Submitted:

22 February 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

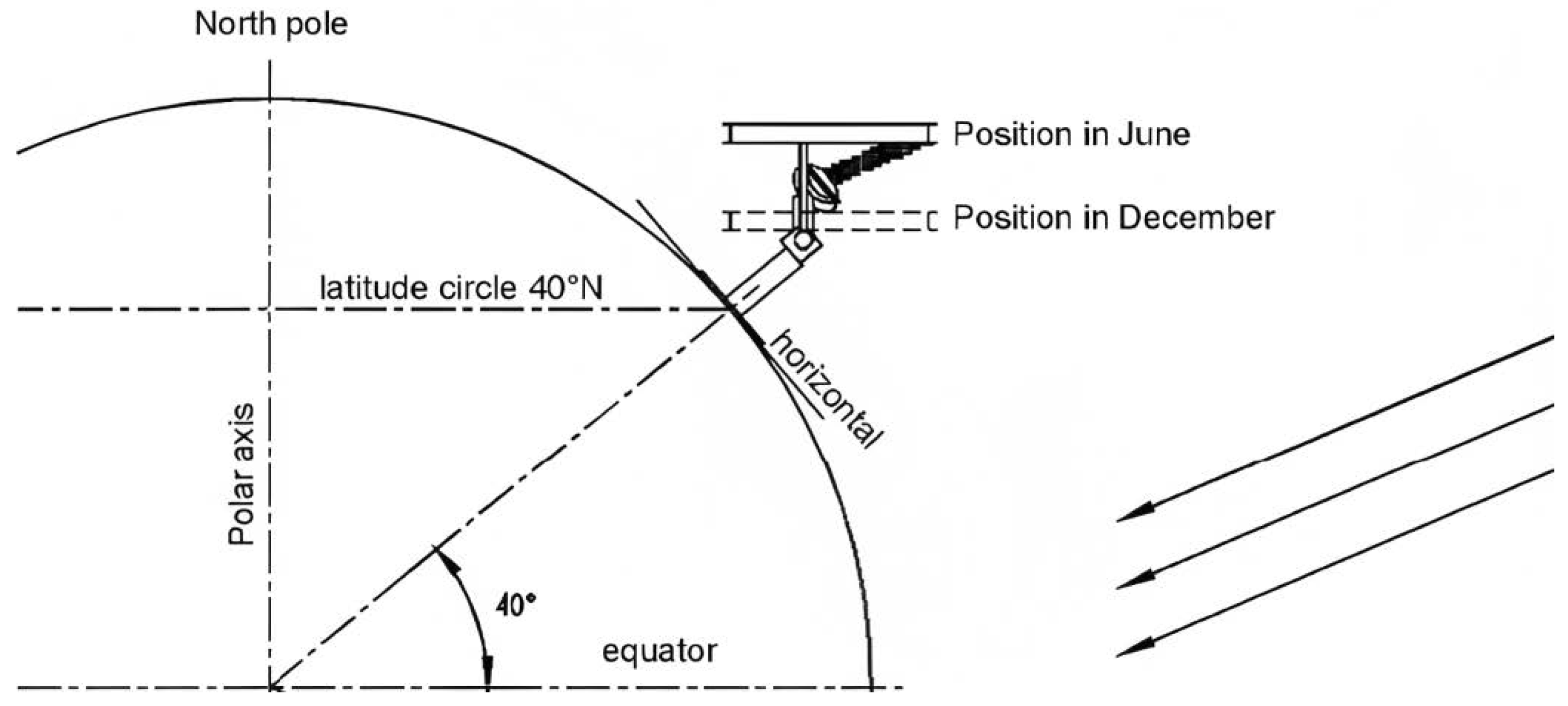

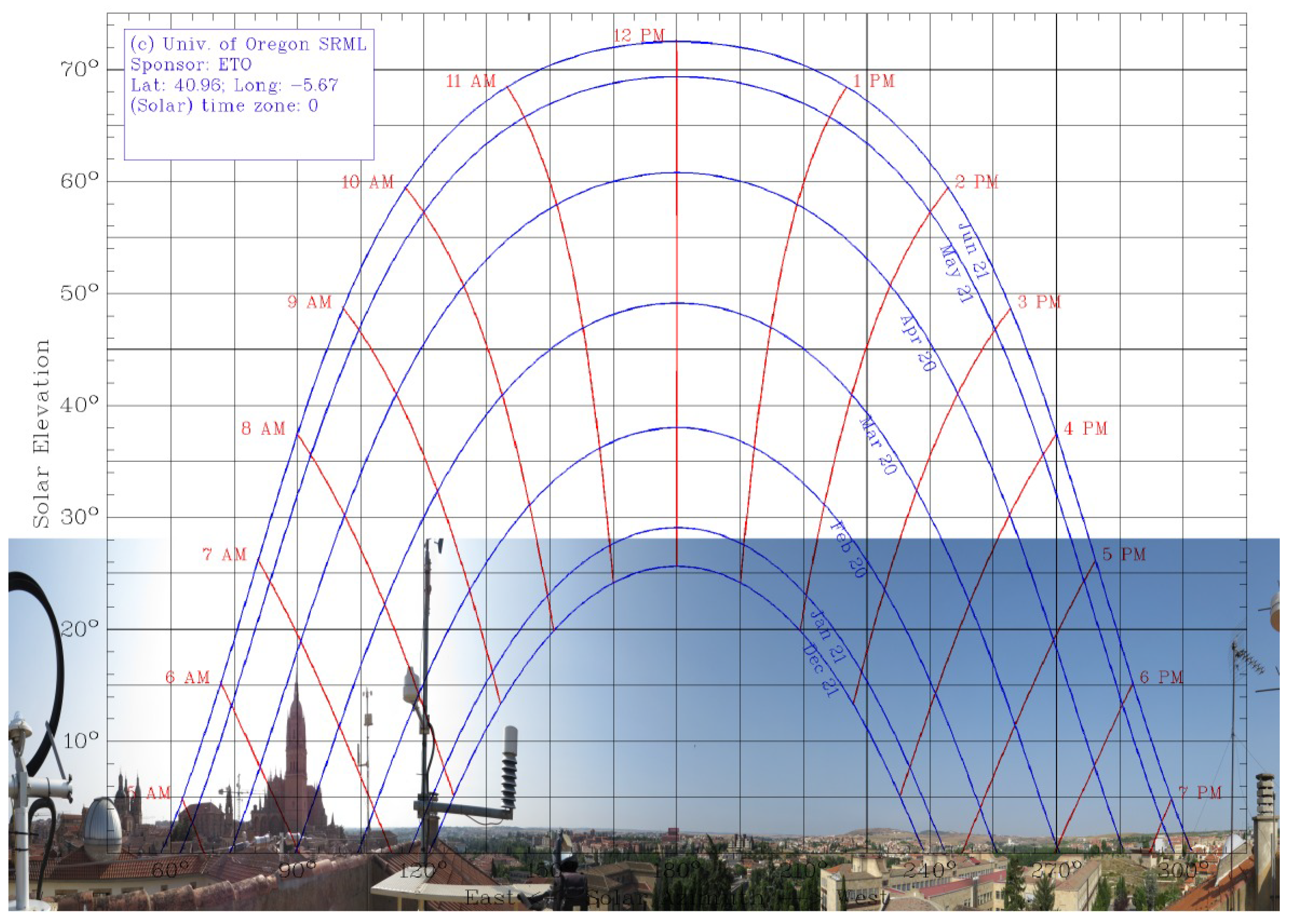

2.1. Solar irradiance

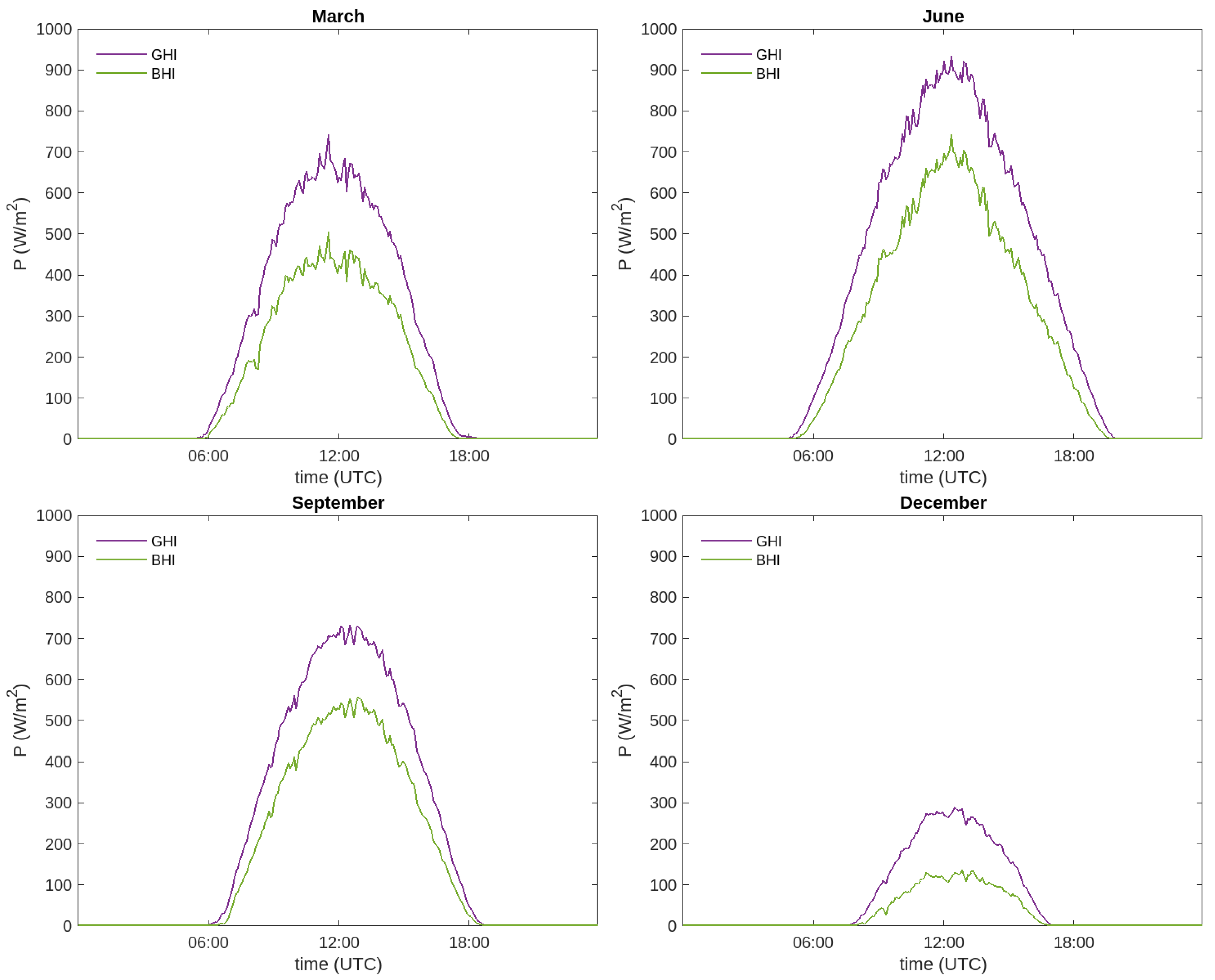

- Diffuse Horizontal Irradiance, : This is the solar irradiance collected on a horizontal surface from atmospheric scattering of light, excluding circumsolar radiation.

- Direct Normal Irradiance, : It is the component of solar irradiance collected on a surface perpendicular to the Sun’s rays. The horizontal diffuse component, , is neglected here. On clear days, this component is much larger than the diffuse component, while on days with high cloud cover, it is practically zero. As it is measured over the Earth’s surface, its values depend highly on atmospheric conditions and the time of the year.

- Global Horizontal Irradiance, : This is the sum of all irradiance components collected over a horizontal surface. This includes the direct and diffuse components, as well as the reflected components, which are generally neglected because of their low value. The can be calculated from the following expression:where is the solar altitude angle, i.e, the complementary of the zenith angle of the Sun, is the horizontal diffuse component and is the normal component.

- Beam Horizontal Irradiance, : It is the direct horizontal component of the irradiance, i.e., the direct irradiance on a plane perpendicular to the vertical of the site. It can be obtained as:

