may not depart from his choice until the end of the second year following the year of his choice [

8]. The applicability of the OSS system facilitates the administration of tax obligations for businesses. However, because of the many exceptions and the wide range of activities, there will still be many businesses that will have to register for VAT in all Member States concerned in order to meet their tax obligations.

3.5. The importance of tax harmonization and its current problems for e-commerce businesses

Several parameters of cross-border e-commerce can affect costs, including customs duties and taxes, VAT and other local taxes. All these factors affect the competitiveness of the prices set by the firm in the foreign markets targeted [

14]. One major problem for online sales is the different VAT rates applied in foreign countries. To sell their products in each market, companies need to register with the tax authorities of the foreign countries targeted [

15]. The exceptions and rules for using the OSS system were discussed in the previous chapter. While administrative processes can be simplified using the OSS, it is still essential to be familiar with the tax rules of the Member States that are considered to be the destination for the sale.

Potentially negative factors affecting online export performance related to cross-border e-commerce include coping with foreign markets and technical difficulties. Financial complexity creates additional challenges, as dealing with foreign taxation is often too complicated and/or too costly. Organizational factors also play a crucial role in how companies perceive the severity of these obstacles. The challenges and difficulties associated with cross-border e-commerce are perceived more intensively by exporters from countries with inadequate digital infrastructure. Resource- poor firms are also more likely to encounter barriers to cross-border e-commerce, which increases their trade costs, administrative burdens and operational problems [

16]. In addition to BigTech companies and e-commerce giants, many small and start-up businesses are also involved in online sales. These firms may face barriers to entry into additional markets for reasons of economies of scale, exacerbated by international tax tasks, without automation of which there is little chance of competitiveness. Póta and Becsky-Nagy [

1] point out that FinTech for example is international by nature, so because of its ability to conduct its activities across national borders and within and outside of economic regions, legislators must apply common norms and principles with respect to domestic features, to ensure equal rights for everyone. The lack of unambiguous rules can restrict the willingness to use innovations and to invest.

Several hypotheses try to explain why different VAT systems cause distortions in commercial activity; however, there is currently little empirical evidence to support these claims. It is certain that the effective and sustainable functioning of the single market is a necessary precondition for the success of the EU, and a harmonized VAT system is an essential element of this. The single market must ensure not only the free and competitive movement of goods, capital, persons and services between Member States, but also VAT revenue. There is a relatively high degree of harmonization in terms of the extent to which differences between tax systems and VAT regimes have been eliminated. However, given the social, economic and geopolitical specificities of the various states and the need for fiscal sovereignty, it is not yet possible to speak of full harmonization, leaving Member States free to define their own tax systems. It can be stated that harmonization remains a necessary condition for the sustainable functioning of the European market [

17].

4. Discussion

The cross-border tax and legal environment can vary between countries, regions or even cities, with different tax rates, deadlines, and tax rules in different areas. Cross-border laws are complex and change frequently, but a business also must deal with differences between countries. The sale of goods and services in the digital space can take place in a number of scenarios, depending on where the seller and buyer are physically located, and whether they use a third-party intermediary service or transport. Tax issues can be further complicated by whether the buyer and seller are taxable persons. Based on these scenarios, the following sales models have been distinguished:

- a)

In the case of a supply of goods by a non-resident seller to an intra-Community business customer (B2B product import) the business purchasing the goods is responsible for accounting for the VAT due (reverse charge). As the goods originate from outside the EU, the purchaser must declare an import of goods. Customs and import duties are payable where the product enters the Community. If this sale is made through a platform, the specific rules applicable to platforms should be considered.

- b)

If the non-Community seller dispatches the goods from its warehouse in the Community to a business customer in the Community (B2B), then the business purchasing the goods is responsible for accounting for the VAT payable (reverse charge). If the goods originate from outside the EU, the purchaser may have to declare an import of goods. If this sale is made through a platform, the specific rules applicable to platforms should be considered.

- c)

In the case of the supply of services by a seller outside the Community to a business customer in the Community (B2B service import) the recipient business is responsible for accounting for the VAT due (reverse charge). If this sale is made through a platform, the specific rules applicable to platforms should be considered.

