Submitted:

15 February 2024

Posted:

16 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire of the Study

2.3. Sampling Procedure and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

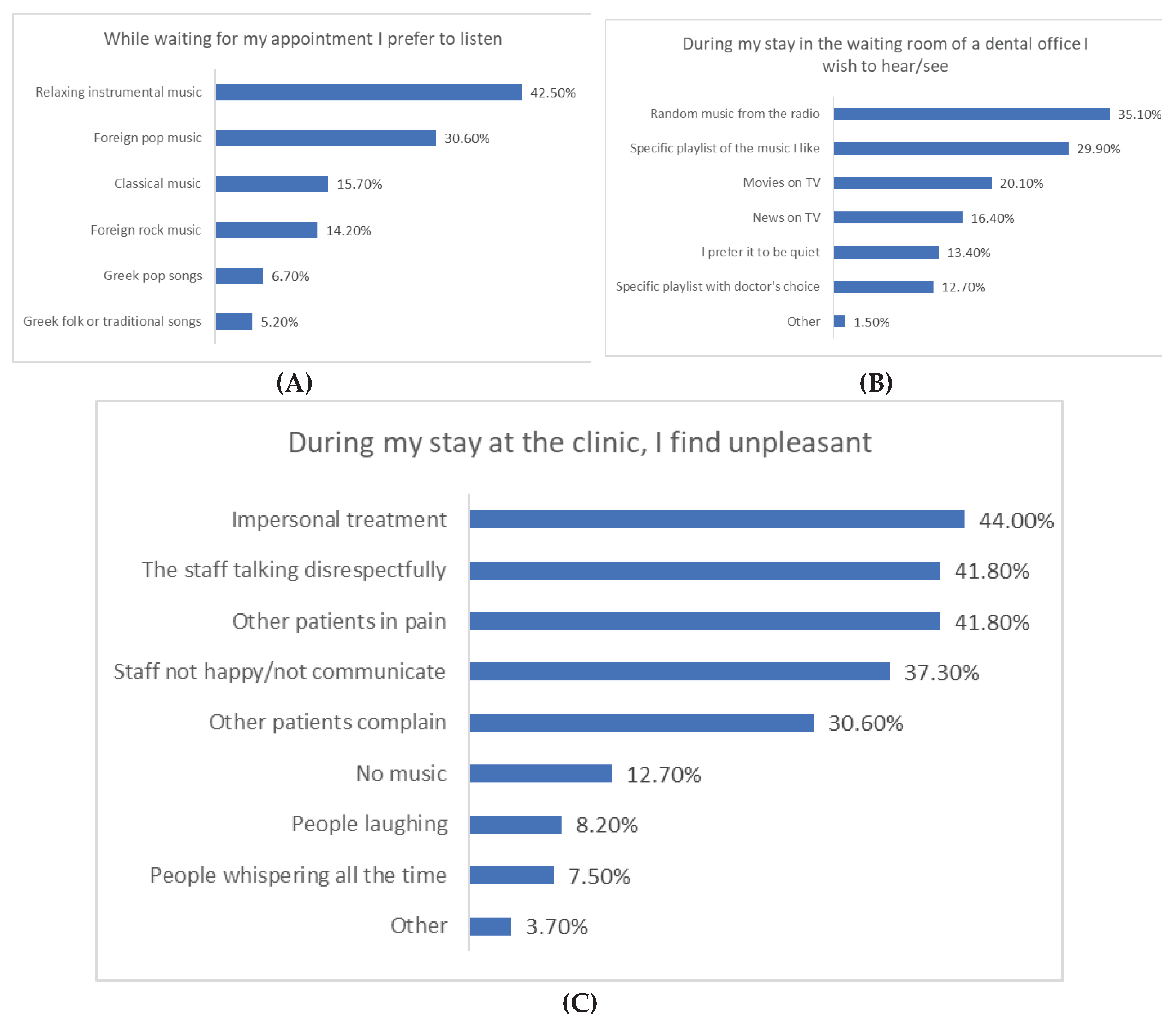

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study Questionnaire.

