Submitted:

24 February 2024

Posted:

26 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

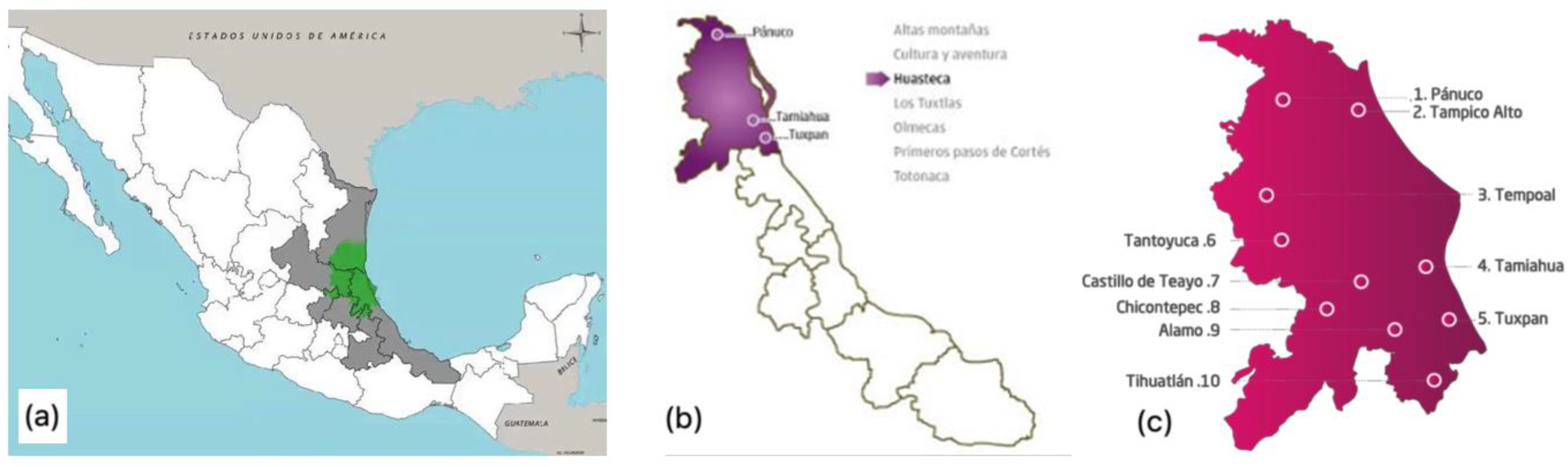

2.1. Description of the Experimental Site

2.1.1.