2.2. The MAPSol model

2.2.1. Clear-sky beam irradiance model

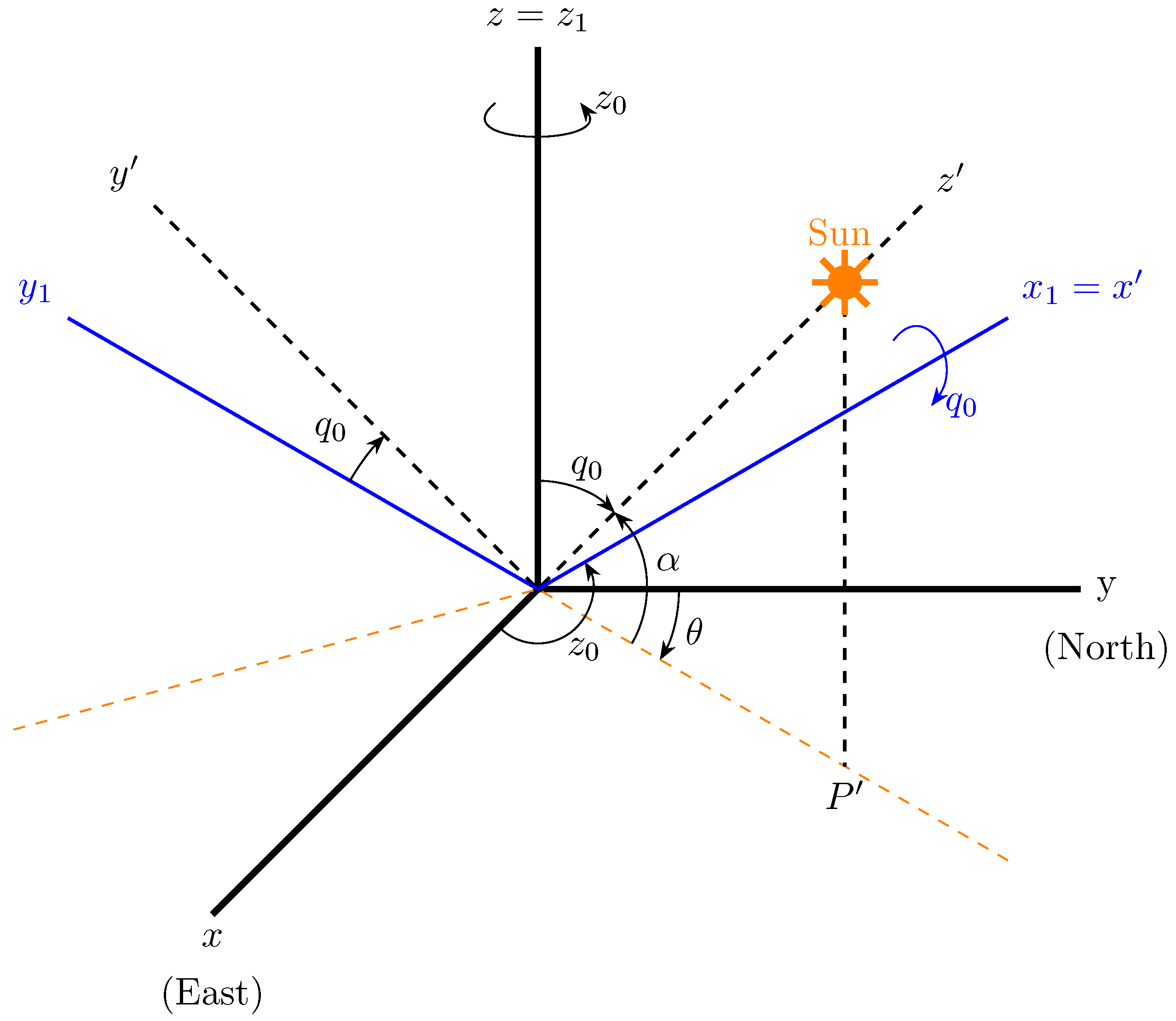

2.2.2. Shadow detection

- In the absence of self-shadowed triangles (those facing away from the Sun), the entire mesh is illuminated, and no shadows are present.

- Only triangles oriented away from the Sun are capable of casting shadows. These are referred to as potential 1 triangles [31].