References

- Shetty, R.; Shoukath, S.; Shetty, S.K.; Dandekeri, S.; Shetty, N.H.G.; Ragher, M. Hearing Assessment of Dental Personnel: A Cross-sectional Exploratory Study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12 (Suppl 1), S488–S494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muppa, R.; Bhupatiraju, P.; Duddu, M.; Penumatsa, N.V.; Dandempally, A.; Panthula, P. Comparison of anxiety levels associated with noise in the dental clinic among children of age group 6-15 years. Noise Health. 2013, 15, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, P.D.; Rouw, R. How everyday sounds can trigger strong emotions: ASMR, misophonia and the feeling of wellbeing. Bioessays. 2020, 42, e2000099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlmann, A.Y.R. The Sound of Medicine: Evidence-Based Music Interventions in Healthcare Practice; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hartland, J.C.; Tejada, G.; Riedel, E.J.; Chen, A.H.; Mascarenhas, O.; Kroon, J. Systematic review of hearing loss in dental professionals. Occup Med (Lond). 2023, 73, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Tziovara, P.; Antoniadou, C. The Effect of Sound in the Dental Office: Practices and Recommendations for Quality Assurance-A Narrative Review. Dent J (Basel). 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.T.; Cheuk Ming, M.; Hai, W. Noise level and its influences on dental professionals in a dental hospital in Hong Kong. Building Service Engineering. 2017, 38, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Tziovara, P.; Konstantopoulou, S. Evaluation of Noise Levels in a University Dental Clinic. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jue, K.; Nathan-Roberts, D. How Noise Affects Patients in Hospitals. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 2019, 63, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.; Melmed, R.N.; Sgan-Cohen, H.D.; Eli, I.; Parush, S. Behavioural and physiological effect of dental environment sensory adaptation on children's dental anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007, 115, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appukuttan, D.P. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wide, U.; Hakeberg, M. Treatment of Dental Anxiety and Phobia-Diagnostic Criteria and Conceptual Model of Behavioural Treatment. Dent J (Basel). 2021, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscough, S.L.; Windsor, L.; Tahmassebi, J.F. A review of the effect of music on dental anxiety in children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2019, 20, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, U. The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: a systematic review. AORN J. 2008, 87, 780–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hawkins, J. Effects of music listening to reduce preprocedural dental anxiety in special needs patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021, 42, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomens, P.; Fu, V.X.; Kleinrensink, G.J.; Jeekel, J. The effect of music on simulated surgical performance: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2019, 33, 2774–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, M.L.; Puli, S.R.; Othman, M.O.; Bartalos, C.R.; Marshall, J.B.; Roy, P.K. Effect of music on patients undergoing colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2009, 54, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazzan, M.; Estaitia, M.; Habrawi, S.; Mansour, D.; Jalal, Z.; Ahmed, H.; Hasan, H.A.; Al Kawas, S. The Effect of Music Therapy in Reducing Dental Anxiety and Lowering Physiological Stressors. Acta Biomed. 2022, 92, e2021393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packyanathan, J.S.; Lakshmanan, R.; Jayashri, P. Effect of music therapy on anxiety levels on patient undergoing dental extractions. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019, 8, 3854–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, J.; Teague, A. Music interventions for dental anxiety. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapicak, E.; Dulger, K.; Sahin, E.; Alver, A. Investigation of the effect of music listened to by patients with moderate dental anxiety during restoration of posterior occlusal dental caries. Clin Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 3521–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullmann, Y.; Fodor, L.; Schwarzberg, I.; Carmi, N.; Ullmann, A.; Ramon, Y. The sounds of music in the operating room. Injury. 2008, 39, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiderscheit, A.; Breckenridge, S.J.; Chlan, L.L.; Savik, K. Music preferences of mechanically ventilated patients participating in a randomized controlled trial. Music Med. 2014, 6, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehfeldt, R.A.; Tyndall, I.; Belisle, J. Music as a Cultural Inheritance System: A Contextual-Behavioral Model of Symbolism, Meaning, and the Value of Music. Behav. Soc. Iss. 2021, 30, 749–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corah, N.L.; Gale, E.N.; Pace, L.F.; Seyrek, S.K. Relaxation and musical programming as means of reducing psychological stress during dental procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981, 103, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, JC.; Amaladoss, N. Music in Waiting Rooms: A Literature Review. HERD. 2022, 15, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.A.; Emard, N.; Liou, K.T.; Popkin, K.; Borten, M.; Nwodim, O.; Atkinson, T.M.; Mao, J.J. Patient Perspectives on Active vs. Passive Music Therapy for Cancer in the Inpatient Setting: A Qualitative Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021, 62, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the music. Available online: https://www.savethemusic.org/blog/music-therapy-and-mental-health/ (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Very Well Mind. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/music-and-personality-2795424 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Davies, C.; Page, B.; Driesener, C. The power of nostalgia: Age and preference for popular music. Mark Lett. 2022, 33, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentfrow, P.J.; Goldberg, L.R.; Levitin, D.J. The structure of musical preferences: a five-factor model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011, 2011 100, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Sánchez, N.; Pastor, R.; Eerola, T.; Escrig, M.; Pastor, M. Musical preference but not familiarity influences subjective ratings and psychophysiological correlates of music-induced emotions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2022, 198, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, H.; Hajj, E.; Fares, Y.; Abou-Abbas, L. Assessment of dental anxiety and dental phobia among adults in Lebanon. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California, Berkeley. Health Assessment of Noise Exposure Update Questionnaire chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://uhs.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/noiseexposure.pdf.

