Submitted:

17 February 2024

Posted:

20 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms and process of CO2-EOR

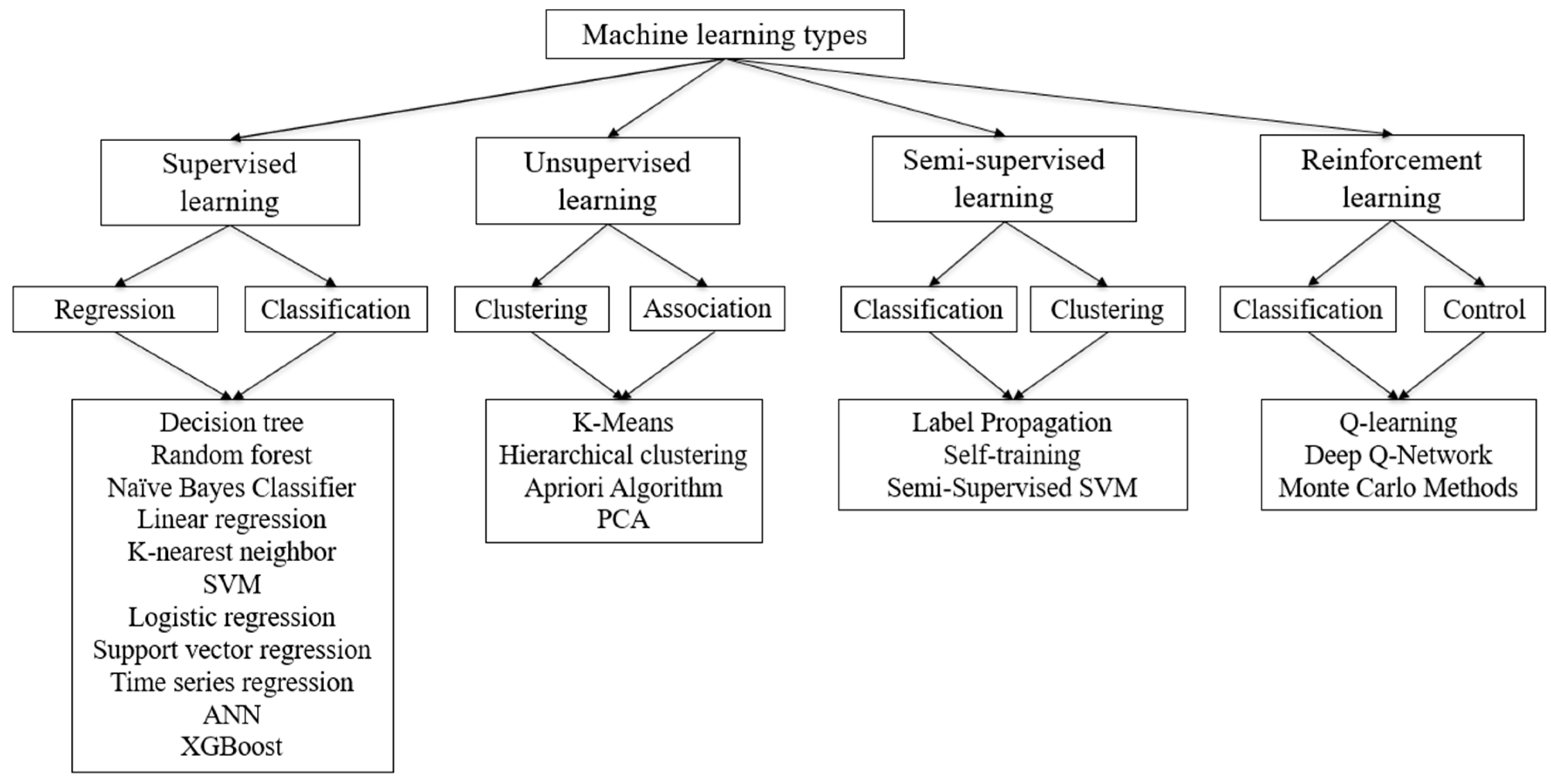

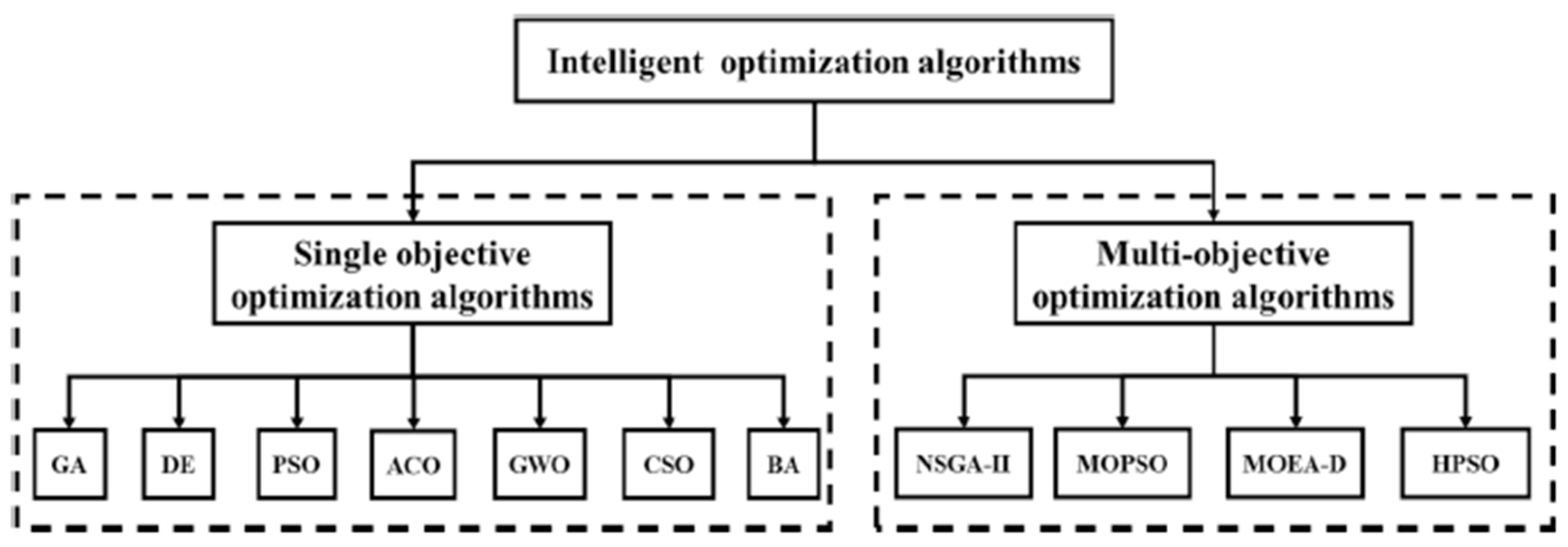

3. Summary of machine learning approaches

4. Application of ML in CO2-EOR

4.1. Minimum miscibility pressure (MMP)

- a)

- experimental methods such as slim-tube tests (Yellig & Metcalfe, 1980), rising-bubble apparatus (Christiansen & Haines, 1987), vanishing interfacial tension (Rao & Lee, 2002);

- b)

- empirical correlations (Alston et al., 1985; Orr & Jensen, 1984; Shokir, 2007; Yellig & Metcalfe, 1980) and computational techniques such as single mixing-cell and multiple mixing-cell approaches (Ahmadi & Johns, 2011).

4.2. Water-alternating-gas (WAG)

4.3. Well placement optimization (WPO)

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosseinzadeh Helaleh & Alizadeh (2016) | SVM (ACO, GA, PSO) | 200 | 80% train + 20% test | Fractional oil recovery | RLC, RLD, NgAO, NgGO, MSWAG, NC, SGR, NPe, NSCon, NB, Nα, Nσ, λ*Dx, Nn, He | ACO has high accuracy and low computational time compared to ANN, GA, and PSO. | Evaluate with both experiments and simulations. Limited to a similar geological model. | Only has SVM model. | 8 |

| Le Van & Chon (2017) | ANN | 223 (simulation) | 45% train + 20% test + 35% validation | Oil recovery factor, oil rate, GOR, accumulative CO2 production, net CO2 storage | Swi, kv/kh, WAG ratio, duration of each cycle | ANN models can support numerical simulation of CO2-EOR projects. WAG ratio less than 1.5 is best. | Evaluated multiple objectives but only limited to ANN. | Only have simulation results as trained data. | 8 |

| Van & Chon (2018) | ANN | 263 (simulation) | 50% train + 20% test + 30% validation | Oil recovery + net CO2 storage + cumulative gaseous CO2 production | Kv/Kh, WAG ratio, Sw, well distance between each injector, T | ANN can help estimate oil recovery and CO2 storage. 25 injection cycle is best. | Evaluate different WAG ratios but limited to ANN models only. | Only have simulation results as trained data. | 7 |

| Mohagheghian et al. (2018) | GA, PSO | 2000 (simulation) | NA | NPV + incremental recovery factor | Water and gas injection rates, BHP of producers, cycle ratio, cycle time, injected gas composition, total WAG period. | PSO is capable of optimizing WAG variables and projects at field scale. | First used GA in WAG at field scale. Evaluated with three case studies. Limited to specific geological models. | Only GA and PSO are evaluated. Specific to E-segment. | 9 |

| Nwachukwu, Jeong, Sun, et al. (2018) | XGBoost, MADS | 1000 (simulation) | 50% train + 50% test | Oil/water/gas production rates, well locations, NPV | Well x-coordinates, well y-coordinates, water/gas injection rates, well block ϕ/k, well block Swi | The new model combined XGBoost and MADS provided high accuracy. | Demonstrated with a case study in which underlying geology is uncertain. Limited to one model. | Only XGBoost is employed. | 8 |

| Nait Amar et al. (2018) | ANN/GA, ACO | 85 | 88% train + 12% test | Field oil production total | Gas/water injection rates, gas/water injection half-cycle, WAG ratio, and slug size. | Both GA and ACO are highly effective in the optimization of the WAG process. | Demonstrated the application of a time-dependent proxy model for the WAG process. Without further application of the case study. | Restricted to specific geological models. Limited simulation runs | 8 |

| Belazreg et al. (2019) | Regression, GDMH | 4290 | 70% train + 30% test | Incremental recovery factor | kh, kv, API, gas gravity, water viscosity, solution GOR, WAG ratio, WAG cycle, land coefficient, reservoir pressure, PV of injected water, PV of injected gas. | GMDH performed better in selecting effective input parameters and optimizing the model structure. | Novel approach but didn’t apply real field WAG pilot data to validate. | Limited to two ML methods. | 8 |