2.1.2. Evaluated Germplasm and Experiment Design

2.1.3. Experiment Site and Sowing

2.1.4. Sampling and Cutting Frequency (CF)

2.1.5. Evaluated Variables

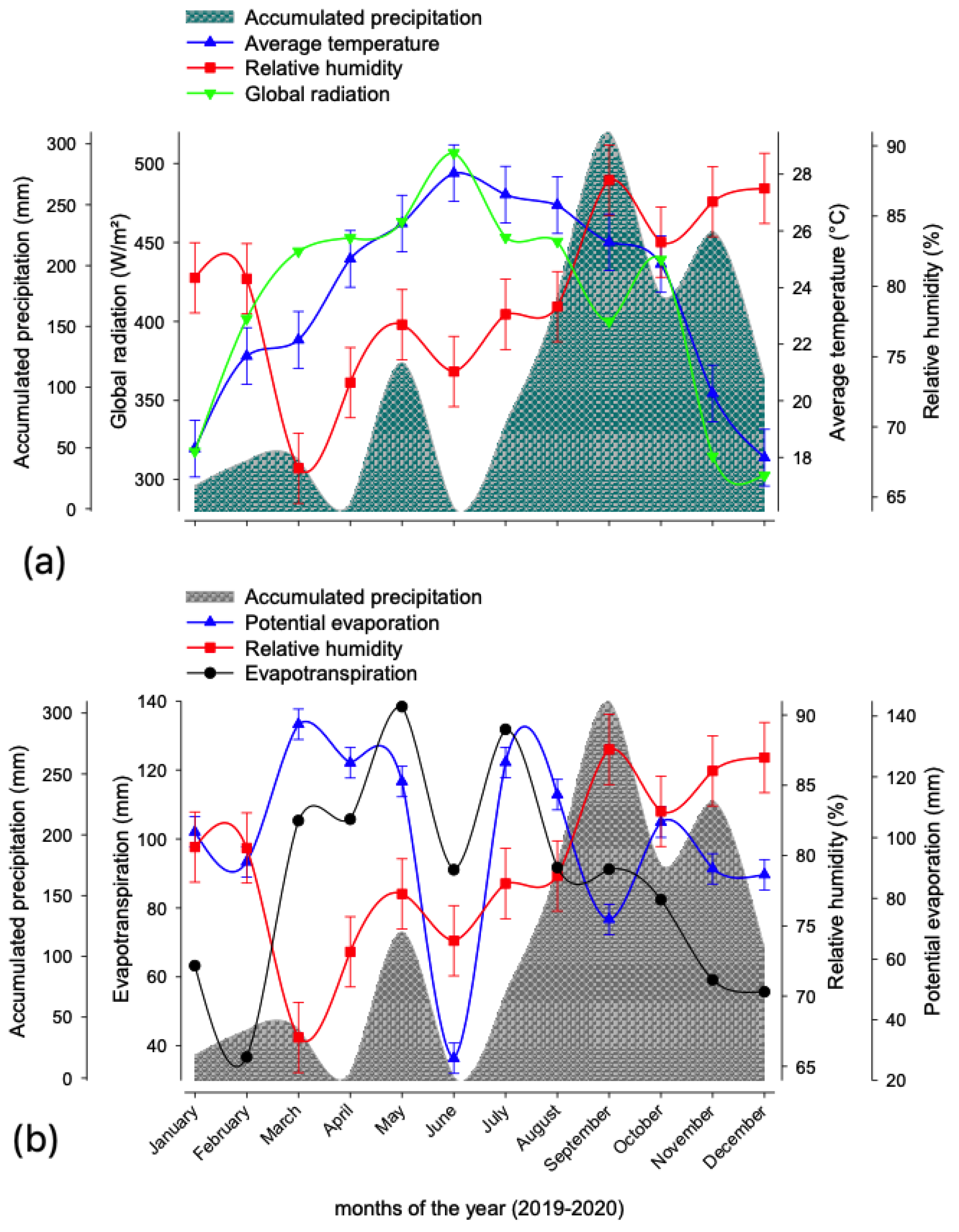

2.1.6. Climate Variables

2.1.7. Statistical Analysis

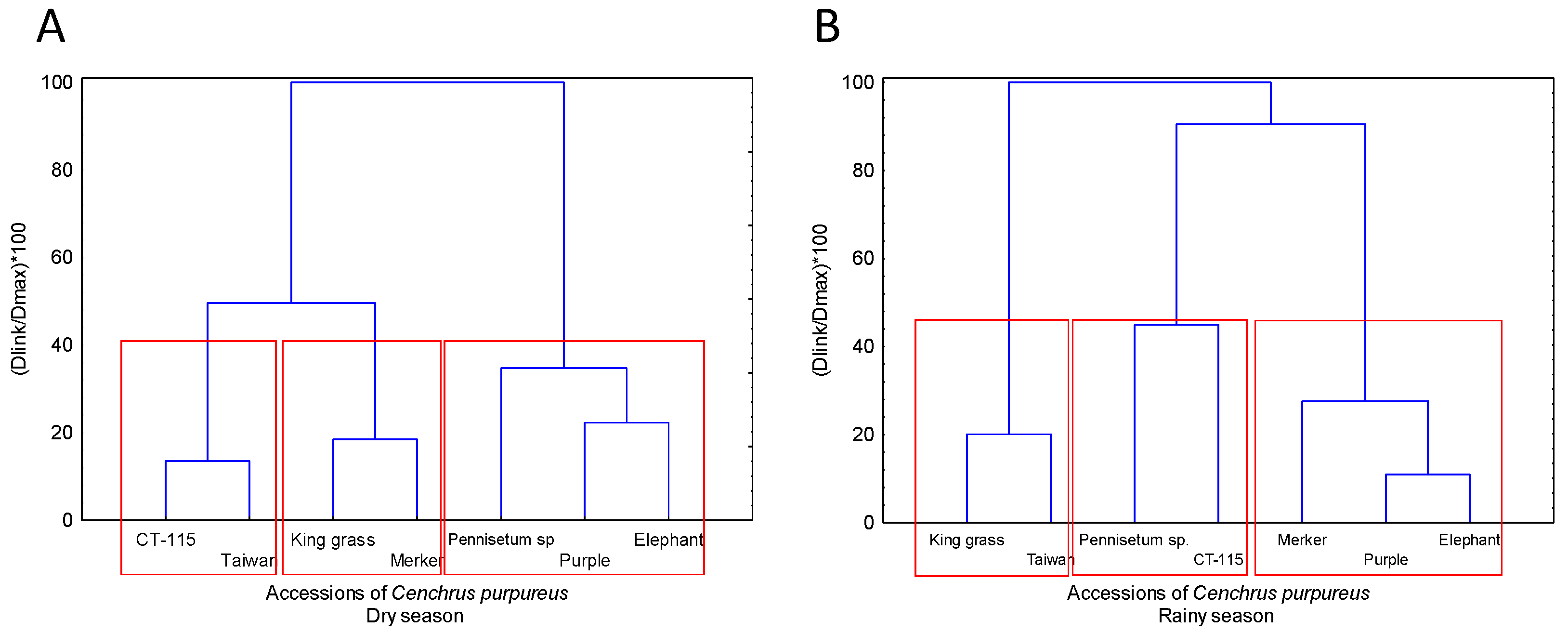

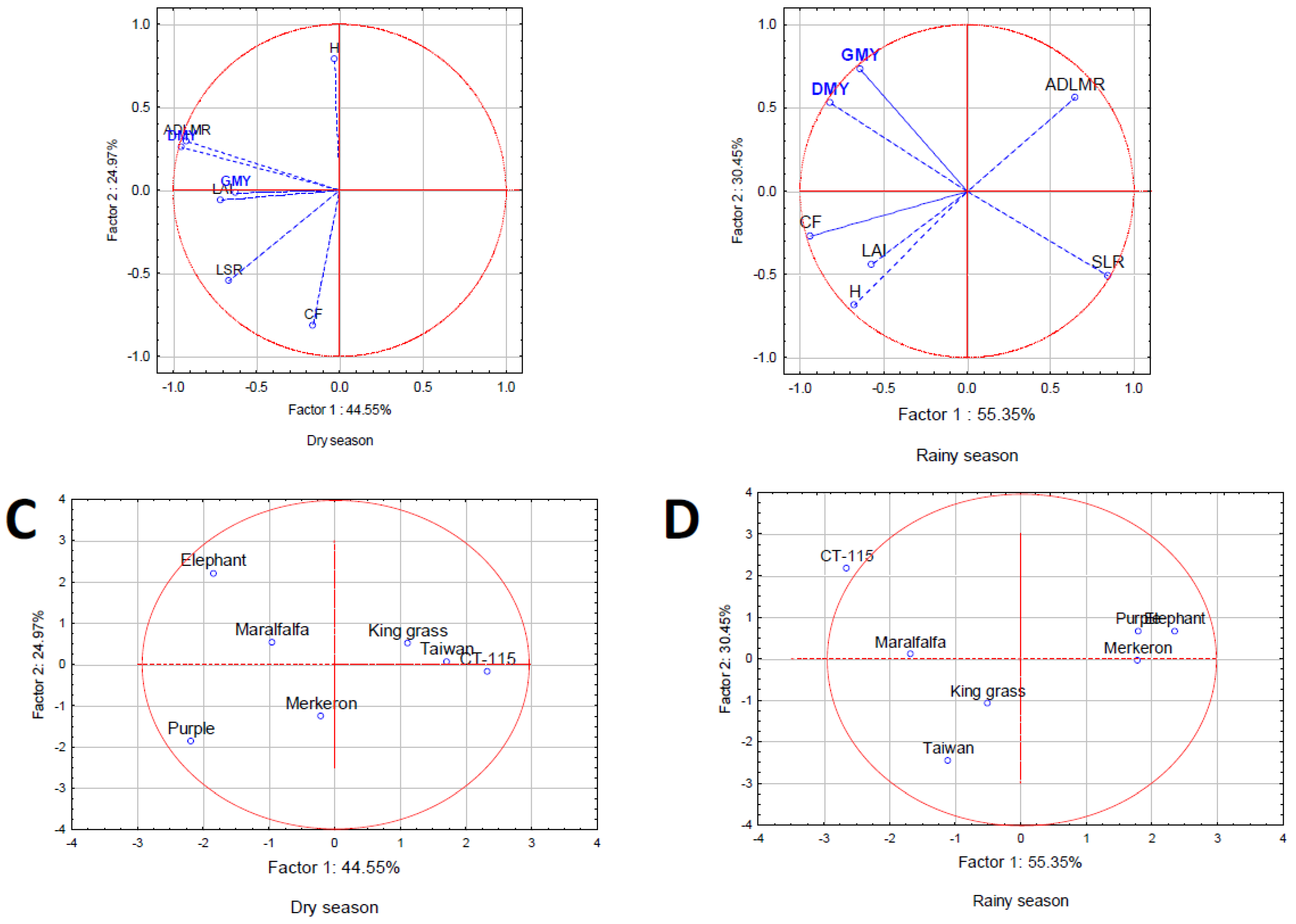

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bengtsson, J.; Bullock, J.M.; Egoh, B.; Everson, C.; Everson, T.; O’Connor, T.; O’Farreli, P.J,; Smith, H.G.; Lindborg, R. Grasslands-more important for ecosystem services than you might think. 2019.Ecosphere 10. [CrossRef]

- Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Global Food Security. 2017. 14:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.I.; Falcucci, A.; Teillard, F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Science. 2015. 109:2–12. [CrossRef]

- FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura). El Estado Mundial de la Agricultura y la Alimentación. Cambio Climático, Agricultura y Seguridad Alimentaria. Roma. 2016. pp. 214. https://www.fao.org/3/i6030s/i6030s.pdf.