- d)

In the case of a supply of goods to the final consumer by a non-Community supplier, the supplier is normally responsible for charging and accounting for VAT at the rate applicable in the country of the customer (or of the supply of services). Exception (from 1 July 2021) if the seller's sales fall below the distance selling threshold of EUR 10 000. If this sale is made through a platform, the specific rules applicable to platforms should be considered.

Until the threshold is exceeded, an intra-Community taxable person making an intra-Community distance supply (B2C) must charge the VAT rate under the VAT Act on the goods supplied or the services rendered (which may be provided at a distance). Above the EUR 10 000 threshold (or below the threshold if one chooses) the place of destination of the goods or the place of establishment of the non-taxable customer in relation to the use of the service (if not, the place of residence or usual place of abode) shall be charged at the rate of VAT laid down by the VAT legislation of the Member State in which the supply is made. The conversion rate for the EUR 10,000 threshold is the ECB exchange rate on 5 December 2017.

- e)

In the case of the supply of services by a seller established outside the Community to a final consumer in the Community (B2C service import), the supplier is responsible for charging and accounting for the VAT at the rate applicable in the country where the service is supplied.

- f)

in the case of supply of goods by a supplier established in the Community to a business customer in the Community (B2B), the business customer is responsible for accounting for the VAT payable using reverse charge.

- g)

For services provided by a service provider established in the Community to a business customer in the Community (B2B), the business customer is responsible for accounting for the VAT payable using reverse charge.

- h)

In the case of supply of goods to final consumers in the Community by an intra-Community supplier (B2C), the supplier is responsible for charging and accounting for VAT at the rate applicable in the buyer's country. This VAT can be reported with a single VAT registration, using One-Stop Shop, if the service provider is not registered in the country.

- i)

In the case of supply of services by an intra-Community supplier to final consumers in the Community (B2C), the supplier is responsible for charging and accounting for the VAT at the rate applicable in the country where the service is supplied.

The new regulation on platforms does not currently apply to certain cases/providers, so they can only be subject to the current "traditional" tax rules of agency services and intermediary services. According to the new provisions of the VAT directives and legislation, the following rule briefly defines the taxation of platforms, as described earlier: A taxable person who, through the use of an electronic platform (in particular a marketplace, platform, portal or other similar means) facilitates the supply of goods within the Community by a taxable person not established in the Community to a non-taxable person, shall be deemed to be both the purchaser and the seller of that product.

The obstacles related to the new regulation of VAT on platforms are the following:

- 1.

The new regulation applies only to the sale of goods, not to the provision of services, so we understand that only intermediaries engaged in the sale of goods can be considered platforms. In contrast, the regulation imposes the registration obligation on both the sale of goods and the provision of services facilitated by the platform. If a platform is defined as being engaged in the sale of products, the question arises as to whether an electronic interface that is solely engaged in the provision of services is a platform or not, i.e. whether it is subject to the tax and record-keeping rules applicable to platforms.

To put the question more concretely, if an electronic interface deals solely with the provision of services, then, for the purposes of the taxation of platforms, should it be considered as if there were two supplies of services: between the actual supplier and the platform and between the platform and the recipient of the service.

- 2.

The second problem is that, according to the rules on platforms, the platform "facilitates supplies within the Community between a taxable person not established in the Community and a non-taxable person.", so in the case of distance selling within the Community, the intermediary cannot be considered a platform. It follows from the above that the supply of services by an intra-Community taxable person to a non-taxable person is not covered by the new platform rules either.

- 3.

The EU OSS system can be used by the service intermediary interface, but only for those Member States in which it is not established. No such restriction applies to the sale of products. A taxable person, including a platform acting as a deemed supplier, who has established his business in the Community (or is established outside the Community but has a permanent establishment within the Community) may choose to pays tax and files tax return through the tax authority of the country where it is established or has a permanent establishment on his intra-Community distance sales and on his supplies of services to a non-taxable person in a Member State of the Community where he is not established for business purposes.

- 4.

It makes a difference whether the services are B2B or B2C. In the B2B case, VAT will be charged according to the place of establishment of the business using the service, while in the B2C case, the place of supply of services is the place of performance, so the VAT will be charged according to the place of supply. The exception to this is the case of events where the place of performance is the venue of the event. Platform taxation currently only applies to B2C sales of goods, not to services and B2B sales, but if the rules are extended, the rules on the place of supply of services should also be fixed.