| Jaber et al. (2019) | CCD | 81 | NA | Oil recovery | k, ϕ, kv/kh, cyclic length, BHP, WAG ratio, CO2 slug size | The new proxy model can predict oil recovery. The optimum WAG ratio is 1.5. | Developed a new proxy model based on CCD, But limited to one model. | Limited data points and only from simulation runs. | 7 |

| Menad & Noureddine (2019) | MLP (LMA, BR, SCG) + NSGA-II | From 2010 to 2018 | NA | FOPR, FWPR | Time, FWIR, FGIR, the value of the needed parameter at the previous time step | MLP-LMA has the highest accuracy and lowest computation time. | Developed a dynamic proxy model for multiple objectives. But limited to one geological model. | The database was generated based on multiple runs of the simulation. | 8 |

| Nait Amar & Zeraibi (2020) | SVR, GA | 75 | NA | Field oil production total | Injection rates of water and gas, half-cycle injection time, WAG ratio, slug size, initialization time of the process | SVR-GA provides high accuracy and reasonable CPU time. | Established a dynamic proxy model based on SVR-GA, but no comparison with other algorithms. | Limited data points and only one model evaluated. | 7 |

| Yousef et al. (2020) | ANN | 8 years * 37 wells | 85% train + 15% test | Oil/gas/water production rate, GOR, infill well location | Well trajectory data, well logs, seismic data, production and injection history, reservoir pressure, choke opening, and WHP history. | Implementing ANNfor top-downmodeling can predictreservoir performanceunder WAG. | Can predict the reservoir performance 3 months ahead. But simplify the data gathering, modeling, and validation process. | Unknown about specific input data. No comparison with other models or field case studies. | 6 |

| Belazreg & Mahmood (2020) | GDMH | 177 | 70% train + 30% test | Incremental oil recovery factor | Rock type, WAG process type, reservoir horizontal permeability, API, oil viscosity, reservoir pressure and temperature, and hydrocarbon pore volume of injected gas. | GDMH models can predict three WAG incremental recovery factors: sandstone immiscible gas injection, sandstone miscible gas injection, and carbonate miscible gas injection | Proved GDMH can model the WAG process and has good potential. More data and validation are needed to improve model robustness and applicability. | Limited published WAG pilot data. | 8 |

| You et al. (2020) | ANN | 820 | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validation | Oil recovery, CO2 storage, and project NPV | Water injection time, CO2 injection time, producer BHP, water injection rate. | The ANN proxy model can help improve the prediction performance. | Could handle two or three objectives very well when a limited number of control parameters | Only suitable for limited input parameters. | 8 |

| You et al. (2021) | Gaussian SVR - PSO | 217 | NA | Hydrocarbon recovery + CO2 sequestration volume + NPV | FOPR*2, gas cycle*5, water cycle *5 | The proposed method can optimize the WAG process with high accuracy. | Nice sensitivity studies of CO2 price and oil price on NPV. Limited comparison with other ML models. | Restricted to specific geological models. | 8 |

| Enab & Ertekin (2021) | ANN | 2000 | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validation | Production prediction, production schemes design, history matching | 25 inputs including reservoir rock characteristics, initial conditions, oil composition, well design parameters, and injection strategy parameters. | ANN provides a faster prediction for fish-bone structure in low permeability reservoirs. | Nice project design and economic analysis, but limited to ANN model only. | Limitations wereimposed by defining the range of each variable. | 8 |

| Afzali et al. (2021) | GEP | 96 | 67% train + 33% test | Recovery factor | Oil viscosity, gas/water injection rates, k, PVI, number of cycles | The developed model is successful when compared with experimental results. | Novelty in using GEP. The dataset is from mathematical correlation. | Limited and less supportive dataset. | 8 |

| Lv et al. (2021) | ANN-PSO | 2100 | 70% train + 15% test + 15% validation | Oil production | So, Pi, k, ϕ, h, Pwf, water injection rate, water cut before gas flooding, gas injection rate, water injection volume, cycle time, water injection time, production rate, grid size | ANN-PSO provides a good model for parameter optimization of CO2 WAG-EOR. | Routine procedures, not too much novelty in applying ANN-PSO. | No comparison with other ML models. | 7 |

| Nait Amar et al. (2021) | MLP-LM, RBFNN-ACO/GWO | 82 | 88% train + 12% test | Field oil production total | Water/gas injection rates, injection half-cycle, downtime, WAG ratio, gas slug size | MLP-LMA is best. The proxy model can significantly reduce simulation time and conserve high accuracy. | The application of GWO is novel. Limited runs and may have overfitting problems. | Water cut is limited to 50%. Reservoir pressure must be higher than MMP. | 8 |

| Junyu et al., (2021) | Gaussian-SVR | 1400 | NA | Cumulative oil production and cumulative CO2 storage. | Water/gas cycle, producer BHP, water injection rate, etc. (91 variables in total) | Gaussian-SVR performs best. | Showed the possibility to design a CO2-WAGproject using as many inputs as possible. | Given the large number of input parameters, the dataset may not be large enough. | 7 |

| Sun et al. (2021) | SVR, MLNN, RSM | 600 | 83% train + 17% test | Oil production, CO2 storage, NPV. | Duration of CO2 and water injection cycles, water injection rate, production well specifications, oil price, CO2 price, etc. (62 parameters) | The MLNN model can handle problems with large input and output dimensions. | Compared three different methods. But only suitable for specific geological models. | The average reservoir pressure must be between 3700 – 5400 psi. | 8 |

| Huang et al. (2021) | LSTM | 5404 | 90% train + 10% test | Oil production, GOR, water cut | Daily liquid rate, daily oil/gas/water rate, GIR, WIR, reservoir pressure, WHFP, choke size of producers. | The calculation time of LSTM is 864% less than the simulation, while the prediction error of the LSTM method is 261% less than the simulation. | The model is based on real reservoir data over 15 years. But limited to one ML model. | Only one ML model is considered. No comparison with other models. | 7 |

| H. Li et al. (2022) | RF | 216 | 70% train + 30% test | Cumulative oil production, CO2 storage amount, CO2 storage efficiency | CO2-WAG period, CO2 injection rate, water-gas ratio, reservoir properties, oil properties, depth, layer thickness, Soi, well operation | CO2-WAG cycle time has a slight influence on oil production. Random forest can predict oil production and CO2 storage. | Proved RF has high computation efficiency and accuracy in CO2-WAG projects. But no comparison of different ML models. | Small dataset and only one ML model is studied. | 7 |

| Andersen et al. (2022) | LSSVM – PSO/GA/GWO/GSA | 2500 | 70% train + 15% test + 15% validation | Oil recovery factor | Water-oil and gas-oil mobility ratios, water-oil and gas-oil gravity numbers, reservoir heterogeneity factor, two hysteresis parameters, and water fraction. | LSSVM with GWO or PSO performed better than GA or GSA. | Very detailed and thorough study. The dataset is relatively large. Some limitations of input parameters. | Several important parameters were not varied much. | 9 |

| Singh et al. (2023) | DNN - GA | 2200 | 70/80% train + 30/20% test | Maximize oil recovery | Water injection rates, gas-to-water ratio, slug size. | DNN-GA workflow can identify improved WAG parameters over the baseline recovery, with incremental increases of 0.5-2%. | Presents a novel workflow for WAG optimization using ML. Requires a large number of simulation runs (2200 here) to initially train DNN. | Limited to optimizing WAG parameters. | 7 |

| Asante et al. (2023) | LSTM | 2345*3 | 80% train + 20% test | Oil production rate, oil recovery factor | Bottom-hole pressure at injector and producer, water and gas injection volumes, WAG cycle. | LSTM can model complex time-series data without the use of the geological model. | Shows the ability of LSTM to perform time series analysis. But the input parameters are restricted. | Requires large amounts of quality field data. | 7 |

| Matthew et al. (2023) | ANN-NSGA-II | 68 + 97 | NA | Maximize oil produced and CO2 storage | Water and gas injection rate, half-cycle length, time step. | The developed proxy model can predict both simple and complex models. | Developed a dynamic proxy model for multiple objectives. But the dataset size is limited. | Limited simulation runs. Has a high possibility of overfitting. | 7 |

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nwachukwu et al. (2018) | XGBoost | 200, 500, 1000 | NA | Total profit, cumulative oil/gas produced, net CO2 stored | Well-to-well pairwise connectivity, injector block k and ϕ, initial injector block saturations | Quick evaluation of well placement using well-to-well connectivity was successful with 1000 simulation runs and R2 = 0.92. | No co-optimization of oil recovery and CO2 storage, only ML proxy usage. | The dataset is from simulation runs. Only suitable for one geological model. | 8 |

| Selveindran et al. (2021) | AdaBoost, RF, ANN | 3000, 2000, 1000 | 70% train + 30% test | Incremental oil production | K, ϕ, PV, initial fluid saturation, pressure, time of flight, well-to-well distances, distance to the injector, injection rate, and injection depth. | Stacked learner is better than an individual learner. ML helps rapidly identify the areas that are optimal for injection. | Detailed and comprehensive analysis, including posterior sampling. | Heavily rely on the geological model. | 8 |

4.4. Oil production/recovery factor

4.5. Multi-objective optimization

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi et al. (2018) | LSSVM | 46 | 80% train + 20% test | Oil recovery factor | BHP of injection well, CO2 injection rate, CO2 injection concentration, BHP of production well, oil production rate | The hybridization of LSSVM and BBD is statistically correct for predicting RF. | Provided the possibility of using ML and comparing it with commercial software. But limited dataset. | Small dataset and only suitable for similar oil reservoirs. Only valid for the same input parameters range. | 7 |

| Chen & Pawar (2019) | MARS, SVR, RF | 500, 250, 100 | NA | Recovery factor | Thickness, depth, k, Sor, CO2 injection rate, BHP of production well | MARS has the best performance. | Applied to 5 fields in Permian Basin and had good matches. Heavily relies on a base model and may not fully represent diverse ROZs. | Significant assumptions are made regarding uncertain parameters like residual oil saturation. | 8 |

| Karacan (2020) | FL | 24 | 83% train + 17% test | Recovery factor | Lithology, API, ϕ, k, HCPV, depth, net pay, Pi, well spacing, Sorw | FL provided a reasonably accurate prediction. | Though a small dataset, but provides the possibility of using ML in recovery factor prediction. | Too difficult to draw statistical conclusions from such a small dataset. | 7 |

| Iskandar & Kurihara (2022) | AR, MLP, LSVM | 3653 * 8 wells | 40% train + 20% test + 40% validation | Oil, gas, and water production | ϕ, k, formation thickness, BHP, flow capacity, storage capacity | The AR model is best, with long and consistent forecast horizons across wells. LSTM performs well but has shorter forecast horizons. MLP has high variability and short forecast horizons. | First time series forecasting study. No model updating/retraining over time. Overall, it is a solid study. | Limited hyperparameter tuning is done. Only three models were tested. | 9 |

4.6. PVT Properties

4.7. CO2-foam flooding

5. Benefits and limitations of ML

6. Conclusions

- Our literature review showed that most reports on model performance indicators are limited to the size of the data bank, making it difficult to accurately assess the quality of the model over time or track its drift with new data.