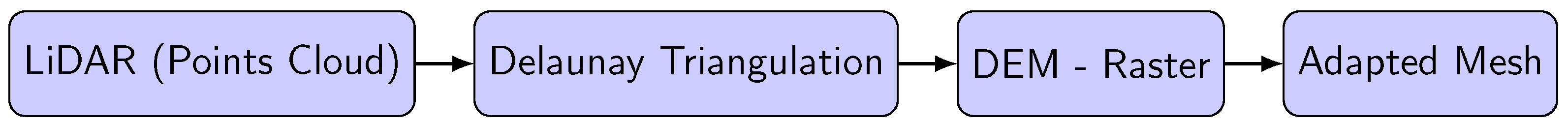

2.3. High-resolution DEM

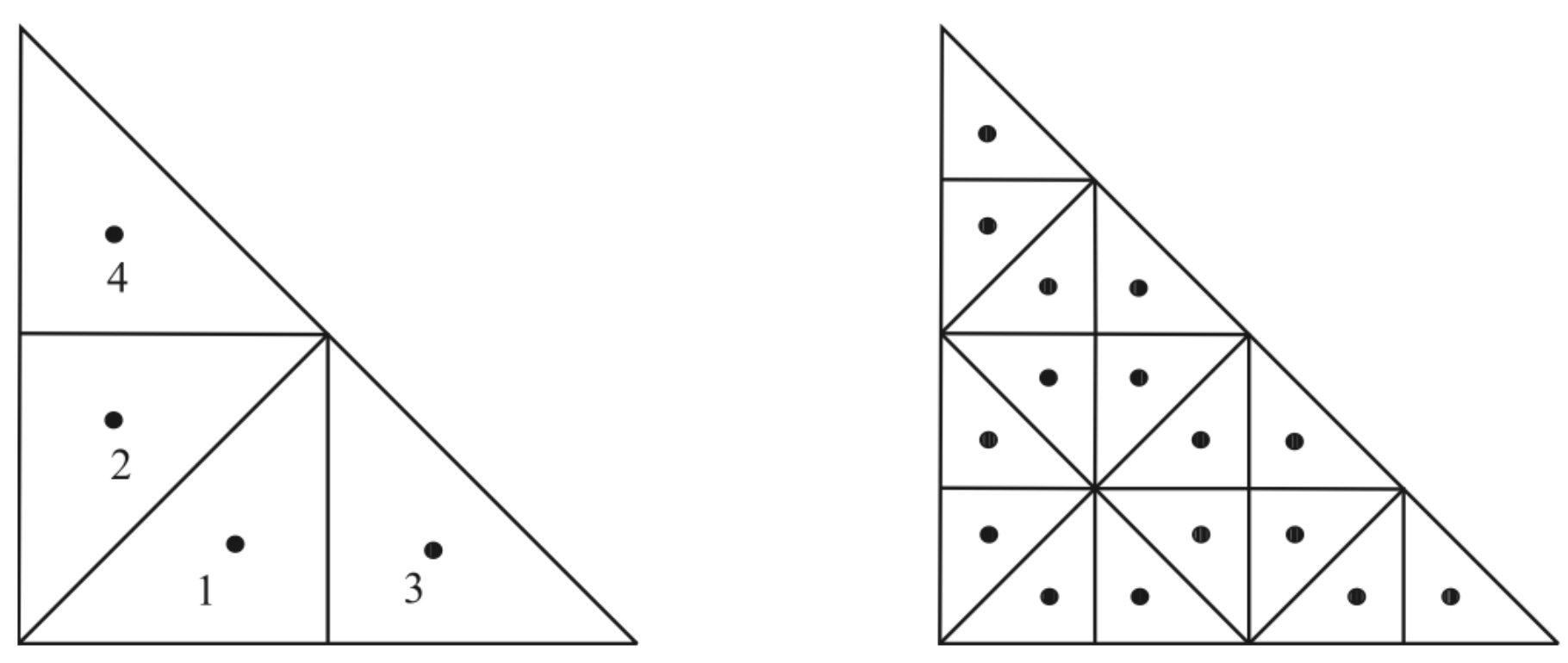

2.4. Mesh generation

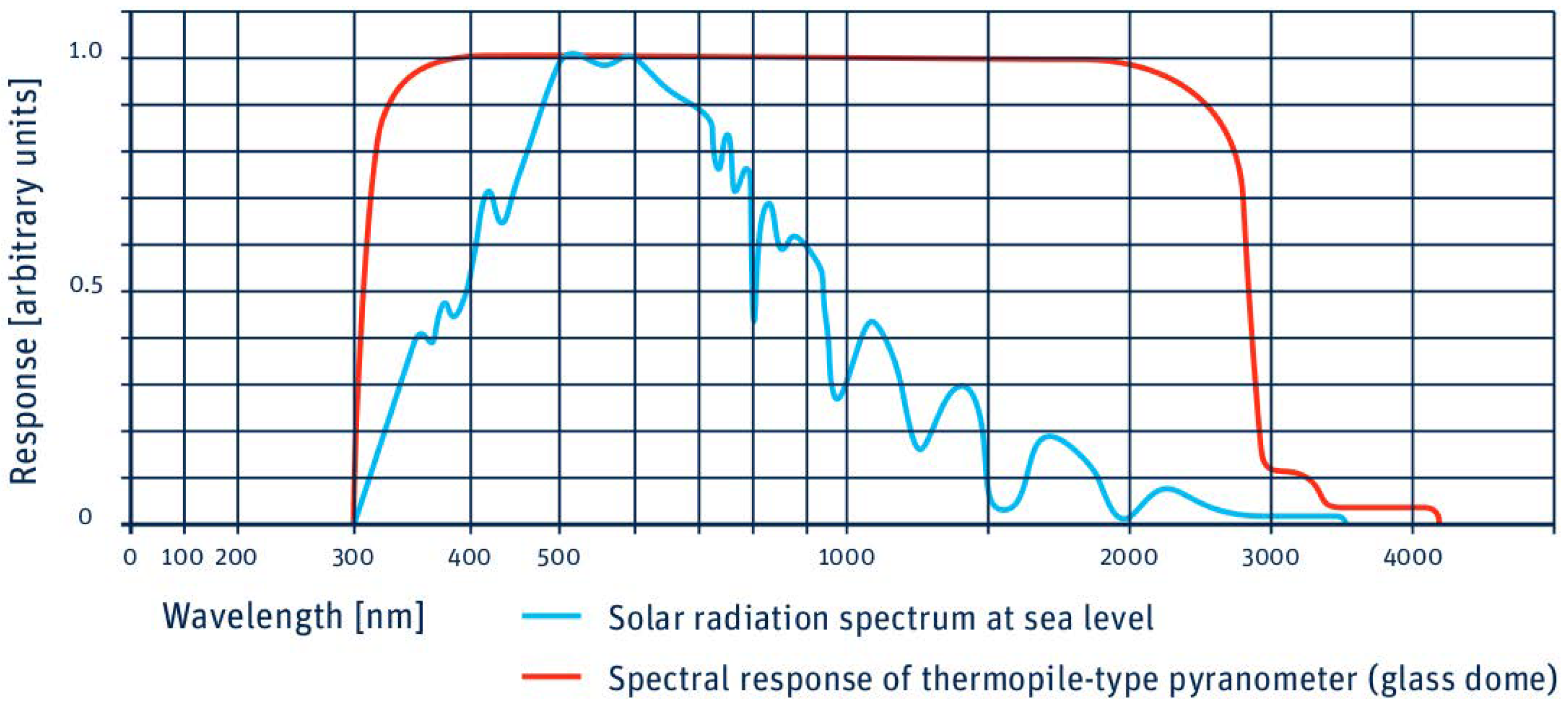

2.5. Experimental measurements of solar irradiance with pyranometers

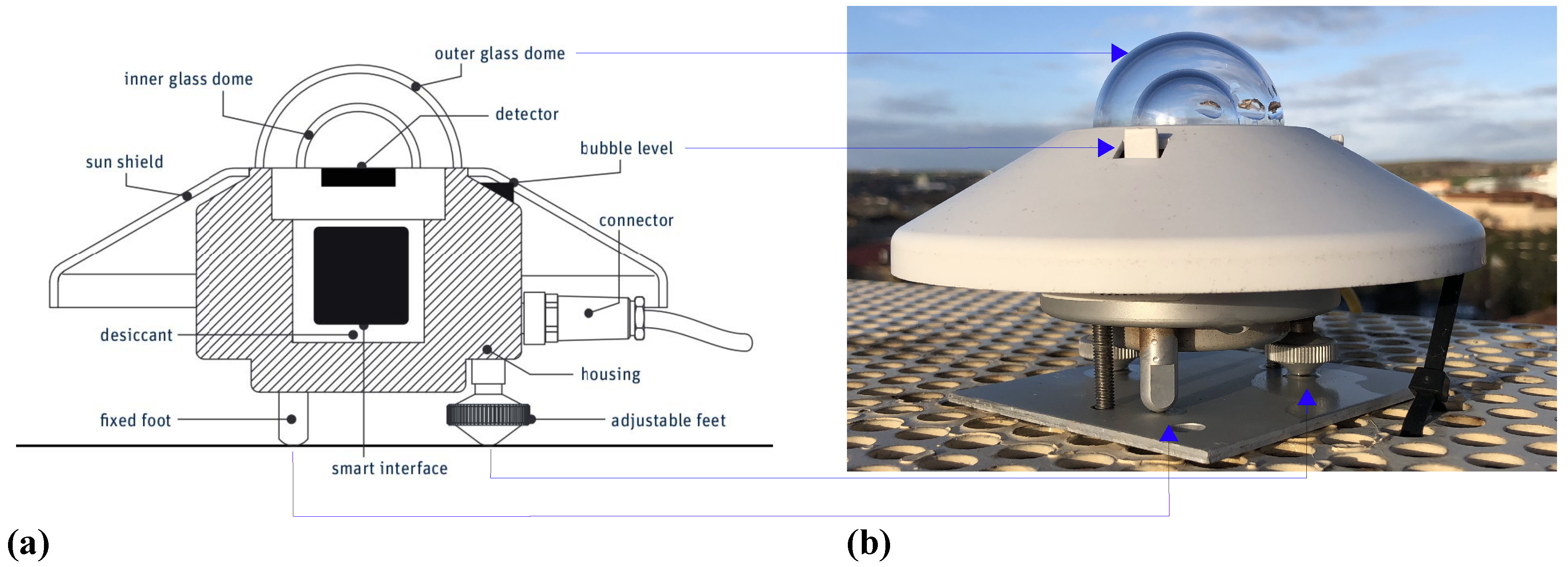

- Indirect conversion detectors: they work by converting the incident photon flux into another type of flux (usually heat), but can also be a secondary photon flux. Heat flux detectors are widely used and their operation is relatively simple. To convert the photon flux into heat flux, a highly absorbing paint or varnish is applied to the detector, which causes its temperature to rise when the light beam is impinging on it. Knowing the temperature at two points, and assuming that the steady state is reached, the intensity of the flux is calculated, which will be proportional to the temperature difference. Figure 5 (a) shows a general scheme of the parts of an indirect heat flux conversion pyranometer. In the upper part