1. Background

Social media has become a vital tool in ensuring productivity among Undergraduates, as studies have shown an increased number of users globally [

1,

2]. It can be a website or an application that students utilize to interact with peers [

3], share ideas [

4], and become popular [

5]. It serves different purposes that aided online studies during the Covid-19 pandemic [

6], as social events were restricted. Most students have social media accounts like Facebook having, 2.9 billion monthly active users [

7]. Students have considered it helpful as it can help to maintain long-distance friendships and family relationships [

8].

Meanwhile, students obtain essential benefits such as scholarships [

9] and educative events [

10,

11] from some social media platforms. Considering benefits derived from Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Google+, Pinterest, forums, etc., however, would be time-consuming. Most students tend to stay online for long hours [

12,

13] as some dedicate short hours to studies which could negatively affect their preparation for quizzes, exams, and academic performance [

14].

Studies have observed that social media could influence memory processes [

15,

16]. Working memory has remained the essential tool required for academic activities among students [

17]. Students utilize its availability to resolve issues and understand their study directives [

18,

19]. The process of how social media could influence working memory has not been well understood. Studies have shown that social media could have a positive effect [

4,

20,

21] that can help achieve educative and scientific [

14] activities to improve academic performance. Only a few students utilize social media to exploit educational purposes [

22]. In as much as there could be helpful events that can boost the knowledge and skills of a student, there has not been a significant association between social media usage and student GPA [

5,

23,

24]. Furthermore, most of these studies were not related to students working memory. Though good academic performance does not necessarily signify good memory, academic failure can be observed among students with memory issues [

25].

The study objective was to examine the influence of social media on undergraduates working memory and academic performance. The students were from three Universities: two from Tbilisi (the capital city) and one from Batumi. We assessed the association between the harmful use of social media on gender differences, physical activities, academic performance, and working memory. There are limited studies on this directive, and this study has helped in finding the relationship regarding such measures. This study would help the students to have a broad understanding of the wide-growing influence of social media in their careers.

Methodology

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study was designed to examine the effect of social media on the working memory of undergraduate students from three different Universities in Georgia.