- Regarding validation and verification, the CO2-EOR has many reliable, dependable, and well-established techniques for verification and validation procedures for ML models. The research highlights several issues with current machine learning models, including model scalability, validation and verification deficiencies, and an absence of published data regarding the establishment costs of ML models.

- Most CO2-EOR research focused on MMP predictions and WAG design. The applications in recovery factor, well placement optimization, and PVT properties are limited.

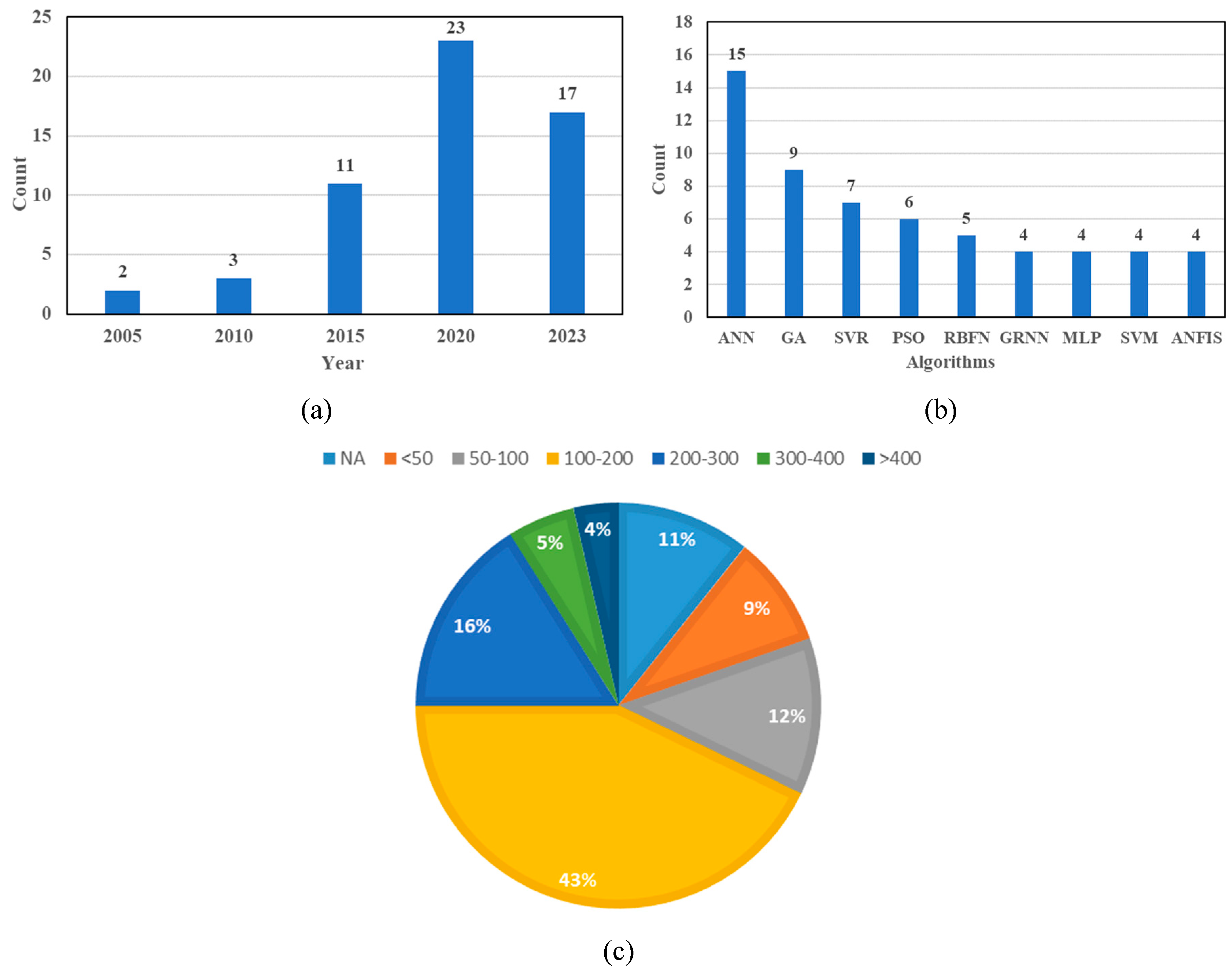

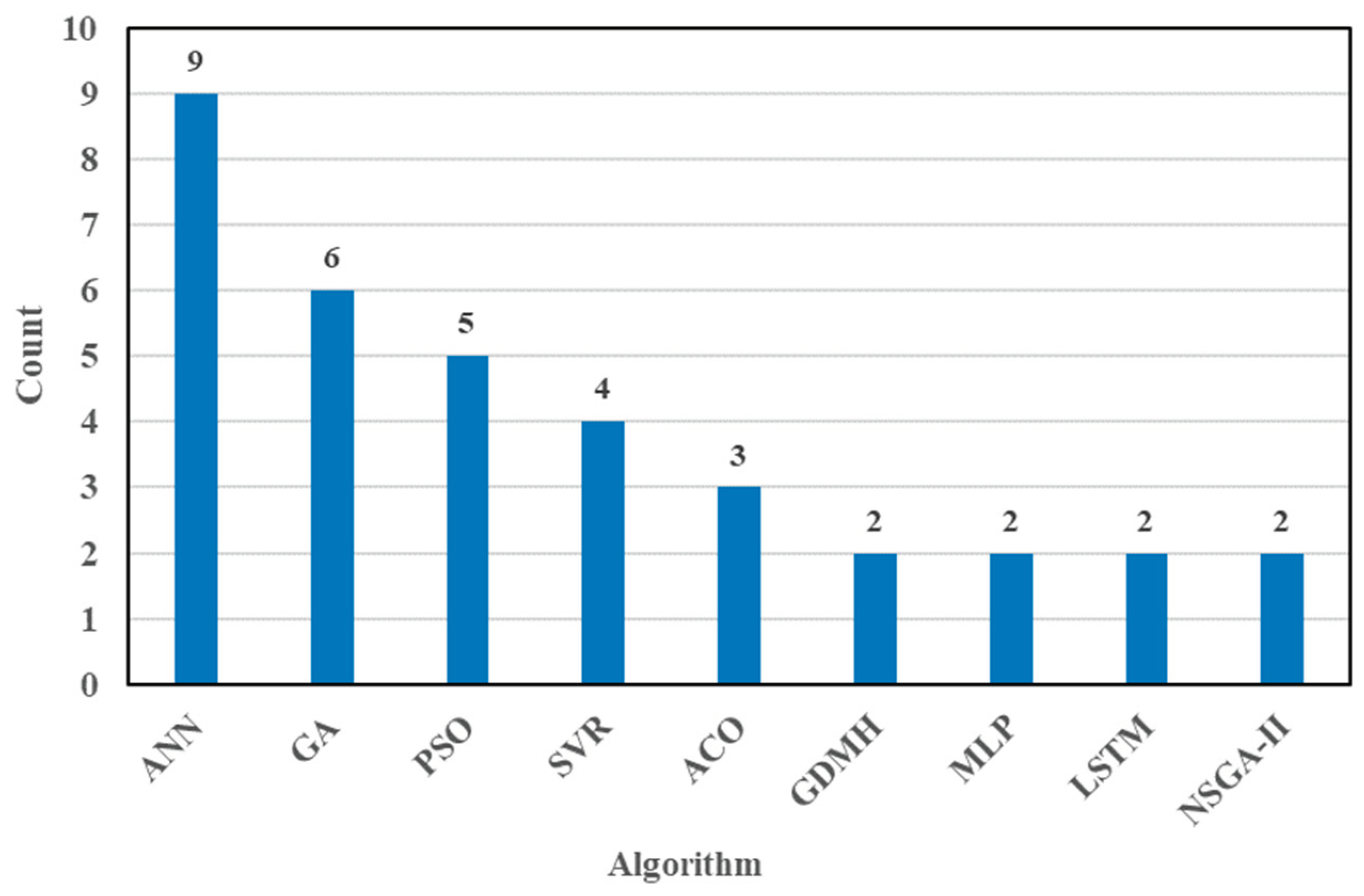

- We also found that ANN is the most employed ML algorithm, and GA is the most popular optimization algorithm based on 101 reviewed papers. ANN has been proven to be flexible enough to be implemented to build intelligent proxies.

- ML algorithms can greatly reduce the computational cost and time to perform compositional simulation runs. However, ML applications for well placement optimization in CO2-EOR are very limited.

- The reliability of coupled ML-metaheuristic paradigms based on reservoir simulation results needs further investigation.