there are two domes, the outer dome has the function of avoiding energy exchanges due to convective phenomena; as a whole, the domes act as an integrating sphere. As it can be seen, the detector is surrounded by an anti-radiation shield to prevent radiation penetrating from anywhere other than the dome. Figure 5 (b) shows the Pyranometer Kipp & Zonen SMP10, belonging to the Energy Optimization, Thermodynamics and Statistical Physics Group (GTFE), with which the Global Horizontal Irradiance measurements were performed.Figure 5. Heat flux sensing pyranometer: (a) Basic scheme [49] and (b) Pyranometer belonging to the Group of Energy Optimization, Thermodynamics and Statistical Physics (GTFE) of the University of Salamanca.Figure 5. Heat flux sensing pyranometer: (a) Basic scheme [49] and (b) Pyranometer belonging to the Group of Energy Optimization, Thermodynamics and Statistical Physics (GTFE) of the University of Salamanca.

- Direct conversion detectors: again there are two types. Photoemitter cells are based on the junction of an anode and a cathode, between which there is a large potential difference (in the range of kV) and an avalanche effect is produced. On the other hand, there are detectors based on PN junctions, the photodiodes, where the current generated is proportional to the incident flux. These types of detectors have better sensitivity than avalanche detectors and work with low voltage [50].

3. Results

3.1. Experimental data acquisition

- If

- If

- If

- If

3.2. Area study, high-resolution DEM and adapted mesh

3.3. Simulation with MAPSol

3.4. Comparison of simulation results with experimental data

- : Mean Absolute Error

- : Normalized Mean Absolute Error

- : Root Mean Square Error

- : Normalized Root Mean Square Error

- : Coefficient of determination

4. Discussion and conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WP | Warning points |

| DTM | Digital Terrain Model |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DSM | Digital Slope Model |