2.2. Data Collection

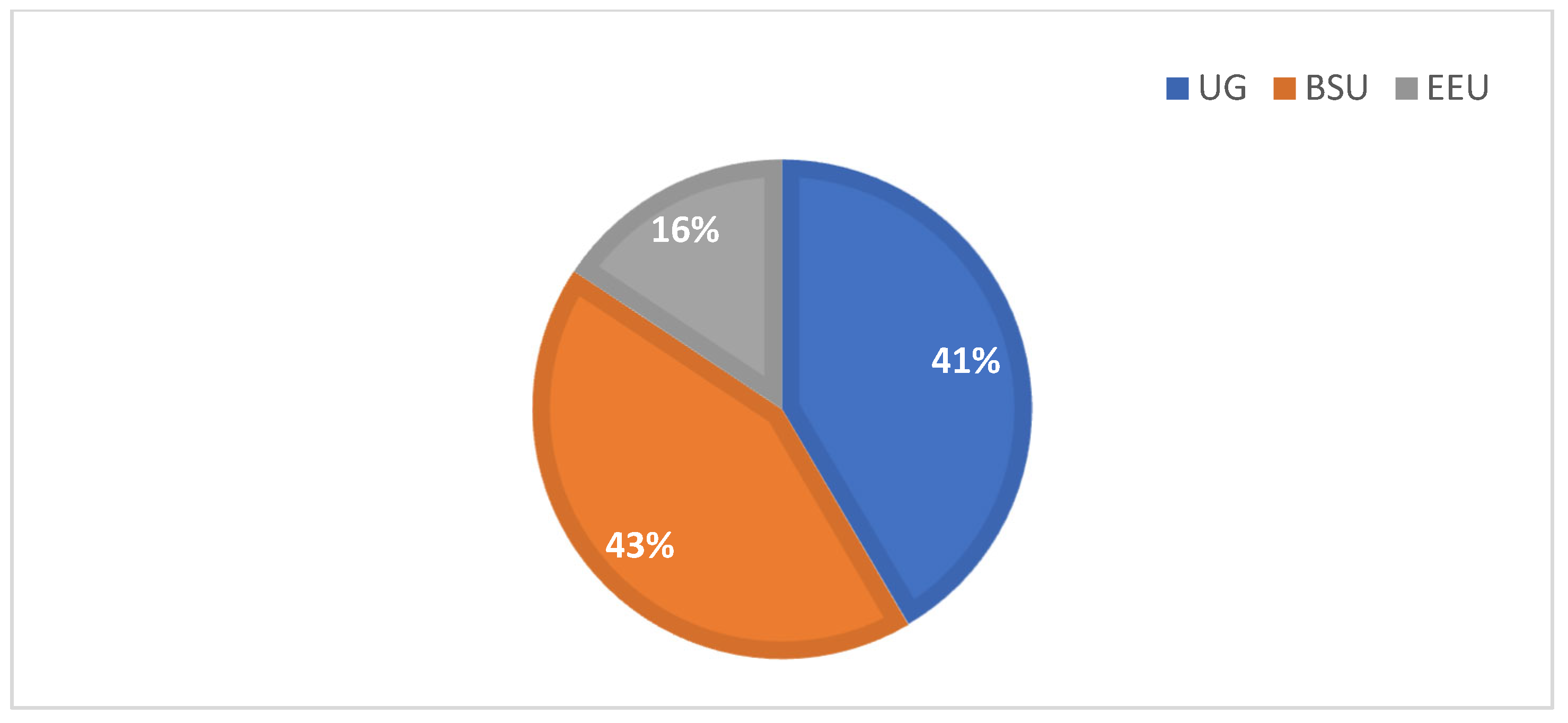

722 participants from three different universities completed this study. The collection survey form was distributed among Undergraduate students from the University of Georgia (UG), Eastern European University (EEU), and Batumi State University (BSU) through google forms. UG and EEU are in the capital city, and BSU is in Batumi City. Students from these universities were represented as they engaged each participant from 14th June to 2nd July 2023.

2.3. Participants

The study involved males and females above 18 years, Georgian and International students living and studying in Georgia. There was no reward to the participants as the responses were anonymous.

2.4. Informed Consent

Instructions and information on data privacy were available in the consent form and questionnaire to allow each participant to read through them before completing the study. The ethics approval for this study was provided by the Bioethics council of the University of Georgia.

2.5. Evaluation Tools and Techniques

The questionnaire consisted of sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, and institution) and three sections; social media disorder scale (SMD), academic performance scale (APS), and working memory (WM).

SMD scale was developed based on nine DSM-5 criteria for internet gaming disorder which had a binary variable of yes/no responses with nine questions regarding the social media experience (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, Snap Chat, Pinterest, TikTok, Google+, weblogs, and forums) over the past year [

26]. Questions on preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal, persistence, displacement, problems, deception, escape, and conflict were included in the measure which are elements of behavioral addictions [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Based on DSM-5, an individual with five or more of the nine criteria for 12 months qualifies for internet addiction. [

26,

27].

APS comprises 8- questions with a 5-point Likert scale covering questions relating to students’ academic performance. Students were scored based as follows; strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). The criteria for rating the performance were excellent (33-40), good (25-32), moderate (17-24), poor (9-16), and failing (0-8).

WM has 30 questions divided into storage domain questions, attention domain, and executive domain [

32]. Each subcategory involved 10- questions presented randomly as storage domain questions representing the short-term storage ability of the participants, text comprehension, and mental articulation. The attention domain included questions on distractions and multitasking. The executive domain involved questions on the ability to make plans and decisions. Each question was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 4 (severe problems in daily life) to 0 (no problem). The maximal score for each domain was 40, and the total score was out of 120, as higher scores indicate more complaints [

33].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 25.0 for Windows) software. Descriptive analyses were assessed for all study populations, characteristics, frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. We analyzed the comparison between gender difference, nationality, and Universities, and statistically significant at p<0.05. Before assessing the association between variables and multivariate analysis, APS and WM scores were grouped into dichotomous responses (Good/Needs improvement). The students that had cutoff < 24 were in ALS performance and > 25 WM subcategories, ‘’needs improvement’’. The odds ratio (OR) and prevalence evaluation at 95% confidence intervals (95% Cl) were presented.