- CEDRSSA (Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberanía Alimentaria). Política pecuaria y ganadería sostenible en México. 2020. https://bit.ly/3pzIe9n.

- SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera). 2021. Población ganadera. https://bit.ly/3KtARsn.

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado de Veracruz. Programa Sectorial Alimentando a Veracruz 2019-2024. 2019. [Online]. México: Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz. [Accessed 2022 abril 28] URL Disponible en: http://www.veracruz.gob.mx/finanzas/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/11/Alimentando-veracruz.pdf.

- Corona, L. El metano y la ganadería bovina en México: ¿Parte de la solución y no del problema?. Agro Productividad. 2018. 11:46-51. https://bit.ly/3hz7ybf.

- Hennessy, D.; Shalloo, L.; Van Zanten, H.; Schop, M. ; De Boer. I. The net contribution of livestock to the supply of human edible protein: The case of Ireland. The Journal of Agricultural Science. 2021. 159:463-471. [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Andueza, D.; Niderkorn, V.; Lüscher, A.; Porqueddu, C.; Picon-Cochard, C. A meta-analysis of climate change effects on forage quality in grasslands: specificities of mountain and Mediterranean areas. Grass and Forage Science. 2015. 70:239–254. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez.,R.J.L.; Zambrano, B.D.A.; Campuzano, J.; Verdecia, A.D.M.; Chacón, M.E.; Arceo, B.Y.; Labrada, C.J.; Uvidia, C.H. El clima y su influencia sobre la producción de pastos. Revista Electrónica de Veterinaria. 2017. 18(6), pp. 1-12. https://bit.ly/3ICNNvq.

- Rojas-Downing, M.M.; Pouyan, N.A.; Harrigan, T.; Woznicki. S.A. Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Climate Change Management. 2017. 17:145-163. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Siles, P.; Eash, L.; Van Der Hoek, R.; Kearney, S.P.; Smukler, S.M.; Fonte, S.J. Participatory evaluation of improved grasses and forage legumes for smallholder livestock production in central America. Experimental Agriculture. 2019. 55:776–792. [CrossRef]

- Olivera-Castro, Y.; Castañeda-Pimienta, L.; Toral-Pérez. O.C. Morphobotanical characterization of Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone plants from a national collection. Pastos y Forrajes. 2017. 40:171–174.