| GHI | Global Horizontal Irradiance |

| DHI | Diffuse Horizontal Irradiance |

| DNI | Direct Normal Irradiance |

| BHI | Beam Horizontal Irradiance |

| CSP | Concentrating Solar Power |

| GIS | Geographical Information System |

| IGN | National Geographic Institute |

References

- Wong, L.; Chow, W. Solar radiation model. Applied Energy 2001, 69, 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.; Rupper, S. Impacts of topographic shading on direct solar radiation for valley glaciers in complex topography. The Cryosphere 2019, 13, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosskopf, E.; Morhart, C.; Nahm, M. Modelling Shadow Using 3D Tree Models in High Spatial and Temporal Resolution. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, S.; Kaynak, B.; Özmen, A. A software tool development study for solar energy potential analysis. Energy and Buildings 2018, 162, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Suh, J.; Kim, S.M. GIS-Based Solar Radiation Mapping, Site Evaluation, and Potential Assessment: A Review. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, R.P.; Santos, M.J.; Medina, A.; Calvo Hernández, A. High temperature central tower plants for concentrated solar power: 2021 overview. Renew. Sust. Ener. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulkan, A.; Kloog, I.; Dorman, M.; Erell, E. Modeling the potential for PV installation in residential buildings in dense urban areas. Energy and Buildings 2018, 169, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, M.; Erell, E.; Vulkan, A.; Kloog, I. shadow: R Package for Geometric Shadow Calculations in an Urban Environment. The R Journal 2019, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C. Estimating solar energy potentials on pitched roofs. Energy and Buildings 2017, 139, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, C.; Gracia Amillo, A.M.; Bardizza, G.; Abad, J.; Urbina, A. Evaluation of Solar Radiation Transposition Models for Passive Energy Management and Building Integrated Photovoltaics. Energies 2020, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Han, J.Y. The impact of shadow covering on the rooftop solar photovoltaic system for evaluating self-sufficiency rate in the concept of nearly zero energy building. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 80, 103821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stendardo, N.; Desthieux, G.; Abdennadher, N.; Gallinelli, P. GPU-Enabled Shadow Casting for Solar Potential Estimation in Large Urban Areas. Application to the Solar Cadaster of Greater Geneva. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Gong, J.; Xie, X.; Sun, J. Solar3D: An Open-Source Tool for Estimating Solar Radiation in Urban Environments. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.C.; Redweik, P.; Catita, C.; Freitas, S.; Santos, M. 3D Solar Potential in the Urban Environment: A Case Study in Lisbon. Energies 2019, 12, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, M.; Yadav, S.; Sadhu, P.; Panda, S. Determination of optimum tilt angle and accurate insolation of BIPV panel influenced by adverse effect of shadow. Renewable Energy 2017, 104, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wong, M.S.; You, L.; Santi, P.; Nichol, J.; Ho, H.C.; Lu, L.; Ratti, C. The effect of urban morphology on the solar capacity of three-dimensional cities. Renewable Energy 2020, 153, 1111–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.; Seals, R.; Ineichen, P.; Stewart, R.; Menicucci, D. A new simplified version of the perez diffuse irradiance model for tilted surfaces. Solar Energy 1987, 39, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Ledoux, H.; Stoter, J. Does a Finer Level of Detail of a 3D City Model Bring an Improvement for Estimating Shadows? In Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Springer International Publishing, 2016; pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peronato, G.; Rey, E.; Andersen, M. 3D model discretization in assessing urban solar potential: the effect of grid spacing on predicted solar irradiation. Solar Energy 2018, 176, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Neumann, U. , 2.5D Dual Contouring: A Robust Approach to Creating Building Models from Aerial LiDAR Point Clouds. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, G.; Zhang, F.; Pyle, J. Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences: Second Edition. Elsevier, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Šúri, M.; Hofierka, J. A new GIS-based solar radiation model and its application to photovoltaic assessments. T. GIS 2004, 8, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/grid/solar-resource/solar- glossary.html.

- Díaz, F.; Montero, G.; Escobar, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Montenegro, R. An adaptive solar radiation numerical model. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2012, 236, 4611–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, F.; Montero, G.; Escobar, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Montenegro, R. A new predictive solar radiation numerical model. Applied Mathematics and Computation 267, 596–603. [CrossRef]

- Montero, G.; Escobar, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Montenegro, R. Solar radiation and shadow modelling with adaptive triangular meshes. Solar Energy 2009, 83, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, J.K. (Ed.) Prediction of solar radiation on inclined surfaces; D. Reidel Publishing Co.: Dordrecht, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kasten, F.; Young, A.T. Revised optical air mass tables and approximation formula. Applied Optics 1989, 28, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, F. The Linke turbidity factor based on improved values of the integral Rayleigh optical thickness. Solar Energy 1996, 56, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Muriel, M.; Alarcón-Padilla, D.C.; López-Moratalla, T.; Lara-Coira, M. Computing the solar vector. Solar Energy 2001, 70, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, F.; Montero, H.; Santana, D.; Montero, G.; Rodríguez, E.; Mazorra Aguiar, L.; Oliver, A. Improving shadows detection for solar radiation numerical models. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2018, 319, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, M. A grid generator based on 4-triangles conforming mesh-refinement algorithms. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 1987, 24, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, C.; Jóźków, G. Remote sensing platforms and sensors: A survey. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 115, 22–36, Theme issue ‘State-of-the-art in photogrammetry, remote sensing and spatial information science’. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibe, D.; Amor, M.; Doallo, R. Big Data Geospatial Processing for Massive Aerial LiDAR Datasets. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassar, A.A.A.; Cha, S.H. Review of geographic information systems-based rooftop solar photovoltaic potential estimation approaches at urban scales. Applied Energy 2021, 291, 116817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BARTHA, G.; KOCSIS, S. STANDARDIZATION OF GEOGRAPHIC DATA: THE EUROPEAN INSPIRE DIRECTIVE. European Journal of Geography 2022, 2. Available online: https://eurogeojournal.eu/index.php/egj/article/view/36/10.

- Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32007L0002.

- Plan Nacional de Observacion del Territorio - PNOT. 2023. Available online: https://www.ign.es/web/plan-nacional-de-observacion-del-territorio.