3.0. Results3.1. Students’ Demographic Distribution

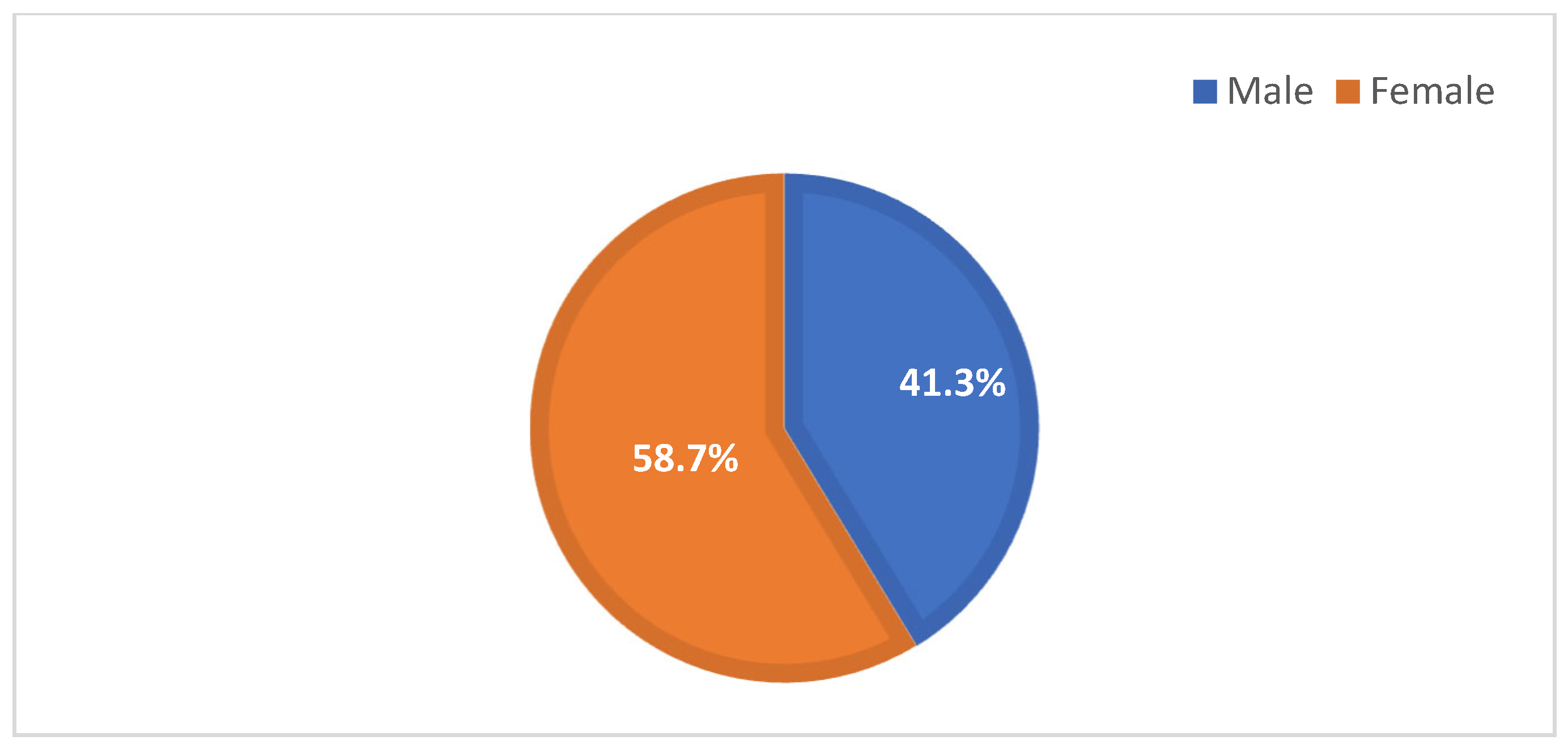

58.7% were female students (

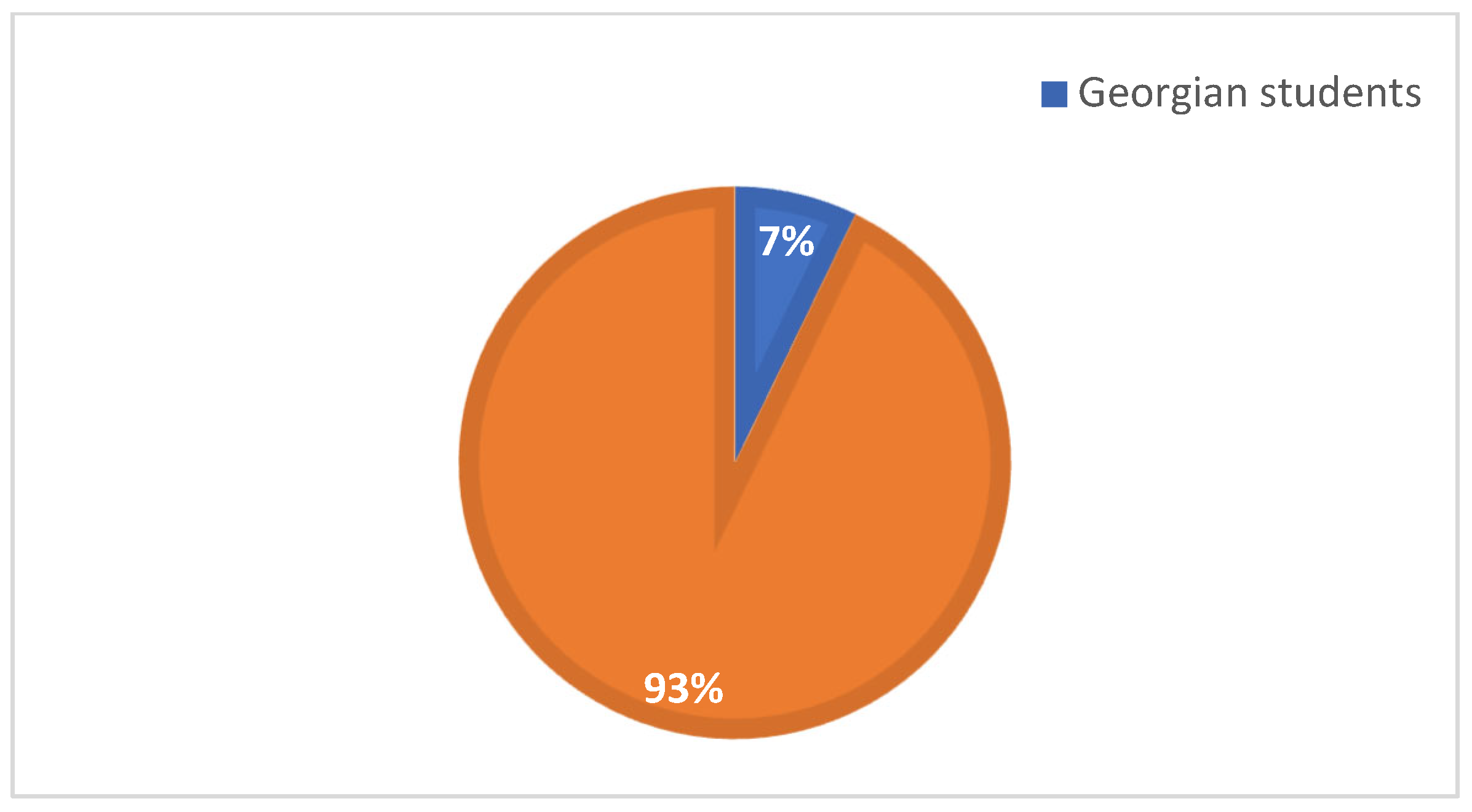

Figure 1), the mean age was 21.94 (SD ± 2.8), and most of the participants were international students (

Figure 2) from all three universities (BSU, UG, and EEU,

Figure 3). In

Table 1, the distribution of social media usage disorder among the students was observed higher in certain categories such as preoccupation (41.6%), persistence (60.9%), displacement (44.3%), and escape (67.6%). In the Supplementary Table S1, 16.2% of students needed an improvement in their academic performance. The students that had higher scores (>25) in the storage domain (4.4%), attention domain (6.2%), and executive domain (4.4%) had complaints (Table S1).

From

Table 2, the student’s demographic analysis based on cities (Tbilisi and Batumi) showed that more students from Tbilisi had persistence (59.8%), escape (69%) complaints, and students from Batumi had more preoccupation (43%), persistence (62.5%) and escape (65.7%). Table S2, showed that 14.5% and 18.4% of students in Tbilisi and Batumi needed an improvement in their academic performance. Few students from WM subcategories had complaints. From Table S2, 4.1% and 4.9% of students from Tbilisi and Batumi respectively, had short term storage domain, as 6.1% ( Batumi) and 6.3% (Tbilisi) required more action in the short-term.

In

Table 3, students from UG had more complaints about persistence (58.7%), displacement (48.7%), and escape (67.9%), students from EEU had more complaints about preoccupation (44.2%), persistence (62.8%) and escape (73.5%), and students from BSU had more complaints on preoccupation (43%), persistence (62.5%), displacement (41.4), and escape (65.7). In Table S3, 16% (UG students), 18.4% (BSU students) and 10.6% (EEU students) complained of moderate to poor academic performance. As 7.3% (UG students), and 6.1 (BSU students) had more complaints with attention domain, 3.5% (EEU) had the same complaints in all WM subcategories.