- Dos Reis, G.B.; Mesquita, A.T.; Torres, G.A.; Andrade-Vieira, L.F.; Vander. P.A.; Davide, L.C. Genomic homeology between Pennisetum purpureum and Pennisetum glaucum (Poaceae). Comparative Cytogenetics. 2014. 8:199-209. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Méndez-Martínez, Y.; Luna-Murillo, R.A.; Espinosa-Coronel, A.L.; Ledea-Rodríguez, J.L. Evaluación de la fertilización en respuestas morfo agronómicas de variedades de Cenchrus purpureus en diferentes edades de rebrote. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. 2021. 24. https://bit.ly/3szHlzF.

- Negawo, A.T.; Teshome, A.; Kumar, A.; Hanson, J.; Jones, C.S. Opportunities for napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum) improvement using molecular genetics. Agronomy. 2017. 7:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G.; Simons, S.A.; Hillocks, R.J. Pests, diseases and weeds of Napier grass, Pennisetum purpureum: A review. International Journal of Pest Management. 2002. 48:39–48. https://bit.ly/3vbhz5D.

- Daniel, J.L.P.; Bernardes, T.F.; Jobim, C.C.; Schmidt, P.; Nussio, L.G. Production and utilization of silages in tropical areas with focus on Brazil. Grass and Forage Science. 2019. 74:188-200. [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, K.; Samireddypalle, A. Impact of Climate Change on Forage Availability for Livestock. In: V. Sejian et al, ed. 2015. Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation, Springer. India. 2015. p. 97–112. [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua [CONAGUA]. (2022, 19 de junio). Monitor de sequias en México. https://bit.ly/3v9LHhO.

- SIEGVER (Sistema de Información Estadística y Geográfica del estado de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave). 2020. Cuadernillos municipales 2020. [pdf] Veracruz: Gobierno del Estado. https://bit.ly/348PdyJ.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). Biblioteca Digital. México. 2021. Disponible en https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapas/?ag=30.

- Rojas, G.A.R.; Hernández, G.A.; Quero, C.A.R.; Guerrero, R.J.D.; Ayala, W.; Zaragoza, R.J.L.; Trejo, L.C. Persistencia de Dactylis glomerata L. solo y asociado con Lolium perenne L. y Trifolium repens L. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2016. 7(4), pp. 885-895. https://bit.ly/3II09lS.

- Herrera, G.R.S. Algunos aspectos que pueden influir en el rigor y veracidad del mustreo de pastos y forrajes. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria. 2014. 18:7-26. http://ww.ucol.mx/revaia/pdf/2014/mayo/1.pdf.

- Habte, E.; Muktar, M.S.; Abdena, A.; Hanson, J.; Sartie, A.M.; Negawo, A.T.; Machado, J.C.; da Silva, F.J. Jones, S.C. Forage Performance and Detection of Marker Trait Associations with Potential for Napier Grass (Cenchrus purpureus) Improvement. Agronomy. 2020. 10:542. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G.R.S.; Fortes, G.D.; García, M.M.; Cruz, S.A.M.; Romero, U.A. Determinación del índice de área foliar de Cenchrus purpureus vc. CT-115 mediante medidas en la cuarta hoja completamente abierta. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria. 2018. 22:7–24. http://ww.ucol.mx/revaia/anteriores.php?id=106.

- Pacheco, J.; Domínguez, M.I.; Lamadrid, J.O. Lluvia y evapotranspiración de referencia en cuatro puntos representativos de la provincia de Villa Clara, Cuba. Centro Agrícola. 2006. 33(4), pp. 67-71.

- Llanes-Cárdenas, O.; Norzagaray-Campos, M.; Muñoz-Sevilla, N.P. Determinación de la evapotranspiración potencial (ETP) y de referencia (ETO) como indicador del balance hídrico del corazón agrícola de México. Juyyaania. 2014. 2(1), pp.119-129.

- Ray, J.; Herrera, R.S; Benítez, D.; Días, D.; Arias, R. Multivariate analysis of the agronomic performance and forage quality of new clones of Pennisetum purpureum drought tolerant in Valle del Cauto, Cuba. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2016. 50:639-648. http://cjascience.com/index.php/CJAS/article/view/668.