- Sánchez-Aparicio, M.; González-González, E.; Martín-Jiménez, J.A.; Lagüela, S. Solar Potential Analysis of Bus Shelters in Urban Environments: A Study Case in Ávila (Spain). Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aparicio, M.; Martín-Jiménez, J.A.; González-González, E.; Lagüela, S. Laser Scanning for Terrain Analysis and Route Design for Electrified Public Transport in Urban Areas. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aparicio, M.; Del Pozo, S.; Martín-Jiménez, J.A.; González-González, E.; Andrés-Anaya, P.; Lagüela, S. Influence of LiDAR Point Cloud Density in the Geometric Characterization of Rooftops for Solar Photovoltaic Studies in Cities. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Jiménez, J.; Del Pozo, S.; Sánchez-Aparicio, M.; Lagüela, S. Multi-scale roof characterization from LiDAR data and aerial orthoimagery: Automatic computation of building photovoltaic capacity. Automation in Construction 2020, 109, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organismo Autónomo Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica, Centro de descargas. 2023. Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/index.jsp.

- Cascón, J.; Ferragut, L.; Asensio, M.; Prieto, D.; Álvarez, D. Neptuno ++: An adaptive finite element toolbox for numerical simulation of environmental problems. In XVIII Spanish-French School Jacques- Louis Lions about Numerical Simulation in Physics and Engineering; Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Montenegro, R.; Montero, G.; González-Yuste, J. Simultaneous untangling and smoothing of tetrahedral meshes. COMPUTER METHODS IN APPLIED MECHANICS AND ENGINEERING 2003, 192, 2775–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, R.; Cascon, J.M.; Escobar, J.M.; Rodriguez, E.; Montero, G. An automatic strategy for adaptive tetrahedral mesh generation. APPLIED NUMERICAL MATHEMATICS 2009, 59, 2203–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Casinière, A.C.; Cachorro-Revilla, V.E. La radiación solar en el sistema tierra-atmósfera; Secretariado de publicaciones e Intercambio Editorial; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kipp & Zonen. Instruction manual. CM 121 shadow ring. Delftechpark 36, 2628 XH Delf, 2004.

- Kipp & Zonen. Instruction manual. SMP series. Smart Pyranometer. Kipp & Zonen, Delftechpark 36, 2628 XH Delf, 2017.

- Bardia, R. Dispositivos electrónicos. Fundamentos de electrónica, volumen 5; Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, J.M.S.; Martín, J.R.; Alonso, C.J.; de Cos Escuin, M.C.S.; Cadalso, J.M.; Bartolomé, M.L. Atlas de Radiación Solar en España utilizando datos de SAF de clima de EUMETSAT; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Solargis. Solar data behind the maps. 2023. Available online: https://solargis.com/es/maps-and-gis-data/techspecs.

- University of Oregon. Sun path chart program. 2023. Available online: http://solardata.uoregon.edu/SunChartProgram.php.

| Feature | First coverage |

|---|---|

| Minimum point density | |

| Years of flight | |

| Geodetic reference system | ETRS89 zones 28, 29, 30 and 31 as appropriate |

| Altimetric reference system | Orthometric altitudes, reference geoid EGM08 |

| RMSE Z | |

| Estimated planimetric accuracy | |

| File size | |

| File format | LAS 1.2 format 3 |

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Spectral range | nm |

| Response time | s |

| Response time | s |

| Non-linearity | |

| Spectral selectivity | nm |

| Field of view |

| Source | AEMET [51] | Experimental data | Relative differences (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | |||||||

| January | 2.08 | 1.18 | 2.31 | 1.47 | 11.06 | 24.58 | |

| February | 3.09 | 1.89 | 3.09 | 1.97 | 0.00 | 4.23 | |

| March | 4.49 | 2.82 | 4.74 | 3.08 | 5.57 | 9.22 | |

| April | 5.56 | 3.50 | 5.19 | 2.89 | 6.65 | 17.43 | |

| May | 6.44 | 4.08 | 6.90 | 4.65 | 7.14 | 13.97 | |

| June | 7.60 | 5.45 | 7.33 | 5.13 | 3.55 | 5.87 | |

| July | 7.82 | 5.96 | 7.82 | 6.17 | 0.00 | 3.52 | |

| August | 6.84 | 5.05 | 6.95 | 5.48 | 1.61 | 8.51 | |

| September | 5.27 | 3.71 | 5.21 | 3.75 | 1.14 | 1.08 | |

| October | 3.43 | 2.14 | 3.53 | 2.32 | 2.92 | 8.41 | |

| November | 3.38 | 1.28 | 2.26 | 1.27 | 33.14 | 0.78 | |

| December | 1.78 | 0.96 | 1.53 | 0.67 | 14.04 | 30.21 | |

| Source | AEMET [51] | Solargis [52] | Measured records | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | ||

| 1680 | 1753 | 1733.65 | ||||

| − | − | 1185.93 | ||||

| Daily | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | ||

| 4.75 | ||||||

| − | − | 3.25 | ||||

| Date | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 15th, 2021 | |||||

| August 4th, 2022 | |||||

| Sept. 4th, 2022 | |||||

| Sept. 11th, 2022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).