3.2. Association between Social Media Usage Disorder, Gender Differences, and Physical Activities

From

Table 4, 35.9% of male students and 64.1% of female students are at increased risk of using social media as an escape from negative feelings (OR 0.50; χ2 (18.206), p= 0.000, 95% Cl[0.368-0.692]). 51.6% of male students and 48.4% of female students had the risk of conflict with families and friends because of social media (OR 1.65; χ2 (6.507), p= 0.011, 95% Cl[1.122-2.452]

Table 4).

As illustrated in

Table 5, 89.7% that perform physical activities, considering their academic workload had the risk of preoccupation complaints (OR 1.91); χ2 (5.379), p= 0.020, 95% Cl[1.097-3.329]). 87.9% felt dissatisfied regularly because they wanted to spend more time on social media (OR 2.23; χ2 (8.361), p= 0.004, 95% Cl[1.281-3.908]

Table 5). As 87.8% of students intended to neglect other activities because of social media (OR 3.34; χ2 (17.054), p= 0.000, 95% Cl[1.834-6.112]

Table 5).

3.3. Association between Social Media Usage Disorder, Academic Performance, and Working Memory

In

Table 6, 80.3% of students that had good academic performance are at risk of neglecting activities such as hobbies, sports, and class assignments because of social media (OR 0.63; χ2 (5.133), p= 0.023, 95% Cl[0.425-0.942]). Most of the students with good academic performance had the risk of having arguments with friends because of social media usage (90%, OR 1.13; χ2 (5.368), p= 0.021, 95% Cl[1.099-3.470]

Table 6).

Table 7 presented that 94% of students with good working memory had the risk of withdrawal complaints (OR 0.34; χ2 (6.865a), p= 0.009, 95% Cl[0.154-0.793]). As 93.4% of having conflicts with parents, siblings, and partners as a result of social media.

3.4. Multivariate Analyses Predicting Academic Performance among the Students

The multicollinearity in social media addiction was evaluated following that all independent variables did not strongly correlate with the dependent. In the final model, out of the fourteen variables represented, physical activities, displacement, and problems were significant correlates of academic performance (

Table 8). The strongest correlate was physical activities which had an adjusted odd ratio (aOR) of 2.18 times. Students that complained of neglecting other activities for the purpose of social media are likely to have poor academic performance (aOR1.59) which is the same with students that had arguments with others because of social media usage (aOR 0.47).

4. Discussion

Our studies presented the prevalence of social media addiction and its effect on academic performance and working memory among undergraduate students. Utilization of social media differed based on the characteristics of the participants such as age, gender, and geography [

34]. Meng et al, [

35] reported an increasing trend in global social media addiction that can be observed among the participants in this study, as most of the students were international students. The influence of social media on individuals and society has been significant; it has affected both genders, shaping their perspectives, behaviors, and interactions within society [

36]. Social media has provided a platform to express emotions, encourage positivity, expose unrealistic beauty standards, and foster feelings of inadequacy, and dominant behavior [

3,

5,

37]. These could result in feelings of comparison, low self-esteem, jealousy, and anxiety [

38], suggested to have an influence on social media addiction in this study.

4.1. Gender Difference

We observed that ‘escape’ behavior was prevalent among female students. Considering certain societal expectations and pressures, that may lead to higher levels of stress and anxiety. Escape behaviors on social media can take many different forms, such as mindlessly browsing through feeds, playing video games online, watching YouTube videos, or attempting to attract attention and validation through likes and comments. Social media could be a coping mechanism, female students utilize to find solace [

39]. Moreover, male students had more ‘conflict’ with families and loved ones towards social media as female students may express emotions to avoid conflict and maintain relationships [

40]. Conversely, masculinity norms may discourage male students from engaging in activities perceived as distractions, leading to a low prevalence of escape behaviors among male participants [

39,

41,

42]. Additionally, social media companies' algorithms that are designed to keep both genders engaged and encourage addiction could increase the level of conflicts by making people less receptive to reasoned debate and more entrenched in their positions. Conflicts might become worse by misinterpretations and aggressive exchanges brought on by the lack of face-to-face engagement on social media [

43].

4.2. Physical Activities

Shimoga, et al [

44] reported that students who spend less time on social media could be productive in performing physical activities as observed in this study. The students that did not perform physical activity had complaints of ‘preoccupation’, ‘tolerance’, and ‘displacement’. As students tend to spend more time posting their daily activities [

45], it was reported in another study [

46] that ‘preoccupation’ strengthened the time spent. Negative online interactions might cause people to become distracted, struggle with time management, and put off tasks. The addictive nature of social media platforms, peer pressure, escapism, quick gratification, and the fear of missing out are all likely causes of students' obsession with abusing social media [

47]. Due to the lack of proper offline assistance, students may use social media as their main platform for social engagement. Stress, pressure, low self-esteem, a lack of coping mechanisms, peer pressure, anonymity, escapism, and attention-seeking are all likely causes of students' displacement behavior and social media abuse [

48].