If an electronic interface does not facilitate the sale of the products (i.e. does not set the conditions for the sale, is not involved in authorizing the charging of the amount paid to the customer or in ordering and authorizing the product), then it is not considered a platform and no tax liability arises. In this case, it may only process payments, list or advertise products by redirecting the buyer to another electronic platform offering the product for sale, without participating in the sale. In this case, the sale is made directly between the actual seller and buyer.

5. Conclusions

For cross-border e-commerce businesses in the EU, the VAT rules are extremely complex and often opaque, due to a lack of tax harmonization. Keeping track of different tax systems (some countries may apply VAT, others GST), different tax rates, amounts, deadlines, etc. can be challenging in several countries, so it is advisable to set up a compliance team. Compliance processes should be supported by modern tax technology solutions. For example, cross-border tax software allows businesses to meet the compliance requirements of different tax jurisdictions, significantly reducing the potential for tax non-compliance. It also notifies businesses of tax benefits, allowing them to optimize their compliance operations. The cross-border tax and legal environment may differ between countries, regions or even cities, with different tax rates, deadlines, and tax rules in different areas. Cross-border laws are complex and change frequently, a business also must deal with differences between countries.

The aim of the research was to explore, using a qualitative method, what harmonization efforts would make the current legislation uniform, simpler, more transparent, and easier to understand, without conflicting with the rules of any Member State. To this end, we assessed aspects of the new platform regulation introduced on 1 July 2021 and its potential for expansion through information from sales models. In the light of the results, it can be concluded that the sale of goods and the provision of services in the digital space can take place in a number of scenarios, depending on where the seller and the buyer are physically located and whether they use intermediate, third-party intermediary services or transport. Tax issues can be further complicated by whether the buyer and seller are taxable persons. The OSS system, often designed to simplify opaque tax systems/tasks, cannot currently be used for all the cases we have outlined and the rules for platforms do not cover all sales models (scenarios). In our view, the current situation is not sustainable in the long term, as it imposes unnecessary administrative burdens on individual businesses and makes their tax activities less transparent.

In the light of the results of the research, we propose that the EU regulation on platforms should be extended to cover all B2B and B2C transactions and services that are carried out through an intermediary electronic interface. Thus, the businesses concerned could fulfil their tax obligations through the OSS system based on a simplified set of rules for platforms, with a significant reduction in the expected administrative burden. The proposed harmonization would make the current legislation simpler and easier to interpret, without conflicting with the rules of any Member State. In addition, a more transparent, uniform and sustainable tax system would help to whiten the economy, generating additional tax revenue for Member States.

According to our proposal, where the electronic interface facilitates the intra-Community supply of services, the rules on the taxation of platforms would apply. When a non-established taxable person makes a supply of goods to a non-taxable person in the Community, the taxable persons facilitating the transaction are currently subject to the legislation on VAT on platforms. The purpose of the legislation was to create a tax liability for platforms under the fiction that two sales are made at the same time, one between a seller outside the Community and the platform, and one between the platform and the end user.

Following the existing logic, our proposal is as follows: The platform facilitating the provision of services within the Community does not order the service on its own behalf and resell it as an intermediated service, but the platform orders the service from the service provider on behalf of the customer. So, there is actually one sale, but using the fiction described earlier, we assume that there are two sales. The first sale is a B2B intra-Community tax-free sale (subject to the reverse charge rules), the second sale (B2C) is taxable. In this case, the taxable person is the platform operator who declares and pays the VAT. This is similar to the taxation of an intermediated service, except that the platform does not order the service on its own behalf for the benefit of the customer, but on behalf of the customer. The taxable amount is the value of the service provided by the actual service provider plus the value of the services provided by the platform, paid by the buyer to the platform as part of the gross price. This would simplify the administration of transactions of the platform, and it could simply declare and pay the tax to the relevant countries through the OSS system.

As a result of these proposed changes, we believe that the market expansion opportunities for e-commerce start-ups and smaller businesses could be increased, in addition, the VAT processes for transactions involving several Member States would become more transparent and sustainable.