- Kankaala, T.; Kaakinen, P.; Anttonen, V. Self-reported factors for improving patient's dental care: A pilot study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022, 8, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokitulppo, J.; Toivonen, M.; Björk, E. Estimated leisure-time noise exposure, hearing thresholds, and hearing symptoms of Finnish conscripts. Mil Med. 2006, 171, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.A.; Cooper, S.; Stamper, G.C.; Chertoff, M. Noise Exposure Questionnaire: A Tool for Quantifying Annual Noise Exposure. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017, 28, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics Ed. 5. SAGE Publications, 2017.

- Vreman, J.; Lemson, J.; Lanting, C.; van der Hoeven, J.; van den Boogaard, M. The Effectiveness of the Interventions to Reduce Sound Levels in the ICU: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Explor. 2023, 5, e0885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.C.D.S.; Calache, A.L.S.C.; Oliveira, E.G.; Nascimento, J.C.D.; Silva, N.D.D.; Poveda, V.B. Noise reduction in the ICU: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2022, 20, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Tan, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, M. The dual effect of background music on creativity: perspectives of music preference and cognitive interference. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1247133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kweon, K.; Kim, H.W.; Cho, S.W.; Park, J.; Sim, C.S. Negative impact of noise and noise sensitivity on mental health in childhood. Noise Health. 2018, 20, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, H. A Conceptual Model of the Healthy Acoustic Environment: Elements, Framework, and Definition. Front. Psychol., 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletta, F.; Kang, J. Promoting Healthy and Supportive Acoustic Environments: Going beyond the Quietness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S.E.; Baguley, D.M.; Denys, D.; Dixon, L.J.; Erfanian, M.; Fioretti, A.; Jastreboff, P.J.; Kumar, S.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Rouw, R.; Schiller, D.; Simner, J.; Storch, E.A.; Taylor, S.; Werff, K.R.V.; Altimus, C.M.; Raver, S.M. Consensus Definition of Misophonia: A Delphi Study. Front Neurosci. 2022, 16, 841816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, M.V.; La Marca, R.; Brönnimann, R.; Finkel, L.; Ehlert, U.; Nater, U.M. The effect of music on the human stress response. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Witte, M.; Pinho, A.D.S.; Stams, G.J.; Moonen, X.; Bos, A.E.R.; van Hooren, S. Music therapy for stress reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2022, 16, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harney, C.; Johnson, J.; Bailes, F.; Havelka, J. Is music listening an effective intervention for reducing anxiety? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Musicae Scientiae. 2022, 27, 278–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Devetziadou, M. Sensory Branding: A New Era in Dentistry. Online J Dent Oral Health. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetziadou, M.; Antoniadou, M. Branding in dentistry: A historical and modern approach to a new trend. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews. 2020, 3, 051–068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissinger, M. Disrespectful Behavior in Health Care: Its Impact, Why It Arises and Persists, And How to Address It-Part 2. P T. 2017, 42, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, A.; Darvishi, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Sayehmiri, K. Gender differences in cognitive performance and psychophysiological responses during noise exposure and different workloads. Applied Acoustics. 