- Sinche, M.; Kannan, B.; Paudel, D.; Corsato, C.; Lopez, Y.; Wang, J.; Altpeter, F. Development and characterization of a Naiper grass (Cenchrus purpureus) mapping population for flowering-time and biomass-related traits reveal individuals with exceptional potential and hybrid vigor. GCB Bioenergy. 2021. 13:1561-1575. [CrossRef]

- Maranhão, T.D.; Cândido, M.J.D.; Lopes, M.N.; Pompeu, R.C.F.F.; Carneiro, M.S. de S.; Furtado, R.N.; Silva, R.R. da; Silveira, F.G.A. da. Biomass components of Pennisetum purpureum cv. Roxo managed at different growth ages and seasons. Revista Brasileira de Saúde e Produção Animal. 2018. 19:11–22. [CrossRef]

- Vinay-Vadillo, J.C.; Herrera-Sotero, M.Y.; Juárez-Jiménez, A.; Montero-Lagunes, M.; Villegas-Aparicio, Y.; Enriquez-Quiroz, J.F.; Bolaños-Aguilar, E.D.; Mendoza-Pedroza, S.I. Crecimiento y macronutrientes en Cenchrus purpureus cv. Taiwán con y sin fertilización en Veracruz. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios. 2021. 8(II). [CrossRef]

- Nava-Cabello, J.J.; Gutiérrez-Ornelas, E.; Zavala-García, F.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Treviño, J.E.; Bernal-Barragán, H.; Herrera, G.R.S. Establecimiento del pasto ‘CT- 115’ (Pennisetum purpureum) en una zona semiárida del noreste de México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana. 2013. 36:239–244. https://bit.ly/3tlvMLH.

- Ledea-Rodríguez, J.L.; La O-León, O.; Verdecia-Acosta. D.; Benítez-Jiménez, D.G.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G. Composición química-nutricional de rebrotes de Cenchrus purpureus (schumach.) morrone durante la estación lluviosa. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. 2021. 24.

- Cruz, T.J.M.; Ray, R.J.V.; Ledea, R.J.L.; Arias, P.R.C. Establecimiento de nuevas variedades de Cenchrus purpureus en un ecosistema frágil del Valle del Cauto, Granma. Revista Producción Animal. 2017. 29: 29–35. https://bit.ly/345K3DD.

- Arias, R.C.; Ledea, J.L.; Benitez, D.G.; Ray, J.V.; Ramírez, R.J.L. Performance of new varieties of Cenchrus purpureus, tolerant to drought, during dry period. Cuban Journal of Agriculture Science. 2018. 52. https://bit.ly/3pt1d5B.

- Tulu, A.; Diribsa, M.; Temesgen, W. Dry matter yields and quality parameters of ten Naiper grass (Cencherus purpureus) genotypes at three locations in western Oromia, Ethiopia. Tropical Grassland. 2021. 9:43-51. [CrossRef]

- Ledea-Rodríguez, J.L.; Ray-Ramírez, J.V.; Arias-Pérez, R.C.; Cruz-Tejeda, J.M.; Rosell-Alonso, G.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J. Comportamiento agronómico y productivo de nuevas variedades de Cenchrus purpureus tolerantes a la sequía. Agronomía Mesoamericana. 2018. 29:343-362. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Quintana, L.J.; Rivera-Espinoza, R.; González-Cañizares, P.J.; De la Rosa-Capote, J.J.; Arteaga-Roduigues, O.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Efecto del abono verde de Canavalia ensiformis (L) micorrizada en el cultivo sucesor Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone Cuba CT-169. Pastos y Forrajes. 2019. 42:277-284. https://bit.ly/3vtmhg6.

- Uvidia-Cabadina, H.A.; Ramírez-De la Rivera, J.L.; de Decker, M.; Torres, B.; Samaniego-Guzmán, E.O.; Ortega-Tenezaca, D.B.; Reyes-Silva, D.F.; Uvidis, A.L.A. Influence of age and climate in the production of Cenchrus purpureus in the Ecuadorian Amazon Region. Tropical and subtropical Agroecosistems. 2018. 21:95-100. https://bit.ly/3HEosQq.