Nomenclature

| AARD | Average absolute relative deviation |

| AARE | Average absolute relative error |

| ABC | Artificial bee colony |

| ACO | Ant colony optimization |

| ACE | Alternating conditional expectation |

| AR | Auto-regressive |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ANFIS | Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system |

| BA | Bee algorithm |

| BOA | Bayesian optimization algorithm |

| BPNN | Backpropagation algorithm neural network |

| BR | Bayesian regularization |

| CatBoost | Categorical boosting |

| CCD | Central composite design |

| CFNN | Cascade forward neural network |

| CGAN | Conditional generative adversarial network |

| CM | Committee machine |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| COA | Cuckoo optimization algorithm |

| CSO | Cuckoo search optimization |

| DA | Dragonfly algorithm |

| DBN | Deep belief network |

| DE | Differential evolution |

| DNN | Dense neural network |

| ERT | Extremely randomized trees |

| FCNN | Fully connected neural network |

| FGIR | Field gas injection rate |

| FL | Fuzzy logic |

| FN | Functional network |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| GB | Gradient boosting |

| GBDT | Gradient boosting decision tree |

| GBM | Gradient boost method |

| GEP | Gene expression programming |

| GFA | Genetic function approximation |

| GIR | Gas injection rate |

| GMDH | Group method of data handling |

| GP | Genetic programming |

| GPR | Gaussian process regression |

| GRNN | Generalized regression neural network |

| GSA | Gravitational search algorithm |

| GWO | Grey wolf optimization |

| He | Hurst exponent |

| HPSO | Hybrid particle swarm optimization |

| ICA | Imperialist competitive algorithm |

| KXGB | Knowledge-based XGB |

| LGBM | light gradient boosting machine |

| LM | Levenberg – Marquardt |

| LR | Lasso regression |

| LSSVM | Least-squares support vector machine |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| MADS | Mesh adaptive direct search |

| MARS | Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines |

| MASRD | Mean absolute symmetric relative deviation |

| MEA | Mind evolutionary algorithm |

| MF | Membership function |

| MKF | Mixed kernels function |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression |

| MLNN | Multi-layer neural networks |

| MOPSO | Multi-objective particle swarm optimization |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| NNA | Neural network analysis |

| NPV | Net present value |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm version II |

| PLS | Partial least squares |

| POLY | Polynomial function |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| RBFN | Radial-based function networks |

| RFFI | Random forest feature importance |

| RR | Ridge regression |

| RSM | Response surface models |

| SBFS | Sequential backward floating selection |

| SBS | Sequential backward selection |

| SCG | Scaled conjugate gradient |

| SFS | Sequential forward selection |

| SFFS | Sequential forward floating selection |

| SGB | Stochastic gradient boosting |

| SGR | Solution gas ratio |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive explanations |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| TLBO | Teaching learning-based optimization |

| TPVT | Total pore volume tested |

| WIR | Water injection rate |

| WHFP | Well head flow pressure |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

References

- Afzali, S., Mohamadi-Baghmolaei, M., & Zendehboudi, S. (2021). Application of Gene Expression Programming (GEP) in Modeling Hydrocarbon Recovery in WAG Injection Process. Energies, 14(21), 7131. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, K., & Johns, R. T. (2011). Multiple-Mixing-Cell Method for MMP Calculations. SPE Journal, 16(04), 733–742. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M. A., Zendehboudi, S., & James, L. A. (2017). A reliable strategy to calculate minimum miscibility pressure of CO2-oil system in miscible gas flooding processes. Fuel, 208, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M. A., Zendehboudi, S., & James, L. A. (2018). Developing a robust proxy model of CO2 injection: Coupling Box–Behnken design and a connectionist method. Fuel, 215, 904–914. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.-A., & Ebadi, M. (2014). Fuzzy Modeling and Experimental Investigation of Minimum Miscible Pressure in Gas Injection Process. Fluid Phase Equilibria, 378, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Alomair, O. A., & Garrouch, A. A. (2016). A general regression neural network model offers reliable prediction of CO2 minimum miscibility pressure. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology, 6(3), 351–365. 3. [CrossRef]

- Alston, R. B., Kokolis, G. P., & James, C. F. (1985). CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressure: A Correlation for Impure CO2 Streams and Live Oil Systems. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal, 25(02), 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Amiri Kolajoobi, R., Emami Niri, M., Amini, S., & Haghshenas, Y. (2023). A Data-Driven Proxy Modeling Approach Adapted to Well Placement Optimization Problem. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 145(1). [CrossRef]

- Ampomah, W., Balch, R. S., Grigg, R. B., McPherson, B., Will, R. A., Lee, S., Dai, Z., & Pan, F. (2017). Co-optimization of CO2-EOR and storage processes in mature oil reservoirs. Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology, 7(1), 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P. Ø., Nygård, J. I., & Kengessova, A. (2022). Prediction of Oil Recovery Factor in Stratified Reservoirs after Immiscible Water-Alternating Gas Injection Based on PSO-, GSA-, GWO-, and GA-LSSVM. Energies, 15(2), 656. [CrossRef]

- Asante, J., Ampomah, W., & Carther, M. (2023, May 15). Forecasting Oil Recovery Using Long Short Term Memory Neural Machine Learning Technique. SPE Western Regional Meeting. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Asoodeh, M., Gholami, A., & Bagheripour, P. (2014). Oil-CO2 MMP Determination in Competition of Neural Network, Support Vector Regression, and Committee Machine. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology, 35(4), 564–571. [CrossRef]

- Belazreg, L., & Mahmood, S. M. (2020). Water alternating gas incremental recovery factor prediction and WAG pilot lessons learned. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology, 10(2), 249–269. 2. [CrossRef]

- Belazreg, L., Mahmood, S. M., & Aulia, A. (2019). Novel approach for predicting water alternating gas injection recovery factor. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology, 9(4), 2893–2910. 4. [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.-Q., Han, B., Du, Z.-M., Jaubert, J.-N., & Li, M.-J. (2016). Integrating support vector regression with genetic algorithm for CO2-oil minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) in pure and impure CO2 streams. Fuel, 182, 550–557. [CrossRef]

- Chemmakh, A., Merzoug, A., Ouadi, H., Ladmia, A., & Rasouli, V. (2021, December 9). Machine Learning Predictive Models to Estimate the Minimum Miscibility Pressure of CO2-Oil System. Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference. 9 December. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., & Pawar, R. J. (2019). Characterization of CO2 storage and enhanced oil recovery in residual oil zones. Energy, 183, 291–304. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Fu, K., Liang, Z., Sema, T., Li, C., Tontiwachwuthikul, P., & Idem, R. (2014). The genetic algorithm based back propagation neural network for MMP prediction in CO2-EOR process. Fuel, 126, 202–212. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Wang, X., Liang, Z., Gao, R., Sema, T., Luo, P., Zeng, F., & Tontiwachwuthikul, P. (2013). Simulation of CO2-oil minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) for CO2 enhanced oil recovery (EOR) using neural networks. Energy Procedia, 37, 6877–6884. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Zhang, C., Jia, N., Duncan, I., Yang, S., & Yang, Y. (2021). A machine learning model for predicting the minimum miscibility pressure of CO2 and crude oil system based on a support vector machine algorithm approach. Fuel, 290, 120048. [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, Y., Kord, S., & Mashayekhizadeh, V. (2021). Application of machine learning techniques for selecting the most suitable enhanced oil recovery method; challenges and opportunities. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 205, 108761. [CrossRef]

- Choubineh, A., Helalizadeh, A., & Wood, D. A. (2019). Estimation of minimum miscibility pressure of varied gas compositions and reservoir crude oil over a wide range of conditions using an artificial neural network model. Advances in Geo-Energy Research, 3(1), 52–66. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, R. L., & Haines, H. K. (1987). Rapid Measurement of Minimum Miscibility Pressure With the Rising-Bubble Apparatus. SPE Reservoir Engineering, 2(04), 523–527. [CrossRef]

- Dargahi-Zarandi, A., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Shateri, M., Menad, N. A., & Ahmadi, M. (2020). Modeling minimum miscibility pressure of pure/impure CO2-crude oil systems using adaptive boosting support vector regression: Application to gas injection processes. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 184, 106499. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S. A. M., Sefti, M. V., Ameri, A., & Kaveh, N. S. (2008). Minimum miscibility pressure prediction based on a hybrid neural genetic algorithm. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 86(2), 173–185. 2. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S. A. M., Vafaie Sefti, M., Ameri, A., & Kaveh, N. S. (2006). A hybrid neural-genetic algorithm for predicting pure and impure CO 2 minimum miscibility pressure. In Iranian Journal of Chemical Engineering (Vol. 3, Issue 4). www.SID.ir.

- Ding, M., Yuan, F., Wang, Y., Xia, X., Chen, W., & Liu, D. (2017). Oil recovery from a CO2 injection in heterogeneous reservoirs: The influence of permeability heterogeneity, CO2-oil miscibility and injection pattern. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 44, 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Dong, P., Liao, X., Chen, Z., & Chu, H. (2019). An improved method for predicting CO2 minimum miscibility pressure based on artificial neural network. Advances in Geo-Energy Research, 3(4), 355–364. [CrossRef]

- Dong, P., Liao, X., Wu, J., Zou, J., Li, R., & Chu, H. (2020, October 25). A New Method for Predicting CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressure MMP Based on Deep Learning. SPE/IATMI Asia Pacific Oil & Gas Conference and Exhibition. 25 October. [CrossRef]

- Ekechukwu, G. K., Falode, O., & Orodu, O. D. (2020). Improved Method for the Estimation of Minimum Miscibility Pressure for Pure and Impure CO2–Crude Oil Systems Using Gaussian Process Machine Learning Approach. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 142(12). [CrossRef]

- Emera, M. K., & Sarma, H. K. (2005). Use of genetic algorithm to estimate CO2–oil minimum miscibility pressure—a key parameter in design of CO2 miscible flood. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 46(1–2), 37–52. [CrossRef]

- Emera, M. K., & Sarma, H. K. (2008). A Genetic Algorithm-Based Model to Predict CO-Oil Physical Properties for Dead and Live Oil. Journal of Canadian Petroleum Technology, 47(02). [CrossRef]

- Enab, K., & Ertekin, T. (2021). Screening and optimization of CO2 -WAG injection and fish-bone well structures in low permeability reservoirs using artificial neural network. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 200, 108268. [CrossRef]

- F. Al-Khafaji, H., Meng, Q., Hussain, W., Khudhair Mohammed, R., Harash, F., & Alshareef AlFakey, S. (2023). Predicting minimum miscible pressure in pure CO2 flooding using machine learning: Method comparison and sensitivity analysis. Fuel, 354, 129263. [CrossRef]

- Fathinasab, M., & Ayatollahi, S. (2016). On the determination of CO 2 –crude oil minimum miscibility pressure using genetic programming combined with constrained multivariable search methods. Fuel, 173, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M. M., Mohammadi, A. H., & Zendehboudi, S. (2021). Use of hybrid-ANFIS and ensemble methods to calculate minimum miscibility pressure of CO2 - reservoir oil system in miscible flooding process. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 331, 115369. [CrossRef]

- Ghoraishy, S. M., Liang, J. T., Green, D. W., & Liang, H. C. (2008, April 20). Application of Bayesian Networks for Predicting the Performance of Gel-Treated Wells in the Arbuckle Formation, Kansas. SPE Symposium on Improved Oil Recovery. 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Gozalpour, F., Ren, S. R., & Tohidi, B. (2005). CO2 EOR and Storage in Oil Reservoir. Oil & Gas Science and Technology, 60(3), 537–546. [CrossRef]

- Green, D. W., & Willhite, P. G. (1998). Enhanced oil recovery (Vol. 6). Henry L. Doherty Memorial Fund of AIME, Society of Petroleum Engineers.