2022, 189, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Heinonen-Guzejev, M.; Hautus, M.J.; Heikkilä, K. Elucidating the relationship between noise sensitivity and personality. Noise Health. 2015, 17, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Welch, D.; Dirks, K.N.; Mathews, R. Exploring the relationship between noise sensitivity, annoyance and health-related quality of life in a sample of adults exposed to environmental noise. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010, 7, 3579–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodersen, K.; Hammami, N.; Katapally, T.R. Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines. Youth 2022, 2, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaughan, D.J.; Oloruntoba, O.; Smith, M.L. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front Public Health. 2020, 18, 8:231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lercher, P.; Evans, G.W.; Meis, M. Ambient Noise and Cognitive Processes among Primary Schoolchildren. Environment and Behavior, 2003, 35, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatte, M.; Bergström, K.; Lachmann, T. Does noise affect learning? A short review on noise effects on cognitive performance in children. Front Psychol. 2013, 30, 4:578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Beckman, E.; Broughton, M.; Bunzli, E.; Davidson, R.; Draper, G.; Fairley, S.; Farrell, C.; Flynn, L.M.; Gomersall, S.; Hong, M.; Larwood, J.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.; Nitschinsk, L.; Peluso, N.; Reedman, S.E.; Vidas, D.; Walter, Z.C.; Wright, O.R.L. How Do Music Activities Affect Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Psychosocial Mechanisms. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 713818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Gao, S.; Huang, J. Learning About Your Mental Health From Your Playlist? Investigating the Correlation Between Music Preference and Mental Health of College Students. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 824789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.E.; Scott, W.G.; Flynn, S.; Foong, B.; Goh, K.; Wake, S.; Miller, D.; Garvey, D. Listening to music to cope with everyday stressors. Musicae Scientiae. 2023, 27, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Tsutani, K.; Yamada, M.; Park, H.; Okuizumi, H.; Tsuruoka, K.; Honda, T.; Okada, S.; Park, S.J.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T.; Handa, S.; Oshio, T.; Mutoh, Y. Effectiveness of music therapy: a summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials of music interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014, 8, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.S.; Sledge, R.B.; Fuller, L.A.; Daggy, J.K.; Monahan, P.O. Cancer patients' interest and preferences for music therapy. J Music Ther. 2005, 42, 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H. Analysis of the value of folk music intangible cultural heritage on the regulation of mental health. Front Psychiatry. 2023, 14, 1067753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Qi, N.; Long, H.; Yang, S. The impact of national music activities on improving long-term care for happiness of elderly people. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 1009811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Questionnaire Parts | Questions | Number of Questions | Scales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part I: Demographic information | Gender; age; educational level; clinic of attendance; duration of treatment | 5 | Nominal, Multiple choice |

| Part II: Acoustic health | Diagnosis of hearing loss; sensitivity to noise | 2 | Multiple choice data |