- Araujo, L.C.; Santos, P.M.; Rodríguez, R.; Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Oliveira, P.P.A.; Cruz, P.G. Simulating Guineagrass production: empirical and mechanistic approaches. Agronomy Journal. 2013. 105: 61–69. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.S.; Santos, P.M.; Pezzopane, J.R.M.; de Araujo, L.C.; Pedreira, B.C.; Pedreira, C.G.S.; Marin, F.R.; Lara, M.A.S. Simulating tropical forage growth and biomass accumulation: an overview of model development and application. Grass and Forage Science. 2015. 71:54–65. [CrossRef]

| Accession | Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | ADLMR (kg/ha/day) | LSR | H (m) | CF (Days) | |

| Elephant | 14.71b | 202.44ab | 0.83a | 1.85b | 63.00b |

| Merkeron | 20.30ab | 220.02a | 0.88a | 2.06ab | 62.50b |

| Purpule | 16.59b | 200.72ab | 0.85a | 1.90b | 62.50b |

| Taiwan | 27.11a | 161.95b | 0.82a | 2.28a | 83.00a |

| King grass | 15.99b | 154.07b | 0.78a | 2.16ab | 83.00a |

| CT-115 | 21.15ab | 189.82ab | 0.58b | 2.05ab | 83.00a |

| Maralfalfa | 20.92ab | 170.04ab | 0.70ab | 2.15ab | 83.00a |

| s.e. | 3.53 | 20.35 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 4.13 |

| Accession | Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | ADLMR (kg/ha/day) | LSR | H (m) | CF (Days) | |

| Elephant | 19.12a | 228.51a | 0.93b | 1.94a | 79.00e |

| Merkeron | 17.81ab | 108.84bc | 0.91b | 1.79ab | 104.50a |

| Purpule | 17.82ab | 198.68a | 1.22a | 1.70b | 98.00ab |

| Taiwan | 15.35ab | 79.52c | 0.92b | 1.92a | 94.00cb |

| King grass | 11.46ab | 110.97bc | 0.89b | 1.84ab | 85.50cde |

| CT-115 | 9.27b | 91.02c | 0.86b | 1.72b | 84.00de |

| Maralfalfa | 12.35ab | 187.45ab | 0.93b | 1.86ab | 92.50bcd |

| s.e. | 3.15 | 30.56 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 3.34 |

| Accession | Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | ADLMR (kg/ha/day) | LSR | H (m) | CF (Days) | |

| Elephant grass | 16.91a | 215.47a | 0.88ab | 1.89a | 71.0b |

| Merkeron grass | 10.06a | 164.42ab | 0.89ab | 1.92a | 83.5ab |

| Purple grass | 17.21a | 199.70ab | 1.03a | 1.80a | 80.2ab |

| Taiwan | 21.26a | 120.73b | 0.87ab | 2.09a | 88.5a |

| King grass | 13.73a | 132.51b | 0.83b | 2.00a | 84.2ab |

| CT-115 | 15.21a | 140.42ab | 0.72b | 1.88a | 83.5ab |

| Maralfalfa | 16.64a | 178.74ab | 0.81b | 2.00a | 83.5ab |

| Standard error | 2.41 | 19.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 3.2 |

| Season | |||||

| Rainy | 19.54a | 185.58a | 0.78b | 2.06a | 74.2b |

| Dry | 14.74b | 143.56b | 0.95a | 1.82b | 91.0a |

| s.e. | 1.29 | 10.20 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 1.7 |

| Accession | Rainy season | Dry season | Annual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMY (t/ha) |

DMY (t/ha) |

GMY (t/ha) |

DMY (t/ha) |

GMY (t/ha) |

DMY (t/ha) |

DM (%) |

|

| Elephant grass | 261.31a | 54.39a | 155.18abc | 80.09b | 416.50ab | 134.49a | 34.1a |

| Merkeron grass | 269.78a | 55.60a | 179.11a | 46.71a | 448.89ab | 102.31ab | 24.2b |

| Purple grass | 264.66a | 61.65ab | 153.46ab | 69.30b | 418.13ab | 130.95a | 32.7a |

| Taiwan | 252.66a | 60.05ab | 104.96c | 29.21a | 357.62a | 89.27b | 27.5ab |

| King grass | 259.79a | 61.32ab | 156.66ab | 41.11a | 416.46ab | 102.44ab | 26.3ab |

| CT-115 | 321.14a | 79.81b | 120.01bc | 32.20a | 441.16ab | 112.01ab | 27.2ab |

| Maralfalfa | 295.95a | 67.03ab | 190.57a | 67.37b | 486.52b | 134.41a | 30.0ab |

| s.e. | 3.15 | 30.56 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 3.34 | ||