Although we believe that we have added value by illustrating the current complexity of cross-border e-commerce highlighting the main challenges regarding VAT issues, we must still mention some limitations of our research. Among them, this study examines the tax issues for firms operating in the field of cross-border e-commerce, with a particular focus on VAT. Also, the scope of this study applies to 2023 in EU context, from a Hungarian perspective mainly. For these reasons, in a future study, particularly empirical research, one should extend the scope of the study to more countries in the European Union. Another interesting extension of this study could be to review the intrinsic value regulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Patrícia Becsky-Nagy; Methodology, Patrícia Becsky-Nagy; Project administration, Cserne Panka Póta; Resources, Cserne Panka Póta; Supervision, Patrícia Becsky-Nagy; Visualization, Cserne Panka Póta; Writing—original draft, Cserne Panka Póta; Writing – review & editing, Patrícia Becsky-Nagy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the University of Debrecen.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by the ÚNKP-22-23 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. This paper was supported by the PhD Excellence Scholarship from the Count István Tisza Foundation for the University of Debrecen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Póta, Cs. P.; Becsky-Nagy, P. The impact of digitalization to the financial sector. Competitio 2022, Vol. XXI. [CrossRef]

- Póta, Cs. P.; Becsky-Nagy, P. Disruptive solutions for FinTechs and their risks: Hungarian case studies. Vezetéstudomány/Budapest Management Review 2023, 54, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Taxation of the digitalized economy–Developments summary. 2022. Available online: https://tax.kpmg.us/articles/tracking-digital-services-taxes-developments.html (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Jogkövető. Ügynöki tevékenység adózása. (Taxation of agency activities). 2021. Available online: https://jogkoveto.hu/tudastar/ugynoki-tevekenyseg-adozasa (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Wolters Kluwer. 2000. évi C. törvény a számvitelről. (Act C of 2000 on Accounting). 2022. Available online: https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a0000100.tv (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- ICT Európa. A közvetített szolgáltatás legfontosabb szabályai. (The main rules of intermediated services). 2019. Available online: https://icteuropa.hu/blog/699-a-kozvetitett-szolgaltatas-legfontosabb-szabalyai (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Simić, S. Regulation and Taxation of Digital Services in Accordance with the Initiatives of the European Union. Financial Law Review 2021, 24, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAV. 98. információs füzet—A nem uniós és uniós egyablakos rendszerre, valamint a platformokra vonatkozó áfaszabályok. (Information leaflet 98 - VAT rules for non-EU and EU one-stop shops and platforms). 2022. Available online: https://nav.gov.hu/ugyfeliranytu/nezzen-utana/inf_fuz/2022 (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 282/2011 of 15 March 2011 laying down implementing measures for Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of value added tax. Article 54b.

- Vertex. Major EU VAT changes for digital platforms facilitating sales of low value goods. 2021. Available online: https://www.vertexinc.com/resources/resource-library/major-eu-vat-changes-digital-platforms-facilitating-sales-low-value (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Taxdoo. One-Stop-Shop (OSS) EU VAT for E-Commerce. 2022. Available online: https://www.taxdoo.com/en/blog/one-stop-shop-vat-e-commerce-package-eu-6663/ (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Marosa. Marosa. Explanatory notes on OSS? 2022. Available online: https://marosavat.com/explanatory-notes-on-oss/ (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- EY. Worldwide VAT, GST and Sales Tax Guide. 2022. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/tax-guides/worldwide-vat-gst-and-sales-tax-guide (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Guillén, M. F. What is the best global strategy for the internet? Business Horizons 2002, 45, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavdic, M.; Gregory, G. Integrating e-commerce into existing export marketing theories: A contingency model. Marketing Theory 2005, 5, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardsen, J.; Marinova, S.; Leonidou, L.C. et al. Organizational Influences and Performance Impact of Cross-Border E-Commerce Barriers: The Moderating Role of Home Country Digital Infrastructure and Foreign Market Internet Penetration. Manag. Int. Rev. 2023, 63, 433–467. [CrossRef]

- Beshi, S.; Peci, B. The importance of value-added tax harmonization in the European Union single market. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2023, 4, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of VAT.

- Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 282/2011 of 15 March 2011 laying down implementing measures for Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of VAT.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).