| Part III: Discomfort in dental clinic | Irritation by crowded environment, irritation by noise generated by suction devices, handpieces, ultrasonic scaler data | 2 including 6 subquestions in total | 5-point Likert scale, multiple choice |

| Part IV: Patient’s preferences | Preferences regarding audiovisual content and music in the waiting room, People’s behavior in the office data | 2 including 2 subquestions in total | Multiple choice |

| Part V: Hobbies and habits | Hobbies, music devices, listening habits | 8 including 1 subquestion | Nominal, Multiple choice |

| Part VI: General health | General health, interest in the effect of sound on health | 2 | Multiple choice |

| Part VII: Dental experience | Enhancement of dental experience, concerns regarding noise within the dental practice | 2 | Open-ended |

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 58 | 43.3% | |

| Female | 76 | 56.7% | ||

| Age | 20-30 y | 33 | 24.6% | |

| 31-40 y | 30 | 22.4% | ||

| 41-50 y | 22 | 16.4% | ||

| 51-60 y | 32 | 23.9% | ||

| >60 y | 17 | 12.7% | ||

| Education | Secondary | 57 | 42.5% | |

| Post-secondary | 24 | 17.9% | ||

| University | 53 | 39.6% | ||

| Medical center | University undergraduate clinic | 29 | 21.6% | |

| University postgraduate clinic | 26 | 19.4% | ||

| Private dental clinic up to 2 seats | 36 | 26.9% | ||

| Private dental clinic over 2 seats | 43 | 32.1% | ||

| Duration of therapy | 1-3 months | 28 | 20.9% | |

| 4-8 months | 36 | 26.9% | ||

| 9-12 months | 36 | 26.9% | ||

| 12 months or more | 34 | 25.4% | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 6 | 4.5% | |

| No | 124 | 92.5% | ||

| N/A | 4 | 3.0% | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Not at all | 34 | 25.4% | |

| Somewhat | 76 | 56.7% | ||

| Sensitive/ Very sensitive | 24 | 17.9% | ||

| Health status [M(SD)] | 3.84(0.95) | |||

| Noise disturbance from patients or staff [M(SD)] | 2.11(1.62) | |||

| Noise disturbance from machines [M(SD)] | 2.28(0.92) | |||

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of devices used to play music | Headphones | 55 | 41.0% |

| TV | 29 | 21.6% | |

| Radio | 66 | 49.3% | |

| Smartphones | 47 | 35.1% | |

| Other | 12 | 9.0% | |

| Volume on audio/video player | Very low | 2 | 1.5% |

| Low | 21 | 15.7% | |

| Neither low nor high | 59 | 44.0% | |

| High | 40 | 29.9% | |

| Very high | 11 | 8.2% | |

| Others get annoyed at how loud I listen to music | 1 | 0.7% | |

| Peak volume of voice in noisy environment | Very low | 2 | 1.5% |

| Low | 19 | 14.2% | |

| Neither low nor high | 49 | 36.6% | |

| High | 47 | 35.1% | |

| Very high | 12 | 9.0% | |

| Others are annoyed by the volume of my voice | 5 | 3.7% | |

| Perception of external sounds while using the music player | Bad | 7 | 5.2% |

| Moderate | 34 | 25.4% | |

| Neutral | 31 | 23.1% | |

| Good | 35 | 26.1% | |

| Very good | 24 | 17.9% | |

| Excellent | 3 | 2.2% | |

| Total time spent using music players per day | 0-30 min | 30 | 22.4% |

| 30-60 min | 29 | 21.6% | |

| 1-2 h | 38 | 28.4% | |

| 2-3 h | 18 | 13.4% | |

| 3-4 h | 12 | 9.0% | |

| over 4 hours | 7 | 5.2% | |

| Hours of continuous use of music player per day | 0-30 min | 44 | 32.8% |

| 30-60 min | 38 | 28.4% | |

| 1-2 h | 36 | 26.9% | |

| 2-3 h | 7 | 5.2% | |

| 3-4 h | 5 | 3.7% | |

| over 4 hours | 4 | 3.0% | |

| Attend live concerts | Never | 43 | 32.1% |

| 1-2 times/year | 62 | 46.3% | |

| 3-4 times/year | 15 | 11.2% | |

| 4-5 times/year | 6 | 4.5% | |

| 5 times/year or more | 8 | 6.0% | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender (Female vs Male) | -- | ||||||||||