| Accession | Variable | |

|---|---|---|

| GMY (t/ha) |

DMY (t/ha) |

|

| Elephant | 208.25ab | 67.24a |

| Merkeron | 224.44a | 51.15ab |

| Purpule | 209.06ab | 65.47a |

| Taiwan | 178.81b | 44.63b |

| King grass | 208.23ab | 51.22ab |

| CT-115 | 220.58ab | 56.00ab |

| Maralfalfa | 243.26a | 67.20a |

| s.e. | 15.01 | 6.19 |

| Season | ||

| Rainy | 275.04a | 62.84a |

| Dry | 151.42b | 52.28b |

| s.e. | 8.02 | 3.31 |

| Variable | r | r2 | a | SE (a) | P value (a) | b | s.e. (b) | P value (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | 0.572 | 0.328 | 14.982 | 1.888 | 0.001 | 0.797 | 0.097 | 0.001 |

| HI | 0.192 | 0.037 | 12.826 | 6.743 | 0.059 | 8.218 | 3.580 | 0.023 |

| LSR | 0.262 | 0.069 | 44.658 | 5.333 | 0.001 | -19.545 | 6.116 | 0.002 |

| DLMAR | 0.884 | 0.782 | 3.967 | 1.227 | 0.002 | 0.153 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| GMY | 0.147 | 0.022 | 26.466 | 1.525 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.083 |

| Variable Y = | a + | b1 + | b2 + | b3 + | b4 + | c | r | r2a | p | MSE | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMY | -27.2 | 0.10 | -33.01 | 2.12 | 3.15 | 34.68 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 1202.92 | F |

| p value | 0.84 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| DMY | 11.08 | - | -1.50 | 0.15 | - | 14.33 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 205.45 | F |

| p value | 0.50 | - | 0.29 | 0.06 | - | ||||||

| LAI | 23.39 | 0.02 | -2.50 | 0.16 | - | 10.19 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 103.95 | F |

| p value | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.01 | - | ||||||

| H | 3.64 | 0.00 | -0.28 | 0.01 | - | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.06 | F |

| p value | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | ||||||

| LSR | 2.90 | - | - | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.02 | B |

| p value | 0.01 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| ADLMR | 80.19 | - | -16.99 | 1.45 | - | 80.36 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 6458.51 | F |

| p value | 0.39 | - | 0.036 | 0.01 | - |

| Variable | Rainy season | Dry season | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | p value | G1 | G2 | G3 | p value | |

| LAI | 17.2 ± 2.84 | 21 ± 0.16 | 21.5 ± 7.86 | 0.532 | 14.6 ± 4.49 | 16.4 ± 3.59 | 12.3 ± 4.29 | 0.577 |

| ADLMR | 207.7 ± 10.6 | 179.9 ± 13.9 | 158 ± 5.5 | 0.017 | 109.9 ± 1.5 | 204.8 ± 21.2 | 85.2 ± 8.13 | 0.002 |

| LSR | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 0.6 ± 0.08 | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 0.020 | 0.9 ± 0.01 | 1 ± 0.16 | 0.8 ± 0.04 | 0.437 |

| H | 1.9 ± 0.10 | 2.1 ± 0.07 | 2.2 ± 0.08 | 0.071 | 1.8 ± 0.03 | 1.8 ± 0.12 | 1.8 ± 0.14 | 0.982 |

| CF | 62.6 ± 0.28 | 83 ± 0.00 | 83 ± 0.00 | 0.001 | 95 ± 13.43 | 89.8 ± 9.77 | 89 ± 7.07 | 0.820 |

| GMY | 265.2 ± 4.2 | 308.5 ± 17.8 | 256.2 ± 5.0 | 0.011 | 167.8 ± 15.8 | 166.4 ± 20.9 | 112.4 ± 10.6 | 0.051 |

| DMY | 57.2 ± 3.88 | 73.4 ± 9.03 | 60.6 ± 0.89 | 0.065 | 43.9 ± 3.95 | 72.2 ± 6.85 | 30.7 ± 2.11 | 0.002 |

| Accesions | King grass | Maralfalfa | Purple | King grass | Maralfalfa | CT-115 | ||

| Merkeron | CT-115 | Merkeron | Merkeron | Purplue | Taiwan | |||

| Elephant | Elephant | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).