4.3. Academic Performance

Our study did not predict GPA regarding academic performance although students with good performance had ‘displacement’ and ‘problems’. It has been reported that social media could have a negative effect on academic performance because of less time spent on learning and class activities which can be observed among students that need to improve their academic performance [

49]. It could be that the high prevalence of students who had complaints of neglecting other activities to entertain social media used it for educational activities [

9]. Though the increased duration of social media use per day could cause a deterioration in students’ academic performance [

50]. The modification of social networking sites has become more and more popular among students and is a major concern with its effects on studies [

51].

4.4. Working Memory

Our results showed that social media addiction regarding its effect on working memory did not widely affect the students’ working memory. The withdrawal and conflict complaints were observed among the students’ working memory. This result shows that no direct impact of social media addiction on working memory, but there could be an effect on academic performance because of negligence in important activities. A similar study that investigated the correlation between working memory and social media also found that working memory is less likely to be affected by social media use in healthy patients [

35]. In the same study [

35], it showed signs that excessive exposure to social media usage in patients with mental disorders like depression can influence working memory which is beyond the scope of this study. It was observed in another study that memory was negatively affected by social media usage which correlated to the stressors exposed to the brain [

52]. Though our study had a high prevalence of students with a good memory that struggled with complaints such as ‘withdrawal’ and ‘conflict’. We observed that some students have to work on improving their working memory.

4.5. Recommendation

To address the issue of social networking addiction, it is necessary to encourage digital empathy, inform people about the repercussions, and cultivate a safe online space with honest dialogue and encouragement for reporting abusive behavior [

53]. Students may get restless, irritable, anxious, and crave being online again when trying to cut back on consumption. Students find it difficult to stop using social media because of this addictive cycle, which emphasizes the importance of encouraging sensible usage patterns and digital well-being [

54]. There are possible effects on one's academic or professional career, concerns associated with online safety, and effects from social networking platforms. To reduce these hazards, it is important to encourage responsible behavior online, inform people of the repercussions, and put in place efficient reporting and moderation systems. It is imperative to encourage digital balance among students, teach them about responsible usage, encourage offline interactions, and increase their resilience so they can deal with challenges in real life. Students should establish boundaries, use digital moderation, and seek treatment for emotional difficulties. This will help people refocus their attention on worthwhile activities especially their studies [

55].

Furthermore, it offers a virtual environment where people can divert their attention from pressing issues or momentarily disconnect from pressures. Social media is an accessible alternative for stress release or relaxation because it can be easily accessed on smartphones and other devices. Social media can be very beneficial if used carefully but can also be detrimental when mishandled.

Conclusion

Our study has identified significant predictors for academic performance which are physical activities, and complaints such as displacement, and problems. Students are expected to consider the attention directed towards social media which could have a huge impact on their study. As there could be a request for counsel from any student experiencing these complaints. This would help to build healthy memory among the students and prevent psychosocial effects which are not covered in this study.

Strength and Limitations

This study covered the significant population of students from three different universities in the two most populated cities. It involved mainly international students in these institutions in different years of study. The study extensively considered each of the nine DSM-5 criteria for behavioral addiction in comparison with factors that could be a major concern among the students. These nine DSM-5 criteria were a subjective scale in which we could not specifically note the response towards a particular social network such as Facebook or Instagram or YouTube. But we assumed that the students’ response covers all social networks which remains a limitation in our study. As two or more of the criteria showed significant differences, further detailed studies are recommended. We were not able to diagnose students who had addiction considering the large number of students involved in this study, but the responses of students should attract more attention to creating awareness regarding social media addiction.

Author Contributions

M. E. N: Original draft, conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. M. E. M. and C.P: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. C. R and V. N: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing. Z. N: Original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics council of the University of Georgia (UGREC-31-23).

Informed consent: Comprehensive instruction was provided in the survey including a consent form in which the participant can discontinue the study at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support our findings are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants for the time dedicated to completing this study.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest. .

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Doğan, U. Doğan, U., & Adıgüzel, A. (2017). Effect of selfie, social network sites usage, number of photos shared on social network sites on happiness among University Students: A Model Testing. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(27), 2222-1735.

- Statista. Topic: Social media. Published 2022. https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks/. Accessed May 11, 2023. /.