| 2 | Clinic type (Private vs University clinic) | 0.067 | -- | |||||||||

| 3 | Age | 0.061 | -.355** | -- | ||||||||

| 4 | Education | 0.019 | .374** | -.690** | -- | |||||||

| 5 | Duration of therapy | 0.111 | -0.01 | -0.087 | 0.055 | -- | ||||||

| 6 | Noise sensitivity | .220* | -0.051 | .194* | -0.082 | 0.025 | -- | |||||

| 7 | Health status | -.176* | -.237** | -0.139 | 0.082 | -0.093 | 0.025 | -- | ||||

| 8 | Noise disturbance from machines | 0.097 | -0.133 | 0.078 | -.185* | -0.067 | .438** | 0.097 | -- | |||

| 9 | Noise disturbance from patients or staff | -0.09 | .235** | -0.068 | 0.096 | -0.099 | 0.135 | -0.089 | .249** | -- | ||

| 10 | Feeling irritated, anxious or nervous because of the mobility in the clinic | 0.035 | -.215* | 0.162 | -0.093 | -0.093 | .427** | 0.058 | .542** | .208* | -- | |

| 11 | Feeling anxious due to ambient noise from people and machines | -0.024 | -.174* | 0.147 | -0.131 | -0.066 | .399** | 0.104 | .662** | .254** | .680** | -- |

| Health Status | Noise Disturbance from Machines | Noise Disturbance from Patients or Staff | Feeling Irritated, Anxious or Nervous Because of the Mobility in the Clinic | Feeling Anxious due to Ambient Noise from People and Machines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume on audio/video player | 0.039 | -0.066 | .171* | -0.117 | -0.137 |

| Peak volume of voice in noisy environment | -0.077 | -0.158 | 0.066 | -0.107 | -0.164 |

| Perception of external sounds while using the music player | .194* | -0.005 | -0.155 | 0.035 | 0.079 |

| Total time spent using music players per day | .185* | 0.119 | -0.011 | 0.049 | 0.069 |

| Hours of continuous use of music player per day | 0.106 | .198* | -0.06 | 0.16 | .192* |

| Attend live concerts | 0.061 | 0.033 | 0.059 | -0.045 | -0.054 |

| Relaxing instrumental music | -0.061 | 0.092 | 0.096 | 0.134 | 0.149 |

| Foreign pop music | 0.073 | -0.1 | -0.009 | -0.086 | -0.155 |

| Foreign rock music | 0.119 | 0.061 | 0.063 | -0.031 | 0.04 |

| Greek pop songs | 0.052 | -0.16 | -0.067 | -0.138 | -0.087 |

| Greek folk songs | -.176* | -0.008 | -0.083 | 0.032 | -0.01 |

| Traditional songs | 0.002 | -0.032 | -0.067 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Classical music | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.15 | 0.102 | 0.095 |

| Opera | 0.002 | -0.128 | -0.144 | -0.103 | -0.1 |

| Movies on TV | 0.073 | .181* | 0.161 | 0.121 | 0.117 |

| News on TV | -0.158 | -0.032 | .186* | -0.107 | -0.14 |

| Random music from the radio | 0.048 | 0.067 | -0.124 | 0.118 | 0.115 |

| Specific playlist of the music I like | .190* | 0.048 | 0.158 | 0.025 | 0.11 |

| Specific playlist with doctor's choice | 0.044 | 0.08 | -0.023 | 0.154 | 0.16 |