- Haider, G., Khan, M. A., Ali, F., Nadeem, A., & Abbasi, F. A. (2022, October 31). An Intelligent Approach to Predict Minimum Miscibility Pressure of Injected CO2-Oil System in Miscible Gas Flooding. ADIPEC. 31 October. [CrossRef]

- Hamadi, M., El Mehadji, T., Laalam, A., Zeraibi, N., Tomomewo, O. S., Ouadi, H., & Dehdouh, A. (2023). Prediction of Key Parameters in the Design of CO2 Miscible Injection via the Application of Machine Learning Algorithms. Eng, 4(3), 1905–1932. 3. [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, Z., & Chenxi, D. (2019, October 21). Accurate Prediction of CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressure Using Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems. 21 October. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. M. F., First, E. L., Boukouvala, F., & Floudas, C. A. (2015). A multi-scale framework for CO2 capture, utilization, and sequestration: CCUS and CCU. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 81, 2–21. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A., Elkatatny, S., & Abdulraheem, A. (2019). Intelligent Prediction of Minimum Miscibility Pressure (MMP) During CO2 Flooding Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Sustainability, 11(24), 7020. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Li, W., & Qian, S. (2023). Minimum Miscibility Pressure Prediction Method Based On PSO-GBDT Model. Improved Oil and Gas Recovery. [CrossRef]

- Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Ghazanfari, M.-H., Ayatollahi, S., & Masihi, M. (2016). Accurate determination of the CO2-crude oil minimum miscibility pressure of pure and impure CO2 streams: A robust modelling approach. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 94(2), 253–261. [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. W., & Josendal, V. A. (1974). Mechanisms of Oil Displacement By Carbon Dioxide. Journal of Petroleum Technology, 26(12), 1427–1438. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh Helaleh, A., & Alizadeh, M. (2016). Performance prediction model of Miscible Surfactant-CO2 displacement in porous media using support vector machine regression with parameters selected by Ant colony optimization. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 30, 388–404. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z., Su, H., & Wang, G. (2022). Study on Minimum Miscibility Pressure of CO2–Oil System Based on Gaussian Process Regression and Particle Swarm Optimization Model. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 144(10). [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Tian, L., Wu, J., Li, M., Li, Z., Li, J., Wang, J., Jiang, L., & Yang, D. (2023). Prediction of minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) of the crude oil-CO2 systems within a unified and consistent machine learning framework. Fuel, 337, 127194. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Tian, L., Zhang, T., Chen, J., Wu, J., Wang, H., Wang, J., Jiang, L., & Zhang, K. (2022). Globally optimized machine-learning framework for CO2-hydrocarbon minimum miscibility pressure calculations. Fuel, 329, 125312. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., Wei, C., Li, B., Yang, J., Wu, S., Xu, X., Ou, Y., Xiong, L., Lou, Y., Li, Z., Deng, Y., & Zhang, C. (2021, December 9). Prediction and Optimization of WAG Flooding by Using LSTM Neural Network Model in Middle East Carbonate Reservoir. Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference. 9 December. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. F., Huang, G. H., Dong, M. Z., & Feng, G. M. (2003). Development of an artificial neural network model for predicting minimum miscibility pressure in CO2 flooding. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 37(1–2), 83–95. [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, U. P., & Kurihara, M. (2022). Time-Series Forecasting of a CO2-EOR and CO2 Storage Project Using a Data-Driven Approach. Energies, 15(13), 4768. [CrossRef]

- Iskandarov, J., Fanourgakis, G. S., Ahmed, S., Alameri, W., Froudakis, G. E., & Karanikolos, G. N. (2022). Data-driven prediction of in situ CO2 foam strength for enhanced oil recovery and carbon sequestration. RSC Advances, 12(55), 35703–35711. 5703. [CrossRef]

- Jaber, A. K., Alhuraishawy, A. K., & AL-Bazzaz, W. H. (2019, October 13). A Data-Driven Model for Rapid Evaluation of Miscible CO2-WAG Flooding in Heterogeneous Clastic Reservoirs. SPE Kuwait Oil & Gas Show and Conference. 13 October. [CrossRef]

- Junyu, Y., William, A., & Qian, S. (2021, October 19). Optimization of Water-Alternating-CO2 Injection Field Operations Using a Machine-Learning-Assisted Workflow. SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference. 19 October. [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A., Arabloo, M., Shokrollahi, A., Gharagheizi, F., & Mohammadi, A. H. (2015). Rapid method to estimate the minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) in live reservoir oil systems during CO 2 flooding. Fuel, 153, 310–319. [CrossRef]

- Karacan, C. Ö. (2020). A fuzzy logic approach for estimating recovery factors of miscible CO2-EOR projects in the United States. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 184, 106533. [CrossRef]

- Karkevandi-Talkhooncheh, A., Hajirezaie, S., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Husein, M. M., Karan, K., & Sharifi, M. (2017). Application of adaptive neuro fuzzy interface system optimized with evolutionary algorithms for modeling CO 2 -crude oil minimum miscibility pressure. Fuel, 205, 34–45. [CrossRef]

- Karkevandi-Talkhooncheh, A., Rostami, A., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Ahmadi, M., Husein, M. M., & Dabir, B. (2018). Modeling minimum miscibility pressure during pure and impure CO2 flooding using hybrid of radial basis function neural network and evolutionary techniques. Fuel, 220, 270–282. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R., Kalam, S., Abu-khamsin, S. A., & Asad, A. (2022, October 31). Machine Learning for Prediction of CO2 Foam Flooding Performance. ADIPEC. 31 October. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R., Kalam, S., Khan, R. A., Tariq, Z., & Abdulraheem, A. (2019, November 11). Comparative Analysis of Intelligent Algorithms to Predict the Minimum Miscibility Pressure for Hydrocarbon Gas Flooding. Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference. 11 November. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Augusto Sampaio, M., Ojha, K., Hoteit, H., & Mandal, A. (2022). Fundamental aspects, mechanisms and emerging possibilities of CO2 miscible flooding in enhanced oil recovery: A review. Fuel, 330, 125633. [CrossRef]

- Le Van, S., & Chon, B. H. (2017). Evaluating the critical performances of a CO2–Enhanced oil recovery process using artificial neural network models. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 157, 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Li, X., Zhang, Y., Sun, L., & Yuan, S. (2019). Four Methods to Estimate Minimum Miscibility Pressure of CO2-Oil Based on Machine Learning. Chinese Journal of Chemistry, 37(12), 1271–1278. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Gong, C., Liu, S., Xu, J., & Imani, G. (2022). Machine Learning-Assisted Prediction of Oil Production and CO2 Storage Effect in CO2-Water-Alternating-Gas Injection (CO2-WAG). Applied Sciences, 12(21), 10958. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Fu, X., Meng, L., Du, X., Zhang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Prediction of CO2 storage performance in reservoirs based on optimized neural networks. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, 222, 211428. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q., Zheng, R., Guo, X., Larestani, A., Hadavimoghaddam, F., Riazi, M., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Wang, K., & Li, J. (2023). Modelling minimum miscibility pressure of CO2-crude oil systems using deep learning, tree-based, and thermodynamic models: Application to CO2 sequestration and enhanced oil recovery. Separation and Purification Technology, 310, 123086. [CrossRef]

- Lv, W., Tian, W., Yang, Y., Yang, J., Dong, Z., Zhou, Y., & Li, W. (2021). Method for Potential Evaluation and Parameter Optimization for CO2 -WAG in Low Permeability Reservoirs based on Machine Learning. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 651(3), 032038. [CrossRef]

- Mahdaviara, M., Nait Amar, M., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Dai, Z., Zhang, C., Xiao, T., & Zhang, X. (2021). Toward smart schemes for modeling CO2 solubility in crude oil: Application to carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery. Fuel, 285, 119147. [CrossRef]

- Matthew, D. A. M., Jahanbani Ghahfarokhi, A., Ng, C. S. W., & Nait Amar, M. (2023). Proxy Model Development for the Optimization of Water Alternating CO2 Gas for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energies, 16(8), 3337. [CrossRef]

- Menad, N. A., & Noureddine, Z. (2019). An efficient methodology for multi-objective optimization of water alternating CO2 EOR process. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 99, 154–165. [CrossRef]

- Mohagheghian, E., James, L. A., & Haynes, R. D. (2018). Optimization of hydrocarbon water alternating gas in the Norne field: Application of evolutionary algorithms. Fuel, 223, 86–98. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S. R., Wood, D. A., Ahmadi, M. A., & Choubineh, A. (2019). ANN-Based Prediction of Laboratory-Scale Performance of CO2-Foam Flooding for Improving Oil Recovery. Natural Resources Research, 28(4), 1619–1637. [CrossRef]

- Nait Amar, M., Jahanbani Ghahfarokhi, A., Ng, C. S. W., & Zeraibi, N. (2021). Optimization of WAG in real geological field using rigorous soft computing techniques and nature-inspired algorithms. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 206, 109038. [CrossRef]

- Nait Amar, M., & Zeraibi, N. (2020). Application of hybrid support vector regression artificial bee colony for prediction of MMP in CO2-EOR process. Petroleum, 6(4), 415–422. [CrossRef]

- Nait Amar, M., Zeraibi, N., & Redouane, K. (2018). Optimization of WAG Process Using Dynamic Proxy, Genetic Algorithm and Ant Colony Optimization. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 43(11), 6399–6412. 11). [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, A. B., Mousavi, S. M., & Aghahoseini, S. (2011). Development of an artificial neural network model to predict CO 2 minimum miscibility pressure.

- Ng, C. S. W., Nait Amar, M., Jahanbani Ghahfarokhi, A., & Imsland, L. S. (2023). A Survey on the Application of Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Algorithms for Intelligent Proxy Modeling in Reservoir Simulation. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 170, 108107. [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, A., Jeong, H., Pyrcz, M., & Lake, L. W. (2018). Fast evaluation of well placements in heterogeneous reservoir models using machine learning. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 163, 463–475. [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, A., Jeong, H., Sun, A., Pyrcz, M., & Lake, L. W. (2018, April 14). Machine Learning-Based Optimization of Well Locations and WAG Parameters under Geologic Uncertainty. SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference. 14 April. [CrossRef]

- Orr, F. M., & Jensen, C. M. (1984). Interpretation of Pressure-Composition Phase Diagrams for CO2/Crude-Oil Systems. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal, 24(05), 485–497. [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q. C., Trinh, T. Q., & James, L. A. (2021, June 21). Data Driven Prediction of the Minimum Miscibility Pressure (MMP) Between Mixtures of Oil and Gas Using Deep Learning. Volume 1: Offshore Technology. 21 June. [CrossRef]

- Raha Moosavi, S., Wood, D. A., & Samadani, A. (2020). Modeling Performance of Foam-CO2 Reservoir Flooding with Hybrid Machine-learning Models Combining a Radial Basis Function and Evolutionary Algorithms. Computational Research Progress in Applied Science & Engineering CRPASE, 06(01), 1–8.