- Hurt, N. E., Moss, G., Bradley, C., Larson, L., Lovelace, M., Prevost, L., Riley, N., Domizi, D., & Camus, M. (2012). The ‘facebook’ effect: College students’ perceptions of online discussions in the age of Social Networking. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A. (2018). Social skills. Social Skills, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Galadanci, B. S., & Abdulwahab, L. (2017). Adoption and use of a university registration portal by Undergraduate Students of Bayero University, kano. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences, 9(2), 179. [CrossRef]

- Paschke, K., Austermann, M. I., Simon-Kutscher, K., & Thomasius, R. (2021). Adolescent gaming and social media usage before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sucht.

- Dixon, S. (2023, February 14). Biggest social media platforms 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/. Accessed May 11, 2023.

- Madge, C., Meek, J., Wellens, J., & Hooley, T. (2009). Facebook, social integration and informal learning at university:‘It is more for socialising and talking to friends about work than for actually doing work’. Learning, media and technology, 34(2), 141-155.

- Cheston, C. C., Flickinger, T. E., & Chisolm, M. S. (2013). Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(6), 893–901. [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W., & Hennessy, C. (2017). Social Media use within medical education: A systematic review to develop a pilot questionnaire on how social media can be best used at BSMS. MedEdPublish. 2017: 1–36.

- Guckian, J., Utukuri, M., Asif, A., Burton, O., Adeyoju, J., Oumeziane, A., Chu, T., & Rees, E. L. (2021). Social Media in undergraduate medical education: A systematic review. Medical Education, 55(11), 1227–1241. [CrossRef]

- Vandelanotte, C., Sugiyama, T., Gardiner, P., & Owen, N. (2009). Associations of leisure-time internet and computer use with overweight and obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviors: cross-sectional study. Journal of medical Internet research, 11(3), e28. [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, S.(2013). The Usage of Social Networking sites Among the College Students in India. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 2 (5), 15-21.

- Hassan Abbas, A., Sawadi Hammoud, S., & Khazal Abed, S. (2015). The effects of social media on the undergraduate medical students. Kerbala Journal of Medicine, 8(1), 2161-2166.

- Firth, J. A., Torous, J., & Firth, J. (2020). Exploring the Impact of Internet Use on Memory and Attention Processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9481. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gleeson, J., Vancampfort, D., Armitage, C. J., & Sarris, J. (2019). The "online brain": how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(2), 119–129. [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual review of psychology, 63, 1-29.

- Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educational psychology review, 26, 197-223.

- Siquara, G. M., dos Santos Lima, C., & Abreu, N. (2018). Working memory and intelligence quotient: Which best predicts on school achievement?. Psico, 49(4), 365-374.

- Al-Rahmi, W. M., & Othman, M. S. (2013). The impact of social media use on academic performance among university students: A pilot study.(pp. 1-10). Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Asiedu, N. K. (2017). Influence of social networking sites on students’ academic and social lives: The Ghanaian Perspective. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 1535.

- AlFaris, E., Irfan, F., Ponnamperuma, G., Jamal, A., Van der Vleuten, C., Al Maflehi, N., Al-Qeas, S., Alenezi, A., Alrowaished, M., Alsalman, R. and Ahmed, A.M., 2018. The pattern of social media use and its association with academic performance among medical students. Medical teacher, 40(sup1), pp.S77-S82.

- Alwagait, E., Shahzad, B., & Alim, S. (2015). Impact of social media usage on students academic performance in Saudi Arabia. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 1092-1097.

- Alahmar, A.T., 2016. The impact of social media on the academic performance of second year medical students at College of Medicine, University of Babylon, Iraq. Journal of Medical & Allied Sciences, 6(2), p.77.

- Roberts, G., Quach, J., Gold, L., Anderson, P., Rickards, F., Mensah, F., Ainley, J., Gathercole, S. and Wake, M., 2011. Can improving working memory prevent academic difficulties? A school based randomised controlled trial. BMC pediatrics, 11, pp.1-9.

- Van den Erjnden, RJ.J.M., Lemmons, J.S., & Valkensburg P.M. (2016). The Social Media Disorder Scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478-487.

- Brown, R. I. F. (1993). Some contributions of the study of gambling to the study of other addictions. Gambling behavior and problem gambling, 1, 241-272.

- Some contributions of the study of gambling to the study of other addictions. Gambling behavior and problem gambling, 1, 241-272.