| I prefer it to be quiet | -0.159 | -0.019 | 0.049 | 0.018 | 0.049 |

| Health Status1 | Noise Disturbance from Machines2 | Noise Disturbance from Patients or Staff3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | p | B | SE | Β | p | B | SE | β | p | |

| (Constant) | 3.57 | 0.74 | <.001 | 1.99 | 0.67 | 0.004 | -0.41 | 1.31 | 0.758 | |||

| Female vs Male | -0.33 | 0.17 | -0.18 | 0.055 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.120 | -0.50 | 0.30 | -0.15 | 0.102 |

| Private vs University clinic | -0.54 | 0.19 | -0.30 | 0.005 | -0.07 | 0.17 | -0.03 | 0.684 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.018 |

| Age | -0.19 | 0.09 | -0.30 | 0.034 | -0.20 | 0.08 | -0.27 | 0.015 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.227 |

| Education | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.372 | -0.23 | 0.11 | -0.21 | 0.035 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.636 |

| Noise sensitivity | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.226 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.027 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.789 |

| Perception of external sounds while using the music player | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.039 | -0.02 | 0.06 | -0.03 | 0.696 | -0.22 | 0.12 | -0.17 | 0.055 |

| Total time spent using music players per day | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.734 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.128 | -0.15 | 0.11 | -0.13 | 0.187 |

| Relaxing instrumental music | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.603 | -0.11 | 0.19 | -0.05 | 0.580 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.880 |

| Foreign pop music | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.412 | -0.03 | 0.22 | -0.02 | 0.878 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.964 |

| Foreign rock music | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.997 | -0.05 | 0.25 | -0.02 | 0.842 | -0.12 | 0.50 | -0.03 | 0.813 |

| Greek pop songs | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.064 | -0.18 | 0.32 | -0.05 | 0.572 | -0.45 | 0.62 | -0.07 | 0.464 |

| Greek folk songs | -0.86 | 0.39 | -0.20 | 0.030 | -0.24 | 0.36 | -0.05 | 0.496 | -0.91 | 0.70 | -0.12 | 0.193 |

| Traditional songs | -0.95 | 0.91 | -0.09 | 0.301 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.992 | 0.50 | 1.62 | 0.03 | 0.759 |

| Classical music | -0.08 | 0.25 | -0.03 | 0.762 | -0.12 | 0.23 | -0.04 | 0.600 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 0.535 |

| Opera | 0.54 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.546 | -0.74 | 0.80 | -0.06 | 0.359 | -1.25 | 1.57 | -0.07 | 0.429 |

| Movies on TV | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.142 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.454 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.061 |

| News on TV | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.178 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.295 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.151 |

| Random music from the radio | -0.03 | 0.26 | -0.02 | 0.903 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.831 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.095 |

| Specific playlist of the music I like | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.326 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.694 | 1.08 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.012 |

| Specific playlist with doctor's choice | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.277 | -0.10 | 0.23 | -0.03 | 0.666 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.258 |

| I prefer him to be quiet | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.775 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.678 | 1.34 | 0.55 | 0.28 | 0.016 |

| Headphones | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.818 | -0.22 | 0.17 | -0.11 | 0.206 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.139 |

| TV | -0.11 | 0.19 | -0.05 | 0.580 | -0.12 | 0.18 | -0.05 | 0.502 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.327 |

| Radio | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.229 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.188 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.998 |

| Smartphones | -0.69 | 0.20 | -0.37 | <.001 | -0.17 | 0.18 | -0.08 | 0.333 | 0.77 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.029 |

| Feeling irritated, anxious or nervous because of the mobility in the clinic | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.741 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.251 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.724 |

| Feeling anxious due to ambient noise from people and machines | -0.07 | 0.10 | -0.09 | 0.449 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.51 | <.001 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.156 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).