- Rao, D. N., & Lee, J. I. (2002). Application of the new vanishing interfacial tension technique to evaluate miscibility conditions for the Terra Nova Offshore Project. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 35(3–4), 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Rayhani, M., Tatar, A., Shokrollahi, A., & Zeinijahromi, A. (2023). Exploring the power of machine learning in analyzing the gas minimum miscibility pressure in hydrocarbons. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, 226, 211778. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M., Eftekhari, M., Schaffie, M., & Ranjbar, M. (2013). A CO2-oil minimum miscibility pressure model based on multi-gene genetic programming. Energy Exploration and Exploitation, 31(4), 607–622. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A., Arabloo, M., Kamari, A., & Mohammadi, A. H. (2017). Modeling of CO2 solubility in crude oil during carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery using gene expression programming. Fuel, 210, 768–782. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A., Arabloo, M., Lee, M., & Bahadori, A. (2018). Applying SVM framework for modeling of CO2 solubility in oil during CO2 flooding. Fuel, 214, 73–87. [CrossRef]

- Saeedi Dehaghani, A. H., & Soleimani, R. (2020). Prediction of CO2-Oil Minimum Miscibility Pressure Using Soft Computing Methods. Chemical Engineering & Technology, 43(7), 1361–1371. [CrossRef]

- Satter, A., & Thakur, G. C. (1994). Integrated petroleum reservoir management: a team approach.

- Sayyad, H., Manshad, A. K., & Rostami, H. (2014). Application of hybrid neural particle swarm optimization algorithm for prediction of MMP. Fuel, 116, 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Selveindran, A., Zargar, Z., Razavi, S. M., & Thakur, G. (2021). Fast Optimization of Injector Selection for Waterflood, CO2-EOR and Storage Using an Innovative Machine Learning Framework. Energies, 14(22), 7628. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M., Khan, M. R., Kalam, S., Khan, R. A., Patil, S., & Dar, U. A. (2023). Machine Learning for Prediction of CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressure. SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference, MEOS, Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B., Yang, S., Gao, X., Li, S., Yang, K., Hu, J., & Chen, H. (2023). Interpretable knowledge-guided framework for modeling minimum miscible pressure of CO2-oil system in CO2-EOR projects. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 118, 105687. [CrossRef]

- Shokir, E. M. E.-M. (2007a). CO2–oil minimum miscibility pressure model for impure and pure CO2 streams. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 58(1–2), 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Shokir, E. M. E.-M. (2007b). CO2–oil minimum miscibility pressure model for impure and pure CO2 streams. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 58(1–2), 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi, A., Arabloo, M., Gharagheizi, F., & Mohammadi, A. H. (2013). Intelligent model for prediction of CO2 – Reservoir oil minimum miscibility pressure. Fuel, 112, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G., Davudov, D., Al-Shalabi, E. W., Malkov, A., Venkatraman, A., Mansour, A., Abdul-Rahman, R., & Das, B. (2023, January 24). A Hybrid Neural Workflow for Optimal Water-Alternating-Gas Flooding. SPE Reservoir Characterization and Simulation Conference and Exhibition. 24 January. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, U., Dindoruk, B., & Soliman, M. (2023). Physics guided data-driven model to estimate minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) for hydrocarbon gases. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, 224, 211389. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, U., Dindoruk, B., & Soliman, M. (2020, August 30). Prediction of CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressure MMP Using Machine Learning Techniques. SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference. 30 August. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Ampomah, W., You, J., Cather, M., & Balch, R. (2021). Practical CO2—WAG Field Operational Designs Using Hybrid Numerical-Machine-Learning Approaches. Energies, 14(4), 1055. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, Z., Aljawad, M. S., Hasan, A., Murtaza, M., Mohammed, E., El-Husseiny, A., Alarifi, S. A., Mahmoud, M., & Abdulraheem, A. (2021). A systematic review of data science and machine learning applications to the oil and gas industry. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology, 11(12), 4339–4374. [CrossRef]

- Tarybakhsh, M. R., Assareh, M., Sadeghi, M. T., & Ahmadi, A. (2018). Improved Minimum Miscibility Pressure Prediction for Gas Injection Process in Petroleum Reservoir. Natural Resources Research, 27(4), 517–529. [CrossRef]

- Tatar, A., Shokrollahi, A., Mesbah, M., Rashid, S., Arabloo, M., & Bahadori, A. (2013). Implementing Radial Basis Function Networks for modeling CO2-reservoir oil minimum miscibility pressure. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 15, 82–92. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Ju, B., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Dong, Y., Liu, N., Ma, S., & Yu, J. (2020). Estimation of minimum miscibility pressure during CO2 flooding in hydrocarbon reservoirs using an optimized neural network. Energy Exploration & Exploitation, 38(6), 2485–2506. [CrossRef]

- Van, S. Le, & Chon, B. H. (2018). Effective Prediction and Management of a CO2 Flooding Process for Enhancing Oil Recovery Using Artificial Neural Networks. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 140(3). [CrossRef]

- Vo Thanh, H., Sheini Dashtgoli, D., Zhang, H., & Min, B. (2023). Machine-learning-based prediction of oil recovery factor for experimental CO2-Foam chemical EOR: Implications for carbon utilization projects. Energy, 278, 127860. [CrossRef]

- Vo Thanh, H., Sugai, Y., & Sasaki, K. (2020). Application of artificial neural network for predicting the performance of CO2 enhanced oil recovery and storage in residual oil zones. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 18204. 1. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Yao, Y., Luo, X., Daniel Adenutsi, C., Zhao, G., & Lai, F. (2023). A critical review on intelligent optimization algorithms and surrogate models for conventional and unconventional reservoir production optimization. Fuel, 350, 128826. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X., & Lee, K. J. (2020). Data-driven modeling to optimize the injection well placement for waterflooding in heterogeneous reservoirs applying artificial neural networks and reducing observation cost. Energy Exploration & Exploitation, 38(6), 2413–2435. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. (2021, September 15). Minimum Miscibility Pressure of Gas Injection in Unconventional Reservoirs. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. 15 September. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., Jiang, R., Li, X., & Jiang, Y. (2018, April 14). Evaluation of Polymer Flooding Performance Using Water-Polymer Interference Factor for an Offshore Oil field in Bohai Gulf: A Case Study. Day 5 Wed, April 18, 2018. 14 April. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., & Li, X. (2020). Modified Peng-Robinson equation of state for CO2/hydrocarbon systems within nanopores. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 84, 103700. [CrossRef]

- Yellig, W. F., & Metcalfe, R. S. (1980). Determination and Prediction of CO2 Minimum Miscibility Pressures (includes associated paper 8876 ). Journal of Petroleum Technology, 32(01), 160–168. [CrossRef]

- Yongmao, H., Zenggui, W., Binshan, J., Yueming, C., Xiangjie, L., & Petro, X. (2004, August 2). Laboratory Investigation of CO2 Flooding. Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition. 2 August. [CrossRef]

- You, J., Ampomah, W., Kutsienyo, E. J., Sun, Q., Balch, R. S., Aggrey, W. N., & Cather, M. (2019, June 3). Assessment of Enhanced Oil Recovery and CO2 Storage Capacity Using Machine Learning and Optimization Framework. SPE Europec Featured at 81st EAGE Conference and Exhibition. 3 June. [CrossRef]

- You, J., Ampomah, W., Morgan, A., Sun, Q., & Huang, X. (2021). A comprehensive techno-eco-assessment of CO2 enhanced oil recovery projects using a machine-learning assisted workflow. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 111, 103480. [CrossRef]

- You, J., Ampomah, W., & Sun, Q. (2020). Development and application of a machine learning based multi-objective optimization workflow for CO2-EOR projects. Fuel, 264, 116758. [CrossRef]

- You, J., Ampomah, W., Sun, Q., Kutsienyo, E. J., Balch, R. S., & Cather, M. (2019, September 23). Multi-Objective Optimization of CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Projects Using a Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Approach. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. 23 September. [CrossRef]

- You, J., Ampomah, W., Sun, Q., Kutsienyo, E. J., Balch, R. S., Dai, Z., Cather, M., & Zhang, X. (2020). Machine learning based co-optimization of carbon dioxide sequestration and oil recovery in CO2-EOR project. Journal of Cleaner Production, 260, 120866. [CrossRef]

- You, J., & Lee, K. J. (2022). Pore-Scale Numerical Investigations of the Impact of Mineral Dissolution and Transport on the Heterogeneity of Fracture Systems During CO2-Enriched Brine Injection. SPE Journal, 27(02), 1379–1395. [CrossRef]

- YOUSEF, A. M., KAVOUSI, G. P., ALNUAIMI, M., & ALATRACH, Y. (2020). Predictive data analytics application for enhanced oil recovery in a mature field in the Middle East. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 47(2), 393–399. [CrossRef]

- Zargar, G., Bagheripour, P., Asoodeh, M., & Gholami, A. (2015). Oil-CO2 minimum miscible pressure (MMP) determination using a stimulated smart approach. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 93(10), 1730–1735. [CrossRef]