- Demetrovics, Z., Urbán, R., Nagygyörgy, K., Farkas, J., Griffiths, M. D., Pápay, O., Kökönyei, G., Felvinczi, K., & Oláh, A. (2012). The development of the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire (POGQ). PLoS ONE, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, F., Psych, G., Kleimann, M., Mediasci, G., & Mößle, T. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of video game dependency in adolescence: results of a German nationwide survey. Cyberpsychology, behavior, and social networking, 13(3), 269-277.

- Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media psychology, 12(1), 77-95.

- McGregory, C. (2015, April 13). [PDF] Academic Performance Questionnaire. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/57347883/_PDF_Academic_Performance_Questionnaire.

- Vallat-Azouvi, C., Pradat-Diehl, P., & Azouvi, P. (2012). The Working Memory Questionnaire: A scale to assess everyday life problems related to deficits of working memory in brain injured patients. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 22(4), 634–649. [CrossRef]

- Almarzouki, A. F., Alghamdi, R. A., Nassar, R., Aljohani, R. R., Nasser, A., Bawadood, M., & Almalki, R. H. (2022). Social Media Usage, Working Memory, and Depression: An Experimental Investigation among University Students. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 12(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.-Q., Cheng, J.-L., Li, Y.-Y., Yang, X.-Q., Zheng, J.-W., Chang, X.-W., Shi, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, L., Sun, Y., Bao, Y.-P., & Shi, J. (2022). Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, 102128. [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body image, 12, 82–88. [CrossRef]

- Primack, B. A., Karim, S. A., Shensa, A., Bowman, N., Knight, J., & Sidani, J. E. (2019). Positive and Negative Experiences on Social Media and Perceived Social Isolation. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 33(6), 859–868. [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J. , Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: the impact of Facebook on young women's body image concerns and mood. Body image, 13, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- M.Pilar Matud. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles, personality and individual differences.Volume 37, Issue 7, Pages 1401-1415. [CrossRef]

- Monique Timmers, Agenta Fischer & Antony Manstead. (2010). Ability versus vulnerability: Beliefs about men's and women's emotional behaviour. Cognition and Emotion, Vol.17: 41-63 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Anke Samulowitz, Ida Gremyr, Erik Eriksson, Gunnel Hensing, "“Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”: A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain", Pain Research and Management, vol. 2018, Article ID 6358624, 14 pages, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeyer, C. Nonwork-to-work spillover: A more balanced view of the experiences and coping of professional women and men. Sex Roles 28, 531–552 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Zeitzoff, T. (2017). How Social Media Is Changing Conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(9), 1970–1991. [CrossRef]

- Shimoga, S. V., Erlyana, E., & Rebello, V. (2019). Associations of social media use with physical activity and sleep adequacy among adolescents: Cross-sectional survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(6). [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaus, J. M., Patten, E. V., Roche, C., & Young, J. A. (2015). #gettinghealthy: The perceived influence of social media on Young Adult Health Behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 151–157. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, T., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Campbell, S. M. (2020). Unique Associations of social media use and online appearance preoccupation with depression, anxiety, and appearance rejection sensitivity. Body Image, 33, 66–76. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, T., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Campbell, S. M. (2020). Unique associations of social media use and online appearance preoccupation with depression, anxiety, and appearance rejection sensitivity. Body Image, 33, 66–76. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C. I., Chen, Y. H., & Chu, J. Y. (2022). New social media and the displacement effect: University student and staff inter-generational differences in Taiwan. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, P. P. C. M., & Ilankoon, I. M. P. S. (2022). The impact of social media on academic performance and interpersonal relations among health sciences undergraduates. Journal of education and health promotion, 11, 117. [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, A. M., Pandey, A. K., Nayak, R., Pujary, K., & Kumar, A. (2021). Impact of social media on the academic performance of undergraduate medical students. Medical journal, Armed Forces India, 77(Suppl 1), S37–S41. [CrossRef]

- Munang, M. G. (2022). Effect of Social Media on Students’ Academic Performance in Ahmadu Bello University Zaria. [CrossRef]

- Neika Sharifian & Laura B. Zahodne (2020): Daily associations between social media use and memory failures: the mediating role of negative affect, The Journal of General Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Skues, J., Williams, B., Oldmeadow, J., & Wise, L. (2016). The Effects of Boredom, Loneliness, and Distress Tolerance on Problem Internet Use Among University Students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(2), 167–180. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. C., Chen, M. Y., Wu, Y. F., & Wu, Y. T. (2022). The Relationship of Social Media Addiction With Internet Use and Perceived Health: The Moderating Effects of Regular Exercise Intervention. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2021). Perceived challenges and online harms from social media use on a severity continuum: A qualitative psychological stakeholder perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 1–26. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).