- Zendehboudi, S., Ahmadi, M. A., Bahadori, A., Shafiei, A., & Babadagli, T. (2013). A developed smart technique to predict minimum miscible pressure-eor implications. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 91(7), 1325–1337. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z., & Carr, T. R. (2016). Application of mixed kernels function (MKF) based support vector regression model (SVR) for CO2–Reservoir oil minimum miscibility pressure prediction. Fuel, 184, 590–603. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. (2003) | ANN | N/A | N/A | Pure CO2 (TR, xvol, MWC5+, xint), impure CO2 (yH2S, yN2, yCH4, ySO2→Fimp) | ANN can predict MMP. | First applied ANN. ANN is better than other statistical models. | Need to separate pure CO2 and impure CO2. | 7 |

| Emera & Sarma (2005) | GA | N/A | N/A | TR, MWC5+, xvol/(yC1 + yH2S + yCO2 + yN2 + yC2-C4). | GA is best for predicting MMP and impurity factors. | First used GA. Limited input parameters (only 3 variables). | Pure CO2. MWC7+ only up to 268. | 7 |

| Dehghani et al. (2006) | GA | 55 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint. | GA is better than conventional methods. | Can predict pure and impure CO2. But limited input parameters and data points. | Limited input parameters and data points. | 6 |

| Shokir, (2007) | ACE | 45 | 50% train+ 50% test | TR, MWC5+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2-C4, xC1+N2, xint | Can predict relatively accurate MMP for pure and impure CO2. | Can predict pure and impure CO2. But very limited data points. It may have overfitting. | valid only for C1, N2, H2S, and C2–C4 contents in the injected CO2 stream. | 6 |

| Dehghani et al. (2008) | ANN-GA | 46 | N/A | TR, MWC5+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2-C4, xC1+N2, xint | GA-ANN is better than Shokir (2007), Emera and Sarma (2005). | It can be applied to both CO2 and natural gas streams. | Limited data points and only ANN architecture is tested. | 6 |

| Nezhad et al. (2011) | ANN | 179 | N/A | TR, xvol, MWC5+, yCO2, yvolatile, yintermediate | ANN is acceptable | Acceptable data points but not detailed explanations. | Local minima or overfitting | 8 |

| Shokrollahi et al. (2013) | LSSVM | 147 | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validate | TR, xvol, MWC5+, yCO2, yC1, yH2S, yN2, yC2-C5 | First applied LSSVM. | It can be used for both pure and impure CO2. Also applied outlier analysis | Valid only for the impurity contents of C1, N2, H2S, and C2-C5. | 8 |

| Tatar et al. (2013) | RBFN | 147 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC5+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2-C5, (xC1 + xN2)/(xC2-C4+ xH2S + xCO2) | Better than Emera and Sarma’s model. | Compared with almost all available empirical correlations. | Limited data points | 8 |

| Zendehboudi et al. (2013) | ANN-PSO | 350 | 71% train + 29% test | TR, xvol, MWC5+, yCO2, yC1, yH2S, yN2, yC2-C4 | ANN-PSO is best. | Though it has large datasets, but only suitable for fixed input parameters. | Only valid for specific conditions | 8 |

| Chen et al. (2013) | ANN | 83 | 70% train + 30% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol, xint, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, and yN2 | ANN provides the least errors. | May have overfitting. | Small datasets | 7 |

| Asoodeh et al. (2014) | CM (NN-SVR) | 55 | N/A | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yC2-C4, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, and yN2 | CM is better than NN and SVR. | Limited data points and may have overfitting. | Small datasets | 6 |

| Rezaei et al. (2013) | GP | 43 | N/A | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint | GP provides the best estimation. | Limited data points and may have overfitting. | Small datasets and only consider pure CO2. | 6 |

| Chen et al. (2014) | GA-BPNN | 85 | 75% train + 25% test | TR, MWC7+, xvol, xC5-C6, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2-C4, xint | Both pure and impure CO2, better than other correlations. | It can be applied to both pure and impure CO2 but may have overfitting. | Limited data points.GA is time-consuming. | 7 |

| Ahmadi & Ebadi (2014) | FL | 59 | 93% train + 7% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, TC | The curve shape membership function has the lowest error. | Limited data points and a high possibility of overfitting. | Only four experimental results for testing. | 6 |

| Sayyad et al. (2014) | ANN-PSO | 38 | N/A | TR, xvol, MWC5+, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2, yC2-C5 | Better than Emera and Sarma, Shokir. | Only valid for fixed inputs | Limited data points | 6 |

| Zargar et al. (2015) | GRNN | N/A | N/A | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yC2-C4, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, and yN2. | GRNN is an efficient computational structure. GA reduces the runs of GRNNs. | Though compared with most known correlations, but unknown about the data source. | Need more information about the treatment of data. | 6 |

| Kamari et al. (2015) | GEP | 135 | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validate | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, xC2-C4, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | GEP provides better prediction | First use GEP, compared with correlations. | AARD is a little high, at 10%. | 8 |

| Bian et al. (2016) | SVR-GA | 150 | 67% train + 23% test83% train + 17% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | Better than other empirical correlations | Can be used for pure and impure CO2 and low AARD. | Separate pure and impure CO2. | 9 |

| Hemmati-Sarapardeh et al. (2016) | MLP | 147 | 70% train + 15% test + 15% validate | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | Can predict both pure and impure CO2. | Simple and reliable. | Treatment of inputs may be too simple. | 8 |

| Zhong & Carr (2016) | MKF-SVM | 147 | 90% train + 10% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | The mixed kernel provides better performance. | Treatment of inputs may be too simple. | Did not consider the effect of N2, H2S. | 8 |

| Fathinasab & Ayatollahi (2016) | GP | 270 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, Tcm, MWC5+, xvol/xint | GP provides the best prediction. | Relatively large datasets but may simplify the inputs. | AARE is a little high (11.76%). | 7 |

| Alomair & Garrouch (2016) | GRNN | 113 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC5+, MWC7+, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xCO2, xH2S, xN2. | GRNN is better than five empirical correlations | Too many inputs and no further comparison between GRNN and other ML methods. | Does not consider the purity of CO2. | 7 |

| Karkevandi-Talkhooncheh et al. (2017) | ANFIS | 270 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol, xint | ANFIS-PSO is the best among the five optimization methods. | Very comprehensive comparison with available models and different optimizations. | Further applicability may be needed. | 9 |

| Ahmadi et al. (2017) | GEP | N/A | N/A | TR, Tcm, MWC5+, xvol/xint | GEP is better than traditional correlations. | Unknown about datasets. | Further validation may be needed. | 6 |

| Karkevandi-Talkhooncheh et al. (2018) | RBF-GA/ PSO/ICA/ACO/DE | 270 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol, xC2-C4, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | ICA-RBF is best | Comparable large datasets. Five algorithms were applied. | Further applicability may be needed. | 9 |

| Tarybakhsh et al. (2018) | SVR-GA, MLP, RBF, GRNN | 135 | 92.5% train + 7.5% test | TR, MWC2-C6 (OIL), MWC7+, SGC7+, MWC2-C6 (GAS), yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | SVT-GA is best. | Too many input parameters may cause a high possibility of overfitting. | The R2 is as high as 0.999. Too perfect to be reliable. | 6 |

| Dong et al. (2019) | ANN | 122 | 82% train + 18% test | H2S, CO2, N2, C1, C2… C36+ | ANN can be used to predict MMP. | Too many inputs. No dominant input selection. | Input variables were assumed based on theavailability of data. | 7 |

| Hamdi & Chenxi (2019) | ANFIS | 48 | 73% train + 27% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol, xint | Gaussian MF is the best among the five MFs. ANFIS is better than ANN. | Though applied five MF but limited data points. | Limited data points and does not consider the existence of CO2. | 6 |

| Khan et al. (2019) | ANN, FN, SVM | 51 | 70% train + 30% test | TR, MWC7+, xC1, xC2-C6, MWC2+, xC2 | ANN is best | Compared three methods but input parameters are overlapping. | Limited data points and does not consider the existence of CO2. | 6 |

| Choubineh et al. (2019) | ANN | 251 | 75% train + 10% test + 15% validate | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, SG | ANN is best compared with empirical correlations | Relatively large dataset. Use gas SG instead. | Further applicability may be needed. | 8 |

| Li et al. (2019) | NNA, GFA, MLR, PLS | 136 | N/A | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yC2-C5, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | ANN is best among both empirical and other algorithms. | Unclear about how to split the data. | Further applicability may be needed. | 8 |

| Hassan et al. (2019) | ANN, RBF, GRNN, FL | 100 | 70% train + 30% test | TR, MWC7+, xC2-C6 | RBF provides the highest accuracy. | Only three input parameters may simplify the model. | Does not consider the purity of CO2 and the limited dataset. | 7 |

| Sinha et al. (2020) | Linear SVM/KNN/RF/ANN | N/A | 67% train + 33% test | TR, MWC7+, MWOil, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xCO2, xH2S, and xN2. | Modified correlation with linear SVR and hybrid method with RF is best. | Only need oil composition and TR. Does not consider the purity of CO2. | MMP range 1000 - 4900 pis. | 7 |

| Nait Amar & Zeraibi (2020) | SVR-ABC | 201 | 87% train + 13% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint, xC2-C4 | SVR-ABC is better SVR-TE | The choice of inputs is limited | Limited comparison. | 8 |

| Dargahi-Zarandi et al. (2020) | AdaBoost SVR, GDMH, MLP | 270 | 67% train + 33% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol, xC2-C4, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | AdaBoost SVR is best. | Create a 3-D plot for better visualization. | Further applicability was limited | 9 |

| Tian et al. (2020) | BP-NN (GA, MEA, PSO, ABC, DA) | 152 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC5+, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2. | DA-BP has the highest accuracy. | Compared with empirical correlations and GA-SVR. | Too many input parameters may have overfitting. | 8 |

| Ekechukwu et al. (2020) | GPR | 137 | 90% train + 10% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | GPR has higher accuracy than other models. | Very comprehensive comparison. A larger dataset may be better. | Further validation with experiments may be needed. | 8 |

| Saeedi Dehaghani & Soleimani (2020) | SGB, ANN, ANN-PSO, ANN-TLBO | 144 | 75% train + 25% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol, xint, yCO2, yC1, yint, yN2. | PSO and TLBO can help improve the accuracy of the ANN model. SGB is better than ANN. | First applied SGB. Maybe compared with other optimization methods will be better. | Further validation with experiments may be needed. | 8 |

| Dong et al. (2020) | FCNN | 122 | 82% train + 18% test | xCO2, xH2S, xN2, xC1, xC2,xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6,…,xC36+. | L2 regularization and Dropout can help reduce overfitting. | Alleviate overfitting but small datasets. | Small datasets. | 7 |

| Chen et al. (2021) | SVM | 147 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC7+, xvol, xC2-C4, xC5-C6, yCO2, yHC, yC1, and yN2. | POLY kernel is more accurate. MWC7+ and xC5-C6 should not be considered. | Very complete and comprehensive. Includes optimization and evaluation. | More persuasive with a large dataset. | 9 |

| Ghiasi et al. (2021) | ANFIS, AdaBoost-CART | N/A | 90% train + 10% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yCO2, yH2S, yC1-C5, and yN2 | The novel AdaBoost-The CART model is the most reliable. | The size of the dataset is unknown. First one to use AdaBoost. | May have overfitting and validation is not strong. | 7 |

| Chemmakh et al. (2021) | ANN, SVR-GA | 147 (pure CO2), 200 (impure CO2) | NA | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | ANN and SVR-GA are reliable to use. | The novelty of work is not clear. | Only compared with empirical correlations. | 7 |

| Pham et al. (2021) | FCNN | 250 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, xvol/xint, MW, yC1, yC2+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2 | Multiple FCN together with Early Stopping and K-fold cross validation has high prediction of MMP. | Applied deep learning – multiple FCN to predict MMP. Limited comparisons and validations. | Only compared with decision tree and random forest. | 7 |

| Haider et al. (2022) | ANN | 201 | 70% train + 30% test | TR, MWC7+, xCO2, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yN2. | An empirical correlation is developed based on ANN. | Too many inputs and a high possibility of overfitting. | Need further validation with other reservoir fluid and injected gas. | 7 |

| Huang et al. (2022) | CGAN-BOA | 180 | 60% train + 20% test + 20% validate | TR, MWC7+, xCO2, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xN2, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2, yC3, yC4, yC5, yC6, yC7+. | CGAN-BOA and ANN are better than SVR-RBF and SVR-POLY | Proved deep learning has the potential for predicting MMP. | May have overfitting problems given 21 input parameters. | 8 |

| He et al. (2023) | GBDT-PSO | 195 | 85% train + 15% test | TR, xCO2, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xN2, | GBDT is better than LR, RR, RF, MLP | Improved GBDT by using PSO. But not a comprehensive comparison. | Only GBDT was optimized. Other algorithms could also be tuned and compared. | 7 |

| Hou et al. (2022) | GPR-PSO | 365 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yC2-C5, yN2. | GPR-PSO provides the highest accuracy. | Comprehensive comparison and large datasets. | The model was only validated with literature data. | 9 |

| Rayhani et al. (2023) | SFS, SBS, SFFS, SBFS, LR, RFFI | 812 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, TC, MWC7+, MWgas, xC5, xC6, xC2-C6 | SBFS provides the highest accuracy | Large datasets. Comprehensive data selection and model comparison. | Further applicability with field data or commercial simulation was limited. | 9 |

| Shakeel et al. (2023) | ANN, ANFIS | 105 | 70% train + 30% test | TR, MWC7+, xvol, xC2-C4, xC5-C6, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yHC, yN2. | ANN is better than ANFIS; the trainlm performs best. | Demonstrated good accuracy but lack of uncertainty analysis. | Limited dataset and only two ML algorithms were tested. | 7 |

| Shen et al. (2023) | XGBoost, TabNet, KXGB, KTabNet | 421 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC5+, xvol/xint, yCO2, yH2S, yC1, yC2-C5, yHC, and yN2 | KXGB is best. KTabNet can be used as an alternative. | Large datasets. Comprehensive model comparison. New insights into deep learning. | Need improvement of feature comprehensiveness. | 9 |

| Lv et al. (2023) | XGBoost, CatBoost, LGBM, RF, deep MLN, DBN, CNN | 310 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | CatBoost outperforms than other AI techniques. | Comprehensive model comparison and evaluation. New insights into deep learning. | The accuracy depends on the databank. A larger dataset will be more robust. | 9 |

| Hamadi et al. (2023) | MLP-Adam, SVR-RBF, XGBoost | 193 | 84% train + 16% test | TR, TC, MWC5+, xvol/xint | XGBoost provides the best prediction for both pure and impure CO2. | Not comprehensive comparison and a limited dataset. | Limited dataset and only two ML algorithms were tested | 7 |

| Huang et al. (2023) | 1D-CNN, SHAP | 193 | NA | TR, MWC7+, xCO2, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xN2, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2, yC3, yC4, yC5, yC6, yC7+. | MMPs from the slim tube and rising bubble are different. 1D-CNN performs best. | It is novel in the SHAP application, but the comparison with other ML models is limited. | Further applicability with field data or commercial simulation was limited. | 8 |

| Al-Khafaji et al. (2023) | MLR, SVR, DT, RF, KNN | 147 (type 1), 197 (type 2), 28 (type 3) | 80% train + 20% test | Type 1: TR, MWC5+, xvol/xintType 2: MWC7+, xvol, xint, xC5-C6, xC7+, yCO2, yH2S, yN2, yC1, yC2-C6, yC7+.Type 3: TR, MWC6+, xvol, xint, xC6+, API, sp.gr, Pb. | KNN has the highest efficient accuracy and lowest complexity. | Have a broad range of data including both experimental and field data. Performed thorough comparisons. | Only pure CO2. | 9 |

| Sinha et al. (2023) | Light GBM | 205 | 80% train + 20% test | TR, MWC7+, MWOil, xC1, xC2, xC3, xC4, xC5, xC6, xC7+, xCO2, xH2S, xN2. | An expanded range is developed with Light GBM. | Compared with empirical and EOS correlations. First used Light GBM in MMP prediction. | Further applicability with field data or commercial simulation was limited. | 8 |

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampomah et al. (2017) | GA | NA | NA | Oil recover + CO2 storage | NA | The proxy models to determine the optimal operational parameters, including injection/production rates, pressure, and WAG cycles | First used proxy models and GA to optimize oil recovery and CO2 storage simultaneously. But relies heavily on having an accurate reservoir mode. | Optimal parameters are specific to this reservoir - and not necessarily generalizable. | 7 |

| You, Ampomah, Sun, et al. (2019) | RBFNN | 160 | N/A | Cumulative oil production + CO2 storage + NPV | water cycle, gas cycle, BHP of producer, water injection rate | The proxy model is built based on RBFNN for optimization. | The overall prediction is acceptable, but the CO2 storage prediction is much higher. | The CO2 storage optimization is 18% higher than the baseline. | 7 |

| You, Ampomah, Kutsienyo, et al. (2019) | ANN-PSO | 820 (numerical model) | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validation | Cumulative oil production + CO2 storage + NPV | water cycle, gas cycle, BHP of producer, water injection rate | The optimization study showed promising results for multiple objectives. | Developed a novel hybrid optimization for multiple objective functions. But only validated with field case. | Only four input parameters are considered. | 7 |

| Vo Thanh et al. (2020) | ANN-PSO | 351 (numerical model) | 80% train + 10% test + 10% validation | Cumulative oil production + cumulative CO2 storage +cumulative CO2 retained | ϕ, k, Sorg, Sorw, BHP of producer, CO2 injection rate | ANN can forecast the performance of CO2 EOR and storage in a residual oil zone | The ANN provides R2 of 0.99 and MSE of less than 2%, but the application in other types of reservoirs is questionable. | Case specific. | 7 |

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emera & Sarma (2008) | GA | 106 (dead oil), 74 (live oil) | NA | CO2 solubility, oil swelling factor, CO2-oil density, and viscosity. | API, Ps, T, MW | The GA-base correlations provided the highest accuracy | First applied GA in CO2-oil properties prediction. Will be more helpful if a full dataset is provided. | Validated over a certain data range. May not be reliable if it is out of data range. | 8 |

| Rostami et al. (2017) | ANN, GEP | 106 (dead oil), 74 (live oil) | 80% train + 20% test | CO2 solubility | Ps, T, MW, γ, Pb | GEP is more accurate than ANN for dead oil. | Compared with several empirical methods. More comparisons between ML models will be more persuasive. | Limited dataset on live oil. | 8 |

| Rostami et al. (2018) | LSSVM | 106 (dead oil), 74 (live oil) | 70% train + 15% test + 15% validation | CO2 solubility | Ps, T, MW, γ | LSSVM showed higher accuracy compared to previous empirical correlations. | More rigorous validation against experimental data equations of state models would be useful. | Only a few literature models were compared. | 7 |

| Mahdaviara et al. (2021) | MLP, RBF (GA, DE, FA), GMDH | NA | NA | CO2 solubility | Ps, T, MW, γ, Pb | MLP-LM and MLP-SCG are better at predicting solubility. GMDH is better than LSSVM. | Compared with various models and optimization methods. But unknown for the dataset. | Not known for the dataset. | 8 |

| Hamadi et al. (2023) | MLP-Adam, SVR-RBF, XGBoost | 105 (dead oil), 74 (live oil) | 80% train + 20% test | CO2 solubility, IFT | Ps, T, MW, γ, Pb | SVR-RBF provided the best accuracy | Limited comparisons between different models. | Given the year that this paper was published, the dataset is small. | 7 |

| Authors | Methods | Dataset | Train/Test/Validate | Objectives | Inputs | Results | Evaluation | Limitations | Rating* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moosavi et al. (2019) | MLP, RBF (GA, COA) | 214 | 80% train + 20% test75% train + 25% test90% train + 10% test | Oil flow rate and recovery factor | Surfactant kind, ϕ, K, PV of core, Soi, injected foam PV | Both MLP and RBF provide high accuracy with R2 up to 0.99. | The earliest research on CO2-foam EOR. Only focus on laboratory data. | Only studied two methods, and there was no comparison among other ML algorithms. | 8 |

| Raha Moosavi et al. (2020) | RBF (TLBO, PSO, GA, ICA) | 214 | 80% train + 20% test | Oil flow rate and recovery factor | Surfactant kind, ϕ, K, PV of core, Soi, injected foam PV | RBF-TLBO provides the highest accuracy. | Proved ML can provide high accuracy (R2 can reach 0.999), but is only limited to coreflood. | Limited to laboratory experiments. | 8 |

| Iskandarov et al. (2022) | DT, RF, ERT, GB, XGBoost, ANN | 145 | 70% train + 30% test | Surfactant stabilized CO2 apparent foam viscosity | Shear rate, Darcy velocity, surfactant concentration, salinity, foam quality, T, and pressure | ML can provide reliable prediction, and ANN provides the highest accuracy. | Proved ML can predict for both bulk and sandstone formation under various conditions. | The dataset size is relatively small and may have overfitting. | 8 |

| Khan et al. (2022) | XGBoost | 200 | 70% train + 30% test | Oil recovery factor | Foam type, Soi, total PV tested, ϕ, K, injected foam PV | XGBoost can provide high accuracy. | Proved XGBoost can be used for CO2-foam. Limited to laboratory data. | Only one ML is applied. No other comparisons. | 7 |

| Vo Thanh et al. (2023) | GRNN, CFNN-LM, CFNN-BR, XGBoost | 260 | 70% train + 30% test | Oil recovery factor | IOIP, TPVT, ϕ, K, injected foam PV | Porosity is the most significant parameter. GRNN has the highest accuracy. | Comprehensive and detailed description. | Limited to laboratory experiments. | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).